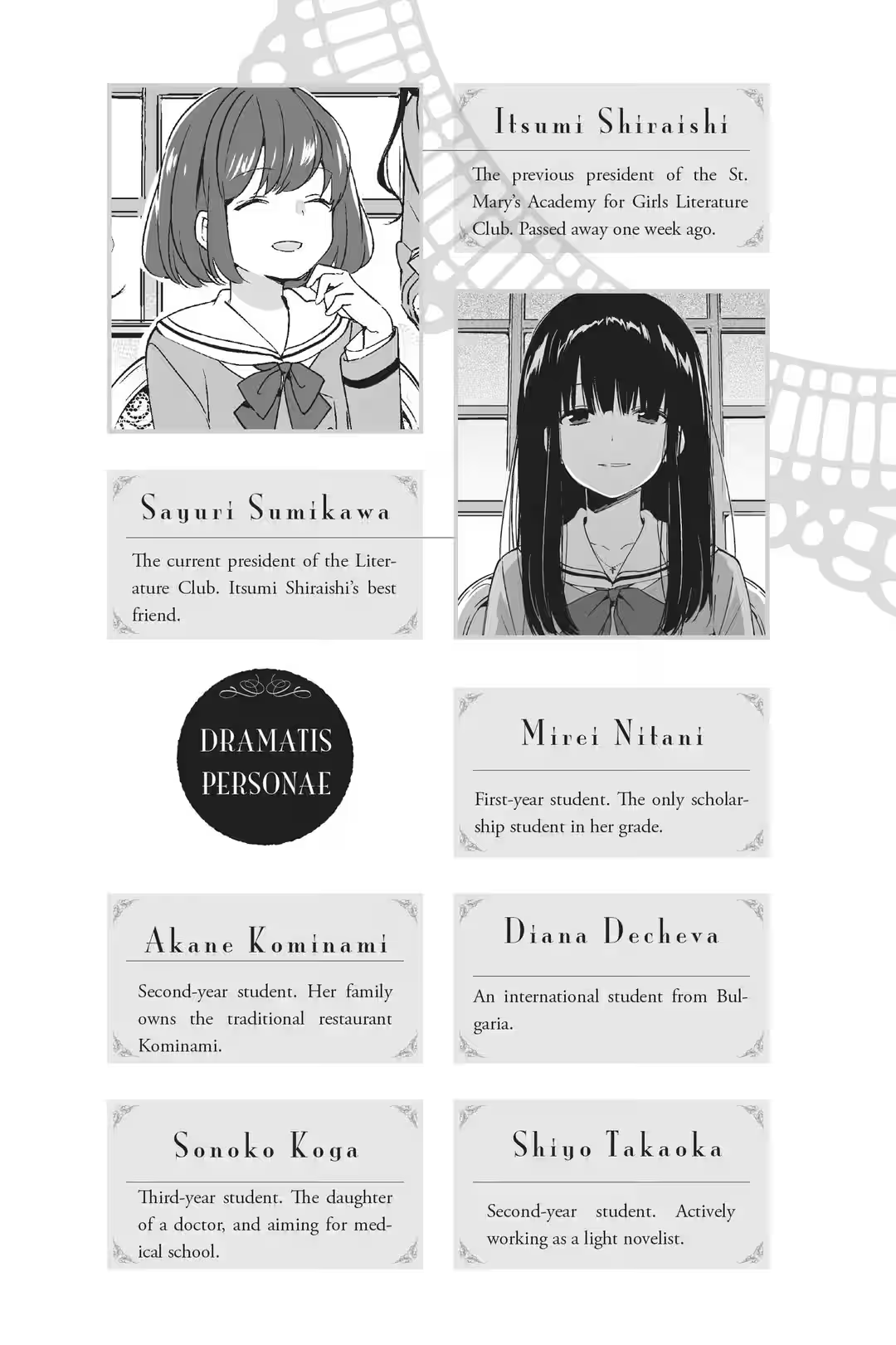

THE 61st MEETING OF THE ST. MARY’S ACADEMY FOR GIRLS LITERATURE CLUB MEETING PROGRAMME

1. Official Greetings & Rules for the Mystery Stew

Club President, Sayuri Sumikawa

2. Short Story Reading — “Where I Belong”

First-year Class A, Mirei Nitani

3. Short Story Reading — “Macaronage”

Second-year Class B, Akane Kominami

4. Short Story Reading — “Spring in the Balkans”

International Student, Diana Decheva

5. Short Story Reading — “Lamia’s Feast”

Third-year Class B, Sonoko Koga

6. Short Story Reading — “Castration of the Sky Father”

Second-year Class C, Shiyo Takaoka

7. Short Story Reading — “Murmurs of the Dead”

Greetings, everyone. I would like to thank you all for gathering here on this stormy night.

This is the St. Mary’s Academy for Girls Literature Club’s last regular meeting of the semester. As president of our club, I, Sayuri Sumikawa, would like to begin with some opening remarks. Please feel free to sip on the welcome drinks I’ve just handed out as you listen.

Our club is small, with less than ten members to its name, but it looks like everyone is present tonight. While it may be too dark to make out your faces, I can still see that each chair is filled.

Despite the circumstances, thank you all for coming.

If this is your first time at the mystery stew, some of you may be confused as to why the literary salon is so dark today. Or, perhaps, some of you have already heard bits and pieces about this from the older members and were excited to come here today. When it’s dark you can’t see what you usually can, and it almost feels like you are in another world.

We gather around this oval black marble table. Normally, the black crystal Baccarat chandelier would be shining above us, but today that light has been dimmed to its lowest setting. I will turn it off completely when our meeting begins. Then, the only light left will be this candle I hold in my hands.

Our literary salon is on the first floor of the annex, and is exclusive to us. It has lavender-colored carpets and wallpaper, and French windows decorated with flowing black velvet curtains. There is an antique cabinet with clawed feet, and a Gobelins-woven sofa. This annex is a remodeled Gothic-style convent that was originally connected to the main school building, so our sophisticated décor matches perfectly. Who was it that jumped for joy, saying that the salon was “just like an Anna Sui boutique” when she was first invited here?

Ah, but our salon doesn’t just look elegant; we also have an entire wall filled with shelves of the most exceptional books. Since this is an all-girls missionary school, the academic library has countless books on Catholicism and scholastic topics. So we have deliberately collected books and documents from various genres that you wouldn’t typically find elsewhere at school. Kind of like a small private library. But this library alone is a great asset to our club.

Then there are the sound-proof walls and windows that silence the commotion from the courtyard and allow our members to immerse themselves in their reading and writing activities in peace. We read and discuss books together, research authors and make presentations about them, read our original stories aloud to one another, chat about literature in general, and conduct all other literary activities imaginable without interruption.

We owe the creation of this unbelievably perfect salon completely thanks to the father of our former club president, Itsumi Shiraishi. Two years before the convent was remodeled and annexed into the school—and right after Itsumi entered high school—Mr. Shiraishi made a generous donation and built this salon. It’s in a lovely southeast corner on the first floor and has the best access to sunlight. Of course, you all know that Mr. Shiraishi is the school chairman, right?

To me, this salon is irreplaceable. I’m sure that you all feel the same way. You feel calmer here than in any of the classrooms. This is where you can concentrate on books that you can’t read at home, where you finish the stories that you’re stuck on. In the cold seasons, we sprawl out on the sofa in front of the fireplace, nursing hot chocolate and critiquing each other’s stories, and in the summer, we quench our thirst with homemade lemonade while debating literary theories. Yes, this is surely our private castle in the sky.

The salon has a different feel with the lights dimmed this low. Isn’t it grand? Against the candle’s soft flame, only the chandelier, the set of wall lights, and your silhouettes stand out, granting this room a mystical and solemn ambience.

Normally, there would be a Wedgwood tea set, freshly baked scones, and sweet-smelling jams resting on this table. But, tonight, all of those things have been put away. Did you notice something on the marble table that doesn’t quite fit in?

That’s right. A pot. A shiny, amber-colored, copper pot. It’s from Mauviel, the French brand, you know.

We have a first-year student and an international student with us today, so I’d like to give a more detailed explanation about the proceedings. Tonight, we are having a so-called “mystery stew.” Indeed, as you might have expected, we will put strange things into a pot and then eat them in total darkness. Many girls—especially the girls at our school—may not be familiar with this kind of thing. Nevertheless, it is a Literature Club tradition to meet around the mystery stew, once every term, before vacation.

What?

How did these mystery stew meetings start?

Well…Our club has a long history, so there are numerous theories as to the stew’s origin. One is that some club members tried it for fun and it just kind of stuck, and another is that the members were tired of only eating luxury foods and were curious to try something grotesque—but the one that has me most convinced, the one that I believe, is that they did it to sharpen their senses.

