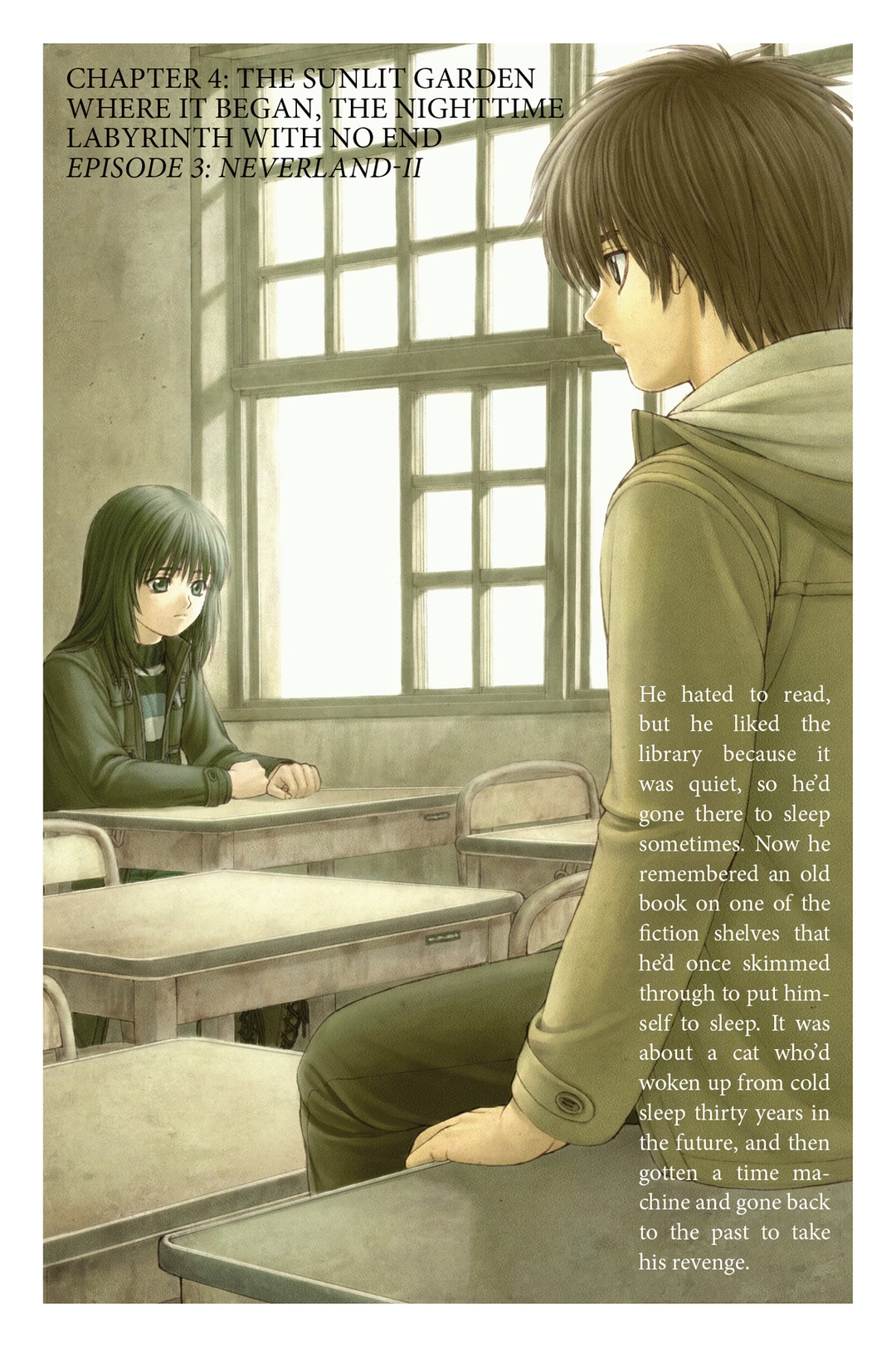

Episode 3: Neverland-II

We got word that your mother’s just passed away.

Wondering to himself whether he would have wanted to go home if he’d had any memories of his parents when he came back to life, Harvey suddenly remembered hearing someone tell him that.

He’d found himself thinking about the past a lot these last few days. Maybe it was Christoph’s influence. Defining “rebirth” just as the true first time—in other words, the time when he’d first become an Undying—he’d been sure he had almost no memories from before his rebirth. (He’d actually died and come back to life several more times after that, not that it was his favorite thing to think about, and he hadn’t lost any memories those times. He figured having your core taken out must be more like being in suspended animation.) And yet, when he finally buckled down after all these years and probed his mind for anything he might remember from before his death, he sometimes surprised himself by abruptly discovering new things—just fragments, tiny bits and pieces—buried down there near the bottom of his memories. It was like finding an old book that had been gathering dust in the basement for decades and then opening it, only to see all the pages fall out of its disintegrated binding and spill onto the floor every which way, so that he couldn’t tell what order they should go in anymore.

Still, he couldn’t find a single direct memory of his parents in the “pages” he’d gathered. But if he remembered someone telling him she’d “passed away,” that must mean that if nothing else, by the time he died his mother was already gone. In other words, going home had never been an option in the first place. He felt a little deflated.

He didn’t know exactly how old he’d been when he’d heard the news, but he got the impression he’d heard it at school, as a kid (even the fact that he’d gone to school was a revelation, although now that he thought about it, it was only logical). From what he could guess of the circumstances, his mother must have been hospitalized or something.

We got word that your mother’s just passed away.

The person saying it had been his homeroom teacher or someone, in a voice filled with sympathy. He didn’t remember what his reaction had been. Or rather, he got the feeling that maybe he hadn’t shown any particular reaction.

Anyway, that piece of his memory was fuzzy, and he couldn’t call up a mental picture of the conversation. There was just one scene that his memory did have full visuals for, though: himself, probably that same day, standing on the landing of the stairwell and silently crying. It was an oddly clear little picture, though faded. He’d gone through the whole day just like always, and then long after school let out, when the building was empty, he’d cried all by himself.

…Apparently that was the kind of kid he’d been. I could laugh; that sounds so much like “me.”

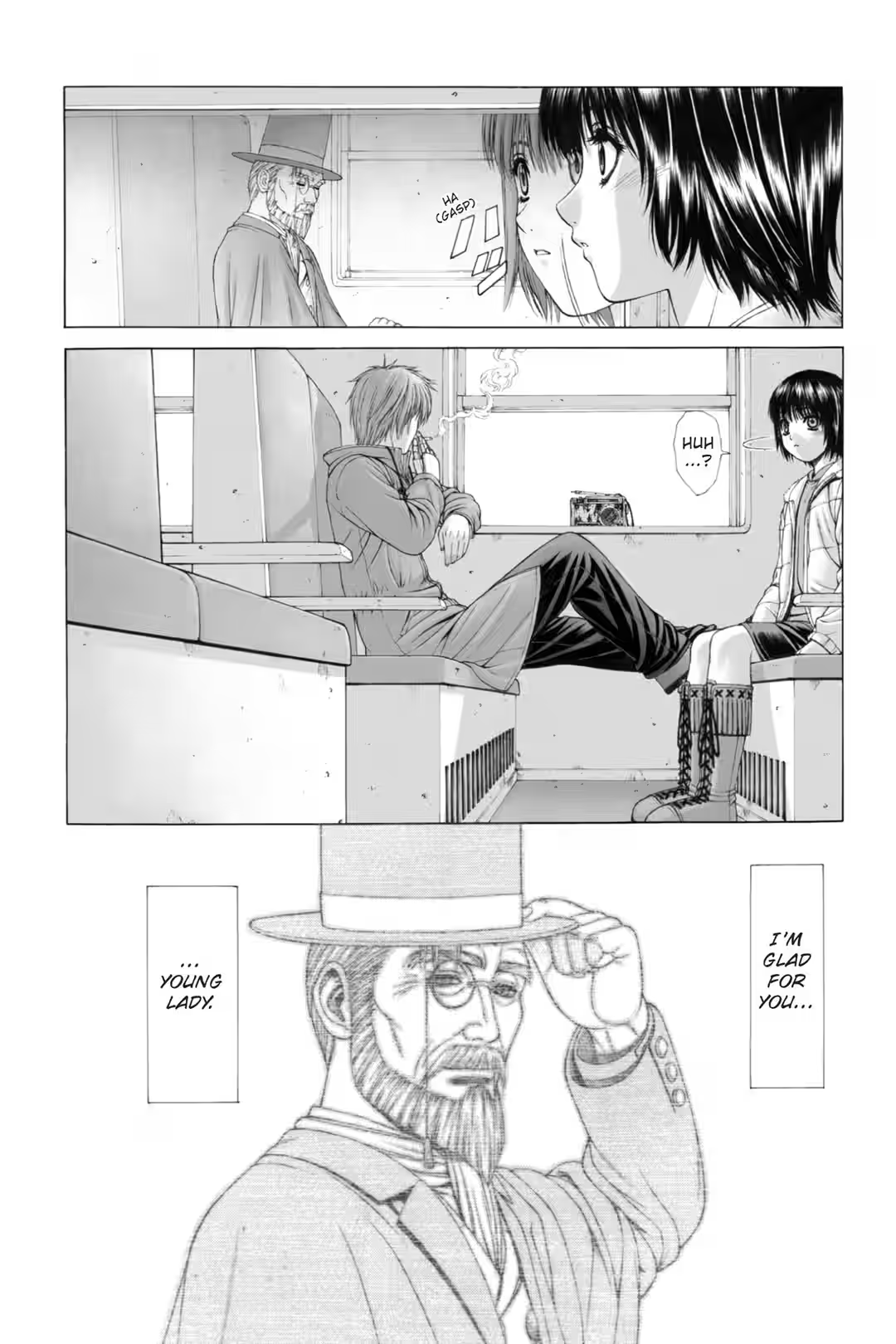

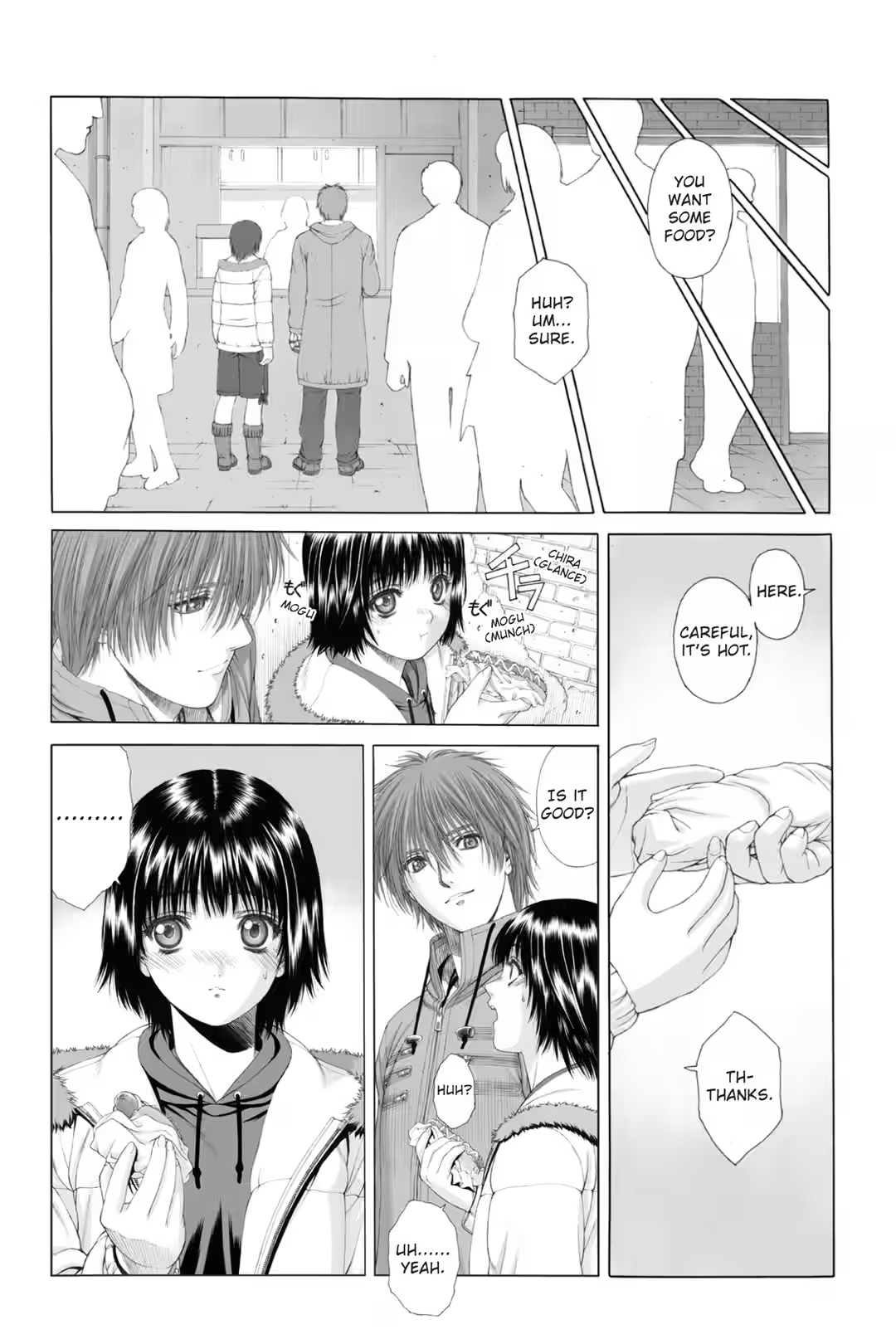

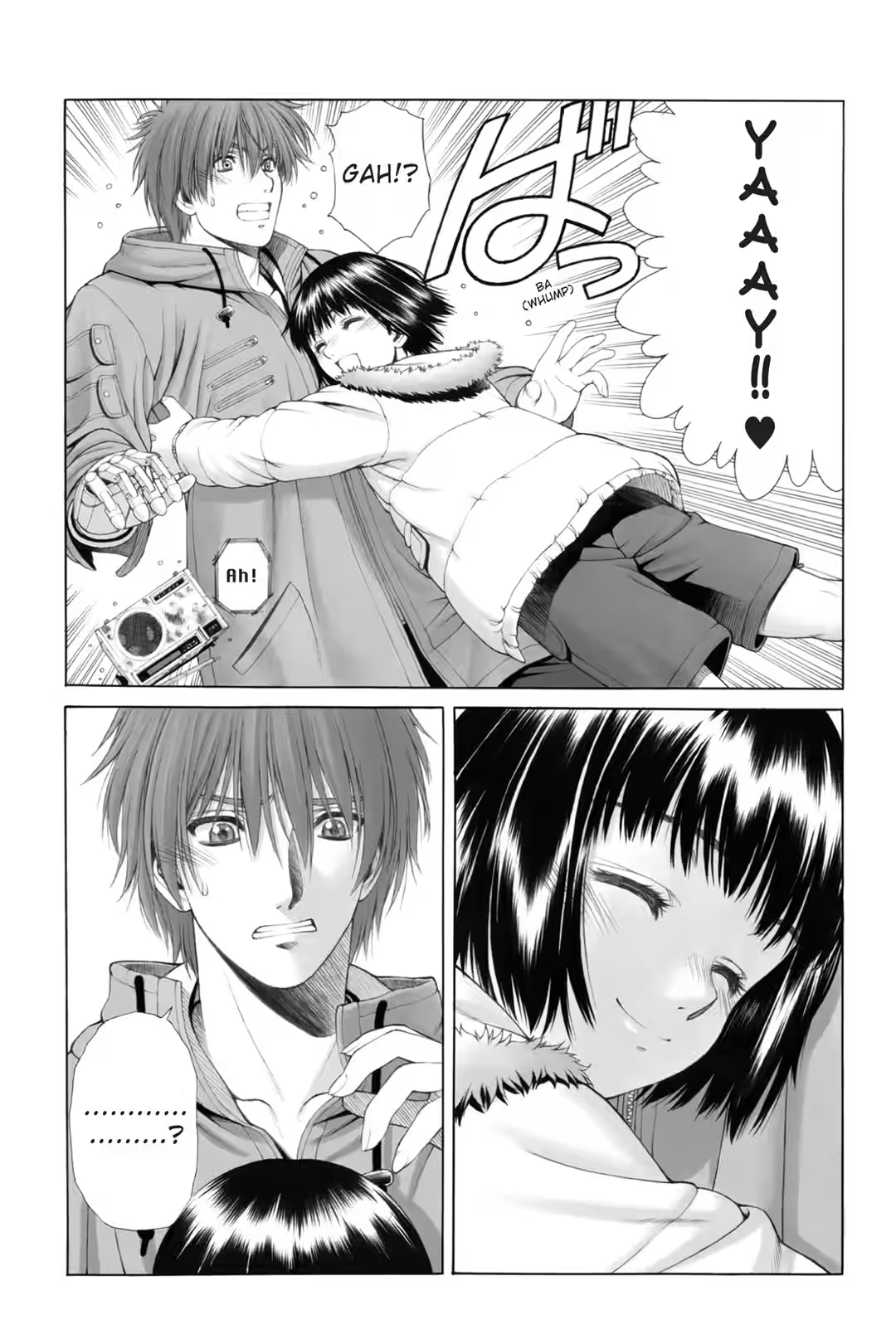

It was the eighth night of the Colonization Days holiday. There were only two more left. We should leave Westerbury the day after tomorrow, he thought, walking back into Shiman’s camp to find Nana standing under the light. She ran up to him as soon as she caught sight of him.

