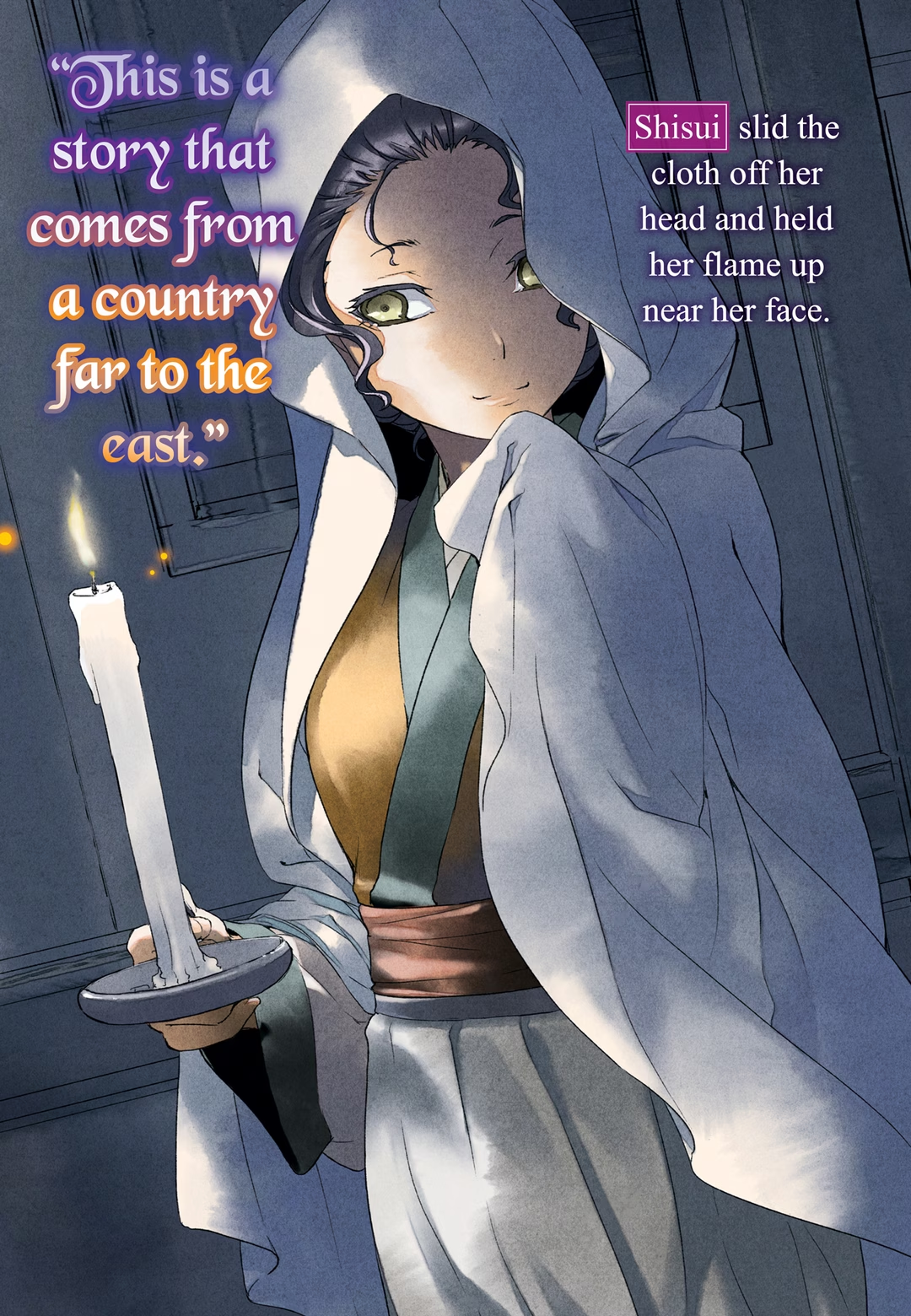

Prologue

Footsteps echoed down the hall: clack, clack. His own steps and the sound of his ball bouncing were almost all he could hear. Maybe the yawning of the woman minding him. His usual wet nurse was away, and he had a new attendant. The owner of the footsteps came closer; it was someone very old.

His minder rose to her feet, stepping forward protectively. She spoke deferentially to the old man, but he ignored her and continued his tottering advance, reaching out toward the boy. His white hair was disheveled, his eyes sunken, yet there were only a few wrinkles on his hand, showing that he was in fact younger than he first seemed.

A woman appeared in the room, perhaps summoned by the sound of his minder’s voice. It was his mother. She walked over at a brisk trot and stood between him and the interloper, staring the old man down.

The man let out a keening cry. He seemed to be scared of the boy’s mother. Frightened by the way the man’s body twisted, the boy threw his ball aside and clung to his minder. Still the old man tried to approach; he seemed to want to communicate something. His outstretched hand was in a fist; he was holding something tightly. The boy’s mother wielded a large fan, trying to keep the man back. She glared at him, with none of the gentle calm that was normally in her eyes, but instead a burning flame. The man was afraid of the flame, like a wild beast; he froze where he stood.

Soon, several more men came in from the hallway. They had only scraggly beards; the boy knew that they were called eunuchs. Finally, trailing after them appeared an old woman, looking supremely calm. She wore an elaborate ornamental hair stick that jangled like a bell, and at the sound the attendants organized themselves into a neat line. The boy’s minder and his mother both knelt. He thought this meant he should kneel too. The woman looked even older than the old man, but there was a bright light in her eyes, her gaze sharp enough to pierce. The boy felt himself shiver.

He thought he had seen the woman several times before. She was someone very important, that much he remembered; the young ladies-in-waiting had said nobody dared to go against her.

The old woman touched the old man. “Come, now. Back to your room.” Her voice was gentle, soothing, but the man took fright again, huddling close to the wall. He curled himself up and the boy could hear his teeth chattering, could tell his whole body was trembling. A sparkling object tumbled out of the man’s clasped hand, drawing the boy’s attention in spite of himself. It was a colorful stone, the hue hovering somewhere between vermillion and turmeric.

He had seen it somewhere before. What was it? The vibrant color struck some deep chord, but he simply couldn’t remember.

The old woman furrowed her brow and turned her back on the man, wholly ignoring everyone else in the room. Now the eunuchs stepped forward, coaxing and cajoling him until they could lead him back out of the residence.

The boy observed every minute of this, still clinging close to his minder. He had no idea what it was all about; the only thing he felt was fear.

Then there was his mother, though, kneeling beside him; she fixed a scorching glare on the retreating woman. Who must that old man and lady be, the boy wondered, to provoke such a scathing expression from his normally placid mother?

It would be sometime later before he learned. The man was his father, he was told, and the old woman his grandmother.

The man he had always believed was his father, he found out, was his own older brother.

It wasn’t yet the season when it was difficult to sleep, yet Jinshi awoke with his bedclothes soaked in sweat. He sat up in bed, feeling ill, and grabbed for the pitcher on the table, bringing it quickly to his lips. The water within had been mixed with a touch of fruit juice and honey, deeply refreshing to his dehydrated body.

He could see moonlight coming in through the window.

They said something bad always happened after a nightmare. Or was that just superstition? Jinshi took a breath and put the water back on the table. There were still hours before dawn. He ought to go back to sleep; if he didn’t, his minder Gaoshun would be upset with him.

Still, when one can’t sleep, one can’t sleep. There’s no use forcing the matter. And when one couldn’t sleep, the solution was to work the body until one was tired.

Jinshi took down an imitation sword sitting on one of his shelves. It was a training blade with a dull edge, built to be especially short and heavy. He made a wide one-handed sweep. He wished he could do this outside, but it would only be a headache for him if his guards realized what he was doing. They still might notice him here in his room, but at least if he stayed inside they might see fit to look the other way.

His room, though, was not particularly suited to sword practice. He had a solution: he decided to perform the routine on one foot. After going through the entire routine once, he would switch feet and hands and do it again. He did this several times, until it began to get light outside.

Jinshi lay spread-eagle on the ground to cool off his body, warmed by the exercise. Maybe he would have them prepare a bath for him, he thought, but then the face of a displeased palace woman floated through his mind. Her expression always revealed how she felt about him taking a bath first thing in the morning and then applying copious perfume. But he couldn’t go to work reeking of sweat. If he was going to play the part of the flawless eunuch, Jinshi, he had to at least smell decent.

He couldn’t just tell her that, though—that was what was so annoying. Yet neither, he thought, could he remain silent on the matter forever. She was a sharp one, that woman; surely she must suspect something by now. Perhaps she had already discerned the truth and was merely pretending not to have noticed. Well, it would certainly make the conversation easier...

Jinshi stood up, put the training sword back in its place, and then collapsed back on his bed. He didn’t bother to change his clothes. He still had a few minutes before his attendant Suiren came to wake him. He could at least grab a moment’s rest before that.

He just had to be careful he wasn’t taken by the urge to yawn at work, he told himself.

