The doll didn’t look particularly valuable, but it had a lovely face.

Chestnut curls, blue glass eyes, blushing cheeks. The legs that extended from under her dark green apron dress swung back and forth, as if she was bored, and although she had no one to talk to, her high-pitched soprano voice chattered incessantly in a subdued whisper.

As she listened attentively, the doll’s adorable lips, still smiling, spat in an adorably high voice, one hateful complaint after another, like, “That damn third-rate doll maker, I told him to make my eyes out of jade, but he used these cheap glass balls. He can go to hell ten million times,” or, “How dare that black bear grab my leg and swing me around. He deserved what he got, being taken off by the garbage collectors.”

The girl froze automatically, gaping at the doll. The string of abusive language ceased abruptly, and a strange silence settled over them.

A girl’s face rose palely from the darkness, creaking as it turned ninety degrees toward her. The glass eyes didn’t blink, fixed in an eerie state; only her red lips moved, demanding suddenly, “Hello! Stop eavesdropping, and let’s play!”

“!”

The girl drew back in surprise, and her back crashed into someone sleeping beside her. “Hm…? What’s wrong?” came a woman’s sleepy voice.

That instant, the doll froze, regarding her with a chilling smile plastered to her innocent face.

“My doll! She was talking…!” she appealed in a lisp, but the person next to her just sighed in exasperation. “Oh, is that all?” But the woman didn’t say it mockingly or as if politely consoling her after a bad dream; she said it quite plainly, as if such a thing was nothing out of the ordinary.

“Even dolls talk sometimes, when they’re bored. You’d be bored, too, if you had to sit quietly wearing the same outfit all the time,” she said, smiling kindly, and readjusted the blanket. The girl wasn’t at all satisfied with this explanation, but when soft, white fingers brushed the hair off of her forehead, she felt better somehow, and a talking doll started to seem as if it wasn’t such a big deal after all.

When she closed her eyes, she could feel the gentle vibrations of the ship and the low sound of its engine. She felt as if she was in a cradle as she gave herself over to the comforting rocking and finally fell asleep…

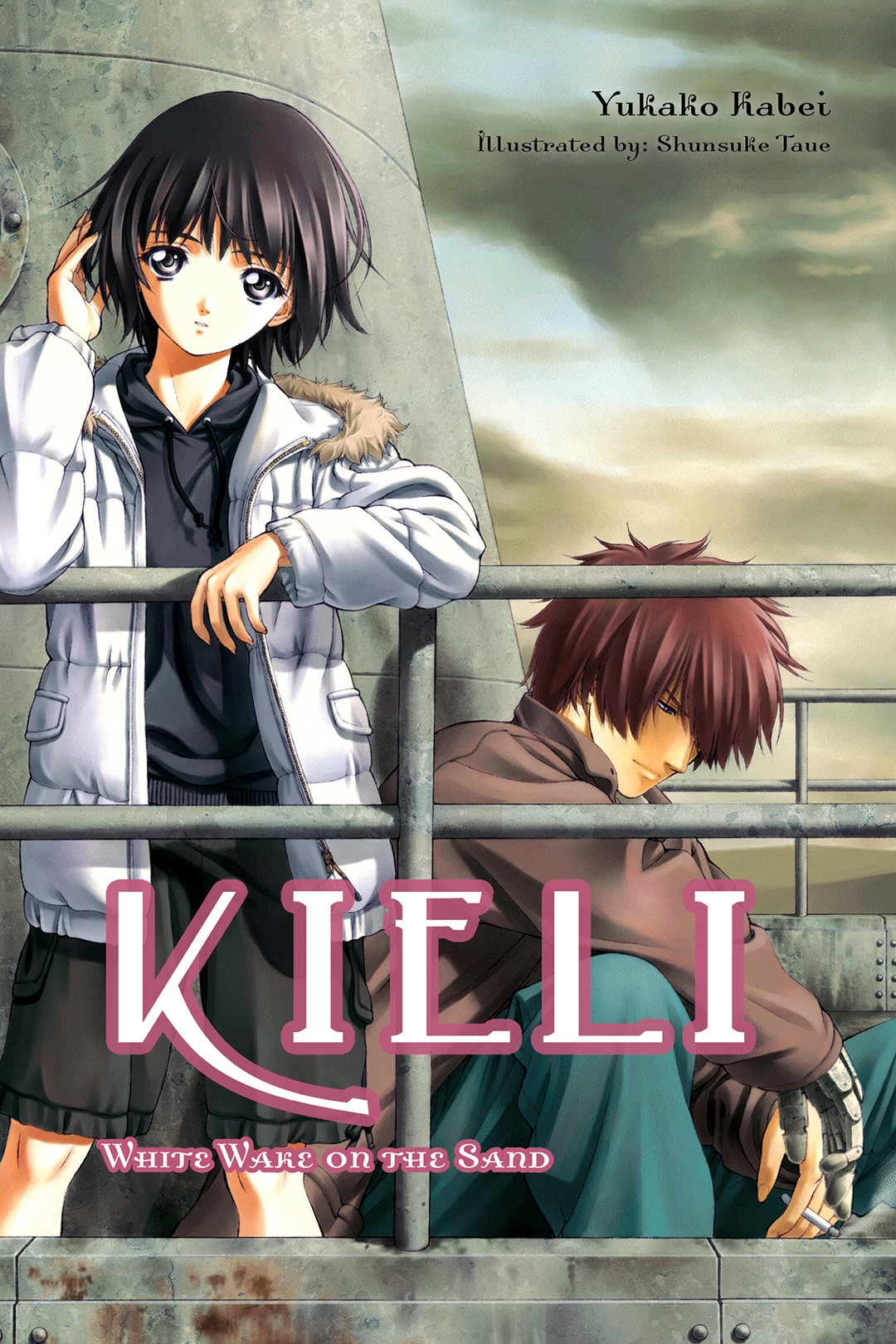

“Kieli. We’re getting off.”

A voice rained down on her head, pulling Kieli out of her light doze, and she opened her eyes.

…A dream, she thought vaguely as she turned her groggy gaze to her right and left. Who was that person? She got the feeling that maybe she remembered the feel of those soft hands and that slightly husky voice…

“Ah!”

Once Kieli realized that the other passengers on the train were starting to get up noisily from their seats, she was suddenly wide awake. Before she knew it, the scene outside the window had changed from the endless, monotonous wilderness that had lulled her to sleep on her long journey to the bustle of a station platform.

“SAY HELLO TO MY DOLL.” - 5

“We’re here? You’re kidding.”

“I’m not,” her traveling companion answered shortly, standing on the other side of the box of seats and reaching up to the rack to get their luggage.

“But you promised you’d tell me when we could see the ocean!”

“I told you. It’s your fault you didn’t wake up.”

“Really? How many times?”

“Once,” her companion answered immediately and unapologetically. He was tall enough that he didn’t need to stretch to pull their bags off the rack. He easily freed Kieli’s bag and handed it to her. He caught her glare as she puffed her cheeks out in disappointment and winced. “You’re mad about that? You don’t have to be in such a hurry; once we’re on the boat, you’ll see so much of the same thing every day you’ll start to hate it,” he said curtly, then hung his own backpack from his left shoulder and walked down the aisle.

“Ugh…”

Kieli glared loathingly at his back for a while, but, seeing him favor his right side as he walked with some difficulty, she thought better of it and hurried out of her seat, carrying her bag and down coat. As she began to leave, she turned around and grabbed the cord of the small radio left on the windowsill, then ran down the aisle after the copper-colored head sticking out above the crowd.

She was sad that she didn’t get to see the ocean from the train, but when she thought about getting on the boat soon, her step naturally lightened, and she practically bounded down the steps onto the platform. The shoulder bag she wore bounced loudly against her hips.

“We’re here! We’re at the station!”

When she stretched and took a deep breath, a scent of dry wind from the harbor, mixed with the pleasant outdoor air, tickled the inside of her nose.

They were at the last station on the far east of the continental railroad that ran across the wilderness. Beyond here spread the Sand Ocean—a vast sea of flowing sand said to cover sixty percent of the planet’s surface.

What do normal people think of when asked to list what a person needs to live? Air. Water. Food. And if they want to live a fairly civilized life, clothes and a place to live.

Conceivably, there are some who might say love.

Beyond that, “Money,” her traveling companion declared, extremely frankly, without any hesitation, nuance, or optimism.

And, well, he was exactly right. People like them, who wandered everywhere and never stayed in one place, had a lot of things like travel expenses and lodging expenses that required money, and in most cases, they needed to do something to get that money to pay those expenses wherever they went.

“Are we gonna get part-time jobs?” Kieli asked, half hoping because she would have liked to try it, but he flatly rejected the idea, asking who would do something that was such a waste of effort.

To him, the way to attain funds seemed not to be anything as admirable as earning it for steady labor (although if you asked him, his method was a fine, steady one), but to “get what you need in a night and get the hell out of there so as not to have any future trouble.”

And so Kieli and her companion were, at the moment, on the outskirts of the warehouse district a little ways from the harbor, at a not particularly classy shop in a not particularly classy alley, doing not particularly classy things. The entrance was run-down—it didn’t even have a sign—and yet when they went down the dark, narrow stairway to the basement, there was a surprising number of customers; there were a few men surrounding each table under the dim lights, and noise, tobacco smoke, and the scent of alcohol filled the hall—that’s the kind of place it was.

“Ah!” Kieli couldn’t help making a little sound as she gazed meekly at the five cards in her hands, and her expression brightened.

She held all five of the cards unified by their dark green trade color and the mark representing the “free city” suit. The designs drawn on them were the “judge,” “sword,” “revolution,” “bishop’s staff,” and “shepherd.” She knew from watching several times that this was apparently a very strong hand.

“…Look, Kieli,” a low voice addressed her. She turned to Harvey, who was sitting beside her, glaring down at the table with his eyes half-closed, a vein throbbing in his temple.

She gasped and looked around at the other men surrounding the table.

One of the men stared firmly at her. He said, “I fold,” and threw his cards down on the table. The other two followed his example and announced their forfeit of the game. Harvey swore quietly enough that only Kieli could hear him, took Kieli’s cards out of her hands, and tossed them carelessly on the table.

When she looked at all the other cards on the table, she saw that someone had collected five silver “federation army” cards, but of all the hands, her five cards were overwhelmingly the strongest.

“That’s some partner you got there, One-Arm,” a man laughed sarcastically. He got up from his seat and started collecting the cards. (The person in charge of distributing cards was called the “dealer,” and they took turns playing him by rotation.) “Yeah, well,” Harvey returned ironically and none too kindly, pulling the small bills that had been left on the table toward him with his left hand, not very happy.

“Sorry…,” she whispered apologetically and glanced sideways at him, but Harvey wasn’t even looking at her; he breathed out a puff of tobacco smoke with a short sigh. She ducked her head in shame. It was most basic of the basics in this game not to let it show on your face how good or bad your hand was. Apparently it was called a poker face, after the game this one was based on.

“One-Arm” was the name the players at the table called Harvey, for convenience, and Kieli was either “Tiny” or “Little Girl.” The other three at the table were “Whiskers,” “Tattoo,” and “Glasses,” after their most easily distinguishable features, so there was no room for confusion; almost everyone in the place, including them, were sailors on a sand ship anchored at the port. Of course Kieli was small, but in the midst of all these sailors whose only redeeming quality might have been their thick, well-built frames, even Harvey seemed delicate, and although there was no malice in their dubbing him One-Arm, there was a feeling in the air that they were sneering at the “little boy,” looking down on him.

As she picked up the cards that had been dealt her, Kieli threw a glance to her left at Harvey’s right side. The empty right sleeve dangling from his half-coat was shoved artlessly into his pocket at the wrist. Acting as aide to Harvey, who could use only one of his arms, Kieli was in charge of sitting next to him and holding his cards. (Incidentally, Harvey had a habit of playing with his lighter in his left hand under the table if he had bad cards, but the action was only visible from Kieli’s angle, so the other players probably didn’t suspect.)

Harvey looked over her head at his cards; he used the same fingers that held his cigarette to take two and discard them on the table. The dealer passed him two more cards, and Kieli picked them up and held them at an angle so only they could see.

He had two “swords” with different marks, and two “weapons dealers.” Two pairs. Not bad, but not so good, either, Kieli thought, feeling like she understood.