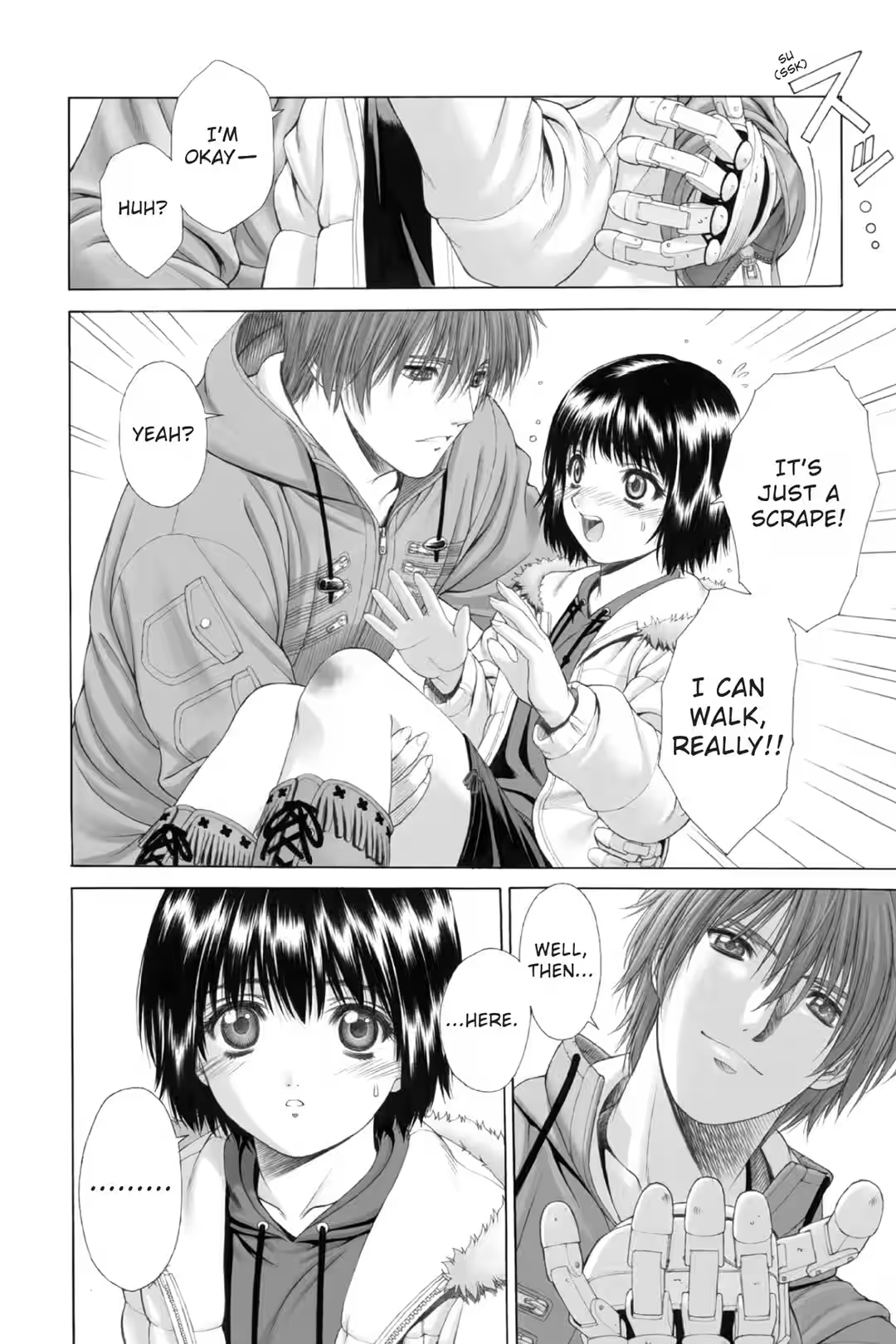

“Harry, welcome ba—”

But before she could finish, she tripped and fell flat on her face, squashing the radio around her neck, which cried, “Ow!” (as if it could possibly hurt!).

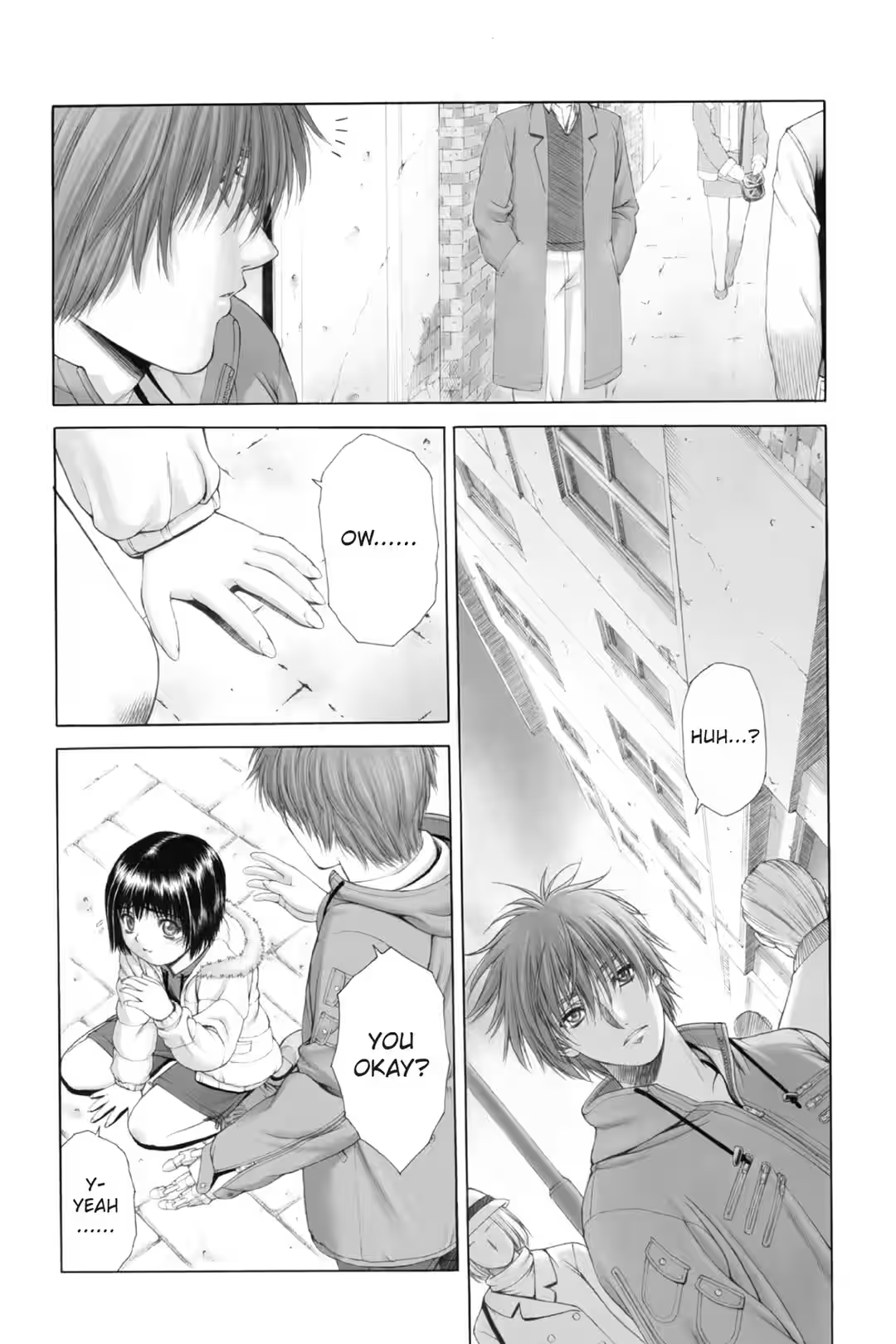

Fortunately, Nana bounced right back to her feet, so Harvey thought she must be fine—until he saw the blood oozing steadily out of some pretty amazing scrapes on both of her knees. He sighed and started walking toward her. Nana was standing in place, looking down at her legs with no reaction whatsoever; but as soon as he picked her up, her arms came up to cling around his neck and she started bawling, as if it had only now occurred to her.

“Talk about delayed reaction.” It kind of made him wonder if kids calculated the timing of their crying. Turning his face slightly away from the voice wailing right into his ear, he dropped his gaze to the radio squashed between them. “Where’s Kieli?” He got a burst of peeved static instead of a verbal answer. Apparently the Corporal had been ditched again today.

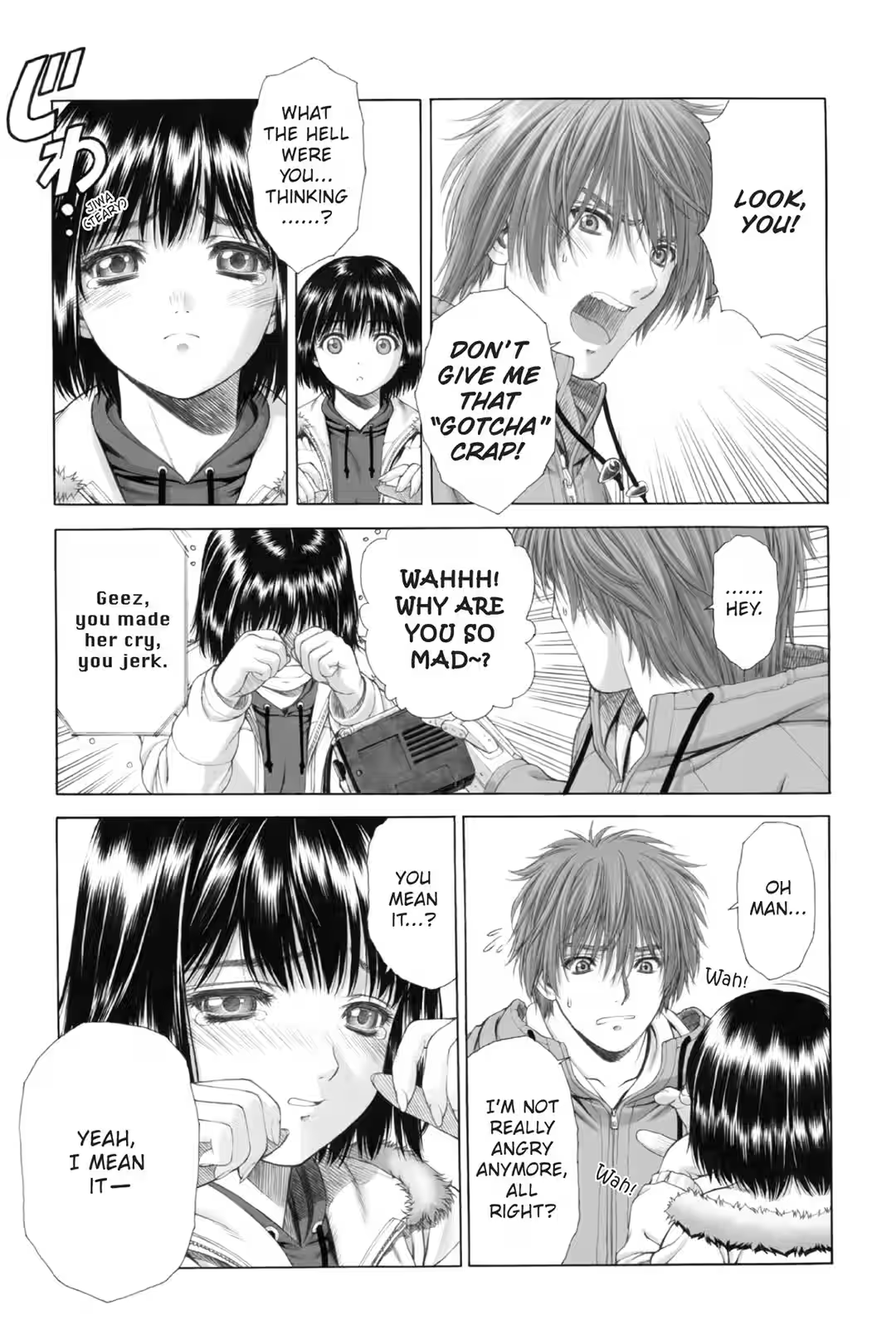

“Nana, what happened?”

Harvey looked up to see Nana’s mother running up to them from the trailers—she must have heard the crying—so he abandoned his conversation with the radio. “She tripped and fell.”

“Oh dear. I feel bad that you’re always having to help, but thank you.” As he relinquished the fussy child and lifted the radio off of her neck, he tried asking her mother instead.

“Isn’t Kieli here?”

“Oh, no, she’s not. I saw her leaving as I got back this evening.”

Harvey sighed. “Thanks…”

What is that girl doing…? He was about to walk away when a voice piped up, “She went to go see her man!”

Harvey turned to see five or six members of the troupe just making their way past him after cleaning away their card game. “I hear that passerby that helped her out the other day is pretty good-looking. You treat her so cold, she probably left you for him, huh?” teased Rat, wearing his usual grin. Behind him, Bearfoot paled and whispered, “Cut it out! I’m telling you, he’s scary…”

Before Harvey could say anything, a voice from the radio suddenly shouted, “What are you, stupid?! She would never—” He hid the Corporal behind his back and kicked him to shut him up, silently fuming, What’s gotten into you? You can’t talk in front of them! By the time he’d taken care of that, he’d forgotten what he’d intended to say to them, so his answer ended up just being “Huh.”

“‘Huh’?” Rat echoed. “That’s it?” He seemed disappointed.

“It’s not something for me to butt into,” Harvey spat, wishing they’d just give it a rest already. He was already stalking away by the time he’d finished the sentence.

He stopped to take a drink at the watering place out back and stuck his head under the faucet to wash his face while he was at it. He’d wanted to be alone, so it was a stroke of luck that nobody else was around—but since the radio took advantage of their solitude to launch a stream of complaints at him, it was hard to decide whether it was good luck or bad luck.

