Character Profiles

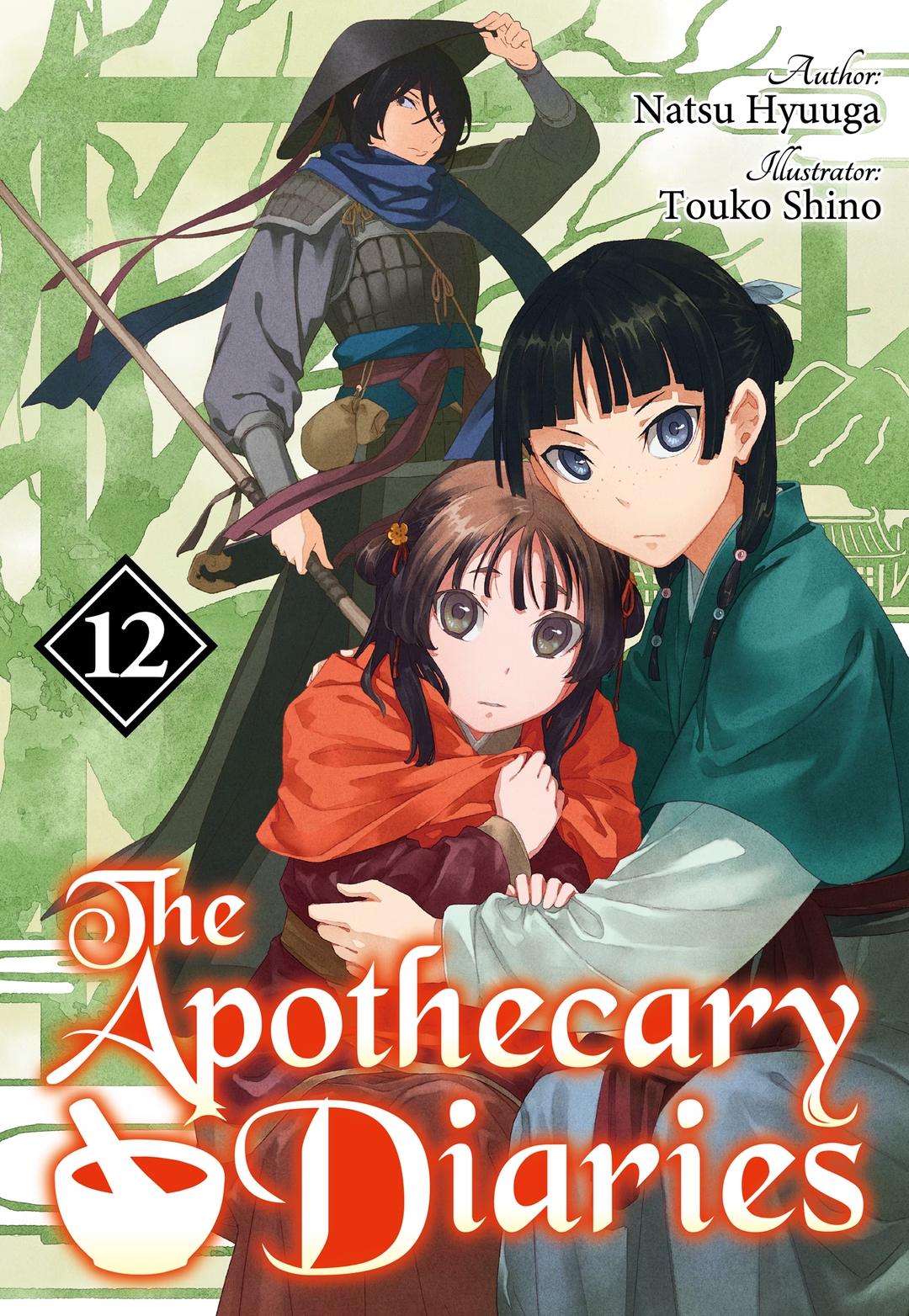

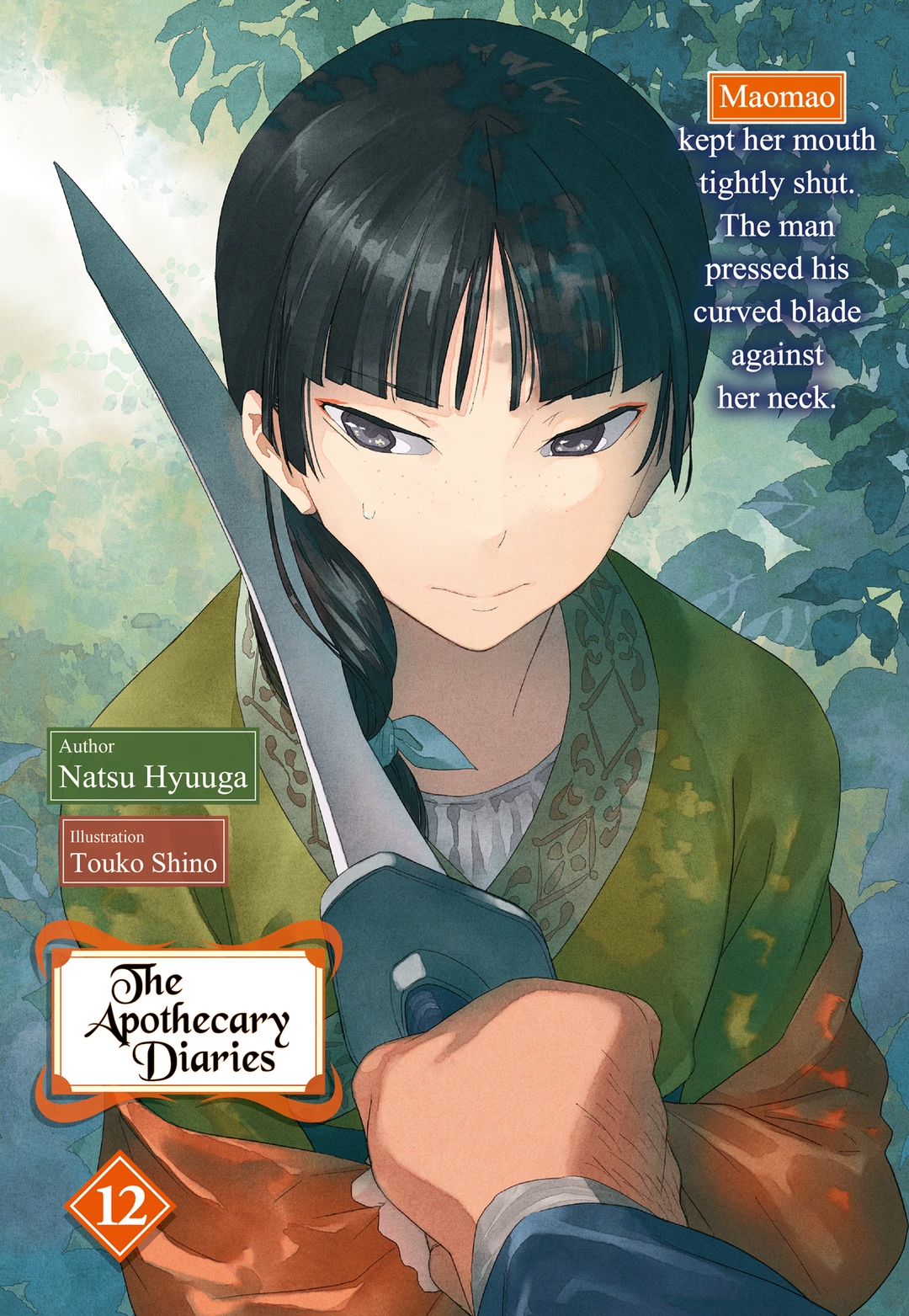

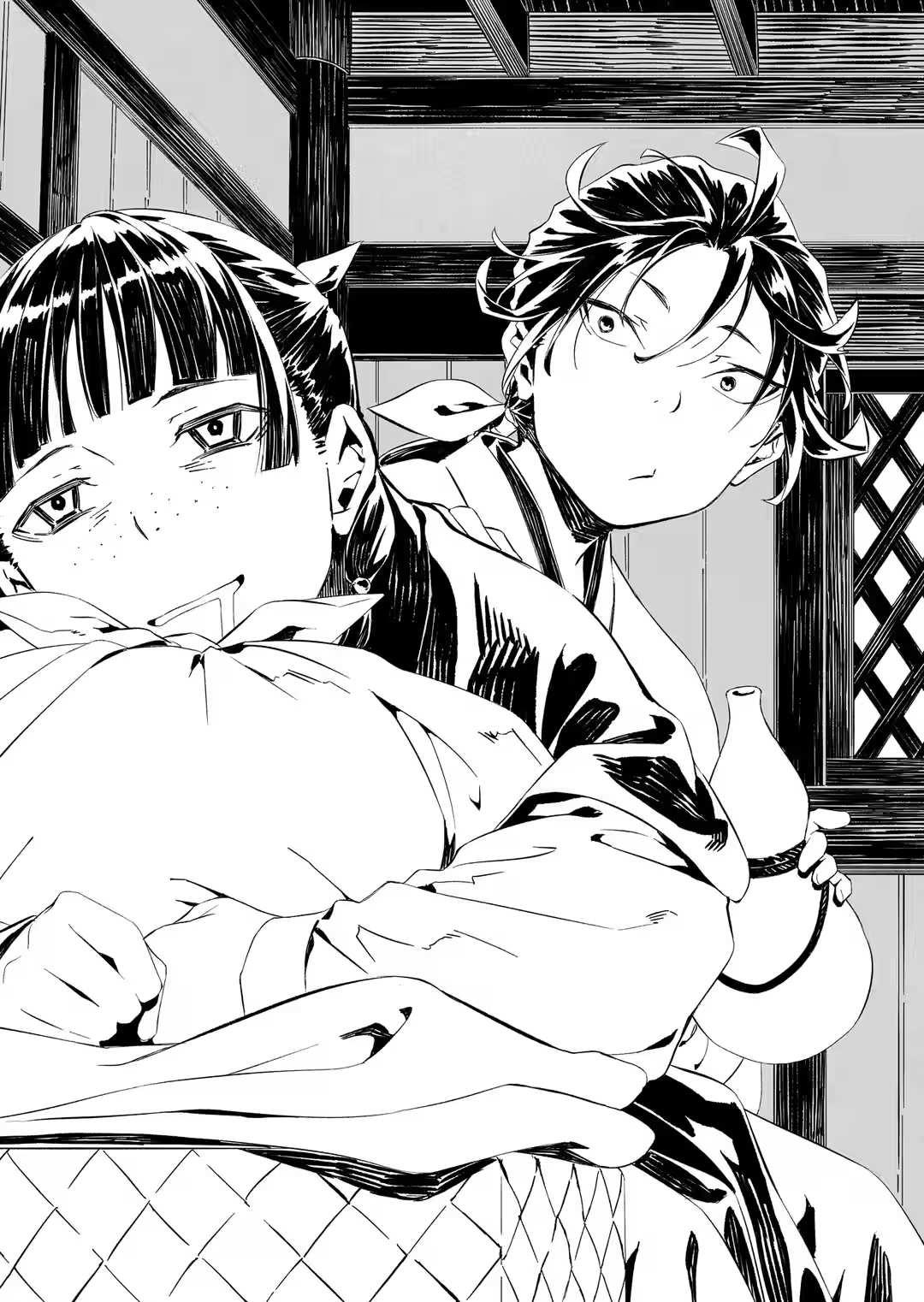

Maomao

Formerly an apothecary in the pleasure district. After a stint in the rear palace and then the imperial court, she now finds herself as an assistant to the physicians in the western capital. She’s downright obsessed with medicines and poisons, but she can’t get her hands on too many of them in her current location. She tries to mind her own position even as events carry her along. Twenty years old.

