Character Profiles

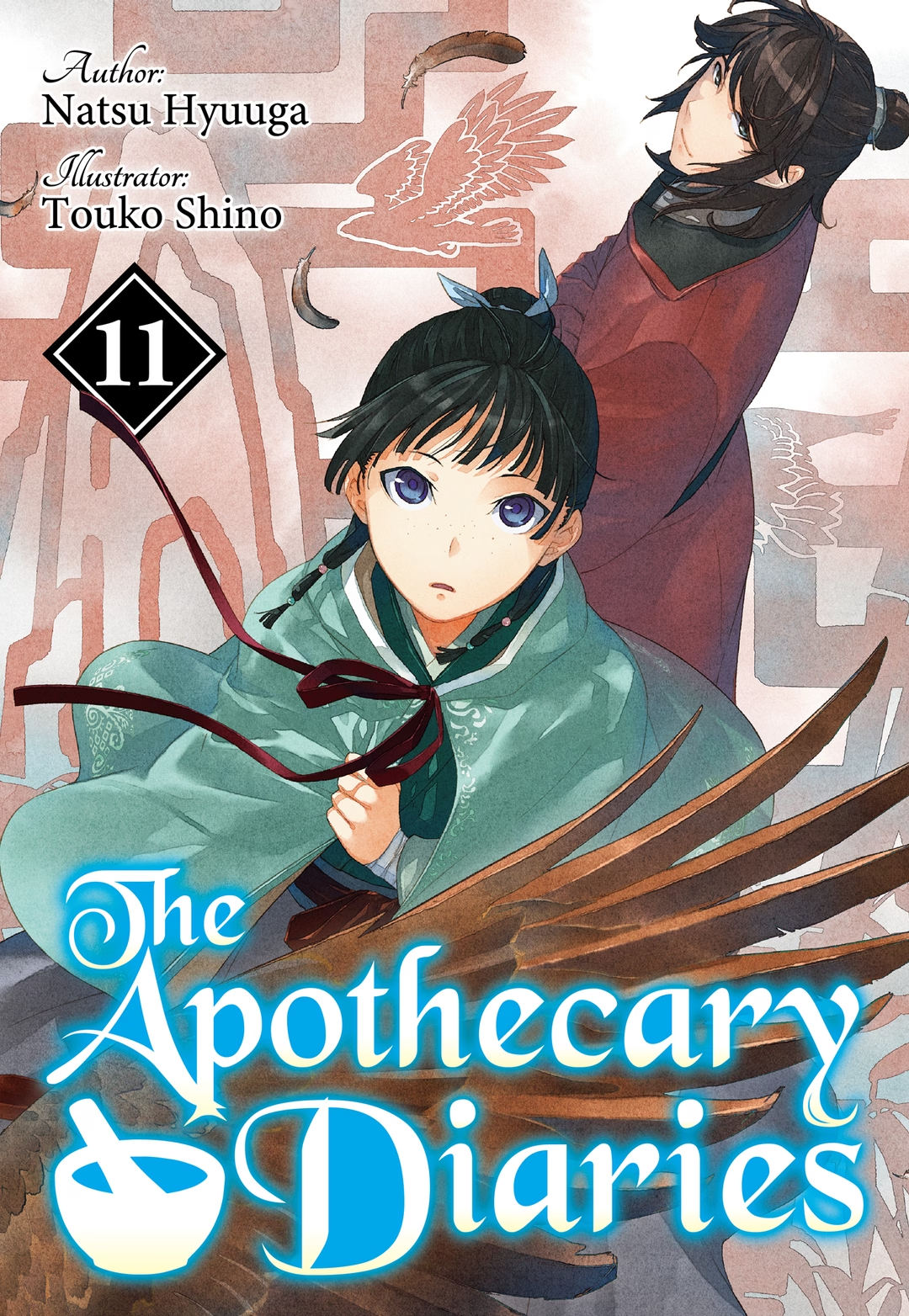

Maomao

Formerly an apothecary in the pleasure district. Downright obsessed with medicines and poisons, but largely uninterested in other matters. Has deep respect for her adoptive father Luomen. Twenty years old.

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. Inhumanly beautiful. He’s remarkably down to earth for someone so gorgeous, but there’s no telling what he might do if he lets himself go. Has an inferiority complex about his no-more-than-average intellectual abilities. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-one years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant. Doesn’t feel pain as acutely as most people, which gives him far greater physical capacities than most. He’s very serious, but that makes him easy to tweak. In love with Consort Lishu.

Gaoshun

Basen’s father. A well-built soldier, he was formerly Jinshi’s attendant, but now he serves the Emperor personally. He’s accompanying Jinshi on his expedition by order of His Majesty.

Chue

Baryou’s wife, and mother of his child. Not strikingly attractive, but she makes up for it with her initiative and silly personality.

Lakan

Maomao’s biological father and Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle. He’s a high-ranking member of the military, but his bizarre behavior causes people to avoid him. He loves Go and Shogi and is a formidable player.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. Twenty-two years old.

Rikuson

Once Lakan’s aide, he now serves in the western capital. He has a photographic memory for people’s faces.

Gyokuen

Empress Gyokuyou’s father. Officially the ruler of the western capital, but when his daughter ascended to the throne he moved to the royal capital.

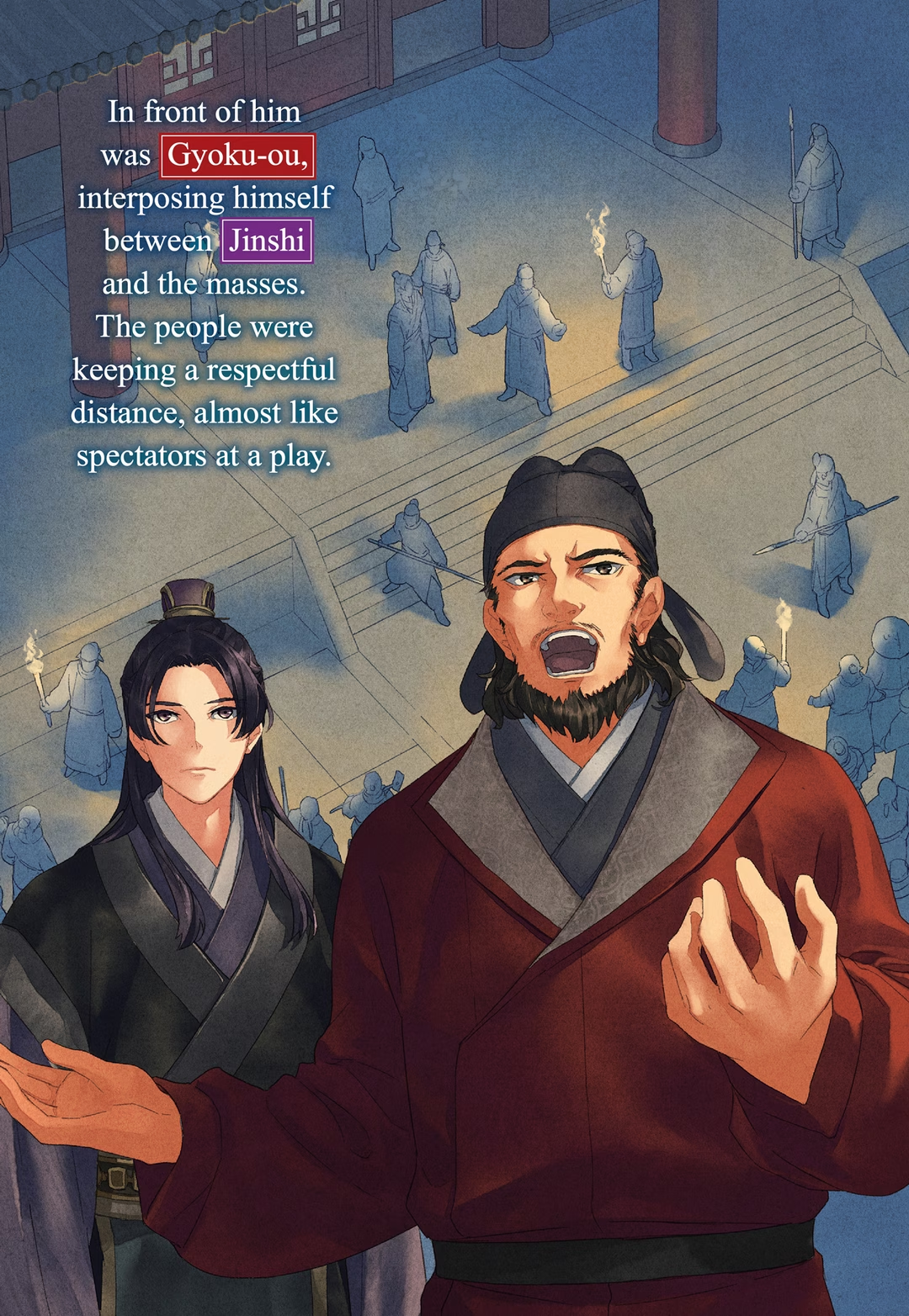

Gyoku-ou

Gyokuen’s eldest son; Empress Gyokuyou’s half-brother. Currently leads the western capital while his father is away.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting and former wet nurse.

