Character Profiles

Maomao

An apothecary in the pleasure district. Downright obsessed with medicines and poisons, but largely uninterested in other matters. Reveres her father Luomen. Nineteen years old.

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. Inhumanly beautiful. He can’t get Maomao off his mind, but by hook or by crook, she always manages to evade him. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant. Doesn’t feel pain as acutely as most people, which gives him far greater physical limits than most have. He’s very serious, but that makes him easy to tweak. In love with Consort Lishu.

Gaoshun

Basen’s father. A well-built soldier, he was formerly Jinshi’s attendant, but now he serves the Emperor personally.

Lakan

Maomao’s father and Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle. He’s a high-ranking member of the military, but his bizarre behavior causes people to avoid him. He loves Go and Shogi and is quite good at both.

Lahan

Lakan’s nephew and adopted son. A small man with round glasses, he has a soft spot for beautiful women and will try to chat them up anytime he sees one. He runs side hustles to try to pay off his adoptive father’s debts.

Luomen

Maomao’s adoptive father; Lakan’s uncle. Once a eunuch in the rear palace, he now serves as a court physician. He’s missing one kneecap, a punishment inflicted on him many years ago.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. Twenty-one years old.

The Emperor

A real go-getter and possessor of prodigious facial hair. Prefers his women well-endowed. Thirty-six years old.

Yao

Maomao’s coworker. She’s fifteen, but her height and well-developed figure make her look older.

En’en

Maomao’s coworker. As Yao’s serving woman, she helps in the medical office along with her mistress. She’s devoted to her mistress with a love that borders on the twisted. Nineteen years old.

Hongniang

Empress Gyokuyou’s chief lady-in-waiting. She works hard, which occasionally leaves her at the mercy of her playful Empress.

Yinghua, Guiyuan & Ailan

Empress Gyokuyou’s longest-serving ladies-in-waiting.

Haku-u, Koku-u, Seki-u

Ladies-in-waiting to Empress Gyokuyou, they’re three sisters each separated by a year.

Prologue

“Make sure you smile.”

Her mother was always saying that to her. To be certain her father would be happy on those rare occasions when he visited. To ensure he would give her that coveted pat on the head.

Her mother was not her father’s main wife. Her father was old enough that he could have passed for her grandfather; he had a son by another woman who was as old as her mother. More like an uncle than an older brother.

Perhaps her older brother didn’t like having a sister so much younger than he was, for his own children were forever teasing her, pulling her hair and pelting her with mud pies—ordinary childish cruelty. They would repeat what the adults said about her. Always careful to travel in packs large enough that she couldn’t fight back.

They jeered at her, called her a concubine’s daughter. So she grinned back. The corners of her mouth turned up, just showing her teeth. Her brother’s children, who had known only obsequious smiles, backed away. She’d only smiled. What did they see when they looked at her? Their reaction seemed so ridiculous that it made her smile bigger.

Just at that moment, her father appeared. How must she have looked to him, covered in mud?

He began smiling too. He ignored his grandchildren, dressed in their finery, and came over to his filthy daughter. He wiped the dirt from her face and patted her head.

“I’m going to make you first,” he said.

She asked him what he was going to make her first in.

“First in the whole nation. I know you have what it takes.”

The other children didn’t have it. Only she did. Learning that she was special like this made her heart pound.

“Don’t let the sparkle fade from your eyes. The one thing you must never do is lose hope. Smile. And never let it slip.”

Smile? She could do that. So long as there was something the least bit amusing, it was easy. She didn’t need her father to tell her that. She spent all her time seeking out fun and pleasant things. Even after he sent her away. Away, to that den of iniquity full of women...

Chapter 1: The Go Book

The wind was getting colder every day. Maomao began to sleep under an extra blanket.

She wasn’t sleeping at that moment, though. She was staring open-mouthed at a veritable mountain of books piled in the entryway of the dormitory and marked To Maomao.

“What are those? I mean, they’re books, obviously,” Yao said as she emerged from her room. She’d managed to recover from her episode of poisoning, thankfully. It had taken a while for her to get back into action, but she would be starting work again in a couple days.

She came and stood beside Maomao. Her lovely face was now marked with jaundice. Her liver and kidneys had been badly compromised by the poison; she would have to avoid alcohol and salt, probably for the rest of her life. And they’d have to find her food that would be good for her skin.

“They’re all the same book,” En’en observed. She could naturally be found whenever Yao appeared. She was holding a bag of ingredients for their dinner—she’d been furiously gathering medicines and foods that would alleviate Yao’s jaundice. It saved Maomao the trouble. “It looks like it’s about Go. It says it’s by Kan Lakan.”

This was the doing of the freak strategist. Associating with troublesome people could only bring you trouble, Maomao knew, but knowing it and staying out of trouble were different things.

“I told him we didn’t want these sitting around here, but he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He gave me a letter for you too,” said the middle-aged woman who ran the dormitory.

She gave Maomao the letter. It contained a great many fulsome and indirect expressions, all written in a lovely script, but translated into plain language it said, I made a bunch of copies of this book about Go. You can have some too. It was clear that he’d forced some subordinate to write it for him. The poor guy.

“What are we supposed to do with these?” Yao asked. The stack of books was tall enough for her to lean against. Books were valuable objects—just one could cost enough to pay for a month of meals. Yet here was a whole stack of them. They were printed books, so somewhat cheaper than hand-copied manuscripts, but producing so many of them was still no mean feat. Maomao could picture the strategist’s adopted son Lahan hyperventilating over the amount of money involved. Oh, well. Not her problem.

“We burn them,” Maomao said flatly. But then she changed her mind. “No... That wouldn’t be nice.” It wasn’t the books’ fault that they had been written by this particular author.

She flipped through one of the books and found that it was surprisingly well done. It contained game records, diagrams of games of Go, accompanied by explanations of the salient features of the board situation. It would probably go over the heads of beginners, but it seemed like something experienced players might enjoy. There was even an illustration of calico cats playing Go together, but Maomao chose to ignore it.

En’en was peeking at the book with evident interest.

“Want a look?” Maomao said.

“Sure!”

Maomao passed her a copy and she started flipping through it, eyes sparkling. Who knew she had interests besides Yao? thought Maomao (who did pick unusual things to be impressed by).

“Does it look interesting?” she asked.

“Yes, it does! You can tell this is the work of our honored strategist—it’s very well done. The first half consists mainly of games that rely on a lot of joseki, while the second half shows off less-conventional play.”

Maomao’s “older sisters” had taught her the basics of Go and Shogi, but she still didn’t quite follow what En’en was saying. Instead she asked, “Want one?”

“If you’re offering, then sure. If you’re trying to sell it to me, I’d be willing to pay up to one silver piece. Not only is the material excellent, but the paper and print quality are both beautiful.”

“One silver piece?” Maomao looked at the mountain of books. She’d had no idea they were that valuable.

“Just one? You think she should let them go that cheap?” Yao said, looking over the construction of the books. Being from a rich background, her sense of what was “cheap” was a bit out of step with most people’s. One silver piece could easily pay for two weeks’ worth of meals.

“I grant she could probably get more,” En’en replied. “I was hoping for a friendly discount.”

Not collegial—friendly. So we’re friends now? If En’en considered Maomao a friend, then it would be rude not to treat her as a friend back. Therefore, En’en was a friend. Maomao felt she could trust En’en’s valuation of the book (if not the somewhat financially unmoored Yao’s). If she said the books were worth one silver, they probably were. It looked likely they were going to go into mass production, however, so maybe she should price them a little lower than that.

“You and Maomao are friends, En’en?” Yao stared at them fixedly. “What does that make me, then?”

“You are my precious and irreplaceable young mistress!” En’en said, thumping her chest and smiling broadly.

I don’t think that’s what she wanted to hear, Maomao thought. The “young mistress’s” expression immediately turned sour. She seated herself on a chair in the entryway and crossed her legs, sulking.

“Er?” En’en said, taken aback.

“You can just have the book, En’en. But if you know anyone who might like Go, would you spread the word?”

“You’re looking for Go players? Yes, I know a few. The physicians like to spend their days off playing Go.”

Ah, now that was useful info. Maomao felt a smile creep over her face as she regarded the books. With a little money in my pocket, I could buy some valuable medicines. A wide variety of items from the west had accompanied Shaoh’s shrine maiden to the capital. The most exotic of them would be snapped up by the city’s richest residents, but soon what remained would work its way to the markets. Even there, such imported goods would not come cheap—but, yes, that’s what money was for.

“Do you think you could tell me who those Go players are?” Maomao asked. En’en responded by pulling out a silver coin from her purse.

“Here,” she said. “Payment.”

“I said I would give it to you.”

“I’m happy to pay for it. But in exchange...” En’en glanced significantly at the pile of books. “Cut me in on the deal.” She gestured at the coin.

I knew she was a smart one. Maomao gave her a look indicating she understood. That was when they heard the thumping behind them. Yao was stamping her feet. Foot tapping was not the sort of thing that refined young ladies were supposed to do, but Yao was making a special effort.

“Y-Young mistress, don’t do that!” En’en said immediately, exactly the rise Yao had been looking for.

“En’en! Isn’t dinner ready yet?” She fixed the two of them with a scowl.

“Oh! I’m sorry. I’ll make something right away!” En’en said and hurried to the kitchen. Maomao looked at Yao, contemplating how adorable she was. She let her hand brush the books. She decided to put them in her room for now. It was going to be tight quarters for a while.

“Maomao,” Yao said.

“Yes?” Maomao looked back, a few books already in her hands.

“Are you free tomorrow?”

