In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

I got another phone call today.

When I heard the hysterical ringing, like the caterwauling of tomcats, my hair instantly stood on end, my body started trembling, and I felt like the hot nails of pain and discomfort clawing at my stomach would send me over the edge.

The world would be so much more peaceful if there were no phones.

The phone only spits out ugly words, dirty words, cursed words.

Their clinging, spiteful, unrestrained, mean voices thick with miasma fill a world that should be beautiful with garbage.

I wish all these people who make the phone ring so obnoxiously would just die!

What is true happiness?

In one corner of the universe, there was a boy who pondered that.

My happiness was Miu.

Before, just having Miu by my side made my heart leap, and when Miu crafted stories in her bright, clear voice, everything around us glittered with rainbows.

“I’m gonna be a writer. Tons of people are going to read my books. It would be awesome if that made them happy.”

In a warm dappling of sunlight through the trees, her ponytail swaying, Miu talked about her dreams for the future with gleaming eyes.

“You’re the only one I told, Konoha. Because you’re special.”

She whispered in a pretty voice, tilting her head like a small bird and looking straight at me with teasing eyes.

“What’s your dream, Konoha? What do you want to be when you grow up?”

Miu’s face came close enough to kiss, so I was sweating horribly and didn’t know which way to look anymore.

I thought about it carefully, wringing my brain out with both hands until I began to grow desperate, knowing that I had to answer her. My cheeks grew hot, and finally—

“I want to be…a tree.”

When I said that, she guffawed at me.

Three years have passed since then.

I lost my holy land, and Miu went into hiding. After a dark period living as a recluse, I became a normal high school student.

Now that my second year of high school was nearing its end, still ignorant of the meaning of happiness and still not a tree, I wrote a snack story for the book girl in the clubroom that had been dyed a soft golden color in the sunset.

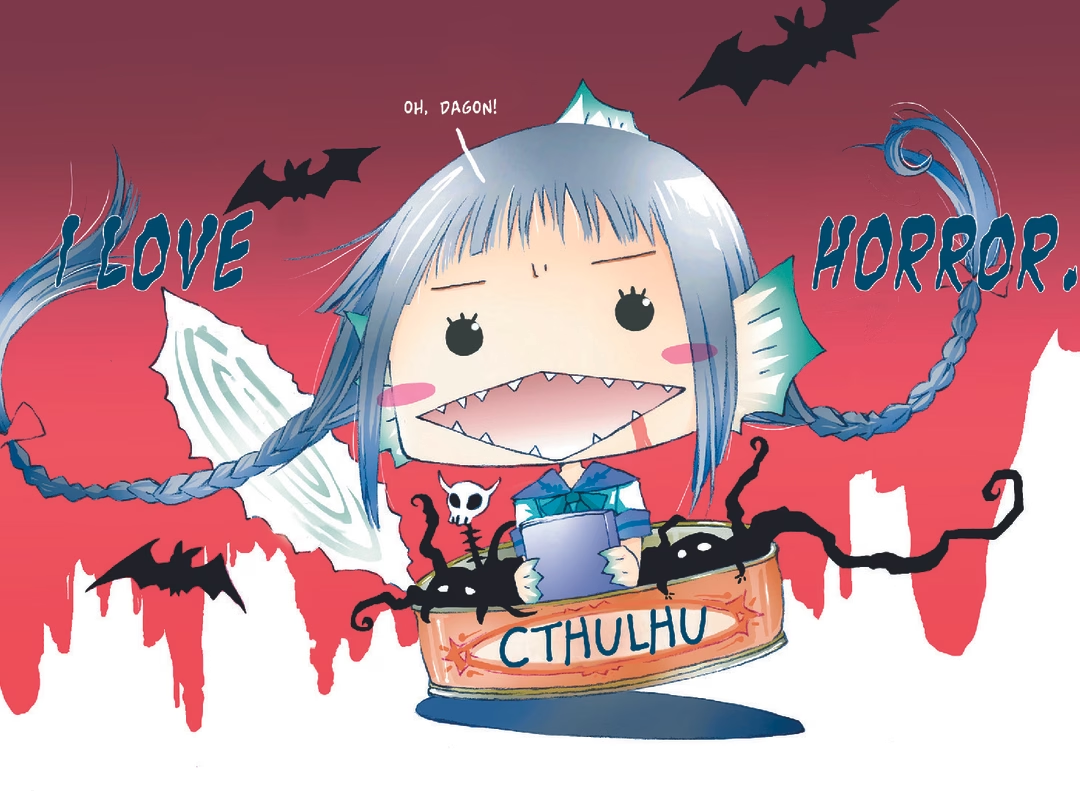

“Shadow over Innsmouth by Lovecraft has the taste of slurping up raw fish blood, y’know.”

It was after school, like always. Tohko had burst out with that proclamation out of nowhere. I was shocked, and I paused in writing the improv story.

Old books monopolized the room in the western corner of the third floor. The stacks of books had formed mounds all over, and on top of being cramped, the room was dusty.

The fold-up chair next to the window was reserved for Tohko, and today she was again sitting there reading a book. Her thin, black braids like cats’ tails hung past her hips. Her small feet, swathed in school socks, rested crassly on the chair, and she turned the pages with her white fingers. As she read, she tore small pieces from the edges of the page, then brought them to her rosy lips. She then ground them between her teeth with a rapturous expression.

“Ahhh, how delicious. This rawness that pricks the nostrils. The cool, chewy texture. Just what you’d expect from Lovecraft’s greatest work, from the master of fantasy literature, the father of the Cthulhu Mythos! The goopy tartness of blood coating my tongue—it’s too much!”

Weird.

Tohko wasn’t supposed to like scary stories.

“I am a book girl who loves all the books of this world so much that I want to devour them,” she boasted regularly, but even a president like that had weaknesses.

Although she would say that the horror and gorefest stories I deliberately wrote for her were “F-fine, really,” she ate them with a lot of sniffles. But today, Tohko seemed to be honestly reveling in the taste of stuff like rotten fish eyeballs and gooey fountains of blood.

“Howard Phillips Lovecraft was an American author born in 1890. The fantasy stories he wrote about the resurrection of Elder Gods who had dominion over the Earth in antiquity were systematized after his death into what’s come to be called the Cthulhu Mythos. Since then, scores of authors inspired by the mysterious and ghastly dark myths have published stories about Cthulhu.

“The gods in the stories resemble marine animals like octopus, squid, or fish, and they have squirmy tentacles or fins, and they’re slimy, and they stink. That’s what’s so lovely and adorable about them!”

L-lovely? I blinked, and her words took on an even greater energy.

“Shadow over Innsmouth is crawling with cute little fish monsters. It’s fantastic.

“The young man who’s the protagonist visits the port town of Innsmouth on his journey. The town is filled with a rank odor and the residents have bloated, unblinking eyes, their heads are narrow, and they’re vaguely fish-like.

“At that point, the protagonist begins investigating the fearful religion tied to the place, but an evil shadow is closing in, lapping at him like waves. Ohhh, but, but, but—okay, Innsmouth is adorable, but Dagon is so dreamy!

“As an introductory work, I recommend Call of Cthulhu. You should read the two together. It’s like surströmming and utterly yummy!”

“Isn’t surströmming supposed to be the smelliest canned food in the world? It’s got fermented herrings in it or something…”

Tohko nodded with relish.

“That’s right. The stench so reminiscent of fragrant gutters carries for dozens of yards, and the fully fermented, bulging can erupts with polluted water girded with a murderous smell.

“Until you bring it to your lips, your nose wrinkles at the intense aroma, and tears pour out of your eyes. Overcoming these challenges and tasting the slimy, salty bite of the herring with your entire tongue—that delight is no less than a happy birthday on the other side!”

“You’re talking about being dead!”

Tohko ignored my interruption and munched enthusiastically on Shadow over Innsmouth. It was no longer crinkle-crinkle, but instead crunch-crunch. She ripped the entire page out and stuffed it in her mouth.

Something was definitely off!

I took a closer look and saw that Tohko’s uniform had short sleeves.

Why, in the middle of winter? Besides, wasn’t the club supposed to be on hiatus because she was studying for exams?

“Did you write my snack, Konoha?”

Tohko turned her eyes toward me and smiled crisply. With an inexplicable chill running up my spine, I said, “Y-yeah,” and handed over the improv story I’d just finished writing. She accepted it with elation and started eating.

Today’s topics were “daisies,” “a shamisen,” and “a water taxi.” They were so different I’d struggled to tie them together, but it was hopefully the kind of sweet love story Tohko loved.

“Yuck.”

Wha—?

I gaped at being slapped down so quickly, and Tohko puffed her cheeks out, pulled her mouth into a frown, and said, “A sugary story where there’s a boy giving a shamisen performance on a water taxi and a girl gently removes a daisy from her shirt and shyly gives it to him is no good at all. It’s got to go like, lumps of flesh floating in an ocean dyed red and throwing up splashes of blood, and then Dagon appears. This is more like a fruit sandwich. It’s too refreshing, and I think it’s going to give me heartburn.”

