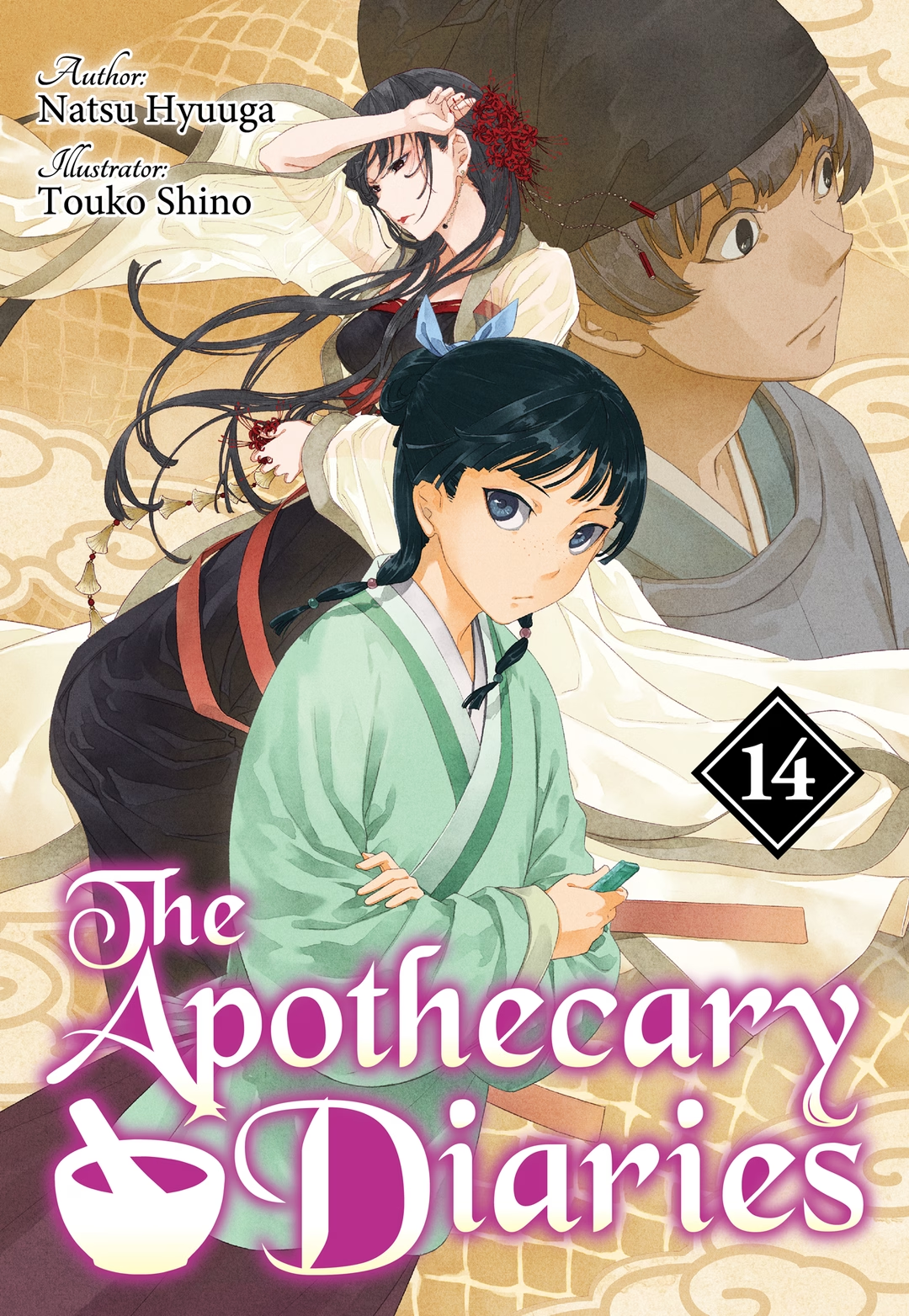

Character Profiles

Maomao

A former pleasure-district apothecary. After a stint in the rear palace and then the royal court, she now finds herself an assistant to the medical office. She used to be quite prickly, but she’s gotten much softer. She still retains her love of all things medicinal and poisonous, however, as well as her contempt for her biological father, Lakan. She’s finally started to seriously entertain Jinshi’s feelings. Twenty-one years old.

Jinshi

The Emperor’s younger brother. Inhumanly beautiful. His astounding looks are at odds with his straightforward personality, and the disconnect can cause misunderstandings. In his next life, he wants to be like Lahan’s Brother. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-two years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant. He has feelings for His Majesty’s former consort Lishu. Sometimes called a bear in men’s clothing. Twenty-two years old.

Chue

Wife of Gaoshun’s son Baryou. She acts silly, but she’s a member of the Mi clan and an expert at gathering intelligence. She sustains such serious injuries rescuing Maomao that she has to give up being Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting.

Gaoshun

A well-built soldier, he was formerly Jinshi’s attendant, but now he serves the Emperor personally. His wife, Taomei, is Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting, and has her husband thoroughly cowed.

Lahan

The younger brother of his older brother, Lahan’s Brother. A small man with round glasses, he’s nonetheless popular with women, for some reason. He has a head for numbers and knows how to swim with the tide.

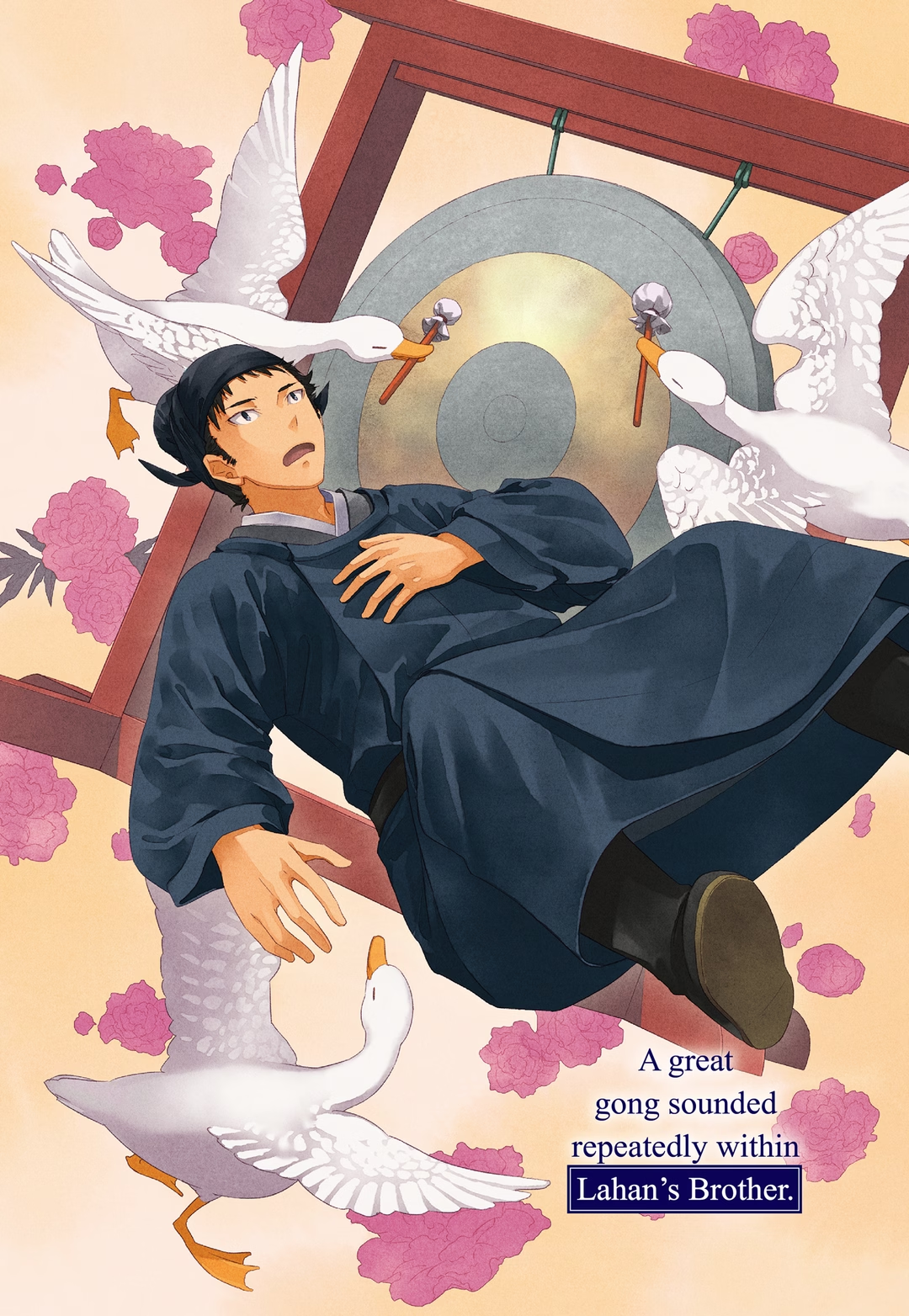

Lahan’s Brother

Lahan’s older brother. He’s actually a very capable person, but because he doesn’t realize that, he always seems to come up with the short end of the stick. He’d almost given up on having anyone actually call him by his real name. He has a gift for farming.

Lakan

Dotes on his daughter Maomao. Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle, he nonetheless holds the military’s highest title, Grand Commandant. Has a sweet tooth but can’t hold his alcohol.

Lihaku

A burly soldier. Sort of like everyone’s older brother. Hopes to buy out the courtesan Pairin’s contract.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting and former wet nurse. A real soft touch when it comes to Jinshi.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. She’s the mother of the Crown Prince, but because she comes from the western capital, many feel she’s not fit for her office. Twenty-three years old.

