Character Profiles

Maomao

A former pleasure-district apothecary. After a stint in the rear palace and then the royal court, she now finds herself an assistant to the medical office. Her current number one interest is Kada’s Book. She despises her biological father, Lakan, but lately her distaste for Hulan has been through the roof. Twenty-one years old.

Jinshi

A young man as lovely as a celestial nymph, Jinshi is supposedly the Emperor’s younger brother. He spent time in the rear palace masquerading as a eunuch; thinking of it now makes him so embarrassed that if a hole were available, he would crawl into it. Real name: Ka Zuigetsu. Twenty-two years old.

Basen

Gaoshun’s son; Jinshi’s attendant; duck aficionado. He and his sister Maamei are laying plans to get him married to former high consort Lishu. Twenty-two years old.

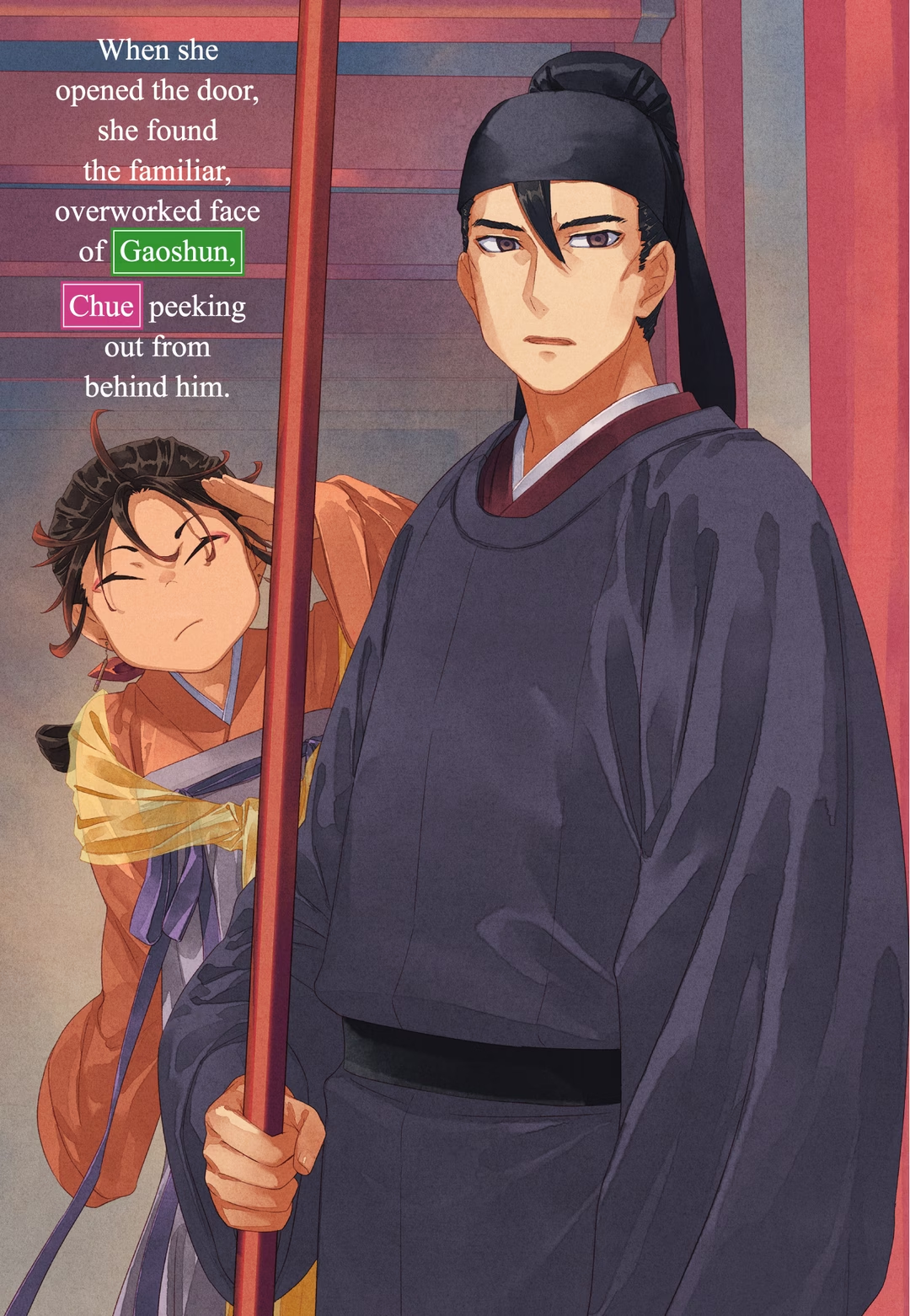

Chue

Wife of Gaoshun’s son Baryou. A lady-in-waiting who seems to show up at the most unexpected times. She’s good with people, though, so she gets along with her in-laws. Hates Hulan. Twenty-three years old.

Lahan’s Brother

Older brother of Lakan’s adopted son Lahan. He doesn’t appear in this volume.

Lakan

Maomao’s biological father and Luomen’s nephew. A freak with a monocle. He and the Emperor seem to have quite a history.

Suiren

Jinshi’s lady-in-waiting, former wet nurse, and grandmother.

Empress Gyokuyou

The Emperor’s legal wife. An exotic beauty with red hair and green eyes. She’s the mother of the Crown Prince, but because of her looks, many feel she’s not fit for her office. Twenty-three years old.

Hongniang

Empress Gyokuyou’s chief lady-in-waiting. So good at her job that the Empress is reluctant to let her go.

The Three Young Ladies Who Serve Empress Gyokuyou

Yinghua, Guiyuan, and Ailan by name. Former attendants of the Jade Pavilion who have always been kind to Maomao. They haven’t changed much in the interim.

Yo

A newly recruited assistant in the medical office who has smallpox scars.

Changsha

A newly recruited assistant in the medical office. Lives in the same dorm as Maomao.

Tianyu

A young physician. A dangerous character who especially likes performing autopsies. A descendant of Kada.

Hulan

Gyokuen’s grandson; Empress Gyokuyou’s nephew. A member of the Gyoku clan, he’ll stop at nothing to get what he wants, including killing his older brother. Currently serves as Jinshi’s aide.

Maamei

Basen’s older sister. Most formidable of the three Ma siblings.

Baryou

Basen’s older brother; Chue’s husband. Physically weak, he spends most of his time hidden behind a curtain.

Dr. Liu

An upper physician. He and Luomen go way back. He imparts stern instruction to Maomao and her friends.

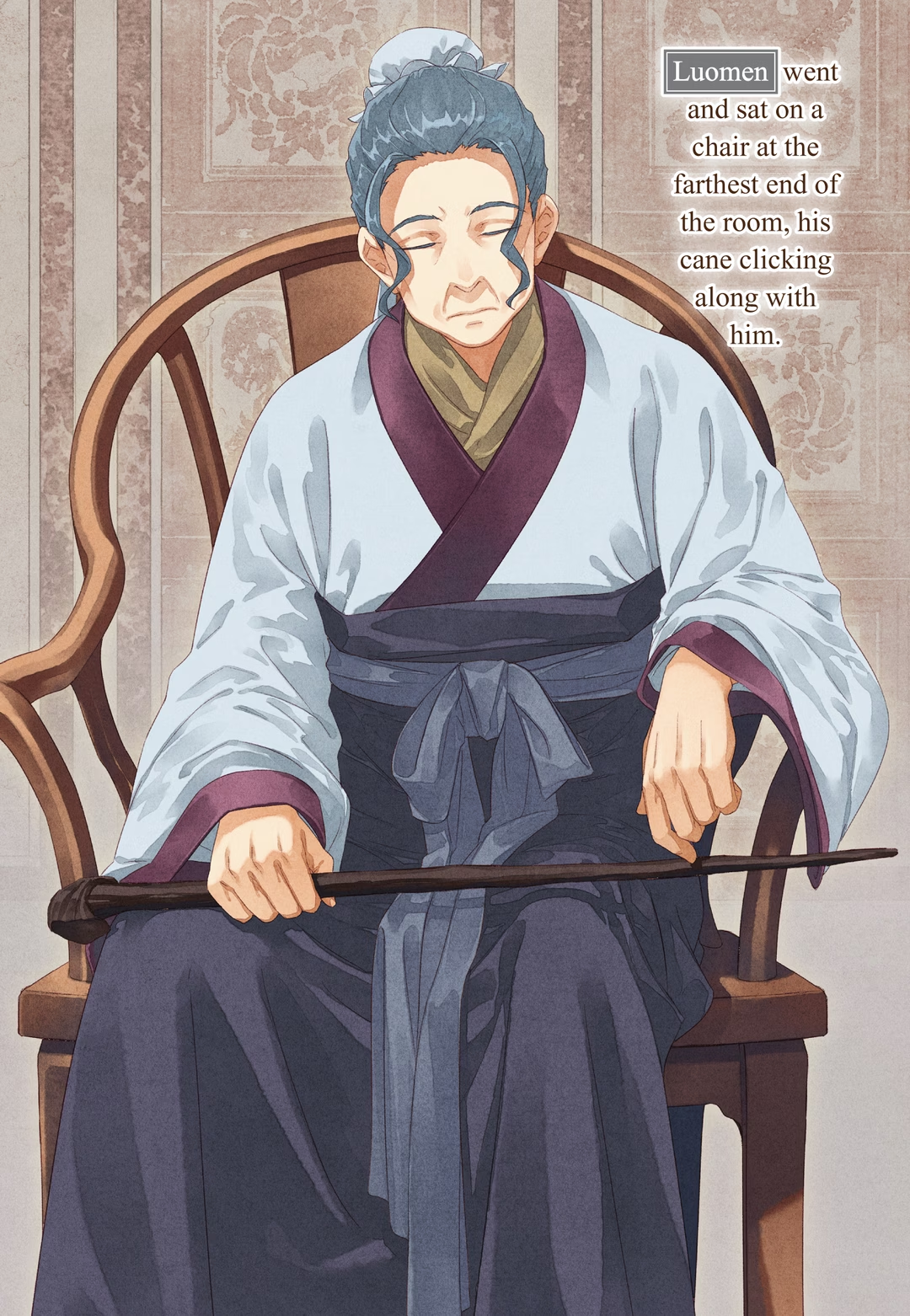

Luomen

Maomao’s adoptive father; a eunuch. He now serves as a physician to the court and rear palace. He goes way back with Dr. Liu.

