When the moonlight fell into the sea

A pair of gods were begotten

One was the god of shade

One was the god of light

After eight thousand nights at the edge of the sea

The first god conceals itself in the black palace building

The second god frolics as it dances and sings along to the music

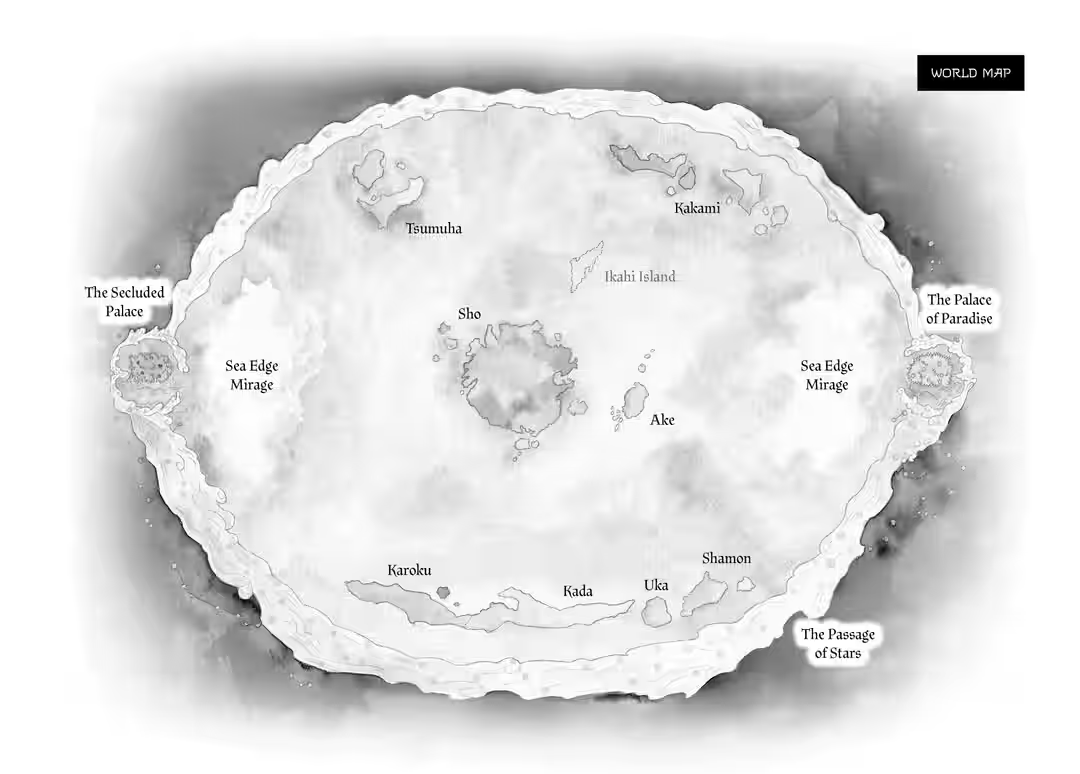

The first in the Secluded Palace, the second in the Palace of Paradise

There is a god that was born from the water gate of the Secluded Palace

Its name, the great turtle god

Its body hewn into eight as punishment for its crime

It was banished from the Secluded Palace

Its head became Je

Its arm formed Pafan

Its leg turned into Guruu

Ravines formed out of its shell

Its blood turned into rivers

Its eyeballs turned into swamps

Its breath created whirlpools and called in the tide

Ears of rice grew on its rotting flesh and dropped their seeds

Mulberry and silkworms grew

People were born

And then, from a single piece of bone,

The white turtle god was created,

Known as the ao god

A god to calm the stormy seas and protect our boats

This god’s eighth generation descendent

The White Sovereign, the first emperor…

—FROM A SONGBIRD TROUPE SONG

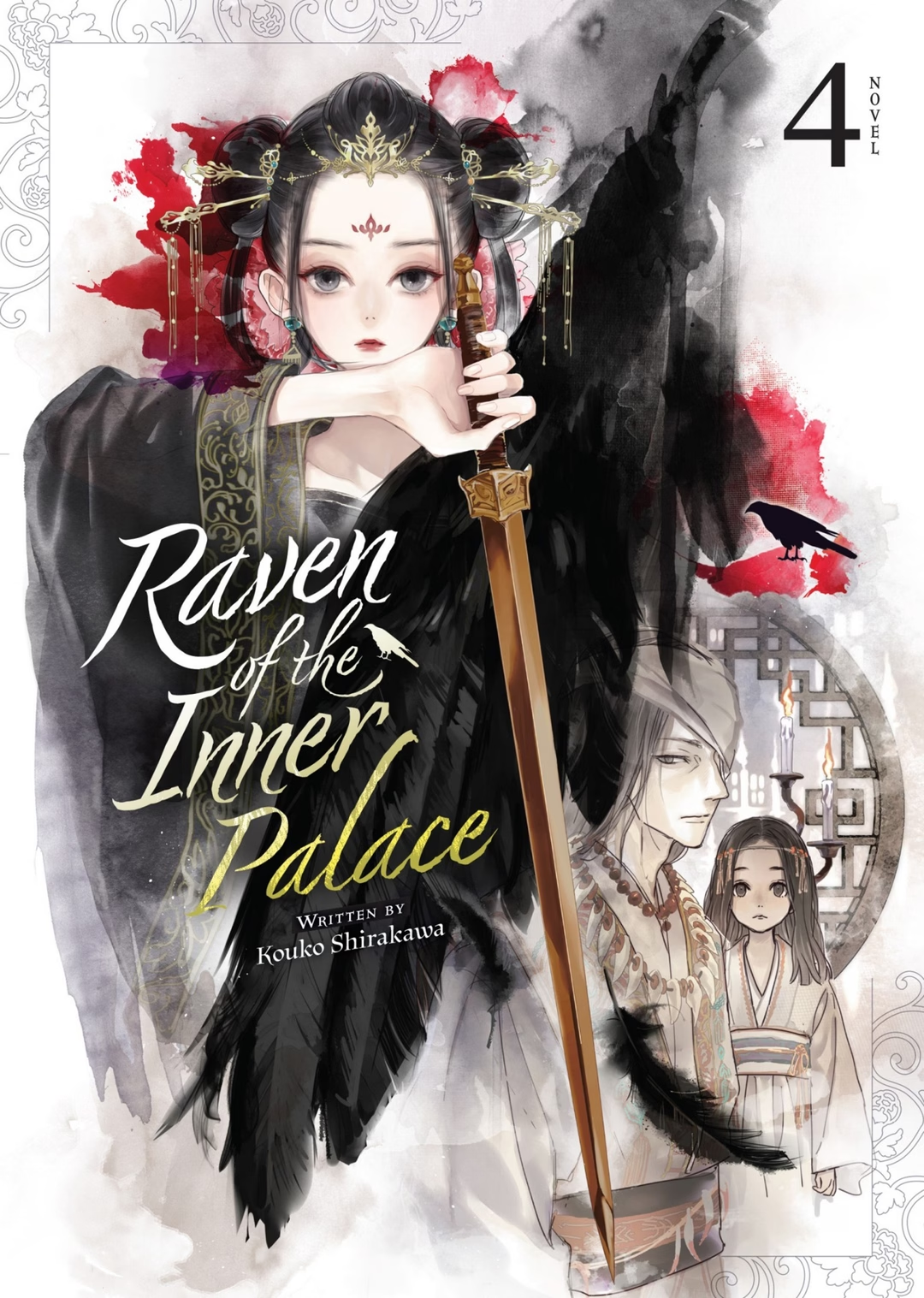

IN FRONT OF BANKA lay a wooden box containing bundles of raw silk. The silk was milk-white, almost the color of morning mist, and had a gentle luster to it. Her father, Choyo, had sent her the most fine-quality fabrics that Ga Province had produced.

