PROLOGUE

Dawn was approaching far across the endless snowy plains. The air was painfully cold, and every breath brought the throb of a headache. The sheep had been let out in the predawn darkness and could be seen at the edge of the horizon.

This scene had repeated itself for centuries and would surely continue to do so for centuries to come—the clear sky; the rolling, snowy hills; and the flock of sheep that trod them.

Lawrence took a breath and then exhaled. The wind carried the vapor away in a swirl, and his eyes followed it as it went.

Beside him, his still-sleepy traveling companion crouched down and poked at the snow with her finger.

“It may be gone, I hear.”

The response to his sudden words was no great thing. “One can hardly lose what one does not already have.” She made a snowball with her small hands and then tossed it away.

It disappeared in the snow with a soft noise, leaving a hole behind.

“We humans can indeed lose again things we’ve lost already.”

Another snowball opened up a second hole before his companion replied to him. “Such reasoning’s beyond the likes of me.”

“Do you imagine things are over when you die? It’s not so. When we die, we either live on in heaven or die yet again in hell. Losing something already lost is not so very difficult.”

His companion decided against making a third snowball and breathed on her cold, red hands. “’Tis dreadful indeed to be a human.”

“It surely is.” Lawrence nodded.

After a moment passed, his companion put another question to him. “How does one lose such a thing?”

“It’s dug up, carved out, with not a trace left behind—or so people say.”

Lawrence heard the sound of rustling fabric and turned to see his companion bent over in laughter.

“Aye, ’tis dreadful to be human! Only a pup could dream up such a notion—I surely never could.” She straightened and was still fully two heads shorter than him.

Just as the adults’ faces he had looked up to as a child always seemed vaguely frightening, the face of any girl he looked down on now always seemed weak and ephemeral. But this girl seemed stouthearted and strong, despite her stature, which was surely no illusion.

“Still, ’tis a bit pleasing to hear as much.”

“…Pleasing?”

“Aye. The first time, I lost what I did utterly unbeknownst to me. It had nothing to do with me, and there was nothing I could do to stop it from happening.”

She took a step, two steps, leaving footprints in the snow, as though to prove the weight of her light-seeming body. The footprints were small but distinct.

“But this time—” The hem of her robe whirled around her, and now the morning sun was to her back as she smiled. “—This time I will be there. ’Twill be my life after death.”

She grinned, and from behind her lips peered her sharp fangs.

“I thought there was nothing I could do, but I have another chance. Such happy things do not often happen. I can act or not as I see fit. Much better that than having the matter settled entirely behind one’s back, don’t you think?”

There were two kinds of strength. One was the strength that came with having something to protect. The other was the strength of having nothing to lose.

“You seem strangely bold,” he teased, the breath puffing whitely from his mouth.

“’Tis because I’ve come upon a wonderful excuse. Regardless of the outcome, I’ll have participated in whatever happens. There’s a certain comfort in that. It might be even more important than whether things go well or not.”

Following her implication to its conclusion suggested that even if she lost out in the end, she might do so without suffering. But when someone seemed to be concealing something and then voiced such a sentiment aloud, one could hardly fail to extend a hand to them.

To lose was one thing, but the challenge of losing with grace was a far more difficult one.

“I must live a good long while yet. I need the hearth of a good excuse to sleep through the cold nights. Something to hold while I sleep that suffices to gaze at when I wake.”

It was a difficult thing to meet such words with a smile, yet he had to. Her fearlessness made it seem as though she was proposing they go and steal the great treasures of the world.

“I can’t stay with you forever. I can only do so much to aid you. But what I can do for you I will.”

She stood there in the snow, the morning sunlight shining down on her small back.

What she wanted to know was not what his stated goal was, but rather what he could actually accomplish. Her heart was a bit too tender to desire passionate proclamations of his willingness to make any effort or risk any danger.

Perhaps their mutual willingness to simply join hands and walk together without going to any great effort only proved that he was getting older. The smile that appeared on her face was a happy one.

“Well, then, perhaps I will use breakfast as an excuse to see just how far you’ll go for me, eh?” Her joke signaled the end of their melancholy conversation. She returned to his side with light, bounding steps, then clung flirtatiously to his arm.

“Just make sure you don’t eat so much that this breakfast becomes your last.”

Even under the best circumstances, the cost of feeding her was no joke. But what had to be taken even more seriously than said cost was the speed of her wit.

“Aye. After all, you love me so much you can hardly bear it—If I ate enough to please you, my belly would surely burst.”

The words that came out of her mouth were a fortress, and if he dared to counterattack, snakes would come slithering out of the grass that surrounded it. Surrender was his only option. He shrugged. “I have no particular desire to kill you.”

“Mm.” Her red-tinged amber eyes took in the sight of the snow-covered abbey and then closed. “’Tis well. I’d hate to die by your generosity.”

Lawrence wondered privately if dawn was the coldest time of day as a reminder from God that it would only become warmer from here.

CHAPTER ONE

I’ll call on you later.

Merchants rarely had the luxury of interpreting those words literally. Sometimes it meant perhaps if we’re lucky, we’ll talk, but it could easily be a year or even two before coincidence allowed the promise to be made good upon.

However, when the words came from someone connected to a large economic alliance, they could be taken at face value. As Lawrence and company were on their way back from the great abbey of Brondel in the middle of the snowy plains, bound for the port where they would return to the mainland, they stopped at the same tavern they had used on the way in, and there they received a letter.

The letter came from Piasky, who had expended such effort during the turmoil surrounding the abbey, and it concerned that same abbey, which had attempted in vain to quickly reverse its own failing fortunes.

Long ago the abbey had produced many great saints, but it was tales of a certain holy relic that brought attention to it now.

The probability that the relic was pagan in nature was very high, as was the probability that it was real.

From the perspective of a traveling merchant like Lawrence, such stories belonged in taverns, told over wine. And yet by strange circumstance here he was, reading secret communications from the Ruvik Alliance concerning the great monastery. The Ruvik Alliance, which owned countless trading ships and held sway over even bishops and kings!

He had to laugh.

And yet upon reflection, Lawrence realized that no matter how vast their influence, such alliances were still made of people. And if during one’s travels one met a kindred spirit in even a lowly servant, it was worthy of a feast.

The meetings and encounters of humanity were arranged by God, so any number of mysterious things might happen. After all, by any normal standards, the idea of having the companion he did was utterly laughable, but there she was, standing next to him and peering curiously at the letter.

Her hair was chestnut, her chin fine. Her red-tinged amber eyes and her elegant lips. And if her noble beauty was rare, still rarer were the wolf ears beneath her hood. Lawrence’s serendipitous traveling companion Holo was neither noble nor human. Her true form was that of a great wolf large enough to devour a man in a single bite, a being from the age of spirits, where she once dwelled within the wheat and ensured its bountiful harvest.

Of course, she herself hated such grandiose descriptions, and as she impatiently swatted his legs with her swishing tail in an effort to hurry his letter reading, the term charming seemed much more appropriate than awe inspiring.

“When you’re done reading, give it back.” He held the letter out to Holo, who snatched it away. The holy relic that Brondel Abbey was said to have purchased was a bone from a great wolf, one far from ordinary—a god. In fact, it was a fake, and the letter described the details of its purchase.

Holo had thought the bone might have belonged to one of her pack.

The relief that came when such worries were dispelled was brief. Since at Brondel Abbey, Lawrence had heard another fell rumor surrounding the wolf bone. The letter offered a clue regarding exactly that.

“Still, to think such a great abbey might be swindled so!” said the third member of their party, Col, as he tended the fire.

He looked younger even than Holo appeared, owing partially to the scrawniness brought on by hard, hungry travel. Either that or it was thanks to his humility, which kept him ever humble despite his clever mind.

Lawrence faced the fire. “Who do you suppose would buy a rusty sword?” This was the sort of thing his master had often done when Lawrence was an apprentice—judging the ability of others by asking them an absurd question.

“Er…someone without any…money?”

“Yes. But who else?”

“Someone with too much money—’tis it not so?” said Holo before Col could answer. Evidently she had finished reading the letter.

She sat down between Col and Lawrence and handed the letter to Col. The young, wandering scholar was himself from a pagan town in the north and believed in the gods’ existence and so was seeking the truth of the wolf bone for himself.

“Indeed. Those with too much money would buy a rusty sword. Even if it’s entirely lost its edge. Such a sword’s value is determined in other ways.”

“So you’re saying that the abbey didn’t care whether the bone was real or not?”

The reward for his excellent answer was a pat on the head from Holo. He seemed entirely happy, without so much as a trace of embarrassment. So happy, in fact, that even the giver of his reward seemed pleased.

“What’s more important than who was deceived by whom is whether or not the abbey was able to give the bone sufficient value. And it seems they were.”

At Lawrence’s words, Col looked down at the letter he had been handed. There was written the only faint possibility of salvation that remained for the abbey.

“It says they were approached by an overseas merchant company with an offer to buy…that’s that company, right?”

Col was speaking of the commotion that surrounded the narwhal back in the port town of Kerube. The Jean Company had been at the center of things and had secretly set aside funds to buy the wolf bone.

“They wanted to sell the bone to the Jean Company for a fortune, then whether or not it was real, feign ignorance. But it didn’t work.”

“And none of that has anything to do with us,” said Holo as she roasted a bit of cheese over the fire on a small stick. She popped the bubbling stuff into her mouth, and beneath her hood, her ears pricked up.

“Quite so. Our attention is elsewhere.”

At Lawrence’s words, Col returned his gaze to the letter. Had it contained anything truly important, it would not be in its conveyance of the facts. Baseless impressions could be very valuable from time to time.

When it came to information that was truly valuable for trading, it would not be had in the letter’s contents. What was valuable was that which no one knew, and such secrets came from wild conjecture, not hard proof.

