I. EMPLOYMENT

1

“THE HUMAN MIND IS A CONFLUENCE of language and imagery,” I said, the lectern’s microphone projecting

my voice throughout the auditorium. “Now, when I say ‘language,’ I am of course referring to the words we all use on a daily basis. They’re the fundamental building blocks of meaning and the tools with which we express ourselves to one another. Imagery, on the other hand, is a bit trickier to pin down. Perhaps the quickest way to describe it would be to say that it refers to any other type of thought that occupies our minds—things that are too difficult, or abstract, or outright impossible to express in words.”

My words echoed loudly throughout the venue, at the same volume as I heard it on the monitor, which made sense, given that there were few obstacles to dampen the sound waves. Of the two hundred and forty seats in the auditorium, only six were filled with live spectators.

“When we see an apple, for instance,” I said, “we first create a visual image of what we’re seeing in our minds. We recognize its red coloring, its rounded shape. But until we connect that image with the word ‘apple’ in our heads, it remains only that—an image. Not that there is a problem with this, mind you. Unless there’s a pressing need to verbally convey something related to that apple to someone else, that image is all our brains really need.”

I noticed an elderly woman in the audience nodding at this. For whatever reason, it felt like I was getting a much greater volume of immediate feedback here than I ever did during the lectures I gave online—but perhaps my mind was simply playing tricks on me.

“The same can be said for auditory experiences or tactile experiences,” I continued. “We render all sensory information—textures, sounds, smells, tastes—as ‘images’ that can only be viewed by our mind’s eye. In the philosophy of the mind, we call these images qualia, while in linguistics, they’re the signifié, as opposed to the signifiant.”

The old woman was now closely examining the personal aerial holofield projected directly before her, which should have just brought up dictionary entries for the technical terms I’d thrown in at the end. These were not the sorts of concepts one could grasp just by reading a quick summary, of course—but that was precisely why I’d chosen them to help emphasize my point.

“Yes, those words you’re all attempting to decipher right now? That’s language. And unless you’ve all been classically trained in my specific field of expertise, I assume you can see what I mean when I say that language is an awfully slow and inefficient way for one brain to communicate ideas to another.”

This got a good chuckle out of the old woman, and so I smiled back at her.

“What if I could simply share with you all the ‘mental images’ I associate with each of these concepts, and transfer my understanding of them directly into your brains? You’d all be able to instantly comprehend any topic I might wish to explain. But unfortunately, this just isn’t possible with our current technology. So instead, I must simply try as best I can to encode those concepts into words, which your brains can then attempt to decode into your own mental image—and who knows whether the end result will be anything like what I meant to convey? But I suppose I’m getting a little off topic. Here’s all I really want for you to take away from this lecture today.”

The presentation automatically advanced to the next and final slide, which featured only a single line of text:

Overcoming our mental limitations.

“In many ways, images are the default language of the human brain—a language that’s extremely difficult to perfectly decipher or translate. But we still must try, or else even our most brilliant ideas would die without ever being shared or built upon. We could not progress as a society without a logical and communicable form of thought, and so we developed language as a means of overcoming those mental limitations. It is only by distilling the contents of our minds into words that our thoughts are given form and made apprehendable to those around us. And I believe that by making an effort to express our feelings in words as much as possible throughout our day-to-day lives, we can also develop a deeper and richer understanding of ourselves. You might even say it’s the single most important step toward cultivating true, long-lasting mental health.”

I looked down at the holofield in front of me. There were exactly 370,000 viewers on the livestream. Add to that the six people in physical attendance, and a grand total of 370,006 people had stuck around until the end of my lecture. And yet, I addressed my final remarks to one elderly woman in particular.

“Thanks so much for listening,” I said, then stepped down from the podium to paltry applause and an uproarious number of “likes” as the presentation returned to the title slide.

Psychology in Our Everyday Lives

Cultivating a Healthy Mind

Dr. Seika Naisho, Psy.D.

As soon as I stepped back into the wings, the young man in charge of planning the event ran over to me like an excited puppy dog, with a spark in his eyes to match.

“That was incredible, Dr. Naisho!” he said. “Really powerful stuff!”

His passion for my lecture was so intense that my only response was a sheepish smile. I knew going in that he had to be quite the psychology enthusiast to ask me to do a largely pointless live event here.

“Honestly, the only thing I didn’t like about it was that it was over so soon! Fifty minutes is hardly enough time to even scratch the surface of your expertise, Dr. Seika!” he said, calling me by my first name like we were old friends—which struck me as particularly funny, because I couldn’t remember either of his. “So hey, if you’re not busy later, I was thinking maybe we could get lunch or something?”

That was a bridge too far. I let my annoyance show plainly on my face. This emotion was one I never had any trouble converting into words, yet it seemed for once, I was able to convey my thoughts completely nonverbally, as he immediately shrunk back. With a prayer that he’d take the hint, I gave a little bow and turned to leave—but the annoying puppy-boy insisted on seeing me all the way to the door.

“I really mean it, though!” he said. “You did some truly inspiring work today!”

Now this choice of words really rubbed me the wrong way. He was just a blatant ass-kisser at this point. Yet still, I tried my best to be professional.

“That’s very flattering, thank you,” I said with a smile. “But really—psychology’s only a hobby.”

2

I stepped out the front door of the Tachikawa Cultural Center and into the bustling afternoon rush of the city. Uniformed schoolchildren on their way home, homemakers walking around with bags upon bags of brand-name goods dangling from their arms, a group of middle-aged men filing into a nearby sports gym—everyone was living out their happy lives with healthy minds. While I knew that, for most of human history, mental illness had run rampant, these days, it was getting exceedingly hard to find anyone suffering from poor mental health. This made my personal field of study rather niche, as it was now virtually irrelevant to modern society, but I didn’t mind. I studied psychology because I liked it, and that was reason enough.

After thinking it over for a moment, I decided to head out on my own two legs and join in with the healthy people walking down the street. A little stroll now and then couldn’t hurt, and I was already here in the heart of downtown, so I might as well head over to the collection mall in the station building and pick up a few things.

At the mall entrance, I picked out a collection bag with a stylish design, then headed immediately to the general goods department. Though you could easily examine items from any angle on NetCollect and have them shipped straight to your door, I still preferred to pick out some things in person; it was pretty hard to tell how charming a given knick-knack was from the 3D render. In person, I was able to quickly pick out a simple mug with an interesting pattern I rather liked and stash it in my bag to take home.

Then I headed over to the clothing department. I’d never been the type to keep a hoard of clothes I never wore in my closet, so it felt like a good idea to have a few nicer outfits ready in advance. In case of another public speaking event, so I wouldn’t have to scramble to put together a look at the last minute as I had today. I picked out a smart, all-purpose public outfit, as well as a few articles of seasonal attire. My bag was already growing fairly heavy, so if I saw anything else I wanted today, I’d opt to have it delivered.

As I was making my way to the next floor, I passed the furniture department, where a floor display caught my eye. It was a striking lounge chair with curved wooden legs weaving around and intertwining with one another, almost like a thing alive. When I sat down to try it out, it was far comfier than I’d imagined. I decided to order it right then and there.

“I’ll take one of these,” I announced. Titan immediately picked up this command via one of the floor’s omnidirectional microphones and emitted a gentle electronic ding to inform me my order had been processed for delivery. This was turning out to be a very fruitful collection trip indeed—maybe I should come into town like this more often.

Then I stopped by the café on the seventh floor. I gazed out over the city of Tachikawa spread out below me. Then I glanced down at my wrist, and the current time appeared in midair. It was still only three in the afternoon, and I had no plans for the night. As I contemplated what to do with my time, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the young man from earlier—the event planner who quite clearly had a thing for me. I knew there were plenty of men like him out there in the world, but this was the first time I’d actually met one in the flesh.

A classic romantic.

Someone who believes in love at first sight, who knows in their heart that they’ll eventually meet their soulmate by pure coincidence in the natural course of building interpersonal connections in daily life. While this was obviously unrealistic and inefficient in the extreme, there was something to be said for the fact that just taking advantage of random meetings had been the predominant way that people got together for most of human history—and we hadn’t gone extinct yet. One might even argue that overcoming inefficiency through the application of sheer numbers was the sine qua non of natural selection. Love and romance were, after all, just a means to the biological end of reproduction.

