Prologue

Mother was smiling brightly.

That meant she should smile too. She’d learned that much.

Mother was angry at Father.

That meant she should frown like Mother was doing. She’d learned that much.

Mother was disciplining one of the ladies-in-waiting.

That meant she should simply stand by and not do anything. She knew that.

Then Mother was looking at her, watching her very, very closely, and there was nothing she could do but rise to the challenge. Laugh when her mother laughed, grieve when she grieved.

Then Mother wouldn’t be angry. A smile would come over her face, and she would grow no uglier.

When she was about five years old, rouge was applied to her lips; by the time she was ten, face-whitening powder was put on her cheeks. Her eyebrows were plucked out and false ones drawn on, and then she felt like she was wearing a mask. It was as if there were invisible strings connected to her arms and legs, and Mother was pulling them. She was hemmed in on every side.

She could accept that. She was perfectly willing to be a puppet all her life.

But that was a mistake.

It didn’t matter if she wore a mask, if she made herself a puppet: Mother kept getting uglier and uglier. She discovered it was impossible to stop it.

Ah: it had all been for nothing.

But by the time she realized that, it was too late. Too late to do anything at all.

Chapter 1: The Bath

“I wonder if there’s anywhere I can get a decent job,” Xiaolan said as she sorted the laundry in the basket. They were in the usual laundry area, and one of the eunuchs had given her a load of dry clothes. “Say, Maomao, you wouldn’t happen to have any connections, would you?”

Xiaolan was into the last six months of her contract. Normally it was around this time that the families of palace women found potential marriages for them, or else the women found matches for themselves. Alternatively, a higher-ranking palace woman or consort who particularly liked them might ask for them to be kept on at the rear palace.

“Connections, huh?” Maomao said. Sure, she had connections. Such as they were. The Verdigris House was always looking for hardworking, attractive young women. Especially ones as good-natured as Xiaolan.

Maomao put a hand to her chin and looked at Xiaolan. She still had traces of baby fat, but she had a good face. And there were certain men who would appreciate the way she occasionally stumbled over her words. Most of all, though, she was earnest, and that would get her a long way. The old madam said girls like that were easy to train up, and she frequently bought them from the procurers—in other words, the traffickers.

Maomao quailed at the thought, though. “If you absolutely, positively can’t find any other job, then I’ll make some introductions.” To be perfectly honest, though, she didn’t want to.

“What? You’d really do that for me?!” Xiaolan leaned toward Maomao, her eyes sparkling. Maomao looked away.

I’m afraid she’s getting her hopes up...

In Maomao’s mind, she was a last resort. Her own firsthand knowledge of the pleasure quarter and the courtesans within it prevented her from being able to recommend it wholeheartedly as an occupation. The Verdigris House, which was essentially Maomao’s own home, was one of the brothels that treated its women relatively well, but by and large the pleasure quarter was not a place where one could hope to work—and survive—into old age. Chronic sleep deprivation and malnutrition, along with whatever diseases the customers might be carrying, conspired to end many a courtesan’s life early. Then there were the ones who tried and failed to cut ties with the place, and subsequently found themselves stuffed in a bamboo mat and pitched into the river as an example to others.

Xiaolan had been sold into the rear palace by her parents; when she left, it would be up to her to make her own way. It was understandable how that might produce some anxiety—or drive her to start asking around about “connections.”

Am I sure I don’t have anything better? Maomao asked herself.

It crossed her mind to recommend her to Jinshi, but then she shook her head. Introducing her to him would only get Xiaolan caught up in who knew what kind of trouble.

Maybe the quack doctor, then. She crossed her arms and grunted—and then suddenly a face appeared.

“What’s up?” The speaker was a tall young woman with a unique hairdo and a distinctly non-courtly speaking style. Shisui.

“Oh, Shisui! Say, you wouldn’t happen to know a good place to work, would you?”

They say a drowning woman will clutch at any straw, and Xiaolan was doing exactly that. Shisui was only a maid herself, meaning her position was very similar to Xiaolan’s. The chances of getting a useful lead from her were slim indeed—but Shisui said something unexpected.

“You know, I think I just might.”

“What? Really?” Xiaolan all but grabbed onto Shisui. The other girl glanced aside and pointed toward the center of the rear palace’s southern quarter, where a large, low building stood. Maomao was well acquainted with it: it was the great bathhouse. It had been built during the expansion of the rear palace, in imitation of the harems of a nation far to the west.

“Well, it’s not so much that I know one right now. But I think I know how we can get one,” Shisui said, and grinned.

The building was huge, the bathing area in general big enough for a thousand people, with a tub large enough for a hundred.

There were three main bathing areas: a small chamber with an attached outdoor bath for the consorts, a second, larger bath where the trio was standing now, and the third, biggest bath, which the maids usually just took quick dips in.

With a population as dense as that of the rear palace, it was all too easy for an illness to turn into an epidemic, so sanitation was paramount. This bath was part of maintaining that cleanliness.

Out in the wider world, a “bath” usually meant simply washing one’s body. One didn’t get in a tub, but simply filled a bucket with water and washed with it, or otherwise wiped oneself down with a wet rag. In the pleasure quarter where Maomao had grown up, bathing in tubs was the norm, but many of the women who served at the rear palace didn’t even know how to use them when they first arrived. Filling a tub with hot water was just that much of a luxury.

In winter, palace women were expected to bathe once every five days; once every other day in summer. Washing away dust and body odor was all part and parcel, Maomao thought, of making life at the rear palace pleasant. It was also a chance to see if any of the consorts were subjecting the serving women to corporal punishment. It was much like how at the Verdigris House, the madam had kept a close eye on the women to make sure none of the customers were abusing them and damaging the merchandise.

The bathhouse could itself be a vector for spreading illness, but in this garden of women, sexually transmitted diseases were rare, and most of the inhabitants were young and healthy, so serious contamination was unusual.

“I knew we’d have the place to ourselves this time of day!” Shisui said. It was still light out, and few other palace women were there.

“But why the bathhouse?” Xiaolan asked. She had a washcloth in her hand and was wearing only a bathing apron, which left the curves of her body clearly visible—not that there were very many of them.

“You’ll find out.” Shisui was dressed the same way. Her body was awfully developed, though, compared to how youthful her face looked. Her chest was large enough to make Maomao’s fingers flex unconsciously. Apparently Shisui dressed to hide her proportions.

Shisui herself, meanwhile, grinned broadly and jumped into the bath.

“Hey! You have to rinse first! They’ll get mad at you!” Xiaolan cried.

“Yipes! It’s hot!” Shisui yelped even as she pulled off her apron. Her skin was turning red where she’d plunged in. Maomao grabbed a bucket and brought over some water from the cold-water bath.

Xiaolan sniffed, annoyed. “Hmph. Have you never bathed at this time of day?”

The eunuchs only filled the tubs once a day, so they started with extremely hot water, and over time, it cooled down until it was the perfect temperature. During the warm season like this, therefore, not many people were eager to hop in the bath immediately after it was filled. But later on it got crowded—so those who did wish to take an early bath were allowed in. That was why Maomao and the others could be there now.

“Hee hee. I always come a little later,” Shisui said.

Maomao mixed cold and hot water in her bucket, then started to wet herself down. She used some shampoo she’d swiped from the medical office; as it bubbled, she wetted her hair and worked her fingers carefully along her scalp.

“Let me have some of that, Maomao!” Shisui said and stuck out her hand. Maomao obligingly poured a bit of the shampoo from its bottle into her palm. Her own head still covered in suds, Maomao poured some of the water from the bucket over Xiaolan’s head and washed her hair with the shampoo as well.

“It stings my eyes,” Xiaolan said.

“Then close them.”

She worked her fingers over Xiaolan’s scalp, getting a good lather going, then washed the bubbles away with more water. Xiaolan shook her head like a dog shaking itself dry, flinging suds in Maomao’s face. “I’m not a big fan of baths,” she said.

“No? But they feel good,” Shisui said.

“I agree.” Maomao sought out a comparatively cool place in the tub and dipped her toes into the water. Concerned that the heat would go to her head, she put more cold water in her bucket and used it to keep her face cool as she soaked.

Shisui slid into the tub like Maomao, while Xiaolan got in the cold bath. She was probably more comfortable there; farming villages like her hometown usually didn’t have a custom of bathing in hot water.

Xiaolan rested her arm on the edge of the tub and looked over at the other girls. “How is this supposed to be a ‘connection’ to anything?”

“Just look over there.” Shisui pointed to the outdoor bath, usually the abode of the more important women of the rear palace—consorts and higher-ranking ladies-in-waiting. It was attached to the small chamber that was reserved for the consorts’ use.

“What’s over there?” Xiaolan asked.

Shisui got up, took Xiaolan by the arm, and dragged her outside. She guided her over to a stone platform beside the outdoor bath.

“H-Hold on, are we even allowed to be out here?” Xiaolan asked, a little panicked, but Shisui only grinned, stood by the platform, and tied a hand towel around her head.

