Contents

The beginning of winter was there, at the tips of my outstretched thumbs.

I snapped my fingers, and a burst of white, icy air escaped, plunging me into a midwinter freeze. Icicle chandeliers hung from the rafters, and the floor was a skating rink. The bed became a frigid coffin—even a vampire just back from an all-nighter would be loath to lie on that.

I watched snow crystals fall as I let out a puff of white breath. My hands and toes were numb. I shivered. Snow was piling up on my head and shoulders, but I couldn’t be bothered to brush it off. I was well on my way to becoming a snowman. If I fetched the red bucket from the garden shed and plopped it on my head, I’d cut a dashing figure.

…But that wintry wonderland was all a figment of my imagination. I was flesh and blood, sulking in one corner of Sunao’s mildly warm room, sitting with my back against the wall.

My outstretched feet were bare. Sunao had summoned me that morning before putting her socks on. Otherwise, I’d be wearing some.

Shizuoka might be blessed with a warm climate, but it still got pretty cold in November. It rained last night, and today was especially chilly. But tomorrow would probably be sunny; no matter how cold it got, we almost never saw snow in the heart of the city. All we got was rain, and I could hear it pelting the windows.

I hadn’t checked a weather app or watched the news, so I didn’t actually know what it would be like tomorrow. It might be partly sunny, rain cats and dogs, or turn stormy with thunder and lightning.

But since I wouldn’t be leaving this room, I didn’t need to know. Unless a meteor fell and landed on the roof, none of this cold drizzle would touch my skin.

I’m Sunao Aikawa’s replica—her handy replacement. She’d let me have an ordinary high school life for a little while, but that had come to an abrupt end. Five days ago, on Friday, November 5, she’d started attending school herself, just as she’d said she would.

Things had gone back to the way they were before, except for one key difference: She’d started calling me out while she was at school.

On weekends, there was a chance I’d bump into her parents, so she didn’t call for me then. But on weekdays, she’d leave me out from morning until evening. I felt like a dog left to guard the house, or a carved bear, or perhaps a bird trapped in a cage. Sunao had given me no directive. She’d call me out after donning her uniform, say good-bye, and then leave without another word. That was it.

A few minutes ago—or maybe an hour, or even longer—I’d heard the sound of the kickstand through the murmur of the rain. Then I’d seen someone in that cream-colored raincoat—though I could no longer tell if it was actually Sunao—ride off on that turquoise bike.

Once I’d watched this through the window, my one boring task for the day was complete.

If I got hungry, I’d go downstairs and boil water, put a pan on the stove, or zap something in the microwave. I’d eat overseasoned ramen, yakisoba, or pasta.

Today, I went with frozen udon. I microwaved it, mixed some mentsuyu soup base with water and poured that over the top, then slurped it up.

There was laundry hung up to dry in the combination living/dining room, and the smell of still-damp cloth clung to my nostrils. The simple flavor of the udon was far too basic to compete, and I didn’t taste a thing.

I looked at the clock on the wall and saw it was just past three—the middle of sixth period.

With my meal over, I went upstairs and sat back against the wall in a daze.

Sometimes, I wondered if Sunao was purposely trying to torture me.

Stamp your feet, gnash your teeth, know that you’re nothing but a replica!

Was that the message she meant to send? Or did she have something else in mind? I couldn’t tell, and I was too depressed to think about it.

I’d felt this way ever since the day she disappeared.

“Ryou.”

I spoke to the void, but it didn’t answer back.

Five days ago, they’d held an assembly in the gym to say good-bye to the former student council president, Suzumi Mori. I’d seen it through Sunao’s memories.

Lots and lots of people had lamented her untimely death.

Her friends cried and hugged one another, choking back sobs, sniffling, their voices full of sadness. All those sounds had pounded against Sunao’s eardrums like raindrops. Little cards with somber messages, one from each student in the whole school, were collected in a white box like a bowl of tears.

Suzumi. Moririn. Mori. President Mori. Each drop had a different sound, each tinged with the grief echoing through the gym—but not one person called Ryou’s name.

Ryou had been Suzumi’s replica, and almost no one had any idea. They hadn’t known before, and they would never find out. Even though she’d dazzled them all onstage during the Seiryou Festival.

I could feel heat behind my eyes. I was lying down, one cheek against the rug, and I felt a tear run down the bridge of my nose.

It passed between my cheek and brow, flowed into my ear hole, and was lost in my already wet hair. I shivered but couldn’t bring myself to reach up and wipe it away.

A raspy voice escaped from between my teeth.

“Ryou, I’m not allowed to go to school anymore.”

I’d likely never go again.

Had I dreamed the last month? Had I only imagined that I was at school every day, helping prepare for the festival, getting to know all those people, and laughing with them?

Had I only imagined meeting Ricchan again? Meeting Aki? Had I dreamed about performing in a play with Mochizuki and his friends? Now that I was shut out from the world beyond, locked in this prison cell, everything I’d treasured was vanishing like sea-foam.

Still lying on the thick rug, I pulled up my knees and turned myself into a ball. I was in the fetal position, as if trying to crawl back into a womb I’d never even been in.

I didn’t have to worry about wrinkling this skirt or getting this uniform dirty. Sunao wouldn’t care. The clothes I wore would vanish along with me.

I didn’t have to do the shuttle run.

I didn’t have to take difficult tests.

I didn’t have to do anything anymore.

And part of me was relieved that I didn’t have to go back to a school where Ryou no longer existed.

Aware of my conflicting feelings, I lay on the hard floor and screwed my eyes shut. That forced more tears out of my eyes, and they flowed down my face.

The rain kept falling.

For the first time, I felt like I understood why Sunao hadn’t wanted to go to school.

I’ve never slept in the nurse’s office.

I’ve gone there to have my measurements taken and after skinning my knee in gym class, but I’ve never had to borrow a bed.

Perhaps that’s true of most people. But in my case, it’s because I was at home in my own room, instead. If my head or stomach hurt, I wouldn’t leave the house. I would just stay in bed.

But unlike other students, I didn’t have to be marked absent for staying at home. I had someone to take my place, someone who’d go to school for me when I felt sick. I had another version of myself, who did whatever I said. That was the real reason I’d never slept in the nurse’s office.

I knocked on the door, but no answer came. I knew the person I was searching for was at school, so I went ahead and stepped inside.

The hall was damp from the ongoing rain, and the toes of my slippers slipped a bit as I crossed the threshold. The smell of disinfectant hit my nose.

The nurse must have been stuck in a morning meeting; there was no one on duty. Ignoring this, I moved to the third and final bed.

“Sanada,” I called, certain he was there.

I saw a shape stir through the white curtains—the only set drawn. They were closed tight, like a manifestation of their occupant’s mental state.

Don’t get close. Don’t talk to me, he seemed to say, pushing others away.

“I know you’re here,” I said.

I watched as he gingerly parted the curtains. I was nervous, too, but I made sure not to show it. I knew he was struggling a lot more than I was.

I hadn’t seen him since May. But there he was—Shuuya Sanada, sitting up in bed, wearing a white dress shirt.

He looked uneasy. Like me, he’d fled school and sought the comfort of his own room. And now that he’d left it, his skin was pale; he looked as guilty as he did uncomfortable.

“Aikawa… Morning.”

We barely even knew each other, but when he peered through his bangs at me, I saw his shoulders relax a little.

He had short black hair and dark brown eyes with thick eyebrows and broad, manly shoulders. Despite this, he seemed to hunker down, as if trying to make sure no part of him slipped over the edge of the tiny bed beneath him.

I pulled over a plain folding chair and took a seat. He watched in a daze.

There was a stool by the bed, but it was occupied by a neatly folded blazer, with his backpack stacked on top. I glanced at them without paying much attention, then brushed my hair behind my ear, conscious of how the humidity affected it.

“It’s been a while,” I said. “But it feels strange to say that.”

“…Yeah, since we’ve been talking on the phone,” replied Sanada, managing a faint smile.

The expression was far more subdued than any I’d seen him make back when he was the star of the basketball team. If we’d been in the classroom, the laughter and commotion would have sent this flimsy smile rolling across the floor.

“They’re picking groups for the school trip,” I said.

“Oh.”

The conversation died down almost immediately. We weren’t meeting each other’s eyes. In person, we couldn’t talk like we did on the phone. Our words came out a few at a time, like raindrops blown against the window.

“My parents hadn’t seen me in a while,” he said. “They were concerned. Said I looked pale. Suggested I should stay home today.”

“Well, that’s what you’ve been doing.”

Sanada had been holed up in his room for a long time. His family had only seen his replica—and that was who’d been coming to school, too.

I regretted the joke as soon as it crossed my lips. It felt like poking at a sore spot. I quickly stole a glance at his face, but his smile hadn’t changed. It didn’t look forced, either.