Don’t you feel your five senses growing stronger in the dark?

Take away the everyday light that surrounds you, try resuming your normal activities, and you’ll find that even the most ordinary of movements feel unusual. Do not rely on sight alone—an extremely important concept for aspiring literati, don’t you think? That’s why I like this theory best.

Take the cocktail you are drinking right now, for example. Don’t you feel strange drinking it in the dark? Is the cocktail red or is it blue? Is there something floating in it? Is it sweet or is it bitter? Is it thick or is it smooth? It takes a lot of courage to put something in your mouth when you don’t know what it is, doesn’t it? Ah, but do not fret. The rules say that our cocktails must only contain ingredients fit for drinking. I mean, this is a meeting just for girls, after all; we want something tasty to drink. But if this were the pot with the mystery items in it…wouldn’t you be terrified to bring it to your mouth?

How will your sense of smell, taste, sound, and touch react when you’ve lost your sense of sight? Refine, betray, and release your five senses. This is what I understand to be the goal of our meeting tonight.

Now I will explain the rules of the mystery stew.

First of all, everyone has brought an item of their choice, correct? Usually the rules only allow for edible things, but we will also be accepting inedible items tonight. Hehe. This is what makes our mystery stew unique. But unsanitary items, like shoes or bugs, are strictly forbidden. Everyone should remember this is a girls’ meeting, after all.

All mystery stews have similar rules, but the most ironclad one is the “no spoilers” rule. You have put your items in an opaque container, and into the refrigerator in the kitchen, correct? I, the “pot bearer,” am the only one who can add things to the mystery stew. Let us dine on whatever comes out of the pot with our hearts racing in anticipation.

On to the next rule. You must finish your plate before taking your next serving. It is everyone’s responsibility to eat until the pot has been totally emptied.

Which mystery stew was it…the one with the terrible strawberry rice cake that really taught us a lesson? It was unbearably sweet from beginning to end. The moment the rice cake was thrown into the pot, the red bean paste inside became gooey and melted into the soup, and it was impossible to take out. Perhaps someone has brought another strawberry rice cake today. Well, no matter. The rule is that anything goes, after all.

Speaking of anything goes, do you remember the time there was a Chanel watch in the stew? Since it was dark, the member who had found it could only tell that it was a watch at first, and she complained that she barely got to eat anything because she couldn’t clear her plate. Then, after we finished off the stew and had some noodles and hot porridge and turned on the lights, we found that it was a Chanel watch, and a limited-edition model at that. Everyone made quite a fuss over it. The girl who they’d laughed at and pitied instantly became the object of everyone’s envy. The watch had suffered some heat damage, even though it was waterproof, and apparently cost a lot to fix. But still, that’s not a model you come by every day. I’d say she got it for pretty cheap if all she had to pay were the repair fees.

Who was the lucky girl? Ahh, yes, that’s right. That was also Itsumi. She was ecstatic…

I’m sorry. I didn’t realize that I was talking about her again. I didn’t mean to make you sad. I am truly sorry.

Well, the next rule is—oh dear, newcomers, please don’t look so afraid. There will be times when the stew tastes awful, of course, but I have properly prepared desserts to cleanse your palates at the end. Tasty drinks and desserts are a must for a girls’ night, right?

It is customary for the club president to make desserts for the meeting. I spent all morning baking as best as I could. Last year we had crème brûlée, honey flan, strawberry Bavarian cream, and this time we will have—well, please save your excitement for the end.

The strawberry rice cake may have been a failure, but the melon-flavored snow cone syrup was also a disaster. The broth got all muddy and smelled like boiled-down perfume, and then, when we turned on the lights, we saw that it had turned our tongues green…Oh, what a horrible taste and smell it had! I shudder at the mere thought of it. I wonder if someone has brought syrup again today. I feel anxious about this at every meeting.

Oh right, there is one more rule: even after the meeting ends, you can’t tell anyone which item you’ve brought, and you can’t pry and ask others about theirs. If we don’t do it this way, we would discover a pattern and it wouldn’t be fun.

Some members have also brought wonderful things for the stew. We were most fond of the bird’s nest stew. It was packed with minerals and good for your skin and felt pleasant on the tongue. The kind of thing girls tend to go crazy for. It was probably the best ingredient in mystery stew history. Everyone also loved the shark fin because it has collagen in it. Oh, I’d be delighted if someone brought us a good beauty product this year.

By the way…

You all haven’t forgotten to bring one other important item, right?

Yes. The short stories.

This may be a “mystery stew meeting,” but your short stories are the true main attraction for the night. Every meeting, we take turns reading our stories aloud while the other members listen and dine on the stew. You all wrote your short stories, correct?

Stories you only hear in the dark. Stories that you feel when you lose your sense of sight and your five senses betray you—isn’t this the perfect setting? This is the real thrill of our meetings. I think this is really why these meetings have gone on for such a long time.

Normally, you can choose your own topic. However, after that tragic incident, I decided to pick your topic for you, just this once. You may have struggled to write about it in such a limited amount of time, but I’d like you to think of it as an important lesson in writing.

That’s right. The topic is the death of former club president Itsumi Shiraishi.

Since elementary school, Itsumi was my best friend. We spent every day together. I still can’t believe that she’s gone.

Everyone always told us that we were complete opposites. Itsumi was a go-getter, someone who couldn’t rest until she’d settled everything in black-and-white. But I was more the type who lived a quiet life, sheltered in her shadow. I’ve been sickly since birth.

Don’t you find that friendships between girls our age exist within two extremes? If a girl is similar to you, you’ll either hate her or love her; if she’s your opposite, you will either love her or hate her. There’s no middle ground. I imagine you learn how to gracefully handle these kinds of things as you become an adult: you learn that whether you are similar or different, get along or don’t, these relationships provide us with the wisdom we need to survive in society.

But for our generation, this wisdom is impossible. All we care about are our own selfish emotions. We have to protect our feelings more than anything else. So, do we kill, or allow ourselves to be killed? Friendships between girls are always hanging in this balance. Life-or-death survival. This is especially true at an all-girls school like ours. Right, ladies?

Itsumi was the best partner for me in that way. She compensated for all of my weaknesses. We could coexist without killing each other. She signed up to volunteer with me when I said I was nervous doing it alone, pushed me to study abroad when I felt hesitant about it, and practiced debate with me when I told her I wasn’t very good at it. And, in turn, I am proud to say that I was the best partner for her too. Itsumi was bad with details—so I planned club events, looked at hotels and made reservations for her, and did research on the colleges she wanted to go to. Yes, we two were truly one. She often told me that she didn’t know what she would do without me, and I felt the same way about her. There are a lot of things I would’ve never experienced without her.

I think it was our advisor, Mr. Hojo, who had told us that we were like “the sun and the moon.” I was initially appalled that a Japanese language teacher like him would use such an awful cliché, but, after losing Itsumi, I realized he was right. Itsumi was my sun. I cannot shine without her. She was the reason for my existence.

So, when I lost Itsumi, it felt like half of my body had been ripped away from me, and I can’t find my balance even when I walk. It’s like this every day.

Why did Itsumi die?

I still don’t know why.

It’s only been one week since her death. I really can’t believe it. You’re all as devastated as I am, right? It’s only natural to feel this way. To think that someone as happy as Itsumi would die like that…

—I’m sorry for crying.

What?

Yes, of course, I’m aware. I know there’s a rumor going around that someone in our club killed Itsumi. Do I believe it, you ask? Hmm, well…

Was it a suicide or murder? We don’t even know that much.

It’s true. Itsumi’s death is shrouded in mystery. You all know that we weren’t allowed to attend her funeral and that none of her family would tell us what happened, right? Itsumi’s father, mother, and younger brother Kazuki wouldn’t say a thing.

I still have dreams about it. I see Itsumi lying face-down, covered in blood—

You were all there to see the body. Why did she die on school grounds? Why had she fallen into a flowerbed on the lower terrace? And why was she holding that when she died? What was she trying to tell us?

This is all I’ve been thinking about every day for the past week.

Which is why I’d like to commemorate her tonight. In her beloved salon, with all the Literature Club members in attendance.

I may be your host for the night, but the true star of the show is none other than our dearly departed friend, Itsumi Shiraishi.

I honestly considered cancelling tonight’s meeting until I remembered what a pivotal role our club played in her high school career. You could even say that this is where she spent all of her adolescence. She used to come here every day after school to read and passionately discuss various works in her earnest attempt to become a writer and literary critic. Her father was so taken by her passion that he gave her this salon. I thought it would be much better for us to mourn together as a club rather than separately and alone. It’s a very Literature Club way to show our respects…don’t you think? You all came here because you agree with me and don’t think this is improper, right?