Well, now... Maomao thought. She thought she had a pretty good idea of what Shisui had in mind. She joined the others by the platform and tied a towel around Xiaolan’s head. Xiaolan still looked confused, but soon two women approached them.

“New here?” one of them asked. From her haughty tone, it was easy to guess she must be a consort.

Shisui just smiled and said, “Yes, ma’am.”

Then the consort laid down on the stone platform as if it were the most natural thing in the world. The other woman, evidently her lady-in-waiting, produced a bottle of perfume oil.

“Good and firm, please,” the consort said.

“You’ve got it!” Shisui replied, taking the perfume oil and slowly pouring it over the consort’s shoulders.

“Mmm... A little to the right,” the woman said languorously. Her lady-in-waiting stood by, looking bored.

Kind of doubt she’s been with the Emperor, then, Maomao thought, taking some of the oil and rubbing it into the woman’s legs and feet, trying her best to imitate Shisui. Xiaolan did likewise.

When a woman had been the Emperor’s bedmate, she would become the target of harassment from the other consorts and palace women. She would learn to be vigilant—no one in that position would let an unknown serving girl give her a massage. This woman, though, was flopped on the table like an octopus. She had a certain beauty, as all consorts must, but Maomao couldn’t help noticing that her skin looked a bit abused; there were marks where her fine hair had been plucked.

That really bugs me.

How could it not, Maomao having been raised in the pleasure quarter? On impulse, she ducked back into the building, looking for something.

“What’s that?” Xiaolan asked quietly when she came back. Maomao was holding a thread about sixty centimeters long.

“You’ll see,” Maomao said. Then she struck up a conversation with the consort’s lady-in-waiting. The other woman looked a little suspicious, but listened. At length, she sat down on the edge of the stone platform and held out her arm. Maomao ran the thread along it. The surface of the thread caught her hair and pulled it out.

“It doesn’t hurt too much?” Maomao asked.

“It’s pretty uncomfortable, but it’s sure better than a dull razor.” The other woman seemed like a decent lady-in-waiting. Typically, this sort of thing was done after a good, thorough cleaning, but the women looked like they had already been in the bath, so it should be fine.

“I’ll stop if it seems to be irritating your skin,” Maomao said. She decided to start with just one arm. After carefully removing all the hair, she doused the limb generously in perfume oil. It was a good perfume, modestly scented; it didn’t assault the nose.

“Hmm, well, let’s see how it goes for now. When will you be around next?” the lady-in-waiting asked with a glance at her mistress, who was melting on the stone table.

“When would you like?”

“Say the day after next, maybe?”

Shisui grinned at that. Xiaolan was working on the woman’s thighs, still not quite sure what was going on.

I see what she’s going for, Maomao thought. If they didn’t have connections, they could just make some. The bathhouse was an important venue, a place where they could meet the consorts, whom they could never normally get close to.

By the time the satisfied consort and her attendant left, the next customer for their massage service was already waiting.

Playing bathhouse attendant was tiring work. It took a lot of effort to massage someone’s entire body. It wouldn’t have been so bad doing just one person, but before they knew it, there was a line.

They eventually learned that the lady who used to give massages here had recently reached the end of her contract. One of the middle consorts had taken a liking to her, and now she was employed in the woman’s family home.

In the wider world, bathhouse attendants were often treated as prostitutes, but there were only women here, so it wasn’t an issue. However, perhaps because of the association, or perhaps simply because it was physical labor, many of the palace women didn’t like doing this job. So it was that Maomao, Shisui, and Xiaolan became the go-to women for massages. It meant that much more work to do—Maomao and the others were, after all, supposed to be handling laundry—but it brought its benefits.

“Here, have this. It isn’t much, but take it,” a lady-in-waiting said as she got out of the bath, discreetly passing them a small fabric pouch. This didn’t happen every time, of course. This particular woman seemed to have appreciated the hair removal, that was all. When they peeked inside, they found candy. That set Xiaolan’s eyes sparkling, and she promptly popped a piece into her mouth. “Ahh, bliss...”

So she could achieve bliss just by having something sweet to eat. Lucky girl.

The three of them had finished their work in the baths and were perched on the railing out front, cooling off. The sun was still high in the sky; it was a bit early for dinner. Other women were rushing around, trying to finish their work before sundown. The ones tasked with cooking the food looked especially busy.

Maomao was something of a special case, but for Xiaolan and Shisui, the compromise of getting to the bath early was having more work left to do later. They were enjoying a few precious moments of relaxation before they got back to their jobs.

“I guess it’s not that easy to make connections,” Xiaolan said, rolling the candy around in her mouth. Maybe she’d been expecting that they would be up to their ears in job offers by now.

“Oh, it’s not so bad,” Shisui said. “When your contract is about to run out, just find one of the consorts who likes you all right and whisper in her ear. Tell her your service will be ending soon.”

“I hope it’ll work...”

“Even if she doesn’t take you on personally, you might at least be able to get your contract extended. And even if that doesn’t happen...” Shisui took something from the folds of her robe: a comb missing several teeth. Despite the imperfection, it was a turtle-shell piece that must have been worth a fair bit of money. “...You can always turn something like this into cash!”

“Hoh!” Very clever, Maomao thought. She didn’t much like sweet things and had given her candy to Xiaolan. And speaking of clever...

The word also described the consort Maomao served. Maomao was going to the baths once every two days, and she always seemed to be in the company of Shisui and Xiaolan. Many women might have frowned on her paying so much attention to other consorts. Consort Gyokuyou, however, simply said: “Oh? You hear lots of interesting things in a place like that. Let me know what you learn.” She was unflappable.

It was true; consorts and ladies-in-waiting often spoke offhandedly about things of great interest when they were really relaxed. Perhaps they didn’t realize that Maomao was herself a lady-in-waiting at the Jade Pavilion, or maybe the steam from the hot baths obscured her enough that it was hard to tell. Whatever the case, people spoke to her of their families’ business situations, the behind-the-scenes goings-on of other consorts, and other secrets.

There were rumors about Consort Gyokuyou too. Maomao realized that the sharpest consorts had guessed she was pregnant long ago, and all the talk now was about whether it would be a boy or girl and when it would be born. A handful of gossip held that Consort Lihua might be pregnant as well; Maomao was unsettled to realize people were already thinking along those lines.

But there were still other rumors. Such as one that said perhaps Consort Loulan was with child. She’d been known for her gaudy outfits ever since she got to the rear palace, but recently she’d started to favor billowing clothes and seemed to avoid going outside, both of which fueled the stories.

Hmmm...

Consort Loulan had arrived at the beginning of this year, and they were already at the end of the eighth month, going into the ninth. It was unthinkable that His Majesty would have failed to visit Loulan, a high consort who had arrived with such fanfare. If the rumors were true, it would mean that three of the four upper consorts were pregnant. Happy news? Or tidings of trouble? Either way, it was an unsettling prospect.

And there was yet another interesting story going around...

“I thought making eunuchs wasn’t allowed anymore.”

Maomao knew what Xiaolan was getting at. Alongside the new palace ladies who had been taken on recently, the number of eunuchs had increased as well, but the creation of new eunuchs was supposed to have been outlawed when the current Emperor had taken the throne.

“They’re former slaves,” Shisui said blandly. Slavery was also supposed to have been outlawed; these men probably hadn’t been slaves in Maomao’s country. Among the tribes were some who captured people from the surrounding nations, castrated them, and made them slaves. These new arrivals must have either run away or been rescued.

“They say there’s thirty of them. With a number that big, there must have been a pretty serious move against the tribes.”

When slaves escaped, there was usually some impetus like that behind it. Maomao recalled there’d been some issue with such an expedition the year before; maybe the men had been rescued then. Shisui might look and sound youthful, and she might have a strange predilection for bugs, but she could be surprisingly worldly.

“That’s rough,” Xiaolan remarked.

“You said it,” Shisui replied. They sounded as if it hardly concerned them. Then again, it hardly did.

Then Xiaolan said, “You know, they say one of the eunuchs is awfully cool. I’d sure like to get a look at him.”

That sounded all too familiar to Maomao, who scowled.

“We’re talking about a eunuch, remember. Still interested?” Shisui asked.

“But cool is cool, right? Ooh, maybe he’ll be assigned to bring the water for the baths!” Xiaolan’s eyes were positively sparkling. Evidently it didn’t matter to her whether this man had that most important of possessions or not. She was still so young. “I’m still interested,” Xiaolan added. “Even if he isn’t as great as Master Jinshi.”

Maomao almost fell clean off the railing she was leaning against.

“You okay?” Xiaolan asked, peering at her. Maomao brushed off her skirt and straightened up again, pretending it was nothing. “Come to think of it, Maomao, you and Master Jinshi are always—”

“—running errands for the consort, yes.” Maomao said forcefully. As if to communicate: nothing more and nothing less.

Unconsciously, she brushed at her skirt with her left hand. It was like she could still feel the frog she’d accidentally grabbed hold of. Yeah, the frog. The frog, she kept repeating, trying to calm herself down.

