CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

No one knows what will happen on a journey.

It’s well within the realm of possibility to part ways with a companion and promise to meet again in the next city, only for that friend to fall ill a few days later and pass away. One may purchase plenty of goods, convinced that it will bring guaranteed profits right up until it becomes clear that demand already crashed, inviting bankruptcy instead of business. And perhaps a simple visit to a town for supplies leads to picking up a girl who desperately wishes to return to the north.

And so, who could blame a girl who set out on a journey of her own when she stopped sending letters home, despite how much worry it would cause her parents? As it turned out, that was reason enough to encourage the girl’s mother and father to descend from their hot spring village nestled deep in the mountains and see the world again.

In the course of retracing Myuri’s and Col’s footsteps, Lawrence and Holo found themselves inextricably drawn into world events. They met a squirrel spirit, reunited with old traveling friends, and even came close to becoming rulers of their own domain.

Though the matter of lordship had occupied Lawrence’s mind for a time, he ultimately chose easygoing travels with the self-proclaimed Wisewolf, along with her penchant for jerky and booze. Then they departed from the city of Salonia by boat and headed toward the open sea.

They headed downriver, sipping drinks and listening to the shanties.

Lawrence believed they would hear more about a certain rambunctious girl and her adoptive older brother in the next seaside city, but—

“Hmm…? What did you say?”

Puffy eyes peeked out from a messy mop of hair to peer at Lawrence.

He had not minded it so much in his sleep, but after waking up, leaving the room, washing his face at the well, preparing breakfast while collecting information from early-morning travelers, and then finally returning to the room, the strong smell of alcohol that still filled the air caused him to scrunch up his face.

“You’ve been drinking too much.”

Lawrence glanced briefly at Holo as she lay whining in bed before he threw open the windows and took a deep breath of fresh air.

“’Tis too bright…”

He might have felt inclined to shield a moss-laden forest spirit from the harsh rays of sunlight, but he felt no pity for the wisewolf who had been entranced by the musical performance of the tavern bards and ended up dancing the night away, drink in hand the entire time.

“Even the most boring parts of a journey are filled with delight when I travel with you”—she had just moved him with such touching words, and now this. Though Elsa was not around to scold him about it, he still felt like he really did spoil Holo a bit too much. Of course, it was a little late for that epiphany.

“Good grief. Well, you look like you regret being alive at the moment, so I’ve got great news for you. No boats are heading downstream right now.”

Lawrence sat in the chair, waiting for the fresh air from outside to replace the strong smell of ale as he bit into a piece of bread he had purchased.

“Mm… That smell…”

Holo, who would normally leap from bed at the first whiff of freshly baked bread, instead scrunched up her face and groaned. Lawrence had seen this sight so many times he was genuinely quite tired of it, but he knew it would be a massive pain to clean up if she vomited, and he also knew he might have to pay the inn an exorbitant amount if it turned out particularly badly. And so, with a sigh, he moved his chair away from Holo to avoid bothering her nose.

“Something’s going on in the port city downriver. I think we’ll be stuck here a while.”

“……”

Lawrence could usually tell when Holo was listening by watching her ears, but they did not so much as twitch.

He swallowed his sigh with a bite of bread and continued, “It looks like our options are either wait here for things to blow over or get a horse and cart to travel by land.”

Lawrence paused, wondering if he would get an answer, but he received none. Her typically beautiful tail was all ruffled and messy, reminding him of a stray dog that had been tragically run over by a wagon.

This was all her own fault to begin with.

“If we go by land, then we may as well head straight south to Kerube. It might be easier to find information on Myuri and Col there. It’s the busiest city in the area, so I know they’ll have lots of good food.”

The fur on her tail twitched at the words good food, so now he was sure he had her attention.

But even Lawrence could not tell if that meant she was not interested in talking about food right now or if she was hoping to be fed the moment she felt better.

“Well, we’re not in any rush, so you can rest. Travelers coming from downstream should be arriving in the afternoon, and they should have a better idea of what’s going on.”

Lawrence thought he heard Holo say something, but soon all he could hear were her deep, sleeping breaths. She was probably just mumbling in her sleep.

With a weary smile, he put the half-eaten bread into his mouth and pulled the blanket over his princess.

Rivers, without fail, passed through several private lands, and that meant checkpoints sat in each one.

Most consisted of nothing more than a riverside hut run by one or two overbearing tax collectors, but some were lively places where multiple land-borne trade routes intersected. Those were proper post towns where inns and taverns meant for travelers could be easily found.

The place where Lawrence and Holo were staying was not the most developed, but there were at least three buildings that offered meals and lodging, as well as some local artisans who mended clothes and shoes—more than enough amenities for a traveler to rest in comfort.

As vexing as it was to be taxed at each checkpoint, this was a place meant for travelers. It was nice to sit outside a tavern and have a drink during the day without needing to worry about any judgmental glares.

Lawrence sipped at his cheap wine, which had become somewhat tasty only after he added a gratuitous amount of honey. At the same time, he gathered information as people passed him by.

The moment he realized a shadow had fallen over him, he also noticed a girl had brusquely taken the seat across from him.

“You seem quite comfortable on your own, no?”

The one who had decided to insult Lawrence without so much as glancing at him was a girl who seemed to be in her early teens.

But she seemed in her element by the way she raised her hand to catch the bartender’s attention, and it was clear she knew what she was doing by the way she ordered a sweet yet sour juice that would one day become alcoholic cider. Today, however, its duty was to ease her hangover, and she made sure to order honey to make it even sweeter. Despite how young she looked, she was still the same centuries-old wolf.

“I am pleased. There is plenty of the good honey here.”

“But that doesn’t make it any cheaper.”

“You fool,” Holo said, eyes dropping to the piece of jerky by his hand. Though she frowned, likely not pleased by the prospect of eating tough food right after waking up, she still reached out and pulled the entire plate toward herself, as though deciding that she would make do with what he had.

“Shouldn’t you have porridge or something instead?”

“Then order it for me. Make it hot.”

Her drink that came shortly after was a deep red that likely came from steeped gooseberries. She took a swig and immediately squeezed her eyes shut—perhaps it was sour, even with the honey. After exhaling heavily, Holo bit into a piece of jerky.

Lawrence was glad she seemed healthier and asked for soup with breadcrumbs in it.

“And? What led you to leave me behind and come drinking, hmm?”

“You’re not even sick. You wanted me to stay with you and hold your hand?”

Holo kicked Lawrence under the table. He could see it was partly their normal banter, yes, but what stood out to him was how she seemed genuinely frustrated with him.

Perhaps she did not mind so much that he was gone when she woke up, but that the open window had swept away most of his scent.

Even though this wolf seemed laidback at a glance, she had lived for much longer than any normal human lifespan; her waking moments were often plagued by the sneaking suspicion that everything was but an ephemeral dream. And in that moment of self-doubt, she must have rushed to the window only to find Lawrence enjoying a drink by himself. Most likely, that was what had set her off.

“You didn’t hear a word I said this morning, did you?” Lawrence asked flatly.

“What are you talking about?” Holo narrowed her eyes at him.

“Obviously, it’s the very reason we’re lounging around at the inn, even though it’s way past noon.”

She opened her mouth to say something, but she knew anything she said would have the opposite effect.

She pouted and sipped on her honeyed juice.

“There’s some kind of big city council meeting at the port down the river.”

Lawrence reached to pluck a piece of what remained of his jerky, watching new ships arrive from upstream. Yet none were leaving the docks, which meant they were crowded with boats. There was a lot more traffic headed downstream than he expected.

“It sounds like they’re discussing taxes, so everyone’s keeping a close eye on it.”

Holo, who still looked very hungover, lightly furrowed her brow and said, “Then should it not be the opposite?”

She followed his gaze toward the docks just as a new ship bursting with cargo arrived. The idle apprehension that it would not be able to fit anywhere was for naught—the skilled pilots easily guided it into the tiniest of spots.

“Are taxes not the worst nightmare of you merchants? Why not rush downriver before they are levied against you?”

“If I did, you’d be feeding the river fish your dinner from last night right about now.”

Ships that crossed the sea rolled, but so did those that traversed the river. Lawrence could not help but smile when he pictured a languid Holo—she was always adorable—but when he noticed the wolf looking at him dubiously, he cleared his throat.

“To everyone’s surprise, they’re talking about lowering the tariffs to enter the city.”