Taomei

Basen’s mother and Gaoshun’s wife. Blind in one eye. A “masterpiece of a woman” who reminds one of a predatory animal. Six years older than Gaoshun.

Baryou

Gaoshun’s son and Basen’s older brother. Spends most of his time hidden behind a curtain.

Tianyu

One of Maomao’s colleagues; a young physician. He can seem frivolous, and he has a thing for En’en. He’s quick to stick his nose in whenever something interests him.

Dr. You

An upper physician who hails from the western capital.

Lahan’s Brother

Older brother of Lahan; Lakan’s nephew and adopted son. A perfectly ordinary person who shines when offering quips.

Prologue

He liked the sound of the carriages: the neighing of the horses, the creaking of the wheels, the shouting of the drivers.

He liked the sound of the marketplace: the calls of merchants, the bustle of the crowds, the laughter of children.

Even here, in this parched and arid place where people had to fight the land itself, they lived bravely.

That was a wonderful thing, his mother had taught him. The boy was often with her, and had heard her say it many times.

His mother worked with birds; she surveyed the whole world from a desk. She would laugh and tell him that one day, he would be able to do this too. Sometimes she would look deep into his eyes and appear to be thinking about something. Or sometimes, it seemed to him, remembering someone.

“Just make sure to protect this city,” she had said. The boy nodded assiduously. “Help it grow big and strong.”

The boy told her that he understood.

“Grow up to be just like your father,” she told him, and he replied with laughter that of course he would.

If the boy grew big and strong, so would the town.

They would have such abundance that a bad harvest would mean nothing to them, such strength that they would fear no enemy attack...

He wanted to be like his mother with her kindness; carry himself with his father’s authority.

He wanted these things so that his home, the western capital, could be richer and more beautiful than anywhere else.

Chapter 1: Dried Fruit

Maomao was at one of the stoves, cooking. Afraid she might poison herself if she didn’t get some air, she took a deep breath in, let it out again, then wrapped a hand towel around her nose and mouth.

It had been five days since the swarm, and they were finally almost rid of the grasshoppers around the medical office. There were a few survivors—at least until Maomao found them, whereupon she would crush them underfoot.

“Do we still need those poisonous plants?” Lihaku asked as he stirred a big pot.

“Yeah. There might be a second wave.” Maomao chopped some of the herbs in question with a cleaver and dumped them in the pot. “You need to make sure you cover your mouth, Master Lihaku.”

“Aw, it’s just a little smoke, isn’t it?” He frowned, not wanting to take the trouble.

“Do we remember what happened when we weren’t careful around the burned-out storehouse? Do we remember singeing our head?”

“Urk...” Lihaku obediently covered his nose and mouth.

“Miss Maomao! Miss Maomaaaao!” Chue appeared, announced by her distinctive tip-tapping footsteps. She was carrying a large box. “I got the extra medicine and bandages you wanted!”

“Thank you,” Maomao said, inspecting the contents of the box. “Is this all?”

“Afraid so,” Chue said with an apologetic look. Despite the box’s size, there wasn’t actually much in it. Certainly not nearly as much as Maomao had asked for. “Supplies are short everywhere. I think we’ll just have to make do.”

“Yes, of course. You’re right.”

The grasshoppers might be gone, but that didn’t mean they could relax. People were on edge, and that sort of anxiety could lead to outbreaks of violence. Some people were hurt, and many more were in poor health. Medicine always seemed to be in short supply already—with a contagion about, of course they wouldn’t have enough.

Maomao passed Chue a mortar and pestle, encouraging her to work too. Chue obligingly but resignedly rolled up her sleeves.

I don’t think we’ll run out of actual food. But there are other problems.

The bugs hadn’t gotten to all of the provisions in the grain silos, but there was a dearth of fruit and vegetables, meaning everyone would have an imbalanced diet for the foreseeable future.

The real trouble is a few months from now. Supplies would need to be closely regulated until the next harvest.

People could be complex and difficult. Just telling them that everything would be fine and to relax wouldn’t do the trick. As soon as they realized there wouldn’t be enough to go around, they would start hoarding. Soon there would be shortages, and then people would start to starve.

Maomao said, “I’m sure our dear acting governor is well aware of all that...”

“When you get right down to it, Master Gyoku-ou is a doer,” Chue replied pointedly.

“A doer?”

For a variety of reasons, Maomao was not personally a big fan of Gyoku-ou’s, but a mark of adulthood was the ability to separate personal animus from objective evaluation.

“He sent provisions and distributed food around the western capital and the surrounding towns, wherever there wasn’t enough to eat. Being quick to act, that’s worth a lot.”

A swift initial response would do much to reassure the populace.

“Started sharing right away, huh? Generous! I thought the powerful were supposed to try to keep everything for themselves,” Lihaku said, impressed.

“Right? But he sent carriages full of provisions, all carefully calculated based on the population and the extent of the damage to each area.” Chue never missed a thing, did she? She seemed to have checked all this out herself.

Wait. Is that... Was it all the stuff Rikuson had been preparing for so long? He’d made plenty of reports to Gyoku-ou. If the ruler had leveraged those, it would all make sense. If that’s true... It would show that Gyoku-ou wasn’t caught up in his pride, was willing to use anything and anyone he could, even those who had come from the central region. Maybe the reason he ordered Rikuson to stay behind in the village rather than coming straight home was precisely so as to get a better picture of what was happening on the ground.

Maomao couldn’t offer Gyoku-ou her unqualified approbation, not when she knew how he had used Jinshi as a convenient foil, hardly treating him like a real Imperial relative. Still, she had to admit that as one of those politicians who felt his first duty was to his homeland, Gyoku-ou was proving quite effective.

I know someone who could stand to learn a thing or two from him. She wondered how Jinshi felt about the way Gyoku-ou was treating him. The audacity of it doesn’t seem to bother him.

He did, however, chafe at his inability to act openly. He wanted to help, but his hands were tied by his status as a guest and visitor. Still, he did what he could, like sending Lihaku with Maomao to the farming village, or getting the freak strategist to form a bug-extermination team. Jinshi was like a duck—paddling like hell underneath.

Jinshi never seemed unduly attached to his power. Yes, he sometimes acted like a man of authority, but when had he really pressed his status as Imperial younger brother?

During the Shi clan rebellion, maybe, but that’s about the only time I can think of.

On that occasion, Jinshi had wielded his status openly. Maomao was in no position to criticize him—she had been one reason he had done what he did—but in any case, that was the moment His Majesty’s younger brother had been most visible to the public, quashing a rebellion.

Maomao knew that after that, Jinshi had begun to fulfill the duties of his station in life. He’d been as busy as he’d been during his time as a “eunuch”—maybe even busier—but much of his work was things that had been foisted upon him. As far as projects he chose to pursue of his own volition...

The preparations to counter the swarm are about the only thing I can think of.

People said he was worrying too much; they said he was raising taxes unreasonably; ordinary people and bureaucrats alike had regarded him with disdain, but still he had done it.

He should have made himself more visible. Like he was when he was a eunuch. Since returning to his position as Imperial younger brother, Jinshi had hardly used his most potent weapon: his looks.

Maybe he’s holding back so he doesn’t get flooded with suitors. Without the buffer of being a “eunuch,” and now with the added inducement of the power of being the Emperor’s younger brother, there would be no shortage of women who wished to become his queen.

Suitors, huh...

Maomao recalled Rikuson’s little joke. She could only assume Chue had reported it to Jinshi along with everything else. What a lot of trouble.

“Miss Chue, did you report everything?” Maomao asked. She deliberately chose not to say what she was thinking of—how Rikuson had asked, back in the village, if he might seek her hand in marriage.

“I’m not sure what report you mean, but don’t worry. It’s all kept top secret from our honored strategist,” Chue said.

Maomao paused. So she had told Jinshi. Lihaku gave them a look—he didn’t know what they were talking about—but he kept stirring the pot.

“If it was just a joke, then no harm done, right?” Chue said.

“Right. And it was just a joke.”

“Right. But some people might take it seriously.”

That was premeditated! Chue knew exactly what she was talking about. Maomao pictured Jinshi at his most troublesome. Boy, was she going to get an earful about this the next time they saw each other. Then again, maybe it would be all right...

“All done, young lady!” said the quack doctor, showing her a big, flat dish filled with rows of pills. Each of the pills was about as large as a grain of rice and very consistent in size, showing that he had used a mold to make them. Maomao remembered when she had first met the quack—she’d been shocked to discover he was producing the balls of medicine by hand, causing each one to be a slightly different size.

“Thank you very much. If you could deal with these next, please.”

“Sure! Don’t mind if I do.” The quack was in fine spirits, although it was hard to tell which of them was the physician and which the assistant.

Not to mention, somewhere along the line, Tianyu had disappeared. When Maomao went to find him to try to get him to help, she discovered him dissecting some former livestock at the cafeteria. In I-sei Province, adults were expected to be able to butcher animals, so a doctor who knew how to do the same didn’t raise any eyebrows. Maomao even started to think that maybe Tianyu had become a doctor precisely because he liked dissecting things.

“This is practice. Wouldn’t want to lose my edge,” he said, dangling one of the animal’s legs teasingly at Maomao. Being a prick, as usual.

