Character Profiles

Maomao

An apothecary in the pleasure district. Normally rather unemotional, she becomes a different person where medicines and poisons are concerned. Daughter of a courtesan and the military strategist Lakan.

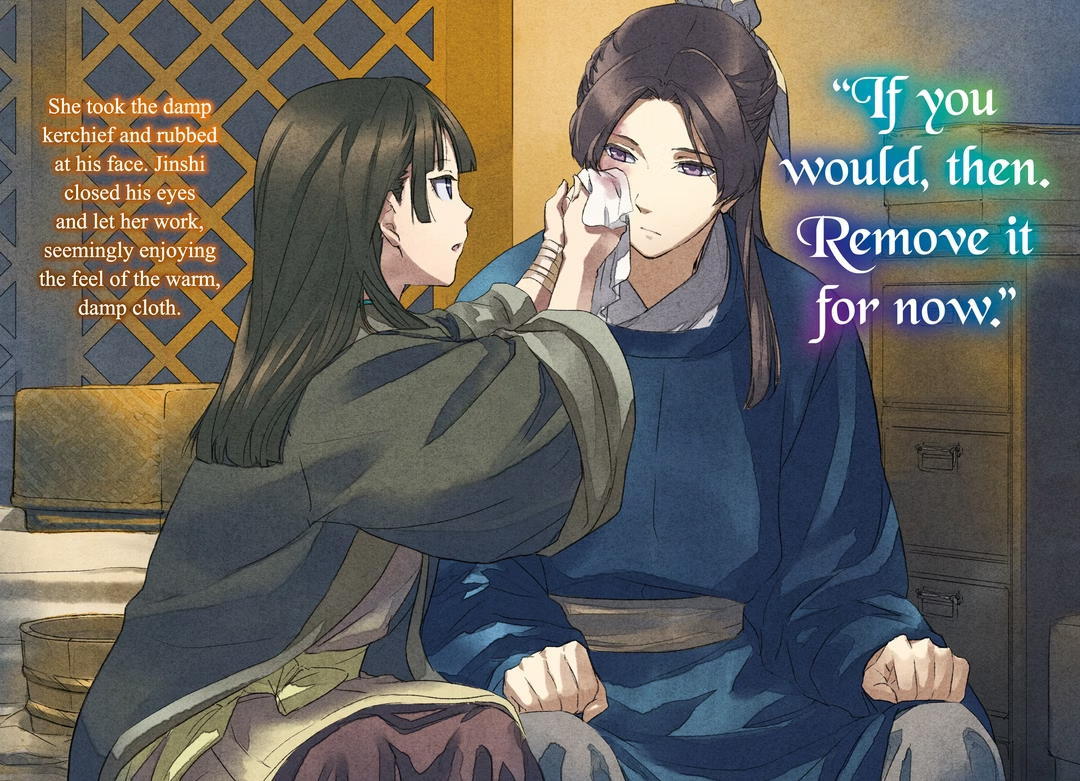

Jinshi

Played the part of a eunuch in the rear palace, but his true identity is the Emperor’s younger brother. Secrets surround his birth. So beautiful that some people claim that if he were a woman, he could bring the country to its knees.

Gaoshun

Formerly Jinshi’s attendant and minder. Now that role is played by his son, and Gaoshun serves the Emperor personally.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant.

Lakan

Maomao’s father. An eccentric military strategist who wears a monocle. Extraordinarily capable, but not easy to deal with. He’s up to his ears with love for his daughter, but Maomao hates him.

Lahan

Maomao’s cousin. Actually the son of Lakan’s half-brother, but Lakan has adopted him. Another eccentric.

Luomen

Maomao’s granduncle and adoptive father; an extremely accomplished physician.

Consort Lishu

One of the Emperor’s four most favored consorts. Very young and still timid.

Ah-Duo

Formerly one of the Emperor’s four favored consorts. She had a son with His Majesty. Once...

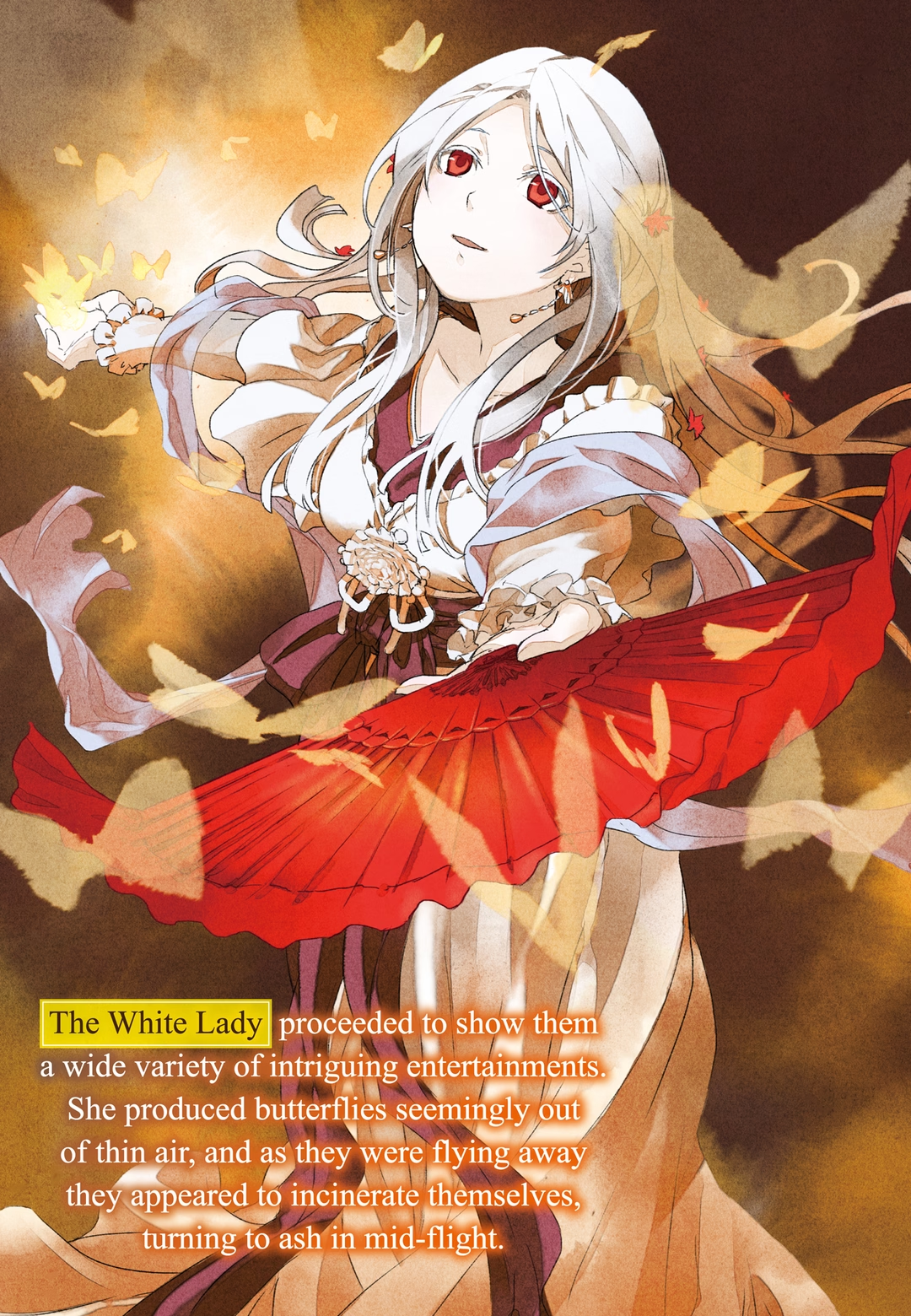

Suirei

Granddaughter of the former emperor, and a survivor of the otherwise exterminated Shi clan. Possesses knowledge as an apothecary.

Loulan

Also known as Shisui. Half-sister of Suirei. Formerly one of the Emperor’s four favored consorts. A member of the Shi clan, she fled the rear palace, a serious crime. It’s currently unknown if she’s alive.

Empress Regnant

Mother of the previous emperor, grandmother of the current Emperor. A powerful woman who conducted politics in place of her son; however, dark rumors persist about her. Deceased.

The Former Emperor

A variety of ugly names for him circulate: he’s called the Idiot Emperor, the Fool Prince, and a pedophile. Deceased.

Empress Gyokuyou

Hails from the west. Formerly one of the Emperor’s four favored consorts, now his empress. Has one son and one daughter with the current Emperor; her son is the current heir apparent.

The Madam

The old lady who runs the Verdigris House, the brothel where Maomao has her shop. A real miser.

The Three Princesses

Pairin, Meimei, and Joka. The three most popular courtesans at the Verdigris House.

Chou-u

A child survivor of the Shi clan. Because he was given the “resurrection drug,” half his body is paralyzed and he’s lost his memories of everything before he took the medicine.

Lihaku

A soldier-acquaintance of Maomao’s. Head over heels in love with Pairin.

Prologue

“Geez, how are you gonna survive if that’s all it takes to send you running?”

The voice was friendly enough, but its owner was looking down at him where he was collapsed on his knees on the ground. He could see the youthful figure on the fence, holding an apple. The figure took a bite of the hard fruit with a flash of white teeth. Why? thought the boy on the ground. He’d disappeared among the trees, eluded his pursuers—so why could this kid find him so easily?

“Shut up. I know that.”

“Better go back, then. You’ve got the serving women crying.” The youth chuckled.

So it had come to this: being looked down upon from the lofty heights of the fence. It made him so mad. What about you? he wanted to ask. Wearing a commoner’s outfit, clambering on the fence like a monkey, munching on an apple. Forget crying—if the serving women saw that, they would faint.

“It’s an important job. Just do it already.” Monkey jumped down off the fence and stood in front of him, then mussed his hair—as if the kid had the right! Monkey was only a year older than him. He pushed the hand away, hating to be treated like a child. The other youth laughed and wiped the half-eaten apple on a sleeve, then held it out.

“Your leftovers?”

“Hey, you don’t have to eat it.”