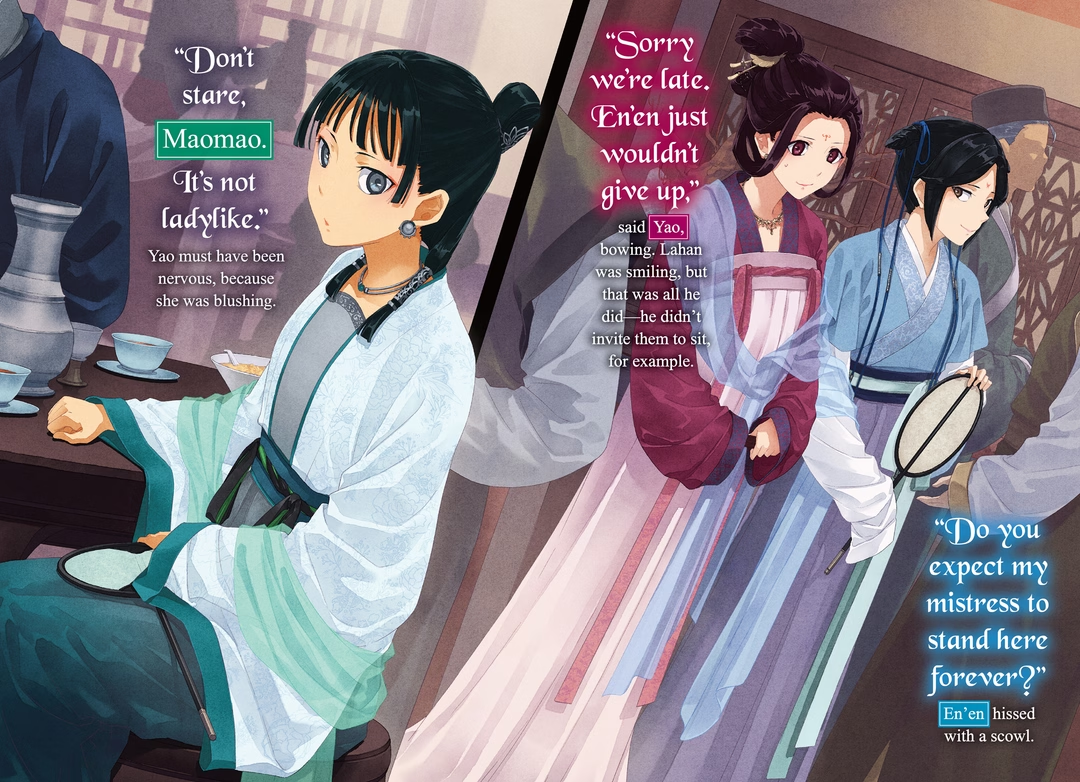

Yao

Maomao’s colleague and Vice Minister Lu’s niece. She may not know much about the world, but she’s trying to make it on her own as best she can. Has recently taken an interest in Lahan. Seventeen years old.

En’en

Maomao’s colleague, she’s also Yao’s lady-in-waiting. She lives for Yao, but she’s also a big part of the reason Yao isn’t off on her own yet. It bothers her no end to see Yao interested in Lahan. Twenty-one years old.

Tianyu

A young physician. A dangerous character who especially likes corpses and dissections. Supposedly a descendant of Kada.

Maamei

Basen’s older sister. Since Taomei and Gaoshun, her mother and father, were in the western capital, it fell to her to run Ma clan affairs. She can be a force to be reckoned with.

Dr. Liu

An upper physician. He and Luomen go way back. He imparts stern instruction to Maomao and her friends.

Dr. Li

A middle physician. He went to the western capital with Maomao and the others, and the stuff he went through there really beefed him up.

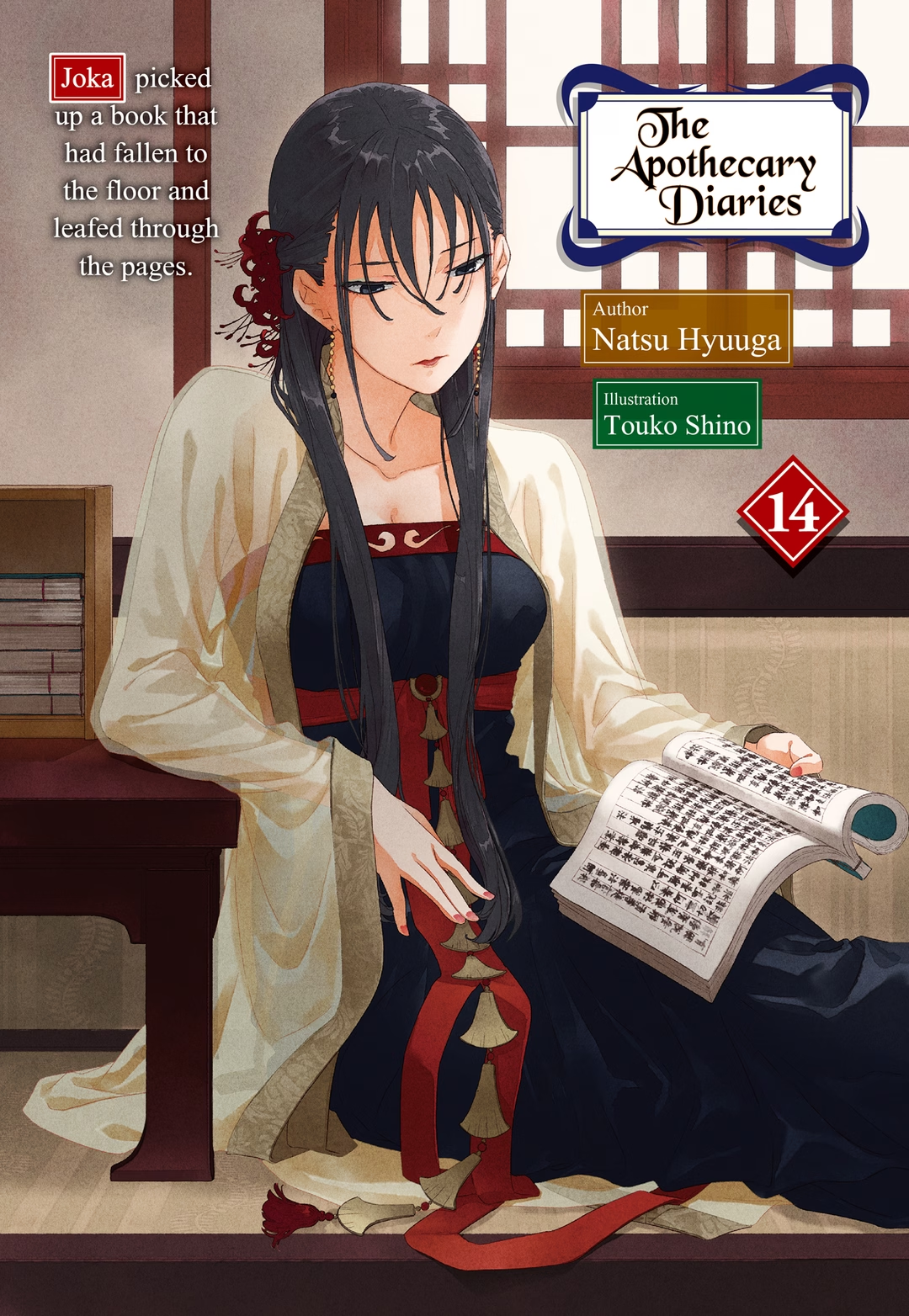

Joka

One of the Three Princesses at the Verdigris House. She knows the Four Classics and Five Books by heart. She possesses a broken jade tablet.

Pairin

One of the Three Princesses at the Verdigris House. An amply endowed woman with a gift for dancing.

Lishu

Formerly one of His Majesty’s high consorts, she hails from the U clan. She currently lives in a convent.

Ah-Duo

An old friend of the Emperor’s and one of his former high consorts. They had a son together. Thirty-nine years old.

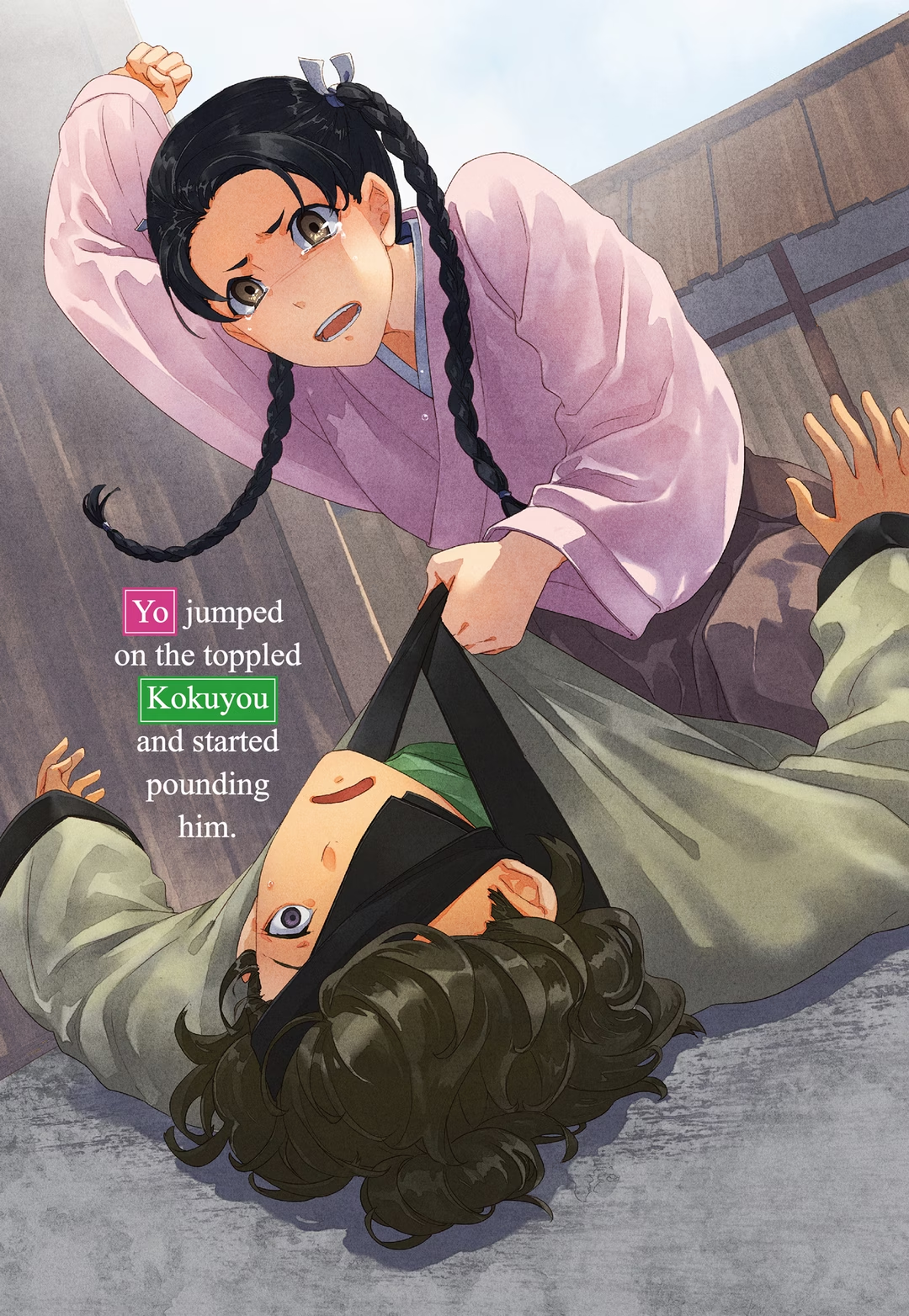

Kokuyou

A young man with smallpox scars on his face. He’s quite cheerful, and is an excellent doctor.

