Table of Contents

Preface

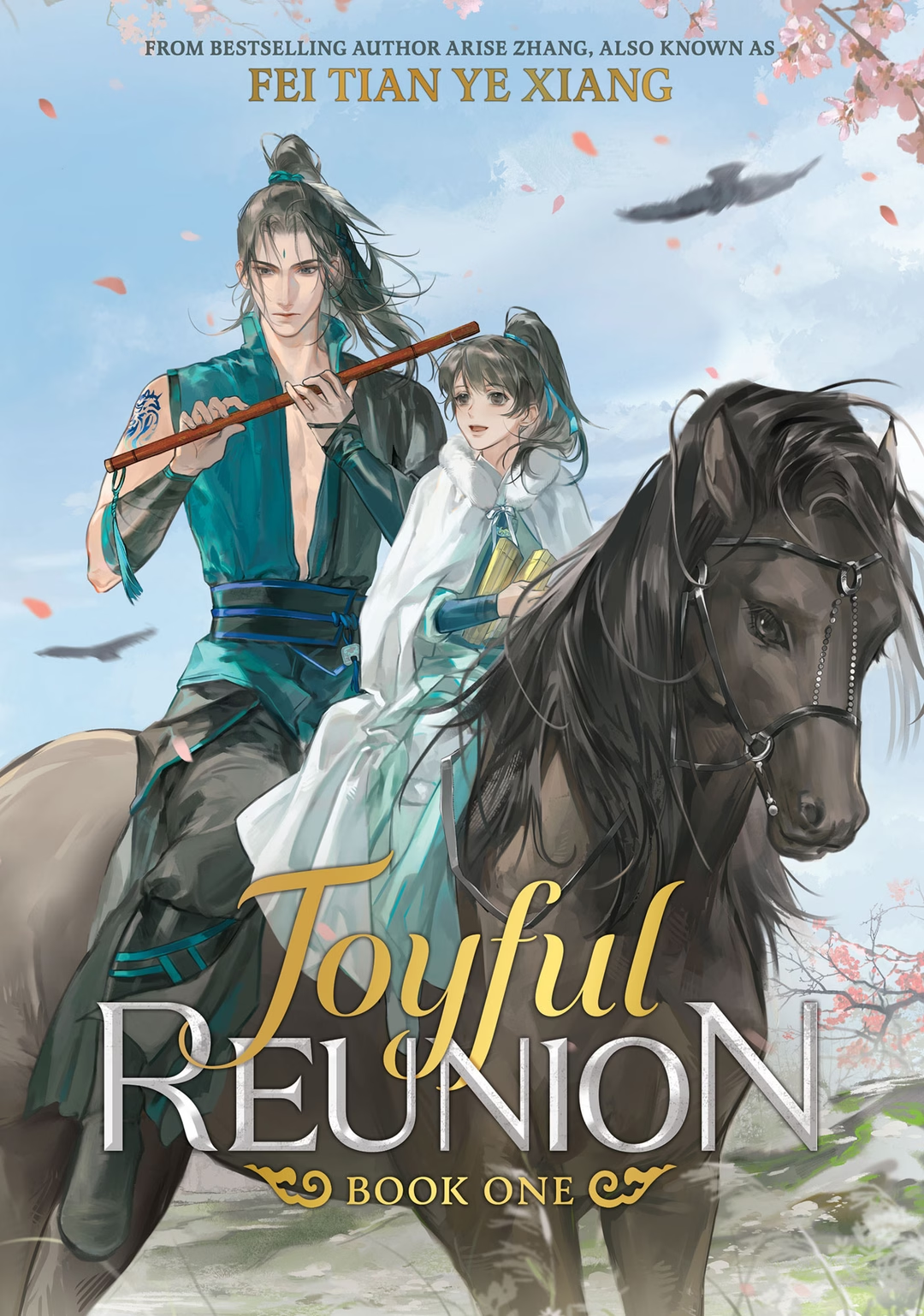

ASSASSINATION is an important subject in literary works, and contract killing is one of the oldest professions in history. It is often said that when a country falls into disorder, when a sovereign loses the ability to govern, or when a war comes to a standstill, assassins are relied on to restore the status quo. When I first began writing Joyful Reunion, I pictured it as an assassin story. I wanted to tell, using a fictional historical setting, a tale of warriors across the land in this age of cold weapons.

All warriors bear their own beliefs and have their own missions in life. In antiquity, when blades and poison still had a role to play, a powerful assassin could determine the governance of an entire empire and the fate of its people. But if this assassin were to take off his stealthy disguise and come out of the dark, would he be cold and ruthless, a mere tool for killing—or would he also feel the full emotional spectrum of an ordinary person?

Thus, in this story, I came up with Four Great Assassins, all of different ages, who are retained by sovereigns and protect them with utmost devotion, and as a result must answer complex questions that test the nature of humanity. As a prince lost to the world of commoners, Duan Ling finds his fate entwined with theirs as he slowly makes his way back to his court with hopes of taking his rightful place. The other protagonist, Wu Du, faces myriad challenges as Duan Ling’s guardian. Even so, they protect each other and stand by each other’s side, and, with their own modest power, fight against imperial authority, the civil officialdom, and countless other hardships, finally completing their life’s mission.

Among my works, this story is written in a more classical style—many of the beliefs and attachments of these ancient assassins exist no longer, yet the sparks of humanity still flicker across time between the pages of the history books. I’m thrilled this story can be translated and published in English, and I hope this will be a brand-new experience for my readers.

FEI TIAN YE XIANG (ARISE ZHANG)

Chapter 1

THE BLIZZARD RAGED, and within the endless expanse of snow, an army coiled like a serpent. Thousands of cavalrymen surged after a lone warrior clad in black armor, the steed beneath him galloping so hard and fast that blood foamed from its nostrils. A storm of arrows rained down upon him, darkening the snowy fields.

“Foolish! Arrogant!” The pursuing general shouted over the distance, “If you know what’s good for you, you’ll surrender and return to Dongdu with me to stand trial!”

“Even you betray me!” the warrior roared back furiously.

“Jianhong!” Another formation of a thousand swarmed in from his flank. In that moment, enemy forces blanketed the snow as far as the eye could see. A deep, resounding voice rang out from the reinforcements. “Your Highness, you have no one left. You cannot do this alone—why drag this out? Continue to resist, and you will only ensure more soldiers lose their lives. Do your former brothers-in-arms mean nothing to you?”

“Brothers-in-arms?” the warrior sneered, sheathing his sword. “The oaths of the past have turned to lies. Who remembers what promises we made back then?! Must you overthrow me at all costs, even if you sacrifice the lives of every soldier here today?”

“There is little difference between life and death—but though the living world is vast, it no longer holds a place for you!”

War drums pounded amid the swirling snow.

Boom! Boom! Boom!

The beat was like the footsteps of a colossal god walking into the world from the infinite bounds of the horizon, every step stirring up a squall that veiled the sky and blotted out the sun.

“Give up, Your Highness. You have nowhere to run.”

Upon the hill, a third formation of cavalry loomed into view within the blizzard, and a young, handsome general took off his helmet and tossed it into the snow. The freezing winds carried the young man’s voice to his ears. “How about you hand over the Guardian, enjoy a cup of wine, and I’ll send you on your way to the afterlife? Everyone must someday die.” His voice was mellow over the storm. “So why must you be so stubborn?”

“You’re right.” Li Jianhong’s robe fluttered beneath his armor. He sat up in the saddle amid the wind and snow and spurred his horse onward, calling out, “Everyone must die, but it is not yet my time. The one to lose their life today…will not be me!”

Far away from Yubi Pass, where they fought, there rose the lonely melody of a Qiang flute, mingling with the powdery snow to scatter on the ground. The cavalry raised their spears to the drumbeat; when it stopped, the three formations would merge and launch their thousands of spears at the Prince of Beiliang, Li Jianhong.

“Enough talk,” Li Jianhong said, his voice cold. “Who wants to die first?”

“If you wish to fight to the death here and abandon your former glory, you may,” the young general roared. “A thousand gold and the title of marquis to whoever takes Li Jianhong’s head today!”

The drumming ceased, the cavalry shouted in unison, and with a roar that echoed between heaven and earth, Li Jianhong wheeled around and spurred his horse at a reckless gallop toward the army streaming down the snowy slope. The troops yelled as they charged downhill.

Tens of thousands surrounded one man, soldiers cutting toward the formation’s center. Li Jianhong dropped the reins and pressed his knees to his horse’s flanks. Left hand hefting a longspear and right hand unsheathing his blade, he charged against the tide of onrushing cavalrymen. The snowpack collapsed with a rumble, submerging the pursuing soldiers and their horses in wild, powdery snow.

Blood misted the air as Li Jianhong sliced through a charging cavalryman’s glaive with one hand, speared the galloping horse, and heaved it back toward the enemy. Limbs parted from bodies under his sword. Its sharp blade cut through iron like mud as it cleaved through the incoming hordes. It was ten thousand to one, but Li Jianhong slashed through the formation like a tiger among a flock of sheep.

His steed approached a cliff towering thousands of feet above the darkness below. The lip collapsed under its hooves with a thunderous crash, and, unable to escape, countless men and horses tumbled in with the debris. At the edge of the abyss, Li Jianhong spurred his warhorse into a jump.

