Character Profiles

Maomao

A former pleasure-district apothecary. After a stint in the rear palace and then the royal court, she now finds herself an assistant to the medical office. With things finally calm again in the western capital, she’s come home for the first time in a year. She’s finally started to seriously entertain Jinshi’s feelings, but given his position, she knows there are going to be challenges. Twenty-one years old.

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. Inhumanly beautiful. In the end, he has to go back to the royal capital without ever having gotten his revenge on Rikuson. He’s on cloud nine now that his feelings finally seem to be getting through to Maomao, but because of his position, he has a lot still to think about. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-two years old.

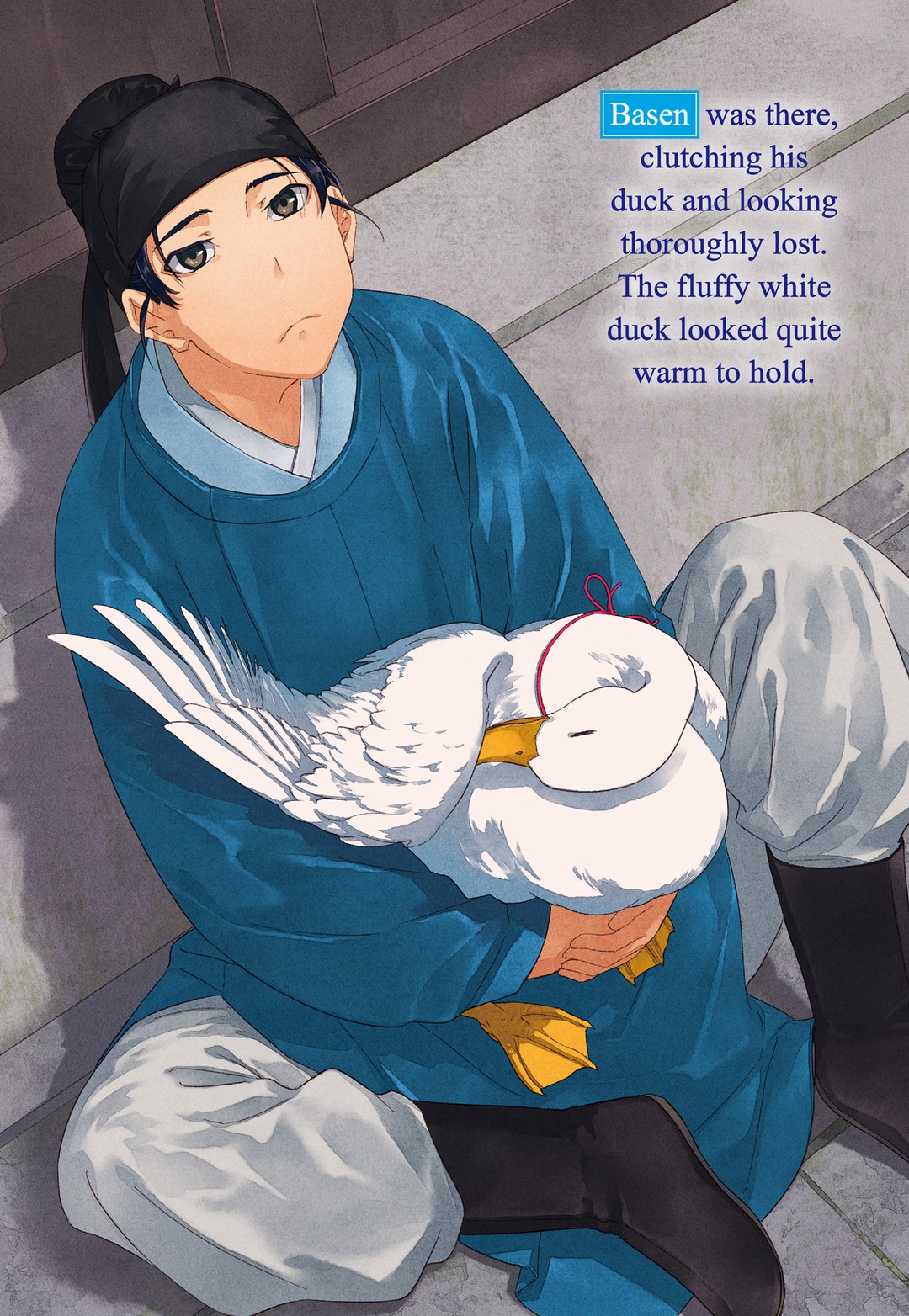

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant. Brings his duck, Jofu, home with him from the western capital. He has feelings for His Majesty’s former consort Lishu. Twenty-two years old.

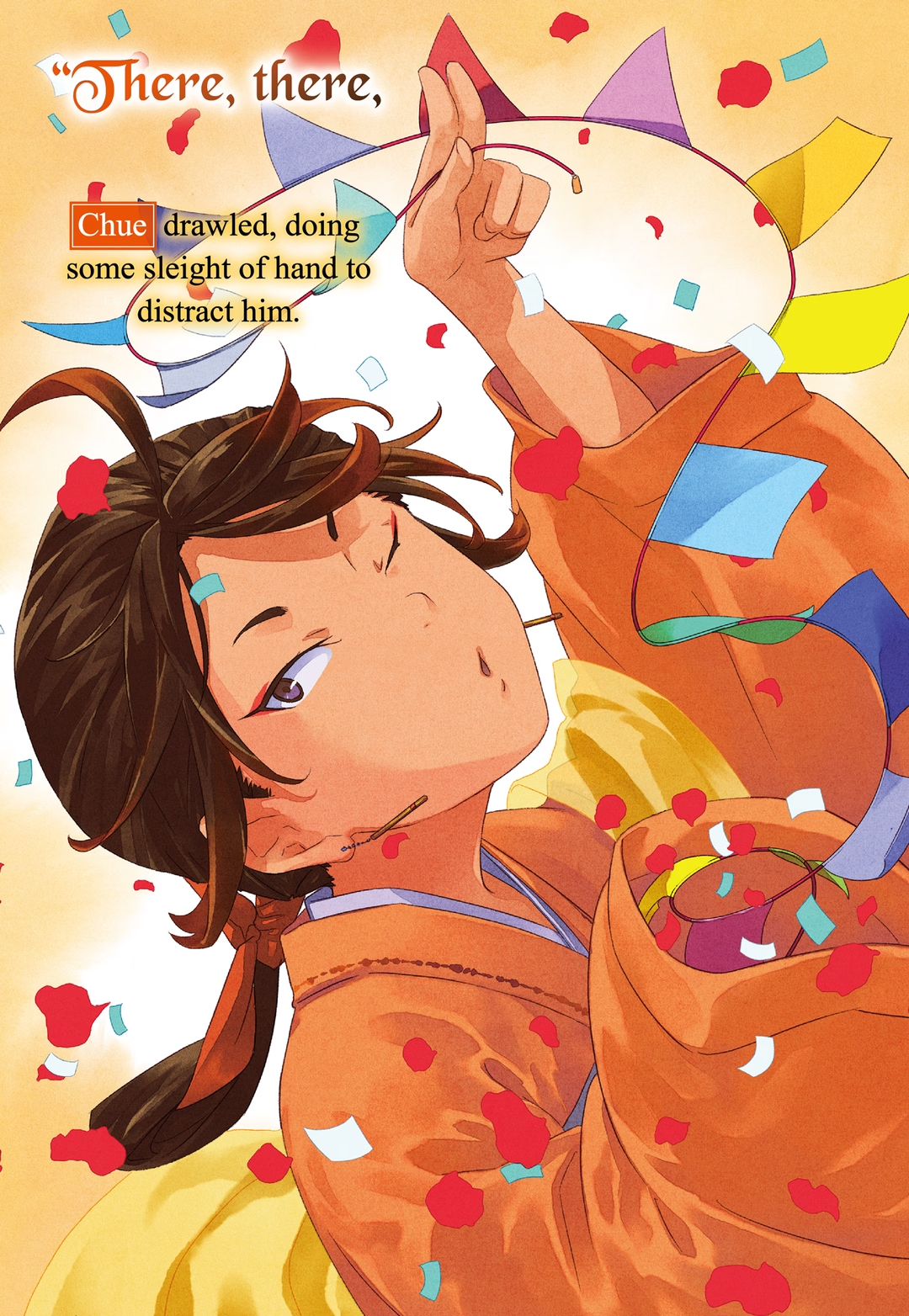

Chue

Wife of Gaoshun’s son Baryou. She acts silly, but she’s a member of the Mi clan and an expert at gathering intelligence. When rescuing Maomao, she sustained injuries so serious that she can no longer use her dominant hand.

Lahan’s Brother

Older brother of Lakan’s adopted son Lahan. He’s actually a very capable person, but because he doesn’t realize that, he always seems to come up with the short end of the stick. Perhaps because he shares his name (first and last!) with another young man in the western capital, he was left behind by mistake.

Lahan

Lakan’s nephew and adopted son. A small man with round glasses, he’s been looking after his father’s house in the royal capital during Lakan’s absence. A very capable and thorough bureaucrat. Loves numbers. Twenty-two years old.