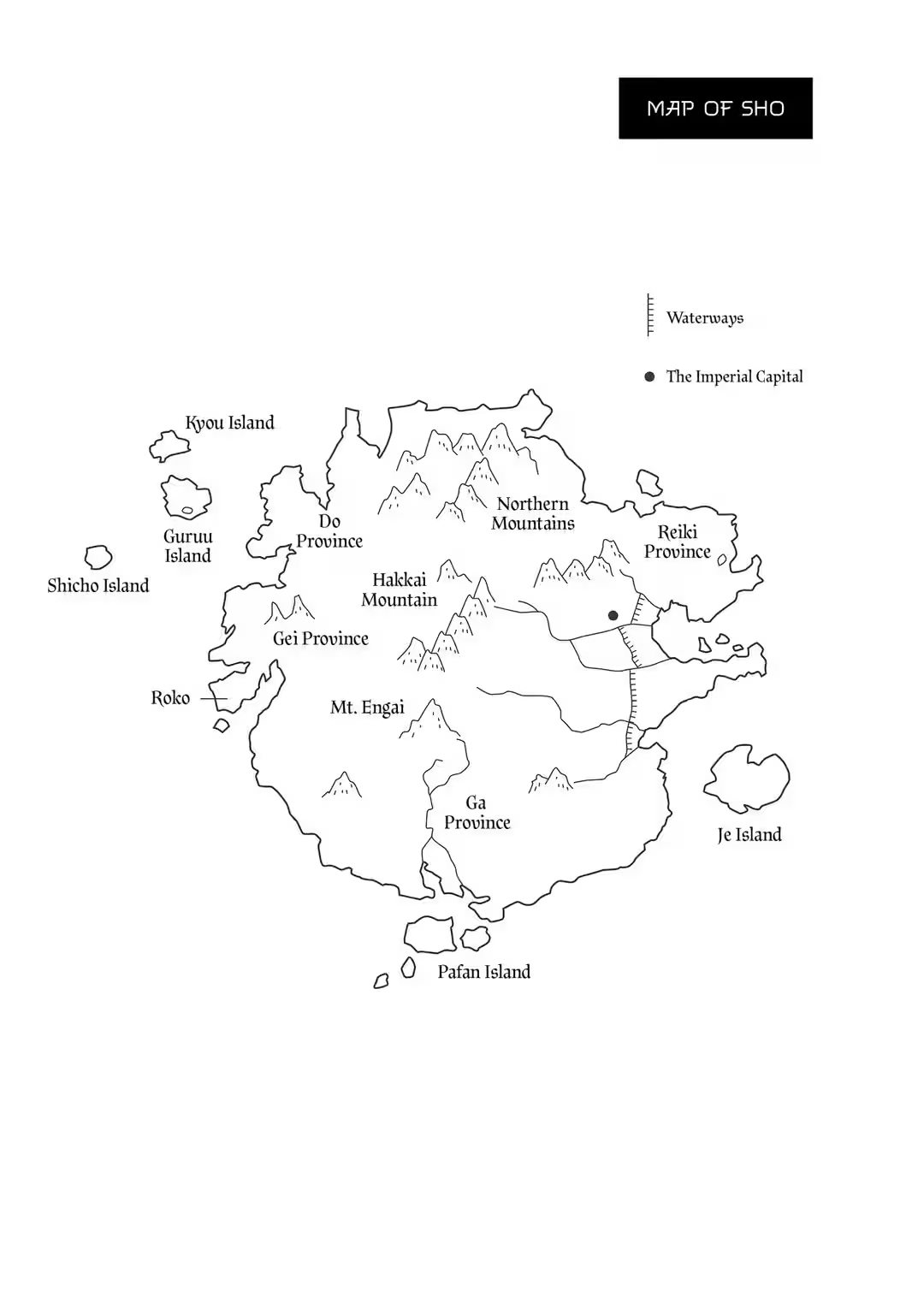

The fine silk from Ga Province was considered the best silk in all of Sho. The silkworm culture in Ga Province began long ago, when the Saname clan came from Kakami and brought silkworms with them. Choyo had put great effort into selectively breeding these silkworms, which led to Ga Province’s silk earning its current reputation. Even Banka herself had taken care of the silkworms from a very young age, under her father’s orders. The silkworms’ spring phase, summer phase, fall phase, and then their late autumn phase… Every day, she would pick mulberry leaves to give to them and clean up afterward. When the silk-raising period arrived in late autumn, she would bring them into the place where they would spin their cocoons. Once they were inside, she would remove the fluff, sort it out, and then repeat the process.

Banka liked the sound of the silkworms eating. She would sit in the corner of the cocoonery and carefully listen to them crunching away enthusiastically at the mulberry leaves. She felt as if she was enveloped by drizzling rain as she listened to them. That sound was the sound of life itself, and it always calmed her down.

However, this only made the dark feeling in her chest when she saw the cocoons she’d chosen being boiled to death in scalding water and their silk being extracted even more chilling. The sound of hot water simmering was the sound of lives being snatched away. Despite all this, the spun silk still had a cold glimmer to it and was—above all—simply stunning to look at.

Whenever that silk slid against her skin, it always felt cold to her—much like standing in a dark shadow on a winter’s day.

Banka removed one of the bundles of raw silk from the box in front of her.

She touched the paper wrapped around the rolled-up fabric that kept it together. Deceitful merchants would wrap lead or scrap iron into that part to falsify the bundle’s weight. Obviously, no one would have used such a trick here—this was a package from her father, after all—but they had done something else. She probed around with her fingers and located a string made of twisted paper attached to the back of the wrapping. This was how she always received letters that—unlike ordinary letters—she wouldn’t want anyone else to see. She peeled off the twisted string and carefully opened it up. On the narrow, long strip of paper, there was a short message in her father’s handwriting.

“Stay away from the Raven Consort,” it read.

Banka’s breath caught in her throat. But why?

Her father never gave a reason for his written commands, and she just went along with whatever her father told her. That was why she told him every little thing that happened in the inner palace, as well as informed him of how the emperor seemed up close. She believed it was all for the good of her father, and by extension, for the Saname clan as a whole.

And that was also why she had written to her father about Jusetsu’s secret—the way the young woman was hiding her true hair color.

Jusetsu saved Banka’s life. She even wanted to be friends with her. And yet Banka still revealed her secret. It had taken a lot of deliberation and weighing the two of them against each other, but in the end, Banka chose her father. However, she couldn’t understand why her father—after hearing about Jusetsu’s secret—concluded that Banka should stay away from her.

That said, he didn’t need to have issued her an order—she would have gone along with whatever he said anyway. But…how was she supposed to act around Jusetsu going forward? There was no chance of them becoming friends now.

Banka passed her hand over the silk. It was cold but felt hot at the same time—so hot that it made her flinch. It was the heat of life—the heat of harvested lives.

There’s no way there’s that much heat within me, Banka thought.

The young woman recalled sorting out the best cocoons back when her job was to separate the good cocoons from the bad ones. Sometimes an unusable cocoon was dead, meaning that there was a dead pupa that had decomposed inside. Those pupae would rot and dissolve into a sticky mess.

I’m just the same as those dead pupae.

Unbeknownst to anyone around her, Banka was rotting internally and turning to mush. She was dying on the inside, while the rest of her looked like nothing was wrong…

***

“I heard there’s a ghost in the cocoonery,” said Jiujiu.

It was the time of night when a veil of darkness had fully descended upon the inner palace when Jiujiu brought up this rumor. The weather was getting cooler with every passing day, and the sun was setting earlier too. Insects could be heard in the distance. And as always, the hanging lanterns on the Yamei Palace remained unlit, plunging the palace into dark obscurity.

The only other person here in the room with Jusetsu was her lady-in-waiting, Jiujiu. Jiujiu decided to stay up until the early hours of the morning to keep Jusetsu company, even though Jusetsu insisted that it was unnecessary. People came to visit the Raven Consort at night, so she had no choice but to stay up. People from every corner of the inner palace would sneak over to the Yamei Palace under the cover of darkness so no one would see them request the help of the black-robed consort, who was said to take on any request—anything from locating missing items to cursing people to death.

“Where…?” Jusetsu asked back. She wasn’t familiar with the term Jiujiu had used.

“In the cocoonery. You know, the place where people raise silkworms.”

“Is there really such a place in the inner palace?”

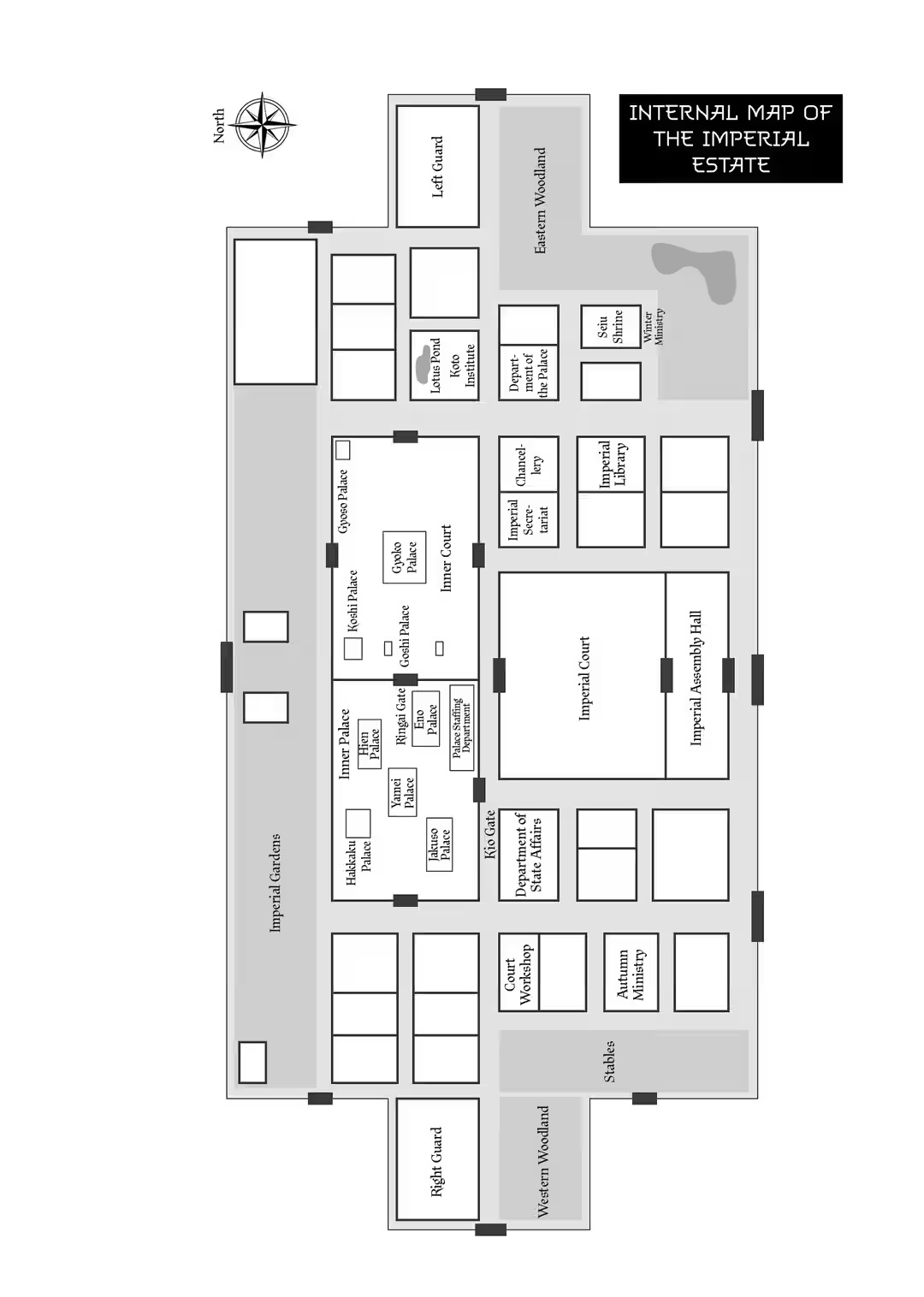

“Apparently, there’s a mulberry forest north of the Hakkaku Palace. It’s there. There was one there in the previous dynasty too, and during the reign of the emperor before last. The previous emperor’s empress hated silkworms, so it got knocked down, but His Majesty built a new one. You’ve heard what an amazing job they do at raising silkworms at the Crane Consort’s family home, haven’t you?”

