Contents

PROLOGUE

With a small whetstone, one that fit in the palm of his hand, he sharpened the blade of his old knife.

Though its only real purpose was for emergencies during his travels, it was plenty sharp enough to nick his finger if he was not careful; the focus required, combined with the repetitive motions, meant this task had his undivided attention.

If he overdid it, then the blade would shrink, and if he were to take it into a local shop, they would certainly hound him about the unevenness of the blade, so he stopped when he felt it most appropriate.

With a cloth, he wiped at the newly sharpened edge of the knife. His eyes roamed the desk and eventually settled on three feathers and a small dish made of cow’s leather. A goose contributed the milky white feathers that were nearly the length of his forearm. There were only so many flight feathers on a goose’s wing, and he had always found the sight of them entrancing, often running a finger over the smooth vane while losing himself in thought.

Depending on which wing the feather came from, there was a subtle difference in the curvature. Debates over which kind fit most comfortably in the hand could continue for eternity. Personally speaking, Col had no preference—if anything, he was more concerned with the thickness of the shaft and generally liked thinner ones.

He pressed a feather into the desk with his left hand, then held his freshly sharpened knife in his right. He cut off the tip of the feather’s calamus like he was cutting a vegetable, then trimmed it diagonally. He ran a finger over the pointed edge and continued to hone it until the angle was to his liking. He had a habit of overcutting.

This usually happened because of his preference for thinner tips—he always felt like things seemed more severe that way. As an added economic bonus, he could fit more on a single page with smaller writing.

Make the tip too thin, however, and the ink would refuse to stick and the tip would be too soft, which was a terrible thing for those who tended to press hard when writing, as it made the quill more difficult to use. This was especially apparent for anyone who tensed their shoulders as they wrote, which led to a slight rise on the right side in their writing.

With a faint smile, he cut the final, vertical slit into the tip. This was where the ink would sit, and from there, new worlds would spring forth on paper. He held the tip up to the light, checking his work, then brushed dust off with a finger, before finally dipping the quill into the ink that pooled in the leather dish.

When Col thought about how all the books, all the surviving knowledge that existed in this world, began from this little procedure, he felt like one rush of water in a much larger river.

He wiped off the excess ink on the edge of the dish, then pressed the tip to the paper.

The quill smoothly drew a beautiful line over the page.

CHAPTER ONE

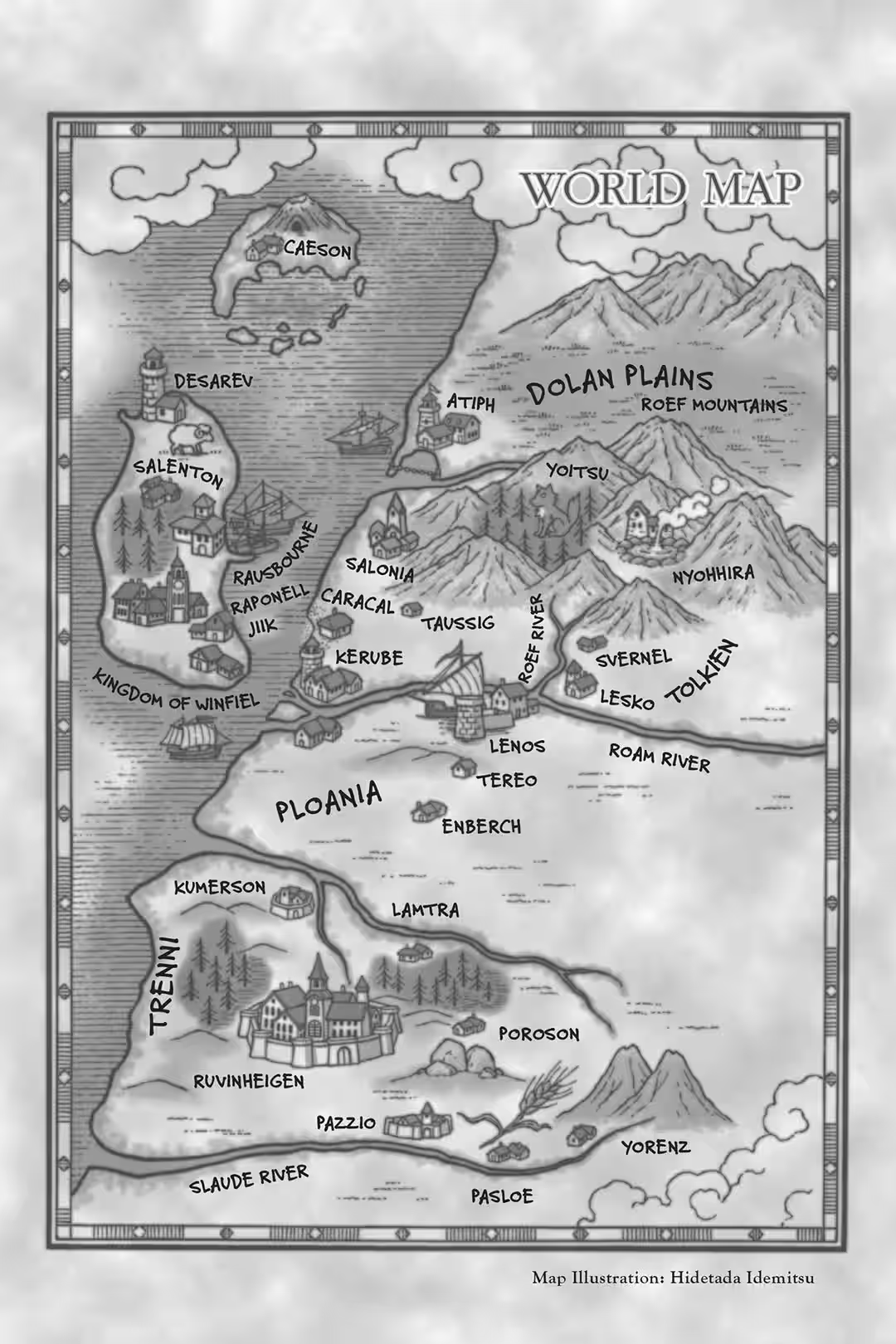

Two weeks had passed since the commotion at Raponell, where there had been ceaseless rumors of ghost ship sightings. Now Col and Myuri were already on their way back to Rausbourne.

The strait between the Kingdom of Winfiel and the mainland had a steady northward current all year round, so northward journeys by ship were rarely, if ever, dictated by bad weather. If anything, the weather was a bit too nice, and it almost felt hot standing on deck beneath the expansive blue sky.

All sorts of things had happened at Raponell, and at the end of it all, Col had come down with a fever and wound up stuck in bed. Spending a moment in the sun like this was exactly what he needed.

The more he gazed up at it, the more he felt like he might fall into the sky. Ghost ships filled with bones had become a distant tale from a distant land, like a dream he had chanced upon in the thick of a moonlit forest.

Without a cloud in sight, the sun blazed overhead. Col brought up a hand to shield his eyes and squinted; he could see faint round shapes in the sky. He had once heard that sailors with good eyesight could see the stars and the moon shining brightly beyond the blue skies, even at midday.

Col found himself looking to the sky more frequently since then.

His thoughts often went back to the metal globe he had found during the recent excitement.

On the last night dealing with the old Lord Nordstone, he had peered out the window of the forest manor and spotted the golden moon hanging heavy in the sky. And there had been a globe in the manor that looked just like the moon.

An alchemist had once lived in the Nordstone manor and presumably feared breaking taboos no more than any other student of the alchemical arts. Based on how it was treated, it was safe to assume that globe represented some of the most forbidden knowledge to ever exist.

“If that is indeed what this world looks like…,” Col murmured as he tightly gripped the crest of the Church that hung from his neck. There were all sorts of outlandish ideas out in the wild—for example, the idea that the earth rested on the back of a giant turtle or that the ocean ended in a sheer cliff. There were but a few theories that were bandied about with great seriousness in old texts.

Of course, most of them amounted to nothing more than tales to entertain children, and adults did not take them seriously. But there were some schools of thought that were certainly not meant to be bedtime stories. They might sound preposterous, but they were also strangely convincing.

There was little doubt the globe was meant to show the world’s supposed true form—a physical representation of the old school of thought that the world was round.

The Nordstone manor alchemist had apparently been searching for the new continent, only to vanish without warning one day. If she had made it her mission to find the continent on the other side of the western sea, then learning the true shape of the world would have been mandatory. And if heading directly west led only to a massive waterfall, then there would not be much to discover or explore.

“But if the Church were to find out—”

There were some things that should never be spoken aloud. Things that were not allowed to exist.

The best example of such were spirits who understood human speech and occasionally took human forms.