For a moment, all that could be heard on the snowy hill was a long whinny, the slowing of footsteps in the snow, and the din of the avalanche. The sky darkened, as if a cloud had rolled over the north. The commander of the pursuing troops stopped his horse at the edge of the cliff, a scattering of fine snow dusted over his copper armor. “General, we couldn’t find the traitor.”

“No matter. Withdraw for now.”

Chapter 2

Springtime grass grows upon the fallen kingdom, its palace buried beneath ancient hills.1

AFTER THE EMPEROR OF LIAO marched south and conquered the city of Shangzi, formerly held by the Chen Empire, the Han people retreated south through Yubi Pass. Capitalizing on their victory, the Liao army swept onward and claimed another three hundred li2 of land south of the pass, including Hebei Prefecture. Runan, a city in the prefecture, had been a thriving trade and distribution center linking the Central Plains and the lands north of the Great Wall—but when it fell to the Liao Empire, the Han people fled west and south. Once the largest city in Hebei, it was now filled with broken tiles and dilapidated houses. Not even thirty thousand families remained.

One of these remaining families was the Duan clan.

The Duan clan was neither too large nor too small. They owned an oil mill as well as a pawn shop, and they dabbled in reselling items to passing merchants. The head of the household had died of consumption before he reached thirty-five, and it was left to his widow to keep things running smoothly for the whole family.

On the eighth day of the twelfth month, the day of the Laba Festival, Runan was bathing in the burnished glow of the setting sun, its bluestone-paved alleys alight as if tiled in gold—when a blood-curdling scream erupted from the Duan clan’s courtyard.

“You stole from the madam?!”

Blows rained down on a muddy child dressed in rags, the housekeeper’s stick thudding against his body. Bruises splotched his face, and one of his eyes was swollen; bloody scratches ran down his arms.

“Say something, you little bastard! You beast!”

The child tried to run, darting behind the nearest building to hide, but collided instead with a servant girl. The impact knocked her wooden tray from her hands, and the housekeeper screamed at him once more.

With nowhere left to flee, the child turned and desperately tackled the scolding woman to the ground, then punched her in the face. When she moved to hit him again, he opened his mouth and bit her.

“Help!” the housekeeper shrieked.

Her cry alerted the stableman, who rushed across the courtyard with hayfork in hand. Unhesitating, he struck the child over the head. The blow knocked him senseless, and he fainted—but the beating continued. The stableman thrashed him bloody, carrying on until the pain itself roused him again, then grabbed him by his dirty collar and threw him into the woodshed. The door slammed and the lock clanked.

The child lay dazed and wounded on the woodshed floor.

“Wontons! Get your wontons!” called an old man’s voice outside. Every evening, the wonton seller Lao-Wang strolled the streets with his goods in baskets tied to a pole across his shoulders.

“Duan Ling!” A child’s voice shouted from beyond the courtyard. “Duan Ling!”

The sound of his name dragged him back to consciousness. Duan Ling’s shoulder had been gouged by the hayfork, and a rivet had punched a bloody hole into his palm. He swayed, nearly staggering as he stood.

“Are you okay?” the child outside yelled.

Duan Ling gasped for breath, his face scrunched in agony. After making an attempt to stand, he slumped back against the wall and forced out an “Uh-huh.” The child outside, reassured, hurried away.

He slid slowly down the wall and collapsed onto his side, where he lay curled up in the damp, dark woodshed. Gray sky was all he could see through the shed’s high window. Fine snow drifted through the air, and among the clouds there seemed to be a sparkle of starlight right at the center of the sky.

A frosty silence rolled in as the evening darkened to night. Thousands of families across Runan lit warm, homely lamps and fires while the snow softly blanketed their roofs. Only Duan Ling was left trembling in a cold woodshed, too hungry to think. Hazy, disorganized scenes crossed his mind’s eye. Sometimes he saw his deceased mother’s hands. At others, he saw Madam Duan’s beautifully embroidered robe, or the housekeeper’s ferocious, scowling face.

“Wontons!” Lao-Wang cried again.

I didn’t steal anything, Duan Ling thought. He squeezed the two copper coins in his good hand a little tighter, his vision darkening. His consciousness was blurred, patchy. Will I die?

Death had always seemed so distant. Just three days before, he’d seen a crowd surrounding a beggar who’d frozen to death under the Bluestone Bridge. In the end, his body had been hauled onto a cart, transported to the city outskirts, and tossed into a mass grave. Duan Ling himself had joined the fun and followed the corpse cart with a few other children. He saw the beggar’s body wrapped in a straw mat and buried in one of the pit’s open graves, next to another that was yet empty. Perhaps, after his death, he’d be buried next to that unnamed beggar.

As the night wore on, cold seeped into Duan Ling’s stiffening body. His shallow breaths became a pale white mist, drifting into the air and mingling with snowflakes. For a confused moment, he thought the snow had stopped and the sun had appeared before him, like a summer morning’s dawn.

The imaginary sun resolved into the light of a lamp shining on his face as the woodshed door creaked open.

“Come out!” barked the stableman.

Another man—whose voice he did not recognize—asked, “This boy is Duan Ling?”

Duan Ling was lying on his side, facing the door. With much difficulty, his muscles spasming, he managed to sit upright. A stranger brushed past the stableman and knelt before him, examining his bruised face.

“Are you sick?” the man asked.

Duan Ling’s mind was hazy with shadows and hallucinations. The stranger produced a pill from his robes and pushed it past Duan Ling’s lips, then scooped him up from the cold ground. Through his disorientation, Duan Ling caught a whiff of the man’s scent. With each swaying step away from the woodshed, he grew warmer—first from being held in the stranger’s arms, and then as the air lost its chill.

A hole had torn in Duan Ling’s worn old coat during the beating, and the reed flowers sewn inside for insulation spilled onto the stranger as he walked.

Dim lights flickered against the dark, lonely night, and the dried reed flowers scattered behind them down the long corridor. From either side came the unrestrained laughter of maidens, underlaid with the rustle of falling snow outside warm rooms. The world continued to warm and grow brighter; Duan Ling seemed to travel from freezing winter to balmy spring, from the dark of night to the light of day.

The world is an inn for all beings, days mere passersby in the face of eternity.3

Duan Ling’s breathing deepened as, slowly, he regained consciousness.

The stranger had carried him to the main hall, which was brightly lit and comfortably heated. Madam Duan lounged on a divan with a piece of scenery-embroidered satin resting loosely in her hands.

“Madam,” the man said.

Madam Duan’s words held a smile as she asked, “Do you know this child?”

“I don’t,” said the stranger—but he continued holding Duan Ling in his arms.

The medicine the man fed him had dissolved on Duan Ling’s tongue. His frozen-stiff core finally seemed warm again, his strength returning. Though the stranger held him against his chest, both of them facing Madam Duan, Duan Ling dared not lift his gaze. He saw only a small portion of the splendid brocade covering the divan.

“Here is his birth certificate,” Madam Duan said.

Her housekeeper stepped forward and offered it to the stranger.

Duan Ling was short, sickly-looking, and skinny. He struggled weakly in the man’s arms in fear, and was put down again; once settled back on his unsteady feet, he leaned against the man for support. He noticed the stranger was wearing black robes, damp martial boots, and had a jade pendant in the shape of an arc fastened to his waist.

“Name your price, Madam,” said the man.

“Honestly, the Duan clan should never have accepted this boy in the first place,” Madam Duan said with a smile. “But when his mother came back with child, it was the middle of winter and she had nowhere else to go. As the saying goes, heaven cherishes life. I took her in. But once she settled down here, there was no end to it.”

The man said nothing, only gazing with steady intent at Madam Duan as she paused. After a long moment, she sighed. “I’ll put it this way: He was entrusted to me by his mother, Duan Xiaowan. She even gave me a letter. Would you like to see it, my lord?”

The housekeeper brought him the letter as well, which he tucked away without so much as a glance.

“I don’t even know your name,” Madam Duan continued. “If I just hand you the letter and the child without asking any questions, how will I explain myself to Duan Xiaowan when we meet in the afterlife?”

The man, once again, remained silent.

Madam Duan spread her sleeves and said in a more flirtatious tone, “Duan Xiaowan’s pregnancy was mysterious to begin with. I assumed the past could be left well enough alone after she was gone, but if you take this child away tonight…what if his father sends someone looking for him in the future? I wouldn’t be able to tell them anything. Isn’t that right?”

Still, the stranger said nothing.

Madam Duan smiled at him once more, conciliatory, then turned her gaze on Duan Ling. She beckoned him over, but Duan Ling shrank back instinctively and hid behind the man, clutching tightly at his robes.

“Ah.” Madam Duan scoffed lightly. “Still, my lord, you should offer me some explanation.”

Finally, he spoke: “I don’t have one. I only have money. Name your price.”

Madam Duan was speechless.

As the man fell into stern silence again, Madam Duan realized he would provide her nothing aside from payment for raising Duan Ling. He would not tell her who he was, regardless of any trouble it might cause for the Duan clan. The pair watched one another quietly for a short while, and then the man reached into his robes and withdrew several colorful banknotes.