Dr. Li

A middle physician. He went to the western capital with Maomao and the others, and the stuff he went through there really beefed him up.

The Emperor

Supposedly Jinshi’s older brother. His facial hair may be prodigious, but it doesn’t solve the many worries he has on Jinshi’s account.

Gaoshun

The Emperor’s milk brother; father of the three Ma siblings. He’s hen-pecked and long-suffering, but he knows a side of the Emperor that few people see.

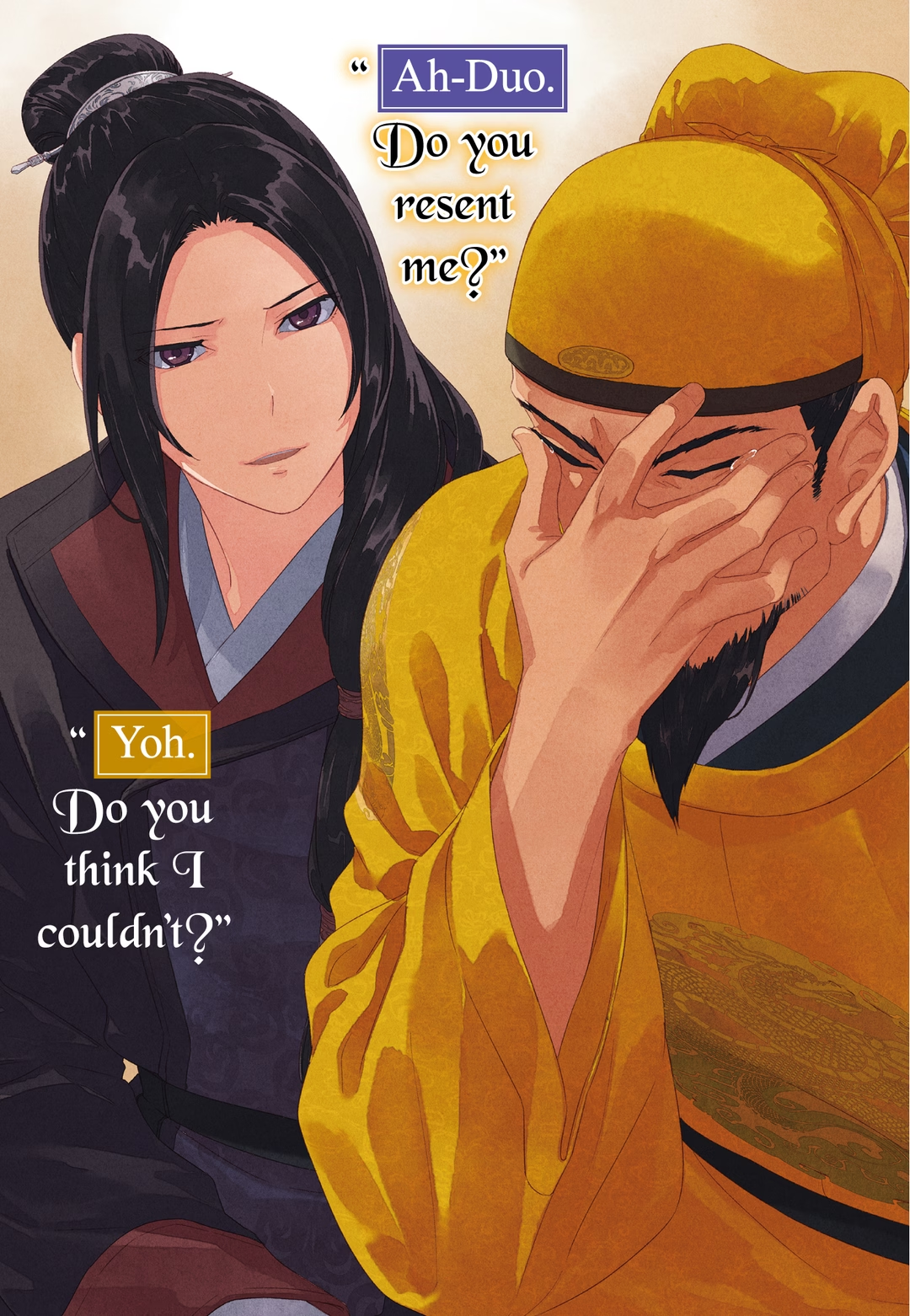

Ah-Duo

A former high consort, and Jinshi’s real mother—she switched him with the Imperial younger brother when he was an infant. She’s currently living out her life in a secluded villa.

Suirei

A survivor of the Shi clan; granddaughter of the former Emperor. Currently hidden in Ah-Duo’s villa.

Chapter 1: The Selection Exam

The pounding sun was growing the slightest bit less intense; in this season, they could at least bear to work without rolling up their sleeves.

“Work’s been getting a little easier lately, huh?” Maomao said.

“Yes, so it has,” replied Dr. Li.

They were cleaning the break room together. It was normally not the kind of job someone of Dr. Li’s status would have bothered with, but in his newly muscled state, he would do anything for some exercise. He even went out of his way to move the beds and clean under them. He probably didn’t even care about cleaning—he was just here to work his muscles.

Work was “getting easier” because there were fewer fights among the soldiers. Maybe they had once again begun to recognize that the freak strategist was their common foe, or maybe their superiors had given them the evil eye.

Or maybe something that was causing the problem has been cleared up? Maomao thought. Whatever it was, she was grateful. Was Jinshi or someone like him responsible for taking care of it?

Boy, but the break room sure did get dirty fast. In addition to sometimes having injured or sick people rest there, the physicians used it to take naps. That was all well and good, but not so much the sticks left over from late-night snacks of meat skewers, or—she couldn’t believe she was finding this—a naughty book that had clearly been passed around.

I remember using these as textbooks in the rear palace, she thought, thumbing through the pages and then leaving it on the table. If the book had an owner, he would presumably take it home with him; and if it didn’t, well, someone might still take it home; and if no one claimed it, they would dispose of it.

“Whatcha got there? A little personal reading, Niangniang?”

Maomao involuntarily backed away from the voice. There was only one person who called her Niangniang.

“Yes, Dr. Tianyu? Can I help you?” she said.

“I never took you for the kind to read stuff like that, Niangniang.” He was thrilled to have found something to tease her about, but unfortunately for him, he didn’t realize that Dr. Li was standing right behind him.

“One of the physicians forgot it here,” Dr. Li said.

“Eeyikes!”

“‘Eeyikes,’ indeed! What kind of greeting is that?”

Tianyu’s face tensed when he saw Dr. Li, who was already preparing to bring down his knuckle.

“What’re you doing here, anyway? What happened to doing your work?” the doctor said.

“I did my work! Really, I swear I have a good reason to be here, so maybe we could skip the knuckle for today?” Tianyu clasped his head and tried to make himself as small as possible. He took most things in stride (The wind is no enemy of the willow tree, as the proverb went), but Maomao was tickled to find out that even he had a natural predator.

“So. What is this good reason?” As she spoke, Maomao flung herself into a chair, folded her legs indolently, and, just for good measure, scratched at her ear with a finger.

“You sound polite, but I don’t think you’re being polite,” Tianyu groused.

“It’s your imagination,” Maomao said, blowing on whatever had ended up on her finger.

“Maomao, it’s fine to ignore most of what Tianyu says, but he may have come with orders from above. We should hear him out, just to be sure,” Dr. Li said.

“Yes, sir.” If Dr. Li insisted, it wasn’t her place to refuse. She resigned herself to listening to Tianyu.

“There’s really a bright line between people you’ll listen to and people you won’t, isn’t there, Maomao?”

“It’s your imagination...sir.”

They moved from the break room to the physicians’ administrative office, where they found the elderly doctor checking over the daily reports.

“Dr. Liu is asking for Niangniang. May I borrow her?” Tianyu asked the older man; even he knew enough to mind his p’s and q’s around this physician.

“Tianyu and Maomao? Do you think this is about—?” The old doctor seemed to have some inkling as to why Maomao would have been summoned. “Sure, you can have her. Is she the only one?”

“If I brought Dr. Li, too, things would be all kinds of tough, wouldn’t they?” Tianyu replied lightly.

“True enough. Li here is very versatile. I’d be much obliged if you’d leave him with me.”

That sounded very portentous, but Dr. Li seemed as mystified as Maomao as to where she was going to go. “Are you sure I shouldn’t go along?” he asked not Tianyu, but the old physician.

“Yep.” It wasn’t the old physician who answered, but Tianyu.

“If you’re leaving Dr. Li with me, then fine. Go ahead and take Maomao.” The old doctor handed Dr. Li the reports.

Whatever the reason for this summons, Maomao was not much more eager than anyone else to spend time with Tianyu. “I think it should be Dr. Li who goes instead of Dr. Tianyu,” she said. “I humbly request he change with Dr. Li. We can leave Dr. Tianyu here instead.”

This was both her considered professional opinion and her knee-jerk personal one.

“Absolutely not. I have no use for Tianyu either,” the old doctor said firmly.

“Ha ha ha! Boy, Dr. Li, you sure are popular,” Tianyu said.

“And you don’t seem to be much liked anywhere you go, Tianyu,” said Dr. Li, as merciless as his colleague.

“What are we going to be doing?” Maomao asked.

“You know, no one told me much. They just said to be sure to bring you along, Niangniang.”

Maomao and Tianyu both crossed their arms.