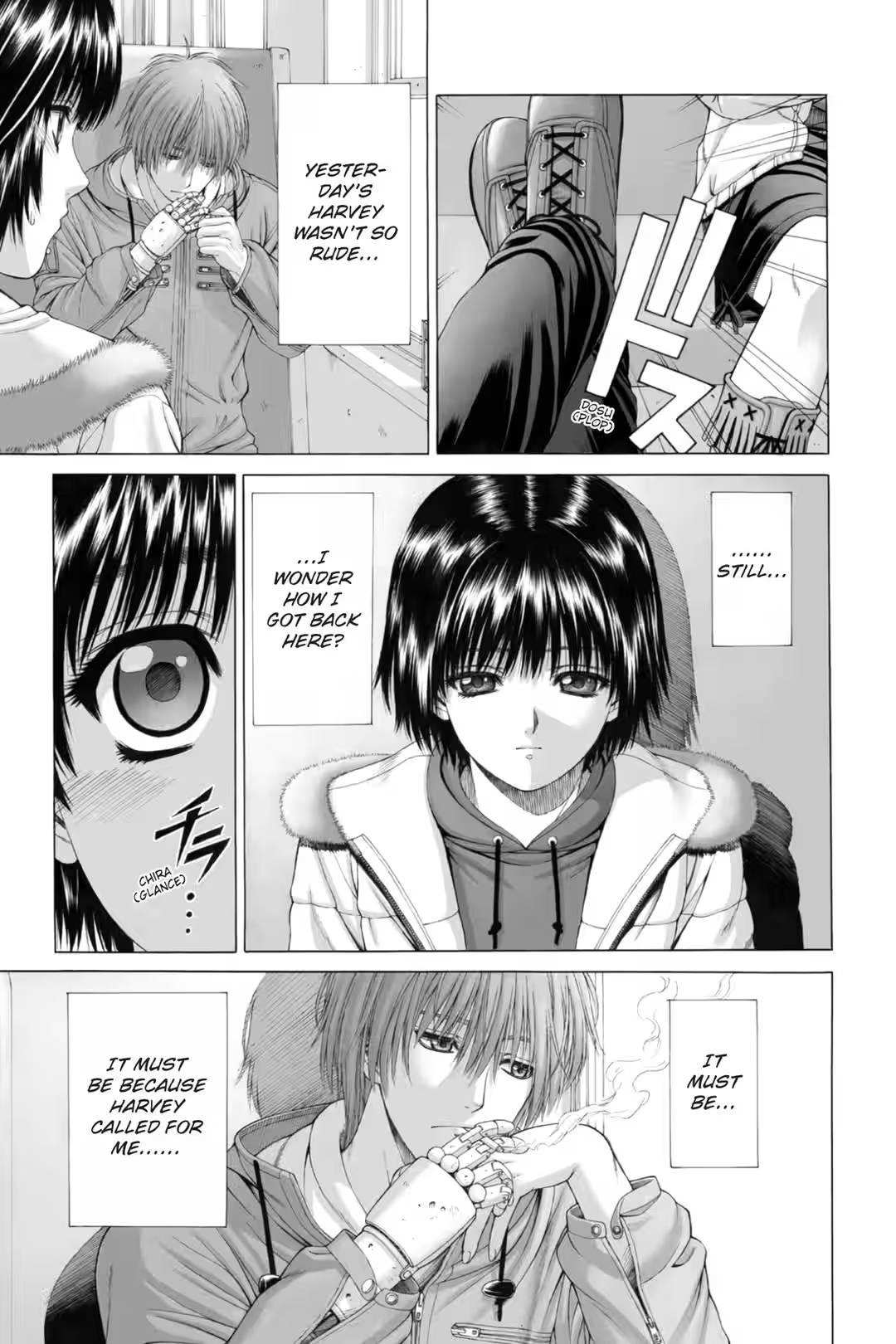

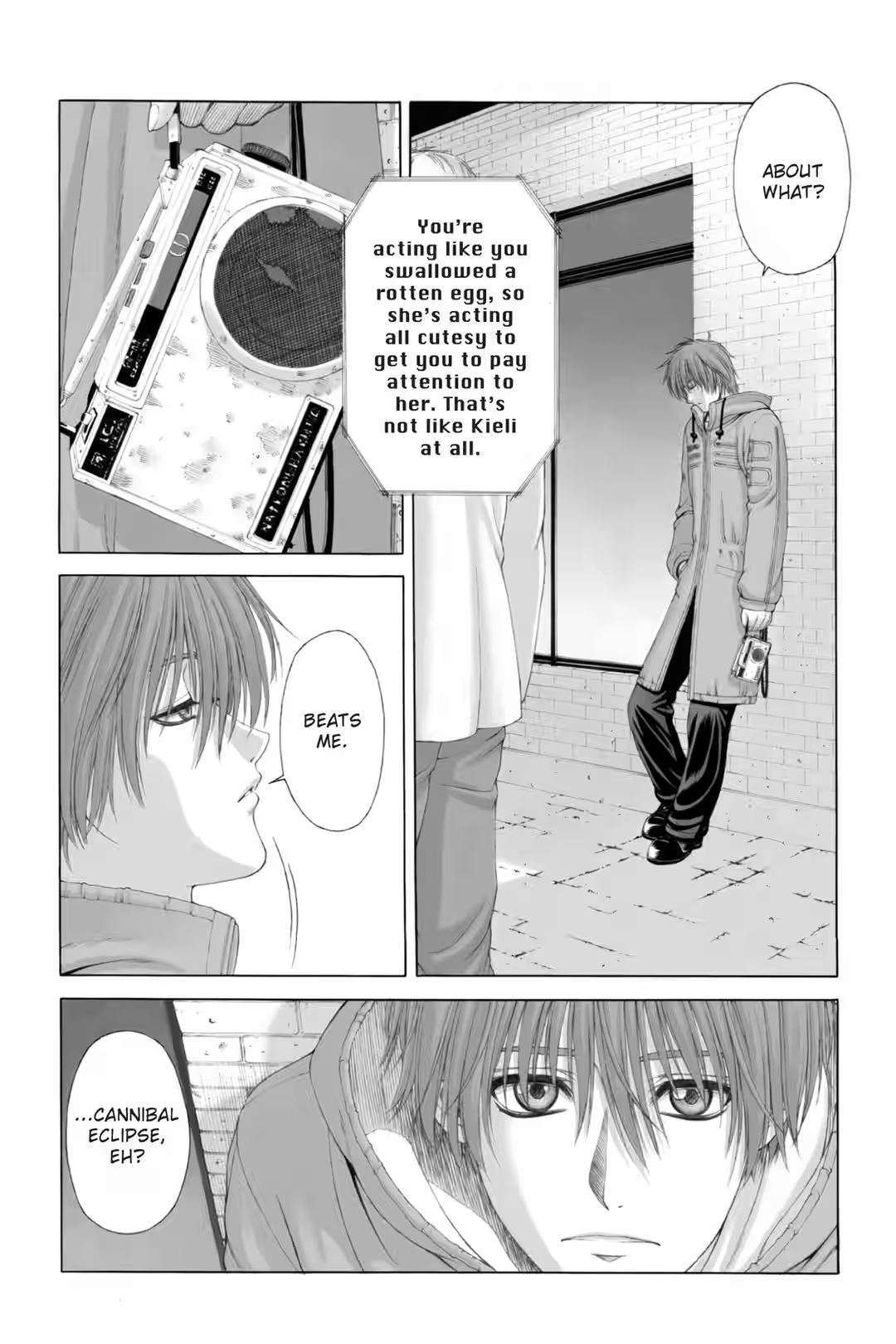

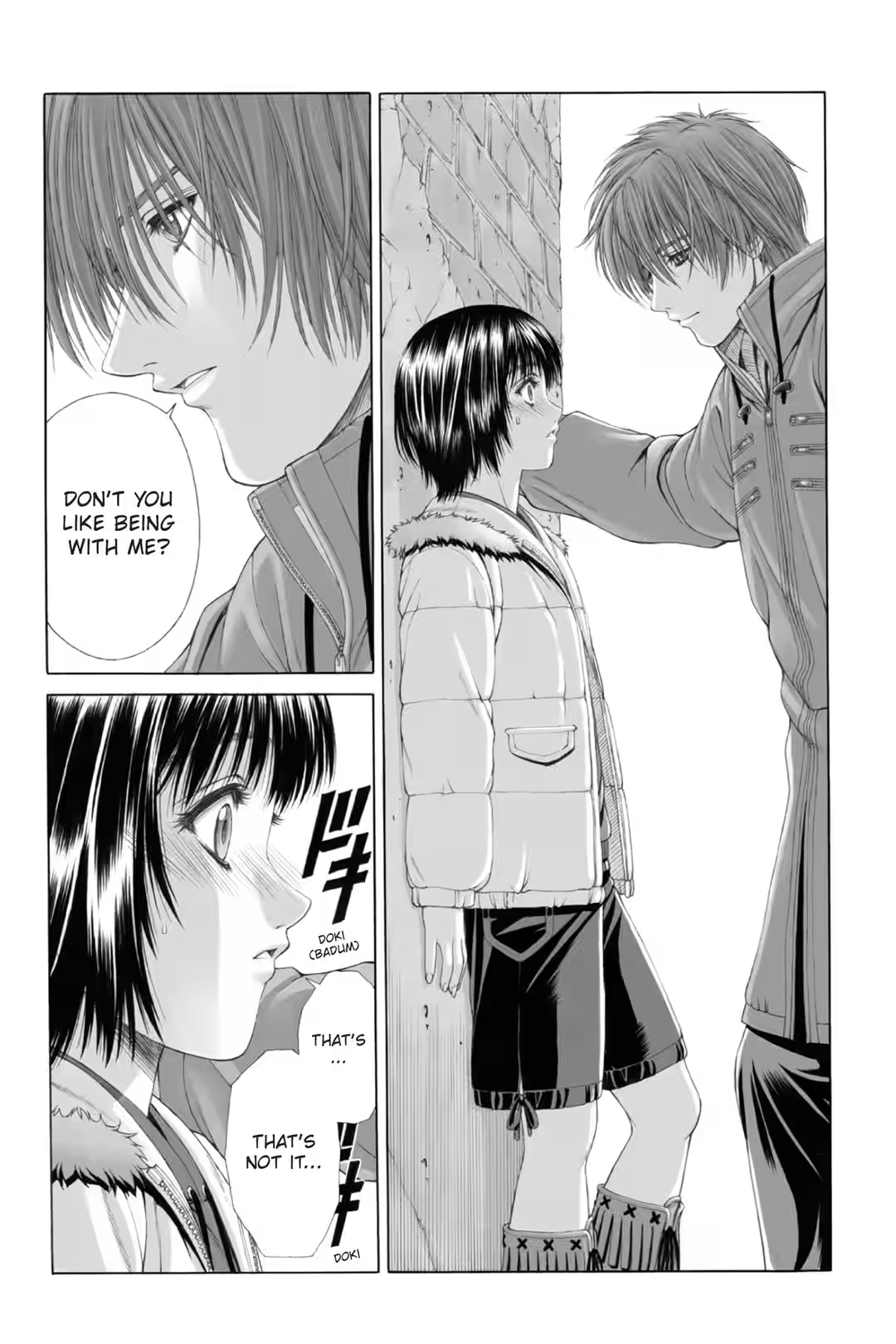

“The whole reason Kieli’s been acting weird lately is because YOU won’t take a line and stick to it, you know! Take some responsibility and try harder to find out where she’s going and what she’s doing!”

“Oh, not you too, Corporal…” Could he actually be taking what Rat said seriously? “She doesn’t want to tell me when I ask her, so what do you want me to do? Just let her do what she wants. It’s on her own head.”

“Do you actually mean that?”

“I told her to tell me if something happens. I’m not going to nag her anymore about it until she says something. She’s not a little kid anymore, so I guess she’ll take responsibility for her own actions.”

The radio gave a snort. “Yeah, you can try to sound wise all you want, but the truth is that you’re just afraid to get insistent with her, in case she calls you out for being a hypocrite.”

Harvey couldn’t think of any immediate reply to that. He froze there with the back of his head under the still-running faucet for a while before he finally reached up to turn it off, wrenching the knob more violently than strictly necessary. “…Shut up.” When he raised his head, he found himself more or less facing off against the radio, which was dangling off the pipe in front of him at eye level. Grimacing at the water that dripped down from his bangs, he shot the Corporal a hooded glare.

“Don’t blame it all on me. This isn’t about me—you’re feeling jealous because she keeps leaving you behind, aren’t you?”

He’d just said the first thing that came into his head, but apparently he’d been right, because after a short bark of static, the radio was the one to fall silent this time.

They glared sourly at each other, eye to center-of-speaker, before Harvey looked away with a sigh. It wasn’t as though the Corporal had been any less right about him, after all. It was true that the reason he hated interfering with people was that he didn’t want to be interfered with—and considering the way Kieli’d spoken to him last night, she’d definitely noticed that he wasn’t healing as fast as he should. He’d been a little unsettled by that, so when Bearfoot had shown up, he’d seized on the chance to end the conversation without ever asking where she was going.

He’d never thought he’d be able to hide it from her for long, but still, it had come out faster than he’d expected. Had he handed her direct proof, somehow? Harvey mentally tallied up his mistakes. Apart from getting called out on the cut he’d given himself bumping into that sign, he couldn’t think of anything in the last few days…

Oh, whatever.

Suddenly it was just too much of a pain to worry about it. He couldn’t change anything anyway.

