Seized by a sudden sense of déjá vu, the boy looked up.

His eyes traveled to the wall clock above the chalkboard without any real thought. It was an analog style of clock, a round face with its circle of unfriendly black numbers, framed by a black rim. It was just about as far from showing “personality” or “decorative flair” as one could get and still be in the same universe. 52, 53, 54…The slightly warped second hand crawled oh-so-slowly around the yellowing clock face, marking time sluggishly. 57, 58, 59—

The minute hand clicked forward. According to a system of time from a faraway planet that had been in use since the colonization era, it was 2:57.

…What was that? He felt as if he’d lived that exact same moment before, but when he really thought about it, 2:57 happened twice a day whether anyone liked it or not, so that wasn’t really so weird.

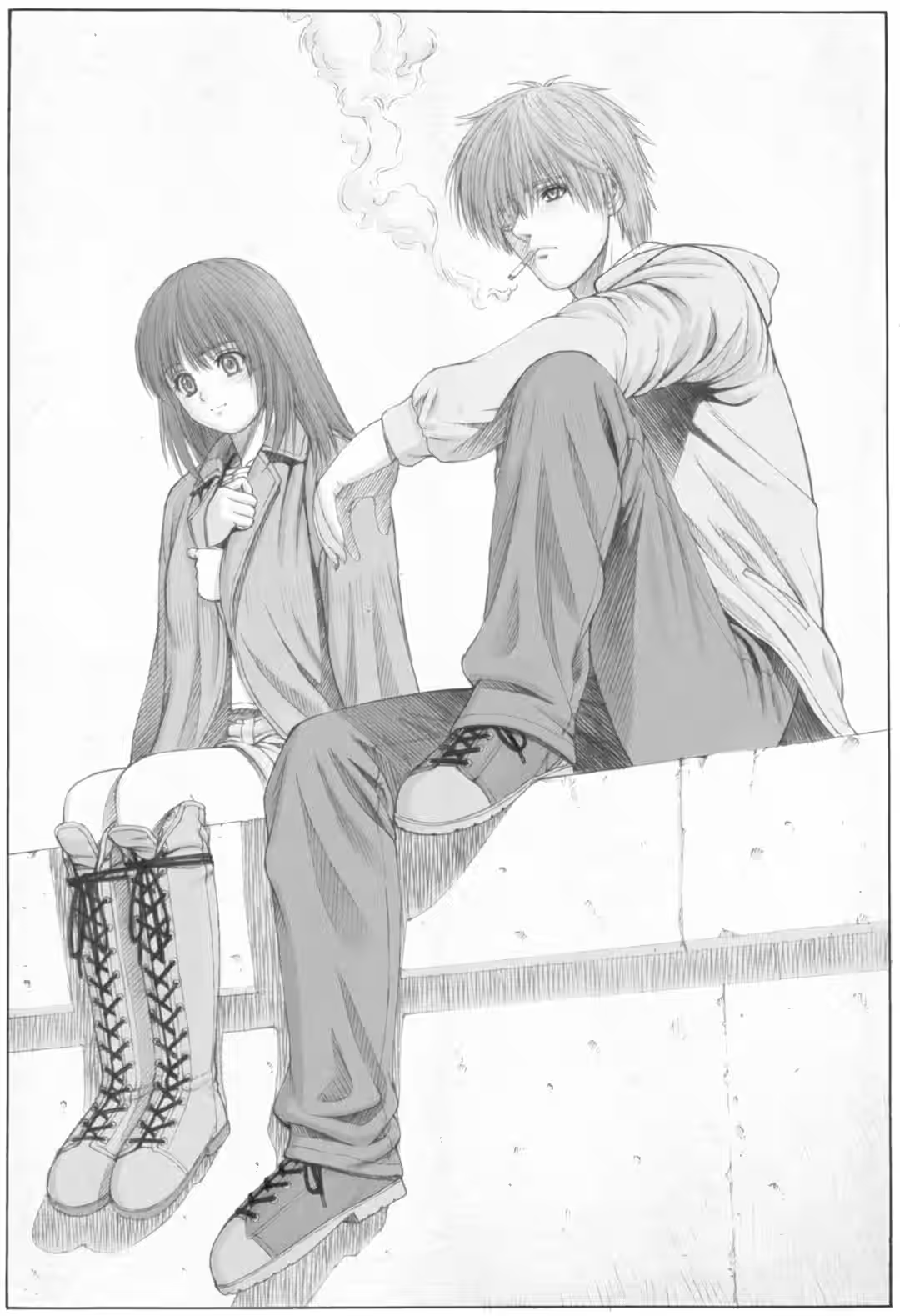

He only tilted his head in confusion for a moment before looking back down and striking his near-empty lighter a few times to get his cigarette going. Sitting on the teacher’s desk and swinging his short legs back and forth, he gazed at the white chalk scribbles that filled the board in front of him.

“Today Sarah and Nahar are on duty!” “←That’s wrong! Seth changed it!” “Elisha had another ‘accident’ today!” “No I didn’t!” “Joachim and Sarah were kissing under the stairwell!” And there was more: drawings, like the one of the twisting railroad line that ran from one end of the board to the other, and the ones of what he could only assume were girls, even though he got the feeling the human body didn’t actually work that way, and that tiny little note in the corner—

“Please let the war end soon so we can go home.”

He didn’t know to whom that faint, unpracticed handwriting belonged or when it had been written there. But for some reason, no matter how many times new doodles got drawn over the old ones, that one note was always spared.

When he stretched out his right hand and rubbed at the board with his palm, he smeared part of the railway sideways. Chalk dust stuck to his fingers. He thought he’d scribbled something here, too, but he’d forgotten which one was his. It must have been one of these. Any of them but the “Please let the war end soon” one.

In the afternoon the classroom was deserted and quiet. Outside the wide-open window stretched the same unchanging sky they saw every day, faintly blurred by clouds of sand. The chilly late-autumn air lightly stirred the column of smoke rising from the tip of his cigarette. It carried with it the innocent whooping of the young boys playing in the schoolyard below. Mixed in with their cries, he could pick out snatches of timid singing.

Not only was the voice too soft to really hear, it was also horribly off-pitch—but it was a melody he knew well, so he had no trouble recognizing it. It was some stupid old song everybody learned in first or second grade, no matter what school they went to. Something about an old man and a big grandfather clock and ninety years doing something-or-other.

Tick, tock, tick, tock…

It was a lispy girl’s voice. Must be Elisha. He could picture the youngest girl in his class squatting beneath the chin-up bars, drawing a picture in the sand there and crooning her favorite phrases from the song in clumsy but clear tones.

“Erase that,” ordered a grumpy voice from somewhere outside of his line of sight. He turned away from the schoolyard window to find a boy his own age standing outside the window that opened into the hallway. This boy with colorless hair and eyes the same blue-gray as the sky was the only friend his own age left in the whole school. Although that sure didn’t mean they actually got along…

He followed the direction of that slate-gray gaze to the chalkboard. The “Joachim and Sarah were kissing under the stairwell!” caught his eye. He tilted his head, considering this for a moment. “So you really were, then.”

“No, we weren’t.”

“Right,” he retorted, grinning. A pebble flew at him from the hallway, grazing his cheek.

“No, we weren’t!”

“Okay, okay. You’re so violent.” Whether it was true or not, somebody had probably written it there to hassle them. Seth or one of his buddies, most likely.

A faint smile still lurked at the corner of his lips around his cigarette as he looked around for the eraser. Not finding it, he just rubbed out the names with his hand. It didn’t seem worth the effort to wipe off the whole thing.

His friend stood in the hallway watching him, elbows propped on the window ledge. (Don’t just stand there, come in here and erase the damn thing yourself! he thought.) Then he said in an offhand way, “Oh, hey, I heard a bunch of tanks came up and parked by the western wall this morning.”

“Huh. Why?”

“Dunno.”

“And?”

“Eh, that’s all.” And that was the end of that. Just a meaningless little exchange.

He didn’t care about the tanks, but there must be a lot of soldiers there, and that meant maybe he could get some smokes. As he let that childlike humming about the old clock wash over him, he thought that maybe if he was lucky he could get some gum and little chocolates, too. Stuff like that would make good presents for Elisha and the other kids.

Maybe we should go visit the soldiers tomorrow. If the weather’s nice.

“See you tomorrow, then,” the other boy told him casually, even though he hadn’t said a word of that out loud. When he blinked and turned around, his friend had already pushed himself lightly off the sill and stepped away.

“Joachim —”

“What?”

“Nothing.” He hadn’t particularly thought of anything to say before he’d called out to stop the other boy, so he just echoed, “See you tomorrow.”

“Sure.” Joachim nodded, turning away. He silently watched his friend leave. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw the wall clock strike 3:00 on the dot. The long column of ash at the end of his cigarette fell and fluttered into his lap. The moment he looked down with a grunt of annoyance at himself, another flash of that weird déjá vu hit him.

He heard someone scream out in the schoolyard.

In the instant it took him to reflexively jerk his head up and slide off the desk, every windowpane in the building that faced the schoolyard swelled up in a distended bowl shape. A split second later, they all soundlessly shattered to pieces—well, maybe they’d made a sound, but the shock wave had ruptured his eardrums, and for a while the world was closed off in silence. A white mist filled the classroom, blanketing his vision and making him blind as well as deaf. He wasn’t sure if the mist was gun smoke or tiny shards of glass. The next thing he knew, the force of the blast had picked him up, and the side of his head was slamming into the chalkboard.

Body scraping down the board, he slowly sank to his knees on the podium. His eyes wandered vaguely around the room, almost without conscious thought. When they lit on the chalkboard, he saw a splattering of red over the drawing of the railroad, as if someone had thrown a paintbrush at it. He put a hand to his own temple. When he pulled it away, there on his chalk-stained palm was a thick smear of the same garish red. After a beat, he realized it was his own blood.

Now that his hearing was finally starting to return, he was assaulted by an awful, echoing wail like someone ringing a bell nonstop. The noise pounding at his brain made his head reel even more than the pain at his temple did. In some dim corner of his nonfunctioning mind, he just barely made out the first sound that seemed to have any meaning; it was his friend’s voice shrieking about something.

“— raim! Ephraim!”

Huh. That was his name the voice was calling. Joachim had been taking cover in the hallway; now the other boy was rushing to his side almost before he’d stood up. Ephraim didn’t see any reason for Joachim to look that desperate as he called his name—but what worried him a hell of a lot more was why he couldn’t hear Elisha singing anymore. He knew it would actually be weirder for someone to keep singing under the circumstances, but he couldn’t help his strange, stubborn belief that Elisha would.

Elisha’s time had stopped at 3:00, just like the clock on the wall, so she would never sing again.

This planet had teddy bears, but none of the animals called “bears.” Maybe they’d never been brought here on the colonization ship, or maybe they’d gone extinct because they couldn’t adapt to this planet’s environment. But at any rate, the people here had never seen bears except in old drawings or as stuffed toys.

So it was practically a miracle that Harvey was able to recognize that thing as a bear.