There was a pause, then he grabbed the apple and bit into the side that didn’t have any teeth marks in it. The crunchy fruit flooded his mouth with its flavor, simultaneously sweet and sour. He looked up to see the kid in the commoner’s garb grinning at him.

“I want to at least choose my own partner,” he said.

“Not likely! You get all the nicest stuff—what if you picked somebody awful? There would be a lot of unhappy people.”

“She was older than my mother!”

“Er...yeah, I don’t know what to say about that,” Monkey said shyly, looking genuinely unsure.

He knew that. Yes, even he knew that much. But he was still a child, so acceptance didn’t come easily.

“Grow up,” Monkey said.

“You’re one to talk! You’re only a year older than me.” What, you think that makes you a grown-up? he wanted to ask. Did it mean Monkey would be able to go calmly along with a match like that?

All right, fine.

“I’ve decided,” he said.

“Decided what?”

He raised his finger, then pointed directly at the faux commoner.

“My partner for tonight.”

“Excuse me?” A sardonic smile, meant to hide embarrassment.

Chapter 1: Locusts

Morning was a lazy time in the pleasure district. These caged birds had been singing till dawn, and when the customers finally went home, the obsequious masks came off. For the brief time until the sun was high in the sky, they would sleep like logs.

Maomao left her little shack, yawning. In front of her, she could see steam rising from the Verdigris House—the menservants working hard to ready the morning baths, most likely. The chilly air prickled her skin—the sun was late in rising. Her simple cotton overgarment wasn’t enough to keep her warm, and she rubbed her hands together, her breath fogging in front of her.

It had been a month since she’d left the rear palace, and the new year’s celebrations had subsided. Her old man had stayed at the palace, hence why Maomao was here in the pleasure quarter.

Back in the shack, there was still a child sleeping—and Maomao resolved to leave him that way, knowing it was the only part of the day when he would be quiet. The boy’s name was Chou-u; he was a survivor of the otherwise exterminated Shi clan, and currently he was living with Maomao. (Long story.) The little shit supposedly came from a decent background, but Maomao almost found herself wondering whether he was really a son of luxury. He was astonishingly adaptable, to the extent that he could lie there, snoring away, in that drafty old hovel.

Oh yeah, Grams wanted to see me, Maomao thought. She could get some hot water from the Verdigris House while she was at it. In weather like this, you couldn’t go bathing in cold water. Shivering, Maomao stopped in front of the well and lowered the bucket, then started hauling it up again.

When she arrived at the Verdigris House, the courtesans had finished their baths and were having the apprentices dry their hair.

“Well, you’re early today,” said Meimei, her hair still glistening wet. She was one of the establishment’s “Three Princesses,” and also effectively Maomao’s older sister. The most prominent courtesans bathed first, so she was done already.

“Oh, hey, Sis. Do you know where Grams is?”

“The old lady’s talking with the owner over there.”

“Thanks.”

It was the elderly madam who ran the day-to-day affairs of the Verdigris House, but she didn’t own the place. The man who did stopped by about once a month to confer with the madam about the brothel, the courtesans, and anything else that might be on his mind. The owner was a man just entering old age, and he was totally overawed by the madam, who had known him since he was young. In fact, a few gossips whispered that he was the child of the madam and the last owner, but nobody knew the truth.

Running a brothel wasn’t the man’s only concern; he had other, more legitimate businesses as well, and at first glance he looked perfectly ordinary. He was such a soft touch that one wondered if he was really safe being a part of this world—and one worried for the brothel’s affairs if the old madam should ever leave them.

“He’s not here with another of his bizarre business ideas, is he?”

“Who can say?” Meimei shrugged expansively.

At that exact moment, the madam’s voice boomed around the building: “You idiot! You complete, total, utter fool! What do you think you’re doing?!”

The sisters looked at each other. “Guess you were right,” Meimei said.

“Guess so.”

What was the man up to this time?

A few minutes later, the madam emerged from an inner room. The nearly elderly man, looking thoroughly cowed, followed her. Everyone called him Mr. Owner. It was the only way to remember who actually did own the place. Considering the way Mr. Owner was rubbing his head, it looked like he’d gotten a good rap from the madam’s knuckles.

“Oh, Maomao, you’re here,” the madam said.

“Yeah, Grams, I am. You asked me to come, remember?”

“Yes, of course.”

Dammit, she forgot. Maomao was sure she had only said the words to herself, yet the next instant, she felt knuckles smacking into the top of her head. Sometimes she wondered if the old lady wasn’t actually a mountain spirit who could read minds. Mr. Owner gave Maomao a look of sympathy. He kind of reminds me of the quack...

If she was having a little déjà vu, maybe it was because the two men actually looked somewhat similar.

“I know that look. You want to take a bath. And have breakfast too, I suppose? Bring the kid with you.”

“Someone’s in a good mood.”

“I do have my days,” the old woman said, then all but strutted over toward the kitchen.

“I’ll, uh, show myself out, then,” Mr. Owner said, and promptly did just that. Too bad, Maomao thought, watching him go. He usually stays for breakfast.

No one said a word. Everyone in the dining area was struck dumb.

Finally Pairin, sitting beside Maomao, announced: “Awful.” Her face was a scowl of disgust. She was considered one of the three most lovely flowers to bloom at the Verdigris House, but if any of her callers had seen her with that look on her face, all their fantasies would have been dashed.

As for Maomao, she looked like she’d found a maggot in her drinking water.

The table was long enough to seat about twenty people, and everyone had a bowl full of congee, another of soup, and a third small bowl, while three large trays were placed at intervals along the table. At the Verdigris House, meals usually consisted of a single bowl of soup, and maybe, if you were lucky, a modest side dish. Today the small bowls contained raw fish and pickled vegetables, while two of the trays had separate side dishes in them—a very generous breakfast by normal standards.

Something dark glinted on the trays. Bugs normally treated as pests in farmers’ fields were here being served as food. Locusts.

“Grams, can you explain this?”

“Shut up and eat. It’s a gift from Mr. Owner.”

Maomao could well understand why the old lady was upset. Mr. Owner had other business concerns besides running this brothel—legitimate businesses that allowed him to hold his head high in polite company. But he could hardly be called a talented businessman.

“The harvest was bad this year. I guess they wept until he gave in.” The madam angrily poured some black vinegar on her congee.

Mr. Owner dealt in crops. Farmers in this nation gave part of their harvest as tax, and the state purchased another part of the yield. Mr. Owner’s business involved trading in what was left.

“I don’t care if they cried their eyes out. What was he thinking, letting the seller dictate the price? He won’t be able to sell this stuff either. And look at it all!” A mountain of fried locusts towered on the tray, seasoned as best as could be managed with soy paste and sugar. “He said he’d bought too much, that they wouldn’t keep and would go to waste. Then he ought to just throw it out, instead of using sugar on it!”

Sugar was expensive! And here he’d cooked bugs in it. Who was going to eat that? No one, that’s who. That’s why he had so many left over—and how they had made their way to the Verdigris House’s table.

Mr. Owner had considered eating the costs himself, so to speak, but he had another concern: he had a wife who didn’t think highly of the Verdigris ladies’ profession, and he had evidently chosen the madam’s knuckle over his wife’s rage.

Maomao scratched the back of her neck. She was used to less-than-refined food, but even she wasn’t eager when confronted with this mountain of insects. After two or three of them, she would be ready to declare herself full. And the courtesans, far less accustomed to such base fare, frowned openly and refused to even touch the bugs.

“Hurry up and eat! You won’t shut up about wanting side dishes; well, here you go. Five each—eat up,” the old woman growled. Everyone looked at each other, and finally the first pair of chopsticks reached out toward the large dish.

Well, now. Maomao was surprised by the first person who put one of the locusts into their mouth. As they chewed on the bug, though, an unmistakable look of revulsion came over their face. “It’s not very good. It’s kind of...crunchy. Like it’s empty.”

This unvarnished assessment was given in a high-pitched voice—for it belonged to Chou-u. Maomao had been sure that the young lordling with his pampered upbringing would have resisted the idea of ever putting such food in his mouth, but apparently that wasn’t the case. Maybe the loss of his memories had taken any aristocratic inhibitions with it, or maybe he’d actually eaten something like this before. Or perhaps it was simply a child’s adaptability at work.

“Wow, I’m amazed you can stomach that,” said Pairin, who was sitting beside Maomao.

“It’s not great, but it’s not like you can’t eat it. It is super crunchy, though.”

Crunchy? That made some sense: you removed the innards of locusts before cooking them, so they were hollow on the inside. Hence Maomao really thought nothing of it as she reached for a locust and unenthusiastically took a bite.

Hrk?!

Yes, it was crunchy, all right. It seemed far more hollow on the inside than the locusts she’d had before, even though this one had been simmered. Maybe it was because the carapace was the only thing in her mouth, an outer layer even emptier than your average locust preparation.

Chou-u was busy bargaining with Pairin: “You want me to eat yours? I’ll help you out if you give me a mooncake.” Maomao got a firm grip on his head and shoved him down in his seat. “Ow! Owowowow!” Chou-u yelped.

Maomao took one of the locusts in her chopsticks and glowered at it. It was her bad habit: once something had gotten her interest, she simply couldn’t let it go.

“I want you to do a little shopping for me.”

After breakfast was over, the madam finally remembered why she’d summoned Maomao in the first place. She wanted to send her on an errand to the market that occupied the city’s central thoroughfare.

The courtesans weren’t allowed to leave the brothel, but the menfolk around here were too dense to trust with the shopping. There were a lot of strange and unusual products available at the market, but there were also a lot of con artists looking to rip you off. The market was a cheap place to sell things because one didn’t need to maintain a storefront, but by the same token, there was nothing to identify the bad actors and places to stay away from. You had to have your wits about you to find worthwhile purchases.

“I want you to get some incense. The usual stuff,” the old woman said. She meant the mild incense that was always burning in the entryway of the Verdigris House. It was a consumable, so she wanted to get it as cheaply as possible, but she couldn’t be burning low-quality stuff at the door to her establishment either.

“Yeah, sure. What’s it worth to you?” Maomao stuck out her hand, but the madam only smacked it away.