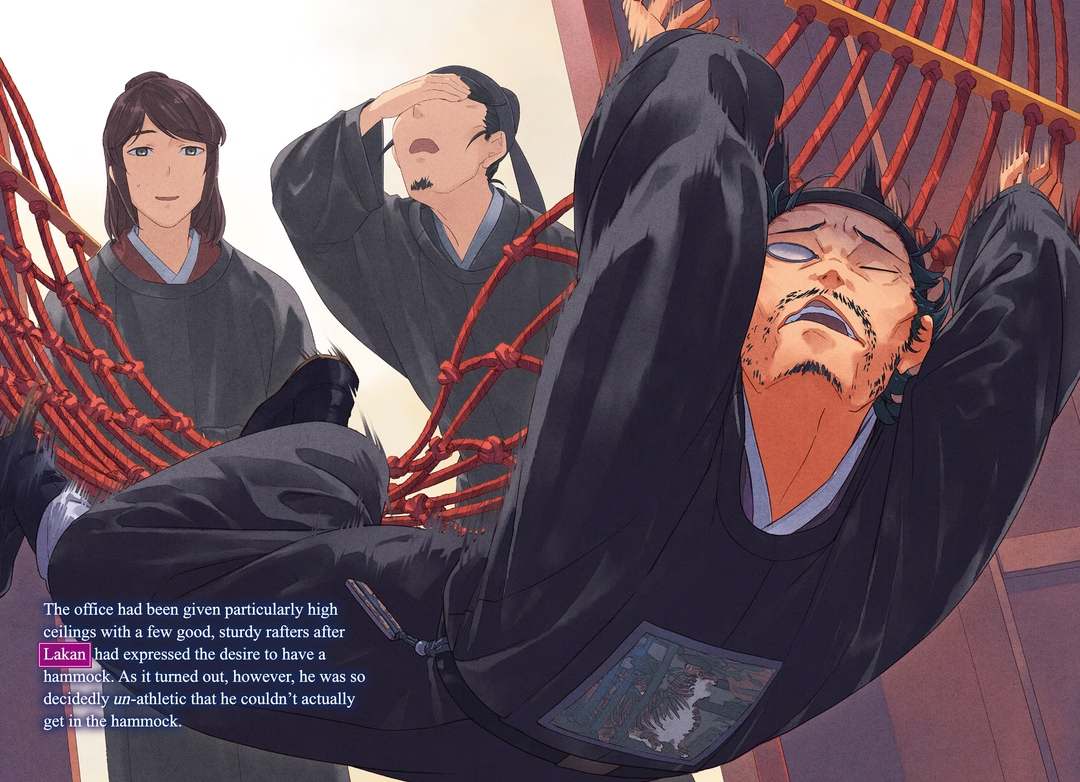

Lakan

Maomao’s biological father and Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle. He’s finally back in the capital after a year away, but he still marches to the beat of his own drum.

Rikuson

Once Lakan’s aide, he now serves in the western capital. He has a photographic memory for people’s faces. In truth, he’s a survivor of the otherwise exterminated Yi clan, and has secretly exacted revenge for his family. Completing his life’s work seems to have helped him relax, and he now spends his time tormenting the Emperor’s younger brother.

Onsou

Lakan’s current aide. If he’d had his wish, it would be to drag Rikuson back from the western capital.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting and former wetnurse. A real soft touch when it comes to Jinshi.

Jofu

A common white duck with a dark spot on her beak. She began life as an egg hatched by Lishu, but from the moment she saw Basen, they’ve been inseparable. Jofu knows how to get along in the world, and can find food anywhere she happens to be.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. She’s the mother of the crown prince, but her appearance makes some feel she’s not fit for her office. Twenty-three years old.

Yao

Maomao’s colleague and Vice Minister Lu’s niece. She may not know much about the world, but she’s trying to make it on her own as best she can. Has recently taken an interest in Lahan. Seventeen years old.

En’en

Maomao’s colleague, she’s also Yao’s lady-in-waiting. En’en is a big part of the reason Yao isn’t off on her own yet. It bothers her no end to see Yao interested in Lahan. Twenty-one years old.

Tianyu

A young physician. A dangerous character who especially likes corpses and dissecting things.

Maamei

Basen’s older sister. Since Taomei and Gaoshun, her mother and father, were in the western capital, it fell to her to run Ma clan affairs. She has two children of her own, and also raises her younger brother Baryou’s son.

Dr. Liu

An upper physician at court. He and Luomen studied in the west together. He imparts stern instruction to Maomao and her friends.

Dr. Li

A middle physician. He went to the western capital with Maomao and the others, and the stuff he saw there has made him a tougher person.

Kan Junjie

A young boy who was brought along from the western capital for some reason. He has an extremely common name.

Ah-Duo

An old friend of the Emperor’s; one of his former consorts. They had a son together. Thirty-nine years old.

Pairin

One of the Three Princesses at the Verdigris House. An amply endowed woman with a gift for dancing.

Joka

One of the Three Princesses at the Verdigris House. She knows the Four Classics and Five Books by heart.

Chapter 1: Lahan and Sanfan

They could see a crowd at the port. Everyone had come to greet the great ships that now sat in the harbor. The Emperor’s younger brother was returning from the western capital after almost a year away—no wonder everyone wanted to be there.

Lahan was one of those who had come to greet the Imperial younger brother, and now he observed the ships from his carriage.

“Master Lahan, may I park the carriage here?” came a polite voice. It was Sanfan—that is, “Number Three.” She was a young woman Lahan’s age, but she wore men’s clothing and kept her hair neatly trimmed. If one didn’t know better, she probably would have looked like a particularly handsome young man.

As to why her name was a number, that was because Lahan’s adoptive father Lakan couldn’t remember names. Sanfan was the third person he’d taken under his wing because he could see potential in her, so she was simply called “Number Three.”

Sanfan was in fact the daughter of a merchant family, but after she had run from her parents’ chosen marriage match in disgust, she’d come to Lakan and given him the hard sell on her skills. Normally he would have turned her away on the spot, but she had commercial knowledge as befitted the daughter of a merchant, and so he took her in.

Currently, Lahan and Sanfan were busy working their side hustles to repay Lakan’s debts. Sanfan wore men’s clothings in part to prevent people from underestimating her just because she was a woman—and in part as a reaction to her parents’ attempt to force an unwanted match on her.

“Hmmm... Park right near the port, if you would. If you mention my honored father’s name, they’ll let us through.”

“Very well.”

Lahan took out a golden plaque inscribed with the character La. Ordinarily, such a thing belonged with the head of the clan, but if they gave it to Lakan, he would only lose it, so Lahan kept it on his behalf. Under any other circumstances, that would have been unthinkable, but with Lakan the unthinkable was par for the course.

Some people joked that with that plaque, Lahan could make a bid for control of the clan anytime he wished—but Lahan knew better than anyone that if he made a play for the family headship, it was he who would be crushed. Besides, he had no interest in taking over. He was the one working himself to the bone to pay off Lakan’s debts; he was as filial as they came.

“Incidentally, were there no other drivers available?” Lahan asked. Sanfan was holding the reins herself; that meant talking through the small window to the driver’s bench, which wasn’t entirely conducive to conversation.

“Hmm? Ah, no, not really. Hiring a driver would have cost money, and I had time to kill anyway. Waste not, want not, no?”

“I suppose. Yet when I’m with Yifan and Erfan, there’s always a driver.” Somehow it was only when he made a request of Sanfan that no drivers were available and she came instead.

“Oh?” She seemed intent on playing dumb. Lahan decided to let it pass.

Sanfan parked the carriage and got down off the driver’s bench. Lahan got out as well, leaving the carriage in the care of one of the bodyguards who had accompanied him.

The passengers were just disembarking from the ship, and finding Lakan was a simple task. The direction where all the shouting and swooning was coming from was where the Imperial younger brother was, whereas the strangely deserted, quiet part of the dock was where Lakan could be found. Nobody who knew Lakan’s reputation would get too close to him if they didn’t need to.

“Excuse me, thank you, let me through, please,” Lahan said, working his way toward Lakan. The old guy stood on the far side of a wall of people, looking beaten. In fact, the crowd had formed a perfectly circular buffer around him; it was rather funny. Lakan’s aide Onsou was leading him along.

Lakan was not one for moving vehicles. A carriage he could survive, but a ship was too much for him. Lahan himself was badly prone to seasickness, and moments like this reminded him that the two of them were truly connected by blood.

“Sir Lahan!” Onsou said when he noticed him. He looked even more tired than the last time Lahan had seen him; his year’s service in the western capital must have been trying.

“I’ve come to meet my father,” Lahan said. “It doesn’t look like he’s going to be much good to anyone for a while, so I’d like to take him home, if you have no objection.”

In principle, Lakan was a high official, and should probably have put in an appearance at his office to report after his return to the royal capital.

“None at all, sir, if you would be so kind. I’ll inform the Moon Prince for you.” Onsou looked positively relieved. “I think he’ll agree that this was the easiest way.”

“I think he might.” Lahan had one of the bodyguards carry his pale-faced father to the carriage. “Now,” he muttered to himself, “am I going to ride in the same carriage as my honored father?”

If he were honest, he wasn’t eager to be in there, where the air would be perfumed with the smell of stomach juices and other filth. Instead, once Lakan had been safely pitched into the carriage, Lahan climbed up on the driver’s bench.

“M-Master Lahan?” Sanfan said.

“I realize it’s a bit tight up here, but we’ll survive. I’m afraid that if I ride back there with my father I might be sick to my stomach, myself.”

Much as he felt bad for Sanfan, Lahan couldn’t ride a horse by himself, and he didn’t have the stamina to walk all the way home. By process of elimination, that left sitting on the driver’s bench beside Sanfan.

“Sigh! I would have liked to pay my respects to the Moon Prince, but so it goes. Next time.”

Even if he forced his way into the crowd, he would inevitably be lost among the adoring throng. Lahan knew that he was just a plain-looking man, undistinguished in appearance and not even especially tall. In order to get people’s attention, someone like him needed the proper stage to demonstrate his abilities, as well as information that the other person would be interested in. One needed more than just a fancy outfit; one could not simply overdress. Without anything to back it up, that would only make one look comical.