Chapter 1: Books

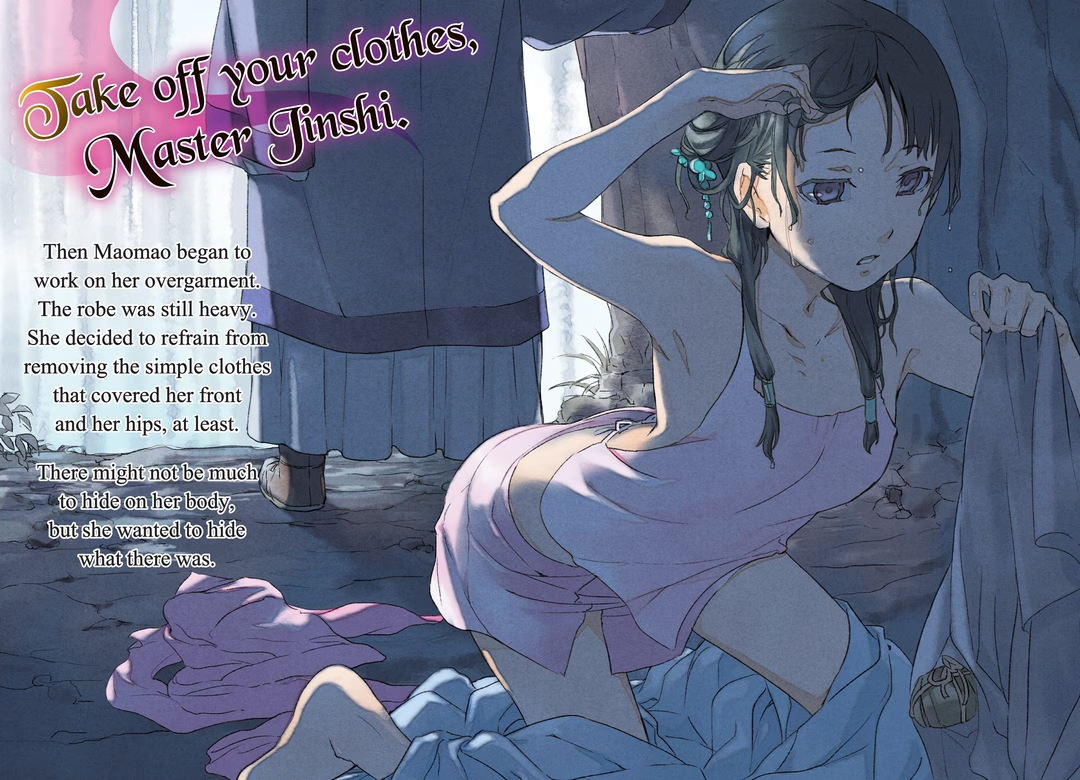

“What are you doing?” asked the thoroughly perplexed eunuch Jinshi, who looked as gorgeous as he always did. His attendant Gaoshun stood behind him.

“I should think that would be obvious,” Maomao said, wiping away sweat as she stood over a burning cookstove. Beside her was the quack doctor, fanning himself with his hand and obviously finding the heat rather unpleasant. While he worked assiduously—Maomao needed an assistant, what with her leg still healing—she couldn’t help thinking his movements were as flabby as he was. Maybe she was hoping for too much.

They were using the cookstove in the medical office to heat a very unusual stewpot. From the lid of the pot emerged a long tube that ran through some cool water, causing droplets to form at the end, where they were then collected in a small vessel. This distilling device was one of the discoveries of their recent cleaning spree. It pained Maomao to know that such a valuable object had sat unused in a storage room for so long. The air was full of the smell of flowers; a bevy of petals occupied the pot.

“We’re making perfume,” Maomao said. She had a wonderful source of petals in the roses she had cultivated for the garden party not long before.

“It’s certainly...aromatic.”

“The smell is fairly mild compared to wild roses. And we’ll thin it out further with oil and water.”

Over the generations, humans had fashioned roses to their liking, favoring beauty and richness of color at the expense of smell. That was simply the way of the world; you couldn’t ask for everything or you would get nothing.

Jinshi peered at the distiller interestedly. When the doctor, who had been industriously transporting firewood, realized the other man was there, he started brushing the dust and dirt off his clothes with all the self-consciousness of an adolescent girl. Smoothing his mustache and beard with his fingers, he asked, “To what do we owe the honor, sir?”

Jinshi’s face darkened; Maomao didn’t think the doctor meant anything by his question, but Jinshi seemed to resent the way it had been asked. “No one could fail to notice a smell this strong,” he replied, his lips forming into a slight pout. Nearby, Gaoshun’s brow furrowed.

He thinks Jinshi needs more gravitas, Maomao guessed. The quack doctor was oblivious enough that it didn’t much matter, but being important meant never looking less than distinguished.

Maomao got up from her chair, took some tea snacks from a shelf (she was well aware by now that the quack kept his most valuable treats on the highest one), and put them on the table. Jinshi sat down; Maomao picked up a mooncake, took a bite for good measure to show that it wasn’t dangerous, and then passed them to him.

“I suppose you’re doing this here because it would be more difficult at the Jade Pavilion,” Jinshi said.

“Yes, that’s part of it.” Maomao wiped the grease off her fingers and resumed her place by the cookstove. She changed the vessel at the end of the tube for a different one. After a moment, a greasy substance began to fill it: perfume oil. “The other part is this: perfume oil contains an ingredient that can potentially abort a pregnancy. As long as a woman doesn’t drink a concentrated dose of the stuff, she should be fine, but still...”

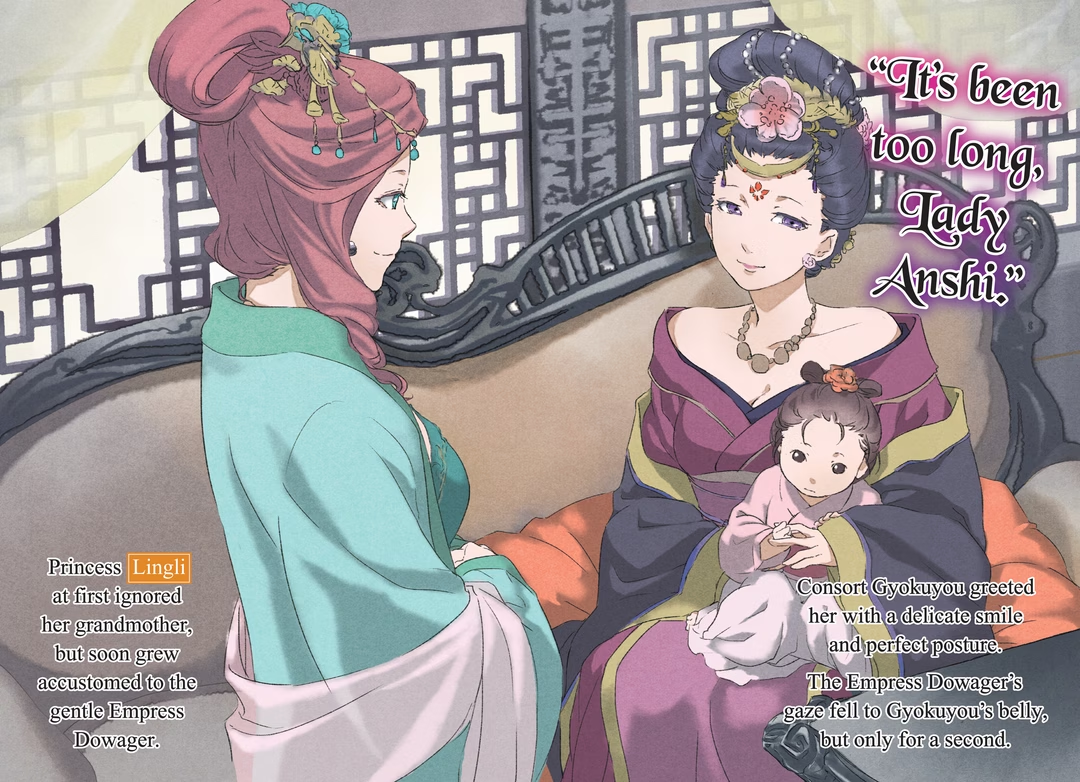

She glanced around, making sure the quack wasn’t too close. He was a very friendly person, but he had loose lips. It was too soon to let him know that the mistress of the Jade Pavilion, Consort Gyokuyou, was pregnant.

“In other words, there’s no special need to regulate the perfume oil being used in the rear palace, is that what you’re saying?”

“Yes, sir, I think it should be all right.” Making rules about every little detail would only make their lives harder. Besides, enforcement would be difficult in such a large place.

Jinshi looked at the other pot on the stove. It didn’t have a pleasant fragrance like the one full of rose petals; instead, breathing whatever was in this pot made his head spin. “What’s this one?” he asked.

“That’s alcohol,” Maomao said.

Through repeated distillation, it was possible to achieve a very high concentration of alcohol. Indeed, this stuff was strong enough to make Jinshi feel drunk just by taking a sniff. It wasn’t for drinking, but would be used for sterilization. The warm season was coming, when bad air could accumulate and cause physical harm. With a little princess at the Jade Pavilion, they would want everything to be as clean as possible. Maomao was even making a bit more than she needed so she could leave a supply here at the medical office, where it would see plenty of use.

“You can use it to clean things?” Jinshi asked.

“Yes; I hear that’s what they do in the west.” This was one of the little factoids she’d gleaned from hearing about her adoptive father’s experiences studying in the western lands. If there was anything at all that set her apart, Maomao thought, it was the knowledge she’d gotten from him.

“As I recall, the man who adopted you was—”

Before Jinshi could finish, though, they heard a great thump. Gaoshun poked his head outside to see what it was. Two eunuchs had arrived at the medical office with a massive box and had set it down just outside the door.