Chapter 1: The Meeting of the Named (Part One)

The day after she had visited Jinshi, Maomao found herself shaken awake by someone most unexpected.

“Maomao, wake up!”

“Huh? En’en?”

Maomao was tired from everything that had happened the night before. She hadn’t even managed to brush her teeth before sleep had taken her. Even her leftover food and drink still lay scattered about.

“Quick, get changed!”

“Why? Were we doing something today?” Still looking a bit vacant, Maomao got out some clothes. She was pretty sure she’d left today open, after planning to visit Jinshi last night.

“We weren’t, until the biggest thing happened and now I need you to come with me.” En’en looked deadly serious.

“Aren’t you going to ask if I’m free?”

“What are your plans for today?”

“Nothing much.”

At least, there hadn’t been.

“And you have work tomorrow, right?” En’en asked.

“Yeah...”

“Don’t worry, I took the liberty of telling them you’d be out.”

“What? Why?!”

Maomao was still trying to catch up with what was happening as En’en stripped her down and hustled her into her clothes.

“Where are we going? For that matter, where’s Yao?”

“My mistress is in the carriage outside. I’ll give you the details once we’re en route.”

In other words, she would not be taking no for an answer. Maomao could be surprisingly generous—but there were limits. Yao and En’en weren’t as bad as Lahan, but she still thought they were going a bit overboard.

“What if I refuse?” she asked. You had to know where to draw the line in your relationships. She couldn’t have En’en thinking she could just be pushed around.

“I have one good reason you won’t. Something you love.”

I’m not sure what she takes me for.

Maomao wasn’t going to remain pleasant and friendly forever. A lot had happened last night, and she was still tired. She was very eager to spend today in quiet relaxation.

“Here.”

En’en placed a thick book in front of her. It had a luxurious vellum cover decorated with pictures of flowers and bearing a title in a foreign language.

Maomao’s sleepy eyes snapped open and she swallowed hard.

“May I...open it?”

“Be my guest.”

“Hoooooohhhhhh!”

It was a botanical encyclopedia. Maomao was struck by the detail of the illustrations in spite of the fact that the book appeared to be printed. She’d never seen this book before, and many of the plants within were unfamiliar to her. Even if it took time to translate, the result would be well worth the effort.

“All right, that’s it for your test read!” En’en announced.

“Ahhh!”

En’en snatched the book away from Maomao, who was clinging to it and quivering.

“A few more pages! Let me see just a little more!”

“It’s a very valuable book—a trader seems to have stocked it on a whim, then sold it to a bookstore. I doubt we’ll see another copy for a good long while.”

“How much? How much do you want?! I’ll pay! I’ll give you my whole salary, and if that’s not enough, I’ll go into debt!”

“You sound like a desperate gambler,” En’en grumbled. Then she gave the book to Maomao. In exchange, she clasped Maomao’s wrist firmly, so she couldn’t get away. “I promise I’ll tell you everything. But for starters, would you join me in the carriage?”

“Absolutely!” Maomao said, hugging her encyclopedia close.

As promised, Yao was in the carriage outside the dormitory, dressed to go out. En’en sat beside her, while Maomao sat across from them. The carriage started off.

“So where exactly do you plan to take me?” Maomao asked Yao, still clutching her book.

“Maomao, do you know about the meeting of the named?”

“The meeting of the named?” She cocked her head.

“I can’t believe you,” groused Yao.

“Positively ridiculous,” said En’en.

“Why? What’s wrong?” Maomao asked, giving them an annoyed look.

“Didn’t you get a letter from Master Lahan?”

“Yes, and it made excellent kindling.”

Long pause from the other girls.

Lahan’s letters were inevitably filled with prying questions about how things were going with Jinshi and other obnoxiousness, so these days Maomao threw them right in the trash.

“No wonder you don’t know.”

“What is this meeting of the named? Is that where we’re going now, by any chance?”

“Correct,” said En’en, giving her an okay gesture.

“When you say ‘named,’ you must be talking about—you know. The Ma clan and the U clan and all those.”

“That’s right. It’s a meeting of all the clans who have been granted a name by the Emperor. We, however, are not among them. I’d love to go myself, but of course I’m not qualified. So we’re attending as your attendants.” En’en didn’t look thrilled by this premise.

“Why would you want to go? I don’t think it will be that interesting. Besides, even if you say I brought you, I bet they’ll just chase you right back out.”

Maomao didn’t think of herself as a member of the La clan, and didn’t expect to be admitted to some assembly she knew nothing about just because she’d shown up.

“This was Master Lahan’s condition. He said he would take us as long as we brought you.”

“Huh! So that four-eyed bastard is behind this.”

“Maomao.” En’en glared at her, reminding her not to use foul language in front of Yao. Unfortunately for her, Maomao was well used to being glared at by now and thought nothing of it—but she did decide to be more careful of her words.

“If it’s some kind of gathering, then I guess it’s very formal and everything. Are you sure I can just go bringing random people?”

“It doesn’t sound like it’s actually that serious. More of a meet and greet. It’s the perfect opportunity to make new connections, so sometimes people bring folks they want to introduce,” En’en said—proving her worth as a gatherer of information once again.

“But why does Yao want to go to this meeting of the named? Is there some sort of connection you want to make?”

“Exactly the opposite!” Yao said, and produced a sheaf of letters. The cloying stench of perfume immediately filled the carriage confines.

“That reeks!” Maomao exclaimed. “Don’t tell me... Are those love letters?”

“Yes, they are!”

Even for love letters, they were in bad taste—both in whatever perfume that was, and how much of it was on them. Maomao became acutely aware of how high-class the letters she ordinarily received were.

“May I?”

“Go ahead.”

Maomao took the sheaf. She knew it wasn’t polite to read someone else’s love letters, but the outrageous fumes gave her a bad feeling about this.

“Yikes...”

“Yikes is right,” Yao groaned. En’en nodded.

Love letters were usually rife with unctuous praise for the recipient, but this author talked extensively about how great he was and how prominent his family was. Self-confidence wasn’t a bad thing, but this was out-and-out narcissism. The handwriting was lovely, if nothing else—suggesting that the writer’s real skill was in finding a good scribe.

“While you were in the western capital, Maomao, somebody seems to have taken a fancy to my mistress. These letters have been arriving nonstop, and I can’t stand it!” En’en gave the letters a look of absolute contempt. It was such a familiar expression, it almost made Maomao nostalgic.

“He showed up when I was at work, and wouldn’t give up even after the doctors chased him out,” Yao said. “Even worse, it sounds like he’s told his family he’s actually seeing me already...”

It seemed the past year had been as eventful for Yao and En’en as it had been for Maomao.

I had no idea.

When Yao had been fretting about “relationships” the other day, maybe this was what she had meant.

“Huh! That sounds like a tight spot,” Maomao said.

“Don’t be flippant,” replied En’en, her face grim.

“Yeah,” said Yao. “And you know what? This moron said he’s going to go talk to my mother! I never imagined things would be worse without my uncle here!”

Yao’s father had already passed, leaving Vice Minister Lu as her guardian. When Maomao and the others had returned to the royal city, the vice minister had stayed behind in the western capital.

“My mistress’s mother isn’t the most worldly woman, and there’s a good chance she’ll swallow whatever this guy says hook, line, and sinker. She believes that a woman’s greatest joy is to marry into a good family.”

Maomao had only heard snippets about Yao’s mother before—evidently, she was Yao’s polar opposite.

“And if her mother is taken in by this guy, then Yao could be forced to marry him because the two families agree, huh?” said Maomao.

“I’d rather have one of my uncle’s matchmaking meetings!”

At the very least, Yao’s uncle seemed to choose potential suitors with his niece’s best interests in mind. He seemed to be a competent man himself, and unlikely to simply pass his niece off to some shady opportunist. The only thing was that Yao was eager to work, not get married, and she and her uncle never saw eye to eye on the subject.

“We want to go to the meeting of the named because the author of these love letters is one of them. We want to tell his clan leader to his face that my young mistress has no intention of marrying this clown. And we need these obnoxious letters to stop,” En’en said.

“Urgh...” Maomao groaned.

That’s reckless. It’s beyond reckless!

En’en was usually calm and rational, but when it came to Yao, nothing could stop her.

She was right that this love-letter guy was being ridiculous. But in Li, which particularly prized men, there was a distinct possibility that his ridiculous behavior would end up forcing Yao into a marriage. However, Maomao questioned the logic of gate-crashing the meeting of the named and confronting the guy.

She tried to read En’en’s expression. En’en was no fool; no matter how crazed she might be on Yao’s account, she would only be doing this if she thought there was some hope of success.

And Lahan is...well, Lahan.

He would never have agreed to bring Yao and En’en along if he knew their true objective. Even if Maomao offered a pretext for them to be there, Lahan was still a man who operated on a strict basis of cost-benefit analysis. He wouldn’t want to earn the ire of the other families.

The real question in Maomao’s mind was, why was he trying to get her to be part of this meeting?

“Is it possible the freak strategist is going to be at the meeting?”

“Well, yes...”

“You know what? I think I’ll go home.”

Maomao got up and made to jump out of the already moving carriage, but she was still clasping the precious encyclopedia.

“You’re welcome to go, Maomao, but I’ll have to ask you to leave that book,” En’en said, taking a firm grasp of Maomao’s sleeve.

Maomao didn’t say anything.

“Put the book down, please.” En’en didn’t let go of Maomao’s sleeve—and Maomao didn’t let go of the book.

In the end, Maomao sat back down, but she made sure to scowl as she did.

They bounced along in the carriage for a couple of hours until they found themselves at a large mansion not too far from the capital.

“That’s the meeting place. It belongs to the Chu, or Ox, clan.” Yao looked out the window. They could still just see houses in the distance, but near at hand there were rivers and forests, and even a farming village. A generous soul might have called it idyllic; a less generous one, countrified.

“Hmm,” Maomao said without much enthusiasm. She’d been woken up early that morning and frankly, she was tired.

