Character Profiles

Character Profiles

Maomao

Formerly an apothecary in the pleasure district. Downright obsessed with medicines and poisons, but largely uninterested in other matters. Has deep respect for her adoptive father Luomen. Twenty years old.

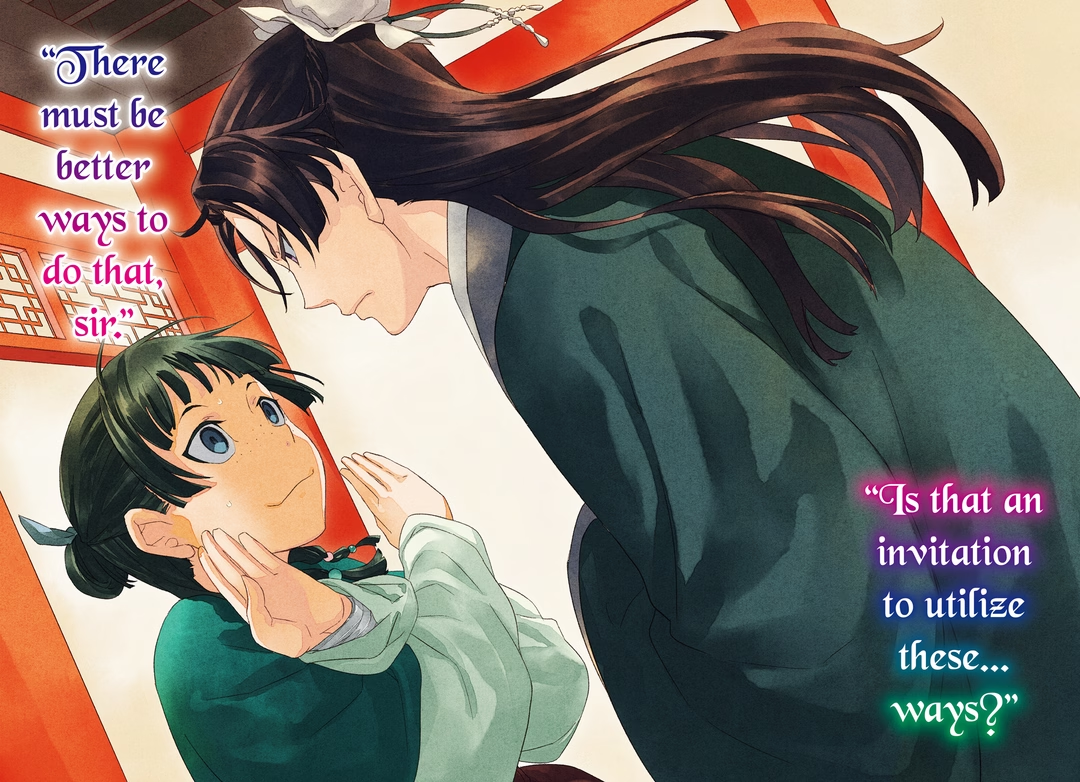

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. Inhumanly beautiful. He’s remarkably down to earth for someone so gorgeous, but there’s no telling what he might do if he lets himself go. Has an inferiority complex about his no-more-than-average intellectual abilities. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-one years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant. Doesn’t feel pain as acutely as most people, which gives him far greater physical capacities than most. He’s very serious, but that makes him easy to tweak. In love with Consort Lishu.

Gaoshun

Basen’s father. A well-built soldier, he was formerly Jinshi’s attendant, but now he serves the Emperor personally. He’s accompanying Jinshi on his expedition by order of His Majesty.

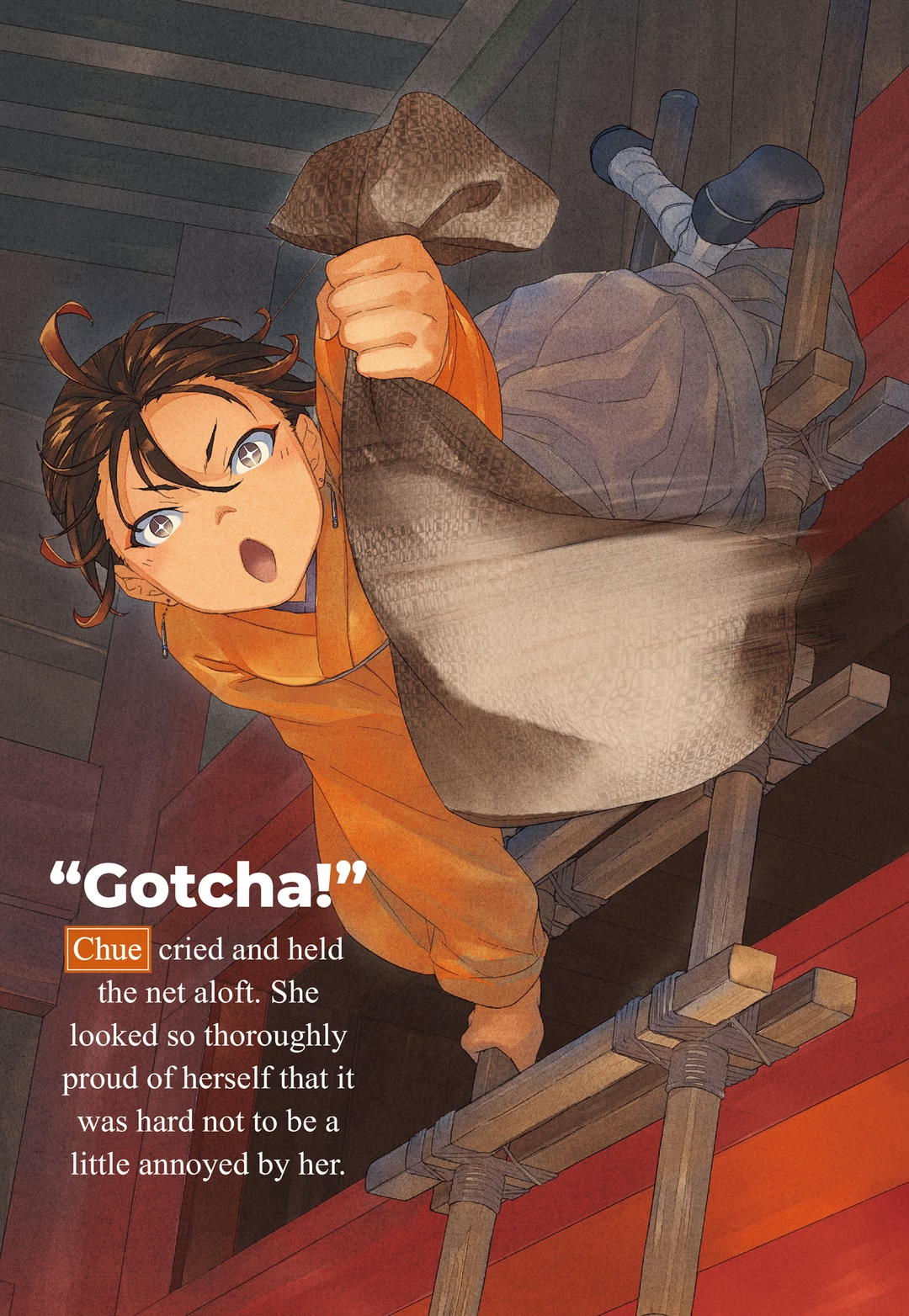

Chue

Baryou’s wife, and mother of his child. Not strikingly attractive, but she makes up for it with her initiative and silly personality.

Lakan

Maomao’s biological father and Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle. He’s a high-ranking member of the military, but his bizarre behavior causes people to avoid him. He loves Go and Shogi and is a formidable player.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. Twenty-two years old.

Rikuson

Once Lakan’s aide, he now serves in the western capital. He has a photographic memory for people’s faces.

Gyokuen

Empress Gyokuyou’s father. Officially the ruler of the western capital, but when his daughter ascended to the throne he moved to the royal capital.

Gyoku-ou

Gyokuen’s eldest son; Empress Gyokuyou’s half-brother. Currently leads the western capital while his father is away.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting and former wet nurse.

Taomei

Basen’s mother and Gaoshun’s wife. Blind in one eye. A “masterpiece of a woman” who reminds one of a predatory animal. Six years older than Gaoshun.

Baryou

Gaoshun’s son and Basen’s older brother. Spends most of his time hidden behind a curtain.

Tianyu

One of Maomao’s colleagues; a young physician. He can seem frivolous, and he has a thing for En’en. He’s quick to stick his nose in whenever something interests him.

Dr. You

An upper physician who hails from the western capital.

Lahan’s Brother

Older brother of Lahan; Lakan’s nephew and adopted son. A perfectly ordinary person who shines when offering quips.

Prologue

A bell tinkled, clear and distinct. The young woman who climbed out of the carriage had the same red hair as Gyokuyou. A veil worked with silver embroidery hid her face, and she wore a robe of wonderful, shining silk.

Gyokuyou wondered how old she was. The girl was supposed to be her niece, but she didn’t recall having any such nubile young relatives. All her nephews and nieces had been older than her, and so very mean. Yet her own brother, Gyoku-ou, swore this girl was his daughter, so it must be so. She had to go along with it.

“Lady Gyokuyou,” said someone behind her. It was Koku-u, the middle of a trio of sisters who served as her ladies-in-waiting. She gave her mistress a worried look.

“Don’t fret, dear one. Are we prepared to receive her?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Gyokuyou was at one of the Emperor’s villas. She’d received special permission to meet her niece here, outside the court proper. No consort was allowed to leave the rear palace, but Gyokuyou was the Empress. She had certain rights.

The young woman in the beautiful robe approached with graceful footsteps and knelt before Gyokuyou. “Lady Gyokuyou, I believe this is the first time we’ve met. My name is Yaqin.”

“Raise your head. You must be tired from such a long journey. For today, rest and regain your strength here in this villa.” Gyokuyou smiled at Yaqin. She could see the girl’s eyes behind the veil, deep green like hers. Everything from the color of her skin to the cast of her face spoke to a prominent strain of foreign blood.