“Banka’s family home…? Are you talking about the Saname clan in Ga Province?”

“Of course. That’s why the cocoonery was built for Banka. She used to raise silkworms at home. Well, it’s the Hakkaku Palace’s court ladies who take on that work here, but still…” Jiujiu said. “Anyway, that’s where the main part of the story comes into play. There’s a ghost in that very cocoonery.”

“Oh my,” said Jusetsu. “The ghost of a silkworm?”

“No! The ghost of a court lady.”

Jiujiu then proceeded to explain the story.

During the previous dynasty, there was a court lady who worked in the cocoonery. One day, she carelessly stepped on a silkworm and ended up killing it. She didn’t divulge her mistake to anyone, though, and instead chose to stay quiet—for if she did say anything, she’d be punished.

However, on the evening of the incident, she suddenly started experiencing pains, and she began spewing raw silk out of her mouth. More and more kept coming out, showing no signs of stopping. As this was happening, her body soon grew emaciated. Then, another court lady cut the raw silk from her with a pair of scissors in a panic—and the woman collapsed onto the ground with a thud and died. Legend had it that her hair had turned as white as raw silk.

“That was the silkworm’s wrath,” Jiujiu said with fear in her voice. She clasped her hands against her cheeks.

Jusetsu gave her a puzzled look. “That story sounds like it’s about a court lady incurring a silkworm’s wrath and dying from it, not a court lady’s ghost.”

“The story is only just the beginning, niangniang. People say that the ghost of the court lady who died from that curse is the same one who’s in the cocoonery. After that, her ghost started appearing there frequently, blending in with the other court ladies to take care of the silkworms. She’d get mixed in with the others without them realizing, and then disappear as soon as they noticed. She even appeared during the reign of the emperor before last. There wasn’t a cocoonery while the previous emperor was on the throne, so I don’t think there were any sightings of her then, but now…”

“Now that there’s a cocoonery again, she’s come back.”

“Exactly,” replied Jiujiu, giving her a deep nod. “It doesn’t seem like she’s causing any problems for the other court ladies and the curse is seemingly no more, but the court ladies from the Hakkaku Palace are scared.”

“Did someone from the Hakkaku Palace tell you that?” Jusetsu asked.

“No, I actually heard it from a court lady who works for the Eno Palace. She told me the story when we went there earlier today to fetch some scrap paper for Ishiha to practice his writing on.”

Ishiha, the Yamei Palace’s boy eunuch, was currently in the process of learning how to read and write. They needed endless amounts of paper for the task, and they’d get scrap paper from others for that very reason.

There were chatty court ladies at every palace, so Jiujiu would pick up bits of gossip wherever she went. Some of the information she gathered was valuable, but the rest of it was useless nonsense.

“Unless you’ve heard something from the horse’s mouth, you never know how much of it is true,” Jusetsu warned.

“Should I ask a court lady from the Hakkaku Palace for their side of the story?”

“There’s no need to…”

Jusetsu cut herself off and glanced over toward the doorway. Shinshin, her golden chicken, was flapping its wings about. They had a visitor.

“Niangniang,” called a voice on the other side of the doors. It was Onkei, a eunuch who worked as her bodyguard. “I found a court lady lost in the woods, so I’ve brought her with me.”

The Yamei Palace was surrounded by a thick woodland of bay trees and rhododendrons. These woods were dark and dingy in the daytime, and even darker on nights like this when the clouds were covering the moon. If one wasn’t careful, they could easily lose their bearings.

The doors opened, and the petite court lady Onkei had brought with him entered the room with a worried look on her face. She kneeled down in front of Jusetsu and bowed.

“Tankai will soon slack off if I don’t keep an eye on him,” Onkei declared simply, and went back outside.

Tankai was the other eunuch who acted as Jusetsu’s bodyguard. In contrast to Onkei—who was taciturn, serious, and honest—Tankai talked a great deal and slacked off enough to match.

“Raven Consort. There’s something I’d like to request of you, if you’d be so kind as to accept.”

After reeling off that line in a feeble, nervous voice, the court lady prostrated herself in front of Jusetsu. Her head almost touched the floor. Judging by the way the woman was acting, the issue she was requesting Jusetsu’s help for had driven her into a corner.

“I can’t hear you well from over there. Come and sit down here.” Jusetsu pointed toward the seat opposite her. The court lady stood up, looking confused, hesitantly walked over to the seat, and sat herself down.

“Your name?” Jusetsu asked curtly.

“My last name is Nen and my first name is Shuji. I work for the Hakkaku Palace, but I mainly work in the cocoonery.”

Jusetsu exchanged looks with Jiujiu, who stood by her side. Jusetsu had thought that somebody would come and see her if there really was something strange going on—she wouldn’t need to go to the Hakkaku Palace to check herself. And as it turned out, she was right, but she hadn’t expected a visitor to appear with such perfect timing.

“Is there a ghost in the cocoonery?”

“Did you know about that already?” Shuji asked with admiration. She sounded impressed, but not surprised by the Raven Consort’s apparent knowledge.

“No, I just happened to hear a rumor,” Jusetsu said, clarifying. She didn’t want people to think that she knew everything. “All I heard was that there was a ghost of a court lady.”

“That’s correct. It’s the ghost of a court lady who died in the previous dynasty, after incurring the wrath of a silkworm.”

The story Shuji told her about the ghost was the same as the rumor Jusetsu had heard from Jiujiu.

“All of a sudden, that court lady’s ghost was there in the cocoonery. When we bring over mulberry leaves to feed to the silkworms, for example, we’re too busy to look at each and every court lady’s face. However, I suddenly looked up to find a court lady I didn’t recognize giving the silkworms a mulberry leaf. I let out a cry of surprise, and in that same moment, she disappeared. I’m not the only one who’s seen her, either.”

According to Shuji, the court lady had been appearing in the cocoonery fairly often.

“If that was all there was to it, I never would have thought to consult the Raven Consort. I’m busy taking care of the silkworms, so—to be frank—I don’t have the time to worry about one or two court lady ghosts. The ghost would appear out of nowhere just to disappear again soon after, and she wasn’t causing any harm, so it didn’t take long for us all to get used to her. We already had our hands full trying to raise the silkworms unharmed and getting good cocoons. But then…”

The look on Shuji’s face clouded over as she trailed off.

“Did somebody get hurt?”

Shuji nodded. “Yes. Well, it’s not as if we got sick or were injured. No… What happened was even more awful,” she said, hanging her head. Her face was so pale that it was almost green.

“Awful?”

“Yes,” Shuji said. “Some cocoons disappeared.”

Jusetsu felt somewhat let down by that. “Are you telling me that’s even more awful?”

“They’re very important to us. The silkworms raised in that cocoonery belong to the Crane Consort, and by extension are His Majesty’s possessions. We must not let any of them die in vain. And losing them is out of the question.”

“How many did you lose?” Jusetsu asked.

“So far, two.”

“Can you really tell if such a tiny number of silkworms go missing? There must be so many of them in there.”

“Naturally, it’s impossible to tell when they’re at the larva stage, but when the silkworms are mature—that’s to say, when they’re ready to make their cocoons—we move them into a device woven from straw known as a silkworm frame. They make their cocoons there. We place one silkworm into each space, so it’s obvious if a cocoon doesn’t form in one of those spaces. The cocoons that disappeared had finished the cocooning process, and all that was left to do was take away the fluff—but yesterday, they disappeared while we weren’t looking…”

“And you think that was the ghost’s doing?”

“Of course, we initially thought that they might have just fallen out of the silkworm frame for some reason or another, so we searched not only the stand and the floor, but the entire room as well,” Shuji explained. “We looked in the court ladies’ robes too, but the cocoons were still nowhere to be found. That was when one of the court ladies remembered something… According to her, the ghost had shown herself just before the cocoons disappeared. She figured it was the same ghost that everyone else knew about, so she left it to its own devices, just like everyone else does… She didn’t actually see the ghost taking the cocoons, but there’s nowhere else they could have gone. From the moment we entered the room to the moment we discovered they were missing, nobody had left to go outside—and yet the cocoons weren’t in the room, nor were they in any of our robes. There’s no way that any of us could have taken them. After all, we’d be the ones to get punished if cocoons went missing, so nobody would dare to do such a thing.”

“That’s a fair assessment,” said Jusetsu, nodding.

“We haven’t gathered up the cocoons yet, so the Crane Consort hasn’t been told how many there are. That’s why we all got together and decided to pretend that the missing ones died. Umm…” Shuji glanced over at Jusetsu to gauge her reaction.

“I won’t tell her,” Jusetsu assured the woman without a moment’s delay.

Shuji looked relieved and continued. “But then, what if the ghost reappears and takes some more of our cocoons? Tomorrow, we begin harvesting all the completed cocoons. We’ll collect them all and separate the good-quality, usable cocoons from the unusable ones. However, if any of the usable cocoons go missing, we’re done for. We’ll have already counted how many there are, so there’ll be no way of covering it up.”

In that case, there would be a punishment awaiting them. That was why Shuji felt the situation was so dreadful.

“So, you’re saying that the ghost of the dead court lady who incurred the silkworm’s wrath is stealing silkworm cocoons…” Jusetsu whispered. “You may have been able to conceal the missing cocoons last time, but if this carries on, you could find yourself in a difficult situation.”

“Yes. We raise silkworms in the Crane Consort’s cocoonery three times a year—in the spring, the summer, and the fall. The thought of the same thing occurring again makes me anxious.” Shuji covered her face with her sleeve.

“Hmm.” Jusetsu thought to herself. “If this really is the work of a ghost, we risk falling behind if we waste time investigating the spirit. I can start by creating a spiritual barrier in the cocoonery so that the ghost can’t get in, but…”

Shuji looked up. “Really? Will that work?”

“Well, it’s hard to say anything without seeing the ghost for myself.”

“Yes, please, go ahead and try!” Shuji was so pleased that she almost grabbed Jusetsu’s hand, but her expression soon clouded over. “Oh, but Raven Consort, there is another problem with all this.”

“What is it?” Jusetsu asked.