Dr. You and the others were busy treating the injured and sick in town. Everyone who had been posted at the main house and the administrative office had their hands full trying to deal with the aftermath of the plague. The freak strategist in particular was always short-staffed, so he appropriated a few people from the annex as reinforcements, leaving the place quieter than usual.

Maomao took stock of the annex as she walked back to the medical office. A minimal handful of people had been left behind to guard Jinshi. The presence of lively souls like the quack and Chue made the place seem boisterous, but they were two of only a few voices to be heard around the annex. The bustling of the marketplace was absent, and there was no laughter of children playing. Occasionally, raised voices might be heard in a minor argument, but that was about all.

Wish I could go out there and get a look at the city, Maomao thought. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the time for a constitutional. Even if the weather was very nice.

The quack doctor, too, gazed out the window as he squeeeeeezed the mold down. He was checking the position of the sun. “I think it’s about snack time,” he mumbled longingly. Normally, snack time would see him off to the kitchen, somehow finagling himself some food.

“Hmm... I’m not sure snack time is on the cards today either,” Chue said with a sniff. “They’re filling up the storehouses and worried about staple foods. I think our little pleasures will have to wait.”

“Sure, sure...” said the quack, who had been enduring life without snacks for several days now.

If missing snack time is the worst of his troubles, he’s pretty lucky, Maomao thought as she started mixing up some medicine.

She was so focused on her concoction that she almost didn’t notice evening falling. She was just cleaning up tools when someone knocked loudly on the office door.

“Who’s there?” Lihaku demanded. He opened the door to find a young woman, white as a sheet. One of the ladies-in-waiting, maybe.

“Wh-Where’s the doctor?” she asked.

“The doctor? You mean me?” The quack trotted up with a blank expression. The woman had obviously come running as hard as she could, and he offered her a cup of water. “C-Come with me!” she cried. “Please! The young... The young mistress!”

Young mistress? Maomao wondered. She hadn’t heard about any mistress. Then again, this was Gyokuen’s home, so she was sure whoever this person was, they must be a relative of his. Even with only a few guards left, no one of suspicious background would be admitted to the annex.

It was obvious from the woman’s behavior that this was an emergency, but Maomao didn’t think dragging the quack doctor to the scene was going to get the poor maid very far. Knowing she couldn’t allow one of Gyokuen’s own relatives to go unattended, Maomao raised her hand. “If you’ll pardon me. The Master Physician is here exclusively to tend to the Moon Prince. We can’t let you just cart him off somewhere. Aren’t there any other doctors in this house?”

It was the most roundabout way of refusing that she could think of.

“They’re all out! Please! If someone doesn’t help her, the young mistress... She’ll...!”

Figured.

A special exception had been made for this annex because a member of the Imperial family was in residence—but the other doctors, including Dr. You, were all pressed into service to treat the commoners in town. If even they had to go serve in the city, how much busier must the local physicians be?

“Could you at least tell us what’s going on with your mistress?” Maomao asked, making the woman drink the water the quack had brought her. She slugged it down in a single gulp, then slowly let out a breath. “For starters, who is your mistress?” Maomao hated how long this was going to take, but she had to start at the beginning.

After a moment, the woman said, “She’s Master Gyokuen’s granddaughter.”

“How old is she?”

“Eight.”

“And her symptoms?”

“Well, she never did eat very much, but ever since the swarm of grasshoppers, she’s nearly stopped taking any food at all. The only thing she’s been willing to eat for days is fruit, but then today she complained her stomach hurt and vomited several times.”

Stomach pains and vomiting? Those symptoms could be almost anything.

“What kind of fruit did she eat today?” Maomao asked. Conceivably, the girl could have gotten food poisoning from consuming bad fruit, but even in an emergency like this, Maomao had trouble picturing a “young mistress” eating something rotten.

“Her mother gave her dried fruit.”

“Raisins, perchance?”

The woman shook her head. “No. Something that had been brought from the capital—I didn’t recognize it.”

“From the capital...” Maomao cocked her head. I-sei Province produced more dried fruit than the capital did. What was there in Kaou Province that they didn’t have here?

“It had reddish-brown skin and looked like it had been dusted in white powder,” the woman said.

Maomao’s eyes went wide. The lady-in-waiting seemed to be describing a dried persimmon. “All right. We’ll see your mistress right away. Where is she?” Maomao scrambled to get tools and medicines from the office shelves, then shoved them into a bag.

“Y-Young lady! You can’t just go running off on your own!” the quack cried.

“If we leave her, in the worst-case scenario, she might die!”

“D-D-Die?!” The quack trembled visibly. Lihaku picked up Maomao’s bag, while Chue seemed to have vanished in the meantime. “But... But I can’t leave the office...”

“I’ll go.” Maomao couldn’t exactly be sure-sure, but she was almost sure that the quack wouldn’t be able to treat the girl. She figured she would have to deal with this herself—but then someone else spoke up.

“Not by yourself you won’t, Niangniang. You’re not even a doctor.”

Who should it be but the man with the indolent grin? Tianyu was leaning against one of the posts in the medical office, a bag full of supplies already in his hand.

“I’ll go with you. At least I have the title of physician.”

He seemed to have gotten very interested in this case, but his presence made Maomao more anxious, not less.

“You’re coming with me?”

“No, Niangniang. You’re coming with me.”

Maomao stood in silence for a moment. He was right that according to the hierarchy, she was just there to help. And she had to admit that Tianyu was better than the quack when it came to actual doctoring.

“Miss Maomao, Miss Maomao!” Chue had reappeared in the meantime. “I reported to the Moon Prince.”

She worked quickly, all right.

“And what did he say?” Maomao asked. Even if she and Tianyu were willing to go see the patient, they wouldn’t be going anywhere without Jinshi’s permission. The lady-in-waiting, too, watched Chue intently.

“He says you can go ahead and go! Just make sure that you discuss the treatment very, verrry thoroughly with the patient!”

Lihaku looked like he was getting ready to accompany them; he was ordering another soldier to look after the quack.

Maomao turned to the worried servant and said, “Show us where we need to go.”

The lady-in-waiting guided them to a house near the annex. When they were ushered into the patient’s room, they found a woman in her mid-twenties by the bed—Maomao took her to be the child’s mother. She quaked violently. The sharply delineated features of her face were the picture of a classic western beauty.

A young girl lay on the bed, her face bloodless. She resembled her mother, but something, maybe the way she was lying there, made her look thin and weak.

Maomao and Tianyu asked Lihaku to wait at the door, then they went into the room. Chue had wanted to come with them, but this time she’d had to stay home.

“M-My daughter! Please, help my daughter!” The mother looked like she hadn’t even had time to brush her hair; it was stuck to her cheeks in messy strands.

“Yes, ma’am,” Tianyu said. He moved to pull the covers back from the patient, but the woman exclaimed, “What are you doing?!”

“I can’t very well examine the patient if I can’t see her,” he said. He was right, as far as it went—but these highborn houses were much concerned about chastity. They resisted the idea of a man looking at a woman’s body, even if the woman was a child of eight.

It was clear from the expression on Tianyu’s face that he had no interest whatsoever in a kid like this, but it was lost on her mother. Some people seemed to think doctors were all-powerful—that they could divine the patient’s condition, whatever it was, just by taking a pulse.

Maomao glanced at Tianyu.

“All right,” he said. “Would there be any issue if my assistant touches the patient?”

“N-No, I suppose that would be all right...”

Maomao bowed, then rolled back the covers. She took a spoon from her bag of tools and checked the inside of the girl’s mouth. She opened the patient’s eyelids and looked at her eyes.

“I’d like to open the patient’s robe. Would that be all right?” Maomao asked. She was speaking to the mother, but she glared at Tianyu, who held up his hands and turned around.

Maomao undid the robe and felt the patient’s abdomen. It was noticeably swollen. She slid her fingers across the skin, and when she found something that felt hard and round, she pressed gently. The girl groaned.

“Wh-What was that?” the mother said.

“Gas is trapped in the stomach. There’s a foreign object in her intestines that’s preventing it from escaping.” Just like I thought. Maomao had guessed the moment the lady-in-waiting said the girl had eaten dried persimmons.

“A foreign object?” The mother’s eyes went wide. She seemed to be searching her memory for anything unusual that her daughter might have swallowed.

“I was told she’s eaten nothing but fruit for the last several days,” Maomao said. “And today she had dried fruit—dried persimmons, yes?”

“That’s right. Even when she didn’t seem to have an appetite, she would eat sweet things. Because of those awful grasshoppers, we haven’t been able to get honey or fresh fruit, so I gave her some dried persimmons that we got as a gift. You don’t think they were poisoned, do you?!”

“No, it’s not poison,” Maomao said, gently rebuffing the mother as she tried to squeeze closer to her daughter. “Eating too many persimmons can cause stones in the stomach. How many persimmons did she eat?”

After a moment, the woman replied, “Three.”

“Three?” Pretty good job for a little kid. But not enough to cause a gastrolith, Maomao suspected. Is it possible? Could three persimmons do that? Maybe they got caught in the fibers from the other fruit?

She thought it through, trying to figure out if there was anything she was missing. A bead of sweat began to roll down the patient’s forehead, and Maomao absently wiped it away with a cloth.

Huh?!

Then she realized why the patient looked so haggard. Unlike her mother’s bountiful head of hair, the child’s hair was thin and scraggly, and it was turning white at the roots.