She was quite charming on first impression, in fact. She had an innocence about her—still room to grow and mature—accompanied by the anxiousness of someone venturing into a world they knew little of. Deep within those emerald eyes, though, could be seen a determination working to assert itself.

They were much alike. Yes, Gyokuyou had looked much the same when she had first arrived in the capital, first come to the rear palace. Did this girl, too, harbor some private resolution? Let her. Gyokuyou would attend to her own business.

“How would you like your meal? We can make it in the style of the western capital for you. Or would you prefer to try the local cuisine?” Gyokuyou gave Yaqin a teasing smile; it enveloped the girl, who smiled back uncomfortably.

Her niece was here from the west, but why? Would she try to gain His Majesty’s Imperial affection now that Gyokuyou’s former place was vacant? Or did she have her eye on the Emperor’s younger brother?

For Gyokuyou’s purposes, it didn’t matter. She took Yaqin’s hand, and felt her niece stiffen.

“You’re so cold, and your skin is so dry,” she said. “Let me get you some moisturizer. The sea air is simply terrible for the skin.”

The girl was openly wary of Gyokuyou. If this was an act, it was a superb one. If it wasn’t, it only showed that they hadn’t spent long teaching her the tricks of gaining a person’s heart and mind. There was never enough time to teach a consort-to-be all the things she ought to know, dancing and singing and politics.

Gyokuyou took the moisturizer from Koku-u, then rubbed some on her own hand to demonstrate that it was safe. Her niece still looked doubtful; perhaps she was just that anxious. That was all right, as far as Gyokuyou was concerned. Let her be as suspicious as she wanted. Gyokuyou wrapped her in a smile as soft as silk. She would wrap her in layer after layer of smiles, until every thorn, every needle she might have was covered over. She would take the child into her bosom and hold her gently.

Gyokuyou rubbed her niece’s hand. Some might consider it unseemly, but the warmth returned to Yaqin’s fingers.

Koku-u was frowning, but she didn’t argue with Gyokuyou. Gyokuyou was glad that Hongniang, who was her chief lady-in-waiting and by rights should have been here, wasn’t present. Gyokuyou had asked her to take care of some other business. She felt a little guilty, but this was going to be easier without her.

Gyokuyou’s job was to smile. To never let that smile slip or fade.

That was her one weapon. Her father Gyokuen had found it and taught her to wield it.

Chapter 1: Return to the Western Capital

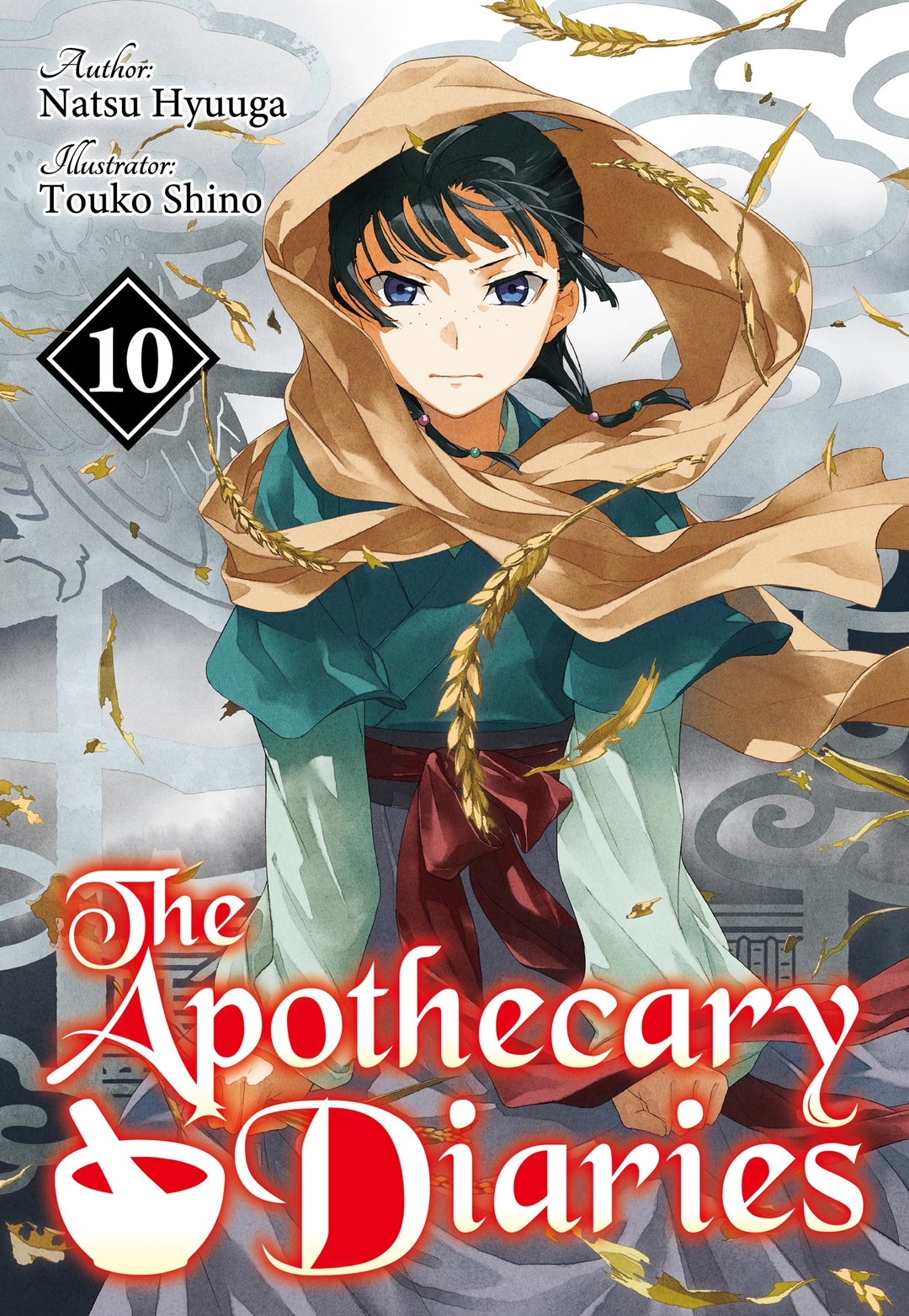

Maomao wiped her brow as she looked out of the carriage. The sun pounded down, baking the earth. The people who followed behind the vehicle on foot wore conical traveling hats, but it wouldn’t save them from the reflected light, which would still be strong enough to tan the skin.

So, a year later, and I’m back, Maomao thought. The last time she’d come, it had been a little earlier in the year, and not quite so hot. At least there was no humidity—the sweat she wiped at dried quickly—but it was still blazing.

The quack doctor had promptly succumbed to the heat and was curled up in a corner of the carriage.

“What this place needs is a little greenery! That would make things better,” Chue observed. She held out a leather pouch of water flavored with the rind of some sort of citrus fruit. Even the lukewarm drink was better than nothing on Maomao’s parched throat. “You’ve been here before, right, Miss Maomao?”

“Yes, last year.”

She certainly hadn’t expected to be back again this year. Most commoners never took a trip this long in their entire lives.

“But you weren’t here very long, right? Let Miss Chue show you around this time! You can see the sights! Enjoy yourself!” There was a gleam in her eyes. The less something had to do with work, the more eager she was to do it.

“No, thank you, I have a job to do.” Maomao would have loved to go sightseeing, to finally see the entire city and sample all the medicinal herbs and other plant life for sale at this nexus of trade. But there was one person she had to keep an eye on at all times. Jinshi.

That son of a...!

Even now, the memory made her blood boil, and she suspected it always would.

“Miss Maomao! Miss Maomao! You look tense,” Chue said and began massaging Maomao’s cheeks. It seemed like somehow, someone always ended up doing that.

“O-Oh, do I?”

“I’m sure they’d be perfectly happy for you to go out all day if you told them it was to inspect your surroundings. Just make sure you call me when you do!”

She just wants me to be her excuse!

Chue was easy to talk to, and better than any of the other potential minders who might be assigned to her, but still...

“Oh me, oh my! We’ve been talking so much that we’ve arrived!”

A town of stone and brick came into view. It was dotted with green trees, and a lake sparkled in the distance. Awnings fluttered here and there to keep off the sun. The carriage rolled right on, toward a great mansion. For a moment, Maomao thought they were going to the same house she’d been to last year, but then she realized it was the one next door to that.

“So this is the administrative office!” Chue said, looking at a stone plaque on the front of the building.

The carriage stopped at the gate. The other physicians were already waiting inside.

“Ah, is that everybody?” said the dark-skinned Dr. You, waving to them.

“Okay, Miss Maomao, Miss Chue has other things to do. So!”

“Right. Thank you very much.”

“Don’t mention it!” Chue pitter-pattered away, into the administrative building.

“Over here!” Dr. You called. He was standing with Tianyu and one of the other physicians. Maomao and the quack went over to him, with Lihaku following at an unobtrusive distance.

“Have you been here before, Dr. You?” Tianyu drawled.

“Yes, plenty of times. That was back before this was a bureaucratic office, though. I’m from the western capital myself, you know. A native son of I-sei Province. I know where the eastern villa is, more or less.”

“Huh!” said Tianyu, who didn’t sound very interested in the answer despite having asked the question.

Before it was an office, huh? Maomao thought. As they walked inside, she pondered what it might have been used for before. It did indeed feel more like a rich person’s house than a proper administrative building. Maybe it’s a mansion they confiscated from someone who wasn’t paying their taxes?

That was entirely her imagination, but it was enough to pass the time until they arrived at the villa. The medical supplies were already there.

“What should we do next?” the serious-looking physician asked Dr. You.

“Let’s see. The plan is for us to split into three groups, just like we did on the ships. The Moon Prince will be at Lord Gyoku-ou’s annex, Grand Commandant Kan will be here in the administrative office, and our man Lu from the Board of Rites will be in Lord Gyoku-ou’s main house.”

The good doctor seemed to refer to one of those men very differently from the others. Maybe they were close personally, or perhaps in rank?

“Should we split up into the same groups we did on the boats, then?” the other doctor asked.

