During the last days of January until the beginning of February, the university campus was flooded with zombies.

They weren’t the brain-munching monsters seen in movies and television dramas; they were harmless, really. But their staggering gaits, sallow complexions, and hollow eyes were as ominous as those of the living dead.

The sole cause of the zombie outbreak was…fall semester final exams.

As one might expect, the degree of zombification was most extreme in the first-year students. After all, they took the most classes. If they wanted to be able to take it easy at all in their remaining school years, students had to earn as many general education credits as possible in their first year. Notes from missed lectures were sold at steep prices. Past exam questions—inherited from club upperclassmen—were passed around frantically. People who had barely shown their faces on campus so far turned up for the first time in ages. As the cold midwinter winds raged, a different kind of mania than the school festival swept over the college grounds.

In retrospect, the spring semester final exams had caused comparatively less panic. Although those had been their first exams since entering the university, many first-years had yet to grow out of the grade school habit of taking their studies seriously, and aside from students who took half-semester courses, they hadn’t come face-to-face with the possibility of failing a college class.

Fall semester final exams were another story. Many students withdrew gradually from their studies as they got accustomed to college life. After spending their days absorbed in part-time jobs and club activities, staying out late with friends and partners, or frequenting group dates, students had to take on the last exam period of the academic year.

Out of practice with all-night study sessions, many students were practically done in by the effort of it. Those who had made a habit of skipping classes were in even more trouble. They stumbled into classrooms on unsteady feet, as if getting out of bed on time to take the exam had been difficult enough.

But finally, on the last day of exams, the zombified students would return to life once more.

The exam period for Seiwa University’s current fall semester ended on February 1.

Circumstances varied based on which courses one was enrolled in, but in Naoya Fukamachi’s case, the very last exam of his first year in college—the Western History I final—came to a joyous close in third period on the first of February.

The contents of the exam had been announced to the class in advance; they were asked to choose one of three essay prompts to respond to. That kind of long-form written-style exam—where students were given a two- or three-line prompt and expected to fill the rest of the two pages it was printed on with a response they devised themselves—was common in college, unlike the format encountered up through high school. Some exams were open-book, but that was absolutely not the case for Western History I, so Naoya had needed to memorize his response ahead of time.

“Phew! It’s over…! I feel like I’ve wrung my brain completely dry and now it’s totally useless…!”

“Ugh, I still have one more exam after this!”

As the bell signaling the end of the period rang and test papers were passed to the front, several students began to talk. Like Naoya, many of them seemed to have just completed their last exam, and they were being carried off in the swelling wave of freedom.

Naoya, also feeling the relief, stretched a little. Having an almost perfect attendance record meant he had pretty much avoided zombification during exams, but he had still found it difficult to completely memorize his essay response for this final in particular. All he could do now was hope he hadn’t made any mistakes.

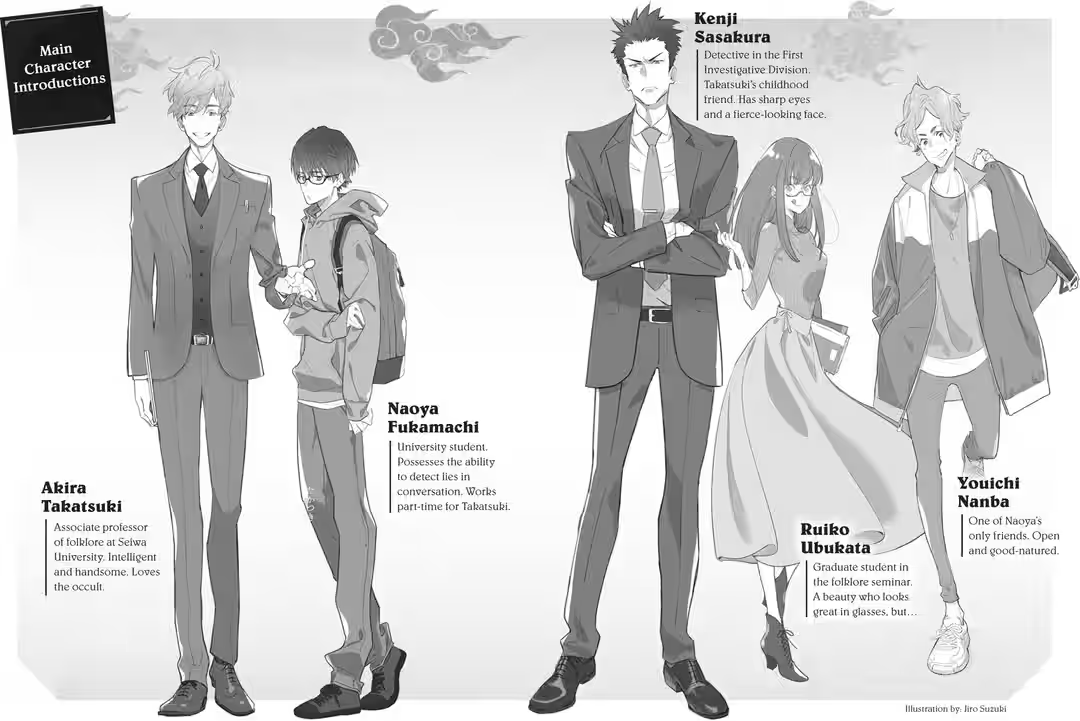

Looking around, Naoya realized one of the proctors at the front of the classroom was waving to him—a female graduate student with long hair and red glasses: his acquaintance Ruiko Ubukata.

Ruiko’s wave turned into a beckoning motion, so Naoya put on his coat and scarf and made his way over to her.

Gathering up the stacks of exam papers, Ruiko grinned broadly at him.

“Congrats on finishing, Fukamachi! How’d the test go?”

“It went okay, I think… More importantly, why are you here, Miss Ruiko? This is a Western history class.”

Curious, Naoya couldn’t help but ask. Ruiko was studying folklore and antiquities, not Western history.

But she waved off his question lightly.

“Oh, I’m just working part-time.”

“Huh?”

“Proctoring undergraduate exams is basically a side gig for grad students. The Academic Affairs Office assigns us to them willy-nilly, so sometimes we end up in charge of exams outside our departments. But I mean, all I have to do is pass out tests, collect them, and verify everyone’s identity.”

As Ruiko explained, Naoya recalled that he had also encountered another graduate student he knew—Yui Machimura—at a different exam.

“Identity verification” sounded like a bit of an exaggeration of proctor duties, but evidently in previous years, there had been a rash of incidents in which students in high-occupancy lectures got other people to take their exams for them. Consequently, present policy required examinees to put their student ID cards on their desks throughout the test. Proctors walked around to every seat, comparing every single ID photo to its owner.

“…But isn’t the photo on our student IDs the one we used for the university entrance exam? Aren’t there a lot of people who don’t really resemble their own IDs anymore?”

“Oh, tons. It’s really common for people to switch from wearing glasses to contacts. Girls start putting on makeup and look like totally different people. The boys, too. It’s pretty interesting seeing how many very serious-looking high school boys have rebranded themselves as blond playboy types… In your case, though, Fukamachi, what’s interesting is how you look exactly the same as before.”

“Well, excuse me for not changing, I guess.”

Naoya had always been a reserved kid with glasses. Even the navy-blue coat he was currently wearing was something he’d had since high school.

“Anyway, did you need something from me?”

“Oh, right. Are you busy tonight, Fukamachi?”

“Huh?”

“If you’re free, you might wanna consider dropping by Professor Akira’s office. I just wanted to tell you that.”

“…Drop by for what?”

“Hee-hee… That’s a secret.”

Ruiko smiled an elusive smile.

Wondering what was going on, Naoya left Ruiko with a simple “I’ll swing by if I can.” Retrieving his headphones from his bag and shoving them in his ears, he headed for the exit. All the other examinees were already gone, leaving no one but Naoya behind.

…Or so he thought, before he noticed a zombie draped listlessly over a chair in the very back of the classroom.

The zombie had familiar brown hair.

For a moment, Naoya considered simply continuing on his way, but the zombie was a little too listless for his peace of mind, so he went closer to check it out. It didn’t so much as twitch.

Taking out his headphones, Naoya tried calling out in a soft voice.

“…Nanba?”

With great effort, the zombie lifted its head.

As Naoya had thought, it was Youichi Nanba, a fellow first-year in the Literature Department. But Naoya was so caught off guard by the change in Nanba’s appearance that he almost backed away instinctively. His face, usually adorned with a friendly smile, verged on gaunt, and dark circles stood out beneath his eyes. He really did look like a zombie.