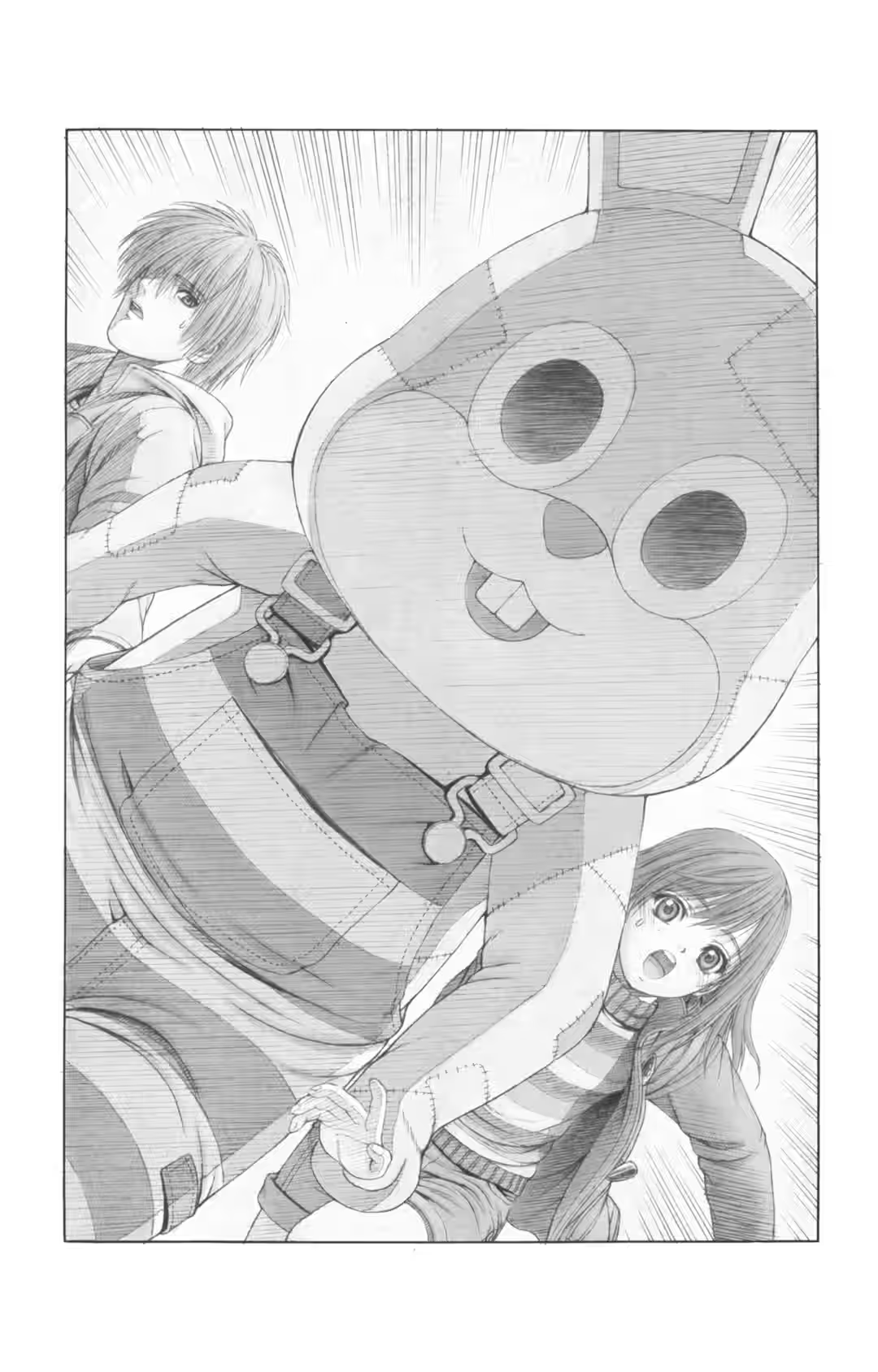

Its head was unnaturally large in proportion to its body, yet the round ears and plastic eyes were actually too small. It was made out of pink and brown patchwork cloth, and it was a head taller than Harvey—

—And it was standing right next to him, leaning against the train station wall. A cigarette poked out of its gaping mouth, which was carved in a permanent smile; and it was holding itself stiffly, looking absolutely despondent, when suddenly that round head swiveled unexpectedly toward him.

“Could I trouble you for a light?” a man’s voice asked politely.

Harvey fished out the lighter he’d been fiddling with inside his pocket to kill time and tossed it lightly toward the bear. Some instinct kept him silent.

“Thanks,” said the bear, deftly catching it in a sort of rough, careless pose of its hands (when Harvey looked closer, he realized the trick—there were finger holes in an obscure spot on the underside of each paw). The bear brought the lighter to the tip of its cigarette and was just about to click it when all its movements came to a dead stop again. Just as Harvey was wondering what the problem was this time, it yanked at its jaw with one hand to pry its head loose a little, resettling the cigarette into the human mouth now peeking out from under the costume, and lit it for real.

The man inside the bear (whose head was now smiling in a bizarre direction relative to its body) inhaled once and blew out a stream of smoke with a look of true satisfaction. Then he tossed the lighter back. “Just taking a break. This thing is heavy.”

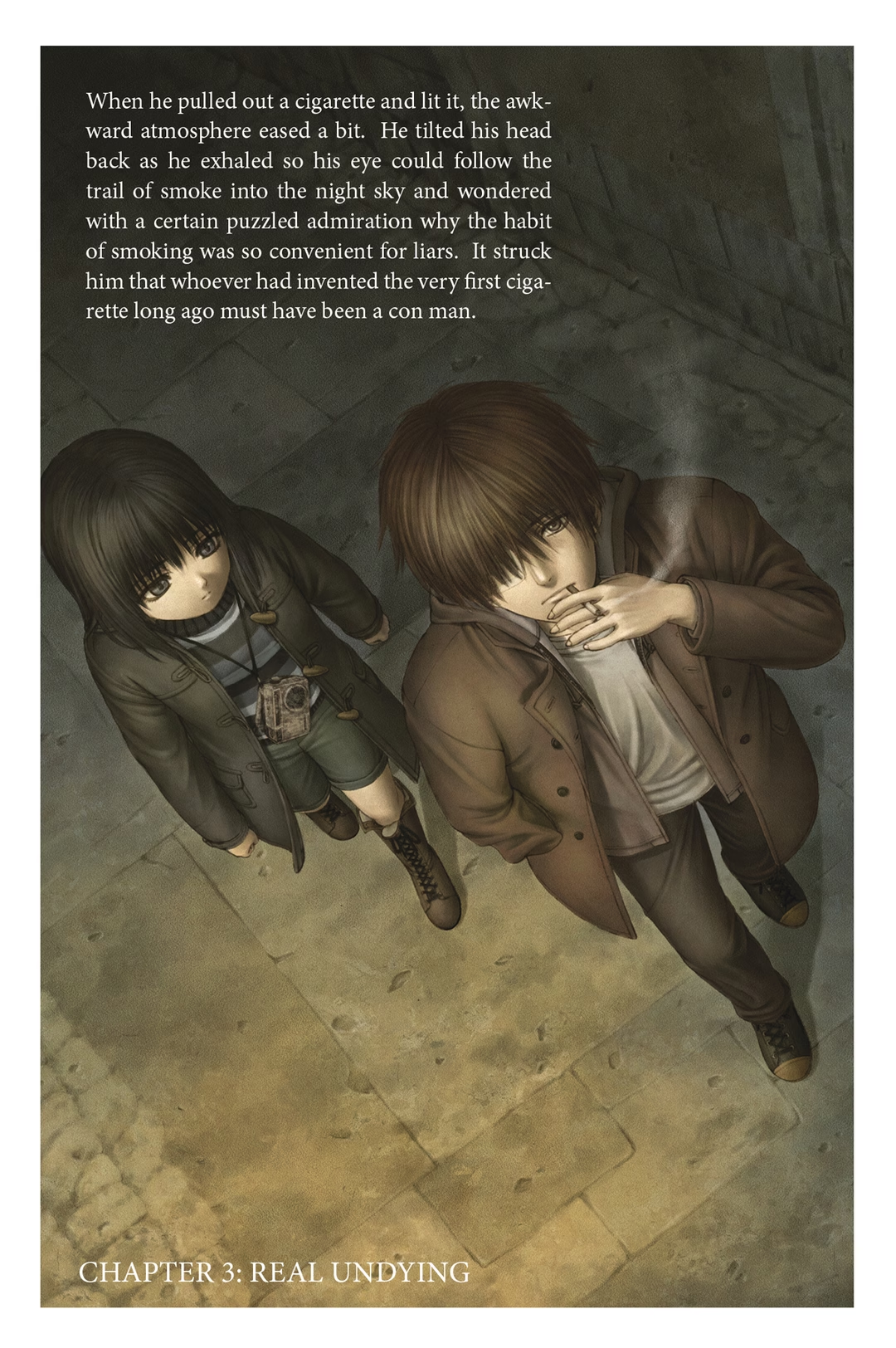

Harvey didn’t know how to react to that, so after a pause, he just made an apathetic “Huh” of acknowledgment and looked away, drawing out a new cigarette of his own with the corner of his mouth. All his movements up until the cigarette was actually lit were carried out with his left hand alone. It was a bit of a handicap, but then, he was used to it.

Through their cloud of smoke, he let his gaze roam the rotary in front of the station. Just as he was wondering to himself what a tall man and a giant bear suit rather placidly smoking side by side must have looked like to the rest of the world, he caught sight of a mottled pattern of pea-green and brown hopping up and down on the other side of the road. It was another animal costume made out of the same patchwork cloth as the bear, just in different colors. Harvey guessed it was supposed to be a mouse. A mouse that at the moment was waving both arms emphatically.

“Uh-oh, he’s pissed,” said the bear next to him, tossing his cigarette butt to the ground and pushing up off the wall. He ran off toward the mouse, adjusting his skewed headpiece as he went. That mottled pink pattern covered in striped overalls was garish enough to make Harvey’s eye sting, yet his floofy paws made his footfalls sound oddly relaxed.

Harvey let out a smoky sigh. “What was with him?”

“Yeah, I hate people who litter.”

“…That’s what you’re focusing on?” He felt as though there were a lot more fundamental issues with the whole situation, but whatever.

“This is what’s wrong with kids these days, this whole postwar generation,” groused a man’s voice, and the small radio on the floor by Harvey’s bag spat out a burst of dark noise particles in chorus. “Herbie —”

“That’s ‘Harvey,’” he corrected automatically. He could guess what was coming next, so he shifted a little to stamp out the tip of the cigarette butt with his foot before the Corporal could start harping on him to do it. “She’s sure taking her time in the bathroom,” he grumbled to no one in particular. With his back still against the wall, he sank into a crouch. When he absently looked up at the sky, he hit the back of his head against the bricks.

The sky above him was a hazy yellowish-gray from the fossil fuel smoke spewing from the exhaust pipes of the city’s tightly crowded jungle of buildings. When they’d arrived at the station just ten minutes ago and gotten off the train, the first thing to hit him had been the feel and smell of the smog. The city had one foot in the door of winter, but the smoke retained a faint warmth.

