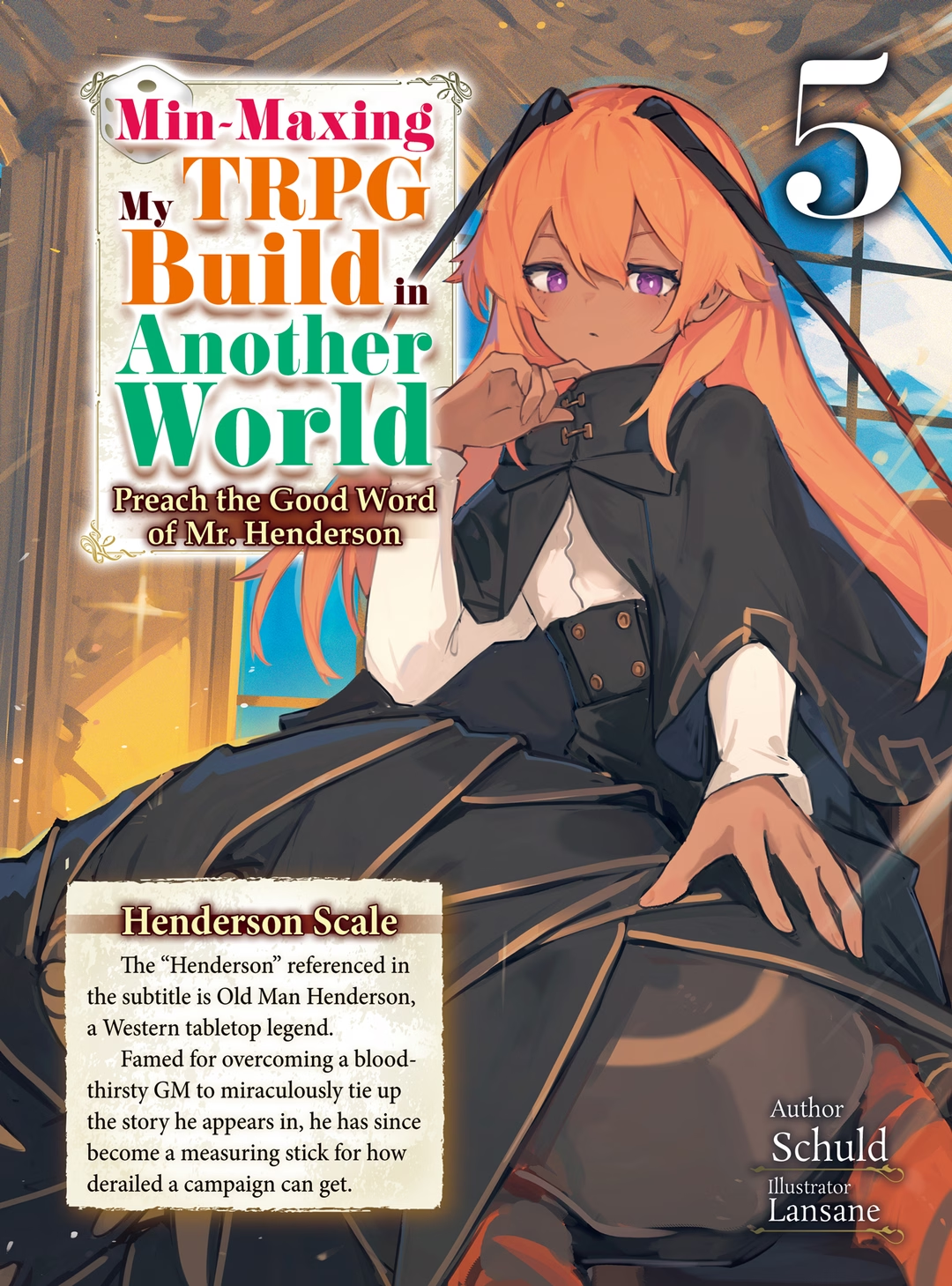

Preface

Tabletop Role-Playing Game (TRPG)

An analog version of the RPG format utilizing paper rule books and dice.

A form of performance art where the GM (Game Master) and players carve out the details of a story from an initial outline.

The PCs (Player Characters) are born from the details on their character sheets. Each player lives through their PC as they overcome the GM’s trials to reach the final ending.

Nowadays, there are countless types of TRPGs, spanning genres that include fantasy, sci-fi, horror, modern chuanqi, shooters, postapocalyptic, and even niche settings such as those based on idols or maids.

Reality tore open. The hole occupied only the bare minimum amount of space, perhaps betraying the fatigue of its creator; it simply hovered above a well-worn hammock in a laboratory belonging to none other than the first heiress to the Stahl barony, Agrippina du Stahl.

The woman herself came slithering through the tear and directly into bed.

“Oh, I’m tired... So tired... What a colossal waste of time...”

The groaning noblewoman had appeared from the shaky portal with all the energy of half-finished pudding: it would fit best to say that she had been excreted out of it. Her tone carried so much palpable fatigue that every word threatened to lift her soul away with it. For someone who avoided social merriment and career advancement alike, her faculty-mandated torture session had been agonizing enough to draw her true feelings into the realm of speech.

Methuselah boasted enough strengths to earn their title as the peak of all humanfolk, to be sure. Their unmatched internals allowed them to forgo food and sleep, and let those who partook in the occasional meal or drink get away without cycling it back out. Making full use of their physical gifts meant that a methuselah was perfectly capable of engaging in high-level debate on magical theory for seasons at a time, much like Agrippina had done.

Alas, the gap between survival and comfort was as profound as it was profoundly callous.

Agrippina liked to sleep several times a week to refresh herself, and even dabbled in the sensory amusement of cuisine when it suited her. Most of all, she loved the luxury of lazily swinging her legs in her hammock.

Unfortunately, her conversational partner had been Duke Martin Werner von Erstreich—he was technically also a great duke, but his continued leadership of House Erstreich made him a duke as well—and the man was the sort of immortal who would happily renounce food and sleep in their entirety for the sake of his research. For a woman whose pastimes consisted of sloth and indolence, he was nothing short of her polar opposite.

Their meeting had illustrated the difference in their priorities perfectly: the scoundrel considered magecraft as a means to further her interests, whereas the duke took it as his interest proper.

For as antisocial and lazy as Agrippina was, she was not stupid enough to allow her lethargy to cause her own ruin. Though her discussion with Duke Martin on the technical details of the aeroship had run on much too long, she hadn’t dared to do him the dishonor of asking for a break or to leave.

Authority was everything in a monarchy. When a sour mood could reduce someone’s life to less than a scrap of paper, interrupting a superior’s amusement was next to unthinkable; doubly so when the man in question had once reigned as Emperor, and remained one of the College’s untouchables to this day.

Had they been in her motherland, Agrippina could have held her own as the first princess to one of the Kingdom’s most influential families; yet in the Empire, she was no more than a foreign researcher of incidental noble birth. No matter how prestigious her background was, it meant nothing in the face of someone whose clout overshadowed her own.

Thus she had held out until this very moment, where she could finally dive into the hammock she had so dearly longed for. The pure joy she felt was nothing short of that felt by a lone vagabond returning home after wandering unwelcome for decades.

“Ahh... My beloved laboratory... I shan’t so much as step foot outside you ever again...or at least, for the next ten years.”

Agrippina’s every remark only served to sully the beautiful dress she’d been given for the aeroship showcase, not to mention how happily she rubbed her face into her soft bedding. Yet even as her brain melted into euphoria, a fleck of lucidity in the back of her mind noticed something was off.

Peeking up with one eye, she surveyed the room. A normal person would have seen only the shining rays of spring sun and been content to say this was closer to a greenhouse meant for tea parties than a magus’s atelier. However, the myriad of invisible lookout spells told a different story.

Every personal lab in the College came with a handful of simple defensive systems already installed. Naturally, Agrippina had torn them all out—there wasn’t a single researcher that left them in place—and replaced them with not ten, not twenty, but eighty-seven different barriers that protected her territory from threats both magical and physical.

The methuselah could see them all, and she noticed something strange.

The only traces of entry present in her laboratory belonged to her servant, who had dutifully kept the place tidy, and her student, who had come in to fetch her homework...but that only covered the laboratory proper.

Exhaling a spell woven into her breath, Agrippina dragged out the records of those who had passed through one of her many wards. She looked over the archive written in light that glowed only for her; after sorting out those who were expected to come and go, she found that two people had been let into her drawing room.

The first was a friend of her manservant, Erich of Konigstuhl. She recalled having met them once following the gut-bustingly hilarious tome-purchasing episode: they were a College student who had cast their lot with the gloomy hermits.

This was, well, fine. Had the boy brought over a professor belonging to another cadre without hesitation, he would be due for much worse than a spanking, but the methuselah felt like she may or may not have given him permission to invite his friends into the parlor, at least. She could have put in the effort to remember the exact date and time at which she’d said that, of course, but this memory was serviceable enough as was.