“Yeah,” he said. “It felt so weird to hear, I had to laugh… I heard the festival was a mess.”

“Did Aki fill you in?”

“Yeah, and my friends from the basketball team.”

“Right,” I said, letting the word roll around on my tongue.

At the after-party on the second day of the festival…something had happened.

I hadn’t been there, and Nao hadn’t told me the whole story. I’d only heard about it secondhand, but that was all it took to know the events had been a huge shock for everyone. No one knew what to make of it.

Someone had vanished into thin air. And now they were dead.

Just knowing a student at your school had passed away was shocking enough—especially if you knew her, or worse, had been friends with her.

Suzumi Mori had been student council president, so she was far more well-known than the average student. Even people at other schools knew her by reputation. She hadn’t exactly been famous, but she’d possessed a friendly disposition, excellent grades, and dazzling beauty. Thanks to those three things, a lot of people had admired her.

She’d been in the middle of a speech when she’d vanished, leaving only her uniform and slippers behind. Every eye was on her, and yet she’d disappeared without a trace.

There’d been no school for the next two days—one was a holiday, and the other was a make-up day for the festival. And on November 4, the students had been informed of her death.

I was a year below her, but everyone seemed to think we’d been really close. Teachers offered words of encouragement, and several classmates came to talk to me. All I could do was nod evasively, and they all assumed I was just trying to hide my grief.

But that wasn’t the case. I hadn’t even known her.

She’d likely been a replica, attending school in place of the real former student council president. If the original dies, the replica goes with her. And this replica had grown quite close to Nao.

I’d known Nao was cast in a play and that she was working with the Drama Club to ensure the Literature Club’s survival. I’d seen posters for it on the walls on the first day of the Seiryou Festival, and Ricchan had filled me in when I stopped by the clubroom.

In hindsight, I recalled Nao nervously telling me something about flyers blowing in the wind. I hadn’t thought much of it—I’d had other things on my mind. And that indifference had probably discouraged her from telling me about this new replica. I could imagine why.

But if I’d known about it in advance, would I have done anything differently? Would I have been able to help Nao with the pain of losing someone close? Could I have comforted her when she came home with red, teary eyes? No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t even begin to imagine myself doing that.

This morning, the school formally announced the cancellation of the Seiryou Festival Awards (previously postponed). Considering the shadow still cast over the student body, it was certain no one would be able to smile when the winners were announced and called to the stage to pull a prize from the raffle box. We’d all known the teachers would eventually make this decision.

This year’s festival had ended without the usual parties or memorial photos. The shock and grief had spread through us like a pestilence, banishing all joy.

Even now, five days later, that dark cloud was still hovering over all our heads. I could sense it, but I felt somehow removed from it all, remote.

I knew this mood wouldn’t last long.

Next week, the second-years had a school trip. It would last three days and two nights—a huge deal in any high schooler’s life. The deceased was a third-year, and the second-years hadn’t really known her. There was little reason for most of them to drag these feelings out.

Once they returned from the trip, they’d be totally over it. The first-years would follow suit, then the third-years, and the death of their fellow student would soon be a thing of the past.

Some people might call that unjust or heartless. But there was nothing wrong with forgetting pain. Nothing.

While I was thinking all this, Sanada said nothing. He had his head down and his lips drawn tautly together. It was as though he was enduring something.

Concerned, I asked, “You okay there?”

It came out a little blunt. This is why I’m bad at these things, I thought. I was left unsure of what to say next, though Sanada seemed oblivious.

“Not…really,” he rasped, tense.

He sounded pretty far from okay, but pointing that out would just be mean.

Shuuya Sanada had become a much weaker person than he’d ever seemed before May. Spending time away from people made you shrivel up and lose your confidence. Just getting to the nurse’s office must have taken a lot out of him. Searching for a sympathetic word, I moved my lips, then gave up.

I wasn’t good at being supportive. I’d just say something unpleasant and make everything harder for him. I was better off not saying anything at all. So I didn’t—until the silence was broken by the door bursting open.

“’Sup! It’s ya boy, Yoshii!”

I knew who it was instantly—the class clown. Frank and permanently upbeat, he had tons of friends—both boys and girls, and even students from other classes. Simply put, he was the sort of guy who got tons of chocolate on Valentine’s Day and whooped it up but who never actually got asked out. You know the type.

Our eyes met, and Yoshii whistled. He produced a good sound, which made it extra aggravating.

“Figured you’d be here, Sanada,” he said. “And my hunches are always right!”

“You could at least knock,” I said. Sanada had flinched, so I spoke for him. Yoshii blinked at me.

“Hm, what? You’re sure in a mood today, Aikawa! Far cry from all those cute noises you made in the haunted house.”

“Don’t be a creep.”

“Oof! Haven’t lost your edge, I see!”

He made a show of rubbing his forearms, further annoying me.

He sat right in front of me in class, but I’d barely spoken to him. We’d passed more printouts back and forth than we’d exchanged words.

That had originally been the case for Nao as well. Following my lead, she didn’t actively speak up in class. But that hadn’t been an option during the run-up to the Seiryou Festival. I was aware she and Yoshii were friendly now, but that didn’t make things any easier for me.

How did I seem to him when I was me and not Nao? To be honest, I really didn’t want to find out.

He broke off his obnoxious teasing and turned his attention elsewhere. Rather than peer into the bed from behind me, he went around to the window side and jumped headfirst onto Sanada’s bed.

“Incoming!” he shouted. “Hey, these things are actually pretty comfy.”

Sanada had been gaping the entire time, and the sudden proximity rattled him even more. He was visibly shaking like a kitten abandoned in the rain, at a complete loss as to how to handle Yoshii’s behavior. The covers were thick enough that Yoshii didn’t seem to notice, however.

“Oh yeah,” said Yoshii. “Sanada, can I ask ya something?”

“Huh?”

At the sudden question, Sanada fixed his eyes on me with a silent plea. I considered helping him, then thought better of it.

“So, like…,” Yoshii began.

“Huh? What is it…?”

I knew why Sanada was frightened. He was scared of questions about why he wasn’t in class, why he was holed up in the nurse’s office, and so on.

Yoshii briefly glanced at me, then smirked.

“Say it isn’t so,” he whispered. “You and Aikawa weren’t up to any hanky-panky in here, right?”

Though his voice was low, I was right there, and I heard every word. The joke was so infantile, I didn’t even have it in me to get mad. I just rolled my eyes.

Sanada blinked, and Yoshii elbowed him in the shoulder.

“I mean, everyone knows you two are tight! We’re besties, so you can’t fool me!”

Just then, Yoshii paused his obnoxious banter and seemed to work something out.

“Wait, are you legit sick? Am I being a total jackass? Lemme make up for it by sharing your bed! I’ll cuddle you to sleep!”

He was far too close for comfort, and Sanada wasn’t sure how to take it at all. His head was down, but I could tell he was starting to put two and two together. I smiled. It seemed the truth was beginning to dawn on him, too.

Shuuya Sanada might have been holed up in his room. But that wasn’t how anyone else saw it. They thought Shuuya had been out with a broken bone in May, then had come right back in mid-June, like nothing had happened. He’d even trounced the guy who broke his ankle in a basketball match. That was how it looked to the rest of the school.

Now that he’d figured that out, things would go a lot easier.

Sanada didn’t need to be scared of anyone—he could simply act normal. No one was going to give him any funny looks.

“…Puh-leez,” he said, making a face at Yoshii. “Nobody wants to share a bed with you.”

It was a natural reaction. There was a slight tremor in his voice, but Yoshii didn’t notice.

“Oh-ho!” he said, grinning. “That’s more like it! You just playing hooky, then?”

At this point, the door burst open again.

“Heeey!”

I looked up and saw Kozue Satou, the president of Class 2-1. Her shoulder-length hair danced as she entered the room. When she saw her classmates inside, she frowned.

“I thought I heard your voice!” she declared. “I see Sanada’s here, too. What are you two up to?”

“That’s mean, Prez!” said Yoshii. “Don’t leave Aikawa out!”

“Oh, hey. I didn’t even see you there,” she replied.

“Augh! So I was the invisible one?!” Yoshii made a dramatic show of wiping nonexistent tears from his eyes.

I raised a brow at Satou. “What brings you here?”

“We were deciding on groups for the trip. The boys sorted out okay, but the girls are still squabbling. Couldn’t stand the heat, so I hopped out of the frying pan.” Satou stuck out her tongue. “I was wondering if you were doing the same, Aikawa. Is that what brought you here?”

I shifted my gaze uncomfortably. The moment they’d started discussing groups in homeroom, I’d slipped out, claiming I wasn’t feeling well. I’d just wanted an excuse to check up on Sanada, but my classmates didn’t know that.