“Oh, it’s nothing big. Just a simple test. If you don’t pass, no harm done,” the old doctor said, gazing out the window. “Now, I think you’d better get going.”

“Yes, sir,” Maomao said, and then she and Tianyu took their leave of Dr. Li and the elderly physician.

Dr. Liu’s medical office was in the center of the palace grounds—it was located in the outer court, but close to His Majesty’s bedchamber. Dr. Liu, however, was not there.

“You’re looking for Dr. Liu? He’s this way,” said another physician, showing Maomao and Tianyu to another room.

It turned out they were not the only ones who had been summoned; quite a few other physicians were there. Everyone milled about, clearly uncertain why they had all been called.

Interestingly, there were even several women. Not Maomao’s colleagues Yao and En’en—these women were older; one could call them middle-aged, but they didn’t appear to be palace women as such.

Outsiders? That seems unlikely.

Whoever they were, their presence helped prevent Maomao from standing out like a sore thumb.

Her jaw dropped, however, when she saw who else was there—someone she never would have expected. A very elderly-looking physician with a bowed posture.

“Pops...”

Maomao’s adoptive father, Luomen, was there. He was supposed to be the rear palace physician. Maomao trotted over to him.

“‘Pops,’ nothing!” he said. “Around here, you can call me... Hmm, let’s see. Call me Dr. Kan.”

“Yeah, but what are you doing here?”

“Again: Watch your tone. And be patient. You’ll learn the answer soon enough.”

I take it Pops knows perfectly well what we’re all doing here.

Given the elderly physician’s knowing comments, Maomao suspected the upper physicians had all talked this over to some degree or another.

“So what’s goin’ on?” Tianyu asked Luomen, trotting up behind Maomao.

“You’ll find out any minute now. You can’t expect me to explain it individually to every single one of you.” Luomen worked his way to the far end of the room, his cane clicking against the ground as he went. There was a desk there, and behind it was Dr. Liu. Another of the upper physicians was with him, and they were talking about something.

Dr. Liu clapped his hands, cutting through the murmur of voices that filled the room. Everyone immediately fell silent. “It looks like you’re all here. You must excuse the abrupt summons,” he said. “Without further ado, we’re going to divide you into three groups.” He held up a paper so they could see it. Luomen and the other physician did the same. “I want each of you to go with the physician whose paper has your name on it.”

Maomao hopped up and down, trying to get high enough to spot her name.

Yes!

It looked like she was in Luomen’s group, the last name on the list. About ten other people also clustered around her father.

“I believe that’s all of you. Come this way, please,” he said, setting off with his cane clacking. Maomao skipped a little as she followed behind him. It crossed her mind to walk alongside him, but she thought better of doing that with all the doctors around, and attached herself to the back of the group instead. Another physician was helping Luomen, with his bad leg, along.

Luomen took them to another room, where there were desks with papers on them, enough for everyone.

It really is a test.

Maybe the unexpected summons had been a way of trying to catch them off guard. Everyone looked around, confused.

“Uh, sir?” said one of the physicians, raising his hand. “Why are we taking a test now?”

“You don’t have to take it if you don’t want to. If you’d rather leave, feel free—you won’t be punished, and no one will hold it against you.”

Luomen went and sat on a chair at the farthest end of the room, his cane clicking along with him.

The only kind of person I can think of who would go home when he said that would be a kid going through a rebellious phase.

The doctors looked at each other, then took their seats. Maomao sat at the last available desk.

“You have one hour. Let’s go ahead and get started,” Luomen said, lighting a stick of incense.

The test paper lay face down on the desk; Maomao turned it over and took a look. It consisted of about fifty questions regarding basic medical knowledge and another fifty about pharmaceuticals specifically. Given the one-hour time limit, she got the sense that they were expected to answer all the questions easily—these should be things they already knew.

Maomao began filling in answers, writing away without a break. A few of the doctors were sweating; occasionally someone would drop his brush or let out an audible groan—maybe they had written a word incorrectly.

“All right, time’s up,” Luomen said. The hour had passed in the blink of an eye. Maomao hadn’t even had time to double-check her answers, but at least she had filled everything in. That was a good start. Some of the physicians’ shoulders slumped. It was rough when you knew you could have answered more of the questions if you’d had more time.

Once Luomen was sure that the incense stick was out completely, he stood up. “All right, on to the next location.”

He started walking, and where should he lead them but the medicine storage room.

The storage room was packed with medicine cabinets. Maomao came all the time on official duties, but no matter how often she was here, it never failed to excite her.

Okay, got to take a deep breath.

She breathed in, savoring the room’s distinctive smell.

Now that I think about it...

She began to register the faces of the assembled physicians. She didn’t recognize all of them, but several were often assigned to manage the medicines in this room just like she was. Given the content of the written examination they had just taken, she was starting to think that this group was full of people who were very experienced with medicinal herbs.

So would that mean Tianyu’s group is surgery?

Tianyu was a gifted surgeon, if nothing else (including a decent human being).

“What should we do next, sir?” one of the physicians asked.

“Well, let’s see. Perhaps I could ask each of you to make a few medicines?”

“Yes, sir.”

The doctors were trying to reset themselves.

“The patient is a twenty-year-old woman. Her husband has come to you saying that she hasn’t been able to sleep, possibly because of gastritis. What kind of medicine would you use to treat her?”

Several of the physicians sprang into action. Some went scrambling for ingredients; others, perhaps depressed by their performance on the written test, only seemed to be going through the motions of making medicine.

But Maomao and three of the doctors didn’t move.

We’d only trip over each other by crowding the cabinets at the same time. There are plenty of ingredients; we won’t run out.

The three doctors, like Maomao, were people who had been assigned to manage the medicine cabinets. They didn’t have to rush; they knew exactly what was in each drawer and could afford to take their time.

Tall Senior, Short Senior, and Mid-Height Peer, Maomao thought, assigning each of them an arbitrary name. Well, not completely arbitrary: One of her seniors was tall, the other was short, and the physician who had joined the staff at the same time she had was of average stature. Each of them more or less did their own thing, so they had never really gone out of their way to introduce themselves to each other, but they knew each other by sight.

The doctors who had gone into action first had begun to assemble their ingredients from the panoply of cabinets. Maomao looked over the drugs that had been gathered on the table.

Longan and tohki, licorice, gardenia... Are we dealing with something to combat anemia and poor sleep?

A few of the physicians had chosen slightly different ingredients, but they were all making roughly the same thing.

“You’re not going to do anything?” Luomen asked Maomao and the others who had stood still.

“If we all rushed the cabinets at once we’d only trip over each other, sir,” said her tall senior colleague.

Her shorter senior narrowed his eyes and asked, “Does the patient have any other symptoms?”

Are we allowed to ask that?

“Symptoms,” Luomen echoed. “What kind of symptoms did you have in mind?”

“Does this person have morning sickness?” Maomao asked pointedly. A twenty-year-old woman, with her husband making the inquiry? One had to consider the possibility of pregnancy. There were plenty of drugs that could help with insomnia, but many of them could have negative effects on the pregnancy.

The other physicians who had stayed behind seemed to have had the same intuition as Maomao.

That doesn’t mean that the other doctors are incompetent or anything.

The vast majority of the patients they would see in the court were men. Even when a palace lady got sick, she often preferred to hide that fact rather than present herself at the medical office, and if she was pregnant, she would probably just leave court service altogether. Luomen had presented them with a trick question, one that required them to take a step beyond their experience as court physicians.

“Well, let’s see... The husband reported nausea, so I think it would be wise to consider the possibility.”

Only then did Maomao and the other three finally move. The doctors who had gone first were starting to show Luomen the results of their efforts—and he was telling them they had failed. One of them did pass, but he didn’t seem very happy about it; maybe his results on the written test hadn’t been so good.

The remaining four, including Maomao, gathered roughly the same kinds of herbs and made similar drugs. They each had their own particular way of going about it, but they came up with more or less the same thing.

Time was short, however, and Mid-Height Peer looked a bit rushed. Or maybe he was all too aware of the other doctors, the ones who had failed, watching them as they worked.

“Good, you three have the right answer. This one... Perhaps prepare it with a little more care,” Luomen said.

Only Mid-Height Peer was rejected—he hadn’t had time to mix the ingredients properly.

“Yes, sir. I’ll work faster,” he said, disappointed but willing to acknowledge where he had gone wrong.

“Now, let’s move on to the next problem,” Luomen said.

He had them make several more medicines in much the same way. It was very characteristic of him to see what they could make on their own, rather than simply handing them a recipe and asking them to mix it.

And he does love to set little traps.

It was somewhat mischievous, yes, but then, patients often had trouble explaining their own symptoms clearly. Luomen was conveying that it was good to be prepared to question what the patient told them.

If only he was this careful about money, Maomao thought. He’d been officially hired as a physician, so she assumed no one was taking a cut of his rear-palace salary, but maybe she would ask when she got a chance, just to be sure.

I can, however, totally imagine him giving everything he owns to some random person in trouble that he passed by.

Which meant that if he never took a step outside of court, everything should be fine... Right?

Maomao let these thoughts parade through her head as she made the medicine for the next problem. Luomen went around observing not only their herbal knowledge, but also the ways in which they made their medicines. It was about more than what components one chose; it was how you handled them, how you mixed them together.

He told us no one was required to take this test...

But Maomao was very curious what task they would be put to if they passed.

“Next, hmm... Perhaps you could see how much you can make within the given time. Use the ingredients listed here.”

Luomen was upping the difficulty.

Maomao looked at the formula and raised her hand. “Sir?”

“Yes?”

“What would be the point of making so much of this medicine? We would never be able to use all of it.”

If they were going to ask her to waste precious medicinal herbs, Maomao was going to say something about it.

“I agree with her,” Short Senior said. The medicine they were being asked to make was a concoction for stomachaches, but considering how much of that they went through in a day, this was far too much. The herbs that served as the basis for this medicine could also be used in other drugs, so it was no good to burn through them making a bunch of the same medicine.