She hadn’t yet seen Jinshi since they’d returned from the hunting expedition. She assumed he would soon be coming to the Jade Pavilion on his routine rounds, and she wasn’t really looking forward to it. She was still repeating the frog, the frog to herself with the intensity of a monk reciting a sutra when two familiar faces entered the bath: an uneasy-looking young woman, and a palace lady attending her. The young woman had a cute face, but at the moment her brow was knitted in distress.

Is that...Consort Lishu?

Yes, and her chief lady-in-waiting. Maomao watched them, wondering what they were doing there.

Chapter 2: Seki-u

I feel like I’m being...stared at, Maomao thought. By whom? The three people in front of her.

Today’s snack was steamed buns. Some of them contained red bean paste, but others were plain, with no filling, and Maomao, who wasn’t very fond of sweet things, preferred those. Instead of the bean paste, she liked to eat them with leftover stewed vegetables.

In the Jade Pavilion, the ladies-in-waiting took their breaks in turns. Maomao was often on break at the same time as Hongniang or Yinghua, and recently she’d often simply been away from the pavilion entirely, but now she found herself on break with the three new girls.

To be quite honest, she was uncomfortable. Maomao wasn’t very good with people to begin with; it was a full month after the new girls had arrived, and she had only just started to remember their names. The three of them looked very similar. At first Maomao thought it might simply be because they shared a hometown—but in fact, they were sisters.

Haku-u, Koku-u, and Seki-u, she repeated to herself. The names themselves weren’t hard to remember. They simply meant White Feather, Black Feather, and Red Feather. Remembering which of the girls was which—that was the tricky part. She’d already mixed them up several times, until in exasperation the girls had each taken to wearing a hairband that matched the color of their names (somewhat as the special envoys had done), whereupon Maomao was finally able to remember who was who.

They weren’t triplets, but had each been born in successive years: Haku-u was the oldest, followed by Koku-u and then Seki-u. They had good looks, as befitted ladies-in-waiting to an upper consort; their flowing eyebrows suggested they had been drawn in with charcoal. They all had lovely, almond-shaped eyes, but it was the middle girl, Koku-u, who struck Maomao as the strongest of spirit.

“Not going to have any?” Maomao asked. She’d already sat down and started in on one of the steamed buns. Tea had been waiting; Guiyuan, who had been on break just before them, had prepared it for them. The leaves had already been steeped before, but it was still quite tasty.

“Sure...” The oldest sister, Haku-u, sat down, followed by Koku-u and then Seki-u.

None of them said anything. Maomao didn’t mind silence as such, but it made her feel funny to have people watch her eating. Maybe there’s something they want to say. If there was, she wished they would go ahead and say it. Maomao wasn’t interested in dragging it out of them. With superiors it was one thing, but when dealing with colleagues, she wasn’t going to go bending over backward on behalf of people she felt no special affection for.

They ended up eating their buns in silence. Maybe the new girls felt they couldn’t say anything if Maomao didn’t speak first. They should have just chatted among themselves, not minding her, Maomao thought.

She finished her snack and washed it down with the rest of her tea. Haku-u, the young woman with the white hairband, looked at Maomao and finally spoke: “I have a question. If you don’t mind.” Her speech was deliberate and careful. Maomao had heard that Seki-u, the youngest, was her own age, which meant Haku-u must have been about twenty this year. That would make her as old as Gyokuyou and older than Yinghua and the others; maybe that explained how composed she was. “How, if I may ask, did you come to serve in the Jade Pavilion?”

“How”?

Well, there hadn’t been enough hands at the Jade Pavilion, and Jinshi had pressed her into service as a food taster at what he found to be a convenient moment. Maomao assumed Yinghua or one of the others had told the new girls at least that much at some point.

“Yes, we know that,” Haku-u said. “But that doesn’t actually explain anything. Gyokuyou isn’t quick to trust anyone, but she trusts you. Why?” She grimaced as she said Gyokuyou, with no title or honorific.

I see, Maomao thought. Maybe Haku-u felt close to Gyokuyou, being the same age. It shouldn’t have been surprising if she was suspicious of an unknown person getting close to the consort. “I’m really only a food taster. If someone were to try to poison Consort Gyokuyou, I would be the one to suffer the consequences. I ask that you view me in terms of that role.”

It was the honest answer. There was no particular need to tell her about the incident of the toxic face powder that had led to Maomao’s introduction to Gyokuyou.

“They said you don’t mince words. Turns out it’s true.”

“Thank you.” Maomao wasn’t sure whether that was actually a compliment, but she bowed her head just the same. Haku-u might have been a newcomer, but she did outrank Maomao, after all.

“I also hear you have a lot of outside friends, but I hope you won’t spend too much time socializing. My sisters and I are trying to figure out life in the rear palace. You must know we get lonely when our more experienced colleagues spend all their time visiting. My youngest sister, in particular.” Haku-u jabbed the youngest sister with her elbow; but Seki-u, the girl with the red hairband, looked away as if to deny it.

They weren’t wrong, Maomao reflected. She had been spending a lot of her time with Xiaolan and Shisui recently, and she realized now that hadn’t been entirely appropriate.

Ironically, though, she’d promised Xiaolan and Shisui that she would go see them later today. Doing the consorts’ hair removal had become Maomao’s job. If she dropped out now, the other two would have to scramble to cover for her. She was just fretting about what to do when she had a thought. All she really needed was someone to keep an eye on her, to make sure she didn’t do anything suspicious, right?

“Then why waste any time?” she said. “Let’s go to the baths today.”

“Huh?” Seki-u said, caught off guard by the invitation. The three sisters might look much alike, but their ages still made them distinct. Seki-u came across as rather innocent. So long as she wasn’t too brusque, though, Xiaolan and Shisui should be able to handle her easily enough. And Maomao would let them.

At the word baths, Haku-u and Koku-u looked at each other. Was it just Maomao’s imagination, or did they share a grin for a fleeting second?

“That might just be a good idea. Seki-u, it would do you good to spend time with other girls who aren’t your sisters.”

“But sister!”

“Yeah, you know, you might be right. Besides, Lady Gyokuyou ordered us to go to the baths sometimes.”

“That’s true.”

Scandal-hunting was a job itself, in some sense. Maomao beckoned Seki-u over to her.

“Koku-u, why don’t you come?” Seki-u ventured.

“Sorry, I have to work. Have a nice time.” The otherwise quiet second sister agreed with the eldest, leaving their younger sibling without much choice.

Maomao, meanwhile, thought she’d started to grasp the sisters’ particular pecking order.

“I’m Seki-u. Pleased to meet you,” Seki-u said nervously.

Xiaolan and Shisui, for their part, were bubbling with interest in Maomao’s new companion.

“Ooh,” Xiaolan said, “have you got a new frieeend, Maomao?”

“Well, I’ll be,” Shisui added.

The two of them managed to surround Seki-u all by themselves. Maomao ignored them and their quaking new acquaintance, instead making sure she had everything she would need. She had a beauty salve, in case the hair-removal process irritated someone’s skin, and a silk thread. She’d wanted to bring the leftover “textbooks” from the pleasure district in hopes of selling some, but had given up the idea: it would be too hard with Seki-u along.

Speaking of Seki-u, she was looking at Maomao pleadingly, evidently viewing her as her safe harbor now that her sisters weren’t around.

I suppose I should rescue her, Maomao thought. She pointed in the direction of the bath as if to say Let’s go, and Xiaolan and Shisui raised their hands and went jogging off.

“Who are those people?” Seki-u asked.

“They’re harmless.” I think, Maomao added mentally. Then she trotted toward the baths herself.

“Wait for me!” Seki-u cried, and rushed after her.

The work wouldn’t be that hard today, as a number of additional massage-givers had shown up recently. When they peeked into the baths, they could see another palace woman giving a massage. Maybe the other women had started to take an interest when they realized that Maomao and the others were receiving little indulgences from the consorts. The previous masseuse had evidently done a better job of keeping the fact hidden.

Maomao stripped down to her apron in the changing room, then proceeded into the bathing area with her bucket full of tools. Seki-u, though, just stood there fidgeting uncomfortably.

“What’s the matter?” Xiaolan asked earnestly.

“Is this all we’re wearing?” Seki-u asked.

“Yeah. It gets hot in the bath if you have too many clothes on.”

Seki-u, it would appear, was embarrassed. Shisui came up behind her with a wicked smirk, then grabbed her sash, tugging it loose. She pulled off Seki-u’s robe and held it up high.

“Huh!” Maomao and Xiaolan exclaimed in unison. They both seemed to be thinking the same thing: that Seki-u had nothing to be embarrassed about. (Xiaolan, like Maomao, was only modestly endowed.)

“Aw, it’s fine,” said Shisui, who herself was considerably more than fine.

“Fine, indeed!” Seki-u exclaimed. “I wish I was flat as a board!” She looked at Maomao and Xiaolan. Xiaolan was beginning to look angry, and the eyes of several of the women nearby glinted as well. She was going to make enemies at this rate, Maomao thought.