“‘It seems such trades have been made all over in recent years. I suspect those at their center have a very different information network than we possess. It seems to be the north has become unstable. God’s protection be upon us all. Piasky.’”

Holo finished chewing her cheese and tossed the stick into the fire. “That agrees with what we heard from old Huskins, does it not?”

Holo generally avoided using people’s names, but the name she deigned to utter was that of the true identity of the legendary golden sheep of Brondel Abbey. But it was not simply because Huskins was a similar being to her that she spoke his name. She was an obstinate wisewolf, and if she did not respect someone, she would not spare them more than a this or a that.

“The Jean Company that approached the abbey to purchase the bone was originally a branch of the Debau Company, Mr. Huskins told me. He said that the situation in the north was going to change dramatically based on the interference of the company that owns mines in the region—and that’s none other than the Debau Company, a group that has a web of influence quite separate from the Ruvik Alliance.”

Huskins had secretly created a home for himself and his kind on the lands of Brondel Abbey in the kingdom of Winfiel. His comrades wandered the land, occasionally returning to exchange tales of what they had heard and seen. Huskins had given Lawrence some of that information—including something regarding their destination, Holo’s homelands of Yoitsu, reportedly destroyed centuries earlier.

“So the real bone is already in the hands of the Debau Company?”

“That is a possibility. If it’s already on the market, it’s even likelier.”

Lawrence took the letter back from Col and then tore it up slowly and deliberately.

“Ah—”

Ignoring Col’s exclamation and look of shock, Lawrence finished tearing the letter into small pieces and then tossed them into the fire.

“A single paper letter is easily destroyed in water or fire. You use parchment if you want to avoid that, but then disposing of it becomes difficult. Easily destroyed paper is used when writing something secret.”

The paper quickly became ash, borne up on the air warmed by the campfire.

“So, what shall we do then, eh?” asked Holo. Both she and Col watched the ash rise into the air, but only Col’s gaze was truly on the ash. Holo’s amber eyes were gazing at something else.

“Mr. Piasky’s letter reinforces what Mr. Huskins told us of the north. Two separate information sources have brought us a similar story. We can safely assume it to be mostly true.”

“So this so-and-so company is really driving people from their homes in order to dig up the mountains?”

Col’s gaze snapped down from the flying ash.

“Hence the possibility that they’re frantically gathering up holy relics without much concern for their authenticity, Mr. Huskins said. Their goal is clear—if you’re going to rely upon force of arms, there’s no stronger ally than the Church. The Debau Company will certainly try to get the Church on its side. It will let them talk about their annexing the land containing the mines in much more favorable terms.”

The campfire crackled quietly.

“A holy war, then. To take back God’s land from pagan hands.”

Holy relics belonged to the religious world. So the wolf bone that Lawrence and company were chasing, too, would probably be used in Church propaganda, Lawrence thought. If it was from a pagan god, then they would deliberately desecrate it, and when divine punishment failed to arrive, call it proof of the Church’s superiority. Holo had said that no matter how strong her kind might be, they couldn’t bite once they’d become bones.

In regions where the breath of the pagan gods still clearly lingered, the reaction would be profound. And if the Debau Company was ready to instigate violence in service of their mining plans, their plans had nothing to do with religious faith and everything to do with profit.

Just as Huskins had so aptly said, whenever the old gods were driven from their forests and mountains, merchants were always behind it. They were not even bothering to hide themselves this time.

“This is probably because so many were put in a bind with the cancellation of the northern campaign. No one wants war where they live, but if it’s a far-off land, it’s a welcome event. Foodstuffs and supplies fly off the shelves, and the mercenaries that plague fields and villages are all occupied far away. If things go well, nobles that went off to war return rich with plunder, which may then be shared.”

“And so much the better if the land attacked is a pagan one, eh?” said Holo.

Holo’s homeland of Yoitsu had been destroyed centuries earlier, so the story went. But the forests and rivers she knew should still be there, along with a sunny hilltop somewhere where she could nap. In that sense, her homelands should still exist.

But the search for gold, silver, or other metals would literally change the landscape. Trees would be felled, rivers dammed. In but a moment, it would become a place she had never seen before.

“Er—” Col politely raised his hand, seemingly on the verge of tears. He was another of the few who were taking action to protect their homes from the Church’s oppression. “Do we know where, um, the attack will happen?”

“We do not. However,” said Lawrence, giving the boy a comforting smile, “we can prepare. The larger the operation, the more impossible it becomes to hide. Even if we can’t stop things entirely, we can turn the spearpoint away from the places we want to protect.”

Col nodded, a pained look on his face. He bit his lower lip.

Twenty years hence, it was possible that Col would have sufficient influence within the Church to turn that spearpoint himself. But that was still merely hypothetical.

Holo reached out to stroke Col’s cheek and then gave it a pinch. When she spoke, it was to Lawrence. “What will we need?”

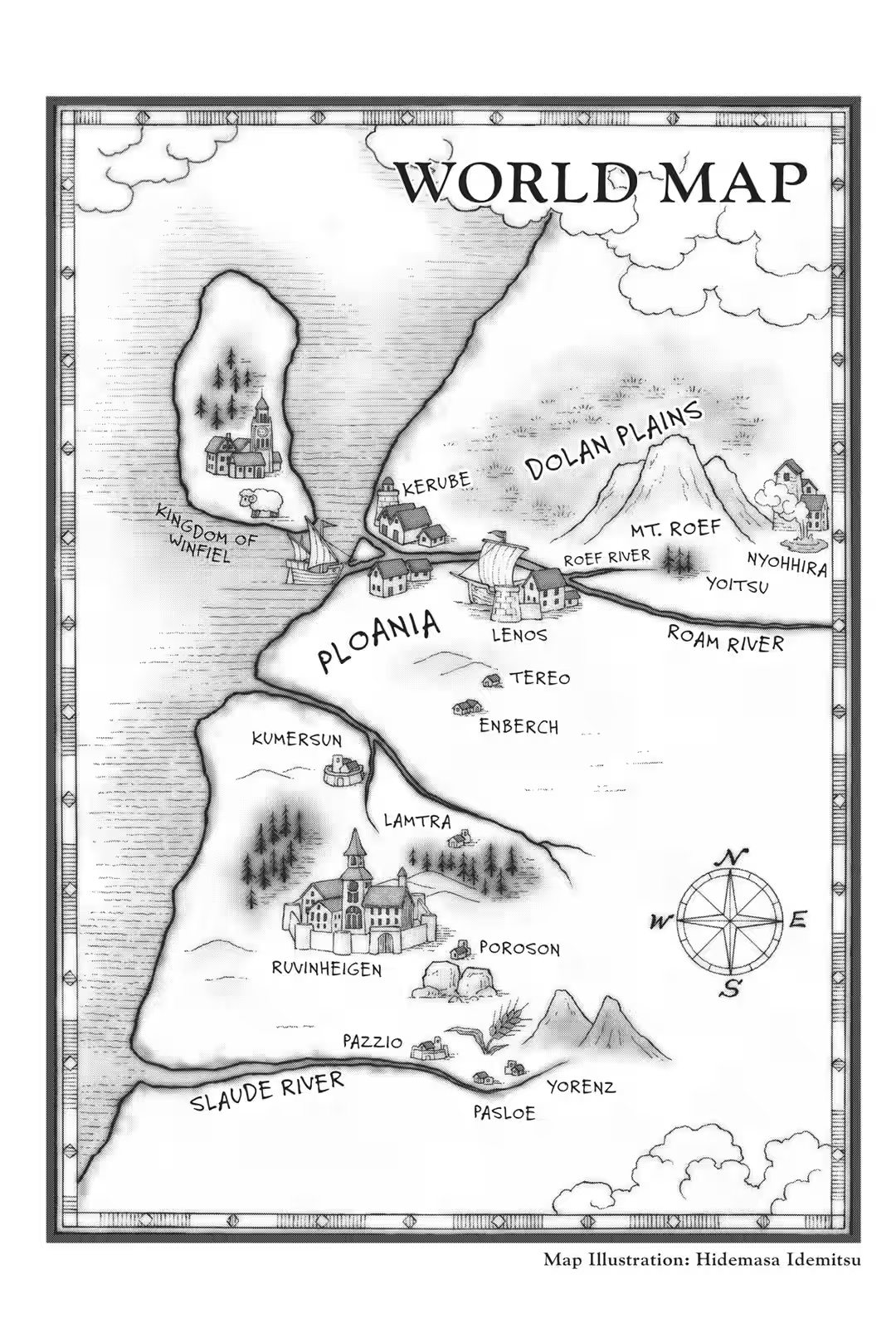

“First, an accurate map of the northlands. Having learned a place-name, it’ll do us no good if we don’t know where that place actually is, and we won’t know where war is spreading, either. And while it’s not exactly a minor detail, we may find more news of the wolf bone in the process.”

Holo nodded and took a deep breath.

“That’s why I had Mr. Huskins give me the name of someone who could give us news of the north and draw us a proper map. And since he knows the truth about the wolf among us, I expect the introduction will be a good one,” said Lawrence jokingly.

Holo only sniffed, unamused, while the guileless Col nodded. This was what Lawrence had told Holo when they’d greeted the morning at the abbey.

He could gather information and take her back to her homelands, as he had first promised, but any heroics that might follow—such as ruining the Debau Company’s plans—were beyond his ability to guarantee.

Their opponent was a great trading company that controlled the mines of the north. It was a world that would take more than mere money to navigate. Getting Brondel Abbey to sell a holy relic to the Jean Company was only one small part of the Debau Company’s goal.

When he had learned this from Huskins, before feelings of resentment set in, Lawrence had been simply amazed at the ridiculous breadth of the world.

His own influence had its limits, and traveling merchants were generally a powerless lot. But Holo did not blame him for that, so Lawrence felt no shame.

He would do what he could. And what he could do, he would do to the absolute best of his ability.

“In any case, we’ll return to Kerube. There we’ll meet with a certain merchant.”