No, the problem lay with the other guest. Though Agrippina was unacquainted with whom it represented, the family name dancing along at the end was very familiar—troublingly so.

The spell that had recorded the entrants was one that exposed their true names unless they explicitly took steps to hide them. Furthermore, this wasn’t something flimsy enough to be prevented by an average counterspell or miracle; the formula belonged to Agrippina’s father, whose influence invited proportionate animosity. Its readings were certain: after all, even the woman who’d cast the spell had taken 130 years to find an answer to it.

This was psychosorcery that scanned the soul for what it considered its true name. Leaving aside the fact that the caster had waded shoulder-deep in the swamp of forbidden magicks to set up an approximation of a lock, Agrippina had to read and reread the name over and over again to make sure she was sane.

“Constance Cecilia Valeria Katrine von Erstreich... What?”

Alas, no matter how many times she looked the name over, it never changed. It was no fake: a foolish imitator who considered themselves an Erstreich for enough time to believe their fiction at the very crux of their being would not be allowed to draw breath for long.

“What has he done?”

Come to think of it, the warning signs had been there. Duke Martin had practically imprisoned her in a single room for months, and she’d sensed people coming to the door on many occasions. Then, at the important showcase, he’d suddenly vanished.

Agrippina had noticed the Emperor’s lividity under his guise of normalcy, suggesting that the duke’s disappearance had not been planned. In fact, the only reason she was here in her room to begin with was because the man had skipped out on his promise to show her around the ship following the terrace banquet.

Some unforeseen emergency must have occurred, and her servant and the girl he’d invited were the cause.

Hauling her dreary body out of bed, Agrippina plodded along to the drawing room. With every step, she cast aside ornaments that could buy common families whole, stripping off her pinching boots and untying her heavy hair to make herself comfortable. By the time she reached the parlor, she’d torn off her tight nightgown to shamelessly lay her body bare.

The room proved its keeper’s commitment to orderliness; without prior knowledge that someone had entered, she would have been none the wiser. Both the low coffee table and the sofa were immaculately kept by her exemplary servant.

Whereas a detective would struggle to find damning evidence, the magus only grew more certain. Divinations like this were at their most precise when physically at the site of the search, and she didn’t need to find a loose strand of hair to be sure that someone had made an extended stay in this room.

“Oh? What’s this?”

Agrippina came across a wineglass in the corner of the room, seemingly forgotten by her dependable housekeeper. Though it looked like any other chalice, she immediately brought it up to her nose to smell the faint scent left behind.

“Blood,” she murmured. “I’m beginning to see the full picture.”

Duke Martin had hurried off despite his important role at the banquet, his kin had then appeared in this room for mysterious reasons, and Erich was unresponsive to her telepathic messages. The boy was the kind of model lackey to reply even in the dead of night, and there were only two times he failed to respond after a successfully transmitted thought: when he was too exhausted for telepathy to wake him, or when he was backed into a corner and couldn’t spare any focus.

As vast as the Empire was, few in it could kill that monster as he was now. An average College researcher would struggle to flee unless they specialized in combat; if Erich chose to run away, then even fewer could catch him.

There was only one conclusion: he was caught up in some ridiculous nonsense that had nearly gotten him killed again.

Truly, could she ask for a more entertaining servant?

“Well,” Agrippina said, “it at least is apparent that he wasn’t fooling around with some boring girl. Perhaps I shall forgive him.”

That said, she couldn’t wait to see how he’d try to worm his way out of this one.

Pleased to discover that she was not alone in her fatigue, the lady put the parlor behind her, ready to enjoy a nice bath and a good sleep.

[Tips] Spells that probe into people’s souls are terrifyingly accurate, and some can expose a target’s name or appearance with frightening detail.

Late Spring of the Thirteenth Year

Reporting Quests

Adventurers are nomadic entrepreneurs. As such, they must bear the responsibility of reporting their results to whoever hired them, even if that news is painful to deliver.

I’d mentioned that the world wasn’t lenient enough for everything to end happily ever after back when we’d been brainstorming ways of saving Miss Celia, and my claim was valid. We humans were fated to clean up after the messes we’d made—personally, faithfully, and in a way that would appease whomever owned the property the mess was made on.

“So, what sort of charming little excuse have you brought for me?”

After finishing the game of ehrengarde with Miss Celia in her midnight greenhouse, Mika and Elisa had come to liven up the party. We’d all enjoyed tea for a bit and gone our separate ways—save for Mika, who’d caught Lady Franziska’s eye and gotten whisked away—but upon carrying my sister home, I was faced with cruel reality: our master had returned before we knew it.

Don’t get me wrong. I’d known that this woman had some means of telling who intruded on her territory. Rather, I would have been worried if she didn’t. My employer was exceptional even among her immortal peers; I would sooner expect lightning to arc across blue skies than to see her feeling under the weather.

And so, after tucking in Elisa—my safe return had gotten her so worked up that she’d fallen asleep by the time we’d left the Bernkastel estate—our master’s first words to me following her own safe return were as previously mentioned.

“First and foremost,” I said with the most deferential expression I could muster, “I must celebrate this occasion from the bottom of my heart. I am overjoyed to see that you have returned unharmed.”

Spewing the most servile thing I could think of, I knelt before the couch she was laying on. I was prepared to submit myself to her whims.

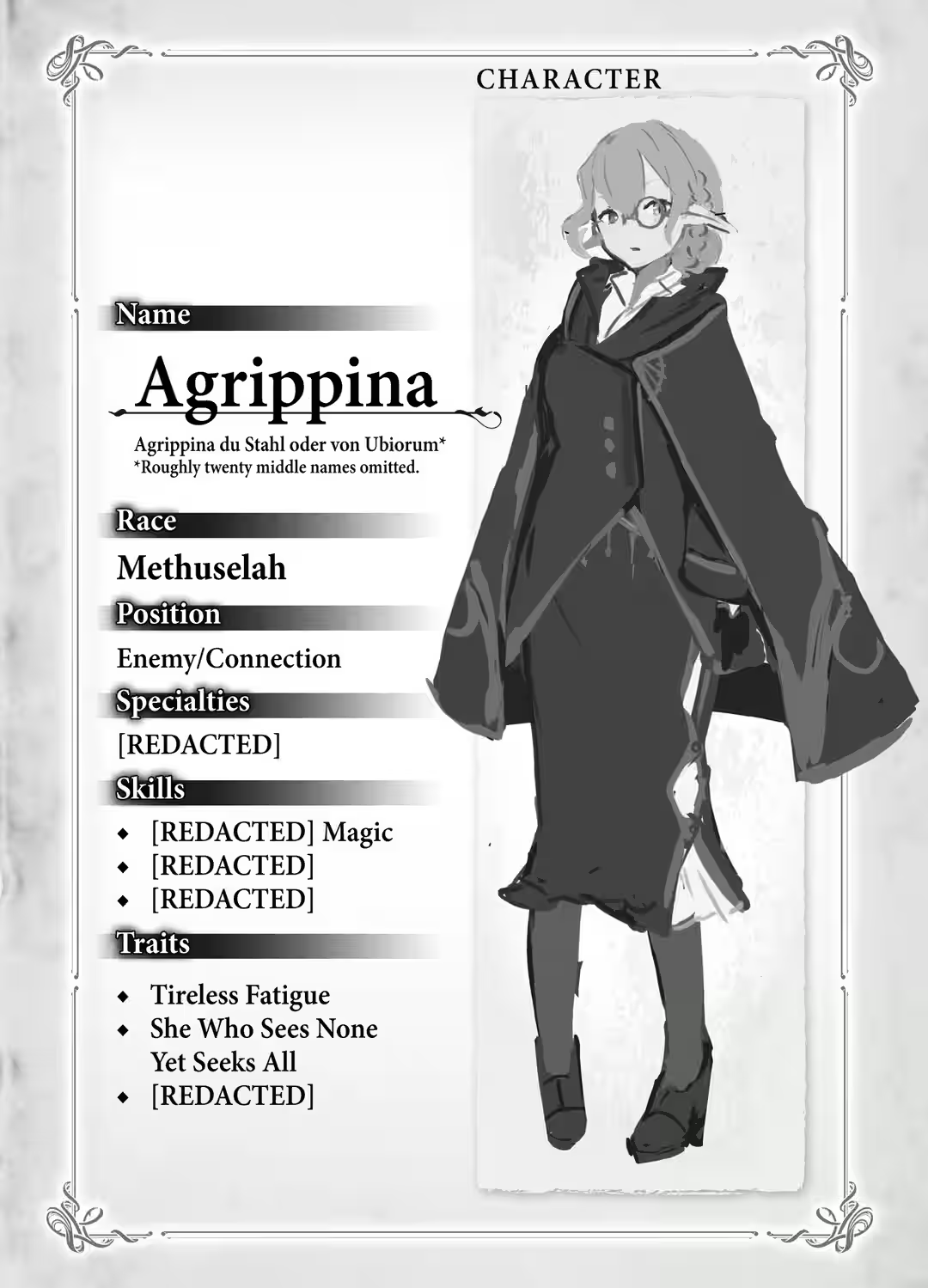

Frankly, I had no delusions of trying to fool Lady Agrippina. She was the kind of playful—nay, mocking enemy found in the back of advanced rule books, whose existence was a challenge to the player: fight her if you dare. What was the point in trying to hide information from a monster that could bring down a full party of maxed-out PCs? If she felt like it, she could strip my soul bare with psychosorcery; an honest apology was a much, much better choice than lying.