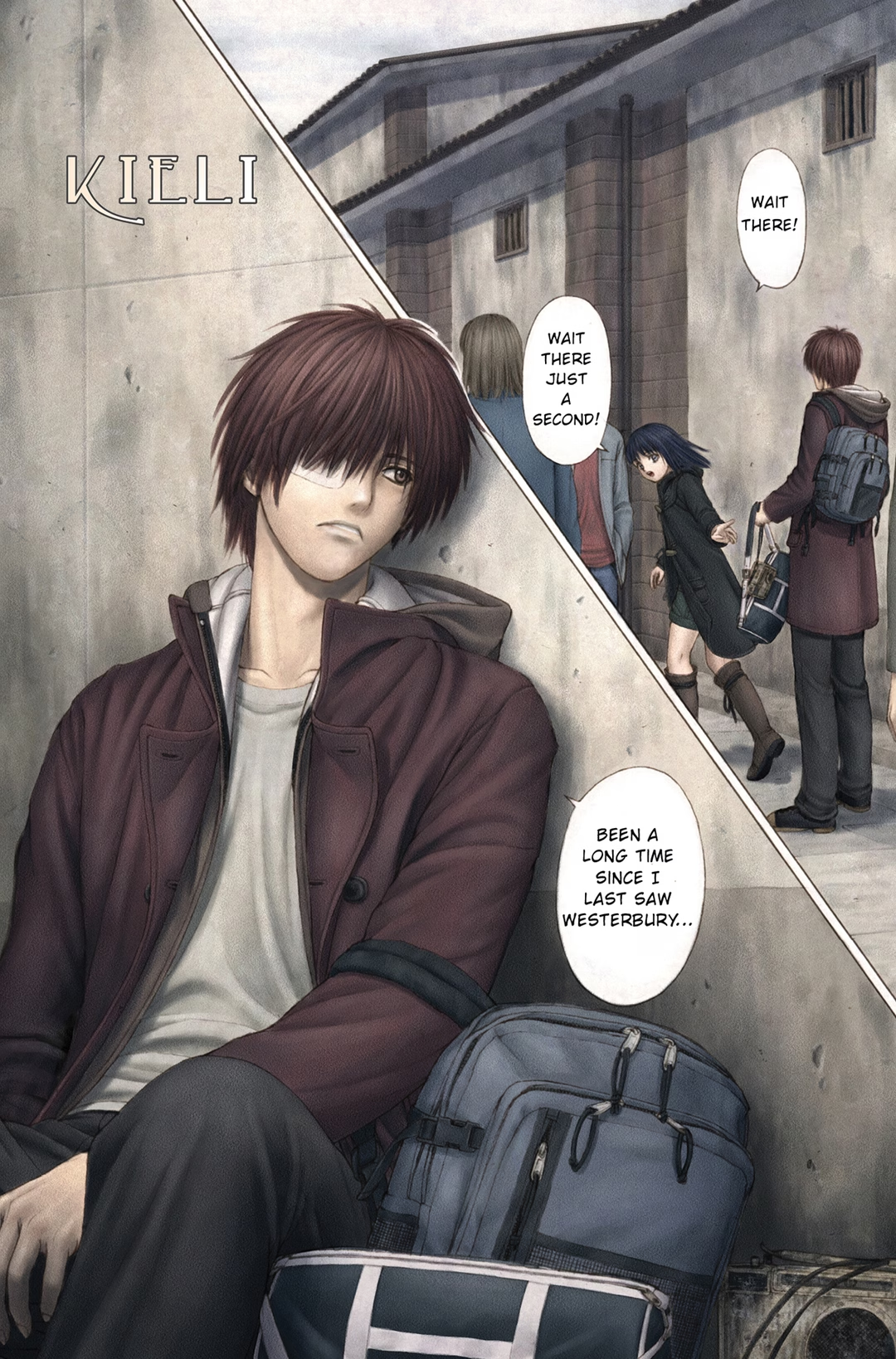

They were in Westerbury parish’s central city, the grand metropolis of commerce and tourism.

This was the only city in the whole wide world with three separate railroad stations to its name: East, West, and Central. East Station, where they were, was on the outskirts of town and was supposed to be at least somewhat smaller than the other two, but it was still alive with the hustle and bustle of a city, packed with people and cars and buildings.

Three-wheeled taxis with tubular fuel tanks on top lined the rotary. All the cab drivers were vying for customers, smiling phony smiles. Squat, box-shaped buses chugged slowly back and forth along the street beyond them, spitting exhaust. On the 3-D screens set into the walls of the buildings facing the station, the same video had been playing over and over for so long that Harvey half-thought he was being brainwashed. It showed a marching band of cartoonish mechanical dolls parading through a mechanical city toward a giant clock tower. At the end of the film a caption read, “South Westerbury Park: ‘The Whimsical City’ begins its long-awaited week of Colonization Days celebration tomorrow!”

Right underneath the screen stood the guys in the bear and mouse suits, improvising a little pantomime performance while they handed out balloons. A belated realization hit Harvey, and he blurted out an idiotic little “Ah!” before he could stop himself. “So Colonization Days start tomorrow?”

“You’ve been staring at that video for over ten minutes, and you’re just now figuring that out?”

“Eh,” said Harvey. He’d seen the words over and over until he was sick of them, but they hadn’t actually connected with anything in his brain. The Colonization Days didn’t really affect him one way or the other, so they’d slipped his mind somewhere along the line…but now that he thought about it, the city did have sort of a festival atmosphere to it. Though on the other hand, maybe Westerbury was always like this. “I picked a weird time to come here, then…”

Westerbury was noisy enough on its own; the thought of it getting even more crowded with tourists pouring in for the ten-day holiday seriously put him off. It was a lucky break for him in the sense that it’d be easier to go unnoticed, but searching for someone in all this chaos was just insane.

He saw a black truck pulling up to the station just in time to take the place of a three-wheeled taxi setting off with some rich passengers. Reflex made him lift a little out of his crouch on the asphalt, on the alert—the truck was miniaturized for city patrol, but it was definitely one of the Church Soldiers’ trucks. The Church Security Forces had a large base here in central city, so the Church Soldiers even had the city’s own security operations under their thumbs.

As Harvey watched, several white-robed soldiers climbed out and started walking toward the costumed performers under the big screens. A man who seemed to be the ranking officer—a platoon commander, maybe—started talking to the mouse in a stern voice. The mouse broke off his skit with the bear to answer him with an unconcerned smile (though, of course, that smile was just a part of the costume). It looked as if the troops were asking whether they had permission to be there.

“Looks like we should go somewhere else.”

Harvey nodded and stood up. “Yeah.” They should avoid any and all Church Soldiers for caution’s sake. At this point, he was way past having any particular feelings about that, but it was still a pain in the ass. He had just hefted two people’s worth of luggage onto his shoulder and started walking, radio dangling from his hand, when he heard a chorus of cheers from a different direction.

A bunch of kids had formed a ring around the rotary bus stop. They all held balloons that they must have gotten from the guys in the animal costumes. In the center of the ring was a bench with a lone girl sitting on it. Unlike all the other kids, she was hugging a patchwork teddy bear instead of a balloon. She glared up at them. They all looked older than she was.

“I heard this teddy bear’s the only friend she has!” said one especially large boy, beaming with self-satisfaction. The others took their cue from him and started jeering. Harvey couldn’t really judge the ages of the group, but the girl on the bench looked to be about five.

Normally he had zero interest in kids’ fights, but for some reason he kept watching them out of the corner of his eye. Maybe it was because it entertained him how much she reminded him of a certain someone—particularly in the stubborn way she was glaring up at them through her lashes and pressing her lips together as if to say No way am I gonna cry! even though she was obviously on the verge of tears.

“I do too have a friend!” All of a sudden she leapt off the bench and grabbed at the boy in the center of the group, seemingly at the end of her rope. It was so unexpected that the boy faltered for a second, but he was a lot bigger than she was, and he had no trouble pushing her away. After she landed on her butt on the ground, her face jerked in surprise. The boy had snatched her teddy bear. “Give that back!”

“Make me!”

She jumped up and tried to grab it back, but he held it high up out of reach. The bullies started passing it off to each other. The last one wound up and pitched it far away from her.

The smiling teddy flew in a high arc over the top of a bus pulling sluggishly into the rotary. The little girl flew out into the street after it without a second’s hesitation.

And right before Harvey’s eye, the hood of a three-wheeled taxi suddenly appeared out of the blind spot created by the bus as it tried to pass. He sucked in a sharp breath.

“Herbie, wait!”

The whole concept of the radio trying to stop him was so unlikely (if anything, he’d assumed it would be haranguing him to go faster) that he froze for just a moment. But then his body started moving again on autopilot, so that momentary reaction ended up having exactly the opposite effect from what the Corporal had intended.

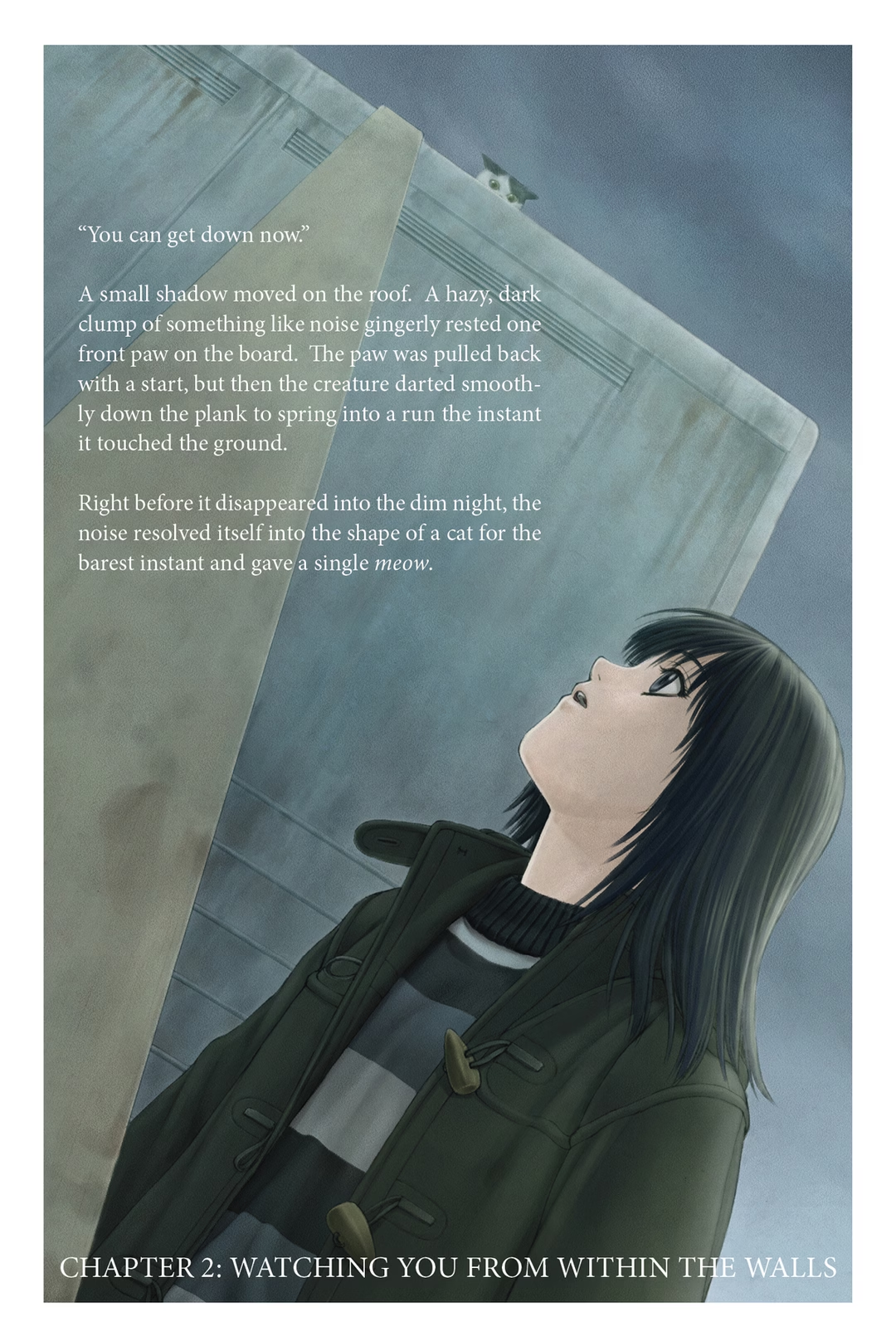

Kieli was watching a bunny do tricks when she heard the dull thud and the high squeal of brakes.

Well, the “bunny” was actually a full two heads taller than she was, wearing a costume of primarily yellow and brown patchwork cloth, and standing on two legs…When she’d come out of the restroom on one side of the station building, she’d found herself spellbound by its slightly precarious-looking balance ball act, clenching her fists and nervously holding her breath. And she was still standing there gazing when those two particular sounds came from the rotary.

An abrupt silence fell over the crowd, and then before long it grew noisy again with excited chatter and the sound of hurried footsteps.

Kieli was afraid something awful had happened. She flew around the corner of the station and looked left and right. People were starting to gather around a spot near the bus stop. Local boys, travelers passing by, bus and taxi drivers fresh out of their vehicles—everyone was standing at a careful distance from a figure on the pavement, staring at it with timid, ashen faces. A head of ruddy copper hair lay limply on the ground, and a bloodstain was spreading on the gray asphalt beneath it.

For a second she forgot to exhale. Then all her breath shrieked out of her in a shocked “Harvey!” as she took off toward him in a stumbling run.