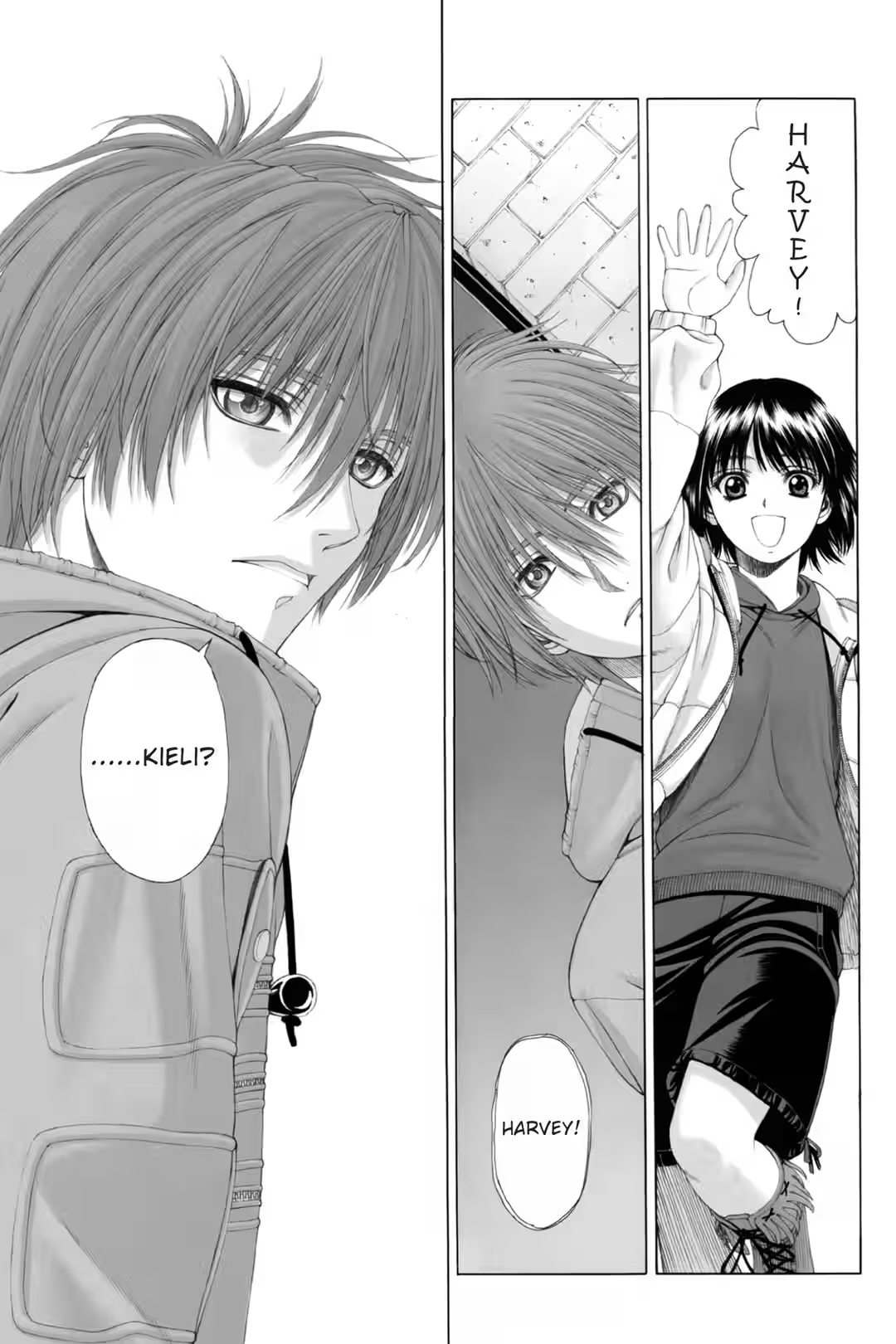

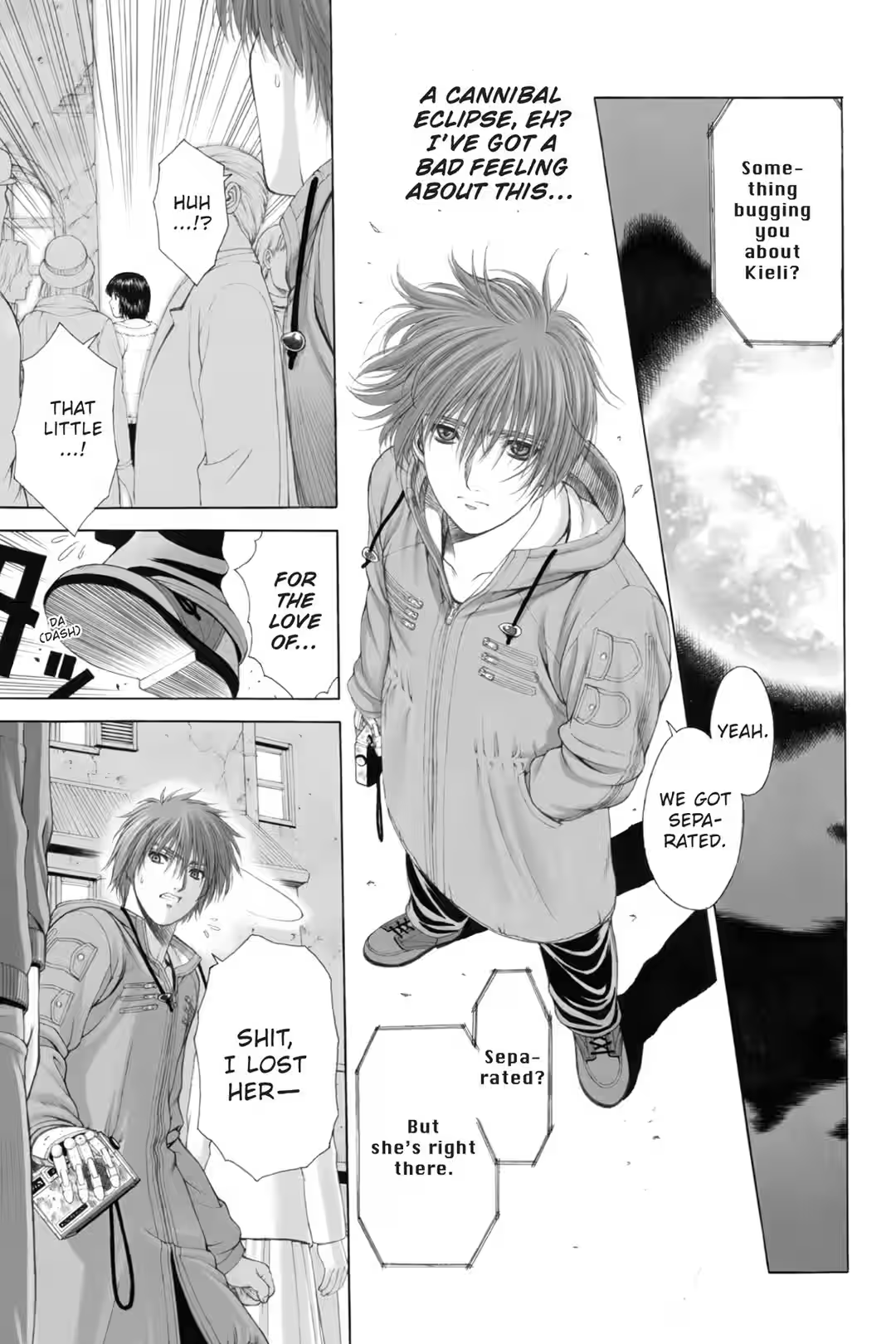

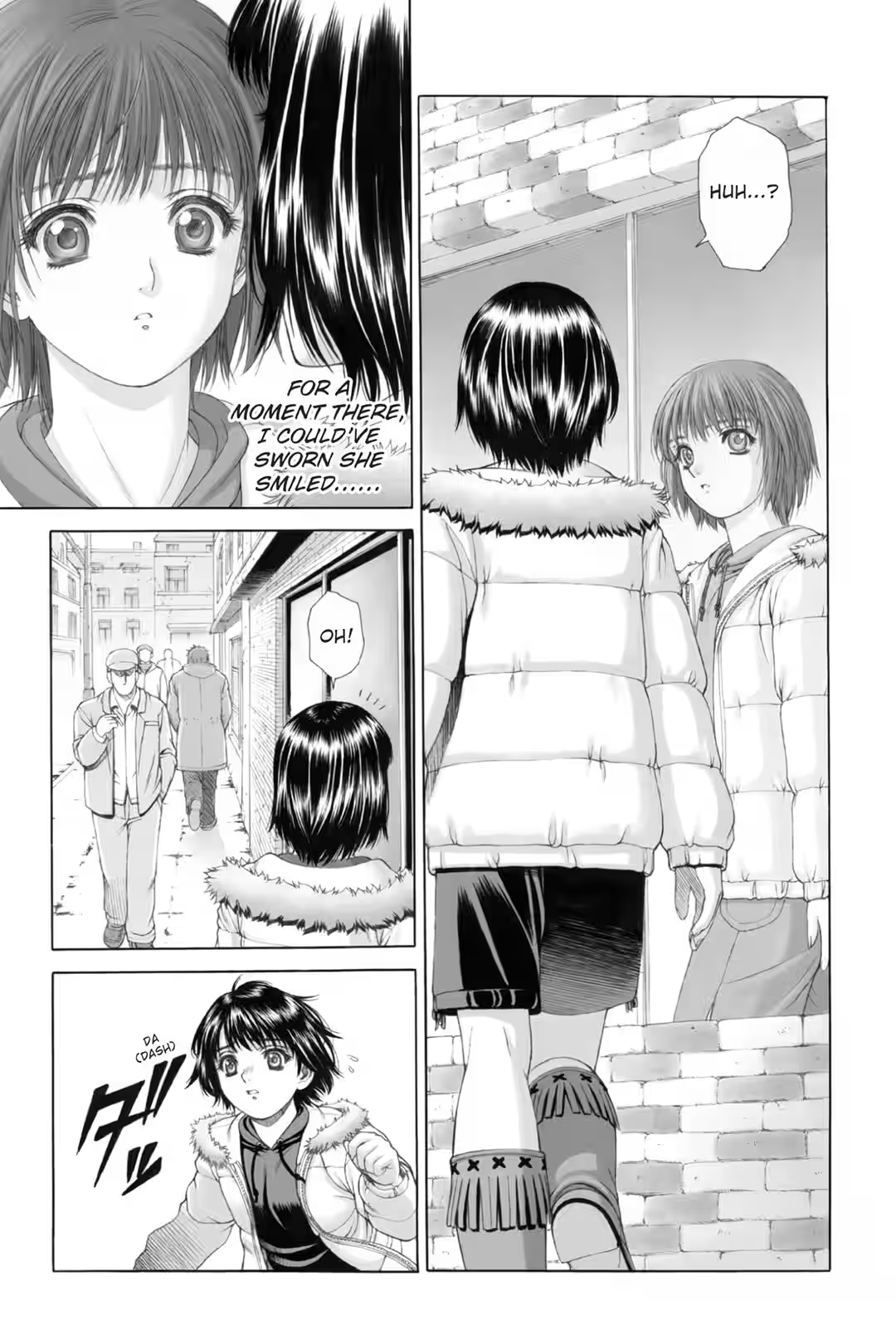

Giving his face and hair a perfunctory wipe-down with the hood of his parka, he shoved aside all the confusion and forced his mind to go blank. When he looked up at the sound of running footsteps, a familiar face was just rounding the corner of the trailer.

“Mr. Harvey!”

“…You again?” And what’s with the “Mr.” all of a sudden? He glared out of the corner of his eye, and Bearfoot paled, losing all his momentum and cringing nervously. (Harvey didn’t think he’d particularly threatened the guy, but apparently Bearfoot was scared of him now for some reason.)

In no time, though, he recovered enough to burst out, “The leader says to come right away!”

“What for?”

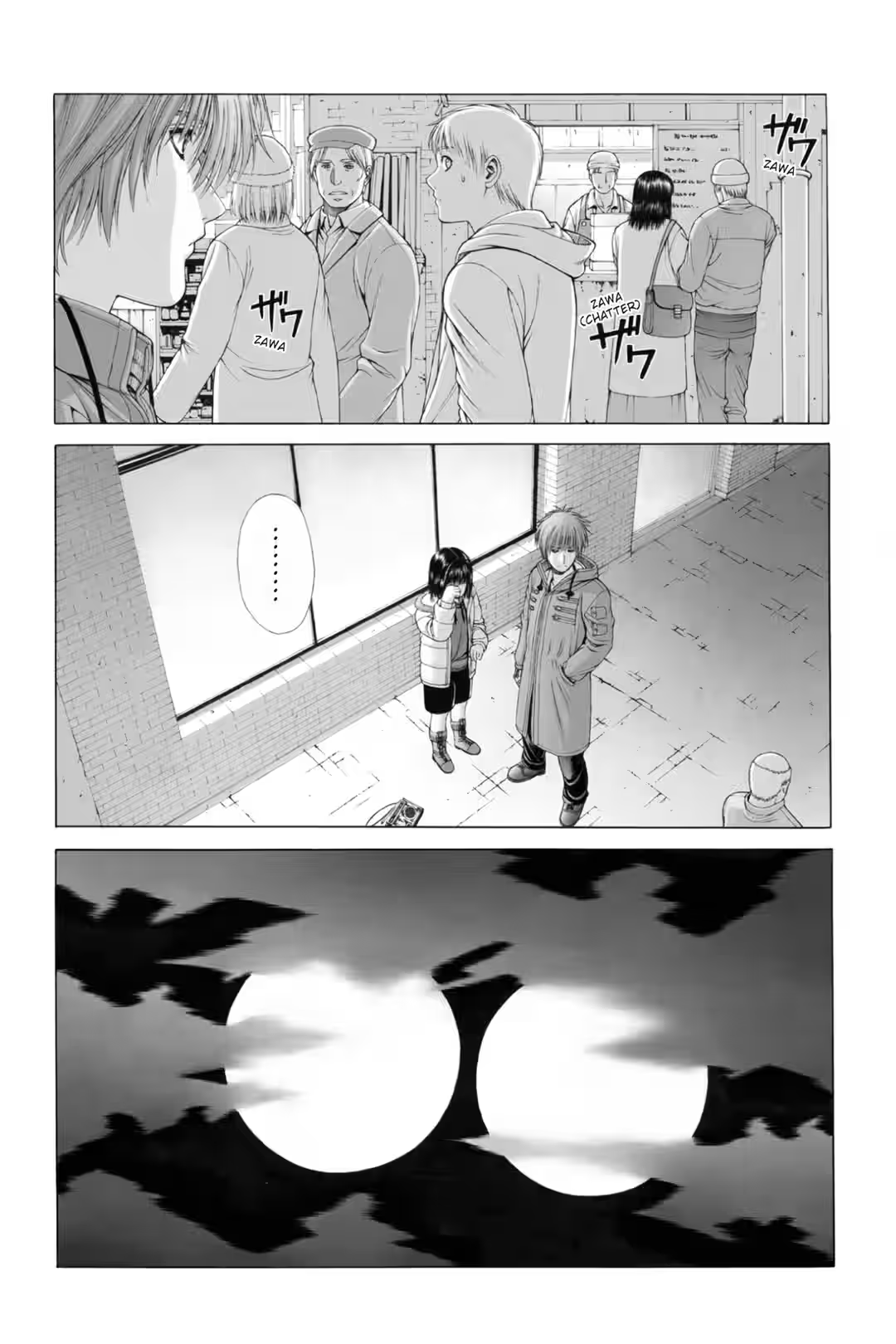

“Just come on!” he cried, practically stamping his feet. Harvey traded an uneasy look with the radio as he unhooked it from the water pipe. Bearfoot, meanwhile, had already taken off running, seeming too impatient to wait even for that. He was trotting back along the trailer wall, and after a beat, Harvey followed. When he turned the corner, he saw a thin crowd of performers gathering in the clearing.

Harvey squinted into the darkness beyond the clearing and came to an automatic and immediate halt. Parked there with its headlights still on was a single light truck, its body painted a shade of black that melted into the night around them. Around the back stood two or three figures in white clerical robes.

Church Soldiers…What are they doing here?

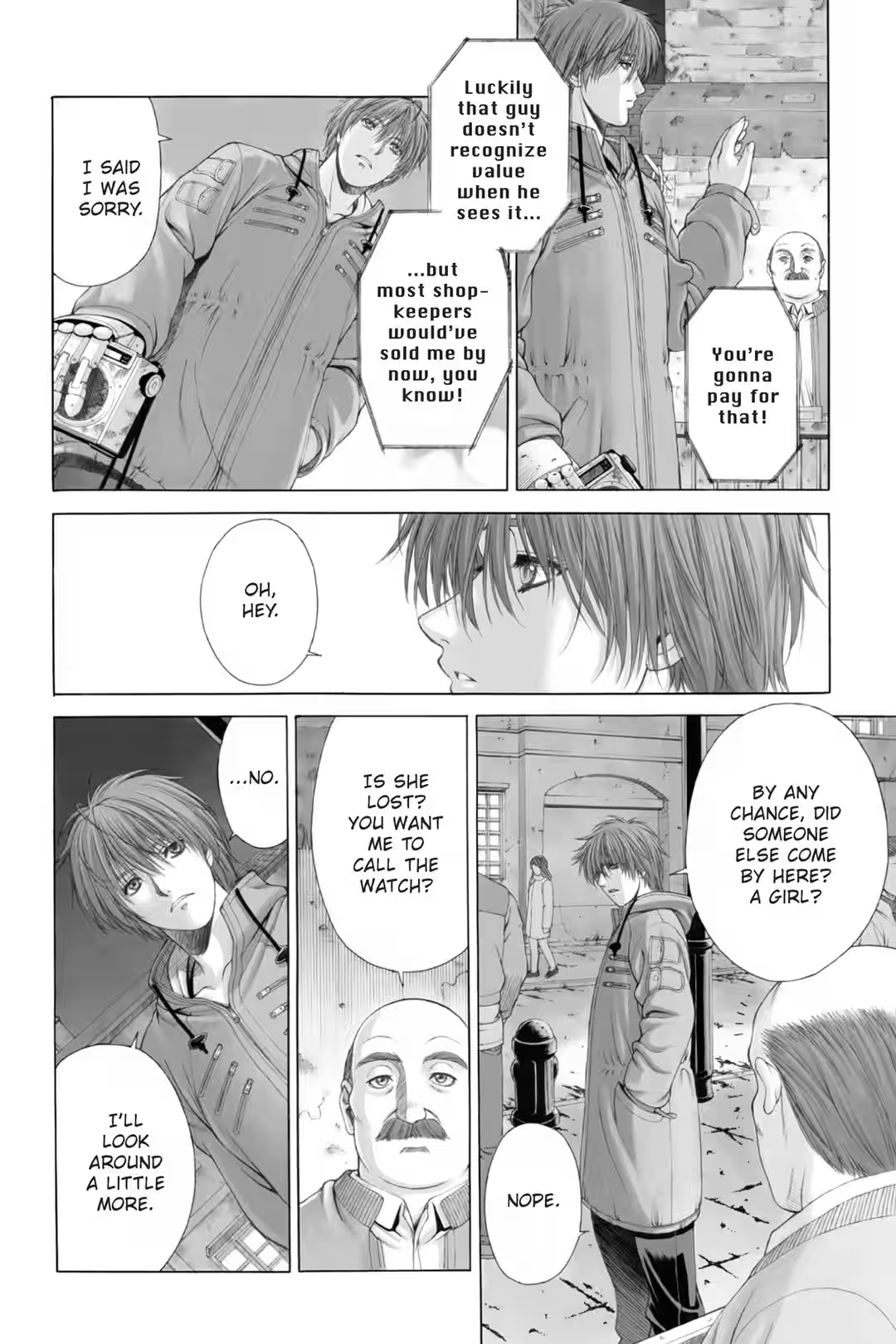

When Bearfoot jogged up close to them, Shiman turned from a conversation with one of the soldiers.

“Harvey. Just get over here.”

Shiman had to know exactly why he didn’t want to get near any Church Soldiers, and he could hear that knowledge in the man’s voice, but the commanding tone made it plain he wasn’t going to accept a refusal. When Harvey stepped cautiously toward them, the soldier who’d been speaking with Shiman took a look at Harvey’s face (at the patch over his right eye, more like), and raised his eyebrows a little. “Oh, it’s you.”

There was the casually overbearing attitude that all Church Soldiers had, but Harvey didn’t sense any particular hostility in the way he talked. He rummaged through his memories, wondering if they’d met somewhere before, and just barely managed to fish the man’s face out of one of the many memories filed under “couldn’t care much less.” He was pretty sure this guy was that platoon commander who’d been at the station the day they’d arrived in Westerbury.

He looked questioningly at Shiman.

The only answer he got was a harsh-voiced question: “Harvey, why weren’t you with Kieli today?”

Harvey had no idea what that had to do with anything, and it sure as hell didn’t explain what he’d been called here for. He didn’t try to hide the irritation on his face as he said, “No reason…” Why was everybody ganging up on him about that today?

Shiman gave a displeased sigh and broke off the conversation for a minute to scatter the performers who’d come up to see what the commotion was. “You don’t all have to stick around here. There’s nothing to worry about, so just go on about your business.” He waited to turn back to Harvey until there were a few less eyes on them.

“Westerbury isn’t a carefree little place like those country towns you find east or south of here. You can’t tell me you don’t know how dangerous it is for a girl to go wandering around downtown at night by herself.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Kieli went downtown today, didn’t she?”

“…” That’s news to me. When he clammed up instead of answering, Shiman continued, admonishing him in a low voice.

“You’re the only one she has. Be responsible and look out for her.”

“Shiman, what are you talking about?” Harvey repeated, frowning. He was getting lectured for something he didn’t even understand without getting any answers to his own questions, and it was seriously starting to piss him off. “Do I have to know what Kieli’s doing every second of the day?” he growled, half to the troupe leader and half directing a protest toward the radio. “It’s not like I’m her guardi—”

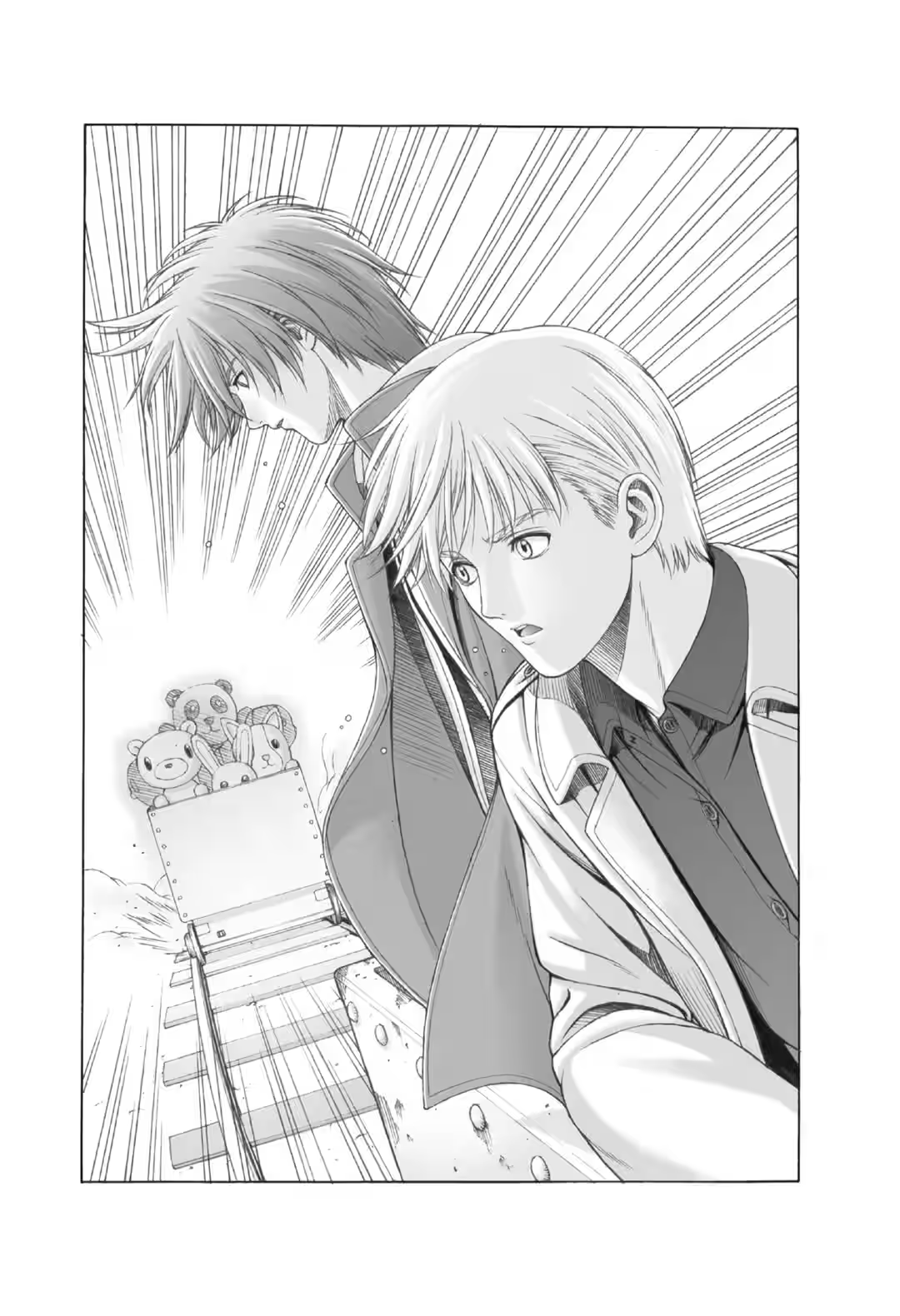

Before he could even get the sentence out, a fist flew at his right cheek out of nowhere. His guard had been down completely, not to mention the fact that Shiman, who was right-handed, had deliberately come at him from Harvey’s blind side with his left fist; by the time he figured out what was happening, the blow sent him flying. Reflex kicked in before thought, and he shot his left hand out fast enough to keep himself from hitting the ground full-on, but he’d lost hold of the radio. It tumbled away along the ground.

“…Wha…?”

Never mind the pain or the rebellion some part of him must be feeling; for now he was mostly just feeling surprised at being punched. Propped there inches from a flat-assed landing on the ground, he raised his head and gaped blankly up at the other man. Shiman turned away without even sparing him a glance. Shaking out his left hand, he called out, “Bearfoot, you help carry her. You can put her in my truck.”