“I’m going to explain now, Maomao, just so you know what’s going on,” En’en said. “The meeting of the named began long ago when the head of the Chu clan suggested everyone get together for a pleasant drink. Since it was their idea, the Chu host the meeting to this day.”

The law of You say it, you do it.

“Sounds like a real pain in the neck for their descendants.”

“According to the records, it used to happen every year. Then it was every other year, and now they host the meeting once every five years.”

“How cheap of them,” Maomao said, but admittedly, given how many people seemed likely to attend, doing this every year probably wasn’t feasible from a budgetary perspective.

“What’s more, this is supposedly the first time the La clan has participated in fifteen years.”

Presumably meaning since the freak strategist had become head of the family.

Maomao joined Yao in looking out the window. There were carriages ahead of and behind them, Lahan in the former and the strategist in the latter.

Stupid Lahan, paying for a whole other carriage just because he doesn’t want to ride with that freak.

There should have been plenty of room for two people in a single carriage. Normally Lahan abhorred waste, but it hadn’t stopped him this time. Maomao resolved to give him a piece of her mind when they got out of their respective rides—though she would have to dodge the strategist while she did so.

The carriage stopped in front of the mansion. A crowd of other guests was already there, along with any number of ornate carriages.

I guess this is a fine estate, as far as it goes, Maomao thought. In the time she’d spent among the noblest of the noble, she seemed to have become rather picky. She was on the verge of comparing this place with the Emperor’s palace.

Not a habit I want to be in.

In truth, this estate was of a quality boasted by only a few of the richest merchants in the capital, yet Maomao found herself unable to be particularly impressed by it. So instead of worrying about how ornate the house was, she started to evaluate whether it displayed good taste.

A flagstone path met Maomao and the others as they walked through the gate, and gardens spread out on either side.

The building itself is pretty old, but it’s been kept up well, so it doesn’t feel old.

It was also very large, suggesting that maybe it had been built specifically to accommodate these meetings. It contained a series of similar-looking rooms, and Maomao could see servants leading guests to different chambers. There was no ostentatious furniture, but there were detailed carvings on the posts and walls. The house was very open and probably got excellent airflow. The architecture seemed to prioritize summer livability.

A stand of bamboo in the garden gave the place an elegant atmosphere. Bamboo was far hardier than it looked, and if left to its own devices would sprout up just about anywhere—including straight through the floor—so it took a lot of minding. There were no piles of fallen leaves around, showing that the gardeners were doing their jobs.

The garden had been divided into areas evoking different seasons, and at the moment the peach trees were in full bloom. If only a rain shower would come through, it might be even more beautiful. The rest of the garden was a riot of colorful flowers, yet it was clear that they’d been planted with some thought for overall visual harmony.

“Maomaaaaao!” cried the freak strategist, tromping toward her the moment he got out of his carriage. Maomao gave him a very annoyed look, her hackles rising as if to say Don’t get any closer. She’d meant to hide behind Yao and En’en and just ignore him, but then someone caught her eye. It was Lahan’s Brother.

“Elder Brother!” she said.

“Yes, it’s me,” he replied bluntly.

“Lahan’s Brother!”

“Who are you calling Lahan’s Brother?!”

Apparently, Lahan’s Brother would permit “brother,” but no more.

“I see you’re home safely, Lahan’s Brother,” Maomao said. She hadn’t seen him since he’d gotten back, and she was relieved—after all, she was part of the reason he’d had so much trouble getting home. She’d plum forgotten to tell him they were leaving. She’d been dealing with a lot at the time, but still.

“Elder Brother” gave Maomao a good glare, then looked pointedly away.

He’s mad.

Should she point out that it was such a sullen-little-girl thing to do that it wasn’t intimidating at all?

“Maomaaao! They say the food at this inn is really good. Let’s eat plenty!”

The freak strategist seemed to be in very high spirits. This, Maomao presumed, was why Lahan had wanted her here.

“Come on, let’s go. They should already have rooms prepared for us.” Lahan clapped his hands, urging them all inside. Even the three carriage drivers came along. They were all large men, since they doubled as bodyguards.

Maomao was a little nervous, because she’d been expecting Sanfan to come along, but even Lahan wasn’t willing to stoke that fire further. She didn’t want to think about a standoff between Sanfan and Yao. Most importantly, though, if Sanfan had come, there wouldn’t have been anyone to watch the house back in the capital.

“We’re not kids. Don’t summon us with your little clap-clap,” Lahan’s Brother snapped. In Maomao’s opinion, it was understandable—since some of their number were emotionally children. Lahan’s Brother kicked a pebble at his feet, another girlish gesture.

There was a line of servants in front of the entryway, all bowing their heads. “Welcome, welcome!” said a plump, jovial older man who came out to greet them. He must have been easily 110 kilograms, and his cheeks glistened. He was no servant, but the master of the house.

“Ahh, to have the La clan here! The records tell me it’s been some fifteen years since we saw you last. I am Chu Ki. I’m technically retired—already handed the clan headship over to my son, you see—but it still behooves me to be hospitable to our guests. Please, make yourselves at home.”

The jovial old Chu Ki extended his hand to Lakan, but Lakan simply stared around the house and dug around in his ear with his finger.

There was an uneasy moment of silence, until Lahan took the old man’s hand instead. “We humbly thank you for your invitation. I’ve heard that our family participated in this meeting many times in my grandfather’s day. We hope only that we might spend a few profitable days with everyone here.”

“Ha ha ha! Sir Lakan is a rather birdlike character, isn’t he?” The old man didn’t appear especially bothered, skipping right over Lakan and clasping Lahan’s Brother’s hand. He even went over to offer a polite hello to Maomao and the other women, but didn’t go so far as to shake their hands. “I would so love to shake the hands of such fine young ladies, but we can’t go provoking unwanted jealousy! Let me decline the honor, though I weep for it!” he said.

The Chus’ ancestor had apparently been quite a charmer, and his descendants seemed to have inherited his gift of the gab.

“Now, come! There’s a room all ready for you to relax in. Take it easy and enjoy yourselves this evening.”

Servants led Maomao and the others from the front door through a hallway that ran beside the courtyard garden. The guests who had already arrived were enjoying tea in an open-air pavilion or feeding the carp in the pond.

One of them noticed Maomao’s party coming down the hallway and turned toward them—then promptly paled and hid behind one of the pavilion’s posts. Why? It could easily have been either the freak strategist—who was idly watching a butterfly flutter by—or Lahan, who was walking along with a very forced smile on his face.

“Yao,” Maomao said, glancing at the other woman.

“Y-Yes?”

“I understand your anxiety, but could you please not grip my arm quite so hard?”

Because En’en is glaring at me and it’s scaring me.

Somewhere along the line, Yao had taken a very firm hold on Maomao’s hand.

“Oh!” She quickly let go and walked a few steps ahead, looking awkward. She seemed to be nervous, in her own way.

One thing’s for sure: The freak strategist does make a good deterrent.

In the same way insects avoided malodorous plants, this man helped keep bugs at bay. The catch was, those using such plants as bug repellent had to put up with the stink themselves.

The servant moved down the hallway at a good clip. The group passed door after identical door of what were evidently guest rooms, until they found themselves in a completely separate building.

“Here you are,” the servant said.

“Here, sir?” Maomao asked. This was obviously nothing like the rooms housing the other clans. It felt less like special treatment and more like quarantine. When something stinks, you put a lid on it.

“Ah, a separate building, yes. Here my honored father won’t cause trouble for the other guests if he starts singing or dancing, and even if the place catches fire, it won’t spread to the main house.”

Lahan’s visions of what might happen were troubling, but one had to admit they couldn’t be ruled out. The freak strategist was a man with a history of trying to smash his way into the rear palace, after all.

“Which room should my young mistress use?” En’en asked. The annex had only one living room and three individual chambers.

“I wanna stay with Maomao!” said the freak. He was already lying back on the couch in the living room like he was in his own home.

“You, Honored Father, are the eldest, so you get a room to yourself,” said Lahan, deflating the old fart.

Lahan’s Brother looked all around like a true country mouse. “Maybe the three women could share the largest room,” he suggested.

“Fine by me,” Maomao said.

“Yeah, I don’t see a problem with that,” added Yao.

“Yes, that’s fine,” En’en said.

There would be no room for their three bodyguards, but the living room was big enough that it should serve.

The party split up into their assigned quarters and put down their luggage. There were four beds in the room, with freshly changed sheets that smelled lovely.

I guess the assumption is that people are going to stay overnight.

Reasonable enough; the banquets probably went into the wee hours.

“This is pretty laid-back for a formal meeting,” Yao observed.

“They said there’s going to be a meal in the banquet hall at noon, so we should get changed,” En’en said. She produced some clothes for Yao from the luggage. There was also a complete makeup set, along with a batch of hair sticks so heavy it jangled.

“En’en, one question,” Maomao said, raising her hand.

“Yes, Maomao?”

“You seem very...into this.”

“This is a chance to formally present Lady Yao to a whole host of people from famous houses. There can be no shortcomings in her outfit.”

“Don’t you think pretty much any outfit would do? You’ve made me change clothes so many times since last night that people hardly knew it was me. It was awful!” Yao complained.

En’en was a supremely competent lady-in-waiting, but she seemed to be missing one thing.

“If you dress Yao up too nicely, won’t that just make more people want to marry her? What’s the point of getting all fancied up?” said Maomao.

Yao’s whole reason for coming here was supposedly to turn down the man who wanted to marry her. Dressing up would only emphasize what a lovely young lady she was and what a fine family she came from—and wouldn’t that attract the wrong kind of insect?

En’en paused for a long moment, looking from Yao to the outfit and back, obviously agonizing about it. En’en was very competent, yes, but when it came to Yao she could go a bit crazy. After long deliberation, she removed one hair stick from the bundle with which she planned to decorate her young mistress.

“You ought to dress up yourself a bit, Maomao,” she sniffed.

“This is plenty.”

Maomao’s ordinary outfit was easy to move in and kept her cool. Even if it probably did make her look like one of the servants to everyone else.

Still...

That old man earlier hadn’t greeted the bodyguards but had nonetheless said hello to Maomao, En’en, and Yao. He certainly hadn’t thought Maomao was a servant. He’d probably looked into her background ahead of time.

Maybe he’s more than just a charmer.

Maomao scratched her chin thoughtfully.

“I have clothes here for you too, Maomao. There’s no need for you to say something like ‘As you can see, I’m not in a fit outfit to present myself before everyone else, so you all go enjoy the banquet without me’ and hide in your room—so don’t worry!”