“Hmm. I think something a little different today,” Dr. You said. He grabbed Tianyu and pushed him toward Maomao and the quack.

“Huh? I’m with them, sir?” Tianyu asked. “I was sure I would be with Dr. Li again.”

Maomao agreed. Li was evidently the remaining physician. The name was also extremely common—so much so that it was no help in telling people apart, and those surnamed Li often found themselves called by their full names. Lihaku was a handy example of that phenomenon.

“We tried to take all possible factors into account when we made that decision. You can be with Dr. Li—provided that you can mind your mouth. I heard about your little gaffes on the ship.” Evidently Tianyu had given lip to some high officials.

“But I might be just as rude anywhere else! Um... Where am I going?”

“To the annex. I’m going to be in the administrative office here, and Dr. Li will be at the main residence.”

“That would mean I’m in the same building as the Imperial younger brother, wouldn’t it? Wouldn’t that only have the potential to make things worse?”

That implied Maomao would also be in Jinshi’s building. She might have guessed as much.

“Hah! Hoping to get a chance to do an exam on the Moon Prince? Good luck. I doubt you’ll even see him much.” Dr. You smacked Tianyu on the shoulder. Tianyu rubbed it painfully.

Dr. You continued, “You’ll make the perfect group. Niangniang is good at mixing up medicines, which is precisely what you aren’t, Tianyu. But you’re the best surgeon among the new crop. This will be the perfect opportunity for you to learn from each other.”

That would be great, if Niangniang were here, Maomao thought, but she didn’t bother correcting him. She’d decided that if it didn’t actively harm her, she could live with it. She glanced at the quack doctor. He doesn’t even seem to be on the list. And he didn’t seem to realize it either.

“I only hope I can be a good teacher,” the quack said, fidgeting. Maomao looked away from him.

“Lookin’ forward to it, partner!” Tianyu said, slapping Maomao on the back.

“We are not partners.”

Maomao stood before the quack doctor, who flushed with embarrassment and hid behind her.

“I look forward to working with you, big guy!” Tianyu said.

“Y-Yes, it’ll be my pleasure,” the quack said. Tianyu evidently didn’t take him very seriously.

“You may be with a new group, but your job hasn’t changed. Doctors look after their patients—and nothing else! Each group will have a junior official assigned to it to act as a messenger in case anything comes up. Don’t hesitate to use them.”

It was nice working with Dr. You; he made things simple. Maomao knew the personnel on this trip had been selected for their ability to adapt to a rapidly changing situation, but he had a special ease that must have come from being on his home soil.

“You heard him. Shall we get going?” Tianyu asked, picking up his stuff.

Administrative office, main building, and annex: two of the three of them belonged to Gyoku-ou outright, which served to demonstrate how powerful he was. The office and the main house were right next to each other; the annex was a five-minute walk away. Each of them fronted the main street, but inside the administrative building the hubbub outside was hardly audible. It was just that big. The walls and the trees outside probably also helped block out the noise.

Maomao and her three companions were joined by the junior official who would serve as their messenger, the five of them shown to their building by a man who looked to be a local. As they stepped out the gate, they got a good view of the town.

Lihaku once again maintained a respectful distance, but Tianyu kept glancing back at him. I guess it does seem sort of odd, thought Maomao—a few ordinary physicians being given a bodyguard? To say nothing of the fact that the quack himself was personally in charge of Jinshi’s care. Tianyu was too sharp not to wonder why Maomao and the quack were being entrusted with the Imperial younger brother. She worried about when he might start asking questions, but for the time being she tried to act like everything was normal. She could at least play innocent until he specifically pressed her about it.

“My! Isn’t this exciting?” If the quack had still had his mustache, it would have been all a-quiver. He wasn’t a particularly brave eunuch, but at the moment his timidity seemed to be outweighed by his excitement at seeing the western capital.

Tianyu, too, was looking everywhere at once. His expression never changed, though, and he seemed less like he was having fun and more like he was taking careful stock of everything.

I’m never sure what to make of this guy. Maomao could never tell what he was thinking. She had figured out, though, that he was quick to latch on to anything that piqued his curiosity. If she knew what that was, she might be able to anticipate how he’d react—but she still didn’t know what he found interesting.

“Hm?” Tianyu said, tilting his head quizzically as they left the office. Maomao wondered what was up—and then she saw a familiar face. The owner of the face seemed to recognize them too, because he trotted over.

“It’s been much too long,” he said with a respectful bow of the head and a gentle smile. It was the pretty-boy, Rikuson. The freak strategist’s former aide.

That’s right. I heard he transferred to the western capital.

He was more tanned than the last time Maomao had seen him, no doubt from the strong sunlight in these parts. Two attendants walked behind him.

“It has, sir,” said Maomao.

“Yeah, haven’t seen you in a bit,” said Tianyu at almost the same time. Only the quack was left out of the loop. He looked at Maomao as if to ask who this person was.

“Do you two know each other?” Maomao asked, looking from Rikuson to Tianyu and back.

“Yes, in that I never forget someone I’ve met.” Rikuson smiled. Maomao sensed something tired in the expression. She also noticed that his clothes were dusty and there was mud all over his shoes.

“The first thing they told us when we started at court was to learn what the strategist’s aide looked like,” Tianyu said.

“Ahh. I see,” Maomao said. Tianyu might have greeted Rikuson familiarly, but he didn’t actually know or care that much about him. The quack, meanwhile, shifted uncomfortably, feeling shy around this stranger. For once, Maomao couldn’t just let everyone else do the talking.

“This is the master physician. I’ve come to the western capital to assist him,” she said.

“Master physician?” Rikuson asked with a puzzled look at the quack.

Oh! His name. His name is...uh...

Damn! She’d almost forgotten it again. She thought it was Gu... Guen? But she decided not to say it aloud. Instead she said, “If I tell you he’s the physician who served many years at the rear palace, would you know who I mean?”

Ah. Neatly done.

Rikuson clapped his hands. “Yes! This is him?”

That was a close one. I almost forgot.

The quack was a body double for her own father, Luomen, and he was being treated as if he were his more august counterpart. Rikuson, for his part, would surely be familiar with Luomen, who was the freak strategist’s uncle. He would probably also grasp that the quack was the only physician in the rear palace.

Never know if the walls might have eyes or ears.

They were still technically in Li, but the western capital was as good as foreign territory. More to the point, both of Rikuson’s attendants appeared to be locals—Maomao couldn’t afford to say anything careless. She would have to watch how she spoke.

Maomao didn’t have anything particular to talk about with Rikuson, and she was keen to get out of there before anyone gave the game away. “I’m sure you’re busy, Master Rikuson. I apologize for taking up your time,” she said.

“Not at all. I’m just now back from traveling for work. It took me quite a ways out, but I knew you all must be arriving soon, so I hurried back. I never expected my timing to be so perfect.” He smiled broadly, but it couldn’t hide the mud on the hem of his robe. It was dry now, but it was obvious that it had originally been quite dark, rich soil.

Was he out in the fields for some reason?

The western capital was a dry place; puddles were not a common sight on the roads here. Even if they had been, the dust would have been whiter, lacking in nutrients. The only place he could have picked up fertile earth like what was clinging to his outfit was in a field that had been watered. Maybe he was coming back from whatever village was closest to the water. Hurrying to get back, he hadn’t had time to worry about how he looked.

So nobody told him when exactly we were going to arrive? Lengthy trip or no, she would have expected Rikuson to know at least that much.

“I must be on my way. I’m afraid if I stand and chat for too long, my former boss might notice me. I’ll see you again,” said Rikuson. He looked like there was something more he would have wished to say, but he must have been too busy. Tianyu, who knew who he meant by his “former boss,” snickered. Only the quack doctor was left entirely in the dark, and he spent the entire conversation looking sad. Maomao would have to explain to him who Rikuson was while they were on their way to their destination.

She found herself with a lot to think about, but she also remembered what Dr. You had said to them.

Doctors look after their patients—and nothing else.

Maomao was an apothecary. So she would do an apothecary’s job—and nothing else.

Chapter 2: Boss and Former Boss

Rikuson heaved a sigh as he returned to his room, which at the moment was a chamber of the administrative building that he had appropriated as his living quarters.

“Is this purely about making my life hard?” he muttered, shucking off his sand- and mud-covered outfit.

It was quite a while ago that Rikuson had suggested a tour of the farming villages, but Gyoku-ou had only approved the idea a few days earlier. Rikuson had gone, but an unsettling premonition had brought him hurrying back—and now here he was.

“When I left for the villages, everyone told me they were going to arrive substantially later than expected.”

They being the visitors from the capital he had encountered moments ago. He had to admit, he’d never expected his former superior’s esteemed daughter to be among the entourage.

“Of course Master Lakan came,” Rikuson mused. Even the seasickening prospect of ship travel wouldn’t have deterred him from joining this trip. With all due respect to the esteemed daughter, Maomao, Rikuson found the idea faintly amusing. When he had been told that his former boss would arrive in about ten days, he’d set aside the five days before that for his trip to the farming villages. But then...

Rikuson brushed off his overrobe, getting sand everywhere. He would have loved to wash properly, but there was no time. There was hardly even a moment to wipe himself down. His only choice was to take an incense cake and daub some around his neck. In these parts, “incense” usually meant either perfume or a cake like this one, and Rikuson had only one of each on hand. One was a perfume that Gyoku-ou had given him as a joke, while the cake was one that he’d been hard-sold on while walking around town.

That was his choice of incense today. A cheap product like this was perfect—incense in the western capital tended to have strong fragrances, so something cheap that didn’t smell quite as much was ideal. He rubbed in just enough to mask the smell of sweat, and as a final touch he pasted a smile on his face.

A smile was essential for doing business, his mother had told him. Never let it slip in front of a customer.

Rikuson wondered what Gyoku-ou would think to see him back so much earlier than expected. Things could get a little awkward if his former boss was there, but so it went. He cinched his belt and left the room.