“But—Tohko, you always tell me to write sweet stories—”

“No, what I like is red blood dripping out of raw fish!”

Tohko inched up to me without even blinking, and her face turned more squarish and grew gills, her ears turned into fins, and webs appeared on her hands.

“T-Tohko! You’re looking a lot more like a goblin now!”

“What are you saying? I’m a book girl from head to toe. Now then! Redo this, Konoha! Write me a horror story spattered with gobs of slimy blood!”

The braid-bedecked goblin’s face had become entirely that of a fish, and she opened her mouth wide and came rushing at me.

It let off a stench like raw garbage, and filthy water fell on my face. The shock of this made the insides of my nose burn, and my consciousness receded until, the next moment—

“Agghh!!”

I woke up in my own bed.

It was bright outside the curtain, the air was cool, and my sweat-covered body was shuddering.

“I-it was a dream…”

A new year was beginning today, and what an awful dream to start it with.

My shoulders slumped, and I got out of bed.

When I went down to the living room on the first floor, my little sister who was in first grade greeted me in a very adult tone.

“Happy New Year, Konoha.”

“Happy New Year, Maika.”

I patted her head, and she looked up and giggled at me happily.

“Happy New Year, Konoha. The grilled rice cake soup is ready,” my mother called from the kitchen. My father was already at the table and was in high spirits, having sips of warm sake.

“Ah, Konoha, Maika! Here’s your New Year’s money.”

“Hooorraaay, thank you!”

“Thanks, Dad.”

Everyone sat down at the table, and we ate the soup and other traditional dishes that my mother had made while we watched a New Year’s special on TV.

“Thanks, Mom.”

After I cleared my plate, I went to my room to put on a coat and then came back.

“Oh, are you going out, Konoha?” my mother asked me.

“Yeah. I promised I’d go visit a temple with someone.”

My mother’s look turned soft at that, and her lips curved in a happy smile.

“With a friend from school?”

“Er…yeah.”

The thing that had given me sudden pause was that I didn’t know if I should call her a “friend.”

My heart was suddenly fidgety, and I got flustered. Before she could ask me anything else, I hurriedly said, “Be back later,” and left the living room.

When I opened the front door, a sharp, chilly air met my face.

I sucked in a lungful of the first wind of the New Year and peeked into the mailbox.

Oh, there are New Year’s cards.

I picked up the rubber-banded bundle and flicked through them.

This one was from Akutagawa. Written with a brush and ink. Figured…As I looked at the stoic characters, I was impressed. This one was Takeda’s. Her bubble letters and cute drawings were typical Takeda.

There was a postcard from Tohko, too, written in very careful pen strokes. The penmanship and language were nothing that you would expect from someone who ordinarily clattered her chair and threw tantrums, saying, “I’m hungryyy. Write me somethiiiing.” She must have been conscious of my family’s eyes on her. This is what it means, putting up a front.

Tohko had called my house from time to time, and my mother had lauded her. “She’s such a polite girl, very on top of things.” If she found out that Tohko was actually a goblin who tore up books and ate them, might she not topple over?

Although Tohko herself would argue, “I’m not a goblin. I’m a simple book girl.”

“What the…?”

I found a strange postcard, and my hands stopped.

What was this?

There were no words at all, just a creature that looked like a bird with a bulbous body and wings stuck on it. Were the two sticks poking out of its head a beak? But they also looked like horns. The face looked like a cat, and a long tongue was lolling out of its mouth.

It was like a kid’s doodle. Had one of Maika’s classmates sent it?

It was nearly time for my meet-up, so I returned the bundle of postcards to the mailbox and walked off.

“I-Inoue…”

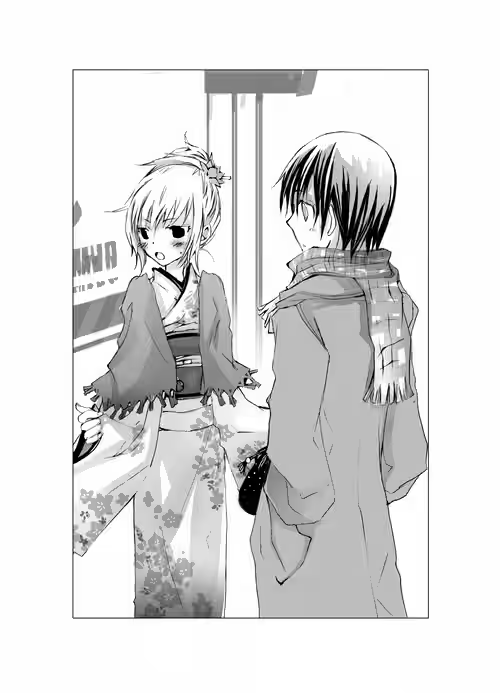

Kotobuki was waiting for me outside a convenience store near the train station, her face bright red. Her hair was tied up, and she wore a shawl over a cute flower-print kimono. Her breath came out white.

“Sorry I’m late! Were you waiting out here? I thought we agreed to meet inside.”

Kotobuki started fidgeting then and muttered, “I just wanted to feel the wind.”

“But aren’t you cold?”

She pursed her lips and answered peevishly, “N-not at all.”

“Oh? Well, let’s go, then.”

“…Okay.”

Huh? What was the matter? Her eyes dropped all of a sudden, and it was like she was disappointed.

Oh…!

I realized what it was and said, “Your kimono is cute.”

Instantly her eyes widened, and she let out a frantic voice.

“My grandmother let me wear it. For New Year’s…We do it every year. Not like this year’s anything special!”

I watched her make excuses, red faced and flapping her sleeves, and my lips curved into a smile.

I didn’t used to understand what Kotobuki was thinking very well, but now it came through just a little—that she was incredibly embarrassed or that she was happy that I’d complimented her.

I felt shy for some reason, and something warm spread through my chest.

As we headed toward the shrine side by side, I said, “I got your New Year’s text.”

She murmured, “I got yours, too.”

With a happy look, her cheeks flushed red.

Every time I saw that gentle, girlish expression so totally opposite to her usual fierce look, my heart fluttered.

We’d exchanged texts a few times since Christmas Eve. Kotobuki’s were always a little bit awkward. But the earnest effort came through, and they had appeal.

In the space of a few days, the distance between us had shrunk just a little.

The shrine was thronging with worshippers.

We got in the back of the line and after thirty minutes finally reached the collection boxes.

We each threw in our coins and clapped our hands together to begin our prayers, standing close to each other.

I prayed that nothing major would happen this year and everything would turn out fine. And as part of that, that Tohko got into college.

When I glanced beside me, Kotobuki had her eyes closed and her eyebrows scrunched tightly together, her mouth pulled into a firm line, praying with the most earnest expression I had ever seen.

It was a harsh look, as if she was angry. I wondered what on earth she was praying for. Must have been a pretty important wish.

While I was still staring at her, Kotobuki opened her eyes.

She noticed me looking at her and instantly turned red.

“Ack! Why’re you looking at me?!”

“I was done.”

“Then you should have said something.”

“You were praying so hard, I thought I shouldn’t. What were you praying for so intensely?”

“I-it’s nothing to do with you! Geez, how could you just stare at a girl’s face…?”

Kotobuki quickly went down some stairs.

She tried to move against the flow of the crowd and was about to get swept away, and her eyes bugged out.

“Ack!”

“Kotobuki—”

I grabbed Kotobuki’s hand and pulled her back.

Her hand trembled slightly in my grip, as if she was surprised.

“I mean, you have to be careful. There’s so many people.”

Kotobuki was looking up at me, her face bright red; then she lowered her gaze shyly and hesitantly squeezed my hand back.

I felt relieved and laughed.

“This way we might manage to not get separated.”

“Y-yeah.”

It was cute how she answered so quietly.

Her fingers were cold and stiff, interlocked with mine. Maybe she was nervous. To be honest, I was pretty embarrassed, too.

We walked slowly like that, following the flow of the crowd.

Her head bent in silence, Kotobuki suddenly said in an almost imperceptible, reedy voice, “Um…I need to ask you something kind of strange.”

“Okay?”

“Do you…have a mole or anything…under your right butt cheek?”

I was surprised by Kotobuki’s unexpected question and turned to look at her. Her face was much, much redder than before, and she scrambled to say something.

“I-it’s not like that! I’m really into mole reading right now and…and I wondered about you.”

“I do have a mole under my butt. But how did you know that?”

“You do?!”

Kotobuki’s face contorted as if she’d just gotten a horrible surprise. Then she scrambled again. “A-a-a-akutagawa told me about it. So you do have a mole. Huh…I see, I see.”

Her face fell further and further until it was sad and bitter.

“I wonder when Akutagawa saw my mole. Maybe during class at the pool. What does it mean if you’ve got a mole under your right butt cheek?”

“What?! Um, it’s…oh! Do you want to go pull our fortunes?”