Kerube had been consumed with the narwhal disturbance. Holo put the question to him with a look of distaste. “Not to that runt that caused you so much fuss surely?”

“You mean Kieman? No. A merchant who’s one of Huskins’s friends.”

At Lawrence’s answer, Holo’s expression turned still sourer. “We’re relying on the power of sheep yet again…?”

“It’s not a shepherd this time. That’s got to be some sort of improvement.”

Holo was not a high-handed noblewoman. It was true she did possess a certain measure of pride, but it was a childlike vanity and stubbornness that she often employed, which she herself would readily admit.

Lawrence did not expect a reply to his statement, but he got one.

“If not a shepherd, what then?”

Lawrence’s answer was simple. “An art seller.”

Just as rivers divide one nation from another, the climates on opposite sides of even a narrow sea channel can be very different. Different enough that letters exchanged across it often give rise to jokes that summer and winter come at opposite times.

While the port town of Kerube was still cold, it was not icily so. But if one crossed the river that flowed through the town and headed north, the scenery would soon turn a pure white that was not so very different from Winfiel. The world was a strange place.

“So will we disembark on the north side? Or the south?” asked Holo with tired eyes from underneath the blanket as they rode within the ship. She had started drinking wine not long before, insisting that it was too cold not to.

Lawrence put his hand on Holo’s head and idly brushed her bangs aside before answering. “The south. The livelier side.”

The town of Kerube was divided down the middle by a river. On the north side lived the original inhabitants of the town, while the south was full of more recently arrived merchants. The livelier half was the south, where the merchants were.

“Mmm. I suppose…I’ll be able to look forward to a tasty dinner, then,” Holo said, yawning as she spoke, then smacking her lips. Lawrence wondered what sort of feast she saw at the end of her gaze.

Thinking of the contents of his coin purse, he replied with a bit of a jab, “Joking aside, how many sheep might we have had?”

Huskins was employed as a shepherd at Brondel Abbey, and he had offered over and over to quietly give them several head of fine sheep.

“Mm…’twould have been no small trouble to bring them with us.”

“I never would have thought you’d play the realist.”

Sheep were costly, and those chosen by the golden sheep Huskins himself would surely leave nothing to be desired. But they had not accepted his offer for exactly the reason Holo had just stated.

When Lawrence turned Huskins down, Holo had clearly been displeased, but even then she had understood.

“I can manage that much, at least,” said Holo. “After all, our pack is already…” Using their belongings for a pillow, Holo lay under a blanket. Lawrence’s hand was on her head, and from underneath it she looked up at him mischievously. She did not finish her sentence, though, either out of kindness or having decided it was more trouble than it was worth.

“How about you sleep quietly, like Col?”

Col was afraid of traveling by ship, and after a swallow of wine had slept soundly by Lawrence’s other side.

At Lawrence’s words, Holo slowly closed her eyes and answered, “I don’t fear ships, but wine. If I could but sleep I could escape the fear, but to do that I fear I need to drink more.”

An old joke, one often directed at the clergy, who were prohibited from drinking. What made Holo so frightening was not that she knew the joke, but that she was able to seem like she truly meant it.

“I fear the cost of food, so I’ve nothing to drink but my tears,” said Lawrence.

There was no reply from the perhaps unamused Holo.

Some time later, the ship arrived as planned in Kerube.

By the time Lawrence woke Col, and grumbling, Holo got to her feet, Lawrence and company were the only ones left in the ship’s hold.

“Ngh…whew. ’Tis been but a few days, but this feels strangely nostalgic,” said Holo once they left the ship and found themselves standing in the south side of the town. Having been swept up in the chaos that threatened to divide the town in two, perhaps it had left a deeper-than-usual impression on them.

“Could be because the snowy scenery of Winfiel is so different from things here. But you’re right.” Lawrence divided their luggage between himself and Col and then held the hem of Holo’s cloak down to keep her tail from showing as she stretched. “This is the first time we’ve returned to a town we’ve already visited.”

“Mm? Oh, aye. Now that you mention it, ’tis so.”

After the sad state of Winfiel, it was even easier to appreciate the constant hustle and bustle of Kerube. For all those who made their lives by trade, a lively marketplace was best.

“Indeed, it does feel as though we’ve been traveling together for a terribly long time.”

“Hmm?”

Holo narrowed her eyes and looked around, then clasped her hands behind her and started to walk forward. “And every time we enter a new town, something worth laughing about for fifty years seems to happen.”

Something about her form seemed terribly lonely, and Lawrence was sure it was not just his imagination. If Holo was to laugh at these memories fifty years from now, he would not be by her side to join her.

“…”

When Lawrence failed to muster any response, Holo turned around to face him. “So then, shall we add another happy memory to our travels?”

Lawrence looked past Holo, where beneath the eaves of a shop, eels were being fried in oil.

Having left their things at a trading house, Lawrence went to Kieman, who had written him an introduction letter, to tell him in an innocuous way about recent events there.

Kieman, amused, listened all the while and, in lieu of a reply, held out a letter sent to the trading company some days earlier from a town farther south that was famous for its furs.

The letter contained but a single sentence: “We profited.” Lawrence was sure that if he put his nose to the paper, he would catch the scent of a wolf—but that wolf was not Holo.

He did not need to ask who the letter was from.

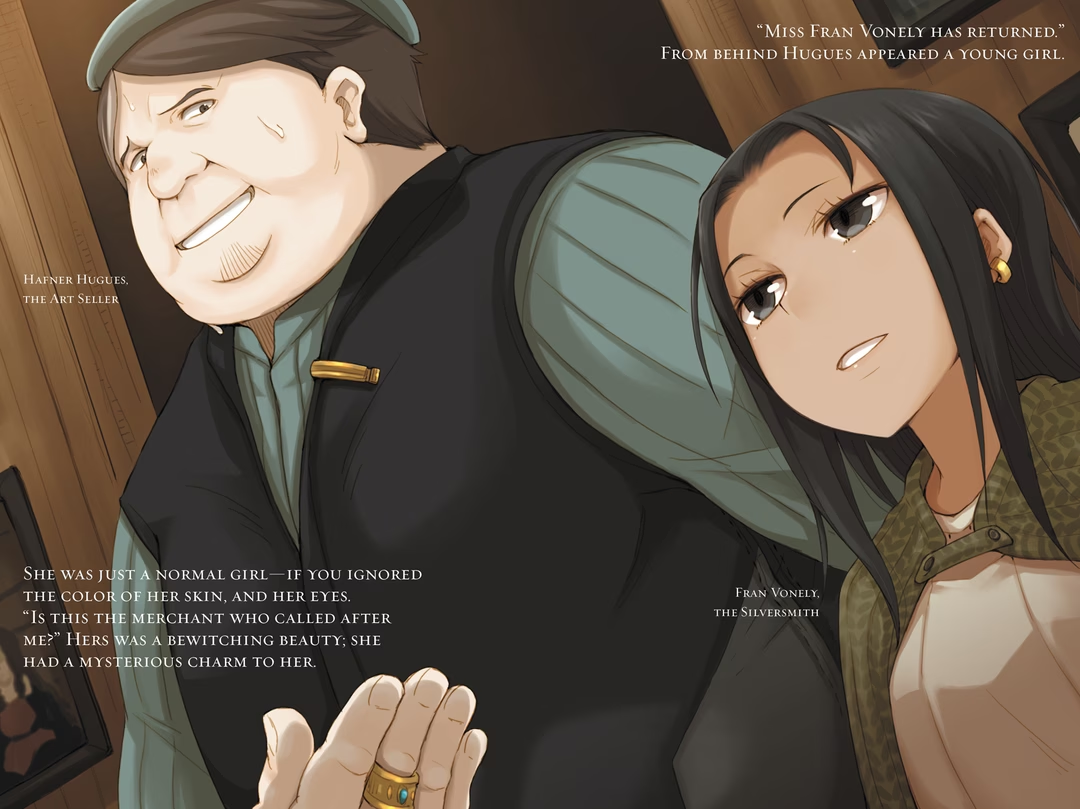

“An art seller? Oh, perhaps you mean the Hugues Company.”

“Yes, I’d like to meet with Hafner Hugues.”

“If you simply head out the front entrance of the trading house and down the street, it will be on your right. They’ve a signboard with a picture of a ram’s horn hanging from the eaves, so they’re hard to miss.”

Lawrence smiled wryly at that detail—it was a bold sign to have, given that Hugues was one of Huskins’s kind.

“Still, it’s unusual that you would have business with the Hugues Company.”

Art was the purview of the wealthy and powerful, so it was rare for a traveling merchant like Lawrence to walk into an art seller’s company. As someone concerned with the reputation of the Rowen Trade Guild, Kieman was undoubtedly worried that Lawrence was again involved in something strange.

Lawrence probably could not sweep those worries away, but Kieman might know something useful, so Lawrence replied even as he held no particular expectations. “I hope to meet with a silversmith named Fran Vonely.”

Huskins had given him the name, and when Kieman heard it, his face was the very image of surprise.

“Do you know her?” Lawrence asked.

Kieman rubbed his face to erase the shock, then smiled faintly. “She’s famous. Or perhaps I should say notorious.”

What was that supposed to mean? Lawrence quickly looked around, wordlessly pressing Kieman to continue.

“It’s her clientele.”

Kieman’s eyes in that moment seemed to evidence more worry for Lawrence than they did concern about speaking ill of Fran Vonely.

“She’s celebrated for having such high patrons for such a young silversmith, but those patrons are all newly wealthy, and most of them have dark shadows in their pasts. And she won’t hear questions about where she apprenticed or who her master was. She’s very mysterious.”

Kieman’s information sources were like a spiderweb over the land, so his words were undoubtedly true.

What sort of person was she?

As Lawrence mused, Kieman said one last thing. “I think you’d be better off avoiding her.”