“Four hundred taels,” she said, finally naming her price.

The man passed over the appropriate banknote.

Duan Ling watched the housekeeper accept the payment, and his breathing stuttered to a halt. He had no idea what this man wanted to do with him. He’d heard the maids say before that on bitter-cold winter nights, there were people who would come down the mountain and buy children to bring back as offerings to be eaten by monsters. A terrible fright rose within him.

“I’m not going!” he yelled. “No! No!”

Duan Ling turned to run, but only made it a single step before the maid grabbed him painfully by the ear and dragged him back.

“Let go of him,” the man said in his deep voice. He laid a hand on Duan Ling’s shoulder, and that hand felt like it weighed more than a thousand pounds. Duan Ling couldn’t move even when the housekeeper released him.

The housekeeper carried the banknote to Madam Duan, who frowned slightly when she accepted it.

“Keep the change,” the stranger told her. To Duan Ling, he said, “Let’s go.”

“I won’t! I won’t go!” Duan Ling cried.

Madam Duan still hadn’t lost her smile. “Where are you going in the dark? Why don’t you stay the night here and set off in the morning?”

Duan Ling wailed at the top of his lungs as the man looked down at him with a furrowed brow. “What’s wrong with you?” he asked.

“I don’t want to be fed to monsters! Don’t sell me! Don’t—” Duan Ling wriggled free and tried to dive under the table, but the man was much faster. He grabbed the boy and flicked several acupoints with his slender fingers, sealing Duan Ling’s voice; Duan Ling promptly collapsed. The man picked him up again, and under Madam Duan’s suspicious gaze, carried him outside.

“You don’t have to be afraid,” the man said quietly, holding Duan Ling under his arm. “I won’t feed you to any monsters.”

Outside the residence, the knife-cold wind blew snow flurries into their faces. Duan Ling’s throat seemed obstructed by an odd barrier of air—he opened his mouth but couldn’t make a sound.

“My name is Lang Junxia,” the man said. “Remember it: Lang Junxia.”

“Won—tons!” Lao-Wang called into the night from the stall to which he’d returned.

The wonton stall’s yellow lamp shone through the falling snow; Duan Ling’s empty stomach clenched as he gazed at it desperately. The man—Lang Junxia—came to a stop, paused, then set Duan Ling down and tossed a couple of copper coins into the bamboo tube at the front of the stall with a jingle.

Somehow, this simple action calmed Duan Ling. Who was this man, and why had he taken him from the Duan residence? Lang Junxia pressed on Duan Ling’s back to unseal some acupoints; his throat was suddenly free of obstruction. He was about to scream again when Lang Junxia shushed him. Duan Ling watched as the old man brought them a steaming bowl filled to the brim with meaty wontons, sesame seeds and crushed peanuts sprinkled on top. A small piece of fat was dissolved in the soup, giving off a tantalizing fragrance, and potherb mustard garnished the bowl.

“Eat,” Lang Junxia said.

Duan Ling immediately forgot everything else and grabbed the bowl, scarfing down the wontons despite how they scorched his tongue and throat. His hunger overcame his fear, and he kept his head lowered to wolf the whole meal down as quickly as he could. As he slurped a mouthful of soup, a fox-fur coat fell across his back.

When he had drunk every last drop from the bowl, he put down his chopsticks and sighed before turning around to look at Lang Junxia. The man’s complexion was tan, like a person in a painting, and his nose was tall, his eyes deeply set. The lights in the alley and the flying snow reflected in his pupils. The fall of his clothes hinted at an upright, strong figure, and his black outer robe was embroidered with ferocious monsters baring fangs and flashing claws. His fingers were long and beautiful, and he carried a shining sword at his waist like a hero in an opera.

Duan Ling had seen people return from the capital in splendor, riding high on their horses through the streets of Runan. From his hiding spot in the crowd, he’d watched the commotion, observing the young men dressed in silk and satin, flushed with their own success.

None of them had been as good-looking as this man—yet Duan Ling couldn’t have put into words what made him so handsome.

Suddenly he was incredibly frightened once more. Perhaps Lang Junxia was a monster turned man, who would soon bare his fangs and eat him alive. Lang Junxia, on the other hand, merely stared at him intently.

“Are you full?” he asked. “Do you want anything else to eat?”

Duan Ling didn’t dare answer. He was already planning his escape.

“If you’re full, let’s go.”

Lang Junxia reached his hand out to Duan Ling, but Duan Ling shied away fearfully. He looked over at Lao-Wang for help, but the old man wasn’t paying them any mind. Lang Junxia flipped his hand over and caught Duan Ling’s instead. Duan Ling didn’t dare struggle any further and obediently went along with him.

Back at the Duan clan household, a servant came forward to report: “Madam, the man brought the bastard to eat wontons in the alley.”

Madam Duan gathered her coat around her and blinked, unsettled. She called for the housekeeper. “Have someone follow them. Find out where he’s taking the child.”

Thousands of families had lit up their homes for the night in Runan. Duan Ling’s face had gone red from the cold, and his feet stung from walking barefoot in the slush as Lang Junxia led him through the streets. Only after they arrived at Diancui Pavilion in the center of the city did Lang Junxia finally notice that Duan Ling had no shoes. He frowned and picked him up, then whistled toward the building. A horse trotted out at his signal.

Lang Junxia settled Duan Ling atop the horse and wrapped his coat tighter around him. “Wait for me here. There’s something I need to attend to.”

Duan Ling looked down at him. Lang Junxia’s face was handsome, as if carved from jade, with gleaming, sharp eyes. Stray reed flowers still clung to his hair. Lang Junxia motioned for the boy to wait, then turned and disappeared into the night with a flare of his robes, like a falcon spreading its wings.

Thoughts ran wild in Duan Ling’s mind. Who was Lang Junxia really—and should he run now? But the horse was very tall, and he didn’t dare jump down for fear of breaking his legs or the horse kicking him. He debated whether he should leave his fate to this strange man or create it himself. In any case, where would he even run to? Right as he made up his mind to take the leap, however, a figure flashed around the corner of the alley.

Lang Junxia stepped into the stirrup and swung easily astride the horse. “Hup!” he cued the horse forward.

His mount’s hooves rang against the bluestone path as the horse pranced out from the alley and down the streets—ready to leave Runan behind on this dark and lonely night.

Duan Ling sat in front of Lang Junxia, smelling the damp odor rising from his own clothes. Surprisingly, Lang Junxia’s robes were dry, as if he’d sat before a fire, and smelled pleasantly of shaobing flatbread. There was a tiny burnt spot on the sleeve cuff of the hand holding the reins.

The spot hadn’t been burnt before. Where had Lang Junxia gone, and what had he done?

Duan Ling recalled another story. Legend had it that, during the last dynasty, some rogues were killed in a dispute and buried in the dark ravine outside the city. They’d rotted there for hundreds of years, waiting for children to pass by so they could take over their fresh, young bodies. Their shades would first take the form of humans, each undeniably handsome and skilled in martial arts—and then, after they’d found a victim, they would lure the child back to their grave, unmask their rotten face, suck away the child’s vital essence, and inhabit their body. The unlucky child, their body stolen, would thus lie in the grave for all eternity, while the corpse monster shifted into their skin and strutted back into the mortal world to live a good life.

Duan Ling couldn’t stop trembling. He desperately wanted to leap off the horse and run away, but the horse was simply too tall; he would probably break his legs if he jumped down.

Was Lang Junxia a corpse monster? Duan Ling’s head was spinning as he sat in the saddle, stiff with terror. If the corpse monster wanted to absorb his essence, should he lead the monster to someone else? No, he thought—he couldn’t harm others.

A man at the city gate opened it for Lang Junxia, and their horse cantered south along the official road through the snow. Realizing that they weren’t headed toward either the mass graves or the dark ravine, Duan Ling began to relax. The rhythmic, steady pace of the horse’s stride made him feel settled and sleepy, and gradually he dozed off, engulfed in Lang Junxia’s dry, refreshing scent. Two long ravines stretched across the landscape of his dreams, like a shadow play sweeping across a curtain.

The heavy snow was like a white sheet, the green peaks of the mountains like ink. The horse galloped across the wintry expanse like the stroke of a brush over paper.

Chapter 3

“TWO BOWLS of Laba rice porridge, please.”

Warmly glowing lights accompanied Lang Junxia’s voice. Duan Ling was so sleepy he couldn’t open his eyes; he rolled over dazedly as Lang Junxia patted him awake.

In the guest room of the inn they had stopped at, a server brought over two bowls, the porridge within thick with beans, dried fruit, and nuts. Lang Junxia handed one to Duan Ling, who scarfed his meal down again as his darting eyes stole glances at Lang Junxia.

“Still hungry?” Lang Junxia asked.

Duan Ling gave him a suspicious look. When Lang Junxia sat on the bed beside him, Duan Ling shrank nervously backward.

Lang Junxia had never cared for a child before, and seemed confused by Duan Ling. Lacking any candy to coax the boy with, after a moment’s consideration, he untied the jade pendant from around his waist and held it out to him. “You can have it.”