“Breakfast and bathwater for two people. Sound fair?”

Damn stingy old hag, Maomao thought, but she went.

“Heeey, Freckles! Buy me one of those!”

“Absolutely not.”

Chou-u was pointing to a stall full of toys as Maomao hauled him away, pulling him by the sleeve. She’d fully intended to do the shopping alone, but the little shit had thrown himself on the ground and begged and tantrumed until, in the end, she’d had to take him. Now she was walking through the market, dragging him along.

A single huge street cut through the center of the capital; carriages ran back and forth along it, and at the far end was the home of those who lived “above the clouds,” the palace. Every day, the street hosted a thriving market. To see the palace from here sometimes made Maomao feel as if she’d only dreamed that she had ever worked there. But the very fact that Chou-u was with her now was proof that she had lived within its walls—for that was why she’d found herself embroiled in the chain of events that had brought him to her.

The Shi clan rebellion had impacted the market as well, to a point. The northern regions produced grain crops and timber products, and Maomao couldn’t shake the sense that fewer places than usual were selling such things. Instead, she saw a lot of the dried fruits and textiles that came from the south and west.

There was something else too—something that brought a scowl to Maomao’s face when she saw it: simmered insects for sale. Locusts again.

“I guarantee that stuff sucks! Who would actually buy it?” Chou-u said, causing Maomao to slap her hand over his mouth and drag him away, the stall owner glaring fearsomely at them as they went. “What’d I do?” Chou-u demanded. “It’s true, isn’t it?”

“Just shut up,” Maomao said, looking at him almost as grimly as the shopkeeper had. This, she thought, was why she hated children.

“Hollow shells like that are never going to be good.” Then Chou-u said, more quietly, “Man, so much for the harvest this year.”

Maomao blinked. “Wait... What did you say?”

“Uh, that that stuff’s gonna suck?”

“No, no, after that.”

Chou-u looked at her curiously. “That the harvest is toast this year?”

“Yes! How do you know that?”

“Um... Uh... How do I know that?” Chou-u scratched his head with his right hand; his left hung limply at his side, spasming occasionally. For Chou-u had died once and come back to life, and it had left him partially paralyzed and without most of his memories. “I don’t remember. I just remember hearing that when the bugs are crunchy, it means the harvest will be bad.”

He held his head, hmming thoughtfully. Maomao wondered if a good shake might bring something back, but he was technically on loan to her, so she didn’t want to be too rough with him. If what Chou-u was saying was true, though, it could be a serious matter. She smacked him on the forehead, just hard enough to keep him from getting any stupider. He puffed out his cheeks in protest.

“You know, I think I might be able to remember,” he said.

“Really?” Maomao asked, and Chou-u quickly looked around at the nearby shops.

“Yeah! If you buy me something, I’ll remember!” he said, looking perfectly satisfied with himself.

Maomao didn’t say anything, but pulled the corners of Chou-u’s mouth as far apart as they would go. In the dumb gap in his front teeth, a new tooth could just be seen coming in.

Once a little shit, always a little shit, Maomao thought. Remember, my ass.

Chou-u was drawing happily despite the lump on his head. To Maomao’s surprise he had wanted not some sort of toy, but paper and a brush. She’d agreed to let him use one of her brushes, but the paper had ended up being surprisingly expensive. Maybe something of his decent upbringing remained with him, because he could tell the difference between low-grade paper and the fancy stuff. He’d gone around the shop, mumbling, “This is no good,” and, “That’s no good,” until he found the most expensive paper on display.

Of course, Maomao wasn’t about to let him boss her around like that, and instead picked something which, although not as nice, was perfectly usable. Paper was expensive for a consumable, but not impossibly so. She hoped that as it became more common, it would also get cheaper. Chou-u looked so happy clutching his sheaf of paper that she decided to forgive him with just a single knuckle to the head.

Chou-u had been drawing busily since they’d gotten back to the Verdigris House. He was in the shop with Maomao, where she was busy making the abortifacients and cold medicines she’d been asked for. She’d been told to keep him close so he wouldn’t cause trouble for the apprentices (some of whom were about his age) or the courtesans.

When she came back from delivering the medicines to a nearby brothel, she discovered a crowd at the entrance to the Verdigris House. Courtesans, apprentices, and even some of the menservants were there.

What’s going on? she wondered, squinting to see better—whereupon she discovered that the crowd had formed around her obnoxious brat. Wondering what he had done this time, she hurried over to him, the crowd parting until she was standing in front of the little shit. She discovered a piece of white paper with lines dancing across it.

“Don’t cut, Freckles. You have to wait in line like everyone else.”

“What are you doing?”

Chou-u was sitting with a flat board in lieu of a table, drawing a picture. In front of him, a courtesan sat in a chair, looking as calm and composed as she could.

“Can’t you tell? I’m drawing a picture.” The brush ran fluidly over the page, producing something resembling the woman in the chair, if more beautiful. “There! All done.” Chou-u left the brush in the pot of ink and gave the paper a few good shakes. The face of his “model” broke into a smile and she said, “Well, now!” as she pulled out her wallet and gave him five coins—and not small ones.

“Pleasure doing business,” Chou-u said, tucking the money into the folds of his robe. The sum was considerably more than some kid’s pocket change.

“Ooh, I’m next,” one of the menservants said, sitting in the chair. Wasn’t he supposed to be on guard duty or something? What was he doing playing around here? If the madam saw him, he’d be in for it.

“Aw, sorry, mister. I’m all out of paper. I’m gonna go buy some more right now, though, so stop by tomorrow, okay?”

“Bullshit! I’ve been waiting all day!”

“Really sorry, sir. I’ll do you first thing tomorrow. I’ll make you look extra manly!”

He was pretty good at this. Chou-u slipped away from the crowd and started hurrying toward the paper shop. Maomao recalled buying him a sheaf of ten sheets—and it was already gone? At least three of the people standing around appeared to be holding portraits; at his prices, that would already be enough to recoup the investment in materials.

Who knew he had a talent like that? Maomao thought, scratching the back of her neck and stealing a peek at the page a nearby courtesan was holding.

“You louts! What’re you doing?!” The sound of the madam’s raspy voice was enough to banish the burble of friendly chatter and turn all the faces pale. “Hurry and start getting the place ready! You want the customers to run away?”

There was the madam, brandishing a broom. The courtesans and apprentices and menservants scattered like baby spiders. Maomao was about to make tracks for her own place when she was grabbed by a skeletal hand.

“What is it, Grams?”

“You know damn well what it is! It’s that kid! You might have agreed to take him in and you might be getting a stipend to support him, but you can’t just let him do whatever he wants!”

“You’re the one getting all the money, Grams.”

Yes, for some reason it was the old lady who kept all the funds that came in. It had something to do with the fact that Chou-u was, to an extent, given free rein of the Verdigris House. But a man—even a child—couldn’t be allowed to actually live in the brothel, yet neither could he be housed in the menservants’ longhouse. By process of elimination, he was put up in Maomao’s shack.

“He’s using my facilities. He owes me a cut of the profits. I’ll let it go at ten percent.”

Greedy old hag.

Maomao didn’t think she’d said the words out loud, yet mysteriously, she found a knuckle cracking down on her head.

“You, clean up that brush and inkpot.”

“Why me?”

“Don’t question me. Just do it. Or it’s locust soup tomorrow.”

Hag! Maomao thought, but she sullenly began to clean up, pressing one hand to her head all the while.

When Chou-u got back to their shack that evening, Maomao looked at him in a way that showed she was not pleased.

“Freckles, where’s my brush?”

“No brushes for boys who don’t clean up after themselves.” Maomao pointedly turned her back on him and put some wood in the cookstove.

“Don’t be stingy with me!”

“If I’m stingy, I learned it from the madam.” Maomao stirred the congee in the clay pot on the stove, tasting a sip of it. She concluded it was a little bland and added some salt. “Who, by the way, says she’s going to charge you for using her place.”

“I know! I’m gonna do my portraits somewhere else from now on.”

That caused Maomao to frown. She perched the ladle in the soup pot, then went over and stood in front of Chou-u, who was lounging on the rush mat on the floor. She crouched down and looked at him.

“What?!”

“You stay close to the Verdigris House. I don’t care if she charges you for it. You’re not to get too far away from the guards. And no more going by yourself to buy paper.”

“Hey, I can do what I want.” He tried to look pointedly away from her, but Maomao grabbed his head and forced him to look in her eyes.

“Yes, you can do what you want. If you don’t mind ending up as a lump of meat.”

“Lump of meat?” Chou-u looked at her.

She wasn’t joking. The Verdigris House was boisterous and friendly, but this was still the pleasure district, and the seamy underbelly of the capital was always near at hand. Maomao pointed out the window of the shack. “You’ll end up with the likes of her.”

The light of a lantern could be seen almost floating through the evening darkness. It was held by a woman, who was hooded and carrying a rush mat. She looked ordinary—at first. But then Chou-u caught his breath and stood abruptly. He must have noticed that this night-walker had no nose. She had no proper home, either, but could only take customers by the roadside. Women like her, the lowest of the whores, were often physically ravaged by sexual diseases. The woman outside didn’t look long for this world—but if she wanted her next meal, she would have to find a man to service.

What was she doing around here? Maybe Maomao’s old man, good-hearted as he was, had given her medicine once; or maybe she was looking for the leftovers from some other brothel. Whatever it was, Maomao thought, it was causing trouble for her.

“This isn’t a nice place,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re some little kid. There are people out there who would line up to kill you if they knew you had a few coins.”

In other words, if he didn’t want to die, he would do as she said. Chou-u pursed his lips a little, but nodded, his eyes brimming with tears.

“You understand? Then hurry up and eat your dinner and go to bed.” Maomao went back and stood in front of the stove again, where she resumed stirring the congee.

Chou-u was already up when Maomao woke the next morning. She could hear him bustling around, and looked up to discover the tabletop covered in paper. Chou-u was working his brush vigorously.

That little shit...

He was using the brush and inkpot she’d hidden from him. Maomao got up, about to give him a taste of her knuckle, when one of the pages came drifting down off the table.