“What’s this about?” Gaoshun inquired of the doctor.

“Ah, the young lady requested it.”

Maomao glared at the quack to shut him up, but she was too late. Jinshi had already taken an interest in the delivery, beginning to unpack it. She wished he wouldn’t touch it without asking.

“Master Jinshi, the tea is ready. Please, have a seat and enjoy it,” she said.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“Just something from my home. Nothing of interest, I assure you.”

Unfortunately, Jinshi looked very intrigued indeed. I can’t believe this guy, Maomao thought. She—yes, even she—was a woman. She wished he would have the decency not to look at a moment like this. But instead she cast her eyes to the ground and said, “I-It’s full of underwear, sir.”

Jinshi promptly took his hand away, looking unsettled. That’s right, just leave it alone, Maomao thought at him without looking up, but reality is rarely so accommodating.

“Just how much underwear is in there that it took two grown men to carry it?” Gaoshun asked. Leave it to him to notice the most inconvenient details.

“You’re right!” Jinshi exclaimed, and thus the contents of Maomao’s delivery, which she would have been just as happy for him to remain oblivious to, were unveiled for all to see.

“Fastidiousness, that’s the problem with the rear palace,” Maomao said, her back straight and her face utterly serious.

The ladies who comprised the residents of the rear palace were a collection of innocent virgins who hoped they might one day become the Emperor’s bedmates. Admittedly, not everyone was like that, but such exceptions were a minority.

Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that His Majesty’s Imperial eye fell upon one of the virgins. Not only would she have the intimidation of being with the Emperor himself, she would be embarking upon completely unknown experiences with him.

“Imagine the consternation of the young woman who commits some novice blunder under those circumstances. I would argue they need to learn the basics ahead of time.”

“And that’s why you’ve acquired all...this?”

Jinshi was standing imperiously in front of Maomao, who sat in a formal posture on the ground. The situation felt oddly familiar.

The delivery sat open, a great deal of literature visible inside. What kind of literature? Well...you know. The kind Maomao had already been acquiring in some quantity to comfort a lonely Emperor when he found himself pining away at night. Consort Lihua was likewise an avid reader of such material. This time Maomao had decided to get more than usual, in hopes of finding new sales opportunities here and there—but the timing of their arrival had been truly terrible.

She’d had this batch delivered to the medical office so she could finally escape the gaze of the persnickety Hongniang, but look what it had gotten her. Maomao was by no means avaricious, but if she didn’t manage to earn a modicum of money, her old man back in the pleasure district might not have enough to eat. He was such a soft touch, her old man; she was sure the madam would badger him into working nonstop.

Jinshi was openly exasperated, but he also seemed to sense the truth of what Maomao was saying. When she added that this request came in part from His Majesty himself, Jinshi looked deeply conflicted, but recognized she was in the right.

Gaoshun, meanwhile, was flipping through one of the books with a studious expression. The entire scene was so surreal that Maomao found herself scowling at it in spite of herself.

“This is exceptionally beautifully made,” Gaoshun commented.

He’s admiring the craftsmanship? Maomao thought. She’d been entertaining the possibility that Gaoshun was the world’s most poker-faced lecher, but apparently that wasn’t what had attracted his interest.

“They use fine paper,” she said.

Books about the bedchamber were hot sellers; they were often sent with young women when they went to wife, and those who read such texts for personal interest were more than willing to spend the money on them. Such books typically consisted mostly of illustrations, so one didn’t have to be literate to enjoy them. And as much as they cost, the potential profits they might engender could be equally great.

“Are these printed?” Jinshi was likewise studying the illustrations, but considering what they were illustrations of, the moment was plainly comical. The quack doctor stole embarrassed little glances here and there.

“Not with wood blocks, but with metal plates, I’m given to understand.”

“That’s really something.”

It was a western technique. Maomao didn’t know much about how the books were made, but for Jinshi to say something admiring about them, they must be quite unusual.

“Since I finally got my hands on some high-quality materials, I thought it might be best to disseminate them more widely,” Maomao said.

“That’s a different issue,” Jinshi shot back. He continued to flip through the book, though, taking careful note of its contents. Maomao, not sure she wanted him looking too closely, inadvertently slipped back into her skeptical gaze. Perhaps Gaoshun noticed, for he nudged Jinshi gently.

“If it’s caught your interest, sir, why not keep one for yourself?” Maomao said.

“N-No! It hasn’t caught my anything!” Jinshi said, all but throwing the book down. Maomao picked it up and smoothed it out to make sure the pages wouldn’t crease. “No, indeed,” Jinshi said, more confidently this time. “But perhaps I can look the other way on this one occasion.” He suddenly sounded rather self-important—but then, he was important, so maybe that was inevitable.

“Are you certain, sir?” Maomao asked, a gleam beginning to enter her eyes.

“Yes, but I wish for you to inform me what shop is selling such things.”

Maomao’s expression promptly changed to one of barely concealed amusement. Gaoshun nudged Jinshi again.

“What? I just want to know more about this exquisite printing,” he said, sounding slightly flustered. This conversation was getting stranger by the minute.

“Certainly,” Maomao said, still looking amused but jotting down the name of the shop in a notebook.

“It’s the truth!”

“Of course, sir.”

She didn’t think Jinshi had to resort to illustrations; someone like him could surely see as much of the real thing as he wished. It wasn’t possible that paper was sometimes preferable to reality, was it? Maomao, her thoughts threatening to run away with her, pondered the possibilities as she tore out the page of the notebook and gave it to him. As she did so, she couldn’t help noticing the excellent quality of paper in the doctor’s notebook, just what one might expect.

Joking aside, Maomao suspected Jinshi might have it in mind to start up a new business venture. The real trick of politics was figuring out how to extract taxes from the populace without unduly upsetting them. One way was to increase people’s income, and the first step in doing so was to invest tax money.

Don’t know exactly how he plans to go about it, Maomao thought, but the important thing to do now was to pick up the scattered books. Jinshi was attracting his customary audience, and while it might have been interesting to discover just how they would look at the gorgeous eunuch if they knew what kind of reading material he was perusing, Maomao wasn’t a terrible enough person to give him away.

While Maomao was busy cleaning up, Gaoshun’s hand brushed the box in which the delivery had arrived.

“What’s wrong?” Maomao asked.

Gaoshun looked hesitant. “I was wondering whether any of them might require censorship...”

He was talking, of course, about the content of the materials. Several were rather, well, hard-core. His Majesty’s personal preference. And what a preference it was.

“I’m told that our most important reader found something lacking in the earlier material.”

“Absolutely not,” Gaoshun said. And after she’d wheedled the madam into handpicking the best stuff. She reluctantly handed him the most lurid of the material.

Some ten days or so later, Maomao was loafing around the laundry area.

“I wonder what’s buried down there,” Xiaolan said innocently, leaning against a wall with a laundry basket in her arms.

The weather was excellent today, so the laundry area was bustling. Eunuchs washed clothes as fast as water could be brought. The maids’ uniforms were laundered by being trodden underfoot in a harsh lye mixture, while the consorts’ clothing was worked by hand using a handmade soap.

“Search me,” Maomao said. She pulled out a baked treat wrapped in the skin of a bamboo shoot and handed it to Xiaolan, who took it with a grin.

The question about what was “buried down there” was, Maomao gathered, a line from a novel. Novels were all the rage in the rear palace these days.

“What do I seek beneath the bewitching blossoms?” Xiaolan inquired, her eyes sparkling. She was a country girl and couldn’t read; there must have been someone reading the story to her. “I wonfer whaf it could be,” she said around a mouthful of food. Her cheeks bulged like a squirrel’s.

“Maybe horse crap?” Maomao ventured, earning a snort from Xiaolan. The girl managed not to choke, but she glowered at Maomao, her eyes watering. Maomao brought some water from the water supply and helped Xiaolan drink it, rubbing her back.

“You shouldn’t eat so fast.”

“It was your fault!”

What Maomao had said wasn’t untrue, though. Growing good vegetables required more than just water. Feeble soil would bring forth feeble produce; that’s what fertilizer was for. Beautiful flowers were just the same: the more beautiful they were, the more potent the fertilizer must have been. But a young girl smitten with a romantic story probably didn’t want to have her attention drawn to such vulgar details. Maomao resolved to be more careful in the future.

It wasn’t long before their turn came to do their laundry.

The novels Xiaolan was so taken with were making the rounds of the rear palace, and the Jade Pavilion was no exception. When Maomao got back, in fact, she discovered three young women chatting and giggling over a rough-hewn book.

“Hi, Maomao,” said the calm, mild-mannered Guiyuan. The other two, Yinghua and Ailan, were too absorbed in the book to greet her. Guiyuan had the page between her fingers, and the women were tugging on her sleeve, urging her to hurry up and turn it. Maomao leaned down to look at the cover, which had an illustration of a tree with a profusion of blossoms and a figure standing beneath it. She surmised it was the same book Xiaolan had been talking about.

“You want to read it later, Maomao?” Guiyuan seemed to be a quick reader, quicker than the other two, and she had time for a little conversation.

“No, thanks. Why is everyone so excited about that book, anyway?” Maomao asked.

“It came from His Majesty. It’s great, believe it or not.”

His Majesty—so it had come from the Emperor himself. The surprising thing was that he knew about it at all; high society tended to look down on novels as not refined enough. They held that fact was more edifying than fiction.

