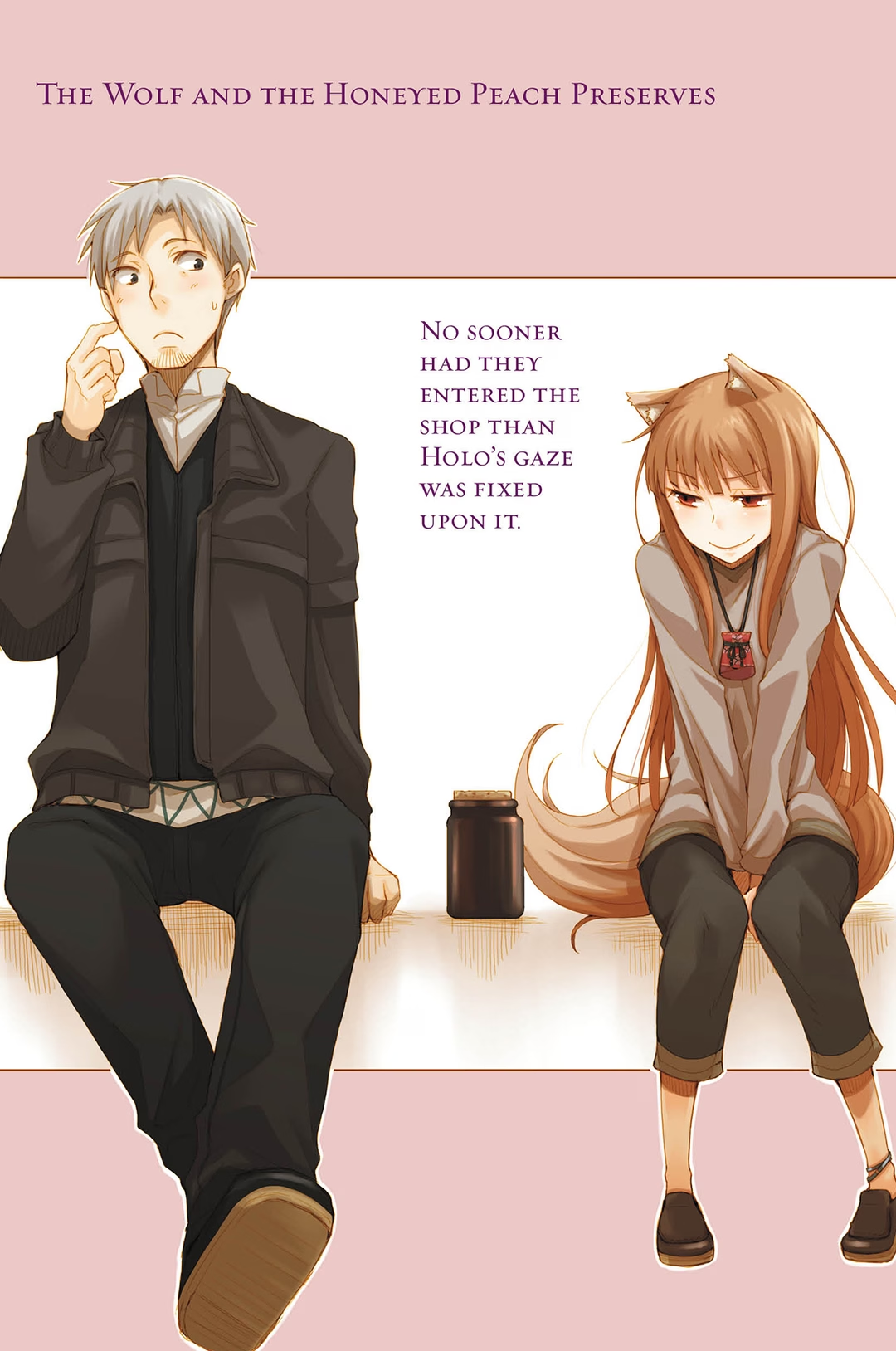

THE WOLF AND THE HONEYED PEACH PRESERVES

Even in a medium-small town, the luxuries of the location, which informed a decision to stay or push on, varied widely based on the town’s status as a trading hub.

In this one, there were mountains and forests nearby, from which flowed a beautiful river. And being blessed with fertile soil, the town fairly overflowed with agricultural bounty.

Hardy crops sold at a healthy price, and the resulting healthy profits led to a bountiful lifestyle, which in turn made bountiful harvests all the easier.

This town was a perfect exemplar of this virtuous cycle, and come winter, it brimmed with a variety of goods, along with merchants come to buy the same, travelers laying in provisions, and entertainers and priests alike looking to practice their arts on the abundant visitors.

The marketplace in such a town’s center was always raucous with this activity, as were the areas surrounding it filled with the hustle and bustle of townspeople plying their trades. Cobblers and tailors. Money changers running their businesses out of their wagons. Smiths selling travelers much-needed knives and swords—all were doing a flourishing business.

Look to the left or look to the right—everywhere were people, people, people.

Moreover, depending on the wind, delicious scents came wafting by—baked bread, frying fish—and one could hardly be blamed for being drawn to their sources, especially if days and days had been spent on the road in the cold, dry winter air, all the while eating nothing but stale bread and bad wine.

Perhaps unwilling to beg Lawrence to stop in front of every single stall they passed, Holo sat next to him in the wagon’s driver’s seat, clinging to his sleeve.

“Hare…catfish…roasted chestnuts…sausage…” She intoned every food they passed, like a child reciting words she had memorized.

If given leave to sample the goods as she pleased, Holo could surely spend a full gold coin in a mere three days.

The street was so crowded that Lawrence could not spare a sideways glance, but from Holo’s constant murmuring, he nonetheless had a good sense of what sorts of food could be had there. Being some distance from the sea, it seemed there was little in the way of fruit. Instead, meats of all kinds were abundant, and just as Lawrence felt an especially hard tug on his sleeve, he noticed they were passing a shop that was roasting a whole pig on a spit, slowly turning as oil was drizzled over it—a time-consuming and difficult task, but one that produced a fine product. The man doing the cooking, who seemed to be the shopkeeper, was stripped to the waist and sweating, despite the winter cold.

Children licking their fingers gathered around, as did travelers, all anticipating a tasty treat.

“…I want to eat something like that myself, once…just once,” said Holo wistfully, noticing Lawrence’s glance at the sight and evidently deciding it was an opportune moment to speak up.

Lawrence merely straightened and cleared his throat. “If my memory is to be trusted, I’m quite sure I treated you to a whole roasted piglet at one point.” Holo had devoured it entirely on her own, getting her hands, mouth, and even her hair covered in grease.

It was unlikely she had forgotten the experience, Lawrence thought, but Holo merely arranged herself in the driver’s seat.

“Such a thing would fill my belly for only so long.”

“…Perhaps, but there’s no way you could eat an entire roast pig.” It was not impossible that it weighed more than she did. Lawrence wondered if she would claim a readiness to assume her true form in order to manage the feat. Such would have been a serious case of misplaced priorities, but Holo only looked at Lawrence as though he were a very great fool.

“That is not what I am saying,” she said.

“Then what?” Lawrence asked. He truly did not understand the point at which Holo was angling.

“You don’t get it? You’re a merchant, yet you don’t understand the wishes of another?” A certain amount of pity colored her expression, which wounded his merchant’s pride more than being called a fool or a dunce possibly could.

“H-hang on.” Lawrence could not let this stand.

Pigs. Pork. A piglet being insufficient for her. Given the way she had just spoken, this was not about meat.

“Ah.”

“Oh?” Holo cocked her head, as though wondering whether he had figured it out.

“I suppose you didn’t get enough of the skin, then?”

“…Wha…?”

“It’s true, there’s less of it on a piglet. Still, well-roasted pork skin…it’s a luxury, that’s for certain. It’s crunchy, and when eaten with the meat, the oil spreads out in your mouth, and it’s even better with a good amount of salt…”

“Fwa!” Holo had been watching Lawrence with her mouth wide-open. She hastily wiped the drool from it and then looked away sullenly.

It was cruel talk to subject her to, after so many days of nothing but dry bread, salty pickled cabbage, and garlic. But from the way Holo coughed two or three times and wiped her mouth as though ridding it of an irritation, his guess had been off the mark.

The expression displayed under her hood was most displeased as well.

“What, that wasn’t it?”

“Not even close. Still…,” Holo said, wiping her mouth one more time and pulling her chin in. “That does sound rather tasty…”

“Well, you can’t get the skin unless you order a whole roast pig, and even with the two of us eating, too much meat would go to waste. I’ve even heard of nobles eating nothing but the skin and throwing the meat away, but…”

“Oh ho.” Holo was always serious when discussing food.

Lawrence smiled in spite of himself. “So,” he continued. “What could it be, then? You’re not satisfied with a piglet, which means…”

“Mm?”

“It’s not the skin, right? Sausage, then? Or boiled liver? That’s not my favorite, but liver can be quite popular.”