There were five different suits: “federation army,” “liberation army,” “free city,” “temple,” and “nomads.” There were thirteen picture cards for each mark, for a total of sixty-five cards in a deck. Each player received five cards, and the winner was determined by the strength of the marks and pictures in each hand—that was the general idea. The rules as to which cards made up a strong hand were pretty complicated and mysterious and impossible to commit to memory in a day. By itself, the “shepherd” was the weakest card, but it was also one of the five cards that made up the strongest hand.

She’d heard that the Sand Ocean sailors were descended from the crew of the spaceship that brought the settlers here in the colonization era. So the card game the sand sailors inherited was originally a game that the astronauts played to kill time during long voyages through vast space.

She didn’t know if they were left over from that time, but some of the cards’ names were peculiar nouns that Kieli had never heard before. She could kind of imagine the “liberation army” with its blue trade color, but she didn’t know the silver “federation army,” and the most incomprehensible of them all was the type of picture card called “Moon and Planet Earth.”

Of course she knew “moon.” Layers of thin sand clouds covered the sky on this planet, so she could only vaguely make out its shape on days with good weather, but the word referred to the two satellites that circled the planet. But she had never heard of “Planet Earth,” and she thought it was weird that the picture on the card only had one moon.

“Kieli, hey…” Harvey called her for the umpteenth time that day, using the same tone of voice, somewhere between anger and resignation. When she snapped to attention, the eyes of all the other players had concentrated on her. She’d meant to really work to maintain her poker face this time, but before she knew it, “Not bad, but not so good, either,” was ingrained in her expression.

No one folded, but instead the players took turns tossing crumpled bills to the center of the table.

“I fold,” Harvey muttered—this time, he was the one to give up. For a while now, either he would fold immediately and lose a few coins, or everyone else would fold immediately and he would gain a few coins. Even Kieli, the amateur, got the feeling that this was not a very exciting game.

The other three finished the hand, and the man with the whiskers, who had four “cruiser” cards, whistled and said, “Thank you very much” as he gathered the bills. The losers groaned and slid their cards back to the dealer, who gathered the cards and started to redistribute them. Kieli had gotten pretty much used to it, so she didn’t hesitate to reach for the cards that slid in her direction, but was told, “That’s enough from you. You’re in the way. Go back to the hotel.”

The words flew at her with a smooth, casual air, but their contents were ruthless and pushed her away; without thinking, she stopped her hand.

“Oh? What? There’s no need for that.”

“Poor thing. We don’t mind a bit that she’s here.”

“Yeah, yeah. The fun’s just getting started.”

As the other players all joked, Harvey kept his head down, raised only his eyes, and muttered quietly, but with enough menace to freeze the air around them, “You got a problem?”

His tone made even Kieli shudder for a second, and the unexpected intensity of the one-armed “little boy,” who no one would believe was stronger than the sailors by any stretch of the imagination, seemed to overpower them. Their faces froze, their smirks still in place.

“Kieli,” he urged her.

Kieli stiffened with everyone else, but at his urging, she kicked her seat and stood up out of reflex. She glanced at Harvey to gauge his mood, but all she could discern was that he wasn’t leaving any room for her to voice an opinion. She gave a reluctant, “…Oookaaay,” and left the table.

“No detours,” Harvey’s voice called after her, but, displaying what little rebellion she could, she ignored it and ran for the exit.

She almost crashed headlong into a waitress who was busily carrying beer mugs around. Kieli was shocked by her provocative costume with its scant fabric. Kieli lost her balance when she dodged, hitting the back of another customer as she trotted out of the tumultuous hall and ran up the gloomy stairway.

Emerging above ground after climbing the stairs in a single bound, she turned around; the dim light that rose in a square from the hall at the bottom of the stairs somehow seemed like the entrance to another world. The clamor and stuffy air that reeked of tobacco smoke and alcohol had mysteriously vanished as she went up the stairs and didn’t reach her outside.

There was no sign of anyone else out in the warehouse district’s dark streets, but she could hear the murmur from the bustling main street one block over. Gift shops selling goods imported from the continent across the ocean and pubs that served travelers and sailors lined the port city’s main street, and apparently it was busy late into the night.

“He didn’t have to chase me out. Right, Corporal?” Kieli grumbled aloud and looked down, hoping for a response from her usual conversation partner, but the radio that normally hung from her neck wasn’t there. She realized she’d forgotten it in the gambling house and turned back toward the stairway.

But she hated to have to go back and get it, so, “…Oh well. Guess I’ll go to the hotel.” Inwardly, she stuck her tongue out at Harvey at the bottom of the stairs and turned on her heel. They’d reserved a room at a hotel (or rather a cheap, tiny inn run by a man with a bad leg and his ill-tempered wife) on the main street.

She started walking that way but changed her mind and stopped.

Without the Corporal, I’d just be bored if I went back…

Harvey told her not to take any detours, but wandering a bit should be fine, as long as she got back before him. Maybe she’d go see the night market, or…

“The harbor…,” she muttered to no one in particular and set her sights in the direction opposite the main street.

The square roofs of a cluster of warehouses stood like black shadows against the night sky. The scent of sand drifted faintly from behind them.

Kieli scrambled up to the top of the pile of four-legged tetrapods on the shore and took a deep breath, filling her lungs with the sea breeze.

The ocean that spread before her eyes seeped blackly into the night sky, becoming one with it, and was not the majestic view she’d expected. But the quiet sound of sand lapped ceaselessly in her ears, rhythmically growing louder and softer at low intervals, and she could sense part of the ocean of flowing sand extending all the way to the horizon.

A gentle breeze brushed against her cheeks and hair, carrying particles of sand. To the people who lived in the area, the dry wind didn’t really bring any blessings in with it, just exposed the land and buildings to sand and eroded them, but compared to the inland’s harsh winter winds, even its chill felt gentle, and it was perfectly refreshing and pleasant. She’d left her down coat at the inn, but her sweatshirt and shorts were enough.

The Sand Ocean that consumed sixty percent of the planet’s surface was, as the name suggested, an ocean made of sand. Extremely fine, light sand rode the tides and created waves, called flowing sand, that circled the entire planet, never staying in one place. The two moons that crossed paths as they revolved around the planet produced a complex, twisted gravitational pull, and its effect formed the strong tides—but she had only memorized that information for last year’s geography winter final.

School, huh…

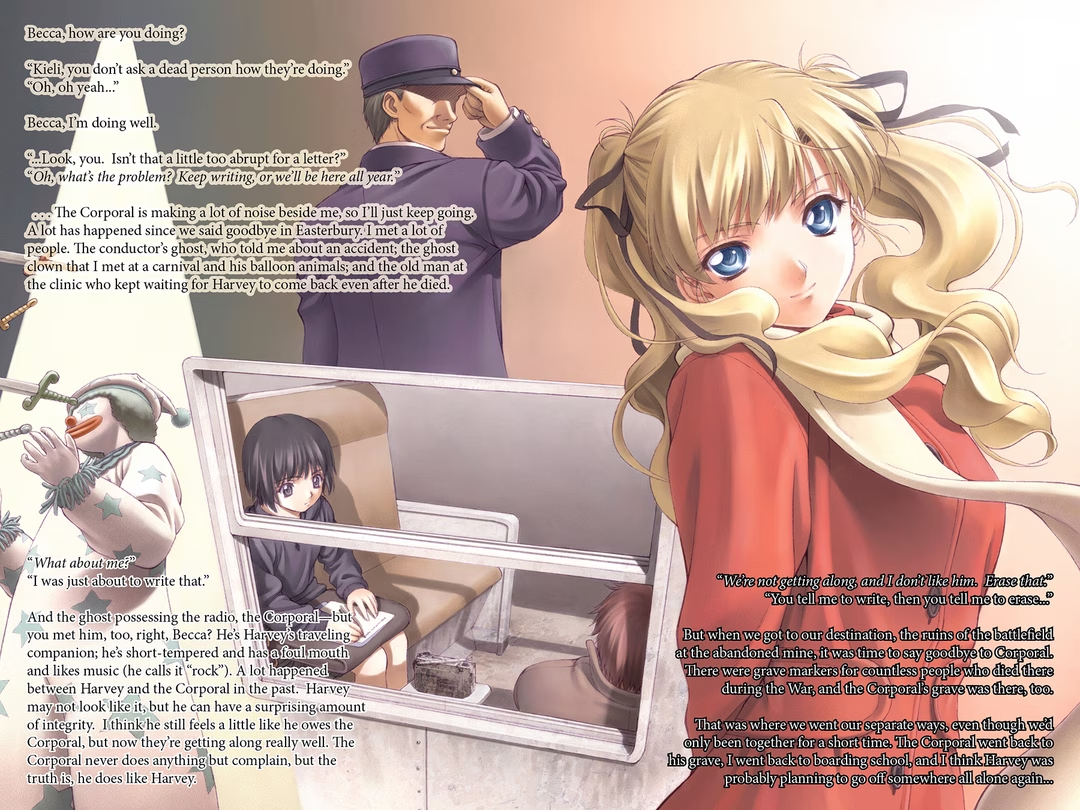

Now that she thought of it, it would be about time for winter finals at the boarding school in Easterbury. Miss Hanni, her classmates, her room at the boarding school, and the face of her departed roommate flashed through her mind. Becca always got bored when Kieli was busy studying for tests and would talk to her and be even more annoying than usual; Kieli’d found that irksome, hadn’t she?

It hadn’t even been a full winter since her days at the boarding school, but it already seemed like such a long time ago. She’d gotten so used to her short hair and boyish appearance that it felt like she’d had them for years.

“Oof…”

Balancing on one leg (not that she would have hated the idea, but she would never have done this back when she only wore skirts), she turned around clockwise, taking in the scenery.

Facing the ocean, on her right, a line of concrete sand-proof embankments continued in a gentle arc along the coast, disappearing into the darkness a little ways away. When she turned her back to the sea and faced the opposite direction, the lights from the main street flickered in the distance; she wouldn’t go so far as to call them dreamlike, but they gave the impression of an elegant night city.

Facing the ocean again, she saw the harbor along the coast to her left. Lights glowed here and there; maybe people were getting ready for the next morning’s departures. She could vaguely make out the outlines of white piers and black boats against the dark gray night sky.

She’d be boarding a ship there the following day. If they missed the boat tomorrow, they’d have to wait a week for the next one.

Her heart beat excitedly when she thought about getting to ride on a ship, but for some reason a sinking feeling accompanied it, and she crouched down on the tetrapod and held her knees. As she rested her chin on her knees and gazed at the lights from the harbor, she reasoned over one thing and then another in her mind.

She was the one who had insisted on tagging along to the gambling house even though Harvey had told her to wait at the hotel, but that was because she worried about Harvey, who was still having problems with his wounds, not yet healed. The reason she’d asked if she could hold the cards at the beginning of the second game was because after she’d watched the first game from the sidelines, it looked like it was hard playing with just his left hand…

…and Harvey never asked for help.

She realized again that Harvey didn’t really need her; that, instead, the smallest things she did dragged him down; the thought made her uneasy. Right after they reunited at the Easterbury transfer station, she had lent him a hand a lot because he couldn’t walk properly, but he might have allowed that only because she happened to be there to use as a crutch. They’d stopped at stations along the way to rest, and it took them half a month to get to the port town; by the time they did, he was limping a little, but his leg had gotten much better, and there was no longer any need for Kieli to help him out.

His right arm had been almost completely blown off, and of course it looked as if that wouldn’t regenerate so easily, but it didn’t seem to bother him that much. He said, “Give it three, four years, and it’ll be back to normal. It only took that long last time” (by which she figured he meant right after the end of the war eighty years ago), with a look on his face as if he was talking about next month. To Kieli’s sense of time, though, three or four years wasn’t so near in the future that she could afford to wait. After three or however many years, Harvey would still look about twenty like he did now, but Kieli would be seventeen in three years, and she couldn’t imagine herself at seventeen.

In fact, now that she thought about it, they wouldn’t necessarily be together in three years anyway. There wasn’t even any guarantee that they’d be together for more than ten days.