No, this was just like investing: Never let a good opportunity slip through your fingers, that was the key. The Moon Prince was a discerning man, not easily fooled. Lahan could not abide someone who was beautiful on the outside but not the inside—and from that perspective, the Moon Prince seemed to have been crafted by heaven itself specifically to meet Lahan’s ideal.

“A whole year... I wonder if Maomao’s at least got one in the oven,” he mumbled. His younger sister occurred to him almost as an afterthought. Much as he might have liked to speak with her immediately, he would have to do something about the cargo in his carriage first.

“Master Lahan, shall I contact Lady Maomao?” Sanfan asked.

“Would you?”

“I’ll ask her to stop by the mansion.”

“I wonder if she will.”

“I’ll write that you wish to speak with her about the matter of her friends—although she might ignore you even then.”

Lahan thought about it for a second, then said, “Very well, thank you. Please do.”

Sanfan frequently wrote letters on Lahan’s behalf, at least when they were straightforward enough. Maomao didn’t know Sanfan, but Sanfan knew about Maomao. The acquaintance only went one way.

“I will. We need Lady Maomao to come collect them as soon as she may,” Sanfan said, oddly subdued.

As to who “they” were, the answer was apparent the moment the carriage arrived back at the mansion. Standing by the weird Shogi-piece-shaped object outside were two women.

“Master Lahan!” said the taller, slimmer one, approaching the carriage. Her name was Yao, and although she was still only seventeen, she was taller than Lahan. Behind her, looking on with a proper glower on her face, was En’en. These were the friends of Maomao to whom Sanfan had alluded. Lahan had allowed them to stay at the mansion once in order to have a favor he could call in with Maomao, but it had been his mistake—because for some reason, the two of them had never left.

“How was Maomao?” Yao asked, and her face was so perfect that even when worried, she looked positively lovely. However, that was all. Lahan heard alarm bells going off in his head: He knew he couldn’t get any closer to Yao.

“I only went to bring my honored father back. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to collect my little sister. I believe I told you that when I left, didn’t I?” Lahan replied—from a safe distance. The closer he got to Yao, the more frightening her servant En’en’s face became.

“Oh...” Yao said, letting her hair droop over her ears and looking dejected. For some reason, En’en was still glaring at Lahan. She seemed to think it was his fault that Yao was upset. What the hell was he supposed to do?

“Is there anything else you want? If we stand out here talking, we’ll only keep the master of the house waiting forever,” Sanfan said, her eyes narrowed. Her tone was distinctly prickly.

“No, there’s not. You must pardon me.” Yao narrowed her eyes right back, while En’en gave the most brittle of smiles.

“Further, I believe the agreement was that you would stay here until Lady Maomao returned, out of your concern for her, yes? I’ll arrange porters for you, so see that you pack your luggage,” Sanfan said, and her smile was open and easy. “Since Lady Maomao has indeed safely come home, you must no longer have the slightest bit of interest in this household.”

He couldn’t quite put his finger on why, but Lahan’s sixth sense was telling him that he was standing in the middle of a battlefield.

“Hmm, yes,” Yao said, thinking about something. “Could you perchance give us a few days? We’ve stayed here for so long, putting our bags together will be a time-consuming project.”

“Heavens, and here I assumed your oh-so-capable lady-in-waiting would have everything ready like that. You know, I thought I heard that a relative of yours had gone to the western capital as well. Wouldn’t you normally prioritize greeting them over Lady Maomao?”

“You heard right, but my uncle is going to stay in the western capital for the time being. The situation has his household in such a tizzy that there’s no place for me there.”

What was going on here? Their exchange sounded so polite, and yet Lahan could see sparks between Yao and Sanfan. Not to mention En’en, who continued to glare at him.

In any case, Lahan found himself with one goal in mind: to get out of there as fast as he could. He hopped down from the driver’s bench and called one of the nearby servants. “Is a bedroom ready for my father? Make some congee, something easy on the stomach, and get some sweets—but nothing too fatty. Some fruit might be a good idea. Make sure the fruit juice is nice and cold.”

“Yes, sir,” the servant responded.

“All right. I’m going to go take care of the rest of my work.”

Lahan trotted briskly away from the scene, trying not to look like he was fleeing.

Chapter 2: Lahan and the Dangling Corpse (Part One)

For Lahan, it was simultaneously a good thing and a bad thing to have his father back from the western capital.

“You must go to your office today, Honored Father. You should put up a good front, at least on your first day back,” Lahan said as he watched Lakan drowsily eat his congee. Three children stood beside Lakan: From the biggest downward they had been dubbed Sifan, Wufan, and Liufan—numbers four, five, and six. They were a trio of orphans Lakan had picked up somewhere who now performed menial chores around the house.

Sifan was assiduously bringing the spoon to Lakan’s mouth. Lakan was really just being lazy, but the wrong onlooker might have thought he had a thing for young boys. Had he been forced to feed himself, however, he would have drawn the meal out forever—much like a kid, in fact. So this was how it would be. In addition to the other three children was another boy, not yet old enough for his coming-of-age ceremony; he was substantially smaller even than Lahan.

Lahan didn’t recognize the boy, but he had appeared the day before, saying he had been instructed to serve Lakan. From his facial features it was clear he came from I-sei Province, but why he had come was less obvious.

“Pardon my asking, but who are you?” Lahan said. “Did my honored father collect you?” Lakan had a certain habit of just finding people; the boy could have arrived that way. That would be all well and good if he was an orphan, but if he had parents, then it became a kidnapping. “If you want to go back to the western capital, just tell me. It’s my father’s mess, but as his relative, I’ll take responsibility for making sure you get back.”

Having the head of the clan back got Lahan out of a number of responsibilities—but it also vastly increased the number of problems he would have to solve. Getting a single child back home, though, that was easy enough. Compared to compensating for an attempt to smash down the walls of the rear palace, he would manage.

“Not at all, sir. I’ve come to work. The Moon Prince commanded me to look after Master Lakan for the time being.”

Lahan had no idea why the Moon Prince would have ordered that, but he said, “I see, I see. May I ask your name, then?”

“Certainly. I am called Kan Junjie.”

“Kan Junjie...”

His name explained everything.

Lahan was a quick thinker, and when he heard this familiar moniker, he connected it with the fact that his own older brother had not returned from the western capital. Why was he there, while this boy Lahan had never seen was here? Now he understood.

His brother and this boy shared the same family name and the same given name, so they must have been mistakenly swapped. It was patently ridiculous, but that was exactly the kind of star under which Lahan’s older brother had been born.

“Now I get it.” Lahan nodded. In his opinion, his brother was a real jack-of-all-trades, but a master of none—except for pulling the short straw, if that were a trade. He’d been left behind in a far land, where he was probably working industriously at that very moment.

Lahan bore no ill will toward his older brother; in fact, he thought he was quite a good brother, and hoped to introduce him to a pretty girl someday.

Sanfan came into the room. “Master Lahan,” she said.

“Yes, what?”

“I’m terribly sorry, but I found this among the master’s clothing, and I thought you’d want to see it.”

Sanfan held out a letter that smelled of a simple but high-class perfume. The sender wasn’t immediately apparent, but Lahan could tell who it was from the writing—lovely characters with just a hint of strength in them.

It was a message from the Moon Prince to Lahan explaining, in terms at once indirect and apologetic, who Kan Junjie was and why he was there.

It was largely as Lahan had surmised: Once his brother had returned to the central region, they would send Kan Junjie back home, and the Moon Prince wished the boy to remain in Lakan’s care until that time. With apologies to his brother, Lahan jumped at the chance to have the Moon Prince in his debt. He would love to do more favors for him, in fact—more and more, until there were so many they could never be repaid.

Lakan had finally finished his congee, and Sifan was wiping his mouth. Wufan and Liufan brought him his dessert fruit.

“Honored Father,” Lahan began, “before you go to court, I’d like to inform you of a few things that are currently going on.”

“Hrm? Everyone’s still doing their jobs, aren’t they?”

“Well, with you gone for a whole year, some breakdown was inevitable.” Lahan placed a Shogi board in front of Lakan. Lakan thought of his subordinates as pieces in a game, and indicated their disposition via the board. It had confused Lahan as much as anyone at first, but after seeing it time and time again, he’d begun to discern certain rules. He wasn’t perfect at it, but he could largely understand what Lakan wanted to communicate from the board.

“How are the pieces moving?” Lakan asked.

“Well, you see, this one has gone here, and this has moved here...” Lahan moved a Silver General inside the enemy camp and took away a Pawn. At the same time, a Lance was stolen by a Bishop.

“The Lance, eh? Always had good spirit, but seemed like a liar.”

As a matter of politics, Lakan never joined any faction—but it was only natural for a faction to form around him, even if that was never his intention. During his absence, his faction had exerted enough pressure to keep opposing groups from running roughshod, but over the course of an entire year, the unwritten rule that one should never cross Lakan had all but eroded. One of Lakan’s subordinates had gone over to another faction—but at the same time, his own group had succeeded in drawing someone from another group to them.

Before he’d left for the western capital, Lakan had given just one order to his people: “When I get back, I want everything to be exactly the same as when I left.”

The result of that order had been the loss of a Lance and the taking of a Pawn. No doubt his subordinates awaited his return with fear and trembling.

Lahan had a thought: Perhaps it had simply been too much to ask a bunch of soldiers, people not normally versed in political negotiations, to maintain the balance of power within the court. He thought they should still get passing marks, but there was no telling how Lakan would react.

“I suppose we should at least see this Pawn we’ve picked up,” Lakan said.

“Certainly.”