The reason Holo did not quip at Lawrence right away was because the soup came at the exact same time.

She scooped up the soggy bits of bread with her wooden spoon and began to devour it.

“And that’s why everyone—travelers and even merchants—are all staying put until the local council announces their verdict.”

Thick pieces of carp swam in the soup along with the bread. Holo kept her mouth open as she breathed to cool herself down, taking a swig of her juice to help. Then she licked her lips and raised her head.

“Then it has nothing to do with us, no? We have no cargo. I do not mind this place, but I would prefer to idle my time away in a larger city.”

“Yeah…but it could also be bait.”

“Bait?”

“A rumor to lure people in, and then… Chomp.”

Walls that surround a city do not only protect those inside from outside enemies. They also prevent those inside from escaping. Cities that wanted to fill their war chests, for example, often forced visiting merchants to pay exorbitant travel fees if they wished to leave the city. Many would reluctantly pay the high tax, knowing it was preferable to getting caught up in a war. It was entirely possible that the local officials wanted to lure merchants into the city for precisely that reason.

What sat in Holo’s spoon were fish that just so happened to get caught in traps lying at the bottom of the river—and just so happened to become ingredients for soup.

Holo’s gaze drifted to the sky in thought as she brought the morsel to her mouth.

“Mm. Sounds plausible.”

“So, how about we stay out of danger and head south by land instead?”

Holo frowned at the suggestion. That was the face of someone who was actively recalling the pain in her tail that came from sitting on a rickety cart and comparing it to the comforts of boat travel.

“If we manage to reach the Roef River, we could then catch another boat to Kerube.”

“Kerube… The name is familiar.”

“That’s where they caught the narwhal, remember? The sea creature whose horn is supposed to grant eternal life if you grind it into a powder and drink it.”

Holo lifted her chin and gave a cheerless nod.

A being that lived longer than any human likely had complicated feelings about things that supposedly offered eternal life. Or perhaps she recalled the conflict involving the absolute greediest merchants they had met in their travels together.

“The good old Rowen Trade Guild is in Kerube. We could say hello to all those who helped us while we were getting the bathhouse set up. It should also be easier to get information on Myuri and Col there.”

Their only daughter Myuri and the boy who both worked in the bathhouse and doted on Myuri like an older brother were making quite a name for themselves. Lawrence and Holo had flippantly assumed the kids would be easy to find because of that, but it turned out to be a surprisingly impossible task because they had become too famous. There were many rumors about them, ranging from miracles performed on a mountaintop to plagues cured in some distant town.

However, Lawrence expected companies with trading houses spread across multiple cities to have more accurate information.

“Hmm. That is the river on which we found little Col, and the city beyond that, no? ’Tis quite a long way away.”

“Yeah, the route isn’t a straight shot from here to there, so it’d probably be three—no, we’re not going there for trade, so we can take it slow—meaning it’d be more like five, maybe six days by cart… I don’t really know this area very well.”

Holo’s complaints might have been aggravating if Lawrence himself had not become rather accustomed to the bathhouse life. His back would immediately start hurting on the hard driver’s perch of a cart. They would have to look up the roads, make stops, take rests, and everything else. It would probably take even longer.

Either way, they were starting to see signs that the plans for their tranquil little journey were about to fall apart, and Holo slurped her soup loudly in protest.

“I shan’t say no if you choose to ride on my back.”

Holo, in her wolf form, could probably get there in one night.

“What about the horse?”

“…Horsemeat is sweet but goes surprisingly well with strong liquor.”

Lawrence, unsure how genuine her joke was, simply sighed and sipped his wine.

“Personally, I want to wait and see what happens for just a little longer.”

“Mm?”

“I don’t know what the city down there’s thinking, but if they really do lower taxes, then it’d be better if we get all our nonessentials over there, right? We’ve had a lot of customers at the bathhouse recently who aren’t nobility who have also been complaining when they have to forgo luxuries from the south.”

Holo regarded him coolly, like he was a fool sharing his dreams of becoming rich.

“You are a male who never learns his lesson. We leave matters to the rabbit and his company. Do you not remember when you ordered wheat from a new place and ended up swindled with cheap product?”

The Debau Company, where a certain rabbit spirit acted as head clerk, was a reliable liaison for the Spice and Wolf bathhouse when they needed to order more supplies.

As for the wheat incident, it was Holo and Myuri who had sniffed out that cheap rye grain had been mixed in with the expensive wheat, which allowed them to escape the worst.

“Oops. But if I never learn, then should I tell you why you had such a hard time waking up this morning?”

Holo pursed her lips into a thin line, but she did not kick him.

The moment Lawrence was convinced she had finally started regretting the excessive drinking because of her terrible hangover, he sensed someone approach their table. He looked up.

Standing there was a man wearing the clothes of a farmer, a thin hat clutched in his hands, offering both of them a hesitant smile.

“You must be Sir Kraft Lawrence and his honorable wife, yes?”

It was hard to say the man was dressed finely, and his overly polite language was rather odd, but it was immediately clear that he knew who they were, because what he offered along with his greeting was a small cask of alcohol that could fit under one’s arm.

Even though Holo had at last gotten over her hangover, her eyes glimmered as she reached out to take the cask with great delight.

“Heh-heh… Mmm, this is good quality mead! Aye, if you’ve a need to speak with us, go on, then.”

Obviously, when she said us, she really meant Lawrence.

Lawrence sighed and turned his attention to the farmer.

He was farmer-like in the sense that he dressed like one, but his demeanor was unusually refined, and he seemed quite comfortable offering mead in greeting.

Lawrence thought back on all the people he had met in trade, yet he did not find the face familiar.

“Pardon me, but have we met before?”

“No, this is our first meeting. But I heard of your undertakings in Salonia.”

Lawrence nodded.

He had gotten a little too excited in Salonia and had become a bit of a celebrity there.

It was nice that they were able to eat and drink all they liked and had a grand time overall, but the attention they garnered had caused unexpected waves.

“I know you are in the middle of your travels, but please, I hope you will listen to what I have to say.”

His polite language and the way he sank to one knee to make his plea told Lawrence that despite his appearance, this man often interacted with those of higher status.

But he was much too young to be a mayor, and somehow they could tell that he was no normal villager. Lawrence rifled through all the knowledge he had gained in his past travels as a merchant as he carefully studied the man’s belongings. He noted a simple hatchet and a small bow. And the way he adroitly prepared a flask of fine mead for Holo told Lawrence everything he needed to know.

“What could a forest ranger possibly need from us?”

The man’s eyes widened in surprise and a bright smile burst across his face moments later.

“So this is the great mind of Sir Lawrence, Salonia’s problem solver! Please, we need your help!”

As much as Lawrence wanted to tell him that this journey was meant for him and his wife alone, Holo was already happily nursing her mead. It sure must be nice knowing she’s not the one who’ll be taking care of this problem, Lawrence thought. Then another possibility occurred to him.

It was very likely that she had smelled the earth and the trees on this man and immediately known he was someone who worked in the forest. Just like how Lawrence was enticed by many get-rich-quick schemes, Holo loved the forest beyond all else, so she had likely engineered this so Lawrence would offer an ear to a troubled forest dweller. And if she received mead as a bonus, then all the better.

This meant that if he were to turn this man away, Lawrence knew he would be once again exiled from the bed and forced to sleep alone on the floor.

“I would be glad to,” Lawrence replied, already feeling tired.

The man was delighted and Holo gave a satisfied nod.

The man called himself Meyer Linde, the latest in a long line of forest rangers hired by the lords of the Tonneburg territory, which was situated south of this checkpoint. Holo was strangely impressed by the name of the man’s occupation. She probably assumed it denoted a person whose job was to watch over the forest and doubted anyone who did so professionally could be a bad person.

But forest rangers did not simply watch over the forest. They did just that, yes, but their focus was the natural resources in a specific part of the forest, not the whole. The woods around Nyohhira were too deep for rangers’ services to be useful, but the farther south one went, the more valuable they became. And thus, the roles they played became more and more important. Precious, even, for places like this one, where much of the land had been cleared for wheat production.

Ranger Meyer was responsible for the Tonneburg Woods, which was rather hilly compared to the surrounding area, which meant it was home to dense, untouched forest.

Meyer’s current concerns were a plan to cut down the old growth trees, ship off the lumber, and build another road through it.

“And so you’d like to stop this plan, correct?”