Within their organization, the difference between Kieman and Lawrence was like that between heaven and earth. If Kieman made a suggestion, it was meant as an order. And yet as Kieman’s pen danced over his ledger book, he murmured one last thing.

“Ah, seems I’ve been thinking aloud again.” A deliberate smile flickered across his features; it seemed he really did intend the warning as well-meaning advice.

Lawrence bowed to Kieman and then hurried to leave the trading house, where Holo and Col awaited him.

As he went, Kieman offered one final statement without looking up from his ledger. “Let me know when you’ve profit to divide.”

It seemed presumptive to think of Kieman as a friend, but they did share a friendly sort of tie, Lawrence felt. “But of course,” he said with a smile before putting the trading house behind him.

“Did things go well?” asked a worried Col. And no wonder—normally it would be distasteful to even meet the eye of someone whose greed had caused the trouble for them that Kieman’s had.

But in all the world, none were so ready to put grudges behind them and drink with onetime enemies as merchants were.

Lawrence patted Col on the head. “Seems they got a letter. ‘We profited,’ it said.”

Col’s face lit up; he had always liked and worried about Eve. And Eve, too, seemed to be fond of Col.

The only displeased one was Holo.

“I only pray this doesn’t mean that more misfortune awaits us.”

She was no doubt referring both to Eve—who had once actually tried to kill Lawrence—as well as Fran Vonely and the warning from Kieman.

As far as they had heard, she would be a troublesome person to deal with.

Lawrence gave Holo a look that said, “You’re hardly one to talk.”

Holo sniffed in irritation. “So where are these art sellers to be found?” The obviousness of her ill temper made clear she was not really unhappy at all. When Lawrence started walking, she immediately followed.

Once she saw the signboard that hung from the eaves of the Hugues Company, she fought back a wry smile. “I’m not sure whether they’re gutless or bold.”

“Probably for the same reason you see so many eagles on the nobility’s family crests,” said Lawrence, opening the shop’s door, which was simply made but finely carved and had likely cost a good sum. Immediately his nose was hit by the smell of paint.

The shop was on the small side for one on such a busy street, but Lawrence was immediately struck by how profitable it probably was. There was no small number of paintings hanging on every wall, and they all had one thing in common.

They were large.

In general, it was neither the subject nor the artist of a painting that determined its price. Most of a painting’s price was in the paint itself, and so it was the size and color quality of a piece that decided its value.

Every painting in this little shop was large and had been rendered in many vivid colors. They were undoubtedly worth a significant amount.

“Ho…”

Some of the paintings depicted God or the Holy Mother, while others showed saints in reclusion, in mountains and forests, in caves and by ponds. In each case, the backgrounds seemed more prominent than the subjects, as though the artists had cared more about them than God or the Holy Mother.

“Perhaps no one’s home.”

Holo seemed impressed, and her breath quickened. Col was silent. Lawrence ignored them and went farther into the shop—but not before turning around and giving Holo a stern warning. “Don’t touch the paintings.”

Holo’s cheeks immediately puffed out in irritation at being scolded like a child, but she did indeed have a finger raised and pointed at the face of one of the paintings. If she touched it and left a mark, they would all have to beat a hasty retreat.

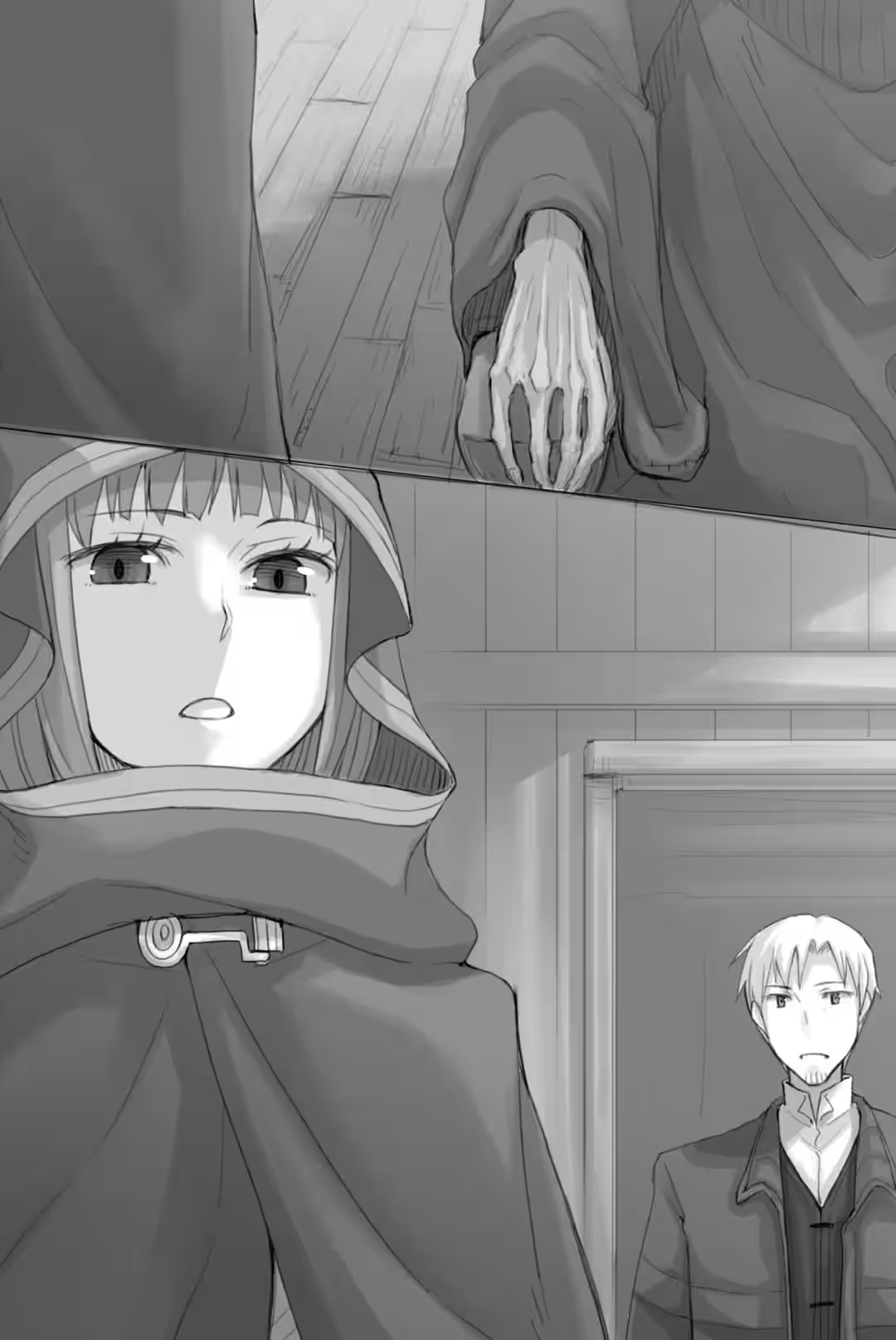

“Excuse me! Is anyone here?” Lawrence called out into the shop, which elicited the slam of a closing door. There seemed to be someone in the storeroom.

Lawrence heard a muffled reply and gazed at one of the paintings on the wall as he waited for the shopkeeper to emerge. It was a painting of a group of pilgrims on their journey. They were walking alongside a river, on the opposite side of which was a lush forest and grand mountain range.

The man who finally emerged from the back of the shop looked more like a pig than a sheep. “Yes, yes, how may I help you?”

A glance at the flat cap on his head called to mind a clergyman, but he was dressed in fine merchant’s clothes.

“I’m here to see Mr. Hafner Hugues.”

“Oh? Well, I’m Hafner. So…how might I be of assistance?”

Lawrence was obviously a traveling merchant, and his companions were equally obvious as a nun and a rescued street urchin. None of them were the usual clientele for an art seller who catered to the wealthy.

“Actually, I was sent by Mr. Huskins from Brondel Abbey…”

That was as far as Lawrence got.

Hugues’s piglike nose twitched, and his eyes were fixed in a corner of the room.

Holo noticed his gaze and looked up from a picture of the Holy Mother holding an apple.

Holo was small, but she was still a wolf.

“Ah…ah…ah…”

“Her name is Holo,” said Lawrence, smiling brilliantly at the terrified Hugues.

But Hugues did not have the wherewithal to listen. He seemed ready to flee but unable to make his legs move, and he gazed at Holo as though poleaxed.

It was Holo who moved.

Without so much as a sigh, she walked right up to him. “I don’t suppose you have any apples like the one in that painting?”

When surrounded by a pack of wild dogs in the forest, about the only thing one can do is pull out a piece of jerky and throw it as far as possible.

The effect was immediate. Hugues nodded so quickly his fleshy cheeks jiggled before he immediately disappeared into the rear of the shop.

“He’s more pig than sheep, I’d say,” mused Holo as she watched him go.

Holo reached without hesitation for an apple from the wooden bowl full of them that was produced. Despite being the master of this shop, Hugues seemed stuck as he stood in the corner.

“Mr. Hugues.”

His large body tried to shrink into itself at the sound of Lawrence’s voice. Lawrence tried to offer him a chair, no longer certain just who was the master and who was the customer here.

“We heard of this place from Mr. Huskins, you see.”

Hugues’s hand was busy wiping the sweat from his brow as he stared at the apples, but hearing this he froze. He looked up at Lawrence desperately, as though begging for mercy.

Munching away on her apple, Holo chose that moment to interject. “Now he…was a tough fellow.” She looked at Hugues with one teasing eye. It was not that he was a sheep that annoyed her so, but his simple cowardice.

And yet she probably would have been annoyed in a different way if he had not shown fear. Wolves are complicated creatures.

“Tough. Sinewy, you know.”

“He was a sturdy fellow, indeed,” added Lawrence to Holo’s unnecessary words.

“Wh-what did you do…no, what did you want with him?” Had he possessed a bit more courage, perhaps he would have asked, “What did you do to him?”