Darting her way through the crowd, she knelt beside the fallen man. “Harvey, are you okay? What were you —”

Harvey sat up unsteadily. “Ugh. That hurt…,” he mumbled, in the same mildly annoyed voice other people would use after nicking themselves with a letter opener. Blood was pouring from the side of his head down his right cheek, but he ignored it to look down at what he was carrying. That was when Kieli first noticed the little girl cradled protectively in his left arm.

The girl didn’t seem to get what had happened. She just stared bewilderedly up at him, blinking at the sight of the blood covering half his face.

There was a blank pause. Then with no warning, the girl’s young cheeks twisted, and she began to cry. Kieli wasn’t sure whether she was hurt or scared by the blood or just surprised, but at any rate she was suddenly wailing loudly, and neither Kieli nor Harvey had any idea what to do.

As they were exchanging looks of despair, a pair of sturdy white boots came up to stand beside them. “Are you all right?” said a voice from overhead. They tilted their heads up at the same time to look and immediately stiffened.

An armored soldier in white was peering into Harvey’s face. Once he’d examined the young man’s injuries, the soldier’s rugged glove grasped him by the upper arm. “First things first, let’s get you to a hospital. Then I’d like you to come down to the station and tell me what happened. Can you walk? Come on, get in the truck.”

“No, wait—really, sir, I’m fine!” Harvey bluffed hurriedly. It seemed as if this soldier with his relentless, one-sided speech might drag him off before he could protest. Kieli ended up with the little girl by default. She held the child on her lap and called out after the two, trying to help. “Wait, sir! Please wait!” But another soldier took her by the arm and hauled her to her feet saying, “You two come along, too.” She scanned the crowd in search of help, but their other traveling companion, the radio, had been left by the station-house wall with the luggage. They were penned in by the platoon of troops, no escape in sight.

Then, just in the nick of time, a completely unexpected person came to the rescue.

Or maybe it would be more accurate to say a completely unexpected animal.

“Oh, I’m sorry. My apologies, sir,” said the yellow bunny politely as he cut through the crowd toward them. It was the bunny from the balancing act. His mask wore an oddly mismatched expression, mouth curved up in a smile that somehow didn’t quite reach his wide, plastic eyes. When he reached them, he faced off against the soldier, who looked about the right age for a platoon commander. “These young people are with my troupe. We’ll take him back to camp with us and patch him up.”

“That’s fine, but we still need to interview them about the accident —”

“No, please, don’t worry about it. We all have plenty of physical training, so one little car accident is nothing for us. We’re so very sorry for all the trouble this fuss has caused you,” rambled the bunny, cheerfully but firmly taking charge of the conversation. Then he turned somewhat harshly on them and snapped, “Come on, rookies, we’re going home.” He seized Harvey by the arm, practically tearing him from the soldier’s hand. Then, still holding Harvey, he grabbed one of Kieli’s arms, too, extracting her from her own soldiers (who were so bowled over they let her go without a fight).

Harvey looked up at the bunny’s profile. Kieli heard him murmur something in a stunned, scratchy, almost tearful voice. “…Shiman…?”

The dim evening sun bore down on her from behind, giving her a long shadow. Kieli darted through the cluster of trailers as if she were trying to catch up to her own shadow as it moved along the ground.

They were in a rural suburb on the southeast edge of the city. It was different from the well-maintained urban area they’d come from. This was just a wide empty space of nothing but bare, rocky ground. All kinds of trailers were scattered across it in clumps. They looked like a herd of giant animals napping together, grouped into little family units with the children huddled up against their parents.

She trotted past the trailer that held their water supply and circled around the back, coming out into the makeshift watering place to find a tall, skinny young man sticking his head under the spout to wash his face.

He looked up at the sound of her footsteps. “Harvey, your clothes,” she began, but the radio hanging from her neck started yelling before she could finish.

“Why do you always have to pull this crap?! I told you to wait, didn’t I?! Don’t just go off getting hit by cars the second we get into town! Pay more attention to what you’re doing! How old are you, five?!”

“It’s not like I was playing in traffic. You don’t have to give me hell over it,” Harvey grumbled, sounding fed up. He moved to wipe his face off on his bloodstained sleeve. Kieli hastily offered him the towel she’d brought. He accepted it with a terse grunt and started sloppily rubbing at his face and hair.

Apparently he’d cut the side of his head. It had bled a lot, but he’d just given her the same old unconcerned look as usual and brushed it off as “only a scratch.” It didn’t seem closed yet, though. Faint red splotches were popping up on the white towel.

“I meant to dodge it, you know. You’re the one who tried to stop me. It’s your fault I didn’t make it in time.”

“Don’t jump into the street if you don’t think you can make it!”

“Yeah, right. If some kid died right in front of us, you’d bitch at me for not saving her.”

The radio made a distinct gulping sound.

“What do you want from me? You’re always demanding the moons.”

“. . .”

Things were starting to look ugly, so Kieli broke in. “U-Um, hey, let’s get you changed. The troupe leader was asking for you.” The radio reluctantly clammed up, though it clearly wasn’t finished yet. Harvey subsided with an irritated little click of his tongue. Then he began to change his clothes right there, apparently not caring that they were in a public place, particularly since nobody was really around.

First he reached his left hand around behind his back and pulled off his parka and T-shirt in one tug. His bare torso was so bony it was almost skeletal, but still, the muscles were masculine and well-defined. Even though it wasn’t the first time Kieli had ever seen this, she felt her heart thump a little, and she looked away as she accepted the dirty clothes and handed him a fresh shirt. He put this on with just his left hand, too.

Harvey’s right arm was gone now. A ruined scrap of metal framework and cables bit into the stump of upper arm visible at his T-shirt sleeve, dangling there and cutting off around the elbow.

It was Harvey himself who’d suggested cutting it off, since it “wasn’t useful anymore.” The prosthetic had worked its way deep into the living flesh, so there was no way to cleanly and completely remove it without cutting off some more of his real arm. And since that was definitely out of the question (though Harvey had seemed to be actually considering it), they’d ended up leaving a little of the metal there instead.

They’d buried the amputated arm in a grave behind a bar on the parish border—Kieli had rescued it from being left on the curb in the hazardous waste container on trash day (and it had been a close save!). When she’d protested that treatment as cruel, Harvey had answered flatly, “But it’s just a thing.” That was his only response, but afterward he’d gone out to the back garden alone and hadn’t come back for a while.

They’d left Gate Town, the waterway city and the gateway to the capital, a little over three weeks ago to return to the North-hairo parish border. Once there, they’d availed themselves of the bartender’s hospitality for a while. The burial had taken place during their stay.

And now they were here in Westerbury looking for someone.

Kieli watched Harvey fumble one-handed with a fresh square of protective tape, trying to peel it from the backing. “Give me that. I’ll do it,” she said, snatching it out of his hand. “Turn this way.”

“I can do it myself.”

“Turn this way and bend down.” She grabbed his arm and pulled him around to face her before he had a chance to say no. Harvey looked unconvinced, but he silently leaned his tall body down a bit for her.

When she reached out to brush the coppery bangs away from his face, she could see the unnaturally sunken lid of his right eye. He flinched when she touched it with her fingertips, so she quickly drew them back and placed the square of tape over it. It had a thin pad on its underside; they’d been using it lately because it drew less attention than something more obvious, like gauze or an eye patch.

Apparently it was going to take a while before his missing eyeball grew back completely. The “protective tape” was less to protect him than to keep him presentable. The caved-in eyelid looked a little awful.

Harvey probably thought the Corporal’s chewing-out was just annoying. That was the kind of personality he had. But if you asked Kieli, anyone would have told him the same thing. Not only was he down one arm and one eye, and therefore in far from peak physical condition, but it was finally striking Kieli that Harvey had a genius for everyday injuries—today being the perfect example. The fact that he didn’t really care since they’d heal up soon enough anyway (which she had to admit they usually did) just made other people, like Kieli, worry that much more.

Once she’d finished with the tape, she reached up to finish toweling his hair, which he’d hardly managed to dry at all. “You’ll catch cold like that.”

“I said I’m fine. And I don’t catch colds.” This time he really did bat her hands away, looking peeved. “Look, I’m not a kid, so —”

But then his face went blank, and he broke off and stared at something behind her.

The instant Kieli turned to look, the two figures who’d been peeking at them around the corner of the trailer jumped in surprise and vanished out of sight again.

“You want something?” demanded Harvey with obvious distrust. Kieli heard the sounds of people prodding each other in whispers before they came back out into the light. Their footsteps sounded soft and muffled.

The shapes outlined against the darkening sky were so bizarre—short-legged with giant hands and feet, no waists, and disproportionately tiny heads—that Kieli gaped for a moment, but she quickly recognized them and relaxed.

They’d taken off their headpieces, but otherwise they wore striped overalls over patchwork bodies in different colors. It was the mouse and the bear. Inside the costumes were two men who looked about the same age as Harvey.

The mouse leered at them and scratched his head with a costumed hand. “Sorry, man. We figured we shouldn’t interrupt your fun.”

“What do you mean, ‘fun’?” Harvey asked, furrowing his brow suspiciously. Next to him, Kieli let out a little squeak and took a step away. It was hard to tell whether he didn’t get what they meant, or he was deliberately ignoring it, or what, exactly. He just glanced at her reaction and then indifferently shrugged off the subject. “And? Did you want something?” he repeated with his usual curtness. The mouse’s face fell a little in disappointment, but he recovered himself and made a vague gesture with both hands. Costumed hands, naturally.

“Come play cards with us. The boss said you’d make it an interesting game.” It was only when Kieli heard this that she figured out the gesture was supposed to be one hand holding cards and the other hand drawing one out.

She privately wanted to warn them that Harvey would make it a crushing defeat, actually. But on the other hand, she hadn’t seen him play in a while, and she wanted to, so in the end she didn’t say anything. Harvey seemed surprisingly enthusiastic. He appeared to think about it, and then quirked the corner of his mouth up in a slightly evil smile (maybe only Kieli noticed it). “Sure, all right.”

“Okay, let’s go. We’ve already started.”

The mouse led them along the trailers, and the bear walked next to them, explaining, “We start the real work tomorrow, so tonight’s the pre–Colonization Days party.” They both strangely resembled their animal characters. The mouse was blunt and quick-tongued; the bear had a sort of easygoing air about him.

According to what they said, the balloons and the performance in front of the train station were part of the promotional campaign for Westerbury’s big tourist attraction: the theme park. Someone had once told Kieli that Westerbury had something called “hands-on theater.” Apparently they’d been talking about this theme park, which was called “South Westerbury Park: The Whimsical City.”

In addition to the park’s standard attractions, for the ten-day-long Colonization Days holiday that started tomorrow they were going to hold a special carnival. Circus troupes on-site and off-site would be doing songs, dances, and street performances, so all kinds of circuses from all over the world had been invited. They’d banded together in this southeastern suburb and set up camp. One of them was the troupe of dancers and street performers to which the mouse and the bear belonged.

Their troupe leader was that bunny who’d been balancing on the ball outside the station—he was an old friend of Harvey’s, and even though Kieli had never met him before, he’d already heard of her, which surprised her. As they shook hands, for some reason he’d told her “Thank you.”

The hub of troupe life was a set of four medium-sized trailers. Only the leader had a light truck all to himself. They were probably playing their card game in the trailer where all the men slept, or else at a table set up in the clearing in front of it.

When they turned the corner of the trailer and came out into the clearing, Kieli heard the hushed sound of someone singing. The faltering tune didn’t quite come together into a real song. It almost sounded like someone just muttering to himself.

There was a particular snatch of lyrics that was pronounced with odd gusto, so Kieli could make out that one bit. Maybe it was the only part the singer remembered.

“Tick, tock, tick, tock…”

In one corner of the clearing, someone had made a sort of makeshift sandbox marked off with a square of concrete blocks. A little girl crouched inside it, clutching a patchwork teddy bear and digging at the sand with a little scoop as she crooned the “tick tock” song.

It was the girl Harvey had saved. She was the daughter of one of the female dancers, and the troupe leader said she was the only child they had with them right now. She’d tagged along with them to the train station today because she had no one to play with.