For a moment, Lawrence wondered if she meant she wanted to eat the item in question raw on the spot. She was a wolf, after all; but if they asked for a whole pig liver raw, they would instantly be suspected of being pagans, and the Church would be notified.

Still.

“Fool,” said Holo abruptly, as though to negate everything he was thinking. “You truly are a fool.”

“I don’t think someone who drools at every mention of food should be talking…,” he said, earning an immediate pinch to his thigh. Holo seemed determined to give him something to regret if he was going to lead her on with talk of food.

Just as Lawrence was reflecting on having teased her too much, Holo sneered at him. “Even I don’t have such a large stomach. A piglet is more than enough for me,” she grumbled.

So what was it, then? At this point, he could not very well ask her again or he’d have no cause to complain when she grabbed his face. Whenever Holo put a riddle to him, Lawrence could always solve it.

He thought back again, and the answer came to him quite readily.

Looking at Holo’s forward-facing, irritated profile, Lawrence laughed a quiet, defeated laugh. “So you want us to go together and have a meal we can’t possibly finish, is that it?”

Holo glanced at him, then smiled a bashful smile. It was enough to make Lawrence want to pick her up in his arms.

Wolves felt lonely so very easily, after all.

“You see, then?”

So, a meal tonight, too big for them to eat?

When Holo smiled, her fangs were slightly visible behind her lips. Lawrence got the feeling he had seen something he should not have and hastily looked ahead. He did not want to erase Holo’s smile, and her proposal was a very charming one.

However, such greed was the enemy of the merchant. An enjoyable meal came at a very unenjoyable price. Showing generosity like this was all well and good, but if it became a habit, it would soon be a problem.

Did this make him a miserly person? No, no—as a merchant, he was right.

Lawrence gripped the reins as he argued with himself, tightly enough for them to creak audibly. And then, he noticed something.

Beside him Holo was doubled over as she tried to restrain her laughter.

“…”

Her tail swished to and fro from the effort.

Irritated, Lawrence looked ahead, which made Holo burst out laughing. In the busy, bustling town, nobody noticed the laughter of one girl on a lone wagon.

So Lawrence decided not to notice it, either. No, indeed, he would not. He swore to himself in no uncertain terms that he would ignore her. And yet he was perfectly aware that this action would itself amuse her to no end.

Once Holo had finished her laughter at the expense of his tortured thought processes, she wiped the corners of her eyes—not her mouth. “My thanks for the meal!”

“You’re quite welcome,” Lawrence answered with sincerity.

“What? No rooms?”

The first floor of the inn was set up to serve light meals, and now, shortly before sunset, it was already raucous with activity.

A thick ledger book in one hand, the innkeeper scratched his head apologetically with his other. “There have just been so many people recently. My apologies, truly…”

“So it’ll be like this at the other inns, too?”

“Reckon it will. Times like this, it makes me wish the guild would loosen their rules a bit, but…”

The more people the owners could pack in, the more profit an inn stood to make, so profit was generally limited by the number of boarders. But if an inn was overcrowded, the building could collapse or disease could break out. Such conditions also made it easier for untoward professionals like thieves and fortune-tellers to mingle, so restrictions on the number of guests tended to be very strict.

For a guild member, defying the guild was like defying a king.

The innkeeper closed the thick ledger. “If you’d like some food, that much I can manage,” he offered remorsefully.

“We’ll come again later.”

The innkeeper nodded in lieu of a reply, perhaps too used to hearing such promises. Given how crowded it was, there was no chance a room would open up, so Lawrence returned to the wagon. He faced Holo and wordlessly shook his head.

Quite accustomed to travel herself, Holo nodded, as if to say she had expected as much. But under her hood, her features were showing a bit of strain.

Well versed in this scenario, she was no doubt already imagining the camp they would have to make at the outskirts of the town if they failed to find a room. To avoid that, the only option was to find a place to park the wagon and borrow some bedclothes—someplace like a stable, a trading company, or a church.

That would have been easier enough in a larger town, but in this middling one? It was hard to say.

If they did not find a place to park the wagon by the time the market closed and the sun set, they would just have to leave town again, as Holo was fearing. Lawrence would not have minded this so much had he been alone, but it was more troublesome now that Holo was with him.

Given the conditions, it was certain that many other travelers were preparing to do the same, and if it came to that, heavy drinking would certainly follow. A group of travelers weary of the asceticism forced on them by the journey could become rather rowdy once they began to drink. Lawrence did not even want to think about what could happen if a girl like Holo were added to the mix. Carousing was pleasant enough when times were good, but travel weariness like this called for care: weak wine slowly drunk, a hot meal, and a warm bed.

Holding on to that hope, Lawrence continued down the inn-lined street.

The second and third turned him away, and he arrived at the fourth just in time to see the people in front of him refused.

When he returned to the wagon, Holo seemed to have already given up and was loosening her bootlaces and belt in the wagon bed.

If he tried the fifth inn, the result would be the same surely.

Yet there was a great difference between having a roof and lacking one.

He pulled on the reins and wheeled the wagon about, threading a path through the hustle and bustle of people hurrying to finish the day’s work. In times like these, he envied those with a home to return to so much it angered him, and he felt a terrible misery at not being able to gain so much as a shabby inn’s room.

Perhaps noticing his frustration, Holo purposefully drew close to him. Pathetically, he felt himself relax all over. Despite it all, he did have Holo by his side.

Lawrence stroked her head through the hood, and she smiled, ticklish.

It was a single, simple moment in their travel. And then, just then—

“They’ll be ready to eat in a week, I hear,” came a voice from alongside the wagon.

On the crowded street, there was little difference between wagon-drawn traffic and walking, so it was easy to overhear other conversations. From the white dust on the men’s faces and arms, Lawrence inferred that they were bakers taking a break from their work.

They seemed to be talking about a shop somewhere along the street.

“Ah, you’re talking about what the young master of the Ohm Company said? Still, I’m surprised the boss would accept the work of someone like that. And then to order us to put it on the bread we bake? Absurd, I say!”

“Now, now. He pays us well and buys up the finest wheat bread we can bake. Even you like kneading the best wheat flour there is sometimes, eh?”

“Aye, I suppose…still…”

The one man seemed displeased with the item orders placed by a certain trading company’s young master. Bakers were a famously proud lot, even among craftsmen, so the order had to be something that went against his professional standards.

It took long, hard effort to become a craftsman, and then there was a final test to become a master—covering everything from the weighing of flour to the difficult techniques necessary for shaping the dough for rolls. Given all that, they seemed to be discussing the matter at hand in the light of exceptional professional pride.

But what was this bread being topped with?

Still leaning against Lawrence, Holo was very still, he could tell, as she listened carefully.

Lawrence followed the bakers’ gazes to their end, where the street was lined with the eaves of building after building.

There was a candlemaker, a tallow seller, a needle maker, a button maker. Of those, only the tallow seller sold anything edible, and Lawrence could not imagine they were baking bread topped with hunks of fat.

Then the answer came into his vision.

The apothecary’s shop.

One of the presumable bakers spoke, and everything was made clear. “Our bread’s at its tastiest when eaten alone! It’s a mistake to put such stuff on it. And anyway, it’s too expensive. Do the things turn into gold when preserved in honey? It’s absurd!”

“Ha-ha. You’re just complaining because you can’t afford it yourself?”

“L-like hell I am! I’ve no interest in the stuff! Honeyed peach preserves? Bah!”

Lawrence’s gaze flicked back to Holo, whose ears pricked up as though they had been poked with a needle. He would not have been surprised had they shot right through her hood.

Holo did not move. She was very, very still. But this was not some surprising display of self-control. It was quite the opposite.

Her tail lashed to and fro beneath her robe almost painfully, as though it had been lit on fire. Pride, reason, and gluttony all warred within her in a terrible tug-of-war.

The bakers continued their conversation about bread, and their quicker stride took them away from the wagon. Lawrence watched them go, then stole a sidelong glance at Holo beside him.

He wondered if it would be best to pretend nothing had happened.

The thought occurred to him for the merest instant, but the fact that Holo continued to simply sit there, not begging or pleading, was itself rather terrifying.

If he was truly a skilled negotiator, then this would be the time to prove it. If his opponent would just say something, it would give him the chance to refute or deflect it. But so long as there was nothing, he had no room to maneuver.

“S-seems like it’ll be cold tonight,” said Lawrence, scattering some conversational bait.

Holo said nothing.

This was serious.

Lawrence thought about the roasted pigskin. Anyone would be desperate, after making it all the way to a town only to be confronted with another cold night and a meal of bad bread and bad wine.

At the very least, the food situation could be remedied.

But honeyed peach preserves came at such a price. Would a single peach be ten trenni pieces? Or twenty?

It struck Lawrence as an absurd price, but it was true that he was capable of paying it. His coin purse could manage it, and there was Holo’s smile to consider.

Her silence was without her usual teasing and mischief.

In the end, Lawrence chose her.

“…I suppose it can’t be helped. Let’s visit the apothecary and see if we can’t find something to warm ourselves.”

Holo remained motionless. Motionless, yes, but her ears and tail quivered with a puppy’s glee.