The jade arc was slightly translucent, like a piece of sugar brittle; Duan Ling didn’t dare reach for it. His gaze shifted from the jade pendant to Lang Junxia’s face.

“If you want it, take it,” Lang Junxia said.

The words were warm, but his voice held no emotion. With the jade held between his fingers, he stuck his hand out toward the boy. Duan Ling nervously accepted the pendant, poring over it intently, until finally his eyes lifted to Lang Junxia’s face again.

“Who are you?” Duan Ling asked—then, as if it had just occurred to him, he continued, “A-are you my father?”

Lang Junxia didn’t answer right away. Duan Ling had heard countless rumors about his father: Some said his father was a monster in the mountains; some said he was a beggar. Others said his father would come back for him one day—that Duan Ling was destined for wealth and nobility.

“No,” Lang Junxia said. “My apologies for disappointing you, but I am not.”

Duan Ling hadn’t really believed it himself, so this answer wasn’t particularly disappointing. Lang Junxia seemed to be mulling something over, but when he shook off his abstraction, he said nothing more except to bid Duan Ling to lie down. Lang Junxia pulled the blanket over him. “Go to sleep.”

The whistle of wind and snow echoed in Duan Ling’s ears. They had already traveled forty li from Runan, and Duan Ling was still covered in healing wounds; the instant he fell asleep, nightmares of being beaten started all over again. Sometimes his body twitched uncontrollably, or he whimpered and screamed, trembling the whole time.

At first Lang Junxia had lain down on a mat on the floor—but when he realized Duan Ling’s nightmares were never-ending, he slept beside him instead. Whenever Duan Ling reached his hand out, Lang Junxia covered it with his own, large and warm. Eventually, Duan Ling’s dreams seemed to settle, and he fell into restful sleep.

The following day, Lang Junxia requested hot water and gave Duan Ling a bath, washing his whole body clean. Duan Ling was so skinny his ribs showed through his skin, and old scars were scattered across his arms and legs. His older wounds hadn’t healed before new ones were laid over them, and the hot bathwater stung all his collected hurts. But Duan Ling paid the pain no mind; he was focused on playing with the jade arc in his hands.

“Did my father send you?” Duan Ling asked.

“Shh.” Lang Junxia held a finger to his lips. “Don’t ask me anything. I’ll tell you little by little. For now, if anyone asks, tell them that your surname is Duan and your father is named Duan Sheng. You and I are from the Duan family of Shangzi, and your father travels between the cities of Shangjing and Xichuan for business, so he entrusted you to your uncle’s household. Now that you’re older, your father sent me to bring you to Shangjing to study. Got it?”

Lang Junxia applied medicine to Duan Ling’s wounds, dressed him in an underrobe, and wrapped him in a slightly oversized coat lined with silky mink fur. He led him outside, sat him on the horse, and looked directly into his eyes. Although still unsure, Duan Ling returned Lang Junxia’s gaze for a long moment, then nodded.

“Repeat it back to me.”

“My father is Duan Sheng.”

Their steed galloped all the way to the riverbank, where Lang Junxia dismounted. At the crossing, he led the horse and carried Duan Ling across the frozen river.

“I came from the Duan family of Shangzi…” Duan Ling repeated.

“…to study in Shangjing.”

Lang Junxia lifted him into the saddle again, and Duan Ling swayed on the horse, drowsy.

Thousands of miles away, below Yubi Pass, Li Jianhong limped onward. He staggered more than he walked, his body a lurching collection of wounds and fractures. The only things he carried with him were the sword on his back and the red cord around his neck.

From that red cord hung a pendant of flawlessly clear white jade.

A gust of wind scoured away the dusting of snow on the jade, which seemed to glow warmly in the darkness. In a distant corner of the world, from another jade pendant, a powerful force called. Between them stood the Xianbei Mountains that the northern goshawks could not cross, and the frozen winter streams through which fish could not swim. But the force that called from the other side of those waters was binding—it was fate. The power drawing him forward despite his agonies was rooted in his very soul, flowing in his veins.

Through the howling blizzard, he heard something approaching. Was it a pack of wolves in the wilderness, or a whirlwind set to destroy the world?

“Skychaser!” Li Jianhong roared.

A pitch-black steed galloped toward him, its pure-white hooves frothing up clouds of snow. The warhorse’s whinny pierced the sky. Li Jianhong grabbed the reins and used all his remaining strength to swing himself onto the horse’s back.

“Go!” Li Jianhong shouted as he rode Skychaser into the blizzard.

Crossing river after river, Lang Junxia and Duan Ling headed north; as the temperature dropped, the number of people they encountered rose. Lang Junxia repeatedly warned Duan Ling to keep his past a secret. Once he had finally memorized the backstory Lang Junxia taught him, Lang Junxia entertained him with stories of Shangzi, amusing Duan Ling such that, little by little, he forgot his hurts and worries.

Like the wounds on his body, Duan Ling’s nightmares also healed slowly but steadily. The wounds on his back scabbed, and the scabs fell off. Only a few pale, soft scars remained by the time their long journey ended at the most opulent city Duan Ling had seen in his life.

Shangjing’s tall buildings reflected light like the sea, and the people’s luminous clothes and carriages flowed by, shining like river waves. The setting sun cast a ruddy light from the western side of the Xianbei Mountains, glowing warm over the surrounding wild expanse; the shining band of the river coursed around the city like a shimmering, ice-crusted belt.

The city towered in the twilight.

“We’re here,” Lang Junxia said.

Duan Ling was bundled tightly within his oversized coat; the journey had been much too cold. Held in Lang Junxia’s arms, seated on his horse, Duan Ling gazed at the distant rooftops of Shangjing. He squinted slightly, feeling warm inside despite the winter chill.

Nightfall arrived alongside them at the gates of Shangjing. The city was heavily guarded, and as Lang Junxia handed over his official documents, the guards eyed Duan Ling.

“Where are you from?” a guard asked.

Duan Ling stared at him, and the guard stared back.

“My father is Duan Sheng.” Duan Ling had his story well-memorized. “I’m from the Duan family in—”

The guard interrupted him to ask, “What’s the relationship between you two?”

Duan Ling looked at Lang Junxia. “His father and I are friends,” Lang Junxia replied.

The guard read the documents over and over again, then finally—reluctantly—let them through. The streets were brightly lit and piled with snow on either side; it was the end of the year, a season of festivities when drunk men clung to the lampposts and enjoyed their wine on the side of the road, when women entertainers played their instruments and sang for passersby in front of the railings. Even more people sat or lay down outside the boisterous pubs. Courtesans’ bold calls spilled into the night, and martial artists with swords belted at their waists stopped for a look. Filthy rich merchants, drunk beyond reckoning with pretty women in their arms, staggered down the street. One nearly upended a noodle stall. Carriages clanked as they sped down the icy roads, and at a carrier’s cry, another luxurious sedan was lifted high off the ground by its men, as if houses moved freely through the streets of Shangjing.

Galloping was banned on the main road, so Duan Ling sat alone on the horse’s back while Lang Junxia led it by the reins. The boy drank in the city sights with intense curiosity through the sliver of visibility allowed by his fur hat. Once they turned into an alley, Lang Junxia mounted the horse again and spurred it back up to speed, its hooves throwing snow into the air as they galloped down the narrow lane.

The music faded, left behind on the main streets, but the lights remained bright. Red lanterns hung on either side of the quiet alley, and the only sound was the crisp clacking of hooves on icy paving stones. The further down the side street they traveled, the more numerous and secluded the two-story houses flanking them became, with countless strings of lanterns layered and stacked overhead. Even the falling snow was consumed by their constant, warm light.

Upon their arrival at the alley’s back gate, Lang Junxia told Duan Ling, “Get down.”

A beggar sat beside the gate. Without so much as looking at him, Lang Junxia flicked several silver coins into his bowl, which clinked against one another at the bottom. Duan Ling turned his head to better see the beggar, curious, but Lang Junxia turned his head forward again, then patted the snow from his body and led him inside. Lang Junxia was clearly familiar with the place; they passed without assistance through an open-air pergola covered in snow and the central courtyard, accompanied by the distant thrumming of a zither, before turning toward a side wing.

After leading them into a room, Lang Junxia seemed to relax a little. “Sit. Are you hungry?”

Duan Ling shook his head. Lang Junxia settled him on the low table in front of the stove, then dropped to one knee. He removed Duan Ling’s fur-lined coat and the cap with its muffling ear flaps, dusted the snow from his boots, and sat down cross-legged before him. He looked up at Duan Ling with a hint of gentleness in his eyes, hidden so deeply it was there and gone again in a flash.

“Is this your home?” Duan Ling asked.

“This place is called Qionghua House,” Lang Junxia explained. “We’ll stay here for a few days before I take you to your new home.”

Duan Ling had taken Lang Junxia’s earlier Don’t ask me anything to heart, and rarely questioned the man during their journey. He kept his doubts hidden, like an alert, uneasy rabbit that appeared calm from the outside. Yet even without questions, Lang Junxia often explained things to him at his own pace.

“Are you cold?” Lang Junxia asked. He took Duan Ling’s chilled feet into his large, warm hands and rubbed them briefly before frowning. “Your body’s too weak.”