That left Maomao silent.

“Come on, it’s almost time! Let’s get ready,” En’en said. She shoved the outfit at Maomao and helped Yao change.

“What a pain,” Maomao grumbled, but decided to get changed. It didn’t look like En’en was going to give her any choice.

Chapter 2: The Meeting of the Named (Part Two)

The seating arrangement at the banquet was most unusual.

“Ah...about the size of one field, I see,” remarked Lahan’s Brother. Apparently that was how he perceived the size of the place. For a single room, it was quite large. In the center was a big, circular stage, with round tables arranged all around it.

Yao and En’en were still getting ready, so they were back at the annex. The freak strategist had been asleep on the couch, so they’d left him there. Maomao wasn’t entirely comfortable with that, but between the bodyguards and the freak himself, she figured the girls wouldn’t accidentally get caught up in anything they shouldn’t. Besides, En’en was relatively adept at handling the freak strategist. Maomao hoped—wanted to believe—that there wouldn’t be any problems.

So it was that she, Lahan, and Lahan’s Brother arrived at the banquet hall first.

“The point is to keep people from feeling that some seats are superior to others,” said Lahan. Despite being a pathetic little creature, he was dressed well, raising the question of whether clothes could indeed make the man. His outfit was plain at first glance, but the cloth was excellent stuff—very Lahan-esque. “It can’t be easy to do the seating chart with all the bigwigs who show up here.”

Maomao was thinking the same thing. It would be hard for those seated behind the stage not to feel they were being snubbed. Making the stage circular deftly obscured what was the front and what was the back—a clever move. Admittedly, there were still two rows of tables, but the front row was for clans with zodiac names, while the back was for clans with other names, an arrangement no one was likely to object to.

“S-So where do we sit?” asked Lahan’s Brother. He was tall and handsome, at least taller and handsomer than Lahan. He had his looks going for him—but mostly so long as he just stood there. “Gosh, there’s a lot of people here,” he said.

“Brother, try to act like you belong here,” Lahan said in exasperation. The way his older brother stood and stared made him look like the quintessential tourist in the big city.

The venue wasn’t even half full yet. A few tables with no one sitting at them stood out—among them two marked with the characters Ma and Gyoku, respectively.

There were about twenty tables, and each sat eight people, but most of them wouldn’t be completely filled. Interestingly, the tables with guests showed a certain similarity in their compositions.

There’s always someone who looks like a retired old guy and then some youngsters.

Even more strikingly, the ratio of men to women among the youth was about equal.

Maomao and the others sat at the table marked La.

“Hey,” said Maomao, elbowing Lahan.

“What?”

“This wouldn’t happen to be one big matchmaking get-together, would it?” Maomao narrowed her eyes.

“Not exclusively, but that’s part of it. People bring the most talented sons and most beautiful daughters from their branch families, and more than a few are looking to foist them off on other clans. It’s not all blood relatives either; some people bring friends who want to make a match with a well-known household. Not that everyone here is a winner, of course. Fun fact—my own mother and father met at one of these meetings.”

Father: For once, Lahan meant his biological father.

Isn’t that a pretty risky business? Maomao thought. She was beginning to think that bringing Yao and En’en had been a mistake, and she wasn’t alone.

“In principle, this place is completely against what Yao is after,” Lahan said, and he sounded tired. If Maomao had refused to come with, he certainly never would have allowed them to be here.

Lahan was quite cold toward Yao, and Maomao understood why. Yao didn’t seem to realize it, but there was something blossoming within her, a feeling for Lahan that hadn’t yet resolved itself into either love or simple admiration. To have affection for someone else, only to have that very affection breed contempt in them, was a disappointing business.

She should do herself a favor and just give up.

Yao, however, didn’t see that. She had a very grown-up body, but her heart was still more that of a girl. It hurt to watch her cling to Lahan for want of knowing what else to do, but sometimes becoming an adult meant going through those experiences.

Lahan’s inept at the strangest times.

Maomao thought it was partly his fault for not understanding how to handle a young woman in the throes of adolescence. To Yao, with her fierce competitive streak, his actions were like pouring oil on a fire.

Now, then. Lahan had confirmed that this gathering was partly about meeting prospective partners—but what else might be going on?

“What else happens here?” Maomao asked.

“Clan heads-to-be meet each other and form friendships; there are business negotiations and political wrangling. All things my grandfather loves—I hear he used to participate in every meeting.” Lahan glanced around the venue, which included other separate rooms, distinct from the guest rooms. “There are also rooms where people can take a break, each of them carefully soundproofed. Practically an invitation to have your secret conversations there.”

That was presumably Lahan’s real objective. Well, Lahan’s Brother might be there to find a wife, possibly, but he should have known that the moment he appeared in the company of the freak strategist, the chances of that were practically nil.

“You’re not involved in anything underhanded, are you? You promised you would introduce me to a nice girl!” Lahan’s Brother said, cornering his younger brother. So that was how Lahan had convinced him to attend.

“Brother, please. You know I only want to look at beautiful things.”

“I know. But something about you smells fishy.”

“He’s right.” Maomao agreed with Lahan’s Brother.

“You’re working some kind of con.”

“Lulling him into a false sense of security by pretending nothing is amiss, then springing some sort of marriage swindle,” Maomao added.

“I can’t believe you,” Lahan’s Brother went on. “I hope all the boats with all your investments sink!”

“I would feel bad for the sailors,” Maomao said, feeling a pang of sympathy for the innocent shipmates.

Lahan’s Brother backed down a bit. “Then I hope you stub your little toe on the corner of a cabinet!”

“I hope you get hangnails on every digit you have,” said Maomao.

“Brother! Maomao! Why are you better friends with each other than with me, your actual sibling?!”

Lahan looked put out, but Maomao didn’t think of him as her older brother. Lahan’s Brother himself was more like a brother to her.

“Would you like something to drink?” asked their server. Each table had its own servant, who was dedicated to making sure they lacked for nothing.

“Tea for me,” said Lahan.

“Do you have wine?” Maomao asked, eyes shining.

“In moderation!” Lahan snapped.

“I’ll be moderate!”

So it was tea for Lahan, fruit wine for Maomao and Lahan’s Brother. The wine had herbs steeping in it to help the digestion; it was evidently meant to serve as an aperitif.

“I wonder if they have anything to go with this. I hope it’s something sweet. You can step away until you come to tell us it’s ready,” Lahan told the servant.

This was partly a strategy to get the freak strategist to eat, but also a way of getting the servant to abandon his post and leave them alone. Once he was gone, Lahan began talking quietly.

“You know why we’re at this banquet today?”

“Is it about a woman?” Maomao asked, eyeing him coldly.

“Isn’t it to find me a wife?” asked Lahan’s Brother, who was still hoping for that elusive introduction to a nice girl.

“I’m looking to get on good terms with a particular personage.”

“I knew it was about a woman.”

“No, no it’s not. Look diagonally to your right.”

Maomao’s eyes darted in the indicated direction, though she didn’t deign to turn her head. There was a table with five people at it: a man who was quite old, with a middle-aged woman who appeared to be his minder and three younger people—a young man and woman, each in their twenties, as well as a boy, still probably around ten years of age. The table was emblazoned with the character U. Former Consort Lishu’s family. Lishu herself, living in seclusion, was of course not there.

“Wow! Look at that ancient sack of bones,” said Maomao.

“The term you’re looking for is honored elder,” Lahan told her.

“What do you want with the U clan?”

The U, Maomao had heard, were very much on the outs at the moment, what with Lishu’s seclusion and the things her father and half-sister had done. Maomao couldn’t imagine why Lahan would be interested in them.

“Now look diagonally to the left.”

Maomao’s eyes slid in the new direction, where she saw a woman of some years. She was with a man who appeared to be her aide as well as five younger men and women. Their table said Shin, “dragon.”

“Get a load of that old hag!”

“Honored elder! The same term will work!” Lahan sounded like he was reprimanding a child.

“So what do you want with the, uh, honored elders of the U and the Shin?”

“There’s been bad blood between those two clans for some forty years now. They used to get along very well, but the previous heads of the clans had a huge falling out, and now they keep their distance from each other.”

“And the two elders are the former heads of the clans?”

“Not quite. The woman is the wife of the former head of the Shin clan. I suppose we could call her the mistress now. I’m sure she’s well acquainted with the situation, though. The U man was the former head of the clan, but thanks to what his son-in-law did, he had to come out of retirement and resume the headship.”

Lahan munched on some fruit that sat in the middle of the table. Lahan’s Brother was sipping his fruit wine and pondering whether he might be able to make some himself.

“What caused this fight, do you know?” Maomao asked.

“The alleged theft of a family heirloom. It was supposedly the U who did the stealing, and the Shin who were stolen from.”

“Yikes. Sounds like a real headache.” And it had been forty years ago! That heirloom was long gone.

“Call me cold,” Lahan’s Brother said, speaking quietly like Lahan, “but why do you care if a couple of other families are having a spat?”

“Normally, I wouldn’t. At the moment, however, the U are weak. And a lot of unsavory people are trying to take advantage of that.” Lahan broke it down nice and easy, as if helping a child understand. “It hasn’t been that long since the Shi clan was destroyed. We wouldn’t want to see another named clan disappear so soon, would we?”

“So you want to patch things up between them and strengthen the U clan? I don’t think it’s going to be as easy as that—and besides, what makes you think you can crack a forty-year-old case?”

Maomao nodded her agreement with Lahan’s Brother’s analysis.

“Again, I normally wouldn’t. But it so happens the Shin are still searching—they believe the heirloom may yet be found. Just imagine the favors they would owe me if I were the one to find it!” Lahan’s eyes glinted unpleasantly behind his glasses.

“So that’s what you’re really after,” Maomao said, taking a sip of wine.

“Something else bothers me too. You remember the incident of the hanging in my honored father’s office?”

“What’s that got to do with anything?”

“The culprits turned out to be three palace women. What if I told you all three of their families had connections to the Shin clan?”

At that, Maomao was silent.

“Please help me, O my little sister!”

Maomao still didn’t say anything, just sipped her wine.

“I know it won’t be easy to solve a case from four decades ago, but I have you, my brother, and my father. I would have liked to bring great-uncle Luomen along, but it didn’t work out. They do say three heads are better than one—surely you’ll be able to figure something out?”

Maomao was well aware of how the U clan had ended up where they were now, and it didn’t make her feel very good that the actions of a wayward son-in-law and his compatriots had weakened the main family.