Col was not being honest with the Church in that regard, but what he saw in Nordstone’s manor crossed an entirely different line.

When he returned to the Nordstone manor after things had settled down, the globe he had seen there had vanished without a trace. Perhaps that could be considered a blessing. Since he never got the chance to confirm its existence with Nordstone, it was easy to chalk it up as his misunderstanding. Maybe it was just a fever dream he’d had while stuck in bed.

A part of him thought the right thing to do as a servant of God was simply forget everything he’d seen. But if he and his companions were to seek out the new continent in due time, it would inevitably become a problem. Col wondered what he should do if that were to happen. He had no answer to that. How would he react when he discovered a truth that would flip the scripture he held so dearly on its head? There was no way to know.

But if he did not prepare himself, then he would undoubtedly freeze at a crucial moment yet again. He tried to rouse himself with that thought, but his mind felt clouded, making it hard to think. A general unease had settled in his chest, almost as if he was seasick. He could feel his mood dipping, despite the rare opportunity to enjoy such lovely weather. Then the cry of a seabird and the yell of a young girl rang out across the deck, pulling him from the depths of his thoughts.

“Whoa! Hey! It’s—it’s okay! Stop—flapping!”

Col was long past feeling surprise when the familiar yelling filled his ears. With a sigh, he turned to see other sailors, much like him, staring at Myuri, who held a thrashing seabird.

“I just want a feather! Oh—hey, Brother! Where do you take the feather for a quill?!”

Though birds did not technically make facial expressions, this one seemed quite desperate. In contrast to the seabird’s fear of death, Myuri wore a cherubic smile.

“That would be its flight feather. But if you pluck it, that one will no longer be able to fly.”

“Wait, really?” She looked down at the bird under her arm. “It’d be sad if it couldn’t fly…And it’s not like we’re going to eat it, either.”

Seabirds were always a part of the scenery around ships and ports, but despite their elegant appearance, they were surprisingly violent. On Col’s travels a long time ago, they had swooped down and stolen his food on more than one occasion. But that very same sort of bird was currently paralyzed in fear of a wolf. The ruler of the forests had become ruler of the seas.

“Let the poor animal go. The birds have helped us plenty of times already.”

Though a fatigue had settled in, one that threatened to bring back his fever, Myuri’s nonsense helped him get his mind off the alchemist conundrum.

With a tired sigh, Col stood and stretched.

“Does this mean you ruined your quill already? Shall I trim it for you?”

After a moment of hesitation, Myuri let the poor seabird go. Though they typically glided along the wind without nary a flap of their wings while staring down at the flightless humans with pity, this one flapped off in a panic like a chicken.

Myuri stooped to collect the feather that fell from the poor seabird and study it closely.

“Can’t I use this one?”

“In theory, yes, but I believe it will be too small for your hands.”

She held it like a quill, but it already seemed too small.

“Geese have feathers that are just the right size.”

“And they’re tasty,” Myuri added, patting her stomach. “Is it lunchtime yet? I wonder what we’re having today!”

Amazed by her abject lack of decorum, Col poked her in the head.

“Take care of your tools.”

“I do! But I just get so into it, you know?”

It was almost as though she was blaming the quills for failing her so quickly.

In the few days following the end of the incident in Raponell, both of them had gone through little changes.

Col spent considerably more of his time staring at the sky. In contrast, Myuri started to spend a lot more time writing at the desk.

“Not only are you straining the quill, you are far too rough with it.”

“It’s because I’m writing so much!”

There was no falsehood in what she said—Myuri had probably written more in these past few days than she had in her entire life up until that point. She had never been much of a writer in the past, and Col had to practically tie her to a chair for her writing exercises.

But one night after their adventure with Nordstone came to an end, she stood before Col with writing implements in her arms and a serious look on her face. Paying no heed to his confusion, Myuri asked him to teach her the proper way to write because there was something she wanted to put to paper.

Col still had vivid memories of how much trouble he had getting a younger Myuri to sit down and learn how to read and write many years ago, so there was honestly nothing he could say to describe just how happy her request made him.

After realizing that out of all the things the Church banned, the globe was easily one of the most dangerous, Col quickly became bedridden with fever. It was her request that had restored some of his vigor, and he poured his energy into teaching her proper spelling and grammar.

He watched as her vaguely incorrect letters, her plethora of spelling mistakes, and her odd grammar choices soon righted themselves. Myuri had always been smart—this was simply another demonstration that nothing could stand in her way when she put her mind to something.

That alone was enough to fill her foster brother with joy, but what touched him most was that she practiced using sentences from the vernacular translation of the scripture.

How many times had he imagined Myuri—rambunctious, tomboyish Myuri—murmuring God’s teachings to herself, copying God’s teachings onto paper? It was crucial for a young lady to have proper faith and the skills to write beautifully. He found himself, beyond a shadow of a doubt, enchanted by the way her cheeks lifted in her smile as she read aloud the gospel, sitting at the desk by the window, bathed in sunlight.

As one who had been caring for her since her birth, he could feel his eyes brimming with tears at the thought of finally being able to lead her down the correct path.

But the movement of his heart hid other things from him for only a very short period of time. Myuri quickly absorbed Col’s lessons; once she started responding with annoyance whenever he asked if she had any questions, the tide began to recede, and he started to see reality.

There was another question he should have been asking himself.

Why on earth would a girl like Myuri want to suddenly practice writing?

Myuri rested her elbow on the desk, stained her cheeks with ink, and fought desperately with the quill, a tool she was not used to holding. And the scripture, one her dearest elder brother had worked so hard on, from which she had been so eagerly learning, was soon discarded coolly in a corner of the room.

Instead, she fell asleep hugging a tattered, worn-out booklet held together by twine, and she no longer wrote prayers to God.

“Hey, Brother? I have some more spelling questions.”

It was not long ago that Col would not even dream of this happening—Myuri tugging on his sleeve, asking him for spelling advice. But the sole reason he felt a weight on his chest whenever he felt his arm move against his will was because of what she was writing.

“Pliers? When you have to pull out an arrowhead from your arm or something—how do you spell pliers? And can you tell me if I got blood splatter right?”

The words she asked about were a far cry from the proper words girls her age should be asking about. What in God’s good name was this girl writing with her renewed skills? When Col finally asked her, Myuri answered:

“The more I thought about it, the less I like how things ended at Raponell.”

As she gave her answer, her longsword—the proof of her knighthood that was engraved with the crest of the wolf—gleamed in the light beside her.

Things that normal folk like Col could never have imagined were the reasons she had taken up the quill.

“As they say, I’m forging my destiny.”

The day they disembarked at Rausbourne, they just so happened to come across Eve, who was busy discussing business.

Myuri took advantage of the opportunity to show Eve her used-up quills and order some extra paper. Col had no time to scold her for wasting money; Eve quickly wrote down her order on her wooden board, then shook on the exchange with the silver-haired girl.

It was only after their exchange had been settled that Eve learned why she had ordered quills and paper, and she smiled.

“It’s not often you find someone so determined to rewrite their fate. And so literally, at that.”

When Col watched the delighted smile cross Eve’s face, all he could do was sigh.

“You can offset the cost of the ink and paper by…Let’s see—how about some info on House Nordstone? Seems likely they’re going to be raising the price of wheat down there—if I know when they plan to do that, then I could make a pretty penny off it.”

Unlike Myuri, whose hands were small yet powerful, which meant it would be some time before she figured out the right way to hold a quill, Eve elegantly wielded the implement.

“But first you become the knight of your dreams, and now you write your own knight’s tale of your dreams. Good grief, you’re greedier than I am,” the woman said.

Myuri seemed to take it as a compliment. She grinned and puffed out her chest.

She had suddenly brought up wanting to relearn how to write after all was said and done, and whenever she had a spare moment since then, she had been busying herself with writing—and what she had been writing this whole time was every little detail on what happened with Nordstone.

That in and of itself, of course, was not especially strange. The world was chock-full of tales of adventure, and large cities had chronicles that detailed the land’s history, and great kings often detailed their tumultuous lives.

Everything Col and Myuri experienced in Raponell and beyond could stand proudly alongside those tales: a ghost ship filled with human bones; an alchemist sacrificing goats under the moonlight, praying for a bountiful wheat harvest; a fated tale of a boy and a girl left to the whims of their noble families, whose allegiances were still dictated by an ancient war.

A wandering bard could entertain the patrons at any tavern for a decade with those stories, but these stories belonged to Myuri, and she was determined to write them down. And what she was most concerned with was the ending.