The apothecary sold medicine, as one might expect, but also dealt in a variety of other goods.

In a town, the cobbler sold shoes and the tailor clothes, and generally the various guilds stayed in their own territories. Thus, the tailor could only also alter clothes, and a cobbler repair only shoes. A tallow seller could not sell bread, nor could a fishmonger sell meat.

By this logic, an apothecary ought to have only sold medicine, but it was common sense that offering a wider variety of goods brought in more customers, as any merchant knew perfectly well.

Thus, apothecaries would use all sorts of convoluted logic to pull in a great variety of goods. The products most likely to cause quarrels with other shops were none other than spices. Apothecaries would claim all sorts of spices were good for inducing sweat or lowering fevers, and thus qualified as medicine they could sell.

Extending that logic, anything good for one’s health also counted as medicine, and thus it was that apothecaries had become the chief dealers in honey.

The only other merchants who dealt in honey were the candlemakers, who sold beeswax candles.

It was difficult for traveling merchants—who dealt in anything and everything money could buy—to understand the turf wars between town merchants. But it was thanks to those turf wars that there was such an array of honeyed preserves lined up before them.

Plum, pear, raspberry, turnip, garlic, pork, beef, hare, mutton, carp, barracuda—these were just the ones that sprung to mind.

When preserving food, one could use salt, vinegar, ice—or honey. During this time of year, when the end of the long winter was yet far away, the prices of these preserves were at their highest. The contents of the bottles and barrels here, each labeled with a hasty scribble, would all fetch a good price.

Among all those lined-up goods, there was one that outshone all the rest. In the farthest corner of the shop behind the shopkeeper, enshrined on a shelf beside the pepper, saffron, and sugar, was an amber-colored bottle.

No sooner had they entered the shop than Holo’s gaze was fixed upon it.

“Welcome,” said the bearded shopkeeper, looking from Lawrence to Holo.

He noticed that Holo’s attention had been captured by something, so next he checked her manner of dress. One of his long eyebrows lifted minutely—the girl was well dressed, but not the man.

Whether or not he had concluded that even if they were here to shop, they would not be buying anything expensive, his tone was disinterested as he asked, “Are you looking for anything?”

“Something to warm us a bit. Ginger, perhaps, or…”

“Ginger’s on that shelf.”

The rest of Lawrence’s sentence was cut off in his throat, and there it vanished. If that’s all you’re here for, buy it and get out, the shopkeeper seemed to be saying. Lawrence did as he was told and looked over the ginger on the shelf, deciding on a honey-preserved variety. It was cheap but good for eating while huddled under blankets with nothing else to do.

But then he noticed Holo’s gaze on him—as though asking him, We’ve come to this place after all that talk, and after raising my expectations like this, you can’t just give up.

And of course, Lawrence had no intention of doing so.

It was too easy to buy Holo’s favor with food, and Holo herself found it tiresome on occasion. But when it came to honeyed peach preserves, things were different.

They had come up in conversation several times before, but as yet Lawrence had been unable to buy any. There was the matter of the high cost, of course, but more often than not they had simply been unavailable.

So perhaps that was why Holo’s enchantment with the food now wafted off of her in waves.

Lawrence walked past the vibrating Holo to the shopkeeper to have him portion out some of the ginger preserves and pay. He was obviously going to start bargaining, but—

“That’ll be ten ryut.”

Lawrence paid and wordlessly took the goods. Behind him he could feel Holo staring, stunned.

His eyes fixed upon the figure written on the label of the amber-colored bottle. One fruit for one lumione, or around thirty-five silver trenni.

For a moment he thought his eyes were mistaken, but no—that was indeed what was written there. The term peaches of gold was bandied about often enough, but even so—such a price!

After taking a goodly while to note what Lawrence was looking at, the shopkeeper spoke with a deliberately casual tone. “Ah, you’ve a good eye for quality. This year’s peaches were very sweet and firm as well. The honey is the finest from Baron Ludinhild’s forest. One lumione per fruit, and I’ve had many customers! Only three left, in fact. How about it?”

It was written on the man’s face that he knew Lawrence could not purchase such a thing. In a town like this, without connections to large trading companies or urban nobility, it was outrageous to put such a price on honeyed peach preserves. That he was treating his customers with such open contempt was proof of how confident he felt in his position.

But Lawrence had the confidence that came from having completed many trades in large towns. His hand moved toward his coin purse out of irritation at being treated like some novice peddler.

It was not a sudden prideful desire to conserve money that stopped him. Rather, it was a keen understanding of exactly how many coins were within that purse, keener than any god’s.

If he spent an entire lumione here, their travels might come to a premature end farther along the road. No merchant would be fool enough to keep their entire wealth on their person, so Lawrence was not carrying much on him at the moment.

Reality blocked the path to Holo’s smile. Realizing this, Lawrence shook his head. “Ha-ha. Too much for me.”

“Is that so? Well, come again if you change your mind.”

Lawrence turned around and left the shop, and Holo followed obediently behind him. She did not raise a single word of reproach, which was somehow worse.

He felt as though he were being stalked by a wolf in a dark forest, its footsteps matching his.

He had let her get her hopes up, and then in the end, he had not bought the item of her desire, which was much worse than simply pretending not to notice from the driver’s seat.

If he apologized first, it might lessen the wound, he thought; so steeling himself, he turned to her.

“…”

He was at a loss for words, but not because Holo’s face was a mask of rage. Rather, it was quite the opposite.

“Mm? Whatever is the matter?” she asked. Her words had no particular force to them, nor was there fire in her eyes.

If her color had been poor, he would have suspected her of being ill.

“N-nothing…”

“I see. Well, hurry up and get on, then. Your seat’s the farther one, is it not?”

“Er, yes…”

Lawrence did as he was told and climbed onto the wagon, as Holo followed closely behind him. He sat on the far side, and she settled herself down neatly next to him.

If she seemed many times larger when she was angry, then her dejection had the opposite effect. Her desire to eat the honeyed peach preserves was a terrible thing surely.

This was not the sort of case where Lawrence could laugh off her gluttony. Here in the cold, hard air, they had been surviving on nothing but stale bread and sour wine for some time. There were countless stories of a bowl of soup presented to a lost king and his troop, only to have that rewarded with a great treasure, and now he could see why.

There was no question that Holo had been deeply, sincerely looking forward to the honeyed peach preserves. And now she looked absently ahead, not even speaking a single word of frustration to him.

This had to be because she knew both the great cost of the preserves and the current state of Lawrence’s coin purse.

Lawrence glanced over at her. Her body swayed with the jolts of the wagon. She seemed so absent that she might not have noticed if Lawrence were to suddenly embrace her.

The wagon trundled on.

They would probably be forced to make camp tonight. The only thing that made the hard wagon bed tolerable was knowing that a soft pillow and piles of blankets awaited their arrival in the next town.

“…”

Lawrence tugged on his beard with such force that it almost hurt, then closed his eyes. Perhaps he ought to turn around and slam the entire contents of his coin purse onto the apothecary’s counter.

And yet even as he reconsidered it, Lawrence’s hands did not pull the reins.

A whole lumione for a single peach was simply too much.

In addition to how difficult it would make continuing in their travels if he were to spend his money thus, there was the simple fact that Lawrence believed in the exchange of goods and money for a fair price.

Sweat broke out on his brow as he agonized over the impossible decision. Next to him, Holo, her shoulders slumped, hardly seemed like she could manage yet another night in the cold. The only thing that would return a smile and some good cheer to her would be the moment she could eat the coveted preserves.

He had to buy some.

Lawrence made up his mind and pulled up on the reins.

Holo noticed this and looked up at him, questioning.

One fruit for one lumione.

It was expensive, but what was that compared to Holo?

What’s more, the shopkeeper said he had three fruits left. If Lawrence did not hurry, it was likely he would sell them all. Business was so good in this town that eccentric young trade masters were putting them on loaves of bread and baking them, after all. It was not at all impossible that the apothecary would sell out.

The horse neighed and stopped, and just as Lawrence made to wheel around and head back into the crowd, he realized—

“Business is…good.”

Here in this town where the market was lively, travelers were many, and everyone’s business was booming. The town’s wealth had to be proportionate to that.

If so, Lawrence mused as he stroked his beard, the ideas in his head clicking pleasantly into place.

When the notion was complete, Lawrence took the reins up yet again and headed the wagon back in its original direction.

A man—a traveler, by the look of him—shouted in anger at Lawrence’s driving, but Lawrence merely begged it off with his mask of a merchant’s smile.

At this sudden change, Holo peered at him dubiously.

Lawrence gave a short answer. “Let’s drop by that trading company.”

“…Mm. Huh?” Holo began to make a sound of assent, but it changed into a questioning tone as it left her mouth.

But Lawrence did not reply, simply continuing to drive the wagon in the same direction.

He needed money to buy the honeyed peach preserves, and if he did not have it, he merely needed to earn it.

His destination was a trading company. Specifically, the company the two bakers were discussing: the Ohm Company.