“I suppose, in a manner of speaking. But then, in a way, I also have work tomorrow.”

All three of them, Maomao, Yao, and En’en, had the next day off. Maomao could do what she wanted—poke her head in at the apothecary’s shop in the pleasure district or wander around town to see if anyone was stocking any interesting medicines.

“It’s got to be one or the other!” Yao said.

“Busy, then,” Maomao said.

“You’re free! I know you are!” Yao took Maomao by the shoulders and shook her. The young mistress could be so headstrong.

Maomao nodded. “Is there something you want to do tomorrow?”

In response, Yao’s hand went to her cheek, brushing a blotch of jaundice. “I’d like to go shopping for some medicine. I thought you’d know more about it than En’en.”

I get it. Yao was fifteen, an age when young women were worried about their appearance.

“Perhaps you’d like to shop for some makeup while we’re at it?” Maomao knew a place that served all the highest courtesans. When some good-for-nothing customer struck them, that was where they went. The shop knew how to hide even the nastiest bruises. Maomao was sure Yao would like to look her best when she came back to work.

“Makeup?” Yao looked closely at Maomao. She was studying the area around her nose. “Why do you draw freckles on your face, anyway?” They lived in the dorm together; Yao had long ago realized that Maomao’s freckles were fake.

“Oh, you know,” Maomao said. She’d resolved to stop once, but Jinshi had ordered her to keep doing it. Having to explain why, though, was tricky. It was risky to bring Jinshi into it. Finally she said, “Religious reasons.” It seemed like the best way to not have to go into details.

Yao, though, wouldn’t give up. “Does it, like, represent some apothecary god or something?”

“No. It’s a charm, if you will. To help me grow taller.”

“Huh. All right.” Yao didn’t need to get any taller, so such a charm was singularly unhelpful to her. Maomao was relieved to see her losing interest.

“Maomao...” It was at that moment that En’en entered carrying the evening’s side dish. She was giving Maomao a look that clearly said: Please don’t lie to the young mistress.

Chapter 2: A Jaunt Around Town

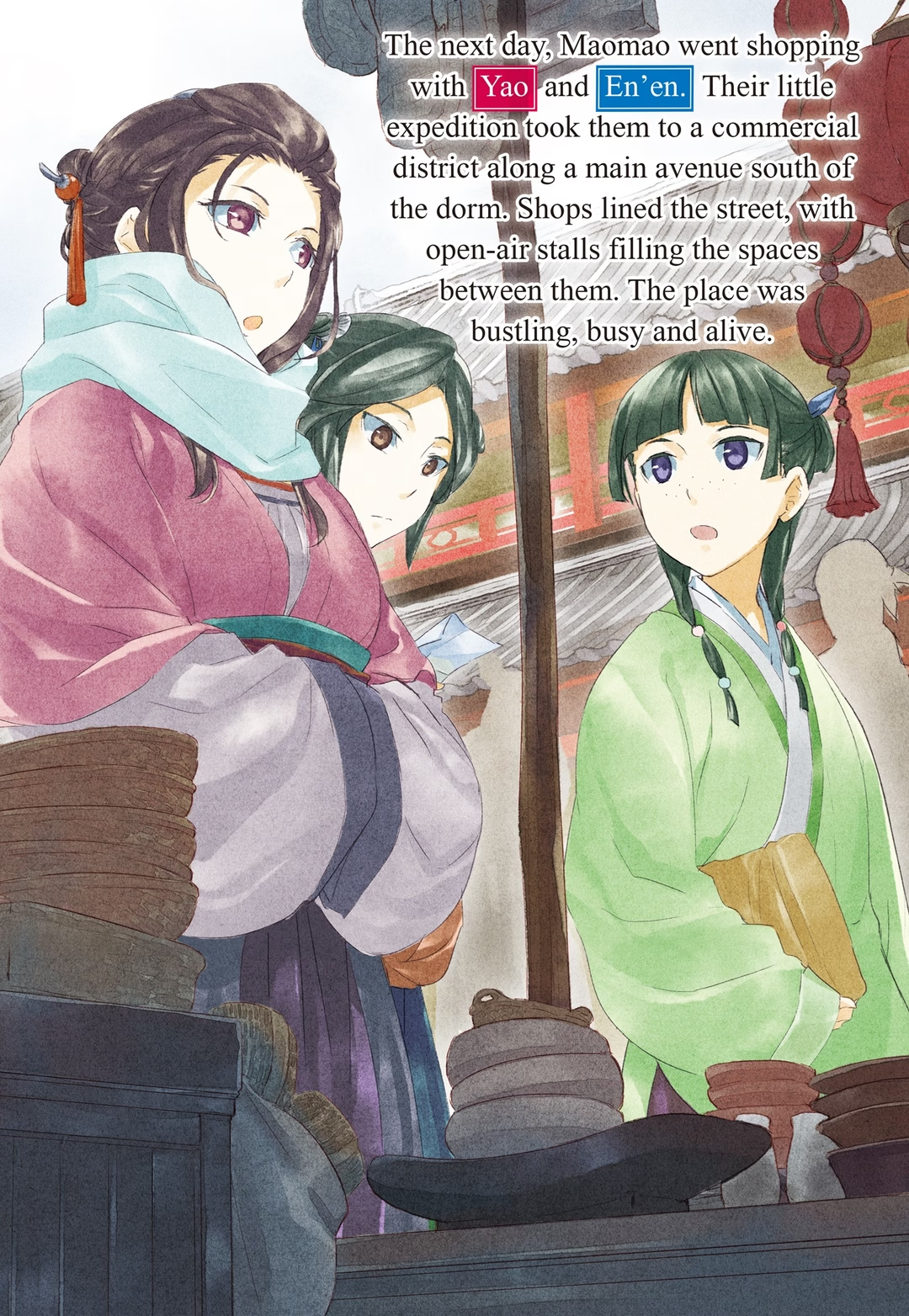

The next day, Maomao went shopping with Yao and En’en. Their little expedition took them to a commercial district along a main avenue south of the dorm. Shops lined the street, with open-air stalls filling the spaces between them. The place was bustling, busy and alive.

“What’s that you’ve got, Maomao?” Yao asked, pointing to a cloth-wrapped package Maomao was carrying.

“Some of the books from yesterday,” she replied. “I thought maybe I could sell a few copies to the bookstore.” She’d brought just three, knowing that they wouldn’t be interested in a large pile of copies of the same title.

“You’re selling them?” En’en scrunched up her face.

“Just trying to get a sense of the market value.”

“I see,” she said, apparently satisfied.

Yao was peering at the sky. “I’m not sure I like the look of this weather,” she said.

Maomao looked up: the sky was heavy with leaden clouds. “You’re right. Strange for autumn. It can’t be a typhoon at this time of year.”

“It’s a little chilly without the sun,” said Yao, who had a scarf wrapped around her neck. It helped ward off the cold, yes, but Maomao suspected it was also to hide her jaundice. I knew it must be bothering her. She renewed her resolve to find Yao some good makeup.

“I’d like to start by picking these up,” En’en said. She showed Maomao a list she’d written. It mostly consisted of fruits and vegetables. “Anything I’m missing?” she asked.

In response, Maomao looked at Yao. “You like white rice, do you, Yao?”

“Like it? I mean, I guess. Isn’t it just basic food?”

“Let me put it this way: Do you prefer to actively avoid other kinds of rice?”

White rice was rice that had been polished. It tasted far better than unpolished rice, but the polishing process removed many of the nutrients that made rice worth eating. Maomao’s old man had told her that eating unpolished rather than polished rice would help you avoid beriberi.

“Are you saying I have to eat unpolished rice?” Yao asked. The frown on her face suggested how she really felt about it.

“Not necessarily, but you should consider mixing things into your white rice. Grains, barley, or maybe sesame seeds. Any of them would give you a broader variety of nutrients.” If rice was going to be her staple food, it would be best if she could get a range of other nutrition with it.

“How about we toss in some buckwheat berries, then, mistress? I know you like those,” En’en said, but Maomao made a big X with her hands. En’en looked worried. “No buckwheat?”

“I’m afraid not. Because I can’t eat it.” Buckwheat gave her hives.

The other two women stared at Maomao, unimpressed.

What am I supposed to say? En’en’s meals are delicious. And she’d frequently made enough for three recently.

“P-Perhaps I might suggest seaweed?” Maomao said.

“Seaweed,” En’en repeated. She didn’t seem very enthusiastic.

“Certainly. And meat can be replaced with beans or fish. Not all of it, of course, just some.”

Fatty foods were supposed to be bad for you. Yao was looking more despondent by the minute. People her age liked to eat lots; she would naturally be disappointed to hear she shouldn’t have too much meat. She would also have to limit her intake of salt and alcohol. En’en was looking concerned too.

Hmm, Maomao thought. The saying went that you are what you eat: food was kissing cousins with medicine. But it still had to taste good. I think I know what to do.

Maomao had a favorite place for moments like this. “Come this way,” she said.

“Why? What’s over there?” Yao said.

Maomao led them off the main road, farther and farther down the back alleys, glancing back occasionally to make sure they were still following her. Soon there were as many houses as there were shops, and eventually they arrived at a restaurant with a soot-stained sign. It didn’t exactly look like it specialized in haute cuisine. There were two tables crammed into the restaurant itself, with another poking outside. Instead of chairs, the tables were lined with upside-down barrels.

“Are you both feeling hungry?” Maomao asked.

“It’s a little early for lunch,” Yao said, but she looked intrigued. She couldn’t help noticing, though, that the restaurant seemed deserted.