It had all begun because of the crotchety old Lord Nordstone, who had been rumored to be dealing with the devil himself via these ships of the dead. He boasted a strong reputation, due to the fact he had saved his people from starvation by transforming a barren land into one rich with wheat. On the other hand, his often eccentric actions left him at terrible odds with the local clergy. And when events finally came to a head one fateful night, a certain priest decided the time had come to take down the nonbeliever, and he personally stood at the head of a mob.

The way the armed populace marched through the nighttime fields, torches held high, made them seem like an army of crusaders on their way to recapture the holy land. Their enemy, Nordstone, had no one on his side; and the very ones trying to take him down were the people he had dedicated his life to serving. The very people he had risked everything to keep well-fed wanted to tear him down with their own hands.

Col remembered how his chest had felt like it was being torn apart—he did not want the story to end in tragedy. The least he and Myuri could do was be at Lord Nordstone’s side, and so they rushed to him. But who appeared before them was not a despairing, wizened lord—no, it was a dauntless old knight, fully clad in armor, burning as he waited for his thankless assailants. And the moment he saw Myuri in her wolf form waiting beside Col, he believed her to be a well-trained hunting hound; he asked for her help and followed her. Before Col could stop either of them, they valiantly departed the forest.

Ultimately, the people’s sense of loyalty to the man who had helped their land prosper took precedence over the priest’s orders, and a tragedy between Lord Nordstone and his people was thankfully averted.

Myuri, however, came away from the incident carrying something else in her heart—the tension and excitement that only came with the prospect of heading into battle.

Though she had fought hasty, impromptu scraps in her wolf form before, this had been her first time when the lines of battle had been drawn and there was a clear enemy for her to fight as she stood under the banner of her cause. Myuri was a girl who grew up dreaming of adventure in the mountains of Nyohhira, where her weapon of choice was a tree branch. At long last, after a great many trials and tribulations, she had gotten her very own title of knighthood. Much like a puppy who spent an overly long time chewing on a cow bone, Myuri recounted her first experience of true battle for her brother over and over again—or perhaps it was more apt to say that she ruminated on it for ages when they were under the blankets.

Though at first the tale was full of excitement and dazzling moments, through repeated retellings, certain flaws inevitably began to show. And since this was Myuri—whose greed could astonish Eve of all people—she eventually came up with her own solution.

She wondered if her already wonderful experience could have been something greater. She wondered if it could have been even more wonderful.

What if events were supposed to have played out in some grander way, especially since this was her first true battle as a knight, something worthy of written record? Perhaps a certain someone could have marched into the enemy camp by her side, for example.

That crotchety old lord was certainly not a bad choice for battle companion. But the blade hanging from Myuri’s hip was decorated with a crest that only two people in the entire world were allowed to use.

So with a bitter look on her face, she said to him:

“I wish my first time had been with you, Brother.”

It went without saying that Col quickly slapped his hand over her mouth, and his eyes darted around in a panic.

He sternly warned her not to say things like that in front of others to avoid giving people the wrong idea, but she only stared up at him wide-eyed, and it wasn’t long before her tail began to wag, his hand still on her mouth. Nyohhira was a village of hot springs and mirth, and those wild dancing girls had filled this rambunctious girl’s head with so much unnecessary information. Even God’s authority grew faint in the steam of the baths, and so Myuri had grown to be a girl whose head was filled with all sorts of needless and superficial information about scandalous acts.

And she had four ears—she could easily hear oneiric footsteps even with her eyes closed.

Recalling the sounds of that night that carried the unique tension of impending battle, she wrote it down.

She wanted a gripping, ideal night of fervor, befitting her very first time standing on the battlefield as a knight.

“I’m honestly not sure how many times she’s rewritten it now,” Col said with a sigh.

Eve seemed to be in a genuinely good mood. “You know, I often think back on big deals I make. What I could have done, what I should’ve done, and all the things I would’ve done better if I had the chance.”

When Myuri heard that, she folded her arms over her chest and nodded. Of course Eve understood her.

“It isn’t as noble as you think. Myuri’s gone far beyond that, and now she’s coming up with far-fetched tales. Yesterday, it was just the two of us up against an army of ten thousand.” Col cast Myuri an admonishing glance, but she ignored him. “I scold her for wasting paper, but she refuses to listen. I have been biting my tongue, though, since it is good writing practice…”

Indeed, as she wrote more and more, that odd right-handed tilt had naturally fixed itself. And once she realized that large letters wasted space, she made a point to write more economically. That meant her messy, unreadable writing quickly became much neater.

Though she used a lot of frightening words in her writing, a knight who fought in battle did not often have time to pray to God. She would occasionally open the translation of the scripture and ask Col how one might pray in certain situations. He could not deny this could be one way to plant the seed of faith within her.

And he was simply surprised by himself—by how happy he was that all the things he had learned about faith could be useful to another.

Taking all that into consideration, he thought…perhaps, just maybe, despite all the negatives, Myuri’s newfound fascination was ultimately a net positive. Or so he told himself through gritted teeth.

“Either way, I’m just glad I found myself a new deal.”

In the eyes of Eve’s company, which had business dealings across the seas, no large order of paper—not even parchment—would bring them a considerable enough profit. Though Myuri might have been enjoying herself, it was not a cost Col and Myuri could ignore.

“She may put in an order behind my back, but I am still not paying.”

“Well then, you can just go directly to Hyland. It’s not like the money’s coming out of your own coin purse. Never met a noble that kindhearted, and definitely not one so soft for Myuri.”

What a dishonest merchant…Col stared hard at Eve, but Eve only smiled coolly in return.

“And you may not order anything without my permission anymore,” Col said to Myuri, who pointedly watched nearby ships unload cargo as though this conversation were no business of hers. In her tales, she was a noble knight who protected her priestly brother no matter what trouble befell him, fighting loyally by his side under his command. And in truth, that was exactly the kind of person she was.

Myuri stared with mouth agape at an apparatus that appeared to be a large crane raising more cargo. Col poked her in the head and adjusted his bags on his back, adding, “In any case, Mister Az has been a huge help.”

Az was the guard Eve had sent to accompany him and Myuri. Myuri had pestered him for sword lessons and fitness training, and he had become like a second teacher to her.

“He said he had fun, too. He usually looks all gruff, but he looked positively chipper today.”

Even though Az had only just finished one job, he had rushed straight to Eve to help with the next and was already gone. Though Col knew they could say hello next time they saw him at Eve’s manor, the abrupt way they had parted at the end of their journey made him a bit sad.

“I bet he ran off like that because he was a little too embarrassed for lingering good-byes.”

Though he acted like an iron man who rarely let his emotions show and concentrated on nothing but accomplishing his given task as efficiently as possible, this was a good reminder that it was unwise to judge things from appearances alone.

Or perhaps it was a testament to Myuri’s natural friendliness that she managed to befriend someone like Az.

“Either way, you should go home and rest. You’ve had quite the journey.”

Myuri then interjected, “Oh, right. We met someone named Kieman on the mainland.”

“Hmm?”

Eve’s eyes went wide; she had not expected to hear that name.

Myuri grinned. “He said he’s a way worse merchant than you are, Miss Eve.”

The word worse here came with a nuance of craftiness and the implication that he feared nothing.

In her business dealings that spanned both kingdom and mainland, Eve often butted heads with Kieman over territorial disputes. The moment she heard the name of her bitter rival drop from Myuri’s mouth, a smile crossed her face. It was like she had bitten into a particularly sharply seasoned piece of jerky.

“He can say whatever he likes. That boy has been obsessed with me for as long as I can remember.”

Myuri’s eyes went wide as she delighted in the childish back-and-forth of two bad merchants.

Once they arrived at the familiar manor, a young maidservant greeted them, a bright smile on her face.

Of course, this wasn’t a greeting that stemmed from faith, welcoming back a serious and honest budding priest. It was primarily because she was delighted to see Myuri, who indulged in quite literally everything the house staff gave her, like she was some sort of big dog.

The puppy they had taken in to mask Myuri’s spring shedding—courtesy of her wolf ears and tail—also came out to greet them and rushed right to Myuri’s feet.

Col straightened himself—none of this particularly bothered him. An elderly servant approached and took their things. He was one of the people who often prayed with Col in the early waking hours at the manor chapel.

“We missed you at morning mass, Sir Col.”

There were people besides God who kept a close eye on his actions.

That fact emboldened Col, and he promised the man that he would be at the next day’s mass.

The man then informed them that Hyland was absent, as she was attending a city council meeting. They sent a messenger to alert her of their return, so they might adjourn the meeting early, but until that happened, Col and Myuri were encouraged to freshen up and get some rest.

Though the ship journey home made for easy traveling, after many nights of sleeping on the hard floor and spending their days in the salty sea air, their exhaustion had built up. Not to mention all they had seen at Nordstone’s—Col wanted to eject all the anxieties, both physical and mental, by completely submerging himself in hot water at least once.