Without money, goods could not be sold, which meant that where goods were selling, money had to be flowing.

The company to which this simple notion had brought Lawrence was the sort you might find anywhere, its modest size perfectly in proportion to the size of the town. Yet it was immediately evident that for some reason, this particular organization was burdened with an excess of money.

The sky was reddening with the setting sun, and though it was the hour when craftsmen would soon be heading home, there was a great clamor of people in front of this shop.

Men ran about this way and that, their eyes darting about with exhaustion and excitement. Some—merchants, probably—held ledgers as they shouted in hoarse voices.

What they seemed to be dealing in was not wheat nor grain nor fish, nor even furs or jewels.

It was wood. And iron.

Those were the raw materials out of which parts of some kind had been constructed, along with the tools for making them.

Literal mountains of such goods were piled on the company’s loading docks.

“.…What is this?” murmured Holo.

They had seen many busy companies, but nothing like the strange energy that pervaded here. While other trading houses would soon be closing for the day, here it seemed as though the main event was just about to start.

“It seems to be materials for building some sort of…something. A crow’s nest? No, this is…”

Lawrence did not know what the strange assemblage of parts was for. But farther in, he saw heaps of specialized goods, and something occurred to him.

No wonder this company was doing such good business. He smiled involuntarily at the thought.

Trading companies made money by buying goods, then selling them, so their biggest opportunities for profit came when they could position themselves as a supplier for a large project of some kind. They would place orders with craftsmen, collect components, and move them along, converting them into their profit margin without letting them lie idle a single night.

Lawrence could certainly understand why this young master fellow would have hit upon the notion of baking bread topped with honeyed peach preserves. He must have felt as though he had discovered a fountain of gold.

He noticed Holo return to her senses and look dubiously around her, as though understanding why this trading company was so busy but unsure why she and Lawrence were here.

“Well, then,” Lawrence murmured to himself. He climbed down from the wagon and strode calmly into the trading company.

It was so busy that nobody took notice of a single outsider like Lawrence walking in. Lawrence, for his part, had essentially memorized how to act natural in such situations.

Once he spied the man who seemed to be in charge, he spoke slowly and distinctly. “Hello, there. I’ve heard you’re shorthanded, so I’ve brought my vehicle.”

The merchant seemed not to have slept properly in days, and his eyes swiveled to glare at Lawrence.

In his hands were a quill pen and a tattered ledger, and his right eye drooped. Lawrence continued to smile as he waited for the man’s answer.

Time seemed to have frozen, but the merchant finally returned to himself and spoke. “Ah, uh, yes. We’ve been waiting. Just take the goods straightaway. Which wagon’s yours?”

His voice was hoarse and difficult to hear, and instead of an answer, Lawrence pointed to the item in question.

“What, that?” said the merchant rather rudely, but Lawrence was not flustered.

“I was thinking it would be best to load it as heavily as possible,” said Lawrence deliberately.

“Mmm, it’ll be slow, though…who recommended you to us? Why, I ought to…ah, well. Fine, load up what you can and leave. Quick about it, now.”

Business paralyzed all sensibilities.

Lawrence was fully aware that in situations like these, those in charge of details like who was doing what job or who was assisting whom could not even try to keep track of them. So, brazenly, he followed up with another question.

“Er, the work came up so suddenly I didn’t catch the details. Who shall I take payment from? And what’s the destination?”

The man was mid-yawn, and made a face like a frog who’d had an insect fly right into his mouth and swallowed it right on the spot.

He had probably been about to hurl some abuse or at least some words of shock, but was too exhausted to turn down help, whatever form it took. He pointed to a man in the far corner who was battling some parchment on a desk. “Ask that fellow over there,” he spat.

Lawrence looked in the direction indicated. He scratched his head, every bit the dullard merchant. “Yes, sir, right away, sir,” he said.

The man seemed to forget about Lawrence that very same instant and set about giving orders to the men working on the loading dock.

Meanwhile, Lawrence ambled over to the man at the desk to receive his work orders.

There is an old story in the northlands that goes like this.

The men of a certain village could see to the far edge of the land, and if a bird took wing beyond the clouds, they could still shoot it down with their bows. Likewise, the women of this village could smile happily no matter how cold the winter grew, and even while they slept, their hands continued to spin yarn.

One day, a mysterious traveler came to this village, and as thanks for the night he stayed there, he taught the villagers how to read and write. Up until that point, they knew nothing of writing and had relied on oral traditions to remember their history and important events. For this reason, whenever anybody died from an accident or illness, the loss was felt very keenly.

They were very thankful to the traveler.

Then, once the traveler had departed on his journey, they realized something.

The men could no longer see to the ends of the sky, and the women began to shirk their work, no longer able to do it without tiring. Only the children, who had not learned to read or write, were unaffected.

It was this story that came to Lawrence’s mind as he regarded the pathetic young man who toiled drowsily away at the desk, constantly fighting off sleep as he frantically wrote.

Once the fetters of letters are around your ankles, they may as well be around your neck, went the the old phrase. Even the devil in hell would’ve had a little more mercy, Lawrence could not help but think.

“Excuse me,” he said. Everything changed when there was money to be made.

The young merchant looked up at Lawrence like a sluggish bear. “…Yes?”

“The boss over there said that I could ask you about where these goods go and my wages as well.” He was not lying. It just was not the entire truth.

The young merchant looked in the direction Lawrence indicated, then back at Lawrence, staring vacantly at him for a moment. The pen in his hand did not stop moving. It was a bit of a performance.

“Ah, er…yes, quite. Well…” Papers and parchments were piled atop the desk one over the other, even as he spoke. Perhaps they corresponded to the amount of goods that were passing through. In any case, they were many. “The destination is…Do you know Le Houaix? There are signs pointing the way, so you should be fine, but…take…those goods there. Any of those, as much as you can carry.”

As the man talked, his attention seemed to drift, his eyelids drooping and his speech slowing.

“And my wages?” Lawrence asked, patting the man’s shoulder, which brought him back to wakefulness with a jerk.

“Wages? Ah, of course…Er…There are labels on the goods, so…just bring those back. Each one should exchange for about…a trenni…or so…,” the man murmured, the words becoming mush in his mouth as he fell forward, asleep.

He would probably be in trouble if he was caught, but Lawrence felt bad for the young man and left him be, starting to walk away.

Lawrence had only taken three steps before he turned around and shook the sleeping man awake. He’d forgotten the other reason he had come here.

“Hey, you there, wake up. Hey!”

“Huh, whuh…?”

“This job came up so suddenly I haven’t a place to stay. Can I rent a room here at this company?” A place of this size ought to have a room or two for resting in, Lawrence reckoned.

The man nodded, though whether it was out of exhaustion or in response to Lawrence’s question was difficult to tell. He indicated farther back in the building. “The maid…is in the rear, so…ask her. You can probably get…some food, too…”

“My thanks.” Lawrence gave the man a pat on the arm and left him.

Though Lawrence had done the man the favor of waking him up, he slumped immediately back into sleep—but it was no concern of Lawrence’s now.

Lawrence approached the side of the wagon where Holo still sat. “I’ve found us a room.”

Beneath her hood, her amber eyes flashed at Lawrence, and in them he could see a mixture of admiration and exasperation at his roughshod tactics. She looked away and then back, this time with a wordless question. Just what are you planning to do?

“I’ve got a job to do.”

“A job? You—” Holo furrowed her brow and soon arrived at the answer, but Lawrence did not engage her further.

He prompted her to get down from the wagon. “They’ll probably be at it all night, so it might be noisy.”

Lawrence pulled on the reins with his left hand, bringing the wagon into the loading area. Given the commotion, he doubted anyone would have helped him in even if he had asked, but now that he was here, the men inside would just do their job. And indeed, the dockhands converged on the wagon, and in no time at all it was fully loaded.

Holo watched the scene, eyes wide, but then her expression began to turn steadily more displeased. She stared at him. Saying nothing, not moving.

“This’ll earn us a bit of money. And a room, but…” He’d already explained what sort of room that would be.

It was clear that at this rate they faced making camp outside the town, and Lawrence wanted to give the exhausted Holo at least one night under a roof.

“We’ll worry about tomorrow when it comes. For tonight, at least, let’s…H-hey!”

Right in the middle of his explanation, Holo stormed off into the trading company.

She had pluck and wit enough to get herself a room, Lawrence knew. “What a bother,” he muttered with a sigh, whereupon he noticed Holo—who was talking to a woman who was probably the maid—look over her shoulder and glance at him.

She moved her mouth as though she wanted to say something, but in the end did not open it. No doubt it had been some invective of some kind.

Fool.

The same word could mean very different things, depending on who said it and the circumstances surrounding the people.

Led by the maid, Holo disappeared farther into the building, alone. He had to laugh at her constant stubbornness, but he knew she was not much different from him in that regard. Lawrence was just as tired as she was, yet here he was, taking on extra work without so much as a break just so he could buy the honeyed peach preserves—the preserves upon which she had surely given up.