But he surely saw the fangs in Holo’s mouth as she chewed her apple. Wolves and sheep are in inherent conflict. Since time immemorial, one has been the eater and the other the eaten, and so would it continue.

“We listened to his tale of what his kind had done at the abbey. It was a grand tale, too. And then we gave him some assistance.”

“…Why did he—why did he send you to me?”

“We are looking for someone who knows the northlands.”

Strength seemed to be returning gradually to Hugues’s eyes. As an art seller, he had unquestionably been successful, so he was certainly superior to Lawrence, a human and a traveling merchant.

“Ah…yes. In that case…,” Hugues said, but stumbled over the however he wanted to say next and looked at Holo meaningfully.

Holo had devoured five or six apples and licked her fingers as though her hunger had been temporarily sated. She spoke only after she had finished licking her index and ring fingers all the way down to their base. “That one, Huskins, he had some backbone. He knew the way of things.”

“…”

Hugues said nothing, not even taking a breath as he looked at Holo.

“What I mean is, he made sure to properly repay his debt to us. But as to whether it’ll truly be paid…” She glanced at him. “…That’ll depend on your cooperation.”

“That’s…” Hugues swallowed as though trying to choke something down and then continued, “Of course…if that’s what he wants, then…”

“Mm.” Holo gave Lawrence’s arm a light poke, as though to say, “It’s up to you now.”

“So then, Mr. Hugues. We were hoping you would make an introduction for us.”

“Ah…yes, indeed, this company deals in art, and many artists travel widely. So…”

“Yes, we heard the name of a certain silversmith from Mr. Huskins.”

In that moment, Hugues’s face finally belonged to a proper art seller. And in the same moment, Holo transformed from a girl blithely eating apples into a wolf.

“Mr. Huskins gave us the name Fran Vonely.”

Wrinkles appeared on Hugues’s soft forehead. He had the peculiar facial expression common to all merchants when their most profitable secret is discovered. But Hugues had been a merchant for a long time, and as such, he knew all too well of treating any visitors who were sent by someone as important as Huskins.

“I am…aware of her.”

“I hear she is a remarkable silversmith.”

Hugues gave a pained nod in response to Lawrence’s statement. “She makes her living with painting, but her true trade is as a silversmith. I don’t know how she’s managed it, but she’s close to many important figures, and to a one they’re infatuated with her skill…especially those who’ve made their fortunes by the spear and shield, if you…”

For an art dealer like Hugues, she would be like the golden goose. He could’ve gone on at length.

Lawrence cleared his throat. “Could you introduce us to her?”

No one wanted to let a competitor get close to their golden goose. Lawrence certainly understood the feeling—particularly when it was an unknown traveling merchant, a poverty-stricken urchin boy, and a wolf spirit. He could hardly be blamed for imagining himself being devoured headfirst.

It was obvious that Hugues was weighing Huskins’s debt, his own profit, and his personal safety against each other.

Holo then put a finger on that scale. “Yoitsu.”

“Huh?” Hugues looked at her.

“Yoitsu. ’Tis an old name. Few still remember it. And those who remember where it is are still fewer.”

Perhaps Hugues’s mouth was dry, as he was now constantly trying to swallow.

“I seek my homelands. Yoitsu. So, what say you? Have you heard of it?”

Holo was behaving poorly, it was true. But it was clear that she had become tired of keeping up appearances for their own sake.

“If you know, I want you to tell me. Just look at me.”

Holo seemed small, and her head was bowed. If her tail had been bared, it surely would have been drooping between her legs.

“Ah…er, well…”

It was enough to surprise even Lawrence, and Hugues was well past surprise and on into shock. He finally stood from his chair and flapped his mouth as though trying to say something to Lawrence and Col.

It was true that engaging in a real negotiation would have been bothersome, but there seemed to be a basic change in Holo’s attitude.

In Winfiel, she had learned just how naive she truly was, and this from a sheep, an animal she had taken every opportunity to deride. And here she was not making high-handed demands, but simply asking for information.

And while Hugues might not have been a courageous man, he was a generous one.

“P-please look up. If the old one’s sent you…no, rather, if you’ll go to such humbling lengths for me, then, come—I, too, was born as a sheep. And I will aid you. So please…”

Raise your head.

At these last words, Holo slowly looked up and smiled. And perhaps it was strange to think it of someone who had lived as many centuries as Holo had, but it still seemed to Lawrence that her smile was just a bit more grown-up.

CHAPTER TWO

Hugues offered warmed wine instead of apples. “It’ll warm you. Please, help yourself.”

Lawrence gave his thanks and brought it to his lips, and Holo did likewise. He doubted she would like it and stole a glance at her. Col was the only one who had been given warm goat’s milk, and seeing Holo eye him enviously was rather entertaining.

“Now then, you want to know about Fran Vonely, the silversmith, do you?”

“Yes.”

Lawrence got the feeling that Hugues still had something left to say, and soon he came to a conclusion and replied, “She’s in town right now as a matter of fact.”

Holo smiled an obviously unfriendly smile, which Lawrence had to admit he understood. Still, it was no surprise that Hugues was trying to protect his asset.

Lawrence lightly patted Holo’s knee before turning his attention back to Hugues. “Doing painting or smithing, I suppose?”

“No. She often travels here or there saying she’s making preparations for just that, but just when I was thinking I hadn’t heard from her in some time, she comes wandering in, saying she’s heard tell of a certain legend.”

“A legend?” said Lawrence, as though to make sure he had heard correctly, which made Hugues nod.

“Something about a village known as Taussig. It’s up next to a long, wide mountain range in the north. The mountains are tall, the forests deep, and she’s come in pursuit of a legend regarding a lake in the area, she said.”

Hearing the words mountain, forest, and lake, Lawrence looked at his companion.

But Holo did not look back, and instead his eyes met Col’s, who was sitting on the other side of her.

“Mr. Hugues, do you know anything about this legend?”

“Certainly, I’ve heard tell of it. As I’m sure you’re aware, we have our own information sources, and to a certain degree we can tell whether such things are real or not…”

“So you’re saying there’s a good chance it’s a fake?”

Hugues nodded. “But she’s a stubborn person. Once she’s decided on a shape for a silver piece, she won’t budge—although many people find such vehemence to have a certain charm to it…”

“So she won’t have time to draw us a map?”

“Perhaps not. Though…”

“Though…?” Lawrence prompted, which made Hugues reply with regret in his voice.

“It’s true that she often journeys into the north in search of subjects for her silversmithing, and I imagine that she’s become more familiar with the old names of places there than old Huskins or myself are, since she’s the only one actually going there.”

Lawrence nodded and urged Hugues to continue. What he had said so far did not answer Lawrence’s question.

“So, yes. But I don’t know if she’ll simply draw you a map if asked to. I had to work very hard in order to establish a relationship with her, so…” Hugues wiped the sweat from his face. Assuming it was not an act on his part, Fran Vonely was indeed a difficult person to get along with.

“What? ’Twill be simply done,” Holo said, casually baring her fangs at the rattled Hugues. All they had to do was threaten her—was that the joke?

Hugues smiled, but not out of amusement at the jest. Crafters were a famously stubborn lot. There were stories of legendary blacksmiths who had been unwilling, been driven to the verge of poverty, licking rust from their anvil to stave off starvation, rather than forge a sword they did not want to forge.

It would be foolhardy of Lawrence to just show up one day and ask her to draw them a map of the northlands.

“I understand entirely,” said Lawrence. “But would you be able to put in a good word for us?”

Hugues nearly fell forward at Lawrence’s question. Perhaps it made Lawrence’s firm resolve all too clear.

“She—she’s a very difficult individual, you see…”

It would be difficult to convince her to meet someone she did not already know. Lawrence contemplated the problem.

Hugues was torn between maintaining his relationship with a particular silversmith or doing right by Huskins, who kept the haven for sheep spirits like Hugues. In weighing one against the other, he was leaning toward the silversmith.

Had they not gotten whatever sign from Huskins they needed in order to obtain Hugues’s cooperation? Or was he just not a very duty-bound person?

Or—was Fran Vonely a silversmith of such ability?

It was not beyond Lawrence’s ability to reason this out. Neither was it difficult for an art seller of Hugues’s ability to guess at what Lawrence was thinking during his short silence.

If Hugues displeased Vonely, then he would be facing something even more dangerous than Holo.

In a pleadingly serious tone, Hugues began to speak.

“The reason I’m so loathe to displease her is related to my trade. But it’s not about money.”

Trade was always carried out to seek money. Lawrence’s curious gaze fell upon Hugues, who seemed to gather his resolve. He stood and walked over to one of the paintings on the way.

“The place in this painting was once called Dira long ago.”

It was one of the largest paintings in the room and depicted a jagged, craggy landscape. Standing before a bare cliff was a single hermit, both hands raised to the heavens as though in prayer. It seemed to be a depiction of the legend of Dira’s patron saint.

Such paintings were common. But as far as Lawrence knew, pieces where the setting was more of a focus than the subject were unusual.

As the thought occurred to him, Hugues said something unexpected. “This is my homeland.”

“—!” Lawrence felt Holo stiffen beside him.

“But long ago it was a fertile, productive place. Without any of these rocks. That cliff…is a claw mark.”

Holo’s voice was a hoarse whisper. “Of the Moon-Hunting Bear?”

“Yes. It is something that my kind will never forget. These paintings were created with the help of individuals like Miss Vonely. It has been decades now. For the sake of my kind and those similar to me, I collect and deal in such pieces, pieces that show the homes we were forced to abandon or the disaster that made returning home impossible. It would be a lie to suggest that I have not profited in doing so, but that is a secondary concern.”

Hugues gazed into the scene of the painting as though through a great window.