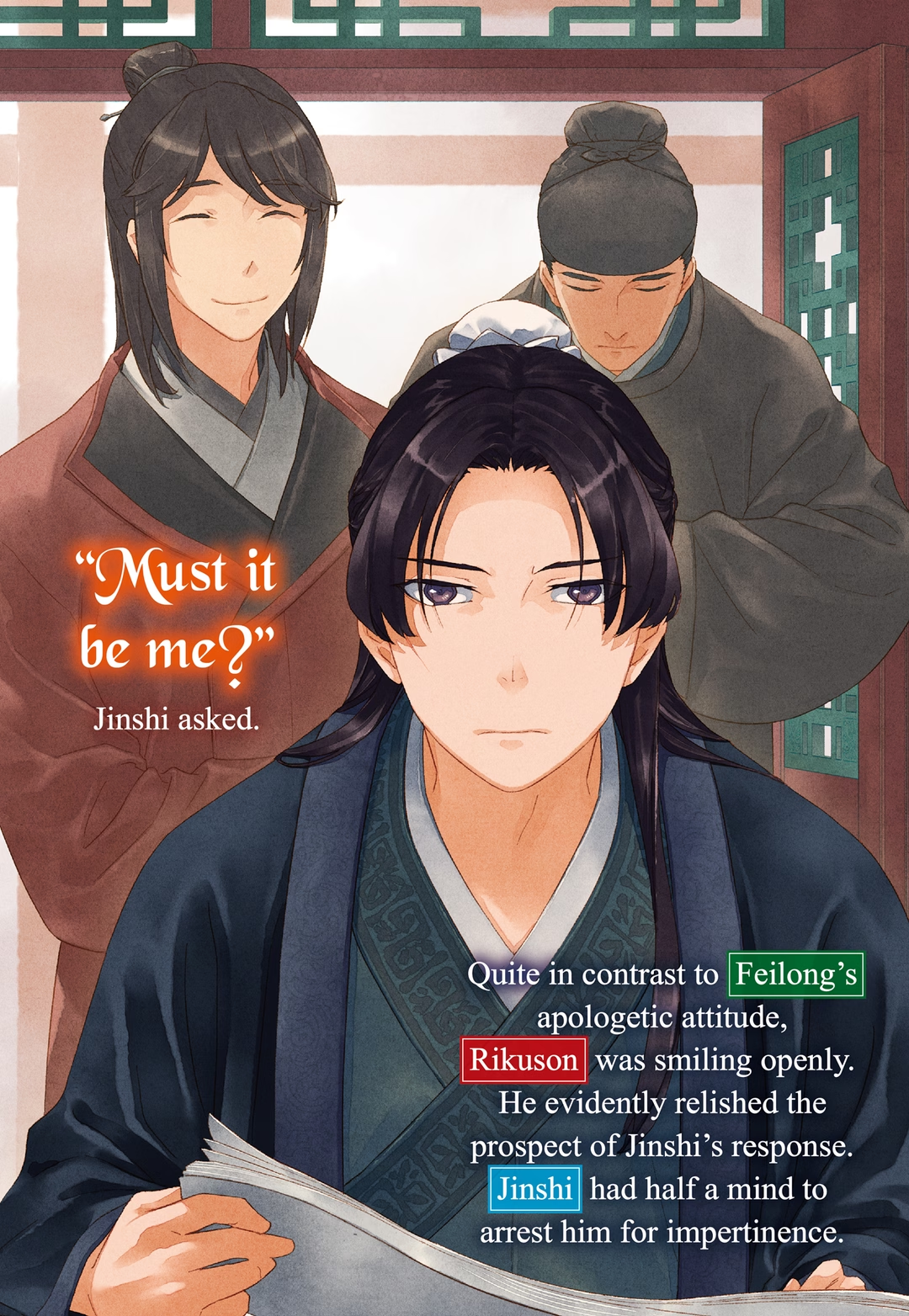

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. He’s a young man as beautiful as a celestial nymph. With Gyoku-ou dead, danger has gathered around him. Rikuson in particular foists a lot of work on him, and Jinshi is eager to get back at him someday. He doesn’t have a very high opinion of himself, but he has everything he would need to be an excellent politician in a peaceful world. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-one years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son and Jinshi’s attendant. He doesn’t feel pain as acutely as most people, which gives him far greater physical limits than most. Since coming to the western capital, he often works with his father, but because he so rarely sees his parents together, the experience can make him a little nervous. Guardian of the duck Jofu. Twenty-one years old.

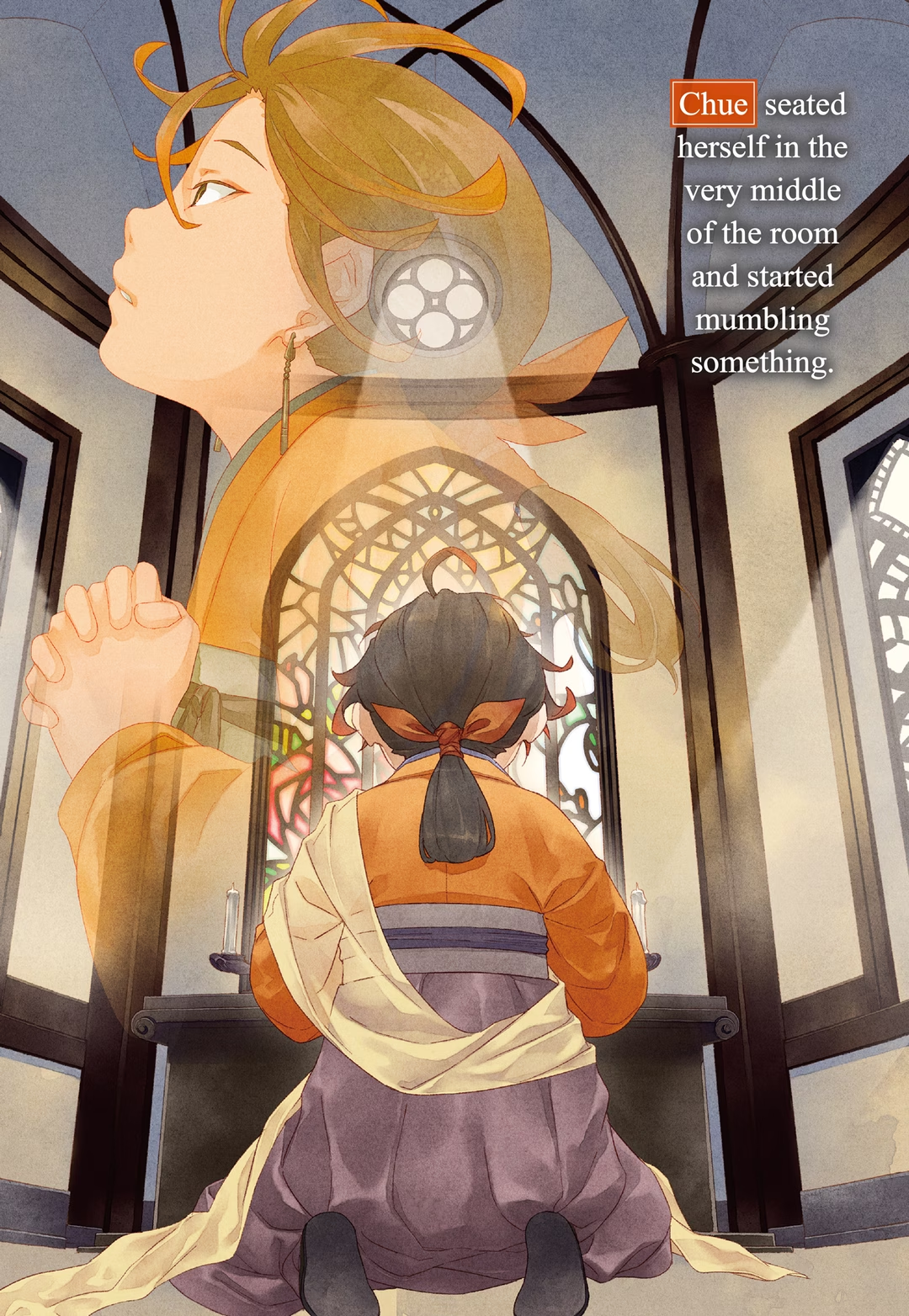

Chue

Wife of Gaoshun’s son Baryou. An enigma wrapped in a riddle wrapped in a clown, she mostly walks to the beat of her own drum. She’s Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting, but it seems she might serve another master.

Lihaku

A soldier. He accompanies Maomao to the western capital as her bodyguard. He’s a friendly guy, like a big mutt, but he spares no cruelty when something has to be done.

Lahan’s Brother

Older brother of Lakan’s adopted son, Lahan. He’s actually a very capable person, but because he doesn’t realize that, he always seems to get the short end of the stick. One gets the feeling that we’re on the cusp of learning his real name.

The Quack Doctor

A eunuch. He used to serve in the rear palace, but he’s not particularly skilled and has mostly gotten by on his luck. One thing he is good at is mellowing people around him. He’s the ultimate anti-La-clan weapon.

Gaoshun

Basen’s father, a well-built soldier, and Jinshi’s former minder. He accompanies Jinshi to the western capital as his guard, along with his wife Taomei, so they’re frequently together—something that seems to discomfit their two sons.

Lakan

Maomao’s biological father and Luomen’s nephew. This freak with a monocle adores Maomao, but everything seems to backfire on him. He’s either a zero or a hero at any given moment, but if you try to use him and blow it, there’s no telling what he might do.

Rikuson

Once Lakan’s aide, he now serves in the western capital. He has a photographic memory for people’s faces. In truth, he’s a survivor of the otherwise exterminated Yi clan and has secretly exacted revenge for his family. Completing his life’s work seems to have helped him relax, and he now spends his time tormenting the Emperor’s younger brother.