There was no way to indulge in such a thing, of course, so he washed his face with the warm water that had been brought to their room, scrubbed himself with a cloth he soaked in the water, and cleaned his feet last. It hardly felt like enough for someone who had grown used to the bountiful springs of Nyohhira, but it still made him feel as though he had been blessed with new life.

Myuri, however, got to sit and splash around in a washtub full of hot water, naked, as was her right as a child. Ever astonished by her behavior, yet rather envious of what she was allowed to do, Col began unpacking their things.

Their bags were mostly filled with letters and gifts for Hyland from the lord of Raponell. The rest were notes on the incident that Col had collected for the purpose of compiling a report, all the quills Myuri had ruined that he had felt bad about throwing away, and the abridged translation of the scripture that Myuri quickly lost interest in.

Even though the emotional impact of seeing Myuri copying passages from the scripture had been great enough to cloud his vision, he looked over to her as she scrubbed herself with a sponge and hummed a little tune to herself, and sighed. He wondered when the seed of faith would finally take root within her.

“You will unpack your own things, Myuri.”

“Hmm? Okay,” she replied breezily.

Col turned his gaze toward her bag, and it, too, was stuffed to the seams. It was filled with all of Myuri’s dreamed-up tales of adventure she had busied herself with, as well as mounds of dried fruits and candies from Raponell’s new lord, the young and proper Stephan.

Though she no longer held Col’s hand in town—she was a knight now, as she often reminded him—Myuri still had many childish habits, like her love for sweets. As his expression wound up somewhere between exasperated and relieved, the girl he worried about so often spoke up.

“Brother! Rinse out my hair!”

Her wolf ears, which had remained hidden throughout the entirety of the journey at sea due to the proximity of others, flicked off the water clinging to their fur. Her typically fluffy tail was covered in suds, too.

“Is our proud knight currently at rest?” Col asked. Despite himself, he found himself rolling up his sleeves. Though he wished she would find her independence sooner than later, he always ended up giving in to all of her requests; he told himself that was because caring for her was simply a long-term habit that was deeply ingrained at this point.

“Knighthood is the spirit of helping one another. Don’t you know that?” And Myuri, of course, showed no signs of changing at moments like this. “And actually, my hand hurts. I can’t wash my hair all that well.”

“Your hand hurts?”

Just as Col got to his knees behind her, the sudsy girl revealed the real reason behind her call for aid.

“My palm hurts when I clench my fist.”

As Myuri slowly curled her slender fingers, Col cupped some of the water from the washtub and poured it over her long hair.

“I keep telling you—you grip the quill too hard. You must learn to keep a lighter hold on it.”

“But you always complain about your hand hurting when you write a lot, Brother.”

Just like how Col had kept a close eye on Myuri ever since she was born, Myuri had kept a close eye on Col for as long as she could remember.

“But it’s weird. I don’t have any problem holding a sword, and it’s way heavier than the quill.”

“They do say that the pen is mightier than the sword.”

She was constantly scolded for swinging her sword around, so she glanced over her shoulder at him and pouted.

“You’ll get used to it after a time, I think. Your writing has become much nicer as of late.”

Myuri’s wolf ears, unlike her hair, were rather water-resistant.

They twitched, flicking droplets into Col’s face.

“Really? It is?!”

Delight bloomed on her face, and Col wiped his own with a sleeve as he donned a begrudging smile.

“At the very least, your letters don’t lift to the right anymore. I’ll massage your palm later, just as you did for me long ago.”

Back when he continued his studies as he worked in the bathhouse, she would often rub his palms when he spent too long with quill in hand. Myuri had been young enough that her tail was essentially the same size as the rest of her, and when she stepped on his hand, the pressure was just right to untangle all the knots.

“Should I step on your hand again?” she offered innocently, remembering the old days.

“You would break my bones if you tried that now.”

She immediately narrowed her eyes, and a growl rumbled in her throat.

As they talked, Col rinsed Myuri’s thick hair. Watching the dirt of travel fall from her silver strands reminded him of peeling a hard-boiled egg. As he thought about the future, and just how many times he would be caring for her like this in the days to come, he knew that all the things he found annoying would soon become fond memories.

He smiled to himself, hoping that day would come sooner than later. Myuri had been resting her chin in her palm but then suddenly spoke up.

“Oh yeah, you hired a bunch of people to write books for you a while back. That must’ve been tough work.”

She was talking about a time not long after they left Nyohhira, when life alone with Myuri was not as comfortable as it was now. They had been at odds with a city church, knowing they needed to spread the teachings of God to the masses to keep the church in check. So Col had gathered artisans who specialized in transcription, and made copies of one part of the vernacular translation of the scripture.

“Transcription…the copying of writing, is considered a part of a monk’s strict training,” he explained.

Myuri still had the spirit of a boy in her heart; her tail reacted to the word training, but she uncomfortably squeezed her hand open and closed again before nodding in understanding.

“So that’s the reason why there were chains on the books in the library.”

“It is good you understand the hardships of others.”

Myuri briefly puffed out her cheeks in response to what she thought sounded like a lecture.

“Come now. Hold down your ears—I’m rinsing your head.”

She hated when water got in her wolf ears, so she quickly brought her hands up to cover the triangular tufts. Col poured water over her two, three times and reviewed his work.

“There. All finished.”

“Dry my hair.”

“………”

Myuri opened and clenched her little hand again, as though emphasizing her point.

With a sigh, Col began to wring out her hair, and the smug girl grinned.

“Oh, right! Brother!”

“Do your tail yourself. It always tickles you when I do it, and you get water everywhere.”

“No! I’m talking about the old man!”

“Lord Nordstone? There, your hair is done. Dry the rest on your own.”

Now that he was finished wringing out most of the water from her hair, Col took a white linen cloth and placed it on Myuri’s head. She must have thought he would dry it all for her—she looked back at him and frowned, then reluctantly began to scrub the cloth through her hair.

But the real reason Col placed the cloth on her head was to block her view. Whenever Nordstone came up, he could not help but think of the globe. The unbidden welling of anxiety never failed to come as well.

He had kept everything about the globe secret from even Myuri.

“Miss Ilenia said she’ll be going on the same boat as him. I wanna see her,” Myuri said. It did not seem as though she noticed he was hiding something.

Ilenia, a sheep spirit, was more invested in pursuing the rumors of the new continent than even Myuri; she wanted to create a land for nonhumans like them. After the incident, Nordstone took advantage of his exile and left on a journey by ship. And because he was somewhat related to the alchemist who believed in the existence of the new continent, Ilenia had left before them and hopped on the same ship so that she may learn more from him.

Ilenia could easily be considered Myuri’s first friend since leaving Nyohhira, and she was probably feeling as though she had been left behind.

“Miss Sharon might know where they went. I believe she joined them because her home was in the same direction, yes?”

“Hmm, I dunno. I feel like she said she was busy and flew off on her own.”

Sharon managed an orphanage in Rausbourne and was also a bird spirit, which meant she enjoyed a much greater freedom of movement than they did. But Sharon had been acquaintances with Ilenia for much longer, so it was very likely that she already knew where Ilenia was going.

“You ask for me, Brother,” Myuri said, pouting, her lips red from the heat of the water.

Whenever Sharon and Myuri shared company, they began snapping at each other, calling each other “Chicken” and “Dog.” From a certain perspective, they were oddly in tune, and Col had thought they got along rather well on some level.

“She has been a big help to us as of late. It wouldn’t be the worst idea to give your thanks, and—yes. Why not offer to help at their orphanage while you are there?”

“Hey!”

Myuri sounded genuinely upset by that suggestion, and the puppy yelped in surprise.

“Knighthood is the spirit of service.”

“Ugh…” She groaned, and the puppy stared at her. She kicked out her folded, slender legs from the washtub and drew up her thin, bony shoulders—a sign she was still growing—as she stared at the ceiling. “I’m a knight now, but nothing I get to do is awesome!”

“A true knight stands atop the slow accumulation of small good deeds.”

Myuri pouted at the lecture, immediately shook out her tail as she stood, and sprayed Col with water.

After eating wheat bread sweetened with honey the maids brought to tide them over until dinner, Myuri promptly fell asleep.

As energetic as she had seemed, not once did she insist she was not tired by their journey, and she dozed off in an instant. It wasn’t as though she had suddenly given out after running around Rausbourne in her excitement of their return, but more that she was genuinely getting some rest, and that pleased Col.

But even though he had been so desperately looking forward to sleeping in their soft beds upon their return to the manor, Col found himself oddly unable to find slumber, likely due to how much he had slept on the ship.

The sun was still high in the sky, and since Hyland was occupied by the council meeting, it was unlikely she would be returning anytime soon. He had already finished writing his report to her on the ship.