“And even the landscape of this painting is now no more. I hear that veins of gold were discovered there…It’s ironic, actually. The guide I hired in order to have this piece made found the gold. And even if that hadn’t happened, wind and water would wear the land away until it’s entirely different. The paintings in the other room and the paintings hanging in churches and manors, too, mostly show landscapes that have disappeared or are in the process of disappearing. And the paintings themselves will not last forever.”

Hugues touched the frame of one of the pieces, gazing at it for a while after he had finished speaking.

This was a place where tiny pieces of vanishing worlds were stored for safekeeping. The passage of time might seem slow to humans, but to his kind it was surely too fast. Their memories of the past were all that remained, and the gap between it and the present grew ever larger.

Hugues suddenly looked back at Lawrence with a troubled smile. His gaze was probably directed at Holo, but Lawrence did not turn to check. He knew that doing so would surely hurt Holo’s feelings.

The only one who could speak to Holo of this was Hugues, who had lived as long as she had.

“If possible, I would like very much to help you. This place does not exist only for we sheep. My customers have included deer and hares, foxes and fowl as well.”

Lawrence heard the sound of rustling cloth as Holo shifted. He would not ask what she had done.

“However, Fran Vonely’s knowledge and skill are irreplaceable. She has a perfect memory, never forgetting anything she’s seen even once, and a sense of purpose she holds more dear than her own life. She is utterly dedicated to capturing the landscape in her art, and I cannot afford to lose her cooperation. There is no time.”

The energy in Hugues’s eyes was not something that one would see in someone who worked solely for his own profit. The evidence of the life that he and his kind had lived was inexorably disappearing, and he was engaged in the work of trying to preserve a record.

Lawrence dwelled on Hugues’s last words. “There is no time”—did he mean that the landscape was vanishing too quickly?

“There’s no time?”

“Yes. We must hurry. There are a multitude of places I hope Miss Vonely will paint, but her lifetime is limited. I think about it often—if only she could live as long as we.”

Lawrence doubted he was the only one to make a surprised sound at this revelation. He had assumed that Fran Vonely was a special being, like Holo and Hugues. That led him to consider the obvious next question: If time was such a concern, why didn’t he and his kind simply do the paintings themselves?

“Like you, I’m meant to be a merchant,” said Hugues.

Lawrence realized that he had been scratching his head in confusion, and Hugues had likely guessed at what he was thinking.

Hugues looked down, then sighed, smiling. He looked at the paintings on the walls and narrowed his eyes. “I understand what you want to say. And in all honestly, we did once take up the brush…and those comrades of mine who went north and east and captured the old landscapes in the south, landscapes that are now long gone…those comrades of mine were not immortal.”

Holo was the wolf spirit who lived in the wheat, and Lawrence remembered her words—that if the wheat in which she lived disappeared, she too would be gone. And she herself had a natural life span.

But Lawrence could not imagine that Hugues was talking about natural life spans.

Hugues’s quiet eyes regarded him. They were the deep, placid eyes of a wise and ancient man.

“They took up their brushes and traveled abroad, carefully observing the state of the world out of a deep sense of duty. And what they found were forests cleared, rivers dammed and changed, and mountains dug up and scarred. Eventually they could stand it no longer and traded their brushes for swords.”

Lawrence had heard this story before. He glanced at Col, who listened raptly to Hugues’s tale.

“But they were outnumbered. One was burned by the Church, another crushed by an army. One was so mortified by his own powerlessness that he…well. Few remain even as memories, having vanished like so much sea-foam. Humans, they…ah, apologies.”

“Not at all,” Lawrence answered, at which Hugues displayed a sad smile.

“Humans have amassed great power. Control of the world has been theirs for a long time now, and our age has passed. Those unwilling to admit that have one by one fallen in battle and now exist only as legends on parchment. And even those parchments are crumbling, mice nibbled and moth eaten. We are what remains: sheep, in the human sense of sheep. None of us, myself included, have the courage to hold a brush. The bravest of us were the first to fall…It was a terrible cruelty.”

Lawrence understood all too well why Hugues was more concerned with Fran Vonely, a human, over his fellow sheep Huskins or Holo the wolf. Hugues and his fellows had surely not revealed their true nature to her.

If so, there were not many ways they could keep her close. To have her create paintings for them, they would bow down before her, avoid any offense, and hear any demand, no matter how unreasonable.

Even admitting her existence to Lawrence was clearly a great compromise on Hugues’s part.

“It is indeed cruel,” said Holo, sipping the sour wine Lawrence was sure she did not like. “So that is why you were so upset upon seeing me, was it?”

Lawrence looked at Holo, and Col did likewise.

While birds and foxes had visited the sheep, perhaps a wolf never had. Wolves had fangs, claws, and the courage to use them. They would have been the first to turn to violence.

And they would have been the first to die.

Hugues looked evenly back at Holo and then slowly nodded. “Yes. Even so.”

“Heh. But ’tis well. I would have been sadder to learn of the opposite.”

It was because such courage suited her that Holo had earned the name Wisewolf. It was in this moment that Hugues ceased to seem fearful of her.

“…I envy such strength. For my part, I’ve often wondered if I’m to live so long, why I couldn’t have been born as a stone or tree instead.”

At the end of the conversation, Holo began to speak without any inhibition. “Heh. I cannot say I feel the same. Were I a stone or tree, I could hardly travel with these two.”

Hugues smiled. “Indeed. Life in the world of humans can be rather enjoyable.”

“Mm. They’re an amusing lot.”

Yet Lawrence could not help but feel that it surely had not been an accident that the wine they were offered was not very sweet.

Gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, lead, brass, stone.

The phrase gems hidden in the earth was a common one, but sometimes it could be hard to tell what was valuable and what was not.

As Lawrence and company waited for Fran to return from her wandering about town, Hugues showed them around his storeroom. It contained not just paintings but a wealth of fine crafts and ornaments that had been sold off to Hugues alongside those paintings.

“There are many fakes here, but…ah, here’s a bar meant for holding down scrolls. Mm, looks like it’s only gold plated, though. Ah yes, here! What do you make of this one, eh?”

Hafner Hugues, master of the storehouse, seemed not to know exactly what it contained, as he weighed the gold bar in his hand and made his pronouncement.

Hugues had told Holo about Fran because Holo was a being similar to himself, but he was still a sheep spirit and a merchant as well. He had to get some value from this transaction.

He led Holo and Col to the back of the storehouse, as they wanted to know whether he had any paintings of Holo’s homeland of Yoitsu, but as he did so, he kept a close eye on Lawrence. A traveling merchant who wandered from nation to nation did not have much purchasing power, but he made up for that in knowledge and fresh information. No doubt Hugues wanted to know if any of the dusty old pieces in his storeroom were unexpectedly valuable. Lawrence felt like a pig trained to sniff for truffles.

It was true that demand varied from town to town—in one town, anything with a wolf motif would sell, while in another, the color of gold would be so coveted that even gold-plated items would fly off the shelves. Given the occasion, Lawrence was only too happy to spill everything he had heard about towns whose conditions might be good.

Such a town might as well be drunk. Absurd items would sell on the spot, and given the amount of junk in Hugues’s storeroom, it was like a golden trash barrel.

“Well, that’s about the size of it.”

“I see, I see. I’m deeply grateful, yes. While I do hear stories from all over while I sit in my shop here, most of my visitors aren’t walking the path of trade, so I collect little information that’s useful in business.”

Even as he spoke, Hugues took notes with a quill pen in the margins of an old bill of receipt. Assuming his high spirits were not a ruse, he seemed to think they would lead him to a healthy profit.

Holo would scowl if Hugues had asked her, but Lawrence was a merchant.

As he considered such thoughts, his eyes were drawn by a single item in the piles of junk.

“…Is this…?”

“Oh, so this is where I left that old thing.”

Lawrence pulled the item out from between two wooden crates, and Hugues reached for it, smiling merrily.

Lawrence could not begin to imagine what the thing was for. He handed it to Hugues. It was a golden apple; Holo would surely laugh to see it.

“What in the world is this used for?”

“Oh, it’s one of those—you use it to warm your hands.”

“Your hands?”

In response, Hugues handed the apple back to Lawrence, who noticed that it was indeed a bit warmer than it had been a moment earlier.

“It’s for merchants who want to show off their wealth a bit. You can heat it by the fireplace or have your apprentice warm it with his skin, then use it to warm your hands as you do your writing. Though anybody who dares use it outside when traveling in the winter will find their hands sticking to it.”

Hugues was quite right. Still, Lawrence had no trouble imagining Holo curling her body around the trinket while riding in the wagon, like a hen protecting her egg. He found himself thinking it might be rather useful, but then quickly snapped out of it and shook his head.

This was no time to be distracted by such silly items.

Lawrence returned the apple to Hugues.

“Still, thank you ever so much for the information,” said a pleased Hugues, who had nearly blackened the margins of the bill of receipt with notes, careful not to leave as much as a single detail out.

“Not at all. Thank you.”

“By all means, when you’re finished, feel free to linger. You’re most welcome here.” Hugues sounded like an ordinary merchant now.

Lawrence smiled, nodded, and shook his hand.

“Though it seems Master Col and Miss Holo are still looking at the paintings.” Hugues had to exert himself to bring his round body to his feet, and he then peered farther into the back of the storeroom.

Holo was flipping through a stand of paintings one by one, chattering with Col about this and that.

Hugues fell suddenly silent as he watched her. Lawrence had a good guess at what he was thinking about.

“Might I ask how you’re all related?” It was a reasonable thing to wonder about.

Holo should have overheard, but she gave no evidence of it.

Lawrence decided that there was no reason to hide it, so he answered as he walked over. “My trading route generally covered lands farther south. I happened to meet Holo at one of my stops there.”

“I see.”

“Holo had been asked a favor by a friend long ago—that she would guarantee bountiful harvests of the wheat in a certain town. But over time the village forgot about her, and she decided to return home. My wagon happened to be passing by, and she simply hopped in and stowed away.”