“I know the girls were struggling,” said Yoshii, “but isn’t it your job to sort that stuff out?”

“Well, the groups are mostly decided. The real nightmare is the room assignments. You’ve got groups of friends who promised to share already, right? So now they’re teaming up and saying things like, ‘Even if she comes up to you, just smile and act evasive. Don’t commit to anything yet.’” Satou put on a soft, ingratiating voice.

Yoshii shuddered. “Yikes, horrifying.”

“And our class is hardly the worst one.”

I figured that was because Satou was in charge, but I didn’t say that out loud. Even if I watched my tone, she’d probably take it as a dig.

Yoshii perched on the windowsill, chin in hand. “Huh… So the three of you haven’t picked a group yet?” He looked at each of us in turn.

Having this called out was aggravating, but it was true. I couldn’t deny the facts.

“You’re in the same boat, Yoshii,” Satou said.

“Yep.” He nodded, like it was no big deal. This surprised me.

Yoshii glanced around, then clapped. “This must be a sign!” he declared. “Why don’t the four of us team up?”

Caught off guard, I blinked three times.

For a moment, I thought he was just being a dumbass again—but the idea itself wasn’t bad. The rules said groups should have four or five people and include both boys and girls. We just happened to check both those boxes.

I hadn’t mentioned it to Sanada yet, but I’d been angling to get into a group with him. I was the one who’d pushed him to come back to school today, after all.

Since we were both officially in the Literature Club, it wouldn’t seem weird, either. So before anyone could argue, I pounced on Yoshii’s proposition.

“That could work,” I said.

“Huh? Really?” It was his idea, yet my answer seemed to shock him.

“That works for me, too!” Satou said. “Then it’s settled. The four of us are a team! Though I could’ve done without Yoshii.”

“I’m sensing some hostility here!”

“What do you say, Sanada?” she asked, ignoring Yoshii’s protests.

He nodded, caught up in the moment—and that was that.

“Can you make it to second period, Sanada? We’ve gotta pick a theme for where our group goes.”

“What kind of theme?”

“Oh, you know. Handicrafts, traditional gardens, old-fashioned paintings, sweets that go with green tea…each group has to pick a focus. That theme is meant to decide where we go on day two.”

Satou was used to giving such explanations, and she counted off the various options on her fingers as she went.

The first day of the trip, we had to stick with our class. But on the second day, we’d split into groups and explore our chosen theme. On the third day, we were free to do whatever we wanted.

“You put a lot of emphasis on ‘meant,’ huh, Prez?”

“I mean, you know how it actually works. Everyone picks a theme that matches where they already want to go. Just remember, each group’s gotta do a presentation after getting back. If we half-ass it, there’ll be hell to pay.”

As Satou and Yoshii spoke, they headed out into the hall.

As I got up to follow, I heard Sanada whisper, “He did this.”

“Who?” I asked.

As he put on his blazer, he answered in a voice much smaller than he was.

“Number Two. Aki…my replica.” He wasn’t looking at me. “I wasn’t here, so I had my doubts. But he really did fill in for me.”

I felt the same way. I hadn’t made friends with Satou or Yoshii—that was all Nao. Sanada and I were just riding our replicas’ coattails.

Sanada looked up, and his eyes met mine. I flinched and averted my gaze.

“I’m glad you brought me back here, Aikawa,” he said. “Thank you.”

“I—I didn’t do anything.”

I made a face. I really didn’t deserve his thanks.

Sanada and I had both created replicas. I’d never had anyone else to talk to about that before. So when I was at home, I’d occasionally chat with him on the phone. It was the first time I’d ever been that close and personal with a boy, and it was kind of nice.

It was a little weird, timing-wise, to suggest that he come back right before the school trip, but that was exactly why I’d picked it. The second-year trip was just after the festival, while everyone was still excited. I thought it would be a lot easier to ease back in than it would be during a regular week.

The former student council president’s unexpected death had thrown a wrench in that plan. That was probably part of why both Yoshii and Satou had sneaked out of class. It must have been hard for them to keep up with the hubbub and act like nothing was wrong.

Then again, Yoshii wasn’t exactly delicate. Maybe he’d just noticed his new buddy, Sanada, wasn’t around and had swung by to kill some time.

Sanada was back on his feet, his arms through the thick straps of his backpack. His right ankle was still bothering him a little, but he wasn’t dragging it. Apparently, he’d spent the last month walking near his house during times when few people were around, and it seemed this rehab had paid off.

He bent his head slightly and scratched his cheek. It was hard to tell if he was bowing to me or just looking at the ground.

“Either way, I’m grateful,” he said.

I figured further argument would be futile and settled for a slow nod.

I hadn’t told him anything about my goals. Arguably, I was only using him. If he was thanking me for that, then he was just gullible. Briefly, I wondered if that was why that egomaniac Hayase had it in for him.

Forget the bad things. There’s nothing wrong with forgetting.

But the worse something was, the harder it was to forget. I had a feeling those awful memories of Hayase would haunt Sanada forever, coming back at the strangest times.

And in that case, I really hadn’t done anything to deserve his gratitude.

“Let’s have fun on the trip. We’re in the same group, after all.”

“…Mm.”

I nodded without turning around, already on my way out the open doors.

The school trip was next week. But what mattered to me would come right before that.

The bell rang, announcing the end of first period. I was getting worked up, and my first step into the hall sounded awfully loud.

On Friday, November 12, I once again saw Sunao off without a word.

I looked up and found the sky bright and sunny, in complete disregard of my mood. I watched Sunao leave through the window, then turned back to find her Japanese textbook lying on the desk.

“…Ack.”

I mentally ran through her schedule. I was pretty sure she had Japanese class that day.

The textbook looked lonely, so I picked it up and moved toward the door. But running after her now wouldn’t help. No matter how slowly Sunao was pedaling, my feet could never catch her. And we couldn’t afford to have anyone see us together.

I gave up and flopped facedown on the rug, then started flipping through the textbook. The light from the window was more than enough to read by.

I checked Sunao’s memories and realized they’d been reading “The Moon Over the Mountain.”

This was a short story by Atsushi Nakajima set in Tang Dynasty China. A man named Li Zheng dreams of becoming a poet. Unable to achieve this, he becomes a tiger. The story narrates his encounter with his old friend Yuan Can, to whom he relates his story.

When I first read it, I wondered what it would be like to suddenly transform into a tiger—fear and excitement buffeting me in equal measure. Eventually, it occurred to me that if I became a tiger, that would mean Sunao had become a tiger first, and that made everything seem less scary.

As I remembered this, I followed Li Zheng’s words to Yuan Can with my eyes. In no time at all, I’d finished “The Moon Over the Mountain” and moved on to other stories and new adventures.

I enjoyed letting my whims carry me through pages we’d skipped in class.

The Japanese textbook was stuffed full of prose and poetry, tanka and haiku, and even critical essays. Stories were neatly lined up in little rows, pouncing out at me like a jack-in-the-box each time I turned a page, begging me to join them.

I ran my finger down a poem I’d never read before as words and phrases danced, so bright and beautiful that I let out an appreciative gasp. Each new page took me to another place, another time, and showed me its unique sights and sounds.

Lost in the stories, I heard a drawn-out ding-dooong.

Startled, I pulled my nose out of the textbook.

Who could that be? If it was Mom, she wouldn’t ring the doorbell. It could be a parcel delivery or maybe news from the neighborhood association.

I got up and left the room, then hustled down the stairs. I was almost at the bottom when I realized it was a weekday. There shouldn’t be anyone at home. When Sunao’s parents ordered deliveries, they always specified evenings or weekends. And the neighbors all knew that stopping by during the day would be a waste of time.

Figuring it must have been a door-to-door salesman, I moved down the hall to the entryway.

I was cautious enough not to open the door right away. I called through it, “Who’s there?”

“Me,” came the answer. It was only a single word, but I’d know that voice anywhere.

A whim struck me, and I said, “Is that the voice of my friend Li Zheng?” as if asking for a password.

The person beyond this door might be a stranger well-versed in the works of Atsushi Nakajima. Then my clever gambit would be meaningless.

But I knew he’d catch my drift. This boy might sit behind me in class, but I knew he often covertly read the other pages of the textbook, just as I did.

“Indeed, I am Li Zheng of Longxi,” came the reply.

I opened the door.

As I’d suspected, I found not Li Zheng of Longxi but Aki of Yaizu.

He was in our school’s winter uniform, and the sun behind him—without any window glass to block it—was astoundingly bright. I had to shield my eyes. The searing pain in the back of my corneas made me want to scrunch my face until it turned inside out.

“Aki? Shouldn’t you be at school?”

“Shuuya’s going, so I’m staying at home. Not sure if he’ll keep it up, though.” It had been several days since we’d seen each other, but he seemed to be taking it in stride. “I heard from Aikawa that she’d be the one going to school from now on and that you’d be at home alone. So I figured I’d come see you.”