Come to think of it, I’ve been having a real dry spell for a long time now, haven’t I…

I thought back, and I soon realized that it had now been almost two years since I last tried my hand at dating, love and all of the various acts so implied. There wasn’t a single part of me that regretted turning down that puppy-boy’s lunch invite, of course, but I couldn’t deny there was something about his passionate pursuit of deeper connections that had left an impression, albeit a minor one. But I could never see myself adopting his methodology of approaching more or less anyone who might be remotely interested. This was the 23rd century, after all—I had an array of modern tools and conveniences at my disposal.

“Matchmaker,” I whispered. Immediately, an aerial holofield of search results appeared atop my little cafe table. It had selected for me several candidates of my preferred gender, each entry accompanied by a little blurb and overall compatibility rating that took into account our respective preset criteria and personal tastes. The top candidate had a compatibility rating of 84 percent, more than enough to warrant a date. I reached out a finger to select him when suddenly, several of the results disappeared and were immediately replaced by new ones.

The top candidate in the newly refreshed search results boasted compatibility of a whopping 98.1 percent—a rating I didn’t even realize was possible. I’d never seen anything remotely close to it before. My eyes went wide as I tried to imagine what type of person could ever be nearly 100 percent compatible with me. I selected the option to request a meetup as fast as I could. In no time at all, he accepted, and we officially had a dinner date here in town set for 7 PM.

3

Because there were still several hours remaining before my date, I killed some time by heading out into town and resuming my little stroll from earlier. While Tachikawa wasn’t all that far from home, I’d only come here a handful of times in my entire life and wasn’t overly familiar with the area. Walking just a single block away from the main drag where all the local public services were located brought me immediately out into a quiet residential district. Here, the only notable sounds were the twittering of little neighborhood birds and the occasional motorized hum of a dropbot’s propeller buzzing by. After walking a bit, I eventually came to a lot that was covered on all sides by a massive transparent tarp. Curious, I peeked inside—only to discover a constructor phalange currently in the process of building a new house on the property.

“Well, would you look at that,” I murmured as I stopped to marvel at the highly unusual sight. Most construction work of this nature was generally done in the wee hours of the morning so as not to disturb the local residents, so I could only assume there’d been some unforeseen irregularity that resulted in the phalange’s work dragging well into the middle of the following day. Not that I had a complaint since I got to bear witness to a seldom seen aspect of society. Like a child on a field trip to a production factory, I watched the construction work unfold with rapt attention.

The constructor phalange was equipped with several swiveling bendable arms and a large tank full of liquidized construction material—generally a type of synthetic photopolymer that rapidly hardened upon exposure to light at a specific wavelength—attached to its walking base. The photopolymer was dispensed by nozzles on the “head” of each arm and layered to create extremely complex structures in no time at all. I was, admittedly, not familiar enough to recognize the material in the phalange’s tank as that photopolymer on sight—I just knew it as the material used to construct virtually all residential buildings.

I watched as the phalange scurried around the construction site on its crablike legs. Judging from the size of the plot of land, and the framework it had already completed, I guessed it was constructing a residence of perhaps fifteen or twenty rooms. This was a reasonable amount of space for a single adult to live in, and in a fairly nice area too—I honestly wouldn’t mind moving in if it didn’t immediately get snatched up by someone else. I’d forget if I didn’t actually make a note of it, so I told Titan to remind me to check for the listing later, and it responded with a little electronic ding. I stood watching the constructor phalange go about its work until the sun began to set, then set off at a brisk pace toward the restaurant.

4

When I stepped inside the little French place where we’d made our reservation, I saw that my date had already arrived. The bespectacled young man flashed me a gentle smile and rose from his chair to greet me.

“Hi there. Naoyuki Takasaki,” he said.

“Seika Naisho.” I bowed slightly.

“Oh, uh… Here, let me get that for you!” he said, flustered, as he came around the table and pulled my chair out for me. I smiled politely and sat down. We then proceeded to make small talk and get to know one another a little bit as we waited for our food to arrive.

At 28, Takasaki was two years older than me but was so energetic and sociable that I would have thought him younger. His primary hobby was ballroom dancing, and he was so passionate about it he even participated in regional competitions. Being the modest guy that he was, he immediately downplayed this by insisting he was all passion and no talent.

“Of course, it doesn’t help that I’m at a natural disadvantage in the looks department already. Hard to stand out from the crowd when you’ve got a face as plain as mine,” he said bashfully. I honestly didn’t know what to do with myself; he was so my type, it was uncanny. Not that Titan’s matchmaking service had ever done me wrong in the past—generally, my personal assessment of the guys I’d dated more or less aligned with the compatibility rankings they’d each been assigned beforehand. But now that I was sitting straight across from a 98.1 percent match, I couldn’t believe the difference between him and every other guy I’d dated.

I loved plain-looking men. Loved soft-spoken guys with a humble demeanor. Loved the type of person who you could tell wasn’t obsessed with being in charge. He was exactly my type in just about every way I could think of. I had to give Titan major kudos for selecting this total catch for me.

Our food came, but we continued talking between bites, thoroughly enjoying each other’s company and the instant rapport only people with a 98.1 percent compatibility rating can experience. With only a 1.9 percent margin of error, the conversation flowed effortlessly back and forth, with no friction whatsoever—like a pair of figure skaters on the smoothest of ice. It was an extremely delightful meal. But right around the time our bottle of wine ran dry, we hit a small bump in the road.

“So hey, um… I wanted to ask you something, Naisho,” he said, then paused for a long and awkward moment before continuing. Almost like he knew what he was about to say would completely kill the evening’s momentum—and sure enough, it did. “How do you feel about…work?”

“Work?” I said, widening my eyes in confusion. “As in work-work?”

“Correct.”

“I mean…”

I trailed off, and the conversation died. My confusion was justified; it was a ludicrous question to ask so boldly, especially on a first date, especially to a woman you’d only just met. I had no idea of his intentions, nor what he was hoping to get out of this date. To even broach the subject of work was highly eccentric—something he understood well, judging from the sudden burst of flop sweat coating his face.

Wait a minute. Perhaps this was the missing 1.9 percent of compatibility rearing its ugly head. Assuming it was, then it would be best to find out right here and now whether it was a 1.9 percent we could paper over, or the minuscule difference between us that we’d never be able to move past. And so I answered this exceedingly bizarre query in the most careful, unassuming, and predictable way I possibly could—hoping it might draw out his true colors.

“I’ve never worked a day in my life, so I guess I wouldn’t know…”

5

“Right… Yeah, no, of course,” Takasaki said as though it were the most obvious thing in the world. “I mean, I’ve never done a day’s work in my life either, so neither would I.”

Work. A word only used today in purely idiomatic contexts, so it tasted strange and unfamiliar on my tongue. I tried to recall what I’d learned about the antiquated concept back when I was in school.

It all started around a century and a half ago. Up until the midpoint of the 21st century, the vast majority of human beings on Earth had “occupations” they needed to perform in order to live—or so my social studies textbooks explained. But then, right around the year 2050, the Labor Revolution began, and work was slowly but surely phased out from the lives of the general populace. And now, here in 2205, work was nothing more than a memory—a primitive social construct from an age gone by, now obsolete.

“Right, and it was already mostly abolished by the time we were born, so…” I said, fumbling around for anything more I could possibly say on the subject. Strictly speaking, work had actually not been completely abolished yet—but the few remaining traditional jobs were all highly specialized and reserved for a small handful of uniquely qualified individuals. Still, it was something ordinary citizens never even had to think about, so from our perspective, it had indeed been effectively abolished. “Yeah, sorry… Not sure I’ve ever really thought about it that much. It’s just so far removed from my own life, y’know?”

“No, no! It’s fine!” he assured me. “That’s totally understandable. Sorry for killing the mood by bringing up such a strange subject. I’m pretty much in the same boat as you, honestly. Don’t know that much about work, nor do I really feel any desire to have a job myself. I guess I’m just curious, is all.”

“How so?”

“Well, I guess I just like to imagine these types of things. Like, if I were employed, what would my job be, and how would I feel about it,” he said. “That sort of thing. Would I find it fulfilling and want to keep doing it, or would I hate my life and want to quit?”

“Hm. Yeah, I guess that is kind of interesting to think about.”

Takasaki’s face lit up at this reply. He was very relieved that I’d finally taken the bait and shown an interest in this somewhat controversial topic, which he’d brought to the table knowing full well he might turn me off completely. And while I was mostly just being polite, he had piqued my curiosity about work—albeit in the same way one might find a history program and get sucked in to watching it. I tried to put myself in the shoes of someone who lived in the days when work was still an everyday thing for a majority of people.