“Hey, Nana,” called the mouse. The girl abruptly stopped singing and looked up. She fixed them with such a blatantly wary stare that Kieli winced a little, but the mouse seemed used to it and cheerfully kept on talking. “You’re singing weird songs again, huh?”

“…It’s not weird. My friend taught it to me.” Nana scowled.

He snorted a laugh. “Uh-oh, here we go with the ‘friend’ thing again! It’s always ‘my friend’ this, ‘my friend’ that.”

“. . .”

“I feel sorry for your mom, what with her only daughter talking all crazy like that.”

The girl had been biting her lip and staying mum, but this was too much. “It’s not crazy!” she shrieked suddenly, standing up and dashing toward them before Kieli had time to blink. She ran right by them without looking, whacking the mouse’s costumed shin soundly with her plastic shovel as she passed him. He yelped and jumped. “You dumb mouse!” she spat before tearing off to the other side of the clearing.

“Dammit, that little brat!” the mouse hissed, hopping up and down on one soft foot. Kieli guessed a lethal weapon like that made an impact even through the costume. “It’s your fault for teasing her…,” sighed the bear in exasperation. Kieli stood a little ways away from the pair and stared stupidly after the girl. Instinct made her look up questioningly at Harvey.

He beat her to the punch and shut her down before she could even say anything. “Don’t ask me, I don’t know.”

However, she could hear a faintly staticky voice coming from the radio’s speaker.

“Tick, tock, tick, tock…”

He was probably singing it more than an octave lower than the girl had, but it was the same tune—no, it was far more precise, and now she could actually make out the melody.

“Corporal?”

But as soon as she spoke, he stopped.

“So you know that song.”

“Yeah. It’s an old song,” he whispered softly, but so happily that Kieli was taken by surprise…and a little sadly, too, somehow. “I bet they don’t even teach it in school anymore, huh? But there’s nobody in our generation who doesn’t know it. Right, Herbie?”

“I don’t.”

Harvey’s blunt answer was like a bucket of cold water thrown on the Corporal’s nostalgia. The radio fell silent for a minute, deflated.

“…Of course you know it. Everybody’s sung that song at least once as a kid.”

“I told you, I don’t know it. Why are you getting on my case about it?” She could see his mood sour right in front of her eyes at what he considered persistent interrogation, and she was a little afraid they’d fight again. The Corporal must have been only too painfully aware of that side of Harvey’s personality, though, so he didn’t push it. But he didn’t seem satisfied, either, and Kieli heard him grumbling wordless static for a while afterward.

It had been ages since Kieli had last seen the familiar sight of Harvey showing off his perfect poker face and sweeping good luck with cards (Kieli was pretty sure he used up all his luck on cards), yet somehow managing to make stupid mistakes out of the blue and lose everything at the last minute. That night she watched the card game up close until somewhere along the line she fell asleep.

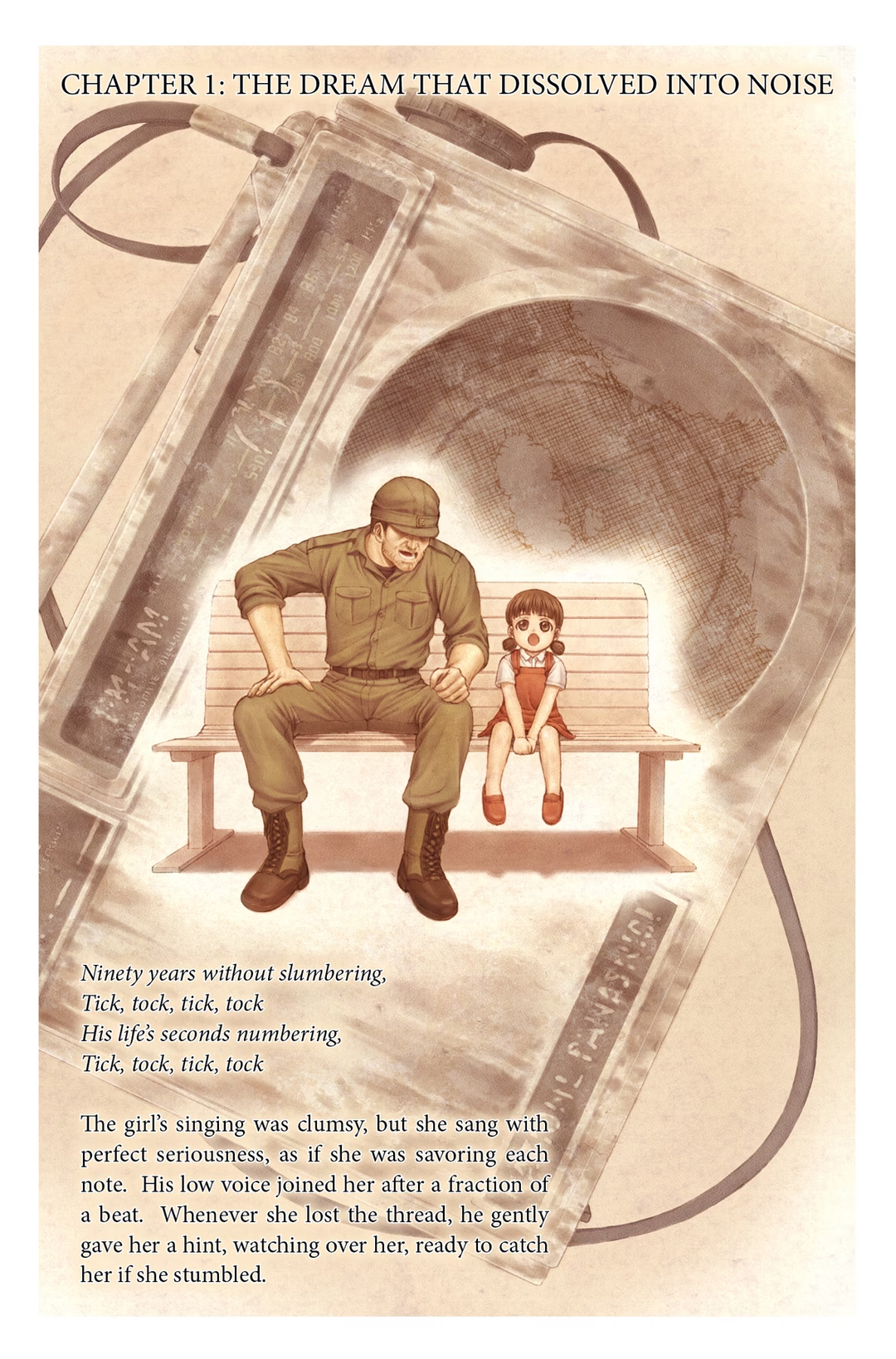

“Tick, tock, tick, tock…”

She could hear someone singing. An innocent, childlike girl’s voice. But it didn’t seem like the same girl she’d seen in the sandbox last night.

She was hitting the pitches better than last night’s girl because another voice was singing with her, helping her. It was a man’s voice, seasoned and a little deep.

Ninety years without slumbering,

Tick, tock, tick, tock

His life’s seconds numbering,

Tick, tock, tick, tock

A little girl and a man in a military uniform were sitting together on a bench. It stood against scenery she’d never seen before, all of it bathed in soft, milky-white light. Toys were littered everywhere. A doll in a red dress, a blue sand shovel, a small green chalkboard…all of them were old and faded, but they radiated warmth.

Am I in a park…? No, this looks like someone’s backyard.

The girl forgot the words to the next verse and got stuck. When the soldier told her just the first line, she promptly started singing again in clumsy but clear tones. His low voice joined her after a fraction of a beat. Whenever she lost the thread he gently gave her a hint, watching over her, ready to catch her if she stumbled. But inside he felt impatient, and he couldn’t help wanting to meddle even more. Kieli could tell, and she thought it was funny.

“It’s gotten chilly out there. Why don’t you come inside?” called a woman’s voice from the house. She sounded kind.

“Sure,” answered the soldier, standing up from the bench. When he turned to look at the girl next to him, she was holding up both arms beseechingly. He smiled. “What am I going to do with you?” He bent over a little and started to pick her up—

—When crackling black noise particles began filling up the white light, and the world fizzled out.

When Kieli opened her eyes, she saw a low gray ceiling overhead.

Where am I? She turned her head on the lumpy pillow to look left once, then right once, and then remembered that she was in the trailer where the women from the troupe slept. Her memories of the night before were kind of fuzzy, but she had the idea that Harvey had carried her here, and that in her half-asleep daze she’d heard him ask someone to take care of her.

The back door of the trailer had been left half-open, letting in thin beams of sand-colored sunlight. It looked as though the sun was high in the sky already. Everyone else had long since gotten out of bed. All the other pallets were empty, already neatly stacked against the wall.

Oh no, I overslept! Kieli pushed herself up on one elbow. Her back immediately creaked painfully where it had been pressed against the hard cot all night, but her headache was even more awful. “Ow, ow, ow…,” she moaned, clutching her forehead. Her head was pounding.

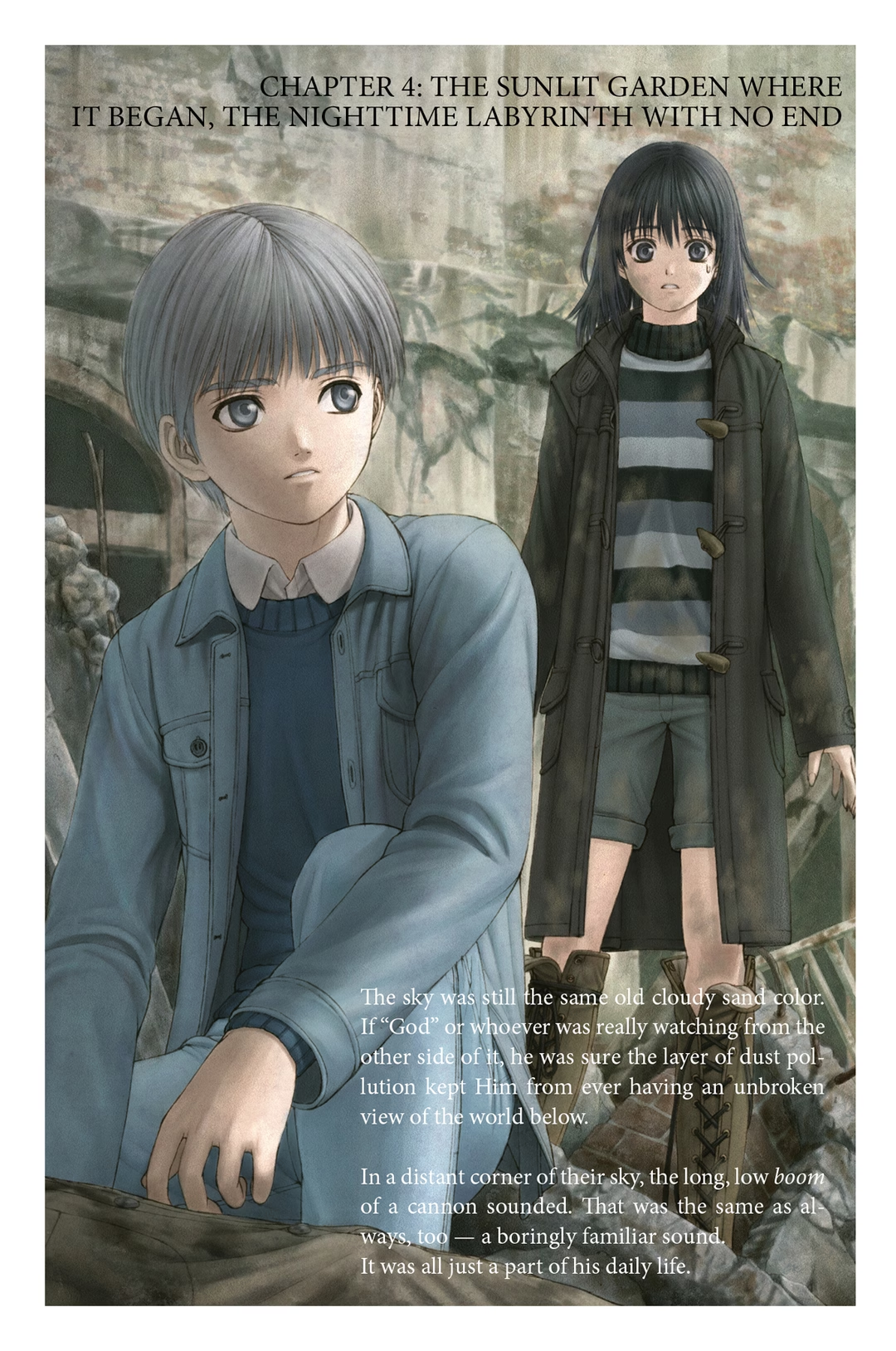

She was wearing shorts and a sweater with horizontal stripes. She must’ve fallen asleep in her clothes yesterday, but as it seemed like too much trouble to change them right now, she just smoothed out the worst of the wrinkles and made a perfunctory pass at flattening her hair before stumbling off to wash her face.