Lawrence climbed back atop the driver’s seat and departed, the wagon bed piled high with goods. He felt a certain ticklish amusement, as though he were playing a perverse game.

Or perhaps it was what happened next that made him feel that way. As the wagon pulled away from the loading dock, he looked back and up at the building’s third floor, and just then, a window opened and Holo looked out.

She had already taken out some of the honeyed ginger preserves, and putting a piece in her mouth, she leaned her chin on the windowsill.

“Truly, such a foolish male you are,” her face said.

In spite of himself, Lawrence had the urge to raise a hand in a wave, but he resisted, gripping the reins and facing forward.

He gave the leathers a flick and made for the village of Le Houaix.

The merchant at the company had told Lawrence that he would know Le Houaix when he saw it, and shortly after he left the town, he knew the reason why.

The name Le Houaix was hastily scribbled on a temporary-looking wooden sign. Moreover, the town seemed to expect deliveries to continue through the night, as the path was well lit here and there by torches.

This was probably half to show the way, and half to watch out for unscrupulous drivers who were likely as not to simply take the load somewhere else and sell it off.

The sky had turned red and would soon be a deep, dark blue.

Everyone Lawrence passed seemed uniformly exhausted, and many of the drivers of empty-bedded wagons were asleep in the drivers’ seats.

When he looked back, he could see others like him, all headed for the same destination. Some carried goods on their backs, others in bags on packhorses, and some drove loaded wagons. Their clothes and tack were all different, and all spoke very clearly of having been suddenly and temporarily assembled for the job.

The town seemed to be surrounded by fertile land, which would mean it would need a mill to grind the grain from its bountiful harvests. But waterwheels were not only useful for grain. Lush land would attract more people, and more people would bring more needs. Smithing, dyeing, spinning—all of these could make uses of a waterwheel’s power.

However, constructing and maintaining such a thing was a very expensive proposition, and rivers where they were built tended to be owned by the nobility. Even when a waterwheel was needed, its construction would often become tangled among conflicting interests and schemes.

Given how busy the trading company was, it seemed those interests had all finally been resolved and construction had been decided upon.

The hurry came from the thaw that would come with spring’s arrival, when the melting snow would make construction very difficult. The company’s plan was surely to build the dikes and install the wheel while the river was low. The rising water that would come with the spring thaw would power the wheel quite nicely.

Lawrence did not know whether it was going to succeed, but he could see the desperation in the operation. Of course, that was what allowed him to waltz right in the way he had, so he thanked his luck for that.

Moreover, this was the first time in quite a while he had conducted the wagon without Holo at his side, and while it would have been overstatement to say it was a relief, it was certainly a pleasant change of pace.

Formerly, he would have found driving alone an unavoidably lonely activity, and it made him reflect on how fickle humans were.

As the sun set, he shivered at a far-off wolf howl—this, too, for the first time in quite a while.

He stifled a yawn and kept his attention on the road, the better to keep the wagon’s wheels out of holes and puddles. Soon he came to Le Houaix, where the glow of red torchlight brightened the moonlit night.

To the north of the village was a forest nestled against a steep upward slope, and through it passed the driver. Normally nightfall would drown the forest in darkness, but here the riverbank had been cleared and fires built along it so that it looked almost like a river of fire.

Here and there some workers caught what sleep they could, but Lawrence could see other craftsmen toiling away by the river. It was a larger construction project than Lawrence had anticipated; it seemed they were planning to build multiple waterwheels at once.

It seemed likely to yield unusually large profits.

Lawrence delivered the goods and received wooden tags in exchange, then cheerfully climbed back onto the wagon. His horse did not speak human language, but looked back at Lawrence with his sad purple eyes, as though to say, “Please, no more.”

Lawrence nonetheless took up the reins and wheeled the wagon around, and with a smart crack, he urged his horse forward. This was a simple business—how much money he could make would depend on how many times he could repeat the trip.

The busy, hurried work made him reflect on his rarely remembered past. It might mean only trouble for his horse, but Lawrence came to smile thinly and drew a blanket over his shoulders.

How many trips would it take to reach the honeyed peach preserves? He mused over the question as the wagon rolled on under the moonlight.

The way to Le Houaix was chaotic.

In addition to the Ohm Company’s aggressive hiring, the construction period was short enough that it was advertising its need for porters. As a result, throngs had gathered to get the work.

This was why most of the people that crowded the road all day were not merchants, but rather ordinary people trying to make a quick wage—farmers and shepherds, street performers and pilgrims, craftsmen with their aprons still on. It was as though the entire town had turned out for the job. Most of them carried loads on their backs as they set about doing the unfamiliar physical labor.

Moreover, while the road that led to the village of Le Houaix was not a particularly steep or severe one, it was beset by other problems.

The voices of wolves and wild dogs could be heard from the forest alongside the road, either in reaction to the presence of the people on the road or the food that they ate as they went, and at the crossing of a stream over which a shoddy bridge had been built, there was constant fighting over whose turn it was to cross.

The loads brought to the village had to be dealt with, not to mention the arrival of itinerant craftsmen who’d caught wind of the construction. Added to that was the traffic of women and children running to and fro to draw water from the river, to quench the thirst of the men coming to the village. The path from the village center to the river had become a veritable swamp thanks to all the water being spilled.

The village was sprinkled with soldiers, too, with swords at their waists and iron breastplates on their chests. No doubt the watermill’s noble masters had come to make sure the work was proceeding well.

Earlier in the day, people were full of vigor and thoughts of the wages they might earn, so there were fewer problems. But as the sun went lower in the sky, strength waned and knees buckled, and the situation grew tense.

Even when he returned to the Ohm Company, the loaders’ labors had slowed to a crawl from all the noise being made. On top of all that, some of the most dispirited porters were beginning to complain that wild dogs were now venturing onto the road.

Lawrence had made seven trips with his wagon and was beginning to feel quite fatigued. Even if the road was not so steep, the number of people was itself exhausting.

A quick check of his coin purse revealed that the day’s earnings amounted to seven trenni. That was not a bad wage at all—in fact, it was exceptionally good—but at this rate, it would take three or four days before he had enough to buy the honeyed peach preserves. As more people arrived, causing the work to back up, it might take even more time than that. He found himself inescapably irritated—he could earn more if he could just get his wagon loaded more quickly.

But there was a limit to the amount of work a person could do.

Lawrence took a deep breath, and there on his wagon, he did some thinking. Haste made waste. He would take a break and wait for nightfall. The crowds would thin, and he would be able to make more profitable use of his time. Such was the possibility Lawrence decided to bet on.

He pulled out of the line bound for the loading dock, then stabled his horse and wagon alike. The building was completely empty—all the other horses had been hired out. He then made for the room the trading company had spared him.

Whatever Holo had said to the housemaid, she had neither been chased out nor made to share a room with anyone else. Holo was there in the room alone, sitting in a chair by the window, combing out the fur of her tail, illuminated by the red light of the setting sun.

She did not spare the exhausted Lawrence a glance as he removed his dagger and coin purse and placed them on the table. “Well, isn’t she the elegant one,” Lawrence grumbled to himself but admitted that he was the one who’d told her to stay here. He managed to avoid blundering into the particular folly of voicing his irritation but wondered whether it was even worth it.

Such things went through Lawrence’s mind as he collapsed sideways onto the bed. Then—

“There are two left, he said.”

Lawrence glanced at Holo, not immediately understanding. She did not return his look.

“One sold, and another will probably sell soon, he said.”

It took Lawrence a moment to realize that she was talking about the honeyed peach preserves.

While he had been tired, he had not expected her to thank him for his hard day’s work, but he’d at least hoped for some enjoyably idle chatter. But no, after a day and night of pulling on the reins, he was being immediately pressed on the topic at hand.

Lawrence was unsurprisingly irritated, but as he replied, he tried to keep that from affecting his tone. “You went back there just to check on them?”

His annoyance made it through via the word just, but he was too tired to worry about such things. As he sat on the bed, he untied his bootlaces in order to remove his shoes.

“Will it be all right, I wonder?” Holo pushed him, and his hands froze for a moment. Soon thereafter they started moving again, and he finished removing his boots.

“At one lumione, they’re not asking a price that most people can easily pay, and people who can easily pay that much aren’t exactly common.”

“Is that so. They’re safe, then, no?”

It was an honest enough answer that it could have been taken at face value, but her deliberate tone grated on his already-tired nerves. He was considering explaining very carefully just how much money a single lumione amounted to when he stopped and thought better of it.

Holo had no particular reason to be deliberately irritating him, so it was probably exhaustion that was making him feel this way.

Lawrence calmed himself and loosened his clothing here and there in preparation for a nap.

Holo had looked over at him at some point, and he noticed her gaze just as he was readying himself to lie down and fully relax.

“After all, you must have earned quite a lot.” Lawrence was honestly surprised at her open hostility. “So tomorrow, then? Or are you back because you’ve earned enough already? You’ve made seven loads so far. That’s got to amount to a goodly sum.”