“It’s been some time, sir,” Rikuson said, forcing himself to act completely natural as he entered the hall. Gyoku-ou and his subordinates were there, along with the guests, enjoying a light meal. Servants bustled in and out with the food. It was too early for dinner, but the offerings looked sumptuous all the same.

Rikuson recognized all the guests—naturally. He wouldn’t forget them. The stubbly man with the monocle was Lakan. His former superior; he would know him anywhere. Beside Lakan sat his aide, Onsou. He had been around since before Rikuson had served Lakan; when Rikuson had taken over, he distinctly remembered Onsou coming to him with tears of gratitude in his eyes.

Onsou was a capable man, but he had an unfortunate tendency to draw life’s short straws—a tendency to which he might as well have resigned himself the moment he found his way into Lakan’s orbit.

Onsou saw Rikuson come in; he gave a slight bow and whispered to Lakan. Lakan looked at Rikuson with the same vacant expression he always wore. If Onsou hadn’t said something, he would probably never have realized Rikuson was there. Rikuson was sometimes curious exactly what he looked like to the strategist.

Lakan beckoned Rikuson over, but he wasn’t sure if he should approach the strategist out of the blue. He looked to Gyoku-ou. The interim ruler of the western capital waved at him from his place of honor at the table to go pay his respects.

Rikuson felt very awkward indeed. Onsou was looking at him with an expression that was hard to describe—he seemed to be wondering whose side Rikuson was on. Between his current boss and his former boss, Onsou ought to have understood to whom Rikuson’s present position made him beholden.

Lakan, meanwhile, munched on some fried food, seemingly indifferent to the situation. The food first passed through the hands of a lady-in-waiting Rikuson didn’t recognize, who left only the merest scraps for Lakan’s consumption. Rikuson might have assumed she was his food taster, but if so, she was keeping most of the meal for herself. Lakan simply got her leftovers.

He’d heard the Imperial younger brother would be coming to the city, but at the moment he didn’t see him. This didn’t seem to be a public banquet; Lakan had probably accepted the invitation without thinking anything of it, but Onsou’s brimming eyes made it clear that he was supposed to have politely refused.

“Ahem, ah...Rikuson, I want to eat that one bun,” Lakan said. At first Rikuson had been sure Lakan had forgotten his name, but it turned out that wasn’t true. As for “that one bun,” he added, “Onsou says he doesn’t know which bun I mean, but I told him! That bun!”

Rikuson agreed with Onsou: that wasn’t enough to go on. Was that why Lakan had called him over? Because he wanted a snack bun?

Rikuson searched his memory. “You’re talking about something sweet, yes, sir?”

“Of course I am.”

“Does it have any filling?”

“I don’t think so.”

So it wasn’t a red bean filling that made this bun sweet.

“Is it covered in sauce, or do you dip it in anything?”

“Ah, the sauce! Yes, there was a sauce! That white stuff—I love it!”

Rikuson finally connected the dots. “Master Lakan. Are you talking about the fried buns from the Liuliu Fandian?” The name meant “The Double Six Restaurant”; it was a place Lakan had gone once, and several times after that, he’d sent Rikuson to buy the buns.

“Sir Onsou. Fry up a mandarin roll, then top it with sweetened condensed milk,” he said.

“I’m on it.”

There was a mandarin roll already in front of Lakan; that must have been what put him in mind of the Liuliu’s creation.

“Fried bread with condensed milk? Sounds tasty!” said the woman who appeared to be Lakan’s food taster, her eyes sparkling. She didn’t seem much like your ordinary lady-in-waiting—another of Lakan’s “finds,” perhaps.

“Miss Chue, perhaps you’d be so kind as to taste slightly less of the food for poison,” Onsou said. So her name was Chue. Onsou’s touch of deference suggested she wasn’t Lakan’s lady-in-waiting so much as someone who had been borrowed from elsewhere to fill this role.

“Oops! My bad,” Chue said.

If nothing else, this conversation proved to Rikuson that Lakan was still Lakan.

“I can have the rolls prepared for your snack tomorrow, sir,” Onsou said.

“I want them for dinner tonight!”

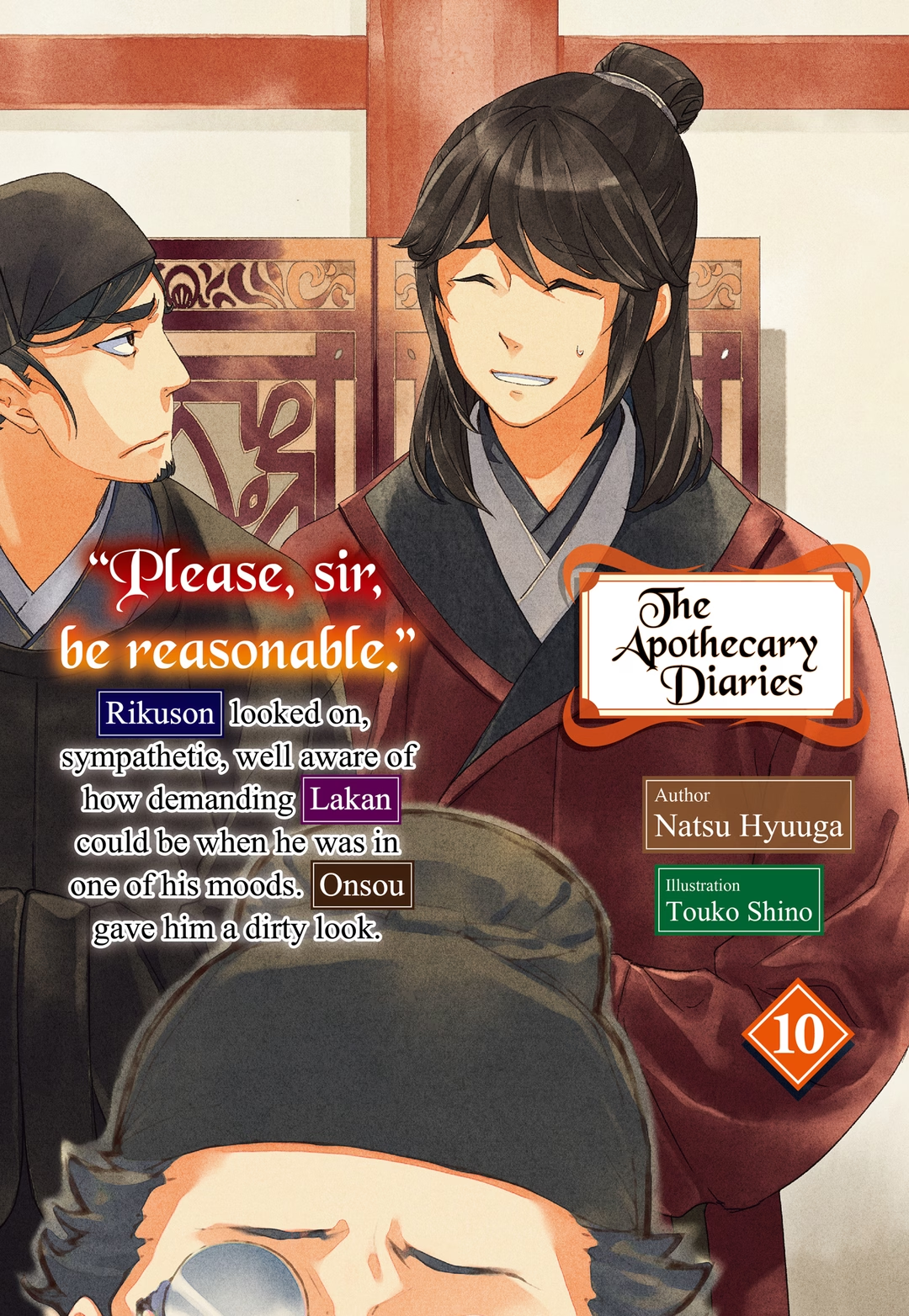

“Please, sir, be reasonable. We’re already at a banquet!” Onsou’s voice came out in a squeak; he didn’t seem able to muster much more. Rikuson looked on, sympathetic, well aware of how demanding Lakan could be when he was in one of his moods. Onsou gave the former aide a dirty look.

“I see some things never change,” Rikuson said to Onsou in an effort to repair his mood.

“Indeed they don’t. And you seem to have made yourself quite at home here in the west.” Onsou had noticed Rikuson’s suntan and smelled the incense wafting from him. He’d never been the kind to wear incense back in the capital. He only did it here to cover the smell of sweat, but he refrained from saying so; he thought it would sound like an excuse.

“You’ll have to pardon Rikuson. He’s only just gotten back from quite a long trip,” said Gyoku-ou as he took a bite of meat. Evidently he had been listening to their conversation.

“O-Oh, I see,” Onsou said, paling to be so suddenly addressed by Gyoku-ou himself. No doubt he hadn’t expected the great man’s conversation to turn to him.

“Is the food to your liking? If there’s anything you want, I can have my chef prepare it immediately.”

“You know the fried dough at the Liuliu Fandian?” Lakan, never one to need asking twice, broke in. The people of the western capital would not, of course, know the fried bread of the royal city.

“Hoh. Please, tell me about it,” Gyoku-ou said. Now that he had expressed a willingness to listen, it would be Rikuson’s job to explain. He felt butterflies flutter in his stomach. This seemed likely to be his lot for the foreseeable future—not a happy prospect for the ever-anxious Rikuson.

Chapter 3: The Annex and the Forgotten Man

Gyoku-ou’s annex seemed like quite a comfortable place to be thanks to its abundance of greenery. When one thought of I-sei Province, where the western capital was located, one thought of the desert, but in fact there were many grassy plains. It was dry, yes, but there was more here than sand; there was enough water for herbaceous plants, at least, to grow. Which was not to say that water wasn’t precious here.

Was that the main house we stayed in last time? Maomao wondered. There had been lots of green there too. Just having all those trees in the mansion’s garden was enough to provide the impression of wealth. Of course, to the people of the capital—who were used to living by the great river, with the sea not so far away—it might have lacked a certain something.

But it’s enough to be refreshing.

The garden here was done roughly in the style of the central region, but it was full of plants she had never seen before. Her first thought was that she would love to test their medicinal effects—but, well, that was Maomao for you.