“It has to do with the missing cocoons. If they really did just disappear into thin air, then that’s that—but if the ghost took them away somewhere, then we’ll be in trouble.”

“Why?”

“The silkworms in the cocoonery come from Ga Province,” Shuji explained. “They’re not from this region. If, by any chance, those silkworms emerge from their cocoons and mate with the wild or domesticated silkworms in this part of the country, it’ll cause problems. The breeds will get mixed up.”

“Oh… I see.” So that’s an issue as well, Jusetsu thought to herself. “In that case, do you wish for me to track the cocoons down?”

“They should emerge from their cocoons in about ten days’ time. We’d have to find them before then…” Shuji covered her face. It looked like she was quite distressed by the sudden calamity that had befallen her.

“I think we could talk to Banka—the Crane Consort—about this. I doubt she’d issue you a very strict punishment,” Jusetsu suggested.

“Well, she might not…” Shuji began, initially hesitant to say what she really wanted to. She looked down at the floor. “But her father might.”

“Banka’s father? The current head of the Saname clan?”

“Precisely…” replied Shuji, her eyes darting anxiously around. “Her father is a very harsh person, and the Crane Consort struggles to contravene him. If he orders her to punish us severely, she will do so.”

That was the same man who’d told his daughter to choose between her own life or that of her adoptive sister. A god had placed a curse on the Saname clan that caused the youngest daughter of the head of the clan to die at the age of fifteen with no exceptions. In order to circumvent this curse, Banka’s father had adopted a daughter who was younger than her. When Banka pleaded to her father to save the girl, he told her that she’d need to sacrifice herself in her adopted sister’s place. In the end, the adopted sister died, and Banka lived. This story made Jusetsu wonder what kind of man this Saname Choyo could have been to force such a choice on his own daughter.

Shuji covered her mouth with her sleeve. “I shouldn’t have said that. Please, forget what I just said.”

Jusetsu promised that she would go to the cocoonery the next day, and Shuji soon returned home.

“As generous as the Crane Consort is, her father must be a very unsparing character—considering that even the court ladies fear him,” Jiujiu, who’d been waiting in silence, said once she finally had the chance to speak.

“The actions of a consort do tend to reflect the wishes of her family to some degree, but even so…”

Jusetsu looked over at the lattice window, although she knew there was no way she’d be able to see the Hakkaku Palace from where she was. If Banka—and the Hakkaku Palace—were wrapped around Saname Choyo’s little finger, then that could prove to be a problem.

Still, Jusetsu was sure that Koshun would already know that.

A vision of the young emperor’s unreadable face came to mind. It wasn’t Jusetsu’s place to be worrying about his consorts and their families. The Raven Consort had nothing to do with the outside world, after all.

She sat there in silence, gazing through the window and staring into the darkness of the inner palace at night.

That morning, Jusetsu headed out to the cocoonery with Onkei as accompaniment. She noticed that on the other side of the Hakkaku Palace sat a lush mulberry forest.

“Is that…?” Jusetsu murmured.

“Yes,” Onkei replied as he walked behind her. “The mulberry forest has been there since the previous dynasty. Even when there was no active cocoonery, people still took care of it.”

“Why do they raise silkworms in the inner palace?” she asked.

“It’s not just in the inner palace. There’s another cocoonery in the outer court where selective breeding and research are carried out. That was where raw silk for the emperor and his family’s use was originally produced.”

“Does that mean that the one in the inner palace produces silk for the empress?”

“That’s correct. It used to be much bigger than it is now,” noted Onkei.

His comment made Jusetsu envision the current one as a tiny, compact little building—but the cocoonery that appeared before her eyes was in fact a rather impressive structure. Of course, it wasn’t as grandiose as a consort’s palace, but she spotted three buildings with blue glazed roof tiles lined up in a row, surrounded by roofed mud walls. Jusetsu could hear the sound of palace ladies hard at work coming from the frontmost one, and she spotted eunuchs busily coming and going from the back building, carrying bundles of firewood.

“The one at the back is the mulberry storeroom, and the one at the front is the cocoonery proper,” Onkei explained. This man had frequented all kinds of different places as a spy under Eisei’s orders and knew just about everything, which proved to be very helpful to Jusetsu. Onkei was quite handsome, and the scar from a sword wound that ran down his cheek in a straight line below his kind eyes seemed more like an embellishment that added to his beauty. His skills as a bodyguard also made him a force to be reckoned with. He was quick-witted, but also incredibly self-effacing in every possible way. He was efficient in all that he did and was all over a very competent attendant for Jusetsu to have around.

The Raven Consort headed to the building in front of her, the one said to be the cocoonery. Before she went up the stairs, the door opened, and a court lady hurriedly rushed outside. It was Shuji.

“I apologize for not noticing you’d arrived, Raven Consort,” she said. “I was keeping an eye on what was going on out here, but I assumed it was just a eunuch…”

“It’s fine. Besides, I wouldn’t want anyone to notice me from afar.”

Jusetsu was indeed dressed in her eunuch clothing so no one from the Hakkaku Palace would recognize her. The outfit really was useful—although Jiujiu, who really wanted to get Jusetsu dressed up, had some complaints about it.

Jusetsu then went to take a look inside the cocoonery. The court ladies appeared to be going about their work, harvesting the cocoons. When they heard the name “Raven Consort,” however, the women stopped what they were doing to get on their knees and bow to her, their hands placed together in a gesture of veneration.

“Carry on with your work,” Jusetsu said. “You’ll make others suspicious.”

Startled by her instructions, the court ladies obediently returned to the task at hand.

Inside the room were many shelves and a long table. On the table sat a concertina-like object made of straw. When Jusetsu noticed the cocoons hanging from it, she realized that it must have been the silkworm frame that Shuji talked about last night—the very one used for the silkworms to spin their cocoons on.

“We’re currently in the process of harvesting the cocoons. After this, we take away the fluff that surrounds them, and sort the good cocoons from the defective ones. The difference is that some are suitable for making silk, whereas the rest aren’t. Some of the defective ones are double cocoons where two silkworms have formed one singular cocoon, while others have a dead pupa rotting away inside. There’s also some soiled by urine or bodily fluids, and some with parts of the frame stuck to them… Those are the kinds of cocoons we get rid of,” Shuji explained. “And not only that, but we also sort the good-quality cocoons into those to extract silk from and those that’ll be allowed to emerge so they can lay eggs. The extracted silk is given to the Crane Consort, but after that, she will gift it to His Majesty.”

“In that case, once a cocoon has been categorized as being good, you can’t afford to lose a single speck of it,” Jusetsu deduced.

“Exactly,” said Shuji, casting her gaze downward. In other words, there was no time to waste.

Jusetsu placed a hand on her hair, but then realized that she didn’t have any of her usual flowers in it. She dressed up as a eunuch fairly often, but she still kept forgetting when they were missing.

She held her hand out in front of her and gathered some heat atop her palm. A pale red haze quivered there, which tangled up and intertwined with itself. Then that mist turned into a single petal—and then another one and another—until they eventually formed a peony.

Jusetsu blew on the flower, which turned into smoke and dissipated. The smoke then drifted around the room as if it was swimming through the air, wandering here and there between the court ladies.

The pale red smoke gradually gathered in one particular spot and started to take on the shape of a person—a woman with her hair tied-up and adorned with a simple hairpin. Her pale and narrow face had thin eyelids with well-shaped eyebrows above them that looked like they’d been drawn on with a brush. The long robe that covered her thin body was not modern attire, but it did look well-made despite its simplicity. It suggested that she worked for one of the palaces.

Shuji let out a small shriek of panic and covered her mouth with her sleeve. “Th-that’s the ghost of the court lady that I saw.”

The other court ladies stopped what they were doing and stared at the ghost in wide-eyed astonishment. As they did so, the ghost suddenly moved and started silently walking toward the doorway. Jusetsu shrank back to let the ghost go by. Then it disappeared, looking as if the door had swallowed it up.

The spirit had gone outside.

“R-Raven Consort, did—”

Jusetsu interrupted Shuji mid-sentence. “Let’s follow it,” she said quickly to Onkei.

Onkei swiftly opened the door, and they went outside. The pair spotted the ghost trying to leave through the gate and Jusetsu followed it. The spirit didn’t make any noise as it walked or as its clothes appeared to rustle, and the way the ghost moved seemed the same as any other living person. The only thing that set it apart from the living was the way the hem of its robe didn’t flutter, nor did its sleeves sway as it moved. It seemed unlikely that any court ladies would realize it was a ghost if it just stood there beside them. There were so many court ladies in the inner palace that there may well have been plenty of other ghosts who slipped in and out of the crowd, disguising themselves as the living.

The court lady’s ghost distanced itself from the cocoonery and headed further north, right to the edges of the inner palace. The area had not been maintained well, and the abandoned trees were wild and overgrown. There was no sign of anyone else in the vicinity at all.

Jusetsu had been following the ghost wherever it happened to go, but she stepped out into a clearing and stopped in her tracks. In that area, she saw a small, dense burial mound—clearly someone’s grave—covered in grass and moss. The ghost stood in front of it. The sunlight that flooded the area shone on the burial mound, causing the moss to glisten. As Jusetsu was staring at this scene, the ghost appeared to melt into the burial mound and disappeared into thin air.

What is this?

It couldn’t have been this ghost’s grave, as it was hard to imagine that a court lady would have a grave inside the inner palace.

“Who does that grave belong to?” she asked aloud.

Jusetsu turned around to face Onkei. Unusually, he didn’t have an answer.

“I shall look into it.”

“I’d appreciate that.”

After this short exchange, Jusetsu looked around. The area was surrounded by trees. Some were old with ivy tangled around them, while others were young with thick, flourishing leaves. Others were already rotted, and some had fallen on their sides. It was a quiet place—but going by the way the grass beneath the trees appeared trampled, it didn’t look like the area was entirely devoid of visitors. Perhaps there was someone who still came to visit the grave. After briefly checking the area some more, Jusetsu returned to the cocoonery.

When they got back, they found Shuji standing by herself in front of the room they visited earlier, looking bored. According to her, the other court ladies had gone to another room to take away the cocoon fluff.