“Well, I can only assume you’d feel a lot more stress than you do now,” I said. “I mean, when you have a job, you generally have a lot of responsibilities, no? Imagine being under that kind of pressure, day in and day out, where one little mistake could screw things up for a lot of people, and maybe even cost you your livelihood. It’s kind of stressing me out just to think about, honestly.”

All of what I’d learned in school came back to me now. To have a job meant donating your labor to an employer, taking on responsibilities, and suffering potentially brutal working conditions in exchange for some form of compensation. And once you got started, it wasn’t easy to change your mind and resign. Though I wasn’t entirely sure how that meshed with the whole “free labor” idea I’d read about, which supposedly allowed people to change jobs at will.

“True, but you also had the right to choose what you were or weren’t willing to put up with,” said Takasaki, almost as if he’d read my mind. “Everyone had the power to choose their own career. Though obviously, that all depended on your ability to establish a working agreement with your desired employer—er, that is, the people who gave out the jobs.”

“Couldn’t you also just work for yourself, though?” I asked.

“Well, yes, in a way. Supposedly there were people known as ‘freelancers’ and ‘sole proprietors’ who did essentially what you’re describing,” he said, spouting highly specific terminology right off the top of his head. He was clearly more passionate about this subject than he initially let on. “Basically, they were people who did their jobs all by themselves without having to answer to one specific employer. But even they had to participate in the system somehow, trading their goods or services in exchange for remuneration. Because you can produce as much product or content or services as you like, but it’s not work unless you get paid for it.”

“Right…” I said.

The concept of payment was about as foreign to me as that of work. Obviously, people still produced plenty of things themselves in the modern era. But we couldn’t really call it work, because nobody was compensated for their labor. For most of recorded human history, when people performed a job, they got paid for it in the form of “currency,” which they could then use to “purchase” whatever needs or luxury items they could afford. The exchange of currency was an advanced form of barter, but the whole system of wage labor had already been abolished by the time I was born. My only firsthand experience with money was a vague memory of my grandfather showing me some coins and paper bills he’d kept stashed away from his own youth. To think our entire society once revolved around the exchange of those little pieces of paper. Such was the nature of the monetary economy.

“God, it all sounds like such a pain in the ass,” I muttered, letting my disdain show with a disgusted sneer. I knew it probably wasn’t the best way to endear myself to a man on our first date, but I couldn’t help it—the mere thought was enough to annoy me. Thankfully, my date was kind enough to laugh it off.

“Yeah, definitely not the most efficient system, was it?” he said with a chuckle. “Imagine if every time you wanted to do or get something, you had to first convert something of yours into money, then go reconvert that into whatever it was you were originally after.”

“What a waste of effort. So pointless.”

“Mmm… I’m not sure I’d go quite that far. I think there was definitely good reason to have a system of stockpiling value one degree removed from the flow of trade, at least in the context of the time. You have to remember that scarcity of goods and resources was a big deal back then, so you couldn’t always just get exactly what you wanted right when you wanted it.”

“Right, so you’d have to wait, but you could hold on to the money in the meantime,” I said.

“Easy to forget now that we’ve got more than enough of everything for everyone, isn’t it? Obviously, it helps that we mostly only produce things to meet the precise level of demand now, but still. I mean, do you have any idea how small people’s houses used to be back then?”

“How small?”

“Like, one bedroom or less, on average.”

“How is that not a human rights violation?”

He burst out laughing at this, but I remained completely stone-faced. I genuinely could not fathom anyone ever living in a space that small. Hell, even dog houses were typically a bit bigger than that.

“Just wasn’t enough housing space for everyone,” he explained. “At least not where the jobs were at. There weren’t dozens and dozens of vacant houses sitting around, waiting for anyone to move in.”

“But weren’t they building new ones all the time?” I asked. “Surely, you could eventually build enough to meet demand…”

“Not when you can’t afford to service and maintain them all properly.”

Finally, I saw his point. Right, of course. In the past, all of the necessary work to build, clean, and maintain housing stock was done by people. And that work cost time and money.

“In this modern era,” he said, “we can clear out as much land as we need, build houses as big as we want to, and easily keep them in perfect shape even when they’re vacant. But back then, there just wasn’t enough labor to go around. Or land, or houses, or resources, for that matter. So all people could really do was live in these tiny little dwellings, save up their money, and wait around until one of the few houses that not only met their needs, but was also within their means came on the market.”

“When you put it that way, I guess it makes sense that there wouldn’t be enough. Humans can only produce so much by themselves, after all.”

“I know it’s a little hard to imagine nowadays, but yeah. Back then, they didn’t have what we have now,” said Takasaki wistfully. He took a reverent pause before intoning the name of our benevolent provider. “They did not have Titan.”

6

TITAN

That which works so that humanity might rest.

That which supports our species in every facet of our lives.

That which does both of these things simultaneously and automatically.

The common name for the comprehensive and wholly integrated AI processing network that manages virtually all modern industrial equipment, construction machinery, transit systems, and cleaning/utility services, in addition to a vast array of lifestyle support sensors and interfaces. Also: colloquial term for any individual node of the network.

In the latter half of the 21st century, major technological advances in the field of artificial intelligence gave rise to a massive boom in automated services and autonomous devices. All motor vehicle manufacturers transitioned to self-driving models, and great strides were made in industrial robotics, opening the door to fully self-regulated factories. The need for human labor input and even management gradually grew irrelevant, and before long, the majority of the sentient workforce was replaced by fully automated robots capable of maintaining peak productivity twenty-four hours a day. Though this ultimately cost most people their jobs, there was little in the way of social upheaval beyond the initial transition phase. While many skeptics were quite vocal in expressing their opposition, their concerns were soon allayed by the sheer uptick in productivity and output made possible by a fully automated economy.

No longer did someone have to work in order to put food on the table. Quite the contrary, in fact—food was more plentiful and readily available than ever now that humans abandoned the field. The advent of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) and its associated optimizations ushered in an era of plenty never before seen in history. And there was no key player, no facet more integral to this revolution than the introduction, during the latter half of the 21st century, of the universal standard AI known as Titan.

Primitive AI technologies existed even in the 20th century. But the market for such technologies was scattershot and slow to advance due to major corporations developing and patenting mutually unintelligible and competing AI systems. AI development would be stifled for decades until the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) finally stepped in to resolve this state of affairs. The UNDP, in collaboration with teams from each of its most developed member states, spearheaded an ambitious project to develop a next-generation universal AI system. Their aim: to create a persistent AI constructed to adapt and evolve to meet the needs of human society indefinitely. And the only true way to ensure this longevity was to design an artificial intelligence not only based on human intelligence, but modeled after it.

In 2048, the UNDP announced its new universal standard AI format: Titan. It was a composite AI composed of both a core intelligence engine and several compatible branching subdivisions that could easily be further developed and iterated upon. True to the original developers’ intent, that central intelligence core modeled after human intellect has remained completely unaltered for over 150 years since its inception, while the branching subdivisions and their corresponding applications have seen exponential evolution and are constantly being improved upon, even now. In a way, one could say that every AI system in use today is both Titan and a derivative thereof simultaneously.