“Y-yessir!”

Bearfoot, who hadn’t gone back with the others, jumped up as if he’d been stung. Then he circled around to the back of the Church Soldiers’ truck, keeping the corner of his eye on Harvey all the while. Harvey heard him exchange formalities with the soldiers, and then before long he was climbing back down to the ground, carrying something big and heavy wrapped up in a blanket.

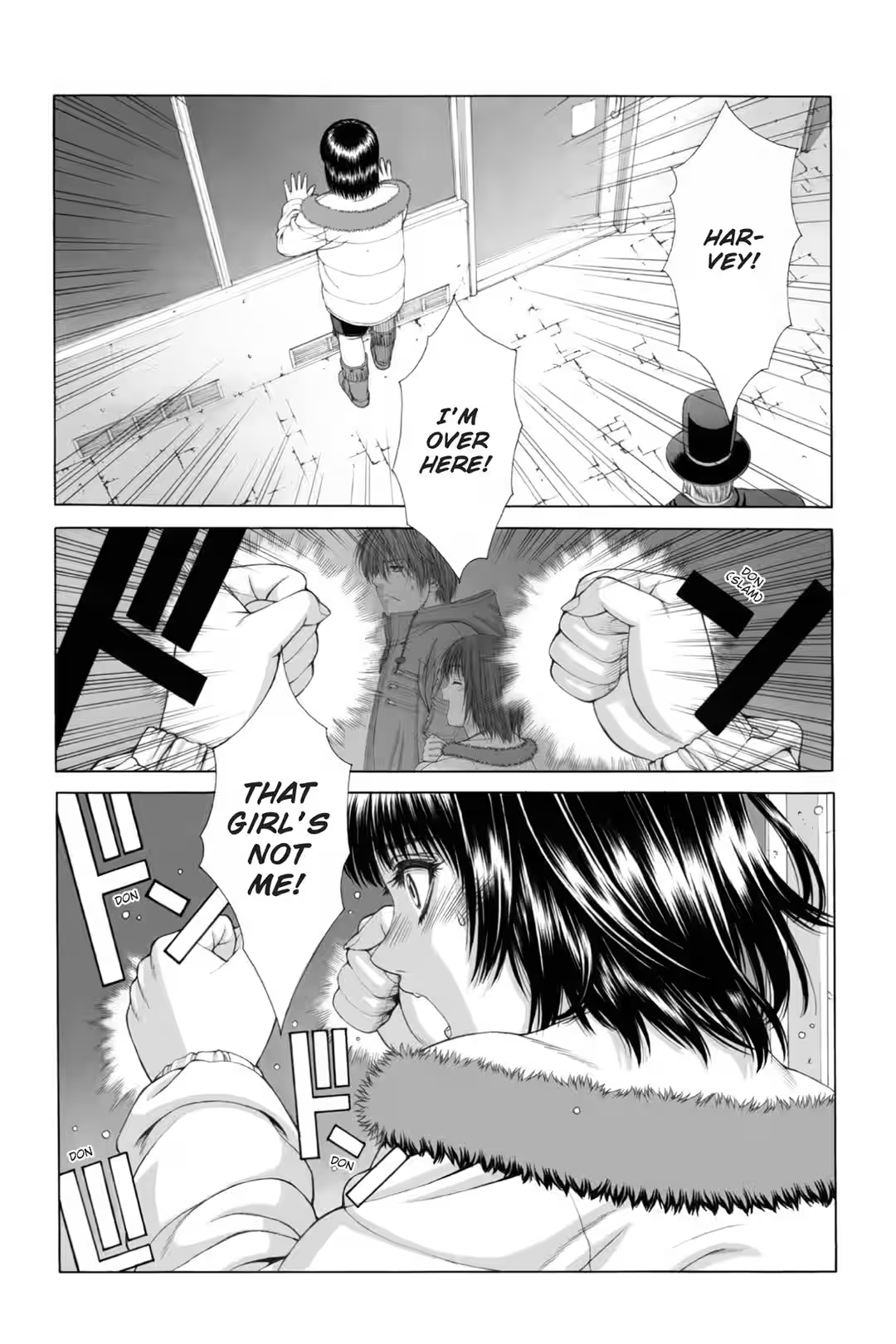

Shiman was still standing in front of him; over his shoulder Harvey saw the long black hair of the girl whose head was lolling on Bearfoot’s arm.

…He saw it, but that was all: His brain hadn’t caught up to his eye.

His mental gears had ground to a halt the second he’d been hit, and they wouldn’t start back up again. He’d missed his chance to stand up somehow, so he stayed sitting on the ground, watching the girl being carried away without any real reaction. Even when he saw the scrape on her cheek and the condition her clothes were in where the blanket didn’t quite cover them, for the moment, at least, he didn’t feel a thing. His eye was just superficially recording images.

After a small eternity the wheels began sluggishly moving at last, but one or two of them still didn’t quite engage…

And the first thing he registered was how grateful he was to Shiman.

If the man hadn’t hit him beforehand, he probably would’ve killed someone right then and there.

The park’s night watchman had found Kieli collapsed at the bottom of the footbridge, the Church Soldiers had been informed, and by sheer coincidence that platoon commander had been the one to respond. He’d recognized Kieli’s face, so she’d just been given rudimentary first aid and then transported to the camp. That much Harvey more or less grasped from the conversation Shiman and the others were having a little way off. But as he sat rolling the chipped-off fragment of one of his back teeth around on his tongue, about half of their words washed right over him without registering. He’d cut his tongue on the broken tooth. It hadn’t stopped bleeding yet, and his mouth was full of its bitter metallic taste.

The overhead light wrapped the rear of the truck in a dim glow. It wasn’t a wide space to begin with, and it was packed with luggage to boot. The truck Shiman called home was the only one to have a real, if simple, built-in bed: a perk of being troupe leader. Harvey crouched down next to it and gazed up close at the face of the girl lying on it. Though everything around them was bathed in yellow light, her scraped cheeks seemed to stand out, looking horribly pale. Suddenly Harvey felt uneasy. He touched her forehead with his left hand, and felt the relief come over him when he made out a faint but definite warmth there.

He didn’t care who’d found her. More importantly—

“…Who did they say did this?” he murmured without raising his eye. At the very edge of his peripheral vision he could see Shiman and the platoon leader, who were deep in conversation where they sat on the rim of the trailer bed, turn toward him. The platoon leader shook his head.

“They were long gone when we found her. I’m sure it was some of those downtown punks, though.”

“Huh. Downtown, eh?” repeated Harvey in an incongruously emotionless voice. That was all; he hadn’t said a word about what he planned to do next, but Shiman cut him off at the pass just as if he’d gone on speaking.

“Now look, you,” the troupe leader said sharply. “Don’t you even think about storming out there to find them right now, you understand? Stay with her.”

Harvey didn’t reply. Still without raising his head, he lightly brushed a lock of hair off her cheek. When he leaned his head in close, there was a sharp disinfectant smell. He touched his forehead to hers and mumbled, “I’m sorry…”

And that’s when he realized something was off.

He froze in that position for a few seconds before abruptly raising his head and staring hard again at the face of this girl who looked for all the world like she was just asleep.

“…Kieli…?”

Obviously there was no answer, but—something was wrong. “…Herbie,” whispered the radio he’d set on the pillow, pitched so that only Harvey could hear. He cast a sidelong glance at it, and they silently confirmed their thoughts with one another. Now Harvey was sure what was off.

She wasn’t there.

Somewhere behind him voices were exchanging pleasantries, and he could sense the two men at the truck entrance standing up.

“Harvey.”

At Shiman’s call, he finally turned to face them for the first time. The platoon commander had already left the truck and set off walking, but Shiman stopped in front of the entrance and jerked his chin, as though he wanted Harvey to come with him.

Harvey stood up without paying attention and whacked his head against the low ceiling. He didn’t react to that, though; he just started walking away from the bed, and then, a thought striking him, he leaned lightly back down and grabbed the radio’s strap. When he climbed out of the truck with it, Shiman was waiting outside. The troupe leader signaled with his eyes at the platoon commander’s robed back.

“We’re lucky; he’s a pretty understanding sort of guy. I’m going to the station with him for a bit while I’m paying my thanks. I trust I can leave things here to you?”

“Yeah. Tha—”

Halfway through the word, the pool of blood in his mouth got caught in his throat, and the thank-you he’d meant to say never came out. Instead, he coughed up a few gobs of blood and that shard of tooth; when Shiman looked down at them, his expression softened and he looked a little embarrassed.

“Sorry.”

“It’s fine,” Harvey said, shaking his head. He wiped the corner of his mouth with his coat sleeve. “Your hand’s probably worse off. You really let it fly.”

Shiman laughed, massaging his left hand. “Don’t worry about it. I’ve always wanted to try taking a swing at an Undying.” He flashed Harvey a grin. He might’ve said “Sorry,” but he sure didn’t seem particularly sorry. Not that Harvey could really say he cared.

“Good, so you can talk now. You’re sane, then?”

“Yeah…fine.”

Hearing the words out of someone else’s mouth, it finally hit him how normally he was managing to respond to conversation. Harvey’s head felt so clear it surprised even him.

“I’m fine,” he repeated, more definitely. A hand reached out and ruffled his hair—not a stuffed bunny’s this time, but a normal human hand. He was released quickly, and by the time he’d shaken his head and raised his eye to look, Shiman had already turned his back and begun walking away. Harvey could see the headlights of the truck that had brought Kieli here from where it was parked across the clearing.

After the sounds of several doors opening and closing, the beams changed direction and pulled away toward the camp exit to the loud accompaniment of fossil-fuel engine noise and tires crunching over rocky ground. But the sounds faded into the night even as he watched, and soon the usual faint white noise of the camp nights returned. The atmosphere in Shiman’s troupe’s quarters seemed a little strained now, but the other troupes were probably spending their night just like they always did.

As if to disrupt that peaceful silence, grating, ear-splitting static began to stream from the speaker of the radio dangling from his hand.

“…Who the hell did this?…I swear I’ll kill the bastard…!”

“Corporal,” he admonished quietly, but the static only got louder, and black particles spewed forth from the radio’s speaker in time with its snarling breaths, swirling together to form the face of an enraged soldier.

“Corporal, calm down,” Harvey repeated, sighing. “Don’t YOU tell me to calm down!” The fuzzy soldier’s mouth moved in concert with the howl of the speaker. “That’s why I told you to worm it out of her! This is all your fault for being so goddamn indecisive!”

“I know it’s my fault.”

“Then where do you get off looking so calm and—”

“Shut up and calm the hell down!” Harvey shouted back abruptly, jabbing his fist straight out to the left and slamming it into the side of the truck. The impact made a resounding bang and rocked the whole vehicle. A split second later the body of the radio swinging from his hand by its strap crashed into the wall, and the noise-cloud scattered like a swarm of insects dispersing.

The static cut off. Suddenly the mood was broken, and everything around them was quiet. Harvey stayed stiff for a while, clenched fist still pressed into the truck wall. Then:

“You calm now?” he muttered in a low voice.

“…Yeah.” The radio’s voice answered him back in the same lowered tones, and at that Harvey finally peeled his fist away from the wall and lowered his arm. The wall was more than a little warped, and some of the paint had come off, but it was an old truck to begin with. Probably nobody would notice as long as he didn’t say anything. A little of the radio’s paint had peeled off too, bringing it that much closer to junk.

Any other day, the girl sleeping in the truck might’ve jumped awake in a panic, but fortunately—if “fortunately” was a word he could use for this—there was no sign of her stirring.

Harvey’s left hand began to throb insistently. Maybe he’d cracked a bone. He didn’t shut out the pain, though; he just let it be.

“I’m heading out to look for Kieli. You stay here.”

“Don’t be stupid! Of course I’m coming with—”

The radio’s anger was rising again, but Harvey cut it off. “Somebody’s got to keep an eye on this one too, and you know it,” he reasoned quietly. “I’m asking you because you’re the only one I can trust.”

There were no more objections after that.

His left hand throbbed. When he clenched it into a tight fist it hurt even worse, but in exchange his mind cleared. Harvey felt as though he should probably be surprised at how coolheadedly he was managing to think right now.

Perfectly coolheadedly—

For maybe the first time he could remember, he was very seriously thinking about how to best kill someone he’d never even seen.

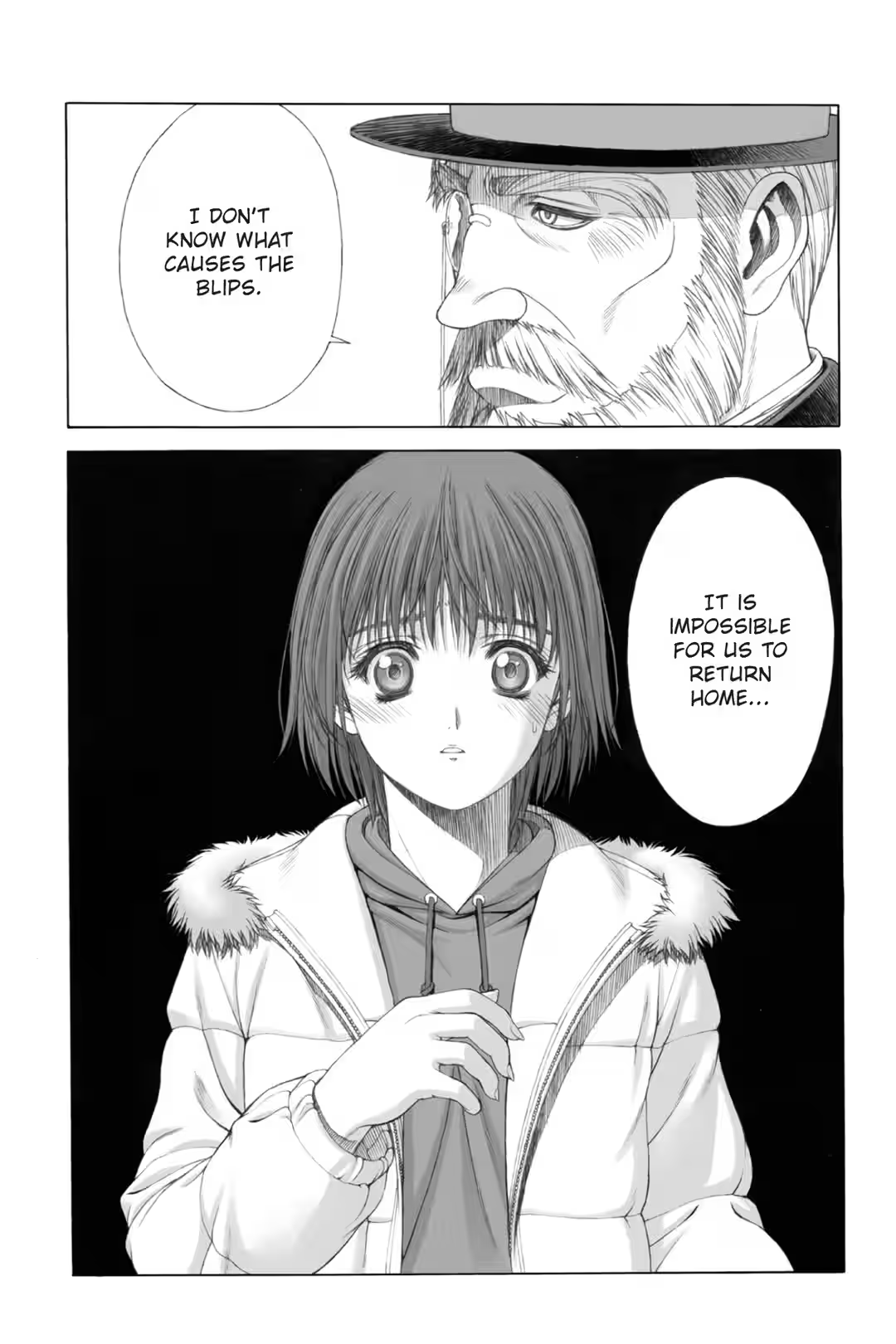

Kieli had entered boarding school the spring she was eight years old, when her grandmother died. Up until that point she’d never been to a real school; she’d just gone to a Church “playscheme” program two or three times a week. Considering that she’d been plunged into third grade with so little experience, not to mention the fact that (and this was probably the more important reason) she’d begun to grow introverted pretty much overnight, it seemed only natural that she’d had a hard time making any friends.

Now she found those memories springing to her mind as she walked slowly down the corridor, killing time.

She’d been far shorter than the average child; she remembered the top shelves of the lockers, the latches on the windows, and the flyers on the bulletin board all being too high up for her to reach, even when she stood on her toes. But now, walking down a hallway of classrooms for about that same grade level, everything was within easy reach. Nothing came higher than chest level.

Kieli’d come to this school just a few hours earlier, so it shouldn’t have held any memories for her, but for some reason the smell of it made her feel nostalgic. The long corridors, the dusty overhead lights, the thin tin-plated lockers, the bulletin board covered with ragged posters—they were all old and faded, but it was easy to tell that they’d been well loved and well used for many years. It all made for a tender scene that harmonized with the sandy sky outside the windows.

While she’d been getting her scrapes disinfected in the nurse’s office earlier, she’d heard a little bit about this ruined city and the school. (And “a little” really meant a little…the redheaded boy didn’t particularly like explaining things. Kieli couldn’t say that was unexpected.) Most of the students had evacuated once the street fighting had gotten worse. There were less than ten still at the school, all of them orphans. There wasn’t a single teacher left, either. A school where children lived all by themselves…

And apparently this place really was South Westerbury after all. But in the South Westerbury Kieli knew, the War had ended long ago, and there was a theme park standing over the ruins of this city.