“A little early is best. It gets crowded at lunchtime,” Maomao said. She peered into the shop, warm steam drifting out. “Auntie? Are you open?”

“Sure enough,” came a voice from within. A woman who must have been something more than forty years of age shuffled up. “Hoh. The apothecary girl. Don’t usually see you at this hour.”

“We hoped to get a meal in before it got crowded.”

The woman was one of Maomao’s customers; she came all the way to the pleasure district to buy medicine. She’d been a regular ever since Maomao’s father had cured her of an illness she’d suffered from many years ago.

“Three portions, please. Whatever you have on hand. Ideally, something that’s not fried.”

“Coming right up. Don’t usually see you without your father either...” She looked at Yao and En’en and grinned.

“Less talk, more food. Please.” Maomao seated herself on one of the barrels.

“Maomao, why did you suddenly decide to take us out to eat?” En’en asked. She and Yao both looked mystified.

“Trust me. Sit down,” she urged them.

They sat. The woman soon brought their food, a pot full of congee and several side dishes. Maomao apportioned the side dishes among the three of them, passing a bowl each to Yao and En’en.

“All right, if you don’t mind...” Yao, ever the proper young lady, made a gesture of thanks and picked up her spoon. She didn’t look entirely sure about this; the restaurant wasn’t the cleanest place around.

“Is this potato congee?” En’en asked, sipping a spoonful of porridge. Sesame seeds floated in the congee, which included stewed potato. At the first mouthful, her eyes opened. “Is this potato congee?” The sweetness of it must have startled her.

“Yes—it’s sweet potato,” Maomao said. The very tubers that Lahan’s biological father was growing. They came from the south and were ordinarily a rare treat—but this woman’s restaurant was able to procure a supply through the Verdigris House.

“That’s absolutely amazing,” Yao said, going for another spoonful. Maomao grinned: she already knew that.

“You see? And sweet potato with sesame fits perfectly within your diet. You could probably get away with putting some barley or oats in there too.” The modicum of salt in the dish was perfect for flavor, although if it needed a little something extra, minced kelp might make a good addition.

“Try some of this too,” Maomao said, passing her some sticky stewed tofu.

“It really is wonderful,” En’en said, almost regretfully. As a confident cook, perhaps it touched a nerve to eat something quite so delicious. “The flavor is so robust, but it never becomes overbearing.”

“That’s what ginger and garlic will do for you,” the middle-aged woman said. “And instead of seasoning, we use xiandan.” That is to say, a salt-cured egg added when seasonings ordinarily would be. “We get the viscosity with kudzu root. It warms the body—good for the type who catch a chill easily.” (Kudzu root was also used as a medicine.)

“How did you make this?” En’en asked, her eyes shining as she pointed to some grilled fish.

“Fragrant herbs and just a dab of butter for taste. I know you said nothing too fatty, but surely a dab won’t hurt.” She rubbed her sides as she spoke.

“Our hostess can’t eat rich foods because of an old illness,” Maomao explained to the other girls. “But she proves that you can still make wonderful meals without much fat or salt.”

“Gracious, Maomao, you’ll make me blush.” The woman was grinning again. “Here, cow’s milk. You can drink some of this if the smell of the condiments bothers you.”

“C-Cow’s milk?” Yao said. It was a regional thing; not everyone was used to it.

“I’ve warmed it up and added a bit of honey. It should go down easy. I’d like to put my best foot forward for friends of Maomao’s.” She was careful to emphasize the word.

“Gah. Yeah, fine. Don’t you have any other side dishes?” Maomao practically shoved the woman back into the restaurant, her tone clearly communicating that she wished the lady would butt out. People evidently regarded Maomao as someone who had no friends. When Maomao had told her “older sisters” at the Verdigris House about the girls her age she used to hang out with at the rear palace, they’d all looked shocked. Pairin had gone so far as to wipe the corners of her eyes with a handkerchief.

I can’t believe them. Really. Of course she had friends. Emphasis on had, maybe. She could think of at least two—but one of them she couldn’t see anymore, and the other...well, Maomao hoped she was doing all right for herself. Where did Xiaolan end up working? she wondered, recalling the talkative palace woman. Maomao knew she’d found work at a mansion somewhere in the capital, but that was all she knew. She’d received a few letters, written in Xiaolan’s unsteady hand, but none of them included the crucial detail of where she was actually living. Maomao couldn’t reply to her even if she wanted to.

She grabbed a bit of one of the side dishes, still mostly staring into space. Yao was digging into the congee with gusto, apparently quite taken with the taste. En’en was busy trying to deduce exactly how it had been seasoned.

“Would you like to go to the makeup place after our meal?” Maomao asked. En’en had suggested shopping for ingredients first, but then they would end up carrying the groceries all over. True, the best stuff might sell out if they didn’t hurry up, but on the other hand, what was left would be marked down. Maomao considered that a fair trade.

“I’m surprised you know so much about makeup, Maomao,” Yao said.

“My line of work has exposed me to a lot of different things,” she replied. At the shop, she sometimes had to mix up concoctions of dye and white powder for customers who were self-conscious about a scar—experience that had come in very handy for disguising Jinshi.

“Is the makeup place close to here?” En’en asked. Now she was jotting down a recipe with a portable writing set.

“We’ll have to walk a bit, but it’s not far. And perhaps we could make a quick detour on the way back?” Maomao held up her bundle of Go books.

“Still have your heart set on selling those?” En’en sounded like she still couldn’t quite believe it.

“Well, I certainly don’t intend to just carry them around forever,” Maomao said. Her mind was made up.

After the meal, the girls worked their way back to the main street. The most famous courtesans in the capital used white powder every bit as good as anything that could be found at a noble girl’s dressing table, and the shop Maomao had in mind occupied a prime location in the commercial district.

“Skewers! Delicious skewers! Who wants one?” A man with a handful of chicken skewers was trying to draw in customers. The meat was cooked over a charcoal fire, dripping juices. The man didn’t really have to bother hawking his wares—the smell was more than enough to keep the customers lining up. If she hadn’t just had lunch, Maomao would have been with them.

“Is it just me, or does the marketplace feel a little different from last time?” Yao said. She looked around, perplexed. Their sheltered young mistress was really getting the hang of doing the shopping!

“As the seasons change, so do the shops. And you might be noticing all the imported stuff,” Maomao said. There were colorful textiles, exotic accessories, and—

“Fine grape wine, all the way from the west! You won’t find it anywhere else! Have a taste, if you please!” A merchant was dispensing a red liquid from a barrel. Maomao started to shuffle over to him, but En’en caught her by the collar.

“Not even one drink?” she said, looking at En’en.

“Not when the young mistress can’t have any. You’ll survive.”

“I really don’t mind,” Yao said. She couldn’t have alcohol now, but since she hadn’t been a drinker to begin with, it wasn’t really an issue.

“Getting drunk is not the way to go shopping,” En’en replied.

Maomao’s shoulders slumped and they wandered back to the main street. Other customers, ones who hadn’t had somebody grab them before they could try a tipple, were buying bottles almost as soon as they tasted the stuff. Maomao normally preferred good, dry alcohol, but something fruity wasn’t so bad every once in a while.

Is it really imported? Maybe it wasn’t from another country, just sort of from that general direction. Then again, the alcohol Maomao had tried in the western capital had been good stuff. She would have been happy to have another taste of it—but she would worry that the flavor might have changed during the long journey east. Wonder if there might be time to buy some on the way home.

They walked past the wine shop, but Maomao kept looking regretfully over her shoulder.

The makeup shop patronized by the Verdigris House was smaller than many of its competitors, but it was more than lovely enough to set the heart of a young woman aflutter. Paintings of beautiful women were posted out front, and rows of makeup products were visible within. Every woman who passed by stole a look at the place, clearly having an internal argument about whether to go inside. The owner never shouted, summoned, or cajoled. Elite establishments like hers didn’t stoop to base hawking. Those who wanted what she had for sale would come to her without any prompting.

“All right, just so I know, what’s your budget?” Maomao asked.

“We’ll pay any price as long as we can get the best stuff!” En’en responded, clenching her fist for emphasis.

Don’t think so. I know you can’t afford that on your salary... Maomao presumed En’en was making the same amount she was, which would definitely put the finest makeup out of reach. Maybe she was getting a stipend from that uncle of Yao’s that she hated so much?

“Welcome, ladies,” said the proprietress, a middle-aged woman who sounded as refined as she looked—which was quite refined indeed. Her makeup was perfect, as befitted someone who sold the stuff. Her skin was pale and her mouth was perfectly highlighted with rouge. A simple hair stick held her hair up, but closer inspection revealed it was lacquered. Her nails were likewise perfectly painted, complementing her skin tone. I can see why the old hag would shop here, Maomao thought. The ladies of the pleasure district always had to be on the cutting edge of style—as of course did the madam who managed them.

The proprietress continued to smile but didn’t approach them. She would be there if they had any questions.

“How about we start with powder?” Yao said, standing in front of a shelf boasting an array of white powders, a whole range of them, organized by ingredient. They went from pure white to varieties that included some sort of dye or pigment to match a range of skin tones. Everything was neatly arranged—but one shelf had nothing on it.

“Excuse me, are these sold out?” En’en asked.

“Ah, those...” The proprietress walked over, an aroma of perfume wafting after her. She was a slightly built woman, and her pale skin made her seem almost like she might vanish at any moment. “The items that used to be on that shelf were prohibited when it was discovered that they contained a toxic ingredient. It’s a shame; they always sold very well. They held to the skin quite nicely.”

