Fourth Era: Seizing the Imperial Capital

Prologue: Victorious Warriors Win First and Then Go to War

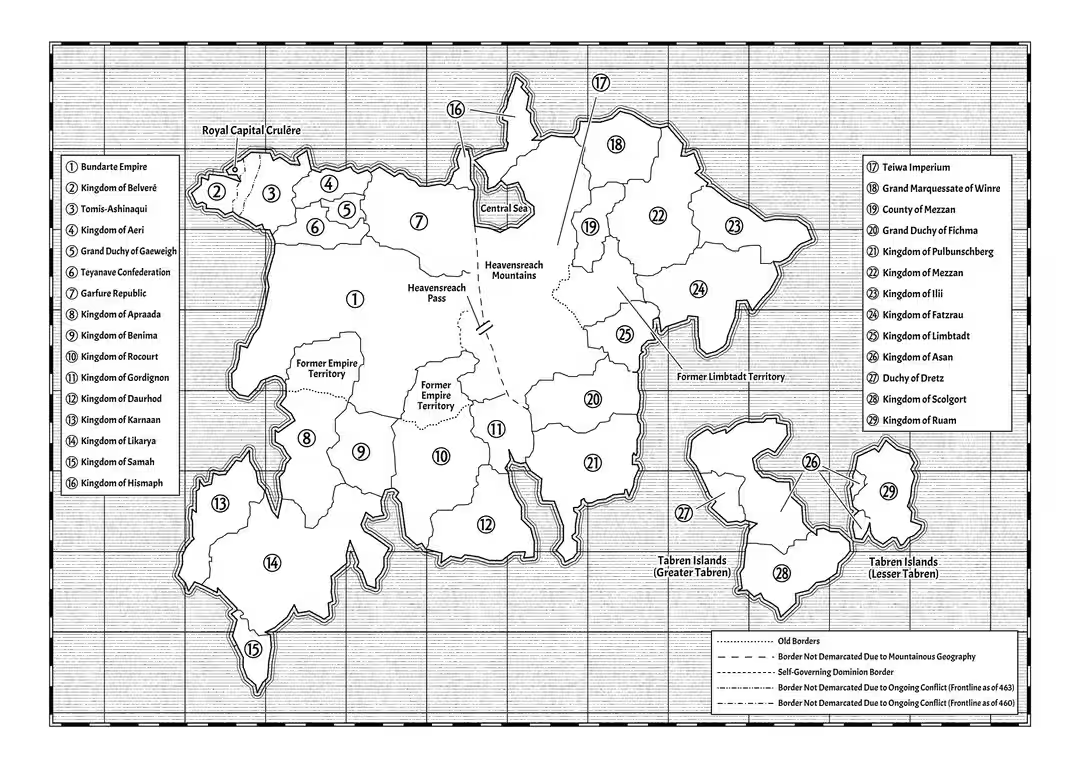

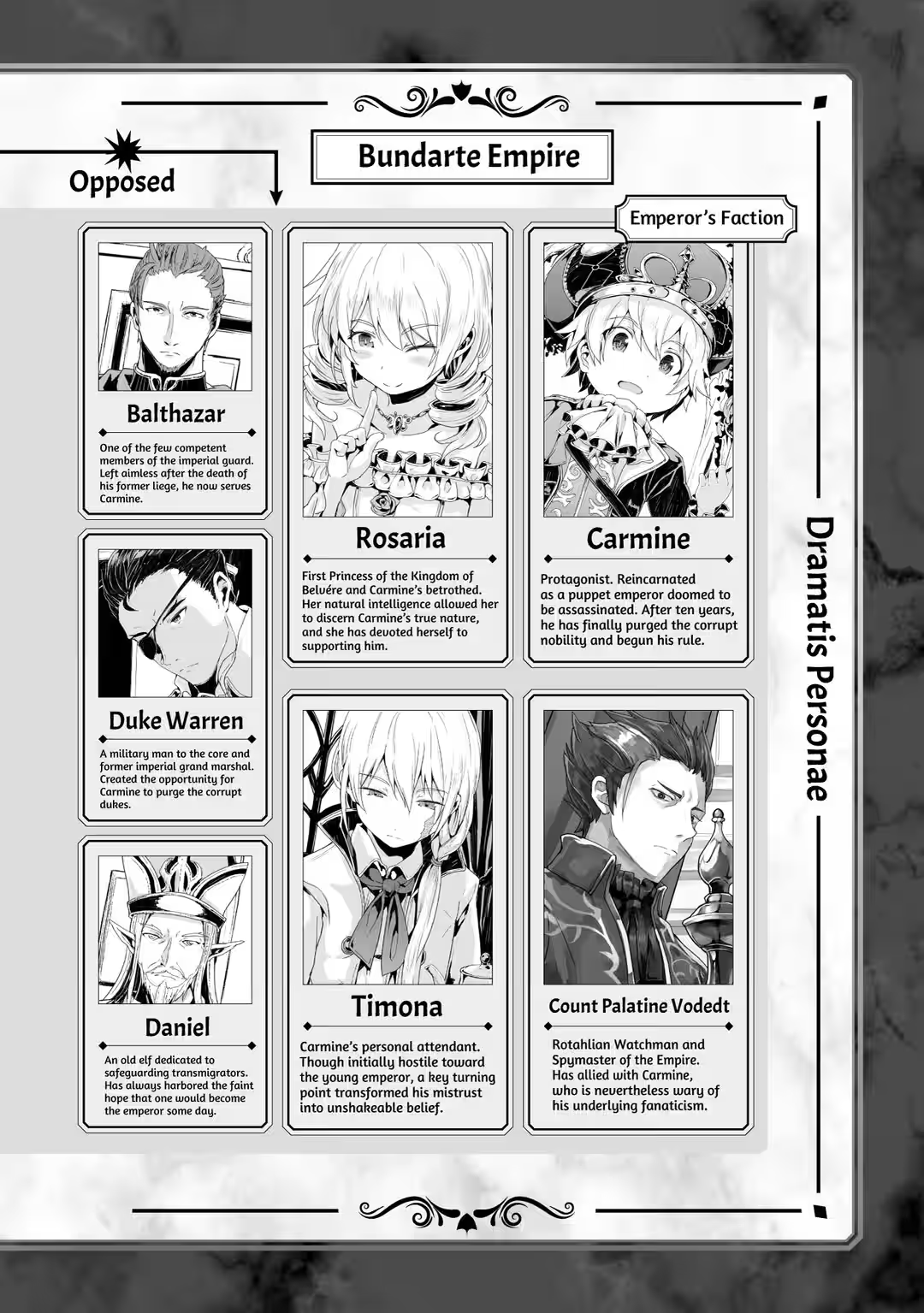

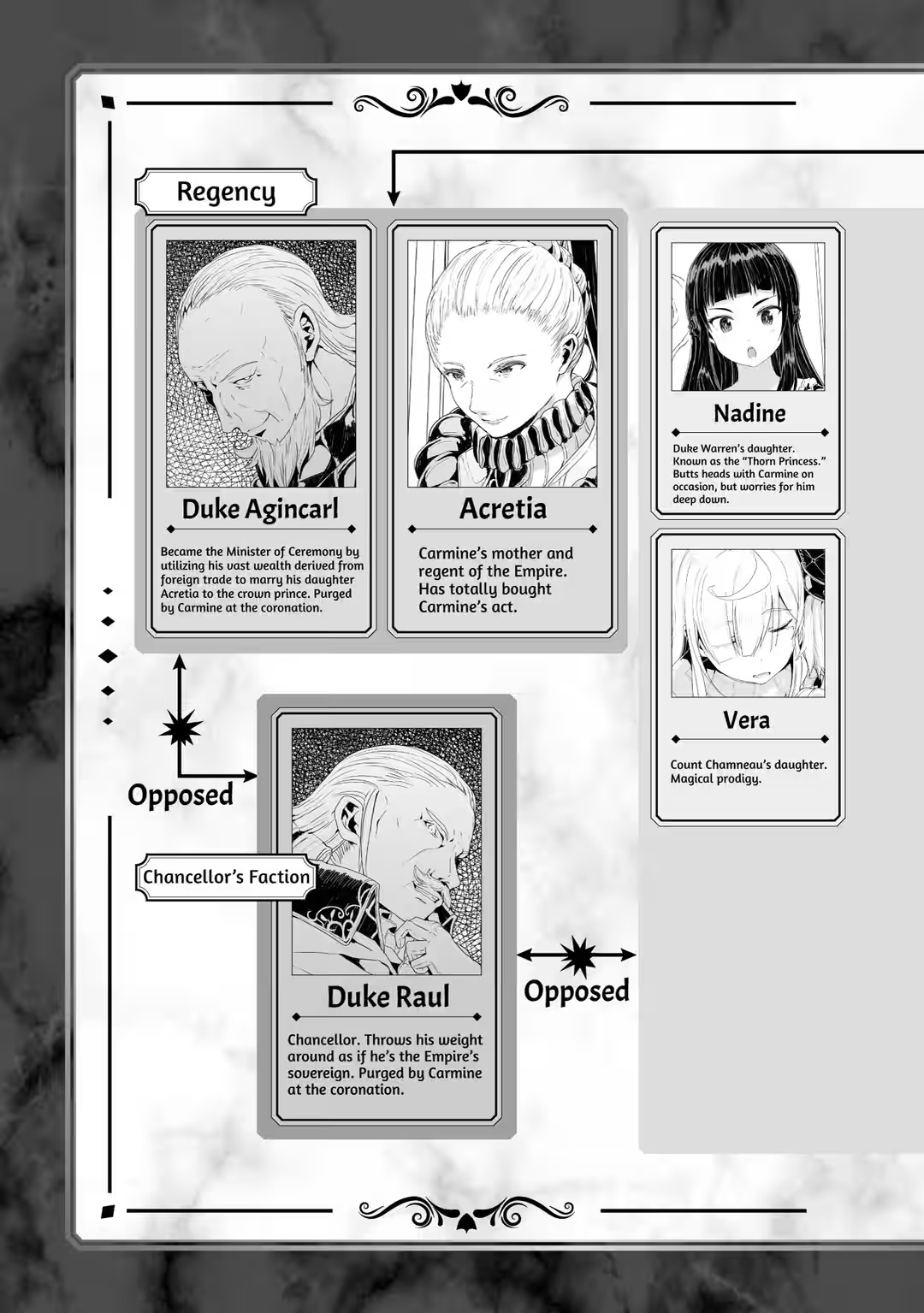

The Bundarte Empire. A nation in decline thanks to its chief political factions’ selfish misrule. Headed by the Chancellor (Duke Raul) and the Minister of Ceremony (Duke Agincarl), they spend all their time engaged in petty conflict rather than productive administration. It was in this nation that I was reborn as Carmine, emperor from my first day in this new world.

As a mere figurehead, the threat of assassination waited for me around every corner. In order to survive, I acted the part of a convenient puppet for the nobility, pretending to be a fool so that they need not be wary of me. All the while, I gathered allies in secret, waiting for my chance to seize back power.

And finally, that chance arrived. Panicked by Duke Warren’s insurrection, the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony held a snap coronation for me. While their guards were down, I struck, purging them with my own hands, and declared to all that the nation was once again under direct imperial rule.

Yet make no mistake: The sum of all my efforts has done naught more than balance the scale. I have finally reached the starting line. The true battle is just beginning.

Even with the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony eliminated, their factions are still in play. Their sons, too, must have a bone to pick with me over their fathers’ executions. And by declaring direct imperial rule, I have opened myself up to dissent from the nobility.

The Empire faces a long litany of problems courtesy of the nobility, who have allowed the government to putrefy for so long. Our neighbors pull strings in the shadows, intent on the Empire’s continued decline. Domestically, our nobility are all but certain to revolt.

Each of these issues requires my attention; each of these issues needs to be resolved.

Most importantly of all, I have spent my whole life pretending to be a fool. I need to dispel that image and unify the Empire before it is too late—and I have little in the way of military might to count on. If I lose this opening conflict, I will either return to being a puppet, or be killed and go down in history as an incompetent ruler.

No, that would be the preferable outcome. If the worst comes to pass, the Empire itself could cease to be.

Until this point, I’ve fought my battles with only a handful of lives on the line. But now, the existence of a nation rests on my shoulders.

I will not shirk from using every method at my disposal. All for the sake of victory.

The Audience

It had been three days since the coronation. But although the imperial capital was still in lockdown, completely halting the flow of humanity was an impossible task—the city’s population was simply too large. There was no hope of keeping a lid on my execution of the Dukes and arrest of the nobility either, of course.

Rather than waste intelligence agents on that futile endeavor, I put them to work gathering the information I sorely needed right now. They departed for the duchies of Raul and Agincarl—now bereft of their principal governors—to spy on the movements of their noble houses.

Assuming no obstructions, news of the coronation must have reached the duchies by now. They’d be mustering armies before I could blink.

The day after the coronation, Count Chamneau had requested permission to make public the news of the purge. I knew we wouldn’t be able to conceal it anyway, and it seemed he could make good use of the opportunity, so I acceded.

Upon receiving my permission, Count Chamneau apparently informed the commanders of the Chancellor’s faction and regency detachments within his army of the events of the coronation. He also told them that much of the nobility had escaped and were suspected to be hiding within the army—a lie—and that they faced a possible attack—also a lie—by the emperor’s personal army and Duke Warren’s army, which had returned to the fold.

The majority of the nobility’s commanding officers within Count Chamneau’s army were rear vassals—essentially the lowest rung of nobility, or near enough. With their lack of insight into the truth of the events, it seemed they’d chosen to return to their holdings first and ask questions later. Better that than remain in the imperial capital surrounded by enemies, in their eyes.

This was how Count Chamneau essentially defanged the coalition army. I was grateful—I’d considered the option of disarming them, but this method was better for my purposes. Having potential enemies hanging around the city who would no doubt resist attempts to disarm them would only tie up my limited and precious pool of military resources.

Okay, so maybe those “precious military resources” were untrustworthy mercenaries. Beggars couldn’t be choosers, all right?

Above all, the outcome I most wanted to avoid was the nobility’s armies trying to recover their respective lords and ladies by force. I’d take them returning to their holdings over running amok any day. After all, having the nobility in captivity meant I’d basically muzzled their subordinates.