I…guess I must be a wandering spirit now, huh…

The other Kieli lying on the ground hadn’t looked dead. She hadn’t exactly observed things very carefully, since she’d fled in confusion almost right away, but that Kieli hadn’t seemed obviously dead to her like the corpses of those soldiers she’d seen in the ruins. The spirit leaving the body—after Bearfoot had told her about his ability, it had occurred to her that she might have it, too; so, since getting here, she’d been figuring that maybe she’d unconsciously done it. Half figuring, and half hoping like mad.

Still, that didn’t explain what this space she was in now was…

When she ran her fingers over one of the hallway’s window frames, it felt cold and real. She’d gotten her wounds treated just like normal, too. The antiseptic had stung, and she’d cried out a little before she could stop herself.

She could understand that this was apparently the town back in the War era, but she had no idea what’d happened, what kind of space she’d wandered into, how to get home, or even if she could get home.

Harvey…I want to go home…

Thrusting her hands into her coat pockets, she trudged down the hallway with her head lowered. Now that she’d noticed how oversized her sixteen-year-old self was for the younger kids’ hallway, alongside the nostalgia came a feeling that she was a lone outsider, alienated from this place. It made the at-loose-ends feeling even keener.

“Aw, isn’t it time yet?”

“Just a little longer!”

Bright, excited voices and a warm, milky scent wafted to her from the other end of the hallway. Kieli lifted her head to see a sliding door a little way in front of her. It was wider than the normal classroom doors, and above it was a green sign with the word LUNCHROOM painted in white ink.

She walked past it and peeked quietly inside through the open hallway window.

“Yay, it’s got milk in it today!”

“It’s for our guest.”

“You’re in the way! If you’re going to stand there, carry that for me.”

There wasn’t much equipment left in it, but it seemed to be a kitchen, just as the sign had said. Five or six kids were pushing at each other as they gathered in front of a stockpot on a commercial stove that stood a little too high for a child to use.

At first Kieli thought they must all be working together to cook, but when she looked closer she saw that only about two of them were actually working; the rest were just chatting or peering into the pot and trying to sneak a taste. Aluminum bowls filled with milky-white soup were crammed so closely together on the counter that they rattled against each other, and the one on the end looked so much like it was going to fall off any moment that Kieli found herself getting anxious.

“Hey, Sarah’s putting more of the good stuff in Joachim’s soup than anyone else’s!” teased one of the younger boys.

“Cut it out, that’s not true!” the girl standing at the pot doing most of the work denied, red-faced. Kieli figured she must be in sixth or seventh grade. Her shyness was so cute that Kieli forgot the circumstances long enough to let out an embarrassed laugh of her own.

“Joachim”…they must mean the same Joachim…

She remembered the corpse-robbing boy who’d brought her here from the ruins of the battlefield. He’d certainly had the same cold blue-gray eyes as that Joachim.

And then there was the other one…

“Tick, tock, tick, tock!” Kieli heard an excited young voice sing to herself. She tore her eyes from the lunchroom and turned around to see the redheaded boy and the girl he’d called Elisha walking side by side up the hallway. Big bandages adorned the bare knees that peeked out from under Elisha’s jumper. Ephraim had patched Kieli up first without giving her any choice in the matter and then kicked her out of the nurse’s office, which was the whole reason she’d been wandering the hallways at loose ends.

“Tick, tock, tick, tock!”

Elisha had been crying just a little while ago, but it seemed like she was as good as new already. She was stressing the rhythm of the “tick, tock” bit a little and half-marching to the sound of her own voice. One foot lifted high in the air on each “tick,” and on the “tock” it hit the floor with a loud stomp. Kieli thought that would’ve made Elisha’s legs hurt more, but she didn’t appear to mind.

“You’re making too much noise,” criticized her companion, scowling. Elisha stopped singing and turned to look up at the taller boy next to her.

“When will the school clock stop, Effy? When the old incimmerator man dies?”

“‘Incinerator’…you mean the janitor? He’s been dead for ages.”

“So who has to die for it to stop?”

“Uh…”

The boy was stuck for a reply, and his fed-up expression and the way he let his gaze wander away from her were both exactly the same as Harvey’s reactions whenever Kieli asked him a difficult question. She pegged him as an eighth- or ninth-grader. He was about the same height as the boy Joachim; in other words, not too far off from her own. That made them average-sized for boys their age—a little smaller than average, in fact. Kieli’s imagination couldn’t even connect them with the two tall men she knew.

I wonder if they’re going to hit their growth spurts now, she mused idly, and then realized the situation she was in. A chill ran down her spine.

Decades in the past for Kieli, but probably several years into these children’s futures, Ephraim and Joachim had already died in battle…

“Food! Food!” caroled Elisha to exactly the same tune, stomping into the lunchroom. Only the “tick, tock” lyric had changed. The boy Ephraim watched her go with a resigned look; Kieli stood dumbly at the lunchroom window; and somewhere in there, their gazes met.

It’d been a long time since she’d seen both of those copper-colored eyes. That and a jumble of other things in her mind made her weirdly nervous. Eventually she figured she should at least thank him for patching her up, so she said flusteredly, “Um, thanks for before.”

“Eh, I had to clean up Elisha anyway.”

Yep, that was exactly the curt response she’d expected.

Glancing at the younger kids in the lunchroom over his shoulder, Ephraim lightly sat himself down on the hallway windowsill. “I’m the oldest one left, so for some reason these guys treat me like the leader,” he grumbled, with the air of someone deliberately making excuses. “Even though Joachim’s the exact same age!” Then he started fumbling around in the pockets of his duffle coat. Kieli was a little surprised to see him pull out a pack of cigarettes.

“I didn’t know you started smoking so young,” she said, and then panicked a little because it kind of came out sounding as if there was something behind it. But no, it probably wasn’t that weird a thing to say, as long as she didn’t make a big deal out of it…The boy didn’t seem particularly suspicious. He just nodded, drawing a cigarette out of the pack with his mouth.

“Yeah. I get can ’em from the soldiers sometimes. Half I sell, half I keep for me.”

“You get stuff like that from soldiers? Aren’t you scared…?”

That question got her a more dubious look than the first one.

“What good would it do to get scared? It’s a way to make a living.” This must be a matter of course to the kids in this era.

He proceeded to light the cigarette with a small cylindrical lighter that Kieli guessed was army issue too. The sounds of the little kids horsing around in the lunchroom wafted through the window from behind him. There was silence for a few moments, and Kieli watched, again a little anxiously, as more soup bowls were precariously lined up on the big counter in the middle of the kitchen.

“Next year,” murmured Ephraim as he blew out a stream of smoke, in the emotionless way that was so familiar to her. “Next year, Joachim and I will be soldiers. I mean, we’ll get paid, and we probably won’t die, but I kind of wonder what’s gonna happen to the runts after that.”

“Soldiers…you mean you’re going to war?”

“What else is there?”

He said this as though it should’ve been obvious. Without thinking, Kieli cried fervently, “N-no, you can’t! You’ll die!” Then she clicked her mouth shut, surprised at herself. Ephraim gave her a bewildered look.

…Was there any point in telling this boy that he’d die if he went to war? In the “present” that Kieli knew, that was a factual event that had been over and done with long ago—and she couldn’t even say for sure whether this place was really connected to the “present” she’d come from anyway.

“You’re weird,” said the boy Ephraim, furrowing his brow at Kieli and giving her an openly dubious look. Well, she had burst into a passionate appeal and then abruptly clammed up, so she couldn’t really blame him. Then he smiled a little, something striking him. “I won’t die. It’ll be fine.”

In the face of that totally normal, unguarded smile, Kieli felt her heart jump in spite of herself. While she was lost in the silly thought that Harvey might look cute wearing the same expression, Ephraim was bending his upper body backward through the window to look into the lunchroom.

“Something smells gross. What’s in today’s soup?”

“Milk and chickpeas,” answered the girl on meal duty as she put a slice of bread next to each soup bowl. She said it with an air of pride, so maybe that was fancier than what they usually had. Ephraim didn’t seem impressed. “Don’t put milk in it!” he griped, face twisting. The younger boys who overheard seized on this and instantly began to jeer.

“Ephraim, you’re too picky!”

“You shouldn’t skip your milk just ’cause the teachers aren’t here!”

“That’s why you’re so scrawny, you know!”

“You’re scrawny!” Elisha chimed, though Kieli was pretty sure she didn’t actually know what “scrawny” meant. Now even the littlest girl was ganging up on him…

Ephraim frowned around his cigarette. “Shut up! I’m not getting gum for you guys anymore.”

“You’re being a ty-rant just ’cause you’re older!”

“He’s a des-pot!”

“Come on, guys, be quiet. The food’s all ready, so go get everybody, okay?”

Unrelenting noise that made her want to cover her ears. Was this how loud a normal coed school was? The chatter of the girls at the boarding school had been deafening too, of course, but everyone’s voices had been relatively similar in tone, so it had never turned into a grating jumble of different noises like this.

While Kieli stood wincing at the racket so loud it spilled all the way into the corridor, Ephraim turned back to her one more time and jerked his chin toward the sliding door with the LUNCHROOM sign. “Go around that way.” Not that he used the real entrance himself—he just hoisted his legs over the windowsill and hopped down on the other side.

Kieli obediently started moving toward the door before changing her mind and copying Ephraim instead, putting a foot to the window frame with a grunt. She’d wanted to try this ever since boarding school, after all.

After she’d gotten over the sill and hopped down into the lunchroom, she heard a voice behind her say, “Something smells gross.”

Kieli turned her head. A boy with blue-gray eyes was peering in through the window, nose twitching. Kieli reflexively flung herself backward to get some distance between them. He only spared her a glance before returning his gaze to the center of the lunchroom.

“What’s in today’s soup?”

“Milk and chickpeas,” repeated the girl on serving duty. The boy Joachim’s face twisted. “Don’t put milk in it!” he griped.

The younger boys who overheard said in chorus, “Joachim, you’re too picky!”

“Shut up!”

Watching this exchange, Kieli burst out laughing before she could help it.

“What?”

“N-nothing.” Fixed with a piercing blue-gray glare of displeasure, she ducked her head and bit back her laughter. It took some work to control the twitching of her cheeks for the next little while, though. These two react the exact same way…

“This way, miss. If our guest would please follow me?”

Beckoned a little self-importantly by the cook, Kieli awkwardly let herself be urged toward the head of the counter and placed in what seemed to be a sort of “birthday-girl seat.” The other children all gathered around the counter full of bread and soup, too, dragging stools with them. Apparently, this was where they usually ate.

They were more or less seated by age: To the left of Kieli’s seat of honor was Ephraim, and the kids after him were in order by grade level right down to the last seat by the door, where Elisha sat as the youngest. And next to her, diagonally from Ephraim and totally out of grade order, sat Joachim. This must be the seating arrangement they’d settled into naturally; the one that felt best to everyone.

As soon as they were all seated, everybody closed their mouths, and the room fell so silent that all the ruckus of moments ago seemed unbelievable. There was a slight tension in the air, as if they were waiting for a signal.

The girl on lunch duty looked at the oldest student and said, “You’re not going to pray today, either?”

“Nope,” Ephraim replied without hesitation, jamming his cigarette butt into an empty can. She looked somewhat unhappy with him, so he added irritably, “It’s fine. There aren’t any adults here.” He picked up his spoon, propped his elbow on the counter, and started shoveling soup into his mouth.

There wasn’t even a “Let’s eat,” let alone a prayer, but apparently that was the signal, because the other kids all made little happy squeals and reached for their own spoons to begin the meal. Utensils clinking noisily against each other, chattering voices talking with their mouths full—the quiet had reigned for only a few seconds before, in the space of a blink, all the previous war-zone-level clamor returned to the lunchroom. Kieli found this mealtime scene so staggering that she forgot to eat her own soup and just gaped in wonder for a while.

“Aren’t you gonna eat?” asked Ephraim, glancing sidelong at her from his neighboring seat. (He really did seem to hate the milk soup, but he was grudgingly swallowing it down anyway, chasing it with bread to cut the taste, as if he refused to let a little unpleasantness make him skip a meal.)

“Oh, right, thank you for the food,” said Kieli, and hastily picked up her spoon. She was pretty sure she was the only one of them to give the customary thanks.

Feeling cowed by the high spirits of everyone around her, Kieli scooped up a spoonful of soup and brought it to her lips. She let it linger on her tongue before she swallowed, but it was so thin and powdery that she couldn’t really tell what it tasted like. Compared to the signature dish at Buzz & Suzie’s Café in South-hairo, a thick milk stew of poultry, eggs, and chickpeas, this was practically just flour and water.

When she glanced up, though, she saw that the cook and the smaller kids were all looking at her as if they were gauging her reaction.

“…It’s good,” she said. It wasn’t, at all, but she faked a smile before even thinking about it. Growing embarrassed, Kieli looked back down at her soup and stirred it pointlessly a few times before lifting the next spoonful to her lips.

A drop of water splashed down onto the surface of the soup there, making tiny ripples.

“…Kieli?”

The lively atmosphere abruptly chilled over.

“Is something wrong…?”

“Did it taste that bad?”

“Oh—I-I’m sorry…!” Kieli excused herself, quickly wiping her cheek. But the tears just kept welling up, and they wouldn’t stop coming. “I’m sorry, that’s not it…” The perplexed gazes of the children all concentrated on her as she covered her mouth with both hands, one still clutching the spoon, and did her best to hold in the wail. No, I can’t cry here…

Then Ephraim was leaning his own cheek on the counter to peer up at her face from below. “Does it have something you hate in it?”

“You don’t have to eat it!”

“No, I—” Kieli’s voice stuck in her throat before she could finish the denial, so she looked at her feet and just shook her head over and over. Those eyes on hers now, those eyes the same color as Harvey’s, made it even harder to control herself.

This was a place Kieli didn’t know. It was an era of people who’d lived through or died in wartime, long before Kieli had ever been born—

“…I want to go home…”

The murmur came out in the feeble voice of a lost child. She’d killed the wail threatening to escape, but now she was blubbering. She’d choked down that wail too hard. Now her lungs smarted.

Eventually Elisha started crying in fretful sympathy, and then even the rest of the younger kids’ chins began to tremble. The whole lunchroom felt as though they were in the middle of somebody’s funeral, but they all polished off every last bit of their bread and soup all the same.

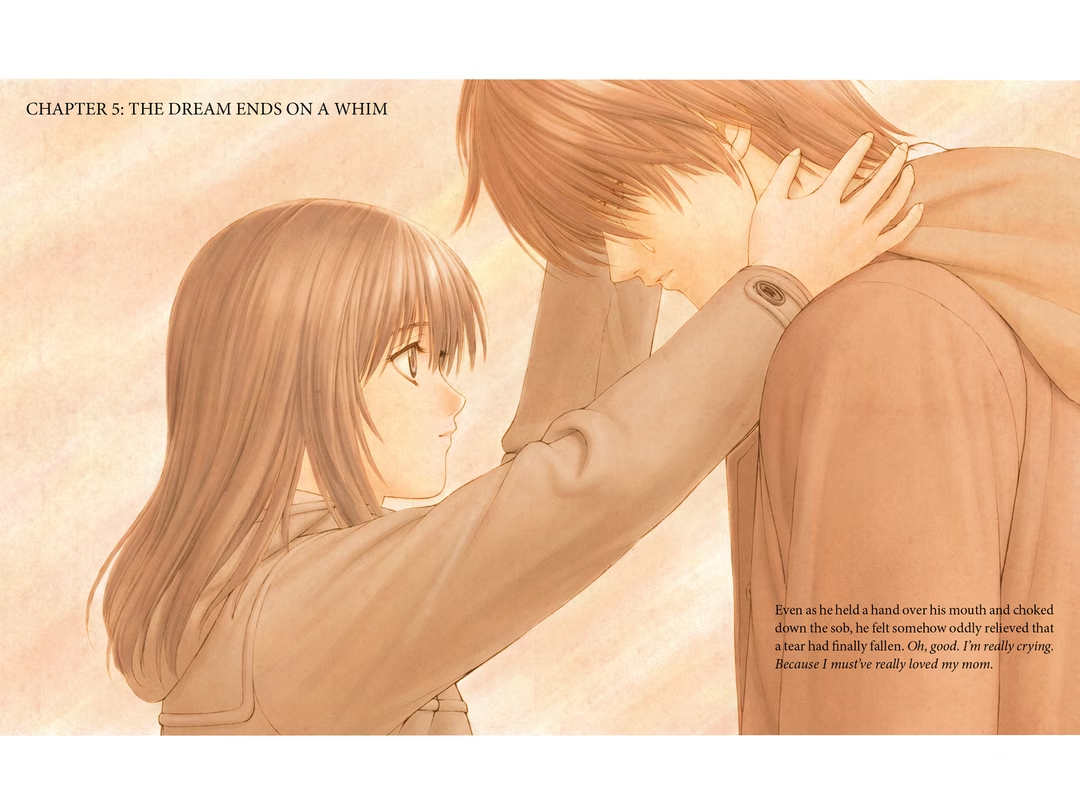

Ephraim’s mother died right after he turned thirteen. The conflict between North and South Westerbury was still going on, but the street fighting wasn’t too intense yet; schools and city buses were still functioning more or less normally.

He didn’t have any particularly happy memories of his mother. She was a sickly woman who’d never had strong nerves or a strong body, but after they had gotten word that his father, who’d been away fighting the War for a long time, had died in battle, she’d gotten even worse. From then on she rarely left her bed, and she spent the last month of her life in the hospital. He remembered two visits to her there. The first time was when he’d gone to fill out the hospital’s admission paperwork, and the second time was a full three weeks later, when on his way home from school one day he’d boarded the bus to the hospital on a sudden whim.

His mother was sitting in bed, propped up with pillows, and she looked far thinner than she had three weeks before. Her twin plaits of coppery hair were so dry that he half-thought they’d crumble like ash if he touched them. He drew up a chair, not to the side of the bed but to a little ways away, by its foot, and sat down. He’d come all the way here, but he didn’t have anything in particular to say, so time marched on in silence. There was another patient sharing her room; on the other side of the curtain that divided their beds, that patient’s child was spiritedly reporting the goings-on at school. Ephraim wondered if he should talk about that kind of stuff, but he got the feeling that would be even more unnatural than the quiet. He didn’t remember them ever talking like that when they were at home.