Lahan picked up a brush, while Wufan and Liufan brought ink and paper, and then he wrote out the orders in such a way that the aide, Onsou, would be able to understand them. He felt bad for Onsou, telling him to come to work the very day after he had finally gotten to see his wife and child for the first time in a year, but from the moment one became Lakan’s assistant, there was no such thing as time off.

The boy with the exact same name as Lahan’s brother was agog from the moment he got out of the carriage.

“This is the royal court? My! It’s so much bigger than the administrative office in the western capital.”

Lahan had been thinking about what to do with the boy; normally, he might have simply left him with Sanfan, but there was a problem: His freeloaders—ahem, Yao and En’en—had stuck their noses in. For some reason, they’d made a big show of doting on the boy, Junjie.

Sanfan and Yao didn’t get along very well, and sparks constantly flew between them, although Lahan had no idea why—or at least, he wanted to pretend he didn’t.

In any case, at least Lakan and the boy seemed to get along all right, so Lahan had decided to assign him to Lakan as a sort of junior assistant. If that made Onsou’s burden lighter, it meant Lahan wouldn’t have quite so much paperwork piling up, for which he would be grateful. Still, he had trouble imagining it would go as smoothly as all that.

“Say, En’en, are my bangs straight?”

“They’re perfect. You look as beautiful as always.”

From behind Lahan came the voices of his freeloaders. Since they were sending Lakan by carriage, it had been decided to let the young ladies come along. He could hardly have put himself and his father in a vehicle while the women walked.

“Master Lahan, it’s all well and good to be courteous to women, but I don’t think you had to go quite so far,” Sanfan whispered to him. She was serving as their driver once again. Quite frankly, it would have been more efficient to have her doing other work, but Sanfan wouldn’t hear of it.

“That’s not your decision to make, Sanfan,” Lahan said.

After a moment she replied, “Understood.”

“All right. I’m going to see my father to his office.”

Starting tomorrow, he was going to leave Lakan with Onsou—Lahan certainly wasn’t going to spend his days babysitting him.

“En’en, let’s go to the medical office,” said Yao.

That would get the two of them out of the equation, which was something of a relief. Now that Maomao was back, Lahan fully intended to have them return to their dormitory. “See you later, Junjie!” Yao cooed.

“You too! Good luck at work today, Lady Yao. Lady En’en.”

“Gosh, you don’t have to be so formal.” Yao was surprisingly familiar with Junjie herself—and just when Lahan had been so sure she didn’t like men. Maybe it was because the boy was still so young that she was able to show him some decency. “You’ll be helping your brother and your uncle now.”

Yao and En’en were about to leave when Lahan motioned them to stop. “Pardon me, but the two of you seem to be under some sort of misapprehension.”

“What do you mean?” Yao asked, tilting her head.

Young Junjie supplied the answer himself. “Ma’am. My surname is Kan, but I’m not related to Master Lakan or Master Lahan.”

“Really? I heard what Master Lakan said yesterday. He said, ‘Junjie? I think he’s my nephew,’” En’en said, doing an uncannily accurate impression of Lakan. Come to think of it, she’d been making a midnight snack the night before—had she been trying to endear herself to Lakan? Lahan shivered at the thought.

“He’s not wrong, but he’s completely wrong,” Lahan informed them. “We’re out of time at the moment, so I’ll explain later.”

It was nothing short of a miracle that Lakan had remembered the name of Lahan’s biological older brother. He had not, however, managed to remember the man’s face. Thus he had presumably classified the young Junjie in terms like “he doesn’t not seem different somehow, but he’s probably my nephew.” Both of them were studious, hard workers, so perhaps they appeared to him similarly.

Lahan was seized by a fresh desire to help his brother settle down as soon as he could.

“Erm... Is my name causing any problems?” Junjie looked deeply uneasy. Lahan, Yao, and En’en all looked at each other.

“Eh. It’s all very complicated. Don’t worry yourself. More importantly, my honored father has fallen asleep again, so give him a good shove, would you?” Lahan said.

“Yes, sir!” Junjie said, and he and Lahan proceeded to shove the sleeping Lakan’s back.

Lahan was supposed to be done worrying about Lakan once he had deposited him at his office—but there was an unusual hubbub when they arrived. A crowd had formed.

“Well, now,” Lahan said.

“What do you suppose is the matter?” Young Junjie asked. They looked at each other.

Onsou stood outside the office, and now, just hours after getting home, he already had a very grim look on his face.

“Sir Onsou. Whatever seems to be the matter?” Lahan asked.

“Sir Lahan. Perhaps you should see for yourself...” Onsou indicated the office with a significant glance. It would be quicker than explaining, he seemed to say.

Lahan looked. “Well, I’ll be.” Something very un-beautiful hung there. Namely, a man’s corpse, dangling by the neck from one of the rafters.

“Heek!” Young Junjie said, terribly frightened. “Th... Th-Th-Th... That’s...”

“A corpse, dead by hanging, yes. First time you’ve seen one?”

“Y-Yes... What is it?! What is that thing?!”

“I told you, it’s a corpse. A dead body.”

“H-How can you be so calm about it?!”

Young Junjie was all out of sorts, but for Lahan, a human corpse was nothing especially remarkable. The more people there were, the more corpses there would be; that was all.

The capital and its surrounding environs had some one million official family registers, although in Lahan’s mind, that number had to be considered no more than an estimate. Taxes were levied based on the adult population, so in order to dodge the taxman, some people lied and said they had no children when they did, or claimed that their children had died before adulthood when they hadn’t, or reported a man as a woman. Sure, some families probably also forgot to submit death reports, but no doubt there were far more people out there who were off the registers.

The court and the rear palace between them had tens of thousands of people—a significant population. The more people there were, the more chances there would be to see a dead one. If they rarely seemed to be found, well, in the worst-case scenario that was because people were successfully hiding them. Among the soldiers, it wasn’t uncommon for someone to take a hit in the wrong place during practice and die from it. There had been three recorded cases of just such a thing happening in the last year, along with eighteen people who had survived but had been so badly injured that they couldn’t continue in the military. Not a large number, as numbers went, but one had to assume there were other cases that had gone unreported.

Then there were the bureaucrats, some of whom inevitably found themselves so hemmed in by work that they took their own lives.

“Seven cases last year, as I recall,” Lahan said as he stood and studied the dangling body.

This corpse, however, did not belong to a bureaucrat: It was wearing a soldier’s uniform.

“Why, there’s one of those rain-rain-go-away dolls in here! Why, that’s the biggest one I’ve ever seen!”

“Honored father, that’s a human corpse.”

As usual, Lahan couldn’t be quite sure whether Lakan was joking or not. Young Junjie, unable to bear the sight any longer, had turned away and was covering his mouth. That would be the ordinary reaction.

Admittedly, Lahan wasn’t eager to smell the filth the body had expelled, so he covered his nose with a handkerchief.

“What would you like to do, Master Lakan?” Onsou asked. “I can have the room cleaned up immediately, or else you can do your work in a different place today.”

“If you can clean it up nice and quick, then I’m perfectly fine here.”

“You may be, Father, but I’m not so sure about everyone else.”

Lahan did not consider a dead body to be a beautiful thing. For a thing it was, once its life functions had ended; it was a person no longer. Besides, with time it would rot, and rotting was not very good for purity or cleanliness—so, in Lahan’s opinion, not beautiful.

“This room gets good sunlight,” Lakan said firmly. It was still the cold season, and it was crucial to Lakan that he have somewhere warm so he could take a nap. The whole gaggle of onlookers was watching Lahan and his group now. To be very precise, there were seventeen soldiers, ten civil officials, and three palace ladies gawking.

“By the way, who is this person?” Lahan adjusted his glasses and squinted at the man. He wasn’t keen to study the corpse too closely, but it was necessary to establish the deceased’s identity. Lahan didn’t see much prospect of getting his work done today.

“He’s a soldier Master Lakan brought into his fold about two years ago,” Onsou said. “Master Lakan described him as a ‘Lance,’ I believe.”

“This is our turncoat, then?”

“Indeed. I have a record of his service I can give you, although it’s more than a year old.”

So this was the Lance that Lahan had captured on the Shogi board that morning. Lahan had known, and told Lakan, that the Lance had been taken by a hostile faction, but he hadn’t known the Lance’s face. Remembering people’s faces wasn’t Lahan’s job; it was Rikuson’s.

“And he just decided to kill himself in my father’s office,” Lahan mused. He looked around the room. The “Lance” was dangling from a beam in the very middle of the office, which had been given particularly high ceilings with a few good, sturdy rafters after Lakan had expressed the desire to have a hammock. As it turned out, however, he was so decidedly un-athletic that he couldn’t actually get in the hammock. A pointless story of a pointless endeavor—except that the other offices were not built such that one could have hanged oneself in the middle of the room. Not far from the waste that had gathered under the body lay a toppled chair; perhaps the man had kicked it over.

Lakan’s office appeared to have been left undisturbed in his absence. It had been cleaned, but in a cursory manner. Lakan’s beloved couch had been dusted, for example, but the cobwebs on the bookshelves had not been attended to.

“Hmm.” Lahan inspected the rope hanging from the rafters, the Lance hanging from the rope, and the overturned chair. “Father.”

“Mm?”

“Is the culprit who killed this Lance—the man dangling from the rafters—here with us?”

“Mm.”

Lakan indicated the onlookers with a jerk of his chin.

“What?” Young Junjie looked at the crowd, shock written on his face. “Wh-What does that mean?”