White hair?

It was said that a terrifying experience could turn the hair white—and there was no question that witnessing a huge swarm of grasshoppers would be a major shock for an eight-year-old child.

Well, now was the time for action, not thinking. But how to explain to the mother? They couldn’t just charge ahead.

“When there’s a foreign object in the stomach, there are three main modes of treatment,” Maomao began.

“Y-Yes?”

Maomao looked at Tianyu. He was still turned around, but even with his back to her she could see him nod. He was going to let her handle this part.

“First, you can give the patient water to help move the object through the insides and eventually evacuate it.”

The mother nodded.

“The second way, by contrast, is to administer liquid medication from below to encourage evacuation.”

From below—in other words, through the anus.

“Water! Bring water!” the panicked mother commanded a servant before even hearing what the third option was.

“I’m afraid in the case of your daughter, I can’t recommend it. It seems likely that she would simply vomit up any water she drank.”

“So you’re going with the second possibility?” the mother asked. She didn’t seem to like the idea of inserting medicine through the behind—but if that would have worked, they could have counted themselves lucky.

“No. Based on what I felt during my examination, I don’t think encouraging evacuation will flush out the object.”

“You can’t do the second thing either? What’s the third thing, then?” The woman fixed her with a look which, while not as potent as Taomei’s, was formidable nonetheless.

“We cut open her stomach and remove the obstruction by hand.”

Instantly the woman’s face hardened and she pounded a nearby table. “You think this is funny?! You want to cut open my daughter’s stomach?! You won’t lay a finger on her!”

The mother, naturally, refused the suggestion. She gave Maomao her most frightening look, eyes flashing.

About what I expected.

“You’re ordering us to attempt the first and second methods repeatedly in order to remove the obstruction?” Maomao said.

“I am, and you’d better do it quickly!”

“I’m afraid I can’t do what you’re asking in good conscience. The patient would most likely only die. If you absolutely must use those methods, you’ll have to do it yourself.”

Maomao kept her voice calm and level. She felt for the young girl lying agonized on the bed, but she couldn’t just administer a random treatment. If the girl died, there would be serious repercussions. If she ignored the mother and simply bulled ahead with a shocking treatment, however, she would get them thrown out.

There was only one choice: she had to persuade the mother.

“I have to warn you, I don’t think there’s time to consult with another doctor. If possible, I want to do the surgery right here, right now.” She looked at the mother, whose eyes darted to Tianyu.

“You’re a real doctor, aren’t you? What this...assistant of yours is saying can’t be right, can it?”

“I concur with her opinion,” Tianyu replied in his most serious tone. “A simple gastrolith could be treated with one of the two methods she described. However, the swelling of the stomach in this case indicates an intestinal blockage. Your daughter needs immediate attention.”

He sounded far more official than he usually did, but Maomao found herself on edge just the same. She was worried that he might slip back into his typical offhanded tone at any moment.

“If you cut into her belly... Won’t that mean she can no longer bear children?” the mother asked.

“We won’t touch the womb. The blockage is located far away from the reproductive organs,” Maomao said, communicating the results of her exam. She was lucky that the physical examination had revealed the location of the problem. If they kept their heads and worked calmly, this would be a relatively easy surgery.

At least, it would be for someone like Dr. Liu.

This wasn’t like attempting to remove lesions, or even extracting a shattered bone. Maomao tried to look steady, to reassure the mother.

“How much harm will you have to do? Whatever this thing is, it’s not small, is it?” the mother asked, looking at Maomao with anxiety all over her face.

“I’ll make a nine-centimeter incision in the skin. Then I’ll cut into the stomach, remove the blockage, and then sew everything up with thread. There will be a scar, but it should fade as she grows.”

Maomao couldn’t guarantee that the scar would disappear—a dire thought for the daughter of a noble family like this one.

“Nine centimeters...” The mother hesitated. But Maomao knew her daughter’s life had to be more important to her.

“That’s how long it will be if I do it.”

“What does that mean?”

Maomao looked at Tianyu. “If you allow the physician here to do the operation, I expect it would be less than half that length.”

Much as it kills me to say it.

Tianyu was, in fact, a gifted surgeon, as Maomao knew from seeing him dissect animals and work with cadavers. She might spend years practicing before she got as good as he was.

Just don’t let it go to your head, you little...

Dr. Liu had warned them repeatedly during the dissections: when they did a real surgery, it wasn’t going to be on a corpse. They were going to have a living, breathing human in front of them. There would be no room for error, he warned them, and they must always seek better surgical techniques. They could not allow themselves to kill a patient because they were caught up in their pride. Instead, they must throw away self-importance and rely on anyone and everyone they could.

So it was that Maomao said to the woman, “A physician bears that title for a reason. If you want the best chance of saving your daughter, then don’t ask a simple assistant like me to do this. You’d be better off trusting the doctor.”

The mother was silent for a long moment, hesitating. She looked at her suffering daughter, then narrowed her eyes and clenched her fist. “Go ahead.”

Maomao let out a sigh of relief. “We’ll need hot water and clean bandages. And could you start a fire for us?”

“Yes.”

“If possible, we also need some ice, but if that’s not available, whatever will most effectively cool the body.”

The mother called a servant and ordered them to prepare everything Maomao and Tianyu would need for the surgery. While they waited, the two opened their bags of tools and took out surgical garments and white aprons, which they put on.

As they got ready, Maomao told Tianyu what she had observed during her examination of the patient, as well as what she suspected the blockage was.

“Seriously? You think it’s...?”

“I can only speculate, but yes.”

She might lag behind him in dissection, but in terms of experience examining patients and assessing symptoms, Maomao was confident that she was ahead. She allowed herself a brief feeling of superiority at Tianyu’s surprise.

“Niangniang, I’m going to do the actual surgery, but maybe you could...”

“I’ll handle the anesthetic. Each of us can do what we’re best at. You have a surgical knife with you?”

“But of course.” Tianyu produced a finely honed knife. Maomao pulled out the medicines she’d brought along.

A child, eight years old, thin.

Yes, they were going to be cutting open her belly, but of course they wanted to minimize the pain as much as possible. Maomao had several analgesics with her. Poppy, thornapple, and henbane were the most well-known of such herbs, but many pain-killing medicines were also poisons. A misjudged dose could have serious consequences.

It was thornapple that Maomao had with her; she was more used to using it than either of the others. It’s often dissolved in wine to administer it, but I’d rather not. Luomen, Maomao’s mentor in all things medical, hadn’t approved of giving medications with wine. True, it would contribute to blunting the pain, but it could also cause changes in the body. It could encourage blood flow and make bleeding harder to stop. It was better avoided, especially with a child who would not be used to it.

Maomao had, in the past, treated a burn without suitable tools or even decent anesthetic, but that had been a special case in which she suspected pain also brought the patient a certain kind of pleasure. She would never normally do that. No, she would never do it again.

She weighed some medicine with a scale. The patient weighs... Let’s call it half what an adult does. She didn’t want to give the girl too much and cause side effects. She would have to work very carefully.

Maomao gently sat the patient up.

“It hurts...”

The girl had been so quiet that Maomao had thought she was asleep, but now she spoke. Maomao smiled a little, then tilted the patient’s chin up. “Take this. It will help.”

She wetted the girl’s lips with the painkiller and helped her drink it. It would take thirty minutes or so for the medicine to take effect. During that time, they could prepare.

“I brought ice,” said the servant, who arrived with ice wrapped in straw. Maomao took it and broke off some chunks, which she put in a leather bag and pressed against the patient’s stomach.

They say you should never chill the abdomen, but there are exceptions to every rule.

Maomao wanted to minimize the amount of painkillers she gave the girl, so instead she numbed the area by making it cold, just as she’d done with Jinshi.

Tianyu polished his little knife, then heated it in the fire. He also had scissors out, as well as something to hold open the incision.

“What do we do about thread?” Maomao asked.

“For the outside, silk. Everything inside, gut,” he replied.

Gut: very literally, thread made from animal intestines. Maomao carefully took out a cloth packet of thread and began inspecting each strand. Ideally, the size should be as consistent as possible, and they wanted to avoid any frayed strands. It was a fraught moment, assessing the implements; they were, after all, about to operate on a young girl.

Finally, Maomao had to make a request of the child’s mother. A cruel request.

“Sometimes the two of us won’t have enough hands during the operation. Could some of your servants help us? Someone who isn’t going to be too disturbed by the sight of blood?”

“What...needs to be done?” the girl’s mother asked.

“We’ve given her anesthetics, but it may not numb all the pain. I tried to go easy on the drugs so there wouldn’t be too many side effects. However, this means that someone may have to hold your daughter down while we work in case she starts thrashing from the pain.”

“Is there any chance I could do it?”

“Do you think you can retain your composure when you see your child in that much pain? Once we start the surgery, we won’t be able to stop.” Maomao gave the woman her most intense look. No matter how much the mother cared about her daughter, if she was going to get in the way, then Maomao needed her out of here.

The mother, however, surprised Maomao with her acquiescence. “All right,” she said. “Will two be enough?”

I thought for sure she would give me a hard time about it. The mother’s face was pale; she must have been near her limit. A servant offered her water.