He then realized that, despite what he said to Myuri, she would be delighted if he went to Sharon to ask about Ilenia’s whereabouts. And he, too, wanted to hear, from someone besides Myuri, how Nordstone had been faring since the incident. He wanted to confirm his suspicions of whether the old lord had left while Col was bedridden expressly to avoid pointed questions about that globe in his house.

Myuri clung to her blankets and snored loudly. Col lightly patted her head, then entertained the clingy puppy for a few moments before leaving a message for Myuri on the wax board telling her that he was off to see Sharon. As he left the manor, one of the servants regarded him dubiously when he said he was going for a walk, but he received a respectful send-off nonetheless.

The private orphanage Sharon managed sat in a particularly mazelike district. Since Col had always relied on Myuri’s navigation when visiting, he was a bit worried about getting there on his own. But as he neared the orphanage, the neighbors recognized him and politely gave him directions.

When he spotted the familiar door, one with a rustic iron peephole, he relaxed.

There were several pigeons perched on the roof, looking down at him. All the birds in Rausbourne fell under the command of Sharon, an eagle spirit. It was likely they had already reported his slow arrival, and she perhaps already knew that Myuri had even captured a seabird aboard the ship.

Before he could knock, the peephole slid open.

“Where’s your dog?”

For her to ask about Myuri before even saying hello was surely a sign they were close, Col thought to himself.

“Myuri is napping at the manor. We arrived back in the city not too long ago, so I think she’s tired.”

“You don’t look it, though.” Sharon huffed quietly, but briefly closed the peephole before opening the door proper. “Clark’s been wanting to see you, but the timing’s always bad.”

The inside of the building smelled like milk; there were a lot of young children at the orphanage. It reminded Col of when Myuri was little.

It was quiet. The children were either out working at this time of day or, like Myuri, napping.

“Is the construction of the monastery keeping him busy?”

The reason he and Myuri met Sharon in the first place was because of a big to-do surrounding the tax-collecting association that Sharon led and a plot concocted by merchants from distant lands. The one who had stood between them and the Church, and continually stood by Sharon’s side to support her, was a boy a bit younger than Col himself—Assistant Priest Clark.

After many twists and turns, Clark ended up helping Sharon and her cohort build a new monastery and was the one eventually appointed to be head abbot. He did not let it get to his head, however, and was working himself to the bone to get the monastery up and running.

“He’s cleaning up the ruins we’re using for the monastery. He’s put on some muscle recently.”

“We should have some free time, too, so we’d be happy to help.”

A look of surprise crossed Sharon’s face, and she smiled dryly.

“You’ll be just as much help as Clark was not long ago.”

Even Myuri had said that Col and Clark were very similar. It took only a glance to confirm that neither was very well acquainted with heavy lifting.

“If there’s anything you can do to help, it’s use your name to do something about our funding problem,” Sharon mused.

“Your funding? But I thought that was…”

They had permits from the cathedra, backing from Hyland, and funding from Eve. Col had assumed this would be more than enough, but Sharon sighed.

“Doesn’t matter how much funding we have; it will never be enough,” she said, her tone practically admonishing him for his ignorance. “Sure, Hyland’s given us a former noble’s residence, but we can’t use it without a lot of work. My head hurts just thinking about how we’re going to raise money for repairs alone. And even if we do manage to fix up the place, you think we can run a monastery with only copies of the scripture? I used to be a tax collector, remember. I’ve seen plenty of failing businesses, and all I can see here is bad news.”

There was anger in her chilly gaze, and Col found himself shrinking. He recalled when Myuri had been helping them, running around to purchase furniture—he had been shocked by how long the shopping list was. He could only begin to imagine how much it would cost to transform what were essentially ruins into a livable space, and then to turn that space into a stable business.

With that thought in mind, and upon closer inspection, he noticed faint bags under Sharon’s eyes and ink stains on her fingers.

He could easily picture it—once the children had been sent to sleep, she sat under the weak light of a tallow candle, brows deeply furrowed, as she racked her brain over the management of the monastery and annexed orphanage. It made perfect sense that she was genuinely irritated to have been pulled away from all that when they needed her help to resolve the Nordstone problem.

Sharon was undoubtedly a loyal and reliable companion to spare time to help with an incident that had little to do with her—and right when her hands were already quite full with big responsibilities.

“Holy relics attract pilgrims anyway, so I have hope for the monastery side of business,” she said, glancing at Col. She looked at him not as an acquaintance but as a shepherd checking how the wool was coming in on her sheep—or perhaps this was like the time when Myuri begged him for a legendary sword that incorporated the bones of a saint.

Even if calling himself a “relic” was a bit of a stretch, Col was known as the Twilight Cardinal now and would surely attract many visitors. Though he had decided to offer a handwritten copy of the scripture to the new establishment, he now wished he had settled on something more relic-like. Just as he was starting to genuinely consider offering a piece of his own clothing—after deciding the usual spectacles of a saint’s tooth or bone might be a tad difficult for him to give—Sharon shrugged.

“Well, that dog always gets real annoying whenever I decide to put you to use.”

“That’s not—”

—True, is what he wanted to say, but could not.

“I’ll get yelled at if I go to Hyland any more to discuss funding. Seriously—this gives me a headache.”

That surprised Col.

“I’m sure Heir Hyland would be delighted to speak further with you.”

A displeased smile crossed Sharon’s face. “I know. She’s real earnest when we chat. And I hate it.” She sighed, folding her arms over her chest. “She’s a nice noble. In a world full of people who can’t think past the tips of their own noses, you’d think a landowning noble as honest as her would be running an affluent domain, wouldn’t you?”

It was hard for Col to imagine, of course: Hyland levying heavy taxes on her people.

What would happen if Sharon went to Hyland asking about financing the monastery?

“She would do anything to give you money, wouldn’t she?”

Sharon gave an exaggerated shrug.

“I could ask the cathedra for extra money, but it’s probably safer not to. Considering how the kingdom and the Church are fighting now. At this point, I only have so many options.”

And Col knew right away what sort of options those were.

“I know Miss Eve would be happy to talk with you, too.”

Eve was also providing the monastery with funding.

But the deep wrinkles between Sharon’s brows did not disappear.

“True, she would. But you know she’s like a crow scavenging on corpses, right? When I think about how much interest she’ll ask for on whatever amount we borrow, I can feel another headache coming.”

Perhaps the only reason Col wanted to insist that Eve was not that awful of a person was because Eve had spoiled him silly as a child.

“Well, if this monastery doesn’t get up and running, I could always threaten her to write off all the money she gave us as losses. If it comes down to it, I can just take a look at her trade record. I bet I could find a wrongdoing or two and use that to blackmail her.”

Sharon wasn’t a former tax collector for nothing.

“Good grief. God sure always has a plan, doesn’t He? Right. Anyway. You here for a chat?” Sharon changed topics, her eyes weary.

Col found himself unconsciously straightening himself. “Ah, well…”

What he had come here to ask about felt beyond silly after hearing her gripe about problems as grounded as finance, but it would be strange if he said nothing after coming all this way.

“I just…was wondering what Lord Nordstone and Ilenia were up to…”

Sharon, who drew up cold well water as he spoke, smiled wryly.

“You’re too soft on that dog.”

He could not argue that.

“But she really likes Ilenia, huh. Maybe lamb smells tasty.”

Now that he thought about it, Myuri always gave Ilenia a tight hug whenever they reunited.

“Ilenia and that old man said they’d be going to the royal court, which is a little north of here. They’re going to raise some money for the voyage to the new continent.”

“Ilenia went, too?”

Sharon shrugged, vexed. The eagle spirit did not seem to share the same passion for creating a home for other nonhumans on the new continent as Ilenia had. It seemed as though she was settled on living life here, among people, for the orphanage with Clark.

“A continent on the other side of the sea? They sure are bold for wanting to send a ship out for such a stupid idea. I genuinely can’t believe it.”

Hearing this from the one who had all the birds around Rausbourne under her control made it sound quite clear that even the highest-flying birds had never seen this continent at the edge of the sea.

“I heard Ilenia reached out to some of the birds of passage, too.”

“And Myuri asked a large whale, one as big as an island the same.”

The chuckle rolling in Sharon’s throat quickly turned into a sigh.

“Then there’s that whole business with the alchemist, the one Nordstone knew. Personally? The dog aside, I wish Ilenia would wake up already and realize she’s getting involved with bad news.”

Nordstone, rumored to have been dealing with the devil via ghost ships, had a friend. And that person was the alchemist, the one who had not only transformed barren land into great fields of wheat but who had also been investigating the rumored existence of a new continent. Sharon spoke of this alchemist like a witch who was giving her friends terrible nightmares, but Col, who was indeed being plagued by awful dreams, knew the feeling well.