“Young lady! Let’s set our luggage down first. It’s been such a long trip, and I’m so very tired,” the quack said, looking as run-down as he sounded.

“Good idea,” said Tianyu. “Hey, Niangniang, once we get to our room, maybe we can play rock-paper-scissors to see who gets to explore the mansion.”

Lihaku walked a few paces behind the three of them, keeping watch. The medical office was in a separate building from the mansion. They couldn’t exactly complain about the location; sickness was considered an impurity, after all. If the office was anywhere too well traveled, they would only have to worry about infection every time a patient showed up, anyway.

“This is one odd place,” the quack said, looking at their building, mystified. “I thought the same thing at the administrative building’s medical office...” It certainly wasn’t what they were used to in Li, and while the western capital had its own architectural style, the building didn’t really seem to belong to that either. It almost looked like...

“Is this a chapel?” Tianyu asked, his hand brushing the bricks.

“Chapel? What’s that?” the quack asked. No wonder he didn’t know the word; there weren’t many chapels in Li, and the quack was hardly what you would call cosmopolitan.

“Think of it like a shrine,” Maomao offered.

“Oh! A place to pray.”

“Yeah. There’s a lot of different religions in this city,” Tianyu said.

They entered the building to find a high-vaulted room. There didn’t appear to be any objects of worship inside; the only vestiges of any faith once practiced here were some decorations on the walls. Maybe some pious person had once lived here. When the place had passed into Gyoku-ou’s hands, he had stopped short of tearing it down, but it was no longer a place of worship.

“It’s the perfect size. Oh, and look! The rest of our belongings have already arrived. Hmm, there really is quite a lot. It’s going to be a job organizing everything. Suppose we just leave them in the boxes?” the quack said.

“Good point. Let’s hurry up and rock-paper-scissors it! Who gets to go exploring?”

Not long ago, Maomao would have eagerly accepted Tianyu’s suggestion. Careful thought, though, left her with a question: Even if she won the game, would the other two actually do their work here? At the same time, she knew she would be annoyed if Tianyu won—and if the quack doctor earned the chance to go exploring, well, that thought was a little nerve-racking too.

In the end, Maomao took the most boring solution. She rolled up her sleeves, tied a handkerchief over her mouth, and said, “Right, exploring comes later! First we need to get this stuff sorted!”

“Aw. You seemed all excited to look around earlier.”

“I’m so very tired from our trip, young lady. Can’t we take things slower?”

“No, we can’t!” Maomao said, rebuffing them both. Their medical supplies could have rotted during the long sea voyage; they needed to know what was still usable and what wasn’t so that they could stock up on anything they needed. “No one leaves this room until we get all of this organized.”

“Oh no...” The quack stuck out his lower lip and looked deeply dejected.

Tianyu didn’t look happy about it, but he shuffled over to the supplies and started working.

“What would you like me to do, young lady?” asked the big mutt, Lihaku. He looked like he might just drop to the floor and start doing push-ups to pass the time if she didn’t have anything for him to do, so she decided to put him to physical labor.

“Could you get the box by the door and bring it here?” Maomao asked.

“Sure thing! Oof! This is heavy!” It turned out to be a bit much even for Lihaku.

Maomao went over to the box, opened the lid, and peeked in. It was packed with rice husks and sweet potatoes. No wonder it was so heavy. Even Lihaku wouldn’t be able to lift it by himself.

“I don’t think this is ours,” she said.

“What do you think? Should we borrow a cart and haul this somewhere?” Lihaku asked.

“No, I think we can just let someone in charge know and they can deal with it,” Maomao replied, pondering whom they should tell.

At just that moment, someone came from the direction of the garden, waving urgently. “Heeey! I think some of my cargo got mixed in with yours,” the newcomer called. He was a man with no particular distinguishing characteristics—the only thing notable about him was how unnotable he was. He had unobjectionable looks and was probably twenty-three or twenty-four years old.

I feel like I’ve seen him somewhere before, Maomao thought, pondering further.

When the newcomer saw Maomao, he stopped short. “It—It’s you!” he said, pointing dramatically at her. “The one who might be Lahan’s sister or might not, I can’t tell!”

“The answer is not.” Now she was sure: she’d had this conversation before. But who is this guy? Her eyes drifted to the box full of sweet potatoes. The mention of Lahan’s name sparked a memory. “You’re Lahan’s Brother, aren’t you?” Her memory of him was hazy, but she thought that was who he was.

“Lahan is younger than me! Why should I have to be defined in terms of him?!”

Yes, this was Lahan’s Brother, with his delectable reactions. She had met him before, and remembered him mostly for being very normal and offering copious chances for witty interjections. His face, though—that she had completely forgotten.

“Well, I don’t know your name,” she pointed out.

“My name is—”

“That wasn’t an invitation.” She’d only just recently, and finally, remembered the quack doctor’s name. She didn’t need any more to learn.

“Listen to me! Let me tell you my name!”

Maomao, however, was in no mood to listen. “More importantly: What are you doing here?” This guy normally spent all his time tending potato fields in the central region.

Lahan’s Brother looked scandalized by Maomao’s question. Lihaku, having decided that he wasn’t a threat, looked on quietly.

“I’m here because they dragged me here! They brought me instead of my father, with orders to teach the people of the western capital how to grow these things!” Maomao sensed some resentment. “These things” referred to the sweet potatoes.

“I take it Lahan duped you into doing this.”

“H-H-He did not!”

Lahan’s Brother was nothing if not easy to read. And Lahan remained his usual ruthless self.

“Why didn’t he ask his father?” Maomao asked. Lahan’s Father, La...uh, something or other, loved farming and seemed like he would go to the ends of the earth if there was a field to be tended there.

Lahan’s Brother paused. “After his experiment with growing sweet potatoes in the north came to light, he can’t get away.”

“Experiment?”

“Sweet potatoes yield several times more than a rice crop, so he thought they would be perfect for Shihoku Province, where there’s plenty of people and space.”

“Right.”

Jinshi had been trying everything he could to shore up the food supply, and she seemed to recall Lahan being very bullish on potatoes as well.

“The problem is, sweet potatoes come from the south, so they don’t grow well in the north. In fact, I doubt they’ll grow at all, but Dad says it’s worth trying to figure out what the northern limit is, so I just let him do that.”

“I’m not sure this is the time...” Even Maomao could tell that this was a dangerous idea. A famine was looming; they couldn’t spare people and land to satisfy one farmer’s curiosity.

And he had such a pleasant look...

The man had reminded her of Luomen, and evidently when something interested him, he became completely absorbed in it to the exclusion of everything else.

“It would be too risky for all the fields to be sweet potatoes, so I brought these too. Have a look.” Lahan’s Brother tossed her something from the box next to the crate of sweet potatoes.

“Regular potatoes? This is a white potato, right?”

It was a big, stout, round potato. Potatoes were a relatively new foodstuff; the matron of the Verdigris House had told Maomao that they weren’t yet widely eaten when she was young.

“That’s right. A tuber like this can grow even in the cold, even if the ground isn’t very fertile, so he made me bring these along. Lahan only knows Nice Dad, but he can be a pretty formidable character when he wants to.”

Lahan’s Father, La-something-or-other by name, was evidently a bona fide member of the La clan. Even Maomao had nearly been taken in by his pleasant countenance.

“Potatoes can be harvested twice a year, so my father has been hell-bent on planting them. I’m afraid he might be trying to use them to fudge his harvest numbers.”

“You seem to know a lot about potatoes,” Maomao observed. She’d taken Lahan’s Brother to be a completely average person with no special qualities other than his vulnerability to a good quip, but it turned out he did have something to offer.

“Wow, you’re a regular farmer!” Lihaku said, clapping Lahan’s Brother on the back. He hadn’t followed the entire conversation, but he was impressed just the same.

“F-Farmer?!” Lahan’s Brother choked. He seemed to want to push back, but he was too enraged to say anything more. The quack doctor, apparently intimidated by Lahan’s Brother’s fury, kept his distance. Tianyu seemed to judge the man simply too normal to be interesting.

“So your point is, these potatoes aren’t food, they’re seed crops?” Maomao said.

“Yes, they are! I’m supposed to show the people how to raise them. Him and his My older brother can’t spend his whole life tied to one place! How is one field so different from another, anyway?!”

In short, this normal person had demonstrated a normal interest in the outside world and been duped for it. The fact that he had chased down this crate of seed potatoes, though, showed that he was indeed a dedicated farmer. Maomao suspected he would produce a lovely crop, even if he complained the whole time.

Teaching them to grow new crops, huh? That presumably meant Lahan’s Brother would be spending his time out in the farming villages.

“When you go out to the villages, take me with you,” Maomao said.

“Why would I do that?”

“There’s something I want to investigate.”

This was a gift from above. She’d assumed she would have to ask Rikuson or someone—until Lahan’s Brother had come along.

I saw Rikuson’s outfit. The mud-streaked clothes suggested he’d been inspecting a farm somewhere. But what was a man sent all the way from the capital doing relegated to the fringes of his new home?

Maybe he was checking the harvests to make sure no one’s cheating on their taxes. Or maybe... Maybe he knows about the insect plague.

A plague of insects had struck west of the royal capital, which meant there was a good chance the locusts had come from farther west than that. It would always be easier to deal with a swarm of locusts when there weren’t as many of them.

I’m not all that interested in bugs, but I don’t think I can get out of this one.

For a second, Maomao found herself thinking of another young woman, one who had liked insects far more than she did.

“Of course, I’m trusting myself to your services today, Master Physician. As ever.” Jinshi smiled as he received them. They were in the most sumptuous guest room in the annex. There was a rich, thick, delicately embroidered sheep’s wool rug, and the curtains appeared to be made of silk; they shimmered and shone each time the wind ruffled them. Maomao could never help wondering about the market value of Jinshi’s accommodations.

That looks good, though, she thought, spying a plate of fruit on the table. There were luscious grapes, so recently chilled that they were still sweating. They promised sweet juice filling the mouth as they burst between the teeth.