On top of that, for some reason, Nanba’s face was covered in injuries. Abrasions dotted his cheeks and the tip of his nose; small bumps protruded from his forehead. He was still wearing his black peacoat despite being indoors, and Naoya wasn’t sure if that was because the back row of seats was subject to cold drafts from the exit or because Nanba simply hadn’t had the energy to take it off.

“Oh,” Nanba said. “If it isn’t Fukamachi… You good…?”

“Uh, I’m fine, but…are you? What happened to you?”

“I’m a goner. Go on without me… I’m done for…”

Muttering in a hoarse voice, Nanba slumped back over the desk and stopped moving.

Naoya glanced toward the front of the classroom.

The exam proctors—including Ruiko—and the Western History I professor were looking their way questioningly. If they didn’t vacate the room soon, they would probably get in trouble.

“Nanba. I don’t know what you’re sulking about, but get up. It’ll be a pain if you die there.”

“I can’t. I don’t have the strength to stand anymore…”

“Who cares? Just hurry up.”

Naoya haphazardly tossed the writing implements still sitting out on the desk into Nanba’s bag. When he picked up the student ID that was also displayed, his gaze dropped incidentally to the photo.

“Oh? In high school, you wore a school uniform and had black hair?”

“—Hey, wha—?! Fukamachi! Give that back!”

All at once, the zombie sprang back to life, snatching the ID card from Naoya’s hand in a flash.

Naoya, meanwhile, merely grabbed Nanba’s bag and walked briskly out of the classroom.

“Nanba, do you have any exams left?”

“…That was my last one.”

“Then you can vent to me for a little bit. Let’s go to the cafeteria,” Naoya said, looking back over his shoulder at Nanba, who was following him but dragging his feet.

As if surprised by Naoya’s offer, Nanba’s eyes widened a little.

Then, the spitting image of a zombie once more, he tottered toward Naoya with both arms outstretched.

“Fu-Fukamachiii… You’re a surprisingly kind guy, y’know…”

“What do you mean surprisingly? How is that surprising?”

After using the other boy’s bag to ward off Nanba’s attempt at a hug and his overcome expression, Naoya handed it to him.

“You let me borrow some of the past exam questions. I’m just paying you back for that.”

Since he didn’t belong to any clubs, Naoya had no reliable way to get his hands on old test materials.

And even though he had given Nanba the notes from the classes he skipped, Naoya really did find the past exam questions useful.

Student life involved a lot of give-and-take. A certain amount of fellowship with other students was a good thing, even if Naoya tried to stay away from socializing. Just a little wouldn’t hurt.

The cafeteria was crowded. Like Naoya and Nanba, many of the students had probably just finished with exams. The only open seats were on the patio, so after buying just a coffee each, the two of them made their way outside in their coats and gloves to sit.

Exposed to the elements, the patio was mercilessly freezing in the colder months. Naoya wondered if they would have been better off going to the library.

“So what happened to your face? Did you get into a fight with a yakuza?”

Nanba shook his head wordlessly.

Naoya thought things over for a minute. Then—

“…Nanba. If you got into some stupid fight with your girlfriend last night because she caught you fooling around even though it’s finals season, you better start by going to apologize, because you’re in the wrong here.”

“No, it’s nothing like that.”

Nanba’s injury-riddled face screwed up into a frown.

He ran a hand roughly through his brown hair, then propped himself up against the table with his elbows, looking utterly defeated.

“Listen… I’m about to say something really stupid, but don’t laugh.”

“Got it. I’ll try my best.”

“Yeah, please. It’s just… I…”

Hesitating for a moment, Nanba ruffled his hair again before continuing.

“…I think, maybe…I might be cursed.”

“What?!”

Though he didn’t laugh, Naoya couldn’t help but look at Nanba in surprise.

Nothing in Nanba’s demeanor pointed to him joking around, and most importantly—Naoya could tell with certainty that he wasn’t lying.

“Cursed? What on earth happened?”

“Um, well… You know about chain letters, right?”

“You mean like a letter that starts with ‘You have been visited by an omen of misfortune’ or something like that?”

“Exactly. Then goes on to say, ‘Unless you forward this letter to five people within the next three days, you will have bad luck.’ I…got one of those.”

Two days prior, the letter had shown up in Nanba’s bag without his noticing it.

It was written on plain notepaper—in penmanship so neat it seemed like a ruler was used—and stuffed into a white envelope. A standard chain letter through and through, there was no return name or address.

Naturally, Nanba hadn’t taken it seriously.

He read it over once, snorting at its absurdity, and threw it in the trash.

“I mean, who believes in chain letters these days? Most people don’t, right?”

“It’s definitely more old-fashioned, as far as forms of harassment go.”

“But…lots of weird stuff has happened since I got it…”

Things had started the day before.

As Nanba was walking down the street, a flowerpot fell from overhead.

The pot had plummeted from the second floor of the house he was passing, shattering on the ground mere inches in front of him. Apparently, the woman who lived in the house had dropped the flowerpot accidentally while changing out the ones in her window garden. Dreadfully embarrassed, the woman had apologized to Nanba, who could have been seriously injured if the pot had struck him. Unsurprisingly, the incident left Nanba a bit shaken up.

Next, there was the staircase at the train station.

A sudden altercation broke out between two office workers in the middle of their ascent on the stairs. Nanba, directly behind them, got hit with a stray blow and was nearly sent tumbling down the steps. Thankfully, he was able to grab onto the handrail right away, or he might actually have fallen.

“Those both happened in the same day. I thought it was weird that I almost got badly hurt twice in one day, but I just chalked it up to some occasional bad luck. I didn’t think it was anything more than that at first.”

But Nanba’s misfortunes didn’t end there.

After returning home and trying to unlock his apartment door, he realized his key was missing. He was able to borrow a spare after talking it over with the landlord, but then his heating system failed without warning in the middle of the night, and Nanba had to wear a coat to sleep in his own bed.

At that point, it seemed, Nanba started to find the situation strange.

No matter how one looked at it, the number of unlucky incidents he experienced in succession was unusual.

That was when the chain letter popped back into his mind.

There’s no way, he thought. Even entertaining the idea was foolish.

But if Nanba was being honest, recalling the letter left him with a slight chill.

“I’m telling you—I’ve never had so many bad things happen to me in one day in my whole life… Anyone would get a little weirded out, right?”

Things continued to go wrong that very morning.

The alarm clock that should have been set to go off every single day inexplicably failed to chime. By the time Nanba woke up, his first-period exam was already starting. He got ready in a panic and rushed from his apartment—only to fall down the building stairs.

He came away with no more than scattered bumps and scrapes, quite fortunately, and headed straight for the station like that. But once he arrived, he found the train wasn’t running due to an accident.

“That much stuff happening all at once can’t be normal! Like, something has to be off, right?! I gave up on the train and ran to school because it’s only one stop away, but I missed my first-period exam completely, and all my exams after that were a total wash. I can’t help but feel like I really was cursed…”

Nanba groaned, slumping over the table with his head in his hands.

Naoya couldn’t deny that it was unusual to go through that many unfortunate incidents in such a short period of time… Though he had a feeling Nanba’s poor study habits were to blame for his subpar exam performance.

“Hey, Fukamachi, do you think I should go have a purification ritual done? Where do you even go for something like that? A shrine? A temple? Some kind of psychic, maybe?”

“Hmm… Well.”

When it came to matters such as this, there was only one person at Seiwa University to turn to…

Naoya picked up his coffee. It had long since gone past lukewarm and settled on cold, so Naoya threw the remainder back in one gulp and took out his phone. Waffling a little between calling and sending a message, he decided on the latter for the time being.

A reply—“Come right now”—came almost at once. Wondering if the man was bored or something, Naoya stood up.

“Nanba. Come with me.”

“Huh?”

“It’s freezing here. Let’s go to Professor Takatsuki’s office. He said he would hear you out.”

“Uh, wh-why him…?”

“You should probably get an expert’s opinion first, don’t you think? Come on, let’s go.”

Akira Takatsuki was a well-known associate professor at Seiwa University.

He specialized in folklore and taught Folklore Studies II, a general education course that both Naoya and Nanba had taken for the past year.

Despite the “folklore” label, the object of Takatsuki’s research was somewhat strange matters like urban legends and ghost stories. The topics they covered in Folklore Studies II—bathroom hauntings and human-faced dogs—were the kind of things one expected to see in a TV variety show, things that could perhaps be referred to as modern folklore. Chain letters fit right into that category, in Naoya’s opinion. If Nanba wanted advice, there was no one better to go to than Takatsuki.

“Professor Takatsuki’s class was interesting, but…he didn’t even give us a final, just had us submit a report. He really said he would meet with me? More importantly, Fukamachi, why do you have Professor Takatsuki’s contact info?”