“Couldn’t we make something for wounds? Something we could use on the soldiers?” Maomao asked. The other physicians agreed with her.

“The medicine won’t go to waste,” Luomen assured her. “It will be distributed to patients in town.”

“Sir... What does that mean?” asked Mid-Height Peer. The other doctors likewise began to murmur among themselves.

“It’s in order to investigate the effects of a new medicine we’ll be making. We’ve gathered a group of patients with similar symptoms to make it easy to compare them.”

It was like a more precise version of the experiments Maomao had been performing on her left arm.

Silently, she looked over the formula they’d been given once more. Winter melon seed, rhubarb root, mu dan pi...

Something for circulation?

Just what kind of patients had they gathered? And what kind of medicine were they trying to develop?

“Today’s tests are about deciding who will be involved in administering the medicine. The tests, incidentally, are now over. You may all go home. You’ll be notified soon whether you passed or not.”

Carrying their answer sheets, Luomen left the room.

The test takers all looked at each other, mystified, and then began to filter out.

Guess I’ll go too.

Maomao was about to do just that when someone caught her shoulder.

“Hey, you.”

It was one of the other test takers—the one doctor out of the early birds who had passed the first medicine-making test. Maomao had never been in the same office as him, but she’d seen his face somewhere.

“Do you know about Suirei?” he demanded.

“Suirei... Oh!”

Years ago, there had been a physician who had been in love with Suirei. She’d used him like a pawn when she’d made her “resurrection drug” and fled the palace.

He was entrusted with looking after the medicine supply before.

Now he was assigned somewhere else, presumably demoted after what had happened with Suirei. Was it just luck that he and Maomao had never run into each other so far, or was somebody politely keeping them apart?

“When you say Suirei, do you mean what she’s doing now?”

“That’s right.”

“I have no idea.”

“Is that the truth?”

Hell no, it’s not.

But she had to lie to him.

For outward purposes, Suirei was someone who could not exist. She was a member of the Shi clan and a granddaughter of the former emperor. She’d been involved with “accidents” and murders of several VIPs, and had even abducted Maomao. The moment anyone learned she was alive, she might be headed to the gallows.

Thus, no matter how cold it seemed, Maomao had to be firm. “If I ever find out where she is, I’ll be obligated to tell someone. I’d probably even collect a nice reward for it.”

Suirei was a suspect in a whole range of cases. Even this doctor had to know that she would never be safe if she were found.

After a long moment, he said, “All right.” Then he left the room, shoulders slumped.

Do yourself a favor and forget about her, Maomao thought, putting a hand to her chest in relief.

Chapter 2: Smallpox and Chickenpox

The day after the test, Maomao was taking stock of their inventory as usual.

Why would they handpick people to do drug trials? she wondered.

It was her fault for pondering while she worked.

“Yikes!”

She was so distracted by her ruminations that she almost knocked over a jar full of medicine. She was saved by Yo, who had come to help her and luckily was standing nearby. She propped the jar up and prevented catastrophe.

“Phew... Sorry about that. Thanks for the help,” Maomao said.

“Is something on your mind?” Yo asked.

Yo was the taller of the two palace ladies who had recently joined the service. She was assigned to a different place from Maomao, but frequently came to her to learn how to mix or preserve herbs and medicines. She was a quick study, and Maomao enjoyed having a student who rose to her teaching.

“Oh, nothing much,” she said now, trying to energize herself with a slap on the cheeks.

Still, she couldn’t quite get the thought out of her head. Just then, she happened to catch sight of Yo’s long sleeves. “I realize this isn’t very polite, but may I make a request of you?” she said.

“Yes? What?”

“Would you show me your smallpox scars?”

Yo’s arm was covered with small welts from smallpox. An outbreak of the disease had destroyed her village.

Yo looked dubious for a moment, but then she rolled up her sleeves. Her arms were covered in small scars like tiny red beans.

“Are they that unusual?” she asked.

“No, but I’ve never had the chance to examine smallpox scars up close,” said Maomao. Some of the customers at the apothecary shop had had them, but no one had been eager to show them off. Maomao knew very well that it was not a nice thing to ask for.

“Are the scars only on your arms?” she asked.

“No, I have some on my shoulders and neck as well. But a lot fewer than some other people.”

“You think that’s thanks to Kokuyou’s treatment?”

“Yes,” Yo said simply.

Kokuyou had highly visible smallpox scars on his face, but he was surprisingly cheerful in spite of it. He had been a doctor in Yo’s village, and although he acted awfully frivolous, Yo trusted him implicitly.

“This treatment—what exactly did he do to you?” Maomao had heard some sort of explanation before, but she wanted to be sure.

“He made a wound on my skin and rubbed powder made from an old scab into it. I’ve heard you can also inhale the powder through your nose, but he didn’t have enough for that.”

“Hoh, hoh.” Maomao nodded; this was definitely worth asking for details. “How bad were your symptoms after the treatment?”

Yo crossed her arms and closed her eyes. “Let’s see... I got a pretty serious fever, but the blisters didn’t spread all over my body. Most of the other kids who got the same treatment had similar symptoms, or maybe slightly milder. A few of them hardly had any blisters at all, and their fevers went down after a few days.”

“So there are significant variations among individuals.” Maomao looked for a notepad so she could write all this down. Yo insisted it wasn’t worth it, but Maomao wanted to make sure she remembered.

“Yes, pretty significant, I’d say. It depends somewhat on each person’s physical size, but I suspect it mostly has to do with the amount of the toxin they were exposed to. You’re working with scabs, right? So it’s hard to make sure everyone gets exactly the same amount.”

Maomao hmmed and crossed her arms. Yo was intelligent: She could speak objectively while including elements of her own observations and suppositions.

“What happened to the people Kokuyou didn’t treat?” Maomao asked.

“My father had had smallpox before, so he just had a minor fever. Everyone who was strong enough left the village when the outbreak began. The only villagers left were my family and a few children. Oh, and one adult survived. Everyone else was killed.”

So it wasn’t the case, evidently, that once you had smallpox, you could never get it again.

“That’s terrible,” Maomao said. “What did you do with the bodies?”

“We burned them and then buried the bones,” Yo said after a moment of hesitation. “And the houses.”

Smallpox could spread just through old scabs. Simply burying the bodies would have been too dangerous. Yet some considered burning a corpse to be blasphemous; doing so must have taken no small amount of courage.

“That’s when all of you came to the capital together.”

“No, not all of us. The one other surviving adult outside my family went somewhere else. But I want you to know that we were careful to disinfect our clothing before we came into the city, and to be sure that we had completely healed.”

She wanted to emphasize that she had not brought plague into the royal capital.

“I know,” Maomao said. “And I won’t tell anyone about what you did with the corpses.” She was starting to think that she would have to interrogate Kokuyou a bit further about smallpox treatment.

I can check with Pops too.

There were plenty of other capable doctors around as well. The older ones might remember something about that outbreak of smallpox.

With all this chatting, Maomao suddenly discovered they were done with their work. “I’m going to take the medicine you’ve made—come with me, please,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

They would leave the commonly used medicines at the medical office. “We might encounter some rough customers, but just stick with me. Don’t let them see that you’re afraid, no matter what they say to you,” Maomao told Yo.

Maomao’s office was near the training grounds where the soldiers practiced, which meant there were a lot of, in her words, rough customers. Yo might still be a bit countrified, but Maomao couldn’t have anyone laying a hand on her dear younger colleague.

As they passed by the young men, the soldiers shot them appraising glances. Yo stiffened slightly; Maomao trotted along as if nothing were happening.

When they arrived at the medical office, the elderly doctor was chasing out a soldier who’d come in with a graze. “You call that an injury? That’s nothing. Get out of here!” He might look like a grandfatherly old man, but he was an experienced hand in this office and was used to things getting a little mean.

“Couldn’t you have just slapped some salve on it to put his mind at ease?” asked Dr. Li, who as a fellow bodybuilder had some sympathy for the soldier.

“I cleaned the injury,” the old doctor shot back. “Look, that was the guy who was guffawing about breaking one of the other men’s arms the other day. If he thinks he deserves kid gloves, he’s going to find all I have for him is some spit and polish.”

“Ahh, one of those gutless wonders, eh? I daresay you should have rubbed salt in the wound to disinfect it,” said Dr. Li, who sounded more like a musclebrain every day.

“I have medicines to deliver,” said Maomao, entering the office and taking off her portable medicine cabinet.

“Delivery’s here,” Yo echoed, imitating Maomao.

“Well, well, what a sweet young thing you’ve brought with you today,” said the elderly doctor.

“My name is Yo,” she told him. “I just started this year.” Evidently this was the first time they had met.

“We don’t get a lot of young ladies around here. Too many rough-and-tumble types.”

“I’m here,” Maomao said stiffly.

“You and Miss Chue are special cases. In flower terms, I would say you’re an obako and a dandelion.”

So she was in the same category as Chue now?

Dr. Li and the elderly physician were both relatively decent toward young women, so Maomao didn’t worry about having Yo there. If anything, it made her acutely aware that those in charge must have been thinking the same thing when they assigned Maomao to this office.

That was enough chitchat as far as Maomao was concerned. She resumed her delivery.

“When you deliver new medicines, check the date on any medicines left over,” she told Yo. “Put the ones with the oldest date on top, and if they’re too old, throw them out.”

These deliveries were regular affairs, so they didn’t throw too much out. Unlike the rear palace medical office, this was a proper place of business.

I wonder how the quack doctor is doing, Maomao thought.

Luomen was there now, so the rear palace medical office was probably running smoothly. If Maomao had any concerns, they were mostly for the quack doctor’s job. It appeared Luomen had been given some new task, however, and Maomao did worry a little bit about how things would go from here.

She noticed there were no injured patients around at that moment, so without slowing in her work, she decided to broach the subject she’d been wondering about. “Have either of you physicians ever had smallpox?”

Yo looked mildly shocked, but she didn’t stop refilling the medicine.