“Keep your voice down, if you please. We don’t want the criminal to notice us.” Lahan tried to be gentle in his reproof of Young Junjie. He wasn’t in the habit of wearing kid gloves with men, but when it came to a boy who’d been dragged here by accident due to a case of mistaken identity involving Lahan’s own elder brother, sparing a bit of decency seemed the least he could do.

Young Junjie clapped his hands over his mouth. Obedient children were so much easier to work with.

“Who is it?” Lahan asked Lakan.

“White Go stone...”

The culprit might appear as a Go stone to Lakan, but Lahan couldn’t tell them apart. He narrowed his eyes.

“Ah!” The crowd was dispersing, meaning the killer was going to disappear—but Onsou seemed to have figured it out. He wasn’t quite as good with faces as Rikuson had been, but they were still his specialty.

“Sir Onsou?” Lahan turned to him, thinking what a lot of trouble this all was.

“Sir Lahan. You’re not thinking of abandoning me to handle this on my own while you go do your work, are you?” Onsou placed a hand firmly on Lahan’s shoulder and gave him a nasty smile. He was a soldier in his own right, and his grip was strong enough to hurt.

Lahan let out a breath, considering what to do, and looked at Lakan.

“I wanna sleep,” Lakan said. “But first, I wanna go see Maomao.”

Lakan’s brain was built in a way that was unfathomable to the average person. He could solve problems without using numbers or formulae, but nobody knew how he reached his conclusions. However accurate his accusations might be, making them stick without further proof would be a tall order.

“Ahem!” Lahan flagged down a nearby lower official. “Kindly go to the medical office and tell them we need to investigate an unusual corpse. Those are the words you are to use—don’t tell them it’s a hanging corpse. An unusual corpse.”

“An unusual corpse, sir?”

“Yes, and make sure you get it right. Oh, and since the medical apprentices are finally back at work, could you have them come as well? I suspect the medical personnel will leap at the chance to study a fresh body.”

This was all Lahan’s very indirect way of telling him to bring Maomao. Absolute certainty was impossible, but he figured that there was at least an eighty percent chance that she would come. That ought to help the otherwise listless Lakan muster some motivation.

Lakan would give them their answer, but an answer alone wouldn’t be enough. He would tell them who the killer was, but it would be up to Lahan and the others to figure out the motive and the manner of death. Both Maomao’s specialties.

Lahan made sure his glasses were perched firmly on his nose, and then he sighed. He was going to have to spend a long time looking at something very un-beautiful.

Chapter 3: Lahan and the Dangling Corpse (Part Two)

When Lahan saw his little sister for the first time in almost a year, she was not looking very happy. It turned out there hadn’t been any need to have Sanfan write a letter specifically to summon her.

“Hullo, Little Sister.”

The very first words out of Maomao’s mouth were “Scram, Abacus-Specs.”

“Maaaooomaaaooooo!”

Lakan was right beside her and tried to give her a hug, but she jammed a broom handle into his cheek to hold him at a safe distance. Where had she gotten that broom? Lahan was mystified.

“Maomao, perhaps you could show a modicum of compassion for him?”

“Would you, in my place?”

“Absolutely not.”

With that, Lahan turned to the two people who had accompanied Maomao. One was Dr. Liu, the head official for medical matters at court. He was a man of stern mien, of the same generation as Lahan’s granduncle, Luomen.

The other was a much younger man, of average build and with a less-than-serious look on his face.

“So where’s this dead body?” the young man asked. He looked inordinately interested, and Dr. Liu promptly rapped him on the head with a knuckle.

“That’s enough out of you, Tianyu,” the doctor said.

Tianyu—so that was his name. Not that Lahan cared about this information. To him it looked like Maomao had been accompanied by yet another troublemaker—but this troublemaker had given Lahan an excellent segue into the matter at hand, so he would let it pass. If Lakan tried anything funny, Lahan could just foist him on Maomao. Although he didn’t doubt Maomao was having the same thought about him.

“I’m not made of free time. Perhaps you would kindly show us the body? I expect the Moon Prince to give a report on our return this afternoon. I don’t have time to dally,” Dr. Liu said. It was clear that he was quietly angry. The report by the expedition to the western capital concerned Lakan as well. Lahan was as eager as the good doctor to get this over with.

“This way, please,” Onsou said, leading them into the room. They had decided to wait somewhere other than the office, as the situation was clearly too much for Young Junjie. He was a dedicated boy, though, and had asked if there was anything he could do, so Lahan had set him to cleaning another room that Lakan sometimes used. It was stuffed full of junk Lakan had piled up there the way a dog might collect slippers.

“If you’ll pardon my saying so, the La seem to go rather too easy on their own relations,” Dr. Liu said, looking at Lakan, Maomao, and then Lahan.

“What’s wrong with being smitten with my own daughter?” Lakan answered as if this were a perfectly ordinary conversation. You could lead a horse to a charged room, but you couldn’t make him read it.

Dr. Liu was no fool; he had to know that nothing he said to Lakan would make any difference. He walked casually into the office. “This is our man?” he asked. The “Lance” was still dangling from the ceiling. Lahan had given instructions that the body not be taken down. “Can’t get a very good look at him like this.”

Dr. Liu narrowed his eyes, but the man called Tianyu was downright excited. “Wow! He’s dead! He’s dead, all right.”

“You said the body was unusual, but it’s just a hanging,” Maomao muttered. She probably thought she had said it silently, but her thoughts frequently came out of her mouth in spite of herself. Lahan had instructed the messenger to say that the body was “unusual” because that implied the cause of death was unknown, which made it conceivable that there was poison involved. If he’d said in so many words that it was a hanging, Maomao would never have been interested. Lahan knew very well that Maomao would be loath to come to Lakan’s office. He’d had to manufacture a reason for her to come.

“You found him hanging here? Doesn’t that pretty much make it a suicide?” Tianyu asked. He was rewarded with another knuckle from Dr. Liu.

“Investigate! Don’t jump to conclusions based on the first thing you see. Making assumptions will only skew your judgment.” He sounded a lot like Maomao’s granduncle Luomen.

“I presume the fact that you’ve left the scene undisturbed implies you have some reason to believe this wasn’t a suicide.” Dr. Liu was already studying the body.

“That’s right, sir,” Onsou said, answering on behalf of Lakan. It was more appropriate for him to handle this conversation than for Lahan to do all the talking. “If it were a suicide, it would create a contradiction.”

“What kind of contradiction?”

Onsou answered the doctor’s question by presenting a piece of rope. “We cut this piece of rope to match the one around the man’s, Wang Fang’s, neck. We wanted to compare it with the distance from the toppled chair, to see if it would have been possible for him to hang himself.”

If a person was going to hang themselves, they had to be able to get the noose within about thirty centimeters of the chair, or they’d never be able to get their neck through it, no matter how they stretched and strained.

To Lahan’s eyes, the world was overflowing with numbers—and this contradiction was not beautiful.

“If he kicked the chair over as he jumped, then this doesn’t make sense,” Tianyu offered.

Lahan answered in lieu of Onsou. “The chair is lying with the backrest up. It would have to have spun a hundred and eighty degrees as it fell to end up like this. After all, it would be very hard to hang yourself facing toward the back rest.”

Maomao was quiet, perhaps because Tianyu was being so loud. She continued to try to keep her distance from Lakan, who was holding out a snack; Maomao was sniffing dubiously.

“Hrm. I take it you didn’t let the body down because there’s something you wanted me to double check,” Dr. Liu said.

“Precisely,” replied Onsou.

“And the chair hasn’t been moved?”

“Would you like me to call one of the onlookers to testify?”

Dr. Liu, it seemed, was a man who liked to be clear about things. He was suspicious where suspicion was warranted. He looked like he could be a hard man, but he didn’t seem the type to bend the truth, so Lahan didn’t dislike him.

“I must say, I’m surprised you felt the need to come yourself, Dr. Liu,” said Onsou, who apparently had hoped for some more junior medical personnel. His polite smile caused his right cheek to rise exactly three millimeters.

“It was the way you said to send the apprentices. They need someone to oversee them, don’t they?”

In other words, he wanted to make sure his people couldn’t be part of any cover-up.

“All right. Bring down the body, if you would.”

“Certainly.” Onsou summoned a subordinate and instructed him to lower the body to the ground. “If you would all be so kind as to have a seat and wait.”

“Don’t mind if I do!” Tianyu said, promptly claiming a spot on the couch.

“I’m happy to stand,” Dr. Liu said.

“Me too,” said Maomao, and the two of them did just that.

Even given that the rope holding the body up was cut before the body was fully on the floor, it was difficult work. The “Lance,” Wang Fang, had been a military man, and built like one. His corpse was quite a heavy load.

According to the report, Wang Fang had first been spotted by Lakan two years before. Lakan, being an excellent judge of people and quick to act, soon hired him. The man was practically made for battle, and took care of the job Lakan assigned him in lieu of a test with no trouble at all. The report noted that Wang Fang was ambitious to the point of greed—but suggested that with proper oversight, it shouldn’t be a problem.

Perhaps it wouldn’t have been, but with Lakan gone, Wang Fang hadn’t had that oversight.

“Finally got him down,” Dr. Liu remarked. The body was laid out on a cloth, and it was so not beautiful that Lahan, quite honestly, wished he could avert his eyes. The skin, which had been supple in life, was now bluish and pale, and fluids seeped from the body’s various holes.

“Tianyu.”

“Yessir!”

Dr. Liu was telling the young man to take the first look. Maomao positioned herself behind Tianyu and peeked at the body.

“What do you think?” the doctor asked.

“You can see fingernail marks on his neck. They show he fought the rope, trying to escape.” Tianyu looked surprisingly serious. He might have seemed a frivolous person, but apparently he really was a physician.

Maomao nodded and also looked at the body. “I’d say he suffered.”