“Apparently he gave them to all the consorts and told them to share them around when they were done reading them,” Guiyuan said, although she looked a tad disappointed that Consort Gyokuyou wasn’t the only one to receive this special gift.

“Well, well,” Maomao said, looking more closely at the cover. She realized she recognized the mark on it. It was the seal belonging to the bookstore she’d referred Jinshi to the other day.

Ahh, now it makes sense. She finally grasped why he had been so interested in her por—er, her reference materials. When Jinshi had seen the quality of the paper, he had realized it would be suitable for a gift from the Emperor. If the books had really been given to all the consorts, that meant at least a hundred had been printed. If they could make plates of the books, even more could be produced. Then, if they produced a popular edition on slightly less-expensive paper, they could realize even more profit. Maomao was starting to think she should have asked the printer for an intermediary’s fee.

She was sure Jinshi must have planted the idea in the Emperor’s head. I should’ve known he was planning something.

Fiction novels, easy to approach but unsophisticated, were being distributed to the consorts. Normally any gift from His Majesty would be cherished and treasured, but by giving books to all his ladies, each one would be less valuable. And anyway, the gift was nothing but pulp fiction. There would probably be a few disobedient consorts scandalized by the idea of even touching the thing.

On top of all this, there was the command to share the books with other people. Some of the consorts might hit on the idea of having their ladies-in-waiting read the book to them, instead of taking the trouble to read it themselves.

Hmmm...

The pieces were starting to come together; Maomao began to see what Jinshi was up to. The ladies-in-waiting who learned the story would share it with other women. Hence why even Xiaolan could quote from the book.

“Aw, are we done already?” Yinghua asked, looking as dejected as a dog who’d been denied a treat. The book was now closed, and Guiyuan and Ailan wore similar expressions. “More! I wanna read more!” Yinghua exclaimed with all the fervor of a deprived child. Amusements were few and far between in the rear palace, so that even a lone novel was a source of genuine excitement.

“According to Master Gaoshun, there’s a new book being printed. When it’s ready, he says we’ll get a copy,” Guiyuan said.

“Yeah, I know, but I can’t wait that long!”

Guiyuan frowned at Yinghua. Yinghua, for her part, had her cheeks puffed out like a blowfish.

Ailan, meanwhile, had the book in her hands and was looking at it intently.

“Is everything all right?” Maomao asked.

“About this book...” Ailan started.

Hongniang, the chief lady-in-waiting, was looking after Princess Lingli while the three young ladies took their break. When their break time was over, they would switch, and Hongniang would have a chance to relax.

“We’re the only ladies-in-waiting here, right? And Lady Gyokuyou was nice enough to say we could read this. Doesn’t it feel like kind of a waste if we’re the only ones who get to enjoy it?”

Maomao thought she understood what Ailan was getting at. When you find something interesting, you want to share it; that’s human nature. Maomao, for example, had once discovered a very rare snake she’d never seen before, and had gone around showing it to everyone she could find. (They had not been pleased.) It was probably this same impulse that motivated Ailan to want to let more people read the book. The women of the Jade Pavilion had some connections outside their own workplace. But Yinghua put a stop to that idea.

“Wait,” she said. “I don’t think we should show it to any other palace women. We have to be careful with it.”

“That’s right, they might lose it,” added Guiyuan.

“Yeah, I guess so,” Ailan said wistfully.

Hmm. Maomao reached for the book. What she was about to suggest might not normally be acceptable, but considering what she thought Jinshi had in mind, she decided it would be all right this time.

“What if you didn’t give them the actual book,” she said, “but made a copy for them?”

Ladies lower in the hierarchy might not have the means, but Ailan was an attendant to a high consort and should be able to procure the paper, brush, and other implements necessary to copy a text. And if she didn’t want to take the time or spend the money, well, she didn’t have to.

“What?” Ailan said, caught completely off guard by Maomao’s suggestion.

“I suppose replicating the illustrations would be difficult, but you have lovely handwriting, so I don’t think copying the text would be any problem for you.”

The producers of the book would no doubt have been better pleased if the women had bought another copy instead, but when that wasn’t feasible, something such as this was the only solution. Though it might be asking too much for Ailan to illustrate the book herself, she could provide a perfectly readable copy of the text, which was really all that was necessary.

“I see! That makes sense!” Ailan’s eyes began to shine with a new light.

“Oof! Are you really gonna do all that work?”

“Yinghua, don’t say that,” Guiyuan reproved her.

Maomao set the book carefully in front of Ailan and resolved to get back to work. Their break time was almost over, anyway, so they all needed to hustle or Hongniang would fall upon them like a lightning bolt.

It was all a very roundabout way for Jinshi to get what he wanted, Maomao thought. With books—of whatever kind—circulating more freely in the rear palace, at least a few people would learn to read.

Back when Maomao had been serving Jinshi directly, she’d had a few opportunities to see some of the paperwork he dealt with in his own work. He’d asked for her opinion on one project—purely out of curiosity, of course. He had wondered how the literacy rate among the women of the rear palace might be improved.

Maomao was getting firsthand experience of how well Jinshi’s plan was working. She was holding a twig in her hand, scratching the characters Xiaolan into the ground. Xiaolan herself watched intently, then tried to copy her.

Xiaolan always seemed like she was more interested in snacks than anything else in life; Maomao had been surprised when she’d first come to her and asked her to teach her to read and write. When Maomao asked why, Xiaolan said the woman who had been reading stories to her had stopped. The woman’s voice had finally given out after being endlessly petitioned by the illiterate palace women to read to them. She was a good-hearted woman, though, and had agreed to make copies of the book if the others would make the effort to learn to read it themselves.

So there was someone else out there thinking along the same lines as Ailan. It was an awfully generous offer, considering the price of paper.

Maomao had suggested that she could read to Xiaolan, but the other woman had shaken her head. “She was nice enough to write it out for me, so I can’t cheat like that.”

Maomao mussed Xiaolan’s hair fondly. She thought she was giving her a friendly pat, but she mostly succeeded in making it go every which way, earning herself an annoyed look from Xiaolan.

Thus, the time they usually devoted to gossiping was turned to learning to write. Xiaolan gripped her twig with a look of intense concentration. The character xiao, which consisted of just a few short strokes next to each other, still looked a bit like a pile of dead bugs to her, but it was simple enough and she could manage to recognize it. Lan, however, was a far more complicated character and was giving her a good deal of trouble.

Maomao wrote the character in the dirt again, nice and large. This time she broke it down by its three radicals to make it easier for Xiaolan to understand. On top, there were three simple strokes representing grass; beneath them, a character that by itself meant “gate,” and inside the gate was the character for “east.” Maomao started by having Xiaolan practice the pieces individually.

“I never knew my name was so hard...” Xiaolan received passing marks on her “grass” radical, barely, but her teacher insisted she redo the “gate” and “east” parts.

The fact was, Maomao wasn’t sure what the characters for Xiaolan’s name were. Xiaolan’s own parents probably hadn’t been literate. But she assumed it would be appropriate to use the most common characters for the name. When Maomao had been taught to read, she’d started with her own name. It was important, she was told, for helping you know where you came from—but then, she was often told she had all the charm of a stray cat.

“If you learn to write the characters, you’ll obviously end up learning to read them, but would you rather focus on just reading for now?” Maomao asked, but Xiaolan shook her head.

“If we’re going to take the time, I’d rather learn to write them. That can only help in the long run, right?”

That was true. The ability to read and write opened up many more job opportunities. Even in the rear palace, literate women were put to relevant work and treated better than the interchangeable laundry-hops. It was even said that an especially accomplished palace woman might find herself reassigned to administrative duties outside the rear palace.

“I’ll have to find work for myself after I leave here. I’d better learn while I have the chance.” So Xiaolan was trying to plan for the future, in her own way. She’d come to the rear palace about the same time as Maomao. Terms of service lasted two years, so she was already halfway through her contract. Given that she had been sold into service by her parents, it seemed unlikely she could expect to go back home when her time was up.

“I see. We may need to make the lessons a little more intense, then,” Maomao said, and then she started writing swiftly in the dust.

“Y-Yeah, thanks. So, uhh, what does this say?”

“It says: dong chong xia cao. Caterpillar fungus.”

“Um, okay. And this?”

“Mantuluo-hua. Thornapple.”

“And...this one?”

“Gegen. Kudzu root.”

“Um... Do these words actually come up a lot?”

Maomao didn’t say anything, just reluctantly rubbed away the vocabulary she’d written and replaced it with more ordinary terms.

Chapter 2: The Cat

Princess Lingli, a year and a half on from her birth, was proving quite precocious, a very healthy child indeed. Maomao wasn’t a big fan of children, but even she had to admit that the princess was endearing. It was certainly more pleasant taking care of her than looking after one of the girls who had been sold into the brothel. There’s no creature in the world so insufferable as a preteen girl.

The princess had graduated from holding on to things in order to get around to walking on her own, and recently to jogging short distances. Consort Gyokuyou watched her pound around with a touch of concern. “I wonder if this residence is starting to get a little small for her,” she said. The Jade Pavilion was hardly cramped, but it wasn’t healthy for a child to play inside all the time. There was a central garden as well, but soon it wouldn’t be enough to hold the princess’s interest.