While this conversation had been going on, Yao and En’en finally arrived.

I thought she said something about taking the minimum amount of time necessary.

Yao was thoroughly dressed up. Not overdressed, of course—this was En’en’s work, after all—but outfitted in a way that would show anyone who bothered to pay attention that care had been taken with her clothes, hair, and accessories.

En’en had likewise helped Maomao pick out her clothes, and they were excellent. She would have made a superb lady-in-waiting—if she would ever give a thought to serving someone other than Yao.

She’s going to end up making herself the one everyone wants for a wife.

A husband’s display of class often sprang directly from his wife’s good sense. No decent household wanted a bride with bad taste.

“That’s enough fiddling with my hair,” Yao was saying.

“Oh! Just one more little adjustment! Please, hold on...”

En’en was still holding a comb and some camellia oil. The freak strategist followed them in, a vacant look on his face. Each time he started to wander off in a random direction, one of the bodyguards would pull him back where he belonged.

It’s not easy looking after him, huh?

This was not a work occasion, so instead of his usual competent subordinates, it fell to the guards to keep an eye on the strategist.

“Sorry we’re late. En’en just wouldn’t give up,” said Yao, bowing. Lahan was smiling, but that was all he did—he didn’t invite them to sit, for example.

No more welcoming than ever, I see.

Lahan always liked his relations with women to be very clear, which was why it was such an issue for him that an aristocratic young lady like Yao had taken an interest in him. Maomao agreed that it was important that men and women not lead each other on, but even she felt Yao was being treated poorly.

“Do you expect my mistress to stand here forever?” En’en hissed with a scowl. Lahan was definitely on her shit list.

Yao, however, didn’t appear to mind; she just kept smiling. She was, it was fair to say, the kind whose resolution only grew in the face of opposition. It remained an open question whether her feelings for Lahan were of romance, respect, or merely curiosity in a man of a type she had never met before.

“Sorry. I think this is what you’re supposed to do at a moment like this?”

It was Lahan’s Brother who took the initiative, pulling out chairs for Yao and En’en.

“Thank you very much, Lahan’s Brother,” Yao said, taking a seat.

“Ha ha... Ha ha ha...” He laughed feebly. Evidently he was already “Lahan’s Brother” to Yao as well. En’en gave him a polite nod of the head as she took her spot.

“It’s almost time,” said Lahan.

The other families were all seated—including the Ma clan, whose table was full. Maomao could see Basen and Maamei among the attendees.

So that’s why he wasn’t there last night, she thought. She was sure Chue would have been eager to attend a party like this, but she was nowhere to be seen. Maybe with her physical infirmity she had to make herself scarce.

“Maomaaaooo!” The freak strategist shoved Lahan out of the seat he occupied beside Maomao and sat down. She gnashed her teeth at him intimidatingly. The strategist went on in a tone like he was placating a cat, “You look adorable in that outfit! But your hair looks so lonely—won’t you put one of my hair sticks in it?” He held a hair stick out to her.

“Yikes...” Lahan’s Brother gasped, and Lahan averted his eyes. The hair stick was a silver piece carved in the likeness of a sword around which curled a dragon. From the chain dangled a lavender crystal skull.

The sword, the dragon, the skull. What was he, a preadolescent boy?

“A dragon and a skull together—isn’t that a bit disrespectful? And I’m not sure the purple crystal helps,” said Yao, very serious. Maomao and the others all gave quick little shakes of their heads, and although there was clearly more that Yao wanted to say, she refrained.

Lahan’s Brother could be heard to remark, “I thought that thing was awesome, back in the day,” but Maomao pretended not to hear him.

“I have to refuse, on the grounds that it’s disrespectful,” she said quietly.

“Oh. I see,” said the freak strategist, deflated.

“I won’t wear it. But I will take it,” said Maomao, taking the hair stick from him, at which he lit up.

I can melt it down and sell the metal.

It was at least made of good stuff. Selling it was the same solution Maomao had resorted to for all the other accessories the freak strategist had brought her.

“Maomao! What kind of hair stick would you like?” the strategist asked.

“One of pure gold. Absolutely no adulterations.”

“Oh, Sister, please don’t drive my household any further into debt.” Lahan looked genuinely bereaved. How far in the red was his family?

Their discussion was interrupted by the ringing of a gong. The old Chu man got up on the stage in the middle of the room—it was time to start.

“Thank you, everyone, for being here with us today,” he said, smiling and turning all around. It might look somewhat silly, like he couldn’t settle down, but in a room with no “high end” and no “low end,” it would have been rude to offer his greetings in only one direction.

“As it’s been five long years, you’ll notice some things are different from the last time we were together.”

Like that the Shi clan are gone and the Gyoku clan are a lot more numerous.

Neither Empress Gyokuyou nor Gyokuen were at the Gyoku table; instead, there were just two people, a man and a woman in their thirties. Maomao figured they must be Gyokuen’s children. She peered around, wondering about all the other seats.

“Don’t stare, Maomao. It’s not ladylike.” Yao must have been nervous, because she was blushing.

Jovial Old Chu turned out to be long-winded. He was so careful to be thoughtful to his guests; Maomao only wished his care had extended to the length of his speech.

The freak strategist, perhaps satisfied by the matter of the hair stick, was busy with the snacks Lahan had requested for the purpose. He was more or less behaving himself, but behind him, his guards were keeping a close eye on him.

Won’t this guy ever shut up?

Old Chu prattled on and on; the only silver lining was that food began to appear even as he spoke. In the center of the round table they placed a roast duck. Chopped jellyfish with sauce, century eggs, and stir-fried bamboo shoots followed.

Duck...

Maomao stole a glance at the Ma table and saw Basen looking deeply conflicted. No doubt he was thinking of his pet duck back home.

“I do feel a little bad for it, but that’s life. It is livestock, after all,” said Lahan’s Brother, with calm acceptance. The servant had carved the duck, and Lahan’s Brother was enjoying some with gusto.

Maomao tried to take the bottle of huangjiu that was on the table.

“No,” Lahan said and snatched it away.

“Why not?” Maomao demanded, giving him a dirty look.

“You have work to do, Maomao, so you must drink in moderation.”

Then Lahan asked the servant to clear away all the alcohol on the table. Only the barely alcoholic fruit wine remained.

Maomao ate her meal in sullen silence.

It turned out Old Chu wasn’t the only elderly gasbag in attendance. After his speech was over, some retiree from one of the other clans started in on a winding history of Li. It was an entire half hour before he was done, and by then Maomao’s stomach was full of food.

“And now, everyone, please relax and enjoy yourselves.”

How they had waited for those words! The entire venue burst into riotous applause.

The old folks left the stage, and a dancing girl in a gorgeous outfit took their place. She expertly manipulated her billowing sleeves in a dazzling display. In line with the casual atmosphere of the meeting, the music seemed aimed at the young people, bright and cheery, and gilded the conversations nicely.

The youngsters got up out of their seats and started visiting with each other. Some chatted with the prettiest girls they could find; others paid their respects to the heads of other clans or introduced acquaintances to each other.

The elderly leaders stayed in their seats and smiled at the goings-on, but there were a few youngsters—perhaps favored by the elders—who received greetings from the elders instead of the other way around.

Several people could be seen scurrying off to the private conversation rooms—youth being youth, cliques seemed to have formed quickly.

Now, as for Maomao and her table...

“No one’s visiting us, huh?” Lahan’s Brother said, sipping his soup.

“If you’re tired of waiting, you’re welcome to get up and walk around, Brother.” Lahan showed no sign of getting up himself; he still wanted to enjoy a leisurely meal.

“That’s not really what I mean,” said Lahan’s Brother. He was possessed of something resembling common sense, and it bothered him that they alone seemed to be a table of pariahs.

“Isn’t this meal delicious, En’en?” said Yao.

“Yes, mistress. I’ll have to recreate it for one of our dinners.”

Yao and En’en seemed to have expected that no one would visit their table, and it didn’t worry them. Maomao was likewise enjoying the food, but she hadn’t forgotten why she was really there.

“So, where’s this guy who was making passes at you, Yao? Is he here?”

“No, but his clan is.”

“Which one is it?”

“The Shin.”

You’ve got to be kidding.

Maomao stole a glance at Lahan. His eyes behind his glasses were narrowed, but she thought she saw a gleam that heralded a serious headache.

“I’d like to go talk to them now,” said Yao, standing up.

Lahan, Maomao, and Lahan’s Brother all panicked. Yao and En’en hadn’t heard the story of the falling-out between the U and Shin clans. Meanwhile, Lahan’s Brother wasn’t involved, but he knew how to read a situation. He really was a good guy.

“Just hold on a minute. Please,” Maomao said, exchanging a look with Lahan.

Should we tell her about the Shin and the U?

The thing was, En’en might listen, but Yao could be headstrong. Deciding it was better not to stick her neck out, Maomao heaved a sigh. “Do you have any connections at all to the Shin clan?”

“No,” Yao said uncomfortably.

“I thought not. Which means, if you ask me, that it would be considered very rude for you to simply walk up to the clan’s most important members and start talking to them.”

“I know that.” Yao pursed her lips, but only a little.

Maybe she’s gotten just a bit more mature in the year since I saw her last?

Maomao looked to Lahan again. He had probably already grasped what was going on with Yao and En’en.

“I was about to talk to the Shin about a matter of business,” he said. “Let me begin the discussion. I understand how eager you are to resolve this problem that’s besetting you, but you two are fundamentally outsiders. If you go poking your nose in where you’re not welcome and leave my family in the red, I’ll boot you out of our house so fast your heads will spin.”

It might have sounded cruel, but Lahan was absolutely right. Yao bit her lip, and En’en wore an expression like an avenging demon’s.

En’en, meanwhile, hasn’t changed at all, thought Maomao. She was actually starting to worry that if they didn’t do something about En’en, Yao would never be able to spread her wings. Wasn’t there anyone who might be able to lower En’en’s hackles?

“Here’s what’s going to happen. My family and I are going to go talk to the Shin clan, and you two are going to stay here. Once I’ve finished my business with them, of course, I’ll introduce you.”

“Question: Don’t you think there could be trouble if just two of us stay at this table?” En’en asked, raising an eyebrow.

“It’ll be fine. My brother will stay and look after you.”

“I will?!” This was evidently news to Lahan’s Brother, who was so surprised that he stood up out of his seat. “N-Nobody said anything about that to me!”

Lahan patted Lahan’s Brother on the shoulder. “Brother, Brother. I couldn’t possibly in good conscience leave two beautiful young women sitting by themselves. I’m so terribly sorry, but won’t you stay here and watch out for them?”