Hm? Curious, she picked it up. It showed a bug drawn in precise detail. In fact, it was almost too real; it made her a little squeamish to look at. Brings back memories. It made her think of the young serving woman—no, the consort—who had loved insects. That young woman, Shisui, had done drawings like this too. Maomao felt a pang at the thought.

Suddenly, Chou-u stood up. “Done!” he said, presenting her with a piece of paper. “I finished, Freckles!”

“Finished what?”

“This! Right here!” He fluttered the paper at her, looking downright proud of himself. It showed two subtly different bugs. “I had a little trouble remembering exactly, but I think this is it. I think this is what I saw with the thing that talked about bad harvests.” Luckily, his pictures spoke far more articulately than he did; they were very clear. “This is your normal locust. And here on the bottom is a locust from when there’s going to be a bad harvest.”

The two locusts showed legs of different lengths, and although it was hard to tell in an ink drawing, the richness of their coloration might have been different too.

“Are you sure about this?”

“Pretty sure. It sort of came to me in bits and pieces.”

Chou-u was still largely amnesiac, but apparently he was recovering bits of his memory. That could be highly inconvenient depending on what he remembered, but it might prove very important too.

Two types of locust. Maomao would have to find out more about this. A plague of insects could destroy an entire nation when they ate all its crops. Insects were always a threat to crops, but plague was something else altogether. The bugs would devour anything and everything; in bad cases, they might even eat hempen ropes and straw sandals. Maomao didn’t know what caused such events, but they happened at least every few decades. By good luck, no such thing had occurred since the accession of the current Emperor.

Some people insisted this was because the current Emperor’s rule was humane and enlightened, thus heaven saw no need to send plague. But Maomao didn’t believe that for a second. It was just happenstance that there hadn’t been any plagues of insects. That meant, though, that if and when such a plague occurred, it would be a chance to test the Emperor’s power. He had only recently punished the Shi clan, the most powerful in the land. The timing could hardly have been worse: if a plague of locusts occurred now, many people would assume it was a heavenly rebuke for the destruction of the Shi.

Bah. Not my problem. Nothing to do with me, Maomao thought. No, it was nothing to do with her—but she was already moving.

Almost before she knew what she was doing, Maomao was heading for a particular bookstore.

No way they’ll have it...

Chou-u’s detailed drawings had reminded her: she’d seen such illustrations before. She walked among the shops until she reached one that was particularly gloomy and moldy-smelling. A bell chimed as she entered, and the owner, resting within like a piece of the furniture, nodded to her. That was as much civility as he was prepared to offer, after which he appeared to go back to sleep. The place looked deserted, bereft of customers, but she knew his purse must be comfortably full these days.

He supplies books to the rear palace, after all...

Most of the stock was either used books or for rental. There were a few brand-new items for sale, but not many. If you wanted something new, you would probably have to order it. The shop owner left these business matters largely to his children, living an almost hermetic life himself.

They’re not going to have it.

This shop specialized in popular fiction and erotic illustrations; not what one would call refined material. Maomao had come here nonetheless, because sometimes one could make unexpected finds in shops like this...

Almost as soon as she got inside, she rubbed her eyes. What was going on here? She frowned. What was this, some convenient plot twist? She pointed to a book sitting on a pile on a desk. “Hey, mister, can I have a look at that?”

“Mmm,” the shopkeeper grunted; Maomao took it for permission and picked up the book. It was thick and heavy, and the cover depicted a bird.

This is ridiculous. In fact, it seemed impossible. And yet, there it was. The book was filled with pictures of birds accompanied by descriptions, and there were handwritten marginal notes peppering the pages. “What’s the story with this thing?”

“Hrm? Got it in yesterday.” The clerk didn’t sound very excited. More like he wished she would stop interrupting his nap.

“Did you get anything else in along with it?”

“Only the one. But the guy said he would come back, I think.”

Maomao’s face began to sparkle. This was the second time she had held this book. Yes, it was exactly the same one she’d seen back then. Back in the chamber where she’d been confined. It was one of the books she’d been given as research material on the elixir of immortality—and here it was in her hands.

Chapter 2: Ukyou

Maomao wondered how this could be. Shishou’s stronghold was supposed to have been sealed off; it made no sense for something from there to be here. Even if the clan’s possessions had been moved out of the fortress, the fact that she had found one of them here in this marketplace implied some shady dealings somewhere along the line.

Hrrmm.

Well, if that was the game that was afoot, then Maomao had an idea.

She found the culprit quickly. And how? It was really quite simple.

“Young lady, you can’t call me all the way out here just for something like this.”

The annoyed speaker was Lihaku, and despite his complaint, he was eagerly trying to get a good look at the Verdigris House. They were in Maomao’s apothecary shop, Lihaku’s considerable bulk making the place feel even more cramped than usual.

“I don’t have time to go chasing after petty thieves,” Lihaku added, glancing toward the ceiling of the atrium, hoping to catch a glimpse of a countenance like a blossoming flower. Specifically, of Pairin, one of the Three Princesses of the Verdigris House.

Lihaku, a soldier and acquaintance of Maomao’s, was head over heels in love with Pairin. Coming to a brothel, however, took money—so Maomao, as a friend of Pairin’s, knew that Lihaku would come running whenever she might have a request to make of him. And today, her request was this: that he keep an eye out in the market for any stolen goods that might be circulating. Specifically, books.

Encyclopedias were unusual; if one had been stolen, it would be easy to trace when it was sold. And because the thief might go to any number of shops besides the used-book place Maomao had visited, she wanted Lihaku to be on the alert.

“Hah! Well, you’ll be glad to know I’ve been watching the place all morning.”

“You didn’t ask one of your subordinates to do it?” Apparently he’d been so set on making a good impression that he’d handled the matter himself. Given that it was still the cold season, it was a pretty good effort to stake a place out.

Lihaku handed Maomao a package. A gift of rice dumplings. He accompanied it with another glance toward the atrium. He seemed to be suggesting that he and Maomao should have tea together—and that she should call Pairin to snack with them. But Maomao still needed something from him first.

“Where’s your captive?”

“Out front. One of your guys is watching him.”

“Ah.”

Maomao looked out the window to see two of the brothel’s guards standing on either side of an emaciated, beardless man. He was wearing fairly heavy clothes—in fact, Maomao recognized the cotton-padded jacket. It was dusty and obviously hadn’t been washed in days, but she knew it.

Well, now... Where had she seen him before?

“Hey!” Lihaku called, but Maomao ignored him; she put on her shoes and headed toward the men. Flanked by the two large guards, the thief looked smaller than he actually was.

“Don’t get any closer. He’s dangerous,” one of the guards, a long-serving manservant, said, catching Maomao by the collar. She hated being handled like a cat, but this was how it had always been, ever since she was little. She didn’t bother squirming away, but only looked at the thief.

He didn’t say anything. She didn’t say anything. But their eyes met, and he studied her face for a second—and then he went pale. He opened his mouth, and what should he say but, “Snake girl!” He shouted so loud, he sprayed flecks of spittle.

“Hey, I think you mean cat girl,” the guard said teasingly. The other one laughed.

Oooh, Maomao fumed.

She didn’t have much memory for faces, and the man’s appearance was altered by his hollow cheeks, but she was almost sure he had been at the fortress. He was the one who had been guarding her room, the one who had helped her escape from the torture chamber. The one who had interrupted her delicious meal of snake meat.

At least it makes sense now, she thought. When he’d told her to run, that it was dangerous, he’d looked like someone who’d just looted a burning building. Since he’d been guarding her room, it would have been a simple matter for him to snatch the books out of it.

“What’s the matter, young lady?” Lihaku arrived on the scene and looked at the man, who trembled visibly. If they found out he was a runaway from that fortress, they’d treat him as something much worse than a thief.

Hmm. Maybe, Maomao thought, she could use that to her advantage. “I’m sorry, sir. He’s an acquaintance of mine.”

“Huh?” Lihaku said, taken aback by the bluntness of Maomao’s declaration. She smirked at the criminal.

Lihaku was clearly dubious, but when Maomao produced some snacks and called Pairin, he quickly went off wagging his tail. And so it was that Maomao was left in the apothecary’s shop: herself, the thief, and...

“Y’know, you don’t really have to be here,” she said, shooting a withering look at the long-serving manservant. Everyone else had gone on tea break, but this man had insisted on following Maomao. He’d cleverly helped himself to a handful of dumplings.

“’Fraid I can’t leave you two alone. If anything were to, ahem, happen, I’d catch hell from ‘Mr. Fox’ and ‘Mr. Mask.’” The fox referred to the monocled strategist, while the mask was presumably Jinshi, who covered his face whenever he came here. Even with his scar, he was still a valuable jewel of a man. His looks would make him stand out, and his position only complicated things. “Don’t worry about it,” the manservant added. “I’m just sitting here, eating dumplings. I won’t hear a thing.”

So saying, he went and sat by the wall. He was in his forties, and had been around the Verdigris House since before Maomao was born. He had earned the madam’s trust by always doing things diligently and accurately. His name was Ukyou.

He’ll squeal to the old lady. I just know it. In other words, she would have to restrict this conversation to things she would be comfortable with the madam knowing about. Stuff that won’t get us in trouble if she finds out...

Maomao looked at the man sitting across from her. Two books lay on the table between them: the one Maomao had found at the used-book store and the one the thief had intended to sell today. “What happened to the rest of the books?” she asked.

The man refused to look at her, like a recalcitrant child. It wasn’t a good look for a full-grown man.

I don’t have time for this. If he’d sold them at other shops, someone else might already have bought them. Maomao slammed a fist down on the table. “That soldier we saw? He was part of the assault on the stronghold,” she said, quietly, slowly. “Are you saying you don’t care if I tell him you were there?”

The man’s color got even worse. Maomao hated to threaten him after he’d helped her, but this was no time for scruples. She needed to know where those books had gone.

Ukyou munched thoughtfully on a dumpling, taking his time with each mouthful. He might look easygoing, but if things got physical, he was clearly strong enough to overpower the likes of this guy.