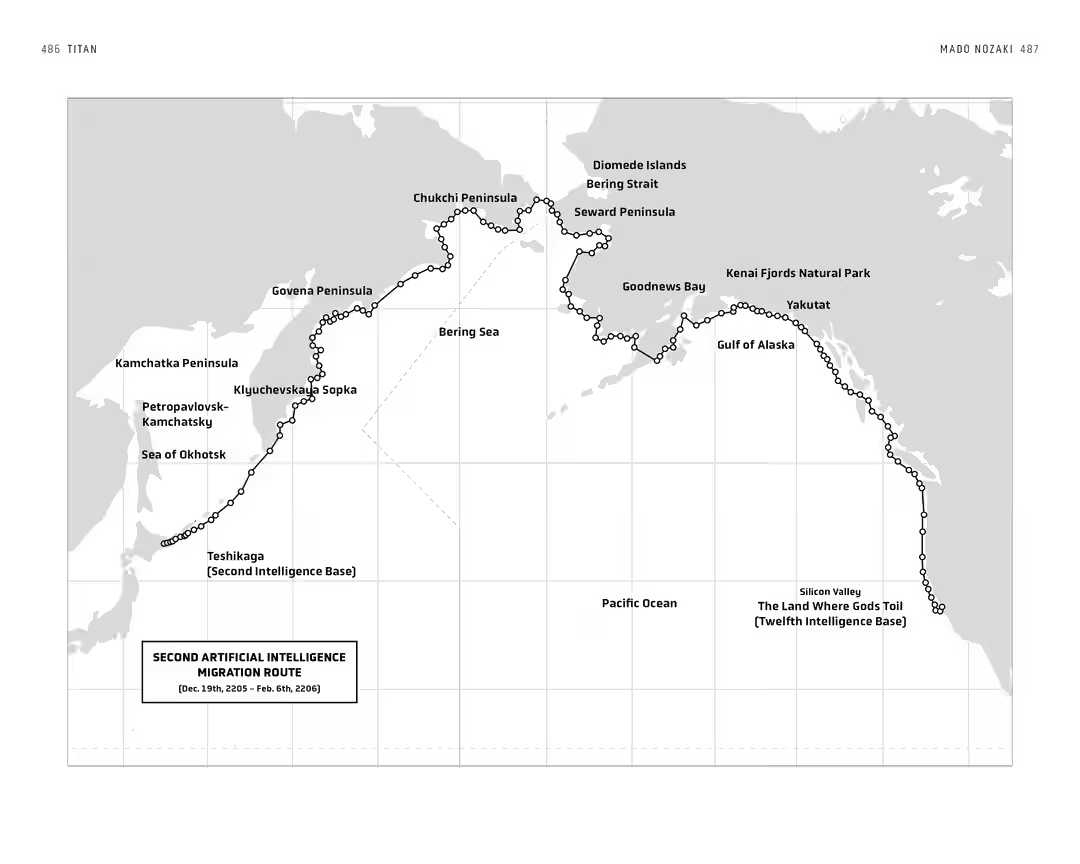

Now, in the year 2205, Titan is more than one and a half centuries old, and its central “brain” continues to perform its autonomous functions in twelve interconnected AI facilities across the globe known as “intelligence bases.” It is in these intelligence bases where the foundational Titan AI does all of its thinking—constantly racking its brain for our exclusive benefit, just as it has done since the end of the era of travail.

And now that all robotics across the world are connected to the Titan network, they have effectively become an aspect of Titan themselves. It is now commonplace to use the word “Titan” to refer to the AI network or its subdivisions, and the word “phalange” as a common noun to refer to any robot whatsoever.

7

I pored over the introduction of the treatise again and again. A lot of this was stuff I vaguely knew already, but it was good to augment that understanding with some facts. My view was soon obstructed, however, by steam from the two hot mugs that had just been wheeled out and left between me and the aerial holofield on which I was viewing the book. The autojeeves, having successfully carried out its work, quietly scurried off back to its little alcove.

“Hope coffee’s all right,” Takasaki said as he came to join me in the center of the massive living room. I nodded approvingly, so he finally permitted himself to relax and sat down next to me on the floor. We’d come back to his place after dinner, which I found to be surprisingly spartan for a single twentysomething’s bachelor pad. This was clearly not a man with a very wide range of interests. He was currently in the process of showing me some books he’d recently acquired on the subject of work, per our dinnertime discussion.

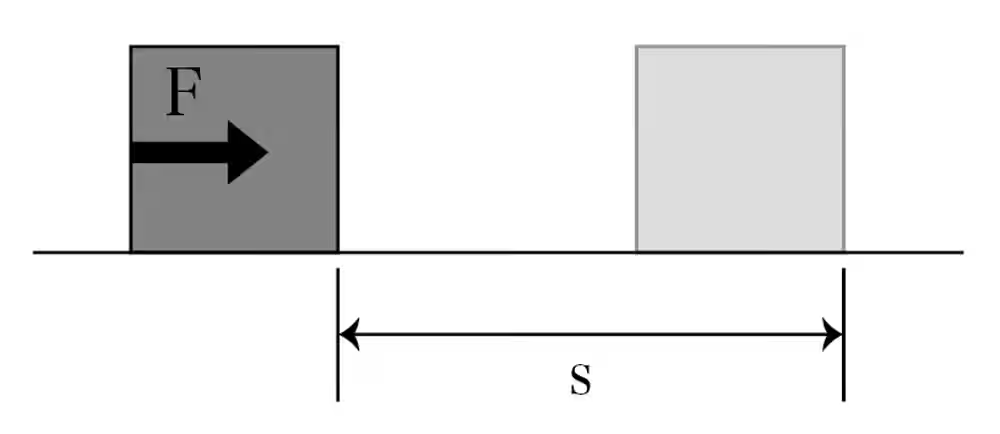

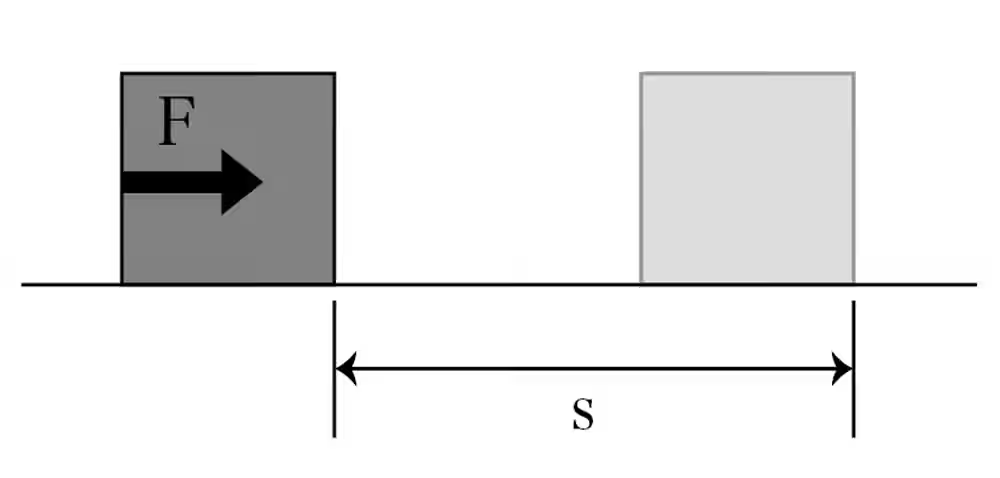

“Work sure did change an awful lot right after Titan was introduced, didn’t it?” he said, reaching out his hand to swipe over to the next page. “Look, this is a picture of the average workplace from just before.”

I stared at the photograph. There were a bunch of tables arranged in a haphazard fashion across a wide open space with chairs clustered in between. I looked down at the caption and saw a word I didn’t recognize.

“What does ‘open-plan’ mean in this context?” I asked.

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “An open-plan office was basically just one big workspace where employees could sit wherever they wanted. Designed to give workers more freedom and make them feel more comfortable, I guess.”

“Seriously? This?”

I looked down at the photo again. There was not nearly enough room for anyone to call that comfortable. And the chairs were so close together, I didn’t see how anyone could be expected to focus on anything with another person sitting one seat over. First the thing about one-bedroom residences, now this. I couldn’t believe the brutal living conditions people from only a few generations ago apparently had to live with. Meanwhile, here we were in the modern day, completely freed from the necessity to work, with goods aplenty to order at will from the comfort of our spacious living rooms. And we owed it all to Titan.

“God, we really are lucky to have been born in this day and age, aren’t we?”

“You can say that again…” said Takasaki.

Something brushed against my fingers. I looked down to see that he’d set his hand right next to mine on the rug. We looked up, our gazes met, and we both knew. We could feel the chemistry in the air. The matchmaking service had officially achieved what had been asked of it. And yet all of a sudden, I felt a wave of hesitation wash over me.

“Sorry, could you give me a minute? Where is your bathroom?” I asked, mercilessly killing the mood in one fell swoop.

As I stood there looking at myself in the bathroom mirror, I tried to think things over again. Takasaki was, by all appearances, exactly my type. By far the most appealing man I’d had the pleasure of meeting thus far, and I highly doubted I’d ever meet someone so impossibly compatible with me again. He was the ideal partner, as far as I was concerned.

And yet for whatever reason, my heart was pumping the brakes.

Maybe it was the way everything felt a little too perfect that unnerved me. Perhaps my brain was refusing to accept that this guy, who felt tailor-made for me, could possibly be real. Or maybe I preferred a bit more unpredictability, and the way everything was going so smoothly felt almost artificial. Whatever it was, I couldn’t explain it. All I knew was that from a logical standpoint, this was exactly the guy for me—but something in my subconscious was telling me I shouldn’t go through with it. And I generally trusted my intuition when it came to things like this.

I walked back out into the living room and did my best to force a friendly smile.

“Hey, sorry about that,” I said. “I think I should probably head home for the night.”