“Have you heard anything new from either Lord Nordstone or Vadan and his crew?”

For a moment, Col believed Sharon narrowed her eyes at him because it seemed as though he had seen through one of her secrets.

“I’m not an owl. I don’t sit at people’s windowsills to get info on my enemies.”

Col recoiled—that was not what he meant—and Sharon scoffed.

“I never pegged you as the type to get caught up in this new-continent business, but…all I’ve heard is that the alchemist ordered Vadan and his crew to scavenge for documents in the desert countries so that she might find information on the new continent.”

Vadan was also a nonhuman who controlled the mischief of mice commonly found on ships, and he had been working with Nordstone under the alchemist’s orders. Not only was he a mouse spirit, but he was also an accomplished pilot in his own right.

“Desert countries?”

Sharon shrugged. “A lot of what the alchemist learned was knowledge lost when the ancient empire collapsed, including wheat-growing techniques. It’s been a long time since all that knowledge was last used in the lands under the Church’s influence.”

According to legend, the big island that was now home to the Winfiel Kingdom was originally invaded and conquered by soldiers from the ancient empire and the Church. But as time passed, the empire collapsed, and its existence remained only on parchment now.

In the days when the empire reigned supreme, the Church was not the extensive organization it was in the present day. The world was still full of pagan myth back then. The Church’s reach only grew after the empire collapsed; they took the opportunity to smother all customs and cultures that did not align with their teachings by branding them as heathenry and heresy. A visible example was how wolves were no longer used in noble crests, something Myuri had been furious about.

Along the way, a great many other things had undoubtedly been lost as well.

If the story of the new continent originated in the time of the empire, then it made perfect sense that traces of it would likely be found in the desert lands. Not only that, but it was likely information on it would remain in the desert regions especially if it was considered heretical by the Church. And in short, Col could easily surmise that the globe modeled after their world had been created with knowledge gleaned from the desert.

“Didn’t Vadan and his crew often collect copied books from the desert kingdoms?”

“Did they? They can reach the south easily enough by ship, and they are good at stealing.”

These nonhumans’ true forms were often animals on a scale beyond what humans could conceive, but Vadan and his crew could take on their small mice forms and easily slip through the cracks in the walls to get into places. And mice were particularly adept at chewing holes in obstacles, so there were very few people who were better at theft than them.

But the point Col wanted to make in that moment was entirely different.

“That may be true, but what I mean to say is that finding where valuable tomes are kept would not be very easy.”

“Hmm…? Ah, right, I didn’t think they were all that educated. But that alchemist was some kind of cat, wasn’t she? I heard cats originally come from the desert, or something like that. Maybe she always knew that stuff to begin with. Perhaps she simply lived through the era when the ancient empire was still alive.”

“Oh, yes. That’s very possible…”

Col remembered that nonhumans lived on a time scale far beyond what humans like himself could comprehend. Vadan and his crew would have needed a guide to find books in the desert, and a spirit from the desert would be more than qualified. Even better if they had been alive when the books were written and read.

“But besides that, I haven’t heard anything particularly new. Ilenia had been listening intently when she heard the story, but she didn’t look particularly happy about it.”

Nordstone also did not seem entirely sure why the alchemist had been so convinced about the existence of the new continent. Or perhaps the alchemist was simply positive that the world was round and set out to sea while considering the discovery of a new continent to be a fun bonus.

“So it did not seem that Lord Nordstone had any additional information on the new continent.”

Even if the cat alchemist was convinced of the new continent’s existence for one reason or another, Nordstone did not have the means to confirm. Perhaps it was apt to assume that he simply trusted the alchemist.

“Or maybe he was hiding something and didn’t trust Ilenia. She’s obsessed with that continent. That Nordstone is by far the most eccentric human I have ever met. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was hiding something unthinkable behind that blank face of his.”

Considering the globe with the world map drawn on it, Col could only respond with a tense smile of agreement.

Sharon leaned against the wall, crossing her arms as she said, “It’s not like I care if you end up fish food at the edge of the sea. But if you start sticking your nose in weird stuff, Hyland’s going to get upset.”

Even Col knew the reason Sharon said this was not because she was particularly attached to Hyland. The orphanage, where all the orphans under her care would eventually live, was a part of the monastery, which had Hyland’s backing. If Hyland were to lose her position, the monastery’s foundations would grow shaky.

“Of course,” he replied earnestly. But the expression on Sharon’s face reminded him of his own when Myuri reacted to him after he scolded her for eating too much.

“But I appreciate the offer to help clean up the ruins. I’m sure Clark will have an easier time of it with more hands on deck.”

“Yes, of course.”

“But,” she continued, her smile lopsided, “does that dog know about this?”

Col was about to take a drink from an unglazed cup, but he stopped.

A servant of God would not lie.

“She is a knight, after all,” he said.

It is the duty of a knight to help those in need…or so is the way it is meant to be.

Sharon shrugged and summoned a pigeon to help Col find his way home.

Not even Autumn, avatar of a whale who swam the seas, or Ilenia, who spoke with migratory birds, had any definitive information on the new continent. And it seemed apt to believe Nordstone was no different.

Myuri had always loved tales of adventure—an undiscovered continent would be right at home in her stories.

Col began to seriously consider the idea not simply because he sympathized with the desire to found a country for nonhumans. He wanted this for Myuri, who had the blood of wolves running in her veins and who straddled the line between the human world and the deep forests, and he also wanted to support Ilenia’s dreams.

Col himself, however, was both human and a devout lamb of God.

A few years had passed since the Church first came into conflict with forces mostly centered around the Kingdom of Winfiel. Forgoing outright war, neither side had been able to decisively gather a winning hand, and so things had come to a stalemate. Col had a feeling that the existence of a new continent may very well be what was needed to end the current deadlock.

So Col had gone to see Nordstone not only because Hyland had ordered him to, but also because he had heard rumors that Nordstone had also been investigating the new continent.

His and Myuri’s latest trip had been a fruitful endeavor. But nothing Col found had been decisive—instead, he felt as though what he stumbled upon only deepened the world’s mysteries. And then Sharon mentioned ancient knowledge buried in the desert.

He sighed, now knowing there was more that would only cause Myuri excitement. He wanted to turn to the heavens, to where God supposedly sat, and ask just how many secrets this world held.

As he walked, carefully rolling these thoughts around in his head, he eventually found himself before a familiar manor.

“Thank you for your guidance.” Col gave his thanks, stroking the throat of the pigeon that perched atop the manor walls with the back of his finger. The pigeon puffed out its chest, cooed as though insisting it did not need any thanks, and finally flew off. As he watched the creature soar away, he spotted something above him—it was not God, but someone peeking out from the manor window.

“Are you done napping?”

Myuri scrunched up her drowsy eyes and retreated into the room. It seemed she was not happy with the combination of discovering that Col was gone when she awoke and that he had gone to see Sharon.

As he stepped into their room with a tense smile, she came to give him a tight hug. Where had her noble knight’s bearing gone?

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said.

Or perhaps she had had a bad dream, the kind she typically had during her naps. As he drew his hand over her head, damp from sweat, her drooping tail slowly began to swish back and forth.

He gave her a small smile—she was still very much a spoiled child—and drowsiness suddenly overcame him as well. He considered taking a short nap because he knew it would be bad form of him to be constantly yawning during their dinner with Hyland.

As he brought the sleepy Myuri back to bed in his arms, she stomped down hard on the floor and refused to move.

“Myuri.”

Myuri, her face buried in his chest, chuckled, and her tail wagged. The puppy sensed the playfulness of the situation and chased after her tail, rolling on the floor.

The sadness Col felt at the prospect of her future independence lasted for only a moment. He, in fact, wished she would stop clinging to him as soon as possible.

“That’s enough. Your actions will only cause your title of knight to—”

—Weep, though the word did not leave his mouth. Myuri’s fluffy wolf ears suddenly stood on end.

Not a moment later, the sound of a horse and carriage came through the window; he twisted around to pull himself closer and see out it. There, he saw a familiar carriage entering the manor.

“More interruptions…,” Myuri muttered—it seemed her wolf ears could easily tell who exactly was in the carriage. “Brother…let’s stay in bed until dinner…”

Her whiny tone only brought recollections of Sharon at their most recent meeting.

“Miss Sharon had bags under her eyes from working on the construction of the orphanage.”

“……”

Myuri silently stood her ground.

“Come now. It’s time to get dressed.”

“……”

“…I’ll braid your hair.”

Though Col knew he was not playing his part well because he constantly compromised in situations like these, he always found himself feeling defeated whenever he saw just how delighted Myuri was as he gathered her hair into two braids—her favorite way to wear it.