“The pox? Doesn’t everyone get that?” Dr. Li asked.

“I think you’re thinking of something else,” Maomao replied. He was probably imagining not smallpox, but chickenpox. Most people did get chickenpox when they were children. Maomao wasn’t much clearer on the distinction than Dr. Li was, but smallpox brought you a lot closer to death.

“I have,” said the elderly physician, rolling up one of his sleeves to reveal a red pattern on his arm, visible among the spots on his skin. The marks on his arm were much denser than those on Yo’s.

Presumably he was only so willing to show his scars because he’d had the disease a long time ago, and everyone in this room understood that he was no longer contagious. Dr. Li, just like Maomao and Yo, looked impassively.

“You’re not afraid?” the elderly doctor asked Yo.

“No, sir. I know I can’t catch it from you.”

“That saves me having to explain, then. Excellent.” The physician was relieved by Yo’s attitude. Maomao suspected Yao had long ago chased out any palace ladies who would have quailed at the sight.

“Judging by the extent of your scars, it looks like it was a serious case,” Maomao said.

“I suppose so. They cover half my back as well. It’s not that rare among people of my generation. It was going around at the time, you see. But my first wife looked askance at it.”

“First” wife, huh?

“What about the second?” Maomao asked promptly.

“She’s a good woman. She’s at home, watching over our great-grandchild.”

“Wait...are you feeling lovey-dovey?” Maomao said. The elderly physician only smiled and rolled down his sleeve. “If you’ll forgive me saying so, sir, I’m impressed you survived.”

“That’s fair. At first, we thought it was just chickenpox, but then the symptoms grew more serious. If I hadn’t come from a family of doctors, I’m sure I would have died.”

“I’m afraid I don’t really understand the difference between chickenpox and smallpox,” said Dr. Li, and Maomao nodded.

“Yes, well, they do look very similar, although one is much deadlier than the other. I’ve heard some suggest that the toxins that cause those two diseases must be somehow similar, but not exactly the same.”

The elderly physician opened a desk drawer and took out some tea candies, looking for a little break. He offered them to Maomao and the others; Maomao for one accepted them gratefully. Yo looked hesitant, but since this was a venerable old doctor encouraging her to partake, she couldn’t really say no.

It was only because the factional fighting among the soldiers had calmed down that they were able to enjoy a quiet snack time like this.

“The toxins that cause those diseases,” Maomao breathed.

“Maomao, don’t get any ideas about trying them,” Dr. Li said.

“Of course not, sir,” she answered, albeit slowly, and averted her eyes.

“Not everyone is happy to see smallpox scars, but as a physician, they can have certain advantages,” the elderly doctor said. “For one thing, it shows you the terror of illness firsthand, and for another, it makes it harder for you to catch the same disease.”

“Yes, sir.” The response came not from Maomao, but from Yo. For her, the elderly physician might have seemed a savior of a kind.

I’m glad I brought this up while she was around, Maomao thought.

She’d known, at least, that these were not people who would take smallpox lightly; she would never have raised the subject in front of anyone who was likely to make fun of the scars.

“Then again, as you rise through the ranks, it can be a liability,” the elderly doctor went on. “If you have two physicians with the same qualifications, setting aside any noble background, they’ll take the one with fewer scars.”

Maomao was silent at that. Presently, Dr. Liu was the one in charge of the physicians. He was an excellent doctor, no doubt, but considering their ages, this old man could easily have outranked him. One presumed there were no issues with his abilities or his family background.

Maomao and the others began to feel a bit uncomfortable.

“Well, my dear Liu is a clever man, more gifted than I am, so there’s no problem there. I think I would be too frightened to be His Majesty’s personal physician.”

“His Majesty’s personal physician... I agree, I don’t have the stomach for it. I wouldn’t, no matter how many stomachs I had!” Dr. Li said.

Personal attendant to the Emperor, huh?

They were right; that was a job Maomao would never want. It brought honor with it, certainly, but even more, it brought responsibility. If the Emperor should fall sick or, heavens forbid, die, his physician might well pay with his life. Indeed, Luomen had suffered physical mutilation on account of a medical case involving the Imperial family.

I just hope they wouldn’t punish him again now that they’ve called him back...

Maomao sighed as she poured some tea.

“Oh, yes, that’s right,” the old doctor said, standing up and taking an envelope from atop his desk. “This came for you, Maomao.”

“You, er, don’t think you should have given this to me first thing?”

“My mistake. Us old folks can be so forgetful.”

Maomao took the packet. On the front in large letters was written NOTICE OF REASSIGNMENT.

Chapter 3: Reassignment

Specifically, it turned out, Maomao was being moved to another office. Her new workplace was the largest medicine-storage area in the palace. When she got there, she found others who had been reassigned as well—mostly the ones she expected.

“I haven’t seen you since...yesterday,” she said.

“No, not since yesterday.”

The other new faces were the three people who looked after the supplies, just like Maomao did: Tall Senior, Short Senior, and Middle-Height Peer.

“I was so sure I’d failed,” Middle-Height Peer said with some amazement. Luomen had criticized his preparation of the medicine during the test the day before.

At exactly the time stipulated on their orders, Luomen walked into the room. An assistant came in beside him, which was at least a sign that they were taking care of him.

“Now then, you’re the ones who passed yesterday’s test. We’re going to have you get right to work.” He set down a formula for a medicine. “For now, I’d like you to make some of this.”

With that, Maomao and the others found themselves furiously mixing herbs together for the next several days.

Grind, grind griiind, thought Maomao. She’d spent so many days mixing medicine that she thought she was going to get calluses from the mortar and pestle.

I mean, it’s okay. I’m having a good time.

The exact composition of what Maomao and the others were being asked to make changed sometimes, but all of the recipes used roughly the same components: antiseptics, drugs to make the blood flow better, and anti-inflammatory agents.

I do wish we could work on a wider variety. That was just her personal desire, however, so she kept it to herself.

“What in the world do you think we’re making?” asked the doctor of average height. He was still young, not much different from Maomao. A few years past twenty, she guessed. He seemed to be from Tianyu’s intake; she sometimes saw them talking together.

“Various ratios of rhubarb root and mu dan pi,” said one of the others. A medicine that would promote blood flow.

Luomen acted as teacher and guide to the three physicians and Maomao; today, he would be coming after stopping by the rear palace’s medical office.

“What’s the other stuff?” asked Middle-Height Peer, who knew the least of any of them, but was at least proactive about it.

“Licorice and garden peony—it must be a decoction of the two,” answered Tall Senior, the taller of the two seniors. Typically, Tall Senior would go out of his way to answer questions, while the more vertically challenged Short Senior would only offer an opinion if something annoyed him.

“I agree,” Maomao said. “It’s a drug to suppress muscle spasms.”

“And pain. It helps with back and abdominal pain,” snapped Short Senior.

“When a patient’s abdomen hurts, it can be used to help figure out exactly where the pain is,” Tall Senior explained.

I thought it had circulatory applications, but it’s a digestive drug?

A draught of rhubarb root and mu dan pi could be helpful in cases of constipation or stomachache and was frequently dispensed to women, as it also helped regulate periods.

Wonder what disease this is? Maomao thought, but she figured that when they saw the patients who were going to take the drug, they would find out.

Meanwhile, Luomen, of course, would not miss this opportunity to help them learn to think for themselves.

No sooner had Luomen finally shown up than he said, “We’ll go to deliver the medicine now. Everyone come with me.” There was a carriage waiting outside; clearly, they were expected to do as they were told.

They rode along for thirty minutes until they arrived at a mansion on the outskirts of the capital. Well, a big house, anyway; it wasn’t really elaborate enough to be called a mansion. It was situated in a residential area, but surrounded by gardens so that no one could see inside.

“Bring the cargo,” Luomen said, and the three physicians did so. There wasn’t that much of it, so Maomao stood with Luomen and helped him to walk. Evidently his assistant wasn’t with him at all times.

Don’t mind us, she thought as she came into the house.

The moment she entered, she caught the distinct aroma of medicine. A man wearing a white apron came out to meet them. “I’ve been waiting for you,” he said.

“I’ve brought the medicine, along with some helpers. I have to explain to them what’s going on, so please, go back to your work.”

“Yes, sir,” the man said and went away.

“Helpers?” Maomao asked. “What does that mean?”

“Just what you think. Or don’t you wish to look after patients?”

“That’s not what I meant,” she said, unsure how she should have asked the question.

Maybe I should have asked why we’re doing this...or who for. She wasn’t sure if it was safe to ask that, however, so she just followed Luomen.

Far inside the house was a room full of cots. The patients were all men, ranging from their teens into their forties. Folding screens had been set up between the beds to give a modicum of privacy. There must have been nurses or caretakers of some kind, because the bedding and the nightclothes the men wore looked clean.

Their pallor is poor, and there are buckets by the beds. Vomiting?

The patients appeared to come from all walks of life. The ones with gnarled hands and legs and tanned skin might be farmers. The ones with knobs on their fingers, maybe scribes. They didn’t seem to have any one thing in common except for their gender.

But then, they’re all taking part in a medical trial.

It meant they weren’t exactly affluent.

There were other people walking around in white aprons—medical personnel, perhaps.

“We brought the medicine,” Luomen said to one of the men who looked like staff.

“Thank you very much.”

“Since we’re here, I thought we might check the stores. All right with you?” Luomen asked.

“Yes, please. If you’d be so kind,” the man replied.

Luomen led Maomao and the others to the place where the medical supplies were kept, next to the galley. Two medicine cabinets sat there, still new.

“I’ll parcel out the medicine. Would you hand it to me?” Luomen asked.

“Yes, sir.”

The medicine was already divided into single doses in paper packets. Luomen proceeded to put them smartly into the cabinet drawers.

Not much for us to do, Maomao thought. The three physicians didn’t foist any random chores on her, so it was all too easy for her to find herself with time to kill. She filled some of it by taking a good look around.