Shisui seemed to have the same intuition, for she passed Seki-u an apron in lieu of her robe. “Sure. Sure, I hear you. Come on, let’s get to the baths,” she said, giving Seki-u a couple of encouraging pats on the shoulder.

I knew she’d be easy to tease, Maomao thought, but I never imagined it would be this easy. She followed Seki-u and Shisui toward the bathing area.

Seki-u’s reticence in exposing her body suggested she came from somewhere without a custom of bathing regularly. She was from the same village as Consort Gyokuyou, which would mean she was from the dry lands to the west. Water was a precious resource there; no wonder Seki-u wasn’t accustomed to bathing. They had saunas, but probably not any large bathhouses like this one.

“How have you been managing all this time?” Out in the desert it might be one thing, but around here, your body odor would turn noticeable very quickly if you didn’t bathe routinely. Especially now, in the hot season. Just wiping yourself down almost certainly wouldn’t be enough.

“My older sisters come here, but I asked Lady Gyokuyou for special permission, and...”

Apparently she’d been allowed to use the bath in the Jade Pavilion. Such amenities were ordinarily reserved for the lady of the house. His Majesty sometimes used them as well, but, er, not for bathing as such. (Hence, we’ll omit the details.)

Maomao realized that she had in fact seen Seki-u heading for the Jade Pavilion’s bath on several occasions. Even if she was only using the place after her mistress was done with it, she’d been intimidated enough to try not to draw attention to herself. It explained, though, why the other sisters, seemingly so loyal to each other, had been so ready to sell Seki-u out to Maomao. Since the youngest girl had Consort Gyokuyou’s permission to use the private bath, they felt they couldn’t drag her to the public one. But when Maomao had invited Seki-u along, they saw their chance.

“Sounds like you’re embarrassed,” Maomao said. “But there’s not going to be any time for that once we get started here.” Then she dipped a hand towel in a bucket and started cleaning herself off.

If Seki-u was reluctant to even let her chest be seen, what must she make of the consorts lying on the stone table without a thread on them? Gyokuyou insisted on doing virtually everything for herself, so Seki-u had probably never seen the like of it before. She looked like the whole thing was making her head spin—but Maomao didn’t have time to worry about her.

“Here, take this.” Maomao passed her the perfume oil. “You can at least rub it on them, right?”

“R-Rub it on them?!”

“Uh-huh. Pretend you’re marinating some chicken.” Maomao added in a whisper that this would cause the women to relax—which would make them more talkative.

Seki-u frowned intensely, but slowly, fearfully, began to daub the prone consort with oil. Xiaolan, who was getting quite good at this, took some of the excess and began to work it into the woman’s skin.

Maomao was still in charge of hair removal, which, unlike massage, wasn’t something one necessarily needed every day. Hence, she was finished before Xiaolan and Shisui, leaving her with little to do. She was sitting on the stone platform, waiting for their next customer, when she spotted a hesitant figure.

Well, look who it is... Consort Lishu was back. She had her chief lady-in-waiting with her again and was looking around uneasily. Wonder what’s going on. Each of the upper consorts had her own bath at her pavilion. Lishu didn’t need to come all the way to the public bathhouse.

She was so busy looking around nervously that she didn’t notice the bucket near her feet and nearly tripped over it. It was very characteristic of her, somehow. Lishu was one of the four upper consorts of the rear palace, but she was something of a sheltered princess, still just fifteen years of age and having never received a visit from the Emperor.

Her chief lady-in-waiting was trying to hold her up, but the floor was just too slippery, and Lishu came tumbling down. Maomao wondered if she didn’t have any other ladies she could rely on—but then she thought of the women at the Diamond Pavilion and realized there was simply no one trustworthy among them.

Finally, Maomao felt compelled to head over to Lishu. Some perfume oil or something had spilled on the stones; Maomao poured bath water over them so there wouldn’t be any more tripping.

“Oh, thank y—rgh?!” The chief lady-in-waiting’s words of gratitude turned to a strangled shout as she saw Maomao. For some reason, Lishu shared her expression of horror. Maomao gave them both a bit of a scowl, but they were shaking like newborn foals. She wished they wouldn’t look at a person as if she were some kind of monster. She could take a hint, though, and she was about to go back to the massage table when she noticed something. There were places all over the quavering Lishu’s body where the hair hadn’t been removed properly; it looked as if someone had tried to shave her with a razor, but they’d left plenty of scratches and even some cuts here and there.

“Would you prefer to try a different way of removing hair?” Maomao said.

“Wha?” Lishu appeared taken aback by the offer, but she didn’t resist when Maomao pulled gently on her hand. That was close enough to assent. Maomao thought she still detected some faint trembling but was determined to ignore it. The shoddy shaving bothered her. (Maomao was sometimes bothered by rather unusual things.)

She urged Lishu onto the stone platform—the consort seemed to have the same reluctance as Seki-u to expose her chest—and then began to apply lotion, though she frowned a little as she did it. Xiaolan noticed the cowering consort and the lady-in-waiting who stuck close to her and promptly understood what was going on; she helped pin the consort on the table.

“Don’t worry,” Maomao said. “I’ll be gentle.” She was bent on doing the best job she could.

Seki-u, meanwhile, could only watch, her eyes full of sympathy for the consort.

After the hair removal, Lishu’s skin was silky smooth. Almost without realizing it, Maomao hadn’t stopped with her arms and legs, but had gone over every inch of her body. Xiaolan was diligently doing the aftercare, daubing the consort with perfume oil. Shisui had needed to help another “customer,” who then gave her some juice that she was now enjoying. Xiaolan was looking at her enviously. Hmm: should they try to ask Consort Lishu for an honorarium? Maomao wondered. Looking at the consort, though, who was plastered to the table looking like her soul had left her body, she thought better of it.

“Is this sort of thing new to her?” Maomao asked the chief lady-in-waiting.

“Y-Yes. At the, uh, pavilion, most of the women don’t pay much mind to these things. And before that, she spent quite a while in a convent.”

“Ah, yes, that’s right.”

In fact, Lishu’s story was rather a sad one, when you thought about it. Married off to a pedophile emperor as a political pawn at an early age, sent to a convent after his death, then forced back to the rear palace by her family. And once there, surrounded by good-for-nothing ladies-in-waiting.

The chief lady-in-waiting had been among the consort’s tormentors once, but now she was her mistress’s staunch ally, a fact that impressed Maomao. Since she was here anyway, Maomao thought she might as well make the chief lady’s skin nice and smooth too, but while the woman submitted to having her arms and legs done, she fiercely resisted when it came to her most sensitive parts. Maomao didn’t see the problem: they were all women here, after all.

Once they had finished with Consort Lishu and her chief lady-in-waiting, their work was mostly done for the day. They put on loose robes and tried to cool off from the heat of the baths. Lishu suggested some juice, and while it was altogether possible that she was simply being polite—that she really hoped they would turn her down—the other girls eagerly accepted. Xiaolan was openly joyful, while Seki-u didn’t really understand what was happening but went along anyway.

Other ladies were attending the other consorts, while Shisui had slipped outside where one of the consorts was treating her to a puff on a pipe. She did know how to play the game.

“If I may ask,” Maomao said to Lishu’s chief lady-in-waiting once they were settled in the consorts’ cooling-off area, “what brings you here? I thought the Diamond Pavilion had its own bath.”

“Yes, well...” the lady-in-waiting said uneasily. She looked at Lishu, whose face glowed with the warmth of the baths but had begun to regain its composure. In fact, if anything, she looked a little pale. “That’s where it appeared. In the bath...” Now the lady-in-waiting looked as pale as her mistress. “A ghost...”

Chapter 3: The Dancing Ghost

Seki-u had looked very upset indeed when she’d realized the retiring young lady was one of the upper consorts. But once Maomao had heard the story, it would have been impossible to keep her from involving herself in it.

And so it was that the next night Hongniang told Maomao, “Sir Jinshi is asking for you.” The food tasting was over; Maomao, who had been sipping her dinner of congee, quickly cleaned up her bowl. Seki-u, who had been eating with her, frowned, but didn’t go so far as to say anything.

At the baths the day before, Maomao had recommended that Consort Lishu consult with Jinshi about the ghost. Maomao couldn’t advise her on the matter directly, not least because the look on Seki-u’s face said she would never allow it. But Maomao knew that if Lishu asked Jinshi about it, there was as good a chance as any that the matter would be referred to her. And now it seemed she’d been right...

I didn’t think this all the way through.