Gyokuen

Empress Gyokuyou’s father. Officially the leader of the western capital, but when his daughter ascended to the throne he moved to the royal capital. He left Gyoku-ou as acting governor of the western capital but sent Rikuson to act as his aide.

Gyoku-ou

Gyokuen’s eldest son and Empress Gyokuyou’s half-brother. With his father away, he led the western capital. He enjoyed tremendous support there, but all but ignored Jinshi. His tendency to let his xenophobia get mixed up in his politics led to his assassination.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting and former wet nurse. For Jinshi’s sake, she goes to the western capital despite her age.

Baryou

Gaoshun’s son and Basen’s older brother. He’s quick to develop a stomach ailment when confronted with another human being. Gets along well with the duck.

Vice Minister Lu

Second-in-command at the Board of Rites. He accompanies Jinshi to the western capital. Uncle of Maomao’s colleague Yao.

Jofu

A common white duck with a dark spot on her beak. She began life as an egg hatched by Lishu, but from the moment she saw Basen, they’ve been inseparable—so inseparable that she even came with him to the western capital. Jofu knows how to get along in the world and can find food anywhere she happens to be.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife and an exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. She’s from the western capital herself, but she has complicated feelings about her half-brother. Twenty-two years old.

Dahai

Gyokuen’s third son. He’s in charge of maritime transport in the western capital.

Shikyou

Gyoku-ou’s eldest son. Twenty-five years old.

Yinxing

Gyoku-ou’s eldest daughter. Twenty-four years old.

Feilong

Gyoku-ou’s second son. Something of a congenital bureaucrat. Twenty-three years old.

Hulan

Gyoku-ou’s third son. Very humble. Eighteen years old.

Xiaohong

Yinxing’s daughter; Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter. Her habit of eating her own hair led to an intestinal blockage, which Maomao and Tianyu resolved by performing surgery.

Gyokujun

Shikyou’s son and Gyoku-ou’s grandson. A real brat.

Prologue

How she wanted to be worth something.

How she wanted to be precious and irreplaceable to someone, the way she and her mother had been to her father.

Her mother had disappeared. She’d thought she had been showered with affection because she was a child—but that turned out to be an illusion, only a ploy to gain a moment’s tranquility.

She and her father had cherished her mother as an invaluable member of their family—when to her mother they had been only tools, interchangeable, replaceable.

Out of an excess of trust in her mother, her father had vanished. Probably dead somewhere he would never be found.

Without her father, who had treasured her like a pearl in his palm, she truly was worthless.

What should she do?

If she was worthless, then she was useless as well. She didn’t know what she should do.

So she went looking for her mother.

She could be useful. She would be useful.

That thought possessed her as she searched...

That thought, and a wish. The hope that there might be a place for someone as worthless as her.

Chapter 1: The Princeling of the Main House

It had been ten days since Gyoku-ou’s death. His demise had made the bigwigs very busy. Maomao’s job, however, had not changed much. She still made medicine, still examined the sick and the injured and gave that medicine to them.

Specializing does make some things easier, she thought. You just have to do one type of work.

There was a bit more of that work to do, but it was all of a familiar kind.

Once you were in a leadership position, that was no longer true. You had to keep an eye on the work of subordinates that you might not completely understand yourself. When problems arose, prompt decisions were expected—but you couldn’t give simplistic answers either. No wonder diligent officials began to break down physically and mentally.

All of which was to say, Jinshi was exhausted and weak, as usual, but he was getting his work done.

Here I thought he’d learned to step back just a little bit.

Even during their regular exams, Maomao (who accompanied the quack doctor) saw officials carting more paperwork into Jinshi’s office. She was getting pretty tired of it.

“I think that’s enough for today,” Gaoshun said, rebuffing a bureaucrat who had come with more papers. He looked tired too. He met Maomao’s eyes and dipped his head, expressionless. It made him look very somber—but the impression was undercut by the duck, Jofu, who stood beside him, tugging on his robe in hopes of getting some food.

I seem to remember him feeding a cat in the rear palace.

Apparently he now provided the same service for the duck.

“Is the Moon Prince really doing all right?” the quack doctor asked, watching the bureaucrat leave with his papers. He didn’t seem quite so tense with Gaoshun, maybe because they’d known each other since the rear palace.

“He’s certainly tired, but I’m hopeful that he’ll soon regain his energy.” Gaoshun looked directly at Maomao as he ushered her into the room.

If all went as usual, the quack doctor would be dismissed after a perfunctory examination, which would leave only Maomao.

“All right, young lady. I leave the rest in your hands!” The quack doctor departed and Maomao, basically trading off with him, went into Jinshi’s bedroom.

Yikes...

Jinshi lay spread-eagle on the bed. Apparently he had used up all his social graces during his interaction with the quack. He didn’t seem to have it in him to do anything else today—but a distinct sense of aggravation hovered around him.

“Rikuson,” he was muttering. “I’ll never forgive Rikuson...”

The breezy man must have foisted yet more work on Jinshi.

“You seem tired, sir.”

“I am tired.”

“I’ll make this quick, then. Let me see your wound.”

Jinshi didn’t say anything, but sat up looking like a pouting child. He sloughed off the top of his robe and undid the bandages.

There’s really no need for these anymore.

The bandages now were more about concealing the injury than helping it heal. New skin was growing over the scorched, charred old skin, forming a bright-red flower. It would have been beautiful if it hadn’t been inscribed on human flesh—especially not the flank of someone who was supposed to be very important.

They’ll also help keep his organs in if he ever gets stabbed in the side.

Maomao figured he didn’t really need the salve either, but applied it anyway just to keep things from drying out. Then she wrapped fresh bandages around the site. She’d told him repeatedly to do it himself, but he always wanted her to do it.

“There. All done.”

“Isn’t this bandage a little twisted?”

“No, sir, it’s not.”

“It is. I think you should take it off and redo it.”

So he was going to complain about her bandage wrapping technique, was he? When he did things like that, it usually meant there was something more he wanted to talk about.

Maomao sensed trouble coming. She tried to turn right around and leave the room, but Gaoshun gave her such a sad look that she went back.

“What seems to be the matter?” she asked.

“Funny you should ask,” Jinshi replied. It sounded like this story was going to be a long one. Maomao thought getting some rest would do more for his health, but maybe his mind was in worse shape than his body at the moment.

Many different people came to visit Jinshi; he had to deal with all of them in between going through his piles of paperwork. Of late, there had been particularly frequent visits from one fellow higher-up from the royal capital and Gyoku-ou’s half-siblings.

Of that higher-up, Vice Minister Lu, Maomao knew only a smidgen, such as that he was with the Board of Rites—and, to her surprise, he was her colleague Yao’s uncle. Chue had mentioned it to her in passing once.

So he’s the famous uncle.

This uncle was supposedly dead set on getting Yao married. Maomao thought the vice minister had given her a funny look once when they passed by each other—maybe he didn’t like that she was Yao’s colleague.

“That Vice Minister Lu does make a nuisance of himself, doesn’t he?” Maomao said. She’d taken a seat and was sipping at some grape wine—Jinshi’s examination was over and now she was just going to listen to him gripe. Surely no one would blame her for exacting a modest fee.

“He does! He keeps saying we should hurry and go back to the capital.”

“Yes, let’s do that. Right away,” Maomao said earnestly. By all rights, there was no reason for them to stay here.

“Do you think we could do that so soon?”

It was Jinshi who resolutely stayed stuck in the western capital. He couldn’t go home with everything still in disarray. He was the kind who felt he had to see things through to the bitter end, sometimes to his own detriment. That was probably why Rikuson was able to foist so much work on him.

People with a strong sense of responsibility soon grow sick at heart.

Maomao knew: just because you were a good person didn’t mean good things would happen to you.

“You would think there would be plenty of people in the western capital who could fill in for Master Gyoku-ou. And Master Gyokuen is still alive too. Master Gyoku-ou was his son—didn’t he say anything to you?”

Quite honestly, Maomao would have expected the man to be distraught when he learned that his son had died in his absence. But Gyokuen, it seemed, was pleading that his age made it impossible for him to return to the western capital.

Anyway, I’m not sure that his coming back here wouldn’t make things worse.

If Gyokuen returned to the western capital, it would be the Imperial capital that found itself in dire straits next. Empress Gyokuyou was now His Majesty’s official wife, but there were many who resented her bloodline. The new Crown Prince, her son, had inherited his mother’s red hair and green eyes. Maomao had met him when he was young and the pigment still light, and as he grew older the colors would get stronger. It wasn’t hard to imagine him finding trouble because of his un-Linese hair and eyes.

Then there were those who sneered at I-sei Province as a rural backwater. Consort Lihua had a son as well, born just a few months after the Crown Prince, and plenty of people would be willing to trade the one for the other if anything should happen.

Yep, yep. Politics is a pain in the neck.

Maomao munched on a sachima to go with her wine. A wheat-based treat distinguished by its fluffiness, it was a bit crude to serve as Jinshi’s snack, but more than luxurious enough when the food supply was still unstable.

“Sir Gyokuen would like Sir Gyoku-ou’s line to continue ruling here. He said as much in his letter. Though I might have preferred if he’d have been kind enough to give me a name.”

That would explain why none of Gyoku-ou’s half-brothers had been willing to take on the role. It was probably the same matter that was continually bringing them to visit Jinshi.

“Ahem. Master Gyokuen’s second and third sons are here a lot, aren’t they? Could we really not leave things to them? I assumed that was what you were talking about together.”

Maomao still hadn’t heard the second son’s name, but the third son was named Dahai. He was a well-built man in his mid-thirties, in charge of I-sei Province’s ports. He was, in fact, one of the visitors who had come to the annex that very day.

“Sir Dahai is here because he had a request of me.”

“Is it something annoying?”

Judging by Jinshi’s petulant look, it didn’t seem like anything good.

“He asked if I might consider transferring my base of operations.”

“Your base of operations, sir?” Maomao tilted her head, unsure what that meant.

“Oh, it’s nothing much. He merely suggested I move from the annex to the main house.”

“I see, sir.”

“Nothing much, right?”

“I believe that’s what you just said, Master Jinshi.”

One could walk from the annex to the main house in a trice, whistling a tune the entire time.

“The main house is right next door to the administrative office. Which would make it easier for them to add to your workload—is that what this is about?”

“One presumes.”

“And it would really raise some red flags if they tried to get you to go directly to the administrative office, so they’re moving you in stages, getting you used to the idea.”

“What am I, a feral cat they’ve adopted?” Jinshi looked spent. Maybe the exhaustion had just caused him to abandon any pretense. “If I’m too willing to move, I think the chance to go home will only get further away.” Funny thing to say, when he was the one who’d refused to leave.

It was a dilemma: on the one hand, they wanted Jinshi to go back to the central region; on the other, they wanted him to stay here in the western capital.

“Couldn’t you just refuse to move your ‘base,’ sir?”