About twenty pointless minutes passed like that. Just when he was starting to think about heading home, even if he still hadn’t said anything, his mother broke the silence to ask quietly, “Why did you come to visit…?”

He stared back at her blankly, wondering why she’d ask him something like that. She kept her eyes on her hands where they rested on the blanket (he remembered her eyes as being a fairly plain brown color; he had plenty of red pigment in not just his hair, but his eyes, and someone had once told him that when he’d first opened them as a baby, his mother had been half-crazed with shock) and said, “I thought you hated me.”

“…Why?”

It was the first thing he’d said since coming to her sickroom, and the first thing he’d said to his mother at all in a long time. He’d always thought that if anything, he was the one she hated.

She didn’t answer him, but after a little thought, he could come up with several reasons. Compared to his friends’ families, they certainly weren’t a close family. In fact, an outside observer might have described them as a broken family. He got up on his own every morning and went to school without eating anything much, and he had never come home to find dinner waiting, either (which meant that in his home there’d never been a custom of praying as a family before meals). And his mother spent most days moping in her bedroom, so even when he was home he’d never had much of a conversation with her. They were managing to make ends meet on a subsidy, but he was the one who’d gone to fill out the application for it.

Still, though, life with that kind of mother was completely normal for him, so he said in a normal voice, “Because you’re my only mom.”

His mother didn’t respond or even look up, so he fell silent again, wondering if he’d upset her. After a while, he realized that her hands were trembling slightly where they gripped the covers. Thin, skin-and-bones hands, and thin shoulders he could make out even through the cardigan she wore. Belatedly, he registered just how thin she really was. He thought for the first time that maybe he should’ve visited a little more often.

“I’m sorry, Ephraim…”

Transparent tears pattered down onto the backs of the fragile hands on her blanket.

“I’m a failure as an adult…I…I couldn’t do anything for you…”

“Yeah…I’m sorry, too,” he said in the same normal voice. Ephraim wasn’t in the habit of being hugged by his mother or anything like that; they’d hardly ever touched. But just hearing her call him by his name for the first time in a long while was enough for him. At that point the day became a pretty happy one.

And that ended up being the last time his mother ever called his name. A week later, at school, he was notified of her death.

Because you’re my only mom.

He hadn’t thought much about the words before he’d said them. They’d just been what had come out of his mouth at the time, but now they bounced back to him as something to reproach himself with.

These runts have lost the parents they ought to be relying on, and now I’m the only one they’ve got…Well, even assuming he split the duty with Joachim, since the idea of taking everything on himself irritated him.

“…?”

Seized by a sudden sense of déjà vu, Ephraim looked up.

His eyes traveled to the wall clock above the chalkboard without any real thought. It was the analog clock type: a round face with its circle of unfriendly black numbers, framed by a black rim. It was just about as far from “personality” and “decorative flair” as you could get and still be in this universe. 52, 53, 54…The slightly warped second hand crawled oh-so-slowly around the yellowing clock face, marking a sluggish time. 57, 58, 59—

The minute hand clicked forward, and according to the time system of a faraway planet that had been in use here since the colonization era, it was 2:57.

…What was that? He felt as if he’d lived that exact same moment before—No, this is wrong. It wasn’t the déjà vu itself that bothered him; it was the fact that the déjà vu felt off. That it felt like something was mixed into the déjà vu that wasn’t supposed to be there.

…What the heck does that mean?

He frowned in confusion. He didn’t even understand what he’d meant in his own head. There was no such thing as déjà vu that looked different from what it was “supposed to” look like. You wouldn’t even call that déjà vu to begin with, would you?

He reached for the cigarettes in his pocket, and then remembered that the one he’d smoked in front of the lunchroom a little while ago had been his last one. I’ll go get the butt from the can later. Feeling somehow as if he didn’t know what to do with himself, he sat on the teacher’s desk and swung his legs back and forth, gazing at the white chalk scribbles that filled the board in front of him.

“Today Sarah and Nahar are on duty!” “←That’s wrong! Seth changed it!” “Elisha had another ‘accident’ today!” “No I didn’t!” “Ephraim and Kieli were kissing in front of the lunchroom!” “Attention: No soccer allowed today!” —And there was more: drawings, like the one of the twisting railroad line that ran from one end of the board to the other, and the ones of what he could only assume were girls even though he got the feeling the human body didn’t actually work that way, and that tiny little note in the corner—

“Please let the War end soon so we can go home.”

He didn’t know whom that faint, unpracticed handwriting belonged to, or when that sentence had been written there. But for some reason, no matter how many times new doodles got drawn over the old ones, that one note was always left alone.

When he stretched out his right hand and rubbed at the board with his palm, he smeared part of the railway sideways. Chalk dust stuck to his fingers. He thought he’d scribbled something here, too, but he’d forgotten which one was his. It must have been one of these. Any of them but the Please let the War end soon one. He didn’t have a place to go home to anymore.

In the afternoon the classroom was quiet. Quiet, racking sobs could be heard behind him up until just a little while ago, but apparently somewhere along the line that had settled down.

He twisted lightly at the waist to look back at the classroom. A black-haired girl was sitting all alone at a desk three rows from the window—he didn’t remember whose seat that had been, but it was the one with the marks where somebody’d carved a short word (probably the name of a girl he liked or something) with a utility blade and then scraped it away. He pegged her as a year or two older than he was, but ducking her tearstained face and shrinking in on herself like that she looked awfully helpless, and against his every inclination he found himself feeling about her almost the same way he felt about the runts.

“You okay now?”

She nodded awkwardly. “Sorry I acted so pathetic…and when I’m older than everyone here, too…”

“Eh, don’t worry about it.”

She’d burst out crying in the lunchroom, but the kids here weren’t a sensitive enough bunch to stop mealtime for that, so they’d all sat through the uncertain mood of the room and finished their food before doing anything else. Afterward the runts had left to finish their soccer game (they were making a racket in the classroom, so he’d told them to clear out). From outside the wide-open window came the chilly late-autumn air and the innocent whooping of the young boys playing in the schoolyard below.

He might feel a certain responsibility for the runts here at school as the eldest of the students, but he sure as hell didn’t owe anything to this girl who’d crashed into their lives out of the blue. And anyway, Joachim was the one who’d brought her here in the first place, which meant he didn’t have even the tiniest reason to look after her. He should just leave her be.

After he’d silently chanted Leave her be to himself about five times, his shoulders slumped and he heaved a long sigh. He disgusted himself sometimes.

Ephraim swung his legs around to the other side of the desk and sat facing the opposite direction. “Where’d you come from? I’ll take you back.”

“…I don’t know how to get back.”

“‘How to get back’?” He didn’t really get what that meant. “Is it far away? Don’t worry about it. There are still cars that’ll run back at the ruins. I can’t drive, but Joachim can, so—”

“That’s not it,” she interrupted him in a slightly louder voice. Blankly, he stopped talking. The girl looked up through her eyelashes to search his face, then let her gaze fall back down to a spot on the desk near the old carving.

She went on haltingly, carefully, as if she were telling herself the facts more than him.

“In the Westerbury I’m from, the War’s been over for decades, and it’s peacetime now, and there’s no army, and they built a park with a clock tower on this spot, and it’s a town of clockwork dolls, and there are never lots of dead people lying in the streets or anything, and…”

She paused.

“I…know a red-haired man named Ephraim. A long time ago, in the War, he…” At that point the girl faltered, and a short silence fell.

Tick, tock, tick, tock…

Mixed in with the cries of the boys chasing after their ball, he could pick out snatches of timid singing. It was a lispy girl’s voice. Must be Elisha. He could picture the youngest girl in his school squatting underneath the chin-up bars, drawing a picture in the sand there and crooning her favorite phrases from the song in clumsy but clear tones.

He glanced at the seat by the window, a bit baffled.

“Um…” Are you all right in the head? he almost asked, but she seemed so completely serious that he couldn’t help hesitating. He didn’t quite know how else to respond, though.

He hated to read, but he liked the library because it was quiet, so he’d gone there to sleep sometimes. Now he remembered an old book on one of the fiction shelves that he’d once skimmed through to put himself to sleep. It was about a cat who’d woken up from cold sleep thirty years in the future, and then gotten a time machine and gone back to the past to take his revenge (or something, he might have the details wrong). Okay, forget that for now. A part of his mind started trying to remember if the medicine or psychology shelves had any books on habitual delusions or pathological lying or anything.

“Erase that,” said a grumpy voice somewhere out of his line of sight. He turned to find Joachim standing outside the window that opened into the hallway.

“‘That’?”

“That.”

He followed the direction of that slate-gray gaze, looking over his shoulder at the scribblings on the chalkboard, but he couldn’t tell right away which one the other boy meant. After he’d let his gaze wander around the board for a while, the “Ephraim and Kieli were kissing in front of the lunchroom!” caught his eye.

He blinked and looked back at Joachim. “This?” he asked.

“No—huh?” Now it was Joachim’s turn to blink. He looked as though he’d been tricked somehow. “What was it again? It’s nothing. But I thought there was something…” What the heck does that mean?

This scribble…was this always here? Ephraim had seen it, but it hadn’t registered in his brain until now. While he tilted his head in confusion, Joachim propped his elbows on the window ledge and asked, “So, were you really, then?”

“No, we weren’t.”

“Right,” the other boy retorted, grinning.

Ephraim grabbed a piece of chalk and threw it at him. “No we weren’t!”

“Okay, okay. You’re so violent.” Somebody’d probably written it there to hassle them. Seth or one of his buddies, most likely. Sheesh.

He shot a glance at the girl sitting by the schoolyard-facing window, and they exchanged uncomfortable looks. He quickly averted his gaze. He swung his legs around again and faced back toward the chalkboard to look around for the eraser. Not finding it, he just rubbed out the names with his hand.

Joachim only watched silently, still not saying anything even after Ephraim had finished, so after a pause Ephraim turned around and said without thinking, “That’s all?”

Joachim frowned suspiciously. “What, is there supposed to be more?”

“What about the tanks?”

“Tanks?”

“No…what did I mean again?” Why did he have tanks on the brain all of a sudden? He’d been the one to bring them up, but he didn’t know what he’d meant. Something at the back of his mind was bothering him, though. There was that same feeling of the déjà vu being off. It was only a vague sensation, but he had this feeling as if some foreign element had crept in that wasn’t supposed to be here.

Her…?

He turned back toward the seat three rows from the window one more time, and the instant his eyes met the girl’s, he was suddenly sure what was off.

A girl who wasn’t supposed to be here—he could swear he’d been alone in the classroom until Joachim showed up. She hadn’t been here. Joachim hadn’t taken the right route back here because he’d picked her up, so he didn’t know about the tanks—Ephraim’s head started spinning rapidly.

With a start, he turned his head back to look up at the clock above the chalkboard. It was almost three o’clock on the dot. The second hand beat out a countdown as it moved toward the highest point of the circle. 9, 8, 7, 6…He’d seen this hour time after time after countless time. He was circling through the same time loop over and over. Wake up in the morning, play, eat, loaf around, and at three o’clock sharp, stray artillery fire in the schoolyard—

3, 2, 1…

“Joachim! The runts!” he yelled in the direction of the hallway as he slid off the desk and scrambled toward the schoolyard-facing window—

…0.

He heard someone scream out in the schoolyard.

The instant his subconscious realized he wouldn’t make it in time, he switched gears and reached for the girl by the window. “Duck!”

“Huh?!”

He grabbed her by her clothes and dragged her down to the floor. Immediately afterward, every windowpane in the wall overhead swelled up in a distended bowl shape. A split second later, they all soundlessly shattered to pieces—well, maybe they’d made a sound, but the shock wave had ruptured his eardrums, and for a while the world was closed off in silence. A white mist filled the classroom, blanketing his vision and making him blind as well as deaf. He wasn’t sure if the mist was gun smoke or tiny shards of glass.

Ephraim cradled the girl’s head to his chest and took cover behind the desk. Robbed of both sight and hearing, the only way he knew anything about what was happening around him was from the sensation of glass shards hitting his back.

It all took maybe half a minute, or maybe only a split second. The rain of glass on his back had subsided, but fine particles in the air still shrouded the room in white. Coughing, he groggily lifted his face. The slivers that had piled up on his head slid to the floor like sand. The girl holding herself stiff as a board in his arms also timidly raised her face. As soon as their eyes met, her face changed color and she started speaking earnestly, but his eardrums still weren’t working right, and all he saw were lips flapping. It seemed as though she was asking him if he was okay or something. Still without a clear idea of what the problem was, he put a hand to his temple. When he pulled it away, there was a thick smear of blood on his palm.

Now that his hearing was finally starting to return, he was assaulted by an awful, echoing wail like someone ringing a bell nonstop. The noise pounding at his brain made his head reel even more than the pain at his temple did. In some dim corner of his nonfunctioning mind, he just barely made out the first sound that seemed to have any meaning; it was Joachim’s voice shrieking about something.

“—raim! Ephraim!”

Joachim had been taking cover in the hallway; now the other boy was rushing to his side almost before he’d stood up. Ephraim didn’t see any reason for Joachim to look that desperate as he called his name—but what worried him a hell of a lot more was why he couldn’t hear Elisha singing anymore.

He let go of the girl in his arms and crawled over to the window on all fours. When he grabbed on to the frame, the jagged edges of broken glass cut into his palms. Ignoring this, he used the grip for support to draw up his knees and stick his face out the window.

Outside, it was quiet. Elisha’s voice and the voices of the kids playing in the yard had broken completely off. It was an everyday quiet, as if the place were just deserted because it was lunchtime; as if five minutes from now the brats who were fast eaters would burst out the front door, shouting excitedly. He wished it were true.

In a corner of the scorched, smoldering schoolyard, an ownerless soccer ball rolled aimlessly. It came to a stop in front of a chin-up-bar set so warped it could have been one of those weird sculptures you saw in front of train stations.

A little girl’s body lay in the sand below.

The sky stretched on forever in its unchanging cloudy sand color, and beneath it, somewhere faraway-sounding yet close by, the long, low boom of a cannon sounded.

At the top of the stairs on the south end of the bridge, he stopped walking.

Down the steps directly in front of him was an arched gate flanked on either side by two knights in plated armor standing silent guard. He spent a while engaging in a pointless staring contest with them before shifting his gaze to take in the view of the park that lay beyond the gate. It was still dark. The white face of the clock on the tower standing in the center of the park provided a faint source of illumination, revealing a shadowy clockwork town penned in by a maze of walls.

He didn’t see any sign of the girl he was looking for in what he could make out of it from here. Guess I have to go down there…He raised his palm and reached it out toward the nothingness in front of him, and then jerked it to a stop when, sure enough, he could feel that same magnetic field from before just a breath away. Harvey hadn’t been here since the first day of the Colonization Days holiday, but apparently it wasn’t the sort of thing that just disappeared over time.

The joint at the base of his pinky finger was weirdly swollen, and blood was oozing from it. After a moment of thought, he realized that must be from when he’d hit the wall of the truck. This was the first time he’d really looked at his hand since then, come to think of it.

Leaving his hand in the air, Harvey closed his eye lightly and concentrated, picturing drops of coal-tar-like blood crawling like dark insects over the hand he’d just seen and cling to the edges of the wound, knitting the damaged cells back together.

When he opened his eye a short time later, the skin of his left hand was intact again, with only a few traces of blood left on the surface. The fracture in the joint itself wasn’t completely healed, but he’d managed some basic first aid, anyway.

In exchange, a throbbing almost like the beginning of a migraine started up behind his right eye socket. He grimaced and jammed his hand into his pocket—but before he could do anything else, the faint sound of voices caught his ear.

“I’m telling you, I back went to check, and she was gone!”

“‘Gone’? How could she be gone?”

“Beats me!”

“Maybe someone carried her away?”

Several people were crossing over the bridge from the “new city” to the north.

“You sure she just didn’t wake up on her own and go home?”

“Who the hell said she was dead in the first place, anyway?”

“You did.”

“Dammit, what a waste…”

The voices echoing out of the darkness came steadily closer until he could make out three forms in the patch of dim light under the triangular streetlamp. Harvey half-turned from his position at the south end of the bridge and waited. Eventually they noticed him, too, and looked at him with naked wariness. He hadn’t felt any inclination to remember their faces at the time, but unfortunately—or perhaps fortunately, in this case—he did recognize them. They were the punks who’d kicked away his lighter downtown.

“…Huh. So it was you.”

As he spoke, he slowly turned fully around to face them. His voice came out sounding almost disappointingly normal. No blood thirst or anything in it.

Maybe they were wary of him because they thought he was a park guard or something; once they saw how he was dressed, they immediately let down their guard and started acting arrogant instead, walking right up to him with a sort of What do you think you’re doing here? attitude.

Looking Harvey over from head to toe, one of them let out an “ah!” of apparent recognition, and said the same slang word as last time. He couldn’t catch it today, either.

Harvey arbitrarily assigned them numbers: One, Two, and Three. Sure, one guy had gauze taped over his face, so at least one of them had a distinguishing trait, but he didn’t feel like giving them snappy nicknames and recognizing them individually. Once he’d decided on them as numbers, his sense that they were humans was automatically expunged from his consciousness. They started to genuinely seem like just some numbers talking.

“What’s your deal? You got something to say to us?”

Harvey hadn’t made a single move yet, but apparently they were spoiling for a fight. The guy on the left, “One” (or had he dubbed the one on the left “Three”? Eh, whatever), thrust out his right hand and shoved Harvey’s shoulder.