From behind Lang Junxia, a girl’s crisp voice called out, “I thought you were never coming back.”

Duan Ling raised his head. A beautiful girl in an embroidered jacket stood at the door, two serving girls trailing behind her.

“I had business to attend to,” Lang Junxia said without turning toward her. He untied Duan Ling’s belt, then turned and opened his travel pack, retrieving a dry change of outer robes for the boy and helping him into them. Only once he was shaking out the damp robe did he finally glance over at the girl, who took it as an invitation, stepping into the room and peering down at Duan Ling.

Her intense regard made Duan Ling uncomfortable, and his brows drew together. Before he could speak, she asked, “And who is this?”

Duan Ling sat up straighter, and his practiced litany flashed through his mind: My name is Duan Ling, and my father is Duan Sheng…

But before the words left his mouth, Lang Junxia answered for him. “This is Duan Ling.” He turned to Duan Ling and said, “This is Miss Ding.”

Remembering the manners Lang Junxia had taught him, Duan Ling cupped his hands toward her and looked her up and down. The girl Ding Zhi—who was as lovely as the angelica flower of her namesake—smiled and bowed to Duan Ling. “Hello, Duan-gongzi.”4

“Has the one from the Northern Court arrived yet?” Lang Junxia asked offhandedly.

“The military report from the border said the general hasn’t returned in three months due to continued fighting below Jiangjun Ridge,” Ding Zhi said as she took her seat beside them. She said over her shoulder to the serving girls, “Bring some snacks for Duan-gongzi.”

Ding Zhi picked up the teapot, poured a cup, and handed it to Lang Junxia. He accepted the offering and took a sip, then said, “Ginger tea—it’ll drive away the cold,” before handing the cup to Duan Ling.

Throughout their journey, Lang Junxia would always taste any food or drink first to confirm it was good before giving it to Duan Ling; the boy had become used to it. But as he drank his tea, he caught a strange look in Ding Zhi’s eyes, which had narrowed slightly as her stare intensified.

The maid returned with a selection of pastries Duan Ling had never seen—or even heard of—before. Lang Junxia seemed to anticipate his excitement and reminded him, “Eat slowly. There’ll be dinner later.”

Over the course of their journey, Lang Junxia had admonished Duan Ling repeatedly that no matter what he was eating, he shouldn’t cram his meals down as fast as possible. This went against all Duan Ling’s instincts, but he had to listen to Lang Junxia—and slowly, he realized that no one was going to snatch his food away anymore. He chose a pastry, held it gently in his hands, and nibbled without rushing. Ding Zhi sat quietly, as if nothing happening in the room had anything to do with her. This continued until the maids brought two food boxes and laid them on the low table. Lang Junxia urged Duan Ling to take a seat, indicating that he should eat, and only then did Ding Zhi kneel down beside Lang Junxia with the pot of warmed wine to pour for him.

Lang Junxia blocked the cup with his fingers. “Drinking will cause trouble.”

“This is the Liangnan Daqu liquor sent as tribute last month,” Ding Zhi said. “You don’t want to try it? Madam set it aside just for you, whenever you came back.”

Lang Junxia didn’t reject the liquor a second time; Ding Zhi poured him a cup, and he drank. She poured another, and he drank again. She poured a third cup—after Lang Junxia finished that one, he turned the cup over and placed it rim-down on the table.

Duan Ling watched attentively the whole time.

Ding Zhi moved to pour a cup for him as well, but Lang Junxia reached two fingers out and caught her sleeve. “He’s not allowed to drink,” Lang Junxia said.

The girl gave him an apologetic smile.

Duan Ling did want to drink—but his desire to be obedient for Lang Junxia superseded his desire for alcohol. While he patiently ate his dinner, Duan Ling continued to wonder where he’d been brought and what the relationship was between Lang Junxia and the girl. He snuck peek after peek at them, his uncertainty flickering across his face. He wished they would talk a little more, just so he could listen.

Lang Junxia still hadn’t told Duan Ling why he’d brought him here. Did Miss Ding know—was that why she didn’t ask where he was from?

Miss Ding, too, stole glances at Duan Ling from time to time, as if doing calculations in her head. When Duan Ling set down his chopsticks, she finally spoke, and his heart jumped into his throat even though all she asked was, “Did those dishes suit your taste?”

“I’ve never had them before, but they were good,” Duan Ling answered.

Ding Zhi laughed. As a servant girl cleared the food boxes away, she said, “I should take my leave.”

“Go, then,” Lang Junxia said.

“How long are you in Shangjing for this time?” Ding Zhi asked.

“I’ll be staying permanently,” he replied.

Ding Zhi’s eyes seemed to brighten. With a slight smile, she said to the serving girl, “Accompany my lord and Duan-gongzi to the side courtyard.”

The maid led the way with a lamp; Lang Junxia wrapped Duan Ling in his own fur-lined cloak, scooped him into his arms, and carried him through the corridors until they arrived at another courtyard—this one filled with rustling bamboo. Duan Ling heard a cup shatter across the courtyard in a different building, followed by a man’s drunken tirade.

“Don’t look around,” Lang Junxia cautioned Duan Ling. He carried him into the room and glanced back at the maid who’d followed them inside. “There’s no need to wait on us.”

She bowed and left. The room held a gentle fragrance, and though there was no brazier, the air was warm. A furnace under the floors provided heat, and smoke billowed through the underground spaces.

Lang Junxia had Duan Ling rinse his mouth as he prepared for sleep. Lying on the bed in his underrobes, Duan Ling felt awfully drowsy. Lang Junxia settled on the bed beside him. “Tomorrow I’ll take you to look around.”

“Really?” Duan Ling exclaimed with a brief burst of energy.

“Yes,” Lang Junxia said. “I’m going to sleep now. I’ll be in the next room.”

At this, Duan Ling grasped forlornly at his sleeve. Lang Junxia gave him a confused look, but with a moment of thought, he understood—Duan Ling wanted him to sleep here.

Since they’d left Runan, Duan Ling hadn’t been separated from Lang Junxia for a moment. They ate together in the morning and they slept together at night. Now that Lang Junxia planned to leave him by himself, of course Duan Ling would be frightened.

“Then…” Lang Junxia hesitated. “Never mind. I’ll stay with you.”

Lang Junxia shrugged off his underrobe, baring his sturdy, muscular torso, and lay down beside Duan Ling, draping an arm over the boy. Duan Ling nestled his head in the crook of Lang Junxia’s strong arm and chest; as soon as he did so, his eyelids grew heavier, and he fell easily into sleep. Lang Junxia’s skin carried the pleasant scent of a man, and Duan Ling had already become accustomed to smelling it on his outer robe and his body. He felt he would no longer suffer any nightmares, so long as Lang Junxia held him.

But the day had been so full that his mind was overcrowded with new, complicated information; his dreams leapt and spun, too numerous for the span of a single night. During the second half of the night, the snow stopped falling and the world settled into an unusual silence. Duan Ling somehow found himself awake, disoriented from the countless dreams flooding over him, but when he turned over, he found only a still-warm cover.

Lang Junxia had disappeared, but his body temperature lingered. The absence made Duan Ling nervous. Unsure of what to do, he tiptoed out of bed and opened the door. Lights glowed from the next room over. Duan Ling padded barefoot down the corridor, then raised himself onto his toes to peek through the window.

The room was open and bright, with curtains draped across one side. Lang Junxia was in the midst of undressing, his back turned to the window.

His collar was fastened at the jut of his throat, and he undid it slowly before hanging his brocade robe on a nearby clothing rack. As his clothes slid down his body, a broad back, defined waistline, and well-formed buttocks were revealed, inch by inch. His naked male body was on full display, as lean and strong as a warhorse, and when he turned to the side, Duan Ling saw his virile erection.

Duan Ling’s breath caught, his heart pounding wildly. He took an involuntary step backward and knocked over a flower stand.

“Who’s there?” Lang Junxia called as he turned toward the door.

Chapter 4

STARTLED, Duan Ling scurried away.

Lang Junxia hastily threw on his outer robe and left the room barefoot, emerging into the corridor just as the door to Duan Ling’s room slid closed with a soft thud.

Lang Junxia followed him inside. Duan Ling had already burrowed back into his blankets and was pretending to sleep; Lang Junxia didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. He went to the washbasin and wrung out the wet cloth, then dropped his outer robe to the ground and began to wipe down his once-again nude body. Duan Ling cracked his eyes open just enough to see him across the room. Lang Junxia turned slightly, and, as if to settle his restless emotions, pressed the cold, wet cloth over his erection, attempting to force himself soft.

A silhouette appeared at the window.

“I’m going to sleep; I won’t be coming over,” Lang Junxia said in a low voice.

Footsteps retreated down the corridor, and Duan Ling rolled over toward the wall. Moments later, Lang Junxia put on his underpants and slipped into bed, his chest pressed to Duan Ling’s back. Duan Ling squirmed his way around, and Lang Junxia lifted his arm so he could once more rest his head on his shoulder. Comfortable again, Duan Ling fell quickly back to sleep.

Lang Junxia’s firm muscles, warmth, and pleasant scent transported the dreaming Duan Ling to a southern winter, where he was embraced by a fiery sun.