Jusetsu told her about how the ghost disappeared at a grave, but Shuji knew nothing about it. It was actually the first she had heard about the burial mound at all.

“The outskirts of the inner palace scare me. As a woman, I can’t go there alone without a good reason…”

This was true.

“I could easily do something to stop the ghost getting in the cocoonery, but…” Jusetsu cut herself off there and thought for a few moments. Simply stopping the ghost from getting in wasn’t going to cut it in this situation. She needed to find the cocoons as well.

“Please. That would be wonderful,” said Shuji, prostrating herself in front of Jusetsu.

Her actions made Jusetsu feel uncomfortable. The Raven Consort wasn’t a god, after all.

“All right then… I’ll start by creating a spiritual barrier for you. We can deal with everything else once we find out whose grave that was.”

Jusetsu pulled a shaft with some string wrapped around it out of her breast pocket and then went out onto the outer passage.

“Take this,” she said to Onkei, asking him to hold one end of the string.

She then trailed it along the floor and encircled the cocoonery. Finally, she tied the two ends together, completing the spiritual barrier.

This wasn’t one of the Raven Consort’s skills, but rather one used by shamans, and was a technique she had utilized many times previously. Reijo, the previous Raven Consort, had been the one to teach it to her. It seemed likely that back in the days of the previous dynasty—back when shamans had been able to come and go from the inner palace—this kind of thing would have been their job. They would have most definitely been useful…or perhaps that was an understatement.

Several things that Ui, the keeper of the treasure vault, had said came to mind.

“It acts as a defense against Uren Niangniang in case the worst should happen.”

“He said that he couldn’t feel at ease unless he had the power to fight back.”

There was probably a valid reason why shamans had played such an important role in the time of the previous dynasty.

“Try to avoid stepping on the string as much as you possibly can,” Jusetsu explained. “It shouldn’t be a problem unless it breaks, but even so…”

After issuing Shuji that warning, they left the room. The court ladies who were waiting outside got to their knees as she appeared, which embarrassed Jusetsu.

“Thank you very much, Raven Consort.”

“I haven’t done anything significant. Stop making a fuss over nothing,” Jusetsu said. “Didn’t I tell you? If anybody finds out I’m here, it’ll cause problems for you.”

Despite her saying that, the court ladies still refused to get up until she left through the gate. Ever since Jusetsu saved Banka, the court ladies who worked for the Hakkaku Palace seemed to deify the Raven Consort above all else—although she really wasn’t that special.

“Now there’s the issue of those cocoons…”

Once she was away from the cocoonery, Jusetsu stopped in her tracks and turned around. The gentle greenery of the mulberry forest glowed in the autumn sunlight. Here and there, she could see places where the branches had been sheared away, presumably to feed the silkworms.

Locating missing items is my forte, but…

Finding cocoons was a whole different kettle of fish. It wasn’t hard to trace a missing item because of its owner, but these cocoons didn’t have an owner.

“Onkei,” Jusetsu called out, looking toward the mulberry forest. “There’s something I’d like you to look into, along with the burial mound.”

“Understood,” he replied.

Something unusual happened that evening when the first watch of the night—the time period between seven and nine in the evening—hadn’t even begun yet. Jusetsu received a messenger informing her that a visitor was on their way.

A boy eunuch arrived at the Yamei Palace. “My master will bless you with his imperial presence shortly,” he announced.

Jusetsu felt that warning her in advance was an unnecessary hassle, but it wasn’t as if she could voice this displeasure to the messenger. Instead, she simply said, “All right.”

The boy eunuch then spotted Ishiha feeding Shinshin in one corner of the room, and a surprised look came to his face. Ishiha made a similar expression back.

“Do you two recognize each other?” Jusetsu asked Ishiha.

“We worked together at the Gyoko Palace,” he replied. For a time, Ishiha had been a domestic servant at the Gyoko Palace, where Koshun lived.

The two must have been good friends, because they were both grinning at each other. It was adorable to see it. But then, appearing to remember his status, the boy eunuch hurriedly apologized for his rudeness, placed his arms together in a polite bow, and went to leave. Jusetsu placed a few boiled chestnuts that were sitting on a tray into his small hands before sending him away. If Ishiha likes him, maybe I could get Koshun to make a habit of sending him to announce his visits, Jusetsu thought—but then she began to question herself. Was that sort of idea really befitting of the Raven Consort? She was unsure.

“How have you been?” Koshun asked calmly after taking a sip of tea. Steam gently drifted up from his cup. His tone of voice was subdued, but it had a slight warmth to it—just like the winter sun.

“Same as ever. Nothing ever changes.”

Even Jusetsu’s blunt response wasn’t enough to provoke any change in his expression. Eisei was waiting behind him and simply frowned—but when Jusetsu looked over at him, he abruptly turned away. It felt a little strange, because normally, that would’ve been the point where he’d give Jusetsu a threatening glare. Still, she was grateful that he spared her on this occasion.

Koshun had brought some candied lotus seeds with him this evening, and they sat on the table. He brought these particular treats with him often, and they were one of Jusetsu’s favorites.

Jusetsu tossed one of the white, sugarcoated seeds into her mouth and stared at the emperor. “What about you?” she asked softly.

Koshun met her gaze, looking surprised. “Me?”

“You asked me, so now I’m asking you. That’s all there is to it.”

“Right. That’s true. Well, as for me…” He tilted his head down slightly, thinking to himself. It was typical of him to give his answer such earnest contemplation. “I’m annoyed that it’s almost impossible for me to talk to the Owl.”

The Owl. Also known as the Burier from the Secluded Palace, who attempted to kill Jusetsu. He also was the Raven’s older brother—the very same Raven that was trapped inside Jusetsu.

“…What do you mean by that?” Jusetsu asked.

The Owl was currently imprisoned for violating the ban on interference. That being the case, the Owl used a large sea snail shell as a messenger so that Koshun could “hear” his voice. Only the emperor could hear it, since he had been blemished by the Owl during their scuffle.

“It seems to be dependent on the tide and the waves. It’s never guaranteed that I’ll be able to hear him when I’m near the shell. It’s not as if I can just carry it around with me.”

If it had been a small shell, it would have been a different story, but the item in question was the shell of a large sea snail. The emperor wouldn’t want anybody to spot him walking around with it, let alone talking to it. They might think he’d gone crazy.

“Wasn’t it the Owl who asked us to find a solution in the first place…? What is there to ask him?”

The Owl had asked the emperor to impart some knowledge on him—and to think of a way they could save the Raven without killing Jusetsu.

“Plenty,” replied Koshun. “There must be things that we don’t know that seem obvious to him. I wanted to speak to him more to see whether that was the case…”

“And how am I supposed to know anything about that?” Jusetsu asked.

“You just asked me a question, so I answered you.”

“That wasn’t what I asked about.”

“Then what were you asking?” he countered.

Jusetsu wasn’t sure how to respond. What did she want to know? What kind of reply had she wanted to hear?

“…I asked you about yourself, so you should tell me about yourself.”

“That’s what I was trying to do,” Koshun said.

“And all you spoke about was the Owl.”

“You really are making this difficult,” Koshun replied coolly. Then, after a brief moment of thought, he began to speak again. “I, personally, am in the same boat as you—no particular changes to speak of. I’ve been sleeping well lately, so I’m in good health.”

“I see.”

Jusetsu wasn’t really sure what she wanted him to say, so just gave him a simple response. Still, she felt satisfied now that she heard that. It was probably what she wanted to hear from the beginning. Koshun never willingly offered up anything about himself.

“That said, the head of the Saname clan is paying me a visit shortly, so I’m busy making all the necessary preparations.”

“Saname Choyo is coming here, to the imperial capital?” Jusetsu asked.

“Indeed. He’s presenting some silkworm eggs to me as a gift.”

The eggs would be sprinkled on top of cards and would later hatch into silkworms.

“Silkworms from Ga Province? He’s presenting you with eggs, rather than raw silk?”

“It’s part of the compensation for what happened before,” Koshun explained.

The uncle of the present head of the clan, who’d been under house arrest, had been plotting to regain his authority. Jusetsu heard that in the end, his past wrongdoings and even a murder charge ended up fully coming to light, leading Choyo to behead his own uncle. Since that man had falsified taxes that should have been paid to the central government, the Saname clan as a whole had now been struck with a considerably heavy punishment.

“I desperately wanted to get my hands on some Saname clan eggs, but they were so valuable that they would never even take them off the premises. There was no way I could take them away by force, either. Fortunately, however, this incident provided with me an unexpected way to obtain some.”

In other words, he must have used what had happened to his advantage so he could request the eggs. Even so, Koshun’s expression remained indifferent.

“Did you want them because the raw silk in Ga Province is of such high quality?” Jusetsu asked.

“Not only does it have a fine sheen to it, but it’s durable too. They’ve carried out years of research in the imperial court’s cocoonery, but no matter what they’ve tried, the silk that other types of silkworms create just isn’t as glossy as that of the Saname clan’s. The silkworm eggs that I’m being gifted are of the best silkworms that the Saname clan have. Eventually, I would like to merge all of the varieties of silkworm in Sho into one.”

His way of speaking was nonchalant, but he was likely determined to make this a reality. He doesn’t usually go into this much depth about things, Jusetsu noted. At the same time, Jusetsu found it intriguing just how “desperate” he allegedly had been to get hold of these eggs. She realized that the Saname clan’s silkworms must’ve been more valuable than she thought.

“There’s a cocoonery in the inner palace too,” Koshun added.

His words startled Jusetsu. The ghost in the cocoonery, and by extension, the case of the missing cocoons, were a secret from him—even more so if they were that valuable.

“The silkworms they’re rearing are from the Saname clan,” he continued. “The Crane Consort’s in charge there.”

“Oh, I see,” Jusetsu remarked simply, avoiding saying any more than she really needed to.

“Apparently, she used to take care of the silkworms when she lived in Ga Province. She knows a lot about the ecology of them too.”

“Ah…” Jusetsu said. Now that he mentioned it, Jiujiu might have said something about that previously. “Is that right?”

“Didn’t you know? I thought you two were close,” he said.