In the meantime, Duke Warren, who’d received my personal letter, showed no sign of any hostile intentions. He’d already sent me a written oath stating that he would return to the Empire’s service and pledge his loyalty to the emperor. In fact, he would be arriving in person to the imperial demesne today for an audience with me, shared with Count Chamneau and Fabio.

In truth, I’d hoped to have him come earlier, but that had proven impossible. Duke Warren and Count Chamneau’s armies had been hostile mere days ago—even if the duke had agreed, his vassals would not have allowed their lord to simply walk into a possible death trap.

To solve that problem, we’d moved both armies out of the way. Count Chamneau’s, which was essentially just an amalgamation of mercenary bands now, had moved to the western side of the imperial capital, while Duke Warren and Fabio’s forces had set up camp to the south.

Not-so-coincidentally, the city’s western and southern sides were defensively quite sound, owing to its layout and construction. Even with the ceasefire (did it count as a ceasefire if no fighting had actually happened?) we couldn’t exactly let an army or two hang out on the city’s eastern side, given its lack of a wall.

***

Duke Warren, accompanied by a guard escort, passed under the city’s gates to the wild enthusiasm of the crowds.

Part of this was because I’d emphasized his loyalty during my public address, but it was mostly because he’d been very popular among the people during his time as imperial grand marshal. No surprises there—commanders who won a lot were popular no matter the day and age.

Soon, I would be granting an audience to Duke Warren, Count Chamneau, and Fabio. Rather than use the palace where my coronation had been held, we’d converted a part of the sixth emperor’s palace for social gatherings as a temporary audience chamber. The coronation palace was too deep into the imperial demesne to be convenient.

More relevantly, it was still being, ah, cleaned. A certain someone had spilled a good deal of blood in the process of subduing the coronation’s attendees. What was more, most of the imperial demesne’s servants were in the pockets of the regency or Chancellor’s faction, meaning we had to be wary about what work we entrusted them with. Long story short, we were suffering a manpower deficit.

Before long, Duke Warren and the others arrived at the slapdash audience chamber. Incidentally, the throne I sat on had belonged to Edward II, the fourth emperor—we’d pulled it out of storage and dusted it off. Despite it being the plainest of the thrones in terms of ornamentation, it had a refined elegance to it. Plus, it was very comfy.

Atop my throne, which rested atop a slightly elevated platform, I waited for the three men to kneel. Before you go calling me pompous—admittedly I was quite literally looking down at them—the act of me sitting on the throne ahead of time and waiting was the greatest respect I could show them in my capacity as the emperor.

When I’d been a puppet, everyone had made light of me. Naturally, that had meant I couldn’t perform the etiquette befitting of my station. Now that I was properly in power, I fully intended to act like a self-important emperor—to protect myself, if nothing else. This was not the time or the place for overfamiliarity; sometimes, being too nice could breed contempt.

All of which was to say that from here on out, I needed to play the part of a strong emperor.

Daniel de Piers announced the trio’s names and titles. Ordinarily, that would be the Chancellor’s role, but the position had experienced a sudden vacancy. Official procedure called for a member of the clergy to stand in as substitute herald.

“Your arrival is most welcome,” I declared once Daniel was finished. “Raise your heads.”

Incidentally, Duke Warren had come into the audience chamber accompanied by another nobleman acting as his guard, but formality demanded we treat him as invisible. Well, more accurately, he was deemed an object—a weapon of the duke’s—in the eyes of official procedure, and forbidden from speaking. Likewise, the imperial guards who were present to ensure my safety couldn’t speak a word either. Stuffy and suffocating, I know, but that was formality for you.

“Duke Warren,” I began. “We thank you for heeding our words. If you had not mustered your army, we would not have been able to enact our own plan. You have done well, and we consider you a paragon of imperial nobility—a model on which posterity shall rely.”

“Your Majesty is too kind. Your words bring me greater joy than I can express.”

From Duke Warren’s point of view, the purge had been abrupt and unexpected, carried out by a child he’d thought a puppet. No doubt he was still gauging my character, and it would take more than the events of the past few days for him to fully trust me. He’d come to the imperial demesne regardless because I’d publicly refuted the claim that he was a traitor, as well as because of the handwritten letter I’d bid Nadine to deliver to him.

“Once you have delivered just punishment to the Empire’s traitors, we shall reward you handsomely for your distinguished service,” I proclaimed.