The same night in Xichuan, it drizzled steadily, and the rain soaked everything.

Candlelight cast the shadows of latticed windows across the outdoor corridor. Two figures walked slowly through the shadows, followed closely by a pair of guards.

“He escaped, even though he was surrounded by twenty thousand soldiers,” said one of the men.

The other replied, “Don’t worry. I’ve set up an impenetrable encirclement, blocking Liang Prefecture and the northeast roads. Unless he grows wings, he won’t be able to cross the Xianbei Mountains.”

“I told you handing him over to those people wasn’t a good idea. He fought beyond the Great Wall for many years; he’s too familiar with the terrain. Once he enters the forest, we’ll never see him again!”

“We’ve made our move. There’s no turning back now. The emperor has grown old; he ignores government affairs. And with the fourth prince so sickly… Even if he were to return, we could still charge him with neglect of duty. Don’t tell me you’ve lost your nerve, General Zhao?”

“You—!”

This General Zhao, as he was called, wore a military uniform; his name was Zhao Kui, and he was a cornerstone of Southern Chen’s government as well as the commander in chief of their military. The man walking with him wore an official’s purple robe. He was a senior minister of the first rank, a man of significant status. The candlelight threw their shadows onto the stone spirit screen outside the corridor; after the brief exchange, they both fell silent. Behind them, the two guards followed with arms folded, unspeaking.

The guard on the left sported a White Tiger tattoo on his neck and wore a bamboo hat pulled low to cover the upper half of his face. The curve of his mouth peeked out as if he was smiling.

The guard on the right was tall, at least six feet, and every part of his body was hidden save for his eyes. He wore gloves and a cloak, and his face was covered by a mask. Above it, his gaze, sharp and sinister, swept over his surroundings—an automatic awareness.

“We must send someone to intercept him immediately,” Zhao Kui said, his voice clipped. “He’s in hiding while we are out in the open. If we delay too long, something could change, and that will mean more trouble for us.”

“We can’t mobilize troops beyond Yubi Pass. All we can do now is wait for him to show himself,” the official replied.

Zhao Kui sighed. “If he takes refuge in Liao and returns with troops behind him, I’m afraid it will complicate things.”

“The emperor of Liao will not lend him troops,” the official said. “We have already settled upon a plan with the Southern Court. He will not survive the journey to Shangjing.”

“You think too little of him.” Zhao Kui turned to face the dark, rain-soaked courtyard, the gray hair at his temples damp as he shifted toward the official and continued, “There’s a mongrel working for Li Jianhong, a man of mixed Xianbei and Han descent. I don’t know who he is or where he came from; I suspect he’s the one you’ve been looking for all this time. That Xianbei mutt’s movements are enigmatic, and nobody knows his name. He was the last pawn Li Jianhong had hidden.”

“If he’s as you describe, I imagine Wu Du and Changliu-jun here would like to meet him. After all, there aren’t many in this world worthy of being their rival,” the official said. He turned to the guards: “Have you ever heard of him?”

The masked guard, Changliu-jun, was first to reply. “I know of him, though I don’t know his name. Some call him the Nameless Assassin. He has a history of misdeeds and a reputation for being difficult to control; I’d be surprised if he obeys Li Jianhong’s orders.”

“What misdeeds?” Zhao Kui asked.

“He betrayed his sect, killed his master and his father, and turned on his fellow disciples. He is ruthlessly cruel, devoid of humanity, and never spares anyone,” Changliu-jun said. “If you’ve heard the phrase ‘the Chilling Edge seals throats in one strike’—that’s him.”

“That doesn’t seem out of the ordinary for an assassin,” the official said.

“A fatal strike to the throat,” Changliu-jun said in a deep voice. “That means he doesn’t listen to anyone’s explanations. An assassin’s duty is to kill, but not without cause; even if he killed the wrong person, the Nameless Assassin wouldn’t so much as blink.”

“But if I remember correctly,” the official said, “Li Jianhong still carries the Guardian of the Realm. As long as he holds this blade, this assassin must obey him.”

“Even if Li Jianhong has the Guardian, he must be able to bear its weight to command others,” Changliu-jun replied.

“Forget it,” Zhao Kui replied. The silence stretched until he said at last, “Wu Du.”

The guard in the bamboo hat murmured in acknowledgment.

“Set out tonight,” Zhao Kui said. “Don’t stop until you locate Li Jianhong. When you find him, wait to act—I will send someone to you. After this mission is complete, bring his sword and his head to me.”

The corner of Wu Du’s mouth lifted slightly. He cupped his hands, bowed, and was gone.

A short time later, a carriage rattled out of the alley beyond the back gate of the general’s estate. The wet stone of the road reflected distant lights.

“Have you seen that man’s blade, Chilling Edge, before?” the official asked from within the carriage.

“All those who have seen Chilling Edge are dead,” Changliu-jun replied from the driver’s seat. He seemed to consider saying more—then he cracked his whip and turned back toward the road.

“From what you’ve seen…” The official reclined on the carriage’s brocade couch and asked, casually, “How does Wu Du compare to this Nameless Assassin?”

“Wu Du has concerns, but the Nameless Assassin has none,” Changliu-jun replied. “Wu Du is too competitive, and he hates losing. The Nameless Assassin has nothing to lose.”

“Nothing to lose?” the official repeated.

“Only those with no one and nothing to lose are worthy of being assassins,” Changliu-jun said calmly. “If you intend to take a life, you must sacrifice your own first. But once love enters the picture, an assassin will begin to cherish his life—he’ll be afraid to die, and then he will be defeated. It’s said the Nameless Assassin has no family, and he doesn’t kill for fame or reward. Perhaps killing is just a hobby for him. Compared to Wu Du, he would be at a slight advantage.”

“And what about between you and Wu Du?” the official asked.

“I hope to exchange blows with him at least once.”

“A pity you will never have the opportunity,” the official said elegantly.

Changliu-jun did not reply.

“And what about between you and Li Jianhong?” the man asked, his tone still casual.

“Whoa!” Changliu-jun called to the horses. When the carriage came to a halt, he lifted the curtain to allow the official to step down. Hanging outside the estate where they’d stopped was a lantern with a surname printed on it: Mu.

They’d arrived at the residence of the prime minister of Southern Chen—Mu Kuangda.

“If I, Wu Du, the Nameless Assassin, and Zheng Yan were to band together,” the masked man replied, returning to the prime minister’s earlier question, “then we might be a match for His Highness the third prince.”

Under the bright morning sun, snowy Shangjing looked like a gilded city—and Qionghua House, a paradise. A servant girl brought breakfast and said, “My lord, Madam is waiting to speak with you after your meal.”

“Tell her not to wait,” Lang Junxia replied. “I have business to attend to this morning; I’ll be on my way after breakfast. Please send her my thanks.”

When the servant had gone, Duan Ling asked, “Are we going out?”

Lang Junxia nodded. “Just don’t speak too much while we’re outside.”

Duan Ling agreed that he wouldn’t. He realized he had probably interrupted Lang Junxia the night before, but as he didn’t know what his guardian had been doing in the other room, he didn’t dare bring it up. Fortunately, Lang Junxia seemed to have forgotten all about it. After breakfast, he and Duan Ling left through the back alley once more.

A carriage waited outside. The curtains were lifted, revealing Ding Zhi’s lovely face. “You’ve only stayed one night. Where are you going now? Didn’t you say you wouldn’t leave again? Come ride with me.”

Lang Junxia held Duan Ling’s hand, hesitating in the face of her invitation, but Duan Ling pulled at him—wanting just as much to be on their way.

“We have business elsewhere,” Lang Junxia said. “I wouldn’t want to intrude.”

Ding Zhi gave up, unable to sway him, and Lang Junxia took Duan Ling to the city center. The sights he saw along the way were dizzying in their grandness. Shangjing was a hub of trade for the north; forty-one Hu tribes from three different cities beyond the Great Wall all traveled to Shangjing to buy and sell their wares. Adding to the bustle was a large party of diplomatic envoys from Southern Chen, come to congratulate the empress dowager of Liao on her upcoming birthday. A dazzling array of items filled the market stalls: sugar figurines, antique treasures, precious medicinal herbs, hairpins, cosmetics, and much more. Duan Ling wanted to eat everything he saw, but the donkey-meat rolls he’d previously coveted in Runan were what he most wished to taste.

Lang Junxia led Duan Ling to a clothier and ordered the boy two sets of new robes, then found a calligraphy stall and requested the four treasures of the study—inkstone, ink, brush, and paper.

“Do you know how to write?” Duan Ling asked him.

The shopkeeper brought out an inkstone from Duan Prefecture, an ink stick from Hui Prefecture, an ink brush from Hu Prefecture, and fine paper from Xuan Prefecture.

“These are for you,” Lang Junxia said. “You have to learn how to read and write before it’s too late.”

“You have a good eye, Gongzi.” The shopkeeper grinned. “These are quality items from the merchants up north who came through only two years ago. The paper hasn’t fully arrived though; if you want twelve stacks, I’ll need to go collect them from another store.”

“We Khitan aren’t so picky,” Lang Junxia said with a casual air. “It’s just for good luck. No need to go now; please just deliver it to Ming Academy before the sun sets tomorrow.”