“Yes. But there has been trouble so I’d like your help, Sir Lawrence, if you would be willing.”

The words forest dweller tended to conjure up images of pessimistic, anti-social individuals with overgrown beards that resembled untamed moss and eyes that were always open wide like spooked deer. The reality was that rangers were civil servants who worked in the forest.

They were often in the employ of nobles and spent their days arbitrating conflicts of interest concerning the land, which meant their manner of speech was refined. If someone told him that Meyer was the head clerk of a merchant company, he would not have doubted it for a second.

And so of course he would be skilled in finding openings and taking advantage of them.

“I originally visited Salonia to keep an eye on a series of negotiations,” Meyer paused, giving Lawrence a meaningful glance. “I admire your work, Sir Lawrence. But the negotiations on the lumber tariff decrease that you stopped have caused unexpected waves.”

Unexpected waves. Lawrence had a terrible feeling about that ominous turn of phrase.

“I did offer to do everything I could on behalf of the Salonia Church, but… Do you mean to say that I have inadvertently caused problems for you, Lord Tonneburg, or the people of your region?”

“No, no, I would not call it a problem, per se.”

Though Meyer’s manners and humble bearing were impeccable, his words did not seem very sincere. He was like a lamprey, moving effortlessly even as he steadily approached his objective.

Holo seemed oddly pleased by both Meyer’s general demeanor and the way Lawrence seemed to be feeling awkwardly pressured in this conversation. Lawrence was slightly bitter about that.

“It is clear that you chose the correct path on behalf of the church, in accordance with God’s teachings. But as a result, lumber tariffs remained much the same. Consequently, the port town of Karlan, which sits at the mouth of this river, cannot procure cheap lumber due to your actions.”

“Ah.”

Lawrence knew immediately where Meyer’s story was headed, and he made a quiet noise in his throat. Holo’s wolf ears twitched beneath her hood and she fixed Lawrence with a cold stare.

“If tariffs on lumber that passes through Salonia were lower, then Karlan would be able to obtain cheap lumber. That plan has crumbled, however, and so they have been pressuring Lord Tonneburg to cut a path through our forests, which is something they were planning to do previously.”

The price of lumber had skyrocketed recently; even in Nyohhira, a place completely surrounded by dense forests, the amount of firewood any individual could collect was restricted by council decree. The rules were even stricter in places where there were overwhelmingly more plains and grasslands than forest.

The discussion on lumber tariffs in Salonia did not come from the lumber merchants’ desire to make a quick coin, but because every regional merchant had been watching over the entire affair with bated breath.

In essence, the kneeling ranger was saying that because of Lawrence’s actions in Salonia, now his precious Tonneburg Woods were being targeted—and the implicit question was how Lawrence would make up for it.

In addition to Meyer’s damning assessment, Lawrence could feel Holo’s reproachful stare. She would always side with the forest.

If Lawrence had simply not stuck his nose where it did not belong, then lumber tariffs would have gone down, the port town of Karlan would have been able to obtain lumber for cheap, and Meyer’s Tonneburg Woods would have been left alone.

“I—I believe I understand your predicament. So, what exactly are you having trouble with?” Lawrence asked, like a criminal desperately trying to stay his execution for even a moment longer.

Tonneburg and its lord were likely not negotiating from a position of strength when they held talks with Karlan. Perhaps the city employed mercenaries to strong-arm its neighbors, like in the days of yore.

Or, more likely, it would be the sort of issue Lawrence could help navigate and resolve somehow.

“Lord Tonneburg agrees with cutting the forest down.”

Holo frowned. For her, it was unthinkable that the lord of the land would agree to have it developed like that when he was supposed to safeguard it. Lawrence, on the other hand, dipped his head because he could already see where this was going.

“Your lord agreed to—”

“Yes.”

Meyer returned Lawrence’s stare and gave a firm nod. Though mere moments earlier the man was like a slippery fox, his eyes were now that of an eagle that had spotted its prey.

“A humble peddler like—ahem,” Lawrence cleared his throat, pausing in his habit of saying humble peddler like myself. “I am no noble. I doubt I have the power to meddle in the political affairs of a city and a local landowner—ouch!”

Meyer stared wide-eyed at Lawrence, who returned the look with a vague smile in an attempt to brush over his stumble.

Holo had kicked his ankle under the table.

“Your fears are reasonable, of course,” Meyer continued, pivoting ahead to make sure his prey would not slip away. “But you are perfectly suited to resolve this situation precisely because you excel in trade, sir.”

“……”

Lawrence gave a little sigh, and not because Holo had kicked him. He gestured for Meyer to keep going.

“First, I believe Lord Tonneburg has made a simple error in his calculations. A forest, once cut down, does not easily grow back. And yet, he not only wants to clear trees but is also giving into temptation and plans to build coal-burning huts and smithies as Karlan has requested.”

Lawrence held his breath not in response to what Meyer said, but because he could hear Holo’s tail beginning to rustle beneath her clothes despite her blank expression.

“And that’s not all. Lord Tonneburg is looking to build a road through the forest so that all of the refined metal and coal can be easily transported, further developing trade. Representatives of Karlan sit on his shoulder and whisper to him that with a road, his wallet will grow fat off tolls, and he believes it.”

It was true that Lawrence found Meyer’s words a bit overwhelming, but the reason he shifted in his chair was because it no longer seemed like this was simply about making up for the cheap lumber that was supposed to be sourced from Salonia.

“The woods will grow thin, and the people who depend on the trees will be reduced to poverty. Yet all Lord Tonneburg can think about is the lumber trade, the coal-burning industry, the profitable smithies, and the lucrative tolls from those new roads. He has decided to line his pockets even if it means his people becoming impoverished and the woods dying.”

It did not seem as though Meyer reached out to Lawrence only because he was involved in the events that unfolded in Salonia. He had shrewdly determined that the only way to persuade his liege was to show him that he shouldn’t count his chickens before they hatched—making Lawrence the perfect man for the job.

“I have learned that you are now the owner of a bathhouse in a very well-known hot spring village, but you were once a renowned merchant who traveled the world over. I would be forever thankful if you could put that trading knowledge to use and tell Lord Tonneburg that his appraisal is not completely accurate.”

The overstated praise was not simple flattery—the fact that the bathhouse had been mentioned at all was proof of that.

Meyer was shrewd. He had done his research on the events in Salonia and had likely met Elsa in the process. It was a subtle threat; this was his way of telling Lawrence that he knew exactly who he was.

“What do you think? If you help me protect the woods, then I promise you seasonal ciders made with the fruits of the forest, in addition to mead, dried mushrooms, venison, and rabbit jerky. I vow on Tonneburg Woods’s honor that they are excellent products and more than enough to satisfy all the nobility who visit Nyohhira seeking relaxation and comfort.”

Holo’s eyes were glimmering at the delicious proposition, but it sounded completely different to Lawrence’s ear. A discreet offer of goods in lieu of coin most likely meant that paying for his services was either difficult or outright impossible.

That was because a vassal seeking to overturn his lord’s decisions would be risking life and limb.

The correct answer, if given careful thought, would be for Lawrence to immediately accept Meyer’s proposal with a smile, pack his bags, and run away with Holo in tow. If the other party insisted on following through on the veiled threat of harassing the bathhouse, then it would be a simple matter to retaliate with their nonhuman allies.

But there was good reason why Lawrence had no room to maneuver. The growling of the empty stomach from the glutton beside him aside, it was still true that those who lived in the forest would lose all its blessings if it was exploited with wild abandon.

More importantly, there was a much weightier issue than his role in the events at Salonia, which were the reason this was happening in the first place. And the heart of that issue sat behind him.

All he had to do was picture Holo when, one day, after this moment became a distant memory, she set off on a fresh journey in pursuit of fond memories. There might be a day when she would visit the Tonneburg Woods on a rumor.

He pictured her standing there alone, looking out over a wasteland dotted by the occasional tree, a place that humans had shattered long ago.

To Lawrence, nothing could possibly be sadder.

“Hmm?”

When Lawrence glanced aside, he found Holo looking at him dubiously.

He stood at a crossroads, in a way.

Would Holo fall to her knees at the threshold of a wizened forest, fingers brushing parched earth? Or would she laugh when she found a message left to her from Lawrence, carved into a sapling?

That was how he urged himself to his decision.

Rationally speaking, asking a ruler to change their mind was something wise people avoided. Yet Meyer was requesting that he show his lord how misguided his thinking was. In essence, this was a matter that did involve trade, but the problem was an entire magnitude more complicated.