I think Itsumi is happy about this. I would know.

But, no matter what it takes, I need to find out what was going on.

What on earth happened?

I asked you all to write about this incident, from your own point of views, so that we can find the answer.

Short stories about Itsumi’s death. Short stories dedicated to Itsumi. I wanted you to remember everything you can about that unfortunate incident and write it down, and then read it aloud to everyone in our club. We are bound to learn the truth about her death, which has sublimated into your writing. Why did Itsumi have to die? And—did one of you really murder her?

What terrible thunder. The sound of the rain is growing louder. And yet, isn’t a summer storm fitting for the evening?

Well then, it’s about time to begin.

I am going to turn off the chandelier. Is everyone ready?

Once the lights are out, I will only rely on candlelight to guide me as I start to add things to the stew. Then, I will have you take turns reading aloud. I’ve created a space next to the sofa and arranged a candlestick near the fireplace. Please read your stories in that space.

Now, let the St. Mary’s Academy for Girls Literature Club’s 61st Meeting and Mystery Stew Reading begin.

I can’t forget what it looked like.

A beautiful girl, covered in blood, being carried away on a stretcher. In her porcelain hand, she clutches a posy of white lily-of-the-valleys.

Even though someone has died, that death was fantastically beautiful, almost uncomfortably so, and mesmerized all those who witnessed it.

I will not forget her death for as long as I live.

I met that girl—Itsumi Shiraishi—soon after enrolling at this academy.

Since I was a child, I had always felt I had no place to go.

Whether I was at home, in school, on the route that connects those two places, or even at the convenience store that my classmates often visited, I couldn’t shake this feeling of alienation. My four family members and I live in a small, two-bedroom home where I can’t even have a room of my own, which, in the literal sense of the words, has left me with “no place to go.” I share one of the bedrooms with my little sister, who is in middle school. My two little brothers, who are in elementary school, share the other bedroom. Our mother sleeps on a pullout sofa in the corner of our eight-mat living room.

I’m not sure why my mother ended up raising the four of us by herself. Every time I come back to our cramped, 600-square-foot home, I let out a sigh and wonder why my parents couldn’t have just each taken two of us when they got divorced. Maybe my father didn’t want custody. Or maybe my mother couldn’t bear to let any of us go. My parents won’t tell us what happened, even though I think it would be better if they did. Despite the fact that my father won’t talk about the divorce, he has no problem boasting about the twenty-five thousand yen he pays for each of us every month in child support whenever we see him.

“In other words, every month a hundred thousand yen just vanishes from my paycheck,” my father always says, whenever my siblings and I are sitting in a diner booth with him, leaving us to awkwardly poke at our chocolate parfaits. It’s like his catchphrase. He’s bragging when he says this; he doesn’t sound patronizing or disappointed. He seems to genuinely enjoy our infrequent meetings and—on days where he wins his bets on horse races—he will even take us to a high-class Chinese or barbecue restaurant instead of the usual diner. On those occasions, he won’t balk even slightly at my little brothers’ healthy appetites.

My mother has never said, “We don’t get enough child support,” or “It’d be nice if he offered to pay more,” or anything like that in front of us. She just goes through the daily motions of working her part-time job and taking care of us. On her days off she does sporadic jobs and works from home.

Just because my parents aren’t in a divorce war doesn’t mean that our lives are easy. To be frank, my family is very poor. My father is a taxi driver, and my mother is a cashier at a supermarket, who hems and repurposes clothing on the side. Despite our financial struggles, I was able to enroll at the famous missionary school St. Mary’s Academy for Girls, thanks to their scholarship program. The scholarship guidelines are as follows:

Our academy will endow one student at the Elementary, Middle, and High school levels, who is of high educational merit and has passed the academy’s entrance exam, and whose household demonstrates financial need, with the necessary funds for academic courses, transportation, textbooks, and expenses for extracurricular and other school activities. Scholarships do not have to be repaid.

I have adored this academy since I was young. On the train, I’d catch glimpses of the lovely, prim uniforms of the schoolgirls. The school had a noble and dignified spirit built on Christian principles. And most of all, I liked the shining faces of the students who went there.

I was enamored with the idea of studying at the academy. If I could just pass the entrance exam and become the scholarship student, I would be able to go to the academy—this was my only goal. I started studying my hardest in my later years of elementary school. Since my parents couldn’t afford private teachers or cram school, I only asked that they buy me textbooks, and I solved every problem in my textbooks over and over, as if painting them in ink.

I can’t tell you how thrilled I was when I received the notice that I had passed the St. Mary’s Academy for Girls’ entrance exam and the scholarship acceptance letter in the same envelope in the mail. I had been expecting this. I had never given up hope. But, I still couldn’t believe that I got to be the one and only scholarship student!

In the days before the entrance ceremony, I was measured for my uniform, picked up my shoes for school, and visited the campus for orientation. The first time I stepped onto the school grounds my heart raced so fast that it hurt. Now I looked forward to becoming like the graceful upperclassmen in uniform I had seen.

However.

Two weeks after classes started, I realized I didn’t belong here, after all.

Certainly, I made friends. There were girls I had lunch with. Yet I was still haunted by the feeling that I didn’t fit in. Even during the before and after-school prayers, I was the only one out of place.

At first, I thought I was just self-conscious because I was the only student who needed scholarship funds, or that I was jealous of my classmates who didn’t have financial burdens like me. But after I started my part-time job, I realized it wasn’t either of those.

Though the academy strictly forbids part-time jobs, I worked as a cashier in the same supermarket as my mother. But I didn’t hit it off with anyone my age and ended up working in silence. When I’d first started my job, some other girls at the supermarket had come to talk to me during the lunch break. When they first heard I was a student at St. Mary’s Academy for Girls they acted impressed, but the next day they started keeping their distance from me.

“Why would a girl from St. Mary’s Academy for Girls work part-time at a supermarket?”

“Her mother works here, too.”

“What?! She’s not rich. So she’s lying about the school?”

“But she was wearing their uniform the other day.”

“For real? I don’t believe it.”

I overheard these conversations coming from the locker room. No matter where I go, I’m never quite enough, I thought.

Until I met Itsumi Shiraishi.

I often still think about the first time I met her.

I was getting better at pretending I fit in, but unable to genuinely enjoy my new life at the academy. In between periods, I often went to the terrace on the roof of the third floor of the school to peer down at the campus from over the fence.

No one was ever there. It was a quiet place. Apparently, the terrace was really popular with students until the sunroom was built in Building 1 and became the new hang-out spot. It’s only natural that the sunroom, with a glass ceiling that blocks UV rays and harsh weather, would be more popular.

On the terrace, I would always gaze at the small church on the side of the schoolyard. It’s an old wooden church with a cross on top of its triangular roof. We call the big cathedral, the one that fits the entire student body, the “new church,” and the one I would always look at the “old church.” Before class and before homeroom was dismissed in the afternoon, we would always say “The Lord’s Prayer,” and then we’d go to the old church for our religion classes, where we recited hymns and listened to the Sisters’ stories. The only things in the old church are some rough-looking wooden benches, an out-of-tune organ, and a crucifix with peeling paint hanging on the altar.

Every time I went to the old church, I felt oddly at peace. This academy was originally founded by English nuns who came to Japan after the war, on a mission to provide girls with an education based on Christian ideas and principles. Our school is integrated from elementary school to junior college, and, although it was built long ago, the architecture of the buildings and annex are so distinctive that you would never think you were in Japan. The new church, only built ten years ago, has a stunning statue of the Virgin Mary and large stained-glass windows crafted by Christian artists behind the altar. It really casts an air of splendor and gravity over the entire campus. So the old church is the only building that doesn’t have any flashy decorations, and its plain appearance reminded me of myself in a way.

I would sit on the terrace floor and occasionally look over at the old church while reading a collection of poems by Ezra Pound. This was my favorite way to pass the time between periods.

One day, a voice suddenly said, “You’re always here.”

I lifted my head to find Itsumi Shiraishi staring at me.

“You like books? You sure read a lot.”

“Yes, well…” I trailed off. I couldn’t believe Itsumi Shiraishi was talking to me!

I had heard all about her when I first entered the academy. This is a tiny all-girls school, with only three classes per grade, where underclassmen idolize stunning and exceptional upperclassmen like Itsumi. Plus, her father is also the chairman of our academy, which made her far wealthier than any of the other girls in school. Her father was the one who created the Shiraishi Memorial Scholarship, which, in other words, meant that it is all thanks to him that I can even attend this academy.