The place looked like it had been an ordinary residence that had been hurriedly converted into a clinic. It was full of familiar tools: mortars and pestles, sifters and dispensing spoons.

Are they making medicine here too? Maomao sniffed. It doesn’t smell much like medicine. It smells...almost sweet.

Still sniffing, she stepped down to the area where the floor was made of exposed dirt. She saw a stove, on top of which sat a pot with dark, viscous liquid inside.

Refined honey?

This was honey with the water removed, and it would be formed into pills—except that she didn’t see any of the herbs with which it would normally be mixed. Instead she saw wheat flour and buckwheat flour, perfectly ordinary baking supplies.

“Buckwheat flour...”

Maomao stepped gingerly away from the bag full of flour and put a handkerchief over her nose. She had difficulty breathing whenever she ate something with buckwheat in it; she certainly didn’t want to inhale the stuff.

“Maomao! Don’t go fiddling with things. Come back over here,” Luomen said.

“Yes, sir,” Maomao answered. Her father sounded a touch panicked, maybe because he knew there was buckwheat flour around. When he saw the handkerchief over her mouth, his face showed that he realized he was too late.

There were a lot of other odd things as well. For example, the two medicine cabinets had exactly the same shape and arrangement. Each had the names of the medicines written on the drawers, but every drawer in both cabinets appeared to contain exactly the same things.

So why would they bother to have two cabinets?

Just as Maomao was wondering about this, one of the men in an apron came up.

“It’s almost time to give them their medicine,” he said.

“Of course; I see,” Luomen replied and stepped away from the cabinets. The man took five doses of the medicine they had just replenished. Then he took five more from the other cabinet—of exactly the same thing.

Maomao wasn’t the only one who found this strange. “Dr. Kan,” said Tall Senior, raising his hand. “May I inspect the contents of the other cabinet?”

“Go ahead,” Luomen said.

With his approval, Tall Senior took a packet from the second cabinet and opened it. Maomao and the other physicians crowded around to look.

“You keep your distance, Maomao,” Luomen said, and she backed off. The pills in the packet were of a brown color; if she squinted, she could see black specks in them. “Is that...buckwheat flour?” she asked.

“One presumes that’s one of the ingredients.”

The pill was made of wheat and buckwheat flours and dyed to make it look like medicine—but it wasn’t.

“So this cabinet has fake medicine that doesn’t do anything?” Middle-Height Peer said in some distress.

“Keep your voice down,” Luomen warned him.

“But sir! Why would you do such a thing?!”

“Think it through and see if you can’t tell me.”

When Luomen told you to think, there was nothing for you to do but think. He only asked questions that could be answered, with enough consideration. If you couldn’t come up with the response, it only meant that you had missed some information somewhere.

Earlier, that man took five packets out of each cabinet. There are ten patients, which means the medicine is being divided in half.

The patients were shown a certain level of hospitality while being treated here. They were probably getting decent food, for one thing.

You make sure everyone is in the same environment to judge the effect of the medicine.

It was always possible that the medicine wasn’t what was helping, but simply being in a clean environment and getting proper nutrition. In that case, you couldn’t always be sure the medicine was working, and that was no good. So it was necessary to prepare two separate groups.

“You’ve figured it out, Maomao?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And what do you think?”

The three physicians all turned to hear her answer.

“I think you’ve divided them into two groups to ascertain the effect of the medicine while ruling out the effect of changes in environment or diet. You want to see if people in the same environment with the same illness will show different results based on whether they receive medicine or not.”

Luomen was smiling, but he didn’t look quite convinced.

“Further, the reason you deliberately prepared some medicine that will presumably work and some placebos is—”

“Thank you, that’s enough. There’s someone else who looks like they can give us an answer. Let’s hear it from them.”

Maomao looked over, feeling a touch of mental indigestion. Short Senior was looking especially engaged.

“It’s in order to equalize not just their basic needs, but their feelings as well,” he said. “It’s said that illness begins with the spirit, but so can treatment. The relief provided by the sense that they’re taking medicine can lead a patient to feel that they’ve been cured.”

“Correct. Strangely enough, the very feeling that one is taking medicine can cause the body to produce the illusion that the medicine is working. These pills are to help account for that.” Luomen picked up one of the fake pills. It was quite a piece of work, designed so that even the color was believable. “In addition to your usual production of medicine, I want you to take shifts to record the condition of the patients here. Is that all right?”

“Yes, sir,” Maomao and the others answered in unison.

At least we finally know what we’ll be doing, she thought. But she still hadn’t had a chance to ask why.

Chapter 4: Drug Trials

At Luomen’s direction, Maomao and the others began commuting to the clinic on the edge of town. Still, the four of them weren’t enough to keep the place constantly staffed. The clinic already had nurses of its own, and it was much more efficient to make medicine at the medical offices in the palace.

“I’d like to suggest we work in pairs,” said Tall Senior, summing up the situation. “At the clinic, we’ll make records and look after the patients, while at court we’ll continue to make medicine like always.” It was nice to have somebody taking charge.

“How are we going to pair off?” asked one of the other physicians.

“I think for starters, the oldest of us should split up.”

That makes sense.

The two older doctors knew what they were doing, so they would be able to keep their younger colleagues from getting into any real trouble.

“First, Maomao and me,” said Short Senior, so that’s who Maomao was paired with. They decided to have the junior and senior colleagues work as pairs, occasionally trading off. “Good to work with you,” the doctor said.

“And you,” Maomao replied politely. Short Senior didn’t talk as much as Tall Senior, but it was clear that he was very capable. He was somewhere in his early thirties, and probably knew a bit more than Tall Senior, who was roughly his same age. He was a careful worker, fastidious in the way he made medicine. His nimble hands suggested he was probably also an excellent surgeon.

So he could have been in surgery...

The fact that he was nonetheless doing apothecary’s work suggested that he loved drugs just like Maomao did.

Short Senior’s small stature and average looks made her think of a certain abacus-brain (who shall remain nameless), but this man was far more mature.

“All right, shall we go?” Short Senior said.

“Yes, sir.”

Since they would have to bring cargo with them, a carriage would be provided for trips from the court to the clinic. It wasn’t that they couldn’t possibly walk, but they would have to cut through the shopping district on the way, and it was all too likely that they would encounter a pickpocket. Soldiers might travel through unharassed, but a couple of well-dressed civil officials? They’d look like marks all the way.

Maomao and Short Senior arrived at the clinic and replenished the medicine with the supplies they had brought.

“Should we go straight into checking on the patients?” Maomao asked. She’d brought a tie for her sleeves so they wouldn’t get in her way. Now she rolled them up and tied them back so she could move freely.

“No, I think we should start by checking the records,” said Short Senior, grabbing the book where the notes were kept.

Maomao simply had to look on. She suspected they used paper and not wood strips because of the sheer quantity of writing. But she noticed to her dismay that the paper wasn’t of very good quality.

They should get in touch with the quack doctor, have him sell them some at a decent price!

The quack’s family made paper for a living, so Maomao occasionally went to him for a friends-and-family rate on quality material.

The book didn’t record the patients’ names, but it did include their ages and physical sizes as well as their occupations and other details.

“Looks like there used to be a lot more patients than there are now,” Maomao observed. The drug trials appeared to have started about a month prior with around thirty people. Now only a third of them were left. She’d wondered why the clinic seemed so large for the number of patients, and this explained it.

“Sounds like some people were faking,” Short Senior said.

“I can see why.”

Yes, the physicians were developing drugs, but they were offering free treatment, food, and so on. Who could blame a few people for showing up claiming to have the condition the doctors were looking for?

“A few other people left because the medicine couldn’t help them,” Short Senior went on.

“Right.” If the physicians decided the drugs weren’t going to cure you, they would ask you to leave.

“What condition do you think it is?” Short Senior asked.

“Typhlitis, maybe?” Maomao suggested.

“I think so too.”

No specific name of an illness was written down in the book of notes—after all, they’d only assembled patients showing similar tendencies; they couldn’t be certain what disease each had.

“Typhlitis...”

Maomao had dispensed medicine for this condition more than once. On most of those occasions, she’d given out drugs much like the ones being administered to the patients here.

Typhlitis, huh...

Maomao made a thoughtful noise. The condition involved the inflammation of an organ called the cecum. It was possible to relieve the symptoms with medicine, but that was all they were doing—treating symptoms. Some people got better, if their symptoms were mild, but in more severe cases the inflamed area could fester and spread toxins through the body. In such cases, it could spawn other illnesses, and mortality rates went up. She’d heard that more than half of people in that situation died.

It was a decent idea to study the treatment of typhlitis, because it wasn’t particularly uncommon. She wondered, however, why they were using court physicians to conduct such large-scale drug trials.

And there were two other groups too.

Were they also researching the treatment of typhlitis?

Those thoughts led to a natural question.

Who are these experiments being done for?

Maomao knew that it was not a question she could ask, however much she might want to.

“Whatever disease it is, I suppose we should get to work,” said Short Senior.

“Right.” For the moment, getting down to business would be better than pursuing questions she wouldn’t get an answer to.

First, she got an overall view of the situation: She went around checking on the patients.

They were divided into two large rooms, five in each—but this did not correspond to the groups receiving the real medicine and those getting the placebo.

That would be the wrong way to go about it.

It did mean, however, that she would have to be careful to make sure the right people got the right pills.

As for food, the patients got three meals a day—all congee, good for the digestion. The ingredients were finely chopped, and the porridge was thoroughly cooked. It didn’t look like much, but the stock had been made from meat and bones to give it plenty of nutritional value.

If someone had stomach troubles, typhlitis or not, food that was easy to digest was the basic treatment.

Maomao went among the patients, organizing the information in her head. Then she and Short Senior moved to the kitchen so that the patients wouldn’t overhear them.

“It does seem to be the case that the patients receiving the real medicine are in better shape,” she said.

“Yeah. Inflammation’s gone down for some of the ones in the placebo group, but not many.”

“Probably the ones with the most physical vitality.”