Reasons he should turn this request down loomed over Lawrence like a mountain.

Yet opposite him sat Holo, and she looked at him with wide eyes.

There was risk both in getting involved and in not getting involved.

He balanced everything on his mental scales, then finally said, “…Would you give us a moment to speak?”

Meyer must have sensed the partial surrender in his tone; he glanced between Lawrence and Holo, keeping his expression as blank as possible, and bowed his head.

“You fool! The forest is at risk because of you!”

Holo, sitting atop the blankets, thwacked her tail over the bed once, twice.

And when it landed against the sheets for a third time, she cradled it in her lap.

“…As much as I wish I could scold you so, I admit I was rather pleased you put in so much effort on my behalf in the previous town,” she said, glancing at her diary and the gifted cask on the table.

Both were perfectly sweet.

“Luckily, this matter involves the forest. I may not get many chances to make a difference in human affairs, but I may be able to play a role yet when it comes to protecting the woods.”

Lawrence was surprised.

“Why the face? We simply discourage them from cutting down the trees, no? Such conflict can be resolved in an instant by simply flashing my fangs.”

Foolish humans who ventured into the deep, pristine wood were at risk of running right into the sharp claws of the forest spirits.

That would lead to a happy ending in a fairy tale, but reality was not so simple.

That was especially true when it came to business.

“I understand. I know you want to protect the forest. But—”

“But what?”

“Do you remember what Meyer said? He wanted me to show his lord that his calculations were wrong.”

Holo met him with a confused look, and he continued.

“We’ve only heard Meyer’s claims so far. It means it’s technically possible that saving the forest might not be the right thing to do, despite what he says.”

“……”

Holo’s eyes glazed over, as though she could not believe what she was hearing. It was like she was telling him that there was never a good reason to cut down a forest.

With a sigh, Lawrence launched into an explanation. “In storybooks about the forests and their spirits, good and evil are always clearly marked. And so, if we were being asked to save the lord’s beloved woods, then the answer would be easy. But when it comes to gold, silver, and those whose lives they support, what is good and evil becomes much, much more complicated.”

Holo’s tail gave a sullen twitch.

“Do you mean to claim that fool was lying?”

“I don’t doubt your ears. But we can’t say anything definitive about the things he didn’t bring up at all, can we?”

Holo pursed her lips.

“Let’s talk about land used for planting wheat, for example. Is it right to keep the forest intact when there isn’t enough land for wheat? By cutting down the trees, villages will thrive, and some people might even be saved from starvation. It’s entirely possible that this Lord Tonneburg and his people both want this, while Meyer is the only one who doesn’t. He came to us for help because he didn’t want to lose his precious woods, right?”

It wasn’t impossible that Lord Tonneburg was thinking of his people first and foremost when he decided to work with the town of Karlan to clear the forests. If that was true, then fulfilling Meyer’s request would ruin those plans.

If that were to happen, it would be very easy for them to track down Lawrence the Nyohhira bathhouse owner, which would obviously cause problems for them in the future.

“Of course, I could simply decide to do this for you, because you always want to protect the forests.”

Holo glanced at Lawrence when he said this, then looked away in a pouty huff.

This wolf was not a wicked pagan spirit that could not care less about humans. She had faithfully kept her promise to a human villager for centuries, presiding over Pasloe’s bountiful wheat harvests.

And because of that, it was unlikely Holo would be any happier if they decided to keep the forest intact only to condemn a great many to poverty.

Lawrence had spent many years in the world of trade—a crossroads of countless interests. Before his eyes, he could see rows upon rows of scales, tipping in every direction, weighed down by various choices.

“Or…,” Lawrence began, deciding to ask just in case. “…was Meyer a spirit?”

If he were, then Lawrence would knock away all the scales on the table and replace it with a war map. He could completely disregard the interests of the human world and fight for the livelihood of the forest with the same enthusiasm he did when he decided to become Holo’s life partner.

Perhaps his intentions had gotten across to her; the fur on her tail perked, but it had apparently been an unconscious motion.

Realizing how her tail had reacted, Holo gave him a hard glare and said with a sigh, “He is human. Though he smells of earth and wood, I also caught the scent of gold and silver coins. Like you.”

If there was one thing that definitively separated Lawrence and Holo, it was not Lawrence’s lack of ears and tail. Nor was it the gap in their lifespan.

It was their differing attitudes toward money, and their attitudes toward loss and profits, which could also be called a sort of faith.

“Thought so. That makes this about trade, then.”

Holo would of course want to jump on a request to save a forest from being cut down, but this was not a remote mountain inhabited by spirits—this was a land that supported human livelihood.

And the mechanisms that made up the human world were complicated.

“You plan to turn him down?”

Her tone was thorny and did not sound genuinely reproachful, but it was a sign that she would not be backing down without a fight. Even Holo, who was the one typically admonishing Lawrence for constantly sticking his nose into trouble, was not going to easily give in when it came to preserving the forests.

And Lawrence, of course, felt responsibility for their actions in Salonia, which had unintentionally affected the Tonneburg Woods—and there was Holo, too.

Yet despite all that, Meyer’s request came with all sorts of concerns that made Lawrence want to decline it.

That was why there was a part of him that wished Holo would lie to him and say that Meyer was not human.

After that thought crossed his mind, he sighed. Though Holo was a heavy drinker and constant snacker and told lies over the silliest things, she would never treat such an important moment lightly. And so, there was only one person here who could fool the selfish former merchant who always put his own safety first.

And that would be the part of him that used to be a smooth-talking businessman.

“Anyway…,” Lawrence began with a deep sigh; one of Holo’s drooping ears pricked upright. “Whether Lord Tonneburg’s decision is right or wrong, there is something strange about the way the town of Karlan is acting.”

Holo’s reddish eyes slowly turned in his direction, wide open.

“The original plan to lower the lumber tariff didn’t go well, so they’ve set their eyes on the Tonneburg Woods looking for cheap lumber. That makes perfect sense from a commerce perspective. But there have been rumors that Karlan might be lowering their own tariffs.”

“Mm…hmm?”

Holo’s expression was complicated, unsure what to make of this news.

“Karlan is letting go of their precious tax revenue. Yet they’re pointing their finger right at Tonneburg in search of cheap lumber. They’ve even come up with a rather expansive plan. On the surface, it doesn’t seem to add up. Because if they don’t have enough money to buy lumber at current prices, then they shouldn’t be so willing to lower their tax revenue.”

Holo dipped her head and looked to Lawrence for a brief moment, before her eyes drifted upward.

“I…suppose that’s true. But are you absolutely certain that Karlan is not going through the same troubles as the other city where you went on a rampage?”

She made a very reasonable point. As expected of the Wisewolf.

Just like how the lumber tariffs in Salonia affected Karlan downriver, Karlan, too, was perhaps nothing more than a passing point for the lumber that would continue traveling to their final destinations elsewhere. That meant it was possible that there were people out there besides those in Salonia and Karlan who had an interest in cheaper lumber and lower tariffs.

“Mm. ’Tis strange, then. Are the lowered tariffs in Karlan affecting lumber alone?”

If anyone asked Lawrence to name what he liked about Holo, he would undoubtedly say that he adored how she was smarter than him.

He cleared his throat, trying to hide his delight.

“From what I’ve heard, it won’t just be lumber, no. That’s why there’s something strange about this. Something big must be going on behind the scenes in town.”

Holo drew up her shoulders, legs still crossed, and grasped at her toes.

“If so, then…what?”

There was an obsequious look in her eyes because she knew that the situation was going to turn out much more complicated than she anticipated, despite how reluctant Lawrence was. That is to say, he had found a reason to turn down Meyer’s request.

In all honesty, that was what Lawrence wanted to do.

But everything could change with a single thought.

“Think about it for a second.”

“Hm…?”

“I’m saying there’s something even bigger looming over this town.”

Perhaps the reason the astute Holo had not noticed was because Lawrence’s attitude had been much too careless. This was a horse dangling a carrot in front of its own nose, after all.

“Karlan has drawn some kind of grand picture, and Tonneburg is about to sadly lose its precious forest. And when things get this big, you know what’s usually hidden in between the lines, right?”

“Mm…”

“A chance to get incredibly rich. Right?”

“Ah.”