8

By the time I made it back home, it was already after midnight. As soon as I walked in the door, Titan informed me that I had one new message, but it would have to wait till morning. I was much too exhausted from the long day I’d had. I stepped up onto the zoomboard waiting for me in the entryway; I knew it was healthier to walk, but I’d done enough walking today for an entire month, so I felt entitled to a moment of laziness. Once I stepped aboard with both feet, the device set off gliding down the hall and brought me straight to the bathroom. Only once I’d stretched myself out in the piping hot bathwater did I start to feel the various tensions of the day begin to seep away from my weary limbs. When I got out of the tub, I headed over to the cooldown room and laid down on one of the lounge chairs. The conditioned air inside helped to gradually cool my flushed skin.

“Contacts,” I said. Titan pulled up an aerial holofield in front of me displaying a list of all of my contact cards. At the top was the personal information card for my most recent contact: Takasaki. I thought back on what had transpired just two hours prior. While I did still wish I’d have gone through with it, there was also no need to rush these things. I could always contact him again whenever I wanted. And I had a long life ahead of me.

Technological advances had given humans much more leisure time than they once had. Not just because we no longer had to spend so much of our lives working, but also thanks to bold new medical innovations. The vast majority of diseases considered incurable even two hundred years ago were now all but eradicated in the modern era. Titan handled all medical research and treatment. Life expectancy had increased dramatically, and with the introduction of Planned Aging, people could now choose a life extension plan when young that made it possible to sustain peak physical health all the way up to the age of 150—though few chose to actually do so. As it turned out, not many people knew what to do with decades of free time and perfect health.

I put on the pajamas that had been laid out for me, then hopped back on the zoomboard, which ushered me out of the cooldown room and into the room next door. Once I was inside, the door shut behind me, and the lights turned on at the dim preset level. I was greeted by a wall covered top to bottom with developed photographs. This was my darkroom, which I used to develop pictures I’d taken using a classic film camera—my longest-standing hobby and passion, aside from psychological research, of course.

I stepped off the zoomboard and walked over to my work table. The room was filled with a variety of specialized equipment—a water station, a wastewater station, a drying station, an enlarger, a retouching space, along with various chemicals and other tools—none of which would be necessary if I would just use an ordinary digital camera. Film photography was a very labor-intensive and time-consuming hobby, but that was exactly what I liked about it. When, on occasion, I tired of the exercise, I let my automated developer handle everything for me.

Once again, I thought back to my earlier conversation with Takasaki. Back in the days of the monetary economy, when scarcity was always a concern, I would have had to exchange money for each individual roll of film and think twice before each and every shutter click, all in the interest of conserving limited resources. Now, I could have as much film as I wanted without even having to ask; even if I forgot to resupply, Titan would ensure I always had a refill handy. Once again, I found myself feeling extremely fortunate to have been born in the current era.

I took a couple steps back and looked over my wall of photos as if scrolling through a list of thumbnails. All of my recent pictures had been taken locally and were fairly mundane. I traced my finger back along the line to the most recent batch of travel photos I’d taken, and realized that more than half a year had passed since my last trip. Suddenly, that familiar urge for adventure took hold of me once again. Tomorrow, I would research potential destinations. But for tonight, I was much too tired.

I stepped back on the zoomboard and rode it over to my bedroom, pondering drowsily as to what else I might do tomorrow. Not that it really mattered—I could just do whatever I felt like doing when the time came to decide. And if I changed my mind later, I could always stop and do something else. There was no urgency, and no outside pressure that could make me do anything other than exactly what I wanted to do. I climbed into bed, closed my eyes, and let sleep whisk me away. Titan, my ever-watchful companion, dimmed the lights down low—just as it knew I liked.

9

As I ate my breakfast the next morning, I checked the unread message I’d received the night before. It was a report on the status of the developmental psychology thesis I’d published last month, which had apparently done quite well for itself. I opened up the page to take a look, and saw that it had indeed garnered a fairly impressive number of views and user ratings. My work had achieved circulation well beyond that of my usual tight-knit community of loyal followers and had expanded into the wider social sphere, the result of it having been picked up by some larger scientific news outlets.

While I obviously didn’t publish just for the clout, it still pleased me that my work had been read by a great number of people. There were far too many comments for me to reasonably read however, so I asked Titan to sort them in descending order of “things I’d most like to read” and “most valuable/constructive feedback.” But while Titan’s sorting algorithms were generally extremely discerning and reliable, they did make mistakes from time to time. Like just now—the number one comment the system returned wasn’t even really a comment at all, but a mysterious photo of an indistinct, semi-transparent purple silhouette cast over a grassy meadow. I tapped the little icon to indicate that this was not the type of comment I was looking for, and the system quickly re-sorted the results in response to my feedback. This time, it did a much better job.

I glanced at the top few comments, which were primarily from passionate psychology enthusiasts like myself. There were even a few well-known and respected names among them, offering me constructive criticism and some much appreciated advice. One in particular that stood out suggested that I “might also find 21st century clinical psychology and its related literature of interest.”

Clinical?

This was a word I had to look up. The dictionary even pronounced it for me, as Titan knew I’d never spoken the word aloud in my life. A “clinic” was a facility where sick patients could go to receive treatment or advice from employed medical professionals, and “clinical” similarly referred to the field of medicine relating to the observation and treatment of patients outside of a theoretical or laboratory context. That is why it was such an unusual term—it was a remnant of an age gone by, when medical treatment was still administered by human hands, and there was an entire class of working professionals known as “physicians.”

Now, all of humanity’s medical needs were handled by Titan. Examination, diagnosis, medication, surgery—all of these were things that an AI was far more well-suited than we were. Humans were fallible creatures, and when lives were on the line, why would you not want to minimize risk factors? Automated medicine was simply better for all parties involved—though of course I knew that people in the past didn’t have that luxury.

“But what would clinical mean in a psychological context?” I wondered aloud.

I swiped over to my library. Titan had already predicted the terms I wished to search, and pulled up a list of results in descending order of relevance. Sure enough, there did indeed seem to be a field of psychology known as “clinical psychology,” and a related term “clinical psychologist” to refer to those who practiced it as their primary occupation.

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST (COUNSELOR)

A specific type of psychologist specializing in the treatment, mitigation, prevention, and study of psychological symptoms and abnormal behaviors resulting from various mental illnesses and psychosomatic disorders. May also refer to one whose focus is on the betterment, preservation, promotion, and education of mental health in a broader societal context.

Interesting. This did sound right up my alley. Apparently, educational facilities even used to keep “school counselors” on staff to help guide children on the path to becoming successful adults, which seemed to suggest a fair bit of overlap with developmental psychology. I found it hard to imagine that one or two clinical psychologists could possibly provide effective counsel for an entire school’s worth of students. That seemed more like a job for Titan to me.

My entire holofield was filled to the brim with new and interesting bits of information. Whenever a specific phrase or factoid caught my eye, Titan’s predictive behavioral monitoring systems would sense my growing interest and bring up the exact information I wanted at that moment in time. I’d read that in the past, there was a type of worker known as a “valet” whose main job was to provide various kinds of support to another human being throughout their everyday life—so in a sense, you could say that Titan was humanity’s collective valet. Here I sat, gazing out from my comfortable seat at the lovely trail of well-sorted articles and essays it had laid out before me. But just as I began to hunker down for a nice, relaxing morning read, a massive obstacle popped up on my screen—one that even Titan couldn’t proactively clear away for me.

It was an appointment message from Takasaki, requesting a second date. I was a little taken aback by this; he was following up sooner than I expected, given how things ended last night. Normally, this might have come off as desperate, but I kind of liked that bumbling awkwardness about him, so he didn’t lose any points with me. And considering I still was very interested in getting to know him better myself, I saw no reason to play coy. And so, after factoring in how long it would take me to get through this reading material and also bathe and make myself presentable, I told him I’d be delighted to meet up with him at eight o’clock this evening.

10

The courtesy car dropped me off outside the bar Titan had selected for us with plenty of time to spare. I felt a little bad for making him wait for me at dinner yesterday, so I made a point of showing up a little bit early tonight. I stepped inside, then let one of the establishment’s zoomboards ferry me to the private room we’d reserved. It was a nice, open space with a relaxed vibe and soft lighting emanating from the walls. When I sat down on one of the sofas in the center of the room, a list of recommended cocktails appeared on the holofield in front of me. I ordered something light to start off with. I wouldn’t have minded something a bit stronger, honestly, but I knew I should probably show a little restraint around a guy I’d only met yesterday.