“You have my deepest apologies for allowing guests in without your permission, be it only into the parlor as it was. This decision was mine and mine alone, and I am prepared to bear responsibility for it.”

“Oh, my loyal servant. It pleases me to see that you understand your own transgressions. After all, they say a retainer who cannot sense their master’s anger is fated to a short life.”

H-Holy shit. This was why the upper class were so scary: they could mull over the lives and deaths of us peasants as if it were chitchat, sporting the same thin smile and easy tone of voice as usual.

That said, I wasn’t a blithering enough idiot to show up without preparing an excuse—one good enough to convince the likes of the madam, at that. I told her the full story without any omissions or exaggerations: everything from how I met Miss Celia to how we’d helped her escape; the battle from last night; and my meeting and subsequent acquaintance with Lady Franziska.

Lady Agrippina listened to my tale in silence—laughter did not count—until I was completely finished. I couldn’t see what part of my misfortune was so amusing as to leave her gripping her sides in pain, but after I’d retold everything, she simply said, “I shall put it on your tab.”

“...What?”

“I’m saying that I shall let you off with the small debt of a single favor.”

Wiping a single tear from her eye, the madam named a price several times more frightening than a mere fine. Was I crazy, or was handing this woman a blank contract basically the same thing as suicide?

Wait, no. At least with suicide I’d get to die a peaceful death... Still, I supposed this was a better fate than someone of my standing could have realistically hoped for.

“A...favor?”

“Your account was entertaining, and it appears as though everything has been tied up nicely, so I don’t mind. I was able to confirm that you have some sense of your place, as well.”

“Is that truly acceptable?”

“The question of whether it’s acceptable or not is mired in all manner of issues, but consider this: had you handed that girl in, the situation would only have worsened. The grudge of a noble scorned is quite something.”

To tell the truth, I had planned on using that as another excuse. While Miss Celia wasn’t the type to obsess about revenge, there had been a chance that her pursuers were bandits merely masquerading as noble retainers. If I’d let her slip into their hands, who knew what her parents would do to me? Or even if they truly did belong to her house, it was possible that she’d resent me for foiling her getaway and exact vengeance on me after marrying—or so the justification went.

The real Miss Celia was a saint in all but name; I was sure such dark thoughts never even crossed her mind. Still, an enraged aristocrat was more than capable of fashioning guilt for a lower-class enemy to don.

“I should think this conclusion as clean as they come,” Lady Agrippina said. “Though I suppose you did nearly die again.”

“...Yes, well, I’d rather not experience my limbs flying off ever again.”

“I’m sure. They don’t grow back and are challenging to replace, so take care of them, will you?”

I don’t need to hear that from you—I know plenty well they don’t grow back. I was acutely aware that my irreplaceable arms and legs were only with me thanks to Miss Celia.

But come to think of it, who had that guy been, anyway? Lady Franziska had said not to worry because she’d administered him a “healthy dose of discipline,” but that mage had at least been on the level of a College professor. Trying to figure out why he’d been waiting for me—and trying to look cool doing it—confounded me to no end.

He’d appeared with all the pomp and circumstance of an unprepared GM rolling dice to figure out what kind of boss to place at the end of a mission. There was a palpable malice in his placement, as if I’d dodged the true final boss and forced the world to place an unavoidable encounter on my escape route to make sure the climax didn’t fizzle out. I’d seen this sort of thing before: once, my old crew and I had tried to pilfer the precious gems out of some ruin and were on the verge of escaping without incident when we randomly “discovered” that the pillars holding the place up had been crystal golems all along.

Judging from his demeanor, I could tell that the masked nobleman had been toying with me, but not much else. Seriously, why had that broken enemy just been waiting there?

“With that said,” Lady Agrippina went on, “strip.”

“Huh?”

“I said strip.”

Yes, ma’am.

Though her order came out of nowhere, I couldn’t talk back if she was going to insist. He who has wronged was ever at the mercy of she who has been wronged.

I took off the shirt I’d been given at the Bernkastel estate, and the madam stopped me, saying that my upper half would do. She then began to ogle with an unhidden gaze.

Personally, I found my young build lacking and frail, despite my developing muscles. My shoulders were beginning to gain definition, my limbs had started to grow stronger, and I’d long since left my childish potbelly behind; yet I was still far from the virile physique I was so enamored with.

More to the point, though, I’d already checked in the mirror to confirm that my detached arm and legs bore no trace of their gruesome injuries. Not only that, but my run-in with the crank of high rank had seen me tumbling this way and that; my “Daisy Blossom” spell alone had blasted me straight into a pillar. I should’ve looked mushier than a bruised banana, and yet I couldn’t find so much as a scab.

“Hmm...”

However, Lady Agrippina could see what I could not. Her gaze ran down an invisible line where my flesh had once parted. Even when I really put my mind to it, I couldn’t detect any lingering evidence of how reality had been warped; this was yet another example of how much more capable her eyes were.

Gods, it’s so tempting. If I could see the world as well as her, the edge I’d gain in arcane combat would be unquestionable. But a mystic swordsman couldn’t afford to divert points away from physical attributes; I didn’t want to spread myself too thin and end up being lousy at everything.

“The gods certainly do work miracles,” the madam mused. “Not even those flesh-crazed cultists of Setting Sun could graft skin this naturally. From a thaumaturgical standpoint, it is nearly as if your arm had never been severed at all.”

“I didn’t realize it was that impressive.”

“Nerves, arteries, bones and the marrow in them—human bodies are more than mere clay. One can cultivate replacement skins all day, but effort cannot replicate healing this perfect. I can see why those poor maniacs eye the faithful with such envy.”

Gently, Lady Agrippina’s finger reached out and traced the absent scar. Even though she caught me off guard, I remained totally sound of mind. Despite having already experienced a rather embarrassing accident during my trip to Wustrow, I had at least yet to let my preferences drift too far from reputability. Something instinctual in my soul whispered to my body: This one’s a no-go. Despite all the trouble my teen body had been causing me recently, I figured it deserved a bit of praise for its prudence here.

“Ahh, but there is residue of the magical variety: a spell that misaligns bits of space to render anything occupying it into mincemeat. How vulgar. An attack of this sort scoffs at the very notion of evasion and defense... Standard conceptual barriers would shatter instantly. What sort of depraved life must you live to come up with a means to turn mere embodiment into a weakness?”

Amazingly, Lady Agrippina managed to see through the true nature of the formula off the faintest leftover mana clinging to my wound. As impressive as her depth of knowledge was, I was too busy trembling at having been the target of the attack to marvel.

I’d been lucky to only have three limbs twisted off. If what she was saying was true, I should’ve been a reorganized mess of meat; the spell was like crumpling up a piece of paper to crush the stickman drawn on it.

“Mm, I’ve gotten the gist. I’ve memorized this mana signature; that will be enough.”

“What? Are you planning on looking into the person who attacked me?”

“Indeed. Though it isn’t as if I intend to avenge you or anything.”

“I know that much...”

“Call it a personal curiosity. Feel free to make yourself decent.”

A sweet fragrance wafted my way as I put my clothes back on: finished with a quick chore, the madam had decided it was time for a smoke break. I carefully tried to slip my neck through my shirt without letting my hair get caught, but just as I did, a cold voice cut through the cloth to sting my ears.

“It is a stroke of fortune that you’re alive...but I will not tolerate a second ‘all’s well that ends well, happily ever after.’”

The usual play in her tone was gone, and her reproach was not followed by a lighthearted confirmation; this was a warning in the truest sense. I jammed my head through my collar, hair be damned, and quickly got back on my knees.

“I am well aware.”

“Mm, very well. Anyhow, I shall be charging your patron from now on whenever money is involved, so make sure to see through the preparations on that end.”

“As you will.”

“I’m sure you’re very tired, so you may leave for today. Resume your duties tomorrow morning.”

Anger was most terrifying when it came from an ordinarily freehanded master; a happily ever after truly was too much to ask for. Though I didn’t regret my decision, this adventure of mine had come with a steep debt...

[Tips] Arcane limb replacement is an imperfect craft. Newly generated flesh is sure to differ in skin tone at minimum, and requires long hours of rehabilitation to reconnect and retrain the nervous system.

Meanwhile, the faithful cast miracles that outperform these mystic surgeries off the back of spiritualism alone. The magia who dedicate themselves to the arduous pursuit of knowledge often look at priests and the like with unjustified envy and anger.