It would take their ship ten days to reach the southeastern continent—she hadn’t heard a word from Harvey about what he would do after that. In the worst-case scenario, it might be that the only thing in Harvey’s head was his single-sentence promise to get her on a boat, and he didn’t have any inclination to do anything with her beyond that. It was possible that once they reached the port on the other side, he would say, “Well, g’bye. I kept my promise…”

“…No more of this.”

Feeling herself sinking into a bottomless pit of depression, Kieli forcibly cut off that line of thinking.

After all, even in that worst-case scenario, it meant that she’d definitely get to be with him for at least ten more days. It was better to think that way.

Just as she shook her head lightly back and forth and diverted her thought processes into a positive direction, “……?”

Something moved at the edge of her vision. She twisted her head around and squinted past the sand-proof wall to see a small mountain of tetrapods catching the dull light from the pier, rising whitishly into view.

A small creature was struggling between the piled blocks. She could see two more of the same kind of creature moving around nearby.

What the…?

She ducked down and crawled across the blocks to sneak up close to them and saw that they were little people, about as tall as Kieli’s knee.

People? No.

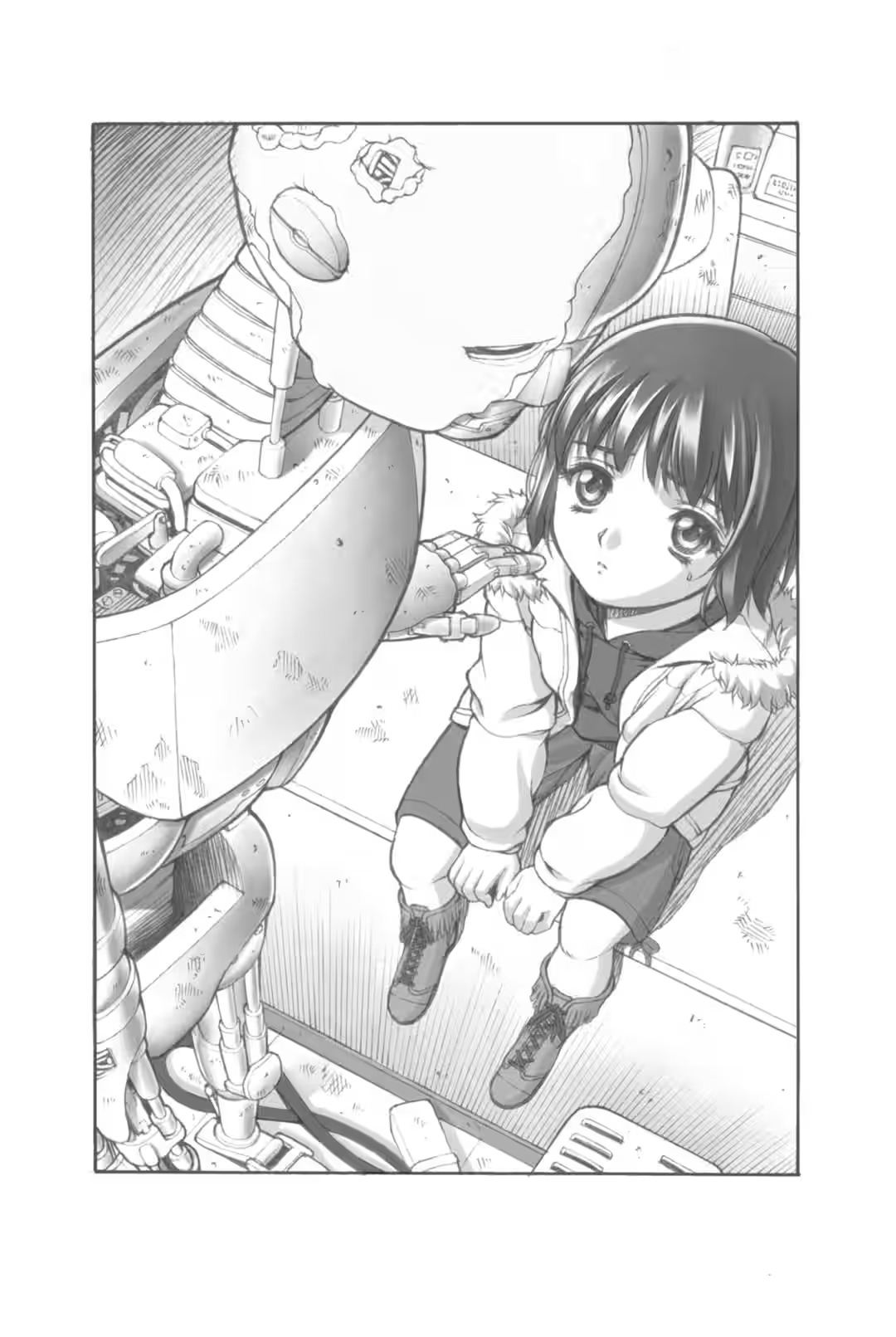

They were three tin dolls wearing matching sailor collars and triangular hats colored red, green, and yellow. Such collars were the trademark of seafaring men appearing in old stories of past times, so they must have been modeled after those sailors. Cone-shaped noses poked out of their perfectly round faces with small, perfectly round eyes half-hidden by their triangle hats.

The doll in the green hat was stuck between the tetrapod blocks. The doll in the red hat tried pulling on his arms and then pulling on his legs, and the one in the yellow hat just went back and forth in a panic, running around—oh! he fell.

“Are you okay?” Kieli couldn’t contain her laughter. She reached out a hand and helped the yellow doll up. The doll jumped up with a little yelp, perhaps startled, and very cautiously made an about-face to look behind him. The doll in the red hat who was pulling his stuck companion’s legs at a very reckless angle (he looked like he was winning a wrestling match) stopped immediately and looked in her direction.

Kieli went a little closer and offered her hand to the stuck doll in the green hat. The doll resisted and struggled for a second but soon settled down and relaxed his body so that Kieli could handle him more easily.

When she pulled him out from between the blocks, his torso scraped the concrete a little.

“I’m sorry. Did that hurt?”

The doll, having finally regained his freedom, alighted onto the wall with his tin shoes, looked at her, and shook his head furiously. The red-hat and the yellow-hat dolls ran to his left and right. They all stood up straight in a line and hit their right fists near their hearts and thrust them forward in an adorable sailor salute.

Then they all bowed quickly, made a ninety-degree right-face, and marched very precisely toward the town with the red-hat doll in the lead. In the rear, the yellow-hat doll moved his right arm and right leg in unison.

Ummm…

Kieli watched them march off, then stood there gaping for a little while. She helped them because they were there, but it didn’t occur to her until just now to wonder what in the world they were.

Well, even dolls must move and talk to kill time, but…

The thought came to her out of nowhere, and she got the feeling that someone had said that to her before. Who was it? A long, long time ago…

As she wondered vaguely in the corner of her mind, she focused her gaze on the lights of the town where the dolls disappeared and thought, “I wonder where they’re going.”

Yeah, she nodded to herself, then jumped off the wall and started to run at full speed.

Assuming that everyone else had conspired to take away all the money he had on him, and assuming his social standing was such that he would prefer to avoid getting into a fight and causing a scene, and assuming that the game itself wasn’t any damn fun anyway, Harvey figured it would be wise in such a situation not to say anything and to get the hell away from the table.

But by the time he realized that he’d been had, Harvey was in a position where he couldn’t back down until he regained some of what he’d lost; that’s how the world worked.

Argh, I’ve lost my touch…

Harvey cursed inwardly in annoyance. Not so much at the guys who had tricked him but at himself for taking so long to deal with them.

He thought that the reason he couldn’t get into the swing of the game was that he hadn’t played for so long that he couldn’t get a feel for it, but somewhere along the way, he started to notice the other players’ unusual bets. The fact that they weren’t very high only made it harder to catch on. If they all thought that one of their pals had a stronger hand than he did, then they made a sign to each other and would all raise the stakes; if not, they all folded. Most likely, they needed only one of them to win, and they’d divide the winnings later.

Harvey reached out to pick up the cards he’d been dealt, but it really wasn’t easy without a right hand, and it took him some time to confirm which five cards he held. It was true that he couldn’t stand how Kieli reacted to every little thing as she sat next to him, but it was pretty helpful having her there.

A faint static emitted by the radio left in Kieli’s seat needled Harvey, as if lecturing him. He wondered what it was so mad about; then he guessed, accurately, Oh, it must be because I was so hard on her when I chased her away. But it wasn’t that he cared one way or another about Kieli. He sent her back because, judging from the atmosphere, if things kept going the way they were, they would have suggested betting her instead of money, and if that happened, he wasn’t confident that he could have settled it without a fight, or rather, he wouldn’t settle it without one.

“Yo, One-Arm, what’re you gonna do? Don’t you think you’d better go on home before you lose any more, boy?” the man sitting diagonally across from him said, with an obvious sneer. He was a big man with a giant snake tattoo coiling around his upper arm, which was as thick as Harvey’s thigh. He was called “Tattoo” accordingly.

“If I lose any more. Let’s go one more hand.” Harvey easily rose to the challenge (Tattoo smirked as if to say, “What an idiot”) and cast a sideways glance at the radio next to him. It sputtered static grumpily, no doubt thinking something like, “Why don’t you just give it up already, brainless; you’re not gonna win anyway. You wanna go bankrupt?”

Oh, shut up. You can’t complain if I win.

He furrowed his eyebrows stealthily and reached out to the radio. “Can I bet this?”

When he lifted the radio by its cord to show them, for a second a voice, “Geh,” slipped out of the speaker, then immediately blended into the static and vanished.

“Are you kidding? That piece of scrap?” Tattoo started to object.

“No, wait a minute,” another man interjected, leaning over the table to take a long, hard look at the radio. This one had thick black whiskers covering his cheeks so was naturally called “Whiskers.” “It’s an antique radio from before the War. I saw one like it in a curio shop in South Hairo. Does it still work? Incredible, a collector would pay a mint.”

“Then it’s okay, right? If I lose, you can do whatever you want with it,” Harvey declared, ignoring the homicidal mood he could sense from the radio. (He knew that it had some value as an antique, but to be honest, he didn’t know it had that much value. Next time he was really hard up for cash, he would think about pawning it off.)

He was just getting back into the swing of the game; now he would be in trouble if he didn’t seriously try to win something.

It didn’t matter if the other guys were in cahoots or not. There wouldn’t be a problem if he could get the money they wagered (rather, he would appreciate it if they raised the bets pretty high), so basically, he either had to get a winning hand or else get his opponents to fold.

“Wah, I’m sorry!” Kieli apologized hastily to the pair of passersby as she crashed into them, looking every which way as she ran, and brushed past. They were a sailor and a woman with thick makeup and a faux fur coat; the sailor watched curiously and the woman dubiously as she left them.

The pubs that served travelers and crews from anchored ships stood out in the port town at night, and beautifully dressed women stood here and there along the streets, alone or in pairs, and when they caught a man who looked like a sailor, they would call out to him. Kieli had a vague idea of what the women were doing. It wasn’t as if there weren’t any neighborhoods like this in Easterbury, where she grew up, and in a port town with lots of sailors who didn’t get to see women very often in their daily lives, they were probably in higher demand.

She started to feel a bit anxious. This wasn’t a place for someone like her to be walking around by herself at night. If the Corporal or Harvey found her, they’d probably yell at her.

Just as she began to think that maybe she ought to go back to the hotel, she caught sight of a triangular hat appearing and disappearing between the legs of someone in front of her. There were a lot of people around, and as long as no one was paying particular attention or looking down, they were hardly noticeable. It looked as if no one in the crowd had detected the small creatures weaving between their legs.

Found them!

Completely forgetting that she was just thinking about going back, Kieli sped up and pursued them.

“Huh…”

When she got to the spot she thought she’d seen the triangle hat, Kieli lost sight of it again and stood there bewildered. “Whoops, careful now.” Someone ran into her from behind; she tottered and clung to a nearby light post.

A side road led away from the shadows of the streetlight. It was a narrow alley, sandwiched between pubs on either side; piles of garbage lay next to a door that seemed to lead to a kitchen, and a stagnant air settled along the ground, making it seem even narrower.

She could see the red, green, and yellow triangle hats marching along on the other side.