I wonder if he needs them checked for poison.

Sadly, Maomao wasn’t there at that moment to taste Jinshi’s food. That job fell to Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting Taomei. The boisterous Chue was missing today, and Maomao didn’t see Baryou either, although she had her suspicions about what was on the other side of the gently rustling curtains. Suiren and Gaoshun stood by the wall.

The quack doctor remained cowed in Jinshi’s presence. “Eep! L-Let’s get started, then...” As usual, he could barely get the words out, and as usual, his exam was pro forma at best.

Tianyu was also absent from this scene. He’d proved too likely to offend someone important to be invited on a visit like this. Tianyu was perceptive enough that he might have looked askance at Maomao and the quack going to do this exam, but if he had any doubts, he had kept them to himself for the moment. Was that because he knew how to take a hint, or had someone on Jinshi’s side of things reached out to help him understand? Maomao preferred not to think about it.

I also don’t care either way. She had things to do. For now, she would put aside the question of why Jinshi had been consigned to the villa. The freak strategist wasn’t in the same building; that was what really mattered.

“All right, young lady, I’ll be heading back,” the quack said.

“Yes, sir,” Maomao replied.

The quack left without so much as a scruple. His bodyguard, Lihaku, went with him.

Jinshi turned down the sparkle just a bit. “Tea, if you would,” he said.

“Of course, sir,” replied Taomei, and went to prepare it.

“Here you go.” Suiren thoughtfully brought a chair, so Maomao sat down. She wasn’t rude enough to grab any grapes just then, but she tried to send Suiren a telepathic message that she’d like some as a souvenir.

“How are you settling into your new workplace?” Jinshi asked.

“Easily enough, sir. The personnel haven’t changed, so it’s just getting used to the new environment.” That was the honest answer. What she really wanted now was to find out what kinds of medicine were available in the western capital. When they’d taken stock of what had been used during the ship voyage, it turned out to be chiefly nausea medication and antipyretics. The southern route they’d taken had been as hot as high summer, and combined with the poor air circulation on the ship, they’d had lots of cases of dizziness. Heatstroke was best cured by water, not medicine, but Maomao suspected that while she was away, the quack had diagnosed many of the cases as colds and handed out antipyretics. That would explain it.

Funny enough, it had worked out: the medicine the quack had prescribed tasted so bad that patients had to take it with plenty of water anyway, so in the end it had cured their heatstroke.

He’s sure got luck on his side, she marveled. Even better, she’d heard that they would be given new supplies bought in the western capital to make up the shortfall in their inventory. Wish I could have gone along on the shopping trip, though. She was so curious about exactly what drugs were sold here.

Maomao, however, had other things to attend to. She glanced around, then stole a look at Jinshi’s side. She wasn’t sure how to bring that up, so she settled on changing the subject entirely.

“I gather we have a potato farmer among us, thanks to Lahan’s connections.”

This was Lahan they were talking about; if they succeeded in cultivating potatoes in I-sei Province, she was sure he intended to go straight into exporting them to Shaoh or something. It was right next door to I-sei, which would minimize shipping costs.

Jinshi gave her a look. “A potato farmer? He’s your cousin, is what I heard.”

“No relation,” she said firmly, so that there would be no mistake.

“But I heard he was Lahan’s older brother.”

“Yes, but Lahan and I are complete strangers.”

Jinshi gave her a harder look, but he went along with it.

“Anyway, yes, we do have a potato farmer here. When I heard he was from the La clan, I expected someone... I don’t know. More distinctive.”

“Have you met him, sir?”

“I’ve only seen him in passing. I saw him when Lahan was helping him onto the ship.”

In other words, he had spotted them smack in the middle of the dupe.

“He’s a very normal person, sir.”

“Yes. Very normal.” It seemed Jinshi shared Maomao’s assessment—but anyway, if he already knew about him, that made everything easier.

“I’d like to accompany him to the farming villages. Do you think I could be given permission?”

“The farming villages? It would help me if you could go, but then how would you handle your medical duties?” Jinshi patted his flank pointedly.

You did that to yourself, Maomao thought. He already knew how to change the dressings, anyway, so she didn’t have to be examining it all the time.

“A young man named Tianyu has been assigned to our group. I think he could manage things, sir,” she said, ignoring Jinshi’s injury for the moment. She might object to Tianyu as a person, but his actual work seemed trustworthy.

“Hmm... Very well,” Jinshi sounded like he had to swallow some objection, but agreed nonetheless. “I was already planning to have someone get a firsthand look at the farms. There are enough issues with the villages vis-à-vis the impending plague. This might be perfect.”

“What kind of issues?” Maomao cocked her head. Jinshi had so many different problems to deal with, she didn’t even know which one he meant.

Jinshi looked to Gaoshun, and the other man unrolled a map of I-sei Province on the table. It bore several circles in ink.

“What are these?” Maomao asked.

“The locations of the farming villages.”

“There aren’t as many as I expected, considering I-sei Province’s size.”

“There’s a fair number of individual plots of farmland, but some sort of problem crops up when they reach a certain size. Outside of the western capital itself, the population here has never been very large, and with all the trade that goes on, many people simply import their food.”

In this land, withered soil was the norm and water sources were limited. Maomao might only be able to go out to the nearest village.

Is that the same place Rikuson went?

He’d looked very busy—she doubted he’d been visiting the farms just to pass the time. He must’ve gone to the closest place.

“And these,” Jinshi said, taking a brush Gaoshun offered him and drawing a larger circle on the map, “are grazing lands.”

“Grazing lands, sir?” In other words, a place where livestock could feed. Probably not cows here in the western capital—goats and sheep, more likely.

“Some of them are used by the farmers, but some of them are areas that nomadic tribes pass through. Groups that don’t have permanent settlements.”

“I see.”

Jinshi didn’t seem to be explaining for Maomao’s sake so much as he was trying to organize his own thoughts. “Do you remember the orders I issued to try to combat the grasshoppers?” he asked.

“I do. You forbade the killing of pest birds, promoted the eating of insects, and said the farming villages should be taught how to make insecticide.” Maomao had been involved in the insecticide project herself. She’d developed several formulas that used primarily local ingredients.

“Right. Those orders went out all over Li, including I-sei Province, of course. However...” He trailed off.

Maomao thought she could see the miscalculation Jinshi had been confronted with. “Even if farmers do use insecticide, they only use it on their fields,” she said.

“Exactly.”

And I-sei Province had a few small fields and a lot of very big plains. The farmers wouldn’t kill the bugs in the grassy areas. Not to mention that there was every chance the nomads had never received the orders at all.

Even if they had... They wouldn’t want to put farm chemicals all over something their livestock were going to eat, and they wouldn’t go around killing grasshoppers one by one either.

Jinshi and Maomao were both silent.

The grasshoppers that had avoided extermination would produce a new generation many times larger than their own.

Maomao, though, was puzzled. “Pardon me, sir, but wasn’t there already a small-scale insect plague in western Li last year? Did that include the western capital?”

“No report of any plague came from I-sei Province,” Jinshi said, sounding equally perplexed. “Admittedly, this area survives largely by trade and doesn’t do much planting of its own, so any agricultural damage would be modest...”

“But there should have been some.”

She thought back to the previous autumn. Jinshi had sent her a crate of grasshoppers—it almost qualified as harassment—and she had measured hundreds of them. At the time, Lahan had speculated that they might have come from Hokuaren on the seasonal winds. And which area was closest to Hokuaren? I-sei Province.

Could the grasshoppers have missed them by pure luck? Or...are these people hiding something?

Maomao searched Jinshi’s face. He didn’t look overly concerned, but seemed calm, like he was simply confirming something he already knew. Information he already had. She tried to look at the others in the room for a hint, but Suiren, Taomei, and Gaoshun betrayed nothing.

Is I-sei Province trying to hide a bad harvest? she wondered. Then she groaned to herself. Maybe it’s Empress Gyokuyou’s brother.

Gyoku-ou, the man who was now in charge in the western capital on behalf of their father. He seemed to have some sort of history with Empress Gyokuyou, but Maomao had largely ignored it as something that didn’t involve a simple apothecary.

Did all this have something to do with why Rikuson had been out in the village, getting himself filthy?

Maomao started to feel impatient, restless. Thinking about the question only left her tying herself in knots, but she hated the feeling of leaving it unanswered. Best to move quickly, then.

“I know it’s somewhat sudden, but perhaps you’d allow me to leave for the farming villages tomorrow, sir?”

“Much as I’d like you to get underway as soon as possible, that might be a bit too soon,” Jinshi said. “Hmm...”

Gaoshun intervened at that moment. “Moon Prince,” he said.

“What is it, Gaoshun?”

“If Xiaomao is to leave, best she wait a few days first.”

“Why? So everything can be gotten ready?”

“No, sir. Because Basen should arrive a few days from now.”

Maomao felt like she hadn’t heard that name in a long time. Basen, she remembered, was traveling overland to reach the western capital.

“I think he would make an ideal bodyguard for Xiaomao,” Gaoshun said.

“All right. We’ll use that time to prepare,” replied Jinshi, and with that, it was settled. Maomao let out a sigh of relief and was about to head back to the medical office where the quack and Tianyu waited, but Jinshi spoke again. “Just a moment.”

“Yes, sir?”

“My stomach is bothering me. Perhaps you could examine it?” He grinned at her.

I might have known.

“I’ll be waiting in the next room,” he said. Then he left and, perhaps informed ahead of time, Suiren and the others stayed behind.

“Very well,” Maomao said after a moment. She took out fresh bandages. Privately, though, she wished Basen would hurry up and get here.

Chapter 4: Spring Comes to Basen (Part 1)

“Quack, quack!” said a voice.

Basen looked at the yellow-beaked, moist-eyed, fluffy-feathered white duck in front of him.

“I guess this is goodbye, duck.”

Basen had received several secret orders from the Moon Prince over the past several months. One of them concerned the likes of this domestic white duck. It was a classic bit of livestock: easy to raise, and it frequently laid eggs.

In fact, raising ducks had been the mission in question.