The traitors I was talking about were the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony’s sons, who would be mobilizing their armies as soon as they heard the news of their fathers’ demise. In the very unlikely event that they didn’t revolt...well, I’d still crush them anyway. Houses Raul and Agincarl held too much power.

“As Your Majesty’s sword and shield, I swear that I shall bring the disloyal to justice.”

“Well said, Duke Warren! We could not entrust the task to a more worthy man. Henceforth, Emperor Carmine of the Bundarte Empire appoints you as imperial grand marshal!”

Not to burst anyone’s bubble, but we were just going through the motions. I had included all of this and more in my letter.

Me gaining the opportunity to enact my plans because of Duke Warren’s insurrection; my promise to the duke that I would handle the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony myself and subsequent request to refrain from engaging Count Chamneau’s army; another request to return to the imperial fold after I’d seized control of the capital, and of course, his reappointment to the rank of imperial grand marshal and the promise of further rewards after the civil war was concluded—all of this exchange had been decided in advance.

“You are known as a great commander, Duke, and famed for your ability. Deliver the Empire the stability it needs.”

“Yes, Your Majesty!”

I nodded emphatically, then turned my gaze to Count Chamneau. “Count Chamneau. Your efforts have produced magnificent results.”

“Your Majesty honors me in excess. I am undeserving.”

“Henceforth, Emperor Carmine of the Bundarte Empire appoints you as imperial grand marshal. Continue to avail the Empire with your capable talents.”

Naturally, my exchange with Count Chamneau had been prearranged too. I’d decided to appoint both of them as grand marshals so that power didn’t concentrate too much around one or the other, but given the scale of the Empire, I kind of wanted more. Meh, I’d sort that out after we’d dealt with our domestic instability.

“My deepest gratitude,” Count Chamneau replied. “I hereby swear that Your Majesty’s—and the Empire’s—enemies shall fall by my blade.”

“Mmm. Regarding your daughter, Count—she has already been freed. Consult Count Palatine Vodedt for her whereabouts afterward.”

There was a moment of silence before Count Chamneau replied, “Yes, Your Majesty.”

I’d freed the count’s daughter, Vera-Sylvie, on the day of my coronation. My judgment was that she needed a good deal of peace and quiet, accompanied by healthy doses of rehabilitation and medical supervision. You couldn’t just lock people up for years on end and expect them to come out okay, after all. We might’ve ensured that her conditions had improved recently, sure, but she’d lacked proper food and exercise for too long, and it would be some time before she could be called healthy again.

Still, if Count Chamneau and Vera-Sylvie wanted it, I personally thought it would be fine to let her return to their holdings. The imperial demesne’s medical faculties wouldn’t be back to full functionality for a while. Why, you ask? Well, probability pointed to it being the fault of an imperial medical officer who had carried out the previous emperor’s assassination. Count Palatine Vodedt was currently running a very thorough inquiry. For the time being, Vera-Sylvie’s care was being handled by a certain Storyteller and elf who was apparently well-versed in medicine.

Finally, we came to Fabio. Now that I was thinking about it, this was the first time we’d be talking in a formal setting.

“Fabio. Our loyal vassal. You have again contributed greatly to our cause. Your loyalty and devotion—unwavering for so long—must be rewarded.”

My words were more for Duke Warren and Count Chamneau than they were for Fabio. Of the trio, his army had been the smallest, and as a nobleman, his rank was the lowest. For me to nonetheless give him a greater reward than the duke and count, I needed to let them know it was because he’d been in my service for far longer.

“I am unbefitting of such kind words, Your Majesty.”

Of course, phrasing it like that made it sound contradictory, because officially, Duke Warren had pledged loyalty to me a long time ago as well. To explain, I’d have to get into some political semantics.

Take Count Chamneau as an example. He only pledged fealty to me recently, having not done so beforehand. From observing this example alone, one could interpret the phrase “swore loyalty” as “hadn’t sworn loyalty beforehand.”

Then we got to Duke Warren, who had helmed an insurrection “for the sake of the emperor.” If you interpreted his oath of fealty to me now as him not having sworn loyalty to me before (i.e., when he mustered his army), it would technically make his “insurrection for the sake of the emperor” a lie. Thus, to smooth everything over, the official state of matters was that Duke Warren had sworn loyalty to me a long time ago.

Honestly, there wasn’t a single soul in the room who would drag us up over such petty semantics. However, the faction nobility absolutely would, and we’d probably be releasing most of them soon enough. I couldn’t have them all killed—if I tried, every individual in the Empire with a drop of blue blood and institutional power would turn against me and have me ousted before I could say the words “murderous despot.”

Among the released nobles, some would go on to do good work and reestablish a position for themselves in central politics. I couldn’t stop that from happening. If I broke the core principle of meritocracy—punishments and rewards doled out fairly and accordingly—then no one would follow me.

Hence why we had to cover our tracks like this over the question of Duke Warren’s loyalty. It was a pain, but nitpicking and politics had gone hand in hand in my previous world too, so I’d just have to bite the bullet.

But I digress. Back to the subject of Fabio’s reward.

I accepted a sheet of parchment from Timona, who stood to my side. It was a formal document bearing the emperor’s signature.

“His Majesty, the Emperor Carmine of the Bundarte Empire, declares thusly,” I proclaimed. “Let it be known that the event known as the ‘Three Houses Coup’ was, in truth, an unjust persecution perpetrated by the former Duke Raul and the former Duke Agincarl. Consequently, the margravial house of Ramitead, the margravial house of Agincarl d’Decci, and the comital house of Veria, all of imperial nobility, are exonerated of all relevant crimes, and all effort shall be made to restore their impugned honor. Furthermore, the Empire recognizes the restoration of the margravial house of Ramitead, and the title of Marquess Ramitead shall be conferred upon the individual previously known as Fabio-Deneaux le Vodedt.”

Fabio bowed his head, tears streaming from his eyes. “I...cannot express the depths of my gratitude, Your Majesty. To finally be able to clear my family’s name...”

“Our proclamation shall be distributed among the public as an imperial edict,” I elaborated. “You have done well to endure until this day. Henceforth, you may give your name as Fabio de Ramitead-Denouet.”

He laughed. It sounded happy.

While this was undoubtedly a reward for him, it also benefited me. The benefit of granting one of my closest allies peerage and power was obvious, but it might also lure out any survivors of houses Agincarl d’Decci and Veria who might’ve gone into hiding like Fabio. I’d have a good chance of making new allies out of them, as well as leveraging their existence to further attack the legacies of the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony.

“Finally, Duke Warren.”

There was a brief pause before he replied, “Yes, Your Majesty.” There was the subtlest of confused notes in his voice; he must’ve not expected me to address him again.

“We have heard that you fought with our father on the battlefield. Is this true?”

“It is, Your Majesty. His Highness was gracious enough to consider me, in his words, a friend.”

“We do not know our father. If you would, would you tell us of him? The Empire’s current strife leaves us with little time, but we can spare some, after this audience. We wish to hear tales of our father’s conduct upon the battlefield.”

Duke Warren’s eyes widened. When he spoke, it was as if he were struggling to hold back some surging emotion. “If... If only His Highness could have heard Your Majesty’s words,” he said. “How overjoyed would he have been. Of course, Your Majesty. The honor would be mine.”

Thus, the first ever audience I had granted as the emperor concluded with a brief trickle of tears streaming down Duke Warren’s cheek.

Interlude: A Silver Right Arm, a Copper Left

After the conclusion of the emperor’s audience, his vassals—Duke Warren excepted—vacated the audience chamber. Count Chamneau departed with Count Palatine Vodedt, to be reunited with the daughter he hadn’t seen in over a decade.

As for Fabio de Ramitead-Denouet, formerly Fabio-Deneaux le Vodedt, formerly Fabio Denouet, he was eager to inform his house’s vassals—who had accompanied him to the capital—of the good news. The restoration of House Ramitead and its honor that had been stained by the Three Houses Coup had been their dearest wish since its downfall.

Nevertheless, Fabio encountered a sight so rare he had to stop in his tracks.

“Shouldn’t you be by His Majesty’s side?” he asked good-naturedly.

His friend, who was as expressionless as ever, replied, “There is no need for me to hear the memories of Crown Prince Jean.” Timona le Nain, Emperor Carmine’s personal attendant, set off at a walk, making a gesture for Fabio to follow.

Until now, Timona had been one of the emperor’s few trusted confidants and guards. However, since the coronation, Carmine had gained the protection of the imperial guard, including one Balthazar Chevillard. Given this, retaining Timona as a guard would be akin to declaring his mistrust of them, which was why he’d relinquished Timona’s services from his security detail, and why Timona had exited the audience chamber with Fabio and the rest of them.

Fabio, walking at pace by Timona’s side, shrugged. “Still, His Majesty put on a pretty good performance, don’t you think? I had a number of chances to learn what Duke Warren was like on the way to the capital—he’s a military man down to the core. I can’t imagine anything would make him happier than getting the chance to talk about the crown prince he loved and respected so much with his son.”

Almost every topic Carmine had raised in the audience chamber had been prearranged. Fabio had stopped to follow after Timona after achieving the long-cherished wish of House Ramitead, and was so unconcerned now despite the tears he’d shed earlier, because he’d known about it all beforehand—and so had his house’s vassals.

However, from Duke Warren’s reaction, Fabio suspected that Carmine hadn’t informed him that he would be asking about Crown Prince Jean. This suspicion was, in fact, on the mark. A man like Duke Warren would hardly have been moved to tears otherwise.