“I’d say he did.”

“Doesn’t one usually suffer when one is hanged by the neck?” Onsou asked, perplexed by their exchange.

It was Dr. Liu who answered. “If you drop with enough force, the joints of the neck dislocate and you lose consciousness. In which case, you wouldn’t struggle.”

“So it’s an easy death,” said Onsou.

“Not necessarily. Get it wrong and it’s going to be very unpleasant. I can’t recommend it.” At that, Onsou gave the most pained of smiles. Dr. Liu continued, “All right, take off his clothes.”

“Yes, sir.” Tianyu began to strip the body. Maomao helped.

“What’s this? You’re helping?” Lahan asked. From what he remembered, Maomao was under Luomen’s strict instructions not to touch a dead body.

“Because this is work. I have my old man’s permission,” she said. She showed no sign of fear as she removed the clothing from the corpse. Lahan wasn’t sure how he felt about the fact that his little sister seemed so used to stripping a male body bare, even if this one was dead.

“Maomao! Don’t touch something so filthy!” said Lakan. He was one to talk; he was covered in snacks. Lahan was almost impressed that he could eat in the presence of a dead man.

“From the livor mortis on the feet, I’d say this guy’s been dead a long time. How long would you say, Niangniang?”

“At least half a day, certainly. The reddening of the lower body is quite acute.”

Tianyu plucked at the skin. “Mm. From the toughness of the flesh, I’d say not more than sixteen hours ago.” Dr. Liu didn’t say anything, so he evidently agreed. “Even granting a margin of error, he would have died sometime in the evening or night.”

Lahan touched his spectacles. What had this man been doing here so long after work hours? “You do believe he died from the hanging?” he asked.

“Uh-huh,” Tianyu replied. Again Dr. Liu didn’t contradict him.

“Do you think you can say whether it was suicide or homicide?” Onsou asked.

“Can’t tell that for sure. Like I said, the position of the chair makes me think he didn’t do this to himself, but I don’t think I could say for certain.”

This time, Dr. Liu actually nodded. Maomao, meanwhile, squinted up at the rafter overhead.

“What’s the matter, Little Sister?” asked Lahan.

She didn’t answer, but only stomped on his toes. Unfortunately for her, he’d packed material into the toes of his shoes, which distinctly blunted the impact.

“What’s the matter?” he asked again.

“I was just looking at the rope up there. I think it’s tied like a lasso. That way, you wouldn’t have to use a ladder.”

“A lasso?”

“Maybe it would be quicker to show you.” Maomao glanced at Dr. Liu for permission. He might get angry if she just started doing things on her own.

It was Onsou who gave her the go-ahead. “Do please show us, if you would. Is there anything you’ll need?”

“A rope similar to the one used in the hanging. And if you have a rock that can be tied to it, that would be helpful.”

Maomao hardly listened to anything Lahan had to say, but she seemed relatively pliant with Onsou. Lahan wasn’t sure whether Maomao realized it herself, but that preference for put-upon folks bore the distinct sign of Luomen’s influence.

“If I may, then.” Maomao took the rope and tied the rock to the end of it, then spun it around before tossing it up, where it arced between the beam and the ceiling.

“And how are you supposed to attach that to a post?”

“Look at the knot on the rope that’s up on the beam and you’ll get it. You do this—” Maomao made a loose loop with the end of the rope and passed the other end through it. “And then pull on this.” She cinched the rope tight to the beam.

“So that’s how it works,” Lahan said.

“That’s how what works?”

“I was just thinking, if it was homicide, how would they have killed him?”

The culprit would have been dealing with a powerfully built soldier—not someone who could be easily strangled. What if they were to use the ceiling beam? Then they wouldn’t have to have the strength to physically wring his neck.

“You hang him from the rafters by the neck—then you could kill him without having to be very strong.” Not to mention, that would be no sign of anything but a hanging.

“Pretty much. Although it would still be impossible for someone like me.” Maomao gave the rope a tug. She could hardly have weighed half what the dead soldier did.

“True enough. Even a man like me probably couldn’t have managed it. Not for a burly, heavy military man like that. The possible culprits my father indicated hardly seemed like they could have murdered someone so large.”

Lahan thought of the onlookers that Lakan had been watching.

“Culprits? You mean the old fart already knows who did it?” Maomao immediately scowled.

“Uh-huh! Daddy figured it out right away!”

“Ugh!”

Suddenly, Lakan was at Maomao’s side. She immediately backed up. “Eat this...please.” She just managed to sound passably polite, but there was nothing polite about the way she grabbed the nearest snack and flung it, like one would for a dog. Lakan went running after it.

“Don’t waste food,” Lahan said.

“He’ll eat the whole thing and you know it.” Maomao clapped her hands to get the crumbs off them. Well, that takes care of that, she seemed to say. Dr. Liu was looking at her like he had an opinion on all this, but he was loath to stick up for Lakan, so then he decided to pretend he hadn’t seen anything.

“If you know who did it, why’d you call a doctor?” Maomao asked.

“My honored father may know who committed the crime, but he can’t say why or how. I suppose we know how, now. Which leaves me wondering what the motive could have been.”

“The motive, right...” Maomao glanced toward the couch.

“You know?”

“More or less.”

“Enlighten me, Little Sister.”

If it turned out the murder had been arranged by Lakan’s subordinates to get back at the traitor, that would be a problem. Lahan hoped they could deal with this as quietly as possible.

“I don’t really want to say,” Maomao told him.

“You have to, or I’m going to be late for the report with the Moon Prince.”

Maomao didn’t look very happy, but she started talking. “The motive isn’t anything especially profound. The killer was female, yes?”

“Excellent guess.”

Lahan was genuinely impressed. Lakan had said “white Go stone.” In general, with him, white Go stones were women and black ones were men.

Maomao sniffed. “It’s very simple: The deceased is a man, and the killer was a woman.”

“That’s what it boils down to, eh?”

“Uh-huh.” Maomao looked down at the now naked body with disinterest. To someone who had grown up in the pleasure district, fraught relationships between men and women were nothing new.

“If you knew all that, you could have said something,” Lahan said, irked by his sister’s reticence. Still, he understood why Maomao had refrained from explaining the motive. Luomen, the man who had raised Maomao, detested baseless assumptions, and had instilled in her the belief that one should not speak too lightly, or based on guesswork alone—perhaps because those in vulnerable positions could so easily be brought to disaster by a few stray words.

“Very well. As Maomao won’t say what she means, shall I be the one to give the explanation?” Lahan asked. Once Maomao had confirmed that the killer was a woman, he had a pretty good idea of where she was going.

“No, I can do it,” said Maomao.

“Well, now.” Lahan wondered what it could mean for her to say that. In the past, she would have gladly let someone else take the lead, instead of having to talk herself. “I see there’s been some change in you, Maomao, but you should hold off. It would be better if I did the talking. Could you explain it to us?”

“All right. I’d like to confirm a few things, though.”

“Like what?”

“What kind of woman the killer is.”

“What do you mean, what kind?” Lahan thought back on the crowd of onlookers, recalling the women who had been there. “There were three of them, but I don’t actually know which one did the crime.”

“Three of them,” Maomao echoed, looking up at the rafters. “You know, don’t you, Lahan, that it would be impossible for a woman to make it look as if a big, strong soldier had hanged himself?”

“I suppose. You’re suggesting that it would have been impossible for a woman to commit the crime?” The victim probably weighed at least twice what his supposed killer did.

“Then how do you make the impossible possible? Consider the motive, and the answer reveals itself. If one woman couldn’t do it, what do you need?”

“If one woman couldn’t... Ah. I see what you mean!” Lahan clapped his hands as the realization hit. It was simplicity itself.

Maomao didn’t say another word, but only turned around. Maybe it was because of the steady stare that her boss Dr. Liu had fixed on her. He not only had to keep an eye on Maomao, but also try to restrain Tianyu’s interest in the corpse. With subordinates like that, it couldn’t be easy being him.

Lakan, meanwhile, was reclining on the couch, nibbling on the snack Maomao had thrown. It would be time for his midday nap soon. Lahan looked at him with a moderately conflicted expression on his face.

“Sir Onsou,” he said to Lakan’s aide. “Would you call the three women who were in that crowd earlier?”

“Right away.”

“Thank you.”

Judging from the position of the sun, they just had time until noon. Lahan half closed his eyes, his heart growing heavy.

Chapter 4: Lahan and the Dangling Corpse (Part Three)

The three women Onsou brought were all new palace ladies who had just passed the examinations this year. They were of reasonably respectable backgrounds; two of them were officials’ daughters while the other came from a merchant family. Each of them, Lahan thought, was notably beautiful.

He’d also taken the liberty of summoning officials from the Board of Justice. They didn’t get along so well with Lakan’s Ministry of War, but there was no reason to go looking for a fight. Lahan wanted someone there to witness the entire affair.

“U-Um, may I ask why we’ve been called here?” Palace Lady No. 1’s eyebrows dropped by three millimeters. The brief report he’d gotten about her had said that she was the daughter of a rural official and that she was staying with relatives in the capital. She had lustrous black hair.

“I can’t believe you would bring us to the very room where something so awful took place. Surely you’re not going to tell us to clean up the corpse?” Palace Lady No. 2 said, quaking. She was the merchant’s daughter, raised in the capital, and also had lovely black hair.

“I— I w-w-want to go home!” said Palace Lady No. 3, shivering violently. She was the youngest daughter of a civil official, and like the others, was a raven-haired beauty. Each of their faces was quite distinct, but from behind they would all look very similar.