“Believe me, I’d like to. But do you know what they say about the Emperor’s younger brother in the western capital these days?”

Maomao didn’t pull any punches. “They shout and swoon over your beauty, but at the same time, some conspiracy theorists hold that you masterminded the assassination of Master Gyoku-ou.”

“Mm.”

“Did you?”

“No!”

Figured.

Jinshi didn’t seem particularly adept at underhanded schemes like assassination. Yes, he had been more than willing to use his wiles to get his way in the rear palace when he had been posing as a eunuch, but recently he had become much more reserved. Maomao almost thought he was regressing.

“That leaves people claiming that I came to the western capital only in order to take it over.”

“Why come to this parched place when you could make lots more profit finagling things in the royal capital? You could buy up grain, then sell it at a high price and wring the money out of them.”

“You sound positively brutal.”

“It was Miss Chue’s idea.” Chue was something of a chatterbox, and she loved to use Maomao as an excuse to dodge work. “Anyway, if you go to the main house, won’t you only look even more like you’re bent on conquest?”

“Sir Gyoku-ou’s brothers and children are at the main house. The suggestion is that security would be better served by having everyone in one place, rather than splitting the guards between the main house and the annex.”

“You’re not afraid of someone trying to stab you to get revenge for their brother or father?”

“I like to think that wouldn’t happen,” Jinshi said after a moment. “Really, if anyone were feeling that emotional about it, I would have expected to see at least one assassin already.”

Commuting to the administrative office certainly would be much easier from the main house. Maomao wondered if she and the rest of Jinshi’s entourage would go with him.

Not that I’d really like to.

She could just picture a weird old fart hanging around, and it worried her. She was pretty sure the freak strategist was staying over there. Hence, Maomao was invested in maintaining the status quo.

“I can’t shake the sense that the move wouldn’t have many tangible benefits for you, Master Jinshi. Would it be a problem just to turn them down? You sound strangely unsure of what to do.”

“I understand what you’re saying, but I think I have to meet them in the middle, or we won’t get anywhere.”

There it is.

Jinshi was too direct, too honest, and sometimes it cost him. Maomao had a certain respect for that part of his personality, but it could be infuriating.

He should just put his foot down with them!

She was about to say so when Jinshi added, “Ahh, and the main house also has that thing.”

“What thing?” She cocked her head. She had no idea what this thing was.

“The greenhouse. Didn’t you see it last time we came?”

“A g-g-greenhouse?!” Maomao couldn’t stop her eyes from sparkling. She’d seen cactuses planted around the grounds when they had come last year—at which time they had stayed in the main house—but she hadn’t heard about any greenhouse.

“They said that if I moved to the main house, I could use the greenhouse to cultivate herbs.” Jinshi glanced at Maomao, then grinned openly. “But I gather you’d be just as happy to stay at the annex, Maomao?”

“Wh-Whatever do you mean, Master Jinshi? Never fear! I would certainly follow you to the main house!”

She pounded her chest for emphasis, so hard that she broke down coughing.

The move to the main house soon proceeded. The quack doctor was to come with them, not that it would change much of anything.

There was, however, at least one person who decided to stay behind. Lahan’s Brother surprised them. “A greenhouse is outside my field of expertise. It’s not like you’ll be far away. I think I’ll stay here,” he said. On his head was a duck, and beside him was a goat.

“Oh. I figured a pro farmer like you, Lahan’s Brother, would jump at the chance to grow things,” Maomao said.

“Who’s a ‘pro’?! Look, it’s not that I couldn’t do it. It’s just I have to focus on things that fall within the scope of my responsibilities. All I really do is imitate the things I’ve learned.”

Maomao thought it was awfully professional to know—and be clear about—what you could and couldn’t do, but she kept that to herself. It was certainly better than someone who pretended to possess knowledge they didn’t have.

“My specialty is grains,” Lahan’s Brother said. “You know a lot more about herbs than I do.”

“I suppose so.”

He said specialty! Maomao observed, but she pretended not to have heard. How nice of her.

“Anyway, like I said, I’ll still be close by. If anything comes up, call me.”

“Thank you, I will.” Maomao bowed to Lahan’s Brother. She suspected she would do quite a bit of calling on him, whether he encouraged her to or not.

The main house was substantially larger than the annex, and the medical office Maomao and the others were introduced to was bigger too.

This must be the place Dr. Li was entrusted with.

Of all the medical personnel sent from the capital city, Dr. Li was the most serious and most intimidating. And since their last meeting, Maomao had added most pessimistic to that catalog.

Looks like he’s still at the clinic in town.

The shelves here were neatly organized, making them easy to use, although most of the medicine had been taken to the clinic. There were also beds and chairs, neatly arranged. Maomao’s group hadn’t brought much equipment themselves, so it seemed like this wouldn’t take long.

“Shall I help you clean up your room, miss?” the quack asked, and for some reason his eyes were sparkling. He was holding an embroidered curtain.

“No, I can take care of myself. You can clean up your own room, please.”

She was not going to spend another night in a hideous, frill-laden chamber. She was even thinking that maybe next time they were running short on bandages, she could tear up that curtain for material.

A well-built soldier ambled up. “Hey, young lady?”

“Something the matter, Master Lihaku?”

“I need to use the toilet. You don’t mind if I leave you here?”

“I don’t think it should be a problem.”

Lihaku was more diligent than he might appear. There was another guard still standing outside the new medical office, so Maomao figured it should be fine.

“Sorry. I didn’t get a chance to relieve myself on my break.”

“No, it’s all right.”

The soldiers got breaks, yes, but a long shift could see them standing for half a day at a time. Bureaucrats occasionally sneered that it must be nice to have so much free time, but the work was demanding in its own way.

Lihaku said a few words to the other guard, then went to find the toilet. They didn’t know their way around this place, and it seemed like it might take him a few minutes. Maomao busied herself bringing in equipment and unloading the last of their cargo.

“There! All done.”

She was just giving a big stretch when she heard a shout from outside. “Yowch!” That was the quack doctor.

Maomao went out, wondering what had happened, to find the quack plopped down outside the office, rubbing his shin. There was also a boy holding a wooden training sword. The guard had been keeping an eye on Maomao, apparently to the exclusion of the quack doctor.

“I! Have judged you! You intruding insects!”

The boy must have been eight or nine years old. He was dressed in fine clothing and his hair was carefully done up. Those things would seem to mark him out as the scion of a good family, but that didn’t matter much right now.

Maomao crouched by the quack and looked at his shin. With one of those wooden training swords, even a young kid could cause a nasty bruise. She glared at the boy. “What do you think you’re doing?!”

He didn’t so much as flinch at her raised voice; in fact, he stepped forward in a show of strength. “I! Have delivered punishment! Upon the criminal!”

Who’s a criminal?

Maomao was just stalking toward the child to deliver him a good knuckle to the head when a panicked servingwoman rushed up and grabbed him. “Young master, you mustn’t!” She started bowing furiously to Maomao. “I’m sorry! I’m so very sorry!”

Maomao clenched her fist and stared daggers at the naughty child.

“Hey, let me go! I am going to slaughter the lot of them!” the kid shouted.

“No, young master, you can’t do this here! You can’t do this. I’m so sorry.” With her head still bowed, the servingwoman dragged the boy away.

Maomao had no choice but to let her fist relax. She was just glad the servant had made a prompt exit. Child or not, she really had been about to smack him one. No mercy for kids who went around whacking people with swords.

“My apologies!” the guard said, his face white. He would be blamed for letting the quack get injured after Lihaku had entrusted him with this job.

“I don’t need any more apologies. Help me get the master physician inside.”

Maomao touched the quack’s shin. “Owww! It hurts!” he cried, really rather overdramatically. The bone wasn’t broken, but he probably wouldn’t be walking anywhere for a few days.

Judging by that outfit and the servant looking after him...

It seemed safe to assume the boy was a relative of Gyokuen’s.

They’d barely gotten here, and already Maomao had a feeling that there was going to be nothing but trouble.

Maomao pressed a damp rag against the quack’s leg. Unfortunately, the abused shin had swollen substantially by the next day.

“It should be better in two or three days,” Maomao told him. In her opinion, the quack could just as well spend that time resting in his room. But he insisted on working, and she couldn’t very well chase him out of his own medical office.

I really don’t think it would be a big problem if he weren’t here, she thought, but she wasn’t cruel enough to say so out loud.

“Urrgh, it hurts...”

“I’m sorry, miss,” Lihaku said, bowing his head. The boy had seized on a brief moment when Lihaku wasn’t there. A single, fleeting lapse of attention by the guard. Maybe it had been in part because the interloper was just a child—but it remained that this boy had evaded the guard’s scrutiny and managed to harm the quack.

It’s because they’re really guarding me, isn’t it? Maomao thought. Outwardly, the soldiers were assigned to the physicians, and so in principle they were supposed to be protecting the quack doctor. But the remaining soldier had actually been watching Maomao.

The soldiers didn’t specifically give Maomao any special treatment—probably a touch of consideration on Jinshi’s part. But there seemed to be a tacit understanding of who she truly was.

Much as I hate for people to think of me as that freak’s daughter. Therefore, as long as the guards didn’t bring it up, Maomao was happy to act the part of an ordinary medical assistant. That was all she was, and nothing more.

And yet, she didn’t want the quack doctor being put in danger because of that. It seemed the guard yesterday wasn’t yet used to protecting VIPs. That was one of the reasons Lihaku had seemed so apologetic about needing to go to the bathroom. He was the one permanently assigned to the medical office, while the other guards came in on rotation—and there were a lot of new faces these days.

“Knock knoooock! Incoming!” Chue entered, pretending to knock on the medical office door. “Poor Mister Quack! I’ve come to visit you at your sickbed!” She was holding some grapes, a common fruit in the western capital.

“Oh, Miss Chue, that’s so kind of you.”

Whoa, wait, hold on there. Did he really not care that she called him “quack” like it was nothing?

“Miss Maomao! Would you like to know which no-goodnik it was that attacked Mister Quack yesterday?”

“Who? If it was someone from this estate, I assume it had to be one of Master Gyokuen’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren.”

“Bingo! It was Master Gyoku-ou’s oldest son’s son.”

I might have guessed.

Maomao had heard that Gyoku-ou was nearly old enough to be Empress Gyokuyou’s father himself, so it wasn’t that surprising if he had a grandson the age of the boy who had attacked the quack.

“They say his name is Gyokujun!” Chue sketched a character in the air with her finger. Apparently the family had a thing for naming their children after birds: as the -ou of Gyoku-ou meant “nightingale,” jun meant “falcon.” Chue went on, “Also, young Gyokujun wishes to apologize and is standing outside the medical office with his mother right now. What would you like to do?”

“You could have led with that.”

Maomao looked at the quack doctor. Rather than actually say yes, he smiled. “He’s still just a child, after all. If he knows he did wrong and wants to apologize, then it’s water under the bridge!”