“We haven’t seen much of each other lately.” Jusetsu never visited other palaces unless she was invited. At the same time, Banka used to invite her over regularly, but it had stopped as of late.

“Oh, right. I think she’s been feeling out of sorts recently—a few things have been taking their toll on her. You should pay her a visit,” he suggested.

“Is she physically unwell?” The curse came to Jusetsu’s mind. Had it had a lingering effect on the young woman?

“No,” Koshun clarified, however. “She seems to be depressed. It started when the weather suddenly got cold. That might be the cause.”

“Aren’t you going to check up on her?” Jusetsu asked.

“I have been. We’ve been exchanging letters as well.”

Jusetsu should have known. He was a diligent person, after all.

“I’m actually going to visit her after this,” he went on.

“In that case, you should hurry along. I don’t need checking up on.”

“I wasn’t planning on staying very long. I just wanted to see your face.”

Sometimes, things Koshun said left Jusetsu feeling as if she were frozen to the spot. At times like that, it was impossible for her to reply.

Koshun then stood up. She stared at his face, but it was just as expressionless as always, making it impossible to infer how he felt. He made his way halfway to the door, but then he looked back at Jusetsu.

“Oh yes, I remember now,” he said. “I wanted to tell you about Ho Ichigyo.”

The old man used to work for the emperor as a shaman, back in the days of the previous dynasty. After that, he was hunted down for sending Shogetsu, the Owl’s apparatus, into the inner palace, and had recently been arrested in the prostitution district.

“His fever’s gone down and he’s on the mend. You should be able to see him soon.”

It was unclear if it was because he got rained on when he was arrested or because of stress, but Ho had ended up sick in bed. Due to his old age, one could not be too careful—not even with the mildest of sicknesses. As such, he’d been moved into the inner court so that he could be monitored and cared for.

Jusetsu was relieved to hear that he was on the mend. There was so much she needed to ask him—both about shamans and about the Raven Consort.

“I’ll be back again,” Koshun stated briefly. This time, he really did leave.

After he did, Jusetsu stood up and went to crack open the door. She watched him and his line of eunuchs walk away. The sun had set, and the light from the lanterns they held wavered mistily in the darkness.

She stood in that spot for a little while, gazing at the lights until they disappeared. Suddenly, she noticed another light approaching from a different direction and strained her eyes to get a better look. That light, which came from a lantern, illuminated the figure of a court lady.

It was Shuji.

Jusetsu went down the steps and made her way over to her.

Once Shuji noticed Jusetsu, she fell to her knees, flustered. “R-Raven Consort.”

“What’s the problem? Has the ghost reappeared?”

“N-no. It’s just…” Shuji was so pale that it was plain to see, even in the faintest of light. Her voice was shaky too. Everything indicated that something unforeseen had occurred. “I would…like you to pretend that the things I asked for your help with before never happened.”

“What?” Jusetsu asked.

“Leave the ghost alone. Please…”

Jusetsu frowned. “What in the world are you talking about? Tell me what’s wrong.”

“Nothing’s happened. Please, forgive me.”

After repeatedly asking Jusetsu for her forgiveness, Shuji sprinted off. It looked like she was running away.

Jusetsu silently watched her go. Something must have happened…but what?

***

The next morning, Jusetsu once again put on her eunuch clothes and headed over to the cocoonery. There was no way she was going to simply acquiesce and step back after Shuji had ordered her to leave the ghost alone—the court lady had looked terrified.

There was, however, a small dispute over who was going to accompany her to the cocoonery.

“You took Onkei yesterday. Today should be my turn,” Tankai had proposed—but Jiujiu couldn’t hold her tongue.

“If you’re willing to take Tankai, then you may as well take me!” Jiujiu countered.

“What do you mean, ‘willing’ to take Tankai? It’s not as if you can act as my bodyguard,” countered Jusetsu.

“I’m worried about you having him as your bodyguard. He’s lazy.”

Jiujiu didn’t seem to get along with Tankai. Since it seemed unlikely that she’d make it out of the door if those two kept arguing, Jusetsu just decided to take Onkei with her and left.

“I’m sorry. I shall give Tankai a scolding later.” Onkei apologized to her on his coworker’s behalf as they made their way over to the cocoonery. “I don’t particularly mind Tankai joining us, but I’m sure it’d turn heads if people saw three strangers moving about.”

A voice suddenly cut in from beside them. “That’s why I try to go unnoticed.”

Jusetsu stopped in her tracks, and Tankai appeared from among a cluster of trees.

“You followed us?” said Jusetsu, somewhat taken aback.

“Tankai,” Onkei called out, his voice subdued. As restrained as he sounded, the indignation in it was clear as day. If he were to call Ishiha’s name in the same way, it probably would have reduced the boy to tears.

“But niangniang, being your bodyguard is my job. If you keep leaving me behind, then what’s the point? I feel lonely when I’m left by myself too.”

Hearing that he got lonely made Jusetsu feel uneasy. It made her feel as if she’d done something wrong.

She acquiesced. “…I don’t mind if you follow us, as long as you stay out of sight.”

“Of course I will, niangniang. And I’ll be very useful.”

“Tankai…” said Onkei again. His stifled voice was becoming increasingly frosty, but it didn’t deter Tankai. The man instead pretended not to notice and began walking by his side.

Tankai was true to his own desires, and that was even more obvious when contrasted with Onkei, an excessively restrained and unassuming follower. Jusetsu had never had someone like him around before. Tankai was always certain about what he was after and what he wanted to do. That was a trait that Jusetsu lacked. Since it was so alien to her, there were some aspects to his personality that she had a hard time dealing with—but on the other hand, she found it intriguing. She thought that even Koshun could learn something useful from Tankai’s unrestrained nature.

“Onkei, what did you find out about that grave?” Jusetsu asked as they walked along.

“One of the veteran eunuchs knew about it. He said it’s a silkworm grave.”

“Silkworms?”

“Long ago, silkworms that died during the rearing process and the dead pupae that resulted when extracting thread used to be disposed of there. It became a grave where people would worship the silkworms.”

“Like a silkworm burial place?” Jusetsu asked.

“Yes. Nowadays, they sell the pupae off to carp breeders instead, so they no longer need a place to dispose of them,” he explained.

“Why do they do that?” she asked.

“Word has it they make good food for the fish. Every time the silk is extracted, a eunuch who works at the cocoonery carries the dead pupae out in a bag.”

Jusetsu didn’t know that fish ate silkworm pupae. She figured it was a far better alternative to throwing them away.

“A ghost from the silkworm grave, then,” Jusetsu murmured.

The ghost had made the silkworm grave its home and went to the cocoonery to take care of the silkworms. Had the ghost really been cursed by a silkworm, even after her death? Still, the spirit was too serene for that to be the case.

There was nothing seemingly holding this ghost back. It carried no resentment or sorrow with it. It silently cared for the silkworms, and then it returned to the burial mound once the job was done. It was a quiet ghost.

There was something else that Jusetsu had asked Onkei to look up, aside from the burial mound. “…What about the other issue?”

“There are fifteen court ladies who work at the cocoonery,” Onkei began. “At their busiest, they are accompanied by fifteen additional court ladies. All the women are from the Hakkaku Palace, and that is where they return to when there is no more work to do.”

“They’re not from Ga Province, are they?”

“No. They’re all daughters of merchant families from the imperial capital, local wealthy farmers, or scholar-officials. The main caretakers are the daughters of wealthy farmers, as it’s common for farming families to rear their own silkworms, after all. Apparently, they’ve been taught how to raise Ga Province silkworms directly from the Crane Consort herself.”

“Is that so?” Jusetsu asked. “You’ve certainly done some thorough investigation, considering it’s only been half a day.”

“Thank you,” said Onkei, smiling ever so slightly.

“Hah. Do you suspect that the culprit lies within the ranks of the court ladies, niangniang?” Tankai interrupted. “You’re theorizing that the missing cocoon isn’t the ghost’s doing, but a court lady’s handiwork. I’m right, aren’t I?”

He had good intuition. Jusetsu’s next step was to have Onkei look into the backgrounds of the court ladies who worked for the cocoonery.

“If that ghost was snatching away the cocoons, that should have been the original rumor—but it wasn’t. All the ghost did was appear to take care of the silkworms. There’s also the fact that silkworms from Ga Province—or rather, the Saname clan’s silkworms—are very valuable. It would make sense if someone took advantage of the ghost rumor to steal cocoons.”

“And you think that a court lady who was taking care of the silkworms was able to do that?”

“The cocoons disappeared while they were taking care of them. I don’t see how it could be anybody else. When they noticed they were gone, the workers allegedly searched the room and the court ladies’ robes for them, but I’m sure there was a way they could have kept them hidden. It’s much more logical than the idea that an outsider took them.”

“Does that mean we need to pressure the court ladies for answers?” Tankai asked.

“No. I believe there’s a court lady I need to speak to first.”

“Nen Shuji?”

“Not her,” said Jusetsu. “…Onkei?”

“Yes.” Onkei nodded, appearing to understand. “I know who saw the ghost the day that the cocoons went missing.”

A smile came to Jusetsu’s face. Onkei knew exactly where she was coming from.

“Are you saying that court lady was the one who stole the cocoons?” Tankai asked.

“If it was her that stole them, then it would be easy for her blame it on the ghost,” Jusetsu replied.

“And the ghost really does exist. I wouldn’t be surprised if it really did appear on that day. What if another court lady took advantage of the commotion over the ghost’s appearance to steal the cocoons? Oh, or maybe they only realized the cocoons were gone after that court lady mentioned the ghost? It wouldn’t make sense if so,” said Tankai, now expressing his own answers.

“You’re right. If she had taken advantage of the commotion, I’m sure she would have made a scene when the ghost appeared to divert people’s attention—but there was no such event. She reported seeing the ghost after the cocoons were found to be missing.”

“Doesn’t that mean that she was trying to blame the theft on the ghost because she was the one who really did it?” Tankai said.

“Perhaps,” Jusetsu replied. She then posed a question to Onkei. “What is that court lady’s background?”

“She’s the daughter of a farming family.”

“She must have some link to a silkworm farming family, then.”