“His Majesty has an excellent read on the duke’s personality,” Fabio remarked, “to ask that even though he actually cares quite little about Crown Prince Jean.”

In Fabio’s eyes, Carmine had no admiration for his predecessors whatsoever. Even when being regaled with tales of the great Emperor Paterfamilias, Cardinal—the first emperor—he would feign reverence, but in truth would feel no childlike adoration at all. He held no ambition to assume the mantle of his venerated ancestors; he considered himself to be himself, and others to be “other.” Nothing more, nothing less. Among all the people Fabio knew, he considered the emperor to be the furthest from the word “childlike.”

“His Majesty...does not have much interest in the legacy of His Highness, the Crown Prince Jean. That is true.” Timona paused, then continued. “However, he does harbor some emotion, perhaps akin to yearning, for a ‘father.’”

“Yearning? Seriously?” Such was the surprise Fabio felt that the words were out of his mouth before he even realized it.

“It might be more accurate to say that he has an unusually favorable ‘bias’ for family,” Timona said. “Even though His Majesty may have little interest in His Highness Jean in the capacity of the crown prince, that does not mean he has no interest in what the ‘man who is his father’ was like.”

It was subtle, and it was complex, but as the person who spent the most time by Carmine’s side, Timona understood.

“Similarly, His Majesty has no expectations of the former Crown Princess Acretia,” he continued. “Nevertheless, he harbors both love and respect for the concept of a mother.”

Fabio couldn’t help the teasing note that entered his tone. “This is rare. I’ve never heard you speak so much outside of your reports.”

The Timona he knew was taciturn and expressionless, as much made of steel as a man could possibly be. It was indeed unusual for him to be so loquacious.

However, the truth was that this was more indicative of who Timona was as a person than anything else. He would talk as much as was required, especially if the topic concerned his liege.

Timona le Nain came to a stop, turning to face Fabio. “I have a request for you,” he said.

A moment passed before Fabio replied, “Do you now? No wonder you’re so talkative today.”

Timona ignored the remark. “It’s about His Majesty. He will seek to order the execution of former Crown Princess Acretia. I’d like you to prevent him from doing so.”

“Ah. Yeah, I suppose it would be difficult for anyone else to suggest executing His Majesty’s birth mother. Knowing him, he would take it upon himself to bring the topic up.”

Despite being the emperor by natural birthright, Carmine had a tendency to think of it as a “role” he needed to fulfill. Consequently, when he realized that no one else would be able to suggest Acretia’s execution, he would consider it his duty to suggest it himself. This was one of Carmine’s shortcomings.

As for why it was a shortcoming, it was because to his vassals, he was their liege. And there were none by the emperor’s side—currently, at least—who would oppose his intentions. If, at the trial, it was judged that the emperor wished for the regent’s execution, it would undoubtedly pass.

“Still...” Fabio continued. “If we’re talking advice from a vassal, shouldn’t it come from you? You’re His Majesty’s personal attendant.”

In Fabio’s mind, it was no exaggeration to say that the emperor already considered Timona to be an extension of himself. The attendant was always by his side, and saw to his every need. It was a relationship that could not work if there was no mutual trust. What was more, the Emperor Carmine that Fabio knew was an open-minded ruler who did not mind lending an ear to the advice of others.

However, Timona thought differently. “His Majesty is a person of strict self-discipline—perhaps to the point that it could be called obsessive. And this issue concerns a blood relative of his. He will be more stubborn than usual. Even if my words are logical, he will not heed them.”

Fabio conceded the point with a nod. Though it was merely Timona’s conjecture, he heard nothing he disagreed with. “So you want me...” He paused. “That is, you want it to be a ‘request’ from the Marquess Ramitead?”

“It will be a politically sound objection, provided in a court of law, by an attending chief vassal. Anything less, and His Majesty would not cease with the execution. And I am not of a position which would allow me to speak during the trial.”

“His Majesty can be quite the headache sometimes,” Fabio grumbled. “You too, mind.”

An emperor that sought to kill his own mother because he was convinced it was his duty. An attendant who sought to stop him because he did not wish his liege to wound his own heart. If that wasn’t the definition of a headache, what was?

Still, if executing the former crown princess led to even a ghost of a chance that the emperor would one day go mad or lose his way, Fabio was more than willing to eliminate that possibility.

“Very well,” he said. “Imprisoned or not, it’s not as if the regent is a threat, and besides, executing one’s birth mother might well be considered a violation of the First Faith’s teachings. Even if the nobility don’t care, the people will.”

To honor one’s parents was a First Faith teaching that, in the Western Orthodoxy, was considered a Prime Tenet. However, to the imperial nobility, who believed in the notion of honorable death, executing a parent did not necessarily mean one was disrespecting them. After all, there were some circumstances in which one’s honor and good name were maintained by one’s execution. Of course, this interpretation was a construct of the nobility.

“The capital’s citizenry wouldn’t look favorably on it,” Fabio continued. “And since His Majesty’s image with them is particularly important to him, it would go against his own goals. Consider it done.”

“Thank you.” After that brief expression of gratitude, Timona walked away.

Fabio stared after him for a few moments. “What’s got him acting so meek? Is there going to be a storm tomorrow or something?”

One would be inclined to wonder how Timona usually treated Fabio, if that was enough to call him meek. Certainly, it was a side of Timona that Emperor Carmine did not know.

And fortunately, despite Fabio’s concerns, the following few days saw the imperial capital enjoying fine weather indeed, without a storm in sight.

Time to Gather Evidence

A week had already passed since the coronation.

Duke Warren and Count Chamneau had put their armies to work securing the local region—which should have been under the emperor’s direct control to begin with. They’d faced hardly any resistance, however. Most of the local faction lackeys who’d held the real authority of governance had already made themselves scarce.

My edict regarding the Three Houses Coup had already been promulgated throughout the imperial capital and its surrounds. It had yet to spread wider, but the plan was to deliver it to the Empire’s wider nobility along with other relevant news.

I’d made it clear during my audience, but I’d decided to lay responsibility for the coup onto houses Agincarl and Raul alone. The nobility who’d attacked houses Ramitead, Agincarl d’Decci, and Veria under the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony’s order would get off scot-free.

On that point, our hands were tied. We couldn’t crack down too hard on the faction nobility, lest we make an enemy of every single one of them, and if that happened, we’d never win this civil war. Even if, by some miracle, we did, my subsequent reign would be shaky and unconsolidated.

Consequently, this formed the basic policy I was operating under as emperor: severe treatment of the ducal houses of Agincarl and Raul, and relatively lenient treatment of my other lords. It was a policy I planned to maintain...for the time being.

We still had the nobles who’d attended the coronation locked up, but we could get away with that by ascribing it to the need for a thorough inquiry. The Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony’s transgressions were a laundry list of serious crimes, from assassinating imperial family members to tax evasion and more. It was necessary for us to question the rest of the nobility regarding their knowledge of—or even complicity in—the Dukes’ malfeasance.

Not that we’d get any answer other than “I had no idea,” of course.

I had no illusions that we’d be getting useful testimony from any of the nobility. The only point of our inquiry had been to buy time. The week gave us enough breathing room to mobilize our intelligence agents and the Minister of Finance’s pencil pushers for a careful scrutiny of all official documents in the imperial demesne.

I planned on releasing the majority of the nobility before long, but not all. Those who we had sufficient evidence to sentence would be sentenced—I needed to make examples of them.

I’ll cut to the chase and tell you now that very little evidence of iniquity remained. The nobility weren’t morons, after all. They’d covered their tracks already. The regency had Duke Agincarl’s eldest son in the position of chief secretary, so no doubt they went to him to launder proof of their misdeeds. As for the Chancellor’s faction, the Chancellor probably did it himself.

Still, the sheer amount of shady nonsense going on meant that even if it had all been swept under the rug, there was one hell of an obvious lump. In plainer terms, the numbers were wonky. As it turned out, the calculations on the nobles’ tax documents, which they’d apparently never disclosed to the Minister of Finance despite his repeated insistence, seemed to pretend the concept of tax didn’t exist at all.

In contrast, the Minister possessed thorough records of their reported tax revenues and yearly expenditures. The tax evasion had all taken place in the stages before the reports made it to Count Nunvalle, meaning that we now had both the pre- and posttax evasion records. And when the two were compared, more holes turned up than you’d find in a block of Swiss cheese.

Of course, since the documents had been altered or falsified, we had no idea of who specifically had skimped on their taxes, nor by how much. Nevertheless, that would still let us drag the documents’ owners up in court over the charge of falsifying financial records.

Now, when I said earlier that very little evidence of iniquity remained, I meant that we’d still found some. It wasn’t evidence that our investigation dredged up, but that instead had been provided to us by the Western Orthodoxy.

Incidentally, the close aide of Count Nunvalle’s whom the Count Palatine had suspected of ferreting away the previous emperor’s fortune? Innocent, as it turned out. Well, technically, we hadn’t found proof of the aide’s innocence so much as we’d found proof that it had been a different culprit entirely—someone whose identity created a whole new issue of its own. What to do, what to do...

“Your Majesty,” Timona said, interrupting my thoughts. “Prelate Officium Daniel de Piers has arrived to give his report.”

“Let him in.”

Since the coronation, I’d entrusted my safety to the imperial guard, which had allowed Timona to refocus on his original, more secretarial role as my personal attendant.