Wait! She inwardly called after them and went through the alley, stepping over the piles of trash. Halfway down the narrow passage, the streetlight hardly reached anymore, and the alley was pitch dark; she got discouraged and looked back to see a sliver of light glittering from the business district, but somehow as if from a distant world. Deciding there wasn’t much difference between the danger of the business district at night and the danger of the other side of this alley, she aimed for the pale blue light that she saw at the alley’s exit and set off at a trot.

She came out onto a street lined with old stores and small workshops.

Unlike the business district, where this was the time for earning money, almost all the shops on this street had already closed and turned off their lights. It was dark except for the pale blue streetlamps that flickered here and there. A few of the shops had papers plastered over their shutters as if they had shut down for good, and the torn papers sometimes fluttered in the wind. The sound was abnormally loud in the gloom and made Kieli jump.

She looked around in search of the dolls in the triangle hats and saw one shop with its lights still lit on the corner of the street. A yellow light leaked out, outlining the shop’s door, and cast a dim glow on the asphalt.

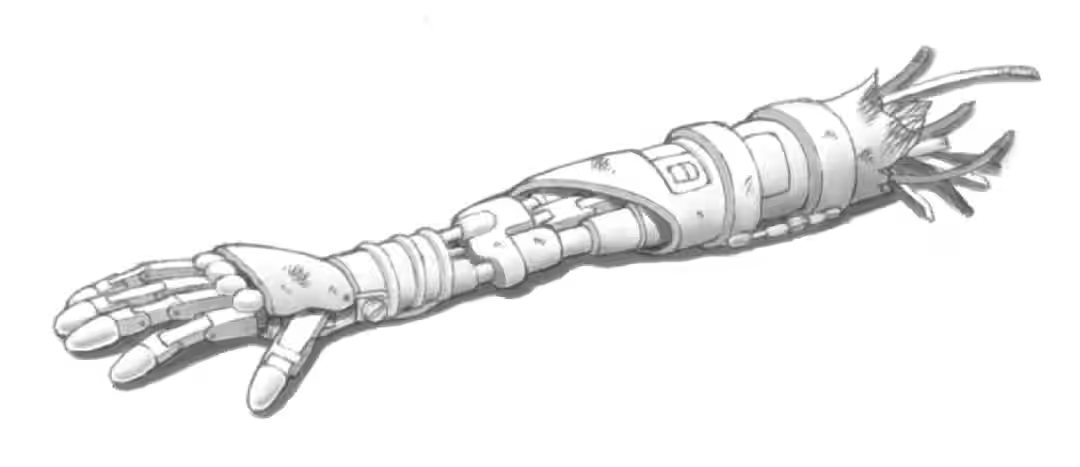

There was a small display window next to the door; a mechanical model ship, a five-fingered mechanical arm—maybe a robot arm or a manipulator of some sort—with its cables and metal framework showing, and other such things lined up in disarray on the other side of the dusty, dirty glass. Apparently it was a machine shop or something.

As she stood in front of the store looking at the display window, the door beside it opened with a rusty creak, as if inviting her inside. The light grew somewhat stronger, illuminating the street, and warm air flowed outside.

Kieli hesitated but sidled closer and peered inside the door.

“Um, hello…” she tried in a small voice, but apparently no one heard her as there came no answer.

It was a small shop. Metal parts of all shapes and sizes—Kieli had no idea what they would be used for or how (possibly most of them were junk)—filled the room in heaps, making the already small shop feel even more cramped.

Kieli spotted the triangle-hatted dolls sitting in a line on a shelf made of steel framework and cried out, “Ah!” But now they showed no sign of movement and sat quietly with their tin legs hanging from the edge of the shelf as if they had been left there all along.

There was a counter in the very back of the shop, and behind it appeared to be the workshop area. A bright fire burned in a wide-mouthed furnace. A man, probably the shop owner, sat in front of it wearing a fireproof smock, holding a piece of metal in the flames with a pair of tongs.

“Hello. Sorry for coming in without asking…”

Perhaps her words failed to reach his ears because he was so immersed in his work; the shopkeeper didn’t react to her voice but silently continued his chore.

She tried waiting a bit, but it looked as though he wasn’t going to notice her after all, leaving Kieli at a loss; she hadn’t thought about what she would do once she ferreted out the dolls’ destination when she set out, and it had gotten late. Kieli thought she really would go back to the hotel.

GIMMICK DOLL, GIMMICK HEART - 29

“Um, I’m going now. Sorry for bothering you,” she tried addressing the shopkeeper again, but, as expected, she got no response; when she spun on her heels and headed for the door, something suddenly occurred to her, and she stopped. She turned to the shopkeeper once more.

This man…

She brushed aside her initial assumption that the man sitting there was probably alive and looked again to see that the shopkeeper, giving undivided attention to his work, was not a living human being.

Harvey once told her that people possessing keen spiritual senses like Kieli’s sometimes picked up on strong thought waves from memories that imprinted themselves on objects and places, like projections. Was what she saw right now the memories of the shopkeeper himself from when he was still alive, or were they someone else’s…?

Just then, she sensed something behind her. She spun around, and a tall shadow was standing so close she could touch it—how long had it been there? The instant Kieli raised her face to the figure, she practically leaped backward, crashing into the counter behind her.

It was a rusty metal doll, as tall as an adult male. It stood there, the metal framework of its robot arms, just like the one in the display window, hanging from its likewise exposed shoulder joints. In contrast to the bare metal skull on the left side of its face, the right side was halfheartedly covered in a skin-colored rubber. The difference was so bizarre, it was creepy.

Kieli was frozen in place and couldn’t move. The doll’s robotic hand reached out and unceremoniously grabbed her upper arm.

“No…!” She screamed and tried to shake it off, but the doll was strong and didn’t even twitch. Robotic arms caught her up on both sides, and her feet hung in the air.

“No, let go! Harvey!”

“Man, that felt good; just remembering those guys’ panicked faces, I could burst out laughing. You’re better than you look, Herbie. I’m impressed.”

“Harvey.” When the exultant voice flew at him from the radio dangling in his only hand, Harvey was too exasperated to do anything but correct its pronunciation. For a guy who was so homicidal when Harvey was losing, the radio sure cheered up quick the minute he started winning; man, he couldn’t tell if he was kissing up or just dumb—not that it mattered.

As soon as he earned enough for boat fare and living expenses for a while, Harvey completely pulled out of the game and put the gambling house behind him. Now he was walking back to the hotel. The business district was probably still bustling, but by this time, the gift shops in the area were almost all closed. Except for the dull light and muffled noise that escaped pub windows here and there, a listless atmosphere filled the street, as if everyone was tired of partying.

“But your poker face really is something. You really had those guys going. You could have taken so much more from them. Stopping when things were just getting started? What a waste.”

“I got what I needed; that’s enough. If I make too much of a show of winning, they’ll remember my face, and I don’t want to do too much that people will remember.”

As long as the Church was after him, he couldn’t leave footprints doing things that were too noticeable, and if people remembered his face, it could get to be problematic the next time they met. Because, in any case, he didn’t age. The Corporal should have known all that, so when he answered, he was inwardly annoyed. You weren’t even interested at first, said gambling was for good-for-nothings; don’t tell me to keep going now, you fickle old man.

“…You’re surprisingly down-to-earth in your work,” the radio muttered after a brief silence, using a meek tone as if he’d convinced himself of something. Harvey made a disgusted face from the bottom of his heart.

“Cut it out; don’t sympathize with me like that.”

“Is that why you’re so cold to Kieli? Because you’re thinking of that stuff?”

“Wha—?” The sudden turn in conversation took him by surprise. He stopped automatically and looked down at the radio. “What are you talking about? I’m not cold to her.”

“Uh, yeah. You are.”

It irked him to have the Corporal declare it so finally, but for some reason he couldn’t argue and so fell silent. But he hated leaving it at that, so in retaliation, he swung his arm around and made as if to throw the radio; the ensuing scream satisfied him, and he stopped.

“Damn it, next time you try that, I’ll hit you with a shockwave in your sleep!”

“Go ahead and try, if you have a chance.” As he shrugged off the radio’s subsequent complaints and started walking again, he vaguely thought that maybe there was a part of him that was a bit cold.

He couldn’t get Kieli wrapped up in this manner of living her whole life, and if someone was to tell him that, somewhere in his consciousness, he was taking precautions against that time, he wouldn’t be able to deny it. But he wasn’t pessimistic enough to constantly worry about something when he didn’t know if it would happen years or decades from now, so he didn’t think it showed in his attitude. Still, thinking about those problems was more trouble than it was worth, and a complaint came involuntarily to his lips: “…Argh, man, this is a pain.”

“What’s a pain is your damn complicated personality.”

“Who asked you?” he responded with a sneer, and just as he considered really tossing the radio this time, he spotted the owner of their hotel starting to close the front entrance.

The owner noticed him, too, and turned around.

“Oh, I didn’t think you two were coming back tonight. I was just about to close up,” he said with a gentle smile, then moved to the side, limping somewhat, and motioned him inside. He was a middle-aged man with a relatively good physique. He had been a sailor when he was young, but he retired after getting caught in a screw propeller and losing his leg. It wasn’t a story Harvey really cared to hear, but when the man saw that he didn’t have a right arm, he must have felt an affinity for him and told him this in the lobby as they were about to leave earlier.

“Thanks,” Harvey answered casually and started to pass through, but something the owner said suddenly hit him, and he stopped. You two?

“Don’t tell me the girl who was with me hasn’t come back yet?”

“She wasn’t with you?” the owner asked in response, as if that was the natural assumption. “Wha—?” a voice came from the radio’s speaker for a second, as if he accidentally started to say something, then disappeared immediately. “What is that idiot doing…?” Harvey sighed, finishing the sentence.

“I’m gonna go look for her. Would you mind leaving the door open for me?”

“No, I don’t mind,” the owner said, nodding pleasantly. However…

“I’m sorry, but we’re closing now. We’d like to get some sleep ourselves, you know,” came a woman’s thorny voice from inside, and Harvey, who had turned around and was about to go out the entrance, stopped, agitated.

In contrast to the owner, who had a bad leg but a nice personality, his wife was a middle-aged woman with a bad temper and a shrill voice. There were more than a few types of people that Harvey didn’t get along with and would like to avoid as much as possible. This woman was definitely one of those types.

He sighed inwardly and answered, “Fine then, I’ll go get our bags. Oh, and I’ll make sure to pay for the night.” In a single breath, he answered all the questions he was sure she would ask before she had the chance and straddled the entrance again so he could go back to their room for a minute. The owner watched apologetically as he went; it would seem his opinion didn’t count for much. “Oh yeah. Hey,” he addressed Harvey’s back, apparently wanting to offer what help he could in sharing what he had just thought of.

“There’s a machine parts shop on the edge of the industrial district; you should stop by there before your boat leaves tomorrow.”

Harvey blinked, wondering at this sudden declaration, and turned around. The hotel owner lifted the pants on his bad leg slightly, revealing the metallic ankle of his artificial leg.

“The man there also makes artificial limbs. As you can see, they don’t look like much, but he makes some pretty good ones. I think you might find one useful.”

“…Huh. Thanks.” His reaction was somehow lacking since he hadn’t considered the possibility of artificial limbs, and he looked down at the right sleeve of his coat shoved into his pocket. Little things like opening the seal on his cigarettes or fastening the belt of his workpants had gotten to be quite a pain. His arm would probably grow back in three or four years, but it could be pretty convenient to have a replacement until then.

“What are you talking about? Wasn’t someone saying the owner of that shop died all of six months ago?” the wife’s voice interjected, and the conversation took a somehow brutal turn. When he looked up, his eyes collided with the clearly suspicious gaze of the wife in her nightclothes. It was no surprise that a respectable citizen would see a drifter with one arm who went out to gambling joints as shady; since he’d brought Kieli with him, she might think that he was a slave trader or something if he wasn’t careful.

“But sometimes the light’s on at the shop. And it’s not just me; some other guys in the neighborhood have seen it too,” objected the husband in an emphatic tone, refusing to concede the point.

Not to be outdone, the wife raised her shrill voice even higher. “And I heard it from the lady that lives next door to him. Are you sure you haven’t gone senile?”

“Who are you calling senile?”

“Uhh…” The atmosphere around the couple started to become threatening, so Harvey sighed and stealthily distanced himself, then left, escaping. Give me a break.

As he climbed the stairs to the guest rooms, the radio, which had been silent until now, opened his mouth suggestively. “Herbie.”