Cold air bit into her cheeks when she stuck her head out the back door. She could see her own breath. Winter was stealing steadily over the wilderness, and here outside the city where there was nothing blocking the wind, it was pretty cold even in the daytime. She drew back inside and put on her trusty old duffle coat before sitting on the doorsill to pull on her boots. While she was still tying the first boot lace, she heard a voice coming from somewhere around the side of the trailer. Oh, good, someone’s here.

It had been so horribly quiet outside that she’d been afraid maybe she’d been left here all alone. The performances at the park were starting today, so the troupe would have left for work a long time ago.

Kieli hurriedly finished doing up her boots and hopped down onto the ground, jogging around the corner of the trailer to peek into the clearing. The space that had been so bustling with performers last night was deserted and quiet now, but she could see two figures squatting in the sandbox. One short, one tall…

The short one was Nana, the girl from last night. And the tall one was—

Kieli gave a little burst of laugher before she could help herself. Harvey, Harvey of all people, squatting there and playing in the sand with that absolutely blank look on his face…She giggled again.

“That’s wrong. Make it taller and skinnier.”

“You can’t make something like that out of sand.”

“But a castle tower is tall and skinny!”

“This thing is a castle? I can’t even tell.”

“It’s a castle! This is the clock tower, and then we’ll do the gate, and the throne room, and the king’s bedroom.”

“You’re kidding. Let’s make something else. Something that’s not all complicated like a castle.”

“You’re just ham-handed, Herbie.”

“Yeah, you’ve just got ham hands, Harry.”

“…That’s ‘Harvey.’”

It wasn’t like a conversation between adult and child at all. They spoke on exactly the same level. It was hilarious. Nana wore a jumper and a big, cozy-looking cape, and Harvey had layered a half-length coat over his parka, though below them he just wore his usual work pants. His empty right sleeve was tucked into his coat pocket, and his right eye was taped over as always. On top of the concrete blocks that lined the sandbox sat a tin watering can and a portable radio. Placed next to each other like that, they both looked like toys.

Just as Kieli was resolving to watch them for a little longer before calling attention to herself, she realized something important.

Didn’t the radio just talk like normal? Right in front of Nana?

While she was standing there stunned, Harvey noticed her and lifted his head. “Good morning,” she said automatically.

“Hey there, hangover girl,” Harvey answered, his face animated by just the hint of a taunting smirk. “This is what you get for tossing it back like that just because it tasted sweet.”

“Ugh…quit picking on me; I didn’t know!” Cradling her head, which was still throbbing dully, she walked over to them and crouched down next to Harvey. “What are you doing?”

“Shiman made me babysit.”

“Looks to me more like she’s letting you play with her,” jibed the radio. He really was talking as if it was natural, Kieli realized with horror. But when she shot a glance at Nana, the girl didn’t seem particularly surprised or anything. She just silently went about building a mountain out of sand with her shovel. If anything, she seemed put out at having Kieli interrupt their little threesome (well, twosome plus radio).

As Kieli wondered, bewildered, if maybe Nana had decided to hate her, Harvey stood up and said, “Okay, switch,” as if it was time for a shift change. And she’d just gotten there, too!

“Hey, what do you mean, ‘switch’?!”

“I’m going into town.”

“To see the informant, right? I’m coming, too.”

“I told you, he left us with the babysitting.” He was always conscientious at the weirdest times.

“But—but I want to go look for Beatrix, too.”

“You’re staying here today. You promised to do whatever I say, right? If you won’t listen, go back to the bar right now.”

She gulped and clammed up. Harvey was being pretty obstinate about his orders, for Harvey, and she didn’t have anything with which to answer back.

Looking for Beatrix was the whole reason they’d come to Westerbury. She was still missing. Kieli hadn’t seen her at all since North-hairo. They’d waited at the bar on the parish border for a while, figuring that if she was okay she’d contact them there, but even after almost two weeks there was still no word. That was when the information peddler they’d asked for help (that man who ran the cigarette stand) had come to them with a rumor that there was an Undying in Westerbury. It was just a rumor, though, with nothing hard to back it up. Harvey hadn’t been enthusiastic, but Kieli had stubbornly insisted that if there was even the smallest chance, she wanted to look there, and in the end, he’d reluctantly let her steamroller him.

However, he’d given her conditions: I’m letting you have your way on this, so while we’re in Westerbury you have to do what I say. Don’t go doing your own thing and making trouble. Don’t cause me any problems. If you do, I’ll send you straight back here.

…Apparently she’d totally lost his trust by getting herself involved in so much trouble all the time.

“Harry, you’re not gonna play anymore?” Nana called after him in her babyish voice when he moved to leave the sandbox. She didn’t try to stop him with tantrums or pleading; she just fixed expressive eyes on him.

Harvey stopped for a moment and turned back. “Nope,” he said casually. “Play with her now.” He jerked his eye toward Kieli.

Easy for him to say, but he was putting Kieli in a bind. She wasn’t used to playing with little kids in the first place, and she had a feeling it’d be even harder to make friends with one who seemed so cranky. For one thing, Nana sure didn’t seem to like her as much as she liked Harvey.

Kieli looked up at him imploringly. He dropped his left hand to the top of her head and ruffled her hair lightly before he dismissed the whole issue with a careless, “You’ll be fine. You’re birds of a feather.” Hey! That’s so irresponsible! Then he turned on his heel and started to climb over the blocks of concrete.

This time the radio stopped him. “Wait a second. What about me?”

“Huh?” Harvey stopped one more time and glanced down to the machine at his feet. He was starting to look pissed off. “You’re going to stay here with her, obviously.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. I’m coming along. You can’t be left to your own devices. You’re an injured man with no self-awareness.”

“You just keep playing with them,” he snapped. “I’ll be fine on my own.” He plunged his left hand into his pocket and strode briskly away. This time he paid no attention when the radio shouted after him to wait. Was it only Kieli’s imagination, or did it almost seem as though he was running away?

“Dammit, that idiot just won’t listen…”

Tilting her head in confusion, Kieli turned to look at the radio, which was still complaining. “Corporal —” she began, but Nana pointedly interrupted her before she could ask him if it was really okay for him to be talking.

“Corp’ral, let’s play!” She was glaring sullenly at the ground, digging roughly at the sand at her feet. Yeah, she definitely thinks I’m in the way.

There was an empty space where Harvey had been, so Kieli was crouching an awkward distance away from the little girl, and that distance was making things even more uncomfortable somehow. Though maybe it was only Kieli’s general discomfort around kids that made her feel that way…

She huddled into a ball, hugging her knees, and timidly asked, “Um, can I play, too…?”

Nana glanced up at her without raising her head. She still looked grumpy. “Do you know the song?” Kieli was lost for a second before she realized the girl was talking about the song from last night, the one about the clock. The Corporal had said that no one remembered it now. It was really an old, old song that had been around since long before the War, even.

She recalled the garden from her dream, wrapped in soft fog. That bench. She’d heard the girl and the soldier sing it in the dream, so she nodded, dragging the lyrics up from the depths of her memory. “A little.”

Nana’s eyes widened in surprise, as if she hadn’t expected Kieli to say yes. “Did my friend teach you?”

“Your friend?”

“From the park. She taught me the song.”

Kieli blinked. “Hmm?” Nana dropped her gaze again, looking disappointed. It seemed as if Kieli had betrayed her hopes somehow, but she had no idea how.

The radio sitting on the blocks took pity on her bafflement and clarified slightly. “Seems like she met an old ghost near the park.”

“She what?” This time it was Kieli’s turn to widen her eyes in surprise.

“Sometimes kids can see things adults can’t, even if they’re not all as sensitive as you.”

“Huh…” She turned her eyes back to Nana, who was digging up sand just two steps away from her. Ever since Harvey had left, she didn’t seem to be making anything in particular, let alone a castle. She just scooped up some sand, poured it on top of her little pile, and then repeated the process.

Eventually Nana said in a low voice, “Mama looked at me funny when I was talking to my friend. She asked me who I was talking to. Then when I told her to meet my new friend, she looked at me even funnier. Now I’m not supposed to go to the park while she’s working anymore. So I have to stay here.” Her eyes were still downcast.

Kieli silently gazed at the little girl’s profile for a bit. Then she pushed herself to her feet with a little grunt. She took two crunching steps across the sand and squatted down again next to her.

When she touched the dry sand at her feet, it felt faintly warmer than the cool air, and when she scooped it up in one hand it slithered through her fingers—it was just like the sand in the Sand Ocean. (She had to admit, it probably would be pretty hard to make a castle out of this sand, even for someone who wasn’t Harvey.)

“What should we make? But I have to warn you, I’m not very good at this, either.”

She was rewarded with another upturned glance, surprised but still suspicious. “…You’re not gonna laugh at me?”

“Why would I?”

“Everybody does. The people here, and the city kids, too. They all say she’s an imaginary friend. They say I went funny in the head ’cause I didn’t have any friends and I wanted one so bad.”

“There’s nothing wrong with you,” Kieli said, watching sand dribble from her fingers down to her boot tips. She knew it wasn’t a very good answer, but she’d never been a smooth talker in the first place, so she just said what came to mind as if it were a plainly obvious fact.

Nana’s eyes went big and round, though her expression didn’t soften. But before long she dropped her gaze to the ground again. She pouted, sticking her shovel upright in the dirt. “…I do have a friend.”

“I know.”

The conversation didn’t exactly pick up after that, but Nana did lend Kieli her shovel, and they started building the easiest thing they could think of: a sand mole’s nest. The two of them crouched there in one corner of the deserted clearing surrounded by trailers, facing each other across a little mountain of sand and digging together. Eventually Nana began softly humming the clock song. The radio sang along in a quiet, staticky voice. Kieli chimed in on the parts she remembered.

Ninety years without slumbering,

Tick, tock, tick, tock…

What came back to her now was something that had happened when she was a very little girl living in Easterbury. In the Sunday school at church, they had always had snack time after class. It wasn’t much, only some thin milk and a cookie, but everybody looked forward to it.

The teacher wasn’t a formal clergywoman; she was just a volunteer from the women’s club. Even when all the kids were eagerly raising their hands, she only ever called on her son, and then she praised him lavishly for his answer. (One day when he hadn’t raised his hand, Kieli had seen her yell horribly at him afterward: Why couldn’t you answer such an easy question?! You studied this just last night!) Hearing a woman like that talk about God and the Saints didn’t impress Kieli one bit, so she was basically going to Sunday school for snack time. Her grandmother hardly ever gave her extra treats at home, since she was one of those kids who spoiled her appetite for supper when she ate between meals.

One day at Sunday school, a girl about her own age sat next to her, and they hit it off right away. Normally the class dragged on forever, totally boring, but that day it went by in a flash. Then snack time came, and that girl was the only one not to get her milk and cookie.

Naturally, Kieli raised her hand to report this. “Teacher, you skipped someone.”

“Oh, dear. Who?”

“Anita.”