Gee. Nice guy...

Maomao wasn’t so sure, but the quack doctor was the victim here, so they would do as he said.

“Come in,” Maomao said as she opened the office door, although she didn’t look very happy about it.

Gyokujun was standing there, not looking any more pleased than Maomao. A woman stood next to him, a timid look on her face. “I can’t apologize enough for what my son did,” she said, bowing deeply.

She pressed on the back of her brat’s head, trying to make him bow too, but he said, “S-Stoppit! I’m not gonna say sorry!”

“You apologize this instant!”

“Nuh-uh! No way!” Gyokujun whined.

Now his mother was angry. She raised her hand high, and almost at the same moment they heard the slap, Gyokujun went crumpling to the ground.

An openhanded slap wouldn’t leave a lasting mark, but it sure sounded dramatic. Maomao doubted the boy was actually hurt, but he was still physically small enough that his body probably couldn’t absorb the blow.

“I said, apologize!” His mother looked like she might burst into tears. Maybe the stress of child-rearing was bubbling to the surface.

Gyokujun sniffled and pinched his lips together, trying not to cry. “I... I’m very sorry,” he said, although he obviously didn’t mean it. He showed every sign that he would do it again if he got the chance, but the quack doctor was watching his mother anxiously.

“That’s enough, please, it’s really fine. Please, don’t bow to me.”

Gyokujun’s mother, however, only bowed again, insisting, “I am so, so sorry!” Gyokujun was already out of his bow and scowling at the quack.

Signs of a lesson learned: zilch, Maomao observed.

When mother and son had left, Maomao was hit by a wave of exhaustion.

“Do you think he’s all right? That was some slap she gave him,” the quack said, much concerned about a child who had shown no repentance.

“Aw, every parent gives their child a good whack now and then, buddy. Most men can remember doing sword drills until they went unconscious from shouting,” said Lihaku.

“Exactly. It was nothing much. He’s just lucky she didn’t use a closed fist,” Chue added.

“An open palm isn’t such a big deal. Although it’s trouble if there’s an injury somewhere it can’t be seen. The solar plexus is a good compromise—it hurts, but it doesn’t show,” offered Maomao.

“What kinds of homes were you three raised in?” the quack asked, drawing back a little. He was a eunuch, but he originally came from a good family, and had probably never suffered “the punishment of the iron fist” at the hands of his parents.

Still, it wasn’t that Maomao didn’t understand the quack’s concern. “The boy’s mother did seem sort of frantic. I guess a person could get in a lot of trouble for harming the Imperial younger brother’s personal physician.”

As much trouble as one might get in, though, the mother seemed worried about something more.

“Shall Miss Chue explain that one?” Chue said, striking a pose with her finger pointed toward the ceiling.

“Do you know? Was there a reason?” the quack said, immediately curious. Lihaku looked like he wanted to know too. Maomao had to admit that she was curious, but she affected disinterest, as if she would just listen in if everyone else wanted to know.

“Master Gyoku-ou has passed away, and the western capital is all agog about who’s going to be the next leader here. Every name you can think of has been suggested, from Master Gyokuen’s other sons to Mister Rikuson from the royal capital, to even the Moon Prince himself!”

“Yes, I’ve heard all that,” Maomao said.

Mostly from a complaining Jinshi.

“The one person whose hat hasn’t been thrown into the ring is the one person you would expect to be first in line—did you know that?”

Lihaku said slowly, “Normally, you would expect Master Gyoku-ou’s son to succeed him. That’s how it works, even in the Imperial family, right?”

He was right, indeed.

“Precisely. But! That son has been kept completely out of politics throughout his life, on the grounds that he wouldn’t need to be involved until later. He’s been ruled out on the basis of ignorance, or so the story goes. But doesn’t that seem strange?”

“Yes, so it does. You would think he’d have studied a little more,” said the quack doctor.

“With what I’ve said so far, I would expect Miss Maomao at least to be able to see where this is going. In reality, Master Gyoku-ou’s eldest son is—da-dada-daaaah!—a lazy, profligate layabout!” Chue waved her hands enthusiastically and produced a shower of confetti. “He did get the education you’d expect of an intended successor, but then he threw it all away.”

“‘Threw it all away’ how?”

“He had...let’s call it a late rebellious phase. By that time, though, he was already married to the woman his parents had chosen for him, and even had a child. But he stole a horse and ran off! You’d think he was some little kid!”

Maomao thought about how uncomfortable the mother had seemed earlier.

“So his own relatives aren’t treating him as the heir apparent, and folks are even suggesting people unrelated by blood to be the next leader. He must be pretty bad,” Lihaku said, crossing his arms.

“Oh, very bad! This eldest son is some twenty-five years old. He abandoned his home several years ago, leaving his wife and child, and...well, let’s just say he’s been up to a lot.”

That might explain the mother’s mean streak, Maomao admitted. No doubt her relatives blamed her for “not keeping a close enough eye on her husband.”

“Like what?” Maomao asked.

“Master Gyokuen’s second-to-last son, his seventh, is twenty-five too, and the two of them don’t get along. They fight all the time. Once, there was a whole thing when they decided on a duel with real edged weapons. Both of them are so good that no one could stop them. Oh, it was terrible!”

Hmm, hmm!

“Then he started brewing his own liquor, ‘borrowing’ bottles from a nearby distillery, filling them with his moonshine and selling them. That tanked the distillery’s reputation. It’s worth noting that the place was run by Gyokuen’s third daughter.”

Hmm?

“Also, Miss Maomao, you remember how we were attacked by bandits when we went to that farming village? Apparently he was also connected with that incident.”

Hmmmm?!

Maomao held up a hand for Chue to stop.

“What seems to be the matter, Miss Maomao?”

“I’m amazed Master Gyoku-ou didn’t disown him.”

“Being the eldest son probably helped protect him a little. And Master Gyoku-ou has some odd preoccupations, so he never gave his second or third sons any education in politics at all. Anyway, the eldest son was a well-behaved and capable young man until he went off the deep end, so maybe Master Gyoku-ou thought he would come back around eventually. The son’s a powerful guy and a leader—I heard that when he was attacked by the boss of a bandit gang known all around I-sei Province, he went to get the guy back himself.”

Chue nibbled on a fried dough twist she’d gotten somewhere. She’d distributed them to the quack doctor and Lihaku as well, and they were also eating.

Getting revenge on a bandit, huh? Very much the sort of “hero” image that Gyoku-ou had so prized.

“As for Master Gyoku-ou’s younger brothers, they’re all too busy with business to lead the western capital. But we absolutely can’t leave the job to his eldest son. Mister Rikuson and the Moon Prince were probably put forward to buy some time. Master Gyoku-ou’s second and third sons are both clever guys. We can gain enough time for them to learn about politics. I think plans are being laid for the eldest son to be disinherited before then. With Master Gyoku-ou gone, he’s lost his protection.”

“You sure know a lot, Miss Chue,” the quack doctor said admiringly—although these seemed like things she probably wasn’t supposed to know.

These were Gyokuen’s children: toughness and stubbornness were guaranteed. They were using the Emperor’s younger brother in order to buy themselves time.

“That does explain why that boy’s mother looked so worried,” Maomao said. Marrying a family’s eldest son didn’t mean much if that son got himself kicked out of the family line. And if her own son went on to injure the Imperial younger brother’s physician, well, that would be enough to make the blood run cold.

“In light of all that, it seems likely that the second or third son will be assigned to serve under the Moon Prince for a while, and the other one will be assigned to Mister Rikuson. If one of them proves to be an especially quick study, that means we’ll be able to go back to the central region all the sooner. And speaking of going back, Miss Chue had better get back to work.”

She stood up as if to signal that the conversation was over; she was done with her snack, anyway.

Maomao raised her hand. “Miss Chue? Question.”

“Yes, Miss Maomao? What is it?”

Maomao recalled that they were now stationed in the main house. “Does this worthless layabout of a son ever come to the main house?”

“Not very often, but I gather he stops by to see family every once in a while. It’s certainly possible you might bump into him.” Chue gave a broad wink.

Please... Don’t jinx it.

Maomao foresaw many travails in her future. She did the best thing she could do: she shook her head and tried to forget about it.

Chapter 2: The Greenhouse and the Chapel

When Maomao had tidied up her new room, she went to see the rumored greenhouse.

“Oh! My! Gosh!” she exclaimed, her eyes shining, as she observed the facility. It was a building of brick and wood, parts of the ceiling and walls made of transparent glass so sunlight could get in. Inside, they were growing exotic succulents and even cucumbers. Cucumbers were a vegetable you could pluck out of the fields in summer, an easy way to get some water, but in the western capital they were treated as rare and valuable goods.

“It’s difficult to grow cucumbers in the west, so they’re considered a sign of wealth. For that reason, we often serve fresh cucumbers when we have visitors from farther west. They also happen to be a favorite of Master Gyokuen; he likes to eat them sandwiched between pieces of thin-sliced bread.”

This explanation was being proffered by the gardener who ran the greenhouse. He’d even kindly prepared some bread and butter for a taster, and looked ready to whip up a little something for them to try right there.

However...

“Miss Maomao, you’re starting to dance!”

“Yeah, miss, take it easy. There’s people watching!”

Chue and Lihaku looked at her, vaguely concerned.

“Hey, I know that!” Maomao said, even as she whipped a pair of scissors out from amidst the folds of her robes. “Cuuuucumbers!” she sang out. “Cucumber leeeeaves! Cucumber steeeems!”

The moment she took one of the vegetables by the stem, however, the gardener had a hand firmly on her shoulder. “Forgive me, but what, may I ask, do you think you’re doing?” A vein pulsed on his forehead.

“I just thought, cucumber season is almost over. You won’t need these much longer.”

It was only going to get colder. Greenhouse or no greenhouse, Maomao suspected, it would soon be impossible to grow cucumbers.

“They can still be harvested.” The gardener’s grip got firmer.

“The leaves and stems, to say nothing of the fruit itself, of course, are all potential medicinal ingredients, but they’ll be useless if they wither first. If I don’t take them now, when will I have the chance?” Maomao said, meeting the gardener’s gaze and refusing to back down. They found themselves locked in a staring contest.

“These are for food,” the gardener said, his eyes bulging.

“The western capital is facing an unprecedented crisis. Medicine is in desperately short supply. Don’t you think you should help?”

By now, they were using substitutes for many medicines. This was no time to be growing vegetables just to indulge someone’s culinary inclinations.

“I’m given to understand that you’ve received permission to use the greenhouse. I have to wonder, however, if they also told you that you could just do whatever you wanted with the plants that are already here.”

“These cucumbers are on their way out, and they’ll have hardly any nutritional value, anyway. Don’t you think the obvious thing would be to use them as medicinal ingredients?”

Maomao and the gardener continued their standoff.