The man frowned, fighting with himself, but in the end he bowed his head, defeated. “I still have three of the other volumes. Two of them I sold in another town, and the rest I left.”

Assuming the fire from the explosions hadn’t reached Maomao’s room, it might still be possible to get their hands on those last volumes. That meant the real problem was those two books he’d sold. The ones on the table had to do with birds and fish, respectively.

“Did you sell the one about bugs?”

“No, I’ve got one of them still.”

One of them? That piqued Maomao’s curiosity. The volume about birds had a number on it. If there was a I, there must be a II.

“Can you get it to me, immediately?”

“Can you promise you won’t sell me out?”

“Depends if you’re willing to cooperate,” Maomao pressed. Ukyou, who had been reclining by the wall, could be heard to sigh deeply. “Come on, Maomao. Now you’re just threatening him.” He arranged himself on the cramped floor of the shop and gave the man a friendly smack on the shoulder. “Listen, you must be hungry, right? Looks like you’ve been through a lot. Why not relax?”

The thief didn’t say anything. Ukyou, meanwhile, simply left the shop. He was soon back holding a tray with a bowl of rice and a side dish. The side dish was nothing more than the leftover stewed locusts, but no sooner had Ukyou offered the man chopsticks than the thief took them. Maomao was surprised by the man’s enthusiasm.

Ukyou slapped her on the shoulder. “Not there yet.” The thief, virtually obsessed with his meal, didn’t even look at them. Ukyou dropped his voice and said to her, “Just look at him. I think he had a hard road to the capital. Maybe he did sell the books, but it looks like it was either that or starve. The books themselves seem to have been treated well. I don’t think he’s a bad person.”

“You might be right...” Maomao said, but she was absolutely dying to know what had happened to the other books.

“You have to know when to use the carrot and when to use the stick.”

“I know that, dammit.” If the old madam was the stick of the Verdigris House, this man seemed to be the carrot. He wasn’t notably tall, and his face looked like that of any other middle-aged man, but it was his decency that endeared him to the courtesans.

Suddenly, the thief stopped shoveling food into his mouth. Ukyou looked at him with curiosity. “What’s the matter?”

“This is awful.”

“You don’t like locusts?”

“This ain’t a locust,” the man said, holding one of the bugs in his chopsticks.

“Isn’t it?”

“They might call everything a locust around here, but farmers make a distinction.”

“What sort of distinction?” Maomao and Ukyou looked closely at the man. He went to work on the mountain of stewed bugs, picking them up one at a time and taking a bite, then separating them into piles. The ratio between the two ended up at close to eight to one.

“These are locusts. Farmers stew ’em and eat ’em. But these, these are grasshoppers. They look alike, but grasshoppers taste terrible.”

“Are they really that different?” Ukyou asked. He’d never realized the two were so distinct. Nor had Maomao; she’d always mentally classified them together.

“Take a bite, and you’ll figure it out. When you pull off the legs and stew them, they all come out the same color, so the less scrupulous sell them to ignorant merchants. Grasshoppers give real locusts a bad name.”

Ah ha. Mr. Owner would have made the perfect mark for a scam like that. With just one locust for every eight grasshoppers, of course the resulting dish was terrible. Maomao took a locust and put it in her mouth. The thief wasn’t wrong: it had more body and a better flavor.

The man gave the grasshoppers a grim look. Before Maomao could speak, though, Ukyou said, “If there’s something going on, tell us.”

The man said, “There might be a famine this year.”

At that, Maomao practically jumped toward him. “You think so too?!”

“H-Hey, now, I can’t be sure. But when you get a lot more grasshoppers than locusts in a year, it usually means a plague of insects the next season.”

It was a simple matter of the ratio between the two. And it accorded well with what Chou-u had said. Maomao gave the man another look. “You seem awfully knowledgeable about bugs for a guard. I also seem to remember that room had plenty of things in it more obviously valuable than a set of encyclopedias, yet you went for the books. Why not just leave them?” Wouldn’t a thief normally choose something easier to pawn?

The man scratched the back of his neck, somewhat abashed. “I actually, uh, didn’t want to sell the encyclopedias.”

“But you told the bookseller you’d be back with more later.”

“You have to schmooze with those types, otherwise you can’t get a decent price. Besides, I was hoping to come buy it back if I could scare up the money. I mean, nobody would voluntarily buy an encyclopedia.”

Ahem... Someone would, Maomao wanted to say, but she stopped the words before they came out.

The man obviously had only the clothes on his back to his name. It was still winter, so that was fine as far as it went, but his face was grimy; he was so dirty that Maomao had somewhat balked at letting him into the apothecary shop. In any case, he wouldn’t find it easy to earn much money looking like that.

“The guy who used to live in confinement, back at the stronghold. I was the one who brought him his meals.” Maomao’s eyes widened; this was unexpected. “I guess they brought him there to make some kind of new drug or something, but that wasn’t the only thing he was researching.”

“What else was there?”

“This, right here,” the man said—indicating the grasshopper.

“You mean how to prevent a plague?”

So that was what her predecessor had been trying to discover. Maomao swallowed heavily and was about to press the man further when there was a great crash and the door of the shop flew open.

“Hey, Freckles! Can I eat your dumplings or what?”

It was Chou-u, holding a skewer of dumplings in each hand.

The thief blinked several times. “Wha? Young Mas—”

Before he could get the words out, Maomao grabbed some medicine she’d been pulverizing and flung it into the man’s open mouth.

“Ugh! That’s bitter!” He practically convulsed. She felt bad for him, but he had been about to say something extremely inconvenient for all of them. She’d do it again if she had to.

I should have realized... Of course he would know about Chou-u. He’d said the whole reason he’d helped her was because Chou-u had asked him to. Publicly, the Shi clan had been destroyed root and branch. The fact that one of them was actually right here was bad, bad news.

Chou-u watched the man flail with evident amusement. He seemed to wonder what this ridiculous stranger was doing.

“Yeah, sure, eat the stupid dumplings,” Maomao said. “Just go away.”

“Don’t shoo me! What am I, a house pet?” Chou-u complained. He must not have recognized the man, because he paid him no mind.

“Hey, Chou-u, how about I let you ride on my shoulders?”

“Whoa, really? Awesome! Let me up!”

Maomao was grateful to Ukyou for his well-judged distraction.

I can’t be sure...but I ought to let him know, at least, Maomao thought, and crooked her fingers, counting the days until Jinshi would visit again.

Chapter 3: Sleep

Three days later, a masked noble appeared at the apothecary shop as the sun was crossing the meridian.

“Welcome! Thank goodness you’re here!”

Jinshi was set back on his heels by Maomao’s warm greeting. Behind him, Gaoshun’s mouth hung open; he was clearly wondering what had happened.

“H-Hey, what’s the matter?”

“Xiaomao, you do know that that’s Master Jinshi before you, right? You don’t have him confused with someone else, do you?”

Maomao scowled. Ridiculous reactions, both. Gaoshun glanced at Jinshi, knowing he’d accidentally let the wrong name slip, and was greeted with an annoyed look from behind the mask.

Jinshi entered the shop and seated himself on a round cushion. The place wasn’t exactly spacious, so Gaoshun retreated to the front room of the Verdigris House, as he always did. Once the sliding door was closed, Jinshi finally removed his mask.

There, as ever, was his beautiful face, and the scar along his cheek that never failed to look out of place. The stitches had been removed and it looked far less painful than before, but even so, it was enough to make a person sigh with regret for the sheer wastefulness of it.

People had started writing entertaining tales of the last year’s rebellion of the Shi clan. The hero was the Emperor’s beautiful younger brother, and the villain was played by Loulan. One might expect the latter role to go to Shishou, the leader of the Shi clan, but Loulan had displaced him in the popular imagination, and that scar, one might suppose, was the reason.

The villainess who had injured this unearthly face would be spoken of for generations to come. When Maomao remembered the bug-loving palace lady, laughing merrily, she found it gave her a desolate feeling.

“I thought you had something you wanted to tell me,” Jinshi said.

Oh! Yes, I did.

Maomao took the encyclopedia she’d bought down from the bookshelf.

“What’s this?”

“Some opportunist plucked it from the flames of the stronghold and sold it.”

She would keep quiet about the former guard for the time being. He was under the care of the Verdigris House’s chief manservant, Ukyou, who would know what to do with him.

The man who had fled the fortress had decided to start calling himself Sazen. Maomao had wanted him to use an assumed name just on the off chance his real one caused the little brat, Chou-u, to remember his past. Luckily enough, “Sazen” seemed to have no special attachment to his former name. Now he was learning the business from Ukyou.

We were able to recover the books he sold.

Ukyou had acted immediately to gather them up. Sazen said he’d sold them to a procurer with whom Ukyou happened to be acquainted, so the chief manservant talked to the other man and bought the books from him. Meaning there was just one problem left.

“I think the last of these books is at the fortress. And I want to get my hands on it.”

Jinshi gave her a look. “And why are we collecting these books?”

Maomao decided the best answer to that question was a practical demonstration. She placed a bowl of food in front of Jinshi with a none-too-elegant thonk: a mountain of stewed bugs of a rather unappealing color. Jinshi frowned openly and backed away. “What in the world are those?”

“Stewed locusts. Although the chief ingredient is actually grasshoppers.” Maomao picked one up in her chopsticks and leaned toward Jinshi. He backed away again, but soon found himself stymied by the wall, where he simply crumpled.

“I’m not eating that!”

“No one said anything about eating it.”

Maomao put the grasshopper on a plate and took out a piece of paper with a picture of two insects on it: a comparative study of a locust and a grasshopper. It had been based on the fried versions, but it captured the essentials. She’d given Chou-u some pocket change for the work.

“It seems grasshoppers proliferated last year. Weren’t there any complaints from the farming villages about damage from insects?”

Jinshi’s face clouded, and he scratched his head with a sigh. “Yes, we had some reports. There was significant damage to farms in the northern region.”

Not enough to cause starvation, though. For better or worse, autumn the year before had been cold, helping to take care of the bugs. They were wiped out before they could increase uncontrollably.

“Devastation from locusts can continue for several years. What do you plan to do this year?”