Looking back, she remembered the teacher making a strange face when Kieli pointed to the space beside her. Then the woman collected herself and gently admonished, “Kieli, everybody gets one cookie. You mustn’t be greedy and try to get more than the others.”

Pride hurt, Kieli said glumly, “It’s not for me. It’s for Anita.”

“…Listen, Kieli, I can understand that it must be hard living alone with your grandmother. But here, all are equal in the eyes of God.”

What the heck is she talking about? What do my grandmother and our home have to do with it? She’s the one being unfair, isn’t she? At that point, Kieli was struck so speechless with amazement that she couldn’t even feel resentful anymore. All the other kids watching her snickered to themselves.

When her grandmother came to pick her up, the teacher called her to one side and said something to her. After that, for some reason they started having snacks at home sometimes—and at school, even if Kieli honestly saw someone get skipped at snack time, she didn’t say anything about it.

She never saw Anita again. At the time, she’d figured the other girl must have moved away.

Kieli winced mentally. Even though she hadn’t been lying, thinking about it now made her want to blush. She had to admit that to anyone else, she must’ve looked like nothing but a stubborn, greedy girl.

Apparently from time to time, there were small children who could see “invisible friends.” Sometimes they existed only in the child’s mind, just like the adults said, and sometimes there was definitely something there that couldn’t be explained away as just a figment of the imagination—either way, they usually disappeared as the child grew older. But Kieli still had “invisible friends” even now. They were just facts of her life. There was her roommate from two years ago, the pretty, trouble-making tomboy with the blond hair and blue eyes, and there was the friend who’d stuck with her ever since that roommate had disappeared: the hypercritical, ever-worrying, sometimes-

helpful-and-sometimes-not spirit possessing the radio. (The Corporal referred to himself as her guardian, so maybe he’d get cranky if she called him a “friend.”)

“Hey, Kieli.”

“Hmm? Oh, more than a friend, of course!” she blurted nonsensically, startled.

If the radio next to her had eyes, he’d be looking at her funny. “Huh? I do get that already, you know.”

Kieli wasn’t sure what he “got,” exactly. It kind of felt as though he might have misinterpreted her as talking about someone else.

They were sitting side by side on the doorsill of the trailer and staring absently at the sky as it began to deepen into evening. With nothing else to do, she’d ended up remembering that embarrassing day from her childhood.

The comfortable sounds of medium-tempo music mingled with thin static flowing softly out of the speaker and faded into the late-autumn sky. It was too cold for them to play all day long in the sandbox, so they’d come inside. Nana had been playing with her teddy bear until a few minutes ago, but it seemed as though all the fun had tired her out. Now she was dozing off next to Kieli. When Kieli gently pulled the girl against her shoulder, she toppled into Kieli’s lap.

“How did you know that?”

“Mm? What?”

“The song. No normal person in your generation would know it.”

“But, Corporal,” Kieli answered, only half paying attention (the other half of her mind was preoccupied with worry over the right response to this unusual situation—Will Nana get cold? Should I go get a blanket? But wouldn’t my standing up wake her?). “I saw you singing it.”

“You saw…me…?”

“Yeah.” Sometimes Kieli saw the memories or thoughts of the dead. It wasn’t something she could consciously control. It happened automatically when their thoughts were especially strong, or if she stepped into a place where someone’s lingering memories had been bound. “You were in a garden or something, with a girl about Nana’s age. I guess that was your house? And there was a woman inside, too. Oh, was that your —”

Kieli broke off. She’d been rattling off the contents of the dream without really thinking, mostly focused on adjusting Nana’s cape to cover her, but now she abruptly noticed what she was saying. Belatedly dumbstruck, she looked down at the radio.

When she opened her mouth again, this time she chose her words carefully. “Corporal, that was…your wife and daughter, wasn’t it…?”

The radio was absolutely silent. Even the constant faint white noise that always poured from it whether or not it was speaking had broken off.

After a few blank seconds that felt painfully long to Kieli, the voice and static returned. “…Oh. I took an unplanned trip down memory lane, so you ended up seeing it.”

“I’ve never heard you talk about your family before.”

“Well, it’s not something worth going out of my way to bring up.”

“That’s not true at all! I would’ve liked to hear sooner. Why didn’t you ever tell me about them?” she asked eagerly before she could help it. The Corporal had told her all kinds of stories about his past, and yet his family had never come up. It wasn’t as if it had never occurred to Kieli before, but to her he’d always been a radio, so it was just so tough to connect him with a human family in her mind…

“Well, you know. I died in the War.”

All her thoughtless excitement wilted instantly at that.

The Corporal had died in the War. And that had been even before it ended eighty years ago, so most likely his family wasn’t alive either. In other words, talking about his family meant talking about people he’d died without being able to see.

“I’m sorry…,” Kieli murmured miserably.

“No, no, no need for you to apologize,” the radio said lightly, clearly trying to dispel the gloomy mood that had settled around them. Then he abruptly seemed to think of something, and his tone sobered again. “Wait, hold on a second.” Kieli blinked and waited for him to continue. “If you could see me, then that means he could, too, doesn’t it?”

Eep! She immediately saw what he meant. If she’d picked up the Corporal’s thoughts and seen that garden, Harvey must have been able to see the same thing. And she also knew why the Corporal sounded so disgusted as he cursed, “Damn that idiot!”

You just keep playing with them—it must have been Harvey’s version of being considerate, running away and leaving the radio with Nana. Considerate, and guilty. Maybe the whole time he’d been bantering with them and keeping them company in the sand, he’d been wishing for Kieli to hurry up and come switch with him.

“Nana!”

Kieli’s thoughts were suddenly cut off by a woman’s voice. When she lifted her head, she saw a figure in a water-colored costume jogging across the clearing toward them. Hearing her name, Nana stirred on her lap and blinked groggily. As soon as she made out the form running their way, she hopped to her feet. “Mama!”

Kieli gaped blankly at the woman who pulled to a stop, panting, before them. The costume had seemed “watery,” she saw now, because of all the shimmering feathers covering her flouncy blue dress. It definitely wasn’t suited for the cold weather, and she wore a blue shawl on top of it, but it still bared most of her shoulders and chest. It was the same dancers’ costume that Kieli had seen briefly long ago in Easterbury (though apparently that woman was retired). Matching feathered ornaments wound through her short hair. She seemed like an energetic lady in her late twenties.

“Welcome home!”

“Thanks, kid!” Stooping down a little to greet Nana, who had jumped down and flown toward her, she turned a carefree smile on Kieli. “You must be Kieli. It’s really nice to meet you. I just had to tell you ‘thank you,’ so I slipped away a little early.”

“Oh, um, it was nothing,” Kieli mumbled feebly, disoriented. Nana’s mother looked completely different from her mental image. It had only been a totally unfounded image based on hearing Nana talk, but for some reason she’d pictured someone like her old Sunday school teacher.

“They told me you helped my daughter. Thank you so much. I waited for you two last night at the troupe leader’s place so I could say that, but you didn’t come, so I didn’t get the chance.”

Come to think of it, that’s right—the leader wanted us to come see him, but Harvey went straight to the card game instead. I totally forgot. “Actually, I didn’t really do anything. I’m not the one you should thank.”

“I saw him this morning. He’s gruff, but he’s a good boy, isn’t he? I’m jealous. See, my man ran out on me.”

Nana’s mother said this terrible thing offhandedly, with a smile. Kieli didn’t know whether to smile back or not. Plus, the woman had called Harvey a “good boy,” and there was no ready response for that. While Kieli was still casting about for something to say, Nana turned her sunny face up from where she clung to her mother’s skirts and said, “Yeah, Harry’s a good boy. He didn’t laugh at me. And, and, the Corp’ral is a talking radio! Mama, is it okay if we go to the park sometime? I want to introduce them to my friend.”

“…Nana,” a low voice interrupted. Nana’s face during this speech had transformed from her usual sulky expression into a merry smile, but at the sound of her mother’s disapproving voice the smile vanished again.

“I guess not, huh…,” she said, and clammed up again dejectedly.

Watching the girl’s mother, who seemed at the same time sad and frustrated as she looked down at her daughter, Kieli thought she did kind of remind her of that Sunday school teacher after all. Still, it didn’t leave the same bad taste in her mouth. She was sure it must just be the helpless response of a parent.

The woman turned back to her and gave a pained smile. “I’m sorry; it sounds like she’s been telling you weird things.”

Kieli shook her head. “No, not at all.” She meant that perfectly seriously, but she wondered if Nana’s mother thought she was just being polite…

The air between them was definitely getting uncomfortable. Eventually the woman said, “See you later, then,” as though she was trying to gloss over the situation, and picked Nana up. “I’m going to go change clothes. I hope I’ll see you again at dinner. You’re going to stay here another night, aren’t you?”

Kieli couldn’t answer that one, so she just gave a vague smile. They’d ended up staying here last night by going with the flow. Harvey hadn’t told her anything about what they would be doing today. Actually, since he did whatever he pleased and hardly ever really thought anything out in advance, she rarely got to hear about any “future plans” they might have.

There weren’t a lot of families in the troupe, but they did have a separate family-use trailer partitioned into bunks. Nana’s mother carried Nana off to their trailer, skirts fluttering behind her. Nana stared fixedly over her mother’s shoulder at Kieli as they left her behind. She was back to looking like a cranky child, but she still gave a small wave.

Somehow Kieli got the feeling that even if they were going to stay here tonight, she wouldn’t be getting another chance to play with Nana today.

“…There’s no help for it. It’s best not to get involved with weird stuff. That’s the average person’s happiness,” said a voice from behind her in an attempt at comfort. Kieli giggled a little. The “mysterious talking radio” who owned that voice qualified as “weird stuff” himself. She lightly stepped back up into the trailer. The small radio sitting on the edge of the threshold looked so old that if they let their guard down it was liable to get put out with the trash any second, but he was their precious companion.

“I’m happy right now, you know.”

The Corporal gave a little laugh. “Thanks.” Still, even his laugh sounded kind of lonely. Maybe he wished he could have stayed with Nana longer.

The sky above the square roof of the trailer was starting to melt from the coppery color of evening into the blue-gray of night. Not long afterward, the other troupe members returned from work, too, turning the quiet camp rowdy, but the young man with hair the color of the evening sky never came back.