In an experiment like this, the more people you could get, the more precise your results would be. Testing on human subjects meant there would be differences from one individual to another, but increasing the number of subjects would help average out the data.

If Lahan were here, he would be adding them up already.

Which did not mean she was going to call him.

“Master Physician,” she started.

“Yeah?” asked Short Senior, who was writing something. She was glad they were alone and she could get away with simply calling him “Master Physician.” She could hardly ask his name at this late date.

“If a case of typhlitis doesn’t get better with medicine, what exactly is the subsequent treatment?”

Whatever it was, Maomao, unfortunately, hadn’t learned it. Her specialty was herbs and medicine, after all.

“You could open their stomach and take out the filth,” Short Senior said.

“Would that solve the fundamental problem?”

“I’m not sure. Maybe not.” Short Senior didn’t sound like it much concerned him.

“Have you ever done that operation?” Maomao asked.

“Never. I doubt I could.” Short Senior scratched the back of his neck with the barrel of the brush uneasily.

“Why not? You look like you would be good at surgery.”

Maomao could see how well Short Senior used his hands. Even his handwriting was neat, although she didn’t know if that made someone a better surgeon.

“No, I... I couldn’t. Can’t.”

“Can’t?”

“It’s...blood. I can’t stand...blood.” He sounded embarrassed.

“Ahhh.” Maomao definitely understood that. Everyone had certain things they just didn’t cope well with. That was life.

“I’m not actually cut out for doctoring,” Short Senior said. He came, however, from a long line of physicians, and had been pushed to take the medical exam whether he wanted to or not. It would have been so easy for him if he’d failed, but other than his aversion to blood, he was really quite talented.

“Honestly? I’m in hell,” he confessed. It was hard when you had the skill but not the aptitude for a vocation.

“You have my sympathies” was all Maomao could say.

So it was that they decided to divide the labor between them while they were there at the clinic. Short Senior couldn’t stand blood and Maomao couldn’t stand buckwheat, so they would cover for each other’s weaknesses. They were just giving the patients pills, so there wasn’t likely to be blood involved, but then one time someone going to the bathroom had taken a bad step, tripped, and split his forehead open, so Maomao had been the one to treat him. Meanwhile, she left it to Short Senior to make the placebo pills.

Short Senior always looked like he really had it together; somehow, learning about his vulnerability like this made her feel closer to him than she had before.

Chapter 5: A Book Restored

Maomao headed back to the dormitory, her first day of work at the clinic over.

“Hullo, Miss Maomao!”

“Hullo, Miss Chue.”

Maomao understood why Chue was there, and when the other woman beckoned, Maomao followed her. As she expected, a carriage was waiting, and she was to get on.

“Who’s summoning me today?” she asked. It was presumably either Jinshi or Ah-Duo.

“The Moon Prince today,” Chue drawled. “Also, there’s someone already in there, so have fun!”

“Someone already in there?”

A pair of eyes goggled out at Maomao from the carriage window.

“Hullo, Niangniang!”

(No reply from Maomao.)

It was Tianyu.

She could think of only one reason Jinshi might call for her and Tianyu.

Is this about Kada’s Book?! she thought, nearly breaking into a giant grin. Among Tianyu’s ancestors was a physician who, although a member of the Imperial family, had committed an unpardonable crime. Just the other day, they had found the book this ancestor had left behind.

He did say they were repairing it...

Maomao bounced along in the carriage, barely able to contain herself. Before she knew it, she was even humming.

“Is it just me, or does Niangniang seem kind of...creepy today?” Tianyu asked.

“Now, now, you mustn’t say such things,” Chue drawled. “Didn’t the neighborhood uncles ever tell you that?”

“Dr. Liu has definitely gotten mad at me a few times.”

They were having a huddled conversation, but it was very much in character for them that they made sure to have it loud enough that Maomao could hear them.

Say what you want, she thought. Her head was too full of Kada’s Book to care about anything else. What might be written in it?

“Okay, from here, we walk,” Chue said. The carriage had stopped, but not in front of Jinshi’s palace. “We’ll be in here today!”

They were somewhere near Jinshi’s office. Outside of work hours, Maomao was usually shown to his pavilion, and it had been a long time since she’d come to his office.

“Hey, Niangniang, what are you doing these days?” Tianyu asked, obnoxious as ever. In fact, though, Maomao had exactly the same question.

What’s he doing these days?

If he’d passed the selection examination, he had presumably received reassignment just like she had.

“What about you?” she shot back. “What are you doing?”

“Take a guess.”

Tianyu showed her the palms of his hands. Maomao studied them intently; Chue imitated her.

I see calluses.

Just as those who wielded the sword could develop calluses on their hands, so, too, could those who wielded the brush get them on their fingers. Tianyu’s calluses, however, probably came not from a brush but from a scalpel.

The pad of his pointer finger is red.

A red line ran down the side of the finger, showing that he had been holding a scalpel for a very long time.

Doctors used scalpels when cutting skin. Had he been performing autopsies?

No, I don’t think so.

Tianyu’s eyes had gone beyond shining to outright sparkling, like those of a cat who had finally spotted a flesh-and-blood rat instead of a toy fluff ball.

“Are you operating on living people?” she asked.

“Wooooh!”

His reaction suggested she was correct.

Maomao wasn’t sure they should be discussing surgery right in front of Chue, but it was probably useless to try to hide anything from her, and besides, she had to suspect that doctors did that kind of thing. Maomao decided to just go ahead and entertain the subject.

She thought she could see how this worked: Patients whose condition was not helped by the drug trials were moved on to surgery.

“Are you cutting them open and removing the filth?” she asked.

“Have you learned to read minds since I saw you last, Niangniang?” Tianyu asked, a theatrical expression of befuddlement on his face. It was not as cute as he thought it was. Chue was doing the same, but at least with her it was sort of cute.

The conversation had taken them almost to the doorstep of Jinshi’s office.

Wow, this really takes me back.

Maomao saw hallway windows that she had polished the hell out of when she was Jinshi’s serving maid. And she’d had more than a few tussles with other palace ladies there.

There were no officials in the halls now; it was almost dark.

Now that I think about it, this is the same office he had back when he was a “eunuch.”

She was only now realizing. She might have expected him to find a new place once it was public knowledge that he was the Emperor’s younger brother, but not so. The current location was just too convenient.

Two guards stood outside the office. Chue greeted them, and they stepped away from the door in an unspoken command to enter.

“Hellooo! Pardon me?” Tianyu called as he entered the office. The gravity of the moment didn’t seem to have any impact on his attitude.

Maomao, meanwhile, tried to steady her breathing as she entered the room. I have to calm down. I don’t know for sure that this is about Kada’s Book.

As soon as she saw who was inside, however, any thought of remaining calm fled her mind. This was more than enough reason to get agitated, although it had nothing to do with Kada’s Book.

“It’s been much too long,” said the other person in the room. He was a young man, not yet twenty years old, who bowed his head in a show of humility. His deferential attitude might be enough to fool some people, but his name was violent and beastly: Hulan, which meant “tiger and wolf.”

Maomao had half a mind to send a flying kick straight into him, and her body was already nearly moving, but Chue took her firmly by the hand. “Dignity, Miss Maomao, dignity,” she advised. “I know how you feel, I really do, but we must comport ourselves properly.”

Chue was very strong; even with one hand she could keep Maomao firmly in place.

“Just an arm. Just one arm,” Maomao begged. If she could just break one of his limbs...

“That’s not dignified,” Chue repeated. “Let’s at least wait for a moonless night.”

Hulan was the reason Maomao had been chased all over I-sei Province and ultimately nearly killed by bandits. And Chue had as much reason to hold a grudge against him as Maomao did: It was because of him that she had lost the use of her arm.

“I must say, you’re both looking very frightening tonight,” Hulan said. The complete lack of venom in his smile made him all the more grating. Maomao’s hackles went up and she gave him a threatening look.

“Ha ha ha! You’re even less popular than I am!” Tianyu chortled. Evidently he actually was bothered by the general distaste people had for him.

Maomao had had to see Hulan on the hunt the other day, and she was aggravated to now find him here in Jinshi’s office.

“So you’ve arrived,” said Jinshi, who was seated in a chair waiting for them. Basen stood beside him as his bodyguard. A curtain, otherwise out of place, hung across a corner of the room, meaning Baryou must be with them as well.

“Good evening, Moon Prince. Incidentally, I believe there’s someone present who has no business being here. Do you not see fit to chase them out immediately?” Maomao asked with her most humble attitude.

“You don’t mean me, do you?” Tianyu said, pointing at himself. Sadly, no; today, she did not mean him. There was someone even worse than Tianyu there.

“Why, whomever do you mean?” Hulan asked, looking innocent.

“Now, now, you must be able to see things objectively. Shall I bring you a mirror?” Chue said, backing Maomao up.

“Miss Chue, Miss Chue, I have a mirror,” Maomao said, taking a small bronze plate from the folds of her robes.

“I should have known you would be prepared, Miss Maomao.”

Jinshi watched this exchange with exasperation. “I fully understand what you’re trying to say, believe me, I do, but as I’ve told you before, this man is capable. So just live with it. Also, I’d rather he be where I can keep an eye on him.”

“Wait...is it moi you’ve been talking about all this time?” Hulan put on his surprised face. His features were young and cute; they were the only cute thing about him.

Jinshi got a bit of a faraway look in his eyes. Hulan was, after all, publicly the younger brother of the ruler of the western capital, so Jinshi couldn’t afford to ditch him outright.

“I’m sorry, but I have no time to chat with people who might as well be animals. Could we get straight to the point?” Maomao asked, collecting herself. “And incidentally, what is the point? I know it’s got to be the...you know. You know.”

“It looks like you don’t need any help from me to imagine why I might have called you here,” Jinshi said. “But in any case, calm down and have a seat.” He made a motion as if gesturing to a dog to sit.