At first, Basen had thought the Moon Prince must be making fun of him. For all the flaws he might have, he hailed from a clan that had historically been charged with guarding the Imperial family—and now he was supposed to look after some waterfowl? He began to wonder if the Moon Prince had abandoned him.

Such, however, was not the case.

“The raising of livestock will save this country from much unhappiness, and I’m confident that you will pursue the duty diligently,” Basen had been told. If the Moon Prince was willing to give him such a vote of confidence, he could hardly decline. This had been near the end of last year.

Once he knew what his mission would be, he knew that the first thing he had to do was seek the advice of someone who knew more about raising ducks than he did.

Thus, early in the year, he’d found himself spending a great deal of time visiting one particular place...

To the northwest of the capital was a place called Red Plum Village. It was a haven for those who had left their homes and families in hope of becoming wayfarers. Wayfarers: usually that word evoked images of monks undergoing harsh training, but here things were a little different. Many here seemed to sincerely believe that their practice could make them true immortals.

Raising animals was one facet of their practice. When Basen had first heard of it, he’d doubted his ears. “I thought monks and nuns were all vegetarians,” he said.

“Immortals are long-lived unto endless life. A person can’t live on vegetables alone” was the prompt and nonchalant answer. The place was run by an old man, as Basen had heard, and if you ignored the fact that his clothes were dirty and covered in feathers, you could see that in fact he had healthy skin and stood very straight. His life might or might not prove to be endless, but he was clearly experienced in how to be long-lived.

The old Basen might have argued the point, but he liked to think he had learned a thing or two over the past several years. He decided to consider the old man to be in the same category as that eccentric apothecary and left it at that.

It turned out he had the right idea. Training wayfarers was a pretense for Red Plum Village; in reality, it was a group of researchers. Much of their practice contravened the precepts normally observed by monks and nuns, but the research was so valuable that everyone above them seemed to turn a blind eye.

“Ducks can lay up to 150 eggs a year. They’re omnivores, so they’ll eat anything, and they can start laying eggs as early as six months after hatching. They’re not so dissimilar to chickens, but if you intend to feed them grasshoppers, you’d be better off with ducks, I think—they’re physically larger. If you feed them one single type of food from infancy, they’ll come to eat that food exclusively, but that carries the risk of adversely impacting their growth, so I don’t recommend it. The only possible problem with ducks is that they don’t incubate their eggs as readily as chickens do, so...”

Basen wondered why people researching a particular field were always such windbags. Even that apothecary, Maomao, could be quite the talker when she warmed to her subject, and the bureaucrat Lahan was the same way.

Red Plum Village sprawled across a substantial area, much of which was devoted to agricultural fields. None of the “wayfarers” here wore the attire of religionists; they were all dressed to work outdoors. Their breath fogged as they worked in the fields.

“...and so as you can see, I’m terribly busy with my research, so I’m afraid I can’t entertain your request,” the old man said, finally winding down to the end of his speech.

“I’m sorry. I don’t quite follow,” Basen said.

“I’m saying that I cannot teach you, but my disciple, whom I currently entrust with the work, can. You’ll find her in that shed. Farewell.”

“H-Hey, wait!”

The old man scampered away with a quickness that belied his age. Left with no choice, Basen went toward the shed, which was periodically emitting steam. “Excuse me?” he said. “I’d like to learn about duck-keeping...” The door barely seemed to be hanging on, and when he opened it, fetid air hit him in the face.

“Y-Yes, of course. Laoshi told me,” came a nervous voice. Basen could see a small figure in the haze.

“I-It’s you!” Basen exclaimed. The small figure was a young, plainly dressed woman. The fabric of her outfit wasn’t even dyed, let alone embroidered, and her hair, held back with a simple piece of string, had no hair sticks or ornaments. Yet, even without a spot of rouge or whitening powder, she looked so much more full of life than she had the last time he had seen her. “Consort Lishu?”

“I... I’m not a consort anymore, M-Master Basen.”

Standing before him was an ephemeral princess. A member of the U clan, who had twice entered the rear palace as consort of an emperor.

“What are you doing here?” Basen asked. He immediately wished he could have said something more thoughtful. His sister Maamei would have given him a piece of her mind if she knew.

Lishu had once been an upper consort, but she had been banished from the rear palace. True, she had been manipulated by the woman people called the White Lady, but that didn’t change the fact that she had caused quite a commotion at court. Lishu had been obliged to retire from the world.

No one had told Basen so much as where she had gone or what she was doing; the Emperor said only that if he wished to see her, he should focus on doing great deeds. At a loss, Basen had recently made donations in cash and kind to several temples in hopes of making himself feel a little better—they hadn’t even told him which temple she might have been hiding at.

He was so flabbergasted by this unexpected reunion that he could hardly think.

“W-Well, as you know, I was banished from the rear palace. I couldn’t go back to my family, or to my last temple. His Majesty intervened on my behalf so that I could come here to Red Plum Village,” she said.

“Yes, but... Of all the places...”

Lishu’s outfit was filthy in spots, smeared not just with mud but animal dung. Worst of all, there was no one in this shed but Basen and Lishu, and Basen agonized over whether it was appropriate for him to be alone with a young lady.

“Have you no attendants? What happened to that lady-in-waiting who used to serve you?” Basen asked, shaken to see Lishu’s reduced circumstances—almost as shaken as he was to have Lishu right here in front of him.

“You mean Kanan? I released her from my service. She has her entire future ahead of her; she shouldn’t waste it here with me. I asked His Majesty to arrange a good match for her.” Lishu smiled and glanced down, her long eyelashes fluttering.

Basen clenched his fist. “Then you... You’re here alone?”

“You mustn’t worry. I have an old lady to look after me.”

“Just one?”

“Yes. I have no more need for heavy outfits or elaborate hair ornaments, after all.”

To Basen, Lishu’s words carried an air of self-recrimination—and yet, her expression was as clear as a cloudless sky. Basen had never been the best at guessing what a woman might have been thinking, and right now he had no idea what to say or do. Lishu was as retiring and as charming as ever, and appeared to be hard at work despite circumstances far beneath her station. Her slim fingers were caked with mud.

“This is no place for someone like you, Lady Lishu. I’ll talk to them, convince them to give you better work!” Basen said. It was the most helpful thing he could think of.

Lishu, however, shook her head. “N-No, thank you. I’m grateful for the thought, b-but these circumstances...”

“Yes? What about them?” Basen’s question was all but interrupted by quacking. He turned to find himself confronting several dozen ducks. “Gwuh?!”

The birds surrounded Basen, peering at him with their heads cocked in puzzlement. He couldn’t shake the sense that they were taking stock of him.

Then the ducks waddled over to Lishu, nuzzling up to her. She patted their wings. “A-At first, I was sure I couldn’t possibly raise ducks,” she told him. “But I’ve looked after these sweethearts since they hatched, and they think of me as their mother. Laoshi t-told me that’s just the way ducks are...”

When he heard the words ducks, hatched, and Laoshi, he finally realized Lishu was the disciple the old man had been talking about!

“Lady Lishu... You mean, you...?”

“Yes. I was told to teach you about hatching ducks.” Her stutter had vanished; perhaps she was more comfortable surrounded by the animals. “Ahem... Master Basen?” she said.

“Y-Yes? What is it?” he asked, unconsciously straightening up as if addressing one of his superiors.

Lishu glanced at him, then picked up a handful of her skirt. “I kn-know it’s a little late to be asking this, but how are your injuries?”

Basen had completely forgotten that the last time Lishu had seen him, he’d been one big pile of cuts, bruises, and broken bones.

“Oh, I’m used to getting a little injured. You don’t have to worry about me,” he said. Privately, he was overjoyed that she was concerned about him (even if that concern was only natural), but he was also a bit embarrassed. He realized Lishu had never exactly seen him at his best.

“But you suffered all that for my sake... And I never even got to thank you...”

“Lady Lishu...” Basen felt strange, simultaneously relaxed and anxious to be with this young woman. He shook his head: no, this wouldn’t do! He had business to attend to. “Well, Lady Lishu. If you would be so kind as to instruct me.”

“Y-Yes, of course,” she said, but she sounded almost disappointed.

There was a story passed down which related that long ago, when there had been a plague of locusts, the ducks had combated it by eating all the bugs. It was a legend, of course, not a serious model for policy, but at the same time, legends often contain a seed of truth. Ducks did eat insects. As omnivores, they frequently ate humans’ leftover food, but during plagues of locusts they could eat those too. A few even preferred eating bugs and sought them out.

Besides, having more livestock could only benefit the farmers. Therefore it had been decided that ducks would be distributed to the farming villages—but therein lay a problem.

How would they get these ducks that they were going to give out? Ducks were living things; one didn’t just snap one’s fingers and make more of them.

“Here, like this. The eggs should always be kept slightly warmer than human body temperature. You can’t just leave them lying there either; you have to turn them once in a while.” Lishu gently turned one of the eggs over in demonstration. It sat on a bed of straw, underneath which was soil as soft as mulch. “The eggs won’t hatch if they get too hot or too cold, so Laoshi told me I should learn the temperature by touch alone.”

“By touch alone?”

“Y-Yes. Also, they need some humidity.”

“Humidity?”

It was sticky as summer in the shed, even though outside it was cold enough for one’s breath to fog. The shed was so full of steam it was almost hard to see.

“There’s a hot spring nearby, so w-we—we get our hot water there.” Lishu rolled back the rush mat on the shed floor to reveal a channel with water, no doubt quite hot, flowing through it. “If it gets too cold, we light a fire in the oven. We have to monitor the eggs constantly, so three of us work in shifts.”

It certainly did seem like too much for one person to handle alone. Even with two others to help, Basen worried that it must be all too much for Lishu, who had spent so much of her life as a sheltered princess.

“Are you sure you’re all right here, Lady Lishu?” he asked.

“A-All right how?”

“Well, a young woman of your station shouldn’t have to be here. You could be somewhere with ladies-in-waiting attending upon you. You may be a wayfarer, but that doesn’t change the fact that you are a princess of the U clan.”