Biting, nibbling ants were an irritation, but the plunging stinger of the wasp was something to fear. Lawrence reacted to the teeth-baring, growling Holo mostly out of reflex, as he wondered where the nibbling Holo of a moment ago had gone. “Er, no, that only comes to seven silver pieces, so…”

“Seven? Oh ho. After all that haste, how long is it going to take you to earn a full lumione, then?”

He had seen her tail fluffed up in the reddish light when he had returned to the room, but now he realized it had been puffed out for a different reason.

But as he cast about, Lawrence’s mind was a blank sheet. He had no idea what Holo was angry about.

Was it because the honeyed peach preserves were about to sell out? Or because she simply wanted to eat them as soon as possible?

His confusion had nothing to do with his exhaustion or anything so trivial. He purely and simply did not understand Holo’s anger and was at an utter loss for words.

Holo’s eyes blazed as red as a hare’s in the setting sun. Her rage-filled gaze bore down on him, making Lawrence feel like his very life hung in the balance of his answer. The moment after that last absurd notion occurred to him, Lawrence realized something strange: What had Holo said just now? She had pointed out that he had made seven trips, but how did she come to have such detailed knowledge?

Not even the company merchants themselves would know exactly how many times they had loaded his wagon bed. It was as though she had been watching him from the window throughout the night.

As Lawrence thought of this, an “ah” escaped his lips. Holo’s ears pricked up, and in her lap, her tail puffed out.

But that angry gaze was no longer directed at him, and he heard no bitter words. Instead, Holo’s eyes narrowed, and she averted her eyes, as though wishing the red light of the setting sun would simply wash everything away.

“…Were you…,” Lawrence began, but Holo literally snarled at him, and he cut himself off. “Uh, never mind,” he mumbled.

Holo glared at him after that, but then sighed and closed her eyes. When she opened them again, she did not look at Lawrence, but rather down at her hands.

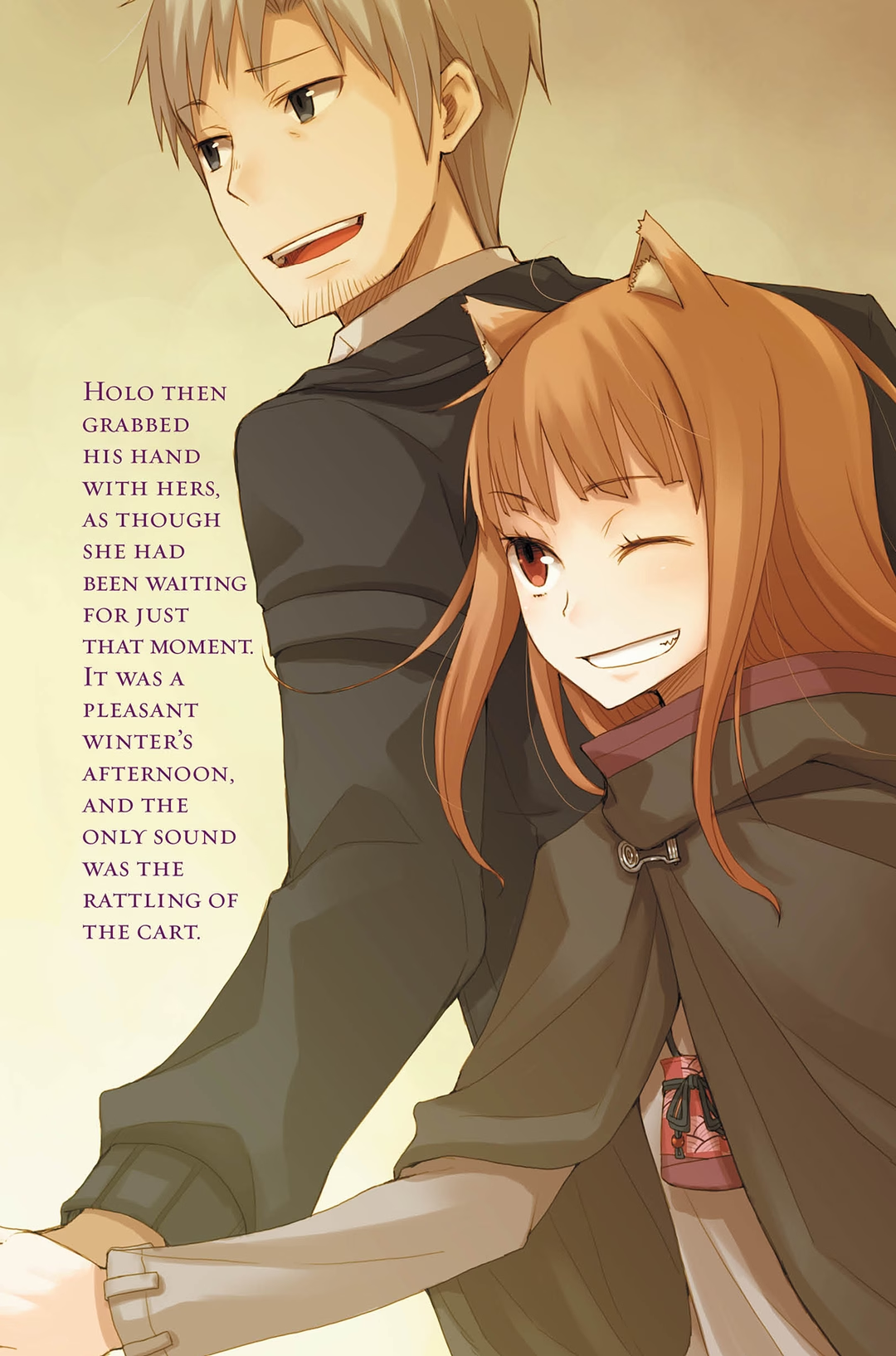

Holo had probably been worried about him, but more than that, she had been lonely, left shut up in the room like this.

She had once said that loneliness was a fatal illness and had in the past put her very life at risk for Lawrence. He had not forgotten her, nor this. He could never forget.

That was why he had worked himself to the point of exhaustion for her, but simply feeling this way would not tell her anything. Just as Holo looking down at him from the window had not.

Even if it was a simple, tedious job, and even if it would only worsen her own exhaustion, Holo wanted Lawrence to bring her along. Anything was better than being left alone, she bravely seemed to think.

Lawrence cleared his throat to buy himself some time.

Since this was Holo, if he was to just up and invite her along, it would be inviting either her exasperation or her anger, and if she felt she was being pitied, it might become an issue of wounded pride.

He had to find some sort of pretext. Lawrence put his mind to work harder than he ever did while plying his trade and finally came up with something that he thought might work.

Lawrence coughed again, then spoke. “There are places on the road to the village where wild dogs have started to appear. It’ll be dangerous come nightfall. So if you wouldn’t mind…” He paused and checked Holo’s reaction.

She was still looking down at her hands, but he detected little of the loneliness from before.

“…I would very much appreciate your help.”

Lawrence emphasized the very much and could not help but notice Holo’s ears twitch at the words.

But she did not immediately answer, probably thanks to her pride as a wisewolf. No doubt she considered it beneath her dignity to wag her tail and happily reply to the words for which she had been hoping.

Holo sighed a long-suffering sigh, gathering her tail up in her arms and giving it a long stroke. Then, when she finally did look up at him, her upturned gaze gave Lawrence the briefest vision of a mightily put-upon princess.

“Must I?” she said.

It seemed she wanted Lawrence to truly insist upon her presence. Either that, or she was simply amusing herself by watching him fold.

This was Lawrence’s own fault for leaving her alone. The fault was his to bear.

“I need this favor of you,” he said still more desperately, and Holo had again turned away, her ears twitching again.

Holo lightly raised her hand to her mouth and coughed, probably to disguise the laugh that threatened to burst out. “Very well, I suppose,” she said with a sigh, then glanced back at her companion.

Craftsmen were acknowledged as such because they finished the job down to the last knot. Lawrence pushed his exasperation and amusement down and responded with a wide smile. “Thank you!”

At this finally, Holo let slip a guffaw.

“Aye,” she said ticklishly, nodding her head. It was proof she was truly pleased.

In any case, he had managed the tightrope walk across Holo’s foul temper. He heaved a sigh and removed his coat and belt. Ordinarily, he would have folded his coat over the back of the chair, but he lacked the energy to even do that much. What he wanted to do most of all was to become horizontal and go to sleep.

And in just a moment that pleasure would be his.

Lawrence’s mind was halfway to the land of sleep when Holo stood and spoke. “Just what are you doing?”

He was unsure whether the sudden darkness in his vision was because he had closed his eyes or not. “Uhn?”

“Come, now that I’m coming along there’s no need for rest. We haven’t any time for dawdling.”

Lawrence rubbed his eyes and willed them open, then looked up at Holo. She was busily putting on her hooded coat.

Surely this was a joke.

He was not angry so much as aghast while he watched Holo prepare. Her innocent smile struck him as cruel, her happily swishing tail as terrifying. She finished dressing, then approached him with that same smile.

She has to be joking. She has to be, Lawrence prayed to himself, but Holo continued to approach.