But whether or not you were a scholarship student, there wasn’t one person at school who didn’t know Itsumi Shiraishi. All of the girls in elementary, junior high, and high school admired her remarkable beauty and intelligence and looked up to her as a role model, watching every move she made.

For the first time, I looked at her up close, fascinated and hypnotized.

“I’m the president of the Literature Club. You should come check out our salon if you like books so much,” she suggested.

I already knew about the Literature Club, of course. Everyone wanted to be a member. It had a special salon tucked away in its own separate building. The more rumors students heard about it, the more they were fascinated. It was every schoolgirl’s dream to drink black tea in that salon, even if just once.

Just because it’s called the Literature Club doesn’t mean that just anyone who likes books could join. You couldn’t become a member without an invitation from Itsumi. On the other hand, even if you weren’t interested in literature or couldn’t read, write, or critique particularly well, you could still become a member with Itsumi’s invitation. This meant that the five current members of the club had been specifically chosen by Itsumi, and consequently they were revered by everyone in school. It’s one of those clubs that gives you a special social status just by being in it.

“Are you sure it’s all right for me to visit?” I asked nervously.

“Of course. Why wouldn’t it be?” Itsumi replied.

“It’s just…” I hesitated for a moment, but answered honestly. “Well, I heard that only special people can visit the salon.”

Itsumi let loose a huge laugh. She was different from what I had imagined: She was unguarded, in a good way, and brimming with friendliness.

“No, really anyone is welcome. Rumors go around the school and no one knocks on our door. That’s all it is. Come on, let’s go to the salon.”

“No, I…”

“You don’t have to be so shy. You’re Mirei Nitani, right?”

Astonished, I looked at Itsumi. Even if I knew who she was, I never thought she would know about an underclassman, and what’s more, an utterly ordinary one like me. She smiled brightly, as if sensing my disbelief.

“You are this year’s scholarship student, right? Everyone’s got their eye on you,” she remarked.

Was that true?

I was mortified at the thought that everyone knew I was the scholarship student. I felt like my family’s financial situation had been exposed; I was embarrassed. I had never confided in my classmates about it or heard the professors talk about me with the other students. But I guess it would only make sense for rumors to spread in a small, all-girls school like this. I suddenly felt ashamed for trying to act like I fit in when all along everyone actually knew I didn’t.

“All right, why don’t we just stop by for a visit? You can decide if you want to join our club later. We have a collection of books I’m very proud of, you know.”

“What kind books do you have?” I inquired. My interest was piqued.

“Well…Hmm, our books by T.S. Eliot and William Yeats might interest you. We also have Ezra Pound, of course.”

She had books I wanted to read. I knew they were the expensive, hardcover editions I’d never be able to afford.

With that, I accepted her invitation and we went to visit the salon.

How can I describe how impressed I was when I first stepped into the salon? The dark, sparkling chandelier hanging from the high ceiling. The fluffy carpet. The imported, antique sofa. The luxury tableware from Ginori and Wedgwood lining the cabinets. The brick fireplace. And to top it all off, a library that stretched across the entire wall. There was a huge collection of foreign books, which looked like fine art along that wall.

My head was still reeling when Itsumi took a book from the shelf.

“Hugh Selwyn Mauberley by Ezra Pound. A rare book, and it’s even been autographed. Take a look!”

I took the brown volume in my hands, amazed. I had heard rumors about this book before. It was a rare book published in 1920, an antique that would go for millions if sold today. I couldn’t believe that I was holding it now. My fingers shook as I opened the cover to find Ezra Pound’s scribbled signature on the left side of the title page.

“This is amazing. How did you get this?”

“I got it through one of my father’s connections. There are a lot of uncommon books in our salon. Please read anything you like.”

I carefully scanned the shelves, thinking how lucky I was to have come to the salon.

“Why don’t we take a break from the library and have some tea?” Someone spoke, and a schoolgirl came in from the back of the room carrying a tray.

“A newcomer, I see,” she said. “I’m Sayuri Sumikawa, vice president of the Literature Club. It’s a pleasure to meet you.”

Sayuri bowed to me as she placed a tray of teacups and cake onto the table. I had also heard about Sayuri when I first entered the academy. She had been Itsumi’s best friend since elementary school. Itsumi was stunning, but Sayuri was attractive in a different way. She had long, sleek black hair and white, soft-looking skin. She never wore makeup, not even lip balm, and her only accessory was the cross that hung around her neck. Nevertheless, she was as lovely and graceful as the morning mist.

When Itsumi and Sayuri were together, the air that surrounded them was unlike anything else. It felt like they were the living, breathing stars of the red carpet. Yes, that was exactly how it felt.

“Itsumi, isn’t this the scholarship student?” Sayuri asked.

“Yes. She really seems to like books, so I thought I’d invite her over.”

“I know there’s a reading and essay section on that scholarship exam. You must be pretty clever to have passed it. Please do join our club. I look forward to it.” Sayuri smiled gently as she offered me a strawberry tart. Its color reminded me of spring. I bit into it.

“This is delicious!” I automatically sighed with delight. “Did you make this, Sayuri?”

“I wish I could say I did, but I can’t. One of our members is an expert at baking. Sweets are her specialty. I’ll introduce you. Akane, come to the living room,” Sayuri called out. I was so captivated by the interior design and the library that I didn’t even realize there was a kitchen.

“I just finished baking these madeleines. Would you like to try one?” A girl in a frilly white apron and pink gloves carried a tray of baked goods into the room. She had curly hair that hung down to her waist and a face that was as adorable as a child’s. I suddenly got the sense that I was the only one who didn’t fit in here and became uneasy.

“This is Akane Kominami. She’s in her second year at the academy. She loves the kitchen so much that she experiments with recipes more than she actually reads,” Itsumi teased, with an unreadable smile.

“Hey, I do the readings. Come on, Itsumi, cut it out,” Akane pouted, puffing out her adorable cheeks in irritation.

Just then, the door swung open and three more girls entered the room.

“Wow, that smells great!” one exclaimed.

“What sweets did you make today?” another one asked, wiggling her nose. They skipped any sort of self-introduction.

“Ladies, please. You’re being rude in front of our new member,” Sayuri scolded, though she smiled. The three girls seemed to finally notice that I was there, and stuck their tongues out slightly, looking at each other like mischievous children who had gotten in trouble.

“My name is Shiyo Takaoka, I’m in my second year. I was the first member to join the club after Itsumi and Sayuri reopened it, and I’m proud of it! I’m currently working as an author.” This was spoken by an attractive and dignified girl with a sporty-looking ponytail.

“I’m Sonoko Koga, and I’m in my third and final year of high school. Itsumi and Sayuri are my classmates. It’s nice to meet you,” said a steady, rational-looking girl whose narrow eyes shone from behind pointed glasses.

“I’m Diana Decheva, the international student. I’m from Bulgaria,” said the last girl, a mystical fairy from Europe with deeply chiseled facial features.

Each member was attractive and elegant in her own unique way. Why am I the only one who…I started feeling self-conscious and miserable, as if I were wilting away, but I did my best to suppress these feelings.

“Well, now that everyone’s here, why don’t we have some tea?” proposed Sayuri, setting up the Royal Copenhagen tea set. Akane stood beside her and put madeleines onto each of our plates.

It was like a dream. I couldn’t believe that an ordinary girl like me had been invited to the salon that everyone in the school idolized, and that I was drinking tea with the stunning members of the Literature Club. They laughed and chatted while I ate my madeleine in silence, feeling unable to join their conversation.

“Mirei, what kind of books do you like?” Sonoko Koga asked me.

“Umm, right now I’m trying to read Beckett.”

“Wow, you have good taste. That kind of thing is way too difficult for me.”

“What do you like to read, Sonoko?”

“Well, scientific things. I read medical books, but I’m not really picky about authors or anything like that,” Sonoko answered, smiling, combing her silky bob haircut with her fingers. A lovely fragrance danced out from her soft neck.

“Ooh…What kind of that perfume is that?” I asked.

“This? Oh, it’s Muguet from Guerlain,” Sonoko answered.

“My goodness,” Itsumi interjected. “Sonoko, you’ve already got this year’s Muguet? It hasn’t even come out yet.”

“Oh, I had it specially ordered from France.”

I had never heard of that perfume before, but it’s apparently one of those exclusive, limited-time-only perfumes sold at a few shops every spring. It was an entrancing, unforgettable smell.

“Well then, I guess that means this fragrance is all yours for the time being,” Itsumi remarked playfully.

Even their conversation sounded elegant to me.

“I ate too many tarts. Oh, I’m stuffed. You can eat mine if you like,” offered Itsumi, casually handing me her madeleines. I had already finished my portion, and I’m sure I looked like I wanted more. Although I was embarrassed, I reached for them without hesitation. They were so much more delicious than anything you could find in a store.