“This would make it hard to tell who was who even if we did have witnesses from the projected time of death.” Onsou crossed his arms. Dr. Liu and the other medical personnel had remained in the room. “So which of these women is the criminal?” Onsou looked to Lakan, but he was asleep. Even if he’d been awake to point out the killer, it would never stick without a clearly defined motive and manner of killing—and Lahan would have found it unbearably un-beautiful to try to squeeze some forced evidence out of the situation.

“I see you appear somewhat distraught over the fact that you’ve been brought here as suspects, ladies,” Lahan said. As he was speaking to beautiful women, he wished to be as polite as he could—while at the same time hoping, indeed wishing, that they would turn out to be as beautiful on the inside as they were on the outside.

“Of course we are. This is a suicide, isn’t it? Why in the world would you say we killed him?” asked Palace Lady No. 1.

“Me, a killer? Of such a great bear of a man?” asked Palace Lady No. 2.

“When did he die, anyway? If it happened yesterday, I can prove to you that I was at my house,” proposed Palace Lady No. 3.

“Completely understandable perspectives, all of you,” Lahan said. He looked at the three ladies, his smile never faltering. “However, there are several distinct problems with the suicide hypothesis, including the situation of the room and the injuries found on the corpse. Further, I think you all should know that alibis provided by your family or friends will not be considered compelling evidence.”

The three women frowned at that.

“More importantly, did all three of you not have a motive to kill this man?” He pointed at Wang Fang’s corpse, which now lay under a sheet. “This man was as greedy as he was ambitious, and I’m given to understand that he never saw a woman who caught his fancy without trying to talk his way into her bed. Quite a few officials saw Wang Fang speaking to all three of you.”

“True, he spoke to me, all right. And not just a couple of times,” Palace Lady No. 2 said with a sigh. “But he’s hardly the only man to have made advances on me. Embarrassing though it may be to say so, surely you understand that many of the palace ladies are here seeking good marriage prospects?” Lady No. 2 was the merchant’s daughter, and she had the force of personality to match—a type Lahan hardly disliked.

“I do indeed,” he said. “Still, choosing an absent superior’s office for a tryst is, let us say, in poor taste.”

All three women blushed. That said it all.

“Whatever are you talking about?” one of them asked.

“I have a family member with a nose as sensitive as a cat’s. She discovered a very particular scent on the couch that the owner of this office so loves.”

Lahan hadn’t been able to tell himself, but apparently those with better senses of smell knew right away. Maomao, having grown up in a brothel, was particularly sensitive to it.

In short, the very couch where Lakan was now sleeping had been used to do the deed during Wang Fang’s assignations. It must have been a pleasant place for it; Lakan was very particular about his couches.

“Only a minimum of cleaning was done in this office during its owner’s absence—yet the area around the couch was unaccountably cleaner than anywhere else. You may have thought you had tidied it up so as not to leave any evidence, but since we have someone here with an animal’s nose, we knew right away.”

Maomao was glowering at him, while beside her Tianyu was saying, “Shoot, and I sat on that!” As for Lakan, currently snoozing on the guilty couch, he showed no sign of waking up.

“S-Suppose this room was that man’s little love nest. That hardly means we were the ones he was here with,” Palace Lady No. 1 said, her voice trembling.

“Much as I might like to agree with you, I can’t,” said Onsou, stepping forward. “This is Master Lakan’s personal office. No lady in the entire court dared approach it before he left for the western capital—they knew Master Lakan too well.”

Lakan was unpredictable; you never knew what he would do next. So other officials resolutely kept their distance from him, and even the court ladies made it a point not to get too close, in the same way that nobody would willingly walk into a warehouse full of gunpowder.

Many had once made light of Lakan, seeing as he was the oldest son of a famed household yet was branded a failure. The criticism had rolled right off Lakan’s back, though; as long as he could play his board games, he was happy.

Once Lakan saw that he needed privilege and power, however, he’d taken everyone he viewed as an impediment and had torn them up by the roots. Now there was an unwritten rule when it came to “the army’s fox”: Leave him alone. Don’t even go near him.

“However, Master Lakan has been away for the past year. It was because you’re all new here that none of you thought anything of using this room to meet a man.”

Onsou was right. All three of these women had become court ladies within the past year, and they didn’t know Lakan. Even if they had picked up on the unwritten imperative to steer clear of him, it must not have meant much to them. Otherwise they would never have joined the gawking crowd in his office.

And there had been no other new court ladies in the last year except for these three.

“So your opinion is that one of us killed him because of a little jealousy? I’m sorry to disappoint you, but how would I or any of us ladies with our skinny arms have killed this man and somehow made it look like a suicide?” Palace Lady No. 2 said. Nos. 1 and 3 immediately nodded their support.

“I’m glad you asked that. I’d like to consider that very question right now.” Lahan beckoned Maomao over. She gave him the world’s most disgusted look, so he was obliged to go to her instead. “Could you give me some help?” he asked.

“I am here strictly as an assistant to the medical personnel. What help would you have me give you?” Maomao replied as if reading off a script.

“Since she brought up a woman’s skinny arms, I thought this might be most credible if you did it.”

“Surely not, Master Lahan. I’m certain your own arms, so pale that they appear never to have seen the sun, and so willowy that they don’t look like they could hold anything heavier than a brush, would provide an ample demonstration.”

Maomao and Lahan set to glaring at each other.

“Aw, help the guy out, Niangniang.”

“If you don’t help him, this will never be over. Just do it already.”

Maomao shot Tianyu a dirty look, but she couldn’t refuse an instruction from Dr. Liu. She clicked her tongue. “Very well.”

“Toss the rope around the ceiling beam, if you would. Like you did earlier.”

“Uh-huh.” Maomao had dropped the pretense of politeness; she answered quietly enough that those around wouldn’t hear.

“Here. Rope.”

“Yep.”

Maomao tossed the rope around the beam so it dangled down, then knotted it. At the end, she made a noose.

“You think that rope is enough to hold such a big man?” Palace Lady No. 2 said with a sigh.

“Yes—but it would be difficult to dangle him with that alone. I have another rope here.” Lahan passed a second rope to Maomao, who looped it around the rafter like she had the first one. This one, however, she didn’t knot, but allowed it to hang freely. Lahan began to explain: “You make a loop in the end of this rope as well, then place it around the neck of the person you wish to ki— Maomao! Don’t put that around my honored father’s neck!”

Maomao had been making to place the rope around the sleeping Lakan’s neck. If she hated her father, there was nothing Lahan could do about that, but he didn’t want this to turn into another murder right while he was standing there.

“Niangniang, we’ve got the perfect thing right here!” Tianyu looked like he was about to pull the sheet right off the body, but thankfully Dr. Liu stopped him with another rap on the head.

Lahan was becoming very grateful indeed for Dr. Liu’s presence.

Onsou brought a sandbag. “Here, use this.” The tied-off part would make a nice analogy for a neck, the perfect place to put their rope.

The beams of the ceiling were just logs, used as is, which meant they acted like a pulley, making it easy to heave the rope up. Except...

“It’s not moving at all, is it?” Palace Lady No. 2 laughed.

Lahan’s adopted younger sister Maomao was not very strong. The sandbag, measured out to be as heavy as the murder victim, was at least twice her weight. With a moveable pulley, which would have lightened the load proportional to the number of pulleys involved, even Maomao might have been able to lift the sandbag. But the beam, secured in place, only acted like a fixed pulley, which didn’t change the weight of the object being lifted.

Maomao strained, clutching the rope close, but instead of lifting the sandbag, she was the one who started to float off the ground.

“You’re right, it’s not budging. Well, let me help,” Lahan said. He joined Maomao at the rope, pulling on it as hard as he could, leaning all his body weight back.

“I can’t do this...and you...know it!” Maomao grunted.

“Shut up and...pull...!” Lahan replied.

“You’re not...even...helping! It’s not...moving!”

“Shut up, I said!”

As they sniped back and forth, the sandbag slowly began to rise into the air.

“Huff, puff!”

“Puff, huff!”

After keeping it dangling for some ten or fifteen seconds, the two of them ran out of strength, and the sandbag fell back to the floor with a thud. Maomao and Lahan followed it, panting. Lahan was not a fan of physical labor, but his demonstration would be the most persuasive of anyone here.

“The b-body had scratches on the neck, indicating that the victim clawed at the rope,” Lahan said, catching his breath. “Which wouldn’t be present if he had jumped from the chair and been strangled in an instant.”

The faces of the three women stiffened at that.

“One of you couldn’t have managed alone, true enough. But two together, that would be possible, wouldn’t it?”

Lakan had said something about a white Go stone, but not which one. Meaning maybe it was more than one.

“Listen to the two of you gasp for breath. Perhaps two people could have killed him, but it doesn’t look to me like they could have hung him up,” Palace Lady No. 2 said, in spite of the strained look on her face.

“Indeed. Two people could only just barely lift him, so it would be difficult for them to stage the hanging. That would require a third person.”

The ladies’ expressions grew tenser still.

Lahan somehow managed to calm Maomao down and get her to help him heft the sandbag again. When they had it up to about the level of the noose they’d prepared earlier, Onsou got up on the chair and placed the other loop around the sandbag’s “neck.” Then they cut the second rope with which they had hung up the bag, and it dangled neatly from the rafters.

“Behold,” Lahan said. “You’ll note that I never once said there was only one killer. The three of you all did it together.”

With that, the three ladies broke down, weeping and kicking the floor in their frustration.

After a great deal of kicking and screaming, whatever had possessed the three women seemed to release them, and they quietly admitted their guilt.

They’d become friends because they had all joined the court ranks this year. None of them got along very well with the more experienced court ladies, which had only made their sense of solidarity stronger—so strong that they even used the same hair product, which might explain why all three of them had such lustrous black tresses.