After a brief stalemate, Chue arrived with the gardener’s superior. The boss gave the gardener the rundown, but the man refused to capitulate.

“I don’t think things here are quite what they told the Moon Prince,” Chue observed.

“I think this boss is the kind who avoids telling his people any bad news in order to put on a good front for the dignitaries from out of town,” replied the surprisingly perceptive Lihaku, capably reading the situation.

He was exactly right, and the gardener was the unfortunate victim. Here was a man who’d even had bread made so that they could try the products of his beloved greenhouse. Maomao had to admit she felt a little bad for him, but this wasn’t what they had been told.

Why does he think I came to the main house?

In the end, it was decided that Maomao would use only one-third of the greenhouse. The soon-to-be-out-of-season cucumbers would go to her, however. With many an aggrieved look at Maomao, the gardener, on the edge of tears, set about making an Authorized Personnel Only sign to keep her out of his succulents.

“What kind of medicine can you make with these?” Lihaku asked as he helped Maomao gather the cucumbers and harvest their leaves and stems.

“They’re very common in antipyretics. They’re also effective against food poisoning and encourage urination. They can be used to induce vomiting as well.”

“Wait, when would you need to induce vomiting?”

“When you’ve taken more than the necessary amount of poison, for example.”

“That’s not a thing people normally do!” Lihaku smiled genially even as he delivered the sharp quip. It was one of his virtues that he wasn’t quick to anger, but if Maomao could have anything she wanted, she might have wished for him to have the particular quickness of wit that Lahan’s Brother possessed.

She and the others collected the vegetables, the leaves, the stems, and even the vines. Then they pulled the naked cucumber plants up by the roots, leaving only empty earth behind. The gardener looked at Maomao as if she had killed his parents, but she paid him no mind.

Somewhere along the line the duck, a perfectly ordinary duck like you might see anywhere, arrived and started pecking at the insects that emerged from the freshly turned earth.

“What are you going to plant now that you’ve got a plot to work with?” Lihaku asked.

“Good question. I was thinking maybe I’d start by just planting every kind of seed I have on hand. I don’t know what’s going to grow in the greenhouse, so maybe I can start by seeing what takes.”

“Every kind of seed? Is there space for that?”

Maomao paused. “Maybe if we tear up that other cucumber plot too.”

It looked like sparks would fly once more between her and the gardener. Two people who refuse to give an inch are always far from the path of peace.

“Miss Maomao, Miss Maomao!”

“What’s the matter, Miss Chue?”

Chue seemed to have spotted something. She was pressed against the glass wall and peering outside.

“There’s a chapel over there! Mind if I go take a look?”

“A chapel?”

Chue pointed, and Maomao saw a building in the distinctive western style. There were plenty of similar ones dotting the western capital; most of them seemed to have religious functions.

It’s not quite like the one we were in before, though.

There had been a chapel-like building on their visit last year, but this was different. Curious, Maomao followed Chue over.

She’d heard that chapels were something like shrines. It certainly has the same somber atmosphere, she thought as they entered. It was a simple hexagonal space, a single room. However, light poured through the windows, which were adorned with pictures made of colored glass, dappling the otherwise plain floor with beautiful colors. It did indeed leave Maomao with an indescribable feeling of wonder.

Chue seated herself in the very middle of the room and started mumbling something. Maomao sat beside her. She didn’t really know what was going on, but stayed quiet until Chue was done talking. Lihaku waited outside; the chapel would be a little crowded with all three of them in there.

“Phew...” After a moment, Chue looked up. Coming from her, this was all a little bit odd.

“Miss Chue, what were you doing there?” Maomao asked.

“I was using an old language from another country to ask, ‘O Lord, do You see us?’”

“I don’t get it. What’s that mean?”

“It’s a line from the holy text of a foreign religion. You know, there are lots of very pious believers in the western capital. If you can work in a line of scripture here or there while you’re chatting, it can do wonders for your business!”

Chue took some writing utensils from the folds of her robe and jotted something down. “Here, Miss Maomao. It looks like you’re going to be living here for the foreseeable future, so you might as well learn it.” On the paper, she had written the words she had been speaking, spelled out phonetically so that Maomao could read them.

“I really don’t think I need to.” Maomao couldn’t have cared less about this subject, and had no interest in learning these words.

“No, no. I think you should!” Chue didn’t back down; she gripped Maomao’s shoulders and looked her squarely in the eye. She wasn’t leaving the apothecary with much choice. “Here we go! One! Two! O Lord, are You there, Lord?”

“O L— Lard, arr you therre, Lard?”

“Hmm. You sound like a babbling baby.” Maomao thought she had said the words just the way Chue had written them, but apparently there was something wrong with her pronunciation. “Let’s try again!”

“Let’s not and say we did.”

“Come on! This is the perfect opportunity.” Chue was proving unusually stubborn.

When they’d repeated the phrase several times and Maomao’s diction had begun to improve, Chue finally let her go. While she was at it, she taught Maomao the proper gesture of prayer, although Maomao doubted how much good it would do her.

As they came out of the chapel, they caught Lihaku yawning. Bored, probably.

“I’m gonna give you a pop quiz on this the next time we come by,” Chue warned Maomao.

“Yeah, okay,” Maomao said. As far as she was concerned, there wasn’t going to be a next time. “Let’s go back for now and get some food, Miss Chue.” She was confident the subject of food would divert the ever-famished attendant. Chue liked to take her meals with Maomao in order to avoid her mother-in-law, and Maomao anticipated prompt agreement.

“Good idea. Mister Quack must be starving too. By the way, how is he attending to his bathroom needs?” Chue showed no shame in the question.

“I take him to the toilet whenever I’m there,” said Lihaku, who could carry the quack around in his arms.

“He should be fine. I left him with a bedpan. It’s for female use, so I think it should work for him,” Maomao replied, as unconcerned as Chue. The quack was a eunuch, so he lacked the distinguishing feature of most men.

“Gee, I suddenly feel bad for the old guy. Let’s get back, huh?” Lihaku said, picking up his pace. He really did look unusually concerned.

Chapter 3: Gyoku-ou’s Children

When Maomao and the others got back to the medical office, they heard voices talking inside.

Is there a patient here? Maomao wondered. If the quack doctor was examining them, then she’d better get in there and trade off with him, quick. She opened the door.

“Hello, we’re back,” she said.

“Oh, hullo, young lady! Welcome back, everyone.”

The doctor was chatting with a young man Maomao didn’t recognize.

Who’s this?

He was probably younger than Maomao, a smallish man with kind eyes. His face was attractive enough, but perhaps didn’t look like much in the western capital, where there were brawny men to spare.

“Is this a patient?” Maomao asked.

“Oh, no. He’s a visitor. He came to say a polite hello,” the quack answered, his injured leg resting on a chair.

“You must pardon the intrusion,” the small-built young man said, giving her a carefree smile. “And you must pardon me for failing to introduce myself sooner. My name is You Hulan, and I’ll be serving the Moon Prince.”

“Oh, I see. I’m Maomao.” She met his polite bow with a deep one of her own.

“You,” huh? That was a name she seemed to be hearing a lot lately.

“This young man, you see, he’s supposed to serve the Moon Prince,” the quack offered. “He’s Master Gyoku-ou’s son.”

“Indeed. I’m still quite young; I beg your indulgence with me.”

Gyoku-ou’s son? Maomao tilted her head, perplexed. He seemed like the polar opposite of his father. Where was the resemblance?

Chue spared the boy only a brief dip of her head. Maybe she knew him already. “Master Gyoku-ou’s honored son, you say?” she said.

“Yes, ma’am, his third and youngest. I never dreamed I would have the honor of serving the Moon Prince.” Hulan was beaming.

Maomao had heard that Jinshi and Rikuson would each have one of Gyoku-ou’s sons assigned to help them—one would get the second son, the other the third. This young man, however, was not quite what she’d been expecting, and she was a little taken aback.

I just figured he would be more...full of himself.

This was the son of the man who had attempted to use Jinshi like a pawn? At a glance, anyway, he looked perfectly humble. He was sipping tea with the quack doctor—a eunuch—and didn’t hesitate to act polite to Maomao. He was nothing like she would have imagined. Certainly not the raging tempest of a man that might have been suggested by the name Hulan, which meant “tiger and wolf.”

“My next-eldest brother is serving Master Rikuson. I do hope you’ll look kindly upon each of us.”

If the second son had been assigned to Rikuson, and the third to Jinshi, perhaps it was in deference to their respective ages.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the second son is older than Jinshi. And when you had to order someone around, it made things easier if they were younger than you.

“I’ve come for more than just greetings today. I’m also here to offer my apologies,” Hulan said.

“What for?”

“My nephew injured the master physician, and I am deeply sorry for that. He’s still young, and as my father’s first grandchild he’s been rather spoiled. I will accept any punishment on his behalf, only please look generously upon my nephew.”

Who the heck is this guy?

He sure didn’t seem like Gyoku-ou’s child. He had the deferential attitude of someone who had already spent decades as a buffer between a superior and their subordinates.

“Hulan was kind enough to bring snacks and wine. And it’s so hard to get snacks these days! I can’t thank him enough,” the quack doctor said. He held up a basket of steamed buns. There were two bottles of wine beside it.

Well, now!

“This is special grape wine from the western capital, although I fear I don’t know whether it will be to your taste. In hopes of finding something you’d enjoy, I brought two varieties—one more alcoholic and one less.”

What an excellent choice of gift. Maomao felt an urge to cling to the wine bottles, but resisted.

“Now, then. If you’ll excuse me, I must get back to work,” Hulan said.

“Oh, please, stay a moment longer, Hulan. You’re still young, and youth should take its time to relax,” said the quack, who by now had adopted an air of total informality with the young man.

“I’m afraid I couldn’t. My uncles and aunts told me to make sure I studied diligently at the foot of the Moon Prince. I’ll work as hard as I can to catch up to everyone else, and meanwhile, I do hope you’ll look favorably on me.”

Hulan gave another elaborate bow and left the office.

“I have to say, I don’t see any wolf in him,” Maomao remarked. The tiger and the wolf of Hulan’s name suggested someone greedy and violent; it was a strong name, yes, but not a very good one.

“Yeah. He seems more like a loyal mutt,” Lihaku added, and Maomao agreed with him completely.

After Hulan had left, the quack told them about Gyoku-ou’s children.

“They say Master Gyoku-ou had four children. Young Hulan is the youngest of them.”

Maomao and the others lost no time turning Hulan’s gift of steamed buns into their snack.

Got to make sure there’s nothing in them, Maomao thought, her old habit of checking food for poison rearing its head. They were filled with meat, and she was perfectly happy to make them her lunch. She was only sorry she couldn’t have the wine with them—but she was on duty, after all.

“The oldest is twenty-five, and then the rest of the children were born in successive years—except Hulan; he’s a little younger. About eighteen. Isn’t that right, Miss Chue?” the quack asked as he poured tea into some cups.