Maomao seated herself on the couch, although she fidgeted furiously. Tianyu sat down too, and Chue planted herself between them.

“Why are you sitting, Miss Chue?” Maomao asked.

“Miss Chue is putting herself on the line—it’s very valiant of her,” Chue said and winked broadly at Jinshi. He didn’t say anything, but he nodded at her.

There were no palace ladies present, so Hulan made tea. Maomao folded her legs to one side and made it her business to look annoyed. She glowered at the tea he gave her and gave it a good sniff, making sure there was no poison in it.

“You’re not being very polite, Niangniang,” Tianyu said, adding dramatically, “That’s not very nice.”

“I’m simply behaving as befits the person I’m interacting with,” she replied. Tianyu was hardly comporting himself with the formality one might have expected before Jinshi. He seemed to have the same attitude as Maomao: that if Hulan could be permitted so much, then so could they.

“I’m sorry to tell you there’s no poison in the tea today,” Hulan said apologetically.

“Yes, what a shame. It would make Miss Maomao so happy, and give the Moon Prince such a fine excuse to execute you,” Chue said.

“My dear older sister Chue. You’re so cruel to me.”

Sparks flew between Chue and Hulan even more than between Hulan and Maomao. It evidently wasn’t the first time this had happened; Basen’s expression clearly said, Again?

The discussion was never going to get anywhere at this rate. Maomao looked at Jinshi. He looked back with unusual seriousness. “Before we go any further, there’s something I want to say to you, Maomao.”

“What is it, sir?”

“First, calm down.”

“I am calm, sir.”

“Don’t fuss.”

“I’m not fussing, sir.”

“Steady yourself.”

“I’m steady, sir.”

“You’re ready now?”

“Yes, sir.”

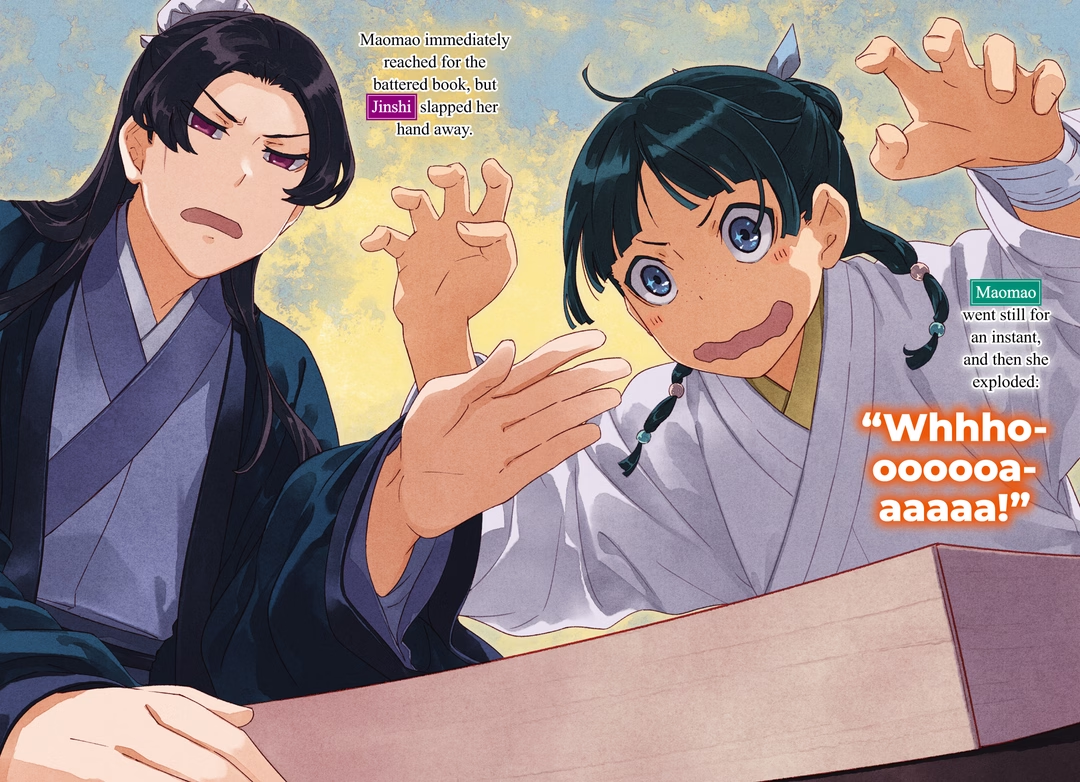

After all that, Maomao was fairly sure she was actually calm—until the moment Jinshi took out a paulownia-wood box and opened the lid, revealing battered old pages sitting on top of some white paper.

“This is from the restored Kada’s Book,” he said.

“Ka...da...?” Maomao went still for an instant, and then she exploded: “Whhhooooooaaaaaa!”

Yes, she’d known. She’d understood what they were there for. And yet on hearing the name, she couldn’t restrain her excitement.

“She’s not very calm,” Tianyu said.

“Dignity, Miss Maomao!” Chue added. They both turned to stare at her.

Maomao immediately reached for the battered book, but Jinshi slapped her hand away.

“Wh-Whyyy?!”

“Look at it—this is after we restored it! If you just grab it in a fit of rapture, you’ll destroy it, and then no one will be able to read it!”

“Of course, sir, I know that. I’ll be gentle with it. So please, please, please, pretty please let me see it!”

Maomao straightened up and looked at Jinshi with her most serious expression. With no small amount of trepidation, he handed her the book.

“It looks like it was originally bound like a sutra,” she observed.

“Indeed. We cut it apart so it would be easier to repair.”

Sutra construction was also called a folded book. As the name implied, it was made by folding the paper over.

Maomao studied the restored book intently. Tianyu trotted over, but she shoved him aside; he was just getting in the way.

Does it have anything about smallpox?

The book was a hundred years old, so the characters were considerably different from the way they were written today. They were also faded in places, making the text supremely difficult to read. Notwithstanding those hurdles, however, she definitely wanted to read this book.

“There. It talks about the smallpox outbreak a hundred years ago,” she said. It was what she happened to be interested in at the moment, so she seized on it immediately. Tianyu, meanwhile, wasn’t particularly moved; smallpox wasn’t dissection, after all.

What mattered in medicine was quantity of case studies and records of attempted treatments. Anything showing repeated attempts—and often repeated failures—to treat a disease would help bring future medicine closer to the right path. That’s what made these old pages so important.

And details there were: how the disease had spread, how it had been treated.

Let’s see, they dealt with it by...

But the page happened to be cut off right where Maomao might have found the answer to her question. They must not have restored that part of it yet.

“Are these all the pages you have?” she asked.

“The rest are still being repaired. Would you like to see for yourself?” Jinshi stood up and crooked a finger at them to follow him. They left the office, but they didn’t go far—only about two rooms down the hall.

“What’s this?” Maomao asked. The room was filled with a distinctive, pleasant humidity and suffused with the scent of paper.

There was hardly anyone there—one person at the door and another within, working. Considering that it was after hours, these people must have received special permission to be here. They were dipping the paper into what appeared to be water and endeavoring to peel apart stuck pages.

The fire that provided illumination wavered. It was surrounded by metal to make sure the flames couldn’t catch any of the paper—a wise choice under the circumstances.

That does not look like easy work, Maomao thought—but the men had been told to work fast, so work fast they would.

“We’re having it specially restored, but given what’s in this book, we can’t exactly have a crowd of people working on it. As you can see, it’s rather...small-scale in here,” Jinshi said. Neither the contents of the book nor its author could be made public. “The in-progress work is here.”

Maomao’s eyes shimmered, but no matter how she squinted, she couldn’t read the pages. The paper was yellowed and the characters had begun to run; by the flickering firelight, they almost looked hazy. As poor a shape as the pages Jinshi had shown them earlier had been in, it was painfully clear how much work had been done to make them more readable.

“The pictures are pretty easy to see,” Tianyu said, and Maomao looked at the other pages currently under repair.

The pages had been lined up one beside the other. They were weathered, with stains and smudged characters, but there were also pictures depicting what appeared to be a human body.

“Oooh!” Maomao said, her eyes making perfect circles.

There were detailed illustrations of medicinal herbs. The most prominent one, however, was of a dissection. It showed the insides of a person in great detail. It was smudged in places, but easier to make out than the writing.

Tianyu said this was one of his ancestors, right?

It was a living demonstration of just how thick blood could be. Tianyu was poring over the illustration, making sounds of amazement. Maomao, too, stared fixedly at it.

She didn’t say anything.

He didn’t say anything.

Chue didn’t say anything.

“Somebody say something!” Jinshi demanded, looking straight at Maomao.

“Sorry, sir,” she replied, her eyes still glued to the pages.

What was more, as far as she could tell from the picture, unlike the earlier pages, this one dealt with diseases of the internal organs, and it mentioned typhlitis. Maybe that explained why Tianyu was as silent as Maomao.

At length she told Jinshi, “This is a very interesting book.”

“I can’t say I find it very engaging,” Jinshi said, squinting at the picture of the autopsy.

“They may have ignored common morals to do it, but they didn’t do it by half measures—that’s what makes the outcome so intriguing.”

“And you can sleep at night, thinking like that?” Jinshi shot back.

As Maomao looked at the image of a human being lying there in pieces, she contemplated how different the value of a human life had been a hundred years before. It appeared that if the surgery had been successful, the authors wrote down its subsequent progress, while if it failed, they autopsied the body and made illustrations of it.

They didn’t waste anything.

“Do you think their patients were slaves?” she asked.

“It’s a likely possibility.”

Cutting open someone’s belly was almost unthinkable. Even a dead person had to be treated with respect. That, at least, was the common consensus.

In practice, the only people doctors cut up to learn more about how humans were built were criminals. In the same way, if they were going to do experimental surgery, outside of extraordinary circumstances it was unlikely that they would use ordinary people. Maomao didn’t know what had passed for “common sense” at the time, but it seemed plausible that the physicians would have been using criminals or possibly slaves in their research.