“Perhaps it might be all right to take her for a little walk.” Gyokuyou was uncommonly open-minded. Most nobles felt that young ladies of prominent heritage should spend their days safely indoors, swaddled in the finest silks. Evidently, Consort Gyokuyou didn’t agree. “What do you think, Maomao?”

Maomao looked up and grunted softly, somewhat surprised to have the consort suddenly ask for her opinion. “In terms of her health, I think it would be wonderful if she had more chances to go outside.”

Maomao looked at Gyokuyou’s feet. They were well-built and perfectly large enough; they hadn’t been bound when she was young. In the arid western regions where she had been born and raised, Gyokuyou seemed to have received a somewhat more permissive upbringing than many of the other consorts.

Generally speaking, it was regarded as best to let a child’s mother set the tone for their rearing, but this particular child happened to be the daughter of the most important man in the nation and the apple of his eye. They couldn’t expect him to simply nod along and let Gyokuyou do whatever she wanted.

The consort, of course, understood this very well. “I’ll ask about it, then,” she said, running her fingers through Lingli’s hair where the child had fallen asleep on the couch.

Several days later, permission had been granted for the princess to go outside, accompanied by two eunuchs as guards. Maomao and Hongniang were to go with her. It was just a little walk, but the Emperor could be pretty protective. Then again, all of his children had died young so far, so maybe he had reason to be.

“I know you know a lot about flowers and animals, Maomao. Maybe you could teach her?” Gyokuyou said, patting the princess’s head. Her belly was already heavy, so she had to stay behind at the Jade Pavilion, just to be safe.

“Don’t give her ideas, Lady Gyokuyou. She’ll teach the princess the most positively awful things,” Hongniang insisted, but the consort acted surprised.

“Goodness, I should think her instruction might be helpful.” The hint of an elegant smile appeared on her face. “After all, one never knows where one might go in marriage in the future.”

I knew she was a shrewd one, Maomao thought. The princess might still be young, but given her place in life, in another ten years or so there was every chance she would be married into another family somewhere. If she was granted to some loyal subject, well and good, but it was distinctly possible she would go to live in some other country—somewhere she might not be entirely welcome. In such a situation, a working knowledge of drugs and poisons couldn’t go amiss.

Hongniang acceded with a sigh. Though obviously not thrilled, she understood the logic just as well as Maomao.

Gyokuyou waved to Princess Lingli as she left on her walk, and the princess waved back. Then she squealed, seeing the outside of the Jade Pavilion for the first time. She could only taste so much of the outside world from the pavilion courtyard. She still knew only a few words, and most of them didn’t make very much sense, but nonetheless she was clearly excited to see so many palace women, far more than there were in her house. Maomao had worried the child might be afraid and start crying, but far from it. She had her mother’s daring.

Lingli pattered along, exclaiming frequently. Sometimes she would point at something, and Maomao or Hongniang would tell her what it was called. It was hard to say how much she really understood, but she would burble “Mrm mrm” in response, so maybe some of the words made sense to her. The eunuch guards kept a respectful distance, not too close but never too far. Young children were a rare sight in the rear palace—indeed, Lingli was the only one under ten in the entire complex—and she naturally attracted the women’s attention. Some couldn’t suppress a smile to see a child for the first time in so long; others, realizing she was a princess, took a respectful step back; and still others simply looked at her with no particular expression at all. The young princess was oblivious to all of this, but as she grew up, she would come to understand the significance of those looks.

Hongniang, who was holding Lingli’s hand, had her work cut out for her as the princess flitted from one thing to the next, bursting with curiosity. The plan had been to walk to the cherry grove that lay west of the Jade Pavilion, pick some cherries, and then come home, but they seemed to keep finding detours and diversions. Finally they spotted the western gate, Hongniang openly relieved to have reached their destination.

They heard a high-pitched cry: “Rroww!” It sounded almost like an infant, so that Maomao and Hongniang briefly thought it was Lingli, but the princess was looking around for the source of the sound too. Suddenly she darted off. Hongniang scrambled after her as she peered between some storage buildings. “No, Princess, don’t!” Hongniang called.

At the same moment there came another cry: “Mew!” Before Lingli could disappear among the buildings, Maomao squeezed herself between the storehouses with a “I’ll go have a look.”

“Maomao!” Hongniang said.

“Meow meow!” Lingli squealed at the same time. Hongniang had no choice but to step back, while Maomao continued after their charge.

She saw something glimmer golden in the gloom. She reached out toward it, but it slipped between her feet and ran off.

“Meow!”

“Princess!” Hongniang said, holding Lingli back. A small, grimy ball of fur appeared from between the buildings. The furball took fright at the sudden sight of humans and tried to run. Its hair stood on end and its tail stuck up.

“Meow!” The princess pointed at the fuzzball, indicating she wanted them to catch it. Maomao had just extricated herself from between the storehouses, but she wasn’t in any position to jump on a small animal. It’s gonna get away, she thought, but at that moment someone appeared behind the ball of fur. The little creature was so focused on Maomao, Hongniang, and Lingli that the new arrival easily swept it up in her hands.

Their helper was another palace woman, someone Maomao didn’t recognize. “Is this yours?” she asked, sounding surprisingly girlish. Although she was tall, she had a young face; she might have been Maomao’s age, or perhaps younger. She wore the same uniform as Xiaolan and seemed a touch ditzy.

“Thank you,” Maomao said. The other woman held the filthy, shivering lump of fuzz out to her. Maomao took out a handkerchief and wrapped it around the animal. She could feel it shaking even through the cloth, and it cried “Mrow!” pleadingly. It had run only out of fear and had exhausted itself doing so; she could feel how limp it was.

“I’ll bet it’s hungry,” the woman said. “Maybe you can feed it. Anyway, see you!” Then she went on her way with a wave.

Whatever; Maomao had the furball, so she considered this a success. She took the animal over to the princess. Hongniang studied it. “Maomao, is that—?” She raised an eyebrow with a disapproving look. “Meow, meow!” the princess cooed, apparently meaning “Let me see!”

“It is indeed. A cat.”

The tiny kitten curled in her handkerchief was still shivering.

Princess Lingli was entranced by the tiny, unfamiliar life-form. She continually badgered Maomao to show it to her, crying “Meow, meow!” in imitation of the kitten’s mewling, but Maomao knew Hongniang would never let the princess touch the grimy little thing. They couldn’t simply leave it to its own devices, though, so they cut their walk short and went back to the Jade Pavilion.

Notwithstanding the princess’s attachment to the kitten, something so unsanitary couldn’t be allowed in the consort’s residence. Ultimately, they distracted the princess with her favorite snack while Maomao spirited the animal away to the medical office. It seemed like the obvious place, for without care, the creature was going to die.

Maomao was much perplexed, though. Yes, the warm season was when wild animals would be breeding, but that was a matter for the world outside the rear palace. Within its walls, there were hardly any pets to speak of. A small handful of the consorts had birds from other lands, but they kept them in cages, and there weren’t any dogs, cats, or anything else of the sort around. Special permission was required to keep a pet, and it was forbidden for male and female animals to be kept together; if and when they arrived, male animals were castrated just like male humans. It might sound harsh, but it was precisely to prevent any trouble should they escape. The rear palace couldn’t have animals breeding willy-nilly all over its vast grounds.

They had come to a compromise: Hongniang agreed that the cat could stay for the time being, but she said the higher-ups had to be informed.

“Oh, this is a surprise,” the quack doctor said. Calm as ever, he didn’t seem to be thinking very hard about why Maomao had a cat with her. He saw that it was shivering, though, which provoked a compassionate frown. The doctor set some water on to boil. When it was good and warm, he put it in a wine bottle, wrapped the bottle in a cloth, and placed it in the basket where they had put the kitten.

“Looks like you know just what to do.”

“Not the first cat I’ve taken in. I had the sweetest calico once.”

By sheer coincidence, the kitten also happened to be a calico. As they wiped away the filth on its fur with a damp rag, they saw the patches of reddish-brown and black fur. The kitten had its milk teeth, but it was terribly undernourished; Maomao could feel its rib cage under her fingers.

“You wouldn’t have any milk, would you?” she asked. Its mother’s milk would be best, but they could hardly go out searching for her now. It hadn’t looked to Maomao like there had been any other cats around when they’d found the kitten, anyway.

“Mmm, I think I can go get some,” the quack said and darted out of the office. As the palace physician, he had a fair amount of pull in the kitchen.

As Maomao continued to rub the milk-starved kitten with the rag, she picked fleas off it, tossing them in oil to kill them. She would have liked to simply dip the animal in some hot water to get rid of them all at once, but considering the kitten’s physical state, wiping it down was the most she could do.

A few minutes later, the doctor came trotting back with a stew pot. “They had goat’s milk, at least.” He held out the pot. Maomao dipped a finger into it and found it was exactly the right temperature. She made sure her fingertip was wet with milk, then brought it to the kitten’s mouth. The tiny animal began half-nibbling, half-lapping at her finger. She did this several times, the quack watching them both fondly.

“What a sweetie,” he said.

Maomao hated to take advantage of him just because he was acting like an especially soft touch, but she decided to ask him for one more favor. “Would it be possible for you to obtain some tripe?” Given the number of people in the rear palace, the kitchen must slaughter several animals every day. Sausage was occasionally served at mealtimes, so Maomao knew they didn’t simply throw the organs away.

“T-Tripe? Well, I suppose, but whatever for?”