Whether I was dying or Miss Celia was running for her life, the capital chugged along all the same. The only notable difference tonight was that there were far fewer guards walking the streets. Now that the chaos had subsided—I didn’t want to imagine what had gone on behind the scenes—there wasn’t much point in keeping watch at every corner, so I guessed it was inevitable.

Looking back, I felt awful about how I’d treated the dependable guardians of our city. My back had been against the wall, and I hadn’t been able to hold back as much as I would’ve liked; a fair number of them must have suffered broken bones. The crown offered good benefits, so they wouldn’t struggle to find treatment or get paid leave, but worsening their daily lives came with pangs of guilt.

Gingerly knocking someone out in one hit like some comic-book hero was an exacting task, but maybe that was just my own lack of skill talking. Unfortunately, people were too complex to go down after a single punch to the gut or neck, and smacking their heads was a shortcut to sustained injuries; strangulation didn’t keep people down long enough, so that wasn’t an option either. I could only ask that they lay the blame on my spineless performance and Miss Celia’s immature father—preferably at a one-to-nine ratio.

Speaking of benefits, I’d nearly forgotten. Mika and I had met up at the Bernkastel manor, where we’d celebrated our mutual safe returns and I’d honored her courageous devotion, but I had yet to recognize two of the most important contributors to our cause.

“Ursula, Lottie.”

I whispered too quietly for anyone else to hear, but clearly enunciated their names. A cool and refreshing breeze rolled by, sweeping away the lukewarm night.

Yet as the current faded, it left behind two gifts on my head. I didn’t need to look up; the alfar who had helped Miss Celia escape and whose valiant efforts indirectly saved my life were here.

They’d gone above and beyond for me. Had Miss Celia stowed away to Lipzi instead of calling for her aunt, I would have traded lives with that lunatic in the sewers at best. In the worst case, I could have missed my final shot and been reduced to chum without so much as avenging myself.

And of course, the young lady’s aeronautical adventure wouldn’t have succeeded without Ursula and Lottie’s help. The thing was a top imperial secret that would determine the political, economic, and military future of the nation: a posh girl oblivious to scouting methods was sure to be caught by security immediately without the help of these high-ranking fairies.

Alfar were so profoundly intimidating. If they could be bound to any sort of rhyme or reason instead of committing themselves to whimsy, I could see an entire new school of thought emerging amongst magia, dedicated to forging spells with fey assistance...though it was their unpredictability that made them fey in the first place.

“Here, Beloved One. Aren’t you a tad late with your summons?”

“Wah... I’m tiiired...”

Their voices were downcast enough to make it clear Lottie’s grumbling was founded in something real. I wonder if something happened to them.

“We received quite the earful, you see.”

“Ughhh, we got yelled at for helping too much...”

Apparently, some of the most important alfar had scolded them with scathing intensity. While I’d known that the kings and queens of the fey realm were closer to spirits and gods than the rabble, I wouldn’t have imagined that they’d be the ones directly rebuking these two.

Alfar were supposed to be aware of their own boundaries, keeping their meddling within reason. The two of them had answered my ambiguous request for them to help Miss Celia with enough effort to get them lectured.

...I guess they deserved a proper reward. They were my saviors, after all.

“Thank you both—I mean it. Is there anything I can do to repay you?”

“In that case, look over there.”

Ursula leaned over the edge of my head, and I followed her outstretched finger to see a small clearing. It was an empty area meant to contain fires, just like the one Mika had been waiting in on the day of the parade.

“What say you to a dance? I’m afraid I won’t be able to keep you to myself if I take you to the hill.”

“Sure, let’s dance.”

I made my way over to the square, and another breeze came to whisk away one of the weights on my crown. In its place, the beautiful, full-sized girl I’d first met all those nights ago appeared to greet me.

Her skin glimmered like deep honey under the moonlight, hidden only by overflowing currents of silver that blended into the orphic luminescence. Where the sterling river parted, the wings of a moon moth fluttered, blinking with otherworldly charm.

“Will you please take the lead?” she asked.

“Of course,” I answered.

Captivating, enchanting, and resolute, her vermilion eyes drooped into a smile.

Taking her small, graceful hand in mine, we began to dance. Ours was not a ballroom waltz in measured time, but the free movements of a rustic country swing; we spun around and around, drawing close and stepping away as it struck our fancy. As I twirled the same way I had during the festivals back in Konigstuhl, the svartalf elegantly moved to match.

We gently spun, then hugged and spun back, alternating steps as we faced one another. Locking our arms together, we used each other’s legs as axes to swing around and around. While I had to be careful not to drop Lottie—she was still busy pondering what she wanted—I merrily sustained the dance until beads of sweat began to form on my skin.

Seeing her alluring skin take on a faint blush in this festive mood made me understand the feelings of those who gave into temptation and were spirited away to the everlasting hill of twilight. Even though I wouldn’t go myself, I could tell it was surely a jolly place, free from any suffering. Had I lacked my promise with Margit, my duty to Elisa, or my family, maybe I wouldn’t have thought it such a terrible fate.

“That was wonderful.”

“Yeah, it sure was,” I said. “But man, I didn’t think I’d sweat like this considering how much training I do.”

We’d spent a whopping half hour dancing, and it was only now that I realized I was toeing a dangerous line. If others could see Ursula, then I was going to become an urban legend about some crazy kid dancing with alfar; if not, then I was just a lunatic dancing alone. Either way, an onlooker would call for the guards if they spotted me. While we’d thankfully managed to enjoy our dance without anyone bothering us, that was a bit careless of me.

“A boy’s sweat is a sacred thing,” Ursula said. Then, turning to Lottie, she said, “And what about you? I’ve had my fun, but how long are you going to think about this?”

“Um, ummm... Oh, oh! There’s a lot I want, but I’d like one locky, please!”

“Of my hair?”

I tilted my head, confused as to why she’d want that. But apparently, a blond child’s hair was literally worth its weight in gold amongst fairies.

“Oh, ohh!” Ursula shouted. “No fair! I should’ve chosen that too!”

“No!” Lottie shouted back. “You already got a dancy, Ursula! The locky is Lottie’s!”

“This isn’t fair! You would be dried jerky in that cage by now if it weren’t for me!”

“Nuh-uh! Would not! Lottie was napping!”

Ignoring their yapping back and forth, I untied my hair and cut off a small portion to bundle up for her. Long ago, imperial citizens used to weave decorative cords out of their hair, but modern spinning technology meant that only the poorest still did. I had no idea what she was going to use this for.

“Wow! Pretty! Thanks, Lovey One!” Smaller than the bundle of hair she was squeezing, Lottie happily twirled around while humming, “What oh what should I use it for?”

On the other hand, the fairy of the night was glaring at her friend with murderous envy... This was one of those episodes that would evolve into a grudge later, wasn’t it?

“Okay, okay, fine. Ursula, you can have one too, and Lottie gets a dance.”

“Huh? Are you sure? I mean, I’d be happy to accept if you’re willing.”

“Really?! I get a locky and a dancy?! Yay!”

For me, seeing someone’s mood sour before my eyes was much more taxing and bothersome than doing a bit of extra work. Besides, cutting off a bit of hair and dancing was nothing compared to what they’d done for me. Even if my actions bore more meaning than I knew, even if I was paying a hefty price that I couldn’t yet see, I thought I had a responsibility to repay them for saving my life.

I lopped off another tuft of hair, which pleased Ursula greatly. Then Lottie took my outstretched hand—still small—and invited me to dance. I think opinion may be split on whether or not ours counted as a “dance,” but she seemed content to hold on to my finger and zip around, so I figured it was fine.

“By the way, what are you going to do with that hair?”

“I wonder,” Ursula said. “What will I do with it? A necklace or hairpiece would be lovely, but I’d adore a ring or anklet too.”

“Lottie’s gonna ask for clothes!”

Accessories and clothing? Did alfar have the ability to process human hair into cloth? They sounded like a certain nomadic horse-riding people on the surface, which did not help make them less scary.

Regardless, I was just happy that they were happy. But while I could swing a sword for hours on end, my legs and hips were incredibly sore from just a bit of dancing. Maybe it was because I wasn’t used to it.

With my debts repaid, I was ready to go home and get some sleep...but then noticed that Ursula’s cheery mood had vanished, and that she was staring straight at me.

“...Is there something wrong?”

“I know you’ve given us two whole rewards, but let me say one last thing.”

Two and three aren’t all that different. I nodded her along, and her expression only grew graver.

“The next time you find yourself risking your life in combat, don’t cast us away, will you?”

“Oh...”

She went there. True: had these two been with me, the fight would have gone more smoothly. I might not have even needed a last-minute rescue at all. Magecraft generally only affected targets that the caster could perceive, so Ursula’s stealth could have protected me from attacks; Lottie’s wind would have been perfect for throwing off the hounds’ noses and pushing away the bugs.

However, without their help, who knows what would’ve happened to Miss Celia?