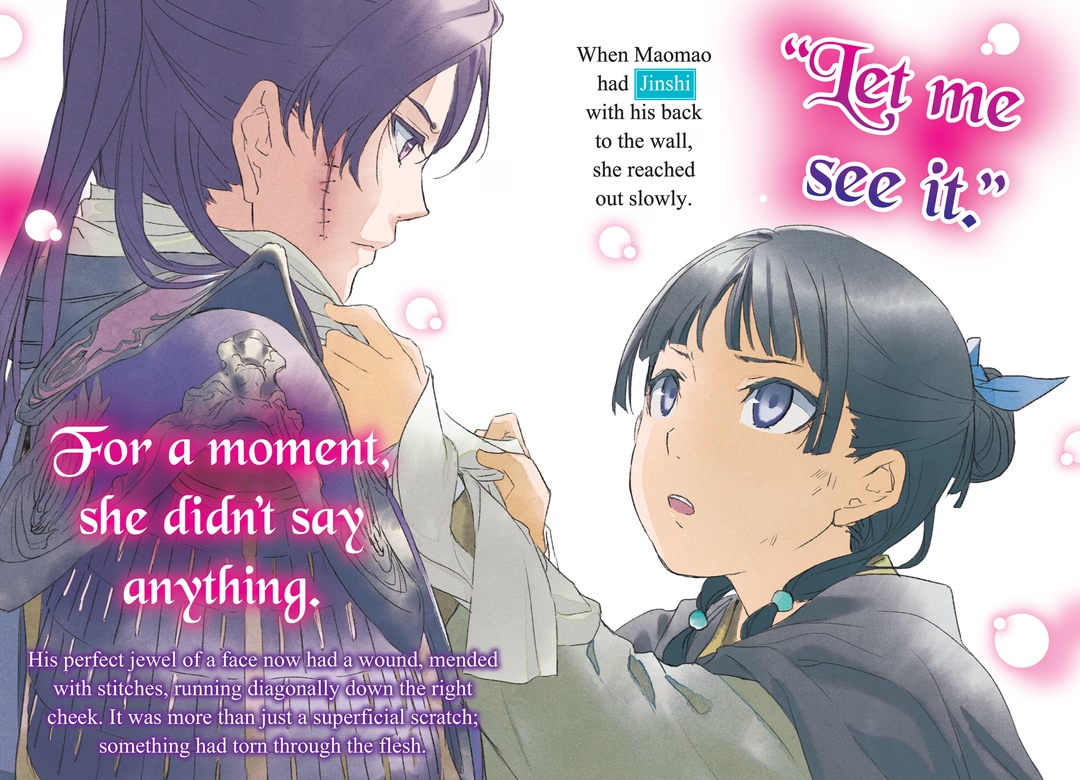

Maomao felt a chill run through her as she was ushered into the sitting room. Gyokuyou was there along with Hongniang, as were Jinshi and Gaoshun. Jinshi wore his usual heavenly smile, but she thought she could see his mouth twitching. All she could think was, Crap.

On a hunting expedition with Jinshi not long before, Maomao had learned a terrible secret. Every man in the rear palace other than the Emperor was supposed to be a eunuch—but she’d discovered that one of them wasn’t. Namely, Jinshi himself. Let’s say simply that he possessed quite a fine specimen. Maomao wasn’t interested in remembering anything more than that.

Maomao had finally gotten her ox bezoars, and would have been happy to pretend nothing else at all had happened, but Jinshi seemed to have other ideas. This was the first time they had properly seen each other since the trip, and while his lips were smiling, his eyes were not.

“He he he. And what kind of request brings you here today?” Consort Gyokuyou asked, grinning. Her natural curiosity made her want to stick her nose into all the various matters Jinshi brought to Maomao. This particular case had to do with Consort Lishu, though. How would Jinshi broach the subject?

“It seems a ghost has appeared in the chambers of one of the other consorts.”

“My goodness,” exclaimed the red-haired lady, but her eyes were sparkling. Beside her, Hongniang was pressing a hand to her forehead as if to say Again?

Maomao couldn’t help noticing that Jinshi had come straight to the point. She appreciated that he didn’t beat around the bush, but Gyokuyou was sharp enough that she would almost certainly figure out whom he was referring to.

“How terrible. Which consort is it? I must pay her a visit to make sure she’s all right.”

“Lady Gyokuyou, you can’t go outside in your state.”

“Oh no? Then perhaps I can send someone on my behalf. You and Maomao could go together. Or if you’re busy, perhaps I could send Yinghua with her.”

“Making sure she was all right” was presumably the last thing on Gyokuyou’s mind; she just wanted the juicy details. There was no point hiding Lishu’s identity now; the truth would come out as soon as Seki-u opened her mouth. Jinshi had to know that, but perhaps out of some desire to get back at Gyokuyou, he replied, “Consort Gyokuyou, this is a matter of utmost secrecy, so I must ask you not to pay her a visit or send anyone. Such being the case, might you return her to me again?”

“I might be able to lend her to you.”

The object of all this returning and lending was, of course, Maomao. She, Gaoshun, and Hongniang all sighed at once: were they going to see a repeat of last time?

“No, I want you to return her to me—this girl right here! Maomao!” Jinshi stood in front of Maomao and pressed a finger down on her head. Then he let it slide down her hair. “And when she gets back, I believe you’ll find you get no information out of her.” His hand brushed her cheek, his pinky and ring fingers floating across her lips. “Because I’ve taken pains to keep her quiet.”

Then he left the room, walking with an impossibly elegant gait. Gaoshun, openly shocked, followed him. The other inhabitants of the room looked at Maomao with their mouths agape, but she wore much the same expression they did.

It was Gyokuyou who made the first move. “What happened between you two?” Her gaze, still shell-shocked, settled on Maomao, who found the look downright painful.

Gyokuyou proceeded to interrogate her for the next thirty minutes, but Maomao would say only: “It was the frog’s fault.” She was starting to think that a few ox bezoars had been too cheap a price for a secret she would have to carry to her grave.

Maomao wondered what kind of apparition this “ghost” was. Quite frankly, she didn’t believe in such things. There had been the incident at the scary-story gathering a while back, but Maomao had no idea if there had been anything supernatural about that. Yinghua, though, was convinced it had been a ghost, and Maomao didn’t argue.

Call them spirits or whatever; it didn’t matter. Maomao didn’t believe people could be killed by malign supernatural forces. When someone died, there was always a reason: poison, or injury, or sickness. To the extent that a “curse” or the like ever killed anyone, in Maomao’s mind, it was only because the person drove themselves to illness through their own belief that they were a victim of such forces.

In any event, Maomao found herself accompanying Jinshi to the Diamond Pavilion. Personally, she thought this wasn’t necessarily something that warranted his personal attention, that perhaps Gaoshun or the like could have handled it perfectly well, but maybe she was wrong about that.

When they arrived at the Diamond Pavilion in its bamboo grove, it was the chief lady-in-waiting alone who met them. When they realized Jinshi was present, however, the other ladies promptly brushed the dust off their clothes, ran their fingers through their hair, and stood in a line at the pavilion entrance.

Jinshi regarded them with a smile. Maomao could feel a nasty scowl coming on, but Gaoshun looked at her with the gaze of a bodhisattva. He was well aware that Jinshi hadn’t been quite himself since their return from the hunt. He’d pelted her with questions about it, but she wasn’t sure how much she should say and had given only ambiguous answers. Did Gaoshun know Jinshi wasn’t a eunuch? Could he himself be another exception to the rule?

Convinced that thinking about all that wouldn’t get her anywhere, Maomao simply followed them into the Diamond Pavilion.

Consort Lishu was entertainingly easy to read: her face was pale when they arrived, but when she saw Jinshi, she promptly flushed red; and then as they came to the matter at hand, the blood drained from her cheeks again. She might not be Maomao’s mistress, but it was still somewhat alarming to realize someone like her was one of the four most important consorts.

I suppose that could be one reason His Majesty hasn’t taken her for a bedmate, Maomao thought. She was seized by the image of the Emperor as a thoughtful and perceptive man—but then she concluded that it was probably mostly that the bust size involved failed to arouse his appetites. Lishu fell even farther short of His Majesty’s preferred ninety centimeters than Maomao did.

“This way, please.” The chief lady-in-waiting spoke on behalf of her pallid mistress. A veritable crowd of other ladies-in-waiting followed them around, but their main objective seemed to be Jinshi; to be blunt, they were in the way. To put it poetically, one might have said that it was like a beautiful flower surrounded by a crowd of butterflies. But the ladies-in-waiting were far noisier than butterflies, and the overall effect was more like a cloud of flies buzzing around a fish head.

If they knew he wasn’t a eunuch...

Ugh. Maomao didn’t even want to think about it.

As she was thinking he ought to just hurry up and chop it off (not a very ladylike idea, true), they arrived in the bathing area. Jinshi and the other eunuchs paused briefly, but it was always eunuchs who brought the hot water for the bath anyway, so surely there was no problem.

“Here.” The chief lady-in-waiting stopped before the changing room; Consort Lishu stood some distance away, afraid to get too close. “The consort says she was standing here when she witnessed a mysterious figure.” She gestured in the direction of the changing room window. There was nothing beyond, just a blank wall: a storage room could be seen beyond the window. Normally the window would have been covered with a bamboo screen, but it had happened to be open and the consort had happened to glance through it.

“Can you describe the figure to me?” Maomao looked at Lishu, who was clutching her skirt and looking at the ground. It made her seem so young. She lacked any of the authority one associated with a consort.