If not, there’d be no use in her getting her hands on one or two of the cocoons—they wouldn’t be able to be hatched or bred.

“I don’t know the sex of the cocoons that were stolen, but if she gets them to crossbreed with silkworms from another silkworm farming family, she’d get some eggs—and not just any eggs, but ones descended from the Saname clan’s silkworms. Alternatively, if the two stolen cocoons were of the opposite sex from each other, she could obtain purebred Saname clan silkworm eggs. That would mean that the Saname clan’s closely guarded silkworms will be out in the open.”

Tankai scratched his head. “…This is getting to be an important case, isn’t it?”

“It really is important. Koshun is currently expecting a visit from Saname Choyo himself. If the cocoons have already been taken away, it will be highly concerning.”

But this, however, was the inner palace. There weren’t many opportunities to contact the outside world. The cocoons were probably still hidden away somewhere inside.

“Don’t you think we should start by informing my master—or no, the Crane Consort?” Tankai asked.

“I shall do that once I’ve confirmed whether this was the doing of one of her court ladies,” Jusetsu said. “And I’m worried about Shuji too.”

“Didn’t she come out of nowhere and tell you to forget about the ghost?”

“Yes. What are your thoughts on that?”

“At times like that, there’s just one possibility.” Tankai said with a slight laugh. “Someone must have threatened her.”

Once the group arrived at the cocoonery, Jusetsu and her bodyguards split up in two different directions. Onkei started by calling over the court lady in question, making sure that Shuji wouldn’t notice. Meanwhile, Jusetsu and Tankai decided to wait for her at the back of the palace building where they wouldn’t draw any attention to themselves.

Changing it up from the day before, they went around to the back gate to sneak in unnoticed. From the main gate, they could see that there were eunuchs working in the palace building at the back yet again. All the doors of that building were open, and the eunuchs appeared to be cleaning. Some were carrying mulberry branches outside, while others were sweeping the floors, brooms in hand.

“This was the mulberry storage room, wasn’t it?”

“Yes. They must be tidying up since they’ve finished taking care of the silkworms.”

Jusetsu called out to one of the eunuchs who was gathering some mulberry branches together and bundling them up with string. He was young with a small build and was quite good-looking. Most eunuchs who were selected to work for a consort’s palace were pleasant to the eye.

Seeming to assume that Jusetsu was just another eunuch, he gave her a casual reply as he wiped his sweat. “What?” he said.

“Are you throwing those branches out?”

“I wouldn’t dream of it,” replied the eunuch, opening his eyes wide in surprise. “We can’t let a single thing in the inner palace go to waste. After all, they belong to our master. These can be turned into dye or firewood.”

“I see,” she said. “And the pupae end up as carp food.”

“Exactly.”

The eunuch put the bundle of branches on his shoulder and carried them over to a spot by the gate. Mulberry branches had been piled up there. I didn’t know there were so many uses for these things, Jusetsu thought as she began walking toward the cocoonery building. There was no sign of anybody near the room where the silkworms had been kept, because after all, there were no silkworms inside anymore. In contrast, one could hear people actively working in the other rooms.

“If they’ve finished selecting which cocoons to use, then their job today must be extracting the silk,” Tankai said, prompting Jusetsu to stop walking.

“Do you know much about silkworms?”

“I wouldn’t go that far, but we had them in the family I was born into. It’s normal for people with large residences to build cocooneries at their own expense to supply silk for them in our terri—I mean, our region.”

He was clearly about to say our territory.

Jusetsu stared at Tankai’s face. She’d heard that he was a thief before becoming a eunuch, but she didn’t know who he had been before becoming that thief. His face was beautiful enough for him to have been made into a eunuch after being caught by the police, and not only that, but there was a sense of refinement to his good looks.

Jusetsu didn’t know what prominent family he originated from, but she wasn’t going to pry unless he offered up this information himself.

“…By ‘extracting the silk,’ you mean from the cocoons, don’t you?” Jusetsu turned in the direction of the back of the palace building.

“They put the cocoons in boiling water and look for the openings. Then, they pull the filament out. I saw people do it when I was a child, but it takes some real expertise. The pupae inside get killed in the boiling process. You can also kill the pupae by drying the cocoons out, but I hear that doesn’t create the same special sheen or something.”

That made sense. There was steam leaking out of the room’s lattice windows. As Jusetsu was gazing at it, somebody called over to her.

“Niangniang.”

It was Onkei, who had a woman following him. She must have been the court lady they were looking for.

“This is the court lady who saw the ghost the day that the cocoons went missing, but…” Onkei looked a tiny bit hesitant, but Jusetsu couldn’t work out why that might be. “…She says there’s something she’d like to tell you about the ghost, niangniang.”

“Oh?” said Jusetsu, tilting her head to one side in confusion. What could it be?

The court lady introduced herself as Man Jakusui and greeted Jusetsu with her hands placed together in a sign of respect. Jusetsu remembered seeing her in the cocoonery the day before. The ends of her eyebrows drooped downward, making her look timid. Her soft cheeks were as white as cocoons.

“What is it that you wanted to tell me about the ghost?”

“Oh yes,” responded Man Jakusui humbly. “Umm… I wasn’t sure whether I should have told you right away yesterday, but…”

“Should have told me what?”

“That it was different.”

“What was different?” Jusetsu pressed.

Jakusui wasn’t getting to the point.

“Well, you see, it’s just that…” It seemed that she was struggling to be direct because she didn’t know how to say something. Jakusui was moving her hands about and repeated herself impatiently. “The ghost.”

Jusetsu was silent for a few moments. “…It was a different ghost. In other words, the ghost you saw, and the ghost yesterday, were different people. Is that what you’re attempting to tell me?” she asked.

“Yes, exactly. That’s exactly it,” said Jakusui, nodding repeatedly.

What could this mean?

“When the cocoons disappeared, we were working, checking how the cocoons were doing. We check how each of the cocoons are coming along, one by one, and keep a record of it. These records are very valuable at all stages of the rearing process. We use them as reference for our rearing work going forward, to help us create even more usable cocoons in future batches. As I was focusing on my work, I suddenly sensed that the court lady opposite me wasn’t someone I recognized, and I looked up. That was when I realized that I never saw her face before,” the court lady said. “I heard about a ghost appearing in the silkworm-rearing areas, so I assumed it was her. I don’t really remember what she was wearing or what her outfit was like, but she had a completely different face from the ghost from yesterday. She looked more, how can I put it… I feel like she had a childish look to her. She had a sweet face with plump cheeks and bright eyes. Also…” The court lady paused there for a moment. “It was faint, but it looked like she was wearing makeup too. We court ladies don’t wear makeup at work—we don’t want to get it on the silkworms or on anything inside the room by accident. It’s even more important when the cocoons are still forming. If white powder or lipstick were to stain them, they’d be ruined.”

“But the ghost you saw was wearing makeup?” Jusetsu asked.

“Yes. We were very busy, so even when I did realize it was a ghost, it wasn’t as if I could bring my work to a halt. And it didn’t matter how scary or shocking it was, I couldn’t make a sound. I suppose I was scared that it would notice me if I raised my voice… That’s how I felt at the time. I tried to watch it out of the corner of my eye, making sure not to look at it too much, but it the ghost quickly moved away.”

“It moved away? It didn’t disappear?”

“It left my field of vision. It didn’t disappear in a puff of smoke or anything like that. Everyone around me was standing up, busy at work, so once it disappeared from my line of sight, it blended in among the others. The uproar started after that, when people realized that the cocoons weren’t in the frame anymore.”

Jusetsu thought about this. If this court lady was the thief who stole the cocoons, she wouldn’t need to say all this. She could have just insisted that she definitely saw the ghost, and that it was unmistakably that one from yesterday. After all, it wasn’t as if Jusetsu would have been able to know that she was telling a lie. Then it’d be a simple matter of whether she was brave enough to lie through her teeth or whether she’d have to come clean. The court lady wouldn’t have come out with this unnecessary story.

Eventually, Jusetsu asked, “Why didn’t you inform me right away yesterday?”

“I was worried that I imagined it, which made me unsure whether to tell you or not,” Jakusui said. “I was also worried that the ghost would curse me as well…”

“Curse you ‘as well’? What do you mean?”

“Oh, umm, last night, there was some ghost trouble…”

“Ghost trouble…”

Jusetsu had a realization. So that’s what happened.

She then turned to Jakusui. “Can you call Nen Shuji for me?” she asked.

“No problem at all,” said Jakusui. With that, she trotted back over to the cocoonery.

“Have you heard enough from that court lady?” Tankai asked skeptically.

“I have,” Jusetsu replied simply.

“You must believe her, then,” he said. “Which means…”

“It means that we’re now dealing with two ghosts.”

A short time later, Shuji arrived, looking worried that someone might see her. She was pale. “R-Raven Consort, I told you to forget about…”

“Did the ghost threaten you?” Jusetsu asked, getting to the point.

Shuji’s eyes opened wide. “Y-you knew?”

“I assume it told you it would impose its wrath on you. Rest assured, that shall not happen.”

“I-is that true, Raven Consort?” Looking as if she were about to cry, Shuji tried to cling onto Jusetsu, but Onkei stopped her.

“It’s fine,” Jusetsu told him simply before taking Shuji’s hand in hers.

Once Onkei had taken his hands off Shuji, the court lady fell to the ground. She cried as she grasped Jusetsu’s hand. “Raven Consort, I’m so…frightened.”

“What happened?” Jusetsu asked, trying to calm her down. Shuji was now sobbing convulsively.

“It happened yesterday… Yesterday evening. After finishing work, I was walking along the outer passage when something rolled out in front of my feet. When I stopped and looked at it, I realized that it was a cocoon. Then, I realized there were several more cocoons on the ground, further down my path. Just as I was wondering what was happening, a figure suddenly appeared in the lattice window next to me…” Shuji was shaking with fear as she told the story. “It was dark inside, so I couldn’t make it out very well, but it looked like a court lady. The figure was standing at my side, facing me. And then it spoke. ‘If you get in my way any more than you already have, you’ll pay for it.’ It was a bloodcurdling, frightening sort of voice. I was struck with terror and scurried back into the room where everyone else was to escape. When I told them I saw a ghost, they decided they needed to go and check for themselves, so I joined them in returning to the spot where I saw it. Then—as you might expect—the ghost was gone, along with the cocoons. Anyway, it was so horrible. I didn’t know what to do, so I…”

And that was when she returned to the Yamei Palace a second time and ordered Jusetsu to cease her investigations into the ghost.