The mother summoned two more servants, and Maomao instructed them to wash their hands, then dabbed their hands with alcohol. Both of the newcomers were doughty middle-aged women who didn’t look like they would cower at a little blood.

“All right. What say we get started?” said Tianyu, who had wrapped a cloth around his mouth and another around his head. They transferred the patient to an improvised surgical table that the servants had created by putting some long tables together. The patient was breathing much easier; perhaps the painkillers were taking effect. Maomao placed a rag in the girl’s mouth so she wouldn’t bite her tongue.

Then they had the servants hold the girl’s arms and legs. Maomao arranged an apron to cover everything but the operating site.

It was full dark outside, and they had several lights brought so that they could see where they were supposed to cut. To Maomao, it almost looked like the flames danced in answer to the patient’s breathing. In, out.

It was true: working on the living was different from working on the dead. However much they had chilled the skin, there would be blood. The blade of Tianyu’s knife was as fine as a razor.

Tools are an important part of doctoring, Maomao thought. Dr. Liu could exhort them as much as he liked to keep their ego out of it; it still annoyed Maomao that she wasn’t as skilled as Tianyu. If she could get her hands on some tools that might help close the gap, then she wanted to.

The patient was looking pretty out of it from the drugs, her perceptions successfully numbed. That came as a relief to Maomao, who wiped at the blood that poured forth as Tianyu worked.

“Here it is,” Tianyu said, his fingers brushing the swollen small intestine. He gently made an incision with his knife, then plunged a pair of forceps into the opening. Even the servants, who had watched them cut the girl’s stomach open without flinching, recoiled.

“Is there something in there?”

“You called it, Niangniang.”

With the forceps, Tianyu extracted a ball of undigested fruit fibers and a substantial quantity of hair that trailed from the intestine. Out and out it came as he pulled, dangling grotesquely.

Maomao offered Tianyu a tray, and he dropped the hair-and-fiber lump into it. There was still hair in the intestines, so Tianyu went back in with the forceps. Maomao had her mouth and nose covered, but even so the smell was nauseating, an acrid mix of blood and alcohol and stomach juices. The servants turned away as best they could, but they kept hold of the girl’s arms and legs, faithful to the end.

“I didn’t think a gastrolith formed exclusively of persimmon pits would be enough to cause an intestinal blockage,” Maomao said. The patient’s lack of appetite could probably be explained by her habit of eating her own hair. It wasn’t entirely uncommon—some people ate things that weren’t food as a response to stress. In this case, the girl had eaten more of her hair than usual because of the stress of the grasshopper plague, and exacerbated it with fibrous fruits and then persimmons. All of them together had formed the blockage.

Tianyu decided he had extracted all the hair he could and set the forceps aside. There were probably still strands in there, but they weren’t going to be able to get all of them. The rest could be addressed by drinking copious water and maybe taking some laxatives to help work them through.

Maomao passed Tianyu the needle and thread. She used a hook to hold the incision open, making it easier to see the intestines, and wiped up the blood as it continued to flow. Each time Tianyu finished with a stitch, he swapped for the scissors and cut the thread. He stayed stooped over the patient as sweat poured down his brow.

When she was sure they had tied the last knot, Maomao felt a wave of exhaustion. She wished they could just put the patient back in bed, but this wasn’t over yet. She wiped down the surgical site, taking care not to press too hard. Tianyu had been the star of the surgery itself, but it would fall on Maomao to care for the patient now that the procedure was over.

She’ll need more painkillers for sure, and I should prepare some fever medication. Something to stop infection too; that will be crucial. And I have to explain to them what she should eat and how to care for her now that the operation is over.

In other words, there was much to do. At the same time, Maomao wanted to ask the patient’s mother a few questions.

The servants who had been holding the girl down looked almost as spent as the doctors felt. The child had never fought, thankfully, but they were exhausted nonetheless.

“Say, Niangniang,” said Tianyu, who had already scrambled out of his blood-soaked surgical garment. He took the forceps and picked up the object they had extracted. “Do gastric juices make hair change color?” The hairball was discolored in places, brownish.

“Somewhat, maybe. Citrus juice can do it, after all.”

Maomao looked again at the patient’s hair. It was thin because she’d been pulling it out and eating it. The roots were white.

Maomao took the tray with the blockage on it and opened the door.

“Y-You’re finished?!” the girl’s mother asked. She was there, her face devoid of color. She must have been waiting at the door the entire time. Lihaku was simply sitting in a chair; he was used to waiting around.

“Yes, the surgery was a success,” Maomao said. “Would you come inside so we can give you some instructions?”

“Yes, of course.” The mother and a servant entered. The servant was the one who had summoned Maomao and Tianyu. As she and her mistress entered, the other two servants, the ones who had held the girl down, left the room.

“Who do you want to handle the instructions?” Maomao asked Tianyu.

“Hmm... Sounds annoying. You do it. Each of us does what we’re best at, right? Anyway, I get the feeling you’ve noticed something that was lost on me.”

As skilled a surgeon as he was, Tianyu was still Tianyu.

Once the mother and her servant were inside, Maomao made sure the door was closed, then showed them the tray. “This is what was stuck in your daughter’s intestines.”

The other two women cringed when they saw the undigested lump of fruit and hair.

“Why didn’t you tell us that your daughter has a habit of eating her own hair?”

The mother couldn’t quite meet Maomao’s eyes.

Maomao supplied her own answer. “No highborn person could bear the idea of anyone knowing their daughter did something so uncouth, could they? Fine.” She had half a mind to needle them about it a little more, but she would have to leave it at that. The issue was, they couldn’t afford to have something like this happen again. “Abnormal behaviors like eating one’s own hair are frequently caused by stress. Has anything happened to your daughter that might account for that?”

“No,” the woman said slowly. “No, I’ve only brought her up in the way that any...any mother would.”

Liar. Maomao picked up the lump with the forceps. The light and dark hairs formed a mottled pattern. “Your daughter’s hair is naturally auburn, isn’t it? You’ve been dying it black—that’s the source of the stress. Or am I wrong?”

The mother flinched; she pursed her lips and one eye began to twitch. Her lady-in-waiting looked at the ground.

“If we don’t resolve the cause, this will only happen again. How many times do you want your daughter’s stomach to be cut open?”

“It’s not like I enjoy doing it,” the mother said softly. “But the girl has light-brown hair, and her father and I... We both have black hair...”

“Even two parents with black hair can produce a child with brown hair. It must happen fairly often here in I-sei Province. There’s enough foreign blood going around.”

After a long moment the woman said, “My father won’t see it that way.”

Her father? That would be Gyoku-ou. What did he have to do with this?

“My father hates all foreign blood. I-sei Province is part of Li, so he believes it should be ruled by a black-haired Linese. I always thought the same thing.”

Until his own daughter gave birth to a grandchild with light hair.

“My father was distraught by his granddaughter. I had heard, though, that an infant’s hair color can grow darker with age, so I told him she would have black hair eventually. But she never did.”

So the white roots weren’t from hair that had gone white with fear, but because the mother hadn’t had time to redye her daughter’s hair during the swarm. Considering the servant wasn’t saying a thing, Maomao suspected she might be helping to dye the patient’s hair.

Hates foreigners, huh? That was a tough philosophy to get away with when you lived in a nexus of trade. Then again, sometimes familiarity was precisely what bred contempt.

Maomao thought of her red-haired Empress. Gyokuyou and her half-brother might both be Gyokuen’s children, but the family wasn’t monolithic, as this story showed.

“If she won’t stop eating her hair, then I suggest shaving her head until she calms down,” said Maomao. It seemed like the quickest way.

“Shave her head?! What is she, a nun?”

“If you let it keep growing, she’ll just have baldish patches, and will that look better? Besides, if she continues to damage the roots, eventually the hair will stop growing at all.” As she talked, Maomao began taking medicines out of her bag. Anti-infective agents, antipyretics, painkillers. “At the moment, seeing her safely through the hours and days after her surgery is more important. I’m going to give you detailed instructions. If you feel you don’t understand them, I can write down the important points. She needs someone to keep an eye on her postsurgical progress. It doesn’t have to be me and this physician if you don’t like us, but make sure you get some doctor to look at her. I do have to warn you that even if the surgery was a success, she could take a turn for the worse if she doesn’t get proper treatment after.”

If the wound opened or got infected, for example, there would be trouble.

“For now she’s still numb, so she’s calm, but as the painkillers wear off, it’s going to start hurting. Don’t let her touch the surgical site. The pain may keep her awake and she may run a fever. I have medicines here for both those possibilities that you can use as necessary.”

There was a moment as the woman absorbed all this, then she said, “I understand.” Her lip quivered as she approached the bed where her daughter slept. She brushed her thin hair, the faintest hint of relief on her face.

Finally Tianyu spoke up. “I kept the incision to half as long as my assistant said!”

And it was true: he had cut barely half of what Maomao had threatened. What was more, the stitches were as delicate as the incision; if all went well, the scar would be virtually invisible. Maomao couldn’t suppress a flash of annoyance even as she wrote down her instructions.

Wonder if she’ll really follow these.

She had her doubts—but she was very, very eager to get this over with and leave.

Chapter 2: The Strategist Strikes!

No sooner had they returned to the annex than they were summoned to Jinshi’s chambers.

Like it couldn’t wait till tomorrow!