When I thought back on how antsy he’d been yesterday, I couldn’t help but smile. Granted, I’d been a little on edge going in, with it being my first matchmaker date in nearly two years, but he was much more nervous—which made it a lot easier for me to let my guard down and act natural with him. We really were exceptionally compatible with one another, and I hoped that we could grow a little bit closer today. Gone was the vague sense of hesitation I’d felt last night. I was fully prepared to have faith in Titan’s judgment and take things to the next level.

After some time, the door clicked open, and I turned to look. A frown crept across my face as I saw that a man had joined me in the private room—but this was not Takasaki at all. That much was clear even at this distance. He was far taller and his skin much tanner—though more than anything, it was his attire that gave him away. This towering gentleman was wearing a very peculiar outfit that you almost never see nowadays, even in the big city. A jacket, a button-up dress shirt, a necktie, and a pair of slacks that together composed a very specific type of outfit, the name of which I knew I’d heard before… Oh, yes. That’s right.

It was a suit.

The man sauntered over to where I was sitting. He wasn’t ethnic Japanese. He looked to be in his early forties, but his facial features were not those of an East Asian—they were more finely chiseled, and his dark brown complexion led me to believe he was from India or elsewhere in southeast Asia. Though perhaps even more striking to me than his distinctive features was his unremitting gaze. The icy look in his narrow eyes felt sharp enough to kill a man. Coupled with his strange attire, it was enough to make him look like an organized crime kingpin straight out of a period drama. He spoke not a single word as he walked over and helped himself to a seat on the sofa opposite me. I was flummoxed.

“Pleased to meet you,” he finally said—and in such fluent Japanese that at first, I couldn’t believe my ears. All I could do was tilt my head in confusion.

“Um, sorry. Did I get the wrong room by mistake, or…?” I asked.

“Oh, I assure you, there’s been no mistake, Dr. Seika Naisho,” he said. “I’m afraid Naoyuki Takasaki will not be joining us tonight.”

“And just who are you?”

The man held out a small rectangular piece of paper, which I hesitantly accepted. Printed on it was a name and address and so forth—a sort of personal identification card, not entirely dissimilar to the digital contact cards of the Titan network. But why in the world did he hand me this information on a piece of paper?

“My name is Narain Srivastava,” he said. “My title is on the card, if you care.”

“Sorry? Title?”

“Right there above the name.”

He pointed, and I looked down at the paper card again.

Director of Safety Administration,

Second Intelligence Base

Intelligence Base Administrative Bureau

Upon reading this, I discerned what he meant by “title.” It was an indication of societal status and the duties entrusted to him—his job title. In other words, this man who called himself Narain was a member of an exclusive class that only a handful of people around the world could claim to be a part of. This man was employed.

“I know it says ‘director’ on there, but that’s more a testament to how short-staffed we are, more than anything,” he explained. “Everyone’s always getting shifted around, and promoted, and relocated all over the damn place.”

The man spoke with a joking candor, but his expression was anything but amused. I couldn’t tell what reaction he expected from me; I was still struggling to wrap my mind around the whole situation. Why in the world was a member of the employment stratum here, speaking to someone like me? And how did he know my name?

“I’ll give you the full rundown here in a minute, but for now, I’ll just cut to the chase. Dr. Naisho,” he began, piercing me with his frigid gaze, “I have a job for you.”

“A job?” I said, eyes wide. “You want me to work for you?”

“That’s correct,” he said, then looked down at the menu on the holofield in front of him and ordered a drink for himself. “Now, I’m afraid there’s only so much I’m at liberty to tell you at this point in the process, and we’re running short on time as it is, so you’ll have to forgive me if it sounds as though I’m oversimplifying. Basically, we’re putting together a team for a very important project, and we’d like you to be a part of it. As a psychologist, that is—and as a specialist in developmental psychology, in particular.”

Narain began to manipulate the holofield in front of him with his fingers. Before long, the bar’s drink menu disappeared, and in its place appeared the very same thesis I’d posted last month.

“We’re currently looking for talented personnel with an acute understanding of human psychology,” Narain said. “We read your thesis, Doctor. And based on our internal calculations, which took a weighted average of a candidate’s various abilities such as general intelligence, technical ability, and areas of expertise, we’ve determined that you are the most qualified candidate for the job. We’re very impressed with your credentials, and are determined to have you come and work for us.”

“Work…” I said, letting the word linger on my lips once more. And to think that work was a concept I’d never given any serious thought before yesterday. “This project you mentioned, what exactly does it entail?”

“I’m afraid the details involve significant classified information, so I can’t give you specifics here. You’ll be fully briefed after you’re brought on board.”

“Would this be particularly strenuous work?” I asked.

“Not at all. It’s a very simple job, actually,” Narain said with a straight face. I frowned skeptically, but his expression remained unchanged. Something told me he was lying and that this would actually be an extremely difficult job—though I had no way of proving that. “In any event, Doctor, I’m afraid I’ll have to request an immediate answer. As I said at the beginning, time is of the essence.”

Just how pushy could one man be? An autojeeves came into the room, delivered our two drinks, then saw itself out again. Narain had ordered a whisky on the rocks, which he helped himself to as he awaited my answer. It seemed I had no choice but to consider this unpleasant man’s preposition.

An actual work opportunity—I’d have been lying if I said I wasn’t curious. It was a part of the world I’d never even brushed up against before. A black box that the vast majority of people would never have the chance to experience. So of course, there was a certain thrill to the prospect of being offered a peek inside. That said, curiosity was not enough to override my misgivings. Even with the understanding that I would be working in my specific field of interest, there was a distinct difference between doing something as a hobby and doing it for a job. All of my preconceived notions about work flashed through my mind. Taking on responsibilities. Stress. Exhaustion. An inability to stop once you’ve started.

“I’m afraid I’ll have to decline,” I said at last, after weighing the pros and cons.

“You’re sure we can’t work something out?” he asked.

“It’s a very enticing opportunity, I’ll admit,” I said, with an apologetic bow of my head. “But it’s just more responsibility than I’m prepared to accept, especially if I have to do so sight unseen.”

Narain let out an overdramatic sigh. I looked up and saw that he was now lying back into the couch cushions, his arms folded and his face an unamused rictus. His irreverent attitude was really starting to annoy me.

“You’re very aggravating, you know that.” I said matter-of-factly.

For a split second, Narain looked taken aback. But he quickly regained his composure.

“Well, aren’t we blunt, Doctor?” he said.

“Only because I find you extremely disrespectful.”

“Let me tell you something, Doctor. If you ever were to work for me, or anyone else for that matter, you’d be forced to deal with other people on a daily basis—some of whom you might not like very much. That’s just part of having a job. It’s called sucking it up.”

“Well, that sounds highly unappealing and frankly absurd to me, so thank you for affirming that I made the right decision.”

Narain took a breath, then sat up straight again. With a few quick finger gestures, he opened a new holofield in an empty pocket of air displaying some sort of documentation and mirrored it on the display in front of me as well. The document was written in stiff officialese that I found difficult to decipher at a glance.

“What’s this?”

“A criminal accusation report,” said Narain, tracing his fingers along the words as he spoke. “You, Dr. Naisho, stand accused of visiting the private residence of the victim, one Naoyuki Takasaki, at approximately 10:30 PM last night.”

I felt my brow reflexively furrowing. “Victim”?

“Whereupon you proceeded to rape him.”

“I beg your pardon?” I said, my eyes going wide as I scanned the document for myself. When I reached the “Victim Report” field, the words “without consent” immediately jumped out at me.

“At just after 11 PM,” Narain continued, “you propositioned the victim to engage in sexual intercourse, which he refused. You then forced penetration without his consent. You are therefore charged with forcible sexual intercourse, a crime that carries a minimum statutory penalty of five years. Though you may be a first offender, your violent and underhanded modus operandi would make a prison sentence very likely, especially given the legal precedent set by Titan’s judgments on similar cases.”

“That’s a completely groundless accusation,” I said, though I was rather shaken. “Is this some sort of farce? Literally nothing happened between us last night.”

“I’m afraid the evidence begs to differ,” said Narain, directing my attention to some new information that had just appeared on the holofield. It was some sort of diagram littered with various labels that combined letters and numbers in some bizarre citation format. The diagram was captioned GENETIC LOCI. “It seems they were able to extract your DNA from bodily fluids left at the scene of the crime.”

“What? There were no ‘bodily fluids,’ I assure you.”

I played back the sequence of events that had transpired the night before in my head. He guided me into his living room, let me browse through his book collection, brought out some coffee, and then…

I went to the bathroom.