“I work part-time for him.”

“What do you mean, work?”

“Remember how he accepts submissions of strange experiences and secondhand stories on his website? Now and then, someone sends him a request for help with something like ‘I think my apartment is haunted, and I don’t know what to do.’ I accompany him as an assistant when he goes to investigate cases like that.”

“Wow, that sounds kinda fun.”

“…It has its ups and downs.”

Naoya’s reply was vague. He could hardly talk about getting mixed up in a crime and almost burning to death.

“Is that all you do for work, Fukamachi?”

“No. It’s not like requests come in every week. It would be tough to get by on that kind of inconsistent job alone. I also grade homework part-time for a distance-learning cram school. Remind me what your job is, Nanba?”

“I work at an izakaya. I also started as a private tutor recently.”

“Huh, I can’t really picture you as a tutor. That kind of thing takes a lot of prep, right? Isn’t it hard?”

“Nah, I’m tutoring an elementary schooler. One of my relatives’ kids, actually. They live nearby, and the kid isn’t aiming for a private middle school or anything. I’m just teaching studying methods, really. They also feed me dinner while I’m there, so it’s not a bad gig.”

“Is the student a boy?”

“Girl. Fourth grade. She’s super cute, too. Always calling me Yo-Yo.”

“…Nanba. You know it’s illegal to get involved with an elementary school kid.”

“Wh-what are you—? As if I would! What kind of guy do you think I am?!”

As they talked, Naoya and Nanba made their way from the cafeteria to the faculty building. Evidently, Nanba had never been inside the building before, and he trailed anxiously after Naoya, goggling at their surroundings.

Takatsuki’s office was on the third floor, marked by a plaque with the number 304 on it. Under that, in smaller characters, it read: LITERATURE DEPARTMENT, HISTORICAL LITERATURE FACULTY, FOLKLORE AND ANTIQUITIES, AKIRA TAKATSUKI.

When Naoya knocked on the door, a voice from inside called out, “Come in.”

“Excuse us,” he replied, opening the office door and entering with Nanba on his heels.

“Welcome, Fukamachi! And may I assume you’re the one who received the chain letter? Thank you both for coming.”

Takatsuki, who had been typing away at his laptop at the large table in the center of the room, stood up with a beaming smile.

The professor was, simply put, a good-looking man. With his light-brown hair, kind and handsome face, and tall, well-proportioned body clothed in a three-piece suit, he was every bit the refined gentleman. His classes, consequently, were exceedingly popular with girls; female students completely filled the front row of seats in his lectures, which were usually left conspicuously empty in other classes.

Naoya shoved Nanba, who was still lingering near the doorway, toward Takatsuki.

“Sorry to bother you, Professor. This is Nanba.”

“Th-thank you for seeing me…”

Nanba nodded at the professor.

Takatsuki smiled brightly at him in return.

“Ah, you took Folklore Studies II as well. I remember your face. Can I get you something to drink, since you came all the way here? I have cocoa, coffee, black tea, and green tea.”

“Um, then, I’ll have coffee…”

“I really recommend the cocoa, by the way!”

“…U-uh, okay. Cocoa, please…”

Nanba gave in meekly to Takatsuki, who was showing him the Van Houten cocoa bag excitedly. He’s a nice guy, Naoya thought, watching the exchange.

Takatsuki’s office was nice and toasty. Taking off his scarf, gloves, and coat, Naoya sat down in a folding chair. Nanba followed suit but remained unsettled, glancing here and there around the room. He turned his gaze to the bookshelves lining three of the office walls, taking in the antique volumes bound in the Japanese style and thick textbooks lined up alongside the occult publications and magazines, occasionally muttering things like, “Whoa, he’s got issues of MÜ…”

Standing at a small table set under a window at the back of the room, Takatsuki prepared their drinks. The table was home to a kettle and a coffee maker. Beside it, a bevy of mugs in all colors and patterns were housed in a small cupboard.

“Here you go.”

Returning to the center table with a tray in hand, Takatsuki placed a cup of cocoa in front of Nanba.

“Thank you very— …Wow, this mug sure is something.”

Nanba’s honest impression of the multicolored Great Buddha pattern on his cup slipped out whether he intended it to or not.

“Visitors to this office always use that mug,” Naoya explained, taking his own mug from Takatsuki.

Before he had brought in his own personal-use cup, Naoya had also been made to drink his coffee from the Great Buddha mug.

“Now then, why don’t you tell me your story, Nanba? I want to know the details of how you received the chain letter and the bad luck that came after.”

Takatsuki took the seat next to Nanba, making it look like he and Naoya had trapped the other boy there.

Nanba raised his hand slightly.

“…Um, Professor, do you mind if I ask you something first?”

“Not at all. What is it?”

“It’s just… That seems like a lot for you to drink all by yourself.”

Puzzled, Takatsuki glanced down at his own blue mug.

It was filled to the brim with the same cocoa he had made for Nanba. But Takatsuki’s cup also had two massive marshmallows floating in it. Even Naoya was able to catch a whiff of the sweet aroma that rose up out of the drink along with the steam.

“—Oh! I’m sorry! I only put marshmallows in my own! Of course you want some, too, Nanba! It tastes better that way! Wait just a moment; I’ll grab them for you!”

“No, no, no, that’s not it! I don’t want any marshmallows! I just meant that you must have a massive sweet tooth, Professor! There aren’t even that many girls who drink stuff like that!”

“Glucose nourishes the brain, so it’s better to be proactive about your sugar intake, you know.”

“Something that sweet probably wouldn’t agree with my system, actually…”

“Oh? But it’s so delicious!”

Takatsuki took a sip of his cocoa, smiling blissfully.

Bringing his own drink to his lips, Naoya watched Takatsuki and Nanba’s back-and-forth with a somewhat nostalgic feeling in his chest. His mug—decorated with a drawing of a golden retriever—was full of black coffee. Takatsuki was well aware of Naoya’s dislike for sweets.

“—Anyway, let’s hear your story about the chain letter now.”

As the discussion about their beverages petered out, Takatsuki brought them back on topic.

Nanba’s expression instantly turned meek.

Then he told the professor the exact same thing he had shared with Naoya earlier.

Naoya listened silently, paying close attention to the sound of Nanba’s voice.

When the story was done, Takatsuki glanced casually at Naoya, who gave the smallest headshake. Takatsuki responded with a tiny nod before returning his gaze to Nanba.

“Nanba, I’d like for you to verify a few things about your story, if that’s all right?”

“…Okay.”

“When you found the chain letter, it was inside your bag, yes? In other words, it wasn’t mailed to you?”

“Right. There was no stamp or anything on it.”

“I see. And you said you already threw the actual letter out. Does that mean it’s no longer in your garbage can at home?”

“Yeah… I took out the recycling yesterday morning…”

“It no longer exists in this world, then. Your series of unfortunate events began after you had thrown out the letter, but—its contents said you had to forward the letter to five people within three days, isn’t that right? It hasn’t been three days since you found the letter. What are your thoughts on that?”

“Well… I don’t know when the letter was put in my bag in the first place. The day I found it might have been the third day since it was put there. Even if the deadline hasn’t passed yet, I’ve got a feeling the problem was me tearing it up and tossing it without even thinking.”

“You’re saying you think throwing away the letter was deemed sufficient proof of your lack of intention to follow its orders, and that caused the curse to take effect early.”

“…I don’t know how else to explain it.”

Nanba’s gaze dropped to his untouched cup of cocoa.

His expression had grown more and more somber as he spoke. Before, his tone had maintained its usual cheerfulness, but in the end, thinking about the things that kept happening to him must have been frightening.

In any case, there were no lies in Nanba’s story. He hadn’t even exaggerated anything.

All the incidents he described had actually taken place, and Nanba truly did believe his destroying the chain letter was to blame.

Then…

“—Nanba.”

Hearing his voice, Naoya thought, Ah, I figured this was coming.

Takatsuki held his right hand out toward Nanba.

For a moment, Nanba stared back at the professor in confusion. Then, ever so timidly, he extended his own right hand.

Takatsuki grasped it tightly in both of his own.

He tugged Nanba forward in one smooth motion, leaning in close with his model good looks, peering into Nanba’s face.

“Uh, wh-what? Wh-what’s happening? You’re too close!”

“Nanba, I’m so glad you came here today. I’m so happy I got to meet you.”

Nanba stared at Takatsuki, alarmed, as the professor murmured to him in rapt tones.

Then, all at once—Takatsuki threw his arms around the boy.