Unable to come up with a response, I stood there in silence. Watching me, Ursula came to her own conclusions and shrank back down with a quiet giggle.

“What a helpless boy.”

And just like when they’d appeared, a passing breeze whisked the alfar away. All that was left in their wake was a sweaty fool still bumbling for the right answer.

What was I meant to do?

My mind spun trying to digest her request, but only one thing made itself certain to me: I would ask those two to help me again if something important to me was on the line. Despite knowing I risked earning their ire, I had more to protect than met the eye if I wanted to stay true to myself.

“Man...”

I retied my hair and looked up at the moon, but not even the ever-shining Goddess of Night would bless me with the answer.

[Tips] At times, fey dances can cause fatigue intense enough to kill. Yet those who try to stop find themselves unable to pull away.

The church was an insular world. Though it had links to secular life of every class, the values and hierarchies of religious orders were determined almost entirely internally; for good or ill, each was its own world.

Being collectives dedicated to the act of offering their worship to gods and spreading Their teachings to the masses, this was in many ways a necessity. The faithful lauded nobles who renounced their worldly status as honorable, and graciously welcomed priests who studied from the lower castes of society; that sufficed for them in their closed systems.

However, they were not without their share of troubles.

The Trialist Empire of Rhine revered a pantheon of gods headed by Father Sun and Mother Moon; while theologians respected all those that presided over them, devotion was a practice exclusive to a single deity.

Naturally, the various churches stood in solidarity, sharing institutional structures and ranking titles to smooth over the process of cooperation. Yet so long as the gods competed for finite worship, it was inevitable that some would be on less than stellar terms with others. The divine, in Their indefinite squabbles to extend Their reach and secure Their divinity, relied on Their followers as plausibly deniable proxies; at the same time, those very followers split themselves into competing circles—power struggles were impossible to avoid.

While a certain blond boy would have written it all off as a bunch of obnoxious fanatics quibbling over minutiae, in truth, these affairs were the backdrop of great tales ranging the spectrum of comedy and tragedy.

As things stood, one of the premier sources of strife was the matter of species. If an immortal and a mortal knocked on the gates of a monastery at the same time, it was inevitable that the latter would climb the religious ladder more quickly; the undying were almost always slower to mature both physically and spiritually.

“Allow me to thank you again, dear Abbess. I shall be in your care.”

“You have done well to come...Sister Constance.”

Stratonice of Megaera, the Head Abbess of the Great Chapel, was the premier authority on the Night Goddess’s will in all the Empire and its satellite states. Today she faced the unsolvable challenge posed by the priestess kneeling before her: a subordinate and former mentor both.

The Head Abbess was a goblin, and at thirty, she was beginning to gray. Where most of her kind cared little for faith, she was a talented devotee who’d risen to the rank of bishop; during her time at Fullbright Hill, her fervent prayers had earned her the right to grand miracles. In the years following her initial studies, she’d roamed the lands, helping the needy and teaching the ignorant—achievements that the holy Mother had amply rewarded with more miracles still. She had all but reached the peak of her craft, and yet her large, golden eyes anxiously darted to and fro.

None could blame her: when she had been a wee runt in the custody of the church, her caretaker had been none other than the kneeling Cecilia she now faced. This girl had borne witness to all of her failures as a child, and had wiped up after her mistakes in many ways, worst of all literal.

Naturally, having a living record of her embarrassing past reappear in her pocket as a nun of no station put Stratonice on edge. Of course, she loved and revered the vampire for having looked after her and for teaching her the value of worship; even to this day, most of her theological positions were perfect models of her mentor’s.

Alas, how much trouble Cecilia represented was a different story. Not only was she an imperial—the same kind that was currently preparing to shuffle possession of the throne—but she was the sort of person to shoot down any mention of promotion by citing that she had yet to come of age. At times, the vampire had even threatened to bring her family into the discussion if the church dared to raise her beyond the rank of a simple priestess. What was she if not a ticking time bomb?

Balances of power were of great importance even amongst the religious. The everlasting were not to be given ranks lightly, and doubly so when the person in question was an heiress liable to renounce the cloth for secular life. Cecilia’s advancement had been discussed among the top authorities in the church on multiple occasions, only to have been invariably shot down.

But at the same time, she was the picture-perfect embodiment of an ardent believer, complete with the trust of their Goddess to wield Her power. Regardless of the political mumbo jumbo that surrounded her, she ought to have been a pastor—the minimum title required to lead a congregation—at the very least.

Instead, Cecilia had been practically left to her own devices, free to do whatever she pleased as a lowly nun without responsibilities, much to the horror of her pupil-cum-boss Stratonice.

“Please, won’t you call me Celia? I don’t suppose you’ve aged enough to forget our time together at Fullbright Hill, have you, Bishop Stratonice?”

“Very well...Celia. And though you may not remember, I have turned thirty this year. I cannot expect an imperishable soul like your own to grasp it, but I am well on my way into old age.”

It wasn’t as if Stratonice suspected this girl, still adorably asking to be referred to by nickname, of trying to play political games with her. If nothing else, the goblin was a woman of faith: she cared not for the prestige and distinctions she’d been bestowed with, and would have much preferred to return to the rank of a lowly priestess and set off on another pilgrimage if she could.

However, she was also conscious of her duties to the Church of the Night Goddess and all its followers. An average goblin lived roughly to forty, and she had already spent most of her time. She didn’t want to besmirch her twilight years by setting off a massive explosive. Perhaps the story would’ve been different had she been prepared to take responsibility herself, but she would be struggling to walk in another seven or eight years; leaving a catastrophe for her successor to handle didn’t sit right with her.

“Already? I can remember the day you first arrived at the monastery as if it were yesterday. Time passes so quickly.”

“What you perceive as quick rapids, I have waded through as a muddy stream.” The immortal’s profound surprise made the short-lived abbess want to sigh. “Come, let me prepare your room.”

Cecilia had come stating that her estate in the capital was an uncomfortable place, and that this opportunity to study in a place beyond the holy mountain must have been part of the Night Goddess’s will. That alone was fine. However, Stratonice could only pray that she wouldn’t bring imperial entanglements along with her, or that her unshakable piety wouldn’t cause any unforeseen problems.

The desire to treat her childhood caretaker just as well as she’d been treated clashed with the pure terror that came with stuffing a live, delicate bomb in her inner pocket. Unable to grumble in front of her mentor, the aging goblin bottled up her fears; marching through this conundrum to repay her debts as best she could was but another trial from the Goddess, or so she told herself.

“Oh, that won’t be necessary,” Cecilia said. “This bag is all I’ve brought. And I won’t be needing a personal room. Would you please lead me to the commons?”

“You never change, Celia. Would it not do to at least, say, bring along something more fitting of a girl your age? Our merciful Mother may emphasize purity in abstinence, but She does not forbid all manner of pleasure.”

“It simply isn’t for me. In fact, I recently found myself in a rather peculiar situation where I donned a so-called maidenly dress, but I quickly learned that I am best in these robes.”

The vampire’s continued extremism caused the abbess to worry. Although she was an ordained bishop, she had eight children—goblins generally gave birth to packs of three to five children at a time—and nearly fifty grandchildren; she was beginning to suspect that this immortal girl was going to spend the next eternity alone in the church.

The gods did not disapprove of marriage and childbirth; rather, They espoused it as one of the major trials in the act of worship that was life, teaching lessons about the joys and sufferings it entailed. The Harvest Goddess’s flock went so far as to consider the unwed to be fundamentally incomplete; while the followers of Night were not so extreme, a great deal of their clergy were married. When teaching a layperson, the burden of understanding ultimately fell on the learner, but those teaching their own children were responsible for their upbringing. Providing instructive compassion and love to one’s own flesh and blood was seen as the most difficult test of one’s character.

But wait, Stratonice thought. A corner of her brain bubbled up to pick out a tiny detail: the girl had said she was best in her robes, and not that her robes would do. Something must have happened to make her actively prefer them and consider them best suited for her...like, say, a compliment from a boy.

“Perhaps I spoke too soon. I suppose some things do change.”

Although the vampire looked nearly identical to when she’d last seen her, the sands of time had brought change with them, as they were wont to do. The reddish-brown skin full of wrinkles she’d inherited from her forest tribe scrunched up in a great big smile reminiscent of her childhood.

“Do you think so? I’ve stopped getting any taller of late, so I can’t help but believe my period of growth is over.”

“If I’m not mistaken, the average vampire matures after roughly a century, and slowly conforms to the appearance most comfortable to the soul, yes? You still have many years of growth ahead of you, Miss Cecilia.”

“Oh, please stop.” Cecilia frowned. “However will I carry myself if the Head Abbess refers to me so?”

“All is well if the person in charge allows it,” Stratonice said, slapping her mentor-slash-subordinate on the butt—she physically could not reach her back—and beckoning her on to a tour of the area.