When Daniel entered the room, he glanced around for a moment before returning his gaze to me. I didn’t blame him—I’d ordered some rather drastic interior decorating.

All the gaudy—and frankly excessive—precious metals and gems were gone, for one. I’d still have to dress to the nines in public, given I was the emperor, but I’d take the small victories where I could get them.

That aside, the way Daniel quickly scanned the room reminded me of Count Palatine Vodedt. More accurately, it reminded me of someone who knew their way around a fight. The old elf wasn’t a martial artist or something, was he?

After a respectful bow, Daniel began his report. “Your Majesty. Georg V’s execution has been conducted. Likewise, his five closest confidants were also executed.”

“Good. We appreciate the update.”

The Western Orthodoxy was the Empire’s state religion and a denomination of the First Faith, the most widespread faith on the Eastern Continent. After a decision made by its internal council, it had sentenced its top authority in Archprelate Georg V to burn at the stake. Ordinarily, the religion only allowed for interment or burial at sea—an execution by fire was the gravest penalty possible, as it prevented one from traveling to the afterlife. Even the emperor could not sentence someone to death at the stake without the church’s permission.

Since this matter had been decided internally by the Western Orthodoxy, I hadn’t been a part of the process—all they’d needed was my acknowledgment. I had no doubt that the severity of the sentence was in part the church currying favor with me, given what Georg V had done to Baron Nain, but even without that, he likely still would have met the same fate. My understanding was that he’d incurred the enmity of quite a lot of the clergy.

The reasons given for his sentence had been his acceptance of bribes and his wrongful exercise of the church’s inquisitorial branch. The bribes in particular were a violation of the Prime Tenets, which, since he was the highest authority of the entire church, was more than enough to justify his burning at the stake in the eyes of pretty much everyone.

Of course, at the time, Georg V had passed off the bribes he’d accepted as “donations” or “contributions,” a practice common even in the imperial court. Gathering enough evidence to prove they were indeed bribes must have been difficult, since it was such a carefully obfuscated gray area, but Daniel de Piers had nonetheless managed it.

“Quite the dexterous feat,” I said.

“Georg V only ascended to his position with the Chancellor’s assistance in the first place,” Daniel explained. “A development that disgruntled much of the clergy, albeit to varying degrees. With his shield purged by Your Majesty’s hand, it would have been simple to burn him at the stake even without any evidence.”

It didn’t surprise me that the church had been eager to get rid of him, given he’d embezzled all the bribe money for himself. “Still, it was your meticulous groundwork that allowed you to run a clean sweep of his lackeys,” I countered. “Was it not?”

I’d shed blood too, during my purge, but at the end of the day, I’d only killed two people. In comparison, the Western Orthodoxy’s internal conflict had been a bloodbath. “The church has no military might,” my ass. How could I have forgotten that a spell in one’s hands was just as deadly as a sword?

“Even so, a few were able to escape,” Daniel said.

“If you mean the ones who merged with the Raul army, don’t worry about them. That fight will happen regardless. But moving on. You have our gratitude for the evidence you provided.”

The evidence of wrongdoing given to us by the Western Orthodoxy had to do with the bribes that Georg V and his people had taken. Of the nobles who’d given them, there had been not only names from the Chancellor’s faction, but the regency too—evidently old Georgy had been a real money-grubber. Regardless, the fact that the church had sentenced him for accepting bribes could serve as proof that the nobles had given them. After all, to the Western Orthodoxy, both were equally criminal acts.

“We consider it an honor to have been of service to Your Majesty.”

“As for the question of who will become the next Archprelate...” I began. “We will not endorse a candidate. We presume that would be preferable?”

Daniel paused for a moment. “Your Majesty’s discretion is greatly appreciated.”

Georg V had become Archprelate via outside intervention—namely, the Chancellor’s. That had blown up in his face, ending with him going the way of Earth’s witches. Hypothetically, if I were to advocate for Daniel to become the next Archprelate, he could very well face accusations of hypocrisy. That said, without the emperor’s input, the church’s top officials would talk themselves in circles and never get anywhere with the decision. Internally, things would be a mess for some time—which actually served my purposes just fine. I didn’t want the church holding too much power.

“It doesn’t seem like it will stabilize for some time, does it?” I mused.

“The issue should resolve itself once the Empire’s unrest has abated.”

Yeah, that was obvious. It was nothing new either—securing domestic stability was my top priority.

I examined Daniel; he looked as if there were something more he wanted to say. “Is there something else?” I asked.

After some hesitation, he seemed to come to a resolution. “Your Majesty. I strongly believe that Count Palatine Vodedt’s interrogation of the imperial physicians must be stopped at once.”

Currently the Count Palatine was interrogating the imperial demesne’s medical officials over the previous emperor’s assassination. From the way Daniel had phrased his request, it sounded like he had a problem with the spymaster’s methods.

“He is acting like a wild animal,” Daniel finished.

“We would say an animal is rather meek in comparison. Cute, even.” Ever since I’d gained the Count Palatine’s cooperation, he’d seemed more to me like a machine—a robot programmed to serve as the protector of Rotahl’s legacy and nothing else. “Allow us to clarify. You believe that Count Palatine Vodedt is allowing what you perceive to be his emotions over the previous emperor’s assassination to influence his investigation. Is that correct?”

“That... Yes, Your Majesty. You must rein him in. His actions seem borne of nothing more than—”

“Revenge?”

Edward IV’s assassination. If it had never happened, perhaps my inheritance of the throne would have happened more smoothly. But it was equally likely that the Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony would have had me killed earlier on to make way for their preferred choice of successor. Given that, I felt no particular desire to avenge my predecessor’s demise.

Of course, as the emperor, I couldn’t just let the perpetrators go unpunished either. That was why I was overlooking the Count Palatine’s actions.

“Perhaps it is revenge,” I conceded. “But what it is not is the mere venting of his anger. Those still being interrogated by the Count Palatine are the individuals he has already decided are guilty beyond doubt. The majority of the physicians have already been released after hardly any questioning.”

One such individual was the doctor who’d cared for Baron Nain. Perhaps the Count Palatine had only allowed that to happen because he’d already known the man was blameless.

“So long as the Count Palatine has not acted in error, we shall not object to his actions,” I continued. “No doubt he thinks the same of us. He is currently involved in more tasks than this, and his results are nothing less than fruitful.”

The man’s methods were problematic, but what he was doing wasn’t wrong. Above all, he always produced results. Or perhaps, in his cold calculations, even his seemingly vengeful interrogation was but the most efficient method to achieve his goal.

“We are well aware that he is a dangerous man,” I finished. “Just as aware as we are of your concerns. We cannot tell you that how you feel is unjustified, so we will simply say that you may continue to monitor him, should you so wish.”

Daniel was silent for a moment before bowing his head. “Forgive my impertinence, Your Majesty. That concludes my report.”

Daniel de Piers and Alfred le Vodedt. There had to be a past between them that I wasn’t aware of. I’d have to tread carefully.

Trial of the Eight

The imperial capital was stable. So much so that you wouldn’t think that its reigning authority figures had just been purged.

There were a number of reasons for this, but one was that I’d given the investigations into the nobility a week to play out. I could have simply had them “investigated” as a formality and moved straight to the trial process, punishing them how I saw fit, but that would have unsettled the other nobility—barons and knights and such—who hadn’t attended the coronation. Since I was taking my time, the lower nobility seemed content to wait in their homes in the noble district and see which way the dice rolled.

This also applied to the merchant classes. The Chancellor and Minister of Ceremony—actually, I should probably make a habit of appending “ex” to their titles at this point—had dealt with many merchants who could now be considered my potential enemies, since I’d executed their benefactors. At the very least, they certainly weren’t cooperative with the throne. Still, I didn’t do a thing to them. I knew they would be useful soon enough.

Incidentally, touching back on my point about the Dukes’ titles, they had already been stripped of them in formal capacity, and thus “ex-Chancellor” and “ex-Minister of Ceremony” were the accurate terminology. However, since no one had filled the roles they’d vacated yet, use of their former titles was still understood to be referring to them.

As for the citizenry, they were exceedingly cooperative with the throne, on account of my speech. Of course, since their opinion of me could flip entirely if I made a single mistake, you could also say that they were the demographic I needed to tread most carefully around.

In fact, the only unstable element in Cardinal currently was the Western Orthodoxy. Though, since trying to intervene would only invite harm with no benefit, I’d leave them be for now.

“For now” being the operative part of that sentence. The church’s rot had reached its core long ago, and it would need a thorough reformation before long. I’d simply let them continue their infighting until the public opinion was that the emperor had to step in.

It was during this period of relative stability that two major pieces of news came to the imperial capital, roughly at the same time. The first was a declaration from Cavalry Commander Sigmund de Van-Raul, eldest son of the former Duke Raul, stating his intent to inherit his father’s ducal title. The second was also a declaration, sent by August de Agincarl, the Marquess Agincarl d’Decci and second son of the former Duke Agincarl, saying much the same thing.

Oh, yeah, and both men also mentioned they were mustering their armies against the emperor.

The civil war had finally begun.

***

So, there was a new (self-proclaimed) Duke Raul and Duke Agincarl in town, and they were gathering their forces to rise up against me. When I heard the news, I gathered Duke Warren—who had resettled in the imperial capital—Count Chamneau, Count Nunvalle—who had stayed in the imperial capital—Count Palatine Vodedt, and Fabio, who was the new Marquess Ramitead. Despite what you might assume, the meeting’s purpose was not to discuss our strategy against the rebel armies, but to carry out the trial of the nobility we had in captivity.