Each woman had been sent to the palace with instructions from their families to find a good marriage prospect, and each woman had found Wang Fang. He’d approached each of the ladies separately, and you can imagine where it went from there.

Wang Fang had been under the impression that he had been juggling them quite capably, but a woman’s intuition is not a thing to be taken lightly, and the three-timer was soon found out.

They say that when a case of adultery is discovered, a woman’s hatred turns on the other woman—but in this case, the three women were already friends, and so their ire lighted on Wang Fang.

So it was that the trio conspired to kill him. Knowing that Lakan would soon be home, they invited Wang Fang to this office the day before the strategist was to return. Once one of them was laid out on the couch—the usual procedure in their trysts—and Wang Fang’s back was turned, the other two women jumped out of hiding and threw the ropes around his neck.

“Women are indeed terrifying,” Lahan said with a great sigh. If only Wang Fang had played the situation better. Maybe if he’d found some more-mature women who could have been more pragmatic about their games.

The only ones left in the office were Lahan, Onsou, and Lakan, who was still snoozing away. The folks from the medical office had gone back to work, and the ladies had been led away by the officials from the Board of Justice. The corpse was still there in a corner of the office, so Lahan continued to have Young Junjie busy himself with cleaning the adjacent room.

“I can’t believe it turns out Wang Fang was murdered because of a bit of jealousy. I thought for sure there must be some other reason,” said Onsou, sighing as he prepared a change of clothes for Lakan. The outfit was neatly ironed; no doubt he wanted to get his boss to put on fresh clothes before he met the Emperor.

“It might not have been just a bit of jealousy.” Lahan looked long and hard at the three ladies’ service records. In his mind, he began to see a number that united their histories.

“You think there might have been something else at work?”

“I would be very disturbed if there were, so I’m going to look into it.”

Even as he spoke, Lahan felt a pang of regret. There went the rest of his day. But then, he’d expected that something like this might happen. He would just have to carry on.

Chapter 5: Jinshi and the Report

The thick rug in which Jinshi’s knees were currently buried was stitched with a dragon, and the pillars to either side of him were carved with images of the same. The rug was flanked by high officials, all of them looking at Jinshi and the other returnees from the western capital.

Jinshi was bowing his head humbly.

“Raise your head.”

Jinshi did so, and saw something he had not seen in quite a while: the Emperor seated on his throne.

“You must be tired from such a long journey. Are you in good health?” the Emperor asked.

“I thank you for your kind concern,” Jinshi replied. Strictly speaking, he should have presented himself to His Majesty immediately upon returning from the western capital, but the Emperor had intervened to put the meeting off to the next day—that is, now. The exact timing of the meeting, after noon, was not a reward for a job well done so much as, one suspected, an act of consideration toward another of those there to make his report.

Lakan was diagonally behind Jinshi and looking sleepy. No one but he could be so unrefined as to yawn during an Imperial audience.

“Zuigetsu, have you lost weight?” the Emperor asked. He was the one man in the country who could use Jinshi’s true name. Other people referred to Jinshi as the Moon Prince—a usage that had developed largely in contrast to the Emperor himself, who during his heirship had been known as the Sun Prince or the Noon Prince.

“Not too much,” Jinshi replied. He wouldn’t deny it: He had lost some five kilograms, but there was no need to give the exact number. Jinshi was less concerned about his own weight than about the streaks of white that had appeared in the Emperor’s facial hair. The fact that he didn’t dye them or try to hide them suggested he had said not to do anything. Jinshi thought he felt a throb from the burn on his flank, which should have healed long ago.

An Imperial ruler had a great many jobs to do and a great many things to worry about. No doubt what Jinshi had done just before leaving for the western capital was something His Majesty worried about very much indeed. The thought that several of those new white hairs might be his fault left Jinshi with a clinging sense of guilt, but he still didn’t regret it.

Beside the Emperor stood his most important advisors. It was going on ten years since the Emperor’s accession, and there had been much change among them. Where Shishou had once been, Gyokuen now stood.

Jinshi focused and began his report. “Ka Zuigetsu humbly presents himself to the Imperial presence,” he said. As the Emperor was the only one who could call him by his real name, he was also the only one with whom Jinshi could use his real name.

Jinshi had already submitted a written report to His Majesty; now he went over only the broad strokes of his year in I-sei Province. He stole the occasional glance at Gyokuen—the man’s expression never changed, though he must have felt something about the death of his son.

“You’ve labored mightily, I see.” It was the Emperor’s voice, calm and quiet as Jinshi had always known it. Before, when he had made reports, Jinshi had often found himself summoned by His Majesty in the evening. They would drink wine, enjoy some snacks, and Jinshi could go into much greater detail about what had happened. He wondered if such an invitation would come tonight as well.

His plan this afternoon was to give the briefest of accounts, then make his exit before Lakan did anything. In spite of how much had happened over the last year, it could be boiled down to a few brusque lines and recited quickly enough. That would be all, and then they could get out of—

“Ah, yes, Zuigetsu, that reminds me,” the Emperor said when Jinshi had finished his report. “Perhaps you would visit the rear palace with me? It’s been so long.”

That was some invitation! A buzz broke out among the courtiers. It was well known that under the name Jinshi, the Moon Prince had once served in the rear palace himself, but there was a tacit understanding that it was not spoken of publicly. Jinshi felt as if the Emperor were playing some sort of prank on him.

The most appropriate thing for Jinshi to say at this moment was probably “Surely you jest, Your Majesty,” but having posed as a eunuch for some seven years, he found it hard to answer.

“S—”

“I’m only joking,” the Emperor said. “You must still be tired. You should spend the remainder of this day resting as well as you can.”

On the one hand, Jinshi was relieved; on the other, he was reminded that the Emperor was still someone around whom he couldn’t let down his guard.

A few other people made reports after that, and then the audience was over. At least Lakan had managed not to fall asleep during the proceedings, but the moment the end of the audience was announced, he sprang up and raced out of the throne room.

Jinshi walked into the hallway, breathing a sigh of relief. Basen and several bodyguards followed him. Baryou had been present at the audience as well, but on the verge of passing out from being surrounded by so many people, so Jinshi had sent him straight back to his room.

“I’m to rest, am I?” Now that he had properly greeted the Emperor, Jinshi would have to also pay his respects to his mother the Empress Dowager, as well as the heir apparent and Empress Gyokuyou. After that, perhaps he could rest. He might even rest well, as the Emperor said. He’d managed to get through all his paperwork on the voyage home, so he could kick back for the next few days.

“Will you return to your room, Moon Prince?” Basen asked.

“After I’ve greeted the Empress Dowager and the Empress. Er... If I could ask you to carry a summons?”

“Yes, sir?”

“Perhaps you could call Maomao for me?” Jinshi said, slightly embarrassed. Lakan was long out of sight, and he was at least confident that the strategist wouldn’t overhear him.

If Jinshi wasn’t mistaken, Maomao had some affection for him. Otherwise, she would never have given him that kiss—or so he wished to believe. And believing wasn’t necessarily easy, after she’d spent so many years dodging him.

On the ship, with Lakan nearby and so many eyes around, there hadn’t been any chance to progress their relationship. Now that they were back home, though, surely it wouldn’t be so bad to try to deepen their friendship a bit?

“You mean...the girl?” Basen asked with a puzzled tilt of his head.

“What? Is there a problem with that?”

Basen was not always the most perceptive of men, and Jinshi could understand why he hesitated to bring Maomao into Jinshi’s presence. However, he was going to have to get used to it.

“No, sir, but the medical staff are back to work today, so I thought she might be as well. Would you like me to call her right away?”

Jinshi almost gasped.

“Moon Prince? What is it? Why do you look so...shocked and doubtful?”

“Nothing, it’s just... I didn’t expect you to say something so on point.”

That made Basen frown. “My father cautioned me you might call Maomao before he went.”

Basen’s father, Gaoshun, had gone back to serving the Emperor personally. Jinshi nodded vigorously: It made sense. If this was coming from Gaoshun, then he wasn’t just worried about Maomao—there might be something else at work.

“Shall I call her, sir?”

“No... You know what, forget about it.”

Yes, yes of course: The Emperor himself had told Jinshi to rest, which was why he could take today off, but the others didn’t have such luxury. It crossed his mind to call her when she got off work, then, but perhaps summoning her on the very first day she went back to her job wasn’t the best idea. He was her superior, so she wouldn’t—couldn’t—say no, but he could just imagine the glare she would give him, as if to say What do you want when I’m so tired? That prospect held a certain appeal in its own right, but Jinshi quailed at putting his own desires front and center like that. He couldn’t allow himself to forget that he was a person of status.

“Hmmm. All right, could you call Maamei, then?”

“My sister? I don’t think that should be a problem.”

Basen’s older sister Maamei had remained in the royal capital. She was a canny woman; she would be able to fill Jinshi in on what had happened while he was away.

The Empress Dowager hardly seemed to have changed in the year since Jinshi had seen her last—but she seemed surprised by the change in him.

“You’ve lost so much weight,” she said.

“A great deal happened, you see...”

Funny, how she said the same thing as His Majesty. Did Jinshi look so haggard?

“Will you be visiting Empress Gyokuyou’s residence after this?”

“Yes, ma’am. I’d like to pay my respects to the prince and princess.”

His visit to the Empress Dowager was a brief one. She was his mother, but ever since he had entered the rear palace as a eunuch, she had become more distant. He felt like he should talk to her more, but somehow, he couldn’t do it.

There was a great deal Jinshi had done in secret from the Empress Dowager, and he often wondered if he should divulge all of it to her, or if he should take those secrets to the grave.