“This is too expensive,” Duan Ling said, feeling a twinge at how much Lang Junxia had spent.

“Be diligent in your studies, and success and glory will follow,” Lang Junxia replied. “The ability to read and write is a priceless treasure.”

“Am I going to school?” Duan Ling asked.

When he had lived in Runan, he had been jealous of the children who attended school. He’d never thought he would be able to do so, and he was overwhelmed by gratitude. He stopped in place, gazing up at Lang Junxia.

“What’s wrong?” Lang Junxia asked.

Duan Ling’s emotions were hard to put into words. “How am I to repay you?”

Lang Junxia looked back at Duan Ling with both pity and kindness. After a moment, he forced a smile and answered seriously, “Going to school and studying are merely what you should be doing. You don’t need to repay me. In the future, there will be no shortage of people you will repay instead.”

After buying his supplies for school—and eating plenty of food in between—Duan Ling received a hand warmer and an embroidered cloth pouch from Lang Junxia. He placed Duan Ling’s jade pendant inside the bag, then looped its red string over his neck and tucked the pouch into his robes next to his underclothes.

“Remember,” Lang Junxia warned. “You can’t ever lose this.”

Lang Junxia led Duan Ling away from the bustling city center and turned onto a long, quiet street. An old building with white walls and a black roof, snow piled in the dips of the tiles, faced the street, simple yet elegant. Snowy pine and cypress trees stood in the courtyard, and the sound of children’s voices carried into the street.

Duan Ling perked up when he heard it. Since he’d started traveling with Lang Junxia, he hadn’t seen any kids around his age. Unlike when he used to run around in the mud in Runan, he’d been well-behaved the entire journey; he wondered what the children in Shangjing did for fun.

Lang Junxia entered the courtyard, and Duan Ling followed. It had been swept clean of snow, and three boys, each nearly a head taller than him, stood around ten steps away. The boys were throwing arrows into a nearby pot. When they heard newcomers approaching, they looked up and saw Duan Ling, who nervously edged closer to Lang Junxia.

Without pausing, Lang Junxia walked on to the inner hall, where an old man with a head of white hair and a white beard sat drinking tea.

“Wait here for a bit,” Lang Junxia said.

Duan Ling, wearing one of his new robes—this one an indigo blue—stepped to the side of the corridor to wait while Lang Junxia entered the room on his own. He could hear low voices from inside. After a distracted moment, he spotted another young man emerging from behind a courtyard pillar; he stood in front of the school’s large bronze bell to observe Duan Ling. Gradually, several more children around eight or nine years old gathered in the courtyard, all of them staring at Duan Ling and murmuring among themselves. One moved as if to come speak to him, but the tallest boy stopped him and stepped forward under the bell.

“Who are you?” the tall boy asked.

Inside his own head, Duan Ling answered, My name is Duan Ling, and my father is Duan Sheng… But he didn’t say anything aloud. He had a feeling these boys were looking for trouble. Supposing that Duan Ling was shy, the other children laughed, and though he didn’t know what exactly they were laughing at, it upset him nonetheless.

The tall boy came forward. He was holding an iron rod, and he tapped it against his opposite palm. “Where are you from?” he asked.

When Duan Ling tried to back away, the boy set a hand on his shoulder and yanked Duan Ling toward him. He pressed the iron rod beneath Duan Ling’s chin, tipping his head back slightly, and teased, “How old are you, anyway?”

Duan Ling wished he could shake him off, but instead he stood frozen for a long beat. When he finally pushed the young man away, he didn’t dare flee—Lang Junxia told him to stay put. The other boy was a full head taller than Duan Ling and dressed in the northern style, in a coat lined with wolf fur and a fox-tail hat. He had black eyes with a hint of star-blue, and his skin was a healthy brown. Standing before Duan Ling, he looked like a wolf cub on the cusp of gangly adolescence.

“Huh,” the tall boy said, reaching for the red string around Duan Ling’s neck. “What’s this?”

Duan Ling dodged his hand.

“Come here.” He had guessed by now that Duan Ling was holding back; it felt as if he was punching cotton, all soft give—and that was boring. He patted Duan Ling’s face. “I asked you a question. Does your mouth work?”

Duan Ling gazed at the tall boy with fierce eyes, hands balling into fists. In the other boy’s estimation, Duan Ling was a spoiled little dandy from a rich family; surely he’d be crying for mercy after a single blow. But before he hit him, he wanted to tease him just a little more.

“Seriously, what is it?” the tall boy repeated, grabbing the cord around Duan Ling’s neck again. He leaned close to Duan Ling’s ear, reaching to pull the cloth pouch free, and whispered, “Was the man who went in just now your father, or your brother? Or is he a little househusband your family raised for you to marry? Do you think he’s bowing and begging the headmaster?”

The gathered children began to laugh again. Duan Ling, afraid the pouch holding his pendant would tear, trailed along as the boy yanked him, holding tightly to the red string.

“Hup!” the tall boy commanded, leading him by the neck. “Look, you’re a donkey!”

The children laughed louder, and Duan Ling’s face flushed hot. Before the boy could say another word, Duan Ling’s fist flew into his field of vision, followed immediately by the blinding pain of a broken nose. The force of the blow knocked the boy right onto his back.

Chaos ensued. Nose bleeding freely, the tall boy rushed for Duan Ling as if to lift him. Duan Ling bent at the knees and tackled his opponent, arms around his waist. The impact threw them both from the corridor into the garden. The children cheered raucously and formed a loose circle to watch them wrestling in the snow.

Duan Ling took a punch to the face, followed by a solid kick to the chest that put him flat on his back, seeing stars. The tall boy jumped astride his chest and began beating him, the blood from his broken nose pouring down on Duan Ling’s face and neck. Duan Ling’s vision went dark beneath his fists. He gathered enough strength to grab the other boy’s ankle and yanked, throwing him off to one side.

Like a mad dog, Duan Ling pounced and bit down hard on the boy’s hand, shocking the circle of spectators. The boy screamed in pain, grabbed Duan Ling by the collar, and slammed his head against the bronze bell.

With a resonant dong, Duan Ling collapsed to the ground, his whole head buzzing.

Chapter 5

“STOP IT! STOP IT, NOW!” a harried voice cried.

The noise had finally caught Lang Junxia’s attention, and he rushed into the courtyard like a gale of wind. The headmaster was right behind him, bellowing, “Stop!”

The children immediately scattered, fleeing behind the wall. The tall boy tried to make a break for it too, but only took a few steps before the headmaster stormed over and grabbed him. Lang Junxia paled at the sight of Duan Ling sprawled on the ground; he hurriedly picked him up to check his injuries.

“Why didn’t you call for someone?!” Lang Junxia was furious.

Duan Ling’s stubbornness was astonishing. If he’d shouted, Lang Junxia would have realized something was wrong, yet he’d remained silent throughout. Lang Junxia had assumed the children were only being so noisy because they were playing with a ball.

Duan Ling’s left eye had begun to swell. He looked pitiable, but gave Lang Junxia a small smile.

An hour later, Lang Junxia had cleaned the blood and dirt from Duan Ling’s face, hands, and robes as best he could.

“Serve the headmaster some tea,” Lang Junxia ordered. “Go.”

Duan Ling had just been beaten up; his hands shook around the teacup, which clinked and rattled against the lid.

“If you intend to join my Ming Academy, you’ll have to learn to control that temper of yours,” the headmaster said evenly. “And if you can’t relinquish this violence, I will show you a path. Head to the Northern Court, and you’ll find your place there.”

The headmaster gazed steadily at Duan Ling, but didn’t take the tea he offered. Duan Ling held the cup for a while, unsure what he should say or do. At last, since the headmaster wouldn’t accept it, he set the teacup on the table, accidentally splashing tea onto the headmaster’s sleeves in the process.

The old man’s expression darkened immediately; he barked, “How dare you!”

“Headmaster.” Lang Junxia hastily dropped to one knee. “I failed to teach him properly; he doesn’t understand the rules.”

Duan Ling had suffered enough humiliation today already; the other boy’s contemptuous words still rang in his ears. He pulled at Lang Junxia. “Get up.”

But in a rare display of upset, Lang Junxia commanded Duan Ling, “Kneel! Kneel right now!”

Duan Ling had no choice; he knelt. The sight seemed to mollify the headmaster slightly. He said coolly, “If he doesn’t understand the rules, then teach him properly before you bring him back. Whether an official’s child or the prince of a nation, no student can say that they don’t know and obey the rules here!”

Lang Junxia remained silent, and so did Duan Ling. The headmaster’s mouth had gone dry from speaking, so he finally drank some of the tea Duan Ling had served him. “Every child who attends this school is treated equally. If you fight again, you will be expelled.”

“Thank you, Headmaster,” Lang Junxia said with relief.

He made Duan Ling bow three times, which Duan Ling did with some reluctance, before leading him away from the headmaster’s rooms.

Passing through the front courtyard, they saw the tall boy kneeling in front of the wall, reflecting on his error. Duan Ling glanced over at him, and the young man turned his head and stared right back; both their eyes were filled with resentment.