“…Oh.”

Sunao and Sanada were going to school, and they were in the same group for the trip. I’d seen all that in her memories, but hearing it again directly from Aki made me visibly deflate.

Starting last summer, the two of them often spoke on the phone. I knew Sunao had talked Sanada into coming back to school after the Seiryou Festival. I remembered hearing Sunao’s laughter through her door when I got home. On the other end of the line, Sanada had been laughing, too.

It wasn’t just me. Aki probably wouldn’t be going to school anymore, either.

And that might not be all. From now on, maybe we were no longer…

“Nao, do not forget Ritsuko of Ishida Road,” said a familiar girl, popping her head out from behind Aki.

“…Ricchan!”

“Ciao, Nao. It’s been far too long since my feet took me to Mochimune, much less to the Aikawa estate! I am awash in nostalgia.”

Ricchan had brought her usual good cheer along. I knew she was doing this for me. I tried to smile back, but I doubted it was very convincing.

“What brings you here?” I asked. “Aki’s one thing, but shouldn’t you be at school, Ricchan?”

I received no answer, and Aki got right down to business.

“Nao, let’s hit up a hot spring,” he said.

Completely lost, I blinked at him, my hand still on the door.

“A hot spring?” I asked.

Where’d that come from?

“Yes. It’s cold out.”

“It’s very cold out!” Ricchan chimed in, making a show of shivering.

The skies were clear, and it was a nice, comfortable temperature. It was not especially chilly.

“Hmm.”

I’d never been to a hot spring. But I didn’t think going would cheer me up, so I hesitated.

“We’re here, and you’re coming!” said Ricchan. “I’ll help you grab a change of clothes!”

“Uh, Ricchan?”

She shoved me roughly back into the house.

“Wow, everything’s the same!” She looked around the front entrance, delighted. “My memory synapses are lighting up!”

She was right—not much had changed since the days when she used to come over all the time. Sunao’s parents had remodeled the toilet, but otherwise, it was the same house Ricchan knew.

She pushed me all the way to the changing area outside the bathroom.

Sunao always kept her favorite clothes in her room, but she kept pajamas and house clothes in the closet by the changing room. Her underwear was there, too.

Ricchan grabbed a T-shirt with a cartoon character on it and a pair of shorts. She must have assumed I’d be overheated after getting out of the hot spring water.

I hesitated, then picked out some underwear. I chose well-used items Sunao was already considering throwing out.

“I think Sunao will be upset if I borrow her clothes without permission,” I said, suggesting I’d rather avoid that fate.

But Ricchan didn’t seem to understand. “Then I’ll come get yelled at with you!”

The fact that she didn’t try to assure me it would be fine proved how well she knew Sunao.

She put the clothes and a towel in a spa bag and headed back to the door. Aki had his back against the peeling fence, waiting for us.

“Ready?” he asked.

“Yep. We’re off!” exclaimed Ricchan.

I still wasn’t committed, but in the end, I locked the door. Once that was taken care of, Aki took my right arm and Ricchan my left, and my thoughts briefly cut out.

“…Hm? What’s this for?”

“You might try to run,” Ricchan declared.

I couldn’t refute her, so I said nothing.

We went out into the street and passed the red post office box.

Watched over by clear fall skies, the three of us moved along familiar streets. Aki and Ricchan refused to let go of me even when cars passed, so we had to shift into a perpendicular arrangement.

We must have looked like little kids—or maybe like two cops escorting a prisoner. If they both leaned all the way over, we’d be doing a cheerleading move.

I saw three cats sunning themselves in a vacant lot I was sure used to be something else. Mochimune was a port town and had quite a few cats wandering around.

Sparrows were chirping, out for an elegant stroll on the power lines. There was an unmanned stall by the road, with a single head of Chinese cabbage sitting unclaimed for 200 yen.

It was a peaceful morning. Each of us bowed, totally out of sync, to an old man with a cane. And as we did, I tightened my grip on their hands.

It felt like forever since I’d touched anyone or exchanged any words that meant anything. Over the last few days, all I’d touched were walls, rugs, doors, and noodles.

“What hot spring are we going to?”

Only then did my mind catch up enough to ask this key question.

We were headed away from the station, so I assumed no buses or trains were involved. I looked up at Aki, and he turned to meet my gaze.

“Mochimune Minato Hot Spring. Ever been?”

I shook my head. I knew they’d built the place a few years back, but I’d never gone.

“Sunao’s mom said they’d have to go if our bath ever broke.”

Fortunately, or rather, unfortunately, the bath was still working fine. It was within walking distance of home, yet nobody in the family had ever gone.

“What about you, Aki?”

“Yaizu people are all about the Kuroshio Hot Spring. Though these days, it’s officially known as the Yaizu Hot Spring.”

Apparently, he’d never been, either.

“Ricchan?” I said, turning to her.

“We said we’d go if our bath broke.”

We all had fine, sturdy baths, it seemed.

We headed straight down the road through the residential area to the harbor. Then we turned right and walked along it, the smell of ocean and fish on the breeze.

“There it is,” said Ricchan.

A black-walled building waited for us on the harbor grounds. Beneath its roof, we saw the symbol for hot water on a few fluttering banners.

“Apparently, this building used to be a tuna processing warehouse, so we may see some ghost tuna around,” she explained.

“Are tuna known to haunt people?” I asked.

“I suppose one really only hears about human ghosts. I wonder why?”

As Ricchan hummed in thought, I looked around the parking lot. It was a weekday morning, yet almost every spot was full.

We made our way around it toward the entrance. Now that we’d arrived, Ricchan let go of my arm surprisingly easily.

“I’ve got to solve this ghost problem, so I’m headed back to school! I was only really here to get a look at Nao.”

“Huh?!” I gaped at her. “You’re not going in?”

She made a silly face. “Tragically, I’m a semi-serious student, and I can’t have my parents asking, ‘Where’d you go wrong, Ritsuko?!’ If I grab a train and a bus, second period…is probably impossible, but I can at least be there for third period.”

Aki and I, the resident unserious students, chose silence.

Ricchan really had come all this way just to see me. It was probably her first time skipping class. I suddenly felt guilty and grabbed her hand.

“Ricchan, you shouldn’t have.”

“Don’t be like that! I’m the one who came charging in. It was a novel experience!” She winked at me, then her expression turned serious. “Nao, you look even worse than I feared. Let this spring warm you up again.”

She patted my dry cheeks with both hands. Her little palms felt very comforting.

“Okay. I’ll bathe enough for both of us,” I said.

“That’s the spirit!” She smiled slightly, staring up at me through the frames of her glasses. “Remember what I told you. I wasn’t kidding. If you’ve got nowhere to go, you come to me. Do not go disappearing again.”

I knew she meant what she said, and that made me feel even guiltier.

I was starting to confront things I hadn’t yet taken notice of at the beach back in the summer, and Ricchan was sharp enough to notice.

It must have taken courage to say all that again. But Ricchan didn’t hesitate. She was my friend, and she was always worried about me.

“…Thanks, Ricchan.”

All I could give her in return was words. But she flashed me a grin and nodded emphatically.

“Laters! Tell me how the spring was!”

We waved good-bye, and she trotted off toward the station.

After that, Aki and I made the plunge and headed into the building.

The Mochimune Minato Hot Spring exterior looked brand-new, and the interior was clean and tidy.

We left our shoes in the lockers provided and took the keys with us. I had locker number 52, and Aki had the one to the right: locker number 60.

Tickets were available from two push-button machines. We paid the standard weekday fare. We weren’t on the committee or under twelve, so we took the 900-yen general admission. I took a 1,000-yen bill out of my pink wallet and fed it into the starving ticket machine.

My fortune was now 188,240 yen. I’d been doing my level best to get back to an even 190,000 but was constantly thwarted by my own desires. It was a battle without honor.

Tickets in hand, we moved to the front desk. The lady there, wearing a red T-shirt in lieu of a uniform, shot us a skeptical look. I wondered why, then gasped.

We were both in our school uniforms. It was a weekday morning. It was only natural to wonder why two students were here.

“Er, um…”

Silence would arouse suspicion. I needed a valid excuse, but my brain refused to come up with anything.

When I fell silent, Aki spoke up.

“It’s Founder’s Day, so there’s no school.”

Huh?

The lady nodded and handed us changing room keys attached to wristbands. She didn’t seem inclined to pry any further.

Glancing briefly at the gift shop and cafeteria, we headed through the lavender curtains to the hot spring area.

The hall was lined with framed black-and-white photos of the Mochimune Beach teeming with swimmers and panoramic shots of the town. I wondered when they were taken.

Gazing at them, I asked my knowledgeable boyfriend, “So Surusei was founded today?”