Kotobuki pulled me over to the counter where they sold fortunes.

“You can’t come to a shrine and not get your fortune. Come on!”

“Ack—if you tug on me like that, I’m gonna fall, Kotobuki.”

I wondered what was up. This time she’d grown suddenly cheerful.

There was a part-time shrine maiden at the counter, and she shook the rectangular box for us. A long stick slid out of it, and we took the piece of white paper with the number that was written on the end of the stick.

We moved under a big plum tree and unfolded our fortunes.

“Oh—”

Kotobuki let out a sound like a shriek. I looked down at the words written on my paper and murmured, “I’ve got ‘major bad luck.’”

“What?!”

When I looked up, Kotobuki had gone pale, still holding her fortune in her hand. I peeked at it and saw it was “major bad luck,” a match to mine.

“H-how could we both get that?”

Her shoulders were trembling. There were even rueful tears forming in her eyes.

“Don’t worry about it. Look, we can tie it on that branch there and forget all about it.”

“No! Let’s get another one.”

“But, Kotobuki—”

There was no need to get that upset about it. Did girls worry about this kind of thing?

Kotobuki pouted and puffed out her chest and started back toward the counter with the fortunes.

Just then, we heard cheerful voices talking near us.

“Eeee! I’ve got ‘major good luck’!”

“Hey, me too.”

“Hooray! It’d be awful to start the year with ‘major bad luck.’”

“You know, they don’t even put those in there.”

Kotobuki glared pointedly in the direction of the carefree couple, as if their conversation had irked her.

But I thought I recognized the man’s voice.

“Ryuuuu, tie my fortune up, too!”

“You sneak. Do mine, too!”

“And mine!”

There wasn’t even only one girl! And they’d said Ryu!

Kotobuki’s eyes went wide.

On the other side of the plum tree, the man who was so charming to the three girls was Ryuto, the son of the family Tohko was staying with.

Ryuto seemed to have noticed us, too, and a friendly smile came over his handsome face.

“Hey, is that Konoha? Didn’t expect to run into you here. You on a date with Kotobuki today?”

“We’re, uh—”

I looked over at Kotobuki, who had turned her flushed face to one side.

“Er, what about you?”

“I’m on a date,” he answered coolly, without a hint of guilt.

“Yeah, Ryu’s on a date with me.”

“No, he’s not, he’s with me.”

“You’re with me—right, Ryu?”

The girls started getting into it. Sigh. He hadn’t changed a bit in the new year. Apparently Kotobuki didn’t like how Ryuto made the girls fight one another without intervening at all, and she turned a critical look toward him. Of course, that didn’t bother Ryuto; he was nonchalant. In contrast, his eyes roved all over Kotobuki and—

“I like your kimono. A beautiful girl looks good in anything.”

He laughed affably.

Kotobuki’s face showed that she was getting more and more ticked off when Chopin’s “Tristesse” abruptly started playing.

“Oh, s…sorry.”

Kotobuki was suddenly flustered. She pulled out a pink cell phone and moved off, staring at it.

Ryuto put together a serious face and whispered into my ear, “That’s from a boy.”

“What’re you talking about?”

“Oh, my experience and my intuition tell me, it’s for sure. If it were her family or a friend callin’, she wouldn’t get that flustered. She’s gonna come back and say it was her old boyfriend tryin’ to patch things up.”

“Ooo, how dramatic!”

“That kind of thing happens a lot, you know.”

“Totally.”

Even the three girls who had been arguing were nodding along like the best of friends. Looking triumphant, Ryu went so far as to say, “Tough-looking girls like that are surprisingly big cheaters. You better be careful you don’t get two-timed, Konoha.”

Was it just my imagination, or did that sound like a jab?

“You’re thinking of yourself. I’m going to tell Tohko you were three-timing first thing in the new year.”

When I said that, Ryuto looked pathetic and gazed up at the sky.

“Cut me some slack, Konoha. She’ll deck me with her bag again.”

So he wouldn’t stand up to Tohko after all.

At that point, Kotobuki pattered back over.

“Sorry. I got an urgent text. Oh, but…everything’s fine now.”

She seemed somehow intense when she said this.

“Ryuuu, we shouldn’t bother them. Let’s go.”

“I want to drink some sweet wine!”

“I want to sing karaoke!”

“Fine, fine. I’ll see you guys,” said Ryuto.

“Byyye!”

For a moment, we watched blankly as Ryuto’s group moved off energetically.

“Um…how about we get something to drink, too?”

“…Okay.”

We moved to a family restaurant.

“You changed your ring tone, huh?”

“What?”

“It’s different from the one I heard before.”

When I mentioned the hit song of a female pop star, her hands stopped picking at her dessert, and she flushed red before my very eyes.

“That’s…just for you,” she said haltingly.

“Just for me?”

“I change the ring tone depending on who it is…for friends or for family or whatever.” After pouting and looking up at me aggressively through her eyelashes, her eyes suddenly went timid again. “I only use that song for you.”

“O-oh.”

Uh-oh—my face was burning, too.

I was pretty sure it was a graceful, sickly sweet love song with a chorus of “I love you, I love you” in the pop star’s cute voice.

“Do you split up your ring tones, Inoue?”

“No, everyone’s got the same one.”

“Oh.” Kotobuki bit down on her lip.

There was something touching about this, and I smiled.

“But I want to try changing it. Then I’d know who was calling right away, which would be convenient. What song would be good for you? Any requests?”

Kotobuki leaned forward.

“The theme from Beauty and the Beast.”

She said it impulsively, then pulled back in embarrassment and stuck her spoon into her dessert and clinked it against the dish a few times.

“Um…when I was little, I saw the Disney movie, and I was totally hooked on it. The tune is pretty, but the lyrics are really good. I love the Japanese version so much. When I was picking the ring tone for you, I didn’t know what to use. So…”

“Got it. Beauty and the Beast. I’ll use that for your ring tone, then.”

I pulled out my cell phone, flipped it open, and started connecting to a ring tone site when Kotobuki stopped me in a panic.

“No, stupid, don’t look for it here! Don’t listen to it!”

“Why not?”

“No, no way, no!…Ch-change it at home, secretly.”

Seriously intimidated by her firmly pursed lips, I almost burst out laughing.

Kotobuki ate her dessert with a glower.

Still smiling, I said, “Hey, do you want to go see a movie next week?”

“Really?” Her head popped up.

“Sure. What do you want to see? Is there some Disney thing playing?”

“What about you? What kinds of movies do you usually watch?”

“Hmm…”

Deep in my chest, something tickled. But it felt good.

Talking with Kotobuki about our interests, deciding on a movie title, deciding a time and place to meet.

The unassuming, embarrassing, ticklish conversation drew on until I forgot the time.

“Um…I’m going to do my best! So…I look forward to the year with you!”

Going our separate ways. At the crossroads that had begun to darken into calm, Kotobuki looked up at me with bright red cheeks and said that, breathing excitedly, and then ducked her head.

“Me, too. I had a lot of fun today,” I answered with a smile, and a smile slowly spread over Kotobuki’s face, too, like the gentle light of evening.

“I…I’m looking forward to the movie. I’ll text you, too. B-bye,” she whispered shyly; then she hurried away, the sleeves of her kimono fluttering. I watched her go, feeling content.

When I got back home, my portion of the New Year’s postcards were sitting on my desk.

“Huh? This card…”

It was the one I’d seen on my way out that looked like a monstrous version of a bird and cat. I thought maybe one of Maika’s cards had gotten mixed in with mine and checked the address, where childishly unsteady letters read, “Konoha Inoue.”

It was for me?

But there was no name saying who had sent the card anywhere on it.

Maybe it was a prank…

I set the postcard down without thinking too deeply about it.

I sat down in my chair, opened my cell phone, and searched for a Beauty and the Beast ring tone. I downloaded a music box version.

Ah, this song…

The duet between Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson. I’d heard it in commercials before. It was a tranquil, gentle song. I looked up the lyrics for the Japanese version while I was at it.

A wondrous tale of love

Hand in hand, a hesitant caress

Only just a bit, step-by-step it comes

A kind act opens the doors to love

It looked like the song had been rearranged a little when it was translated.

I remembered the chilly, awkward sensation when I’d held hands with Kotobuki in the crowd, and it squeezed my heart sweetly tight.

There was definitely no burning passion in my feelings, but…hesitant, step by step.

Maybe we were getting closer.

I bought and downloaded the English version that Celine Dion had sung, and I listened to it over and over on my headphones that night.

As I closed my eyes, I saw in my mind the happy smile, again and again—gentle like the last light of the setting sun—that Kotobuki had given me when we parted.

It was the day before we were supposed to go to the movie that I got a text saying she couldn’t make it.

I’m sorry. I can’t go tomorrow. I might not be able to call or text you for a while.

She didn’t give a reason.

There was no response to the text I sent her, either.

I didn’t know why she’d suddenly canceled our plans.

After two days went by with a nebulous anxiety growing in my chest, I got a call from our underclassman Takeda on my cell phone.