The madeleines were the perfect amount of sweet and filled the air with the lovely scent of rum. It felt like I was getting tipsy. Actually, I think I really was. I was drunk off the gorgeous salon, the splendid club president and vice president, the amazing and exceptional members of the club, and their sparkling conversation.

Perhaps it had been something I ate, or perhaps I had just been overwhelmed by the salon’s radiance…I’m not sure why, but I threw up everything I’d eaten when I returned home that night.

At the salon, I’d genuinely laughed for the first time since entering the academy. It wasn’t my family members or classmates or teachers, but Itsumi who had finally given me a place to belong.

Being in the club was fun.

On Mondays, we had book discussions, when we would all read one novel and talk about it together. On Tuesdays, we had debates. That might sound stuffy, but it was really just a carefree chat session about anything related to literature. The salon was closed for “library organizational purposes” on Wednesdays, the one day that we wouldn’t meet. Thursdays and Fridays were our “free activity” days. We could write if we were so inclined, or dive into any of the books on the shelves. Participation was generally voluntary, but the attendance rate was high. I’m sure that the desserts from our pastry chef, Akane Kominami, must have had something to do with this.

However, a high school student like me can only make money after school. So only one week after I had become a member of the prestigious Literature Club, I found I was almost never able to make it to the meetings.

“You’ve just become a member, but you don’t come to the salon very often. Have you been busy?” Itsumi asked me when we passed each other in the hallway one day.

“No, umm…Actually, I have a part-time job,” I replied honestly.

“A part-time job?” Itsumi frowned.

The academy strictly forbids part-time jobs. This rule also applies to scholarship students; the scholarship fund system was created so that students can focus on their studies. However, even though my family wasn’t spending money on my education, they were still barely scraping by. If I didn’t have some sort of income, they couldn’t make ends meet.

I knew that Mr. Shiraishi might revoke my scholarship funds if Itsumi found out about my part-time job, but I didn’t want to lie to an upperclassman as lovely and honest as she was.

“What kind of job do you do?”

“I’m a cashier at a supermarket. I work with my mother.”

“Oh, I see…” Itsumi narrowed her eyes and thought for a while.

“Hey, I don’t want to make things awkward by asking,” she started to say. “But I think I might know of something more suitable for you. I’m not saying that being a supermarket cashier is bad or anything. You’ve just got to put the right people in the right place. And I’m just saying that your intelligence shouldn’t go to waste. What if you tried using that?”

“Use that?”

“Well, we’ve been looking for a private tutor for my little brother. He’s in fourth grade right now, but he’s not very good at math or Japanese. You do well in both of those subjects, right?”

“But I’m just a…”

“If you tutored my brother, the school wouldn’t have any problems with it and I’m sure it would make my father happy, too. That way you won’t have to work in secret anymore,” Itsumi said with a soft smile.

I was elated. She’d understood what I was going through and had immediately come up with a way to avoid problems with the scholarship program, the academy, and my family. Her thoughtfulness meant more to me than anything.

“I’d be delighted to. Thank you for this opportunity.”

Since then, my respect and adoration for Itsumi only kept growing.

Itsumi’s house, no, her mansion, is in the upscale area in the hilly part of town.

I sat in the backseat of the Shiraishi family’s black car, gazing at the lush, green foliage as we went up the gently sloping hill. The driver looked to be over sixty years old and was white down to his eyebrows. He wore a navy-blue suit and white gloves and spoke to me with great courtesy.

“Shall I turn off the air conditioning, Miss Mirei?”

“Do you feel carsick, Miss Mirei?”

“How is Miss Itsumi doing in school, Miss Mirei?”

I had never been called “miss” before in my life. I could only manage to answer in a quiet and trembling voice, feeling somewhat embarrassed.

“Mr. Muro,” Itsumi called to the driver, “Mirei is going to be Kazuki’s private teacher from now on.”

“Wonderful. I am sure Master Kazuki will be happy to have another lady in the house.”

My eyes met with Mr. Muro’s in the rear-view mirror. Just from the look in his eyes, I could tell that he was a quiet man who loved the Shiraishi family and had worked for them for many years. I remember thinking how happy they all seemed.

The rumors were true: Itsumi’s mansion really did have a pool. Not only that, but there was also a pond with koi fish, a small waterfall, majestic stone lanterns, and an old, worn-out building that looked like a tea house, separate from the mansion. The place was huge, like one of the chic European-style homes that had been built before the war.

Itsumi’s family was even more fascinating than any of their possessions. Her mother was courteous and graceful. Her father’s gaze was so piercing it felt like he could see straight through to your soul, and I found out that he also runs a general hospital and major construction company on top of the academy. (I think Itsumi got her elegance from her mother and her quick-wittedness from her father). Her little brother spoke politely and had impeccable manners for a boy in elementary school, yet was also quite playful and mischievous. No matter what they did or said, the Shiraishi family emanated elegance. Even a young, sixteen-year-old girl like me knew that this was what real “high-class” looked like; I was deeply impressed.

That night, I tutored Kazuki in math and Japanese for an hour each, and then the Shiraishi family fed me dinner. I received an envelope when I was about to go home. I got in the car and peeked in it—and was startled to find a ten thousand yen* note inside. Is this my monthly salary? I wondered. This can’t be for the two hours I tutored today. It’s rare for even professionals to get five thousand yen an hour.

When I asked Itsumi about it the next day at school, she told me that it was, in fact, my pay for just that day.

“It’s too much. I can’t accept it.” I tried to give the bill back to her, but she refused to take it.

“It’s fine. I mean, that’s what we paid our last tutor.”

“But I’m not a professional or some student from a famous college or anything like that. I’m just an ordinary high school student. Besides, I’m younger than you. I’d be happy to work for you for just one thousand yen an hour.”

We went back and forth on the issue until Itsumi finally relented.

From then on, I worked as the Shiraishi family’s private tutor.

Itsumi’s mother was very generous and would sometimes give me gifts. She’d say “Please decorate your home with this” when presenting me with an exquisite Limoges mantle clock, or “Please use this with your mother” when giving me a lace-knit coaster, and “I bought this twice” when handing me a Kiriko glass. I was embarrassed to bring such luxury items into a house where they stuck out like a sore thumb and frankly caused more trouble than they were worth, but my siblings were delighted the day I brought them home some Godiva chocolate.

“Oh, we’re so grateful for these fancy things. Wow, you’ve really made your way up in the world, haven’t you,” my mother remarked sarcastically as she picked at the chocolates with us. She wasn’t happy that I had quit my job at the supermarket.

“We would make even more money if you picked up a shift at the supermarket when you’re not tutoring, you know,” she groaned, nevertheless throwing truffles into her mouth.

“I can’t. I’m not even supposed to have a part-time job. I quit being a cashier to be a tutor. They might expel me if I break the rules again,” I tried to explain.

“Just lie if they catch you.”

“So you wouldn’t care if they took my scholarship money away?”

“I didn’t want to send you to a private school in the first place. So what if you do get expelled?” she retorted, wiping smeared chocolate off of my brother’s mouth. “Besides, tutors don’t usually work every day. Why do you come home so late all the time?”

“Well…because I joined a club.”

“A club?”

“Yeah. The school’s Literature Club.”

“Ahh, because you like books. Really goes well with your new fancy social status.”

“Don’t say things like that. If you hate our lifestyle so much, then maybe you shouldn’t have divorced Dad!” I flared up.

My mother went silent. I had never spoken to her like that before, let alone even mentioned the divorce. Going to an elite private school had gone to my head, and I had probably started to look down on her.

“Well look how brazen you’ve become, speaking to your mother like that,” she mumbled with a wry smile. She didn’t seem angry. “Yes…Having a place of your own.”

“…What?”

“I didn’t have a place of my own when I married your father. And I’m sure he was just as lost as I was.” My mother saw the surprised look on my face and suddenly became flustered. “Well, not in the physical sense, more in the way of emotional support—”

“I know how you feel,” I cut her off. This time it was my mother who looked surprised.

“I understand you, Mom,” I repeated. “I feel the same way.”

At my words, her face softened. We sat across from each other at the dinner table and drank our tea in silence. I guess I really am my mother’s daughter, after all, I thought.

If divorce had given my mother a place of her own, the Literature Club and its salon were the same for me. I wanted to thank Itsumi for giving me somewhere to belong.

“Um, I’d like to do something to repay you,” I once said to Itsumi. I didn’t just want Itsumi, but her whole family, to feel my gratitude for everything they had done for me.

“If you want to give back, you shouldn’t give to us, but to those less fortunate,” Itsumi suggested instead, grinning.