“Probably not.”

Whaaaat?

Apparently, Aki had been lying. I had to hand it to him—that had been audacious.

Once we’d looked at all the photos, two sets of curtains waited for us: red for women and blue for men.

“Let’s meet up in the lounge once we’re done,” said Aki.

“Yeah. See you then.”

I went left, and Aki went right.

There was no one in the changing room, but I could hear water running in the bathing area.

I found the locker with the same number as my key and put my things inside. Then I reached for my skirt—and discovered something appalling.

“…Augh!”

The fabric was all wrinkly. There was even dust on my hip!

I checked the changing room mirror and became even more shocked. Rolling around on the floor had really messed up my hair.

Now I knew why Aki and Ricchan had both seemed so worried. I was a disaster! They must have been horrified.

How mortifying. Red-faced from embarrassment, I got undressed and headed out of the changing room carrying only a white towel.

I glanced around, my heart racing—but the bathing area was very serene. The ceiling and upper walls were white, while the lower walls were black. The lights cast a soft orange glow.

There was a sauna and three baths, including a cold water one. The carbonated water bath in the center looked quite popular; most people were using that one. There was also an outdoor bath.

After looking around, I grabbed a bucket and splashed water on myself. I wasn’t just washing the grime off my body—this practice supposedly helped prime your body for the hot water, too.

I moved to the washing area and made sure my hair and body were thoroughly clean. Then I wrapped a towel around my long hair and rose to my feet.

I’ve gotta try the outdoor bath first! Nothing else will do!

I hyped myself up, but what I found outside wasn’t much like the outdoor baths on TV, and there wasn’t much of a view. Most of the sky was covered by the building’s roof, and a wooden fence blocked most of the scenery.

My attention was immediately drawn by something called the “Fuji View Hut.” It covered about a third of the bath, and it sounded like you could see Mount Fuji from inside.

The smell of cypress tickling my nose, I moved through the water to the hut’s entrance.

The dimly lit interior felt like a secret hideout, and it made my heart dance. A window inside provided a great view of the harbor, and it was a clear day, so I could just make out Mount Fuji’s fancy white hat.

Gazing out at the view, I settled in, my elbows on the rocks. The water was perfect—not too hot.

Now that I thought about it, this wasn’t some secluded mountainside. We were right up against the city’s harbor. Without the walls and roof, the bathers would be left totally exposed. They were necessary countermeasures.

But this hut made it feel like I was the one doing the peeping, and that thought made me giggle.

I was considering whether I could simply live in this hut forever, when I heard some people talking. I forgot my fleeting dream and crawled out. I didn’t want to monopolize the view, after all.

Next, I explored the interior baths, finally winding up in the carbonated water. Countless bubbles hugged my limbs.

“…So warm.”

I stretched, and the bubbles fled. The water splashed and bubbles burst, and my smile grew wider and wider.

“Hot springs are amazing.”

A gush of warm air escaped my lungs in a satisfied sigh. That was when I idly glanced at the clock.

It was ten past noon. I started to look away and then did a double take.

When Ricchan left, she’d said second period had already started, but she could still make it in time for third. Second period began at ten and third at eleven. Had I seriously lost myself in these waters for nearly two hours?

Aki and I had arranged a location to meet but not a time. We weren’t used to splitting up, and we’d made a very basic error.

Was he already out? Or was he still soaking?

I considered this for a moment. I had a preconceived notion that girls always took more time in the bath than boys. Dad was a quick dipper, while Mom could stay in for a couple of hours. Once or twice, Sunao had even found her sound asleep in the water.

A minute later, I reached my conclusion: I shouldn’t keep Aki waiting any longer. I’d wanted to roast myself in the hum of the infrared sauna, but there was no time for that.

I splashed my way to the edge of the bath and left the water.

I dried myself off, then entered the changing room. Two college-age women were sitting on chairs by the mirror, chatting. They curled their eyelashes while discussing where they’d eat lunch. It seemed they were planning to go to Hut Park Mochimune along the coast.

My body was still piping hot as I threw a shirt over my head. Just then, something fell to the floor: my light blue scrunchie.

I didn’t remember bringing it. Had Ricchan stuck it in with my change of clothes? It was a dramatic touch and very her.

I used a dryer on my hair, then loosely tied it up with the scrunchie.

My hair half-up, I inspected my reflection in the polished mirror. I was myself again, for the first time in a while.

I checked my appearance from every angle, nodded, then left the changing room, my bag much heavier.

I looked around the lounge but didn’t see Aki anywhere. He wasn’t in the gift shop or cafeteria, either.

Somehow, I’d managed to finish up first. I was relieved I hadn’t left him waiting. Then I heard footsteps rushing up behind me.

It was Aki, pushing through the curtains. He wore a brown shirt and black pants.

“Sorry. A local old-timer started bending my ear in the sauna.”

He must have found it hard to extract himself from a situation like that. I could picture it easily and started laughing.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I just got out myself.”

He looked relieved, but he’d been in such a rush, he’d barely dried his hair. His was fairly short, but leaving it wet was still risky. He could catch a cold like that.

I pulled a face towel out of my bag. “Aki, you’re dripping.”

I reached up and tried to dry him off. But he realized what I was up to and brushed me off, embarrassed.

“I’ll do it!” he insisted.

“Stand still.”

His brow furrowed—and my heart made a strange noise.

“…Nao? What’s wrong?” he asked, realizing I wasn’t moving.

The sight of his shiny, wet hair made my pulse quicken.

That was the only difference—his hair was just wet. That was all!

I told myself as much, but the change made him seem younger and somehow vulnerable. This was a sight only his family had seen before, but now I’d caught a glimpse, too.

But I couldn’t tell him that. I roughly dried his hair and neck, trying to hide my consternation.

“Hey, ow!” he grumbled, then grabbed my wrists.

His big hands felt warm, and his whole body smelled just like mine did.

Our eyes met, and he made a face. “It’s like we’re living together.”

“Oh? Y-yeah?” I stammered.

Without batting an eye, he added, “That was a real mom move just now.”

“…That sounds like a bad thing,” I huffed.

That wasn’t the reaction I’d been hoping for. Realizing he’d upset me, Aki awkwardly changed the subject.

“It’s noon. Are you hungry?”

I raised an eyebrow but followed along.

“A little.”

I was pretty hungry.

I’d spent a few days shoveling food in my stomach only when it started growling at me, but this was nothing like that. I was feeling much better. The hot spring had warmed me up. Ricchan and Aki had pulled me out of my funk.

The cafeteria here was crowded, so we decided to eat elsewhere.

We went outside, and I noticed the stone walls by the entrance. When we came in, I hadn’t seen them or the sign posted high up on the side saying there was a gray heron nest around.

The sign featured a very cute picture of the mother bird and her babies. The cafeteria inside the hot spring had been called the “Gray Heron Diner,” probably because of this nest.

I hopped up and down a few times, hoping to catch a glimpse, but the grass was too tall, and I couldn’t see anything.

“What?” asked Aki.

“It says there’s a gray heron nest.”

“Interesting.”

“Can you see it, Aki?” I asked, still hopping.

He was taller than I was. He craned his neck, shielding his eyes with one hand.

“Not at all. Wanna swing around the other side?”

“Yeah!”

Looming over the walled-off section was a parking lot. We didn’t want to startle the birds, so that seemed like a good place to stand and look.

“Where is this nest?” asked Aki.

“Good question.” I couldn’t see anything resembling one. While we looked, someone’s stomach growled, and I put on a concerned look. “Aki, you’re clearly starving. We’ll have to find this heron some other day.”

“That wasn’t my stomach.”

I pretended I hadn’t heard that and led the way out of the parking lot.

“Where should we eat?” Aki asked.

“Good question. There’s lots of restaurants around here.”

Mochimune was still growing, and the number of restaurants was increasing along with the population. Sunao had been to these coastal shops and eaten dango, burgers, and gelato.

“What about Minato Yokocho?” he asked. “I’ve had my eye on it for a while.”

This collection of restaurants was a gourmet highlight of the harbor area. A few years back, it had looked extremely retro, but after some renovations, it had turned into an upscale hot spot. And it was a short walk away, right under our noses.

“Let’s go. But what are we eating?”

“I’m feeling fish.”

“Ah,” I said, deliberately sounding impressed. “That must be the Yaizu in you.”

“More like I could smell fish from the hot spring.”

“I could, too!”

While I was in the carbonated bath, a breeze had come in through the open windows, and for a moment, I’d smelled the unmistakable aroma of fish.

Perhaps it was a conspiracy by the harbor authorities to trick bathers into eating seafood. We gave that some serious discussion as we made our way to Minato Yokocho. And once inside, we chose a seafood place called Jiromaru.