“Are you still talking about that?” one of the ladies-in-waiting, evidently inspired by her mistress’s cowering demeanor, asked in a nasal voice. “You’re just so desperate to get attention, Lady Lishu. I’m sure it’s nothing to worry about. You must have been seeing things.”

The woman stepped forward importantly, adding a flirtatious glance at Jinshi for good measure. She was pretty—women of the rear palace were, almost by definition—but there was a dangerous glint in her eyes, one her use of eyeliner emphasized.

“I should think it the duty of a chief lady-in-waiting to admonish her mistress for such behavior,” the woman said, shaking her head and sighing. The other ladies-in-waiting clustered around her as if literally falling into line behind her. The chief lady-in-waiting seemed to shrink into herself.

Ah-ha, Maomao thought. The haughty woman must have been the former chief lady-in-waiting. It must have rankled her to be demoted in favor of the food taster. She probably needled her like this every day.

Jinshi, who could no doubt deduce that much just as well as Maomao, smiled and took a step toward the self-important lady. “You speak truly,” he said. “But my duty is to listen when a consort has something to say. I implore you not to take the chance to do that duty away from me.”

His voice was sweet as nectar, and the ladies-in-waiting could only nod in agreement with whatever he said. Most of the ladies of the rear palace were, let us say, inexperienced with men, making their reactions to them amusingly easy to read. Then Jinshi added softly that he wished to drink some tea—an effective strategy for clearing the room. The ladies-in-waiting all but stumbled over themselves to be the one to prepare his drink. Actually, another lady-in-waiting entirely had already prepared tea long before, but they didn’t know that. He really did know how to do his job.

“Now, milady, might you be so good as to tell me what’s on your mind?”

Thus mollified by Jinshi, Consort Lishu lay down on her couch and finally began to speak.

○●○

I went to take my bath just like normal. Personally, I prefer tepid water, but my ladies always make the water quite hot, so I bathe somewhat late, to give the water time to cool down.

I’ve begun to get the impression lately that my ladies-in-waiting are not especially fond of me. But at least they don’t complain about my bathing alone, which has been my practice ever since my time in the convent. The only time I’m accompanied is when changing my clothes, for which I have the help of Kanan—ahem, my chief lady-in-waiting.

It happened when I had finished my bath and had gone into the changing room. I felt a little overheated while I was drying myself off, so I raised the blind. The window was closed, so not much air came through. But then I saw a flicker. At first I thought it might be the curtain flapping in the breeze, but no. I’d closed the window before getting in the bath, and there shouldn’t have been any breeze. Yet it was flapping.

So I looked over, and then I saw it: a big, round face floating there, flickering and dancing, using the curtain like a robe.

The face was smiling. And the entire time, it looked straight at me.

○●○

The very memory was clearly fear-inducing, for Lishu hugged herself and trembled as she lay on the couch. Kanan rubbed her shoulders gently.

Wow, and she used to be so mean to her. So people really could change, Maomao reflected as she sipped her tea. The tea Jinshi requested earlier hadn’t yet arrived; there seemed to be an argument going on about who would have the privilege of bringing it to him.

There were almond cookies to go with the tea, a rather cosmopolitan snack. They were crispy and seemed like they would keep well, so Maomao kept glancing at Kanan, wondering if she might be able to wheedle a few out of her as a souvenir.

“You don’t think there could have been someone in the area?” Jinshi was asking. “Might you have seen a palace woman and mistaken her for a spirit?”

Lishu and Kanan both shook their heads. “Kanan was with me,” Lishu said. “She came running when she heard me shout. And she saw the ghost too.” Apparently, despite her fear, Kanan had approached the round-faced apparition in hopes of determining its true identity. “But then the ghost disappeared. There was no one around, of course, and the curtain was as still as if it had never moved. The window was shut too. That room doesn’t get much air through it.”

Maomao hmmed and put her hands together, looking at the location Lishu had described. The whole layout seemed off to her. Who would build a storeroom right next to a bath? At the Jade and Crystal pavilions, the bath was a separate structure, with an adjoining room where the consort could relax after her soak. The bath might not be separate in the Diamond Pavilion, but surely somewhere to relax would be a more appropriate thing to put beside it than a storage space.

She was about to steal a glance at Jinshi, but thought better of it and looked at Gaoshun instead. He was looking at Jinshi, an expression of concern on his face. Jinshi waved at them, and Maomao took it as permission to ask whatever was on her mind.

“Has this always been a storage room over here?” she said. She couldn’t shake the sense that there was probably a more pointed question to ask, but decided to start with the first thing that came into her head.

“No, it didn’t used to be,” Kanan said.

“Then why is it now?”

“Er, well...” Kanan stood, looking a little uncomfortable, and moved to the storage room across from the bath. She pointed inside, among the rows of shelves and piles of miscellaneous objects.

“Ah, I see,” said Maomao. She spotted black marks on the wall—mold, she discovered on closer inspection. Once it had taken root like this, it would require more than a little scrubbing to get rid of it. The proximity of the bath must have made humidity an issue here. And yet the Jade and Crystal pavilions didn’t have problems with mold. The ladies-in-waiting of the Jade Pavilion would probably have investigated to figure out where it was coming from so that they could take care of the problem at its source—but such dedication couldn’t be expected from the women of the Diamond Pavilion. In fact, the ladies of the Jade Pavilion, with their diligent cleaning, were somewhat exceptional. Here, they’d decided to sweep the problem under the rug, as it were, by simply turning the room into a storage area.

Still, the problem went beyond a little mold: in places, the wall was soft and springy to the touch. It might even be rotted clear down to the foundations.

“I wouldn’t have said this building was that old.”

“It’s not. It was built when Lady Lishu first entered the rear palace.”

Maomao frowned: could the structure have gotten so unstable in such a short time? Then, she noticed that there was a window directly next to the rotted part. This was the curtain Lishu had said was flapping.

Stroking her chin, Maomao went over to the bathing area; she went through the changing room and peered into the cyprus-wood bathtub.

“There it is.” The words had escaped her lips almost before she knew it. She’d found a small, round hole at the bottom of the tub. To the side of the tub sat a plug. The rear palace had been built over an old sewer system—one of its great conveniences—and the drain no doubt led to it.

In her mind’s eye, Maomao sketched the location of the bath vis-à-vis the storage room, then added in the flow of the sewers. Then she said, “Lady Lishu,” and looked at the consort. “On that day, did you, perchance, accidentally pull out the stopper in the tub?”

Lishu blinked. “How did you know?”

Now Maomao was sure. She walked briskly back over to the mold-infested wall, then tried to move a shelf so she could get a better look at the rotten floor. She wasn’t strong enough to do it alone, but the ever-perceptive Gaoshun quickly came over and helped.

Moving the shelf revealed a spot on the floor so soft that it looked like it might give way if she jumped on it. A crack had formed there between the floor and the wall.

“Would it be possible to check on a blueprint whether the sewer runs directly under this spot?” Maomao asked. It was, once again, Gaoshun who responded promptly to her request. He instructed another eunuch to bring a blueprint of the Diamond Pavilion.

Just as Maomao had suspected, the sewer system ran directly under the floor of the storage room. “With hot water passing just under the floor and steam coming up from it, it would naturally make this wall prone to rot,” she said. “And if some of the steam were to slip out of this crack, it could produce a breeze even with the window closed.”

That explained the flapping of the curtain.

Consort Lishu looked at Maomao open-mouthed, but then her eyes widened and she said, “B-But then, how do you explain that round face?”

Maomao hmmed thoughtfully and stroked her chin again. She looked at the location of the curtain, and the spot where she assumed Lishu had seen the face. Then she turned slowly around in that spot. With the wall at her back, she spotted a shelf at a diagonal from where she stood. It held something covered with a cloth. She approached and removed the covering to reveal a brass mirror. It looked awfully well polished for something left in a storage room; it still had some shine even now.

“That’s—”

“Yes, ma’am?”

Lishu looked at the ground. “That’s very important to me. Please be careful with it.”

Well, it wasn’t as if Maomao had intended to break it. However, she refrained from touching it, instead staring at the mirror’s surface. It was almost exactly the size of a human face. “How long has this been here?” she asked.

“Since the new mirror arrived with the special envoys. I used it all the time before that. It was put here when we got the new one.”

The envoys had brought the consorts full-length glass mirrors, meaning they showed much more than this brass plate, and far more clearly. There would be no comparison—and no reason not to put this one away in storage.

“And yet it appears to have been polished every day,” Maomao remarked. Brass clouded quickly. For the mirror to remain so reflective, it must have been cared for frequently.

Lishu regarded the mirror with a certain lonesomeness. She seemed far more attached to it than to the new gift.

“Since we have it out, take a look in it,” Maomao suggested. She took the mirror, careful to hold it with the cloth, and gave it to Lishu. “It will be easiest to see if you make sure there’s plenty of light.” So saying, Maomao opened the curtain, letting in the sun from outside. The highly polished mirror caught the light and reflected it. “It might be clearest if you hold it like this.” Maomao adjusted the position of the mirror in the consort’s hands. The light struck the brass surface, then reflected onto the white wall.