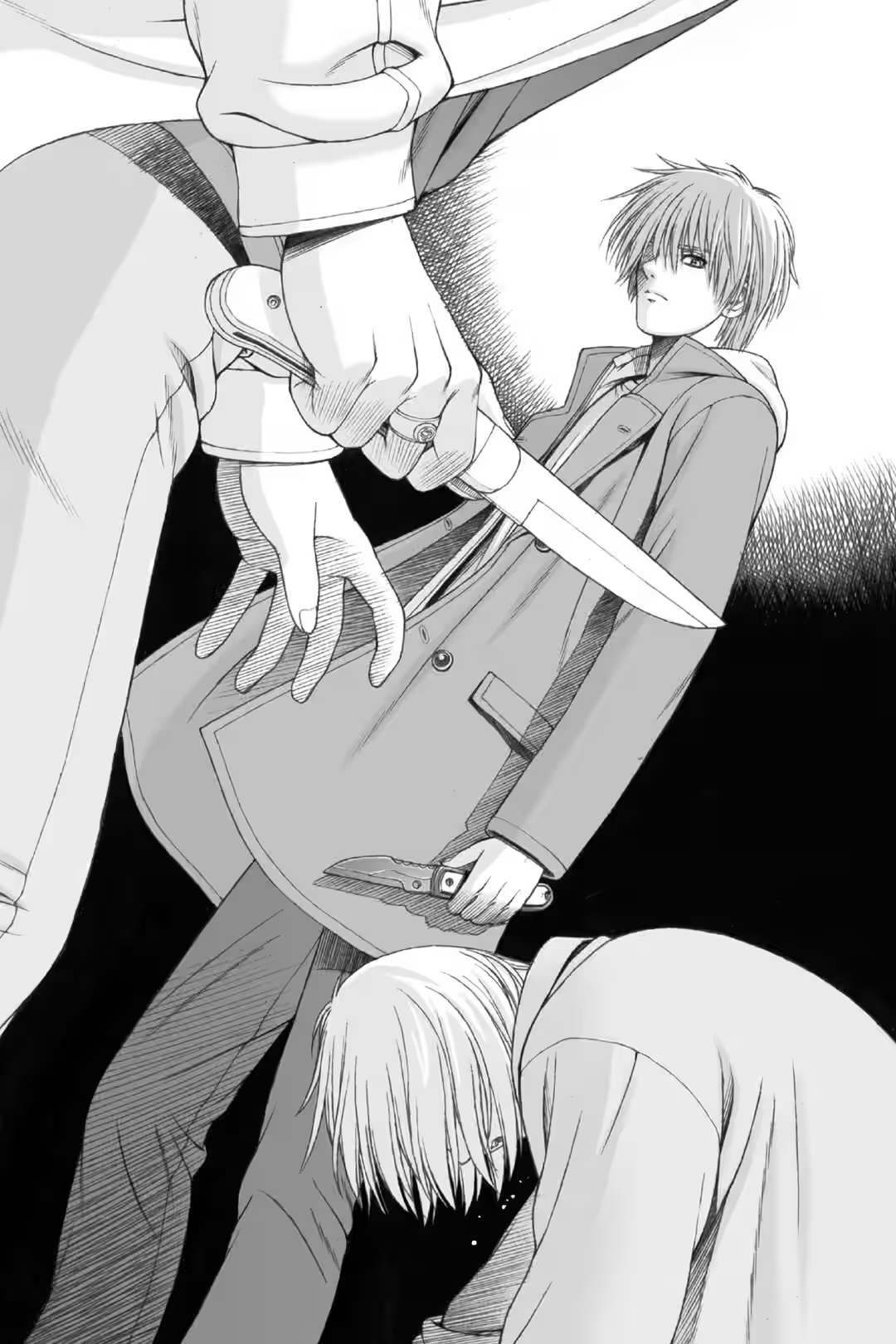

No sooner had Harvey taken his own hand out of his coat pocket to smack it off than One let out a shriek and suddenly jumped back. As the other two gave him funny looks, he cradled his right wrist in his other hand and curled his whole body into a ball around it. Fresh blood began to pour from it. Two and Three rounded on Harvey excitedly.

“You bastard, how dare you pull a stunt like that all of a sudden?!”

“Oh, so the ‘sudden’ part was bad, then. Sorry,” he replied in a flat voice, feeling his grip on the handle of the folding knife.

He’d carried it on him as insurance while he was looking for the “moving corpse,” but now he’d found an unexpected use for it. He hated weapons so much he’d ended up choosing one he knew wasn’t cut out for hand-to-hand combat. During his encounter with Christoph, he’d hesitated until the very last second and ended up never even using it. And yet for all that, today he didn’t feel any qualms. He was ready to use it right off the bat.

Harvey lifted his gaze from the blade.

“Okay, let me tell you beforehand: I’ll kill you.”

Before he’d even finished the sentence, he’d closed the distance between himself and Two. Two gave a cry of dismay, but managed to draw his own knife and put up a fight. Handle struck handle with a dull clang, and he pulled back slightly. Three seized that moment to come at Harvey from the side with his knife. (So they’re all walking around with blades? Dangerous characters.)

Harvey had no right arm to block with. He ducked underneath the blow; Three had too much momentum to stop charging forward, and from his crouched position Harvey aimed for a leg. A femoral artery. He didn’t feel the slightest hesitation about aiming for the vitals.

With an unintelligible scream, Three collapsed to the ground and rolled off to the side. As Harvey watched, the fabric of his pants turned bright red between the fingers of the two hands clamping down on it, and a sea of blood spread out on the pavement.

It just wasn’t satisfying; the blade hadn’t felt as if it’d gone in as deep as he’d meant it to. His fractured bone was loosening his grip. “Well, it has been a long time since I’ve been in a knife fight…,” he justified himself to nobody in particular, awkwardly wiping the blood and grease off the blade with the hem of his coat. Okay, then. When he transferred his gaze to the lone man who was still unhurt, Lone Unhurt Man said—Dang it, what number is this one again? Oh, right, Two. When his opponent spoke, the man’s voice and face were almost comically tense.

“You’re no amateur, are you?! Th-that’s not playing fair!”

“You’re saying I’m not playing fair?” Harvey echoed dumbly before he could even think about it. How dare he. “Huh. But according to your standards, a bunch of guys chasing around one girl is fair?”

“Wha…?! D-don’t tell me that was your girlfriend?!”

Trying to take a step backward, Two tripped over One where he lay in the fetal position, cradling his hand, and landed gracelessly on his ass. One let out a sob.

The landing deposited Two in front of Three in the puddle of blood. Three’s consciousness seemed as if it was already fading; his body was being racked with jerky spasms. Advancing half a step toward Two, Harvey gestured briefly toward Three with his eye.

“That guy’s done for if someone doesn’t stop the bleeding soon. Not that it matters, since I’m gonna kill all of you.”

He figured that was fair warning, for what it was worth. Two shrieked, pale-faced, and scrambled away without even trying to stand up. He just scooted backward on his rear, feeling his way with his hands behind his back.

“Hey, man, we just teased her a little, we didn’t do anything…C-come on, calm down, okay?”

“I am calm. It’s almost funny how calm I am, really. Heh, it kinda makes me laugh.”

“Th-there’s something seriously wrong with you!”

“Really?…I think I’m just being normal.”

He looked down at the folding knife in his hand and adjusted his grip a few times experimentally. He’d only been carrying it around before; today was the first time he’d ever tested how it felt to use. Already it felt comfortable and right, fitting his hand perfectly. And it had been a long time since he’d really gripped a knife, but now that his feel for it was starting to come back, it actually felt pretty nice.

“Huh…I like this thing.”

A thin smile rose to his lips unbidden.

Two gave a shrill hiccup and bolted, practically on all fours still. He promptly tripped over Three’s prone body and fell again. Dragging his fallen friend up with him, he choked out to One, “H-hey, run—!” before starting to run himself. “Wait! Wait, damn it!” One hurriedly caught up to him, and they braced the incapacitated Three between them as they scurried off in same the direction they’d come from.

Well, look at that.

They’d actually taken their friend with them when they ran. Harvey was rather impressed. He decided to give them a five-second head start as a reward. 5, 4, 3—Eh, that was about two seconds short, but good enough. He regripped his knife and started to dash after the running men, when just then he saw a shadowy figure standing in front of them. “H-help us!” they cried pathetically, circling behind the newcomer as if he were their last hope. The bravado was completely gone from their voices (Great, now I look like the bad guy). As soon as they got a good look at the newcomer’s face under the gas streetlamp, however, those voices and attitudes did an abrupt 180.

“Why, you—”

Before Two had the chance to finish, the new arrival had already slammed an elbow into his face. For a split second Harvey remembered that Two was the one whose nose had been covered with gauze, but he didn’t feel any particular sympathy; it was forgotten again as soon as the memory formed.

“Joachim!”

Without slowing down his dash, Harvey switched targets and went after the newcomer.

The heavy sensation of piercing flesh—but the scream didn’t come from his target’s throat or his own. It came from Punk Number Two. Joachim casually shoved away the arm he’d yanked in front of him and used as a shield, filching its owner’s knife while he was at it, and launched an attack at Harvey without even pausing for breath. Two crumpled to the ground, cradling his mangled forearm and sobbing about something or other, but Harvey’d lost all interest in him by that point.

Skreee—!

The shrill screech of blade hitting blade rang across the bridge in the darkness. Their eyes locked over their still-locked knives. Faces close enough to feel each other’s breath, they paused long enough to each get a word in—“Yo! What’s got you so flipped out?” “You bastard…!”—before they simultaneously took one great leap away and immediately prepared for their next attacks.

Neither of them had a real reason for trying to kill each other on sight, nor did either feel the need for one.

Looking up toward the sky, Kieli realized that the clouds had stopped moving. The intermittent booming of the cannons in the distance and the dusty wind carrying the merry whoops of the kids through the yard had both abruptly died down. It was just like that final destination of all things drifting in the Sand Ocean: a place where everything had come to a complete halt, even the flow of the air.

One corner of the bleak schoolyard beneath that overcast sky was now dotted with little gray mounds. They were tiny, misshapen grave markers: nothing but a few stones piled together.

In the center of this crude collection of tombstones she hesitated to even call a graveyard, a young redheaded boy crouched piling up rocks bigger than his own fist, one by one. His silent back seemed to be warning her off even offering to help, so Kieli couldn’t do anything but stand still and quiet behind him, watching him work.

Snik. Snik. Snik.

For some time, only the dry sound of stone striking stone echoed emptily in the sky.

When a pretty stone meant to be the top of the last mound was laid down and they were all finished, little Elisha materialized above the grave. Her eyes wandered over her surroundings for a while, empty and expressionless, but when they focused on Ephraim’s face where he squatted in front of her, she smiled just a little, looking happy.

“Thanks for always making the graves, Effy.”

His drooped shoulders twitched as if he was holding something in, and Kieli’s heart hurt just watching him.

Without answering Elisha, Ephraim stood up in front of the grave and retreated to stand a little ways away. From that spot extended three sides of a square, marked out with mounds of stones—a makeshift graveyard holding not even ten people.

“He’s done!”

At the call of Elisha’s childlike voice, the other kids appeared out of the nothingness one by one to sit on top of their respective graves, knees drawn up to their chests. All of a sudden Joachim was standing next to Elisha, though Kieli hadn’t seen him arrive, and they’d naturally fallen into the same lineup as their seating order in the lunchroom.

“Today was no good either, huh?”

“It just never goes right.”

“And I even wrote a warning on the board, too!”

“I guess you have to write it so it’s easier to get.”

“Even if we make it easy to get, there’s no way anybody will get it.”

“I wonder how come we can never remember it when it’s happening, even though we can remember everything once it’s over?”

“Tomorrow we’ll forget everything again and start all over, huh?”

“I wonder if somebody will catch on tomorrow…”

And so they went around the ring of children, with each one making a comment.

Kieli had started to understand a bit about their circumstances after that stray artillery fire had landed in the schoolyard. This school was endlessly reliving a certain day from its past—she’d met a few spirits before who’d gotten trapped in time loops. The presence of a foreign element that shouldn’t exist in that loop, namely Kieli herself, had caused things to follow a slightly different course today, but in the end the results hadn’t changed.

If she’d done just a little more, taken some kind of positive action, could she have saved everyone? Or in the end, would something that’d happened so far in the past never change, no matter what she did?

“Okay, guys, see you tomorrow.”

“See you tomorrow.”

“Bye-bye, Ephraim. Bye-bye, Joachim.”

Their brief meeting over, the children vanished one or two at a time, fading into the sky’s thin, low-hanging clouds. “Bye-bye!” Elisha, the first to appear, was the last to vanish. Then all the younger children were gone, leaving behind only the meager graves they rested beneath.

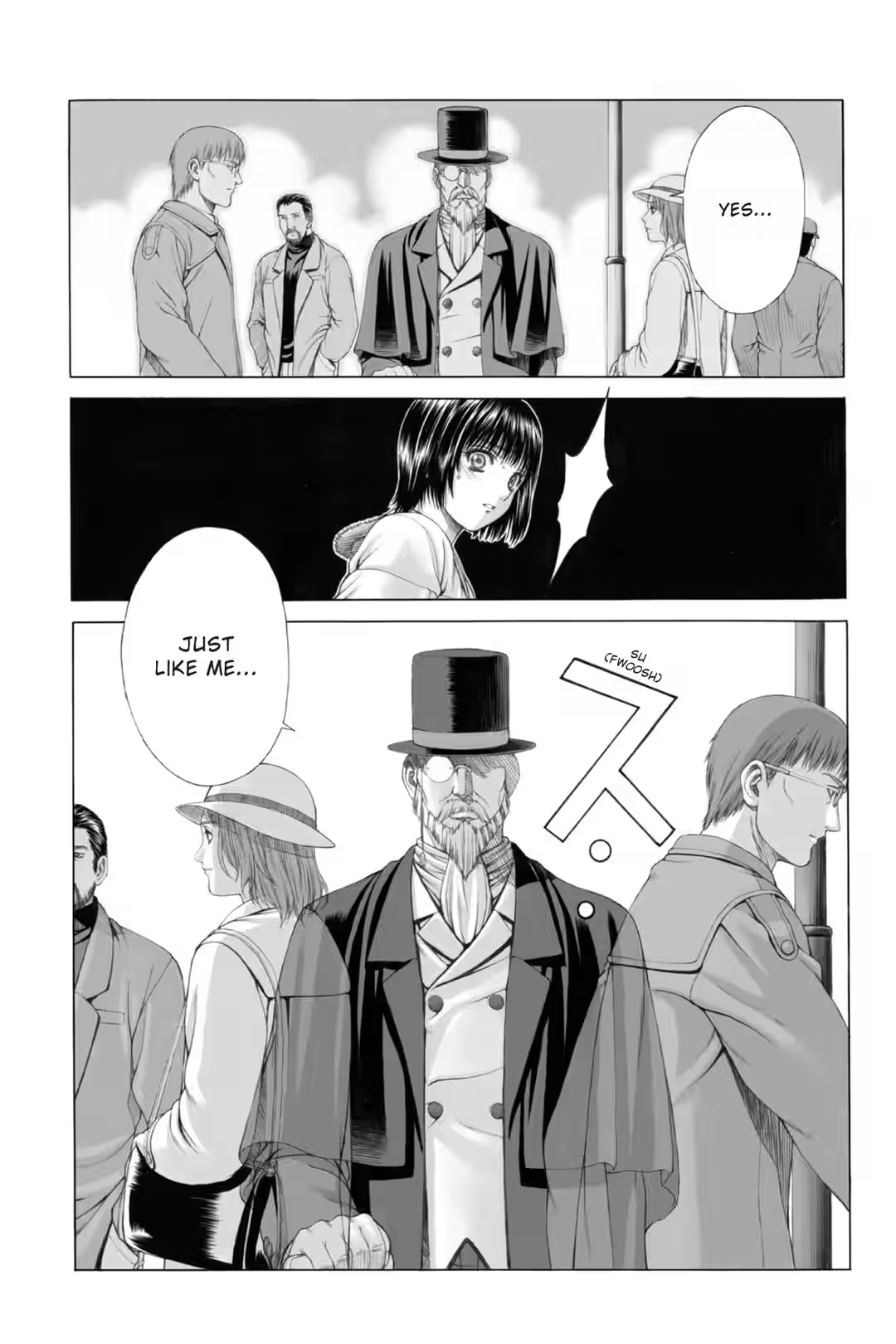

Ephraim and Joachim alone were left, the two oldest students, facing each other diagonally just as they had in the lunchroom. But neither tried to meet the other’s eyes. They stood for a while staring at the ground in stony silence.

Finally Joachim parted his lips from their bitter, tightly pressed line and muttered in a strained voice, “…It came so close to going right today. If we just catch on a little faster…If we do it again tomorrow, maybe it’ll go right this time.”

“It’ll be the same tomorrow.”

Ephraim’s answer was even flatter and more emotionless than usual.

“No matter how many times we redo this, nothing will ever change. It won’t bring the runts back to life. We’re just wasting our time.”

“You bastard!” Joachim cried furiously, and then almost before Kieli could blink, he was springing forward and launching himself at Ephraim. They tumbled to the ground in a pile of limbs and kept rolling through the low cloud of dust they kicked up, starting up a real scuffle somewhere along the way.

“Why do you always, always give up right away like that?!”

“Quit yelling about it; you’re being a pain in the ass! You know it’s the truth, and anyway we’re all long dead by now!”

“This is what pisses me off about you, the way you act like you’re better than me ’cause you’re so calm and rational!”

“What’s that got to do with it?!”

Joachim straddled Ephraim and punched him in the face, and Ephraim, not to be outdone, kicked Joachim in the stomach from below. “Stop it! Stop it, you can’t do that!” Kieli had just been watching from the sidelines up until now, but she surely couldn’t sit back and watch this. She jumped forward and dove between the two boys, peeling them apart. They still both seemed determined to get their hands on each other, so she raised her voice. “I said stop it! Cut it out right n—!”