The pair returned to Qionghua House, where Lang Junxia began applying medicine to Duan Ling’s face. He frowned. “Why didn’t you say anything, or call for help, instead of fighting?”

“He hit me first,” Duan Ling said.

“I’m not blaming you,” Lang Junxia replied as he dampened the towel. “But you couldn’t have beaten him. Why didn’t you run?”

“Oh,” was all Duan Ling could think to say.

“If someone provokes you again, you need to think carefully before you act,” Lang Junxia continued patiently. “If you can beat them, then fight. If you can’t, run away, and I’ll get even with them later. You can’t risk your life in a fight. Understand?”

“Okay,” Duan Ling said. For a moment, the room was quiet. Then Duan Ling asked, “Do you know how to fight? Teach me.”

Lang Junxia put the towel down and silently gazed at Duan Ling. Finally, he said, “One day, there will be many who will mock you—and a great many more who will want to kill you. Even if you learn to fight, are you going to kill them each one by one?”

Duan Ling didn’t really understand, and looked at Lang Junxia in confusion.

“You’re to learn how to read, and you’re to learn the ways of the world. With these, in the future, there will be millions of methods for killing. How long would it take using only your fists? If you want revenge, study hard.”

Another brief silence fell between them.

“Do you understand?” Lang Junxia asked. Duan Ling didn’t—not really—but he nodded anyway. Lang Junxia tapped the back of his hand. “Never repeat what you did today.”

Once again, all Duan Ling said was, “Oh.”

“You’ll move into the academy tonight,” Lang Junxia said. “I’ll take you later this evening. You can buy or borrow whatever else you might need.”

Duan Ling’s heart lurched in his chest. Lang Junxia was all he had. Nobody had ever treated him so well in his life; it was as if he’d finally found his proper place—and now they had to separate?

“But what about you?” Duan Ling asked.

“I have other matters to attend to,” Lang Junxia said. “I’ve already discussed the schedule with the headmaster: I’ll pick you up from school on the first and fifteenth of the month, and you’ll be given two days’ holiday. I’ll review your homework, and if you’ve done everything, I’ll take you out to have fun.”

“I won’t go!” Duan Ling blurted out.

Lang Junxia stopped what he was doing. His eyes met Duan Ling’s, a deeply serious expression on his face. Though he said nothing, his aura pressed on Duan Ling—an aura of absolute authority.

Duan Ling hung his head in defeat, holding back tears.

“You’re a good boy, and you’ll do great things in the future,” Lang Junxia said, calm and steady. “After leaving Runan and Shangjing…there will be no more hardships for you. Even if some arise, they won’t compare to the past. You’re just going off to study; what’s there to cry over?”

Lang Junxia watched Duan Ling’s expression as he spoke, slightly confused, as if he couldn’t understand the boy’s fear and sadness. Throughout their journey he’d learned and thought many things about Duan Ling, but still this child managed to surprise him. He might be naughty at times, but he was never unruly in front of Lang Junxia. Compared to spending years in a dark woodshed in Runan, Lang Junxia imagined that the world Duan Ling was now entering would be peaceful and comfortable. He was only going to school, so why did he look like he was being sent into the wolf’s den? Duan Ling’s disobedience seemed merely a child’s whim to him—when nobody pampered the boy, he was like a half-withered grass, but once someone paid him attention, he became spoiled.

After much consideration, the only bit of wisdom Lang Junxia could think to impart to him was this: “Only those who endure hardship can become truly great.”

In the evening, snow fell again. Duan Ling was no longer interested in attending school, but he didn’t have a choice. He felt as if nobody had ever asked him what he wanted since the day he was born. Lang Junxia was kind on the outside, but his insides were steel-solid; he spoke sparingly, but once someone defied him, his aura shifted and he became like a wolf opening its eyes in the quiet, dark night.

The second Duan Ling even thought of disobeying, that powerful aura would rear up, smothering his soul under its weight until he gave in. Lang Junxia was unbudging on both the big and small matters of everyday life.

The next morning, Lang Junxia bought Duan Ling a few last daily necessities, then sealed and delivered the money for tuition to Ming Academy. He entered a school building on the fringes of the complex from the east.

“I asked Ding Zhi to have a friend look after you for a bit,” Lang Junxia said. “High-ranking officials often drink at Qionghua House. She’ll have someone warn that Mongol boy you fought with. I doubt he’ll come looking for trouble again.”

Servants had cleaned and lit a fire in the courtyard. The stove stood beside one of the walls, and though it wasn’t quite as warm as Qionghua House, it was still comfortably toasty. Duan Ling was already familiar with the dining hall. Two meals were served per day, and students should gather for them at the toll of the bell. He took the bowl and chopsticks Lang Junxia had bought for him and followed along to his new room.

Duan Ling sat at the little table, and Lang Junxia bent over to make the bed for him.

“You must keep the jade pendant with you always,” Lang Junxia reminded him for the umpteenth time. “Hide it under your pillow when you sleep, and wear it when you’re awake. Don’t lose it.”

Duan Ling said nothing, but his eyes were red at the rims. Lang Junxia pretended not to see.

The four treasures of the study had also arrived, and the Ming Academy staff accepted them for him. After he finished making the bed, Lang Junxia settled down across from Duan Ling. He was the only one staying in this remote courtyard, and as the sky darkened, servants came by to light the lamps. Under their warm glow, Lang Junxia sat with the still, quiet beauty of a sculpture, while Duan Ling simply sat in a daze.

Only once the school bell had rung three times did Lang Junxia get to his feet. “Go, it’s time for your meal. Don’t forget your bowl and chopsticks.”

Picking them up as instructed, Duan Ling wordlessly followed Lang Junxia back toward the dining hall. When they reached the footpath out front, Lang Junxia said, “I’m leaving now. I’ll come and pick you up on the first of next month.”

Duan Ling stood stock-still.

“Go on and eat,” Lang Junxia urged him. “Remember what I told you. When the bell rings, you must get up—early and without delay. For the first few days, a servant will guide you.”

Lang Junxia motioned Duan Ling up the path to the dining hall, but the boy didn’t move. They stood facing one another in a painful silence. Duan Ling, his new bowl and chopsticks in hand, opened his mouth as if to finally speak, but nothing came out.

In the end, it was Lang Junxia who turned away first; as soon as he began walking down the path, Duan Ling followed.

Lang Junxia glanced back at him, then quickened his steps, not wanting to stay any longer. Duan Ling chased him all the way to the back gate of the school, still holding his bowl, where the guard stopped him. Duan Ling stood just inside the gate, tears welling in his eyes as he gazed after Lang Junxia.

The sight made Lang Junxia’s head hurt. He turned again and said, “Go back! Or I’m not coming on the first of the month!”

Duan Ling stood, forlorn, on the other side of the gate. Lang Junxia felt for him, but knew he shouldn’t stay longer. With a few quick strides, he disappeared from sight.

The old man guarding the gate said comfortingly, “Study hard and learn, so you can become an official in the future. Go back, now.”

Duan Ling turned away, wiping his tears as he walked. The yellow lanterns of the school were lit against the evening darkness. After a few turns, he no longer recognized the way back and sat down, dejected, in the corridor.

Fortunately, the headmaster and a few of the teachers soon passed by where he was seated, crying, in the heavy snow.

“What are you doing there?!” The headmaster didn’t recognize Duan Ling at first, and angrily continued, “Why are you so weak and sniveling? What kind of behavior is this?!”

Duan Ling jumped to his feet, afraid of upsetting the headmaster again and making Lang Junxia angry too.

“Which family is this child from?” a teacher asked.

The headmaster studied Duan Ling for a moment before he remembered. “Ah—the boy who started fighting the minute he arrived. You weren’t so delicate when you were brawling, young man. Follow the teachers.”

Duan Ling followed the group of teachers all the way to the dining hall. By the time he arrived, the other students had almost finished, and the table they shared was a mess of half-eaten dishes. The servants brought Duan Ling his meal, which he polished off in a flash before setting his bowl and chopsticks down. Another servant took them away to be washed; his name had been engraved on both so they wouldn’t be lost.

Duan Ling returned to his room for the night, alone.

From somewhere nearby, he could hear the sound of a flute.

The instrument’s melodic voice floated by, like a parting song from the dusky city of Runan. Everything felt dreamlike—in the month since Duan Ling had come to the north, he’d thought he’d forgotten all about the Duan clan. Lang Junxia, that steady presence by his side, was evidence of the start of his new life.

But now, alone in the quiet dimness of his school room, listening to the sound of crackling firewood beneath his window and the faraway flute, Duan Ling didn’t dare close his eyes. He was afraid that when he opened them, he would be back in the dark woodshed, bruised and fearful. The nightmare seemed to wait in the shadows of the room, ready for him to fall asleep so it could whisk him back to Runan, thousands of li away, the moment he lost consciousness.

Yet strangely, the flute’s song held the nightmare at bay, producing countless images in his mind’s eye of floating peach blossoms to accompany him to sleep.

Lang Junxia stood under the eaves, his cloak blanketed in snow.

After waiting silently for a while, he fished out a letter from his robes—never delivered—and read it with a frown.

Xiaowan:

Greet this letter as if you greeted me. As proof of its authenticity, my messenger bears the token you did not accept that year.