“Come, let us go,” she said, taking the prone Lawrence’s hand and trying to pull him to his feet.

But even Lawrence had his limits. Almost unconsciously, he brushed her off. “Please, have some mercy, I’m not a cart horse—”

The moment he said it, he knew he had blundered, and he looked up at Holo to see her reaction.

But having been brushed off, Holo was simply looking back down at him with a mischievous smile on her face.

“Aye. That’s true.”

Lawrence wondered if she was angry, but then Holo sat herself down next to him on the bed. “Heh. Did you suppose I was angry?” Her delighted expression made it clear her goal all along had been to rile him.

In other words, he had been made sport of.

“You imagine that resting now will let you earn more efficiently at night, when traffic is lighter?” It was easy enough to discern as much, watching the comings and goings out the window for as long as Holo had.

Lawrence nodded, his eyes pleading with her to let him sleep.

“And that is why you are a fool, then.” She grabbed hold of his beard and tugged his head to and fro. He was so sleepy and exhausted that it actually felt nice.

“You carried loads all night, napped in the driver’s seat, left without even having breakfast with me, worked until just now, and made—what, seven pieces?”

“…That’s right.”

“I remember well enough that there are thirty-five trenni to a lumione, which leaves how much time until you’ve made enough to buy the honeyed peach preserves?”

It was a sum even a child could do. Lawrence answered, “Four days.”

“Mm. Too much time. And moreover”—she ignored his attempt to interrupt—“the loading dock is a madhouse. Do you suppose you’re the only one who’s had the notion to give up, rest, and return in the evening?”

Holo made a proud expression, and beneath her hood, her ears twitched. No doubt from here her ears could hear all the conversations around the loading dock.

“Is everybody else thinking the same thing…?”

“Aye. It’ll be just as bad come night. The dockhands themselves need rest, too. And if you’re already so profoundly exhausted, consider five days of this? No doubt you’ll need more rest, and it will be more like seven or eight.”

Lawrence had the feeling her estimate was more or less accurate. He nodded vaguely, and she lightly poked his head.

In his state, he could not even summon the energy to oppose this attack. As he lay faceup on the bed, he moved only his eyes over to regard the girl.

“What should we do?”

“First, pray the honeyed peach preserves don’t sell.”

Lawrence closed his eyes. “And next?” he asked, already half-asleep.

“Think of a different business.”

“…A different…?” When so much money could be earned simply hauling cargo, it was foolish to contemplate anything else, Lawrence thought in the darkness. But in the instant before his consciousness faded entirely, Holo’s voice reached his ears.

“I’ve heard the chatter here. If you were going to use me to scatter the wild dogs anyway, there’s a much better way to make money. You see…”

As he slept, Lawrence calculated the potential profits.

At the stables, Lawrence rented a two-wheeled cart.

It had a smaller bed and a more cramped driver’s seat, but it was lighter and thus could be pulled more quickly than his wagon.

Next, he collected rope, blankets, baskets, a bit of board, and a good amount of small coins.

Having done all this, Lawrence pulled the cart around to a certain building, whereupon the shopkeeper came running out as though he’d been waiting.

“Ah, I’ve been waiting! You got them?”

“Aye, and you?”

“Everything’s ready. Honestly, I thought you were nothing more than other travelers when you came knocking on my door so early this morning—never thought you’d ask for such work.” The man who laughed heartily was an innkeeper, though his apron was messy with oil and bread crumbs. “I hear you went to the bakers with your request last night. Reckon any craftsman that ends up rising earlier than a priest’ll be none too happy about it!”

He guffawed as he spoke, then turned around to face his inn and beckoned someone out. Two apprentices emerged, unsteady with the weight of a large pot.

“That’ll be enough for fifty people all together. When I sent the lads to the butchers’, he wanted to know just how many people were staying at my place!”

“I truly appreciate it on such short notice. My thanks,” said Lawrence.

“It’s nothing. The guild dictates how much money we can make with its rules—if this helps me make a little more, it’s a cheap favor indeed.”

The two apprentices set the cauldron in the small cart bed and tied it down with the rope. In the cauldron was roast mutton with plenty of garlic, and Lawrence could still hear the fat bubbling.

The next item brought over was the large basket, which contained a heap of notched loaves of bread. Next came two full casks of middling wine.

With all this, the two-wheeled cart was fully loaded. With the help of the innkeeper, Lawrence secured the load with rope. The cart horse looked back at them, which probably was not a coincidence.

I have to haul all this? is no doubt what it would have said, if it could speak.

“Still, to take the money, even with this much preparation…well,” said the innkeeper deliberately, once he had finished counting up the remainder of the payment for the food. He gave his apprentices a few of the more worn coins—perhaps he always did as much when he had an unexpected little windfall like this. They returned to the inn delighted.

“Will you really be all right?” he asked. “The road to Le Houaix cuts right alongside the forest.”

“When you say the forest, you’re talking about the wolves and wild dogs, I suppose?”

“That’s right. The Ohm Company built that road in a hurry to take materials to Le Houaix. All the dogs there came from the city, so they’ve no fear of humans. To be honest, it seems dangerous to carry something that smells so delicious right through that. I’ll bet there were others who thought to do the same thing but gave up, owing to the danger and all.”

Lawrence thought back to the conversation that Holo had overheard from her room. If something could be done about the wolves, then there was money to be made selling food and water in Le Houaix, where there was more demand than supply.

“Ha-ha. It’ll be all right,” said Lawrence with a smile, looking at the two-wheeled cart.

There was someone covering its cargo with wooden boards. Someone slight, delicate, with a casually tied skirt from which seemed to peek a furred sash or lining of some kind. Once she was finished securing the boards, that girl sat atop them with a satisfied smile on her face.

When the innkeeper noticed what Lawrence was looking at, Lawrence smiled. “They put a goddess of good fortune on the prow of a ship to guard against sea devils and disasters. She’s mine.”

“Oh ho…but still, against those dogs?” said the innkeeper doubtfully, but Lawrence only gave him a confident nod and said no more.

Running an inn, the innkeeper had surely seen people from many different regions employ many different good-luck charms. Lawrence would probably be fine admitting to it, so long as he avoided making any offerings to frogs or snakes.

And since he had already given the innkeeper himself a nice offering in the form of some lucrative side business, the man had no reason to complain.

“May God’s blessing go with you,” said the innkeeper as he took a couple of steps back from the cart.

“My thanks, truly. Oh, and—”

“Yes?”

Lawrence jumped up onto the driver’s seat of the cart before he spoke. Two-wheeled carts were not especially rare, but that changed when there was a fetching lass in the cart bed. Passersby stared curiously, and children running in the streets waved innocently to Holo as though she was part of some festival.

“I may come again in the evening for the same order.”

The innkeeper’s lips went round, and he then smiled a toothy smile. “My inn’s full up, so I’ve plenty of help. The guild rules don’t say anything about putting your guests to work!” he said with a laugh.

“We’ll be off, then.”

“And good travels to you!”

With a clop-clop, the cart began to move.

Moving through the town’s morning congestion involved much horse stopping and direction changing, and with only two wheels, it was more effort for the cart’s passenger to stay mounted. Every time the cart swayed, Holo would have to take pains not to fall as she shouted her dismay, but eventually they made it to the outskirts of the town—to the wider world that was a two-wheeled cart’s natural environment.

“Now then, are you prepared for this?”

Lawrence’s question was answered with a nod from Holo, who leaned forward from her sitting position to drape her arms around his neck from behind. “I’m the faster one, you know. A horse’s speed is nothing to mine.”

“Yes, but that’s when you’re on your own feet.”

Normally, it was Lawrence who clung to Holo. Similarly, when in business, it was nerve-racking to conduct a trade with someone else’s money.

Holo snuggled her arms around Lawrence and rested her chin on his shoulder. “Well, I’d best hold on tight, then, hadn’t I? Just as you always do—desperately, trying to keep from crying.”

“Come on, I don’t cry…”

“Heh-heh-heh.” The breath from Holo’s snigger tickled Lawrence’s ear.

He sighed a long-suffering sigh. “I won’t stop even if you do cry.”

“As though I’d—!” Holo’s words after that were cut off by the sound of the reins smacking against the cart horse’s backside as Lawrence gave them a snap.

The horse began to run and the two wheels to turn.

The question of whether Holo had or had not cried would surely be a source of many quarrels to come.

The road could be summarized with the word bracing.

A two-wheeled cart was very limited in the amount of cargo it could carry, and it was far less stable than a wagon with four wheels. But in exchange, its speed was a beautiful thing.

Lawrence did not often use a cart, but it was perfect for the needs of the moment, when he wanted to transport the food while it was still hot. As he sat in the driver’s seat gripping the reins, it felt as though he were controlling the landscape itself as it rushed by.

Holo had clung to Lawrence nervously at first, but very quickly she became used to the accommodations. By the time they neared the forest, Holo was content to hold on to Lawrence’s shoulders with her hands, standing in the cart bed and letting the air rush over her as she laughed.