Everyone present reacted with astonishment: the light formed a perfect circle on the wall, in which floated the face of a smiling woman.

Jinshi was the first to speak: “What is this?” He stared fixedly at the wall as if he couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

Now I get it, Maomao thought. “I’d heard of so-called magic mirrors, but this is my first time seeing one,” she said. These were bronze mirrors that indeed seemed magical: when light struck them, they reflected an image or a message. They were sometimes also called “transparent mirrors” because of the way light seemed to make them see-through when it hit them. They had a long history, although very specialized techniques were required to make them.

Maomao’s adoptive father Luomen had a wide-ranging knowledge that extended well beyond drugs and medicine. Ever since she was small, he’d regaled Maomao with intriguing stories and surprising facts—and this had been one of them.

Presumably, the cloth had simply happened to come off the mirror that night. The polished surface of the mirror had caught the moonlight and projected its image on the wall. The result had been the floating face. A “ghost” created by sheer coincidence.

“This face...” Lishu sniffled, ignoring the tears that ran down her cheeks as she peered at the mirror. “It looks like my poor, deceased mother somehow.” She clutched the bronze plate tightly, her lips twisting with distress and snot pouring from her nose. Quite frankly, it robbed her of any semblance of the authority a consort should have, but it also looked very much characteristic of her. This girl was one of the Emperor’s “four ladies,” yet really, at her age, she should still have been growing up.

Now Maomao knew why she cherished that mirror so much. It was a reminder of her mother. Perhaps she’d hoped to make her daughter feel that even in the rear palace, far away, she was always at her side. Maomao herself didn’t really know what a mother was. But it was clearly something so important that it inspired deeply felt emotions in this consort.

Still indecorously dripping snot, Lishu clung to the mirror. The image on the wall had vanished, but no doubt she could still see that gentle smile in her mind’s eye.

“I wonder if Mother is angry that I changed mirrors. Maybe that’s why she appeared.”

“It was simply coincidence, milady,” Maomao said dispassionately.

“I’m told that she loved dancing. Giving birth to me shattered her body so she couldn’t dance anymore. She died never being able to do it again. I wonder if she came back as a ghost now to dance.”

“There is no such thing as ghosts.”

Lishu seemed not to hear Maomao’s cold pronouncement. Kanan took out a handkerchief and began wiping her mistress’s face.

The scene was robbed of its pathos when someone announced, “Your tea is ready, sir.”

It appeared to be the former chief lady-in-waiting who had won the struggle to deliver the drink. She’d arrived bearing fragrant tea along with snacks. She had an obsequious smile on her face for Jinshi’s benefit, but when she saw her sobbing, snotty mistress, her expression twisted into one of contempt. She quickly regained her smile, however, and slowly approached the consort.

“Lady Lishu, whatever are you crying for? You should be embarrassed, making such a display in front of these people.” She was the picture of a diligent servant remonstrating with her revered lady. But it was far too little, far too late to conceal her true attitude from Maomao. The way she put on her best airs for these important men, but promptly reverted to form outside their company, was no better than a third-rate courtesan. And like so many women of that kind, she knew a raw nerve when she saw one.

“Oh, my, do we still have this mirror?” the lady-in-waiting said, looking at the bronze plate. “And after those envoys were so kind as to give you such a lovely new one. Surely you don’t need this anymore. Why not bestow it on someone else?” She plucked the mirror out of Lishu’s slackened grip and smiled as she gave it an appraising look. No doubt she wanted it for herself.

“—back.”

The sound came from Consort Lishu, but she was curling into herself and her voice was as quiet as a fly, and the lady-in-waiting didn’t notice. She was too busy stuffing the mirror into the folds of her robe like a juicy piece of loot. She was just about to return to serving Jinshi his tea when Lishu reached out and caught her sleeve.

“Give it back.”

“What’s that, milady?”

“Give it back!” She tore at the woman’s collar, grabbing the mirror. The former chief lady-in-waiting was aghast, and Lishu’s other women, who had come bustling in belatedly, wore frowns of their own.

“What a way to behave—and in front of guests! You should be ashamed of yourself.”

The weeping, the grabbing: taken in isolation, they would seem to reflect poorly on Consort Lishu. It simply looked as if she had lost her temper. Whatever the other ladies-in-waiting may have thought having arrived late, however, Maomao, Jinshi, and the others knew that they were witnessing only the denouement of this struggle.

It was Jinshi who moved first. “It appears that mirror is a personal treasure of hers. I question whether it’s wise to take it from her without fully understanding what it is.” His tone was gentle and his words were delicately chosen, but it was unmistakably criticism. He stood before the lady-in-waiting, who was straightening her collar, and reached out one large hand. She blushed furiously, for it looked as if he was going to stroke her hair—but then instead he pulled out the hair stick she was wearing.

It was a beautiful piece, finely sculpted; Jinshi squinted at the crest it bore. “Was this also bestowed on you?” he asked. “Even if it was, I’m surprised you never learned that a mere lady-in-waiting who wears the crest of a high consort is reaching above her station.” Once again his tone was gentle, and his smile never slipped. But that made it all the more frightening.

Jinshi had to be well aware that Consort Lishu had been at the mercy of her ladies-in-waiting. He’d refrained from making the matter public because it would have been ruinous to Lishu’s reputation, as well as because, as a eunuch, it was simply not business in which he ought to be involved. With physical proof in his hands, however, he was now free to speak his mind. And he would drive the point home as hard as he could.

“In the future, I hope you’ll refrain from overstepping yourself,” he said. That unutterably lovely smile was on his face. The former chief lady-in-waiting simply crumpled to the floor; the other women, evidently remembering trespasses of their own, had all gone pale.

Wow, is he scary, Maomao thought: Jinshi was sipping his tea as if nothing had happened at all.

Chapter 4: The Rumored Eunuchs

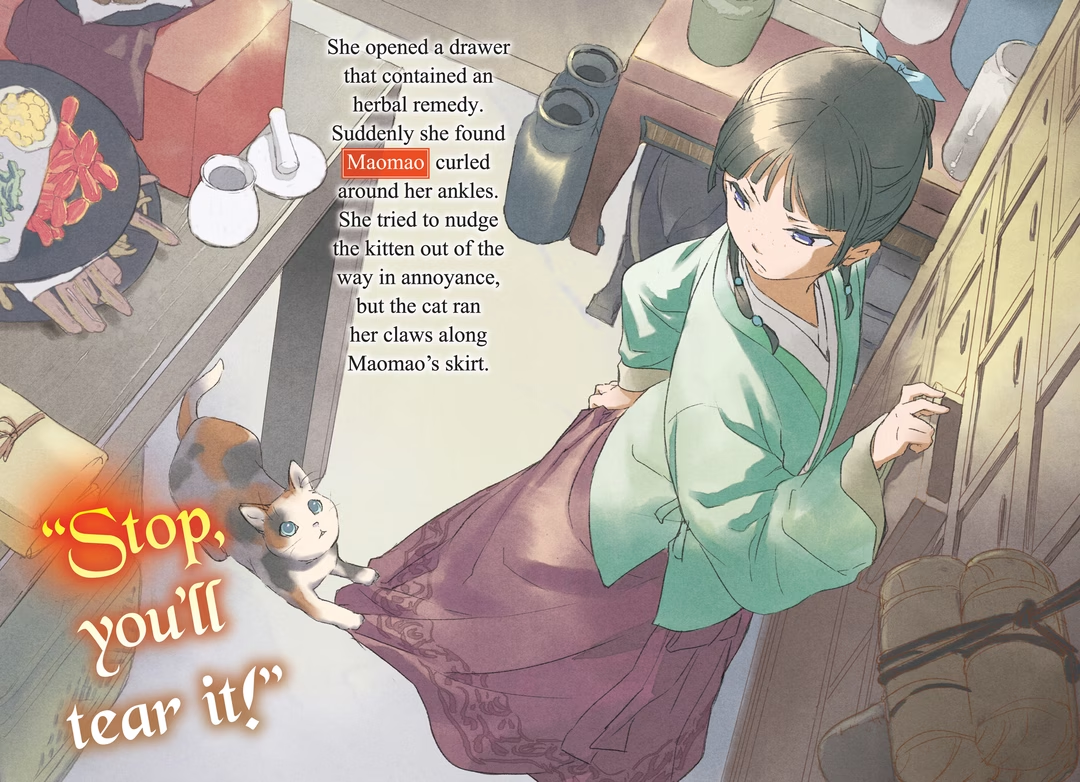

In the medical office, Maomao the kitten was wrapped around the quack doctor’s leg, pleading for a fish. As usual, the office was open but singularly lacking in patients. Maomao (not the kitten) was there researching herbs that might serve as anesthetics.

The moment she’d returned to the rear palace, she’d asked the doctor about the procedure for making eunuchs. She’d learned a bit from her old man, but not enough. She’d hoped to learn more from the quack doctor, but true to form, he wasn’t able to tell her anything her father hadn’t.

“At it again, young lady?” he asked. His lips were pursed and he wore a dejected look.