The kitten was so weak that it seemed like it would be a while until it had recovered enough even to drink milk from a saucer. Feeding it one fingertip’s worth at a time, though, was time-consuming. Maomao had thought she might be able to appropriate some intestines to simulate a parent’s nipple.

When she explained this to the quack, he went rushing off again to the dining area. Truly, a generous-hearted man. In the meantime, Maomao continued to feed goat’s milk to the small cat, as much as it would drink.

Several days later, they had mostly managed to clean the kitten up and its fur was starting to regain some of its luster. Maomao had briefly worried whether the goat’s milk would sit well with it, but the kitten seemed to have taken it quite well.

Ordinarily, they would probably have had to toss the cat out of the rear palace immediately, but—for better or for worse—the night they found the animal, the Emperor had happened to visit the Jade Pavilion. When he heard his little princess incessantly exclaiming “Meow! Meow!” he couldn’t deny her the source of her pleasure. And who should be charged with the animal’s care but, of course, Maomao.

“Her name already means ‘cat.’ They’re the perfect match!” the Emperor had joked. Maomao hadn’t been quite sure whether she should laugh or not, but as Consort Gyokuyou chuckled, Maomao at least managed a polite smile. She figured eventually she would be able to foist the thing off on the doctor. (As if she hadn’t mostly done that already.)

The princess couldn’t yet enjoy the kitten’s company because it still had some fleas, and more importantly, because however small it might have been, it was still a wild animal. Maomao promised to share the kitten with Lingli when it got a little stronger.

When the kitten was recovered enough to tolerate it, Maomao dunked it in a washbasin and gave it a bath. It immediately looked substantially cleaner, but when she scrubbed it with some soap, the water turned gray. Its undercoat was still dirty. When Maomao suggested that the kitten’s soft, white fur would make an excellent writing brush, the doctor clutched the animal protectively, shaking his head. She’d meant it as a joke, but as two brand-new brushes appeared for her shortly thereafter, she decided she had come out ahead.

After the kitten had enough time drinking nourishing milk, they added minced chicken to its diet. They gave it a small box full of sand, where it promptly learned to do its business. It still had trouble doing number two without having its anus stimulated, though. The quack was kind enough to use a damp rag to help the kitten out.

Its teeth were still small, but meanwhile they clipped and filed its nails. Not an easy procedure on a kitten, but if it accidentally scratched someone or something, they would never hear the end of it. Seemed like a good idea at the time, anyway, Maomao thought, letting out a long sigh. Just then, someone arrived at the medical office.

“And how’s the little one doing?”

The source of the lighthearted quip was Jinshi. Gaoshun was with him as ever, and he was carrying some sort of bag.

“I think the princess should be able to see her soon,” Maomao replied. “The only problem is, I don’t have a plan yet for if the animal scratches her or tries to run away.”

“Oh, you’re always so caught up in details.”

Easy for him to say. He wasn’t the one who would suffer the consequences if anything went wrong.

Maomao glanced over toward the animal in question to discover Gaoshun had produced some dried fish from the bag and was waving it in front of the kitten. The customary furrow in his brow was gone, and he even appeared to be smiling. So he had a playful streak!

“Master Gaoshun, I think that might be a little hard for our kitten yet. Perhaps I could boil it?”

The quack already had a pot ready to go as if he had been waiting for this moment. You couldn’t count on him to do his own job, but he came through at times like this.

Jinshi snatched the cat up and stretched it out, examining its little belly. “Female?” he asked.

“Yes. No need to castrate it, fortunately.” The words were out of Maomao’s mouth before she realized that perhaps it wasn’t something to say so lightly in this company. “I’m sorry, sir,” she added.

“No, think nothing of it,” Jinshi replied, though she couldn’t quite read his expression. Still feeling apologetic, Maomao went in search of some kind of snack and came up with the last of the sausages they’d made from the leftover tripe. She’d packed them with meat and fragrant herbs and boiled them, not wanting anything to go to waste. Then she stopped for a second and thought about it.

“Something wrong?” Jinshi asked.

“No, sir.” Maomao put the sausage back on the shelf and picked out some rice crackers instead. The doctor, meanwhile, had a distant look on his face as he ate.

Jinshi amused himself by playing with the cat. He dangled the ornament that normally hung at his hip in front of the kitten—and pretended not to notice Gaoshun watching him with deep concern. He did, though, notice Maomao looking at him; he turned to her and held out the ornament as if to ask whether she wanted to play with the kitten too.

“I’m not much of a cat person,” she said.

“With your name?” He wasn’t the first person to say that.

“You seem to quite like her, Master Jinshi.”

“Not particularly.” He looked at Gaoshun, who was working with the doctor to boil the dried fish. Two middle-aged men putting themselves out for a kitten, Maomao thought.

“I’m not sure what’s supposed to be so good about them,” Jinshi went on. He was still eyeing the two men, who were gradually beginning to sound like they were purring themselves as they cooed over the kitten. Frankly, it was disgusting. His look seemed to say he could never be like them.

“I agree with you,” Maomao said, looking at the kitten. “But according to the cat lovers I know, the fact that you can never tell what they’re thinking is part of the appeal.”

“Goodness.”

“You look at them long enough, and you discover you can’t look away.”

“Hmm!”

“Then, gradually, you find yourself eager to pet the cat.”

“I see, I see.”

“It may annoy you that they act affectionate only when you have food, remaining aloof at all other times.”

“W-Well, yes.”

“But when you’re in that deep, all you can really do is forgive them their foibles.”

Finally, Jinshi didn’t respond at all.

Over time, Maomao was given to understand, one came to want to kiss the cat (even though it wouldn’t like it), then to play with its cute little toe beans, and finally to touch that fuzzy, wuzzy belly (even knowing a good scratching was the inevitable result). Maomao saw it as positively unsanitary to do such things with an animal that went around who knew where doing who knew what, but cat lovers apparently couldn’t help themselves. She looked at Jinshi, full of disdain for all this, to discover the kitten on his face.

“Whatever are you doing, Master Jinshi?” If he wanted to touch the cat’s fuzzy, wuzzy belly, fine, but Maomao glanced out the window, worried what might happen if someone were to see him that way.

“Oh, nothing,” Jinshi said. “But I feel like maybe I have more sympathy for those cat people than I did before.” He sounded as if he’d come to some sort of deep realization. (Let us prescind from the question of exactly what he had realized.)

“I see. Well, it appears the fish is ready.”

“Er, yes, of course.” Realizing that Gaoshun and the doctor were looking in his direction, Jinshi quickly put the cat down.

“What were you doing, sir?” Gaoshun asked, his tone polite but his gaze sincerely jealous.

Ultimately, even Jinshi was at a loss as to where exactly the kitten had come from. Plenty of wagons came and went in the rear palace, though, loaded with provisions. The simplest inference was that the kitten had wandered in after one of them, lured by the scent of food, and had gone unnoticed until the princess found her.

Not long after, the kitten was awarded an official court rank by the Emperor, being granted the illustrious-sounding title Admonisher of Thieves. All that really meant was that she would help keep the medical office free of mice. The Emperor certainly had a soft spot for his daughter.

The cat was given a name that meant “furry.” It stuck in Maomao’s craw for one simple reason: this name, too, was pronounced “maomao.”

Chapter 3: The Caravan

The season was turning, bringing an unpleasant heat and humidity. Maomao reflected on how quickly time passed as she gathered up fragrant herbs to use to ward off the bugs.

“I think it’s time to change the wardrobe over,” Hongniang, Consort Gyokuyou’s chief lady-in-waiting, said, and if she thought it was time, then it was time. Thus the ladies-in-waiting found themselves laboring away among the clothing.

“So many dowdy old fashions!” Yinghua huffed, standing in front of a dresser. She, Maomao, and Ailan were handling this job while Guiyuan looked after the young princess. “Ailan, grab that thing on the topmost shelf for me!” Yinghua instructed, craning her neck to look up at the shelf. Ailan was the tallest of them, a fact she was self-conscious about but which was quite convenient for reaching things in high places. After she had dragged a trunk down from the top of the shelf, the (rather shorter) Maomao and Yinghua inspected the contents. They sorted the clothing into different categories and put them on poles to air out in the shade.

“Hmm. I guess this one wouldn’t be too embarrassing,” Yinghua said. She was sorting the clothes into those in which one could still be caught dead and those in which one could not. To Maomao, all the outfits looked equally sumptuous, but Yinghua was accustomed to the finer things and proved more discriminating. “This sort of thing used to be really popular once. But it’s better to avoid fads. Once they go, you’re left with stuff you can’t use.”

Maomao took the outfits deemed no longer viable and stuffed them back into the chest, then trundled into the hallway with it. These garments may have been old or outdated, but they had still belonged to one of the upper consorts. They were made of the finest material, and would be reworked or repaired and then gifted to other people. Not to the ladies-in-waiting of the Jade Pavilion personally, but rather to their families. Ladies-in-waiting sometimes received hair sticks or other accessories, but clothing like this was not something one could get away with parading around the rear palace in. The craftsmen would rework the outfits, and in their new forms they would be distributed in Gyokuyou’s hometown.

Pulling down another box, Ailan said, “You know, I heard new ladies-in-waiting will be coming before long,” as if the thought had just occurred to her. “With Lady Gyokuyou pregnant, we’ll need more hands around here, but it would attract attention if we were the only place to get new women. So instead they’re going to give all the consorts a chance to expand their retinues.”