Once the rambunctious girl was ready, the maid came to announce Hyland’s return.

What caught Col by surprise was that they had been summoned to the office, of all places.

“Oh yeah,” Myuri said as she waved her braids about like her tail. “The carriage did sound heavy when it came in.”

Despite how soft they looked, her wolf ears always picked up on the most important things.

“Do you mean someone else was in there along with Heir Hyland?”

“I thought she brought back lots of presents.”

“If that was all, she wouldn’t ask us to come to her office.”

She would have asked them to come to the dining hall instead.

“Something may have happened while we were away. A problem with the Church, perhaps.”

Col tried to gather himself—now was not the time to give in to the exhaustion of their journey—when Myuri pushed something onto him.

“Here, Brother. For you.”

She had pressed the scripture to his chest; not understanding why, he took it, and she slid her sword onto her belt. In contrast to her high spirits, Col dropped his shoulders.

“Are you still dreaming?”

“What? Hey! Stop!”

Col lifted the sword from her belt and placed it on the desk along with the scripture.

“You shouldn’t carry around your sword if there’s no real need.” Before Myuri could argue back, Col stopped her and said, “You have a perfectly sharp weapon besides your sword, and that is your intellect.”

Myuri was indeed much stronger than Col against opponents who were hiding ulterior motives.

“I believe an upstanding knight should be perfectly capable of handling most situations with intellect and calm judgment.”

Myuri stared blankly at Col. And perhaps that image crossed her mind; her tail began to swish back and forth, and her eyes gleamed.

“I can do that!”

“I know you can.”

Though Col found himself losing arguments to the unruly girl more often nowadays, he could not let go of her reins quite yet. Her new standing as knight turned out to be a good excuse to keep teaching her for a little while longer.

And so he fell in step behind her, her braids swishing back and forth like her tail as they made their way toward the office. As he watched her walk with wide, elated steps, he found himself smiling in relief. For a long time, he only felt nervous when he watched her go on ahead, but at some point, he had begun to find the sight reassuring.

“Brother?”

As the thoughts rolled in his head, Myuri turned to speak to him.

“I feel like I really should’ve brought my sword after all.”

Her voice was low; two guards stood in front of the office. One was a familiar face, a knight who served Hyland directly and had instructed Myuri in her sword training. What caught Col’s interest was the other guard, whose physique suggested a lifetime of training; he scanned the area with animosity in his eyes. And that meant beyond the door was someone this person was tasked with protecting.

Even as they approached, this new guard did not bother hiding how he glared directly at them; Col was worried Myuri might start growling at the man.

“Heir Hyland is expecting you.”

Myuri’s sword instructor invited them closer; Col pretended he did not notice the sharp gaze coming from the other guard and nodded slowly.

The knight knocked on the door and announced, “Sir Col has arrived.”

“Send him in,” came the response from inside, and the door swung open almost instantly.

“I’m sorry to bother you while you were resting,” Hyland said.

“It’s all right.” Col replied with a dip of his head.

As he did so, the visitor in the office stood.

What sort of noble was this going to be?

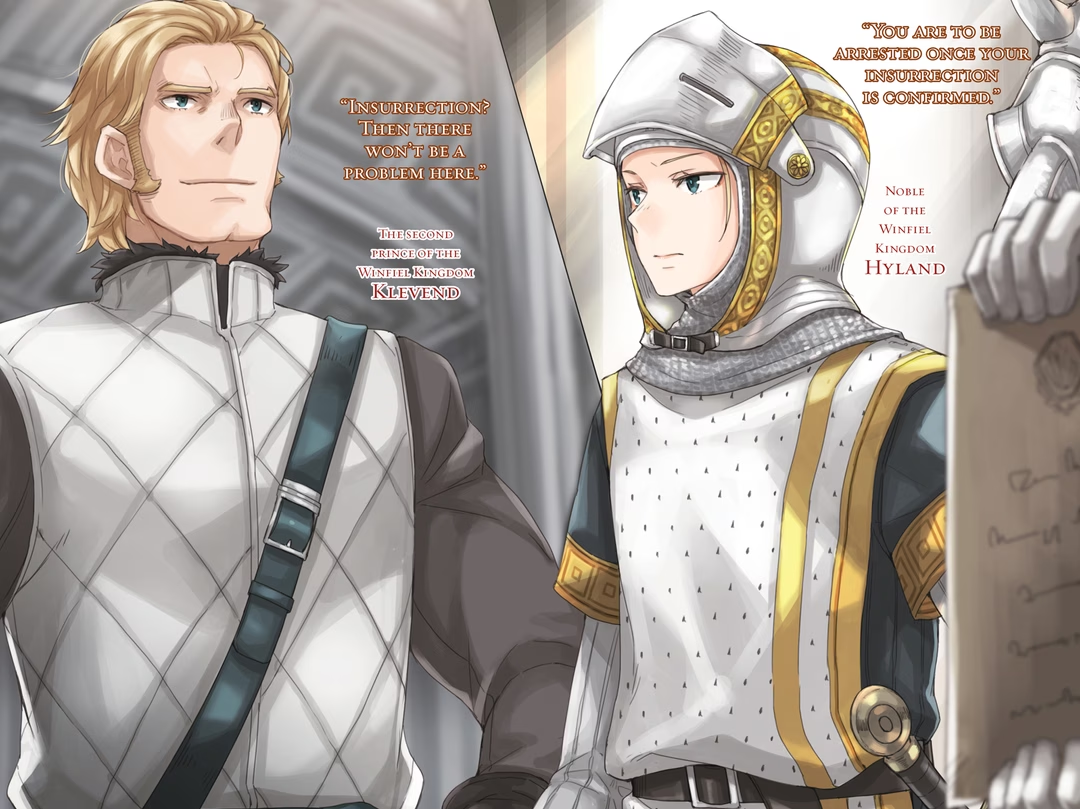

Col strained himself to lift his head, only to suddenly feel the wind knocked out of him. Before him was not an arrogant noble, nor was it a greedy-looking merchant.

It was only an initial impression, but he was sure this visitor was a member of the clergy. But he seemed to still be in training and was perhaps a bit older than Myuri. He was a marked contrast from Rhodes, the knight-in-training they had gotten to know when the pope’s personal Knights of Saint Kruza came to the city. His soft, bright hair and jewellike eyes made him the perfect picture of a refined boy. He, quite frankly, did not match the imposing soldier standing guard outside.

“You must be the Twilight Cardinal.”

Oblivious to Col’s bewilderment, the standing boy spoke with a kind smile.

Col, however, could tell right away that it was not a typical boyish smile but the expression of someone who was familiar with and relaxed in situations like these. If Col ended up overawed by the sheer atmosphere of this encounter, the wolf at his side would surely tease him afterward.

He somehow managed to meet the other boy’s eyes and held them as they exchanged a handshake.

“My name is Tote Col. The people call me the Twilight Cardinal, but it’s a bit excessive.”

The boy smiled and said, “My name is Canaan Jochaiem. Please call me Canaan.”

Col idly considered how classically elegant his family name was, but those thoughts were cut short by his shock at what Canaan said next.

“I am an apprentice of the Holy See’s archives.”

Just as Col was about to jerk his hand away, as if he had touched a hot surface by accident, a mischievous glint shone in Canaan’s eyes.

“I am not your enemy. I believe most within the Church rather consider me a traitor.”

Col could tell he had not been able to completely hide his shock due to a displeased sigh from Myuri. But it seemed Hyland grimaced not because of his lack of grit.

“It’s okay. I was shocked when I first received word, too.”

Canaan mentioned the Holy See—the pope’s seat of power. Even if he was just an apprentice, he still held an important position among the clergy. Considering how the kingdom and the Church were currently at odds, the fact that Canaan was here could not be made public.

That also explained the need for a steely guard in a meeting like this.

“I’m sure you understand things would get sticky if word got out that he was here in the kingdom. I apologize for springing this on you the moment you’ve returned from your travels, but I knew I had to bring you two together before something slipped.”

This was important enough that when Hyland heard of their return, she decided to prioritize this meeting over dinner and listening to Myuri’s adventures.

Canaan added, “I have come to the kingdom to mediate the conflict between the kingdom and the Church.”

His blue eyes softened, and he smiled.

The Church was an organization where the pope—the individual closest to God—sat at the top. The churches scattered across the world were bound together by a strict hierarchy, and they all submitted to the pope’s authority. Several cardinals acted as the pope’s assistants, and they were the ones who made decisions over the entire Church body from within the Holy See’s administrative body, the Curia.

The Curia was, in essence, the heart of the Church. It was an institution that embodied the world’s faith. For Canaan, an individual who worked in such a place, to be in the kingdom was essentially an act of treason, just as the boy himself said.