Jinshi’s mouth twisted. Maybe the question had already occurred to him.

The northern region had, Maomao suspected, largely belonged to the Shi clan. With them gone, responsibility for governing the area would fall on the Emperor.

“We’re planning to cover for last year’s shortfall by distributing some of the excess from the south.” But they hadn’t yet, it seemed, planned further ahead than that. Jinshi had a furrow in his brow worthy of Gaoshun.

“If it happens again this year, things are going to be hard,” Maomao said.

People would claim that the plague was a sign that the Emperor was not ruling the country properly. They’re just bugs, you might think, but such plagues had spelled the end of more than one nation in history. And for this to come the very year after the Emperor had destroyed the Shi clan—what would the people make of that?

Ridiculous superstition, Maomao thought—but in the minds of many, the connection couldn’t be dismissed so easily. And the Emperor and his relatives had to rule the credulous as well as the skeptical.

“Insect plague is a natural phenomenon,” Jinshi said. “What are we supposed to do about it? Set up bonfires to draw them off? Or should we go out and swat every single one individually?” He was right, of course. Such an endeavor would be futile.

“That’s why I’m looking into this,” Maomao said, holding the encyclopedia out toward Jinshi. This was the volume she’d gotten from Sazen, the runaway from the stronghold. The book was thoroughly annotated in the margins. “There’s another volume dealing with insects, and since it’s not here, I think it might be back at the stronghold.” The volume in Maomao’s possession said nothing about grasshoppers, yet it was unimaginable that such a common insect would go unremarked upon in such a thorough book. “Also, I believe the apothecary who was at the stronghold before me was researching something about grasshoppers.”

“Truly?”

“Yes, although I don’t know how far his research got.” Only that it had been desperate.

Jinshi stroked his chin thoughtfully, then opened the door and called for Gaoshun—who was just putting a skewer of dumplings in his mouth. He immediately went to summon one of the menservants from the Verdigris House. Chou-u, never one to miss an opportunity, spotted the abandoned dumplings and helped himself.

“I should be able to procure it within a few days.”

“I would appreciate that.” Maomao let out a long breath. This didn’t mean things were over, but it did bring some relief for something that had been swirling in her mind for some days now.

Jinshi, however, looked pale. He often seemed fatigued recently, now that he could no longer pretend to be a eunuch. And what Maomao had said had only added to his workload.

“Tired, sir?”

“You could say that. But I’ll be fine.”

He had big bags under his eyes, but the officials and court ladies around him didn’t seem to notice them. In fact, they seemed to think he was fine. Even with a scar on his face, his beauty was still virtually superhuman, and that threw people off. They seemed to take it for the bloom of health.

He’s going to collapse at this rate. People whose senses became dulled by fatigue eventually ceased to understand even that they were fatigued. If even Gaoshun were to insist that Jinshi was fine, there would be nothing she could do to stop any of it. He needs some sleep.

If he had the time to come all the way out here, he should have spent it resting in his room instead. Maomao looked at him with some exasperation. “Master Jinshi, wouldn’t you like to rest?”

“What’s this all of a sudden?”

“I’ll prepare a bedroom immediately. I want you to sleep.”

Maomao was looking right at him, and it was impossible to avoid noticing the scar on his right cheek. She realized she was at risk of wanting to study the neat stitching in detail, and dropped her gaze to the ground. Of course she would want to have a good look at her old man’s handiwork, the careful stitches covered with ointment. Jinshi would most likely be stuck with the scar, but the healing process would go quickly, and she wished she could observe its progress.

“You want me to sleep in a place like this?”

Maomao ventured a bit of a joke: “Can’t sleep on your own?” Thinking maybe he would resent being spoken to like a child, though, she started to add, “That’s a j—”

“No. No, I can’t,” Jinshi said before she could finish. It seemed he got lonely by himself.

I get it. Maomao popped her head out the door of the shop and called to a nearby apprentice, asking her in turn to call the madam.

“What is it?” the old lady asked, not very enthusiastically, when she arrived. But when Maomao explained what she wanted, a light started to shine under those baggy old eyelids. “Give me half an hour.”

Is that really enough time? Maomao thought, but she proceeded to leave the madam, who suddenly seemed quite invested, to her own devices. Instead she offered Jinshi some restorative tea.

“This way, please,” Maomao said, directing Jinshi into the Verdigris House. She led him to a room on the top floor, a chamber appointed with the finest furnishings and a very large bed. Incense was burning, filling the space with a rich, sweet scent. “You may rest here, sir. Work is important, but you must take care of yourself.”

She’d half expected the madam to simply shoot her down, but the old lady seemed to have had some sort of plan, for she offered the establishment’s best room for free. And she’d gotten it ready in thirty minutes. An impressive display. Maybe she’d figured it would be best to make a good impression on a member of the nobility.

“If you want to bathe, a medicinal bath is ready for you. If you’d like pajamas, you can use these.” Maomao handed him a set of soft cotton sleepwear. Jinshi looked surprised at first, but his smile grew progressively more gentle. It wasn’t the smile of a celestial nymph, but it could still have melted the heart of any woman—or man.

“I believe I shall bathe,” Jinshi said, heading for the adjoining bath. The tub, filled with hot water painstakingly brought by the menservants, would be the perfect temperature. How they must have struggled, first to boil it and then to bring it here before it cooled!

Maomao felt a wave of relief, and it seemed like the furrow in Gaoshun’s brow—he was in a corner of the room—softened as well. And yet he also seemed uneasy.

“I shan’t be sleeping alone,” Jinshi reiterated.

“No you shan’t, sir.”

On that count, at least, there would be no question. Jinshi opened the door to the bath with an inscrutable expression—and then immediately slammed it shut again and scuttled back to Maomao in a tizzy. His scurrying looked somehow comical. He was wearing his mask again.

“Why are there scantily clad women in the bath?” he demanded.

“No need to worry, sir. They’re professionals.”

The guy could hardly peel his own tangerine, so Maomao figured bathing himself was out of the question. She’d asked for clothing to be ready for him, just like when the Emperor bathed, and figured that while they were at it he should get a massage too.

“Don’t you like massages, sir?”

“Does it stop at a massage?” he ventured.

“Often not.”

This was a service industry, after all. And if the customer requested it, many practitioners would add extra services that—well, they didn’t bear speaking of. Everyone knew that was how the pleasure quarter worked.

“Still going to have that bath, sir?”

“Thank you, I’ll pass.”

“Change of clothes?”

“I can do it myself.” Jinshi took off his overgarment and pointedly pulled on the sleepwear on his own.

He’s surprisingly well-built, Maomao observed, although she had no particular emotional reaction to that fact. She picked up the overgarment off the floor, folded it neatly, and put it away in a chest. It still carried a wisp of perfume, an aroma that conveyed its owner’s excellent taste.

Maomao took a cup and a small teapot from the bedside and poured something for Jinshi. He tilted his mask up and took a drink. “Sleeping medicine or something?” Maybe it had tasted funny. Perhaps Maomao should have taken a sip to show that it was safe.

“It contains nutrients to boost your energy, sir.”

Jinshi spat out the tea. Maomao, finding herself veritably drenched in it, couldn’t help giving him a bit of a scowl.

“Why in the world would you give me that?”

“I’ve heard it’s the most effective remedy when a man is tired.”

“Do you, uh, mean what I think you mean by that?”

“What else could I mean, sir?”

The look on Jinshi’s face was a mixture of disgust and shyness. In fact, he seemed to be making that sort of face a lot today.

Maybe there’s some problem with me being so direct. Jinshi might be a man, but perhaps he was still embarrassed to hear biological facts stated so plainly. He was still young, after all, and maybe he wasn’t as mature as he often looked. She felt bad for acting like he was an animal who would be in rut all year round. Even so, his reaction seemed a little strange. Probably nothing worth worrying about.

Jinshi couldn’t seem to look Maomao in the eye, but she continued, “So, what kind of woman would you prefer?”

“Huh?” he said stupidly.

Maomao clapped twice, causing a group of five stunning ladies to file in from another room. Each of them looked sweet and innocent.

“Lady Suiren told me you prefer them your own age,” Maomao explained. Suiren was Jinshi’s caretaker. She could be mischievous in her way, but she was a first-rate attendant.

Given Jinshi’s apparent fixation on chastity, they’d endeavored to find virgins—a state all the more desirable because they were certain not to have any diseases. It had proved impossible to get enough from the Verdigris House itself, so they’d pulled some strings at some other nearby brothels. That had earned a frown from the madam, but if they wanted all these virgins on such short notice, that’s what it took.

The women had been told only that the man involved was a noble, which was enough to get them on board. They were all the more intrigued by what they glimpsed of Jinshi’s beauty under his mask.

Yes, Jinshi must have had the eye of many a young woman, yet at the moment he was simply standing with his jaw open. He looked at Maomao, his total befuddlement obvious even behind his mask. In the corner of the room, Gaoshun had gone beyond holding his head and advanced to pressing his forehead against the wall.

“Are none of them to your liking?” Maomao asked. It wasn’t Jinshi, but the assembled women, who reacted to this. Each started to gesture at Jinshi in whatever way she thought would be most attractive. “None of them have yet known a man,” Maomao said. “The madam herself inspected them.”

Exactly what kind of inspection it was can be easily guessed.

Jinshi, moving as awkwardly as a puppet, looked at Maomao. “I just want to go to sleep. Please let me rest!”

“I see, sir. Then just pick a woman, any of them—”

“I mean literally!” he exclaimed.

Maomao’s shoulders slumped, and the courtesans left the room in a collective huff.

Instead Maomao went over to Gaoshun, whose shoulders were even slumped-er than hers, and said, “Would you like them, then, sir?”

“I, er, have a wife. A scary wife. And my daughter’s something of a stickler for cleanliness...” he said.

Ah, of course. Maybe it wasn’t the best idea to offer courtesans to a married man.

“Do you know what it’s like to be told ‘Papa, you’re filthy! You have to bathe last tonight!’?”

“Yes, sir, I do.”

I know how his daughter must feel, anyway...