Hugues smiled, amused, but there was a coolly calculating quality that showed through. Holo’s story was not irrelevant to his own experience.

“But it had been some several centuries since she’d left her homelands, and so she doesn’t know where they are. So we’ve been traveling here and there in search of them. We met Col on the way. He’s from a town in the north called Pinu.”

“Oh, Pinu?” Hugues’s eyes widened in surprise, and he looked over his shoulder at Holo and Col. “That’s quite far away. Ah…but I see now why old Huskins would have told you of Fran Vonely.”

Lawrence gave Huskins a deliberate smile. There was nothing amusing about the story, but if he failed to tell it with a smile, Holo seemed likely to be angry.

“The northlands are a place of invasion and conquest. The place-names are always changing. It might be that I do know this Yoitsu of yours; I simply know it by a different name.”

Lawrence nodded but was shocked at what Hugues said next.

“When you said you wanted a map of the north, I thought for sure you were involved with the conflict up there.” Hugues was speaking in jest, but seeing Lawrence’s reaction, he, too, was stunned. “Ah…er…you’re not, are you?”

“Are you referring to the events surrounding the Debau Company? So the rumors are true, are they?”

No doubt Hugues collected information along with paintings. And this was the destination of the river that flowed right through the Debau Company’s front door.

“Er, no, I…if you want to know whether it’s true, the fact is that I have no good evidence. It’s a place constantly awash in unpleasant rumors.”

“What do you yourself believe, Mr. Hugues?”

Hugues’s troubled expression was that of a man whose joke had been taken seriously. He seemed to give up on trying to escape and reluctantly opened his mouth. “The simple truth is that…I have no interest in it.”

Lawrence thought he must have misheard. “You have no interest?”

“That’s right. More than a few of us are simply plugging our ears and closing our eyes to the tale, just as we did with the Moon-Hunting Bear. They’ll mine what they can mine, and when they’re done, they’ll leave. In any case, scenery is not eternal. Though the landscape might change completely, the land itself will not simply disappear from the earth, so…”

Even a placid sheep, who only occasionally looked up from its grass eating to regard the scenery around it with its black eyes, could see the way of the world.

It would be easy to curse Hugues for being a coward. But there was a certain truth to his thinking, and he could hardly be blamed for his realistic outlook.

One saw all sorts of things during travel.

Villages beset by mercenaries, towns suffering bitter feuds between landlords. There was nothing to be gained in opposition, and they were powerless to begin with. The only answer was to hold still and hope the storm would pass.

“That’s why I’ve never tried to learn anything more about it. I’m not strong like old Huskins, and if I knew more, it would only worry me. Just as it worries you and Miss Holo and young Col.”

Hugues smiled fractionally at this small joke, a signal that he was hoping to end the discussion of this particular topic.

It was true—the more one knew, the more one wanted to know, and the more detailed the knowledge, the stronger the urge to interfere. It was difficult to argue with the wisdom of someone who had endured cataclysms.

Lawrence had no right to disturb Hugues’s life, and Holo would surely feel the same way. “I apologize for asking.”

“Not at all. I’m sorry I couldn’t be of any help. So then, will you be returning to your room?” inquired Hugues.

Lawrence looked at Holo, who raised her head and shook it “no,” then pointed to Col. The boy was busily looking through a stack of paintings. Evidently they still had searching left to do.

“I’ll be returning on my own.”

“I see. Might I offer you something warm to drink in the parlor?”

As a merchant, Lawrence was surprised at these words. This storeroom contained a great many valuable paintings, as well as examples of gold- and silversmithing. To leave perfect strangers unattended in such a room was an act of significant courage, Lawrence reflexively thought. Hugues noticed this and smiled.

“If she wanted to steal from me, it would be faster for her to simply bite my head off. And anyway, we forest dwellers don’t lie.”

It would have sounded as if he was trying to flatter Holo, but perhaps that was reading too much into it.

Lawrence bowed his head politely. “Ah, my apologies.”

Hugues chatted with Lawrence for a while before retreating to the rear of his shop to work.

Lawrence sat in the room waiting for Fran, reading through the travel account of a merchant who claimed to have journeyed the world over and found a city of gold in the Far East. But just like the information that Lawrence had sought from Hugues, the knowledge that could be gathered in a trip around the world would be incredibly valuable if true, and therefore making it public would be the height of idiocy. In other words, the travel account was merely nonsense, but it was amusing nonsense.

Just as Lawrence found himself laughing at the absurdity of one of the more improbable details, a golden something flew through the space between his eye and the book and landed in his lap.

He looked up in surprise, and there was Holo, looking as though she had dropped something. His eyes were next drawn to the dropped object in his lap—it was the golden apple he had been so amused to discover in the storeroom.

“Was it not tasty?” He picked the apple up. It was warm.

Size-wise it seemed just about a fit for Holo’s hand, he thought, whereupon that same hand snatched it away from him.

“You humans do love your gold. Though ’twould be a bother if everything turned to gold.”

Too much of a good thing, went the old saying. But Lawrence was a merchant. “In that case, find something that’s not gold, and sell it high.”

Holo sniffed and then sat down beside him, looking displeased. She did not groom her tail; she simply toyed with the golden apple in her hands.

“Where’s Col?” Lawrence asked, which made Holo tilt her head.

Her ears were flattened, which did not suggest anything good about her mood. She had probably left him in the storeroom. It was a rare state of events, and Lawrence could not imagine many possibilities.

“Couldn’t find anything, eh?” Any paintings of Yoitsu, or its region, or any landscape that Holo remembered.

No doubt she had thought that with so many paintings, surely at least one of them would hold what she sought.

Her disappointment would not have been so great if she had thought from the beginning that nothing would turn up. What stung was having hopes dashed.

Worse, they had surely found many landscapes that Col recognized.

“Mm.” Holo held the golden apple in both hands and nodded faintly.

“That just means you’ve still something to look forward to, eh?” Lawrence knew he would rouse her anger by saying so, and indeed, her ears pricked up.

But that did not last long. The strength slowly slipped from her, and the words came tumbling out of her mouth like water from an uncorked bottle. “Is it…wrong of me?”

“Wrong?” Lawrence repeated, at which Holo nodded.

“Like those sheep, Hugues said. Most of them plugged their ears and shut their eyes…”

Lawrence looked away from Holo momentarily and closed the book. It was a delightful, beautifully bound volume. No doubt the name of the raconteur merchant responsible would be remembered for centuries.

“You mean about wanting to get involved after hearing the truth?” asked Lawrence, which Holo nodded at.

Holo seemed cold and calculating but was quite hot-blooded, and whenever she saw someone suffering or in trouble, she wanted to help. If humans were to assemble and march upon the forests and mounts, ravaging the land and killing the animals, she would want to help the resistance even if the land weren’t Yoitsu.

And while the outcome might well be recorded in legend and song, victory was surely impossible—because if it was possible, someone else would already have won it.

“I may say this or that, but the truth is that I think of myself as special,” said Holo, sounding faintly amused, perhaps to cover her embarrassment. “I can get through most things simply by showing my fangs. I can draw out the way of things. That’s what I thought. But…”

When Lawrence held out his arm, Holo glanced at him with a look of hollow amusement pasted onto her face and then took it, wrapping it around herself like a muffler and clinging to him.

“There were no paintings there of the land I knew. What does that mean?”

Each of the pieces had either been commissioned by a specific buyer or stored away in anticipation of someone from the region appearing and recognizing the landscape. It was not hard, therefore, to come to this conclusion: There were no paintings of Yoitsu because there was no one from Yoitsu to order them. It was easy to imagine her wolf comrades leaving on an eternal journey.

And what was the basis for this?

No doubt many of them, having confidence in their own teeth and claws, chose to fight. And even if they had likely fled from the Moon-Hunting Bear, the world was abundant with absurdities. If they had been able to find weapons, they would have risen up and fought—somewhere.

The ones who ran away from everything, who instead of taking up arms simply fled, would have been called cowards at first. But it was those cowards whose roots still clung to the earth, even now.

“Plugging one’s ears and closing one’s eyes for fear of the truth? ’Tis all I can do to laugh at such foolishness. But who is the master of this shop? Who is it who still knows many of his old friends? Who is it who even now still works to offer comfort to his kind? Compared with that…” The nails of Holo’s small hand dug into Lawrence’s arm. “…What am I doing?”

She was not crying.

Holo was not sad. She was ashamed.

The raging river of time had changed the world, and she and her kind had stood on the shore, not only powerless, but their very existence suddenly in doubt.

It was more than enough reason for Holo to gnash her teeth.