“Oh, Konoha! It’s bad! Nanase got hurt, and she’s in the hospital. They say she fell down the stairs!”

* * *

You’re really dangerous and arrogant and selfish, and I hate you and detest you.

How could you act so cruelly and hurt me like that?

You watched, laughing, as my heart was slashed to ribbons by a glinting, transparent blade, and I screamed and spilled stinking blood and writhed in pain. You stomped casually on my back as I beat my fists against the ground and wept.

What did you and Haraguchi talk about? Where did you go with Mine? Did you think I didn’t know?

And how you misled Haraguchi with your skillful words and how you let Mine touch you and how you played together in the water—I know about all of it. I saw it with my own eyes.

Then my body was thrown into blue flames, and I experienced pain as if I were being prodded all over by burning metal skewers until I was bloody.

You always, always saw me suffering and laughed in pleasure.

Then you would cuddle up next to me, steal all sorts of things from me, and destroy me.

So you’ll forgive me if I take my revenge on you, right?

“Whaaaat? A visit? You have to do it. That goes without saying.”

On the other end of the cell phone, Takeda shouted, aghast.

“But when I texted Kotobuki, she said not to come.”

I was terribly confused.

I’d been surprised that Kotobuki had canceled the movie and been admitted to the hospital the day before we were supposed to go, and I didn’t know how to take the fact that when her reply finally came, it was incredibly brusque, or that she’d told me that she was embarrassed so I didn’t have to come visit her.

She explained that the reason she’d kept quiet about being hospitalized was that she had been admitted to the hospital she’d been in over the summer again and had felt stupid.

It wasn’t that I didn’t understand why she would feel that way, but…

When I went to visit her with Tohko over the summer, she’d had a litany of mutterings and been in a bad mood, and when she was alone with me in her hospital room, she had turned away from me as if I was a nuisance.

Knowing Kotobuki’s personality, I guessed she didn’t want to show her weakness. Maybe she really didn’t want me to come. If I showed up even though she’d told me not to come, wouldn’t that make her feel bad?

After much angst, I asked Takeda’s advice through a text message, and the call had come immediately to lecture me. “You’re so clueless about how girls feel.

“With girls like that, even if they talk tough, deep inside of course they want you to come. Geez, you are just a lost cause. Things finally started getting good, and now her boyfriend won’t go visit her in the hospital. That’s the worst. Nanase is gonna cryyy.”

She spoke her mind in a cute voice like a cartoon character.

“Maybe that’s it…”

“That is it,” she declared crisply, and I decided to go visit Kotobuki.

The next day, I got the people at a flower shop to make a small bouquet from pink roses and red strawberry-scented candles shaped like strawberries and brought that to the hospital.

“Let’s see…Kotobuki’s room is…”

I’d been in this spacious hallway that smelled of medicine before. I was walking down the hall confirming the room number when it happened.

“Inoue.”

Someone spoke my name, and I looked up. Akutagawa was standing there in a black knit shirt and jeans wearing a hard expression.

“You come to see Kotobuki?”

“Huh? You knew she was in the hospital?”

A shadow fell over Akutagawa’s eyes, and his handsome face twisted ever so slightly.

“Yeah…she told me a second ago.”

Akutagawa’s mother had been lying unconscious in a hospital bed for years now.

So it wasn’t strange for him to be at the hospital. He must have come to visit his mother.

“Did you go see her?”

“Yeah,” he answered ambiguously.

I wondered what was going on. Why was he so on edge?

“How bad is she hurt? It’s not serious, is it?”

“She’s fine. She’ll be out soon apparently.”

“That’s good. But I heard she fell down some stairs. I wonder where. At a station, you think? Did she tell you anything?”

“…No.”

Akutagawa turned his eyes away in apparent pain and fell silent.

Then he slowly opened his mouth and said, “Kotobuki’s room is over there. She looked pretty tired, so you probably shouldn’t stay too long.”

“Gotcha. Thanks.”

I thanked him and walked off. As I did, I felt someone’s eyes on me. When I turned around, Akutagawa was still standing in the hallway, looking at me with a tense expression.

Was he worried about me, maybe? I wasn’t a kid, though; I could handle finding a hospital room on my own.

“Ah, here it is.”

I stopped outside the number I’d written down on a piece of paper. There was a placard with the name KOTOBUKI on it, too.

I could hear voices talking inside.

Was it the person sharing the room with her?

I knocked on the door and opened it slowly. Two of the four beds in the room were occupied, and a high school–aged girl and a petite old woman looked at me.

“Excuse me. I came to see Nanase Kotobuki.”

“Nanase’s not here right now,” the girl answered with a cheerful look.

The old woman spoke next. “She ought to be back from her tests soon, though.”

“I see.”

They both suggested that I wait there, but I was embarrassed and went out into the hall.

While I was spacing out there, an unexpected person appeared.

“Konoha?”

“Tohko!”

Wrapped up in a navy-blue duffle coat and wearing her school uniform even though it was winter break, the book girl with the long braids saw the pink bouquet in my hand, and a smile spilled across her face.

“Did you come to visit Nanase, too?”

“I did, but is it okay that you’re not studying for your tests? Your National Center Test is right around the corner. You’re not still solving second-year math problems, I hope?”

Tohko huffed.

“I’m doing the third-year problems, just like I should be. Whether I’m solving them or not is a different story.”

“If it’s a different story, it’s a scary one, don’t you think?”

“Geez, I just heard from Chia that Nanase was in the hospital again, and I was so worried I ran over. Please don’t bug me about all this tedious stuff. It’ll make Nanase’s injuries get worse.”

“I don’t think there’s even the most remote link between your tests and the state of Kotobuki’s injuries. Besides, she’s not in the room right now.”

“Oh no, really?”

Tohko’s large, dark eyes widened, and her eyelashes fluttered. Then she giggled.

“Then I’ll wait here, too,” she murmured and lightly leaned her thin shoulders against the wall. “Oh, I got your New Year’s card on New Year’s Day,” she added.

“Who was the one who insisted so loudly that I do it?”

“But if I can’t eat your snacks, that’s no way to begin the new year.”

“It was a real pain to write an improv story on a single postcard, you know.”

“Thank you. It was very good. It was light and cool, like biting into a frozen rice cake stuffed with ice cream.”

Tohko closed her eyes and let out a sweet sigh.

Something deep inside my chest always felt ticklish when she complimented me so directly, and I felt restless. That was why I accidentally wrote nothing but weird stories that made Tohko shriek “Ewww, this is awwwful.” But since Tohko was studying for her exams, if I made her eat something strange and the worst were to happen, it would be bad.

The hallway, smelling like medicine, was so quiet it seemed like I could hear even the sound of her breathing, and I got the odd sensation that Tohko and I were the only two people inside the big white building.

“Where are you taking exams for?”

I’d heard that she was recklessly taking tests for only national schools, but I didn’t know where her first-choice school was. I wondered if it was in town or nearby.

Or maybe…

“Um, Tokyo University and—”

“Tokyo University?!”

I ended up shouting, I was so surprised. Then I remembered that I was in a hospital and quickly lowered my voice.

“You’re joking, right? What country is this Tokyo University in where someone with a score of zero or three or whatever in math can apply?”

Tohko brushed it off. “Don’t be mean, Konoha. When I say Tokyo University, I mean Tokyo University. The hallowed institute where Ogai and Sōseki and Dazai and Akutagawa spent their youth. Japan’s most illustrious academic institution with the Red Gate, Sanshiro Pond, Yasuda Auditorium, and the ginkgo trees.”

“Did you mistake college for a place you go sightseeing? Are you serious about applying there?”

“Yes, I am. Every student studying for exams should attempt Tokyo University at least once. It’s different for the top candidates, obviously. But when you spend another year studying to get into college, it sounds so much better to say ‘I failed the exam for Tokyo University,’ don’t you think?”

“What are you doing thinking about what’s going to sound best when you’ve failed?”

I wanted to hold my head in my hands. Argh, this girl was going to fail. She’d decided to spend another year studying. I wanted back my fifty yen that I’d thrown into the collection box.

“You should go home, Tohko. It might be useless at this point, but you ought to study.”

“What? But Nanase—”

“Why not visit her some other time? I’m going home, too, so please go home and solve some math problems.”

Almost an hour had gone by already. Maybe her test was running long.

I could hear a bell outside the building announcing it was three o’clock. It was the automaton clock set up outside the station.

Tohko sighed.

“…Okay. It’s a shame, but let’s at least leave the flowers.”

We went back to Kotobuki’s room, arranged Tohko’s flowers and mine together in a vase, left a note for Kotobuki, and then left the hospital.

“Konoha, are you going out with Nanase?” Tohko asked as we walked beneath the leaden sky that threatened sleet.

Her tone was offhanded, as if she was discussing something not at all out of the ordinary.

But I felt a sense of guilt scraping deep in my chest and muttered only, “…Well, you know.”