She did feel bad for Jinshi’s attendant having to stand around, though, so she offered him a nice sofa to sit on. There was another bed, and indeed another entire room available, but Gaoshun politely turned her down when she pointed this out. If anything, he worried that a divorce might be in the offing if he were ever to be discovered in a place like this.

Maomao went back to where Jinshi was reclining and pulled the covers over him. When she went to leave the room herself, she felt him holding on to her arm.

“Surely you could at least spare a lullaby.”

She didn’t say anything at first—she wanted to tell him no, but he was looking at her with those puppy-dog eyes he got sometimes. And anyway, after all the excitement with the bath and the courtesans and everything, it seemed this little break hadn’t helped him feel refreshed at all. He refused to let go of her, and she let out a sigh. “I’m not a good singer.”

“I don’t care.”

So, gently tapping the covers to keep time, Maomao began to sing. An old children’s song that the courtesans used to sing to her. It wasn’t long at all before she heard Jinshi’s breathing take on the even rhythm of sleep.

Jinshi left in the evening, just before the sun sank beneath the horizon. The nap must have been restorative, because he woke up looking much better and ate three entire bowls of congee. Maomao had started to fear he might work himself to death, but if he was still eating, he wouldn’t die. If anything, she thought he might catch trouble from Suiren when he was too full for dinner that night. Or maybe she was worrying too much?

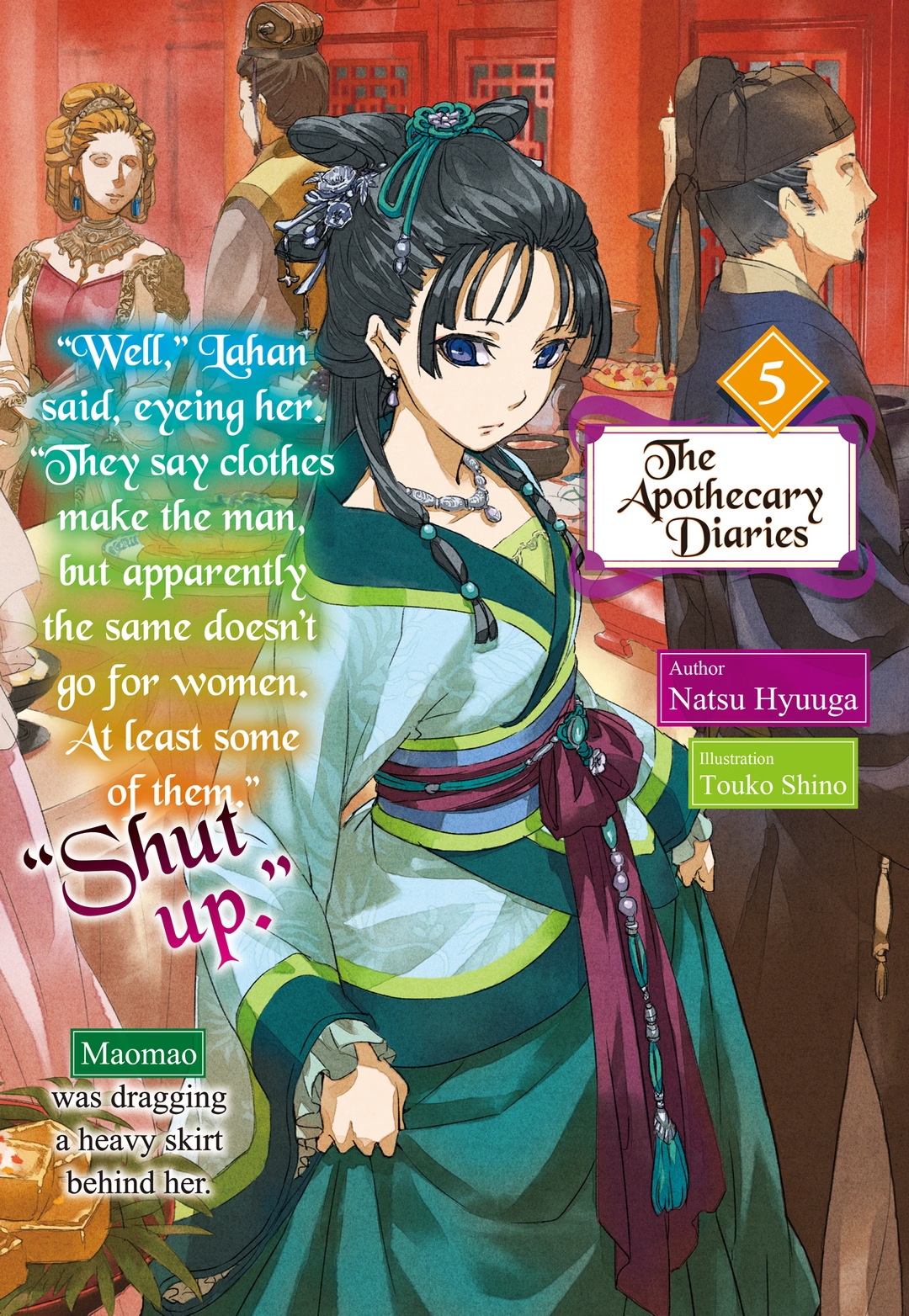

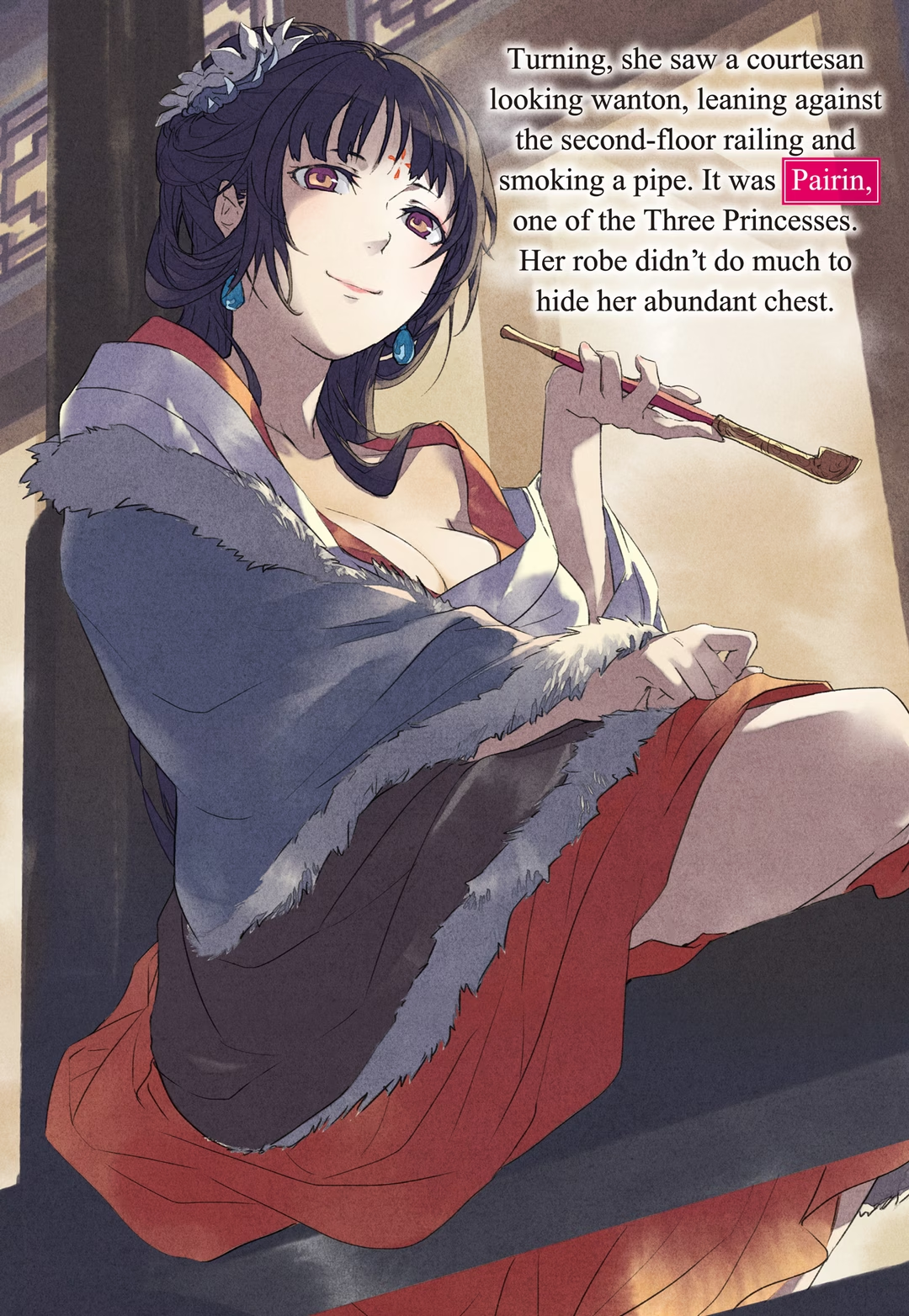

With his mask back in place, Jinshi boarded his carriage and Maomao watched it leave. As she stood there, she thought she felt a pair of eyes on her. Turning, she saw a courtesan looking wanton, leaning against the second-floor railing and smoking a pipe. It was Pairin, one of the Three Princesses. Her robe didn’t do much to hide her abundant chest.

“Isn’t it about time you gave in?” she asked.

“Gave in to what?” Maomao asked, turning away from her elder sister and heading back to the shop.

Chapter 4: The Fire-Rat Cloak

Maomao’s apothecary shop closed its doors as the lanterns were being lit at the Verdigris House. There was no point doing business after dark—it would only attract unsavory customers, and the lamp oil would be a waste of money, anyway. Maomao totaled up the day’s earnings and handed them over to the madam. Keeping large sums of cash in her little shack would attract thieves and burglars. Having the money kept somewhere safe was far better, even if she did have to pay for the privilege. Then she gathered up the coals and the herbs and locked up the cramped little shop.

“All right, we’re going home,” she announced.

“What, already?” Chou-u groused, but she took him by the scruff of the neck and headed back to their shack. Though it was located just behind the Verdigris House, the walls were riddled with cracks that let in the wind, making it very cold.