After seeing that my loyal vassals were seated, I started the proceedings. “We hereby exercise the emperor’s judicial right and declare that this trial is now in session.”

You might wonder if we really had the time to dedicate to such things, but trust me, we were fine. I had strategies in mind to buy time against the armies of Duke Raul and Duke Agincarl, the former of which I had already put into motion.

Apart from the five noblemen I’d already mentioned, we had the prelate liturgia and prelate scriba present to stand witness. After I made my declaration, they began theirs.

The prelate liturgia and prelate scriba were equal to Daniel, the prelate officium, in that they were at the highest rank of the clergy behind the Archprelate. They were also the two individuals involved in the conflict to succeed the role. I figured it was likely they’d try to ease this trial in the direction I wanted, in order to leave a good impression.

Incidentally, it appeared that Daniel had zero plans to get involved in their conflict. He’d mentioned that he wouldn’t be showing his face at court for a while to avoid drawing suspicion. Much of the clergy seemed to share a similar opinion, distancing themselves from the prelate liturgia and prelate scriba—common consensus expected the conflict to become a whole imbroglio and a half. One such clergy member was Deflotte le Moissan, son of Count Palatine Vodedt. After his turn as one of the more active advocates for purging Georg V and his lot, Deflotte had renounced his vestments, saying that his actions had caused matters to proceed far too hastily.

No longer a member of the clergy, his next move was to enter my service as a government official. According to him, he’d only taken up the cloth because it had been the most advantageous way to work for the Empire, and had discarded it because it would only now be a hindrance. Usually, leaving the church wasn’t such an easy process, but since he’d claimed responsibility for the recent events, he’d received special permission.

Despite spending much of his life in the clergy, I was beginning to suspect he didn’t have a religious bone in his body at all, let alone any genuine respect for the First Faith’s god...

Still, there was no getting around our lack of manpower. I welcomed him on the spot and dispatched him to serve as our envoy to the Gotiroir. I’d suspected that he’d already met their chieftain, Gernadieffe, because he’d shown up right after the battle on the hill, which had been masterminded by Daniel. It wasn’t a huge leap in logic to assume that Deflotte had served as Daniel’s messenger, and Deflotte had quickly confirmed that that had indeed been the case.

Deflotte had already reached the Gotiroir’s autonomous territory, and the Gotiroir had publicly declared their support for the emperor, promptly beginning an invasion of the holdings of Sigmund, the self-proclaimed Duke Raul. The original reason Sigmund had remained in the Duchy of Raul with the main Raul forces was because he’d known that the Gotiroir had been preparing for war. So while he could yell and scream and gnash his teeth about me all he wanted, he had to prioritize responding to the enemy at his doorstep.

Meanwhile, I’d instructed the Gotiroir to prioritize minimizing losses to their own army and holding the Raul army’s attention. I’d also told them that, if the Raul army ignored them, they were to rampage throughout the duchy and impair Sigmund’s capacity to sustain the war effort to the best of their ability. The ideal scenario was that they’d lure the Raul army into the mountains and begin a highly favorable war of attrition, but at that point I might as well ask for wishes from a genie as well.

I digress, though. Back to the trial.

“In the interest of brevity, we shall postpone the trials of those of rank viscount or lower until a later date,” I declared. “Now, to begin. We shall commence with the duchies of Raul and Agincarl.”

First, for posterity, we went over the sentences that had been levied upon Karl and Phillip, the ex-Dukes Raul and Agincarl, before moving on to the sentences of Sigmund and August, who had both declared their intent to inherit their respective ducal titles. Since the ex-Dukes’ sentences had not been rendered upon the individual, but upon the “head of their ducal house,” it also applied to their inheritors—albeit that part still needed to be ratified by other nobility.

Naturally, no one present objected to the decision, and so it was confirmed that Sigmund and August would be stripped of all their assets, titles, and positions, and sentenced to death, with their heads to be put on public display.

By the way, after we’d sentenced the ex-Dukes, we’d also seized their various estates within the imperial capital. While there had been some amount of artwork and furniture that could be liquidated to add to the empire’s coffers, it wouldn’t be enough to make a dent. Of cold hard coin, very little remained.

In this age, currency was silver and gold, which was a heck of a lot bulkier and heavier than paper bills. I’d basically expected as much, but it seemed the ex-Dukes hadn’t carried any around with them. Instead, they’d purchased from their merchant associates on credit, which they’d paid off in their own duchies.

Anyway, next came the sentences for the rest of the nobility.

To begin with, for the crime of forging official documents, Fried, the Marquess Agincarl-Novei, chief secretary of the imperial court and eldest son of the former Duke Agincarl, was sentenced to death, with all of his assets and titles to be stripped. It practically went without saying, but falsifying imperial documentation was a grave crime, and he’d done it for years on end, hiding evidence of tax evasion on countless occasions. Given all of that, capital punishment was appropriate.

Next up was actually his son, Phillip de Agincarl—the general, not the ex-duke—who’d been party to his father’s document falsification. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. Of the regency, another nobleman named Joseph, the Count Nunmeidt, received the same sentence for the same crime.

Moving on, we reached the sentencing of the perpetrators of the previous emperor’s assassination. Apparently, it seemed that the handful of medical officers Count Palatine Vodedt had been “interrogating” had finally confessed. Of course, given his methods, their testimony would not have passed muster as credible evidence in a courtroom back on Earth. I’d been reluctant to sentence them based on that alone, but thankfully, testimony from one of the noblemen we had in captivity—Gautier, the Count Voddi—relieved me of the need to grapple with that particular quandary.

Count Voddi was a Chancellor’s faction noble and former Lord Chamberlain who had been present in the imperial demesne and court at the time of the previous emperor’s assassination, making his testimony quite credible. He also stated that Boris, the Count Odamheim, who became Chief Seneschal after the assassination, had been responsible for covering up the evidence. And when this was asked of Count Odamheim under the terms that he would be given immunity for the crime, he readily confessed.

All of this explained what Daniel had meant when he’d accused the Count Palatine of simply venting his anger. His “interrogations” of the doctors seemed rather unnecessary, given that the evidence had been readily available via other means. Regardless, the evidence was used to sentence Chief Physician Auguste Claudiano and three other physicians to death, with their heads to be put on public display, and a further two physicians just to death.

Next, we moved on to those convicted of the crime of bribery: Bernard, the Count Peckscher and Minister of Foreign Affairs; Marius, the Count Calx and Chamberlain of Domestic Affairs; and Jean, the Count Copardwahl, Imperial Cupbearer, and lover of the regent. All three were stripped of their positions and fined—rather light sentences, all things considered. I hadn’t touched their titles.

There was a reason for that, of course. Rather than give the bribes themselves, the noblemen had used patsies, meaning it would be easy for them to claim that their original intent had been to make a donation, and that their patsy had twisted that into a bribe of their own accord. Thus, if I tried to levy any heavier punishment on them, they could force me to lighten it, even if it was obvious to everyone that they were lying through their teeth.

Naturally, my impression of these three noblemen could not get any worse. If they thought they’d get away with a quiet death of natural causes, they were sorely mistaken.

The rest of the nobility were more or less declared innocent. Sylvestre, the Count Kushad; Valère, the Count Mehimrahl; Theodore, the Marquess Arndal; Theophan, the Count Vadpauvre; Gautier, the Count Voddi; and Boris, the Count Odamheim all stood as examples of ones I’d release in due time—that being when the timing best suited me, of course.

There were also nobles whose sentences were put on hold, such as Hubert, the Count Buhnra and former captain of the imperial guard. He was still undergoing an investigation for misappropriating the imperial guard for his personal use. Of course, basically everyone had done that. In his particular case, I was just stalling for time.

In regard to this series of trials, there was a big difference between the sentences I wanted to render and the sentences I could render. To use Count Buhnra as an example, the ordinary trial process would declare him not guilty and see him freed from our captivity. However, his county was located in between the Duchy of Warren to the north and the Marquessate of Ramitead to the south. If we let him go and he linked up with the Raul army, the worst-case scenario could see the imperial capital cut off from Duke Warren’s holdings. From a strategic point of view, the County of Buhnra was a possible spearhead and staging ground for enemy counteroffensives; we could not allow the Raul army to have it.

Currently, we had a fair few plates spinning in the County of Buhnra. The count could accuse us of unjust imprisonment all he wanted, but he wouldn’t get his trial until they were over with.

Finally, we came to the regent Acretia.

Her crimes included aiding in the manipulation of the young emperor, unjust imprisonment of the former crown prince’s other wives, ordering the assassination of the servant suspected of birthing Jean’s other child, and ordering the assassination of the child in question. There was also the possibility that she had turned a blind eye to the previous emperor’s assassination. All in all, her crimes easily warranted the death penalty.

“In light of these charges being uncontested, the regent Acretia is found guilty,” I proclaimed. “We sentence her to be stripped of all assets and positions, and to be put to death. Should any object, make yourself known.”

Fabio raised his hand. “I have an objection, Your Majesty.”

“Permitted. You may speak.”

“Your Majesty, in no nation throughout history is there record of a sovereign killing their own mother. Not even the worst of despots committed such an act.”

Wait, really? There’d been that Roman emperor who’d killed his mother, but then again, that had been on Earth. Racking my memory proved Fabio right; if any examples existed in this world, I certainly hadn’t heard of them.