“Congratulations, Nanba! What a truly incredible experience you’re having! To receive a handwritten chain letter in the golden age of e-mail and text messaging! And what’s more, you broke the chain! And now you keep having bad luck! You are an absolutely perfect example of a chain letter story!”

“Wh-what the—?! What’re you—?! Wha—?! Wh-why is he this excited, Fukamachi?!”

On the receiving end of Takatsuki’s passionate embrace, Nanba yelled in panic. His physique was fairly similar to Naoya’s, so he fit pretty snugly in Takatsuki’s arms.

Naoya took a sip of his coffee before replying.

“This guy is obsessed with the supernatural. When a tale tickles his fancy, he gets fired up, and all common sense and social etiquette go flying out the window. Then he holds the other person’s hands or tries to hug them.”

“But why?!”

“Probably because he gets carried away by his excitement? I personally think it’s a lot like when a big, friendly dog jumps on someone. Sorry, by the way. I usually stop him before he goes in for the hug, but since you’re not a girl, I figured it was fine to let it happen this time.”

“It’s not! It’s not fine! Hurry up and get him off me! Help!”

Takatsuki’s unyielding arms seemed to be squeezing the shrieks out of Nanba.

You’re the one who tried to hug me just a little while ago, Naoya thought, taking his time to stand. He went around the large table, stopping behind Takatsuki to tap him lightly on the shoulder.

“Professor. I think it’s about time you let go of Nanba. Why not start by calming down?”

“Huh, why? I’m just trying to convey my genuine joy at meeting Nanba through a hug! There aren’t many chances nowadays to get a firsthand account from a student who received a chain letter on paper! Don’t you think it’s amazing, too, Fukamachi?!”

Takatsuki looked back at Naoya with his big eyes twinkling, making no move to pull away from Nanba. It was like dealing with a large dog that—with its tail wagging furiously—wouldn’t drop the toy in its mouth. Naoya tried again to reason with him.

“Don’t ask me to validate your behavior. Just let him go. He’s scared.”

“Yes, indeed, he is, isn’t he?! After all, he’s totally cursed! It’s natural to be afraid in that situation! Ah, I’m so envious!”

“No, it’s not the curse scaring him right now—it’s you!”

“Huh? What? So I am cursed?! And he’s jealous of that?! That’s so creepy! Let me go, let me go!”

Struggling in earnest, Nanba managed to escape Takatsuki’s embrace on his own.

Takatsuki sat back with a start. He seemed to be regaining his senses.

He lowered his hands—which had been hovering in the air as if still holding on to someone—in a hurry and looked abashedly at Nanba, who squeaked and tried to shrink back, folding chair and all. Face riddled with guilt, Takatsuki bowed his head.

“I—I’m so sorry, Nanba! It was rude of me to say that being cursed is wonderful and that I wish it were me! And I’m really sorry for hugging you out of nowhere like that; I must have given you a fright!”

“I-is he always like this, Fukamachi?!”

“Oh yeah, all the time. Once his common sense comes back, he realizes he’s just done something foolish and apologizes.”

“…You’ve gotta be kidding me.”

“That’s why he hired me part-time.”

“Wait, that’s what he needs you for?”

Well, Naoya also played the important role of navigator, in addition to being Takatsuki’s common sense.

He spoke to the professor, who was reaching for his cocoa with a despondent look.

“Since you’ve reflected on your actions, Professor, why don’t we get back on topic? What should Nanba do now?”

“Ah yes, right. Um, when it comes to the chain letter he received…”

Takatsuki took a sip from his cup, put it back down, and looked at Nanba.

“…To cut to the chase, I do think you’ve been cursed.”

“Huh?”

Nanba stiffened. Naked fear flashed across his face.

Takatsuki held out one hand slightly as if to calm Nanba.

“Come to think of it, we didn’t cover chain letters in this year’s class, did we? Now seems like a good time for me to talk about them a little,” he said, standing.

Grabbing what appeared to be old lecture materials and the fountain pen stored in his suit’s breast pocket, Takatsuki started scrawling something on the back of a piece of paper.

It was the contents of a typical chain letter.

You have been visited by an omen of misfortune. Within three days of reading this letter, you must send the same exact letter to five other people. If you don’t, you will have bad luck. It is said that when one man, Mr. H. from [city name], failed to pass this letter along, he was later struck by a car and killed.

Takatsuki showed the paper to Nanba.

“Was the one you received more or less like this?”

“…Yeah.”

“It’s an example of what we call chain letters. A chain-like connection is created when the recipient passes the same letter along to the next person. The contents of such letters may vary somewhat, but there are always instructions regarding a deadline for sharing the letter, keeping its exact wording, how many people you need to send it to, and a warning of what will happen if you don’t abide by the letter’s rules. They tend to open with that line about an ‘omen of misfortune’… Though, there’s also the ‘rod-letter’ variation.”

“Rod?”

“Yes. According to that type, if you break the chain, the rod will come for you.”

“…What does a rod have to do with anything?”

“The explanation is actually quite simple.”

As he spoke, Takatsuki wrote the characters for bad and luck in the margins next to the letter he had jotted down before. He scrawled them messily and so close that they were practically overlapping.

“See, if you write bad luck like this, it looks a bit like the character for rod, doesn’t it? The theory is that, at some point, someone with rather idiosyncratic handwriting probably wrote the letter like so, and the people who followed after that in the chain just kept copying the mistake. I’m sure there were people who noticed the error along the way, but passing along the letter unchanged is part of the rules. And above all, the idea of some unspecified ‘rod’ coming to get you must have made for an unsettling and interesting story. The potential for drawing interest is a major factor in whether folklore survives from generation to generation. Stories transform as they’re handed down. The same is true of chain letters as they continue to be rewritten. In fact—this malicious chain letter was originally meant as a blessing.”

“Huh? Really?”

“Yep. ‘This is a blessing for your good fortune’ used to be the opening sentence.”

Takatsuki’s voice was soft and gentle. He spoke in a slightly higher register for a man and with a strange clarity.

Nanba’s expression, somewhat reticent toward the professor until then, was gradually shifting. Coming away from the back of the chair, which he had been firmly pressing himself into, Nanba leaned forward a bit as he followed along. It was just like one of Takatsuki’s lectures. Students who usually dozed off or fiddled with their phones during class almost always paid rapt attention when Takatsuki was teaching.

The man was easy to listen to, and his lectures were fascinating. It wasn’t just his looks that made his courses popular.

“The ‘blessing’ letter caused such a stir that it was even picked up by a newspaper in 1922. ‘If you write this message on nine postcards and send them out, you will have good luck in nine days. But if you break the chain, you will suffer terrible misfortune.’ ‘You must complete this task within twenty-four hours of reading the postcard.’ ‘This message began with an American soldier and has circled the globe nine times.’ Tons of households were receiving postcards that said things like that. You’d probably be alarmed if you got such a letter, right? What’s more, the postcard says you’ll have good luck if you pass it on, but terrible misfortune if you don’t. And so, to ward off misfortune and invite good luck, everyone followed the instructions of the message. But what do you think the result of that was? If nine people each send out nine postcards, that’s eighty-one copies. If everyone who received one of those makes yet another nine, the total would grow to an outrageous number in no time. The sudden, dramatic explosion of the letter in society ultimately resulted in a police crackdown.”

“No way! Did people get arrested just for sending a letter?”

“Yes. People could be detained for twenty-nine days for ‘deceiving others via the dissemination of unlawful information, groundless rumors, or false reports.’ The letters were such a huge trend that they became a societal issue. Now—you may be wondering where these letters came from in the first place. I think it would be correct to say that they probably originated overseas rather than in Japan. After all, it mentions starting with an American soldier, and one such postcard—written in English—was found to have been postmarked in London. Most likely, the letter was popular in English-speaking countries first, then someone translated it into Japanese and spread it here. Though there have also been reports of things like this in Italy, so I don’t think it was limited to English-speaking countries in particular.”

At that point in the story, something occurred to Naoya.

He raised his hand slightly to get Takatsuki’s attention.

“Professor, the fact that it was translated into Japanese means the person behind it either knew a foreign language or exchanged letters with people from other countries, right? But people like that weren’t very common at the time, were they?”

“Yes, well spotted, Fukamachi. Indeed, in those days, chain letters were popular among adults, rather than young people. There are even documented cases of ones sent by high-ranking officials in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and members of the House of Peers.”

Takatsuki sounded like he was really enjoying the subject at hand.

“Grown men and women of high rank and education—hoping for their own good fortunes and fearing the contrary—copied the chain letters they received and mailed them out to other people. Curious, isn’t it? But the people of this country have long believed that blessings and curses go hand in hand. If they hear that breaking an inexorable chain of good luck will result in bad luck, they’re going to believe it. Chain letters preyed expertly on the sensibilities of the Japanese people.”