“I know. Let’s go check it out.” Listening to the couple’s conversation, he kind of got a hunch. A light turning on in the home of someone who’s supposed to be dead—he hoped she wasn’t poking her nose where it didn’t belong again.

She seemed to have poked her nose where it didn’t belong.

Kieli had been made to sit on the counter and was feeling extremely perplexed as her feet dangled aimlessly in the air.

She had screamed in fright earlier, but the doll only picked her up and put her on the counter. It was actually a little disappointing. It didn’t seem to want to do her any harm—rather, it appeared to think she was a customer.

The dolls with the triangle hats cheerfully presented her with a plate of cookies. The three of them all worked together carrying the big oval plate over their heads. Sometimes the yellow hat in the back lagged behind, and they staggered as they crossed the counter and put the plate down next to Kieli.

Then they lined up on the other side of the plate and looked up at her expectantly.

“…Thank you.”

Kieli gave a vague smile, picked up a cookie, and took a little nibble. It was soggy and not tasty at all.

It looked like this shop hadn’t had any customers in a long time. Though it wouldn’t be wrong to say of course it hadn’t—the owner was dead.

By the shelf along the wall, the big doll (it would probably be more accurate to call it a robot than a doll) was trying to brew some coffee. Kieli could tell from her perch that the contents of the coffee jar had crystallized together. Even so, the robot hit the bottom of the jar with its metal palm and forced the round clump of powder into the cup.

In the work area, the phantom of the shopkeeper, as usual, toiled silently, holding metal in the fire and pounding it into shape. There really was an actual fire in the furnace, so she figured that the robot lit it. Why would it do that?

Even normal dolls can move and talk—but on this point, the robot’s behavior was just too strange and started to seem a little creepy after all.

The robot poured hot water into the cup and brought it to her. Its hands looked human but moved with jerky, mechanical motions as the five-fingered robotic arm offered her the cup.

“Um, I’m sorry. I have to go back now,” Kieli said without accepting and jumped down off the counter.

That instant, the coffee cup fell to the floor with a crash, and she watched as the liquid inside splattered out. She winced in surprise, and the robot, whose hands were now free, easily picked Kieli up and placed her back on the counter.

Apparently it was not going to let her leave.

“Please? I’ll be in trouble…” At a loss, she tried pleading, but the robot would not respond; it only knelt down to the floor, its knees creaking, and started gathering the pieces of the cup.

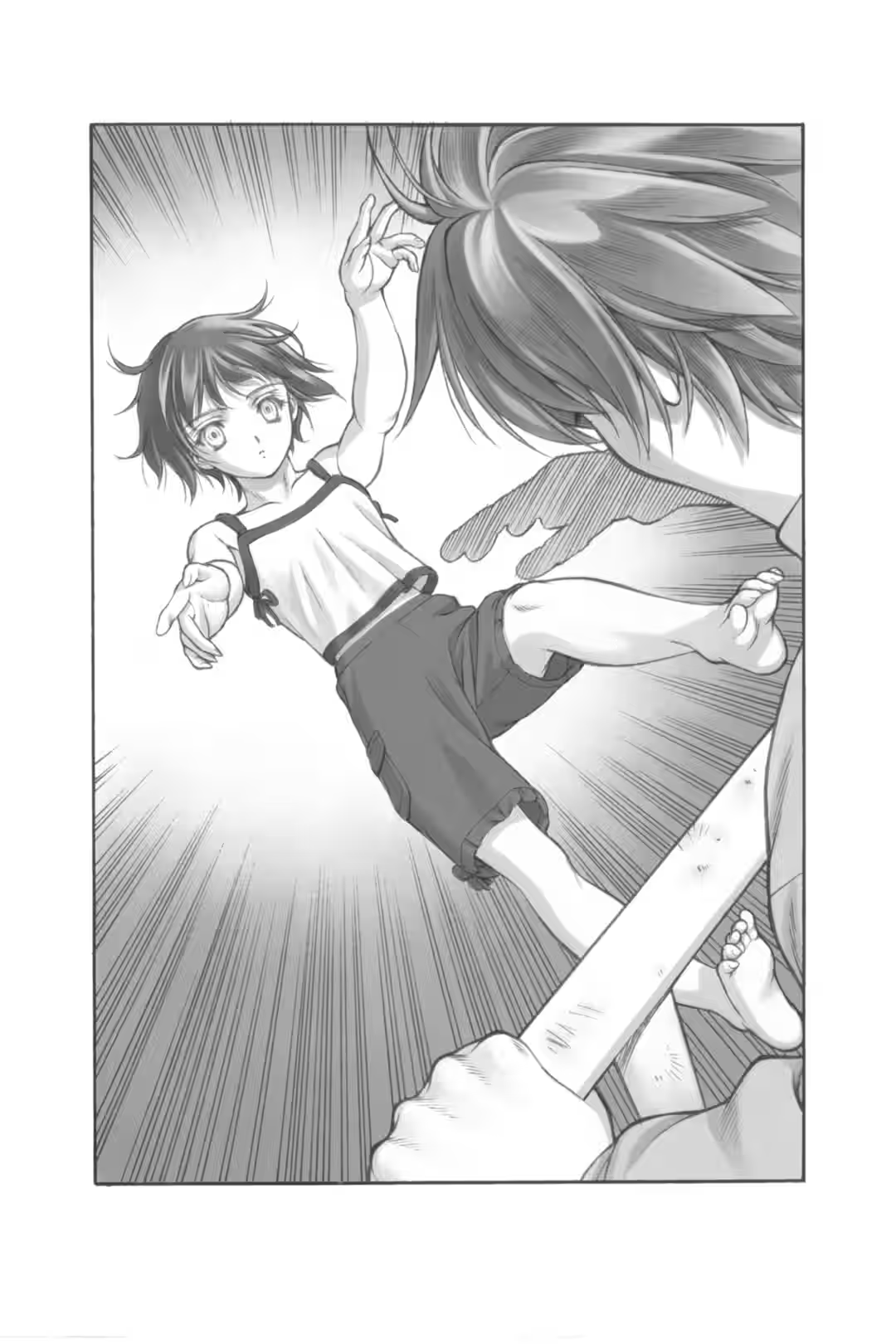

Regarding this and considering a bit, Kieli inwardly gave the signal, “Ready, go…” and this time leapt with all her might from the counter, over the head of the robot, landing on its other side.

“I’m sorry!”

She kept going and ran straight for the door.

But in the blink of an eye, the robotic arm had her by her collar and was dragging her back. She twisted her neck and saw the rubber-covered right side and the exposed left side of its face making a warped expression and looking down at her. “Let go!” Kieli shuddered and struggled with her whole body to shake the arm off.

Her heel kicked something and went numb; instantly, she fell to the floor. Her heel had gone right into its exposed joint. One of the robot’s knees collapsed, and it staggered diagonally and plunged into a mountain of iron material with an impressive crash.

That instant—

“Wah…” Kieli couldn’t help crying out, sitting on the floor as parts scattered across it.

The image of the shopkeeper sitting in front of the furnace wavered and disappeared, triggering the transformation of the entire scene before her.

With no customers coming in, the various articles lined up on the shelves had gathered dust; as she watched, the floor and the walls got dirty, and the entire shop fell into complete disrepair. Only the furnace, with its bright, white flame still burning, appeared to float strangely in the desolate scene; the emotions emanating from it were loneliness, sadness, and something like confusion.

Did they belong to the robot and the dolls with the triangle hats…?

Kieli glanced at the robot with mixed feelings. Its motor gave a weak sound as the robot flailed its limbs, struggling to extract itself from the pile of fallen scrap metal. The dolls with the triangle hats jumped off the counter and ran totteringly to it.

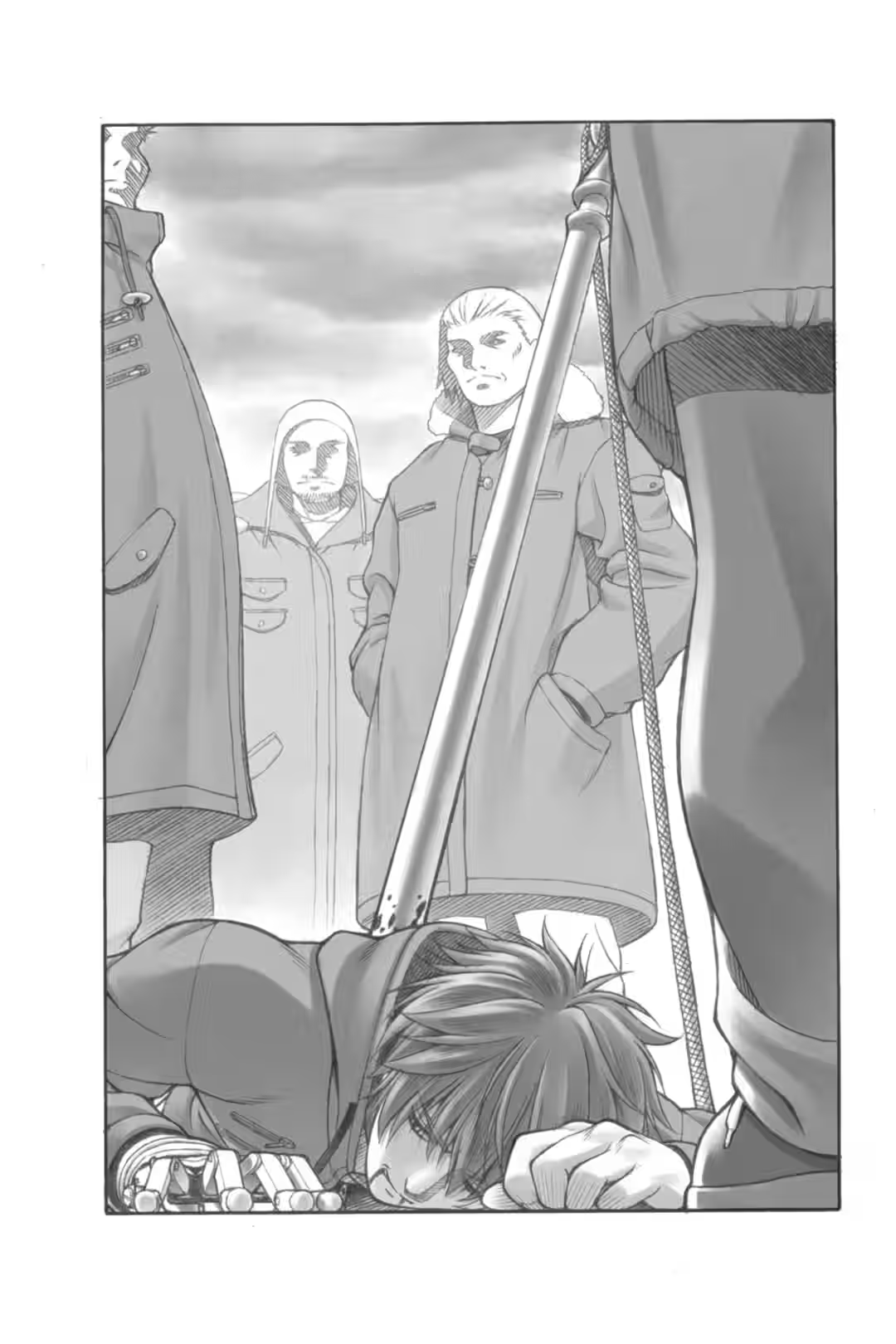

“Kieli.” A low voice fell down from over her head, and she looked up to see a tall, familiar figure standing behind her. He took in the scene of the shop with a strange, indifferent expression, yet she sensed a faint compassion intermingled with it. Then he bent his knees and knelt over her, covering her head.

“I told you to go straight back.”

Kieli hesitated a little, then offered her own right hand. The instant her fingertips touched it, there was a short whir of a motor, and the arm made a fist as if surprised; Kieli followed suit and pulled her hand back. “’S not gonna bite you.” Harvey laughed lightly, exasperated. She didn’t know which of them he said it to; he could have been saying it to both of them.

She reached out one more time, slowly, so as not to startle it. “It’s okay…,” she whispered quietly, and the arm opened its hand in understanding and timidly, softly took her palm.

“But you said I was in the way!”