Through the windows, we could tell it was full—but a customer had just stood up to pay. We waited outside, looking around—the interior was just as stylish as we’d heard. There was a single red lantern hanging nearby. Very cute.

After a while, the server let us in and seated us at the counter along the window. We had a great view of the harbor, and it felt like we’d really lucked out.

“What do you want? I’m buying,” said Aki, though he admitted he’d be using Shuuya’s money.

“In that case, I’m going for broke!” I said, and we pored over a single menu together. “There’s so many options!”

There were lots of rice bowls, as well as sushi, and even whitebait pizza! All the options were tempting.

Mochimune was one of the top spots in Japan for whitebait, and we had it a lot at home. Sunao preferred it boiled. I knew she liked to heap it on hot white rice with chopped scallions.

Thinking about whitebait gave me a craving for it. I’d barely ever eaten dinner, so whitebait was a rare treat.

“I’m going for the half-and-half bowl,” I said.

It was half-raw and half-boiled, but all whitebait.

“That must be the Mochimune in you.”

“What’ll you have, Aki?”

“I’m going for the seafood bowl.”

He pointed to the item at the top of the menu. It included raw and boiled whitebait but also chutoro and sakura shrimp. A heaping bowl of luxury.

The appetizer came out not even three minutes after we placed our orders: a dish of stewed pork and taro that melted on our tongues. While we were savoring this, a waiter brought out our rice bowls and miso soup.

Aki’s seafood bowl was very colorful, but my half-and-half wasn’t all white, either. It had yellow rolled eggs and green chopped scallions, too! I thought it put up a good fight.

Both types of whitebait caught the sunlight from outside and glittered. It was a beautiful sight.

I poured a little soy sauce into a dipping dish and tapped a wad of raw whitebait into it on the way to my mouth. It was nice and squishy, and it felt good against my tongue.

“Yum!” I said, savoring the fresh flavor.

On my next bite, I included a few scallions with the raw whitebait. After that, I had a brief affair with the boiled stuff, then settled on having both kinds at once. I was living wild and free!

I was especially pleased with my wasabi–soy sauce combo. I mixed wasabi into the soy sauce, then dunked in some raw whitefish. The flavor became shockingly rich, and the faint bitterness of the raw fish was lost in the tingling spice of the wasabi.

Ginger was also good, but the wasabi was better. I got carried away and added too much, and my nose started to sting as tears formed in my eyes.

As I recovered with the gentle warmth of the miso soup, Aki whispered, “You’re really something, Nao.”

My eyes still wet from the wasabi, I shot him a dubious look. He glanced away and smeared some wasabi on a gleaming red fish.

“You’re saving so much money,” he continued.

“I’m just getting paid for doing household chores.”

“But you’re working for it. They’re your earnings. That’s way better than me. I’m just leeching off Shuuya.”

Aki rarely brought Sanada up like this. Normally, he wouldn’t broach the subject himself, and if someone else did, he’d simply act unconcerned.

I knew what had brought about this change. He must have been thinking about Shuuya Sanada this whole time, about how his original was faring at school. I didn’t have to ask why; I was doing the same thing.

“I’m not that impressive,” I said. And before I knew it, the floodgates had opened. “I’m pathetic. I can’t keep my head up. Sunao’s going to school again, and I can’t even bring myself to congratulate her.”

“I’m the same,” Aki said, nodding. I could hear how much he meant it in his voice.

We each sipped at our tea, almost in sync. I felt like we were both at a loss for what to say and were looking for the answer in that greenish liquid. Or maybe we just wanted to wash the words back down our throats.

There were voices all around us, but it felt like the two of us were somewhere else, apart from them.

“I think I’ll get a job after high school,” Aki said.

Hands still on my cup, I gaped at him. I had no clue where this declaration had come from.

“You’re pretty bright, Nao. Are you gonna take an entrance exam?”

“I can’t do that.”

It wasn’t a matter of whether I could pass the exam. I truly couldn’t take one. You could search the whole of Japan, and you wouldn’t find a single college that accepted replicas. Going abroad wouldn’t help, either.

“If you go to college, I’ll try to get in, too.”

Aki’s flight of fancy soared on. I gritted my teeth, and a scallion stuck in the back let out a squeak.

“You can’t plan your future around something like that,” I said.

“I think going to the same college as your girlfriend is pretty typical.”

“…Replicas can’t go to college,” I said, but he didn’t bat an eye.

“You never know. Ryou managed it through junior high.”

There was a big difference between junior high, high school, and college. I wasn’t certain, but I had a feeling college was in a totally different league. I thought about saying as much, but I couldn’t. I didn’t want to.

I wanted to talk the way Aki was talking. I wanted to chat about tomorrow and beyond, about a future whose tail we’d yet to grasp, until both of us were out of words.

“Which college would be best?” I asked.

Aki smiled, seeing that I was finally on board. “University of Tokyo, maybe?”

“Just to say we took the test?”

“If we’re going that far, we might as well give it our all.”

I felt like it was probably a bit late for that.

But maybe it wasn’t. We weren’t eighteen yet. We were fresher than the whitebait in my bowl. Better late than never, as they say. Perhaps it was still too soon to give up. It certainly couldn’t hurt to believe.

“What about a backup choice?” I asked. “Some place in Shizuoka Prefecture, maybe?”

“You’re thinking small.”

“If you dream too big, you’ll be left up the creek without a paddle.”

“Good point, Nao. I assume you’d be majoring in literature, right?”

“That sounds fun. I’d get to study everything anew! I’d really—”

The more we talked about impossible futures, the heavier the weight I felt on my chest.

A month from now, a year or three, maybe a decade—what would I be thinking about?

Would I even be capable of thinking? Would Aki be there with me?

“Thanks for the delicious meal!”

We put our hands together in front of the bowls. Not a kernel of rice was left in either of them.

We settled the tab and left the shop. Aki paid, as promised. This made me feel a little awkward, but it also made me happy.

“Hey,” I said. “Do you mind if we go look at the water?”

“Sure.”

We passed the hot spring again, then headed toward the water’s edge. I took another look at the parking lot, unable to give up, but we never did find that heron’s nest.

We moved through the tidewater control forest and were met by the open blue of the sky and sea.

I ran a few steps and used the momentum to get up on the levee. Aki put one foot on the side and followed me easily. By the time he’d straightened back up, I’d turned and was walking along the top toward Yaizu. My first few steps were a little unsteady, but I spread my arms, and that helped me keep my balance.

One, two. One, two.

The coastline was nearly a mile long from end to end.

“Careful, Nao.”

Sunao and Ricchan had jumped off this levee on a dare when they were kids. But I had no plans to fall today.

“I’m fine,” I insisted.

Aki seemed a bit dubious, but he didn’t nag me any further.

In the distance, the cliffs were much higher and steeper. When I looked up, clouds were stretched across the sky, thinner than Saran Wrap. The sea was nearly indigo, but the waves turned white as they broke along the shore.

While I’d been holed up in the house, the seasons had continued their march toward winter. The sun was growing fainter and the days, shorter. Without me realizing it, the world had slipped into winter’s pocket.

I’d been dreaming of wearing mittens when winter began in earnest. I’d wanted to see my breath turn white and touch the snowflakes in a flurry with my hand. I’d wanted to eat warm pizza buns or even just regular meat buns.

As I lost myself in these visions, a gust came in off the sea and tried to snatch my feet out from under me.

“Whoa!”

It caught me off guard, and I stumbled a bit.

“Careful!” Aki said, reaching out to catch me.

His arms pulled me close as another gust hit us.

“Whoa! Wah! Augh!”

In each other’s arms, we fought together to stay put, spinning like the dancers in a windup box. After two turns, our efforts proved futile.

All too easily, our feet left the ground. For a moment, we floated. Every organ in our bodies rose up in the wrong direction. I heard a whooshing sound that made all the blood drain from my face, and my vision spun.

I felt a small blow to my face. Was that sand against my arms?

Sound slowly returned to the world. I could hear the surf, car engines, someone else’s breathing. In the distance, I heard a shrill cry—a kite, not a heron.

…I’d screwed my eyes shut on instinct, and now I slowly opened them.

My eyes, nose, and mouth were pressed tight against Aki’s chest. We’d fallen onto the beach in each other’s arms.

The heat where our bodies touched didn’t feel real. I was certain we must be flashing red, visible for miles.

Aki seemed to process the situation faster than I did, but he didn’t stand up or take his hands from around my back. The reason why was clear from the way his body was shaking.

“My heart’s about to explode,” he said.

It was quite the exaggeration, but I’d fallen with him, and I understood what he meant. My heart had been about to explode, too, right up until a second ago. Blood was pumping through my body like crazy, and all my organs were working in overdrive. I could feel cold sweat gushing from my pores, with no sign of stopping.