Given the rumors of wild dogs, the other travelers on the road mostly kept their eyes warily downcast, and a few of them had swords drawn and ready. To see a girl laughing so merrily in a two-wheeler, they must’ve felt ridiculous for being so terrified of anything like a dog.

The faces of the people they passed lit up as they went by, and they would raise their hands and wave. It happened more than a few times that Holo would reach up to return their waves and in the process nearly lose her balance and fall from the wagon. Each time, she would end up having to half strangle Lawrence’s neck to keep her grip, but her snickering made it difficult for Lawrence to feel much alarm.

Given her lively good cheer, it was no wonder the wolf had been so enraged to spend her day locked up in a room.

As they went, a howl sounded from within the forest, and everyone on the road froze and looked to the trees.

Then Holo howled herself, as though she had been waiting for that moment, and everyone turned and looked at her in shock.

They seemed to realize the extent of their own cowardice, and as though to admit the rightness of the girl’s courage in the cart, they all howled with her.

Lawrence and Holo arrived in the village of Le Houaix after a trip that could never have been so enjoyable taken alone.

The throng of people assembled there all gazed in curiosity at this cart, which contained not waterwheel parts but casks, a blanket-wrapped cauldron, and atop all those, a girl. Lawrence stopped their vehicle amid the gazes, then helped Holo to the ground. She seemed so pleased he would’ve been unsurprised to hear the swish-swish of her tail wagging. He left her in charge of setting up while he went off to find and negotiate with the manager of the village. He finished by pressing several silver coins into the man’s hand, and in exchange, he received permission to sell food in the village since the workers were so busy with work they did not even have time to fetch water from the river.

No sooner had Lawrence and Holo begun to sell slices of meat sandwiched between bread than people started to crowd around—not just merchants who had failed to bring food, fearful of what might emerge from the forest to take it, but also ordinary villagers.

“Hey, you there! Don’t crowd! Line up properly!”

They were slicing the already thinly sliced meat in two, then selling it between pieces of bread. That was all, but they were still too busy for any amount of politeness. The cause of this was the wine they had brought, thinking they would be able to sell it at a fine price. Portioning it out took extra time and effort—more than twice as much. Lawrence had done this sort of thing once or twice before but had totally forgotten about that little fact.

They’d managed to sell about half of what they had brought when a man who looked to be a carpenter approached them from behind. “My comrades have been toiling away on empty stomachs,” he said.

Holo was originally a wolf-god of wheat and was thus always sensitive to manners of food. She looked at Lawrence, wordlessly insisting that they assist.

There was yet meat in the cauldron. Traffic continued to stream into the village, so if he stayed where he was, he would sell out before long.

Lawrence was a merchant and was happy as long as his wares sold. There seemed to him little point in moving just to accomplish the same task—but then he changed his mind.

Given the people going back and forth between the village and the trading company, news of the business he and Holo were doing was bound to spread. They would do well to expand their market by selling a bit of food to the craftsmen.

Lawrence sank into silence as he thought it over but was brought back to his senses by Holo stepping slightly on his foot.

“Why, aren’t you making a cunning face?” she said.

“I am a merchant, after all. Right,” said Lawrence. He finished placing a slice of meat between pieces of bread and handing the sandwich to a customer, then put the cauldron’s lid back on top of it and turned to the craftsman. “I’ve enough left for twenty men, say. Will that do?”

The craftsmen working alongside the river were like ravenous wolves.

The Ohm Company, which had taken on the construction project thanks to their boundless lust for money, had hired these craftsmen but failed to provide food or lodging for them, so the men had gotten by on nothing but an evening meal provided by the villagers out of pure kindness.

Moreover, since the work was paid piecemeal and done on a deadline, the workers were reluctant to take the time to go all the way back to the village for a meal. Even once they became aware of Lawrence and Holo’s arrival at the mill, they regarded them with only a brief, sad glare before turning their attention back to their work. The ones working on the wheelhouse’s axles or interior did not even show their faces.

Lawrence carried the wine cask, and Holo pulled one of the small handcarts the local women used to move heavy loads, which in turn was loaded with the cauldron and bread basket. They shared a glance.

Evidently they would be peddling the food on foot.

“What, that all? It won’t be near enough!” So said everyone they sold bread to, but the complaint always came with a smile.

Apart from those who made their living under a workshop’s roof, any carpenter was happy to brag about the terrible conditions under which he’d worked. So while each and every one of them had to be famished, none demanded a greater share of meat or bread.

Far from it—they asked Lawrence to give food to as many men as he could manage. It was impossible to build a great water mill alone, and if even one man fell it would be trouble for all, they said. Holo had spent so much time watching the workers in her wheat fields that she seemed to empathize with this.

But she did not just empathize—she seemed to take great pleasure in bantering with the workers, and Lawrence could hardly fail to notice her ladling out extragenerous servings of wine.

Of course, he said nothing.

“Two pieces of bread here, please!” came a shouted call from one of the millhouses that already housed a millstone.

It was covered in fine powder, but the stuff was not flour—it was sawdust from the wood that they were, even then, in the midst of cutting.

Holo sneezed several times and decided to wait outside the shack. Perhaps her excellent sense of smell made her that much more sensitive.

Lawrence sliced off two pieces of bread, then ascended the steeply rising stairs.

They creaked alarmingly as he went, and there was not much room between his head and the ceiling. The men there were covered in sawdust and were fighting with files and saws to get the axle gearing to properly mesh.

“I’ve brought the bread!”

A watermill could be surprisingly loud, and it was—all the more so in the small shack, with the creaking and groaning of the turning axle.

Yet at Lawrence’s yell, the two men suddenly looked up at him and rushed at him with surprising alacrity.

Holo laughed at him when Lawrence later told her he was afraid he would be knocked back down the stairs.

When Lawrence sighed because he wished she would be a little more worried about him, Holo slowly and gently brushed the sawdust from his face and smiled.

The wheel turned, rising, then falling, then rising again.

Holo was like a waterwheel, like a mallet, and Lawrence was easily undone by her.

“Well, I think we’ve about made the rounds.”

“I’d think so. Dividing the meat and bread in half we managed to get to most everybody.”

Holo pulled the cart that was carrying the wine cask and cauldron, and on her chest was a wooden pendant, carved in the shape of a hare, that one of the carpenters had given her.

“I’d like to head straight back to the village, put in another order, and see if we can’t double our business by noon tomorrow.”

“Mm. Still, how much did we make in the end?”

“Well, now…wait just a moment…” Lawrence counted the various costs on his fingers, and the figure he arrived at was surprisingly low. “Around four trenni at best, after we change the money.”

“Only four? But we sold so much!”

It was true that Lawrence’s coin purse was heavy with coppers, but poor-quality coppers were never going to amount to much, no matter how many you had.

“I’d feel better pushing prices higher if we were selling to greedy merchants, but the craftsmen aren’t making that much. So that’s how it is.”

Given that Holo was the one who had suggested selling food to the craftsmen, she could not very well argue with this and pulled her chin in with irritation.

Of course, doing business that people were so grateful to receive came with benefits other than money. Even when profit margins were slim and the dangers great, Lawrence could rarely resist the trade routes to lonely villages since he could never forget how it felt to bring the villagers what they needed.

Lawrence put his hand on Holo’s head and patted it a bit roughly. “Still, we’ll bring double the food tomorrow and turn double the profit. If we make arrangements ahead, we’ll be able to sell at night, too, which will double our profit again. We’ll have those honeyed peach preserves before you know it.”

Holo nodded at Lawrence’s words, and her stomach growled almost in time with her nod.

Her ears twitched ticklishly under his hand, and Lawrence pulled away. He could not very well pretend not to have heard the growl, so he just gave an honest chuckle.

Holo made ready to play-punch Lawrence’s arm, but just before she did, Lawrence’s stomach itself growled with fortuitous timing.

Their constant struggle to keep up with sales of meat and bread had kept their hunger at bay, but now it seemed to have returned with a vengeance. Lawrence met Holo’s eyes. He smiled at her again, and Holo’s angry expression immediately softened.

Lawrence glanced about their surroundings, then reached for the cart.

“What is it?” Holo asked.

“Oh, nothing,” said Lawrence. He removed the cauldron’s lid, pulled out the last slice of meat sticking to the inside, along with a nearly crumbled piece of bread. “I saved this. Thought we could eat it on the way back.”

Normally Lawrence sold everything that could be sold, and when he was hungry ate anything he could find that seemed edible. He’d never before considered saving a piece of salable product and eating it later.

Lawrence cut the meat with a greasy knife as Holo’s tail wagged.

“Still, you.”

“What?”

“You seem to have missed the crucial point again.”

The cheap mutton was full of gristle, so cutting it took some time, but Lawrence finally looked back up at Holo. “The crucial point?”

“Mm. If you were planning all along to reveal this plan, you should’ve used nicer meat. This meat is merely adequate.”

Apparently it had been too much to trust Holo to suffer through skipping lunch. Of course, it was very like her to have been watching for openings to secretly sneak bites of meat throughout the day.