“Oh, yes, very right. Master Gyoku-ou’s children go: eldest son, eldest daughter, second son, and then the third son bringing up the rear at eighteen years old.”

Chue was putting out some soup she’d reheated. Maomao took a bowl and passed it to Lihaku, who stood slightly apart from the quack doctor. The quack prepared the tea without getting up, while Lihaku was as vigilant as ever. After spending more than six months in each other’s company, each knew their role.

“That’s an odd collection. Do they perchance have different mothers?” Maomao asked, sitting in a chair and breaking open a bun. The filling spilled out, meat and mushrooms and bamboo shoots.

“Not at all. Unlike his father, Master Gyoku-ou only had one wife.”

“Huh! That is quite different from Master Gyokuen,” the quack said, sounding surprised. It wasn’t unusual for men in Li to have more than one wife, but eleven was enough to make Gyokuen the subject of talk. Even the Emperor only had enough wives to count on one hand. Yes, there were two thousand consorts and ladies in the rear palace, but between considerations of family background and resources, they weren’t necessarily all people His Majesty could easily take to bed.

Lihaku spoke up. “You know, I heard a rumor. About Master Gyoku-ou’s wife.” His ears and mouth were participating in the conversation, but his eyes continued to scan the area outside the medical office.

“What kind of rumor?” Maomao, having carefully studied the bun, now popped it into her mouth. The seasonings were characteristic of the central region, and she was surprised to realize it made her a little bit homesick.

“I heard she’s always had good business sense, that she used to be a real go-getter. After the birth of their second son, she boarded a foreign trading vessel for a business venture, except it was involved in a shipwreck. Unluckily for her, things weren’t very good in the country where she wound up, and she had to stay there for several years.”

“That’s quite a story. I’d expect to see more of someone like that, though,” said Maomao. So far, she hadn’t seen Gyoku-ou’s wife even once. She’d assumed that meant she was just a chaste, retiring woman who spent her time supporting her husband, but it seemed strange that Maomao hadn’t so much as seen her face since Gyoku-ou’s death.

Chue picked up the story. “She came back years later, but rumor has it she wasn’t the same woman. She’d become someone who supported her husband from the shadows, where nobody would see her. I’m sure a lot happened to her in those farmlands.” When Maomao looked closely, she saw Chue’s plate, and hers only, had one extra bun on it. She would have to watch out for her.

“Do you think that played into why Master Gyoku-ou hated foreigners so much?” Maomao asked.

“Who can say? We’ll sure never know now.” Chue didn’t sound very interested, happily munching on a steamed bun instead.

Lihaku had returned to his food as well, apparently having shared everything he knew about the wife. Maomao didn’t have any follow-up questions to speak of either.

“You know, wasn’t that girl you examined Master Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter?” the quack asked.

“That’s right. His oldest daughter’s daughter.”

The girl had developed an intestinal blockage because of her habit of eating her own hair. Tianyu had performed the surgery, but Maomao had attended to her care after that. The stitches had already come out cleanly.

“It must have hurt so much, having her stomach cut open. How’s the wound? Is it all right now?” the quack asked, his brow furrowed in genuine concern.

You can hardly even tell it was there, Maomao thought. She hated to admit it, but Tianyu was an excellent surgeon. Maybe you had to be a little crazy to be so good; heaven, the saying went, did not give two gifts to one person.

“Yes, it’s much better,” Maomao said. “I visit her periodically to check on the progress of the scar, but that’s all. In fact, I’m going tomorrow.”

Treatment was coming along nicely. She wished a certain abdomen-scorching noble would be such a good patient.

“Oh? That’s good, that’s good. I’m glad to hear it.” The quack looked relieved; Maomao, though, thought he should worry more about his own leg.

Chapter 4: The Sheltered Wife

The next day, Maomao went to see Gyoku-ou’s granddaughter, just as she’d told the quack doctor she would.

What was her name again?

Maomao, as we’ve established, was not excellent at remembering people’s names. But she got by okay, so it was fine—right?

As so often, Lihaku and Chue were with her. And one more person...

“Oh, please, don’t mind me.”

For some reason Gyoku-ou’s third son, Hulan, was there too.

“I just thought I might tag along. I like to see my elder sister and my niece once in a while.”

Gee, and here I thought your honor was serving the Moon Prince.

“Are you sure you don’t need to work?” she asked, careful not to let her skepticism show on her face.

“You needn’t worry—this doubles as work. I thought it would be a good chance to ask for some details about the job my father was doing.”

“You’re going to have a chat with your sister?” That didn’t sound like work to Maomao. She gave him a quizzical look.

“No, my mother. She lives with my sister; she says there’s too much commotion at the main house for her.”

Ah, the much-discussed mother.

So she retired from the “main stage,” but was still supporting Gyoku-ou in the background. It would make sense, then, to ask her about his business.

At the entryway to the house, they were greeted by the young patient and her mother, as well as a woman somewhere past forty.

Is that Hulan’s mother? Maomao wondered. She’d visited this house several times, but this was the first she’d seen of her. Maybe she was there waiting, not for Maomao and her band, but for Hulan. I think I’ll call her Hu’s Mom for the time being.

She didn’t know if Hulan was even going to introduce them, but if he did, knowing how rarely she was likely to encounter this woman left Maomao without much desire to remember her name. In the same vein, she dubbed Hulan’s older sister “Hu’s Sis.” She did indeed resemble Hu’s Mom, as one might expect of a mother and daughter, but Hu’s Mom possessed a beauty of a kind that might make a person possessive. No doubt she had been a popular woman in her younger years.

“Mother, Sister,” Hulan said, bowing deeply to each of them. “It’s been much too long.”

“Yes. Too long indeed,” Hu’s Mom said, and then she looked at Maomao and the others and slowly dipped her head.

Her features resembled those of Hu’s Sis, but she had a retiring quality and a calmness in her eyes. Physically, her eyes were more downturned than her daughter’s, but she exuded a unique loveliness.

“Hulan, I think that’s enough of a greeting when we have visitors.” She turned to Maomao and her group. “You must accept my apologies for my son’s thoughtlessness.”

Apparently this was where Hulan got his modesty. Her voice was as reserved as her appearance.

“Not at all,” Maomao said, then glanced at the granddaughter. “If I may, perhaps I could examine the patient’s scar now?”

“Yes, please do take good care of Xiaohong.”

The girl gave her best bow. Xiaohong, “little red,” was presumably a pet name, but Maomao had never heard her actual name.

She looked quite different now from how she had before; her hair, once dark, was now mostly light, and evenly trimmed. The roots were a light brown that verged on golden, while the ends were still black, giving the impression of a brush that had been dipped in ink.

“All right, I’ll see you later,” said Hulan. He and his mother would hold their own conference while Maomao did her exam.

Maomao and the others entered the room where she always did her exams. Well, maybe “exam” was a strong word. Mostly she just inspected the scar, then applied some salve in hopes that it wouldn’t be too visible in the long run.

There were no servants in the house. The scar on her abdomen might not have been very obvious, but the family didn’t want it to be public knowledge that the girl had had surgery. If the scar vanished more or less entirely by the time she was grown up, that would be the best of all worlds.

“I’m finished for today. If you find you need more salve, please don’t hesitate to come to the medical office and I’ll prepare some. But common stuff from the market would be fine too.”

“Thank you so much,” Hu’s Sis said, bowing deeply.

Although it wasn’t really that kind of visit, she’d set out tea and snacks on a table. Chue’s eyes gleamed as if to say Let’s have a bite before we go home.

“Hulan isn’t back yet, anyway. Why don’t we take it easy?”

“I don’t think there’s any special need for us to wait for Master Hulan to leave,” Maomao said. What were they, a bunch of adolescent girls who had to do everything as a group? They had Lihaku there as a bodyguard; it would be fine.

“Miss Maomao, are you telling poor, starving Miss Chue to walk right past these beautiful, delicious-looking treats and not eat them?”

“Go ahead and eat them, Miss Chue.”

“Woo-hoo! I knew you were one of the good ones, Miss Maomao. I could kiss you!” She came at Maomao with her lips puckered, but Maomao shoved her away. “Aww, don’t be like that!” Chue said.

“Uh-huh,” Maomao said, and set a glass of milk tea in front of Chue. Chue promptly mixed in some honey and stuffed a baked treat into her face. It was a cookie with dried grapes and walnuts worked into it; it smelled richly of butter. Maybe there was wheat germ in there, because the color was pale, but it would be very nutritious. It was certainly enough to pass for a luxurious indulgence with ingredients so hard to come by.

Maomao nibbled on one of the cookies herself. As for Lihaku, he had his guard duties to think of; he only stared intently at the sumptuous-looking treats. Yes, he was doing his job, but Maomao still felt a little bad for him.

“Ahem, excuse me?” Maomao said to Hu’s Sis.

“Yes? What is it?”

“Would it be possible to take a few of these cookies back with us?”

A souvenir for the quack doctor.

Maomao worried that maybe she was out of line, but Hu’s Sis smiled faintly and nodded. She no longer seemed on edge the way she had when they first met; in fact, she seemed very collected. “Very well,” she said. “I’ll get some for you right away.”

Just as she was about to leave the room, Xiaohong tugged on her sleeve. “I can get them.” Xiaohong went out, looking happy—she, like her mother, seemed to be feeling much better than before.

Chue watched the mother and child with a smile as she munched on her snack. Maybe she was silently willing them to bring back lots and lots of goodies for them.

“I gather the lady of the house is staying with you,” Maomao said. If there had been nothing to talk about, she would have stayed silent, but since she had a subject she could bring up, she did. Hu’s Sis had been kind enough to give them these treats; Maomao wanted to repay her by trying to be at least somewhat sociable.

“Yes, that’s true. She feels there’s rather too much commotion at the main house, so she lives here instead. Although she’s also worried about Xiaohong.”

This was Hu’s Sis’s own mother they were talking about, yet somehow she didn’t look entirely happy.

Maybe the two of them don’t get along? Maomao wondered—and that was when they heard the “Eek!” from outside.

Hu’s Sis jumped up and rushed out of the room, Maomao and the others following close behind.

The shout had come from Xiaohong, who was in the garden of the mansion with someone pulling on her hair. Namely...

That obnoxious brat?!

The little monster, Gyoku-whatever-it-was, was pulling Xiaohong’s hair. His minder was nearby, but she only looked on apprehensively and gave no sign of trying to stop him.

“Gyokujun! What in the world are you doing?!” Hu’s Sis ran over to separate Xiaohong and the little monster—er, Gyokujun. She stood protectively in front of her daughter and glared at her nephew.

Gyokujun, meanwhile, tossed aside a few stray strands of Xiaohong’s hair that had gotten wrapped around his fingers. “What was I doing? I was just trying to help her get rid of that filthy hair.” He didn’t sound like he felt the least bit guilty. In his left hand he held a mud ball that he was preparing to smash into Xiaohong’s hair.