The two of them visited the rooms for chores, charity, and prayer; then the abbess showed the nun the various minor temples that the masses frequented, and the schedules for service and instruction. When all was said and done, their stroll had taken quite some time.

This was an indulgent use of one’s day for someone as busy as the Head Abbess of the Great Chapel, but that meant little to a pair bound by ties as long-standing as theirs. Besides, Stratonice had blundered terribly in her dealings with the imperial heiress once before, and walking halfway around Berylin was nothing in comparison.

“How do you like the Great Chapel?” the abbess asked. “It isn’t quite as nice as Fullbright Hill, but isn’t this temple splendid?”

“Indeed. I’ve grown quite fond of it. The people of town seem much more austere and fervent in prayer than I’d imagined. I’m relieved to see that the rumors we’d heard of how callous the capital is were untrue.”

“I’m glad to hear that. Think of this as your new home and rest easy here for ten years, twenty—however long you wish.”

Giggling, Cecilia said, “Then I will take you up on that offer and relax here, devoting myself to serving the community.”

The vampire’s smile finally gave the abbess some peace of mind. Stratonice knew that the girl had been involved in some sort of incident before arriving; she didn’t know what that incident entailed, but suffice it to say that it was something major. As such, she saw no better way to repay her kindness than by preparing a sanctuary where she could unwind.

The undying were also oftentimes unmoving: once she settled in, she wouldn’t leave for another five to ten years at least. There was a real chance that Cecilia wouldn’t return to Fullbright Hill for another two or three decades. Stratonice felt blessed that she was in a position to offer and protect that sanctuary; at this rate, she would be able to rest in her final years with her mentor quietly devoting herself to further prayer.

“Oh, the bells,” Cecilia said. “My, is it that time already?”

Stratonice looked up at the darkening skies and saw the bells in every tower ringing. These tolls in particular were to notify the denizens of the capital that evening had arrived, and they marked suppertime at their own chapel. But just as she turned back to the vampire to invite her to the dining hall, Cecilia suddenly remembered a question and asked away.

“By the way, Bishop Stratonice, you spent some few years as a lay priestess, didn’t you?”

“Yes, I did indeed. During my pilgrimage, I thought it would be a good opportunity for me to tour the countryside as well, and spent three...no, four years or so out there. I tried my hand at many a miracle and advanced my clerical rank, unordained as I was. I remember the journey fondly.”

“May I ask you for any tricks you learned during the endeavor?”

Tricks? The goblin cocked her head; she was half-doubtful of the girl’s intent, and half-surprised by the unexpected question. But little did she know, the walking bomb was ready to set off an explosion of cataclysmic scale as soon as she replied, “Why do you ask?”

“I have stumbled into a century to do as I please, so after studying here for a short while, I plan to travel the lands as a lay priestess.”

Every thought in Stratonice’s mind went flying. A missile had directly struck her brain, demolishing any semblance of rational thought and sending the staff in her hand tumbling toward the floor. Her mentor reached down to pick it up with a casual, “Oh my,” but the abbess couldn’t even rouse the good sense to stop her. This one carefree proclamation had been explosive enough to shock her to her core; the relief she had felt only a moment ago had been blasted to dust.

For a moment, she considered the possibility that she was misremembering what it meant to be a lay priestess; alas, the definition had not once been changed in all the years since the Rhinian pantheon’s founding. Lay priests renounced membership from every church, leading the people of the land with nothing more than their own devotion.

This was not in the same realm as a simple pilgrimage or mission catered toward educating the masses. To cast one’s lot with the laity was to sever the final tethers to safety—it was to offer oneself whole in the name of whatever it was that they believed to be most virtuous. Only those ready to die a forgotten death in unknown lands dared take the pledge.

Cecilia was far from ignorant; she knew the true meaning and hardship such a journey represented. It was unthinkable that she was taking the matter lightly, and yet she’d announced her intentions all the same... She must have really meant it.

Had she been any other immortal nun, Stratonice would have agreed so as to not let the infinity of existence wear away her being. But this girl was imperial, and in the not-so-distant future, she would be the only child of the sitting Emperor.

As the church and state were separate entities on paper, no one could stop the faithful Sister Cecilia from declaring herself a lay priestess and venturing off on a pilgrimage to foreign lands. However, the world was built on truths hidden behind facades and exceptions: just as theologians offered their “counsel” on some secular matters, politicians could put in “requests” with the churches. Having the crown princess wander off on her own accord was problematic to say the least.

“Y-You must be joking,” Stratonice stammered. “You do know what lay priesthood entails, yes? Destitute and forgotten, your pillows will be rocks on the sides of roofless roads, and you’ll be forced to march over the lifeless corpses of the fallen on your path.”

“Yes, and? I may be rather fond of jests, but I consider myself prudent enough not to kid about my course in life. I’m a bit hurt that you would think I was joking, Bishop.”

I’m panicking because I know you’re not! The words climbed up into the woman’s throat, but she managed to swallow them back. Here she’d thought her long years of discipline had freed her from the grasp of wrath, but it seemed the Head Abbess had yet to forsake all worldly emotion.

Those worldly emotions whispered a terrible truth to Stratonice. Cecilia’s tone betrayed an absolute conviction; the girl already considered this decision a forgone conclusion. The busy bishop dwelled for a moment on the ways she might be able to convince the nun of no station to stop, but her childhood memories of how unshakable Cecilia had been when her mind was set caused the poor woman to give up.

And, in truth, Cecilia was the kind of resolute soul to flee her family without hesitation, going so far as to hide away in the Head Abbess’s luggage in the name of not inheriting her house. Nothing Stratonice could say or do would change her mind now.

Just imagining the ridiculous struggle it would take to convince those involved to let her set off unaccompanied made Stratonice want to curl up into a ball. If only, she sighed. If only she were unlikable enough to cast away.

[Tips] Archbishops are the highest-ranking members of the clergy. Each god is served by only one archbishop, and they introduce themselves by their deity of choice to make their allegiances clear. For example, the Sun God’s archbishop would introduce themselves as the Archbishop of the Sun.

However, each religious sect has minor variations on the standard hierarchical system, so exceptions are not unheard of.

Skill is nourished by taste; to foster talent, one must engage with the works of the talented.

Mika had heard these words from her master enough times to know them by heart. Every oikodomurge was also an architect, and if this rule held true, then the young student thought that she must have been truly blessed.

“All the buildings from the era of first light are so beautiful. I love seeing how the fundamentalists and aestheticists clashed in their designs.”

Propping up her chin, the young student sighed in awe as she laid her eyes upon the massive blueprint spread out across the table. It dated back to the days when the Empire had yet to celebrate its first centennial; Richard the Creator and his successor, the Cornerstone Emperor, had finally finished laying the foundations of their nation, and the country had become stable enough for matters of beauty and novelty to enter the public consciousness.

In those days, fundamentalists who aimed above all else to create sturdy and practical buildings out of simple materials had shared the stage with aestheticists who sang the praises of beauty in form; the clashing ideologies had given rise to an indescribable style that continued to charm architects well into the modern day.

The years and months since then were long enough for some immortals of the time to have chosen death since. Nobles liked to rebuild and refurbish to keep up with the latest trends, and the buildings that remained in their original, ancient form were a rarity. More people came and went in the capital than anywhere else, and only a handful of works belonging to owners with classical tastes still stood. Since begging a wealthy landowner to tour their private estate was unthinkable, the best one could usually do was to quietly gaze at a distance.

Yet here Mika was, savoring the original sketches of designs lost to the sands of time. Her heart overflowed with joy, but also with gratitude for the magnanimous Franziska Bernkastel, who had let her into this manor.

It had all begun with a curious twist of fate. Following her life-or-death escape, Mika had been found by Cecilia’s messengers, which eventually led to her acquaintance with Franziska: after reuniting with Erich, the young mage was pulled along to meet the priestess’s aunt—it wouldn’t do to only introduce one of her cherished friends—and quickly earned the woman’s favor.

In her feminine form, Mika’s face was softer and personably somber; the waves of her glossy raven hair were just an inch or two shy of adding a flirtatious note to her overall impression. Apparently, she was the spitting image of the heroine that Franziska was writing in her most recent play.

The playwright had been stuck in a bog of writer’s block, and the student’s appearance threw logs into the furnace fueling her pen. As such, the grande dame began to shower the girl with favors: if the typical immortal illness of pampering the fleeting had claimed her niece, then now was as good a time as ever to broaden her horizons beyond actors for the first time in generations.

Ultimately, Mika found herself in an extraordinary arrangement wherein she had free access to the Bernkastel estate, and could even browse the family’s gargantuan library so long as she sent notice of her arrival ahead of time.

While this manor had originally belonged to Franziska’s clan as a whole, the construction of a new estate closer to the imperial palace had turned it into no more than a spare; nowadays, it was basically the woman’s personal storage unit for anything she left in Berylin. Among her many belongings were books: a writer needed reference material to breathe reality into her works, and the documents she didn’t plan to use in the near future came to rest here.