Soon after, I resumed the volunteer activities that I had given up on in junior high. Using wanted ads I found on the internet, I volunteered to talk with senior citizens who lived alone and to people who’d moved from the countryside who had no friends in the area. As someone who had searched for her own place to belong, I wanted to help those people because I used to be just like them. Of course, it takes courage to meet up with a total stranger, but I felt brave enough to do it because I knew I could distract them from their loneliness. I may not have been the most outgoing volunteer, but I do think I was good at it. I could understand their pain because I know the bitter tang of loneliness.

When I was in junior high, I was busy studying for exams and only volunteered when it was convenient. But now I was ready to follow in Itsumi’s footsteps and volunteered with a renewed sense of passion. I had always thought that volunteering was just about giving to others, but for the first time I had realized that you also get so much in return. I finally saw that it was also essential for my own personal growth.

The Shiraishi family’s generosity helped open my mind. I idolized them. I remember thinking that, if I were to get married and have children someday, I wanted to have a family that was just like theirs.

In my eyes, they were perfect. They had everything that my family could never have—good manners, compassion for one another, a refined upbringing—and they were everything that the ideal family was supposed to be.

I think jealousy arises when you have the conceited notion that you’re entitled to something that you’re not. But I never felt jealous when I saw Itsumi and her family. That’s how far superior their world was to mine.

Then, it became the time when the green of the earth began to shimmer under the new summer sun. Itsumi, who was normally lively and energetic, fell depressed. She usually played a pivotal role in our conversations in the club, but now she just sat there, half-listening.

As Itsumi grew weaker by the day, the club members began to worry. Sayuri made black tea with honey and ginger to perk her up, and Akane fed her some homemade quiche she had stuffed with vegetables. Diana gave Itsumi a replenishing full-body massage with Bulgarian rose oil, Sonoko researched Itsumi’s condition in her medical books, and Shiyo tried to support her with encouraging speeches.

What had happened to Itsumi? I thought about asking her about it every time I went to their residence to tutor.

Then, one night—

I saw it by chance: their perfect family falling apart.

It was the last day of exams and school had ended early, so I’d gone to the Shiraishi residence a little earlier than I usually would have. I finished Kazuki’s lesson, left the room, and headed down the stairs. Just then, I heard a heated argument coming from Mr. Shiraishi’s library. “Shame on you!” a furious voice yelled. After hearing what I thought was a sharp slapping sound, Mr. Shiraishi burst out from the library, tugging a hysterical Itsumi by the arm. Her hair swung wildly as she sobbed, struggling in his grasp. I panicked and hid behind a pillar. Mr. Shiraishi’s eyes were bloodshot, his neatly combed hair tousled, his shirt collar in disarray. He dragged Itsumi out of the house and threw her into Mr. Muro’s car. Then, I watched the car drive off into the distance.

What on earth had happened to their happy, loving family?

I quietly put on my shoes, thinking it would be best to leave without saying goodbye, when someone suddenly emerged from the dark hallway.

“Ah!” I reflexively screamed. But the person just stood there staring blankly, unfazed by my scream.

“…Mrs. Shiraishi?”

It was Itsumi’s mother. “Oh, Mirei…”

Her pale face showed no trace of her usual cheerful expression.

“I just finished the lesson. I’ll be going home now,” I explained quickly.

“I see…” Her eyes were distant and unfocused. She had probably heard them fighting.

I felt frightened and sped out of the mansion.

After that, Itsumi didn’t come to school for a while. The teachers told us that she was in the hospital with pneumonia.

One week later, I had heard rumors that Itsumi was out of the hospital. I made my way to the salon to see her, but she wasn’t there. I hurried to the terrace, hoping I’d find her there. And there she was. She looked languid and ill as she leaned her body against a handrail.

“Itsumi,” I called out to her.

She turned to look at me, but she didn’t seem like her normal self. Her skin was pale, her eyelids were red and puffy, and her cheeks were sickly thin.

“Are you feeling better?”

“Yes, thank you for asking. My lungs have been weak since I was young,” she answered. It was painful watching her force a smile.

“Did something happen?”

“Something?”

“I mean, well, with your family…”

“Why do you ask?” she said, suddenly angry. I couldn’t bring myself to tell her that I had accidentally seen her argue with her father.

“No, it’s nothing. I was just wondering if anything was bothering you.”

“Bothering me…” Itsumi trailed off, looking up at the church. “Mirei…have you ever wanted to kill someone?”

I was startled. Everyone has dark thoughts at least once in their life, but I never thought Itsumi would say something like that. Unsure of how to respond, I stayed silent.

“I have. There’s someone I want to kill,” murmured Itsumi in a dark, hollow tone. I stared at her face in disbelief. I thought I had misheard her. The wind howled viciously.

“If I could kill her, I wouldn’t care if I died. That’s how much I hate her.”

“Itsumi…you don’t seem like yourself. What’s going on—”

The fight between Itsumi and her father replayed in my mind. I remembered Itsumi’s sobs as he took her away.

“My father,” Itsumi said in a detached tone, staring out into the distance, “is being seduced. Someone in the Literature Club is seducing him.”

“What?”

“I had noticed he’d been acting strange. So I searched around the library and found a school handkerchief on the floor. It wasn’t mine, of course.”

“That can’t be…”

“It smelled like lilies. Muguet by Guerlain—there’s only one person who uses that perfume, right?”

“I can’t believe it. That would mean…”

“It’s disgusting. We have science and math together. I thought we had a good-natured rivalry, and then she does something like that behind my back. With my father.” She bit hard on her lower lip. I had never seen her make that face before.

“Itsumi…” I didn’t know what to say.

She looked beyond me, her gaze so piercing it could kill. Terrified, I tried to say something, but couldn’t. Then, as if returning to sanity, she relaxed her shoulders and turned to me.

“Let’s go to the salon. I’ll make you some hot chocolate.” She smiled calmly. Then she took my hands in hers and stressed these next few words:

“Don’t tell anyone about this. This will be our little secret.”

When we arrived, everyone in the salon was talking about the sweets we would sell at the Easter & Pentecost Festival in June. The festival is a huge charity bazaar that celebrates Easter, which is in the spring, and Pentecost, which is celebrated fifty days after Easter, at the same time. Itsumi wasn’t saying anything, so Sayuri took her place and proceeded to talk about the festival arrangements with the members.

“We make cookie bunnies every year. We should do something different this time, something new. Does anyone have any ideas?”

“Um, what about cookies shaped like eggs? We can use icing to draw patterns on them,” Akane suggested.

“Ah, that’s great. It’ll be so cute. Ooh, I want to be in charge of drawing,” Shiyo called out, raising her hand.

“Okay, that’s what we’ll do for cookies this year. How many cakes should we bake?”

“We baked two hundred last year.”

“But we were immediately sold out.”

“All right, should we try for three hundred this time instead?”

During the entire conversation, Itsumi’s gaze didn’t waver. She stared directly at Sonoko Koga.

Did Sonoko really sleep with Itsumi’s father? I wondered.

“Well, why don’t we have three flavors, plain, green tea, and chocolate, and bake one hundred of each?” Sonoko suggested. She was acting completely normally in front of Itsumi. Didn’t she have any shame?

“Good idea. Let’s do it. Diana, do they celebrate Easter in Bulgaria?” Sayuri inquired.

“Yes. We make life-sized egg sculptures and paint them, and decorate the town square with them,” Diana answered.

“That’s interesting! I’d like to try my hand at that. I’ll ask the executive committee about it,” Sonoko replied. Itsumi still stared blankly at her.

“Umm, I have a question,” Akane chimed in, raising her hand. “I want to put some dainogen beans into the green tea pound cake.

What do you think?”

“Dainogen? A type of red bean, right?”

“Yeah. Beans from Hokkaido have thick skin, so I’d like to use beans from Tamba, if we can.”

“I’m sure that’ll taste great. What do you think, Itsumi? It wouldn’t be a problem if we just raised the price of the green tea cakes a little, right?” Sayuri addressed Itsumi, whose gaze didn’t even falter.

“Itsumi?” Sayuri called her name again.

Suddenly she snapped out of her trance and quickly threw on a smile. “Oh, right. That’s fine.”

After that, we all began to talk excitedly about what color our wrappings and ribbons should be, how much we should charge for our sweets, and other small details. Only Itsumi didn’t join in, just staring out the window with melancholy eyes.

It only makes sense that she was depressed. I would be in utter shock if I were in her shoes. It must’ve been painful for Itsumi to force a smile and see Sonoko every day. What’s worse was that Sonoko didn’t even seem to notice that Itsumi knew what she had done.