That was why, despite being regarded as a societal problem and coming under police scrutiny, chain letters didn’t disappear. Their survival from the Taisho period, through the war, and into the present era was fine proof of it.

But just as most stories transform as they are passed down, the “blessing letter” also changed over time.

Minor changes in its wording appeared, and variations in the deadline and number of recipients were created. Those were still just trivial differences, though. The letter’s original nature was still preserved.

In the end, however, the letter would go through a definitive transformation.

“Eventually, the ‘bad luck’ version derived from the original gained popularity. The line about ‘a blessing for your good fortune’ was scrapped, resulting in a message that implored the reader to pass it along to others simply as a means of avoiding misfortune. These chain letters saw quite a surge in the 1970s, it seems, spreading to children as well. Just like that, what had started as a good luck message exchanged between adults ended up as a curse primarily transmitted by kids. At that point, the letter once more had a slight change in form. Sending it by mail was no longer a required part of the process. Within the closed ecosystem of a school, the mail service is unnecessary, after all. A student simply had to write the letter on a scrap of notebook paper and leave it in someone’s shoe locker or desk. That alone allowed the chain to continue.”

Takatsuki took another sip of his sugary cocoa.

A memory washed over Naoya as he sat there listening.

There had been a period during Naoya’s elementary school days when chain letters were all the rage.

Once, he had even received one himself. At the time, someone even went as far as to leave such a letter on the homeroom teacher’s desk. Furious, their teacher had lectured them about it for ages before banning chain letters altogether.

“Paper chain letters declined as e-mail gained traction. Though, as we can see in cases like yours, Nanba, they come back into vogue now and then. You see chain letters sometimes in e-mail and on social media, too. It’s common on Twitter, for example, to see a post with a rather scary image attached that says something like, ‘Once you see this tweet, if you don’t retweet it within ten seconds, you will be visited by a demon in the night.’ I think the Twitter example, in particular, is a departure from its predecessors in character, though. There’s quite a large difference between sending a message to an unspecified mass of people with the click of a button and personally choosing recipients for things you wrote by hand. Sending a chain letter means having to decide who you want to spring a curse on. If you can ward off your own misfortune, it doesn’t matter if someone else ends up in bad circumstances. That sort of thought process is always involved in such things, to some extent… That’s why a chain letter is unmistakably a vehicle for cursing someone.”

Takatsuki’s words jostled loose another memory for Naoya—about the time he found a folded-up chain letter inside his elementary school desk.

The letter had appeared out of nowhere, and while Naoya had been creeped out by it, he was also desperate to know who on earth would have left it for him.

Naoya tried to recall how the incident had ended.

If his memory was correct, the letter had instructed him to pass it on to four people within forty-eight hours.

Yes, that was it—after a great deal of thought, he had left copies of the letter inside the desks of four other students.

The recipients, Naoya thought, had been kids he hadn’t really liked or gotten along with. He had no idea what they had done after discovering his letters, but he wouldn’t be surprised if they had all done the same as him and continued the chain.

And yet Naoya remembered that when he was sliding the letters into the desks, his hands shook.

He had been afraid of being seen by someone, certainly, but—more than that, Naoya had been petrified of what the letter might mean for the children he was giving it to.

With a thunk, Takatsuki put his mug back on the table.

“Chain letters are curse-bearing objects. But then—what exactly is a ‘curse’ to begin with? What do you think, Nanba?”

“Huh? Umm…”

Nanba hesitated, caught off guard by the question.

Cocking his head lightly to the side, Takatsuki looked at him.

“You thought you might have been cursed, right? Why was that?”

“Because…bad things—stuff that doesn’t usually happen—kept happening again and again…”

“And because the only explanation you could think of for that was the chain letter?”

“…Yeah. Exactly.”

Takatsuki nodded at Nanba’s reply.

“A curse is made up of some sort of trouble and the source of that trouble. When something bad happens, people want to know why it happened. But there isn’t a clear explanation for every incident that occurs. Some events can’t be explained at first glance, and many things can be chalked up to simple coincidence. But the inexplicable makes us uncomfortable, doesn’t it? Things we don’t understand make us anxious. The ‘curse’ framework offers meaning in such cases.”

The professor’s words were similar to ones Naoya had heard from him many times before.

The mysterious comprises two elements: phenomenon and interpretation. It was practically Takatsuki’s catchphrase.

People feared what they could not explain.

It was human nature to interpret the cause of a frightening event. They wanted to give it a reason, to attempt to understand it. Even if the result was a somewhat unrealistic conclusion, it was better than continuing to be in the dark. Thunder was caused by a drum-toting demon who soared through the sky; rustling sounds at supposedly empty riverbanks were made by demons washing their red beans. Many Japanese monsters and apparitions had been born from such interpretations.

Curses were a form of the mysterious, too.

“Unusually bad events happened one after the other. If you tell people about that—even if you don’t mention the chain letter—there’s bound to be some percentage of them who respond jokingly with ‘Sounds like you’ve been cursed.’ They wouldn’t think for a second that their words would, in fact, invoke the curse to begin with.”

Takatsuki chuckled.

“Curses only come into existence when someone recognizes them as the cause of some misfortune, you know. After all, they’re the ideal explanation for an incomprehensible disaster. Misfortunes can be ascribed to the vague idea of a curse, but it’s better to have something concrete to pin them on, like a straw doll, an amulet, or a chain letter. Conversely, a straw doll or chain letter without some corresponding misfortune won’t lead to the establishment of a curse. Likewise, if no one thinks of the problems as a curse, no curse will materialize.”

Takatsuki’s hand shot out suddenly.

He gripped Nanba’s still-untouched mug of cocoa from the top, lifting it up.

“Now then, Nanba. As for your situation…”

Setting the cup back down between himself and Nanba with a clunk, Takatsuki continued.

“You experienced a variety of unlucky incidents over the last few days. Narrowly avoiding having your head smashed in by a flowerpot, almost getting shoved down the train station steps, losing your keys, your heat malfunctioning, your alarm clock not going off, falling down your apartment complex stairs, being late for your exam. Certainly, that many bad things happening in such a short period of time is rare. But any one of them could easily have happened over the course of a normal day. However—”

Next, he picked up his own mug, then plopped it down heavily right beside Nanba’s.

“But you looked for a cause behind your bad luck, and you found it in the chain letter.”

Waving his hand lightly over the pair of mugs, Takatsuki looked at Nanba.

“Thus, with a corresponding relationship established between misfortune and source, the curse was born.”

“Oh…”

Nanba’s mouth fell open.

His gaze flicked between Takatsuki and the mugs several times before he put one hand to his head.

“Huh? Wha—? Um, does that mean I put the curse…on myself? You’re saying I wouldn’t be cursed if I didn’t blame my bad luck on the chain letter?”

“Yes, if we try to interpret what happened to you through a strictly pragmatic lens. I think it’s likely that the first two events—the flowerpot and the station stairs—were frightening enough to give you quite a shock. Perhaps, as a result, your mind was elsewhere, and you dropped your keys. Maybe you simply forgot to set your alarm that night, so it didn’t go off the next morning. And maybe, because your heat was broken and your apartment was freezing, you slept poorly, and that’s why you fell down the steps. Once you get into a negative mindset, it’s hard to break out of it, and you end up attributing all the bad things happening around you to the curse. As you get ever more depressed about the situation, it’s only natural that you won’t perform at your best, no matter what you do. That’s probably why your exam didn’t go well. By the way, about the broken heating—was there really no prior warning that it was going to fail?”

“Huh? No, really, just out of nowhere yesterday— Oh, actually, now that you mention it…I do feel like it was acting up a bit a few days ago…”

Nanba’s muttered reply trailed off.

Naoya blinked in surprise.

Both times Nanba recounted the story—first to Naoya, and then to Takatsuki—he had said the heating system broke out of the blue. He hadn’t been lying. At the very least, he must have believed that was the truth when he said it.

Takatsuki, likely taking note of Naoya’s expression, chuckled again.

“The human memory is a fickle thing. Occurrences that must have taken place are forgotten entirely to make sense of inner narratives. It’s not quite the same thing as lying. You could call it memory revision, and it happens frequently.”

That’s how it is, huh? Naoya thought.

Something could become the truth to someone, even if it differed from what the person in question actually experienced.

Still confused, Nanba stared at the metaphorically positioned mugs.

“Uh. Umm. So it’s all just a big misunderstanding on my part…? Wait, if the curse and everything is just my misunderstanding, does that mean I’m in the clear?”