“Did I say anything like that?”

“Yeah. You did,” a staticky, exasperated voice interjected. Harvey blinked and looked down at the radio hanging from his left hand. Then he threw his gaze to the side as if thinking things over. “Oh, maybe I did. I didn’t really mean anything by it,” he muttered in a matter-of-fact way that could definitely be described as too insensitive.

“Meanie! I was thinking all kinds of things…,” Kieli complained, reasonably angry. When she did, the sight of Harvey in front of her suddenly jolted to the side, leaving an afterimage.

She turned her head in shock to see that the robot’s arm had grabbed the shoulder of Harvey’s clothes and flung him to the side.

“Ack! Why, you—” Harvey twisted around and tried to take the defensive, but he must have tried to throw out the arm he didn’t have. He failed and plunged into the pile of junk parts, right shoulder first. Metallic crashes reverberated noisily against the walls and ceiling of the tiny shop. “Hold me properly, moron!” the radio jeered as it slipped out of his hand and flew to a corner of the shop.

“Harvey, Corporal!”

Kieli tried to run toward them, but the robot grabbed her arm and pulled her back. Even the dolls in the triangle hats clung to her shoes in a three-doll heap and tried to restrain her.

“Let go! Why me!?”

She didn’t know why they were so persistent with her, but it looked as if they weren’t going to let her go, no matter what happened. She pushed the robot with her free hand, but it didn’t budge, so, “Out of my way!” Kieli resisted with her entire body, leaving everything to the force of her weight and momentum as she shoved the robot away.

The robot lost its balance and staggered, about to fall over, then collapsed in a heap in the work area in the back.

“Kieli!” she heard Harvey’s voice somewhere, beneath the “whoosh” created by wind stirring up the fire. Over the robot’s shoulder, she could see the approaching mouth of the furnace with its white flames. The robot plunged backward into the furnace; Kieli closed her eyes automatically and a hot blast hit her face.

Immediately, the sound of wind and fire, along with the roar of something crumbling, assaulted her ears from all directions, and she could no longer tell what was what.

“…li!”

She didn’t know if she’d been out for a few seconds or a few minutes, but it probably wasn’t very long. She regained her senses when someone called her name. Her sense of hearing returned to normal, and she could make out the noise of open flames and the periodic sound of something small crumbling somewhere very close by. Air so hot it hurt surrounded her.

“Kieli! Hey, answer me!” Harvey’s voice reached her from behind something. It was a very panicked tone, one she didn’t normally hear, and after wondering as to its cause and thinking of how unusual it was, her thoughts finally arrived at her own situation.

Black smoke and fallen pieces of iron dimmed her vision, but she perceived a faint red in places that were enveloped by flames. She had curled up and fallen over sideways; the spot just around her and the triangle hats at her feet was the only place that avoided the falling rubble, as if a hole had opened up.

She moved her head a little to look. The robot was on all fours, shielding the area above her head.

The rubber that covered the right side of its face had melted off, and the metal cranium had started to melt as well and begun to cave in. It looked even more distorted and ghastly than before, but Kieli couldn’t take her eyes off of it and stared up into the eyes of the robot, who seemed to want to say something to her even though it was an artificial creation.

“What do you want to tell me…?”

The robot didn’t answer Kieli’s question, only protected her, standing over her like an unmoving, four-legged iron tower.

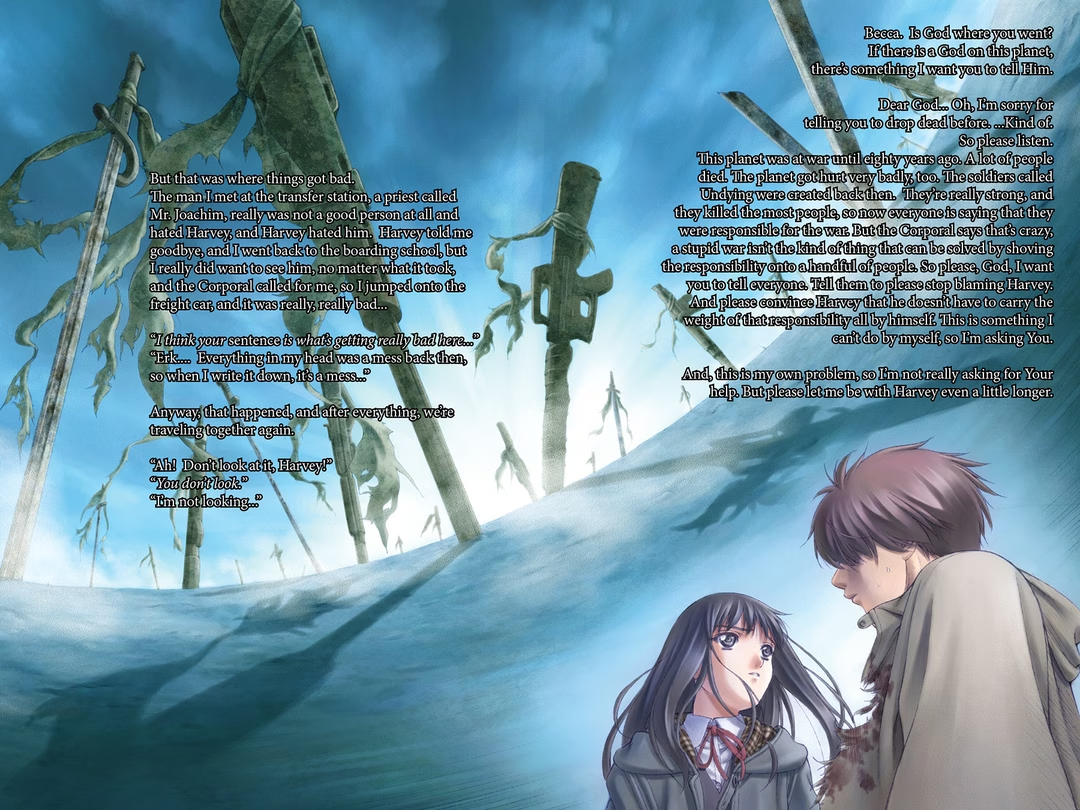

“Kieli! Answer me, I’m begging you…” Harvey’s voice reached her from the outside for a third time; Kieli gasped and turned her head in his direction.

“Harvey, I’m here! I’m okay…,” she yelled partway, but as soon as she inhaled, smoke filled her throat, making her cough violently.

Meanwhile, she heard the sounds of rubble being moved away from the other side, and a dull light shone through to her. The light was behind Harvey’s face as he peered in at her, and though she saw it for only a second, his face bore an expression that was difficult to describe, something she had never seen before. If she had to put it in words, it was as if he was about to cry.

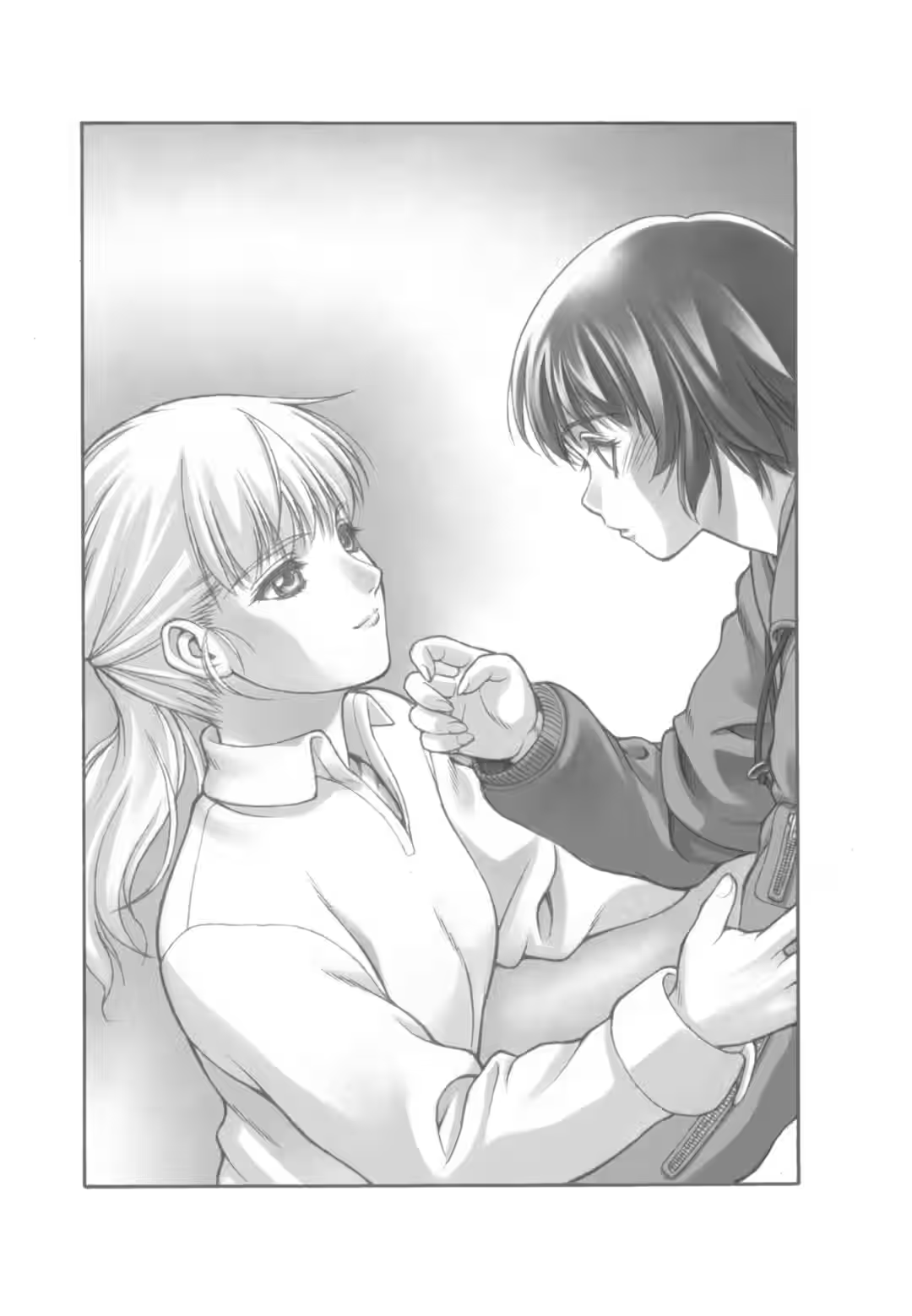

He reached his hand out to her, and she clung to it; he grabbed her hand tightly in return and pulled her out.

She kept going and fell into his chest, then lost all her energy and collapsed, inhaling deeply to let some breathable air into her lungs. “Are you hurt?” She heard the short question from above and responded by shaking her head. Harvey rested his chin on the crown of her head and took a very long, very deep breath. Kieli couldn’t move her head for a while; she turned her eyes upward and gazed at his collarbone.

Then she gasped and turned back to the mountain of rubble, which was still bursting with flames. The piles of scrap metal around the furnace collapsed as the blaze engulfed them; it was starting to spread to the walls and ceiling. They didn’t look like they would last long.

“I’m fine; hurry. This way.”

She looked back through the gap in the rubble that she had crawled through. The robot was still planted there in the same pose as before. The fire wrapped around its metal frame and was starting to dye it red. “Hurry! Come out, hurry! You’ll melt!”

The robot raised its face slightly. It looked around with its naked eyeball. When it found the triangle hats fallen at its feet, it reached out one of its robotic arms and picked one of them up. It put the limp doll on the palm of its hand and held it out to her, as if entrusting it to her care when…

Maybe it couldn’t support the weight of the rubble anymore—the arm it was supporting itself on crumpled at the elbow.

“Ah!” As a reflex, Kieli leaned forward to take the doll, but heard, “Get back, stupid!” Right before her fingertips touched the tip of the triangle hat, she was grabbed from behind and dragged backwards.

Fwoom…!

A whirl of flame spun up behind the robot with the sound of an explosion. Hot wind blasted her face and mussed her hair, but Kieli forgot to turn away and stared in wide-eyed amazement, clinging to the arm that Harvey wrapped around her torso.

Before her eyes, flames swallowed up the robotic arm reaching for her along with the small face peering out from under the triangle hat. Perhaps her sense of hearing had gone numb—nothing from that moment entered her ears, as if all sound had vanished from the world.