Gzzznnn…gnnnnn…

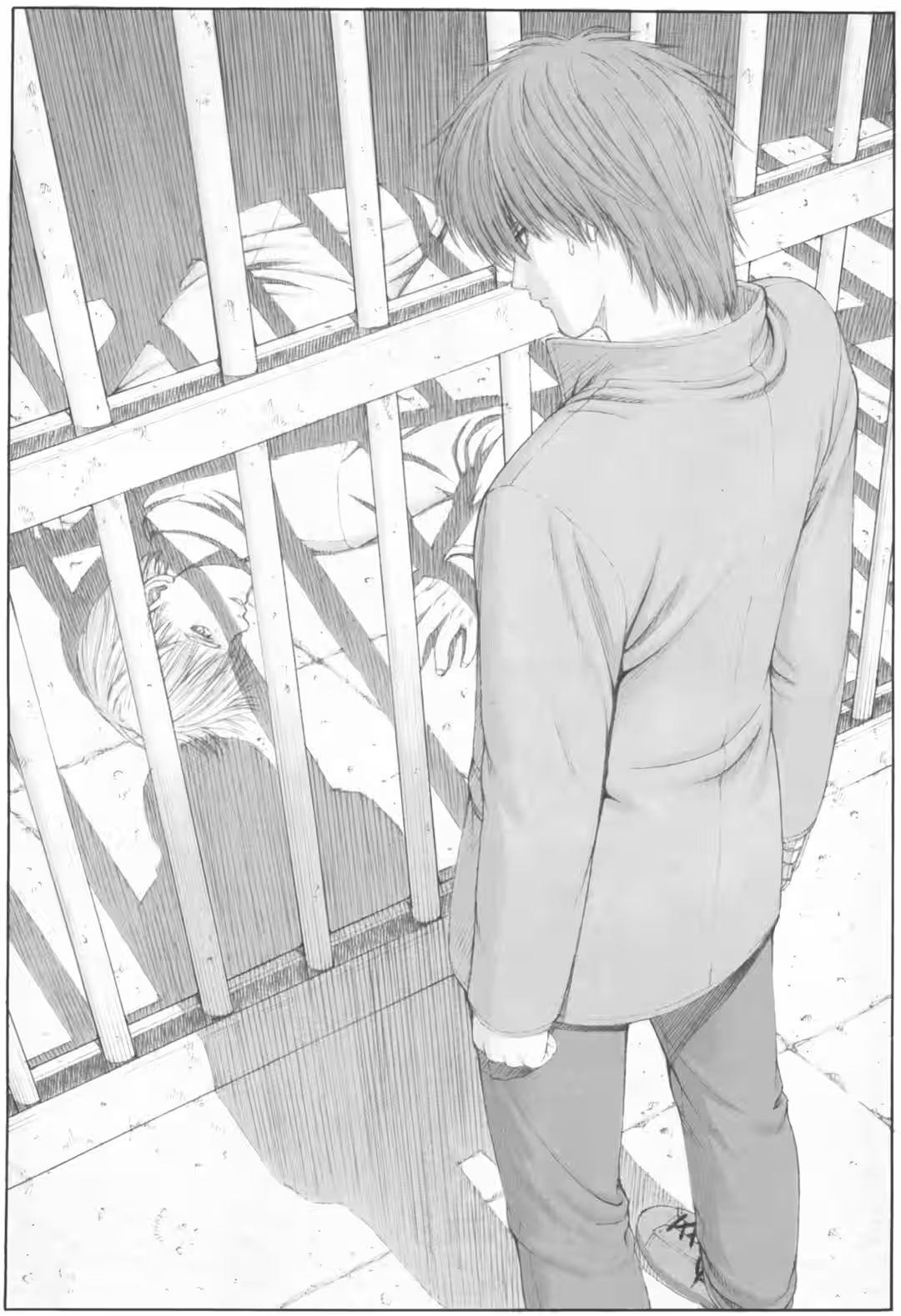

When he touched the nothingness in front of him with his left hand, he heard a low sound that reminded him of a machine gauge going past the red zone, and the air radiated outward from the palm of his hand like ripples in a pool of water. Everything in his body gave a horrible shudder. He withdrew his hand right away.

Harvey gave a thin sigh and pulled himself back together. Looking down at his palm, he uttered a faintly impressed noise.

He’d crossed over the bridge spanning the railroad tracks and come to a halt just before the downward stairs on the south side; now he was standing still. Every so often, a breeze blew over the pitch-dark tracks below his feet and made the fences on either side screech like plaintive animals.

He’d gone to visit the informant the tobacconist on the parish border had sent him to, but as his business had been quickly concluded, he’d decided to take a brief spin around town before heading home. (There was no way he could actually do a thorough walk around such a big city in one day, so he’d taken the bus a ways then walked back, and even that had pretty much taken all day.) On his way back to the camp, it had occurred to him to make one final pit stop here. That was how he had stumbled across this entertaining phenomenon.

He reached out to touch the nothingness again, then decided against it. If it were someone else’s problem that would be one thing, but this could do serious damage to him, which wasn’t entertaining at all. He’d been attacked by a similar sensation once before. This was the same feeling of extreme instability he had experienced when he was shot in the heart with that gunlike thing made out of fossil ore or whatever.

Here was a strange magnetic field just like that on the south side of the tracks.

Is there something there…?

When he squinted into the darkness spreading out before the bridge, he could just barely make out the shapes of the crowded skyline. High walls twisting and turning like a three-dimensional maze and homes almost too tiny for people to inhabit. It wasn’t that late at night, and yet the area was shrouded in patently unnatural darkness and silence. There was no sign of anyone living here.

So that’s it. The theme park supposedly built several years back: “The Whimsical City.” Central City, the hub of Westerbury, was divided into the north and south districts by a continental railroad piercing straight through its urban center. These days, only the north half of it was a functioning city. The northern side was actually plenty big by itself, since the two parts had originally been separate metropolises that were united during the War era. On the other side of the tracks was the old city, which was now in ruins and had been closed down for a long time.

South Westerbury Park had been constructed right on top of those ruins. A man who had made a fortune in the commercial district had bought the ruins off the city and built a gigantic toy town. (Harvey thought they were living in poor times compared to the high-level civilization before the War, but apparently there were people in every era willing to pour money into strange diversions.)

At the bottom of the steps on the south side of the bridge was the arched front gate, which was currently barred. The first of many puppet figures to greet parkgoers stood motionless on either side: twin dark-gray suits of armor wielding great swords. Once you were past that gate, you entered the park, the city of puppets—he personally had no interest whatsoever, but anyway it seemed to involve some sort of adventure ride where you drove in a truck through a dream world of mechanical dolls and eventually ended up at the clock tower in the center.

Looking down from the bridge, Harvey could make out a dark tower rising up from a hill at the heart of the park town. The giant clock face at its peak was the only pale point of light in the darkness. The hour and minute hands cast their shadows on it.

The only things moving were the hands of the clock tracking the sluggish flow of time and the fences as they swayed in the wind.

The park had long since closed for the night. Harvey didn’t sense any real human presence nearby. Even the street performers he assumed had been greeting visitors in front of the gate or on the bridge and livening up the attractions had packed up and gone home by now. Other than the occasional rattle of a fence, the whole area was blanketed in silence.

But for some reason something felt vaguely off. Maybe it was because the air still held faint echoes of the day’s commotion and the scent of the crowd…?

Or maybe it’s a doll’s presence I’m sensing.

Even Harvey was disgusted at himself for the childishness of this sudden thought.

He cocked his head and gazed at the empty nothingness one more time, that space that formed some kind of barrier even though there was nothing there. Then he decided to ignore it for the time being. He had enough on his plate already. There was Beatrix, of course…and the Corporal.

Great. I just had to go and remember that now, didn’t I? He’d been forcing his thoughts not to go there all day long, but now it was back depressing him again.

He dropped his gaze to his lowered hand and balled it into a fist. He knew the Corporal must have been remembering it without any conscious thought. But that scene had been kind of harsh on Harvey. In war, people killed their enemies; that was just what happened, and he knew it was nothing but hypocrisy to feel like this now—but it still felt like a slap in the face: you destroyed this happy family with your own hands.

Harvey knew he would be chewed out again if he didn’t get back to camp soon, but he couldn’t keep his feet from dragging. Actually, he had already been getting chewed out before he left. He figured he was bound to get yelled at today whether he was late or not. He sighed internally.

Tick, tock, tick…

For just a split second, the wind blowing across the bridge carried with it a snatch of a song, so faint it was barely audible. He lifted his eye and concentrated intently on the darkness in front of him. He didn’t hear any suspicious sounds. Just the feeble whine of the rusty fence underneath his feet. Was that just my imagination…?

“You could’ve just come before closing time,” said a voice suddenly from behind him, and his attention was yanked back in the opposite direction. Harvey automatically tensed for an attack, but he quickly realized that the voice was one he recognized and relaxed as he turned around.

Right around the halfway point of the long bridge stood a lone gas streetlamp. It was modeled on an old-fashioned lamp, one of those triangular ones, and it had a miniature human figure hanging off the tip. Maybe it was supposed to fit in with the park’s theme.

Beneath the streetlamp stood an odd figure: stocky and short-legged, with strangely oversized hands and feet. At those feet lay the severed head of a giant yellow and brown patchwork bunny, smirking at him (though he assumed that was a trick of the shadows).

“Shiman…” Harvey murmured. Then he fell silent, standing there stock-still and unable to think of what to do next. Eventually the other man walked toward him with soft, unhurried steps. The bunny head was left behind under the streetlight. It was definitely smirking.

“Be nice and bring your girl here. Don’t come all by yourself after it’s closed for the night. I swear, you’re such an oaf.”

“‘Girl’?” Harvey thought for a moment. “Oh…Hey, this is your fault in the first place for making us babysit.” Okay, sure, so it hadn’t even occurred to him to bring Kieli here. That wouldn’t stop him from criticizing Shiman right back. Shiman just let it pass, innocently huddling his shoulders to light a cigarette. This was a man about to cross the line into old age, a man with a certain dignity, holding his favorite silver lighter in the paw of an animal costume wearing striped overalls.

He’d waited a little too long to laugh, so in the end he just heaved a tired sigh. “What’s a man your age doing in that getup?”

“I got no choice. The kids love this stuff,” the other man grumbled, but Harvey suspected that he was really enjoying himself. The leader of the troupe didn’t have to put on a costume and personally solicit visitors.

Last night Kieli had breathlessly asked him if “that bunny person” was really the troupe leader. The question had surprised him, but according to Kieli, he’d been so terrible at the balancing act that she just couldn’t believe it. When he’d told her that before becoming leader Shiman had been a professional acrobat, her eyes had gone wide as saucers.

“You’re too old for this. Quit putting on costumes and balancing on balls,” Harvey said half jokingly (and half with serious worry). Shiman guffawed and scratched his head with his costumed paw.

“Aw, man, and here I thought I was keeping up with the young folks. I guess my old body just can’t do what I want it to anymore.”

“It’s not something to laugh about. You’re going to really hurt yourself one of these days.”

“You’re a fine one to talk! You’re an injured man with no self-awareness. I’ve hardly ever seen you in one piece, for crying out loud.”

“…Shut up. Don’t change the subject to me,” Harvey snapped in open irritation. By some strange coincidence, his old friend had echoed the same thing the radio had said earlier in the day, and he couldn’t help feeling rebellious. But then he immediately regretted taking it out on Shiman. It wasn’t as if it was Shiman’s fault. “Crap, I’m sorry.” Even that came out more sharply than he’d meant it to, though. Apparently he really was in a bad mood. When he sighed, fed up with himself for being such a brat, one giant cloth paw abruptly reached out and towed his head in while another violently ruffled his hair. “Gah! What the hell?!” he bleated, shoving the other man off.

“Wanna go out drinking?”

“Nah. I don’t drink.”

“Shut up and come on. You can sit next to me and eat peanuts or something. It’s no fun drinking by myself.” Shiman whirled around and started walking off toward the lights of the newer part of town as if Harvey had agreed with him, which he hadn’t (and if his other choice was eating peanuts, he might as well just drink).

“Wait, are you going to wear that to the bar?”

“Something wrong with that?”

“I don’t wanna be seen with you.”

“Don’t worry about it. It doesn’t bother me,” declared the bunny man calmly, striding off on his puffy feet. Harvey stared dumbly after him.

“God, he thinks he can just order me around…” He lightly shook out his tousled hair, gave up, and followed him. Maybe it was perfect timing. He hadn’t really wanted to go back anyway.

In contrast to the eerie darkness and silence of the phony town lying on the south side of the tracks, the view of the new city from the bridge twinkled with the lights of the windows, the streetlights, and screens on the walls of buildings—all the lights that made up a city inhabited by human beings.

As he caught up to the costumed man facing away from him and picking up his bunny head beneath the gas streetlamp, Harvey whispered one last “Sorry.” Lately I’ve been doing nothing but apologize.

“Huh? What for?”

“…Nothing.”

Harvey guessed it was just about exactly two years ago during Colonization Days that they’d met at that carnival in Easterbury. He’d made a unilateral decision back then never to see Shiman again (and the truth was, he hadn’t come when he was called last night on purpose), yet now here he was imposing on the man again and being worried about just like he always, always had been. And according to the troupe, Augusta—who had retired and settled down—was looking forward to Harvey coming to see her baby. He’d only promised he would to get her off his back…

Why was it that, even though he tried to avoid getting involved with anyone, he was always being rescued by someone?

Wanna play with me?

It was almost Colonization Days. Mama and the stupid mouse and all the other adults seemed busy getting ready for their jobs. And then while Nana was playing “jump on the shadow” all by herself at the park entrance, a cute girl around her own age called out to her from inside the park.