Maomao placed the coals among the starter paper in the stove, and when there was a decent fire going, she tossed some kindling on it. Chou-u, feeling the cold, was curled up on his sleeping mat, wrapped in his blanket. Maomao heated some soup in a pot on the stove, stirring gently. It involved a base of dried meat, along with vegetables and kudzu she’d picked in the garden. She even shaved some ginger into it to take the edge off the chill.

“Not going to have any?” she asked.

“Sure am,” Chou-u said, trying to shuffle over while still under his blanket like a giant pill bug. Maomao smacked him with a knuckle, but tossed a cotton jacket at him in exchange for taking away his blanket.

I wouldn’t mind another winter outfit, Maomao thought. She was being pretty fairly compensated for “bringing up” Chou-u, but she didn’t intend to waste the money. Chou-u might grumble, but so long as Maomao was the one getting the cash, the education he would receive was: those who don’t work don’t eat.

She poured some soup into a chipped bowl and handed it to Chou-u, who sat on a chair with his knees up and sipped at it. “Needs more meat,” he said.

“If you want meat, go earn the money for it!” Maomao said. Then she took a sip of the soup herself. They didn’t have any congee, but she’d been able to get some bread. She took a bit from their supply and set it beside the soup pot to warm it up. Then she broke it in half and stuffed some simmered vegetables inside. She didn’t think the bread tasted particularly good—maybe on account of last year’s bad harvest. A poor crop led to poor-quality grain, perhaps.

“You’ve got money, right, Freckles? Why don’t we get some decent food, then?” Chou-u said, reaching for another piece of bread despite his complaining.

“I’m renting the shop from the old lady, moron. Do you have any idea what she charges?”

“Why not find another place, then?”

“Listen, you. It’s not as simple as that.” Maomao dipped her bread in what remained of her soup and put it in her mouth. She might have been able to lead a slightly richer life, had she so wished. But she had reasons for not doing so. “You’re coming with me tomorrow. We’re going clothes shopping. You’re cold like that, aren’t you?”

“Yay!” Chou-u said, tossing up his hands, but the motion threw him clear off his chair. His paralysis left him unable to catch himself, so he tumbled pathetically to the ground.

Maomao looked at him for a moment, her expression cool as she washed her bowl in the water bucket.

The next day, she and Chou-u went to the market, which lined the great thoroughfare that bisected the capital from north to south. The farther north you went, the richer the shops became, while the class and quality declined as you went south. The pleasure district was in the south of the capital, so the first market stalls they found didn’t even have awnings; they were just wares laid out on rush mats.

The farther you went into the side streets, the shadier the shops became. The proximity of the pleasure quarter seemed to breed places selling dubious medicaments. Naturally, an apothecary like Maomao wasn’t taken in by such products, and the merchants knew it; none of them called to her as she passed their stores. They were looking for men who weren’t yet used to the pleasure district; those made the best marks.

Maomao worked her way toward the center of the capital, grabbing Chou-u by the scruff of the neck each time he threatened to wander away. It was sometimes said that buying cheap could actually cost you money. A cotton jacket from one of the street stalls would certainly be inexpensive, but the material would be poor. It would never stand up to the brat running around in it and doing all the things children do. Any merchant with an actual building would know they needed the trust of the local shoppers; a jacket from somewhere with an actual storefront would cost a little more, but would inspire much more confidence in the product.

Maomao picked a place from the tangle of shops and went in—a place that sold clothing to commoners, including used clothing. When she brushed past the curtain and into the shop, she saw clothes hanging from the ceiling. Within, the shopkeeper was mending a garment and yawning. A brazier beside him was filled with crackling coals, but it was surrounded by a shield to prevent the sparks from landing on any of the wares.

“Aww, used clothes?”

“Don’t be picky.”

Chou-u was still small; he would hit a growth spurt soon. It would be more economical to buy something they wouldn’t have to hesitate to replace. Maomao was looking through the merchandise for a child’s padded jacket when something caught her eye.

“Whazzat?” Chou-u, ever eagle-eyed, came over.

It was a robe hanging on the wall—a long-skirted outfit of pure white. The lack of color made it look somewhat plain, but it also had a whiff of the exotic; it was most unusual. Maomao’s eye was drawn to embroidery in what looked like a pattern of vines on the sleeves.

Could this be...

“Geez, that looks pretty cheap,” said the little shit. Heaven forfend he ever hesitate to say whatever came into his head. Maomao gave him a smack, alert that the shopkeeper might be listening, but from the proprietor all she heard was laughter.

“Hah, you think that’s cheap, boyo?”

“Isn’t it? Girls’ clothes are supposed to be colorful!”

“I s’pose you’re right.” The shopkeeper put a pin in a pincushion, then rubbed his stiff shoulders and smiled at them. He let his gaze drift to the robe. “But this robe, you see...a celestial nymph wore it once.”

“A celestial nymph?” That seemed to get Chou-u’s interest. He had taken a seat on top of a chest of drawers; maybe the paralysis made it hard for him to stay standing for too long.

Annoyed, Maomao continued her search through the shop. The shopkeeper here was one of those clerks who killed time by chatting with the customers. No way of telling how much of what he said was true. All she remembered was how he used to get a hold of her father Luomen for hours at a time.

I just need to find something, and then we can get out of here.

If Chou-u was busy talking to the clerk, that was perfect. She could find something while he was distracted. But it was a small place. Like it or not, she was going to hear the clerk’s story while she browsed.

○●○

Y’see, that robe came to me from the west. A villager in one of the little villages there helped a girl who was lost on the road. The girl was quite beautiful, and the villager fell head over heels in love with her.

She was a most unusual young lady: she had white skin and golden hair. She knew how to spin a thread that was unlike any other, and with it she wove several robes to repay the villager who’d helped her. The robes were embroidered with mysterious designs, and sold for several times what any other cloth was worth.

The girl insisted she wanted to go back to her hometown, but she didn’t seem to know where she lived. Must have come from some far land, I suppose. The villager proposed to the girl, and then again, and again, and finally she decided to accept him.

But it was poor timing, for just then, the girl’s family arrived in the village, looking for her. You could tell it was her family because they had the same sort of hair and skin. The villager had finally gotten the girl to agree to his proposal, though, and he wasn’t about to give her up. So he hid her away, and the entire village pretended they knew nothing about the matter.

The girl’s family went away, but they were suspicious. The villager decided he’d better hurry up and hold the wedding and make the young lady his bride. Once they were joined in marriage, her family would no longer be her family, you see.

The young lady objected, but the villagers paid her no heed. She was made to bathe at the village spring to purify herself, after which they planned to hold the wedding immediately. The girl wept as she washed herself. Her one comfort was that, for her bridal gown, she wore one of the robes she’d made. A reminder of her lost home.

Can you imagine what grief she must’ve felt? Even as she stood in her bridal gown, she almost drowned herself in tears.

As everyone around her celebrated, the girl came up to the altar to swear her vows to the villager. Yet even at that moment, she couldn’t forget her family. She begged the man to return her to her relatives.

He refused. Whereupon the girl doused herself in some nearby oil, grabbed a torch, and lit herself on fire. She ran in flames past the panicked villagers, until she dove into the spring and vanished.

She left behind her only a single piece of cloth, the veil she had been wearing. Of the burning woman herself there was no sign; the villagers speculated that perhaps she’d returned to Heaven. Nor was anyone from her family ever seen again, so the villagers all agreed: the girl and her family had disappeared back up to the sky.

○●○

“And that is the robe the nymph was wearing,” the shopkeeper proclaimed.

“Wow!” Chou-u said, duly impressed. Just a few minutes before, he’d derided the garment as cheap, but now he looked at it as though at a shimmering jewel.

Maomao, meanwhile, was holding up a succession of jackets to Chou-u’s back, wondering which of them might fit him best. She found one with a somewhat unpleasant color, but which was the perfect size.

“Hey, Freckles, this is some gown! How about we buy this?” Chou-u’s eyes were sparkling.

“The boy’s got a point,” the shopkeeper ventured. “That celestial nymph wasn’t much older than you, young lady. I’ll even give you a special price on it, since the two of you are so alike.”

Nice try, but the abacus he was holding suggested the price was still about one digit too many. Maomao nearly laughed out loud.

A celestial nymph, right! I can see a real one for free. After all, one slightly damaged nymph came to the Verdigris House on a regular basis.

“Are you telling me you don’t believe the legend of the nymph?” the shopkeeper asked. “Some people have no sense of romance...” He spread his arms and shook his head with an expression of disappointment.

I’m the one who should be disappointed, Maomao thought. Not only had she seen a celestial nymph before—she’d seen one vanish into the water just like in the story. The “moon spirit” had come back out of the water, too, looking like a drenched mouse and asking if she ever planned a repeat performance. But then again, such sights must be rare indeed. Without meaning to, Maomao chuckled at the memory.

The world was full of strange things—but they always had some explanation. It was only because people didn’t know why certain things happened that they made up stories about curses and magical powers and even sometimes ghosts.

Maomao took a good, hard look at the robe the “celestial nymph” had woven. “May I touch it?”

“Sure. Just don’t get it dirty.”

Maomao felt the texture of the fabric and studied the embroidery. Then she grinned. “Shopkeep, you really think you can sell this thing at that price?”

“Wh-What makes you say that? Of course I can.” And yet he’d been trying to foist it off on Maomao. If he’d really believed the robe had been woven by a genuine visitor from Heaven, he’d have added still another digit to the price.

“Uh-huh. And what if you could sell it for ten times what you’re asking?”

“Ten times? Hah, well, I’d certainly be a happy shopkeeper. I’d give you everything you’re holding for free.”

The clerk sounded like he was joking, but Maomao said, “Would you, now? You heard the man, Chou-u.”

“Uh, yeah, I did, but you can’t get ten times the price for that thing, can you? You’re out of your mind, Freckles.”

Even Chou-u was making fun of her now. Maomao scowled and grabbed a coal from the brazier with a pair of metal chopsticks. “I’m going to borrow the robe and this coal for a few minutes, mister.”

“Hey! What are you doing?”