When they had journeyed together when Lawrence was still a traveling merchant, Holo would give him a cold stare every night whenever he went wide-eyed thinking about a scheme to earn a heap of coins. Those were his ambitions—and they were entirely gone now.

The reason he had discarded them was because he had found something more important to him than gold, and he wanted to keep that safe.

That something turned out to be Holo—whose wolf ears were flitting this way and that. There was an apologetic, yet expectant look on her face as she peered at him; it was a hard expression for her beloved to ignore.

Lawrence decided to consider this a favor and said, “I’m talking about a whiff of gold, one that’ll attract this former merchant who’s also a massive fool.”

There was a glint in Holo’s eyes, and her tail thumped against the bed like a puppy’s.

Lawrence set his jaw and steeled himself, not letting his expression melt like he wanted.

“I’m going to ask you one more time. You didn’t sense Meyer telling lies or anything, did you?”

Holo’s ears pricked upright at the question, and she shook her head.

“He did not behave as though he was making something up.”

When he got his answer, all Lawrence could do was sigh.

“No hard feelings if it doesn’t turn out the way you want, okay?”

Cutting down the forest might turn out to be for the people’s sake; they might even earn Lord Tonneburg’s ire and have to protect the bathhouse. Or perhaps Karlan was planning something unbelievable, including encroaching on the Tonneburg Woods. Worse, Lawrence and Holo might not even see a single silver coin in profits if they got involved.

Yet the wisewolf, who would live a much longer life than Lawrence, repeated what she told him not too long ago.

“It will still be a part of my memory, traveling with you.”

It did not matter what happened, so long as they were together. No matter how lonely she was, or how bored or pained she was, it was all proof that she was alive now.

A priest might consider it a terribly decadent way of thinking, and it almost sounded like it was just a convenient excuse in their current situation.

And in truth, it was nothing more than an excuse.

It was easy to find pessimism in the world; because of her pessimistic outlook, Holo often found herself wanting to stop traveling with Lawrence. It was Lawrence himself who thrust that mindset of hers aside, and in the end, she found that she truly did wish to spend her life with another.

And when she did at last, she found ahead of her days filled with joy.

“You’re a sly wolf, you know that?”

In the end, perhaps this had always been the obvious choice to begin with.

If either of them lived sensibly and only ever made smart decisions, then they never would’ve walked hand in hand.

“…A wolf never lets go of her prey, you know.”

She took his hand in hers, her smile filled with genuine gratitude.

She was more precious than gold, a reward more decadent than the finest wine.

Lawrence smiled at his own foolishness, tugged on her hand, and pulled her into an embrace.

Then, after that brief moment, they returned to Meyer to tell him they would take on his request.

The hostlers, who took horses along the riverside for those who chose to travel by boat, arrived at the checkpoint a day later. Lawrence received his horse from them and then found a merchant who would be staying at this very checkpoint for a little while longer. He negotiated with this merchant, placed several silver pieces on a contract that would allow him to secure a cart in Karlan, and managed to borrow a cart off the merchant. Though it was a bit on the older side, they were in no position to be picky.

“An agreement on a single sheet of paper and nothing more than a handshake. Your exchanges are odd, as always.”

Just like that, he made a deal with a stranger to secure an item they were not even sure existed. Exchanges based on the trust among merchants were still an odd sight to Holo, despite how many times she had seen this concept in action.

“But I think the strangest of all those agreements is everlasting love based on nothing more than a kiss.”

Holo, who had been poking at the sacks of powdered sulfur with her foot, did not blush at that statement, of course. She only scoffed.

“Aye. I have certainly been taken in by someone’s honeyed words, have I not?”

“I believe you are being delivered the exact product you signed for in the contract, ma’am,” Lawrence said as he began to load the cart bed after tying up the horse, and Holo gave a dauntless smile.

She then leaped into the cart.

“I suppose it could be worse. Especially considering the situation.”

She leaned her knees against the edge of the cart, resting her elbows on them so she could prop up her chin with her palms. A suggestive smile crossed her face.

“It will be worth the hard work.”

After she cheerfully flashed her canines, she finally began to grab sacks of sulfur and helped place them on the bed of the cart.

Once they were done, Meyer arrived on horseback.

“Have all your preparations been completed?”

“Yes. Lead the way.”

Holo, who had sat down on the driver’s perch before him, scooted to the side to give him room. Lawrence climbed up and took the reins.

It was clear from the get-go that Meyer was a ranger for good reason—he handled his horse with incredible skill.

Though he spent all his days on horseback, roaming the woods, he only looked like a simple peasant on the outside. In reality, he was a vassal who directly served the nobility. The shortbow on his back was not for show, either; whenever he spotted a wild rabbit, he drew his bow and shot it from horseback. Even the most skilled hunters would not be able to accomplish such a feat without special training. Not to mention that it was also a martial art that had use in battle. It was not hard to imagine him mercilessly feathering any intruders he came across in the forest, and he likely knew his way around a blade as well.

It was also notable that he did not ride alongside Lawrence and Holo as they traveled, likely because he often acted as a guide when his lord went out hunting in the woods.

The ranger basically treated them like nobility. He hurried ahead to check the roads, brought any rabbits he hunted to the inns they passed, and even arranged for a meal and lodging with the innkeepers. As night approached, he took them to a small church in a nearby town, where they had a lovely evening with a mild-mannered old priest.

If Lawrence were on his own, the best he would have been able to manage would be finding a cheap inn full of lice and fleas, camping outside by the fire, or borrowing a straw bed if they happened upon a village. Even that was only possible if they were lucky.

There were plenty of very good reasons why Holo was reluctant to travel over land.

“I am beginning to wish we had an attendant of our own,” Holo said the next morning once they left the church.

It was likely an allusion to how Lawrence had taken so long to start a fire when they first left the mountains of Nyohhira, but Lawrence decided to pretend not to hear it for the sake of harmony in their family.

After a while of traveling, Meyer eventually got down from his horse ahead of them. As Lawrence turned his attention ahead, he spotted a dilapidated bridge over a small stream.

“This is quite old,” he remarked. “Is there anywhere we could cross on foot?”

The stream beneath the bridge was nothing more than a long, thin puddle—calling it a river would be much too flattering—but the water itself was surprisingly clear. The water’s edge was thick with grasses, some spots home to small copses. It was at this moment that Lawrence realized that, at some point, the flat plains had vanished and given way to hills and trees.

“Water wells quite frequently in this area, so there are many brooks such as this one,” Meyer explained. “I’ve heard that there was once a great river that flowed through here in my grandfather’s grandfather’s time.”

Lawrence immediately knew he was talking about the great serpent, said to have been cut down by a great hero.

Though he had not been conscious of it, it seemed that the river that once existed near Salonia flowed into this land.

“The ground is damp wherever you go, so a failed crossing could mean getting a cart wheel stuck in the mud, forcing a stop.”

Lawrence nodded and glanced to Holo.

With an annoyed sigh, Holo clambered down from the driver’s perch and began unloading all the sulfur they had packed back at the checkpoint.

“May God help us.”

Lawrence pretended not to notice the scowl on Holo’s face as he made a rather genuine prayer to the heavens, pulling horse and empty cart across the bridge.

He could feel sweat trickling down his temples at the ominous creaking of the bridge below him as he came to realize one reason why Tonneburg managed to preserve such a vast forest. Though there were no big mountains in the area, the land was not flat, either. Ponds and rivers also dotted the landscape. This kind of land could not be turned into arable fields, and ground where drainage was poor meant disease spread more easily—in other words, it was not suitable for human settlements. The geography also made it very difficult to attack in wartime.

That the land was so difficult to use played a role in why Tonneburg had managed to keep the forest largely untouched until this day.

“Seems like we made it across.”

Lawrence would not be the least bit surprised if, on their way back, they found the bridge collapsed and starting its new life as a home for the small fish and shrimp that lived there. The reason Meyer always went ahead to check the roads was intended to be a deliberate show of kindness, but it was also because the terrain was genuinely dangerous to traverse.

“Let us be off. We’re almost there.”

Though this was a far cry from a relaxing journey, the reason Holo was not terribly upset about it was perhaps because of the smells of the rich earth and water—the scent of the deep forest hung over them. It was potent enough that Lawrence could smell it, too.

It was not long after that Meyer, who had set off ahead at a quicker pace, came into view again, standing at a fork in the road. One path continued on south, while the other looked like a small game trail that curved westward. At the far end of the latter, Lawrence could see the dark, dense wood.