I supposed the reason I couldn’t fully look Tohko in the eye was because I was embarrassed.

Or was there another reason?

I advanced without breaking my gaze, and in a kind voice like an older sister’s, Tohko said, “Okay. Don’t be like Ryuto and cheat on her.”

My heart spasmed again. In a gruff tone, I muttered, “Even if I wanted to act like Ryuto, I couldn’t do it.”

I started telling her about how I’d run into Ryuto with some girls at the shrine during our visit on New Year’s in order to change the subject, and Tohko glowered staunchly.

“Honestly, that kid…he’ll do anything.”

Apparently she was worried, as an older sister, about a kid brother who loved women and excelled at violent scenes. She muttered discontentedly.

Maybe in Tohko’s eyes, I was the same as Ryuto—a little brother she had to look after.

For some reason, I felt melancholic.

We reached the road where we would part ways without another word.

When we got there, Tohko’s look again became gentle and enveloping, and she asked, “Are you going to go visit Nanase again tomorrow?”

“I’m planning to, yes.”

“I can’t go tomorrow, but tell Nanase to take it easy with her physical therapy for me, okay?”

“Okay, I’ll tell her.”

At my answer, Tohko turned a smile as clear as water on me, and then left.

As I walked along the edge of a road busy with cars, I thought things over.

I’d started to care for Kotobuki.

I hoped that the distance between us would keep shrinking.

And when her tests were over and the gloomy winter passed and summer came, Tohko would graduate. In contrast, the distance between Tohko and me would probably get bigger when that happened.

It felt as if the sky had grown even darker and heavier.

I wonder what schools Tohko’s gonna take exams for? I thought.

As I speculated on whether there were any national schools that Tohko could get into close enough to get to by train, I went into a convenience store.

As I was passing the magazine rack, my eyes locked onto the headline of a weekly magazine.

A jolt went through me.

The thing that caused my knees to buckle where I stood was the fact that I’d seen the name Miu Inoue.

The magazine ran nothing but bogus articles and was one I often saw in ads on the train. Any other time, I would have looked right past it.

I would have again if I hadn’t once been that very Miu Inoue, a beautiful, young girl who was called a mysterious genius of an author.

Did Miu Inoue Commit Suicide?!

My throat grew tight, as if I was being strangled by a burly hand, and my fingertips grew cold.

I forced down a hard lump in my throat, and with a trembling hand, I picked up the magazine reporting on my death and headed toward the register.

As soon as the door to my room closed, I forgot to even turn on my heater and lost myself in reading the article, still wearing my jacket.

Miu Inoue was, at fourteen, the youngest to win a literary magazine’s new author prize in its history, and her work became a massive best seller—why had she disappeared? She was called a mysterious genius, a coddled beauty—why hadn’t she written a sequel?

In fact, the article said, right after Miu’s award-winning story was published, she committed suicide by jumping off the roof of the middle school she was attending at the time.

Miu’s true identity was that of an ordinary girl attending a middle school in the city. The article told how, isolated from her classmates, she constantly wrote the stories that were her hobby alone during breaks.

The article featured testimony from classmates: “After Miu Inoue’s book won that prize, we all talked about how she was probably X. I mean, their names were the same, and when we read the story that won that award, there were descriptions that really seemed to be using our school as a model.”

Also, the testimony said she had begun to act strangely right after receiving the award. “She’d always been stuck-up and acted like she didn’t want to be friends with the likes of us, but around that time, she was especially irritable and went home early a lot. We thought maybe she was busy writing a sequel, but…her skin started to look awful, her eyes were all red, and she looked like she might be sick.”

And then, her classmates even touched on this: “We showed Miu’s book to X and asked her, ‘Did you write this?’ And she glared at us with this awful look, then grabbed the book and threw it onto the floor. Then she stomped on it and yelled, ‘None of your business!’ It was after that that X jumped off the roof.”

X survived, but she transferred schools, and no one knew where she had gone.

Miu Inoue, the brief spark of genius that appeared like a comet in the literary world, would most likely never surface again. The moment X threw herself off the roof, she’d killed the author Miu Inoue.

That was how the article concluded.

I crumpled the pages in my fist and tore them out.

I focused intently on ripping them apart with my frozen hands, which had lost all feeling. My heart was twisted up, and my head hurt so much it felt like it was splitting in two.

I didn’t know if the testimony of the classmates was real or a fabrication of the author’s. But what they’d written about on these pages was not Miu Inoue—not me!

This was my Miu!

Why did the tabloid have to mistake Miu for me and write such an awful article about her?

Miu wasn’t Miu Inoue.

That was me.

The backs of my eyes turned bright red with rage, and my throat felt like it was burning. This—this article was horrible! This evil article—that dragged people’s names through the mud out of idle curiosity!

Ah, but— Kotobuki had said it as well. “That girl you were always with in middle school was Miu Inoue, wasn’t she?”

Miu was always writing stories on loose-leaf paper and talked about applying for a new author prize, and her name was “Miu.” When Miu Inoue won, Kotobuki had thought Miu had won.

It wouldn’t be unusual if our other classmates thought the same thing. In fact, it was more natural than thinking that I was Miu Inoue, when I had been nothing more than an unassuming middle school student who was glued to Miu and only listened to the stories she told.

When I thought that, a shudder ran down my spine and I felt dizzy.

At the time I received the award, I’d been baffled since I’d had no intention of winning. Plus, Miu was ignoring me, and I didn’t know what I should do, so I had my hands full with my own problems and hadn’t realized that our classmates were spreading rumors like that about her.

How could they have believed that Miu was actually Miu Inoue?!

Miu had known about that, too! When the article said she’d thrown Miu Inoue’s book onto the floor and stomped on it, that cut into my heart.

How must Miu have felt, hearing our classmates gossiping? What went through her mind as she weathered the gazes, filled with curiosity and envy, that were turned on her?

But I’d been sure Miu would be chosen for the grand prize and become an author, not me! It was her dream! She only whispered it to me!

I had told her, “I know you’ll win the grand prize. I support you!”

I tore and I tore, but the evil words latched onto my brain and wouldn’t go away. I cut my hand on the edge of a piece of paper and blood welled up, stinging. Even so, I went on tearing madly.

“Nngh—”

Nausea welled up in my throat, my brain was on fire, and I knelt amid the shreds of the article, digging my fingers into the clothes covering my chest, practically beating them against my body.

My throat convulsed, and I couldn’t breathe—!

I writhed on the floor, dragging my face against the carpet, and a moan escaped my lips. The sweat exploding from me robbed the warmth from my body.

I had been trying not to think about it this whole time.

But the reason Miu had jumped off the roof was because I, her most important reader, had taken the prize instead of her.

Because I had stolen Miu’s dream from her!

No—no! That wasn’t true! I hadn’t written a novel and applied to the same contest as Miu in order to usurp her prize!

The pain in my heart—it felt as if it was being carved out by blades—drove me into unconsciousness.

I couldn’t get the pain under control no matter how much I dug my nails into the carpet and moaned. Cold hands twisted my heart into a rope.

Help me. Forgive me, Miu!! Miu!!

* * *

I’ll take everything from you. I wonder when I first had that thought.

When we were in elementary school, I went to your house to play a lot, remember?

There were sky-blue curtains hanging in your room with pictures of clouds printed on them, and you had a grass-green carpet with all kinds of pillows shaped like animals laying on it.

“My mom made too many,” you said and laughed as you hugged a zebra pillow to your chest.

I think I remember a golden birdcage was set in front of your bay window and the snow-white bird in it would chirrup cutely.

Whenever you brought your face close to the cage, the bird came closer, too. When you laughed at it, the bird would flap its wings happily, too. You would open the cage, put the bird on your finger, and kiss it on the beak or sing with it.

We would lie on the grass-green carpet and do our homework or look at picture books or talk about outer space.

Sometimes the door would open, and your mother would bring in sweet milk tea or pancakes on a tray.

Then, with a smile like honey, she would kindly say, “Wash your hands, and then you can eat.”

When school ended, I went to your house every single day, remember? Every single day.

But really, I didn’t want to go there.

Your house was like a pretty birdcage. I felt as if my wings had been clipped and I was locked up like that little white bird. It was gut-wrenching.

When I came to the front door of your house, I always hardened the pit of my stomach and stopped breathing so I wouldn’t inhale the sugary air that smelled like candy.

If I hadn’t dreaded going back to my house, I never would have gone to such an awful place willingly.

And I’m positive that bird only pretended to like you in order to get food.

So when it pecked at your lips with its beak, I would think, my brain burning like fire, It probably despises you for stealing its freedom. Bite her lip; peck out her eyes! Rip off her nose to teach her a lesson.

Your mother was a spiteful pig, too.

Whenever I came over, she would give me a slimy, snakelike look from behind her smile. Blue flames would roar up in her eyes. She would stare at me, and there was murder in her gaze.

She pretended to bring us snacks in order to watch me covertly. When I went downstairs to use the bathroom, she would come out of the kitchen and follow me every single time.