“Furthermore, the public hold the virtue of filial piety in high esteem,” Fabio explained. “The opinion of the citizenry is quick to change. If Your Majesty were to sentence Her Highness Acretia to death, there would be negative backlash sufficient to rival the support you have won of late, in my estimate.”

“That much?” I asked.

“Yes. At the very least, it is not something Your Majesty would want.”

Hmm. Well, it wasn’t like it had to be the death sentence, in Acretia’s case. Especially if it bought me the people’s distrust. If she began to get on my nerves, I could always just have her assassinated.

“We understand,” I concluded. “We shall rectify the sentence. The regent Acretia is to be stripped of all assets and titles, and sentenced to life imprisonment! Should any object, make yourself known.”

No objections were raised.

“With that, this trial is adjourned,” I finished.

As the two clergymen announced something to the same effect, I found myself exhaling a breath I hadn’t known I’d been holding. Strange.

Naval Policy

After the two clergymen left the room, I addressed the lords sitting before me. “Though the trial may be over, we wish for you to remain. We intend to hold council.”

“Council, Your Majesty?” There was a note of confusion in Count Nunvalle’s voice.

I didn’t blame him. My cursory studies of the previous emperor’s reign had revealed that, while he’d solicited his lords for their opinions, he’d never held open discussions or similarly collaborative gatherings.

“Yes,” I said. “We wish to revive the Early Giolus Dynasty practice of witenagemot.”

During the Early Giolus Dynasty of the Rotahl Empire, a witenagemot was when the emperor gathered his high nobles and family and consulted them for their opinions on policy. There were no witenagemots in the Late Giolus Dynasty—not a single one. I won’t bore you with the details; in essence, they apparently considered it “a factor in the decline of the empire.”

Personally, though, I thought the idea of a political roundtable in of itself was a perfectly fine idea—so long as I took care not to repeat the mistakes that had caused the original to gain such a negative reputation.

“Of course, that is a matter for the future,” I continued. “Today, we have readied this venue because we simply wish to hear our lords’ opinions. Unlike during the trial, you may speak proactively—in fact, we encourage it.”

“I understand, Your Majesty.”

“First, we wish to discuss the matter of the previous emperor’s missing fortune. Or, more specifically, the culprit responsible.”

Count Palatine Vodedt had continued his investigation into the matter, coming up with a number of findings. To begin with, after the previous emperor’s death, the Minister of Ceremony had established the new position of Chamberlain of Finance, appointing to it Salim, the Count Dienca. Naturally, an entirely new position with influence over the empire’s coffers was highly suspicious. Count Dienca had been at the top of the Count Palatine’s suspect list.

Nevertheless, after the count was arrested during the coronation and investigated afterward, he turned out to be completely uninvolved. It appeared that “Chamberlain of Finance” had been a made-up position with no responsibilities, leaving him ignorant of the matter. Still, since there was no evidence that he was innocent either, we’d put his trial on hold and kept him imprisoned.

In regard to actual evidence, a clue had been found among a batch of documents hidden by the chief secretary. It was a record of the previous emperor’s fortune being transferred to a certain individual following the crown prince’s death. And that individual was...

“Hilaire Fechner,” I said. “The woman who we believe to be the director of the Golden Sheep Trading Company, which is puppeteering the Teyanave Confederation from the shadows. Count Palatine Vodedt, explain.”

“Of course, Your Majesty.”

Hilaire Fechner was born the daughter of one of the Empire’s wealthiest merchants. By the age of fifteen, she had already ousted her father and taken over his enterprise, the White Sheep Trading Company, and in a mere five years, earned the honor of being the emperor’s personal trader. She revised the name of her company to “Golden Sheep” to reflect this rise in status, and swiftly turned it into the largest merchant operation in the Empire. However, after the previous emperor was assassinated, she vanished.

“A number of ships among the regency’s remaining trading vessel records match the description of the false ships identified by a prior investigation of Marquess Ramitead’s,” the Count Palatine explained. “It appears that they continued to make use of imperial ports for some time after the previous emperor’s passing.”

I took over. “However, it seemed that the Golden Sheep didn’t like the former Duke Agincarl’s excessive tariffs and docking fees. Thus, Miss Fechner set her sights on acquiring a port suitable for her enterprise’s needs.”

The Empire’s coastline was almost entirely controlled by regency nobility, who raked in huge profits off the tariffs and docking fees. Whereas the Chancellor had risen to power and expanded his faction with military strength, the Minister of Ceremony had done the same with economic strength.

Hence why the Chancellor had used Vera-Sylvie against her father, Count Chamneau. With a leash on the count, Chamneau’s port became the sole port owned by the Chancellor’s faction. Incidentally, since all of the merchants in cahoots with the Chancellor’s faction used that port, it was overcrowded to the point that the Golden Sheep likely hadn’t been able to access it.

“That was when she turned her eyes to the Teyanave region,” the Count Palatine continued. “There was regency influence present within the region before its secession, but she managed to supply enough capital and stoke enough fires to convince its nobility—who are regarded as neutral—to muster their armies.”

“So that is what led to the Teyanave Confederation...” Count Chamneau muttered.

I nodded. “Both the regency and the Chancellor’s faction sought to bring the region back into the fold by force, but you all know the result of that: an ignominious defeat.”

On the Eastern Continent, the Golden Sheep sold luxury goods like sugar, which they obtained via their massive ships capable of intercontinental trade. Our running theory was that they were using their nigh bottomless coffers to manipulate the Teyanave Confederation in secret.

“If it is true that Miss Fechner purloined our predecessor’s fortune, then the dignity of the Empire is riding on her capture,” I said.

“Are we certain the evidence is credible?” Duke Warren asked. “I have been told that Golden Sheep agents have infiltrated my duchy. Did they leave behind proof of these dealings?”

“An entirely reasonable concern,” I acknowledged. “We are also suspicious of the fact that this trail was simply left out in the open. However, Miss Fechner’s disappearance and the theft of the previous emperor’s wealth is too obvious of a link to ignore.”

There were two possibilities: Either there was a different culprit who’d framed the Golden Sheep, or Hilaire Fechner had purposefully left the trail for us to discover. “In order to confirm this, we are considering putting out a wanted notice for Miss Fechner,” I revealed.

If she had been framed, the true culprit would just ignore it. But if she’d intentionally left the trail, she might respond to us with unexpected honesty.

“A wanted notice...” Fabio murmured. “But the Teyanave Confederation is currently an enemy of the Empire. Will it have any effect?”

That was a valid point. Hilaire Fechner was no doubt in the confederation, so being wanted by the Empire would mean nothing to her. She could simply ignore it and go on with her life.

“We have no other options that might be effective,” I admitted. “Once the Empire is stable after the civil war, it should be more than possible to force the Teyanave Confederation back into the fold. However, even if we do, the Golden Sheep will simply escape on their ships, and Miss Fechner will slip through our fingers.”

Perhaps a sea blockade would have been possible, if the Empire had possessed anything resembling a decent navy. As it was, however, our seas had belonged to Duke Agincarl for far too many years. It was genuinely questionable whether we could even win a naval war against the Golden Sheep company’s fleet.

“Even so, if Teyanave is their base of operations, it may still be worthwhile to strike at it,” Duke Warren said.

A very military opinion. I shook my head. “Harming the Golden Sheep would only make an enemy out of them. Besides, they’ve been procuring luxury goods from other continents since their time serving the previous emperor. They’ve undoubtedly possessed strongholds in the Central and Southern Continents since before they orchestrated Teyanave’s secession.”

“The Empire currently possesses no shipyards capable of building vessels large enough for intercontinental trade,” Count Palatine Vodedt added. “We may be able to purchase one or two from the Hismaph Kingdom or elsewhere, but our estimate of the Golden Sheep’s number stands at several dozen. It is almost a certainty that they possess a large-scale shipyard—or multiple—on other continents.”

The Golden Sheep Trading Company was moving slaves from the Central Continent to the Southern. My guess was that they’d put some of said slaves to work and built a firm foothold for themselves somewhere. Even if they lost the Teyanave Confederation, they could simply reestablish a new base of operations somewhere else on the Eastern Continent.

“Pardon me, Your Majesty, but you mentioned that harming the Golden Sheep would ‘make an enemy’ out of them. But are they not already an enemy of the Empire? It was my impression that that was the premise we were working under.”

“Not at all, Count Chamneau. Our enemy is not the Golden Sheep Trading Company, but the Teyanave Confederation.”

The Golden Sheep had arranged the Teyanave Confederation’s secession for their own benefit, as well as to harm the Minister of Ceremony’s influence. In short, their enemy was not the Empire, but the regency. In fact, forget thinking of us as enemies; I doubted they even mildly disliked us.

That might have changed after the modest lengths I’d gone to in the name of harassing them, though. Who knew what they thought now?

That aside, if it was true that Hilaire Fechner had intentionally left the evidence, did that mean she’d predicted that I might end up in conflict with the factions? It seemed too preposterous to even consider—I hadn’t even been born at that point. No ordinary human could possess such foresight.

But then, what if she wasn’t an ordinary human? That was a more than plausible possibility...

“Your Majesty?”

“Ah, pardon us,” I apologized. “Regarding the wanted notice. Our current idea is to indicate on it our willingness to compromise.”