“Well, no? As I said earlier, the minute you had the thought that you had been cursed, the curse was, in fact, established.”

“Huh…?”

“And there’s no way for you to lift that curse by yourself.”

Takatsuki was practically beaming. He slid the Great Buddha mug—which had served as the symbol for “misfortune” until then—toward Nanba, saying, “You can have this back now.”

Nanba’s mouth was hanging open again.

“Wh…? Whaaat? Then—what—am I gonna die, after all?! Can’t you help me?!”

“Um, Professor, whatever the circumstances, leaving things like that is…”

Naoya had to interject. He never thought Takatsuki would admit defeat to the curse. That meant Nanba was without hope.

But Takatsuki picked up his own cocoa again, took a long sip, then spoke.

“Calm down. I’ll do a purification ritual for you.”

“P-purification? You can do that, Professor?! Really?! Please, please do it! Right now, please!”

It was Nanba’s turn to cling to Takatsuki, who just barely managed not to spill the contents of his mug. He turned in distress to Naoya, who had no choice but to pry his classmate away from the older man.

Takatsuki met Nanba’s pleading eyes with a bright smile.

“Yes, don’t worry, we’ll get started immediately. But before that, Nanba—drink your cocoa.”

“Huh? But—”

At Takatsuki’s instruction, Nanba picked up the Great Buddha mug. He gulped down the drink in a hurry, his features plainly broadcasting his curiosity over whether it would have some sort of magical effect.

When he was finished, Nanba let out rather deep sigh.

“…Wow, that was sweet.”

“But don’t you feel a little better?”

“Yeah, I do.”

“Sweet things will do that.”

Patting Nanba lightly on the shoulder—which had sunk slightly as if he was exhausted—Takatsuki stood up.

Strangely, he returned to the table holding some children’s origami paper, taken out of the cardboard box at the bottom of the bookshelf, where snacks and other miscellaneous things were usually stored.

Sitting back down, Takatsuki got to work folding something with his long, slender fingers.

“Do you have some sort of paper on you, Nanba? Doesn’t matter what type. Even looseleaf.”

“Oh, yeah, I have some looseleaf.”

“Good. Then I want you to try writing a copy of the chain letter you received. Whatever you remember is fine, but do try to make it as accurate as possible.”

“Huh?”

With a dubious look on his face, Nanba took some paper and a pen case out of his bag.

Naoya turned to Takatsuki.

“What are you planning to do, Professor?”

“Nanba’s letter said he had to send it to five people within three days, right? He found the letter the day before yesterday. The deadline hasn’t passed yet. So in order to avoid the chain letter’s bad luck, Nanba is going to pass the letter to five more people.”

“Who are the five?”

“I’m making them right now.”

As he spoke, Takatsuki’s hands were hard at work on whatever he was folding.

He was making little paper men.

“These,” Takatsuki said, “are katashiro—paper dolls used in purification rites. Since olden times in this country, it’s been customary to have a paper doll take on the burden of impurity in order to free the afflicted. In a similar vein, we should be able to have the paper dolls take on the chain letter’s curse. You’re going to address your letters to them, Nanba. Even though they’ll receive the letters, they won’t be able to pass them on to anyone else. The chain will end here. Ah—it’s hard to address a letter to someone without a name, isn’t it? Let’s go with, in order, Tarou, Jirou, Saburou, and Shirou.”

Takatsuki wrote the name of each doll on its chest.

Watching him, Naoya interjected again.

“Professor?”

“What is it, Fukamachi?”

“You’re missing one.”

Naoya gestured to the paper dolls.

They were all made from different colored paper—blue, red, purple, green. But there were only four.

“The letter called for five recipients… You need one more.”

“Yeah, well, I only had four sheets of origami paper. Therefore, I want you to address the last letter to me, okay, Nanba?”

“Huh?”

Nanba looked up from the looseleaf paper he was writing on to gawk at Takatsuki.

“I—I can’t do that! You might end up having bad luck!”

“Yep. That’s what I’m hoping for.”

“What?! What are you saying?!”

“The thing is—I want to experience the supernatural firsthand so badly I can’t stand it. I know what I said to you before, but there is a possibility that the chain letter will actually bring some misfortune. If I can verify that myself, it would be a highly valuable experience!”

“No, nope, no way! Nuh-uh, not even if you look at me with those puppy-dog eyes! F-Fukamachi, is he serious? Come on, can’t you get him to reconsider? This is crazy.”

“Well… I mean, this is just how he is…”

Both Naoya’s response and his face were noncommittal.

Takatsuki really did want to experience something supernatural.

Determining whether real monsters existed in the world was the reason behind Takatsuki’s research, and as he often said, if there were monsters out there, he wanted to encounter one no matter what.

Smiling, Takatsuki lined up the paper dolls in front of Nanba.

“It’s okay. There’s no need to feel bad. Unlike you, I won’t associate any misfortune that happens with the chain letter. However, if some truly inexplicable disaster was to occur, it could become valuable data regarding the supernatural implications involved with things like chain letters! If anything, as a researcher, I would be thankful for the opportunity! So please, by all means, address one of the letters to me!”

“But! But—!”

Nanba looked terribly distressed.

In the end, after repeated urging, Nanba put Takatsuki’s name on a letter. Glumly, he put his pen case and the remaining looseleaf back inside his bag.

“Isn’t this great, Nanba?” Naoya said. “Your curse will be lifted now.”

“Yeah… But, like, giving the curse to Professor Takatsuki is…”

“He said himself that he wants that to happen, so don’t worry about it.”

“But still… Besides—I mean…”

“Besides what?”

Naoya cocked his head to the side, and Nanba paused for a moment.

Then, with a sigh, he continued.

“Besides, the fact that someone sent me a chain letter in the first place is, like, pretty hard to deal with… Because, like Professor Takatsuki said, doesn’t that mean the kid who sent it to me didn’t care if I had bad luck?”

A chain letter was a vehicle for cursing another person.

The act of sending one inevitably involved being fine with the idea of someone else suffering for one’s own sake.

Even as an elementary school student, Naoya had been quite shocked to receive a chain letter. He spent some time wondering who on earth had left it in his desk—and whether it was someone who hated him.

It was possible that, more than bad luck, chain letters brought feelings of ill will with them. That was why people who received them felt troubled and were more susceptible to the curse.

“Ah, that reminds me, I forgot to ask. Nanba?” Takatsuki, who had lined the four paper dolls up on one of the bookshelves, turned toward the center table. “Do you have any idea who might have sent you the chain letter?”

“Huh…?”

Nanba looked over at the professor.

Then he said—

“N-no, I don’t. Not a clue.”

Suddenly, Nanba’s voice warped. The distortion made it jump wildly in pitch, as if some kind of device was applying a chaotic filter to every word.

Startled, Naoya reflexively covered his ears.

Nanba looked at him in alarm.

“Fukamachi? What’s the matter? Are you okay?”

“Oh… Um, it’s nothing…”

Naoya glanced at Takatsuki as he replied.

The other man was watching him closely. It must have come across loud and clear that Nanba had just told a lie.

“Nanba, you—”

But just as Takatsuki started to speak, the bell rang.

Nanba’s head whipped around with a start toward the clock hanging on the office wall.

“Crap, the repairman is coming to fix my heat today! Um, Professor—I have to go now, but I really appreciate your help! I’m really sorry if anything happens to you! Your class was really fun, so I’ll enroll next year, too! Fukamachi, thanks to you as well, seriously! Later!”

Donning his coat and grabbing his bag in a hurry, Nanba bowed his head to Takatsuki and Naoya several times, then rushed out of the room. The door closed behind him with a bang, and they listened as the sound of him dashing down the hall grew ever more distant.

“…He’s so loud,” Naoya muttered before downing the last bit of his coffee in one gulp.

Smiling, Takatsuki tucked the letters Nanba had written into a plastic sleeve.

“He’s energetic, honest… Quite a nice boy, wouldn’t you say?”

“I’d say he’s just noisy.”

“Well, most students are.”

Takatsuki returned to the table. Rather than the chair he had been using before, he lowered himself into the seat right next to Naoya, looking exceptionally pleased.

“…What’re you making that face for?”

“No reason. I was just thinking it’s rare for you to bring a friend here.”

“He’s not a friend. We’re just in the same language class.”

“You would say that, Fukamachi. But I remember seeing the two of you together several times. That’s right—you ate lunch together the other day, when one of the cafeteria options was fried mackerel.”

Turning his face away, Takatsuki gazed into the air as if he was seeing the scene in question.

“Don’t search your memories for something like that.”

Naoya, exasperated, watched as Takatsuki appeared to mentally scan his brain for things he had seen around campus in the last year.