A tiny baby that looked like you came at me, dribbling and crawling, so I tried to be nice to it. She descended with a demonic look on her face and picked the baby up and took it away from me.

Your mother never gave up her cruel tricks, all of them like needles dipped in poison that peck at the skin. She continued giving me bitter candy wrapped up in a blanket of sweet sugar.

When she told me she didn’t want me coming over so much, I considered slicing her throat with the scissors I had in my hands.

I hated your house.

I hated your family so much it made me sick.

But you—I hated you most of all.

* * *

When I woke up the next morning, I felt a chill.

My head hurt, too. Maybe I’d caught a cold.

My eyes fell to the carpet.

The remains of the article were no longer scattered around. Yesterday, I had forced myself to crawl around and pick the pieces up, put them in a paper bag, and then put that into a plastic bag with the other trash to carry it out to the curb in the middle of the night so my mother wouldn’t find it.

Why did Miu Inoue choose death?

Even now that I was awake, those words were seared into the back of my mind like a brand, stinging and painful.

That Miu had jumped because of me.

I bit down on my lip, lifted my heavy body, and managed to get changed.

When I went to the living room on the first floor, breakfast was laid out.

“Good morning, Konoha. Oh, are you going out again today?”

“Yeah…I’m going shopping; then I’m going to the hospital to visit a classmate.”

“Didn’t you do that yesterday, too?”

“I didn’t get to see her yesterday.”

As I talked with my mother, I thought about other things.

I forced myself to swallow the broccoli soup and smoked-salmon sandwich that I couldn’t taste while my mind was filled with the article I’d read yesterday.

I’d hurt Miu, hadn’t I?

And Miu had hated me, hadn’t she?

These questions that offered no answers dug into my heart.

Should I really go see Kotobuki when I was like this? Would I be able to act normally in front of her?

“I’ll be back later.”

I finished my meal and sluggishly stood up.

It was after three in the afternoon when I reached the train station outside the hospital. The reason it had taken me so long was that I had, in fact, been conflicted about going the whole time.

I moved forward with a heavy heart as I listened to the clock’s bell.

It wasn’t good to visit Kotobuki while I was thinking about Miu.

But classes were starting tomorrow for the third term, and I might not be able to come to the hospital very much after that…I had to see her today.

Dragging my body, which couldn’t keep out the cold, I went past the reception area.

I tried going by Kotobuki’s room, but her bed was empty again today.

Speaking of which…I’d left flowers and a note for her yesterday, but Kotobuki hadn’t sent me a text or called. Maybe it really did bother her that I’d come to visit.

That was a convenient explanation. But if Kotobuki didn’t want to see me, then it was better that I didn’t.

I decided not to wait for her and just go home, and I left the room.

My chills and headache were getting worse, and something hazy was spreading through my chest. I was walking down the hall feeling guilty when it happened.

A girl screamed from around the corner ahead.

“Don’t go near Inoue!”

That voice—

My heart gave a little leap.

Wasn’t that Kotobuki?

“You are absolutely awful!”

Who in the world was she talking to? Her voice was so harsh, and she sounded angry.

I walked quickly in the direction the voice was coming from and turned the corner.

“An evil girl like you has no right to see him!!” Kotobuki shouted with burning eyes, a large bandage stuck on her face. She was supporting herself on an aluminum cane fixed with a ring around her right arm.

She wore a sweater over her pajamas.

Standing in front of her, her back to me, was a girl with two aluminum crutches under her arms. She was also dressed in pajamas.

Her body was slim like a boy’s.

Her hair was short like a boy’s.

Kotobuki gasped and looked at me.

Her bandaged face tensed visibly, and she paled. Disappointment and terror shot like arrows through her widened eyes.

I came to a halt, caught off guard by her expression, and the girl on crutches turned around.

Every sound in the world fell away, and I felt as if time had stopped.

A pale cheek.

Big eyes.

Cherry-pink lips.

I knew this girl who looked like a boy, who was at this moment reflected in my eyes. I knew her voice. I knew her smile. I knew the way she moved, the smoothness of her hand, the softness of her lips on my earlobe, the sweetness of her sighs.

“Konoha. Konoha.”

Her innocent voice calling to me. Sweet memories tightening my chest. A white angel smiling in a sacred place!

“Konoha, do you like me? Look me in the eye and say it.”

“Do you like me? Hmm? I love you. How much do you like me, Konoha?”

A lovely voice like a bell made of glass called my name exactly the way she used to.

“Konoha.”

Miu looked at me joyously, her eyes sparkling.

Her lips curved into a gentle, indulgent smile.

“You finally came to see me, huh, Konoha?”

Her face filled with a radiantly happy smile, and Miu stretched out her hands and tried to run toward me.

Her aluminum crutches clattered loudly to the floor, and her body tilted forward.

“Miu!!”

I exploded toward Miu.

The instant her delicate, pajama-clad body had crumpled to the floor, the image of Miu jumping off the roof came to my mind, and I thought my heart would stop. I cradled her in my arms deliriously.

“Miu! Are you all right?! Miu?!”

Miu circled her arms around my neck and embraced me, trusting her whole body to me.

“I can’t walk without my crutches. I forgot. Because I got to see you again, Konoha. Konoha, Konoha, I’ve missed you. I’ve missed you a lot. I’ve…been waiting for you.”

Her voice was raspy, her emotions in turmoil from her unrestrained happiness.

Miu’s breath touching my ear. The warmth of Miu’s body against my skin. The bittersweet smell of soap mixed with sweat.

My mind was reeling, and I hugged Miu back fiercely.

This wasn’t a dream.

She’d lost a lot of weight and her hair was short now, but her clear eyes were unchanged. This was definitely Miu. Miu was here.

Still clinging to me, Miu whispered in an emotional voice, “Kotobuki was saying terrible things to me. She said she would never let me see you, that I didn’t deserve to see you…”

When I heard that, I finally remembered Kotobuki’s presence and that we were in a hallway at the hospital.

Hey! Why were Kotobuki and Miu together?

And how could Kotobuki have said those things to Miu?

When I lifted my gaze, Kotobuki was looking down at us with a tense expression, her forehead tightly knit, showing that she was fighting back tears.

When her eyes met mine, her face flushed red, and she started trying to say something in a high-pitched voice.

“N-no…I was…”

Miu buried her face against my chest and started crying, interrupting Kotobuki’s explanation.

“You heard her yelling at me a second ago, didn’t you, Konoha? She really did say a bunch of awful stuff to me! Like how I deserved to spend the rest of my life in the hospital and how she couldn’t stand to look at me and that I shouldn’t go near you. Sh-she came to my room out of nowhere and said, ‘Inoue’s forgotten all about you. Serves you right.’ I-I couldn’t say anything. It hurt so much.”

“That’s not what happened!”

Kotobuki’s eyebrows shot up, and she clenched her fingers around her cane. Her pale lips were trembling slightly.

“Eek! She’s glaring at me. Take me back to my room, Konoha. I’m scared. Hurry.”

Miu seemed badly confused. She curled up in my arms like a baby bird and sobbed, her body shaking.

“I’m sorry, Kotobuki.”

The instant I said it, Kotobuki’s eyes went wide in shock.

But I was confused, too, by my sudden reunion with Miu, and I couldn’t think things through properly.

At Miu’s request, I put my arms around her body—it was as light as air—and helped her stand, then picked up her crutches. Then, supporting Miu, I walked away.

Kotobuki watched me do it without a word, biting down fiercely on her lip and gripping the cane affixed to her arm so tightly that her fingers turned white.

Clang, clang…I moved down the hall with Miu, who nimbly handled the crutches to walk.

The distance between Kotobuki and us grew steadily greater.

“I really have missed you, Konoha. This whole time, I’ve wanted to see you. I’ve been waiting,” Miu repeated in a voice like a whisper. “I’m sure you’re mad at me. For doing what I did, right in front of you.”

It was as if she’d grabbed my heart in her bare hands.

The image of Miu falling away backward came to my mind, and my throat quivered, making it hard to breathe.

“I’m not…at all.”

Still on her crutches, Miu lowered her eyelashes and murmured forlornly.

“No…of course you’d be mad. When you came to see me at the hospital, I wanted to see you more than anything. But my mom and dad…they wouldn’t let me see you.

“Since I was with you when it happened, they thought you must have done something to me. And then they forced me to change hospitals…I’m sorry, Konoha. I wrote you letters, too. But I never once got a reply from you.”

Surprised, I said, “I never got any letters!”

Miu’s face grew even sadder at that.

“I thought as much. Your mom…she hated me. I thought she might not give them to you.”

My heart felt chilled.

“You’re saying my mother threw the letters away?”

Miu stopped walking and squeezed my arm with one hand.

“I dunno…But the fact that the letters didn’t reach you might imply that. But I’m sure she’d say she doesn’t know anything about it.”

I couldn’t believe that my mother would throw out Miu’s letters without telling me. But it was true that she’d seemed concerned that I only ever played with Miu.