The theft of an emperor’s wealth was, naturally, a grave crime. But we could let the Golden Sheep know that we would consider reducing the associated sentence if they accepted a number of our conditions.

“We wish to entice them into becoming our allies,” I explained.

“They’re too dangerous, Your Majesty,” Fabio objected. During his investigation, he’d been the one who’d gone boots to the ground and felt the risk firsthand. “They could very well devour us from within.”

“They could, Marquess,” I conceded. “It would constitute a significant risk. But we are more apprehensive of allowing them to act as they please as our enemy. Better to hold their reins and keep them under constant surveillance.”

If the Empire had possessed a strong navy, antagonizing the Golden Sheep would have been a viable choice. Unfortunately, we didn’t, and our options were limited. We could also spend several decades beefing up our navy to the point where we could comfortably beat them, but what would that even achieve?

“I see. So Your Majesty’s intention is to maneuver them into the path of the Agincarlish Navy?”

As expected of Duke Warren, he’d immediately noticed the benefit of gaining the Golden Sheep as an ally.

The self-proclaimed Duke Agincarl, who was currently mustering his army, would no doubt take over the navy as well. It wasn’t much of one, but that was still better than the fat load of nothing we had. Even if we defeated him on land and seized the entire Duchy of Agincarl, we had no effective method of bringing the navy back under our control. Worst-case, they could turn into pirates and scuttle the entirety of our sea trade.

But the Golden Sheep would have the know-how to deal with pirates. Plus, a good number of Teyanavi warships had to actually belong to the Golden Sheep—the confederation had produced far too many too quickly after their secession for an unassisted effort. And if we allied with the Golden Sheep, that was that many fewer warships that the confederation could field against us.

“There’s one other major benefit,” I said. “Currently, we are facing a lack of military assets. The bodies we could compensate for with conscription, but we have no weapons to put in their hands. However, we’ve confirmed that the Golden Sheep are exporting mercenaries and weapons from the Central Continent. If we make purchases of the latter, we can solve our shortage of arms.”

As a matter of fact, our lack of weapons was currently our biggest problem—to the point that I’d even give the devil the time of day if he came knocking with a deal.

Speaking of problems, though, another was that we had hardly any information about the other continents. There was little interest in the Central, as we on the Eastern thought of it as the “Old Continent.” Rather, the nations in our neighborhood were more interested in the Northern Continent.

However, it was the luxury goods from the Southern Continent that held the potential to change the world. If we were too slow to act, other countries would seize all the slices of pie for themselves.

“But...will they be receptive?” Count Nunvalle contributed, somewhat hesitantly.

I understood his concerns. Interrogating someone about their crimes in one breath and asking to buddy up in the next was a good way to get ignored. But the Golden Sheep were merchants. And not just any merchants: ones whose acute senses had placed them at the forefront of the era.

“We believe they will,” I asserted. “In the first place, they want to export imperial food supplies to the Central Continent. Also, the Empire represents a good thirty million untapped consumers. But most importantly, we do not currently possess a personal trader. We find it doubtful they would pass up these opportunities.”

The Empire had not experienced large-scale war in close to a decade, meaning it had an abundant surplus of food, if nothing else. However, due to the disastrous mismanagement of the economy by previous administrations, the domestic circulation of currency was basically stagnant, and the people had reverted to a barter system, mainly using food. Yet, the surplus of said food meant its value was low, creating a severe societal deficit of other commodities. Our situation was a perfect match for the Golden Sheep’s needs.

“However, we must not forget that the Golden Sheep are capable of establishing independence for an entire nation simply to acquire a convenient sea port,” I reminded. “It is entirely possible that they will feign loyalty to us while maintaining their connection to Teyanave in secret. In order to prevent that, we must sever their connection to the confederation.”

Basically, I wanted to avoid the Golden Sheep using us to kill two birds with one stone. The Teyanave Confederation, as a country, was rather unique. It had no sovereign, and was instead ruled by a, well, confederation of lords who had seceded from the Empire. As such, they ostensibly took orders from no one. In reality, they tried to stay in the Golden Sheep’s good graces. To a certain extent, anyway. Our society was still a class system, and there was no way nobles would allow merchants, no matter how influential, to dictate their actions.

In addition, it seemed that the whole “Carmine Hill” thing hadn’t been a futile effort on my part, further widening the rift between Hilaire Fechner and her Golden Sheep, who prioritized profit, and the Teyanavi lords, who prioritized their nation. Enmity had most definitely taken root.

“We will send an envoy to Teyanave to negotiate,” I said. “We will demand the extradition of Hilaire Fechner, and in return, we will offer two things: formal recognition of the confederation as an independent nation and the establishment of an armistice, and the guarantee to leave the Golden Sheep’s other elements within the confederation, for the lords to do with as they please.”

In essence, we’d be telling a posse of nobles that they could keep their little separatist project if they just handed over the mere merchant giving them orders. I had no doubt they’d agree. As for the part about the other Golden Sheep elements, the Teyanavi lords saw the company as their golden goose. Giving them the approval to exploit it at their leisure was too good an offer for them to ignore.

“Your Majesty,” the Count Palatine said. “This has not yet come up in my reports, but our investigations indicate that when Teyanave seceded, the Golden Sheep also managed to bring a number of other companies who disliked the former Duke Agincarl’s tariffs with them. I would suggest offering them a letters patent for the Golden Sheep Trading Company in exchange for Hilaire Fechner’s person.”

I considered that a moment. “That is a good idea. Throw in the possibility of becoming our personal trader as part of the reward.”

“If we make the bait that appealing, won’t the Golden Sheep simply stonewall us instead?” Fabio asked. “They could wash their hands of Teyanave and the Empire entirely and move their base of operations to another continent.”

“That is possible, yes,” I acknowledged. “However, Marquess Ramitead, they are, at the end of the day, merchants. We believe that, rather than leave this continent ‘for free,’ they will choose to bear the risk of accepting our offer.”

I surveyed my lords. It seemed no further opinions would be forthcoming. For what was supposed to be a council, it had ended up being a whole lot of everyone nodding along to my ideas. Still it hadn’t been a total waste of time. I’d heard everyone’s opinions and they’d gotten to hear the thought process behind mine.

“Count Palatine Vodedt, see to the necessary arrangements,” I ordered.

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

Now then, it was time to get into the actual meat and potatoes.

“Next, we wish to determine our military policy, and our course of action against the Agincarl and Raul armies.”

Land Policy

First, we needed to review our current situation.

Dukes Raul and Agincarl were mustering their armies, but they wouldn’t be marching on the imperial capital anytime soon. They were both still gathering their troops, getting their supplies in order, and handling the bureaucratic and ceremonial boondoggle that accompanied the inheriting of their fathers’ titles.

Ordinarily, the transfer of power followed rigid procedure. Whenever it happened suddenly, there was always the possibility that the heir would find themselves with none of the resources or privileges their predecessor had enjoyed. Case in point: me. After my father and grandfather had died and the title of emperor had passed onto me, the authority and vassals under their purview had scattered to the winds.

Of the latter, Crown Prince Jean’s vassals had mainly gone to work under Duke Warren. It was pretty inevitable, if you thought about it—when one lost their liege lord, who better to move on to than one of their most trusted confidants?

Because of my purge at the coronation, a similar process had occurred within the ducal houses of Raul and Agincarl. Unlike me, their heirs still had a guaranteed degree of influence to establish themselves from, but abrupt changes caused abrupt—and significant—recoil. Their power bases, though seemingly solid, were likely brittle on the inside.

There had been the possibility that Duke Raul would try to seize the imperial capital on his own, given the significant size of his private army, but that was no longer probable with the Gotiroir pinning him down at his eastern border.

“At present they lack the means to mobilize, but we do not,” I said. “In short, we have the initiative. So, we ask of you, our lords: Will we start from the east, or the west?”

Trying to put down both of the dukes’ armies at once was not an option. I wanted to keep our forces operating as a single unit—with the exception of the branches we sent out to create diversions or defend key areas, of course.

Incidentally, we weren’t so much deciding our current policy as our future policy. Currently, our forces were busy securing control over the Empire’s south. Our spinning plates in the County of Buhnra were a part of that.

In terms of other relevant concerns, there was the question of whether Marquess Dozran—Anselm, the man who’d outmaneuvered his father and older brother to seize power—would obey us. We’d already sent out an envoy summoning him to the capital, but if he decided we were going to be enemies, we’d probably have to start this campaign by subjugating his marquessate.

“Then, Your Majesty, as one familiar with the Empire’s pecuniary circumstances, please allow me to provide my opinion.” It was Count Nunvalle, the Minister of Finance, who started us off. “At the present point in time, the people of the Empire lack a wide variety of commodities. However, there is a relative surplus of food. I would suggest prioritizing the Agincarlish region to the west and securing the ports, which would allow us to conduct trade and see an influx of foreign goods.”

The Empire had many land neighbors, but the majority either saw us as enemies or were standoffish at best. Attempting to open trade routes with them would only result in them lowballing our exports and overpricing theirs. Thus, if we were going to expand our commerce endeavors, we needed to control our seas. Exactly the sort of suggestion I expected from my resident bean counter.

“As commander of our forces, I believe we must first restore order in the east.” Duke Warren was next to offer his thoughts. “If we began by conquering the Agincarlish region, I would anticipate strong resistance from the old Agincarlish nobility. They are more trouble than they are worth. However, the Raul region is ethnically Bundartian. After a string of victories, stability should be relatively simple to establish.”