Hoo boy, do I remember that, Maomao thought. So the ban on the poisonous whitening powder hadn’t stopped at the walls of the rear palace; it had evidently gone into effect all over the capital. That was laudable in its own way, but it had to be a blow to businesspeople like this woman.

“That’s a lot to get rid of,” En’en observed.

“Yes. We offer a wide enough range of products that we were able to absorb the loss, but some establishments are still offering the toxic powder, or so one hears.”

Not hard to understand. The stuff coated the skin well, making the wearer look pale and beautiful. One of the main ingredients was quicksilver: it didn’t go bad like plant-based cosmetics, and it could be mass-produced, making it easy to buy. There were plenty of courtesans who had continued to use it despite Luomen’s warnings. There would always be fools who didn’t listen, just like the ladies of Consort Lihua’s Crystal Pavilion.

Well, maybe “fool” is being ungenerous. Some people might have something they valued more highly than their health or even their lives. As for those who sold the poisonous stuff, well, were they so different? Without money they couldn’t eat, and if they couldn’t eat, they would die. And some people wouldn’t hesitate to shorten the lives of others in order to extend their own. Maybe the merchants dealing in the toxic powder had no other way to make a living. Not to say Maomao thought it had been the wrong choice to ban the substance, the very production of which could have deleterious effects on the body.

And then there’s this stuff, she thought, picking up another powder. “Is this calomelas?” she asked. This was another white powder that her father had looked less than pleased about. It, too, contained mercury, which was also sometimes used as a treatment for syphilis.

“Indeed it is. Thankfully, it’s helped make up much of the shortfall in sales,” the proprietress said.

Calomelas should probably have been regulated too, but if you started saying “this is poison, and that’s poison, and that’s poison” and ordered everything off the market at once, it might actually inspire even wider circulation of the problematic products. They would have to pick their moment to implement new rules.

“Maomao, which do you think would be best?” En’en asked. She and Yao had picked out a selection of possibilities—wisely excluding anything that used calomelas.

“Rice flour and talc?” she said. Both appeared to have other ingredients as well, but they weren’t described in detail. “May I try some?”

“Go ahead,” the proprietress said, using a cotton bud to dab a little on Maomao’s palm. Maomao checked the viscosity and the smell. Both okay. Quite good, in fact. She thought this powder might be almost on par with what Empress Gyokuyou used.

“What do you think?” En’en asked.

Maomao glanced at the proprietress. “Honest opinions, good or bad, help us improve our products and service,” the woman said. So she didn’t just sell decent products—she was a decent person. No wonder she could handle the madam in a business negotiation.

“I think both seem like excellent powders,” Maomao said. “The particles are fine, and they hold to the skin well. I have a question about the rice flour powder.”

“What’s that, may I ask?”

“Rice flour can rot. And given the size of the container, I have to think that during the rainy season, it would start to go moldy before you got halfway through it. I assume there’s some additional ingredient added as a preservative, and it makes me somewhat uneasy not to know what it is.” Knowing that Yao would be using the powder, safety was foremost in Maomao’s mind. “Talc doesn’t go bad and isn’t toxic. I think this one would be the simplest to use.”

Talc had diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties, and was often used medicinally with bracket fungus. In all the times Maomao had used it, she’d never known it to cause any undesirable side effects. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t have any, but I won’t know until I encounter them, she thought. Vigilance would be her watchword until she was sure.

“You’ll take the talc, then?” the proprietress said.

“No, ma’am. I think they both have an admixture. I’m concerned—if it’s anything that’s bad for you, it would defeat the point.”

The proprietress frowned subtly at what might have sounded to her like nitpicking. En’en, meanwhile, was thinking the matter over; Yao, evidently having decided to leave things in En’en’s hands, was eyeing some eyebrow pencils made out of spiral shells.

“In that case, perhaps some of this,” the proprietress said, going into the back of the store and emerging with a ceramic container. It was about half the size of the one on display. “Our rice powder is made exclusively with plant materials. Why, you could eat it if you wanted. Would a size like this be more in line with the amount you’d be using? Or if you’d prefer to bring your own container, I would be happy to fill it for you. With, of course, a discount for bringing your own holder.”

This lady knows how to make a sale, Maomao thought. She was trying to cultivate repeat customers by addressing their needs directly.

“Would you specifically recommend this powder?” Maomao asked.

“Certainly. I use it myself. It sticks beautifully. Very easy to use.” A look at the woman’s skin showed that it was, indeed, excellent stuff. Yet still something nagged at Maomao.

Yao wandered back up and said, “Why not just go with the rice flour powder, En’en?”

“It’s not a bad idea,” En’en said. “I could try to make some myself, but I don’t think I could ever get it so fine.” She’d apparently considered making her own powder to ensure it was safe, but there was no substitute for a specialist. And Maomao assumed the proprietress wouldn’t be generous enough to reveal the secrets of how she made her wares.

“In that case, we’ll take—” Maomao was interrupted by a young woman who emerged from the back of the store.

“Mother!” she said.

“I’m with a customer,” the proprietress replied. A frown crossed her face. Nonetheless, her daughter, with a quick, polite bow to Maomao and the others, began to whisper into her ear. Whatever was going on, it seemed to be urgent. As her daughter talked, the woman’s expression changed. Finally she said to Maomao, “I’m terribly sorry. I’ll be right back. If you’ll excuse me.” Then she left her daughter to take care of things and went to the back.

Some kind of trouble? Maomao wondered. She was curious, but it wasn’t her place to stick her nose into whatever was going on. The woman’s daughter wrapped up their purchase and did the bill. En’en took the change, which had white smears on it.

“Oh, pardon me,” the young woman said, taking back the whitened coins. Maomao saw that her fingertips were white, and the fresh change she pulled out to give them was quickly smudged as well. Even their package had a white smear on it. “Oh, no! I’m so terribly sorry!”

“It’s all right,” Yao told her.

“Were you checking the merchandise?” Maomao asked with a glance at the young woman’s fingers. Three of the fingers on her right hand were whitened, as if she had been taking fingerfuls of powder to check the feel.

“I’m impressed you noticed,” she said.

“Let me guess: you discovered something unusual about the powder and felt it was worth mentioning right away.” The young woman didn’t respond to that, but her face made it clear that Maomao had guessed right.

“Was there something in the powder there shouldn’t have been?” En’en pressed. They’d picked the best stuff they could find, but if there were impurities in it, then what was the point? “What is it?” she said, leaning closer to the young woman.

“En’en,” Yao said, holding her back.

The young woman was on the verge of tears. “I... I’m so sorry. We got a new dealer recently. He insists he’s brought us exactly what we ordered, but it just doesn’t feel right to the touch. When I asked him if he was sure he hadn’t added any other ingredients, he snapped at me to stop trying to talk my way out of our deal. I was scared, so I came to let my mother know...”

An unsavory merchant? Or an honest misunderstanding? Maomao wondered. The dealer certainly sounded shady, but she’d only heard the young woman’s side of the story. The proprietress still hadn’t returned. Whatever they were talking about back there, it was taking a long time.

“My mother doesn’t want to sell a product if she doesn’t know what’s in it. The powder that was brought in today uses the same formula we always use, so we should be able to tell whether anything is wrong by touch. But the man who brought it today says we don’t have any proof of our accusations and refuses to leave.”

Hmm. Maomao crossed her arms. En’en was obviously deeply concerned about whether there was anything mixed into the white powder, and Yao—bless her earnest heart—looked ready to give someone a piece of her mind. Maomao suspected the exact feel of rice flour could change depending on how and when it was used, but it looked like there were some unanswered questions here. Well, can’t go home now.

“If you’ll pardon me,” she said, opening the door to the back room. She found the proprietress and the dealer locked in a staring contest. Between them sat a large jar.

“I told you! I followed the formula exactly as you gave it to me! Tell me what you think I got wrong!” The merchant, a man not quite in middle age, was shouting so loud that spittle flew from his mouth, which was open wide enough for Maomao to see that several of his front teeth were missing.

The proprietress didn’t back down. “Oh, I know what you got wrong. There’s something in this. You added something. It doesn’t feel like it should.”

“You won’t shut up about the feel, but that has nothing to do with anything! The feel of rice flour changes with the humidity, and you know it!”

They were talking past each other. Nothing was going to get resolved at this rate. “Excuse me. It looks like this discussion isn’t going anywhere,” Maomao said.

“Oh! I’m afraid you really shouldn’t be back here, miss,” the proprietress said when she noticed Maomao, giving her a look of reproof. Her tone remained deferential, but her eyes were grim.

“I’m sorry, my dear, but as you can see, we’re in the middle of a business negotiation. Maybe you’d be so good as to wait outside until we’re finished,” the merchant added, likewise polite but implacable.

Maomao ignored both of them, peering into the jar. It was filled to the brim with white powder. There was a spoon inside, so she scooped up some of the merchandise.

“What do you think you’re doing?!” the merchant cried.

Maomao put a finger in the powder. “It’s rice flour, all right. Would this be the same stuff my companions and I were about to purchase?”

“No, not quite,” the proprietress said. “The price of rice flour shot up recently, you see... We asked another dealer to produce something with the same formula...” She didn’t quite seem to want to finish any of her sentences.

An increase in the price of rice flour? It was the season when new rice was usually readily available—had the harvest been worse than usual?

She could tell from the feel that this was, in fact, rice powder. It was smooth, and about the same color as the stuff they were on the verge of purchasing. She agreed too, though, that it felt somewhat different under her fingers than the powder she’d been handling earlier.

“You can tell, can’t you, miss? Tell her my product is unadulterated! This stubborn mule is just trying to get me to lower my price!”