“Miu is a little girl. You’re a little boy. So don’t you think you should play with other little boys?”

She’d said that to me before in a gentle voice.

As we advanced in school, Miu stopped coming over, and we started meeting up at the library in school or at a nearby library.

I didn’t think my mother would throw away letters addressed to me.

But if not, then where did the letters from Miu go?

I’d been afraid this whole time that Miu hated me.

She was entrusting her body to me like this, talking to me just like she used to, and my heart trembled with an almost melancholy joy alongside the anxiety, confusion, and doubt that it also felt.

Miu pressed her head against my chest. As I gently supported her, we started walking again.

“When did you come back here?” I asked.

“…Last winter.”

“That long ago!”

“I’ve been waiting for you to come, Konoha. Kazushi promised he would give my letters to you and bring you with him. But…”

“Kazushi…who’s that?”

Miu stopped outside the room with the name card reading ASAKURA and looked up at me, her eyes narrowing quickly.

Then she hung her head in silence. Her bangs slid across her eyes and hid her expression.

The next moment, the name Miu produced gave me a shock.

“Your classmate, Kazushi Akutagawa.”

“Asakura? You’re back.”

I was flabbergasted to see the door in front of us open and Akutagawa come out.

It was like being punched in the head just for walking past someone.

I couldn’t believe what my eyes were showing me.

Akutagawa looked at me, too, and his face instantly stiffened.

“…Inoue.” His muffled voice slipped past dry lips.

Akutagawa looked at Miu standing beside me, then looked back at me, and his brows knit in pain.

What are you doing here?!

A hot lump rose in my throat.

Miu suddenly threw her head back and shouted at Akutagawa, “How could you, Kazushi?! You said you would help me see Konoha. I believed you! I trusted my letters to you. But you didn’t give them to him, did you?”

“Calm down, Asakura!”

Akutagawa rested a hand on Miu’s shoulder and tried to soothe her. That act struck me as very familiar, and a searing pain coursed through my chest.

Miu threw off Akutagawa’s arm with an expression of naked loathing. Losing her balance, her body wheeled and fell back against me. She clung to me tightly.

“Don’t touch me! You said Konoha resented me. I believed you, ’cos you’re Konoha’s best friend. You told Kotobuki about me and let her bully me—how could you do such terrible things?”

“Cut it out, Asakura. Don’t say another word. Please, stop it!” Akutagawa shouted, his face twisted and his breathing feeble. His narrowly squinted eyes were colored by suffering.

“I hate you. Get out! Don’t ever come here again. Don’t interfere with me and Konoha!”

Akutagawa looked over at me. His lips started moving as if there was something he wanted to say, but Miu said, “Go away, now!!” and he pressed his lips firmly together. Looking once more at me with painfully sad eyes, he let out a heavy sigh, quietly turned his back, and left.

Miu buried her face against my chest, as if she didn’t want to see him.

Maybe I should have gone after Akutagawa.

Maybe I should have stopped him and asked what was going on.

But so many different things were happening at once, I didn’t know what I ought to do.

Feeling as if my chest were being ripped open, I listened to his retreating footsteps.

At last they became totally inaudible and the hallway felt eerily silent.

“Let’s go inside, Konoha. Come with me.”

I could no longer think, so I went with Miu just like she told me to.

Miu seemed to have the room to herself; there was only one bed.

I sat Miu down gently, as if she were an expensive, breakable doll, atop the starched white sheets.

Miu put her arms around me and rubbed her cheek softly against my neck like a lonely kitten.

Then she turned her face up to mine, narrowed her eyes sweetly, and whispered in relief, “I’m glad I got to see you, Konoha.”

Dinner was long over when I returned home.

“Sorry. I ate while I was out.”

“You should have called, then.”

“Sorry…”

Really I hadn’t eaten anything, though.

“Mom?”

“Yes?”

My mother turned around with a smile.

“What’s the matter, Konoha?”

I moved my mouth laboriously.

“Do you remember Miu?”

My mother’s face tensed suddenly.

“Y-yes…”

As I felt the air prickle against my skin, I forced the words out with a fierce effort.

“You haven’t ever…hidden anything from me about Miu, right?”

I saw my mother’s eyes widen in shock and her lips tremble in fear.

“What are you saying, Konoha? Of course I haven’t. Why are you asking all of a sudden? Have you had some news from Miu?”

“No, I was just…thinking about her,” I lied to my mother, who asked her questions uneasily and pale faced.

“I see…You ought to just forget about her.”

“I guess.”

It was hard to breathe, and it felt like my heart was ripping apart. It seemed like my mother was reacting way more than necessary to what I’d said. After Miu’s accident, I’d withdrawn and not gone to school for a long time, so she might have just become oversensitive.

But…

Maybe I was just overthinking things when I thought I saw guilt appear in her averted eyes.

“Konoha, let’s play a video game!”

My little sister came over innocently.

“Maybe another time.”

I pretended I was busy with homework and fled to my room.

The sweet melody of a music box startled me, and I looked over at my cell phone. I’d gotten a text from Kotobuki.

I remembered that I’d left her standing in the hall at the hospital, and my heart and throat instantly squeezed tight.

Holding my breath, I opened the message, and the words “I’m sorry” leaped out at me first thing.

I’m sorry…for not saying anything about Asakura.

I heard about her from you and wanted to meet her real badly.

When I talked to you, I thought it hurt you to remember her…so I couldn’t tell you that she was at the hospital.

I’m so sorry.

But she was the one who contacted me first.

If I tell you this, you might think I’m a bad person, but…

Don’t believe her.

I’m worried about you. Asakura isn’t the girl you think she is.

My heart swelled, and my throat quivered.

I was the one who should have been apologizing.

I’d left with Miu and hadn’t listened to what Kotobuki had to say after Miu made her out to be the bad guy.

But still she was saying sorry without a word of reproach about that.

What thoughts had been going through Kotobuki’s head as she typed up this message to me? How had she felt when I’d left her behind?

But even as I was moved by Kotobuki’s message, I couldn’t fully accept the words “don’t believe her.”

It didn’t seem likely that Kotobuki had bullied Miu. I wanted to believe my mother, too.

But what reason did Miu have to lie? I could never doubt Miu, who had hugged me and murmured so happily when she finally got to see me.

Miu had lost a lot of weight after two and a half years and had also cut short her pretty chestnut-brown hair that used to rustle in the wind. She looked boyish now.

But her eyes glinted like stars when she looked at me, just the same as before.

And her voice calling my name like sweet music, her joyful smile—everything!

The feelings I had for Miu, which buffeted me with a stormy ferocity from deep inside my body, made me despair and tortured me to the point where I thought my head would split in two.

What should I do? How was I supposed to respond to Kotobuki?

If I wrote down how I really felt, it would hurt her. If I pretended differently, it would be a lie.

My fingers grew steadily colder as they gripped the phone. I was staring at the screen so intently that it made me nauseous. Just then a knock came at the door, and my mother hesitantly entered my room.

“Konoha? One of your friends is here.”

“Wh—?”

“It’s Akutagawa.”

I gulped.

“Sorry for just showing up like this.”

“…No problem.”

A minute later, we were facing each other in my room.

Akutagawa sat down in a chair, and I sat gingerly on my bed.

I wasn’t able to look him straight in the eye; I looked down and fiddled with my nails.

“I needed to talk to you today.”

“…Okay.”

“You probably figured, but this is about Asakura.”

“Listen, Konoha.”

The words Miu had whispered in her hospital room, stealing a glance up into my eyes, echoed vividly in my ears. I felt as if my heart were being crushed in their grasp.

“Kazushi is definitely going to come see you tonight.”

“When he does, he’s going to look you straight in the eye and pretend to be the most honest guy in the world, and then he’s going to lie to you.”

When I looked up, Akutagawa’s back was perfectly straight, and he was looking at me with his sad, almond-shaped eyes. I couldn’t detect a trace of a lie or trick in his calm demeanor or in his serious expression.

“Do you remember when we talked in the classroom the day of the culture fair?”

“Yeah. I told you I wanted to be friends.”

I remembered that we had grasped each other’s hands firmly, cooled by the wind in the classroom dyed scarlet by the sunset, and my throat grew hot.

“I told you then that there was something I couldn’t talk to you about, remember? That I might hurt you someday.”

“You did. I remember.”

Even so, I had responded that I didn’t care. That I wanted to be friends for today, even if we fought or parted ways.

Deep in my chest, something grated, scalding me.

“Asakura was the thing I was keeping secret from you. I’ve known her for a long time now, and I’ve heard that there might’ve been something between you two.”

Akutagawa told me about how he’d met Miu the winter of his first year, when he had gone to visit his mother in the hospital. He didn’t hide how he had recognized me when he’d gone on to second year, and we became classmates, and how he’d torn up and thrown away the letters Miu gave him.

“I apologize for not saying anything about Asakura and for tearing up the letters. I’m sorry.”

Akutagawa bowed his head.