Maomao (the kitten) was easily able to bat the fish out of his hand and steal it away. Perhaps thanks to her improved diet, her fur had grown lustrous; it really would make a wonderful brush, but thus far Gaoshun and the doctor had prevented Maomao from plucking any of the kitten’s hair.

“They don’t make eunuchs anymore. No need to learn how to do it.” His expression turned distant. It must have been terribly painful.

Maomao had a thought. “How do the eunuchs get into the rear palace?” she asked.

The doctor dangled a stalk of foxtail for the kitten to swipe at as he replied, “How? Well, they undergo the surgery to become eunuchs.”

“No, that’s not what I mean.” She wanted to know how they were determined to be eunuchs.

“Time was, they’d let you in if you had written proof that you’d undergone the surgery. But now...” The quack flushed and ducked his head, a bit embarrassed. He acted almost as unworldly as Lishu. “These days they, uh, feel them. To see if anything’s there or not.”

“Do they grab at it?”

“What a question, miss,” the doctor said, exasperated. Such inspections hadn’t been the practice in days past, but there had been too many cases of people attempting to pass themselves off as eunuchs, and so the checks had been implemented. “People forged the documents, or got proxy papers. Some people will do anything for a few coins.”

The inspections were conducted by three officials, each representing a different department of the government. Before, the doctor told her, they’d conducted visual inspections of the would-be rear-palace entrants, but some of the officials found themselves rather discomfited by the process and so it was done away with.

Huh? Maomao cocked her head in curiosity. “They only conduct this inspection the first time a eunuch enters the rear palace?”

“No, each time you arrive, in principle. Though once they come to recognize you, they usually let you right through.”

Maomao didn’t say anything immediately, but continued to lean her head to one side as she gazed at the anesthetic herbs. Maybe... But she shook her head: no. The doctor, meanwhile, turned from the kitten and changed the subject. Sort of. “Speaking of eunuchs, did you know some new ones have joined us?”

“I’ve heard rumors.”

“Yes, younger men for the first time in quite a while. I think they’re proving quite a distraction!” He touched his loach-like mustache and sighed. Usually, becoming a eunuch cost a man any specific signs of masculinity, but in some cases, like the quack’s, a mustache or the like might remain. It was perhaps the doctor’s one source of pride.

Young women, particularly the more innocent among them, were often fastidious about cleanliness. They preferred eunuchs, with their almost gender-neutral appearance, to men with too much body hair or intimidating demeanors.

“The fuss is extra big this time because there’s a lot of pretty ones,” the doctor went on. “Right now they’re still behind the scenes, so it’s all well and good, but if one of them proved capable enough to be elevated to a higher position, it could be a real problem. I hope things calm down before then.”

Funny how the quack sounded like none of this concerned him, when he was the one on tenterhooks every time Jinshi was around. Then, too, if he could already comment on the eunuchs’ appearance, he must have gotten a look at them right after they were checked.

“I heard there was quite a scene when one of the lower consorts got too interested in one of the new eunuchs as he was heating the baths.”

“Hmm. I suppose such behavior can’t be ignored,” Maomao said. The lower consorts rarely had any hope of attracting the Emperor’s attention. The occasional unsatisfied woman wasn’t a rarity in the rear palace. No doubt there were a few palace ladies who had taken eunuch lovers.

Tough life, Maomao thought as she began to clean up the herbs.

○●○

“When are you going to tell her?”

It was the umpteenth time he had asked. Jinshi glared across at his attendant. “In good time.”

“Oh, yes! ‘In good time.’ Of course.” Gaoshun was standing beside the desk in Jinshi’s office, acting studiously unmoved. Well, his brow was furrowed, but that was typical for him. “I understand how nervous you are, but you’re acting a bit too overt about it, and it’s making things worse.”

“...With any other palace woman, that would be enough.”

“Xiaomao appeared as if she were looking at a snail that had lost its shell!”

In other words, a slug?

“Pipe down already,” Jinshi grumbled. He looked at the papers, separated them into the feasible and the infeasible, and began applying his chop.

There was no one else in the office. The soldier standing guard outside was probably yawning to himself. The place was set up so that they would know the moment anyone approached. It was only under such circumstances that Gaoshun would speak to him of a matter like this.

“I know.” Jinshi slammed his chop down, then passed the bundle of papers to Gaoshun. The other man accepted them without a word, straightened them, and placed them in a basket that an underling would take away.

“You have to make your decision soon, or it will come back to haunt you,” Gaoshun said.

“Are you sure it’s not better this way?”

Jinshi knew perfectly well what Gaoshun was thinking. He was suggesting Jinshi should bring the apothecary girl, Maomao, completely into his fold. Meaning...

“It would bring the strategist out of the woodwork, I can tell you that,” Jinshi added. He could see it now: the monocled man sticking his nose in. He was crazy about his little girl. And he was an unknown quantity, someone even the Emperor had to keep one eye on.

“Then fight poison with poison, as it were,” Gaoshun said calmly.

Lakan, “the strategist,” occupied a unique position within the palace. Though he officially held the title of Grand Commandant, he belonged to no particular faction, had formed no new faction himself, and drifted here, there, and wherever he pleased. He was the nail that stuck up, and ordinarily he would long ago have been pounded down—but he hadn’t been.

The man who had wrested back his inheritance from his blood father and half-brother something more than ten years before to now lead the La clan was a warrior fully worthy of the name. His astonishing genius had powered a meteoric rise through the ranks. Many had no doubt regarded him as an eyesore, and more than a few—so one heard—had tried to knock him off his perch. But it was Lakan who had survived. He did more than burn those who had tried to stop him; one man had even found his entire family scattered to the winds. The frightening thing was that neither rank nor blood intimidated Lakan.

There was no telling what was going on in that man’s head. But he could see things that others couldn’t, and use them to write a script that dragged his opponents down to the utmost depths.

There was, therefore, a tacit understanding among the inhabitants of the palace that one did not have anything to do with Lakan unless it was strictly necessary. If you didn’t hurt him, he wouldn’t hurt you. But having nothing to do with him also meant not making him your ally.

“All my papers would get covered in grease,” Jinshi said, remembering how Lakan hadn’t hesitated to eat oily snacks in his office.

“We would just have to live with it,” Gaoshun said, adding another crease to his brow. Truth be told, he wasn’t thrilled about the method, but it remained that he wanted to tell Maomao the truth. Ignore lineage and let her know what was really going on. Why she and they were in the position they were in, and why they’d had to hide it. Yes, he wanted her to know the truth. But at the same time, he was mildly terrified of how she might react.

Jinshi let out a long sigh and decided to get started on his next job. This was rear palace work, written requests submitted by the consorts to the master of the place.

“Seems to be quite a few of them today.”

“Yes,” said Gaoshun. “The usual matter, I presume. Perhaps along with items related to events the other day.”

The seals were already broken. He, or perhaps another official, must have checked them over once already.

Jinshi opened the first missive and gave it a quick look, then picked up the second. As he looked at a third, and then a fourth, he gradually settled into his chair, until he found himself gazing up at the ceiling, pressing the spot just under his eyes.

A good half of the material concerned just one of the four ladies, Loulan. The grievances were various: She had too many ladies-in-waiting compared to the other palace women. Her outfits were too gaudy and sullied the palace’s scenery. These were familiar complaints, motivated in large part by jealousy. Nothing new.

Aside from that, there was a report that some of the palace ladies were looking at the new eunuchs with romance aforethought.

“I could have seen that coming,” Jinshi muttered.

“Yes, sir.”

The newly arrived eunuchs had all been assigned to behind-the-scenes work: heating the bathwater, cleaning the laundry, and other jobs that mostly involved simple strength. The number of eunuchs had gone down in proportion to the number of palace women, so physical labor was considered a priority in the eunuchs’ tasks. If any of them showed any special aptitudes, they might later be transferred to some department that could use their skills, but these people had once been slaves of the barbarian tribes; due care was necessary. As for the women, their ardor would cool in time, but for form’s sake, he would have to keep an eye on things for now.

“What a headache.”

“Life goes on, sir.”

It was with many an exchange like this that Jinshi finished his paperwork.

Thus it was that Jinshi arrived at the rear palace the next day to observe the new eunuchs.

He asked the person who oversaw daily tasks in the rear palace about how the new arrivals were doing—heating the bathwater and doing the laundry both required well water, after all. As they spoke, Jinshi looked around.

He saw five people he took to be the newcomers; as they hadn’t yet been assigned to a specific department, they all wore white sashes. They were younger than the other eunuchs, but their faces were drawn, perhaps bespeaking their time in slavery. They seemed withdrawn, maybe likewise a legacy of their stay with the tribes. The way they scuttled fearfully about suggested they’d been under the barbarians’ thumb a long time.

Jinshi and the current Emperor concurred in their desire to reduce the staff of the rear palace, but this was another aspect of that issue. These people, having been castrated and enslaved, would take some time to adjust to having their freedom again. In a way, having them serve at the rear palace was the best way to help them adjust.