Tonneburg was comprised of several small villages that surrounded the forest, and one of them acted as the heart of the territory. Incidentally, the settlement was big enough to have its own market. Lord Tonneburg’s manor sat apart from the villages, on the bank of a pond to the south of the forest.

The road Meyer had used to bring them here led to the largest village.

That said, the road was barely recognizable as one, and it did not seem that merchants and travelers often came from the outside world.

As Meyer guided them down the path, Lawrence and Holo noticed a person along the road.

A lone old man sat on a tree stump, and the moment he spotted the two of them, he rose to his feet. Evidently, he had been waiting for them.

Meyer told them that he was the mayor of the village they would be entering soon.

“Ah, there you are! The merchants that come to our market have spoken of you. You solve business problems with magic!”

“Magic? Oh, no. Only God’s guidance.”

It would only cause problems for Lawrence later down the line if a superstitious village believed he was genuinely a wizard, but the look on the mayor’s face made it seem like his village was on the brink of collapse. He ignored Meyer’s introduction and began to speak, clearing his throat.

“If all the trees are cut down, then we cannot maintain our livelihood. And that’s not all—a great calamity will befall the entire region if this comes to pass!”

His speech was exaggerated, like a pastor giving a sermon. Though Holo gave a docile nod, Lawrence wore a merchant’s mask.

A merchant who took every hyperbolic proclamation at face value was worse than useless, and the mayor seemed sensitive to that.

“It is not mere parable, Great Merchant.”

Lawrence showed his shock, and the elderly man’s glassy eyes bore straight into him.

“Our lord understands nothing. How are our pigs and goats supposed to grow fat if he cuts down our forest? And does he understand what sort of state that would lead to?!”

Meyer did not stick around to rein in the mayor, who leaned in as he talked to Lawrence and Holo; their ranger had, as always, gone ahead to check the roads.

After glancing briefly in his direction, Lawrence asked, “…Pigs?”

In all honesty, he had assumed the old man was concerned about the potential clear-cutting because of a pagan attachment to the woods. That and complaints about being forced into hard labor when the clearing process began in earnest.

Yet what came out of his mouth was talk of goats and pigs, which Lawrence had not been expecting.

Satisfied by his bewilderment, the mayor gave a deep nod.

“The villagers speak of the forest’s bounty, but the honey and nuts one can find among the trees is a trivial matter. Even the lumber is not the greatest thing the forest provides. What we cannot afford to lose is the nameless undergrowth.”

Lawrence could not bring himself to put on a fake smile or offer amicable agreement; instead, he found himself glancing at Holo for her wisdom. But even Holo, who was supposed to be thoroughly knowledgeable on all things regarding the forest, simply looked back at him with a quizzical expression.

“The forest undergrowth is what keeps our goats and our pigs fed. You must know that the horses pulling precious cargo for traveling merchants like yourself—those all-important beasts of burden—are raised on oats that grow wild in the forest.”

Wild oats that were too much like grass for human consumption were sold as horse feed. Lawrence knew that, of course.

“If the undergrowth vanishes, then goat milk and pork will not be the only things we lose. You came from Salonia, yes? You must have seen the impressive fields of wheat they have over there.”

For the third time, the conversation took another wild turn, and vexed, Lawrence struggled to find the words.

“Er, yes… They truly were impressive…”

“Yes, yes they are. But our Lord Tonneburg also does not understand that all the wheat fields around Salonia thrive on livestock manure.”

It was as though the old man had been pruned of all of his excess after many long years of farm labor. There was powerful conviction in the way the mayor spoke, and he wielded a persuasiveness that was hard to resist.

Lawrence, too, had once traveled the world as a peddler, the kind of person who in a sense also worked to support the bottom rungs of society, and was confident that he had seen all the fine detail the world had to offer.

But what the mayor was talking about was something that supported the world from its very root, something that would never enter a traveling merchant’s view.

“Those who never sully their hands with dirt could never imagine the sheer amount of grazing needed to keep the livestock fed. The grasses that grow in fallow fields and plains could never be enough. It is the Tonneburg Woods that single-handedly provide what other territories lack. If Lord Tonneburg understood how hard we work, how much we trade in livestock manure, then he would look to the heavens in astonishment and exclaim how rich in trade his land is!”

All merchants could see were the final products that came to market. Even merchants who dealt in herring egg futures never handled livestock manure, much less gave a first or second thought to pig or goat feed. As far as they were concerned, livestock simply lived off the land, and there was no need to deliberately spend money to feed them.

As Lawrence failed to find his words, he stared at Meyer, who had failed to mention any of this back at the checkpoint. Perhaps the easygoing atmosphere surrounding the merchants and travelers at the checkpoint was so powerful that he was convinced talk of rich soil would go unheard and unheeded.

There was always a suitable time and place for any topic.

And that was never truer than this moment now.

The shrewd Meyer at last spoke.

“Sir Lawrence, while part of my role entails protecting the forest from illicit logging, my main responsibility is actually to make sure no one lets their livestock roam and graze on the grasses without express permission.”

“Livestock manure is gold for the fields. Whether scattered seeds of wheat yield three or seven times the amount planted depends entirely upon whether or not the field has been treated with a veritable deluge of manure. And the quality of that manure is affected by how much the livestock has been fed.”

It was not unusual to find wheat fields that only produced three times the amount of seed planted. That was only enough to feed the farmhands because after setting aside the seed needed for planting the next year, nothing would be left. A year of bad harvests would plunge many farmers into immediate poverty. Regions known as breadbaskets that lined their market stalls with heavy-laden bags of wheat needed a yield that was five times greater than the amount of seed they planted. Even lands known for being fertile would thank God for a rich harvest that offered sevenfold yields.

Lawrence finally managed to understand this with the knowledge he gleaned from his days as a traveling merchant only because it strayed close to the markets, which he understood well. To think that fertilizing the land with livestock manure was this important, and that the forest’s undergrowth was critical to raising livestock.

He had spent quite some time traveling from village to village dealing in wheat during his merchant days, so Lawrence thought he knew everything there was to know, but it turned out there was plenty he had not learned about at all.

“If Lord Tonneburg proceeds with cutting down the forest, then not only will we be forced to contribute labor, but the forest will lose its undergrowth, the livestock in the area will grow skinny, the wheat fields will wither like a dried-up river, and all of us will lose our livelihoods.”

Holo, who had spent centuries in a wheat field, understood where the conversation was going from the very beginning, and in all likelihood had subtly turned Lawrence toward this problem.

When that thought crossed his mind and Lawrence looked to the side, he saw Holo glowering at him from atop the driver’s perch.

He thought she might be angry about the danger to the wheat fields, but from the way she refused to meet his gaze had him belatedly realizing something else—farming techniques that used livestock manure were more beyond a spirit of the forest than a merchant like Lawrence.

Then he recalled how, after commanding the harvest in Pasloe for centuries, she had been rendered obsolete and had practically been chased out due to advancements in human agriculture. The mayor still rambled fervently about tree types and how the undergrowth grew in relation to them, and the relationship between livestock grazing periods and the wheat harvest, but not once did God come up.

The era in which people left offerings in the dark, sunless forest to pray for a good harvest had long since passed. Holo was more than ready to protect the forest, but the forest was no longer home to beings like her.

“Do you understand, Great Merchant?”

This brought Lawrence back to the moment, and his gaze turned from Holo to the mayor.

“The Tonneburg Woods supports the wheat harvest at its very foundations in every place reachable from here by cart. But our lord has forgotten how the land operates and has been taken for a ride by those blasted sea dwellers,” the mayor spat.

Meyer added, “Seaside ports operate on vastly different logic from landlocked settlements. To them, wheat is but one of many products that pass through their walls. They likely think they can simply import wheat from overseas with their boats to sell them at a high price during years of bad harvest.”

To Lawrence, who once gladly took on whatever product he thought might make him a quick profit and carted them from town to town, this statement was a bit hard to swallow.

“But the reason Lord Tonneburg made an agreement with Karlan is, well…there is a sort of rationale to it.”

Just as Meyer spoke, the crude road—nothing but cut grass to mark where one was meant to walk—became the familiar sight of packed earth, and Lawrence caught sight of small clearings and farmland along the treeline.

It seemed the local wheat harvest ended long before Salonia’s—perhaps they reaped the wheat earlier.