“Why…did you do it?”

My voice was feeble and hoarse.

“First, Kazushi will reveal how he met me and try to get you to lower your guard—”

These words of Miu’s shook my heart.

“And I bet he’ll apologize for throwing out my letters.”

“He’ll say they were about things he didn’t want you to see. That he thought it was better if we didn’t see each other because I was suffering from a mental illness. He’ll say that kind of awful nonsense to try and fool you.”

Akutagawa lifted his face and fixed his gaze on me once more.

“I’d convinced myself that she’d written the letters to malign you, so I didn’t want to force you to read them. She’s pretty unstable right now mentally. I wasn’t going to let her see you until she’d calmed down. Because I’d decided that that was best for you and for her.”

After he’d declared this without equivocation, he lowered his eyes in remorse and frowned.

“Maybe my rationalization was wrong. But that was the only way I could protect you and Asakura.”

The fact that it had tortured Akutagawa to keep this a secret from me came through plainly in his voice and expression. But his words resembled Miu’s predictions far too closely, and following directly on my yearning to believe him, I heard Miu’s whisper.

“Kazushi is going to come see you to tell you lies. Don’t believe what he tells you.”

“Not everything that Asakura told me in the hospital is correct. At least, I never pitted Kotobuki against her, and Kotobuki never did anything wrong to her. I just want you to believe that.”

“He’ll cover for Kotobuki, too, and try to make you think I’m the only one at fault.”

I wanted to believe Akutagawa.

But if I did, that would mean doubting Miu.

Why were both Kotobuki and Akutagawa telling me that Miu was a liar? She wasn’t! She wasn’t a liar!

I didn’t know how to contain the prickly feelings that raged inside me. I felt like I was about to cut loose and say horrible things. I had trouble breathing, and there was nothing I could do but bow to those feelings.

“Sorry—I need some time.”

I couldn’t possibly respond right now. It had taken all my strength to tell him that.

Akutagawa looked at me, his expression tinged with gloom.

“All right,” he murmured with difficulty and then went home.

Left by myself, I curled up on the bed, emotions burning through my chest.

The next day we weren’t able to talk in class.

All we did was offer each other an awkward “morning…” before quickly parting ways and not speaking another word after that. We even ate lunch separately.

When she saw us acting like that, Kotobuki’s friend Mori came over to talk to me worriedly.

“Inoue, did you have a fight with Akutagawa?”

“It’s not like that…but sort of.”

She must have sensed from my tone of voice that it was better not to touch on the topic, and she quickly changed the subject.

“Oh right—Nanase’s back in the hospital again. Would you go visit her for me, Inoue?”

“…Yeah, I saw her yesterday…I’ll go again today after school.”

Mori’s eyes popped.

“What?! R-really? So things’re going well with you and Nanase? Ha-ha…really! No reason to worry then, huh? Good, good. When Nanase gets back to school, I’ll have to do something nice for her.”

She went away, laughing in embarrassment. “Say hi to her for me.”

Her cheerful voice made my heart creak with pain.

When I stopped by her room at the hospital with black tea–flavored pudding, Kotobuki looked like she was curled up in her curtained-off bed, sleeping.

The girl she shared the room with called out to her, “Nanase, your boyfriend’s here.”

The white curtain swung open instantly, and Kotobuki stuck her head out, her eyes bright red. Her eyelids were a little puffy, too. She’d probably been crying last night. Guilt dug at my chest, and my breathing became strained.

The other girl left the room, and Kotobuki and I were alone.

“I’m sorry I didn’t answer your message. And about yesterday…I’m really sorry I didn’t listen to your side of it.”

“It…makes sense.”

Kotobuki hung her head.

“I’ve been hiding Asakura from you this whole time. And I did say harsh stuff to her…”

In a low voice, I asked, “When did Miu contact you?”

“At the beginning of December. I got a message from her on my phone.”

“On your phone? I wonder how she got your number.”

Kotobuki faltered.

Maybe she was wondering if it was okay to talk about Akutagawa.

“Did Akutagawa give it to her, maybe?”

When I murmured that, she looked up in surprise and said forcefully, “No! Akutagawa would never think to do something like that! I’m convinced Asakura took his cell phone and looked it up all on her own!”

She bit her lip and hung her head, perhaps feeling that she had gone too far.

Then she looked up at me cautiously.

“…Do you know about Akutagawa and Asakura?”

“Akutagawa came to my house yesterday to talk about it.”

Pain colored my voice. Every time I talked about it, a bitter taste spread through my mouth.

“What did he say?”

“The same thing you did. That not everything Miu says is the truth.”

“And what did you think?”

I didn’t say anything.

Kotobuki’s face became sad. She saw the bag in front of me. It was identical to the one I’d given to her with the pudding, and her eyes looked hurt. She murmured, “Are you…going to see Asakura after this?”

I couldn’t answer.

“Konoha! You came to see me again! Hooray!”

Miu’s eyes sparkled, and she leaned out of bed.

“Be careful! You’re gonna fall, Miu.”

I rushed to catch her in my arms, and she rubbed against my body cloyingly, giggling.

“It’s fine. See? You’ll catch me.”

When Miu teasingly brought her face close to mine, the sweet fragrance of soap that had always wafted from her tickled again at my nostrils.

Suddenly a sharp pain shot through my neck, and I let out a cry of surprise. Miu pulled away from me, put her long nails to her lips, and smiled cutely.

“Oh, I’m sorry. I was holding on too hard.”

Her long, sharp nails—like a cat’s claws—were out of sync with her short, boyish hair and plain pajamas. They were strangely alluring.

“Actually, I can’t cut my nails very well by myself. So I just let them grow out. I’m really sorry. Did it hurt?”

Her eyes were transparent as she looked at me in concern and her lips a faint pink as she murmured. Even though her hair looked like a boy’s, she appeared even more adult than before, and her pure white skin and large eyes exuded a charm that threatened to drag me under.

“No, it’s fine,” I answered, and she laughed in relief.

“Good. Y’know, I’m fine with walking now as long as I’ve got a cane. Right after I transferred to this hospital, I fell over constantly. I practiced over and over on the stairs and in the halls…because I had a goal.”

“A goal?”

“I wanted to see you, Konoha.”

Miu’s eyes crinkled as she gently smiled. Her cheerful, contented-looking expression made my heart constrict helplessly.

Miu looked down at my hands and let out a cry of joy.

“Ohhh! That’s black tea pudding! I’m right, aren’t I? You remembered my favorite store.”

“Y-yeah. Can you eat it on your own?”

Miu giggled again.

“That’s nothing. I can even write, although it’s messy. And I can use cell phones and computers. But I would appreciate it if you could take off the lid.”

The word “cell phones” made my heart skip a beat.

I took the pudding she held out to me in both hands, and as I pulled off the lid, I asked, “Do you…have a cell phone?”

She nodded yes.

“You never liked phones, did you?”

She had said she hated the sound of the ringer—that it was unpleasant and seemed to just intrude suddenly on her world. So she didn’t want me to call her. That’s what she’d told me before.

I passed Miu the pudding, and she gently scooped it up with a plastic spoon.

“That’s true. But with a cell phone, you can put it on vibrate and turn the ringer off, and texts aren’t that different from letters, so…Plus, it’s easier than holding a pen to write. Oh, you’ve got a cell phone, too, don’t you, Konoha? You have to tell me your number later.”

“…Okay.”

Had Miu sent a message to Kotobuki’s phone?

Had she stolen a look at her number off Akutagawa’s phone?

“Mmmm, this place really does have the best pudding.”

Miu was eating with a contented look on her face.

Just then I noticed a book sticking out from underneath the blankets, and I thought my heart would stop.

A thin hardcover with a sky-blue jacket. It was my—Miu Inoue’s—book!

The core of my body trembled, as if freezing cold water had been dumped over my head.

She must have noticed my horrified stare. Miu set her pudding down on the bedside table and slipped the book out from underneath the covers.

Like the Open Sky—by Miu Inoue.

She hugged the book to her chest, letting me see the title, and an easy smile came over her face.

The cover showed a picture of the sky, but it had been bleached in the sun, changing its color slightly. The pages had also turned yellow, warped and swollen, and tattered.

“I’ve reread this book so many times,” Miu whispered as she softly ran her finger over the title and the name of the author. “Really. So, so many times. I might’ve read it…a hundred times.”

My throat constricted tightly, sweat beaded at my temples, and it became difficult for me to breathe. Miu was staring straight at me with her catlike eyes. Her cherry-colored lips were ever so slightly curved in a smile.

I felt like a mouse being chased by a cat.

“It’s such a wonderful, beautiful story. Don’t you think?”

I forced the words out of my bone-dry throat.

“You read it that many times? I thought you might be angry.”

“Why?”

The air was weighing heavy and dark.

“Because…”

Because I stole your dream.

Because I got chosen for the prize you wanted.

Isn’t that why you jumped off the roof right in front of me that day?

The words tumbled through my brain.

I couldn’t ask her—