Lahan’s Brother looked at Yao and En’en. Lahan whispered in his ear: “My honored father absolutely must be present at these negotiations, but it would be trouble if all the men simply got up and walked away. Please, Brother—you’re the only one who can help me!”

Well, “whispered”—he made sure the rest of them could hear every word.

Lahan’s Brother caved. “Y... Yeah, all right.”

“You’re such a help, Brother.”

Watching the scene, Maomao realized she was seeing how Lahan had convinced him to go to the western capital. Lahan’s Brother was simply too good for his own good.

Chapter 3: The Shin Heirloom

A bell rang to mark the time.

“All right, I think we should get going,” said Lahan, standing up. Maomao, resigned, stood with him, and the freak strategist followed vacantly after. “We’re counting on you, Brother!” Lahan said to his older brother.

“Yeah, sure,” said Lahan’s Brother, but he didn’t sound very comfortable about it. They left two bodyguards, with only one of them accompanying Maomao and the rest—it was the man who had been watching the strategist the entire time.

“Erfan, keep an eye on my father to make sure he doesn’t wander off,” Lahan said.

“Yes, sir,” said the man. His name, Erfan, meant number two and presumably implied that he was one of the people the strategist had plucked for himself. Maomao approved: It was a nice, easy name to remember.

Erfan was somewhere in his thirties and certainly built like a bodyguard. He had wide-ish eyes and lacked what one might call an obvious zest for life, but that would probably happen to anyone who spent every day looking after the freak strategist.

The occupants of the Shin table rose as they approached. The lady of the family, the aide, and one other young man left the banquet. This being Lahan, he had probably reached out to the Shin clan before this meeting in order to arrange when and where they should talk.

Indeed, he followed them into the same private meeting room. Several of the rooms were already in use; little tags indicating as much dangled on the doors.

Inside the room was a long table with three chairs on each side. They would converse three-on-three, with one guard each.

“Ah, my friends! I must thank you for accepting my most humble invitation, especially you, mistress,” Lahan enthused.

Will you listen to this asshole? Maomao thought. Lahan had his business face on even harder than usual.

The freak strategist was just being the freak strategist; Erfan, meanwhile, held a bottle of fruit juice and a bag that emitted a sweet aroma.

“Heh heh heh. Mistress indeed. Very cute. And to what do I owe the honor of an invitation from the ever-aloof La clan?”

Aloof? I think she means outcast.

Maomao, however, kept her thoughts to herself. Lahan was doing the talking because the freak strategist couldn’t be relied on to offer a proper greeting. Under any other circumstances, people would not have smiled on Lahan speaking directly to a social superior.

“Shall we sit?” the mistress said, and finally they were able to take a seat. (Erfan had already had to restrain the strategist from just sitting down when he felt like it.)

Maomao sat at the end of their row. She had no choice but to sit next to the freak strategist, but she tried to slide her chair over so she was at least sort of a bit farther away.

I’m gonna make Lahan buy me off in herbs the next chance I get.

Maomao was having to suck it up a lot at this meeting.

“Now, I gather you have some enticing offer for us,” said the mistress. She was an older woman, but retained her authority and some vestige of the beauty she must once have possessed. The kind of woman Lahan loved dealing with.

“What if I told you I would find the heirloom that the Shin clan lost forty years ago?”

“Hoo hoo hoo hoo hoo hoo hoo hoo!” The mistress hid her mouth with a fan and gave a very aristocratic laugh. Her aide, beside her, looked downright exasperated.

The mistress said, “Really, wherever did you hear about that? Surely it’s futile to try to find the heirloom now?”

“Perhaps so, but word is that your late husband, the former head of the clan, was looking for it until practically the day he died. Yes...three years ago.”

Lahan practically sounded taunting, and Maomao noticed the eyebrows of the Shin young folk twitching.

Please don’t get us into any fights...

“Indeed he was. Do you realize what shame it brought him that the heirloom had been lost on his watch? It drove my husband to distraction. It was so bad that it caused him to treat his dear friend, the head of the U clan, as a thief, and to part ways with him on the worst of terms.”

“It’s a very well-known story, yes. How he ran through the palace with his sword out, screaming that the U had taken it.” Lahan recounted the story briskly, but it sounded like it had been quite a scene. The man was lucky he hadn’t been cut down on the spot.

“The very memory shames me. My husband was an accomplished and brave warrior, but he also had his quirks. It was always such a help that the head of the U clan was there to talk him down when he needed it.”

The mistress cast her gaze to the ground, grieved. The gesture revealed that, while the hair on her head had gone all white, a bit of black remained among her eyelashes.

She seems awfully sympathetic to the U, Maomao thought.

Her sympathy, however, was evidently not shared by her entire clan. The young man beside her jumped to his feet. “Grandmother! Why do you insist on defending the U clan? Where else do you think the heirloom could have gone?”

The man was somewhere in his twenties. It looked like the Shin was a family of soldiers, much like the Ma clan, for the young man was well-built. He was handsome, as might be expected of the mistress’s grandson, but he was altogether too...manly.

“The heirloom is gone. Did your grandfather not say with his dying breath that we need no longer search for it?”

“Yes, but—”

“That’s enough,” the aide said.

Wait... That isn’t the guy who wrote the love letters, is it? Maomao thought, but Yao had said her paramour wasn’t there, so it must be someone else.

“Say what you will about the U clan, but it seems not everyone in your family has given up on that treasure,” Lahan said pointedly.

“Grandmother, the La clan is offering to help us. If, even with their help, we can’t find it, then so be it. But can we not at least try?”

“You certainly are a persistent boy,” the mistress said, frustrated.

“Honored Father? What do you think we should do?” Lahan asked.

“Hm?” The freak strategist was busy munching on some crunchy dough twists Erfan had given him. When those were gone, there was fruit for dessert on the table, so that should keep him busy for a while.

“It seems we’ve wasted your valuable time, Father. And to think, after you made room in your busy schedule because this was a special request. We even disguised it as our own suggestion to help everything go smoothly.” Lahan shook his head and looked very disappointed.

“Just what does that mean?” The mistress looked at her grandson.

“I had to, Grandmother! Or we would never find it!”

“You set this in motion?”

“Yes. Yes, I did.”

The members of the Shin clan stared at the freak strategist. Normally people treated him like he had a big sign around his neck that said DO NOT TOUCH. It was one thing if this idea had come from the strategist—but quite another if it was the Shin clan who had first made contact.

Lahan must have reached out to the grandson. The Shin clan had supposedly given up the search with the death of its former patriarch, but not all of its members were prepared to accept that. It was easy to imagine Lahan talking up a storm with the grandson as the young man sought desperately for something to do.

Lahan looked distraught, but no doubt under that great big mask he was smiling.

“Of course, this did happen forty years ago, so even my honored father might not know anything that would be helpful. Still, to be called out here only to find you won’t even talk to us—well, one can only take so much mockery. Perhaps you could at least tell us the story?”

Maomao was genuinely impressed by what a talker Lahan was. He had said it was the Shin grandson who had asked for their help, but it was presumably Lahan who had instigated him to do that.

The Shin clan members appeared conflicted. The aide and the grandson looked to the mistress.

Finally she said, “Very well. And if you never find the heirloom, it’s no trouble.”

“That’s very kind of you.”

“Let me tell you the story my husband always told, then—with a few of my own additions.”

She took a deep breath and began.

○●○

First, let me tell you about our family’s treasured heirloom. It’s a statue in the form of a golden dragon holding a gemstone. The reason our heirloom depicts such an auspicious beast is because the character we received was Shin, “dragon,” and also because of the origins of our house. The Shin clan was granted a name because it’s a branch of the Imperial family—so the dragon is most appropriate.

We received the heirloom six generations ago. Perhaps it would be fair to say that it wasn’t granted to the Shin clan itself so much as to a son who renounced his Imperial status and became a common subject.

The crown prince at the time was frail, and he had many brothers both younger and older. The prince petitioned his estimable father, the emperor, saying that it would be better if a certain, especially capable younger brother of his were to take his place.

Unfortunately, capable though this brother was, his mother was not of high estate. In order to avoid civil strife engulfing the court, the crown prince determined to leave his family. The emperor, however, did not approve.

The crown prince was firm in his resolution, and after many twists and turns, things were finally resolved when he was allowed to resign his Imperial status and become a commoner. He was sent to the Shin clan, whose main branch at that time had no sons of their own.

Though the prince, as I said, was physically weak, he had a sharp mind, and the emperor cherished him. His Majesty granted him a statue of a dragon clutching a gemstone, as proof that even though the boy was no longer an Imperial family member, he was still the emperor’s son.

Yes, that’s right. Although he had no right of succession, a young man of our family was indeed a male member of the Imperial line.

I think that should be enough background. You’d probably like to know why and how we lost this heirloom.

Forty years ago, our family’s storehouse caught fire. It was a great blaze—heroic firefighting work and a providential rainstorm kept it from spreading to the main house, but nearly everything in the storehouse was lost. The dragon statue was in there as well, and if it were to have melted in the fire, well, there wouldn’t be anything left to find, would there?

My husband, though, was absolutely convinced that the heirloom was not destroyed. He thought someone had stolen it—carried it off—and he fingered the U clan as the culprits. Why? Because their leader had happened to be visiting our house just at the time of the fire.

The leader of the U clan noticed the fire before anybody else—he put copious amounts of water on the blaze and tore down a nearby hut to help prevent it from spreading. It was very much thanks to him that the flames didn’t leap to our mansion just nearby, but so far from being grateful, my husband dragged his name through the mud. He claimed that the U clan had stolen from him under the cover of the fire, that they were jealous of the fortunes of the Shin and so had made off with the heirloom.

I do have some sympathy for how he felt. What he was probably trying to say was that it was the U clan who had been the first to betray.

At the time, the U were aligned with the faction of the empress regnant—if I may call her that. I mean the empress dowager of that era. My husband, who prided himself on having Imperial blood even if he couldn’t succeed, was defiant; he refused to bend the knee to some nobody from nowhere. Frankly, to say such things of the mother of the son of heaven went beyond rudeness and bordered on treason.

It gives me chills to remember it even now. I marvel that he didn’t arouse the empress regnant’s ire and cause the Shin clan to be destroyed.

Do you see now why I say there is no need to go looking for the heirloom? I believe it was destroyed along with the storehouse. It melted in the fire forty years ago, and won’t be reappearing now.