Yinghua’s mouth hung open slightly at that. “What, all of a sudden? I mean, I’m happy to hear that, but...”

“They found a good reason,” Ailan said. “Think about it. When one consort shows up with more than fifty attendants, how are the other women supposed to feel?”

“Yeah, I see what you mean,” Yinghua said, her face darkening briefly.

Maomao, too, understood what Ailan was talking about. Or rather, whom: Consort Loulan, who had entered the rear palace with tremendous fanfare. For the Emperor’s favorite consort, by contrast, to have a measly five women simply didn’t look good.

“Did she even try to make do with fewer women?” said Yinghua.

“Watch it, Yinghua, or you’ll get another taste of Hongniang’s iron hammer,” Ailan responded. Yinghua promptly clapped her hands over her mouth. Maomao, meanwhile, concentrated single-mindedly on putting the unwanted clothes in chests and carrying them out. In this way they carried on, chatting and working, until they had discarded almost half the summer clothes.

“We did get rid of a lot,” Maomao said, puzzled, “but how will we manage now?”

“Not to worry,” Ailan said with a smile. “We’ve already commissioned a few new sets of clothes from the craftsman.”

“And a caravan will be coming soon. We can buy more then,” Yinghua added. Ailan gave her a reproachful look for stealing her thunder.

“A caravan?” Maomao said.

“Yeah, that’s right,” Yinghua replied, brushing her hand along one outfit to check the feel of the silk. “It’s supposed to be even bigger than usual this time.” The excitement was evident in her voice. Perhaps the thought of it was what made her hand stop moving.

Caravans had once been groups of merchants who crossed the desert together, but the word had come to refer to any traveling sellers who visited, willing to engage in trade. Sometimes they did bring unusual items from strange lands, so the word wasn’t entirely inaccurate, but still it didn’t quite feel right.

The last caravan had visited during the time when Maomao had been effectively exiled from the rear palace, and the time before that, she had been a mere maid, unable to involve herself with such festivities. She had dealt with merchants in the pleasure district, so they didn’t hold any particular fascination for her, but the idea was understandably exciting in the rear palace, where distractions were few and far between.

“You should go have a look, Maomao. We’ll make sure you have some time in your schedule. Lady Gyokuyou usually gives us a little pocket money for things like this.” Yinghua grinned.

It happened just as the smile was crossing her face: Maomao and Ailan froze. Yinghua looked at them, confused, and they both pointed behind her.

Yinghua turned around slowly to find Hongniang hovering over her like a storm cloud. The chief lady-in-waiting wore a tight, crooked smile. Yinghua almost choked, but managed a feeble grin.

“I hear a lot of talking, but I don’t see a lot of sorting,” Hongniang said.

“Er— Wh-What?!”

Maomao and Ailan, for their part, promptly set about folding clothes. Yinghua’s mouth opened in an expression of betrayal.

I do want that pocket change, Maomao thought.

The incident, allegedly, cost Yinghua a bit of her spending money.

The rear palace was a big place, bigger than some towns. The women who worked there existed purely to serve the consorts, to keep up the buildings, and to hope for the vanishingly small chance that the Emperor might choose them for a bedmate. The unique situation bred rhythms and rituals of daily life that were likewise different from what one would find in an average city. As the roles of the palace women were broken down into cleaning, laundry, and cooking, it might be best to think of the place not as a city unto itself, but like a single giant household in which they all lived.

Yet in this whole huge place, it was impossible to find one particular thing that might have been expected. What was it? A shop of any kind.

“It looks like so much fun!”

Maomao met Xiaolan’s remark with a question. “You think so?” Xiaolan still seemed like a girl in some ways.

Palace women walked gaily among the tents set up in the plaza. The tents were packed close together, and, with nearly two thousand women serving in the rear palace, there was no room for the lower-ranking maids to squeeze in for a look. Unable to even admire the merchandise, the most they could do was to live vicariously by watching the other ladies admire it.

Maomao and Xiaolan were leaning against the railing of the room where the maids slept. Since the consorts and their ladies-in-waiting were all out having fun today, the minions had virtually nothing to occupy their time.

“Lucky them... I wish I could get some new clothes,” Xiaolan sighed, resting her chin on the railing.

“But you don’t have anywhere to wear them.”

“I know that. But I still want them!”

The lowest ranking of the palace women were generally only given work uniforms (three in the summer, two in the winter) and new outfits were provided only when an old one had worn out. Other necessaries, including hairbands and underwear, were likewise provided. Meals were served in the dining hall each day.

The families of the better-bred palace women might send gifts along with their letters, while the ladies-in-waiting of a consort might be given clothing or accessories by their mistress, not to mention snacks. Gyokuyou, for example, had granted Ailan paper on which to make her copies of the book.

With no shops around, none of these things were easy to come by. For Xiaolan, who had no powerful backer—no backer of any kind, in fact—chances to acquire new personal possessions were rare, and when they came, they went, well, like this. Only after the other ladies had been through the wares would she have a chance to pick through the leftovers for whatever she could afford with the paltry savings in her purse.

It was a strange feeling to see these shops all lined up here in the rear palace. The excitement in the air was palpable.

And only our quack to serve the whole lot, Maomao thought.

One might assume that any illness in a place this large would spread like wildfire, but in practice that wasn’t true. Sanitation in the rear palace was excellent. The palace women spent much of their time cleaning, and waste was dealt with efficiently. When enough of it had built up, it was flushed into the sewers, whence it went, not to the moat, but out to a great river. The moat was thus kept free of filth and stench.

The former emperor had utilized this site because there was already an existing sewer here, a technology that had apparently come from the west. Talk had it that the rear palace had once been an actual city, refashioned to serve its current purpose. Both the walls and moat had belonged to that city, so that despite its size, building the rear palace had actually been fairly economical. It was perhaps not surprising to hear that the prime mover behind the project had been the haughty but effective empress regnant.

Such sanitation measures alone went a long way in preventing the outbreak of illness, although if anyone did get especially sick, she was sent back home to her family. So the little world of the rear palace went round, with or without a quack for a doctor.

“Maomao, I think I can get a little time off on the last day,” Xiaolan said. Her eyes were sparkling—apparently this was an invitation to check out the shopping with her. Maomao had to admit she was pleased to be asked. She answered Xiaolan with a pat on the head.

When she got back to the Jade Pavilion, Maomao was greeted by the sight of some tired but satisfied ladies-in-waiting. While she had been out slacking—er, “having virtually nothing to do”—some merchants had come to the pavilion. The highest-ranking ladies of the rear palace didn’t have to trouble themselves to go out to the shops; the shops came to them.

The merchants were all women—for how else were they to be admitted to the rear palace? Nonetheless, there were more eunuch bodyguards than usual around, just in case anything should happen. They were familiar men, though, and the girls were sipping some tea, the pavilion’s domestic atmosphere undisturbed by the presence of the additional guards.

“His Majesty said Lady Gyokuyou could choose anything she liked!” Yinghua sounded as pleased as if she herself had been the one to receive this dispensation. She’d been terribly disappointed to have her spending money cut in half, but she seemed to have bounced back.

On the table was a stunning jade necklace the same color as Gyokuyou’s eyes. There was also quartz glass and an accessory box inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Princess Lingli was thoroughly satisfied with a pretty silk ball she’d gotten, and in addition to clothes for the consort, a tiny robe for Lingli hung on the wall.

“Perhaps we’ve had a little too much excitement,” Gyokuyou said with a touch of concern.

“If anything, ma’am, I think you could have stood to buy more,” her chief lady-in-waiting, Hongniang, said somewhat emphatically. “I’m sure the other ladies all did.”

Hongniang chose a restrained way of expressing herself, but Maomao could easily imagine what she meant. Lihua’s ladies at the Crystal Pavilion, all talk and no work, had no doubt gorged themselves on shopping. Consort Lihua had plenty to spend, and presumably plenty was indeed spent.

Over at the Diamond Pavilion, Consort Lishu’s ladies-in-waiting had, one might guess, goaded their lady into purchasing things they wanted. The best one could hope for was that they hadn’t outright embezzled anything.

As for the Garnet Pavilion...well, Consort Loulan’s penchant for conspicuous clothing consumption spoke for itself.

Consort Gyokuyou, who, by contrast, had purchased hardly enough to fill a single room, seemed downright frugal to Maomao, especially for someone with the Emperor’s personal affection.

The consorts each drew a salary commensurate with their “jobs,” but they were also reimbursed for clothing and accessories, which were considered necessary expenses. The upper, middle, and lower consorts came to almost a hundred people altogether, and Maomao found herself wondering if the national treasury was going to hold out at this rate. That was something she didn’t need to worry about, though.

“In any case, others will come tomorrow, so I’m going to put away today’s purchases.” Hongniang started pulling outfits down off the wall, handing them off to Maomao. Each was richly colored and pleasant to the touch.

It was then that Maomao noticed these clothes were of a slightly different make than the ones Gyokuyou normally preferred. Hm? The consort usually liked to pair a sleeveless dress with a long skirt and then wear an overgarment with wide sleeves on top of it, but these dresses all had proper sleeves, accompanied by skirts that were to be tied with a sash just under the chest.

Maomao had a good guess at the reason. Consort Gyokuyou would shortly be finding sashes difficult to tie across her midriff.

“Was this the only type of thing they had?” Maomao asked.