“To put it frankly, the Church is not a monolith.” Canaan described his position briefly.

Hyland continued for him, delving into the boy’s family name.

“The Jochaiem family is connected to the Church Father, who made contributions to the formation of the Church during the time of the ancient empire. Their pedigree is impeccable and includes many popes, though none hail specifically from the Jochaiem family itself. God himself vouches for his identity.”

The pope, whom all the kings who ruled the world would kneel before, could be counted as one of the boy’s relatives. As Col tried to digest the idea, which felt completely removed from reality, Canaan smiled softly in response to Hyland’s explanation.

“We are like the smaller branches that always come attached to a much larger tree. All my family is really good for in times like these is gaining the trust of feudal lords.”

Due to the way he presented himself, what Canaan said did not come across as self-effacement or humility. There was a calm about him—a coolness, almost—that accepted reality without reservation, taking the situation and, instead of exaggerating or downplaying it, simply seeing it for what it was.

And that did not seem to be an overestimation at all, either.

“But smaller branches have their merits. If my betrayal were to be revealed, it could easily be brushed off as the independent decision of a foolish young boy who chose the wrong path out of ignorance.”

Canaan understood himself as a sort of disposable pawn. Perhaps there was little sense of tragedy about that due to the Church’s many accounts of missionaries heading into pagan lands without any regard for their own lives.

“The proposal comes from a genuine member of the Jochaiem family. If there is a way to resolve the conflict between the kingdom and the Church, then we will need to consider it seriously. Especially if what he says is true.”

“What did he say?”

Canaan nodded as he responded. “There are those within the Church who are losing their patience in the face of this stalemate. More and more people are hoping for war. If we simply stand by and allow things to run their course, I believe war will break out by the next harvest.”

“Oh no…”

Col knew that if the conflict escalated, the only thing that awaited them at the end of this path was open warfare. He wanted to avoid this if at all possible, which was why he had considered investigating the new continent, even though it sounded like something Myuri might have dreamed up.

It seemed they did not have as much time as he thought.

“Isn’t that weird, though?”

Everyone present turned to look at Myuri. She did not spare Col and his shock one glance—despite her casual tone, her eyes were sharp and alert, boring into Canaan, who smiled in an almost emotionless manner.

“You said mediate, right?” she asked.

Canaan nodded.

“Face is super important when it comes to arguments,” she continued. “No one would have any problems if everyone could just agree to stop fighting.”

Col could not scold her for interjecting into the conversation because she was much more adept in the art of debate than he ever was. That, and he also remembered what Eve had said to him.

That greedy merchant had said the dispute between the kingdom and the Church was not over lofty ideals like the righteous of faith, but something easier to understand, something more down-to-earth.

“Tithes, right? They were originally used to raise money in the war against the pagans, but the Church keeps collecting them even though the war is over. And they’re using that money now as reward money for all the people who contributed to the war, right? But since the Church thinks of itself as a major player in the fight, they believe that getting rid of the tax would mean getting rid of their own reward. And that’s why they’re not listening. Isn’t that the gist of it?”

Even though Myuri was not typically very eloquent, and often spoke with disdain about the Church, considering her heritage as a merchant and a wolf’s daughter, it was times like these that she was most composed.

And her accurate summary of what Eve had proclaimed to be the bones of the matter had seemingly won Canaan over.

“I was wondering why such a lovely young lady was present at this meeting,” Canaan said, his expression revealing his surprise.

Col decided to ignore that Hyland seemed even prouder by the implied compliment than Myuri herself.

“But yes, you are correct,” Canaan continued. “It is a problem of…Yes. It is a problem of face,” he said, his tone astonished.

The kingdom insisted that the tithes should be abolished since the war was over, yet the Church insisted that the money was being used as remuneration for the war—not only did both arguments have a certain degree of logic to them, but resolving the conflict required making sure that neither side lost face in the process. That was why Col had turned his attention away from the tithes, where one side would lose and one side would gain in their abolishment, to the new continent, which would only bring more riches to the table.

He believed that rather than fighting over limited tax revenue, everyone would benefit if they linked arms under the banner of cooperation once again and worked together to acquire new land.

Was it possible that Canaan, too, had set his sights on the new continent?

But just as that thought crossed his mind, Myuri spoke up.

“Problems of face are complicated. And yet here you are, saying you can get everyone to make up peacefully. I just have to know what kind of evil plot you’ve cooked up.”

She specifically used the words evil plot because what she really wanted was to check whether Canaan was planning on taking advantage of her foolish little lamb.

It was wording that would normally be intolerable for an envoy of peace who had exposed himself to danger by venturing into enemy territory, but Canaan responded by letting his fake smile drop. A boyish look, one more befitting his age, quickly took its place.

“Journeys bring us to people we could never have dreamed of. I am truly thankful to God.” He beamed. “We have a plan in mind, of course. Naturally, we have no intentions of unilaterally compromising and capitulating to the kingdom’s demands. For the sake of the Church’s authority, you see.”

Myuri had sniffed out the makings of a plot; her eyes gleamed brighter, and she canted her head to the side. It was as though she had found prey deep in the forest and was listening to it walk with both sets of ears.

“However, the victory we have in mind does not align with the intentions of the mainstream factions, which includes the pope. It is in this regard that I believe our faction and the kingdom share a common objective.”

Myuri furrowed her brow and turned to look at Col, as though she had questions for him. It was perhaps because she did not know the Church well.

Col, however, was not thinking of Myuri. He was shocked.

“I assume the pope does not agree with this?”

If that were true, then Canaan’s self-evaluation as a traitor would not be an exaggeration at all.

“All the powerful cardinals are ready to stand firm and oppose the kingdom until the bitter end. Additionally, the pope, with his broad insight and magnanimous heart, will hear what they have to say and pass fair judgment in kind.”

Even Col, the one subject to Myuri’s frequent teasing for being gullible, could not take Canaan’s words at face value. Cardinals ranked just below the pope, but whoever sat in the position of pope was always someone who had been chosen from among the cardinals, so their relationship was not as simple as a bond of ruler and vassal. They were, at times, his vassals, but at other times his equals. If what Col had heard was to be believed, there were even times the cardinals were the pope’s puppet masters.

In essence, there were bound together by a common destiny, and it seemed the current pope was somewhat weak compared to the current group of cardinals.

“What is your definition of victory, then?” Col asked.

Canaan narrowed his eyes slightly and said, “Purging the Church.”

“…Purging?”

“Yes. Think of us as inquisitors.” It seemed as though Canaan was expecting Myuri to frown and for Col to catch his breath. He flicked the sleeves on his robes and adjusted himself in his seat. “But what we are cracking down on are not contradictory ideas about God, but the Church’s discipline. Especially those giving in to the temptation of gold.”

Canaan had introduced himself as one of the archive workers of the Curia. There, they held documents detailing all of the Church’s activities, and Col had even heard that people had gotten injured before due to how large and mazelike its halls were.

Which meant a certain type of document was most certainly mixed in among all the other types of literature.

“Do you manage the ledgers, then?”

The Church, spread over such a wide area, boasted a massive income, and that was not just limited to donations.

At the center of the whirlpool of money was the heart of the Church—the Curia.

“The accounting office is a part of the archive division. They record the flow of funds throughout the entirety of the Church and serve God by directing that flow toward righteous causes. But much like actual rivers, it is not so easy to change the flow of money. Even if we attempt to build a bank, it is doomed to crumble eventually. All we have been able to do is watch the floodwaters sully beautiful land with its mud.” Canaan placed his hand on the large desk in the office and leaned forward. “But then you appeared, Twilight Cardinal. You are the one who can right the Church’s wrongs.”

When Canaan looked right at him, Col’s words failed him.

Hyland spoke up instead. “You have exposed the corruption and the wicked accumulation of wealth in churches across several cities, but not in a manner that has expressed any contempt for the Church. In fact, facing the people in such a manner has only restored the people’s respect for the Church, whose reputation was in tatters.”

“And we found hope in you,” Canaan said. That easy smile of his no longer graced his face—his expression was one of hardened resolve.

But he became aware of his excitement; he suddenly cleared his throat and reclined in his seat.

Hyland then spoke again, as though willing to entertain them while Canaan regained his composure.

“We in the kingdom worked with clergy who stood against corruption in the Holy See once, before this conflict with the Church. As you know, there were more than a handful of churches within the kingdom that wielded absolute control over matters of trade and were wrongfully accumulating wealth.”

“I reached out to you, Heir Hyland, because of that history.”

That meant Canaan’s proposal was not something that had suddenly occurred to him and he prepared in a fit of desperation; it was an extension of work that had already been underway in the Church’s long history.