My husband thought differently; he continued to search for the rest of his life, and insisted to his children and grandchildren that the heirloom must still be out there somewhere. All of which has led to our current antagonism with the U clan.

○●○

The mistress finished her story and sipped her tea. There were no Chu servants in the private rooms, so their respective guards had prepared tea for them.

A former member of the Imperial family with no place in the line of succession? Maomao stroked her chin, made a thoughtful noise, and looked at the freak strategist.

“Yes, Maomao? What is it?” he said, instantly attentive.

For a second, she battled with the urge to ignore him, but she needed this conversation to keep moving, so she sucked it up and forced herself to whisper in his ear, “Were there any lies in that story just now?”

“Lies? Hmm...”

She took that to mean that there hadn’t been. She also didn’t like how the freak seemed weirdly pleased about all this, and she quickly resumed her distance from him.

There were just too many things about the story that nagged at her.

Lahan, of course, didn’t miss the look on Maomao’s face. He raised his hand. “If I may?”

“Yes? What is it?” the mistress asked.

“Ah, ahem. It’s not my own humble self but my younger sister who seems to have something to say.” He looked at Maomao and managed to wink rather deftly.

Son of a...

She had an urge to crush Lahan’s toes, but the freak strategist was between them, so she couldn’t reach. As a consolation prize, she stepped on the strategist’s foot instead. He looked like he was about to cry out, but when he realized it was Maomao who had done it, a gross smile came over his face instead.

Maomao ignored him and took a deep breath. “If you’d be so kind, perhaps I could ask you a few questions.” She mentally reviewed the features of the story that had caught her attention. “Can you describe the exact shape of the dragon statue?”

“The exact shape? The size was... Well, perhaps it would be quicker if I drew you a picture.”

The mistress’s aide passed her paper and a writing utensil, and she quickly produced an excellent sketch of a dragon.

“You’re quite the artist,” Maomao commented, and she meant it.

“Oh, I’m an amateur. I just do it to pass the time.”

The creature the woman had drawn was a basic dragon, about like what Maomao would have expected. It had a long body like a huge snake, and two horns. The claws of one of its front paws clutched the gemstone, and it had a flowing mane. Assuming the woman had drawn it to size, it rested on a base of about nine centimeters.

It’s smaller than I expected.

There was nothing particularly unusual about it—except for one thing.

“It has four claws on each paw?” Lahan asked. And indeed, the paw with which the dragon held the gemstone appeared to have been drawn with only four digits.

“That’s correct. I realize such a depiction would normally only be allowed to the Imperial family, but it simply goes to show how much the emperor at the time loved the crown prince. This was proof that even once he had reduced himself to a subject, he was still the emperor’s son. He was given a gemstone—an amethyst.”

Purple was second only to gold among colors considered to be noble.

I seem to remember the empress dowager liked to wear gold clothing.

The most noble of colors was called massicot, a reddish-gold hue that no one but the Emperor was allowed to use.

“Was the dragon statue made of pure gold?” Maomao asked.

“No, I think it had some silver mixed in.”

Pure gold was very soft—easy to work, but equally easy to damage or destroy. Combining it with silver would make the statue stronger.

Maomao closed her eyes and tried to mentally organize the information they had received.

Sometimes when two metals are mixed together, it can lower the melting point of the resulting combination. But I don’t think gold and silver lower it that much.

But if there was indeed no lie in what the mistress said, she evidently genuinely thought that the heirloom had been caught in the fire and melted down.

“Could you please describe once more in detail the scene of the fire?” Maomao asked.

The Shin grandson, however, jumped to his feet. “Argh! I’ve had enough of this! Grandmother, why are we wasting our time explaining when we could be settling things with the U clan right now? Let’s go!”

He pulled on his grandmother’s hand, but the aide dropped a knuckle on him. “Calm down.”

“Urk...” The grandson rubbed his head.

Huh! I feel like I’m getting déjà vu...

It was almost like she was looking at Gaoshun and Basen. Did all physically robust families talk with their fists?

“May we continue?” Lahan asked the mistress politely.

“Please do.”

“You heard her,” he said, waving to Maomao.

Maomao collected herself and asked, “What was the cause of the fire, ma’am?”

After a moment, the other woman responded, “It spread from a light in the archives.”

“Oh, I...see!” Maomao grabbed her side; the freak strategist had suddenly jabbed her with a finger.

The hell is he doing?! Maomao seriously considered smashing the strategist’s toes, not just to let off steam, but for real. She saw, however, that the monocled freak’s eyes were shining strangely, as though he were a dog who had brought an item he’d been told to fetch and was waiting to be told what a good boy he was.

Is he trying to tell me that what the mistress just said was a lie?

The freak strategist’s already narrow eyes narrowed even further. Maomao appreciated that he had alerted her to the deception, but it made her kind of sick to have him poke her, so she gave him a smack on the hand.

Why would she try to cover the cause of the fire?

Maomao considered carefully, then asked her next question. “Exactly how much of the storehouse burned?”

The mistress looked at the ground, searching her memories. “It didn’t fully collapse, but the inside was scorched black. It was full of books and other flammable items, and hardly any of them survived.”

“So the books were lost. That would imply any furniture went too. But a vase, for example, might have been safe, right? Then again, I suppose any artworks would have lost their value. Were there any swords or armor in there?”

“Several display pieces, yes. I also recall that the family’s trousseau survived—maybe it was far enough away from the source of the fire.”

The freak strategist didn’t react to that.

“One last question, then. You said the leader of the U clan was there and helped to put out the fire. Had he planned to visit that day? Or did he just happen to drop in?”

The mistress closed her eyes. “He had prior plans to visit our home.”

“So you were aware that he would be there?”

The mistress went silent for a long moment. Finally, she said, “No... His visit was a surprise for the Shin clan.”

The way she said it certainly seemed to invite more questions, but the strategist still didn’t react, so it was probably the truth.

“Why do you think he showed up so suddenly?”

Another pause. “I suspect it was on the empress regnant’s orders. I told you how they toadied to her at the time. Back then, my husband had only recently become the head of the Shin clan. He was still young and his blood was hot. Those who opposed the empress regnant worked him up, told him that even if he wasn’t an Imperial family member, his status was practically as good. And in the midst of all that, we got a visit from the U clan. Do you understand?”

“Had they come to suppress any evidence of rebellion?”

“Most likely.” Her tone was evasive, probably because the fire had claimed everything. “All our family treasures turned to ash, but personally, I thought that was well and good. When I considered the empress regnant’s force of will, it seemed a miracle that our clan hadn’t been extinguished long ago. The only thing I regret about that incident is that my husband never reconciled with the man who had once been one of his closest friends.”

The mistress began to weep a flood of tears; she swiped at them with her handkerchief as if trying to push them back.

“Are you finished with your questions?” the grandson asked Maomao, just managing to sound polite.

“Yes, thank you.”

“And have you figured anything out?”

“I have.”

“What?!”

Not just the grandson, but the aide and even the mistress herself were shocked at this reply.

“You cracked the whole case from what you were just told?” the grandson asked.

“I haven’t figured out everything. There are a few points I’m still not sure about.”

Lahan was nodding; he must have caught on to at least some of what Maomao had noticed. The freak strategist’s gaze, meanwhile, was fixed on the old woman to make sure she wasn’t lying.

“A few points like what?”

“You said that the books burned, but some swords and armor as well as your trousseau survived. The trousseau would have included a bronze mirror, yes?”

“Yes,” the mistress echoed, perplexed.

“That doesn’t make sense, does it?” Lahan piped up.

“No, it doesn’t,” said Maomao. They looked at each other.

“What about it doesn’t make sense?” asked the aide, mystified. The way he spoke sounded oddly like the grandson.

“Ahem. Well,” said Lahan, and Maomao decided that if he was going to explain, she would let him handle it. “A few minutes ago, we were told that the dragon statue melted and is gone. However, it’s hard to believe that the fire got hot enough for a gold alloy to melt.”

“Wh-What do you mean by that?”

“A bronze mirror, needless to say, is made of bronze. Bronze and gold have roughly the same melting point.” Lahan’s spectacles flashed. “If the mirror didn’t melt, then it’s unlikely that a gold object would have. Besides, when gold melts, it doesn’t disappear. Even if it had melted down to a lump, it would have been around there somewhere. And unprocessed gold is particularly valuable, so I seriously doubt it would have been left lying on the ground.”

“Is that right?” The mistress’s eyes were wide. The melting point of gold wasn’t something that the average daughter of a well-to-do family would know. It wasn’t even common knowledge in general. Maomao and Lahan just happened to know it—in her case because her old man had told her; in his because such knowledge could contribute to business.

In a trembling voice the mistress asked, “Th... Then where do you think the heirloom went?” Maomao could see how shaken she was.

Maomao held up a hand. “Before I answer that, let me confirm a few points.”

“Such as?”

“You said the U clan paid a surprise visit to the Shin estate. It was smack in the middle of the fire, which they helped extinguish, yes?”

“That’s right.”

“After the fire was out, they searched through the wreckage of the storehouse for any sign of rebellion, didn’t they?”

“I should think so.”

One assumed that they hadn’t found anything, which was why the empress regnant stayed her hand against the Shin clan.

But had there really been no proof of treason?

“Let’s find out whether there was any proof or not,” Maomao said. From the folds of her robe she produced a hair stick, one in...unique taste. It was the one the freak strategist had given her earlier, with the amethyst skull dangling from it. She plucked the skull off.

“Little sister,” Lahan warned. “No matter the circumstances, I really don’t approve of destroying a gift in front of the person who gave it to you.”

“Oh, Maomao! You only wanted the skull? Next time I can make a whole rosary of crystal skulls for you!”

“Please don’t!” Maomao and Lahan said in unison.

“Take a look at this,” Maomao said, showing the skull to the mistress. “The amethyst the dragon was holding—was it like this one?”

“Yes. I think it was a similar color,” said the mistress.

The skull in Maomao’s hand was a deep, deep purple. It was clearly an extremely high quality gem—a shame that it ended up as a skull, Maomao thought.

“All right.” Maomao looked toward the brazier burning in a corner of the room. It must have been for heating tea, because there was a teapot sitting on it. “Could you bring that brazier over here?” she asked Erfan. She could have asked Lahan or the freak strategist, but they were so weak that they probably would have spilled it on the way, and she wasn’t eager for that.

“Yes, ma’am,” said Erfan, carrying the brazier easily.

“Everyone, watch carefully, please.” Maomao took the fire chopsticks and put the skull among the coals, where she rolled it around.

“Hm?”