Beyond the collapsing rubble, enveloped in fire and smoke, the dolls quietly disappeared.

Fhoooo…

She heard the long, low sound of the steam whistle riding on the sandy wind.

As the dark blue-gray night sky changed to the pale, sandy color of morning, Kieli walked over the smoky ruins of the fire.

The soles of her shoes trod rubble that still smoldered in places.

The reserved voices, mixed half with relief and half with fatigue, of people who were cleaning up after putting out the fire, reached her like white noise. The residents of the industrial district noticed and came running right away, so only the part of the shop with the furnace at its center burned down before they extinguished the blaze; the whole of the building was only half-burnt, and the conflagration didn’t spread to its neighbors. But as the owner of the house was deceased, they would probably just demolish it.

The tip of her shoe tapped against something. She lowered her gaze and could barely see the tip of a yellow triangle hat peering out of the rubble. She bent down, moved the debris out of the way, and carefully picked up the doll’s torso.

Its scorched head broke off at the neck and rolled onto the ground.

“……”

Kieli pursed her lips and, for a while, looked mutely at the small body still in her hand. Its arms only dangled listlessly from the sleeves under its sailor collar; they would never again give the adorable sailor salute they had given her last night.

“Sometimes strong feelings for its owner will give something a soul when it didn’t originally have one. Like, so they can fill their debt of gratitude to the person who took such good care of them, or, on the other hand, maybe sometimes it can be because of a grudge or hate or something,” the low, staticky voice of the spirit possessing the radio murmured as it hung from her neck.

“Like how a spirit can possess a radio…?”

“I guess. You could say it’s similar, except that the spirit doesn’t come from a dead person.”

The dolls here must have been very well loved by their owner when he brought them into this world, and even after he went on ahead of them, they lived here the whole time, reproducing the scenes from when they still had their master. If Kieli hadn’t visited last night and things hadn’t ended up like this, they would probably have kept doing it as long as the shop existed. Whether they would have eventually found happiness that way or if it was better that they were destroyed last night, Kieli didn’t know.

She heard the dry sound of someone shuffling through the debris behind her. She turned her head to see Harvey, both hands (the one he had and the one he didn’t) shoved into his coat pockets, walking toward her, running a casual gaze over the burnt remains.

“It’s about time we get to the harbor.”

“…Yeah,” Kieli said, nodding, but stayed crouched on the ground for a little while, looking down at the doll’s limp body. Then she lay it softly down so that its triangle-hatted head touched the ground.

She stood up, turned on her heels, and chased after Harvey, who had already started to walk away.

Rustle…

She heard the sound of rubble crumbling somewhere. “……?” She stopped in her tracks and turned around once more. Just then, part of the mountain of debris swelled up and collapsed, and an arm with a metallic frame poked out from the scattered refuse.

“Ah…!” thinking the robot was okay, Kieli happily started running toward it, but then gulped and immediately froze.

All that crawled out to the surface, pulling the rubble toward it, was one robotic right arm. The metallic frame had been twisted cruelly apart around the joint of the upper arm, and its severed cables dangled like antennae.

The arm crawled around the burnt remains, pulling itself along the wreckage with its five fingers, as if looking for the shoulder it was supposed to be attached to.

Beside Kieli, who could only stand frozen where she was and watch, Harvey stepped forward without saying a word. He walked toward it a few paces, then stopped. After wandering around the tips of Harvey’s shoes for a while, it started to climb up his leg like a beetle that had found its prey.

“Harvey…?”

Kieli’s breath stopped at the understandably chilling scene, but Harvey showed no sign of aversion and let the arm do what it wanted. When it had crawled up to about his knee, he bent down lightly and grabbed the robotic arm with his left hand.

As Harvey picked it up, the arm wriggled its five fingers even more, as if looking for something, but it gradually grew more docile in Harvey’s hand and soon stopped moving.

“Things like this can’t exist all on their own, and if they don’t have something to rely on, they can’t figure out what they exist for anymore. These guys probably wanted you to be their new master.”

“…And that’s why they tried so hard to keep me here…?”

She thought of the robot’s expression that looked as if it wanted to say something, and wondered if that was what it wanted to tell her…Engraving Harvey’s words into her heart, Kieli regarded his copper-colored eyes, almost completely lacking in emotion as they looked down at the robotic arm—suddenly she thought that a doll with a soul might be more like an Undying than a possessed radio.

Undying—a dead body that is given eternal life by the “core” planted inside it in place of a heart. Before, when she saw Harvey with his core removed he was exactly like a normal doll, with his soul taken out…

After accidentally calling the scene to her mind, she shook her head, panicking to brush it away.

“What are you doing?” Harvey gave her a questioning look as he returned, robot arm in hand.

“Nothing…” She shrugged at him in vague response but then felt that she was acting even more suspicious and faltered.

“It’s perfect, Herbie,” the radio’s voice interjected, saving her. “You were handicapped, right? Although you probably don’t have what it takes to be its master.”

“Excuse me for not having what it takes,” Harvey retorted, his eyes narrow, to the radio’s suggestion, one comment too many, but then seemed to consider it a moment before refocusing on the arm in his hand.

“…I guess it’ll do,” he murmured and sighed a complicated sigh blended with a wry laugh and some self-derision. Then, somewhat jokingly, he tried holding out the arm as though it was facing toward her for a handshake, and said, “I look forward to working together.”

Kieli hesitated a little, then offered her own right hand. The instant her fingertips touched it, there was a short whir of a motor, and the arm made a fist as if surprised; Kieli followed suit and pulled her hand back. “’S not gonna bite you.” Harvey laughed lightly, exasperated. She didn’t know which of them he said it to; he could have been saying it to both of them.

She reached out one more time, slowly, so as not to startle it. “It’s okay…,” she whispered quietly, and the arm opened its hand in understanding and timidly, softly took her palm.

“Hurry, hurry!” a girl urged her father. “Papa, if you don’t hurry, it’ll leave without us! Hurry, hurry!”

“You shouldn’t rush so much; it’s dangerous.” Her father’s voice came from behind her. His young daughter’s high spirits exasperated him, but he smiled drily, as if secretly enjoying himself.

The girl stamped her foot and waited impatiently for her father as he followed leisurely behind her, but soon she couldn’t take it any longer and started to run. The aisle was narrow enough to begin with, but now it was jammed with people coming and going, holding large bags. She weaved her way through them, ran up the iron stairs, her light footsteps ringing, and flew to the bright patch of outside light framed by a rectangle cut in the wall.

“Waah…!” Kieli and the girl flew onto the deck at almost the exact same time, and both cried out in excitement simultaneously.

The sand-colored sky opened out as far as the eye could see, and a flock of white birds spread their wings and flew comfortably along. The dry, sandy wind brushed through the girls’ hair as it blew past.

Kieli exchanged smiles with the girl who had, strangely, acted exactly the same way she had, and waved her hand lightly in farewell. The girl’s father arrived late up the stairs; she pulled him by the hand and ran toward the edge of the main deck overlooking the harbor.

Feeling a bit envious as she watched her go, Kieli peered through the entrance to the stairs, wondering what had become of her own companion. Despite all her beckoning, Harvey showed absolutely no sign of coming behind her. “Damn old geezer…,” the radio cursed quietly as it hung from her neck.

Fh-fhooo…

The steam whistle rang out long and low to announce their departure, and a vibration rose through her feet and reverberated in her belly. The thick smoke of fossil fuels spouted from the giant exhaust pipe in the rear of the ship, painting over the color of the sky.

Kieli turned and ran to the edge of the main deck, wove through gaps in the passengers who stood waving at the wharf, and leaned over the handrail.

Mechanics from the harbor and people watching friends and family leave lined up on the pier below, waving their arms. The sailors formed a line on the deck and responded with a salute. In a gesture said to have been passed down by the space sailors from the same pioneering age as the card game, they touched their right fists to their chests and thrust them forward—she remembered the dolls in the triangle hats from the night before and felt a prickling pain in her chest. Far, far down the barrier lining the coast, the promontory of tetrapods where she found the dolls the previous night looked like a small, white hill.

“Maaaster! Be careful! Maaaster!”

A shrill voice ringing out over the murmuring of the crowd broke Kieli’s concentration, and when she looked back, she caught sight of a plump woman wearing what appeared to be a maid’s uniform. She stood on the tip of the pier, waving a white handkerchief, tearfully shouting, “Master, Maaaster!”

The woman seemed so frantic that Kieli’s eyes were automatically drawn to the place the woman was looking, where she saw a boy standing at the edge of the deck close to the boat’s bow. Dressed from head to toe in formal clothes that must have just arrived from the tailor that morning, he was the very image of the son of a well-to-do family; she had no doubt that this was the boy the woman in the maid outfit was waving to.

The woman cared not a whit for appearances as she cried out to the boy, and he responded with curt whispers like, “Whatever, just go home,” and made gestures to shoo her away, but his voice wasn’t loud enough to reach the woman, so he was probably only trying to hide his embarrassment from the surrounding passengers. Kieli giggled and studied the boy’s profile. He looked like he was a few years younger than she was—a little over ten. His well-kept, light brown hair looked silky and soft; Kieli put a hand to her own short black hair and thought, Come to think of it, I haven’t given it a decent combing in a while. On top of that, it was all dry from being exposed to the wind in the wilderness.

When the pier was far enough away that no one could make out the faces of the onlookers, the passengers gradually started retreating to their rooms.

The last voice she heard was the maid woman’s piercing shriek echoing out, and, regardless of what the boy said, he seemed reluctant to leave the main deck. Once her calls, too, faded, though, he left the handrail and turned away. A woman in a high-quality, but not flashy, dress walked very close beside him. She was a beautiful woman, with hair the same light brown as the boy’s done up in a bun; she must have been his mother.

Just in time to replace the boy and the woman, Harvey finally came up onto the main deck. He passed by them at the entrance to the stairs and did a double take for a second, turning to look at the mother’s back, but immediately returned to his usual blank expression and approached Kieli.

“You’re late! We can’t see the harbor anymore,” she said, frowning. Harvey dismissed it with, “Whatever. I don’t need to see it,” and grimaced in annoyance at the sandy wind that blew through his hair, ruffling it playfully. But then he looked up at the sand-colored sky spreading above his head and—it was so subtle she couldn’t have made it out without looking very carefully—narrowed his eyes as if he was enjoying himself.

“Those birds only have one leg,” he murmured, his face still raised. Kieli blinked for a second then followed Harvey’s gaze up to the air above. A flock of about ten sandy white birds flew above them, almost blending in with the color of the sky.

Harvey didn’t say anything else, and just as she was wondering, puzzled, whether or not he was going to continue the topic he raised, the radio, determining that there were no people around, piped up: “I heard once, a long time ago. Something about their genes mutating while they were being carried to this planet on the colonization ship so they got to be one-legged.” In the corner of her mind, Kieli wondered if by “a long time ago,” the Corporal meant when he was still alive.

“They’re migrating birds that wander all over the planet, all year long. In the winter, they go south; in the summer, they go north. Apparently the birds rest their wings for a bit on the tip of a tetrapod or the edge of a sail, then go right back to flying. They almost never sleep.”

“They keep flying without sleeping? Don’t they get tired…?”

“Dunno. ’Sprobably just how they are.”

“Hmm…”

He could say that, but she still thought that flying all the time without stopping would be hard. They looked so calm in flight, but maybe they were really exhausted and wished they could fall fast asleep somewhere.

His expression erased, Harvey’s gaze stayed fixed on the sky above; he didn’t show signs of moving from that spot for a while, so Kieli took just half a step closer and looked at the sky with him.

“Well? How do you feel about your first day on a boat?”

“It’s the worst,” Kieli answered Harvey’s spiteful question shortly and shoved her face in her pillow.

“It’s because you get so excited and jump around so much.” Even the radio at her pillow sounded exasperated. She turned her face away, pouting that even the Corporal was against her, and for a second, her eyes met those of the passenger lying in bed a little way away.