There were times when I thought about telling Sayuri and asking her for advice, but I didn’t. There are some things that best friends can’t tell each other because they’re so close. That must be why Itsumi wanted me to keep it a secret. I felt frustrated that I couldn’t say anything, but I decided to keep my mouth shut.

One day, Itsumi asked me to come to the salon after school.

She was there alone, sprawled out on the sofa next to the fireplace. She looked so relieved to see me, I was reminded of a lost child who had finally found her mother.

“Thank you for coming. Please sit down. I’ll make you some black tea. Actually, is chamomile okay? I need something that’ll help me relax.”

“Oh, sure.”

Itsumi disappeared into the kitchen for a moment, and then came back holding the Ginori tea set and tray. On the dessert plate, there was an apple pie with a heap of vanilla ice cream on top.

“I tried making this recipe Akane taught me. But it’s not as good as hers,” she said. She carefully steeped the tea leaves, and then poured the tea into my cup.

“Yesterday,” she said after a pause, “Sonoko was at my house again.”

I had guessed Itsumi had wanted to talk about it after all. Sonoko hadn’t been at the book discussion yesterday, so I thought that might be where she was.

“My mother was out volunteering and my brother was at his after-school club, so neither of them were home. I rushed back home after our book discussion yesterday and saw Sonoko just about to leave through our gate,” Itsumi said with disgust.

“Did you ask your father about it?” I wanted to know.

“I was going to, but didn’t. I want to gather evidence first. Last time he caught me he got angry and told me I was awful for searching through his library.”

“How are you going to find evidence?”

“I’ve actually set up a hidden camera in the library. I’m excited to see what I’ll find.”

Itsumi’s gaunt cheeks twisted into a grin that, suddenly and instantly, crumbled into tears. “Ohh, I hate Sonoko…”

Large teardrops fell from her eyes. That happy family was where she felt she belonged. Sonoko is disgraceful for recklessly trying to destroy that.

“Itsumi…Is there anything I can do to help?” I put my hand on her shoulder as she wiped her tears away with a thin finger.

“Are you worried about me? You’re a wonderful girl, Mirei. Really, you are. Maybe that’s why I feel like I can tell you just about anything. I’m glad I got to talk to you about it.”

She took a long look at me and, as if suddenly remembering something, removed a barrette from her hair. It was black and had a rainbow-colored crystal embedded in it. The sleek Rococo design really set off Itsumi’s chestnut-colored hair.

“This is for you. I think it’ll look better on you.”

“What? No way.” I politely declined, but she pushed the barrette into my hand. I imagine it was very expensive.

“I can’t accept this,” I said.

“I want you to have it. In honor of our friendship.”

With her words, Itsumi had recognized that we were friends and equals, not just a junior and senior in the same school. Those words were far more important to me than an expensive hair accessory.

“Are you really sure I can have it?”

“Yes, go ahead, try it on.”

I pushed my hair back towards my ears and fastened the barrette.

“I knew it would look good on you. Please keep it and think of me.”

Now that I look back, those words sound so ominous. It was as if she were leaving a memento behind.

Itsumi died soon after that.

I continue to feel regretful.

Why didn’t I stop Itsumi when she said she was going to collect evidence? Sonoko is devious, someone who would secretly seduce a friend’s father. Even if Itsumi had found enough evidence to incriminate Sonoko, I should’ve known that Sonoko would have done anything to silence her.

One week has passed since Itsumi’s death. Who murdered her? Everyone is searching for the truth. But I know who did it. The person who pushed Itsumi off the terrace is none other than Sonoko Koga.

I can still see it. Itsumi Shiraishi’s corpse lying in a bed of flowers. Her pale hand in the stretcher that took her away. And the lily-of-the-valley she held in her hand.

She must have picked the lily from the flower bed with her last bit of strength.

She was trying to tell me who the murderer was. That the girl who had killed her was the one who smelled of lilies.

(The End)

Thank you for reading, Mirei Nitani.

It’s nerve-wracking to be the first batter up. Not to mention that you’re a new student here, so that was your first mystery stew reading ever. But I knew you’d be courageous enough to do it, which is why I thought you would be a nice choice to go first.

It was a straightforward story, very “you,” I think. You’re right. Itsumi did seem troubled these past few months. She had this serious scowl on her face every time we met, as if she had been deep in thought. And she was often in a daze in the salon.

I asked her what was wrong many times, but she always just gave me this sad smile and would never tell me anything. Here I am boasting about being her best friend, and yet she wouldn’t even talk to me about what was bothering her.

I’ve never heard those things about Itsumi’s father before. She never talked to me about her family. I only know that she respected her father a lot. She loved him so much that she said she wanted to marry someone like him if she were to settle down and have a family someday. Everyone’s heard her say that more than once, right? She definitely had a “father complex.” It also didn’t help that he really spoiled her.

But then all of this happened. Ahh, I really should have asked her more about it. I feel guilty, ashamed, and terribly angry with myself.

What? You say that she couldn’t tell me certain things because we were so close? Thank you for saying that. You’re right, that’s probably what it was. Perhaps this is territory that best friends, especially, feel they shouldn’t infringe on. That makes me feel a little better.

But still, I’m shocked that you’ve identified the culprit so quickly. I’m sure the rest of you are bursting with questions, but let’s wait until after everyone has read us their stories.

That black barrette in your hair is Itsumi’s “memento,” the one that you just told us about, right? It’s lovely. It looks nice on you. I could see why she wanted you to have it. It looks pretty in your light hair.

Could you show it to us a bit more clearly while you’re still in the light of the reading corner? Oh my, the rhinestones form a flower, don’t they? It really is very nice. Thank you very much.

Well, then, please return to your seat. It’s dark, so please watch your step. Everyone, please give Mirei Nitani a warm round of applause.

By the way, how’s the stew? If it’s really that awful, I recommend adding some curry powder or chili paste to give it a little kick. It’s funny. Your other senses become so much sharper in the dark, which makes good things taste better, and bad things taste worse. If the first ingredient added to the stew tastes awful, it will be a disaster from start to finish. But come on, please keep eating.

Well then, I suppose it’s time to move on to the next reading.

Akane Kominami, you’re next. Please head to the reading corner.

* Roughly US $100.

To be honest, I didn’t like Itsumi Shiraishi at first.

Actually, I hated her.

I had never spoken to or even met her, an upperclassman one grade my senior, but I knew all about her because she was basically famous at school. She wasn’t just the chairman’s daughter, she was also sharp-witted and stunning to look at. I used to stare coldly at her fans as they flocked in from the high school, junior high, and elementary school buildings and swarmed around her classroom.

Itsumi’s slender body and vivacious smile attracted attention everywhere she went. She had it all: Perfect proportions. Lovely facial contours. Big, alluring eyes. Lips like flower-buds, which emanated charm and grace. A refined air from her excellent upbringing.

You couldn’t have called Itsumi a “beauty” or some other cliché, it wouldn’t have suited her. She was an idol. Gorgeous in every way. Which is exactly why I didn’t find her beautiful.

Itsumi was too perfect. In confection design, for instance, bakers typically draw asymmetrical and uneven lines into dessert decorations to make them look sophisticated. But Itsumi looked too well-put together, as if her appearance had been meticulously calculated. She had no imperfections at all. Perfection isn’t beautiful. It’s tasteless.

I despised my classmates who fawned over Itsumi’s so-called “beauty.” They obviously had no idea what real beauty was.

When I heard that Itsumi revived the Literature Club after its years on hiatus, I shrugged it off as the whim of someone with too much free time. Besides, the club only had two members, with Itsumi as club president and Sayuri Sumikawa as club vice president, which only made my impression of it worse. Yet as soon as their tiny club was reopened, this magnificent literary salon was built and everyone in school was talking about the salon, which was supposedly “every girl’s dream castle.” However, rumor had it that you couldn’t get in unless Itsumi personally approached you, which only made the students admire her and her salon even more. Although I was only in my third year of junior high school at the time, the girls around me had already made it their goal to be invited in.

Right after I started high school, Shiyo Takaoka, a girl in my grade who won a big prize for her light novel, became the first new member of the Literature Club, and everyone was terribly jealous. What Shiyo said about teatime—the highest-quality tea leaves imported from England and France, the Meissen tea set, the Wittamer torte cake—would have made anyone swoon. The salon must have been awfully comfortable to make Shiyo want to turn down all those television appearances and magazine interviews so she could sleep in the salon after school instead. She also mentioned that she got a lot of writing done while sitting under the Baccarat crystal chandelier.

But I found it all repulsive.

The Baccarat crystal chandelier and the Meissen tea set.

Did a student literary salon really need all those things?