In the past, the empress had attempted to draft a historical drama, and the evidence of her labor could be found in the ancient blueprints lining the shelves. Her collection began in the Empire’s era of first light, sampled from neighboring kingdoms and satellite states, and even featured illustrations that came in through the once-closed Eastern Passage.

For the oikodomurge hopeful, this treasury of knowledge was drool-worthy. Though the College’s vault of books contained architectural secrets that would take lifetimes to uncover on her own, most of the material there was devoted to the efficiency and practicality of infrastructure. The elegance, refinement, and unique appeal called for in general design was nowhere to be found.

To be fair, this wasn’t without reason. The oikodomurges that graduated from the Imperial College were perhaps the most bureaucratic of all magia. What the state wanted from their designs was very traditional and rigid; as far as the crown was concerned, they were to keep the fancy eccentric stuff to private ventures.

Therefore, those who wished to learn how to make pretty buildings had no choice but to borrow blueprints from magia who built those pretty buildings on the side. Alas, while Mika’s master was a brilliant oikodomurge with strong opinions on foundational skills and disaster prevention, he had exactly zero interest in unofficial projects. Whenever he was invited to tea, it was invariably to discuss the restoration, disassembly, or reconstruction of some decrepit manor or another—his friends were much the same, and were of equally little help.

Mika may have knocked on the College’s doors with a dream to come up with infrastructure that would help support her family living in the icy north, but her ambition extended to erecting a magnificent landmark or two that would be remembered back home for years to come. As earnest as she was, the bizarre and eccentric still caught her eye; the glorious architecture of Berylin had deeply moved her when she’d first arrived, and she wanted to leave something that would do the same for future youths heading into town from the countryside.

The documents here were fertilizer for a refined set of sensibilities. Not only were there blueprints, but the library contained sketches of expected final designs and even tiny models built as teaching tools. Engaging with everything she could find proved a most fulfilling use of her day.

“Doth thine efforts not stray into the land of excess? Overwork shall undo thee.”

“Oh, Lady Franziska!”

The study was lit by but a single window, so as not to ruin the tomes found within; Franziska appeared just as the girl had begun to wish for a reading light. Mika rose to her feet to prepare a greeting fit for the noblewoman, but she waved her down. As always, the vampire had on nothing but an excessively provocative toga as she took a seat across the table.

“Thy zeal is commendable. Would that my troupe were manned by players so keen to study their lines—perhaps then the flower of my direction would remain unwithered.”

“Well, I’m just doing this because I like it.”

“Mistake me not—that you relish it so is the genius I praise. Of late, even Berylin’s most storied stages bedeck themselves in hollow talent, content to trace the skin of the script, bewitched by the polish they put to the apple as the worm-holes flourish within. The better thing—oh, how shall I put this? I would see the intent that hath been lain in the cast’s every twitch and tongue-wag understood and brought to life. Thinkst thou not that it demeans the art for its face to claim himself master of the soul’s full palette while he feels aught but a void that fame might yet fill?”

The leading question drew out a polite smile from Mika. Considering her own position as someone far from the gates of luxury, she felt she had no right to renounce those actors who might use the medium as a crutch to climb the social ladder. Plenty of students began their journey at the College for similar reasons, and there were even professors who considered themselves bureaucrats first and magia second.

Franziska’s viewpoint was that of a woman who had never known poverty, her courtship with art a comfortable one spent chasing its most high-minded ideals. She would seek the pinnacle of her craft regardless of its profit, but to expect the same of those who worked under her was a harsh ask indeed.

Still, silence was golden; an unclear smile was an almighty weapon. Mika was well versed enough in aristocratic dealings to know the virtue in keeping her opinions to herself. Sooner or later, those who failed to mince matters would find themselves minced in a much more literal sense.

For her part, Franziska did not comment on the girl’s vague response or goad her to elaborate: she, too, understood that her statement was but a reinforcement of her own ego. Though she did not force it upon anyone, she made it clear where she stood—the young student marveled that the playwright was a creator to her very core.

“Yet for all my aching,” Franziska said, “I find thee all too fit to rise to the stage...”

“Though I hate to refuse you again, I’ve unfortunately been born to rather middling talents. My success so far in life has been the product of desperately clinging on to keep up with those around me. Relinquish the boot unfamiliar...”

“...Lest foot sores be thy aim. Ah, but Bernkastel singeth thusly as well: he who wears shoes uncounted—”

“—Calls spiders kith and centipedes kin, yes?”

“Thou hast learned thy classics!” the empress cackled merrily.

“I have my friend to thank for that.” The classical poet Bernkastel was Erich’s favorite, and he regularly borrowed lines from the ancient master when the pair played their pompous little games. Mika had remembered most of them as a matter of course.

“Ahh, but truly, black and gold art glorious atop the proscenium. My yearning strains to see thee share a spotlight with my niece’s chosen.”

“Yes, well...” Mika chuckled awkwardly. “I’m sure he isn’t any more comfortable with serious acting than I am.”

Every time their paths crossed, Franziska extended invitations to her troupe or asked if Mika wanted to follow her back to Lipzi when she returned in the near future. Every time, Mika had refused her: she genuinely didn’t believe she had the talent to begin learning a second craft, and there was still much to learn from her master here in Berylin. The young mage had no intention of giving up her dream for anyone, even if that meant refusing the matriarch of a terrifyingly powerful family time and time again.

“A shame, a shame,” Franziska sighed. “Will the College in Lipzi not suffice?”

The Imperial College of Magic was a leviathan of an institution, and the main headquarters in the capital was not enough to serve the entire Empire. Smaller campuses had been built in every region, serving the dual purposes of being schoolhouses and magus bridgeheads. The state didn’t want to let any promising students slip through the cracks, and the facilities were good starting points to help develop the surrounding area.

Truth be told, Mika could still hope to become a magus by studying in Lipzi. While the library there couldn’t hold a candle to the book vault in Berylin, they had access to a tremendous number of transcriptions, so it wasn’t that inconvenient.

“I don’t believe I’d have the fortune to stumble across another teacher as wise as my current master again. Looking at my current ties, I would say I’ve spent the better part of my luck when it comes to human relations.”

However, to encounter a mentor that she could accept as a true master from the bottom of her heart was rare. No matter how well she might adapt to the new environment, people were irreplaceable.

“I see, I see. Then I yield. Let not thy resolution go forgotten.”

Witnessing this fledgling soul abandon fear and modesty to preserve what she valued most put the playwright in a terrific mood. So, after rescinding her invitation, she offered to instead become the girl’s patron—just like she was for her friend’s little sister.

From what Franziska had heard, this penniless student wasted much of her day earning coin, committing precious time to side hustles and day labor funneled through the College. The wealthy noble thought that she might be able to alleviate some of her burden, but was turned down yet again.

“Ingratitude is always met with ingratitude,” Mika said. “If I find a new backer to support me, I will be slinging mud on the name of the good magistrate who sent me here.”

“Ahh, then thou art here by word of recommendation?”

“Yes. I wasn’t the only one with magical talent, but he chose me—even knowing that I’m a tivisco.”

“And so thou hopest to turn thy accomplishments into honors to repay he who hath placed faith in thee. Thy virtue is marvelous.”

Local magistrates ran private schools because imperial aristocrats considered discovering promising youths a noble pursuit. Inspiring the lower classes by uncovering the gifted among them was a matter of course, and supplying the nation with capable talent was another responsibility that came with being part of His Imperial Majesty’s bulwark. Thus, casting doubt onto the merit of one’s benefactor was an ingratitude like no other. If Mika took this new offer of patronage, her magistrate would still earn the acclaim of having discovered a talented mage, but it would be more than a few steps short of what he would have received from supporting a notable magus from beginning to end.

“Forgive my dearth of tact,” Franziska said. “That is the last I will mention the idea.”

“No, I should be apologizing for my discourtesy,” Mika said, bowing her head. “Kicking aside your propositions made in good faith is yet another form of ingratitude...”

“Hah, fret not. In mine eyes, thy integrity in matters of debt and dream both art a delight more than thou shalt ever know. Prithee remain as thou art always.”

Would that the world were filled with persons of thy make, Franziska grumbled internally, my pen might see some use yet. The former empress looked at the girl and prayed to the Night Goddess from the bottom of her heart: May her journey be a bright one.

“Well, then. I entreat thee: let thy passions be of help to my niece and her chosen favorite. I know not from where her habits come, but she has a bullish leaning; and tangled with that golden wolf pup as she’s become, I foresee no shortage of challenge ahead.”

Although Franziska had originally picked the girl out thinking that a friend of her caliber would benefit her niece’s education, she now had a more personal fondness for Mika. Her initial goal had been to find her niece a friend whose memory would stay with her for all her life: one who could understand her as a maiden, who could accept her complaints as a man, and who could offer unique perspectives when neither.

Never had the empress expected that she would take such a liking to the mage herself; she laughed as it struck her that she was yet young despite her long life. Mortal farewells turned the everlasting into adults, but perhaps this world was full of nothing but children.