“It is not filthy!” Xiaohong sniffled.

Hu’s Sis looked somewhat uncomfortable, even though she was defending her own daughter. “Xiaohong is not filthy,” she said. “She’s your cousin.”

“Cousin? But her hair, it looks like an outlander’s hair!”

“That’s just how it happens to look. There are lots of people in the western capital with light hair—you know that.” Hu’s Sis was acting very calm with her not even ten-year-old nephew, but it was obvious she was working hard to control herself.

“But Auntie, you used to throw stones at outlanders when you saw them! My father told me so.” Gyokujun was scowling.

Xiaohong studied her mother’s expression; Hu’s Sis looked even more uncomfortable than before.

Ahh. She remembered, Maomao realized. Gyokujun was doing things that Hu’s Sis had once done herself.

You can’t change the past, so it only makes you feel more and more guilty.

“No, don’t!”

Gyokujun had chosen that moment to let fly with his mud cake.

But it never left his hand. “All right, that’s enough pranks.” Chue had stopped his small fist cold.

When did she...

Chue had gotten behind Gyokujun in the blink of an eye.

“Hey! What d’you think you’re doing?!”

“Now, now. Water is a precious resource here. Just think how hard it would be to wash if someone got all messy with something like this.” Chue smiled pleasantly as she crushed Gyokujun’s hand, mud ball and all. It must have hurt, because when she finally released him, his face twisted and he rubbed his hand.

“What d’you think you’re doing? Do you know who I am?!” Gyokujun demanded, tears threatening to form in his eyes.

“I certainly do. You’re Master Gyokuen’s great-grandchild, Master Gyoku-ou’s grandchild, Master Shikyou’s eldest son, the honorable Master Gyokujun.”

“Well, if you know all that, then—”

“However!” Chue continued. “They say a woman’s hair is her very life. I don’t know if that’s true exactly, but I can guarantee that acting this way won’t make you popular with the ladies for one second!”

Chue looked at the hair-pulling victim, Xiaohong, who was hiding behind her mother with tears in her eyes and sniffling.

Lihaku kept a respectful distance; as a bodyguard, he couldn’t get too far from Maomao and the others, but he showed no sign of intervening. He seemed to consider this just a spat between two kids. Maomao took the same tack; Chue was handling this, and she wasn’t going to gang up on some kid. Having said that, Gyokujun still didn’t look like he had learned anything from this moment, and Maomao’s impression of him as a little beast only grew.

“Huh, fine. I don’t care about her dumb hair. But did you know they were dyeing it all this time? That proves she’s an outlander. She’s an outlander changeling who’s here to hurt our family.”

“Changeling?” Maomao cocked her head. She hadn’t meant to jump into the conversation, but it was such an unfamiliar word that she’d opened her mouth before she could stop herself.

“A changeling is a child born to fairies or the like and then swapped with a human child,” Chue explained helpfully.

“Just look at her! You can tell,” Gyokujun said. “Both her parents have black hair. But hers is...like that! Anyone can see there’s something wrong with her. They say she’s my cousin, but that’s a lie!”

So a changeling is like a “devil’s child”? The term referred to a child who didn’t resemble her parents; as the expression suggested, it was considered an ill omen.

In any case, there was something Maomao felt obliged to correct. “Two parents with black hair can still have a child with a different hair color, you know. It’s like how some cats might be black and white while their siblings are striped, even if they come from the same litter.”

Maomao thought she was putting it in a way that a child could understand, but the little monster called Gyokujun wasn’t even remotely listening. Maomao glared at the lady-in-waiting who was supposed to be watching him, willing her to do something, but the woman only looked away.

He hasn’t learned a thing since he injured the quack doctor.

She thought a good whack would be the quickest way to administer a lesson, but when she glanced back again, she found Chue talking to the boy.

“Master Gyokujun,” Chue said. “Are you very important?” She wore her usual indolent smile and clapped her hands a couple of times to brush the mud off them.

“You better believe I am! For I am Gyokujun!”

“Yes, I know. So, why are you important?”

“Because I’m the oldest son of the oldest son of this house. Someday I will lead the western capital.”

“So you’re important because you’re Master Shikyou’s child?”

“That’s right!” Gyokujun puffed out his chest.

Nothing like borrowing daddy’s authority.

It was one major reason Hu’s Sis couldn’t take a firmer hand with Gyokujun. Maomao glanced at Xiaohong’s head as she clung to her mother. The woman must have heeded Maomao’s warning to stop dyeing the girl’s hair, because there was a good stretch of light color there now. But there were specks of blood by the roots; that must have been a pretty good pull. Maomao felt any possible sympathy for Gyokujun wither and die.

“All right, next question,” Maomao said, taking over from Chue. “Why is Master Shikyou important?” Chue stepped back, allowing her to lead the conversation.

“That’s because he’s Grandpa’s son...”

“Oh, I see, I see.” Maomao’s lips twisted. “Even though Master Gyoku-ou is gone now?” By this point she was grinning outright.

It was not a very nice way to put the matter to a child. She was using the words like a blade to eviscerate him.

Gyokujun’s face went blank. Whatever the central government might or might not have thought of Gyoku-ou, there were many who loved and admired him in the western capital, and to speak of his death here was perhaps not the smartest move.

Maomao knew it was petty and mean, but she was determined not to feel any remorse. Xiaohong’s mother couldn’t say anything, so she would.

“Master Shikyou is still around, I guess. But I hear he lives quite at his leisure. Do you still believe he’ll ultimately lead the western capital? Or are you saying you’re the appropriate instrument to rule this place?” Again, a harsh way to speak to a child not yet ten years old—but she wanted him to get this through his head. “Are you yourself important?” she asked.

If no one ever disciplined an obnoxious brat like this his entire life, he was never going to grow up to become a decent politician. If he coasted along, learning nothing, on the assumption that his bloodline would land him in the same position as his father, he would eventually be sorely disappointed.

Gyokujun paled before her eyes. Maybe he was beginning to understand, in his own childish way. He might be descended from the son and grandson of the undisputed most powerful man in the western capital, but even the most powerful protectors could die at any time—and a child with no protector would end up as a puppet at best, banished at worst.

“M-My dad would never die!” Gyokujun exclaimed.

“Nobody knows when they’re going to die; that’s what it means to be human. Now, you don’t mind if I treat Lady Xiaohong’s head, do you?”

Maomao took Xiaohong by the hand, intending to lead her back to the room, but a clear, commanding voice said, “Wait just a minute!” Maomao turned to find a middle-aged woman standing there—Hu’s Mom.

“Grandma!” Gyokujun cried and hugged his grandmother, clinging to her. Hulan was there too, just behind her. “These people! These people, they said the worst things!” Gyokujun said, clutching his grandma with his muddy hands. There was no trace of the smart-ass from moments before; now he was all sweet grandchild.

Hulan smiled wryly at his nephew’s antics, then put his hands together in a gesture of apology to Maomao and the others.

As for Hu’s Mom, she looked down at Gyokujun, then at Maomao, then let her gaze drift over Hu’s Sis and Xiaohong before it finally settled on Chue. “There was quite a bit of commotion out here. Whatever is going on?” she asked, her voice gentle to placate her grandson.

“They said... They said father is going to die!” Gyokujun yelped.

Dumb kid. Twisting what they’d said so that it wouldn’t look like it was his fault.

Hu’s Mom’s face darkened, and she shot a glance at Hulan to see his face. Hulan didn’t say a word, but it was clear from his expression that he didn’t intend to serve as his nephew’s ally.

“Gyokujun. Is this true?” Hu’s Mom asked.

“Of course it is!”

“Really?”

“Y-Yes...”

“I was watching the whole time, you know.”

At that remark from his grandmother, Gyokujun’s expression did another flip. He turned to his uncle, Hulan, but the young man made no move to help him.

Kid’s a master of the quick change, huh? The boy had yet to develop his uncle’s force of personality.

“What were you doing to Xiaohong? Why are your hands all muddy?”

“Uh, it was all a...a misunderstanding...” Gyokujun started to stumble through an excuse, but if they had seen the whole thing, there was really no point. At the same time, though, Maomao started to sweat too.

A few seconds later, Hu’s Mom gave an exasperated sigh. “Gyokujun, go back to your room. Take him, please,” she said to the lady-in-waiting. The attendant led him off, although he didn’t neglect to stick his tongue out over his shoulder as he went.

“You must forgive such rudeness in front of our visitors,” Hu’s Mom said, bowing to Maomao and Lihaku in turn. She seemed to understand that her grandchild was a bit of a lout. Maomao had worried she might get a piece of the woman’s mind for bringing up Gyoku-ou’s death, but Hu’s Mom didn’t say anything about it.

Instead she turned to Hu’s Sis and Xiaohong. “Xiaohong, would you come here for a moment?”

Xiaohong left her hiding place behind Hu’s Sis and went over to her grandmother. Hu’s Mom began to run a comb through Xiaohong’s hair. “It doesn’t look too bad. I’ll give Gyokujun a serious talking-to later.”

“Mother!” Hu’s Sis said, indignant.

“Yes?”

“That’s it? You know how cruel Gyokujun can be to Xiaohong—so why did you bring him here?”

She brought him?

Ordinarily, Gyokujun would be in the main house. Maomao could see why Hu’s Sis wouldn’t want her mother deliberately bringing her nephew here when they both knew what he would do to her daughter.

“Things aren’t easy for Gyokujun at the main house, you know. I wish you would understand that.”

“Understand that!”

“His mother can’t protect him by herself. What else are we supposed to do?”

What’s this about his mother? She can’t protect him?

His mother, presumably, was the woman who had come to apologize for Gyokujun injuring the quack the other day. The one who had tried to force Gyokujun’s head down, weeping herself the whole time. One heard much talk of Gyoku-ou’s no-account eldest son, but one didn’t hear nearly as much about his bride.

“This isn’t the time. We still have visitors,” Hu’s Mom said.

Not the time? Maomao understood what she was saying, but didn’t much like the way she said it. Hu’s Sis bit her lip and glared at Hu’s Mom.

Hu’s Mom simply walked away as if nothing had happened. Hulan followed, bowing to them as he went. Hu’s Sis had an uneasy smile on her face; in spite of all that had happened, she seemed to want to put on a brave front for Maomao and her companions.

“I’m sorry you had to see that. Shall we go back?” she asked. It was clear how much effort she was expending.

“U-Um...” Xiaohong sniffled and tugged on Maomao’s skirt. “Please don’t talk bad about Grandpa.”

Gyoku-ou wasn’t just Gyokujun’s grandfather—he was Xiaohong’s too.

After a second, Maomao said, “You’re right. I’m sorry.” She had to admit that she had been wrong this time, and apologizing was the right thing to do.

Chapter 5: Third Son, Second Son, Eldest Son