I grew up in my family’s traditional Japanese restaurant, where ever since I was a little girl, it was emphasized that “flashy isn’t classy.” No, elegance is unadorned, it has both wabi and sabi:*1 subdued, stately, with a quality of subtle grace and beauty that ripens with maturity. It is tasteful, unassuming, and true to itself. That is what real chic is.

Nothing in the gaudy literary salon of rumors seemed to have any of that chic. I looked down on the salon for its bad taste, and hated it for the same reasons that I didn’t like Itsumi.

My father is a stubborn, simple, old-fashioned cook who has declined television appearances and invitations from department stores for many years. Tons of people used to ask to publish a cookbook of his recipes, but he always sent them away, adamantly maintaining that the only thing a cook should do, is cook. He refuses to open a new branch. Despite the dozens of requests for take-out lunches and catering, he insists that he wants his customers to eat their food where it was made. The only time you could eat my father’s cooking outside of his restaurant is around New Year’s, when he gives his best customers a take-home lunch as a gift for the holiday season. He is the only one who can make it and it isn’t on the menu, which makes it a so-called “New Year’s fantasy.”

My mother owns a traditional Japanese confectionery shop and has supported my stubborn father all these years. Her seasonal traditional desserts, which she has spent decades creating, add color to my father’s kaiseki meals.*2 To go with the changing seasons, my parents get together and decide upon a theme with which my father carefully crafts each course, and which my mother follows for her desserts and restaurant decorations, which include ikebana flower arrangements and hanging scrolls.

I may have inherited this from my parents, but I’ve loved being in the kitchen since I was a little girl.

My father’s prized hearth rests on the traditional earthen floor. I was raised watching my mother wake up at five in the morning to fill the stockpot with dried fish and kelp to make three servings of broth for each of my four family members. The clear liquid she strained so meticulously became our miso soup at breakfast, the broth we had with eggs at lunch, and the stew with boiled meat, vegetables, and eggs at dinner. I was fascinated with how the liquid changed tastes and forms with each meal. I held my first knife when I was three years old. By the time I was four, I could handle knives quite well and even received a knife of my own that had my name engraved on it.

Although I was born immersed in the world of Japanese cuisine, as I grew up, I found cuisine from Western countries to be new and refreshing and eventually became obsessed. My parents had nothing to say about my new passion. They had already decided that my older brother would take over their restaurant and were training him in how to clean the restaurant in the early morning, stock up on food at the marketplace, precook and organize ingredients, and gave him a strict education that they never gave me. In fact, my father wouldn’t even let me into his kitchen. I always watched my brother’s training with envy. He was set to become the fourth successor of our restaurant, “Kominami,” which had been established in the Taisho Era. And no matter how well I held a knife, tried to cook, or perfected my Western sweets, to my parents, all of my efforts were nothing more than “wife training.”

My brother was a slacker who had no real interest in cooking or Kominami. He often shirked his kitchen-stocking duties to go goof off instead, and would ride around on his motorcycle at night instead of cleaning the restaurant. Even so, Kominami would automatically be his. Frustrated, I dove deeper into the world of Western cuisine. But I couldn’t bake cakes well in our old, antique kitchen.

That was when I heard rumors about the kitchen in the literary salon.

Supposedly, it was spacious, easy-to-use, and well-stocked with everything one could possibly want. Apparently, club members used to bake cakes and make mousse together in the kitchen.

I wasn’t interested in chandeliers, marble tables, fireplaces, or teatime. But when I first heard about that kitchen, I became fascinated with the club.

Of course, I will explain how I was able to catch Itsumi’s eye and join the club. But first, I must touch upon that terrible incident.

When the owner of a restaurant that my father had trained at in his youth retired, he asked my father to take his restaurant over and make it a branch of Kominami.

Although my father owed a great deal to this man, he wasn’t interested in his offer. It wouldn’t just be expensive to open a new restaurant; two restaurants would also be harder for my father to manage. My father firmly believed that there shouldn’t be another Kominami unless he was there to hold the knife. But he couldn’t flat-out refuse the old owner’s request. I saw that my father had no idea what to do, so I suggested: What if the new Kominami served Western cuisine?

If the new Kominami was a Western-style restaurant, my father’s guests would understand why he wasn’t overseeing the kitchen, since Western cuisine is not his specialty, And this way, he wouldn’t have to reject the original owner’s offer. My father was impressed by my idea and promptly asked me to design the layout and menu for the new Kominami. He even said that he would eventually let me manage the new restaurant, and that he would put it under my name so I would own it one day myself.

My father had finally given me more recognition than my brother. I was ecstatic.

Whether on the train to school or in between classes, the new Kominami was always on my mind. I showed my best rendition of its menu to my father’s friend, who was to be the chef at the second Kominami, and I picked out silverware to match the items on the menu. I was also set on perfecting my desserts. Cake, pudding, mousse, Bavarian cream, ice cream, tarts. What if I had takeout desserts! During those blissful days, I was bursting with ideas and let my imagination run free.

I had no idea how quickly my dreams would disappear.

One day, Itsumi Shiraishi approached me by the shoe cubbies after school.

“You’re Akane Kominami, right?” she asked.

I am rather small, so it felt like I had to look far up to see her face. Her skin looked as smooth as freshly whipped cream, and her lips glistened red as if soaked in cherry syrup. She was shockingly beautiful. The underclassmen glanced at us as they passed.

“Yup,” I answered curtly.

Most students would have probably been thrilled to be approached by Itsumi, but I wasn’t a fan of hers. In hindsight, I think my response was pretty unfriendly.

“I read your report on The Setting Sun. It was intriguing,” she complimented me.

Even though I don’t read a lot of books, the report she referred to had somehow caught the eye of Mr. Hojo, my Japanese language teacher, who had it published in the school newspaper. The report was something I had just kind of thrown together, the type of essay an older teacher would’ve scolded me for not taking the assignment seriously enough. But Mr. Hojo, who is still in his twenties, probably enjoyed the essay as much as my classmates did because he was closer to us in age.

“I like how you analyzed the main character, Kazuko, by comparing her to the modern-day single mother,” Itsumi continued. “It was very unique. I want to ask you more about your essay. Would you like to join me in the salon for some tea?”

I suddenly remembered the fabled kitchen. I wanted to see it, but I didn’t really feel like talking to Itsumi.

“No, that’s all right.”

“Why not? Please come for a visit. I just finished baking a pound cake.”

“Did you make it yourself?” At her words, a small twinge of rivalry sprouted inside me. I wanted to show off the kind of cakes I could bake.

“I did. You can’t have a book discussion without dessert. We also need to make tons of sweets so we can sell them at the school events and fund our club.”

A kitchen. A kitchen where I could make tons of desserts.

“Umm…is it gas or electric?”

“Is what?”

“The oven.”

Itsumi looked puzzled for a moment and then burst out laughing. “Haha! It’s a gas oven! You’re a funny one. No one’s ever asked me that before.”

So I accepted Itsumi’s invitation and we went to the literary salon.

When I saw it, it was the ideal kitchen. It was spacious and clean, and had L-shaped counters and an island. There were three large kitchen sinks with spray nozzle faucets. There was a silver industrial refrigerator. A stand mixer. Yeast leavening equipment. An ice cream machine.

“This is amazing…” I let out a deep sigh as I caressed the polished countertop. The cold marble. With a countertop like this, I could easily knead pie dough or even temper chocolate. Oh, what luxury!

“And here are the ovens. Do you like them?” Itsumi pointed at the three gas ovens lining the wall. Each one looked like it could take two or three 8-inch round cakes at a time.

“They’re incredible.”

I opened the door next to the ovens to discover a walk-in pantry. Flour, wheat, sugar, silver candy pearls, nuts, sticks of vanilla, canned fruits, jam, honey, colorful spices…How many kinds of desserts could I make with these? I could have just stared at the stylish packages of imported goods all day. I could have spent the whole day just sitting there.

Bowls, spatulas, whisks, and other culinary utensils lay in an orderly line. I knew that everything was top-notch because of the research I had done for my new restaurant.

“It’s fantastic. Way better than the one in my restaurant.”

“Your restaurant? Ah, you mean your family’s restaurant.”

“No, I’m going to have a restaurant of my own.”

“You will? Wow, that’s great!”

“I’m going to make lots of desserts at my restaurant. Oh, this kitchen is perfect. Definitely a good source of reference for me.”

After that, we ate Itsumi’s pound cake while we chatted about novelist Osamu Dazai, which was the figurative “icing on the cake.” Itsumi’s cake wasn’t bad, either, though I suppose anyone could make something tasty with the kind of kitchen, ingredients, and equipment that she had at her disposal.

We had so much fun talking that we lost track of the time.