The Emperor, Basen had heard, doted upon Lishu like his own daughter. And anyway, having been caught up in the White Lady’s schemes, she was really a victim herself. In his opinion, she deserved better than this.

“Master Basen...are you worried about me?”

“W-Worried?! No! It’s simply your right, milady...”

“O-Oh. N-No, of course. I shouldn’t have assumed you would be concerned about the likes of me...”

“That’s not what I meant at all!”

Basen cursed his mouth, which couldn’t seem to string two coherent words together. If the Moon Prince were here, he would have known what to say. Basen, however, could only look at the wall of the shed and feel miserable.

“Master Basen, a-are you quite all right?” Lishu peered at him with worry. No, no—Basen was the one who was worried.

“Lady Lishu...” he began. “You’ve suffered enough. You can go ahead and live the life you want now.”

Even Basen wasn’t sure what he was saying. The life she wanted? What was that? Basen’s life was duty to the Imperial family, protecting the Moon Prince. What he wanted didn’t come into it. And he had the temerity to lecture Lishu about choosing her own life? The words sounded hollow in his ears.

“Master Basen...” Lishu seemed like she could hardly speak.

Of course not. She must have been too scandalized. Too deeply offended by the “advice” Basen dispensed so cavalierly. He resolved to learn what he had come here to learn as fast as he could and then go home.

“I... I don’t know what I want yet. What I want has never mattered. I was never allowed to choose my own life.”

“Then start now.”

“I will. And what I want is to...to go on doing this for a while longer.” She squatted down and turned another egg.

Her clothes were filthy, her hair plain, and she wore no makeup at all. Yet on her face was something Basen had never seen there before: a small smile.

Chapter 5: Spring Comes to Basen (Part 2)

He’d thought of the young woman as like a little flower, gossamer and delicate. He’d been afraid she might break if he touched her.

Now, as Basen rode along on his horse, he looked at the side of the road, where a small blue flower was blooming. He had always thought of flowers as things to be cherished and loved, but he saw now that they grew on their own, with or without anyone to dote upon them.

He turned toward the farming village, his breath white in the air. A wagon loaded with ducks in cages clattered along beside him. When the eggs had hatched, he had raised the ducklings until they were big enough, and now he would take them to the villages. How many times had he done this now?

“Distributing ducks is beneath you, sir,” a soldier said.

This wasn’t the first time one of his subordinates had objected to his going on these trips. They might even think it was a waste—as the Moon Prince had warned him they might. Basen was well aware of how they felt. “I’ve been given a job, and I’m going to do it. If you don’t like this assignment, perhaps I can find you another one.”

“N-No, sir,” the soldier said, and neither he nor the others spoke up again—though they continued to share rueful looks. Even Basen, oblivious as he could be, could imagine what they said about him behind his back. He was the pampered second son of the Ma clan. The upstart from a branch family. Son of a eunuch. And more besides. Yes, his father Gaoshun came from a branch family of the clan—and to serve the Moon Prince, he had cast away the Ma name and spent nearly seven years pretending to be a eunuch.

Basen hated the idea of his father being belittled, but what would it gain him to mete out punishment here? The Ma clan were confidants of the Imperial family, and he would only be accused of abusing his position.

Basen had made the mistake of becoming emotional more than once before. On one occasion, an older soldier in his division had complained that he wasn’t being treated as well as Basen and claimed the younger man was being shown favoritism. Basen had lost his temper and fought the man in a “practice match” that was hardly less than a duel.

His opponent had ended up with three broken ribs and a broken right arm. Thankfully, none of the ribs had pierced a lung, and the arm had snapped cleanly and would heal. Nonetheless, the man had left the army. Perhaps he was humiliated by having been beaten by the younger, less experienced Basen—or perhaps he had simply never engaged in training fierce enough to break bones.

The Moon Prince was never less than committed, even when training. He could deflect Basen’s sword strokes with his blade. And Gaoshun, he would strike back mercilessly whenever he saw an opening in Basen’s guard. When Basen had been younger, even his older sister had been better at swordsmanship than him. He was physically strong, but never thought of himself as much of a swordsman. He had been good enough, though, to bring down that soldier, who had been very proud of his own strength.

He’d already known at that point that he had to be careful how much of his strength he used when dealing with women—but on that day he learned the same was true when he was facing men. He discovered his opponents were quite breakable. He never forgot the lesson: no matter what might be said to or of him, he must never be too eager to react with force.

“I can’t go around thrashing people...and I’d thrash them in a second,” he muttered to himself as he took a duck off the wagon and handed it to a farmer, along with a stern warning not to kill the animal. “We’re giving you these ducks as a pair. We’ll buy the eggs at a high price, and we recommend you breed more ducks too, but immediately killing them for food would be a mistake. You hear me?”

Some of these farmers already kept ducks, or had in the past, so thankfully Basen didn’t have to teach all of them how to raise the animals from scratch. He made sure they knew that the ducks would eat bugs and that this should be their primary diet, but also that if there weren’t enough of them, the ducks could eat leftovers, vegetable scraps, or even grass.

He could give the people all the warnings and advice he liked, but he had no way of knowing if they would listen. They might have thought he was something of a quack himself.

Just when he had made the rounds of the villages and thought he was done passing out animals, he heard a noisy quacking from the wagon. He discovered one young fledgling was still with him.

“Skwak!”

“You again, Jofu?” Basen gave the fledgling a look of annoyance. This particular bird had a black spot on her beak and seemed to think Basen was her mother, a profound mistake if there ever was one. Evidently this duck had hatched on the day of his reunion with Lishu, and Basen happened to be the first thing she saw. She followed him everywhere he went whenever he showed up at Red Plum Village, so he took to calling her Jofu, as if that were her name—although it really just meant “duck.”

Now he said to the duck, “You know what has to happen, right, Jofu? You’re going to go to some farm village, where you’ll be able to deal a crushing blow to those awful locusts! You can’t follow me around forever. Now’s your chance to build up the body a good soldier needs. Eat grains, eat grass, eat insects, and grow big!”

“Peep!” Jofu said and spread her wings. She almost appeared to be listening to him, but a duck is, well, a duck. Eventually, she would forget she had ever known Basen.

Or so he’d assumed. As he continued to take his young birds to the farming villages and then raise another group of chicks, Jofu was always with him, never staying behind in the villages. Basen and Jofu went out together and, inevitably, they came back together. More than once Basen tried to leave his fledgling in one of the farming villages, but each time Jofu would bite the farmers and climb onto the head of Basen’s horse, where she would flap her wings to be taken home. Jofu also got a beakful of the hands of several soldiers who tried to manhandle her. It got so bad that some soldiers began referring to the duck as respectfully as any senior officer.

Jofu’s feathers went from yellow to white, but the black spot on her beak remained, as did her tendency to savage strangers like a wild dog while following Basen around like a loyal one.

Today, too, Basen returned with Jofu riding on his shoulder. He would have to go to Red Plum Village to drop the bird off.

“That’s right...” Basen looked to the west, where the sun was setting, turning the sky red. The date had been set for the Moon Prince’s departure for the western capital. Basen’s next visit to Red Plum Village would most likely be his last. He would leave with another crop of ducks and distribute them to more villages on his own way west.

Word was that the westward expedition was likely to be a long one this time. A few months at least, the better part of a year more likely.

“Six months or more,” he mumbled with a sigh. He dismounted his horse as he passed through the gates of Red Plum Village. Being here always put him on edge. His heart raced despite the idyllic scenes of livestock roaming in the fields.

He told his subordinates to take care of the wagon, then headed for the duck shed. He seemed to walk quicker the closer he got.

He couldn’t help looking for Lishu, even though he knew she wasn’t always there when he came. Each time he saw her, so small and so delicate yet standing resolutely on her own two feet, he felt something very strange, a simultaneous rush of relief and anxiety.

And today? Would she be there today?

“M-Master Basen?”

His heart leaped. There was Lishu, in her plain clothes, holding a basket. Jofu jumped down off his shoulder and waddled toward the shed.

Basen pressed a hand to his chest and tried to order his pounding heart to be quiet. “Lady Lishu. I’d like to make my report to you, if I may.” He took out a map and circled the villages he had visited that day. With this, he had canvassed nearly all the frontier farm villages.

Red Plum Village wasn’t the only place raising ducks; there were others as well. The work would have to be able to go on after Basen left.

“It looks like you’ve taken them everywhere they could be needed. What will you do next?” Lishu asked, giving Basen a glance.

“Milady. I plan to take the next group with me and head west. I expect this will be my last visit here.”

Lishu blinked. “What?”

“My official duty is to serve as the Moon Prince’s bodyguard. He’s going to the western capital, so I must go with him.”

“He’s going again?”

The Moon Prince’s journey west had been made public at this point, but the news seemed not to have reached Lishu in her seclusion here. She knew of his first trip to the western capital, though, which had happened about this time last year, when she had still been a consort.

“I remember... That was where I first met you,” Basen said, although it pained him to imagine how he must have seemed to her at the time.

“Met me, and saved me—for the first time, but not the last.”

There had been a banquet at the western capital. A lion brought in for entertainment had attacked Lishu. Basen remembered her cowering under a table. Rumors called her a vile, shameless woman of no chastity, but all he’d seen was a frightened, lonely girl the world had never treated well.

Basen worried how she would get by in the future. Her mother was dead, while her father had only ever seen her as a political pawn—and he had been stripped of his station at the same time Lishu had come to this village.

Would she be all right? That worry had plagued Basen ever since Lishu left the court. Meeting her here had only added to his fears.

“...with me?” He was so lost in thought that he almost didn’t hear the words coming out of his own mouth.

“Wha?”

“Would you consider leaving Red Plum Village with me?” he repeated. Even he didn’t know what he thought he was saying. His face was beet red, and he couldn’t bring himself to look at Lishu.

Lishu, meanwhile, looked studiously at the ground. And was also blushing.

It must be his fault for having said something so outrageous. Might it be possible that time would turn back for him, just a few minutes?

Basen felt his breath grow ragged. “N-Never mind! It was nothing!”

“Nothing?” Lishu gave him a probing look, and the flush in her cheeks began to subside.