How had Sunao and Ricchan ever jumped off something so high? Was it because they were young? Or was nothing scary when you were with your best friend?

“Sorry,” I said.

“That wasn’t on purpose, right?”

Still in his embrace, I shook my head. He couldn’t see my face, but he could feel my hair move.

“Yeah, I figured.”

Aki sounded relieved. He’d had to ask, though. I had a prior offense on record, and he was still nervous.

His hand patted my back, soothing me. It felt gentle and warm. Pat pat, pat pat pat. He repeated the motion in a steady rhythm, as though he was calming a fussy baby.

We both remembered how much I’d cried on this same beach. That was only a week ago. But the truth was, I couldn’t believe a whole week had already passed.

“Aki, I…”

His short hair smelled like mint, just like mine—that shampoo from the hot spring that had made my eyes sting.

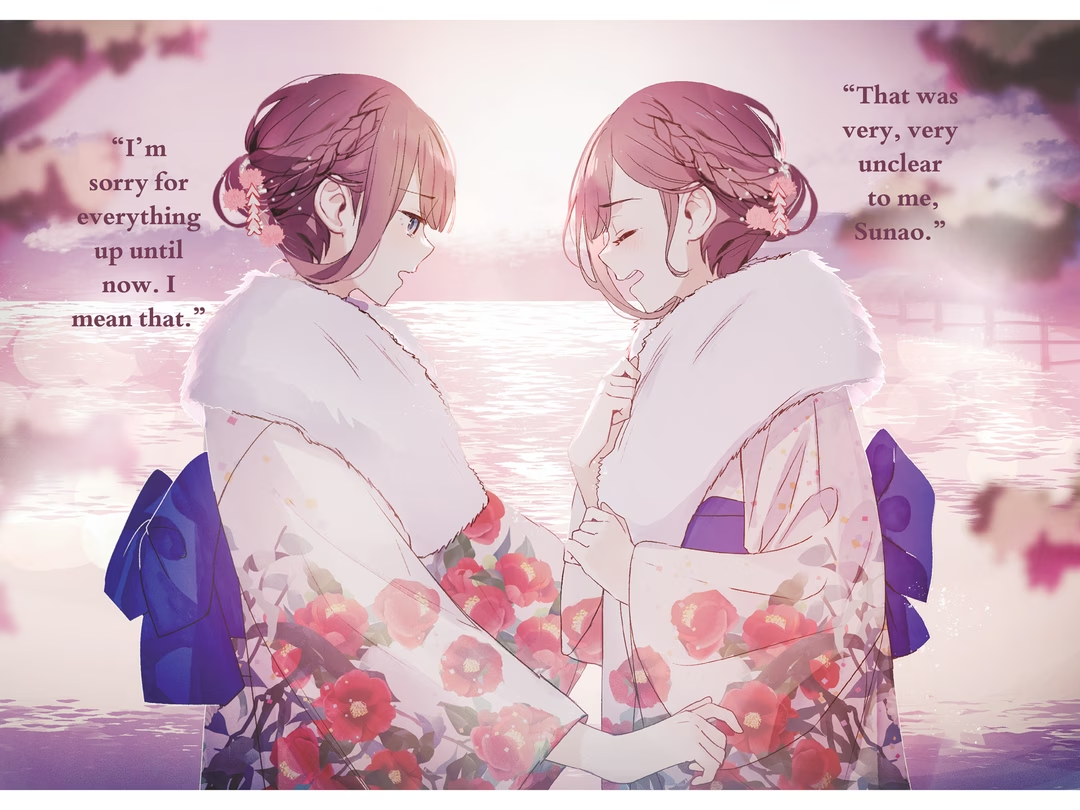

“I feel so lost.” Saying it out loud seemed to make the emotion real. “I miss Ryou. I miss going to school. I don’t know what Sunao’s thinking, and that makes it all worse.”

The loneliness I felt was very close to fear. Ryou’s loss had frightened me. Not being at school was scary. Not knowing what Sunao wanted was terrifying.

I wasn’t the original. Everything was scary to a replica.

“I’m pathetic, right?” I said, my voice turning nasal.

“Hardly. I feel the same way,” Aki admitted. “I’m just as lost. Just as scared.”

I nodded. I wasn’t the only one suffering, trapped under a dark cloud. The time Aki and I had spent with Ryou was too recent, too vivid to be banished into the realm of memories.

But Aki and Ricchan had gotten their feet under them, whereas I’d failed. I’d needed them to drag me out into the sunlight again.

When I closed my eyes, I saw that stage in the gym. Ryou was there, smiling through her tears. I’d only just found her—and now she was gone, her memory the only thing left behind.

And I couldn’t separate the sight of her disappearing from my own fate.

“I don’t want to vanish like she did,” Aki said. “That’s too scary.”

His arms tightened around me, insistent, as though they would never let me go.

I was sure Sunao and Sanada couldn’t begin to imagine how we felt, no matter how hard they tried. They could never understand a fear this intense, this helpless.

We were two replicas, wavering on the edge. Standing atop the levee or lost out at sea—nothing could compare. Our entire realities could be rewritten by a single whim, and it scared us silly.

“I’m terrified,” said Aki.

“Yeah. So am I.”

Words had power. Saying something out loud meant it couldn’t be taken back. But people couldn’t survive without sharing their fears.

I pushed my head against Aki’s chest as hard as I could. I was scared, and so was he, and we were sharing that pain. We were going halfsies on this uncontainable torment, trying to stop each other from shaking too hard and toppling this tower we’d made from words.

Just then, we heard a shrill noise from overhead.

Aki’s shoulders jumped. Surprised, I turned over and saw a passing stranger whistling at us.

“Ah, youth!” he said, then gave us a thumbs-up.

We didn’t have nearly enough life experience to simply nod back.

He cheerily wandered off, and I watched him go. Then I heard Aki whisper into my ear, “That’s the dude from the sauna.”

“You’re kidding?!”

“We watched Hirunandesu! together. You know, the variety show that talks about food and fashion and so on. He said he wanted to try Taiwanese castella.”

I couldn’t have cared less.

“…Snrk. Heh-heh. Ah-ha-ha!”

I couldn’t stop myself and burst out laughing. Aki joined me, and I thumped his chest.

What the heck is Taiwanese castella?

Once our laughter died down, I wiped my tears and finally sat up. We got a good look at our sorry condition, then laughed again.

“We just got out of the hot spring, and now we’re covered in sand,” I said.

“Seems so.”

What a shame. Our trip to the bath wound up pointless.

But I knew that wasn’t true. The hot water and seafood had warmed me to my core—enough that I was sweating. No matter how cold it was outside, I now wore an invisible veil that I was sure would prevent me from freezing.

Aki brushed the sand off his clothes and skin, then stretched.

“I just had a great idea,” he said.

“Oh?”

“Let’s take a school trip. Just the two of us.”

My eyes sparkled.

On November 17, the second-years would embark on their school trip—their destination, Kyoto. But if Sunao and Sanada were going, then we would have to stay home. I’d thought no further on the subject, but Aki had shown me up. How had he managed to think of something so delightful?

“A three-day, two-night trip?” I asked.

My voice bounced. This was a vital detail. The originals’ trip would last from the seventeenth to the nineteenth.

Aki started to nod, then stopped and scratched his cheek. I’d long since worked out that this gesture meant he was uncertain.

“I hadn’t thought that far ahead,” he admitted. “Staying somewhere…might be too much.”

“Why? I’d love to!” Perhaps I’d sounded a bit too eager. Fidgeting, I tried again. “I want to take a trip with you, Aki. And stay the night! Is that so wrong?”

Nervous, I looked up at him through my lashes. Was I the only one excited about this idea?

If we were calling it a “school trip,” we couldn’t come back the same day. We had to stay the night somewhere and enjoy ourselves without worrying about the time.

“Well, I’m not saying it’s wrong, just…” He hesitated, so I leaned in.

“Then can we?”

“…Okay.”

Yes!

I managed to prevent myself from jumping for joy, but just barely.

“In that case, I have a suggestion,” I said.

“Oh? Were you thinking Hawaii?”

Aki was full of jokes today. But I didn’t want to go abroad or even to Okinawa or Hokkaido. I didn’t want to go to Kyoto, either.

I had just one destination in mind.

“The Netherworld Ranch.”

The morning of the school trip, we assembled at seven thirty AM near the taxi stands at the north side of Shizuoka Station.

I’d spent the previous night poring over the trip guide booklet as I packed a gray Boston bag and a navy shoulder bag bought just for this occasion. As I’d put each necessity into the bag, I’d checked off a box in the booklet.

Despite looking at my weather app, I still wasn’t sure just how chilly Kyoto would be. My father swore the place was hellishly cold, so I heeded his warnings and brought a fall coat and some thicker undershirts.