“Yes, of course,” Mika said. “I swear on my life.”

Greatly pleased by this response, the playwright decided to let the girl use the library freely even after she returned to Lipzi. After all, humanity was the greatest entertainer of all—so long as she lived, the same tale would not arise twice—and it would be such a shame to let this story wither in the bud.

[Tips] Although the Imperial College of Magic has many locations across the nation, the main campus in Berylin is still considered the peak of scholarship.

Early Summer of the Thirteenth Year

Reputation/Stature

Some systems include values to track reputation earned for various great deeds. These can be used for anything from upgrading a well-worn weapon in certain contexts, to giving it a cool name, or something more useful like acquiring a noble rank or citizenship of a city.

Spring bade us farewell and the pleasant aridity of summer came to greet the capital; by this point, the uproar that had once enveloped the city had vanished without a trace. After dominating the rumors around town and then suddenly appearing in the sky, the aeroship had departed, soaring low enough to nearly scrape the towers littering the skyline to make sure we could all get a good look—but now the excitement had faded, leaving only the usual hubbub of Berylin in its wake.

High society saw a great deal of envoys and diplomats rush out of the country to report what they’d seen to their motherlands, throwing everyone’s schedules into disarray. The impact of the vessel’s impression had been greater than estimated, and the crown began pumping in even more funding; as a result, ministries and cadres of every kind were fighting to get their cut.

But none of this had anything to do with us common folk. Sure, we were experiencing some aftereffects: timber traders had begun to hoard their wood in hopes that the Empire would buy it for its next aeroship, driving up the price of firewood, and overzealous entrepreneurs had brought in so many new workers without vetting that the streets were lined with more people of disreputable character than usual. But for now, we were back to peaceful days.

Back home, my family and friends had finished planting their fields. I lazily walked the afternoon streets, imagining the fun they were having, enjoying a nice steam bath and jumping into the cool stream to wash away their sweat.

Make no mistake, though: I wasn’t out on a walk for leisure. Having secured her slothful days filled with nothing but books once more, my employer had suddenly sent me to fetch her some lemonade.

This wasn’t exactly a common occurrence, but it happened every now and again. When Lady Agrippina came across a written description that tickled her sense of hunger or thirst, I was the one that had to go out and find whatever it was that she’d read about. While I understood that this was a privilege held by those who could relegate food and drink to the realm of hobby, being made to run around at her whim was nothing short of a nuisance.

That said, today’s request was something I could get my hands on without leaving the city, so it wasn’t that bad. There was a world of difference between picking up a tome that required a mental saving throw just to look at and fetching some honey and lemons, after all. Besides, the madam had explicitly asked for a cheap lemonade—I suspected she was reading something featuring a lowborn protagonist—making this an extra easy endeavor.

Both honey and lemons could be found at the local market. The former was a tad daunting for a regular person to purchase, but it was commonly used for various dishes and therefore was sold everywhere. Mead was second only to wine in the imperial drink repertoire; beekeepers could be found in every corner of the Empire.

Had I been tasked with finding tree sap extracted only from the finest shrubbery to sweeten the madam’s drink, I would’ve needed to knock on the door of an esteemed merchant; if she’d demanded the sourest lemons carefully grown by the southern seas, this would’ve been a herculean task. I was nothing if not thankful that she was happy with the plebeian stuff harvested from who-knows-where—if only every errand she sent me on could be this simple.

I bought up the necessary ingredients, stopped by an ice-candy shop for Elisa on the way—our master had given me a silver piece and told me to keep the change, so my purse was nice and heavy—and made my way back to the main road to go home. But when I stepped out of the smaller street, I noticed that there was a sizable crowd clogging the passage.

“Neeews! Get your news heeere! Big announcement from the national assembly! Forty assarii a pop! Hey, you there! Don’t pass it around—everyone buys their own!”

The mob was gathered around a newspaper salesman. He was a small jenkin...guy? Wow, was I awful at guessing age when it came to beastly demihumans. Whether he was a boy or man, I could tell from his clothes that he was at least male; anyway, he was shuffling through the crowd to hurriedly dole out his papers.

“Whoa, wait. Seriously? But he looked fine during the parade.”

“Who knows what’ll happen next? This’ll put the whole country right back into a frenzy!”

“It’s one thing after another... We just got over the aeroship too. Man, I feel bad for all the poor ambassadors trying to report this stuff back home.”

“Hey, maybe stirring up confusion abroad is the whole plan. Can’t count anything out with the Bloodless Emperor.”

Scanning the pack of people discussing the news, I saw more confusion than gravity in their expressions; whatever was written must have been incredibly surprising. I was a bit curious, and I still had some change to spare. Maybe buying a newspaper every now and then wasn’t so bad.

The last time I’d read through one had been a lifetime ago. Back then, my involvement at a trading firm had led me to keep up with the four major national publications; though I’d only read those out of obligation, perhaps I might be able to derive some entertainment from the news now that I could lie back and take it in at my own pace.

“Excuse me!” I said. “Give me one copy, mister!”

“Sure thing! Forty assarii—and no change!”

I handed him exactly forty assarii and took the paper in hand. While it was nigh unthinkable to refuse to give change on Earth, most merchants here didn’t carry enough small coinage to guarantee that they could break up their customers’ payments.

“Let’s see what this is all about...” This hadn’t been cheap, so I was going to be upset if the big scoop was unimpressive. But the sheer size of the headline’s typeface proved enough to shock me. “Huh? Abdication?”

The salesman’s pitch had been no exaggeration. The Emperor was going to step down from the throne for health-related reasons, even though his term had yet to end; in his place, Martin I of the Erstreich Duchy was to ascend. The national assembly had also announced that the seven electorate houses had unanimously agreed to see the decision through.

Authority in the Trialist Empire of Rhine may have ultimately rested with the Emperor, but the checks held by a small number of voters meant the monarchy was less absolute and more constitutional. Having the Emperor give up his seat in the middle of a term was plenty plausible: a noteworthy political gaffe or hidden scandal on the verge of coming to light had caused several rulers to relinquish their hold on the Empire for “health-related reasons,” as written here.

For example, seven emperors ago, Remus II the Lenient had tarnished the Baden name by letting several historical satellites and allies escape imperial orbit. Mocked in hushed whispers as the Flippant Emperor, he eventually retreated into the shadows to treat his sickness and handed the reins to the Emperor of Restoration, German I of House Graufrock. For those who had been our one and only Emperor, such tactics were the state’s way of protecting their legacy, even if only in name.

However, this didn’t seem like a fall from grace.

August IV, the Dragon Rider, was a national hero famed for breaking through the feudal lords who’d blockaded the Eastern Passage. A stern leader in matters of war and state, he was highly regarded by all. I hadn’t heard of any recent scandals either. Bastard children and spats with their successors were par for the course in the upper crust, but no such rumors arose; none of his diplomatic mistakes had even been notable enough to circulate around town.

In fact, I would say he was one of the most popular emperors to date. Most country nobodies living in rural cantons would be hard-pressed to recall the name of their local lord, let alone the Emperor. Yet almost everyone knew of the Dragon Rider. While the Second Eastern Conquest had all but finished by the time I’d first come to my senses, those older than me could remember how all sorts of stories came flooding back from the front lines.

But most importantly of all, soldiers had been levied to fight from practically every canton. His Majesty had led the dragon knights to strike at the perfect moment, turning the tides of battle and grasping victory with his mastery of strategy; those who owed their safe return home to the Emperor were sure to extol his virtues. Plus, a victory abroad came with abundant booty, and those who fought had been amply rewarded.

The current Emperor’s achievements listed in the paper were as impressive as one might expect. He’d taken the drakes available to him and bred those with the most docile temperaments, giving rise to a new breed that was obedient enough to be used even for nonmilitary purposes. Furthermore, he’d overturned the entirety of the outdated dragon knight doctrine and expanded their scope to dominate the skies; the air superiority afforded by his reforms led to easier victories when it came to battles of counterspells. Not only that, but he established drake stables across the country and coordinated their maintenance by local lords, creating a system that could deploy a dragon knight unit to any location in the Empire in mere days.

Looking at his long list of military accomplishments, one might be tempted to assume he’d come from House Graufrock. But that wasn’t to say he left softer matters out to dry: he had a strong record of servicing canals and elongating trade routes to strengthen internal trade. Abroad, he’d won over a handful of satellites to the west, and after showing his military prowess, he’d marched to the small federation near the inland sea to the south—though admittedly, they were imperial vassals in all but name—to negotiate tariff rates that undercut those given to their official most favored nations.

The Emperor had displayed his proficiency as both a general and a statesman. He’d had the support of the politicians working under him, of course, but it took brains to select which issues to tackle when they came to his desk; he was undoubtedly a genius. While I still had my suspicions about the Emperor of Creation being a kindred spirit, perhaps the Baden bloodline was simply prone to producing all-rounders.