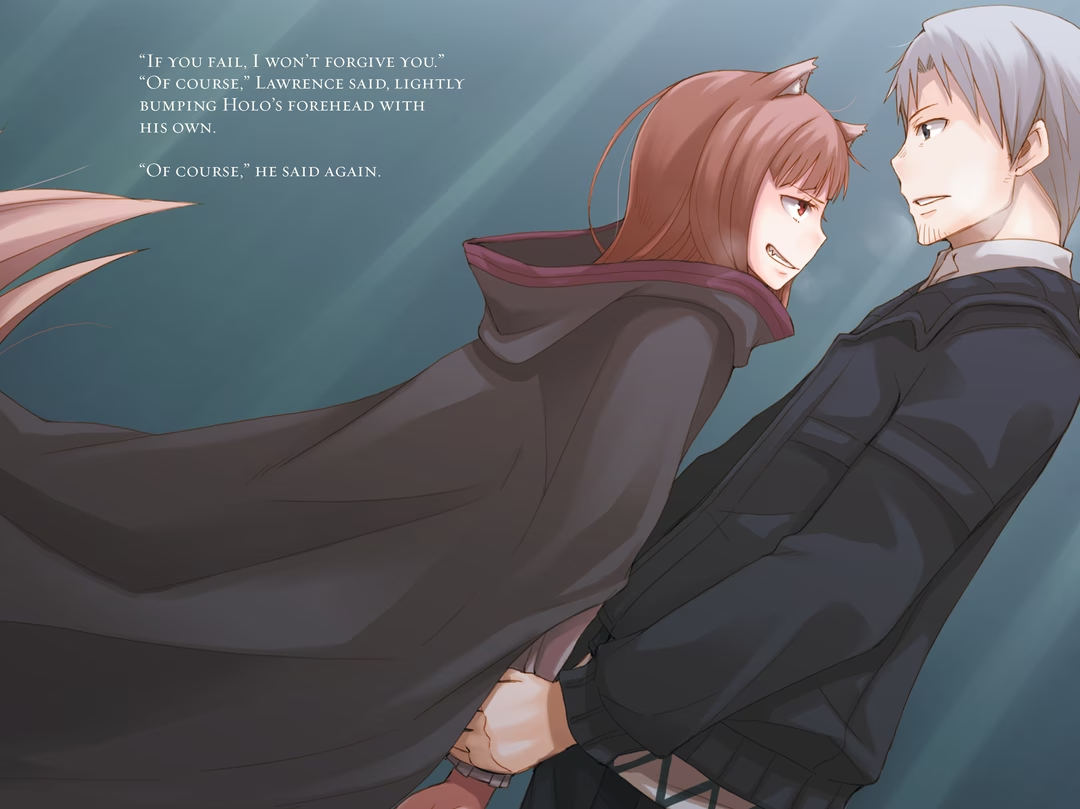

Lawrence put more strength into his embrace, drawing Holo in.

“Nobody knows what the right thing to do is.” Holo’s head smelled faintly of dust, perhaps because of the time she had spent in the storeroom. “You yourself have been prepared to put your life at risk for the sake of your principles. Am I wrong?”

Holo did not move for several moments.

“Just think about when you were buried in the ground. You’re Holo the Wisewolf, aren’t you?”

No doubt her comrades would be very pleased to know that Holo was thinking of them. But what would they think of her standing in front of their gravestone forever? Regret could mean struggling to turn back time, or it could mean swearing not to let the same thing happen again. The two meanings were very different.

Holo nodded. She was neither a child, nor a fool. And yet she still could not contain these emotions on her own.

“And I do know one thing,” said Lawrence, which made Holo’s ears prick up. He smiled, but not to cheer her up. “When you worry, so do I.”

When he had traveled alone, there had been no one to whom he would have uttered such words, nor anyone who would say them to him. When he would get involved in a risky trade, he would make boastful jokes about dying by the side of the road.

A dead friend was dead forever. But a living one existed only in the here and now.

“Fool,” she whispered, though it was by no means clear to whom. Perhaps both to herself and to Lawrence alike.

“Quite right,” said Lawrence. “So, the next thing to do is…?”

Holo’s voice caught in her throat.

She had not left Col alone in the storeroom simply because they had found only landscapes he recognized and none that she knew. Given Col’s disposition, if they were unable to find any paintings of Holo’s homeland, he would just keep looking.

And the more he looked, the heavier the weight of not finding anything became. Holo had not exactly taken her frustration out on him, but back in the storeroom, just how bad was Col feeling?

“I’ll go apologize,” said Holo.

“You do that,” said Lawrence paternally, and Holo broke free from his embrace and grinned a toothy grin.

Time could not be turned back and the correct choice was never obvious, so one had to try to enjoy the present, at least.

That was all Lawrence could say. The rest was up to Holo, he thought as he reopened the book.

“Miss Fran Vonely has returned.”

Before standing, Lawrence lightly tapped Holo’s knee. He looked back—she was wearing a bright smile, which was more than a little suspicious.

From behind Hugues, who was no doubt unused to having such a smile directed at him by a wolf so nearby, appeared a young girl.

She was not much taller than Col, which put her at about Holo’s height.

It was her appearance that made Lawrence’s face pale despite himself. She did not have Holo’s ears, nor horns like Huskins had. She was just a normal girl—if you ignored the color of her skin and her eyes.

“Is this the merchant who called after me?” Her voice was beautiful and clear and spoke of a good upbringing.

There are many forms of beauty in the world, but Lawrence had never before seen the sort that Fran possessed. Her hair and eyes were jet-black, and she had the dark brown skin common in the desert lands of the south. Hers was a bewitching beauty; she had a mysterious charm to her, the power of all who survived in the hellish deserts. It felt as though she would not quail, even if Holo took her wolf form then and there.

Lawrence swallowed and then finally managed to speak. “I am Kraft Lawrence.”

Fran Vonely smiled and gave a slow nod. She introduced herself. “I am Fran Vonely.”

“Shall we sit?” said the considerate Hugues, and Lawrence and company all took a seat.

Col clung to Holo’s clothing before finally managing to sit, seemingly dazed by Fran’s mysterious quality.

“So, what is it that you wished to ask me about?”

The people of the desert spoke a very different language, but Fran’s words were well practiced. Her pronunciation was careful and precise, and her education must have been a costly one.

They were said to be a difficult people, but perhaps such worries were unfounded, Lawrence thought behind his merchant’s smile. He told her his business. “Yes. We’re journeying in search of a certain place in the northlands. All we know is the ancient name of the place. We’ve heard that you’re very well-versed in the old tales, which is what brought us to visit this company.”

Fran’s face was serious as she listened to Lawrence. “And what is the name of the place?”

“Yoitsu.”

Fran narrowed her eyes at Lawrence’s answer. “That’s the old name of a rather remote area.”

“So you’re familiar with it?” Lawrence asked with emotion that was half-act, half-genuine. Fran was unmoved, like some stoic seer.

“I am aware of it, but few are able to draw maps of the north, making them extremely precious.”

“We would compensate you properly.” The moment Lawrence said it, Holo’s foot came down upon his, but it was too late.

Perhaps Holo had seen through to Fran’s true nature.

“Properly?” said Fran, surprised. Standing behind the chair in which Fran sat, Hugues covered his eyes. “In that case, fifty lumione ought to suffice.”

Hers was the attitude of an artisan inexperienced in the ways of negotiation. Lawrence asked himself if he had let his guard down so badly, but even if he had, there was no going back now. There was no way he was going to pay fifty lumione for a single map.

It was such a basic technique that it bordered on child’s play. Lawrence found himself at a loss for words, both because of his own foolishness and because of Fran’s unexpected boldness. But Holo was standing right there, so he had to say something. He was just about to when Fran’s clear voice rang out again.

“However, given the circumstances, I suppose I wouldn’t mind doing it for free.”

“Huh?” Lawrence could not help but let his mask slip completely, and he could feel Holo slump in annoyance.

It was hard to fix a cog once it had gone askew.

But it was not the foolish Lawrence to whom Fran directed her words. It was Holo. “I notice you’re dressed as a nun.”

“…My name is Holo.” Even Holo seemed surprised to be addressed, and she replied only after a short pause.

“Miss Holo, is it? Pleased to meet you. I am Fran Vonely.”

Holo, who called herself the wisewolf, was a calm huntress and never let excitement get the better of her during a hunt. “Have you something for me?”

“Yes. If you’re a nun, then I would ask a favor of you.”

It was Hugues who seemed flustered at these words, probably because he had realized Fran’s aim. He took a breath and seemed about to protest, but Fran raised her hand and silenced him. She was a prickly artist, indeed. The very image of one.

“So long as it’s in my power.”

Fran cocked her head rather than smiling. “It’s not so very difficult a thing. Miss Holo, Mr. Lawrence, and…”

“Ah, er—Col! My name’s Col.”

She nodded at Col. “Mr. Col, then.” Just what would she have them do? “With the three of you, it should be fine.”

Hugues looked at Lawrence with a desperate look that said, “Stop!”

Fran spoke. “I’d like your help in Taussig.”

“…Is that…?”

“Yes. I suppose you’ve heard from Mr. Hugues? It’s the reason I’m in this town. I would ask your assistance in learning more about the village’s legend.”

Lawrence was underwhelmed. It seemed so simple a thing. But from Hugues’s nervousness, it was not as simple as it sounded.

Despite his failure moments earlier, Lawrence prepared himself for the irritation he would earn from Fran when he begged more time to consider. But it was Holo who skipped past that entirely.

“And you’ll draw us a map if we assist you?” she asked.

“Yes. So long as you’ll gather information and verify its truth.”

Lawrence was not unaware of the reason for Holo’s smile. Fran was a clever girl—more than clever enough to inflame Holo’s love of competition.

Normally she would have laughed off such a vague request as “gather information and verify its truth,” demanding a clearer request. Depending on the circumstances, she was not above arm-twisting.

And yet without asking even one more question, Holo simply nodded. “It’s a promise, then.”

“My thanks.” Fran bowed her head, standing after she looked back up. She faced Hugues, who had tried so hard to get a word in and hold her up. “And the preparations for departure?”

“Ah, th-they’re all finished.”

“Very well. We’ll leave tomorrow. Mr. Lawrence, you can handle a wagon?”

Lawrence nodded, and though Fran seemed ready to continue speaking, he headed her off in a final effort to save some small amount of face. “Tomorrow should be fine.”

At this, Fran smiled faintly. Perhaps she found Lawrence’s attempt to puff himself up amusing. Her smile was that of an innocent maiden. Lawrence again regretted his misstep. It was surprisingly easy to manipulate an innocently and honestly stubborn person. What was truly difficult was someone who knew how to use her smile, which was why Lawrence was constantly burning his hands when dealing with Holo.

Had he known he would be facing someone who could deploy a smile like that at will, Lawrence would have prepared better. He had been too hasty in embracing the impression of her that Kieman and Hugues had given him.

“Mr. Hugues,” said Fran, causing Hugues’s round body to stiffen straight. “I’ll take my dinner in my room. I have preparations to attend to.”

“V-very well. Ah, er, but…”

“But?” She used the same smile Holo so often favored.