It was the middle of the night; everyone but the guard on duty was sound asleep. The air was cold—and worse, Maomao hadn’t eaten dinner. She was desperate to be done with this.

When she reached Jinshi’s room, she discovered his desk riddled with abandoned drafts of numerous letters. Suiren or Taomei might have picked them up, had they been there; the fact they were still lying around showed that the ladies-in-waiting must really have their hands full. Maomao was clearly not the only one staying up late to work.

For a moment, she thought there was no one in the room—but then she happened to see Baryou peering out from behind a curtain. For a second, a charge went through the air between them, like two feral cats bumping into each other, and then Baryou vanished back behind his curtain without a word.

Something else, however, peeked out from behind the curtain in his stead: a duck with a black spot on her bill. Without Basen around, Baryou must be taking care of her. He wasn’t much for human company, but maybe a duck was all right.

I feel like there’s a real risk of her being eaten by Miss Chue. Apparently her husband’s protection was enough to save the duck from the wife’s cleaver.

“Oh, Maomao, you’re here,” said Suiren, who appeared from a back room. Maomao turned to her as if nothing out of the ordinary were going on.

“Yes, ma’am. I went to do a medical examination on Master Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter. I think Miss Chue told you about it. Tianyu the physician was with me; he’s at the medical office now.”

He’d dumped the entire reporting-to-Jinshi thing on Maomao, on the grounds of “each doing what we’re best at.” When she thought of him sitting down to dinner—late, but still earlier than her—she privately vowed to serve him another cup of swertia tea. For now, she gave Suiren a brief rundown.

“I’ll go call the Moon Prince,” the other woman said. Before she went, she collected the discarded letters and put them in a basket.

“That’s an awful lot of false starts,” Maomao remarked.

“He’s just been writing letters to anyone he thinks he can count on. He must have written close to a hundred—no, two hundred, even.”

“T—Two hundred?!”

From what Maomao could see of the attempted letters, each one began with the sort of fulsome, vacuous description of the season expected of a message from a member of the Imperial family. Yes, there was probably a more or less prescribed way to write such things, but even so, writing every single one of those letters by hand would have been enough to give a person tendinitis.

Maybe I should get a wet compress ready. Unfortunately, she’d come armed only with her usual bandages and balm.

Judging by the number of drafts lying around, Jinshi must have been corresponding not only with the most prominent bureaucrats, but the regional rulers as well.

“It’s great that he’s actually doing his job and all, but won’t begging everyone in sight for help sort of...take away from his gravitas?”

Maomao’s question provoked a sigh from Suiren—she seemed to agree that those who lived “above the clouds” shouldn’t be quite so quick to send letters to those who lived below them.

“Do you suppose that’s the sort of thing that would bother the Moon Prince?”

“No... No, I don’t.”

This was a man who had spent six years pretending to be a eunuch, a position that had given him a thorough familiarity with the slings and arrows of public opinion. He was probably less worried than anyone here about the rather coarse treatment he was receiving in the western capital.

“That’s why we need you to say something to him, Maomao!” Suiren said. “But...”

“But what?”

“Well... Good luck.” Suiren patted Maomao on the shoulder. For some reason, she was smiling.

Maomao soon discovered why, for Jinshi emerged from the bedroom. Chue and Gaoshun were with him, and from the moment Maomao saw the grin on Chue’s face and the way Gaoshun was pressing a hand to his forehead, she had a bad feeling about this.

Jinshi did not look like he was in a very good mood.

“Chue told me everything,” he said. “I gather you enjoyed yourself at the farming village?”

Huh! Haven’t seen him in this kind of mood for a while, Maomao thought. She wasn’t very happy with Chue for squealing on her.

“You and this man Rikuson, it sounds like you’re awfully close,” Jinshi continued. Pretty much what she’d expected.

“I’m not sure I’d say that, sir,” Maomao replied.

“Oh? Is that so?”

Yes? Yes. Yes, it’s so. Maomao glared at him. Chue stuck her tongue out and playfully bopped herself on the forehead. Gaoshun looked at his daughter-in-law as if lost for words.

All right. I’m angry. What did you say to him? Yes, Maomao understood that Chue had only been doing her job. But knowing that only took her so far.

“Then why were you so intent on going with him specifically to that village?”

“Because I know one carriage is cheaper than two. Besides, I thought it might be useful if we could share information with each other.”

“Hrm.” Maomao’s reasoning didn’t seem to satisfy Jinshi.

“Can I go back now? I answered the summons because I assumed you wanted to know about the surgery, but considering the hour, maybe all this could wait till tomorrow?” She’d intended to check Jinshi’s injury as well, but it looked like the thing to do was get out of here. The matter of Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter could wait too.

A high wall, however, appeared in front of Maomao. Thoom. Jinshi had risen from his seat and was standing smack in front of her.

“Yes, sir?” she asked. Jinshi continued to look less than pleased.

“It has come to my attention that this man with whom you claim not to be especially close recently proposed marriage to you.”

At least he was to the point.

“I’m given to understand that it was a joke, sir.”

“Does one say such things in jest?”

“Perhaps it was a social nicety, like the hair stick Master Lihaku gave me at the garden party.” She recalled Jinshi had been likewise petulant on that occasion. Maomao, for her part, had faith that there would be no problem if she was upfront and honest.

Jinshi fell silent. He looked like he very, very much wanted to say something, but—despite all appearances to the contrary—he was a busy man with much to do.

In a bid to change the subject, Maomao decided to make the report she had come here expecting to make. “The surgery on Master Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter was a success. However, I’d like to continue doing periodic exams to check the progress of her recovery. I assume that will be all right?”

“Ah, yes... I’ve already been in touch with Sir Gyoku-ou. He tells me you may do as you see fit.”

“I see, sir.” Didn’t grandfathers usually dote on their granddaughters? Gyoku-ou’s answer seemed so...disinterested. Perhaps it only sounded that way because she was hearing it through Jinshi.

So he hates foreign blood, does he? Maomao thought, recalling what Gyoku-ou’s daughter had told her.

“And what was the trouble with the patient?” Jinshi asked, sitting in a chair.

Maomao let out a deep mental breath and resolved to avoid the subject of Rikuson in the future if at all possible. “It was an intestinal blockage. A foreign object stuck in her innards, which we removed in a surgical procedure. The actual surgery was handled by Tianyu, that new physician. I served as his assistant.”

“Hoh. Here I would have guessed you would be champing at the bit to do it yourself.”

“I would have been willing.” It was, after all, a rare opportunity to gain surgical experience with a relatively safe procedure, and Maomao was as eager as anyone to take advantage of it. “However, the simple fact is that Tianyu far outstrips me in surgical skill.”

“There’s a surprise.” Jinshi almost looked a little disappointed, as if he wished Maomao had performed the surgery.

The last thing I want is anyone complaining about my surgical treatment. Maybe it was too late with Jinshi—he knew about Maomao’s extensive, personal experience with poisons, and was also aware that she had once lopped off a man’s arm in the name of saving his life.

“So what was this blockage?” Jinshi asked.

“Trust me, sir, you’d rather not know.”

“Tell me it wasn’t grasshoppers.” Maomao saw him blanch a little.

She shook her head. “No, it wasn’t. The blockage was a lump of fruit and hair.”

“Hair?” Jinshi looked perplexed, and Chue and Gaoshun also glanced at Maomao, curious.

She gave them the summary. This included mentioning Gyoku-ou’s distaste for foreigners, but that seemed to come as no shock to Jinshi. He simply said, “He hates foreigners, does he?”

“Do you have someone in mind, sir?” Maomao asked.

“Yes,” he murmured, then intertwined his fingers and narrowed his eyes. “Are you aware of the relationship between Empress Gyokuyou and Sir Gyoku-ou?”

“Vaguely.”

Some time ago, there had been a commotion when the Empress had lost a hair stick. Haku-u, a lady-in-waiting who was quite close with the Empress, had said a few things that came back to Maomao now.

“This is about the matter of Empress Gyokuyou’s ladies-in-waiting, isn’t it?” she asked.

“That’s right. When I was in the central region, the Empress seemed to get along perfectly well with her brother.”

“Only seemed to, sir?” Maomao gave him a puzzled look.

“I mean, I assumed—because during her time in the rear palace, she often got letters from ‘her brother.’ That was true, as far as it went—in that Gyoku-ou is not her only brother.”

“Ah!”

Gyoku-ou and Gyokuyou were far enough apart in age to be father and daughter. It would be no surprise if there were other siblings between them.

“Once I realized that, I saw that there had been signs, even back when I was in charge of the rear palace. The minimal number of her ladies-in-waiting, for example, should have been a tip-off, don’t you think?”

It was certainly true that Gyokuyou had had fewer ladies than the other upper consorts. Even the fact that Maomao, a simple laundry girl, had been admitted to the Jade Pavilion was only thanks to Jinshi’s finagling. Yes, Gyokuyou had lost several ladies-in-waiting to food tasting, and her home was far away in the west, but it now transpired that such things had been only cover, excuses.

“Does Master Gyoku-ou view Empress Gyokuyou as an enemy, then? I mean, because he takes exception to her foreign blood?” asked Maomao.

“That, I don’t know. For all his alleged hatred, he did send an adopted daughter who looks much like the Empress into the rear palace.”