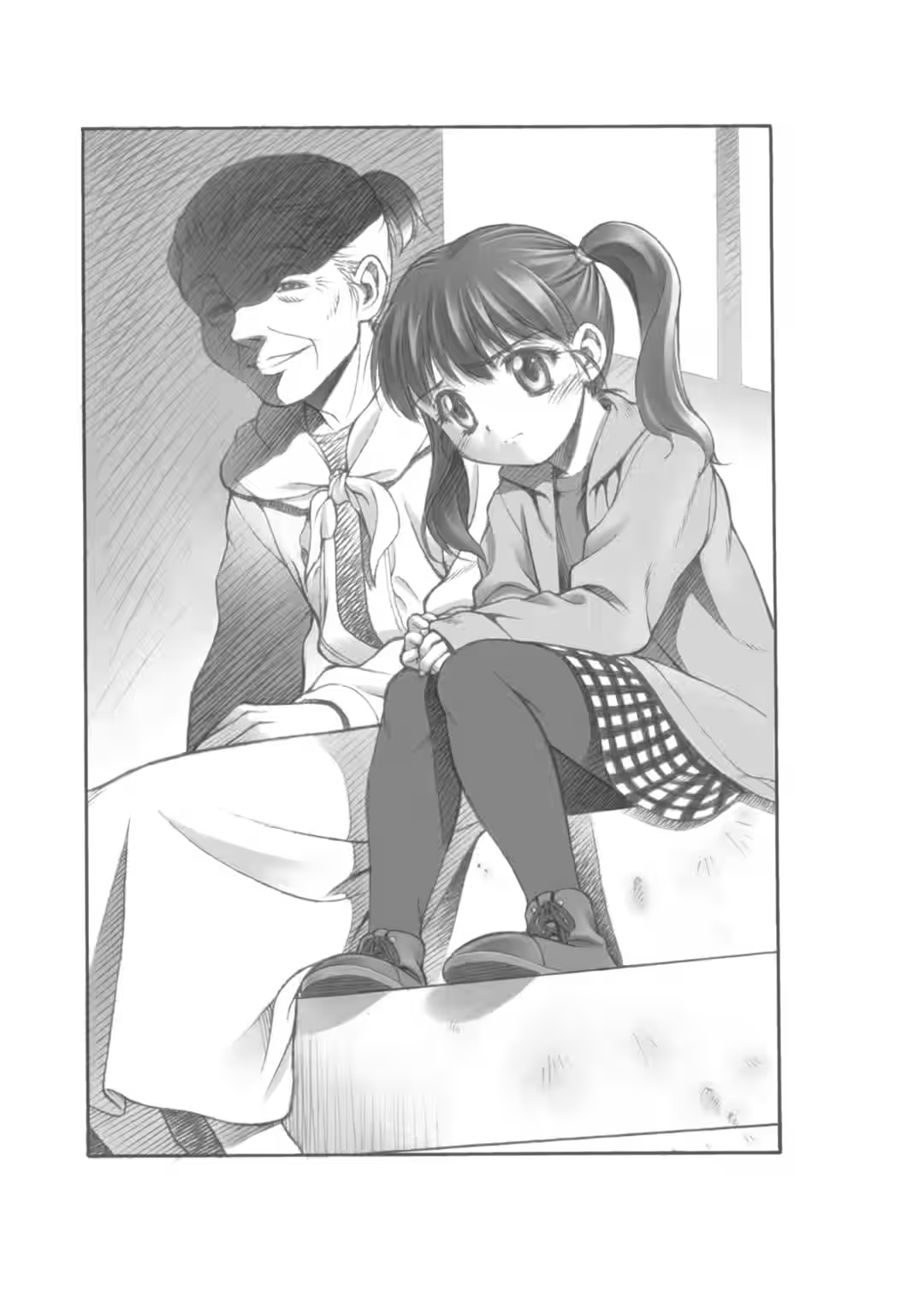

The third-class quarters on the ship weren’t individual rooms like the first- and second-class rooms, but group rooms, situated on the lower levels of the boat. Bunk beds lined either side of the center aisle; there were sixteen divisions in all, and a mix of about twenty people and mountains of luggage, which took up more room than each person, were shoved into each division. They were divided into upper and lower levels, so the ceilings were extremely low, and even Kieli had to duck a little in order to stand up, which meant that of course Harvey had no trouble hitting his head—actually, when he first came in, he hit it very spectacularly, raising a pretty murderous sound.

Harvey crept at random into a corner of the lower lever of the fourth division by the wall where they could see the ocean through a round porthole, so that officially became the sleeping place for Kieli and company for their ten-day ocean voyage. It was a small space, just big enough for the two of them to lie down in the cramped group sleeping room, and on top of that, the pillows and blankets provided were certainly not good quality. Even so, compared to their travels in the boxed seats of a train, it should have been a relatively pleasant journey, in that they could sleep normally.

It should have been. When she thought that these circumstances would go on for ten days before they reached the harbor on the opposite shore, even Kieli’s high spirits from when they set sail turned to utter exhaustion.

Because they were half forcing their way against the waves of flowing sand, the ship swayed irregularly, vertically and horizontally, throwing them in confused semicircles. Adding insult to injury, the low sound of the engine came from under the floor, incessantly echoing under her belly. She didn’t think she was especially prone to motion sickness, but she felt absolutely terrible from right about the time she’d eaten lunch in the ship’s cafeteria.

“Don’t puke over there. I’m begging you.”

“…I know.”

Still lying down, she sent a hateful stare at Harvey and his heartless, unsympathetic comments. She wondered what Harvey had been doing, sitting by the round window—he tried to light a cigarette but couldn’t control his right arm very well yet and ended up battling with it. The metal framework fingers that peered out of the end of his coat sleeve were holding the lighter just like human fingers would, but they would not move at all how he wanted them to, and only seemed to be trying to burn their master’s bangs.

“Why aren’t you cooperating?” Harvey asked, glaring narrow-eyed at his right arm, and, instead of answering, the arm threw the lighter away. “Now look, you!”

“If I were to guess, I’d say he’s trying to tell you that Kieli’s got a hard enough time as it is—don’t make the air any worse,” the radio explained knowingly, and, in perfect timing, a playful tune came from its speaker.

“Oh, be quiet!” Kieli murmured, unable to take any more, and crawled out of bed. “I’m going to get some fresh air…”

It was the middle of winter, but the wind from the south was just cold enough to feel good and stroked coolly against Kieli’s flushed cheeks. As she leaned on the deck’s handrail and breathed the outside air, she began to feel much better.

The scenery that spread out on the other side of the rail was an endless ocean of flowing sand and a partly cloudy sky of the same color. At the far end of her vision, the two blurred into each other, forming a fuzzy horizon.

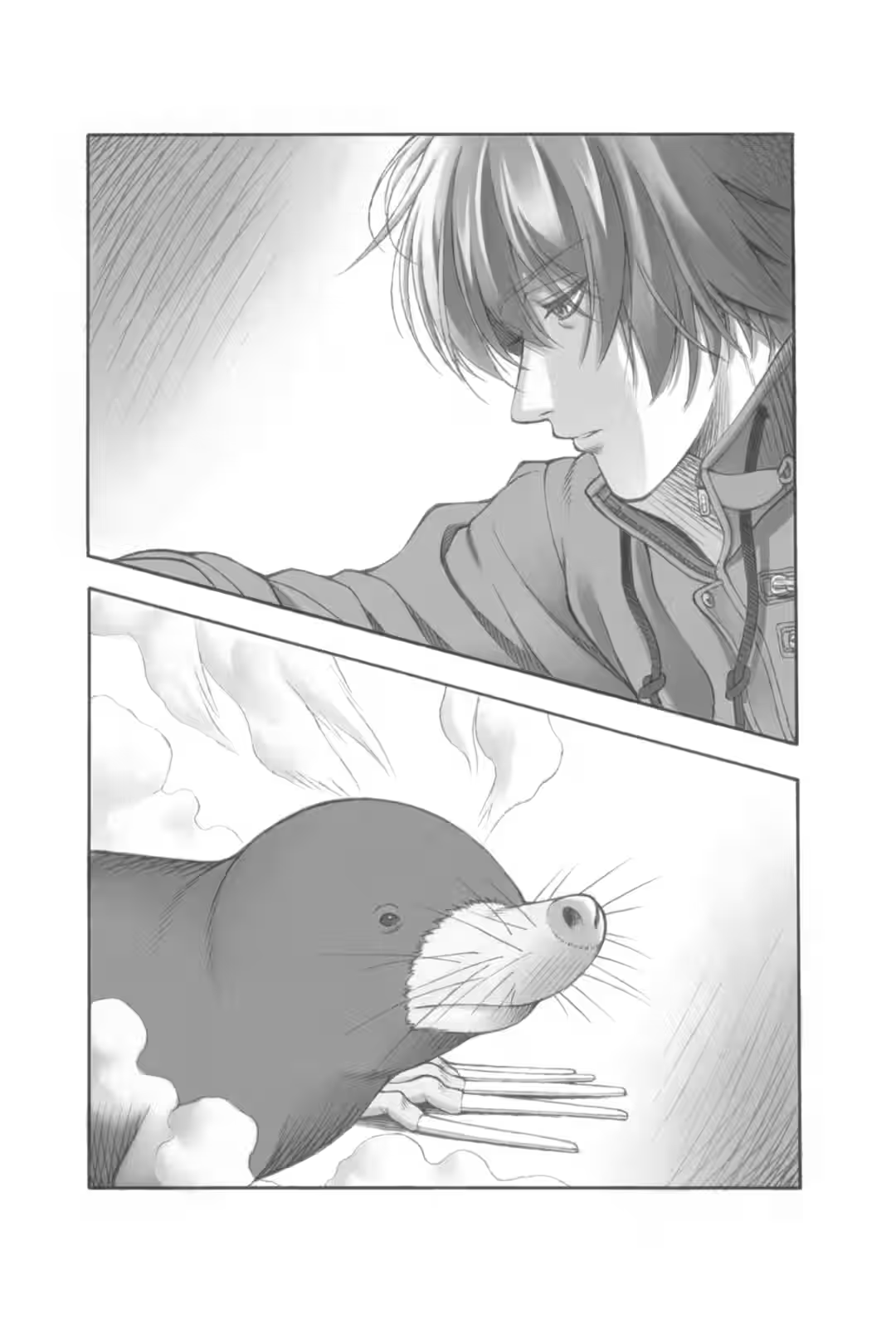

The steamship that was taking her to South-hairo in the southeast was called The Sand Mole’s Seventh Son. Apparently a sand mole was a creature that represented good luck in the Sand Ocean. The boat was ridiculously big, but the fuel tanks containing the extremely inefficient fossil fuels took up much of the ship’s bottom, so despite its enormous size, it didn’t have much usable space.

She could hear the sound of the screw propellers turning in the back of the ship, kicking up sand. A giant lump of metal, spewing billows of smoke as it dashed across the sand—that was the impression Kieli had of sand ships. Making full use of the main screw and several subscrews installed in the stern, it brushed aside the resistance from the flowing sand and forced its way over the surface of the ocean.

Near the bow on the opposite end, she could see a few of the crew in work overalls cleaning the deck. She casually focused her attention on them and watched them work, when…

Fwump…!

A familiar, vague sound flew to her ears. She only heard it faintly over the noise of the rotating screws, but that chilling blast, like something compressing the air heavily and releasing it all at once…

A carbonization gun…

The scene at the winch tower at the abandoned mines, when the Church Soldiers in their white armor blew Harvey’s leg off, revived in her brain, and Kieli froze automatically, searching only with her eyes for the direction of the sound.

She heard another gunshot and turned her gaze in its direction to see a small person standing at the edge of the deck near the stern—when she recognized who it was, she doubted her eyes for a second. It was the boy she had seen when the ship set sail, the one the woman in the maid clothes had watched go. Using the deck’s handrail for support, he had the uniquely shaped gun, with its fat, stocky barrel, trained toward the ocean.

She looked at where the gun was pointed and saw a flock of those one-legged migrating birds, flying low above the ocean.

“No!” Kieli shouted out of reflex and ran toward him. “Stop, don’t shoot!”

She tried to capture the gun from behind but missed and ended up shoving the boy away. “Aah!”

“Waah!” The boy came dangerously close to going over the rail and falling into the ocean; she grabbed his clothes and hurried to pull him back up.

The two landed on the deck in a heap on their rear ends, and the gun flew away and clattered across the floor.

“What are you doing!?” The boy pulled himself up immediately and tried to pick up the carbonization gun.