“It is not just our lumber that Karlan is after. They want to build a road through the forest and change the maps.”

“The maps?” Lawrence asked in turn.

As he did, the center of the village came into view. In the center square stood a modest market, stalls lined with harvested grain and other miscellaneous vegetables, as well as honey and the bounty of fruit trees harvested from the forest. A great number of people and carts packed the rows, more than the size of the market might’ve suggested.

It was the familiar sight of a small, yet lively farming village.

“Lord Tonneburg wants to sacrifice the forest to ensure this market remains on the map.”

As Lawrence began to nod, he realized something was strange about that statement.

“But if the forest is cut down, then this place would vanish, too.”

Though the village sat beside a deep, dense forest, it did not seem as though its main industry revolved around lumber. What supported its economy was the forest’s fertility, which greatly benefited the soil and the livestock.

“Lord Tonneburg believes the scent of wheat and honey can be replaced with metal and coal.”

“Those metalworking shops will fill this entire region with the smell of burning wheat fields.”

Meyer had mentioned that Lord Tonneburg had made a miscalculation at the checkpoint tavern.

And that miscalculation would not only affect the Tonneburg Woods, but also the vast majority of Salonia’s wheat fields.

At last, Lawrence began to understand—this was one appraisal that they could not afford to get wrong.

CHAPTER TWO

The situation called for extreme caution. It was unusual for the village to receive visitors, much less outsiders who had come for the sole purpose of dismantling their lord’s plans.

Lawrence had the sense that even the head of the village, who had come with Meyer to welcome Lawrence and Holo, viewed the two of them as a necessary evil. That was probably why he described Lawrence resolving trade disputes as magic.

And so Lawrence would be staying in the village as a guest of the church, just as traveling merchants who came to trade did.

The priest was the perfect picture of a good-natured old man. He welcomed Lawrence and Holo without ulterior motives and knew of what happened in Salonia as though it were common knowledge. He was eager to hear about the legendary independent priest who built a trout hatchery, and so Lawrence told him of Bishop Rahden, who hailed from warm seas.

Lawrence was hoping to hear more details about the village and the forest from the priest, but the old man was a fervent believer first and foremost; though the villagers respected him, he was not at all knowledgeable about the village or the region’s economy. “All I hope for is peace for the souls of Lord Tonneburg and his people,” he said sadly. Had Elsa been there, she would have rolled her eyes at this, especially since she traveled all over to reform poorly run churches.

And so, dinner was delightful, but ended fruitlessly.

Holo seemed unsatisfied with the scant servings of meat at the serene meal. The moment she settled down in their guest room, she immediately undid her pack to fish out some jerky.

But she was not as cheerful as she usually was; she only silently sipped on the mead Meyer had gifted her.

Though the forest was still in danger, the villagers were not particularly worried about the forest itself, much less the spirits that might have dwelled there. Their greatest concern was the livestock manure. Though she knew it was unreasonable to get angry over this, it was still enough reason for her to sulk.

In contrast, Lawrence had only just begun to understand the weight of the situation. And to make up for what he believed was a lacking dinner, he had gone to the priest to borrow something from him.

“What is it you’ve borrowed?” Holo asked dubiously, peering at what he unfolded over the writing desk.

“A map.”

Meyer had mentioned that the port city of Karlan was hoping to redraw the maps. He had also mentioned that Lord Tonneburg had decided to cut down the forest in order to preserve the lively village market.

The trick to trade was considering things while standing in another’s shoes.

“People always gather in churches for one reason or another. Church maps will always be reliable.”

“What am I looking at?”

Not many people could read letters, and that mostly held true for maps as well. The majority of people never left the village where they were born, so they never had any need to look at a map. That was especially true for a wolf who never lost her way even in the darkest forests at night, who only needed to bound up the side of a mountain to find its peak and gaze into the distance to confirm exactly where she was going.

Yet Holo had read her fair share of maps on countless occasions because she had sat side by side with Lawrence, gazing at them under candlelight.

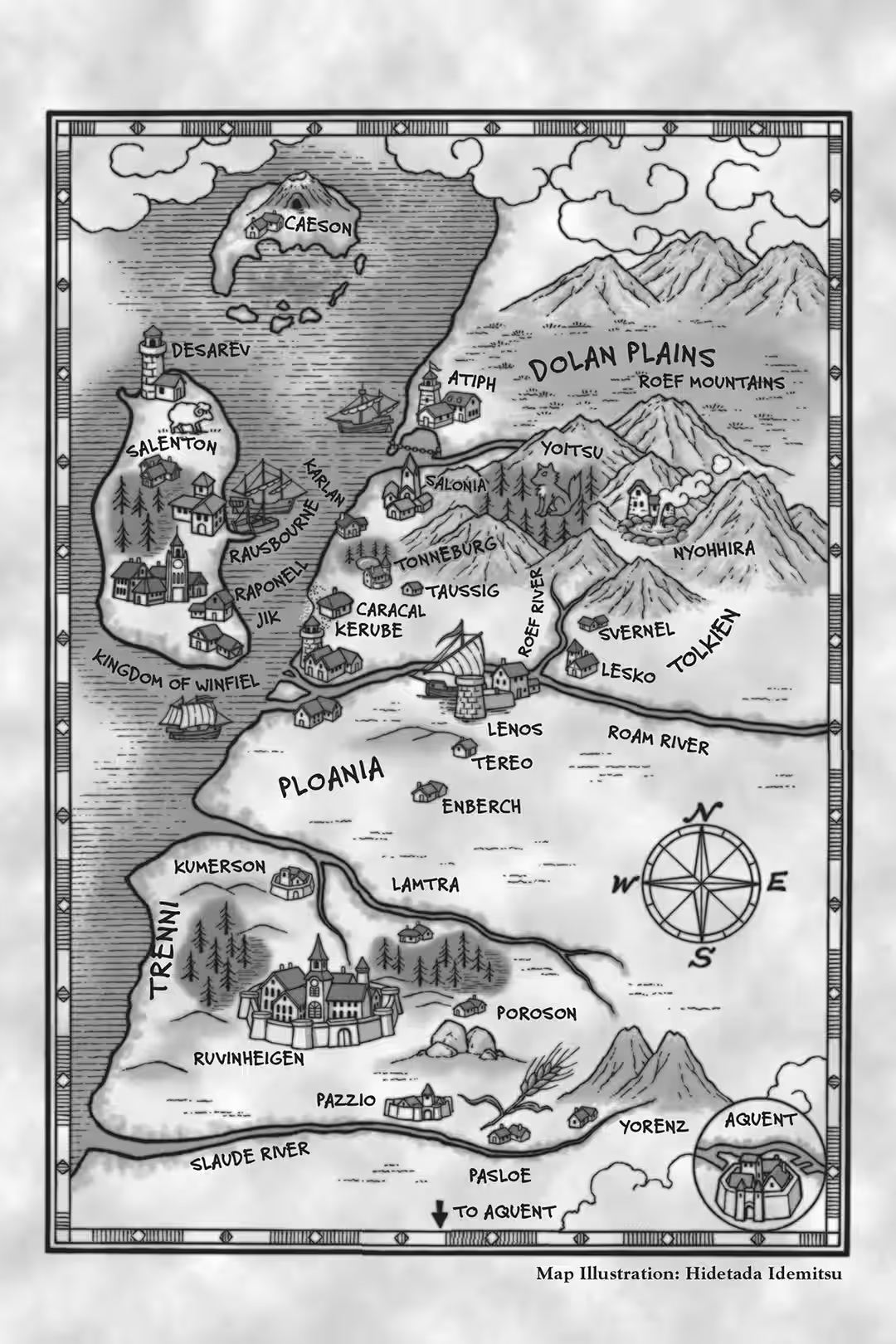

“This is way is north, and this is the river we came down by boat. We then went south, and we should be around here now.”

The river that flowed from Salonia spanned the map from right to left, running across the top. Salonia stood on the rightmost edge, and downstream—on the leftmost edge of the map—sat what was likely the port town of Karlan. At the bottom of the map, south of the forest, was what looked like a large pond or a lake and a small drawing of what was likely the ruling lord’s manor. Below that, farther south, was a road that ran east to west, marking the bottom of the map.

Occupying everything between the north and south edges of the map was an all-consuming gray mass—the forest.

The village in which they were staying sat right on the northeastern edge of the massive forest.

“According to Meyer, they want to cut down the forest so they can build a road that goes south.”