“A mule! I take pride in being able to offer my customers only the safest products! Every detail matters when it’s going to go on someone’s skin.”

Maomao could see both their perspectives. The merchant was right that the consistency and texture of rice flour could change with the weather—which wasn’t very good today. It could simply be more humid than usual.

“I’m afraid I can’t purchase this if we don’t know for certain which of you is telling the truth,” En’en interjected. She took a hard line when it came to products that Yao was going to use.

“Shall we do a little test, then?” Maomao said.

“Test?” the others asked in unison.

“You told us this rice flour is made entirely of plant components, all safe for human consumption. In which case...” She was going to try to eat it.

“You’re going to eat it? The powder?” the merchant asked.

“It’ll give you an upset stomach if you simply eat it dry. Perhaps if we dissolved it in water and made a baobing flatbread out of it?” the proprietress suggested.

“H-Hold on! You think you’ll actually be able to tell?” Yao said.

“I’m very confident in my tongue,” Maomao replied. She hadn’t done all that food tasting for nothing. She turned to the proprietress and the merchant. “Just to be sure—there’s no buckwheat in this, is there?”

“Corn, yes, but no kind of wheat,” the merchant said.

No problem, then. The corn would explain the powder’s slight yellow tint. “I’ll need a bowl and some water, and also a pot and a flame.”

“Ah... Our house is right behind the store. You can use the stove there,” the proprietress’s daughter said. She was probably concerned about the possibility of an explosion if they lit a fire in a space full of white powder.

“Very well. Finally, do you have any leafy vegetables and some chicken?”

“Focus. Please,” En’en said, giving Maomao a rap on the back of the head. She’d just wanted to make the powder as tasty as possible. Maomao picked up the jar and headed for the main house.

The finished flatbread was tasty (although not as tasty as it would have been with some greens and meat). “In a perfect world, I think a little more corn might have been nice. And some white-hair scallion and lamb’s meat to round it off.”

“Maomao, we’re supposed to be talking about the powder.” En’en had cut up the bread and was conducting a visual inspection. She appeared to be thinking that flatbread might make a nice dinner. “Maomao says it’s okay, young mistress, so I don’t think the white powder should be any problem as such.”

“Uh... I think everyone is getting pretty impatient,” Yao said, concerned.

“You see? It’s just like I told you. You keep insisting I must have added something, but I followed your formula exactly. There’s nothing wrong with my product!” The merchant slammed a wooden writing scroll containing the list of ingredients on the table.

The proprietress and her daughter both looked like they wanted to offer a rebuttal, but there was nothing they could say. They still weren’t prepared to accept they’d been wrong.

“Would you like some? It doesn’t taste unpleasant,” Maomao said.

“But...” the proprietress started.

“But it felt different to you, didn’t it?” Maomao took the woman’s hand. Her fingers were caked with white powder; it was even on the red of her nails. “Perhaps you could think of it another way, then.”

“What do you mean?”

Maomao wiped the pad of one finger across one of the woman’s fingernails, leaving a white streak. She’d been wondering about the woman’s nails. “What if it was your previous supplier who’d been adulterating his product all this time?”

The woman went almost as pale as her product.

When a person came into contact with a poison, such as arsenic or lead, it often showed in their fingernails. “You said yourself that some other stores continue to sell the prohibited whitening powder. There could easily be merchants who continued to supply it without saying anything. Suppose, for example, that they had white powder of questionable quality, and added something to it as a stabilizer.”

The symptoms of the poison would be minimized by the quantity of other stuff in the mixture. But someone who used the powder every day, like the proprietress did, would show the signs.

“Have you had any loss of appetite? Poor digestion? Trembling of the fingers?” Maomao asked. She wondered how the woman’s skin tone looked beneath that makeup. The woman’s expression was enough to answer her questions.

“So you’re saying this—” En’en looked at the jar of powder they’d bought. Maomao took it and opened the lid.

“Shall we try another flatbread? With this powder?”

She was most interested to see the results.

It was dark outside when they left the shop. The heavy clouds had opened up, and the ground was soaked. “Shoot! We’re going to get all wet,” Yao said.

“I thought this might happen,” said En’en, pulling out some umbrellas Maomao hadn’t even known she had.

“You brought umbrellas?” she asked.

En’en tapped the sign of the store they’d just left. “It looked like it might rain, so I asked the shopkeeper’s daughter to go buy some for us. Not too much to ask for our trouble, I’d say, right?”

“When did you... I mean... Too much to ask?”

True, the shop had sold them a harmful product, whether intentionally or not. When they’d dissolved their powder in water and baked with it, the results had been undeniably different from the first time around.

“I think you already asked quite a lot,” Yao said. En’en was carrying some of the new, safe powder, and the proprietress had thrown in some perfume that was supposed to be good for your skin. The aromatic oil was safe to eat but didn’t hold to the skin very well, so it could be combined with the powder to form a liquid makeup.

“Not at all,” En’en replied. “I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if my mistress got sick.”

“I think you should be talking to Maomao. Tell her not to put awful stuff in her mouth.” Yao was looking at Maomao as if she still couldn’t believe what had happened. Maomao had made every effort to eat the flatbread with the poisonous powder, but Yao had pinned her arms to stop her.

“I would have spit it out right away. It would have been fine. I just wanted to see how it tasted.”

“I don’t understand what you see in these things,” Yao sighed.

“Let’s finish our shopping before the rain really starts coming down, mistress. We’ve eaten up a lot of time.” En’en opened an umbrella and ushered Yao under it with her. Then she held out another to Maomao. It was En’en, of course, who had requested only two umbrellas. After all, two people could fit under one umbrella...if they squeezed.

En’en said, “If anyone is still selling ingredients at this hour, I’m sure they’d be near the bell tower. I think the market should still be open there.”

The bell tower was at the center of the capital and rang the hours. It was a well-trodden area, so the shops there stayed open until late.

“We should be hearing the evening bell any minute n—” Maomao said, but she was interrupted by a searing flash of light accompanied by the booming of the bell.

“Yikes! Wh-What was that?” Yao said, looking around in astonishment. At the same moment, an earsplitting noise followed hard upon the ringing of the bell. Yao almost jumped out of her skin and clung to En’en. Her mouth was working open and shut, but no sound came out. En’en gave Yao a protective (and none too unhappy) hug.

“Thunder,” Maomao said. “That was a big one.”

“Are you all right, milady?” En’en said.

“Y-Yeah! I’m fine!” Yao said, although her face was awfully pale.

“A thunderclap that loud means it’ll start pouring soon. Shall we hurry and finish our shopping?” En’en said.

“Y-Yeah, let’s,” Yao said. She was trying to look unintimidated, but kept stealing little glances at the sky. En’en looked at her fondly and kept close. No doubt she was concerned for Yao, but also tickled by her display of fear. She was a twisted one. But Maomao already knew that.

Looks like I won’t be selling these today, Maomao thought, looking at the Go books in their cloth wrapping. Then she trotted off after the others.

Chapter 3: Trends

Jinshi’s office looked much the same as it always did: mountains of paperwork, bureaucrats waiting their turn to speak with him, and the occasional court lady appearing from nowhere trying to get a look at him. It was bustling, no doubt, but it was substantially calmer than it had been not long ago.

His usual workload, which already kept him busy, had doubled since the shrine maiden from Shaoh had come to Li. He’d arranged a banquet in her honor, during which she had been poisoned, and Jinshi had spent many a sleepless night pursuing the case. Ultimately, it turned out to be all the shrine maiden’s own doing, a whole act, but that was no small problem in itself. It was enough to leave him with his head in his hands.

The shrine maiden had survived the entire affair and was now living with the former consort Ah-Duo. Jinshi felt a bit bad about the way her home was turning into something of a safe house. The shrine maiden had left him with troubles of his own, though: he, along with a small number of others, had had to deal with the fallout of her “death.” A number of officials were convinced that Shaoh would use the shrine maiden as a pretext to attack Li, but no such offensive materialized. Shaoh was principally a commercial and trading power; they couldn’t start a war without substantial backing from someone else. If anything, the leaders of Shaoh were probably breathing a sigh of relief to be rid of the shrine maiden, who had been something of a thorn in their side.

Shaoh had made some demands over the incident, but they were nothing that Li hadn’t anticipated. They wanted import duties reduced, particularly on foodstuffs. No one had expected them to come right out and say they didn’t have enough food. The shrine maiden knew Shaoh’s king and bureaucrats very well—their personalities and sense of political judgment. Nothing they did or asked for was unexpected. In fact, Jinshi was almost set back on his heels by the extent to which everything had followed the script. Which wasn’t to say international issues were simple. So it was that until a few days before, he had been so busy that the amount of work now felt like a relief.

“This is for you, Master Jinshi,” Basen said, putting another paper atop the towering pile. And to think—this was after Jinshi had delegated more than half the work.

“I don’t suppose we could delegate half of what’s left,” he said.

“I don’t suppose, sir...”

The paper bore the personal chops of a number of high officials, and the civil servant on whom Jinshi had foisted the work couldn’t ignore something with so many important seals on it. Such petitions inevitably ended up on Jinshi’s desk, even if they concerned trivial matters. He sighed and pressed his chop to the paper.

Amid the bustle, one of the bureaucrats handling some of Jinshi’s work stood up, looking restlessly in his direction. It was the same man who’d been with Jinshi when someone had attempted to poison his tea. He’d entered Jinshi’s service to help until Basen was fully recovered, but he’d proven capable enough that Jinshi had asked him to remain. The man seemed eager to get back to his ordinary place of work, but the eternally understaffed Jinshi was loath to let him go.