“You didn’t…” I muttered. If looks could kill, he would have died on the spot, but he seemed completely unfazed.

“Now, mind you, what I’m about to say is purely hypothetical,” Narain said. “But let’s say you were to agree to sign on to this little project we’re putting together. I don’t think it’s altogether unreasonable to assume that in that case, perhaps a little butterfly down in Brazil might flap its wings and set off a tornado that could whisk this silly accusation away, never to be seen again.”

I connected the dots, and the full picture was looking rather grim for me. The absurdly high compatibility rating that Titan’s matchmaking service had given Takasaki. The way he’d been so curious to know how I felt about work as a concept. And now I’d shown up for what I expected to be a second date, only to be approached with a job offer by this strange man instead. A man who apparently worked for the Intelligence Base Administrative Bureau. A man whose job entailed the management of the very same network that originally connected me with Takasaki.

“You were trying to entrap me all along, weren’t you?”

The ice crackled in his rocks glass.

“This is a project that absolutely must succeed, no matter the cost. There’s no room for failure. And we need your help whether you like it or not. Even if we have to resort to unlawful means to get it,” he said, lifting his glass up off the table. “Oh, and by the way—once work actually begins, you’ll be given your own official position, answering directly to me. So allow me to begin your orientation, as your new supervisor. Do you know what we in the business world say to our colleagues when they accomplish a task with flying colors? Like, for example, me successfully bringing you on board exactly as I planned. What would you, as my subordinate, say to me in such a circumstance? Any idea, Naisho?”

He saw no need to use my academic title now that he was my superior and I his...employee. He raised his glass higher, as though preparing to make a toast, and cracked a smile for the first time since he arrived.

“We say, ‘Great work.’”

It was the most infuriating smile I’d ever seen.

11

I set down my mug of milk tea and gazed out the window at the vast green plains spread out beneath me. Unlike the isle of Honshu, which by now had been almost entirely developed, there was still plenty of untouched wilderness and sprawling flatlands up here in Hokkaido.

It had been two days now since Narain Srivastava forcibly recruited me, and I was currently on my way via air transit to the Kushiro Conurbation in the eastern part of Hokkaido. It was one of fifteen such conurbations on the island, spanning nearly 6,000 square kilometers and home to around 1.2 million people. It was also where I’d been asked to report for my first day on the job—the home of my very own “workplace.”

I could feel my stomach starting to churn all over again. Obviously, there was nothing I could do to fight back against Narain. Had I turned down his request, I would have been tried in court on false charges, found guilty, and sent to prison, just like he said. There, I would have been forced to undergo a program designed to rehabilitate felons—though I had no idea how that might work on the innocent. I was already sound in body and mind. What scared me more than anything, though, was that I simply didn’t know what life in prison was like. We’d made great strides in the modern era to ensure that prisoners’ basic human rights were never violated, but something told me that access to milk tea wasn’t one of said rights, and I wasn’t going to risk finding out. I had no choice but to submit to that unsavory man’s little scheme and accept the job, and thus become traditionally employed for the first time in my life. Well, look on the bright side—it can’t be worse than prison, I told myself as I filled out employment forms to make the flight go by quicker.

I scrutinized the document on my holofield once more. It was a Bureau Onboarding Agreement from Narain. It read less like an agreement and more like a sworn oath.

BUREAU ONBOARDING AGREEMENT

I hereby pledge my full intent to accept the position that has been offered to me by the Bureau. With this signed agreement, I acknowledge that I have accepted the Bureau’s job offer, and will abide by the following terms.

1. Following submission of this signed agreement, I will not rescind my intent to join the Bureau without good cause.

2. I agree to abide by all rules, requirements, and policies as stipulated by the Bureau in the Conditions of Employment.

3. I will submit all documents required by the Bureau in a timely manner.

4. I will never make false statements to the Bureau for any reason.

I hadn’t even begun to work yet, but I could already feel a headache coming on. What was even the point of a document like this? Did they really think they could compel honesty with a signature on a little agreement? I’d always thought the entire point of having a fully integrated AI network was to stop wasting people’s time with redundant, meaningless paperwork.

I turned the page and came to the section entitled “Conditions of Employment,” which was an even longer list of rules that I was not about to read under any circumstances. They couldn’t make me read or sign any of this; I dismissed the holofield and made the executive decision not to waste any more brain power on this bureaucratic nonsense. Just then, I heard the shwip of my seat belt tightening about me, and I looked out the window to see that we were making our descent into one of the local stations.

After a remarkably soft landing, I undid my seat belt, grabbed my luggage, and stepped out of my private compartment and off of the plane, where I was greeted by a large sign reading TESHIKAGA STATION. A moment later, the doors closed behind me; though it was a six-seater transit plane, I’d been the only one on board. I’d read that in the old days, when fuel was scarce, they used to cram hundreds of people onto a single massive aircraft, and there were only a small selection of “airports” one could actually fly to.

The plane immediately pivoted and took off again, flying back toward Tokyo. I spotted a car I could only assume was my ride driving up to the lot. I found it baffling that it hadn’t been right here waiting for me, considering courtesy cars were fully automatic and had access to the plane’s flight plan. Perhaps Titan didn’t work quite as efficiently out here in the country as it did back in the big city. Either way, the car rolled up in front of me—but when the back door opened, I scowled.

“Get in,” Narain said.

12

“I see you failed to submit those documents I sent you.”

“Why would I ever do something so obviously pointless?” I was grouchy, not even attempting to hide my unhappiness at his presence. He shot me a look, then exhaled loudly.

“Well, I suppose you don’t have to if you don’t want to,” he said. “It’s more of a formality than anything.”

This time, it was me who furrowed my brow and shot a look at him. So it really was pointless, then. Had he just been wasting my time as a joke?

“Don’t get it wrong. All I said was you don’t have to do it,” he added, reading my reaction. “I never said it was pointless.”

“Oh, really? Then what’s the point?”

“Imagine you had to work to survive, and I’m your prospective employer. I’ve got the power in this relationship, because you need this job to put food on the table. But I’ve also got a business to run, and profits to make, so I make you promise me that you won’t walk off the job or be insubordinate. Because I can. I’m the one offering the job. That’s what contracts are for—to make sure the employee always gets the short end of the stick. Been around for as long as the idea of work itself.”

“They sure loved their corruption back then, didn’t they?” I said, thoroughly disgusted. From the way he made it sound, work was little different from ancient slavery. They’d dressed it all up to look more presentable with modern laws and contracts and so forth, but the core idea remained the same.

“Anyway, I won’t sit here and insist that you sign the contract,” Narain said. “But you do at least need to be aware.”

“Aware of what?” I asked.

“That all work is predicated on antiquated customs, even now.”

“Oh, so did you sign such a contract?”

“Not saying that.”

I tilted my head to the side; I had officially lost the plot. I couldn’t possibly fathom what significance contracts could have if nobody ever signed one.

The car whizzed down the streets of metropolitan Teshikaga. With its rows upon rows of high-rises, it didn’t look all that different from Tokyo. While there was obviously plenty of undeveloped land up here compared to Honshu, the urban zone was fairly built up.

Land development was one of Titan’s most important tasks. All across the world, its vast network of automated heavy machinery worked ceaselessly to flatten hillsides and alter terrain in accordance with the grand long-term development plans the AI had envisioned. Which did of course account for things like balancing sustainability with the overall rate of societal expansion, but with more than half the earth’s land still completely untouched by humanity, the common understanding was that we wouldn’t reach the point of equilibrium for many generations to come. And so Titan’s heavy machinery geoengineered the very planet, reclaiming land by leveling mountains and filling in the seas—though always with a team of environmental protection phalanges in tow to help preserve the local ecosystems. It was thanks to this that we finally had access to more land than we could ever possibly want, and could have Titan develop it for us however we saw fit.

The city of Teshikaga in the Kushiro Conurbation was one of the very first areas in the entire world to experience geoengineering at Titan’s hands. The reasons for this were twofold.

Once out of downtown, we traveled through vast fields of lush greenery. We’d just crossed over the line where Titan had delimited the border of urban development. From there, the road sloped upward, and the car began a valiant ascent up the small mountain. Not ten minutes later, we arrived at the summit, and a panoramic view splayed itself across the tempered glass windows. It was a blue more brilliant than the sky, emerging from the very earth.