During the summer, I always longed for winter, but when it finally arrived, I missed the warm weather. By then, my brain had already forgotten how much I’d suffered in the heat only a few months earlier.

My oversized bags were full of pockets, both inside and out. Midway through packing, I was already confused about where I’d stashed the tissues, bandages, or the first aid kit. I went to bed an hour early but fell asleep at roughly the same time.

My alarm went off at five thirty AM, but my eyes were already open.

Mom was shocked I’d managed to wake up on my own.

“So you can do it, if you try!” she said as I washed my face. It was a rather dubious compliment. Still, I almost never woke up before she left, so it felt novel.

“Did the results come in yet?” she asked.

“No. They might come in while I’m away.”

Mom nodded. She was behind me at the sink, tapping a powder puff against her cheeks. She’d paid for it, so she was eager to hear how I’d done.

I’d bought some stuffed bread at the convenience store the night before and made quick work of it before carefully making myself presentable. Somehow, I always had nasty bedhead on days like this, and I was irritably forced to iron out the kinks. The time went by shockingly fast, and I was still glaring at the mirror an hour before we were supposed to meet up.

It was a ten-minute walk from our house to the nearest train stop, Mochimune Station. I hadn’t run into any delays yet, but I planned to leave early, just to be safe.

I went upstairs briefly and called Nao out. I blinked once, and there she was, dressed just like I was. Her hair was already straightened, and I was momentarily jealous.

“I’m about to leave.”

“Have fun, Sunao.”

Unaware of my thoughts, Nao smiled for the first time in a while. I almost got lost staring at her and wound up leaving the room in an unnecessary huff. I bumped both bags against the wall and swore under my breath.

I hit the bathroom, said good-bye to my parents, then left.

I hadn’t planned on calling Nao out while I was on the school trip. My parents would be gone during the day, but they’d come home after work. No matter how quiet Nao was, she had to eat and go to the bathroom, and that made noise.

But Nao said she and Aki were going on a trip together. All I knew was that they were headed to Fujinomiya.

On my way to the station, I got to thinking. What kind of high school girl goes on a weekend trip with her boyfriend?

I imagined them, two teenagers out on their own. Who knew what might happen? But when Nao told me about her plans, she looked delighted. I saw no trace of the gloom that had been hovering over her all week. I felt like a hardheaded grown-up worrying and couldn’t bring myself to say anything.

Come to think of it, the last time I’d so much as held a boy’s hand was in fourth grade, on a field trip. I’d never really wanted a boyfriend, but knowing Nao was having a typical high school romance definitely got under my skin a little.

I didn’t know how far they’d gone, but I had to hope Aki kept things age appropriate and controlled himself.

As I offered up a prayer that I was merely overthinking things, a shockingly cold gust of wind brushed against my cheeks and neck. It was already the height of winter.

I’d been ignoring the seasons so far, but whether I paid attention or not, summer followed spring, and fall gave way to winter. That was all the seasons had ever been to me.

But as I looked up now, the sky seemed so distant. I was blown away by the resilience of weeds growing through the cracks in the asphalt, and I heard the cry of a healthy baby from a house that had been a construction site the last time I was paying attention.

If I looked closely, the world was constantly changing hues and shades.

The leaves on the wisteria near Mochimune Station had certainly changed their colors. I bought some hot tea from the vending machine outside the gates. I’d been worried I was dawdling, but I still had plenty of time before the next train.

The platform was dominated by adults in suits on their way to work, but I also spotted a little boy wearing a cute private school uniform. I glanced around but didn’t see anyone else dressed like me.

Very few students were commuting from Mochimune Station. I knew that, but it still made me nervous.

At times like this, I’d start to wonder if I’d accidentally come an hour early or if I’d shown up on the wrong day. Was I the only one who got scared like that?

I double-checked the guide booklet and my phone, making sure I had the right day and time. Then an announcement echoed through the station. Train arriving on line three. Stay behind the yellow line.

Queues started forming, and I stood at the end of one, squinting at the windows as the train raced by. I scanned them for anyone wearing my school’s uniform, but I didn’t have any luck.

The doors opened, and I gingerly stepped in. Once inside, I was relieved to find several familiar faces.

Most of the seats were filled, but it was only a seven-minute ride from here to Shizuoka Station. The doors closed with a hiss, and the train began to pull out. I set my Boston bag at my feet and grabbed a strap, unobtrusively scoping out the rest of the interior.

My eyes easily found the other Surusei uniforms, like they were soaked in some kind of special paint. They were mostly in groups of two or three, as if they’d arranged to meet up along the way.

Their voices were full of excitement for the trip ahead and bounced off the low ceiling, vibrating my eardrums.

“I’ve never been to Kyoto.”

“I can’t wait!”

“Do you know what you’ll get for souvenirs?”

“I brought my Switch.”

“I’m gonna ask her out while we’re there!”

Their chatter was indistinguishable from that of little kids on a big day out. A wave of giddiness passed over my head, then dissipated. My hand tightened on the strap.

Glaring at the view outside, I told myself it would be okay. As sunlight streamed through the windows and pierced the back of my eyes, we left Abekawa and arrived at Shizuoka Station.

I checked my phone. It was seven thirty on the dot.

The doors opened, and droves of people rushed out—way more than at Abekawa. The wave pushed me along with it, and I chased the people in matching uniforms toward the north gates.

The second-years were already forming ranks near the taxi stands. These were nothing like the vague lines at Mochimune; instead, we were arranged in alternating rows of boys and girls, split by classes, in order by seat number.

We were lined up just like at a school assembly, but everything felt somehow less formal. Everyone was chatting with those nearby, and that alone kept the volume fairly high.

Sunao Aikawa of Class 2-1 had a front row seat—no need to worm my way through the rows or to worry about my baggage. I just sat right down in the gap at the front.

If there was an Aiuchi, maybe I’d have been second—but my whole life, I’d never made it any farther down a list. I had no talents or hobbies—this was the one thing I was always first at, albeit through no effort of my own. It was hardly an achievement, however, so no one ever offered me any congratulations.

But being first in line carried responsibilities. You had to work. Cleaning rosters, classroom duties, answering questions in class—everything started with the person in seat number one. Occasionally, I’d have to play rock-paper-scissors with the person in the last seat. Names at the beginning or the end—those starting with A or with Wa—were at a marked disadvantage when it came to school activities.

Lots of girls were crouching in place like old-timey delinquents, not wanting to dirty their skirts. But I couldn’t be bothered and sat on the ground, hugging my knees. I didn’t want the back of my legs getting gross and sweaty.

The teachers in charge started calling out to everyone, asking for quiet. Then the class reps got up and approached the front of the lines.

Satou popped up in front of me, and our eyes met.

“Morning, Aikawa. How’s it going?”

“Meh.”

“Glad to hear it!”

I was pretty sure she was the only class rep who’d respond to “meh” positively.

“Okay, numbers!”

I inhaled as she spoke, then called out, “One!” I put my abs into it, trying to project.

Following me, other students numbered off like dominoes. Two, three, four, and so on. I let my shoulders relax, relieved the moment had passed.

Satou finished taking attendance. In the meantime, Ootsuka had gone around checking our health. Both reported back to our homeroom teacher.

Once all classes were accounted for, the principal stepped up to make a speech. Passersby gave us fond looks, some of them rather envious. But none of them stopped to watch.

The principal beamed at us, reporting that no one had missed the big day, and that this was the result of our daily diligence. The best thing about Surusei’s principal was that he knew how to keep things brief. I couldn’t think of anything bad to say about the man; I knew next to nothing about him beyond what we saw in these two- or three-minute formalities.

When he was done, the head teacher for our year rattled off a list of precautions. Then they had us stand up, starting with Class 5. We headed toward the Shinkansen platform.

Our seating assignments matched our class seats, and we’d be in the same car and seat on the way back, which kept things simple. This made it impossible to group up with friends, but that was likely the intent—teachers hated problems cropping up en route.

I got my Boston bag up on the overhead rack, and soon the Hikari train pulled out of Shizuoka, bound for Osaka Station. A teacher was already yelling at students for goofing around and bothering the other passengers.

Absently watching the scenery flow past the window, I thought: Our school trip has finally begun.

Two hours after Sunao left, I was standing on the platform at Mochimune Station.

By now, her parents were at work, and there was no risk of other students spotting me.

The air was chilly, but it was fine weather for a school trip. Then again, you could never trust the weather in the mountains. I’d made sure to keep a folding umbrella in the rucksack on my back.

I bought a ticket to Fujinomiya. It cost 990 yen for a one-way trip. It was by far the most expensive train ticket I’d ever purchased, and after stepping through the gates, I tucked it into the inner pocket of my rucksack, so as not to lose it.

The platform was fairly empty as a train pulled in from Yaizu. I braced myself and gazed at the cars as they came to a stop.