“What’s the matter?” asked Basen.

The man flinched. “N-Nothing...”

He seemed awfully anxious for someone who thought nothing was wrong. Now that Jinshi thought about it, he realized the man had been acting a little funny for a few days. Curious now, Jinshi narrowed his eyes.

“Is it really nothing? I want the truth.” This interrogation came not from Jinshi, but from Basen, who had cornered the man. Strange things, dangerous things, had been happening around Jinshi of late, and Basen—who was responsible for Jinshi’s safety—was on edge. If he waited to act until after something happened, it would be too late.

“H-Heek!” The bureaucrat’s face was taut with fear. He reached into the folds of his robe with a shaking hand, whereupon Basen was on him, pinning him down. He could be merciless when he thought someone was hiding something.

“Who put you up to this?” he demanded, grabbing the man’s wrist. Clutched in his hand was a scrap of paper.

“Let him go, Basen,” Jinshi said, relieving the man of the paper. He looked at it—and let out a sigh. “Is this what was making you so nervous?”

“Huh?” Basen looked puzzled—indeed, downright flummoxed.

“Ow, ow, ow! Please let me go,” the bureaucrat said.

Basen obliged, instead looking at what Jinshi had in his hand. “What’s this?”

“I don’t know when he had time to make such a thing, but it’s quite thorough, isn’t it?” Jinshi said. The paper announced that someone would be putting out a book. The date given was that very day, when, so the paper proclaimed, the book would be available at bookstores all over the capital.

“I... I really wanted one. Once a book sells out, you never know if you’ll be able to get a copy,” said the bureaucrat, rubbing his arm. He looked on the verge of tears. Judging by the look on his face, Basen at least had the good grace to feel guilty.

Books were luxury items—except for the most popular titles, second runs were uncommon. If a book sold out before you could get a copy, all you could do was wait for it to appear on the used market.

“If they’ve gone to all the trouble of distributing an announcement, don’t you think they probably plan to have a lot of stock ready?” Jinshi said. Printing in and of itself implied they were planning to make a lot of copies. You had to, to recoup the costs.

“I-I couldn’t say, sir. I expect it to be very popular...”

“Is the author so beloved?” Jinshi asked, looking the paper over as carefully as he could. Printing and distributing announcements like this to anyone and everyone—that was a new idea. He couldn’t help but be impressed. Whoever could have thought of it? Then he saw the name—and almost choked. He immediately wished he could unsee it.

Basen was giving him a puzzled look. “Grand Commandant Kan, sir?”

When Jinshi saw the title of the book, he understood. Kan was a reasonably common name. But Grand Commandant—that was a title, and only one person in the country held it. Kan Lakan, otherwise known as the freak strategist.

“Would you mind telling me who gave this to you?” Jinshi asked.

“A f-friend of mine at the Board of Revenue. An acquaintance of the Grand Commandant’s son. He was asked to give them to everyone he knew.”

The Board of Revenue was the department charged with overseeing financial matters—and the friend of a friend was Lahan. If he had a hand in this, then the book would be more than a passing fancy on the part of the strategist. It would be done well.

“So he’s written a Go book,” Jinshi mused. He had, he recalled, heard that the strategist had been going around telling people he was going to write such a book. Jinshi simply hadn’t imagined the project taking place on such a scale.

As far as it went, he appreciated the help in making books more universal. He himself had been trying to promote paper and printing projects. He was surprised, though, to discover that even this unassuming and dedicated bureaucrat lusted after a copy of the strategist’s book.

“I never realized the honored strategist had the gift of belles lettres,” he said.

“Who cares whether his lettres are belles?!” the bureaucrat said, going from grumbling to garrulous in the blink of an eye. “It’s almost impossible to understand what he’s talking about, anyway. But they say the book will contain records of Grand Commandant Kan’s games! No one would want to miss that!”

Jinshi thought he’d caught a rather uncomplimentary reference to Lakan in there. But in any case, some people really got fired up over their personal interests, and in this man’s case, that interest appeared to be Go.

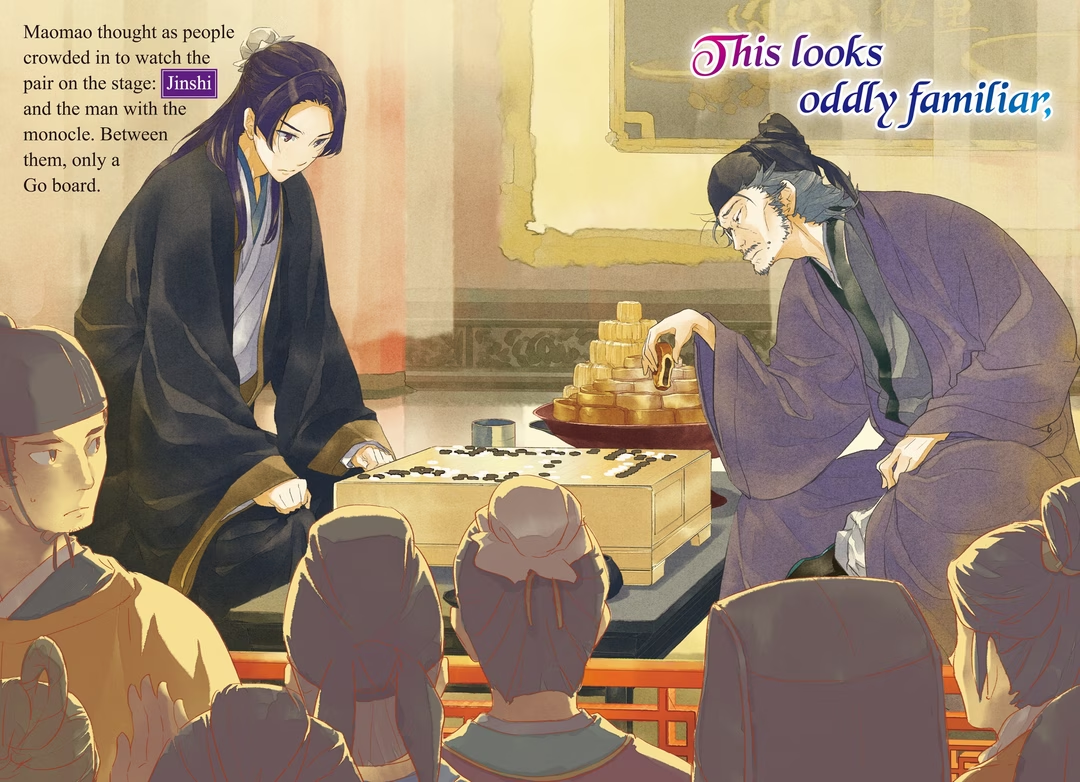

“I only have a passing acquaintance with Go. Is Grand Commandant Kan that good at it?” Basen asked, more perplexed than ever.

“That good?! Why, the only person in the country today who stands any chance of beating the Grand Commandant is His Majesty’s own Go tutor!” The Emperor’s tutor held the rank of Go “sage”—meaning he was the best player in the nation. Jinshi himself had had a few lessons from the man. How many stones’ handicap had he had the last time they’d played together? He couldn’t remember.

“Grand Commandant Kan is known for the elusiveness of his play. You never know what he’s going to do next, how he’ll come at you. A chance to study and understand his records is a mouthwatering prospect for any connoisseur of the game.” The bureaucrat clenched his fist emphatically. His eyes were shining now. His delight in the subject seemed to have overwhelmed his resentment toward Basen over the manhandling.

“Yet even the Grand Commandant is only human. Surely no one is truly unbeatable?” Basen said. Another not particularly polite way of talking about the strategist—but also true. Jinshi had to agree with him.

“How can you say that?” the bureaucrat said. “Yes, the Imperial tutor is victorious over the Grand Commandant in six out of ten games—but the tutor is a professional player! The Grand Commandant has a real job he must attend to!”

Jinshi didn’t say anything.

“To say nothing of the fact that no one at all can beat him at Shogi.”

Basen didn’t say anything.

Jinshi realized he really was very bad at handling people. “Very well. Basen, do you have your purse with you?”

“Er, yes, sir.” Basen produced his wallet from the folds of his robes. Jinshi handed it to the bureaucrat, who looked from him to Basen and back, suddenly nervous again.

“It’s not much, but take it. A modest recompense for the discomfort Basen caused you,” Jinshi said.

“S-Sir, I couldn’t... It’s not even his...”

It was, sadly and indeed, not Basen’s purse. The young man simply held on to Jinshi’s money in case there was a need to purchase anything. Jinshi knew little about market prices, but he figured this would be enough to compensate the man for his troubles.

“I’m sure your hand must be hurt. You should leave work for the day. Go to one of those bookstores. I assume that purse will cover the cost of a book.”

“A-And then some, sir! I can’t accept this,” said the bureaucrat, who was proving too honest for his own good. He should have just taken the money, Jinshi thought. Very well. He would try a different approach.

“What are you talking about? I don’t mean just one book! Make sure you get one for me as well. And if there’s money left over, then one for Basen too. What are you waiting for? Go! Go, before they’re sold out! Or are you hoping for some hush money?”

“Not—Not at all, sir! I’m going!” The bureaucrat hurriedly showed himself out of the office.

Jinshi listened to his footsteps fade, then let out a sigh. “Basen. It’s not polite to pinion somebody with no warning.”

“Y-Yes, sir. But he could’ve...” Basen at least sounded apologetic.