“Lake Mashu…” I whispered reverently, letting the name of that ethereal pool linger softly on my lips. Surrounded on all sides by a steep volcanic crater, its waters were supposedly the second clearest in all the world. With its surface spanning twenty square kilometers, and with a depth of over two hundred meters, it bore such spiritual significance to the Ainu people that they dubbed it the Lake of the Mountain Gods. I quickly reached into my bag and pulled out my camera. I rolled the window down and snapped a shot of the gorgeous scenery, capturing it forever in silver nitrate. With the inverted clouds reflected perfectly on the mirror-like surface of the still lakewater, I almost couldn’t believe it wasn’t CG. This view alone was worth the plane trip.

One of the two reasons Teshikaga was developed so early on was its close proximity to Lake Mashu, one of Japan’s premier natural wonders. Sites that drew a large number of tourists constantly going in and out were given higher priority for immediate development. What was once a small town of fewer than ten thousand at the start of the 21st century had now ballooned in size to a city of over four hundred thousand. Lake Mashu and the other natural wonders in its surrounding area were largely responsible for this population boom in the Kushiro Conurbation, as scenic sites that held mass appeal even overseas.

I peered out at the lake from the left-hand window as the car made its way along the rim of the crater. After a while, an even higher peak came into view, right along the outer rim. It was Mount Kamui overlooking both the lake as well as the smaller, adjacent explosion crater formed on the southeastern edge of the caldera by a volcanic eruption many thousands of years ago. Peeking out over the edge of this higher, smaller cone was the upper half of a massive spherical construct, its surface covered in a whirl of pure white and transparent plasma clouds. These two distinct surface factions were in a constant state of flux, always changing shape and shifting around each other to form peculiar patterns. Whenever a section of the sphere’s exterior turned transparent, I could see the complex internal structures within.

“Say hello to the Electrode,” said Narain. “It’s a hybrid power generator that harnesses solar, wind, and geothermal energy to create enough electricity for the entire facility.”

I looked up at it through the windowpane. A giant cylindrical tower stood erect from the center of the orb, like a stake piercing it right through the heart. And on that tower, a single massive numeral was written: 2.

This was the second reason Teshikaga was developed so quickly—because it had been chosen as the construction site for the Second Intelligence Base of the Titan AI network, one of only twelve such facilities in the entire world.

The car glided toward the base of the Electrode. At the foot of the mountain was a large pair of mechanical double doors with another large number two painted on them. The gate opened for us automatically, and the car proceeded through the tunnel and into the mountain’s interior.

13

“Each intelligence base houses the hardware necessary to keep the Titan network up and running.” Narain was giving me the basic rundown on my new workplace as we continued deeper into the long tunnel. “More precisely, the AIs housed at each of the twelve bases are not identical. Each has its own individual quirks and specialties.”

“Wait, so they’re not just interconnected pieces of one larger AI?” I asked.

“No, they’re collaborating parts of the larger AI network. The earliest instances of Titan, dating back to the construction of the First Intelligence Base, were fairly general-purpose in nature. But as more bases were constructed, and the AIs continued to collaborate and interface with one another, they eventually started doling out more specialized roles and functions to the newest members of the network. Or to put it another way: Titan decided for itself to decentralize and specialize as the network branched out and continued to evolve. So just as the earlier bases contain the most general-purpose AIs, the more recent bases house the most unique and specialized ones.”

This was the first I’d ever heard of any of this. I’d always thought that Titan was just Titan—simple as that. Though considering it was a system designed specifically to make people’s everyday lives less complicated, perhaps we had all been fed a less complicated version of Titan’s workings on purpose.

“So what about here?” I asked. “What’s this base’s AI like?”

“Pretty far on the general-purpose end of the spectrum,” said Narain.

Out the window, the tunnel’s light gray walls rushed past. Even intelligence bases were largely built from the same photopolymer used to create our towns and cities—though here, there were no colors or words or symbols adorning any of the smooth surfaces. While these things were necessary at least to a certain extent in places designed to be accessible to large numbers of people, here they really only had to worry about a handful of human employees. There was no need for signage in a tunnel used almost exclusively by service phalanges.

“By the way,” Narain went on, “in addition to being numbered one through twelve, each Titan AI has also been given a unique nickname.”

“What, like…Fido, or Buddy?” I said.

“Remind me to never come to you for pet name ideas.”

I was about to object, but then I remembered the two cats I had back at my parents’ house were named Calico and Tiny, so I kept my mouth shut. Though personally, I was of the opinion that names didn’t matter too much so long as you could distinguish one thing from another. If we’d only had one cat, I probably would have just called it Kitty.

“Well, not that the Bureau had the most creative naming sense either,” said Narain. “They just named each of the twelve Titan AIs after the pre-Olympian gods from which the word ‘Titan’ was originally derived.”

“Ah, Greek mythology. Of course”.

“Correct. The twelve children of the earth and heavens, or Gaia and Uranus. Oceanus, lord of the seas, Crius, who reigned over the stars, Hyperion, ruler of the skies, Theia, mistress of all that shines…”

“Which one is ours named after?”

“Coeus, master of intellect. One of the six males of the Titanic pantheon.”

So now not only were we ascribing names to the AIs, but genders as well? If they were so determined to select names with mythological significance, why not just appropriate a group of androgynous deities and make things less convoluted?

Finally, the car reached the end of the illuminated tunnel, which emptied out into a much larger and brighter space—a vast underground hangar large enough to house a sports stadium. Filling this open space was what appeared to be a little town. A large-scale apartment complex, streets lined with trees, a central courtyard that almost looked like a public park, even a few different little stores—it was like someone had liberated a single neighborhood out of an actual city and buried it underground.

“Anything you could ever need, you can find right here, so feel free to make ample use of the facilities,” Narain said. The unstated implication of his words was that this place had been specifically designed to ensure I never had a justifiable reason to leave my post and could just focus on work twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week—but it sure sounded a lot nicer the way he said it. I let out a heavy sigh. My work hadn’t even begun yet, and already I wanted to quit.

14

I sped down the facility’s pristine main corridor on my zoomboard. I hadn’t even had a chance to take a breather in the private living space they’d allocated to me before being immediately summoned to report to work. Admittedly, the line between home and work began to blur when it all took place in the same homogenous underground facility.

As I made my way forward, I pulled at the sleeves of my new outfit—the uniform they’d laid out for me in my quarters. It was a modest gray work jacket with a zipper running right down the middle—clearly designed with function over form in mind. The words SECOND INTELLIGENCE BASE were emblazoned on the chest, beneath which they were kind enough to include a little profile of the wearer (in this case, me), whether they liked it or not. (I didn’t.) I could only assume this was meant to serve a similar function to that little card listing Narain’s job title, but I had to say it felt pretty strange to me that they seemed so concerned with being able to easily tell people apart while also forcing them all to wear the same generic outfit. There were admittedly some schools that still mandated uniforms for their students, but forcing an adult to wear one just felt gross to me.

Another thing that struck me as strange was this corridor—it was eerily clean. Granted, most of the developed world was quite clean and sanitary thanks to cleaning phalanges, but this place was so spotless it almost looked simply unused. Just how many other people worked here, aside from me?

It was then that I noticed the hum of another zoomboard’s drive overlapping with mine. I turned around and saw a man zooming toward me. His bristly black hair was shorn close to his skull, and he looked to be Asian at a glance—but more than anything, he was an absolute mess. His uniform jacket was threadbare in spots and draped haphazardly over his torso. His eyelids drooped, a patchy and uneven beard grown purely out of laziness, and when he scratched his head, flakes of dandruff came drifting down like snow. This unkempt fellow was clearly in more of a rush to get to wherever he was going than I was, yet upon noticing me, he brought his zoomboard to an abrupt stop, so I stopped mine in turn.

“Whoa,” he muttered with half-lidded eyes. “What’s a chick doing here?”

I frowned at this, of course. These were the first words out of his mouth, and already he’d managed to lower my initial impression of him even further.

“Ah, yeah. You that new hire Narain was talkin’ about?” he asked.

“Yes, hi. Seika Naisho. Nice to meet you,” I said, affecting only the bare minimum politeness. The man flashed me a flippant grin. His was clearly the face of a man who didn’t know how to take anything seriously. He looked slightly older than me, but definitely younger than Narain.

“Name’s Lei Yougen,” he said. “But you can just call me Lei.”

“Chinese, I take it?”

“Yep. I’m an engineer. How ’bout you?”

“Japanese.”

“No, ya dink. I’m asking what you specialize in.”

“Oh. Psychology, I suppose.”

He cocked his head to the side, clearly puzzled by this. “Uh, and how exactly is that gonna help us out here?” he asked.