“With a pucker on his face, perhaps.”

Had Gyoku-ou had some negative experience with foreigners in the past? True, it was considered bad form to have strong preferences—in people as in food—but Maomao herself had people that she, ahem, couldn’t stand. She was in no position to judge.

Nonetheless she said, “If he really hates foreigners, he must have a hard life. Living as he does in the one place in Li with more foreigners than anywhere else.”

“That may be precisely the problem. More people, more points of friction.”

Maomao was starting to feel that further discussion of this topic wouldn’t get them much of anywhere. Time to bail out of this subject. She glanced around the room, looking for some chance to escape.

Just then, the door flew open with a crash. “Moon Prince!” In came a young personage with a duck on his head. In all the western capital, there was only one man who fit that description.

“You’ll wake up half the household, Basen,” Jinshi said, paying no heed to the avian.

“I’m sorry, sir. It’s urgent...”

“Urgent? Well, what is it? Tell me!”

“Grand Commandant Kan is on his way here!”

“Does he know what time it is?”

Maomao’s hair stood on end, and if she’d had a tail, it would have puffed right up. Since their arrival in the western capital, the grand commandant had visited Jinshi on several occasions, at which times Maomao had always been careful to make herself scarce, or otherwise to leave matters to the quack doctor.

“I’m here...” said a most terrible voice. Behind Basen loomed the face of an old man, a creature so filthy he just looked like his feet must stink. The duck seemed to mistake his hair for nesting material, because she reached over from atop Basen and pecked at his head.

“Basen!” Jinshi fixed the other man with a glare.

“I’m sorry, sir. The Grant Commandant is...already here,” he said, correcting himself.

“Maomaoooooo! Thank goodness you’re safe!” The monocled old fart tried to shove past Basen, but Basen didn’t budge. The best the freak could do was sort of shloop himself in between Basen and the doorway.

Gaoshun immediately positioned himself to defend Jinshi, while Chue stood in front of Maomao and gave her a let-me-handle-this wink and a thumbs-up.

You can act as friendly as you want—it doesn’t change the fact that you sold me out.

For the moment Maomao made it her priority to put some distance between herself and the old guy sidling in her direction.

“All those bugs must have been so scary, Maomao! But oooh, don’t you worry. Daddy made a bug extermination squad and will get rid of all those nasty, nasty insects for you!”

Sure. This is when he decides to get off his ass.

Maomao and the freak strategist shuffled right, then left, stopped, and shuffled again, Chue between them.

Jinshi, observing the moment, cleared his throat to draw the strategist’s attention to himself. “Sir Lakan. I believe I’ve asked you—repeatedly—to inform me before you come here. But since you’re here, what is your business?” A blue vein bulged on Jinshi’s forehead. He knew the answer to his question all too well.

For just a second, the strategist deemed to look at him. “Heavens. I don’t need a reason to come visit my beloved daughter! I went to see her this evening and found she was out, so I just tried somewhere else.” He gave them a sort of mischievous leer. Maomao felt bad to take the opportunity from Basen, who was holding his temper in check quite well, but she wondered if she might be allowed to give the strategist a good kick.

He returned his gaze to Maomao and grinned again, but then his face grew serious. “That was my main motivation for coming, anyway. But there is one more little thing. I’d like you to take the Sage in.”

“The Sage? He’s here?” Jinshi asked, disbelieving.

I think I recognize that name. As Maomao recalled, it was the man who had been watching Jinshi’s game against the freak strategist in the Go tournament. The Emperor’s personal instructor in the game.

“No, no, not him. Maybe I should call him the Western Sage. He’s a prodigy in Shogi, not Go.”

“Shogi?”

The freak strategist was a brilliant player of both games, but he was said to be even more dominant in Shogi than in Go. And yet here was someone he referred to as a “sage” of the game.

“He lost his home in the insect plague, you see. So he turned to me, an old friend.”

Old friend, huh?

Maomao had heard that the strategist had spent some time in the provinces in his younger days. It wasn’t beyond the realm of possibility that he had visited these distant western reaches.

“I see. Yes, there’s been trouble all over,” Jinshi said, and hmmed thoughtfully.

“’Scuse meee!” Chue, with scant respect for the gravity of the moment, stuck her hand in the air. Her mother-in-law was absent today, so there was nothing to stop her. “Not to be rude, but do you think you might be making it all up?”

Rude—yes, it was, but Maomao agreed with the question. This was, after all, the freak strategist, a man who couldn’t remember people’s faces to save his life. If someone came along impersonating an old acquaintance, how would he know the difference?

“I doubt it. There aren’t that many gold generals running around, although I do want to try to be certain.”

A Gold General! Luomen had told Maomao that the strategist often spoke of people in terms of Shogi pieces, but the average listener would probably have no idea what he was talking about.

“So perhaps we could have a game of Shogi here, just to be sure?” the strategist suggested.

His idea was met with a moment of silence. Maomao wasn’t sure how it followed that there should be a game here and now, but the aide trailing behind the Grand Commandant was carrying a splendid Shogi board. The strategist himself evidently considered the game a foregone conclusion.

“I reiterate... Do you know what time it is?” Jinshi said.

“Oh, please. If he’s the real thing, you might gain some useful information yourself, Moon Prince.” The freak gave Jinshi one of his unctuous smiles.

Jinshi glanced at Maomao. She tried to respond with a don’t-do-it gesture, but from the moment the strategist had found her, there had been no escape. Better to let him waste his time playing his game, then—and anyway, she wondered at his ominous remark.

“All right. I’ll provide a place for you to play Shogi. However, the game will wait until tomorrow.”

“That’s very kind of you, thank you indeed,” the strategist said. (It was hard to tell whether he was genuinely grateful or not.) Maomao tried to ignore the freak, who was smiling to himself. Instead she rubbed her grumbling belly and hoped she could eat dinner soon.

Chapter 3: Big Lin

The next day, Chue all but dragged Maomao to a big room somewhere in the annex. It had been strung with mosquito netting, and there was a thick carpet on the ground.

Very Anan-esque, Maomao thought. There were no tables, just a couple of low-set chairs. Tea and snacks had been set out on the carpet—not the finest stuff; the swarm had curtailed such luxuries. But beggars could not be choosers.

In the center of the room was a Shogi board. Staring intently at it was one filthy old fart Maomao recognized, and another she didn’t. The first fart was, of course, the freak strategist, but the second?

Must be his Shogi partner.

She’d heard the man was more than eighty years old. He must have been imposing in his day, but now he was hunched and his body shook visibly. A sturdy cane lay to his right, while behind him a middle-aged man, seemingly his caretaker, looked on with worry.

“I brought her!” Chue said with an enthusiastic raise of her hand. Maomao had, naturally, resisted the idea of coming here, but Chue had dragged her. Lihaku even accompanied them as her bodyguard.

The freak strategist looked up from the board. “Ma... Maom—” he began, but he was interrupted by what sounded like something striking a pillow. It was the cane, which had been pounded firmly into the carpet, so hard that Maomao feared it might have broken had it not been for the thick rug.

“We are in the middle of a game!” the other man bellowed, the force of his pronouncement shocking in light of his doddering appearance. Then he picked up one of his pieces and moved it forward, snapping it down with a perfect click.

The monocled freak narrowed his eyes and refocused on the board, sparing Maomao only a wave of his hand.

“Oooh, that was a nice move,” said Chue, who was at least pretending to pay attention.

“If you say so! It’s lost on me. You know what’s going on there, Miss Chue?” Lihaku asked with a friendly laugh.

“Oh, it just seemed like the thing to say. You know, what with the way he smacked that piece down.”

She didn’t have any idea what the move meant; she’d just said what felt right to her. As usual.

“Now, come on, Miss Maomao. Let’s get some of that tea! Miss Chue needs it if she’s going to have her snack.”

Maomao and the others sat on the carpet. Summer in the western capital was warmer than in the central region, but at least it wasn’t as humid. The mosquito netting was, in fact, grasshopper netting, as some of the bugs were still around.

You can feel the money, Maomao thought, running her fingers through the carpet. It was cool like silk but soft like wool, and had a delicately woven pattern as well as embroidery. Even the netting was made of silk gauze, which shifted and shimmered with each passing breeze.

Maomao sat in one of the low chairs and took a bun, a fried mandarin roll topped with condensed milk added.

I guess it doesn’t matter how fancy the carpet is. You can still get crumbs on it.

The strategist was stuffing his face as he played, consuming the snacks with such gusto that his long-suffering aide struggled to keep them supplied.

“Onsooou! You can do it!” Chue called to him.

Onsou? Is that his name? Maomao hadn’t heard it before—she’d never really had a reason to—and even if she had, she probably would have forgotten it. It seemed likely she’d see more of Onsou in the future, though, so she would have to try to remember.

“Ha ha! Ol’ Onsou. It’s not easy being him, is it?” said Lihaku, not sounding terribly concerned. As a fellow soldier, he seemed to recognize the man.

When Onsou saw Maomao, he commanded a nearby servant to prepare enough snacks to make up the shortfall. He was obviously used to this. Once he had deposited a sufficient quantity of sweets in front of the strategist, he came over to Maomao. “I’m terribly sorry. I know he’s always dropping in on you.” He bowed to her, profoundly apologetic. The angle of his bow was flawless; clearly, this wasn’t the first time he’d had to say sorry on the strategist’s behalf.