“In any case, what’s done is done. You didn’t break his arm. You’ve learned at least that much control.” Jinshi knew that with Basen’s preternatural strength, that bureaucrat’s arm could easily have been pulverized. Jinshi would give Basen this much: he was growing up a bit.

“Master Jinshi, if you’ll forgive my saying so, I don’t have any interest in Go.” He seemed to be referring to Jinshi’s instructions to the official to bring a copy of the book for Basen.

“Interested or not, it can’t hurt you to learn. Even the most sheltered young lady at least learns to play Go. Suppose you meet a prospective marriage partner but find you have nothing to talk about—you can at least play a game together. Who knows where it might lead?” He was trying to be lighthearted, but Basen went beet red.

“I-I’m sure... I’d never... N-No such young lady and I would ever...” Basen fell silent before he ever succeeded at getting out a complete sentence. Jinshi gave him a curious look. When he sat back down at his desk, he felt a pang of remorse: the mountain of paperwork was still there, but now his helpful bureaucrat was gone.

Within a few days, every palace, pavilion, and hall of the court resounded with the click, click of stones on boards. On the way to his office, Jinshi noted that even the soldiers in the guardhouse were playing Go.

“It’s become quite the trend,” Basen observed.

“Indeed,” said Jinshi.

Needless to say, it was the freak strategist’s book that had started this craze. Jinshi himself was carrying no fewer than six copies of it. Why so many more than the single copy he’d requested from the bureaucrat? They’d arrived for him accompanied by a short note: Someone gave these to me. Help yourself.

They’d come from the apothecary, Maomao. He assumed, much to his sorrow, that she hadn’t sent them out of affection for him. More than likely, she was just trying to get rid of stock. He knew her; she would never go out of her way to buy a book by the strategist. They must have been sent to her in copious quantity. He sometimes wished he could ask her if she really understood the meaning of what he’d said during their last encounter.

Maomao was the strategist’s daughter, and although she herself seemed intent on disavowing Lakan, from Jinshi’s perspective the family resemblance was obvious. In any case, she certainly wouldn’t want to be stuck with a gift from the father she so detested.

Jinshi didn’t feel the money he’d given the official had been wasted, but still, he wasn’t quite sure what he was going to do with six copies of the same book. Basen already had a copy. Maybe he would try giving them to Gaoshun, Ah-Duo, and the Emperor. The apothecary’s thinking might have been similar to his—or not. He knew her to be strong-willed and careful, so it might be best to assume she had some sort of ulterior motive.

Jinshi had started by thinking about Maomao’s books, but soon he found himself thinking about Maomao—specifically, how he might talk her into accepting his proposal. He would have to prepare, set everything up so that she had no comeback and no reason to refuse. He wanted to be a man who did what he said he would.

Still lost in thought—and under scrutiny from court ladies who watched him from afar—Jinshi arrived at his office. An official standing outside came over looking frantic when he spotted him. It was Basen, however, who asked, “What is it?”

“Pardon me, sirs. But if you would look at this...” The official handed Basen a letter. He opened it and read it. His eyebrows twitched. Jinshi looked at the missive, but remained expressionless as he entered his office.

“Send a damage assessment immediately,” he instructed.

“Sir!” the official said, and went out again. Jinshi trusted that a messenger would be sent if there was anything new to report.

Finally, he sighed. “So it’s come.”

The paper had read simply: There has been a plague of locusts.

There had been reports of small-scale insect swarms, but while Jinshi had seen the memos, the matters hadn’t been substantial enough to warrant his personal involvement, and he’d been obliged to let his subordinates handle them. None of the other outbreaks had been too large, but this...

“So we’re going to lose thirty percent of the harvest,” Jinshi reflected. That was a major blow. He pricked up his ears when he heard that the location of the outbreak was to the west, a major grain-producing area. “Isn’t it a bit late for the wheat harvest?” he asked.

“It’s not the wheat that’s been hit—it’s the rice,” answered Sei, Jinshi’s Go-loving bureaucrat. Other than his timid streak, the man was proving quite capable. “For about twenty years now, they’ve been experimenting with growing rice in the area using large-scale irrigation. From one perspective, this could be considered fortunate. Only the areas with unharvested rice were affected. We were lucky this didn’t overlap with the wheat harvest.”

“They’re drawing water from the Great River?” Twenty years ago would have been just about the time Jinshi had been born. He did recall hearing something about a major flood control project that had taken place around then. They must have built something to divert the water at the same time.

“Yes, sir. It was purely a local endeavor, something they tried out in a couple of places. The rice harvest is more reliable than wheat, but if they made the scale too grand it would impact everything downstream. As such, the project never got any larger than it already is.”

Twenty years back—that would have been the time of the empress regnant. She’d been a woman among women, not afraid to experiment with even the most outlandish policies. Sei drew a large circle on a map. Jinshi observed that while it wasn’t too close to the capital, it wasn’t so far away either. Four or five days’ round trip, perhaps.

The paperwork still formed a mountain on his desk. He looked first at Basen, who had stayed silent throughout the conversation, and then at the obviously nervous Sei. The last thing he wanted was to make more work for himself or either of them. But he just couldn’t leave something alone when it had his attention like this. He stifled a groan.

“I-If I may?” Sei raised a hand hesitantly.

“Yes?” said Jinshi, trying his best to maintain a neutral expression.

“I w-wouldn’t wish to be impertinent, Moon Prince, but is it possible y-you’ve taken on a bit too much work?”

“It is possible, and I’m well aware of it. But what exactly am I supposed to do about it? These matters can hardly be left to anyone else.”

Sei blanched slightly. “I hardly d-dare to say this, sir, b-b-but...” His eyes seemed to look everywhere except Jinshi’s face. “Other honorable personages have been known to entrust their subordinates with—”

“What injustice do you speak of?!” Basen demanded, slamming his fist down on the table. Sei yelped and cowered. “Who would have the audacity to do such a thing? Speak up! You must know something!”

Basen closed in on Sei, but Jinshi held him back. “Basen. You’re scaring him. I would, however, be interested in the answer to his question. Who is doing such things?”

“Er... Er... Grand Commandant Kan, sir.” It would certainly be plausible for the “honored strategist” to engage in such behavior, but the look on Sei’s face said he was hiding something.

Jinshin leaned in. “May I assume he’s not the only one?” Sei’s cheeks flushed. Jinshi had been under the impression that he’d managed to avoid picking any personnel with those tendencies, but it looked like he was going to have to rethink putting his face too close to Sei’s. Jinshi brushed the scar on his cheek.

“A-Also...His Majesty the Emperor...”

Jinshi and Basen were both struck dumb.

“I-Is that good enough?” Sei said, looking studiously at the ground, obviously desperate for them both to leave him alone.

Basen wasn’t finished, though. “Who in the world could fill in for His Majesty himself?” He pressed toward Sei again, his breath hot in his nostrils.

“M-Master Gaoshun! He does it!”

Again the other two men had no recourse but silence.

“Of course, His Majesty puts his own seal on the documents when they’re ready. I j-just thought if you could have an intermediary, someone to clean and organize things, they might cut down the number of memorandums that actually reached you, Moon Prince, by two-thirds. If they were given the proper job title, surely they could exercise some personal discretion...”

Jinshi’s heart skipped a beat at the suggestion that he might have only a third as much work to do. Such important tasks, however, couldn’t be entrusted to some random bureaucrat—someone he might not even know.

Jinshi looked at Basen. He briefly entertained the idea that if Gaoshun could do such a job, then his son might be able to do it as well, but unfortunately, Basen wasn’t really cut out for desk duty. He was a diligent worker, but knowing his stern-mindedness and inflexibility, Jinshi suspected the jobs would simply back up. Was it being greedy, he wondered, to wish for someone with both the loyalty and family background to handle his work, who was also capable and judicious?

“Master Jinshi,” Basen said.

“Yes?”

“I do know someone particularly gifted at this kind of work...”

Jinshi’s eyes widened. “Do you? I hadn’t realized you had any acquaintances among the civil officials.”

“Just one, sir. Someone who passed the civil service exam last year, but presently languishes without an appointment.”

Jinshi realized he had an idea who Basen was referring to. “You don’t mean...”

“Yes, sir. Baryou. Perhaps you would know him better as Elder Brother Ryou.”

As his name implied, he, too, was a member of the Ma clan—Basen’s older brother.

Chapter 4: The Ma Siblings

Baryou: Gaoshun’s son, Basen’s older brother.

The Ma clan produced many members of a military persuasion, but Baryou’s talents ran more toward the literary and bureaucratic. As the eldest son, it was actually he and not Basen who should have been Jinshi’s attendant, but Gaoshun knew his offspring too well to do that to him. Instead of forcing him to practice swordsmanship, he gave him a book. Baryou had all the physical prowess of a limp bean sprout, but he took to academic studies like a fish to water.

Then, last year, he had taken the civil service examination, which was held only once every four years—and he had passed on his first attempt. Even the most jaded eye could see that Baryou had all the makings of a superb civil servant. Yet he was unable to get a job. Why? A quick look at his current situation explained much.

“Impressive. As I knew he would be,” Jinshi said. The papers that had been forming mountains on his desk had been reduced in height enough that you could see the other side. He let out a sigh of relief, and looked at where a man was working away silently in a corner of the room. His corner couldn’t be seen from the entrance, and anyway he’d placed a partitioning screen between himself and the room, so visitors wouldn’t know there was anyone there. Quite frankly, the man might have preferred to build four solid walls around himself, but Basen had discouraged that idea. And who was it behind this screen doing all that work?