An uncomfortably loud crack came from inside Holo’s mouth—she must have bitten into an errant piece of cartilage in the jerky.

The candlelight shone in her red eyes, and her canines gleamed.

“Fools,” she said, ripping into a new piece of jerky.

“In a merchant’s eyes, Karlan and Lord Tonneburg’s plans do make sense.”

The forest spread from the northeast to the southwest, dotted in places by what Lawrence surmised to be hills by name alone. This was not an easy wood to cross, and the seven or so villages in the area sat outside the forest. The only two settlements among the trees sat just inside the perimeter—the forest was truly untouched.

This map was marked with paths to show where church visitors should visit next, and all these paths took great winding detours around the forest.

“This is Karlan, the port city. And I guess at the bottom here, this area south of the forest must be a pond or a lake. Either way, there’s another small river flowing south from there. And that means if they manage to cut a path through the forest and build a road to the lake, they could easily carry cargo from north to south by boat. And voilà—a convenient trade route.”

If there were a road that went from the north of the forest to the southern lake, then they could build a pier there, along with warehouses to store cargo and inns to house travelers. Merchants would naturally follow. And due to the dense woods, they would not lack material to raise buildings and build boats. Setting up charcoal-burning huts and smithies would be the first thought of any merchant.

The road would connect north and south, opening the way to seaports—it was the perfect trade route for exporting metal, charcoal, and lumber. Lawrence could easily imagine the booming business the village would see.

“If people use the road, then the landlord can collect taxes. Lumber will sell like hotcakes. Before long, new villages would pop up and the population would grow. This map would change dramatically.”

Holo’s tail swished back and forth in displeasure.

“But it was said that if they do not accept this plan, then the fires of this village will be snuffed out. Why is that?”

She pointed to the village in which she and Lawrence were staying.

If he were to look out the window, he might be able to see the tip of a giant shapely finger.

“That would be because of where Karlan is located. See, look at the forest—” Lawrence pointed at the Tonneburg Woods. “Picture an even bigger map, one that contains the woods and everything around it. This forest stands in the way of Karlan doing any trade with landlocked communities. They have no choice but to rely on the river flowing from Salonia, but that’s also obvious to the lords who hold land along the river.”

Holo lifted her head, then nodded. “They are under their thumbs.”

Even if ships could reach their harbor, Karlan would have no choice but to watch the products in their warehouses rot if they were unable to do trade with the villages and towns farther inland. The only easy path into the rest of the continent was that river, and if Lawrence were one of the landlords along the river, then he would capitalize on that leverage without a second thought and levy heavy taxes at his checkpoint.

That was precisely why Karlan wanted a different path that would allow them easy access to the rest of the continent.

Holo played with the piece of jerky sticking out of her mouth.

“If Lord Tonneburg were to turn down Karlan’s proposal, then the new road would have to take a large detour around the western edge of the forest. They probably used this to threaten the lord.” Lawrence traced a finger along the left side of the map. “A new road on the western side of the forest would completely divert the small, but steady, trickle of merchants that pass through this village on their way south. The merchants from Karlan, at the very least, would have no reason to come to the eastern side of the forest, especially when their return trip would require traveling by river with high travel tolls. And so trade that only existed because merchants incidentally stopped by would vanish, and the villagers would have to venture elsewhere to sell their wares. And that’s doubly true when there aren’t any decent roads.”

Holo quietly chewed on her jerky, which was still sticking out of her mouth. She was likely thinking back on the rickety bridge they had to cross to get here.

“That said, I’m sure there are reasons why Karlan doesn’t necessarily want to build a road that runs along the western edge of the forest. If there weren’t any, then it would probably be under construction right now.”

It was hard to tell due to how the map was cut off, but Lawrence was almost certain there already existed a road somewhere toward the coast. If that road and the new one were too close, then it would invite conflict with the lords who owned the lands along the coastal route, among other problems.

It was likely that Karlan had recently gained ambitions to develop and flourish as a port city. But it was surrounded on all sides by powerful individuals who were already well established—there was not much room for Karlan to carve out a niche.

In his mind, Lawrence pictured a child who was physically growing, but was uncomfortable due to their small clothes.

“Building a new road isn’t very easy to begin with,” Lawrence said, his gaze dropping to the flask of mead in Holo’s hands. She glumly handed Meyer’s gift to him. After a sip, he returned it to her and continued. “It’s easy to collect taxes on a river, but that isn’t the case with regular roads. And so landlords typically make up for the cost of building those roads and their maintenance by forcing the commonfolk who live nearby to work on it. Those people have no choice in the matter—they typically spend three or four days a week laboring with absolutely no compensation. And in the meantime, their fields go neglected, and their lives get harder. I honestly thought they were going to tell me that their village was going to die out because of these troubles.”

But all the mayor talked about was the cycle of the livestock, the manure that fertilized the wheat fields, and the forest that supported the livestock.

“What we know so far makes it seem like even if they are forced to work on the development of the land, it won’t be so bad. That means Lord Tonneburg is probably a better person than we think, and that he has little intention of exploiting the villagers. But in that case, something else will have to make up the difference.”

Holo brought the flask to her lips but did not drink. Her intelligent eyes stared at the map.

“Building a road is hard enough under normal circumstances. It’s that much more difficult to do in heavily forested land. At the same time, they’ll get quite a lot of lumber from cutting down trees to make room for the road. And they could easily make up for the cost of building the road after factoring in the profits that will be generated by the smithies and other things that come later. Karlan seems to be especially keen on getting lumber, so even if they compromise on a great deal with Lord Tonneburg, they probably thought it all added up. And from Lord Tonneburg’s perspective, he probably thought it would be more beneficial to take them up on this proposal instead of watching helplessly as a new road wraps around the forest…even if it means losing a part of the forest’s wealth.”

“Mm.”

“And Meyer seems to be a skilled ranger. I bet Lord Tonneburg already asked him to find the best route through the forest.”

It was then that he and the Karlan council saw they could both profit from this and decided to work together.

“That’s what things look like in the merchant’s world,” Lawrence said. “What does the wolf think?”

Holo huffed a little sigh at the question, readjusting her position on the bed. She then whipped her head to the side, ripping apart the sinewy jerky in her mouth; the only times she ever really acted wolflike in this manner was when she was in a bad mood.

“Only the most witless of fools would build a road here.”

Lawrence looked at the map, and then to Holo. “You mean like how the mayor explained?”

Everyone would lose everything the forest had to offer. Even if Holo did not quite understand how the manure from free-roaming livestock fertilized wheat fields, she was intimately familiar with how the plants in the forest grew after watching them for countless years.

“Humans will walk here, they will burn charcoal along the paths, and then create metal, no? At that point, the road ceases to be a simple path in the forest. It divides one wood in two, creating entirely separate places.” Noticing Lawrence’s weak response, Holo continued with a sigh. “Shall we consider the fox?”

“The fox?”

“You merchants think of the land in your reliance for roads for your cargo. That makes you a cat. Cats claim the paths that go from house to house.”

Interested, Lawrence turned his chair to face Holo completely.

“These landowning lords are stereotypical mutts. They draw the lines on their papers telling everyone precisely what belongs to them.”

“And what about the foxes?”

“Foxes appear to be like both, but they are exceptionally greedy. They cannot live in smaller forests. Splitting a large wood in twain does not create two territories. It will simply be too small for the foxes, and then they will no longer have any place to live.”

Huh. Lawrence was impressed, but he was not entirely sure how this was relevant. Sensing this, Holo looked at him like he was a disappointing apprentice.

“No foxes means more rats, and without any predators, the fawns will thrive.”

“Hmm. I guess you’re right.”

“An excess of deer and mice means saplings shall be eaten away, and that will cause the forest to grow thin. All that will remain will be higher trees that are covered in needly leaves, making the wood dark and quiet. ’Tis not a suitable wood for fattening pigs and goats.”

The needly-leafed trees she mentioned were likely conifers. Broad-leafed trees, ones that struggled to reach greater heights, made easy meals for deer and other critters of the forest, so only the taller coniferous trees could survive uncontrolled booms of wildlife. And when the canopy inevitably started blocking sunlight from reaching the forest floor, new grasses would not grow there. Just as the mayor so passionately proclaimed, it would have a huge impact on the undergrowth that indirectly supported the wheat fields.

“’Twould look like a nice acorn—one full of holes that has most certainly been hollowed out by pests.”