The professor had an unusually powerful memory and great eyesight, to boot. Consequently, everything he saw was stored in his mind as a clear image. As he was currently doing, Takatsuki could sift through his memories at will. It seemed he could also zoom in on the details of what he remembered.

“I saw you talking with a handful of people. I’m glad you’re making friends as you should. That’s a relief.”

“Like I said, he’s not my friend. I mean, it’s not like he’s a bad guy, but…”

Avoiding returning Takatsuki’s amused grin, Naoya placed his empty mug on the table.

“…Nanba doesn’t really lie, most of the time. So it’s easy for me to be around him.”

Naoya’s ears heard the lies people told as distorted sound.

Spending time with liars, constantly being subjected to the warped words coming out of their mouths, was agony for Naoya. The sound alone made him feel sick.

Even if that wasn’t the case, people lied on a regular basis.

Depending on the situation, even those who were usually truthful would lie on occasion.

Takatsuki rested his elbows lightly against the table.

“That makes sense. Plus, I think he seems very kind. Just before he left…he told a lie, didn’t he?”

“…Yeah.”

Naoya nodded.

“He thinks he knows who sent him the letter.”

“And yet,” Takatsuki replied, “he told us he didn’t. Even though we don’t know who it is, he instinctively covered for them.”

Nanba certainly was the type to do that. He was unguarded and easygoing but also surprisingly mindful of others. It was all the more reason for him to be upset about being targeted by the chain letter.

“By the way, Professor. That was on purpose, wasn’t it? Only making four paper dolls.”

That thought came rushing back to Naoya, and he cast a slight glare in Takatsuki’s direction.

“Even if you didn’t have more origami paper, you could have used something else. If all you had to do was make a paper doll, even looseleaf or leftover class materials would have sufficed. But you made sure the last letter got addressed to you. Did you really want it that badly?”

“Well, that is a part of it. But look—it’s because Nanba is such a nice kid.”

Takatsuki’s gaze slid over to the four dolls on the shelf.

“He felt quite badly about it, didn’t he?”

“Yeah. It really bothered him.”

“His concern, when it comes down to it, is a result of him thinking, Oh no, I’ve given my curse to Professor Takatsuki. That means the purification was a success. Nanba’s curse is lifted.”

Oh, Naoya thought. I see now.

Nanba’s belief that he himself was cursed was the reason behind the curse.

Thus, his writing chain letters to the dolls wouldn’t have any effect if there was even the smallest doubt in his mind about whether that would end the curse.

That was why Takatsuki deliberately gave Nanba something to feel guilty for.

It made sense, but—

“Still, Professor. I think it’s seriously weighing on him.”

“Yep, which means it’s a good thing he doesn’t have to worry about the curse anymore, right?”

“No, not that… I’m worried that the idea of bringing misfortune to someone he knows will genuinely make Nanba sick with anxiety. He’s that nice.”

“Huh?”

Just like Nanba’s had before, Takatsuki’s mouth popped open in surprise.

Then, covering his mouth with one hand, he whispered, “Oh dear.”

He continued in a slightly louder voice.

“I’m sorry. That thought hadn’t occurred to me. I see… So Nanba is that sensitive. I apologize; I’m not very cognizant of others’ feelings, so I didn’t think…”

“You don’t need to look that apologetic over it… I’ll check up on Nanba later.”

“Yes, good, it makes more sense for you to do it than me. Oh—but the point is, even if I encounter some bad luck, it’s okay! If it comes to that, I’ll probably be fine. My way of thinking about it is different from Nanba’s, so I won’t get caught up in the same curse.”

Smiling, Takatsuki held up a finger as if to underline his point that everything was okay.

“For someone in your field of study, Professor, you don’t seem to put much stock in curses.”

“I am a researcher, after all. I can’t just go around accepting unrealistic explanations for things that have logical interpretations.”

“But you do hope for the unrealistic option to be true to some extent, don’t you?”

“Well, yes. Like in this case, for example. I certainly can’t make any definitive claims about Nanba almost being hit by a flowerpot and shoved down the stairs being nothing but pure coincidence! Couldn’t there be something that drew those unlucky accidents to him? Not that such a thing would be easy to prove, though.”

“So you’re saying if something bad was to happen to you after this, it wouldn’t necessarily be because of the chain letter?”

“No, but of course if I was to walk outside right now and suddenly get hit by a car, I might blame it on the letter.”

Takatsuki glanced at the clock.

“Hey, Fukamachi. Do you have any plans for the rest of the day?”

“Um, no, not really.”

“Great. In that case, do you want to come be my lookout so I don’t get run over?”

“Excuse me?”

Grinning, Takatsuki stood up, towering over Naoya as he spoke.

“A request came in, actually. I wasn’t planning on telling you about it since it’s exam season, but if you’re not busy, I’d love for you to accompany me.”

Apparently, a middle school girl from Koto City was the source of the current request submitted to Takatsuki’s website, Neighborhood Stories.

“The girl’s elder sister took my class this year, it seems, so that’s how she knew about me and the site.”

They didn’t have much time before Takatsuki was scheduled to meet with the girl, so he explained the situation to Naoya on the move.

Wrapped up in a blue scarf and an expensive-looking gray overcoat, Takatsuki led the way from campus to the train station. Normally, the professor was bound to get lost when going somewhere for the first time. But having been to the scheduled meeting place before, he originally planned on speaking to the girl without Naoya.

At this time of year, the heating inside the trains was almost too effective at warding off the outside chill. As soon as they stepped into the train car, Naoya had to take off his fogged-up glasses and wipe the condensation from the lenses.

“Is this the type of request you would be able to handle without someone there for common sense? As in, does it relate to a topic you’re not particularly interested in?”

“Not at all! I’m really excited about this one!”

Takatsuki answered in a cheerful tone, his eyes glittering with anticipation. When he was like this, he never failed to remind Naoya of Leo, the golden retriever he’d had as a child. Faced with his favorite toy or treats, Leo would radiate excitement the same way, though he was usually able to follow the “wait” command. Takatsuki ordinarily failed at that task, which was a problem.

“So what’s the story this time?”

“According to the e-mail, the girl’s friend may be cursed.”

“Another curse? Don’t tell me it’s a second chain letter.”

“Well, actually, it’s one even I’ve never heard of. She called it the Curse of Marie-san in the Library.”

“There are urban legends you don’t know about?”

“Recently created stories that circulate in hyperlocal environments don’t make their way to me very often. Miss Ruiko is well-versed in internet folklore, so I asked her about it just in case, but she didn’t seem familiar with it, either. That means this might be a good opportunity for us to collect information on a new urban legend!”

Takatsuki’s voice was still brimming with happiness.

The meeting place was in front of a library in Koto City, where the girl’s friend had supposedly been cursed.

They exited the train, and after a short walk, a park came into view. Nearest to them were rows of colorful playground equipment, and several large trees rose up out of the ground beyond that. Partially hidden behind the trees sat an old-fashioned, Western-style white building—the library, evidently.

Sitting on the wooden benches outside the library, huddled together as if to stave off the cold, were two girls in school uniforms. Catching sight of Takatsuki’s face as he approached, the short-haired girl sitting on the right tapped the other girl—whose hair was in braids—on the shoulder. They started talking, their conversation loud enough for Naoya to hear.

“That’s him! It has to be!”

“Huh…? Really?”

“Yes, he’s just like my sister said! Tall, young, and really handsome!”

Apparently, being handsome was considered a defining characteristic. In Naoya’s case, people either described him as a plain-looking four-eyes or didn’t find anything about him to be noteworthy.

When Takatsuki and Naoya made it to the bench, the girls shot to their feet. Both of their faces had flushed a charming shade of pink from the cold.

The short-haired girl looked up at Takatsuki as she removed her fluffy pink earmuffs.

“U-um, Professor…Akira Takatsuki?”

“Yes, that’s me, from Seiwa University. This is my assistant, Fukamachi. And you must be Miss Akagi, the one who sent me the request?”

The girl responded to Takatsuki’s gentle smile with an enthusiastic bow of her head.

“Yes! I’m Yuzuka Akagi! This is my friend Miya Motohashi! It’s nice to meet you!”

“N-nice to meet you…”

At Yuzuka’s side, the girl with the braided hair also bowed her head. Naoya wondered if it was this girl—meek-looking, bespectacled Miya—who had been cursed.

The girls explained that they were in their first year of middle school and had been friends since elementary school. Appearing to be very different people at first glance, the girls were in the same class and still quite close.

The first order of business was to hear the girls’ story, but disrupting the requisite silence of the library wasn’t a good idea. Takatsuki bought some hot drinks for them from a nearby vending machine, deciding they could talk at the bench.