Jusetsu had been listening to Shuji’s story with her head tilted slightly to one side. She nodded. “I see… How exactly did this ‘bloodcurdling, frightening sort of voice’ sound? Was it high, or was it low? Was it feeble, or was it a more booming voice?” she asked.

“How did it sound? Hmm, let me think…” Shuji closed her eyes tight, perhaps in an effort to recall it. “It wasn’t high-pitched, but it wasn’t necessarily low, either… Oh yes, it wasn’t a young person’s voice. It was hoarse and croaky, which may have been why I found it so scary. It wasn’t the voice of a very young court lady, you see.”

“Was it a voice you remember hearing before?”

“No… Oh, but then again…” Shuji thoughtfully brought her hand to her mouth. “Now that you mention it, it did seem familiar. Still, no, I’m not really sure.”

“You said that you went to the room where everyone else was. Who do you mean by ‘everyone else’?”

“The other court ladies… I believe everyone was there, but I was so shaken up that I don’t remember clearly.”

Jusetsu peered at Shuji’s face. “Well then, it wasn’t a ghost. The reason I know that is because I put a spiritual barrier there so no ghosts can appear. That’s a definite.”

Shuji stared intently at Jusetsu, as if her eyes were sucking her in. “U-understood, Raven Consort!” She nodded forcefully, her cheeks flushed. “Oh, but in that case, who would have done such a thing?”

“It must be somebody who doesn’t like to be scrutinized,” Jusetsu reasoned.

The ghost who threatened Shuji and the ghost that stole the cocoon were likely the same person.

Jusetsu had previously said that there were two ghosts, but one was a fake.

“Could I take a look inside here?”

Before waiting for an answer, Jusetsu went up the staircase and stepped into the room where the court ladies were standing around, working. The air was thick with steam, and a bloodlike stench that accompanied it. Cauldrons filled with gurgling water were set up on the two stoves. Inside these cauldrons, the cocoons were being boiled. The court ladies standing next to them picked up a few cocoons, swiftly located the ends of their threads, and pulled them out. They carried out this task at lightning speed. The threads that were pulled out were then wound up on reels.

Some court ladies were removing cocoons from the pots after they were finished being made into thread, whereas others were tasked with changing the hot water. Others had the job of removing the thread from the reels. The ladies’ cheeks and hands were red from the heat, and there was sweat on their foreheads and necks.

Every single court lady was silently absorbed in her work, and they didn’t even notice when Jusetsu entered. Jusetsu’s eyes were drawn toward the basket of cocoons that had been placed in the corner of the room. It was obvious even to the untrained eye that there were some dirty cocoons mixed in with them. They had to be the waste cocoons—the ones that were sorted out from the good-quality ones.

Making sure not to get in the way of the court ladies’ work, Jusetsu soon went back outside. “Are those the waste cocoons in the corner of the room?” she checked with Shuji, who was standing in the outer passage.

“That is correct,” Shuji answered.

“Do they get thrown away?”

“No. We can’t use them to make offerings, but we can still take the thread to make court ladies’ robes or turn them into floss.”

“Were they put there yesterday?” Jusetsu asked.

“Yes,” Shuji confirmed. “The good-quality cocoons are strictly supervised in another room, while the bad ones…”

“Isn’t it therefore likely that those were the ones used to threaten you last night?”

It seemed that it would be easy for anyone to bring them outside as long as they knew where they were kept.

“If so, then who could the court lady who pretended to be a ghost to threaten me possibly be? It’s not any of them…” said Shuji, glancing over at the room with the steam wafting out of it. “If it had been one of the ladies I work with, I would have been able to tell who it was—even if it was too dark to make out the shape of her face. After all, I heard that voice…”

Jusetsu watched the steam dissipate inside. “…Rather than searching for who it might be, it may be quicker for us to lure them out.”

Around dusk, after Jusetsu changed out of her eunuch outfit and into her ordinary black robe, she made her way to the silkworm grave with Onkei accompanying her. She walked around the mossy old burial mound and looked up at the trees.

She could tell that somebody had been visiting this spot the last time she came—somebody had clearly stepped on the undergrowth.

“Niangniang, somebody’s coming,” Onkei whispered.

Jusetsu hid herself behind the mound while Onkei lurked among the trees.

They could hear the footsteps of someone approaching, trotting through the gloomy shade of the trees. These were light footsteps—the footsteps of someone slim and not especially tall. The person seemed as if they were stopping in front of the grave for a moment, but then slowly and quietly crept over to one of the trees instead—a large, old tree with several hollows.

When he put his hand in there, Jusetsu called out to him.

“The cocoons aren’t there anymore.”

Still positioned as if he were about to reach his hand inside, the man turned around, almost jumping into the air. Jusetsu stood up, and Onkei also appeared from among the trees.

“Does my face look familiar? I believe we exchanged words behind the mulberry storage room earlier today.”

The man gave Jusetsu’s face a close look and then went pale. “Oh!” he exclaimed. “You’re not a eunuch…”

The man was the young eunuch who was tying together some mulberry branches and told Jusetsu how they’d be turned into dye or firewood.

“I heard your name is Rijo,” Jusetsu said. She had Tankai look into the eunuchs who worked at the cocoonery, researching everything from their family backgrounds to their wealth. “I know every last thing about what you’ve done. You pretended to be the ghost of a court lady to sneak into the cocoonery and then stole the cocoons, didn’t you?”

When it became apparent that someone was apparently pretending to be a ghost, it became clear that the court ladies had nothing to do with it. If a court lady were to steal a cocoon, they wouldn’t need to go out of their way to create a ghost to blame it on. As Jusetsu had once suspected, all they’d have to do was secretly snatch the cocoons and then claim that a ghost had appeared.

Rijo was of a diminutive build and had clear, bright eyes. If he was wearing makeup, he’d be able to disguise himself as a court lady with no problem. Once he’d transformed himself into a woman, it’d be hard even for those who knew him to discern that it was him—just as Shuji hadn’t noticed it was Jusetsu when she first appeared in her eunuch uniform.

“Uhm… I…”

Rijo’s face was now a sickly shade of blue. He was shaking and didn’t seem like a particularly gutsy young man. He started to back away, but all of a sudden, he began to run. Onkei began moving immediately, but he didn’t actually need to do anything—Rijo tripped in the grass and fell over. Onkei then grabbed hold of his arm and wrestled him to the ground. Rijo did struggle, but Onkei’s arm didn’t even flinch under his grip.

“Y-you’ve got this wrong… I just…!” Rijo then began to cry inconsolably. He was a young man, not yet twenty—and seemed as if he’d be equally capable of doing a little bad as he would a little good.

“I know that this scheme wasn’t solely your doing. You must have been enticed to do it by one of the eunuchs tasked with carrying the silkworms outside. Did he say you’d be in for a financial reward?” Jusetsu asked. She suspected that asking him in this way might make him confess, and sure enough, the eunuch simply nodded.

“H-he did. But I didn’t do it because I wanted the money. At first, it was just some friends having fun.”

“Having fun?” she repeated.

“We wanted to test whether I could get away with disguising myself as a court lady. That was the bet.”

Jusetsu had heard that a small proportion of eunuchs were enthusiastic gamblers. After all, they didn’t have much else to do in the way of entertainment.

“So you’ve been sneaking into the cocoonery? Had this been going on for some time?”

“No. At first, I just tried hanging around outside, and they’d bet whether the other eunuchs or court ladies would figure out that it was me. That dare went so well that they said it wasn’t even worth betting on—so it then became about whether I could pretend to be the rumored ghost that haunts the cocoonery. But that alone was too boring, so they then bet on whether I could steal a cocoon…”

It was basically a practical joke that had gone too far.

“I was planning on putting the cocoons back right away. I mean, there was no point in me having them. I figured I could just roll them back to the corner of the room or something. But then Sekian found out, and…”

“That’s the eunuch who’s tasked with transporting the silkworms, isn’t it? Weren’t you friends?”

“He’s my superior,” Rijo explained. “He told me that I might as well sell those cocoons to a silkworm farming family. Obviously, that scared me, so I said no—but Sekian said he’d expose me for stealing them…and he threatened me, saying that it was a serious offense…”

Rijo began sniffling away, which made him look extremely childlike.

“Due to the nature of his job, Sekian is acquainted with some carp breeders. He said he had an idea about which silkworm farming family would be interested in buying the cocoons. He told me he’d negotiate and sell them next time he brought out the silkworms, so ordered me to hide them away until then.”

“And so you hid them in the hollow of the tree until the silkworms were to be transported outside the premises?”

“I knew about this place because I came this way to fetch firewood for the cocoonery. I figured that the hollow would be the perfect place.”

If he had the cocoons at hand, he’d put himself in danger if someone investigated. Jusetsu therefore guessed that the cocoons had to be hidden somewhere else, and this was the place that came to her mind. While it should have been a spot where nobody would ever venture, a visitor had left their tracks behind. When she searched the area, she found a cloth parcel stuffed into the hollow of a tree with two cocoons inside.

Today, the thread was extracted from the cocoons, and tomorrow, the silkworms would be transported to the carp breeders. That was why Jusetsu suspected that the thief would come retrieve them tonight.

“Then it must have been you and your helpers who threatened Nen Shuji to keep quiet yesterday.”

“They just told me to stand there pretending to be a court lady again. All I did was stand. I did hear that they were going to give a court lady a little threat, though, and I just assumed it was a prank. The one who rolled out the cocoon and put on that voice to threaten her wasn’t me. It was Sekian.”

Sekian was probably being tied up by Tankai right about now.

At any rate, although it was good that the cocoons had not yet been taken away, there was still a risk that the Saname family’s prized silkworms would then be out in the open. Jusetsu had to inform Banka and Koshun of what had happened, and otherwise leave the matter to them.