“What?” Hongniang replied. “The merchants swore they were all the rage.”

So these were all they had. The ladies-in-waiting looked at each other questioningly. The women of the Jade Pavilion had done their shopping with only thoughts of Gyokuyou in their minds. But one would normally have expected a wider selection. And if one followed that fact to the assumption the merchants had been making...

No, Maomao must have been overthinking it.

At least, I hope I am.

Because if they had deliberately brought only this type of clothing to Consort Gyokuyou, it might suggest they had been trying to sound her out.

“I think tomorrow, you should ask them if they don’t have some outfits with lower sashes,” Maomao said. She thought perhaps it wasn’t her place, but Gyokuyou and Hongniang both seemed to take her meaning. The other three ladies-in-waiting looked at each other again, but Maomao’s insinuation had clearly gone over their heads.

“That’s a good idea. We should get a little more variety,” Gyokuyou said, setting some clothes on top of a box. Perhaps it was her imagination—but Maomao thought she saw a keen light flash through the lady’s eyes.

The caravan would stay for five days, during which the ladies of the rear palace would have an unaccustomed chance to enjoy some shopping. The highest-ranking consorts had no need to go out to the shops, so it was first the middle- and lower-ranking consorts and their ladies-in-waiting who circulated among the merchant tents, followed by the women in administrative positions, each whittling down the selection further as they bought whatever caught their eye. Only on the last day did the women of the lowest ranks have an opportunity to sift through whatever was left. The fact that even that seemed to be an exciting prospect spoke to how few diversions there were around here.

This caravan had come across the desert and carried many unusual wares from exotic lands. It must have passed through Gyokuyou’s homeland as well, for the women of the Jade Pavilion looked noticeably homesick as they studied the handicrafts.

Maomao was far more interested in any medicines or drugs that might be available, but such were understandably barred from being brought directly into the rear palace; tea leaves and spices, sold almost as an afterthought, were as close as the merchants came.

On the final day, Maomao, with a bit of spending money from Consort Gyokuyou, went to the market with Xiaolan just as she had promised.

“Wow, I can’t believe it!” Xiaolan hardly had a coin to her name and couldn’t afford anything on display, but that didn’t stop her eyes from sparkling at an array of western glasswork. Maomao found Xiaolan’s lack of affectation charming.

“This one, please.” Maomao picked out an especially attractive hairband and gently tied it in Xiaolan’s hair. The deep, peach-pink color suited her energy perfectly. It only took Xiaolan a second to notice something had happened, and then she was almost knocking Maomao over hugging her. Maomao wondered if this was what it would be like to have a little sister.

“You aren’t going to buy any clothes, Maomao?” Xiaolan asked.

“Don’t need any.”

Partly, she didn’t want to make a show of buying things in front of Xiaolan—but more importantly, she really wasn’t interested in clothes. She was far more attracted to the tea and spices. Xiaolan, almost giddy over her new hairband, was more than happy to accompany Maomao to the shops that most interested her. She had a gigantic smile on her face the entire time. Apparently it was just that much fun for her to window-shop at these crude carts-turned-market-stalls.

Maomao was determined to buy some of the tea and spices. The ladies of the Jade Pavilion had taken it in turns to come to the market over the final three days of the caravan’s visit, and Maomao had said she was content to go on the last day. This was the reason.

Last day means discounts.

Maomao wasn’t interested in gems, trendy clothing, or any of that stuff. The goods she was after were of small consequence to everyone else, so she was sure there would be plenty left over. Besides, this was the rear palace—a special place. A bit of good-natured ripping-off was to be expected.

If they think they’re going to take me for a ride, though...

Maomao’s wiles were sharp. She’d spent most of her life watching the old madam do business, after all.

She stopped at one of the shops selling tea. A quartz goldfish bowl was filled with pretty little buds tied into balls. Jasmine tea. When steeped in hot water, the buds would open, as pleasant to see as they were to smell as the tea released its lovely aroma. Sadly, it had mostly been bought up; there were only three buds left.

“I’ll take this,” Maomao said.

But at the exact same moment, another voice said, “This one, please!” Maomao looked over to discover someone pointing at the same bowl. It was a palace woman about half a head taller than Maomao, although in spite of her height she still looked and sounded quite young. The contrast left Maomao blinking. She couldn’t shake the sense that she’d seen the girl somewhere before.

The other girl looked almost as confused as Maomao—then she exclaimed, “Oh!” her eyes lighting up.

“How’s your kitty cat?” she asked.

That jogged Maomao’s memory. This was the girl who had helped catch the kitten since dubbed Admonisher of Thieves. Maomao still didn’t know her name.

“She’s well. She lives at the medical office for the time being.”

The other girl grinned widely. She seemed to have a rich range of expressions, all highly communicative.

“Oh! Shisui! You were able to get time off?” Xiaolan said, bouncing into the conversation between the two of them. These two must have already known each other. Come to think of it, Shisui was wearing the same uniform as Xiaolan, that of the shangfu, or Wardrobe Service. She must have gone to the laundry area pretty often; it was only through happenstance that Maomao hadn’t run into her before.

“Yeah, they owe me at least this much!”

“You’ve got that right,” Xiaolan said. It was an innocent, friendly conversation.

Maomao noticed the tea-seller looking at them. She went ahead and bought all three of the remaining bulbs of jasmine tea and asked for them to be packed separately. The woman wasn’t thrilled about that, but when Maomao asked for one of the other leftover teas as well, she came around.

Then Maomao distributed the packages, one to Xiaolan and one to Shisui, keeping the last for herself. “Maybe we should take our chat somewhere else so we don’t get in the way,” she suggested, and pointed toward the medical building.

At the medical office, the quack doctor was gazing out at the marketplace enviously. As ever, he seemed to have a lot of time on his hands. The nature of his work kept him from leaving his office, even if hardly anyone ever showed up there. It must have been rough on him. He passed the time by helping the kitten groom herself. He was a very personable man, though, and when visitors did come, he bent over backwards to be hospitable to them.

“Gracious, young lady, I had no idea you had friends.” Not exactly a tactful thing to say, but then again, not untrue either.

Xiaolan entered the doctor’s office only with some trepidation, but her eyes lit up when she heard the cat say, “Meeoww.” Shisui likewise had a gleam in her eye.

“Aww, she’s adorable,” Shisui said. “What’s her name?”

There was a long beat. Finally Maomao replied, “Admonisher of Thieves.”

“Huh? What kind of weird name is that?”

“Just call her ‘the kitten,’ then.”

Yes, the kitten—that was plenty. Calling her “Maomao” was far weirder than the name the Emperor had given her.

Xiaolan and Shisui rarely visited the medical office; for one thing, they were normally too busy with work. Today, though, there was a festival atmosphere and everyone was having a good time. As a precaution, the storehouse containing the most important medicines had been locked up. True, it was arguably problematic that Maomao, who wasn’t technically on the staff, knew where the key was, but if she told anyone, they would only hide it from her, and she didn’t want that.

Maomao heated water while the quack prepared treats. She decided to use a quartz vessel instead of a teapot today. It was really for making medicine, not drinks, but when you had a high-quality tea like jasmine on hand, ceramic seemed like a waste. She used tepid water to warm the chilly vessel, then emptied it before placing a round bulb inside and pouring near-boiling water over it.

“Oh, wow!” The girlish cry came from Xiaolan, who was impressed by the potent aroma that drifted from the opening bulb. “Maomao, is this that stuff you bought earlier?”

Maomao nodded. Shisui, for her part, was conspicuous by her silence; maybe she’d seen jasmine tea before.

“You don’t want the water to be boiling, just relatively warm,” Maomao said. “Not that I have many chances to make it.” The tea leaves would probably keep for a little while if necessary.

The doctor appeared, solicitously offering rice crackers and mooncakes. The cakes were a bit large, so he cut them into pieces with a simple cleaver. Xiaolan’s eyes were already shining as she tried to judge which slice was the biggest. Only moments ago, she’d seemed unsure whether it was even acceptable for her to come into the doctor’s office. Now she was already chatting amiably with the quack. Maybe it was her youth that made her so adaptable. Shisui was also talking comfortably with him. The quack was clearly quite pleased. Many of the women in the rear palace treated men like him rather coolly because he was a eunuch, so meeting someone like Xiaolan must have been a relief.

“I do feel I should remind you young ladies that this isn’t a playhouse. This is just for this one time, okay?” He repeated himself on this point several times; it seemed to be his roundabout way of telling them that, in fact, they were quite welcome to come again (he could hardly say it in so many words).

“Is it like this every time? It’s like one giant party out there,” Shisui said, taking a bite of mooncake. It reminded Maomao that the other woman was the newest palace woman among them. Consort Loulan’s arrival had brought a great many of them into the rear palace. Shisui had probably been there for less than six months.

“Kind of. It seems to be going on longer than usual, though.” Xiaolan, the kitten on her knees, stuffed mooncake into her mouth. The kitten was getting a little too interested in her crumbs, so Maomao snatched her up and gave her some fish.

“Ahem, yes,” the doctor said, clearing his throat importantly and brushing some crumbs from his loach-like mustache. “A special embassy from another land will be visiting us soon, you see.”

Is he supposed to be telling us that? Maomao wondered as she sipped her tea. She’d been eager to get her hands on some hot water, but she was starting to think it might have been a mistake to bring the other two girls to the medical office.