This is good material, here. The old madam would have killed for someone who could apologize like that. Onsou wasn’t young enough to be called a young man anymore, yet he knew how to be humble without looking pathetic or incompetent. Exactly the kind of person one needed when placating irate customers after some inexperienced courtesan had upset them. The real complainers, the ones who couldn’t be satisfied by a heartfelt apology, could always be thrown out on their ears by the menservants.

I wonder if he’d be interested in a new line of work. I could introduce him.

Being the official apologizer for a brothel wasn’t easy on the nerves, but it had to be better than being the freak strategist’s personal assistant.

Jinshi wasn’t there yet—maybe he wasn’t coming at all.

If he’s not careful, people might just get even more angry with him for being somewhere like this. At times of crisis such as the one they now faced, there was scant time for Shogi or banquets. This game was only being permitted because it was personally hosted by the freak strategist.

“Sure doesn’t look like this guy is a fraudster,” Maomao remarked. Anyone who could get the freak strategist to pay that much attention to a game of Shogi had to be quite the player themselves.

“No,” Onsou agreed. “That’s Big Lin, in the flesh.”

“‘Big Lin’... So is he famous or something?”

“Back in the day, they say Shogi players came from far and wide to play against him, even from the central region. He was that strong. If he hadn’t fallen on hard times, he’d probably be even more well-known now.”

“What happened?” Maomao asked, her interest piqued by the remark.

“Oh... Ahem. Well, since I’m sure I’d end up explaining it to you sooner or later, might as well get it out of the way. It’s related to that useful information that Master Lakan mentioned.” Onsou kept his voice down, mindful of the surly old man. “Big Lin was once a bureaucrat of some renown. He’s quite thoroughly versed in the history of the western capital.”

“I could believe it,” Maomao said. The years had perhaps made him less obviously charismatic, but his full-throated shout earlier had convinced her he was by no means gone.

“If I told you his fate was decided seventeen years ago, would you know what I meant?”

“You’re referring to the situation with the Yi clan?” Maomao’s eyes widened.

“Yes, exactly. The Yi trusted Big Lin implicitly, and even after he retired from official life, he continued to compile their history. When the Yi were wiped out, however, many officials found themselves caught in the purge—especially those the Yi had trusted most. Big Lin emerged with his life, but the successive shocks of those events pushed him into senility.”

“That is useful information,” Maomao said. It implied that Big Lin might well know things Maomao and Jinshi would be very eager to learn. Then, however, Maomao made a sound of confusion. “Hold on. You seem awfully familiar with the fall of the Yi yourself, Onsou. Even Master Gaoshun doesn’t know much about it.” She looked at him and narrowed her eyes.

“Oh, I’m sorry, you didn’t know? Their destruction took place at exactly the time Master Lakan was in residence at the western capital. I’ve heard the stories, that’s all.”

Maomao glowered at the freak strategist as he played Shogi. I haven’t. Then again, she had never asked—but still, the thought made her unreasonably angry.

“Master Lakan being who he is, of course, most of his recollections consist of Go halls and Shogi dojos. Given his tendency to forget anything not of personal interest to him, I’m not sure he can offer the kind of information the Moon Prince may be hoping for. In this particular case, I suspect he only remembers as much as he does because he finds Big Lin himself memorable.”

“Wouldn’t be surprised,” Maomao said. Asking the strategist detailed questions about the Yi would probably be futile, but they already knew that.

“If only Big Lin were still of sound mind, he could probably tell you a great deal about those times. From what I hear, he does have moments of lucidity...but only moments.”

“Moments,” Maomao repeated. She had, indeed, heard that people suffering from senility sometimes suddenly returned to their right minds. Onsou seemed to be suggesting that they should try to catch Big Lin during one of those spells.

“Indeed,” Onsou said. “Oh, Master Lakan is calling for me. I have to go. We can speak more about this later.” He bustled back over to the strategist—this time, the freak was out of juice.

Maomao peered around the large sitting room. She saw the freak strategist, Onsou, and Big Lin, along with Big Lin’s caretaker. Then there was herself, Chue, and Lihaku. Jinshi and his retinue were still nowhere to be seen.

Might not have a choice this time, Maomao thought. If Jinshi didn’t show up, she and the others would have to try to get the information themselves. It would be pointless to try anything, though, before the Shogi game was over, so she decided to get more snacks instead.

“Miss Maomao, this fried bread is the best!” Chue informed her.

“How many of those have you had, Miss Chue?”

“I’m checking them for poison,” she replied with a completely straight face.

“I can do that for myself, thank you.”

The snacks that had been provided were indeed very tasty, but the tragedy of it was that there was no wine at all. Yes, yes, there was a food shortage; they were lucky to be able to eat at all, etc. They would just have to suck it up and endure.

While the strategist was sipping his refilled juice, Onsou returned to the onlookers. “Perhaps you would take this,” he said, handing something to Maomao.

“What is it?” she asked.

He’d handed her a book. Made with parchment paper, it was a collection of short stories. She would have preferred an encyclopedia of medicinal herbs or maybe a medical treatise, but this wasn’t a bad choice either.

“I can bring you any other books you need as well. Or perhaps you’d prefer board games and cards?” Onsou said. He was being so helpful toward Maomao and the others, in fact, that she was starting to get suspicious.

“Thank you for your consideration, but we’ll be fine,” she said pointedly.

“I... Well... Are you quite sure about that?” Onsou seemed distinctly ill at ease. “Master Lakan and Big Lin began their game two hours ago, and...well.”

“Yes?”

“I think we can expect it to go on at least four hours more.”

“F-Four...hours...”

“You may wish to know that the Moon Prince was here just before you were, but he left again. He said he was quite busy with work. I’m supposed to call him when the game is over.”

For Jinshi, there was no such thing as free time. If working until the game was done was the sensible thing to do, why couldn’t Maomao leave too? There was plenty of medicine Dr. You had asked her to make.

“Do you think I could get out of here? You can call me when the game is over,” she said, collecting a tray of fruit and buns. They would make the quack doctor, lately beset by the woes of a snackless life, very happy.

“I’m sorry, but no. If you were to leave now, Master Lakan would lose his concentration. And if he were to make any...unorthodox moves, Big Lin would get tired and fall asleep.”

Argh! What a pain in the ass. Maomao did worry that, after another four hours of Shogi, the eighty-year-old man might simply keel over. One more reason I can’t leave...

She would have to stay and make sure that the old guy didn’t collapse. She compromised as best she could, having her mortar, pestle, and medicinal ingredients brought and mortar-ing away with Chue and Lihaku while the old men played.

Is that guy going to last? she wondered as she crushed some herbs and watched Big Lin, whose hand trembled every time he moved a piece. Once in a while, the man attending him would press some damp cotton to Big Lin’s lips. Other times, he would help Big Lin to his feet, then take him to the bathroom.

Looks like he’s used to nursing.

The other man must have been more than forty himself—a son, or perhaps more likely, a grandson. It looked like maybe Big Lin’s continued survival was thanks to this man’s patient ministrations.

When Onsou next came by to check on them, Maomao motioned him over. “Who’s the man with Big Lin?” she asked.

“Some extended relative. Big Lin has no more close family. Master Lakan always refers to him as Small Lin.”

“Small Lin?”

Small. That could certainly refer to a child, but just as often it meant someone who was small-hearted, a jerk. Even if the usage was simply a pair with “Big Lin,” it still wasn’t a particularly polite thing to call a person. In that respect, it was very much in character for the freak strategist.

So it went, precious time slipping through Maomao’s fingers.

After an hour, they had filled a tray with round pills. Onsou, who seemed less nervous around them than with the strategist, was hard at work helping them with the task. Maomao shook the tray to straighten out the rows—and at just that moment, Big Lin slumped over.

Shocked, Maomao rushed to the players.

“Oh! Maomao,” the freak strategist said with a grin. She shoved him aside, out of the way, and went to tend the other old man.

Before she could even reach him, though, someone shouted, “Nothing’s wrong!” It was Small Lin, who propped up Big Lin and leaned in as the old man began to whisper something.

“Yes... Yes,” Small Lin said. Maomao couldn’t hear what Big Lin was saying, but Small Lin was taking it down. Maomao took a peek, only to discover rows of writing whose meaning she couldn’t fathom.

At length Big Lin’s dictation seemed to end. Small Lin rubbed the man’s back gently and wetted his lips with the cotton rag.

“All finished, Small Lin?” the freak strategist asked with a glance at Maomao.

“He’s exhausted. We should let him rest,” Small Lin replied, evidently unbothered by the strategist’s tone. He laid the elderly man down gently, then began taking a record of the state of the game board.

“Caretaking’s not easy, huh?” said Chue as she grabbed another bun—this time from the strategist’s plate—and stuffed it into her mouth. She sounded totally indifferent on the subject. Maomao worried for Gaoshun and Taomei in their old age.

“Maomaaaooo!” cried a lilting voice. The strategist began to work his way over to her.

Maomao frowned in disgust. “Please don’t get any closer. You smell like a dog that’s been out in the rain.”

“Wow, that...really sounds hurtful when you just say it like that,” Lihaku remarked.