“Could you start by telling me what the Curse of Marie-san in the Library is about?”

Yuzuka was the one to answer Takatsuki’s question.

“I heard about it from the upperclassmen in my club,” she said, pressing the warm bottle Takatsuki had given her to her cheek.

“Some of the books in this library have something written in them that looks like a cipher.”

It was said that the writing appeared in bloodred ink in the corners of the books’ pages.

The cipher was made up of four combinations of digits. But if someone was unlucky enough to come across one, under no circumstances should they try to solve it. Rather, as soon as a person saw the cipher, they were supposed to close the book and chant the following sentence three times: “Please forget, Marie-san.”

If they didn’t, they would be cursed by Marie-san.

“If you do end up cursed, you might be able to save yourself by cracking the cipher within three days, but that’s not for certain. The other possibility is that when you figure out the code, Marie-san will appear right in front of you. The seniors in my club told me they don’t know which one is the truth. Either way, if you see the cipher, you’re in trouble, so they said it’s best to avoid this library altogether.”

“Ah, was there anything in the story about who exactly this Marie-san is?”

Takatsuki’s query appeared to remind Yuzuka of something.

“Oh, right! I forgot to tell you the beginning of the story! Um, so I guess a high school girl named Marie-san used to come to this library a lot, but she died in an accident. Because she loved books so much when she was alive, she started to haunt this library after her death.”

“I see, so the story is predicated on the conditions that, first, there’s a ghost in the library, and second, there is a cipher written by the ghost.”

Takatsuki nodded to himself as if in understanding.

Naoya tilted his head.

“But isn’t it unusual for a ghost to do something like write secret codes? I’ve never really heard of that happening.”

“True enough. That element alone is oddly off theme. Interesting—and so you found the cipher, I assume?”

Pivoting his gaze to Miya, Takatsuki addressed the latter part of his statement toward her.

Clutching her can of hot chocolate with both hands, Miya nodded.

“I like reading…so I borrow books from this library a lot. Then, two days ago, I was reading a library book at school, and I noticed some weird writing in the page margins. All kinds of people take out books from the library, so sometimes I do find scribbles in them, but…this one was strange, even for a random doodle, so I showed it to Yuzuka since she was nearby. I asked her what she thought it was, and…”

“At the time, I had just heard about Marie-san from my seniors. So I was like, uh-oh, this is bad. But when I asked Miya, it turned out she didn’t know about Marie-san and didn’t do the chant, either.”

Miya’s head drooped.

“That story is popular in Yuzuka’s badminton club, I guess, but no one in the choir club I’m in has heard of it…”

“I’m sorry. I should have told you about it sooner.”

Yuzuka reached out to pat Miya’s arm with concern.

Looking down at the girls, Takatsuki asked Miya another question.

“Do you have the book with you?”

“Ah yes, here it is.”

Miya retrieved a hardcover book from the bag at her feet. She handled it with the kind of extreme caution normally reserved for things like explosives. The cover read, Science Fiction of the World, the Complete Collection, Vol. 16.

Gently, Takatsuki took the book out of Miya’s hands.

“Is the page in question the one that’s been bookmarked?”

“Yes, but… Um, you’re going to look at it?”

“Oh yes, don’t worry. I would be delighted to be cursed. Oh-ho—so this is Marie-san’s cipher?”

Takatsuki had the book open to the marked page. From the side, Naoya peered in at it, too.

Something was written in red ink in the corner of the page, just as described by the story.

It probably contributed to the creepiness of the story to exaggerate by saying the ink was “bloodred,” when in reality it was likely just written in normal red ink. In slightly rounded handwriting, it said Next is 933-2-42-153. Naoya frowned at the surprisingly long string of numbers. What were they meant to represent? Perhaps it was part of a series of codes, since the word Next was there as well.

Miya raised her head. Her fingers squeezed around the can of hot chocolate.

“…Um, I…don’t really believe in the Marie-san story. I’m not a little kid. I know it’s just supposed to scare people. But the idea of being cursed did get to me a bit, after all. I haven’t been able to sleep…”

Naoya had indeed noticed that Miya’s face was pale, and dark circles had bloomed under her eyes. It brought to mind the way Nanba had looked when Naoya first encountered him earlier in the day—it was the blatantly anxious, agitated face of someone who thought they might be cursed.

“—It’s okay, Miss Miya.”

Takatsuki bent down slightly with a kind smile so he could make eye contact with the girl, who stared back up at him.

“You don’t need to be frightened. After all, your situation is actually rather incredi— Ack!”

“Professor, you cannot touch a middle school girl,” Naoya hissed into Takatsuki’s ear.

He had also yanked back on the professor’s arm as it started to reach out toward Miya. It was a good thing Naoya had tagged along, he thought. If Takatsuki had grabbed on to Miya like he did to Nanba earlier, he would definitely be reported to the authorities.

Looking down at Naoya, Takatsuki pouted.

“I wouldn’t! Even I know not to hug preteen girls!”

“Then what were you thinking of doing just now?”

“…Patting her head, maybe.”

“You just met her, so you should probably hold off on that.”

Takatsuki pulled back at Naoya’s words, looking disappointed. Miya herself muttered something that sounded like “Aw, I wanted him to pat my head,” but Naoya pretended not to hear.

“So what’s the plan, Professor?”

As if mulling something over, Takatsuki stroked his chin with one hand.

“Yes, good question. I find it a bit curious that the badminton club knows Marie-san’s story, but the choir club doesn’t.”

“Huh?”

“It’s odd, isn’t it? They’re in the same school.”

Takatsuki looked at Yuzuka.

“Have you heard anyone outside of the badminton club talking about Marie-san?”

“I’m not sure… Oh! But when I mentioned it to some girls in our class, Miho and Kanna, they said they know the story! They’re in the basketball club.”

“I see. And do you come to this library often, Miss Yuzuka? What about the seniors who told you the story—or the girls in your class?”

“I don’t, really… Pretty much only for some school assignments and book reports. I would guess it’s probably the same for my seniors. In general, if you need to check out a book, the school has its own library, so I don’t think there are a lot of students who go out of their way to come to this one… And Miho and Kanna don’t seem like the type to read for fun.”

“I’ve never seen either of them here,” Miya offered.

Evidently, the story about Marie-san was popular with kids who weren’t familiar with the library in question.

After taking another long moment to think, Takatsuki turned to Yuzuka again.

“Miss Yuzuka, you heard the story from the older students in your club, yes? Would you be able to find out where those students heard it from?”

“Huh? Oh, yeah! I’ll message them on LINE!”

Nodding, Yuzuka took out her phone.

Just then, the library door opened, and two women who looked like college students walked out.

As the pair made to pass by their group, Takatsuki called out to stop them, presenting them with his business card.

“Pardon me. I’m Takatsuki, an associate professor at Seiwa University. I study ghost stories and urban legends. Could I have a few minutes of your time?”

At first, the women looked wary. But the moment Takatsuki smiled at them, they stopped walking. There were times when the professor’s elegant features and gentlemanly demeanor came in quite handy. His title probably helped a bit, too.

The women looked over Takatsuki’s business card.

“Oh, I have a friend who goes to Seiwa. What was it you wanted to talk to us about?”

“Also, you say you’re studying ghost stories? Do they have classes like that at your school?”

Takatsuki nodded and grinned.

“Yes, indeed. I’m actually currently in the middle of collecting data about a ghost story. Do you two come to this library often?”

“It’s nearby, so yeah, pretty often.”

“And have you ever heard the ghost story concerning this library and a girl named Marie-san?”

“Um, what? No, I haven’t.”

“Neither have I.”

The pair shook their heads.

Takatsuki thanked the women, and they walked off, giggling.

While Takatsuki had been talking, Yuzuka seemed to have received a reply from her seniors. She held out her phone.

“They said they heard the story from friends in their class!”

“Then, would it be possible to find out where those friends got it from? Once we know that, I’d like to keep tracing the chain back, if we could.”

For a moment, Takatsuki’s immediate response seemed to catch Yuzuka off guard. Then she started typing away on her phone again, likely asking her seniors for more information.

As Yuzuka tried to track down the origins of Marie-san’s story through her smartphone, Takatsuki approached passersby and people going in and out of the library with the same questions he had posed to the two college girls.

But not one of them had heard of Marie-san, and none of them were lying about it, either. They were all genuinely unfamiliar with the story.

Naoya was confused.

The situation felt very strange to him. Marie-san’s story took place in this very library, but no one who actually frequented the library had any knowledge of it.

“What do you think this means, Professor?”

“Well, most likely—I think Marie-san’s story has only just recently started circulating at the girls’ school.”