“Master Jinshi...” said a man bearing an armload of paperwork. He was very slim, of average height, and his skin was so pale it bordered on sickly. He didn’t exactly look healthy, but it was oddly amusing to see how his face—and only his face—looked so much like Basen, the picture of physical fitness, who was standing beside him. This man was perhaps a good sun shorter than Basen, and the way he stooped made him look shorter still. If Basen hadn’t had such a baby face, it would have been hard to tell which of them was the older brother and which the younger.

But the stooped, feeble-looking man was indeed the older brother, albeit only by a year. Gaoshun’s other son, Baryou.

The Ma clan, as we’ve remarked, traditionally produced soldiers. The bodyguards of the Imperial family were typically Ma people, as Gaoshun was for the Emperor and Basen was for Jinshi. By right, it should have been Baryou who acted as Jinshi’s attendant. He was Gaoshun’s second child and oldest son. But this scrawny sprout of a man wasn’t made for guard work. Baryou was given the “Ba” name—the same character as Ma, reflecting the clan—but so was Basen, who was born the next year.

“Quick work. You’re finished already?” Jinshi said.

“I am, sir. With you a statue, the work is done.”

“I’m afraid I don’t quite follow.”

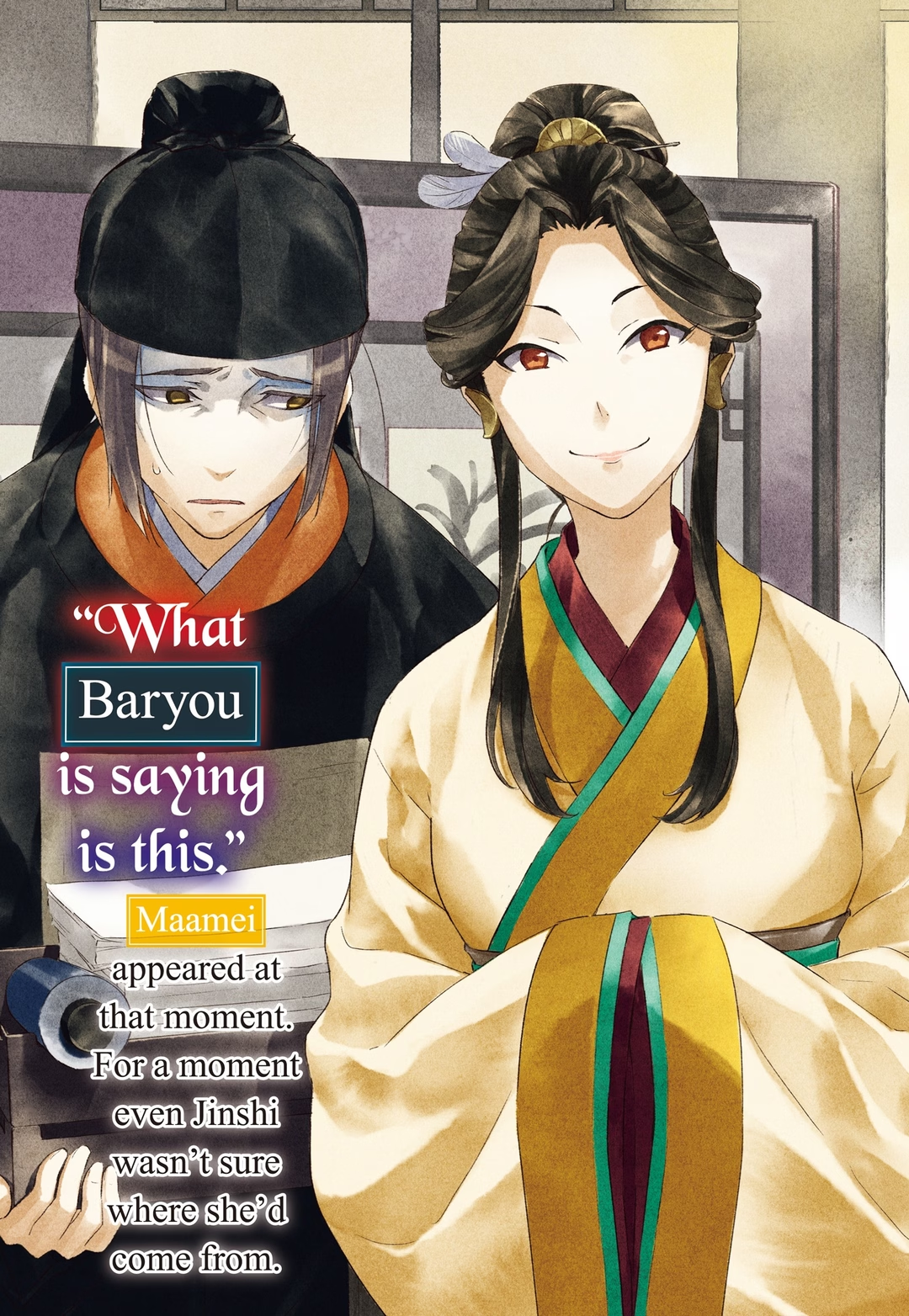

Baryou’s explanation seemed to be elliptical at best, a jump somewhere in the train of thought, and Jinshi didn’t understand what he meant. Thankfully, another person appeared at that moment—a tall and beautiful woman with a hard look in her eyes. For a moment even Jinshi wasn’t sure where she’d come from. Baryou could be seen wincing at her appearance.

“What Baryou is saying is this,” she said. “‘As you are as beautiful as a sculpted statue, Master Jinshi, one can hardly think of you as a human being. Thus even I, who find myself uncomfortable around human beings, can think of you as some creature by no means human, and therefore focus on my work.’”

Jinshi was quiet for a moment, unsure how to take that. He was quite casually being treated as inhuman. Then again, Baryou had always been like this.

The beauty with the cruel eyes who had interpreted for Baryou was his and Basen’s older sister. Her name was Maamei and she had two children of her own. Basen and Baryou resembled their father Gaoshun, but Maamei took after her mother, who had been Jinshi’s wet nurse. For that reason, Jinshi still found Maamei somewhat intimidating.

She resembled her mother in more than looks; she’d also inherited her strong will, and Jinshi was given to understand that Maamei quite dominated her husband. Until a few years before, she’d also regarded her father Gaoshun with all the affection she would feel for a hairy caterpillar, although she claimed that at some point she’d upgraded him to “moth.”

She was, however, also the only person Jinshi knew who could wrangle the otherwise difficult-to-handle Baryou. He might have passed the civil service exam with flying colors, but he had ended up quitting his job due to a combination of poor health and unique ideas. And given his minimal ability to build new relationships, he found himself the target of a good deal of resentment almost before he knew what had happened. His colleagues and superiors had come to dislike him before they’d ever had the chance to get to know him. All of it had ended up giving him a stomach ailment.

Talent Baryou had in spades, but his personality made things difficult. In that respect, he was somewhat like the members of the La clan, although they tended to combine their personal quirks with a forcefulness of spirit that left others with the upset stomachs. It was enough to make a person jealous of their brazen approach to life. If only Baryou could have half—for that matter, even one-tenth—the La clan’s disregard for what people around him thought.

Basen sighed and put the finished work on Jinshi’s desk. Jinshi started to review what Baryou had done, but one of the papers made him stop and frown. It was a circular that Jinshi himself had sent for approval to a series of other departments. Once again, it had been rejected as unfeasible. How many times was this now?

“So they really won’t do it,” he said.

“Rejected again, sir?” Basen asked.

“It’s the timing. If it were for next year, they would approve it.”

“The martial service exams are next year, aren’t they?”

“Yes. Someone thinks we should wait for those.”

What was this idea of Jinshi’s that was failing to get approved? It was to expand the military. He wanted more troops stationed in the north, but the proposal had been slapped down. The martial service exams were essentially the soldiers’ equivalent of the civil service test. They weren’t as well attended as the bureaucrats’ version, but still they would no doubt attract plenty of strong young men who would make excellent officers.

The military had been shrinking these past few years, for two reasons. One was a simple lack of wars, but the other was a personnel matter. Specifically, the two people who stood at the top of the military hierarchy.

“Grand Commandant Kan and Grand Marshal Lo,” Basen said.

The Grand Marshal was the highest-ranking civil official involved in military matters. The Grand Commandant, for his part, was considered one of the san gong, the three most important leaders of the country, and like the Grand Marshal, his was a military role.

“I must wonder how Grand Commandant Kan attained that title,” Basen said. Jinshi would have liked to know the same thing, but all he had to go on were some unsettling rumors. Some claimed that once Lakan had finished dispensing with all those who opposed him, there were no other high-ranking officials to take the post. Others said that he had been favored by the former emperor’s mother, the empress regnant, and that it was she who had guaranteed his swift rise in the world. Still others held that after ascending the throne, the current Emperor had set Lakan to taking care of any relatives who might envision themselves on the country’s high seat.

“Truth be told, I’m not sure,” Jinshi said. One thing he thought he knew, or at least could guess, was why the man had sought such great power. Maomao had spoken of it once, although with open disgust the entire time. She’d said that there was something he could not get without power. Lakan was a man who would do anything to get what he wanted—but there were not that many things he wanted. He wasn’t the kind to let his greed multiply endlessly.

“A military man ought to want a little more,” Jinshi grumbled. Someone who would make any pretext to have more pawns at his disposal would be easy to understand, easy to work with. But if Lakan had his board games, his family, and some sweet treat to enjoy, then he was satisfied. In fact, he wanted very little out of life, but he was irrepressible in action, and that was what made him such a thorn in the side of those around him.

“Perhaps if you were to try speaking directly with Grand Commandant Kan...” Basen suggested.