Contents

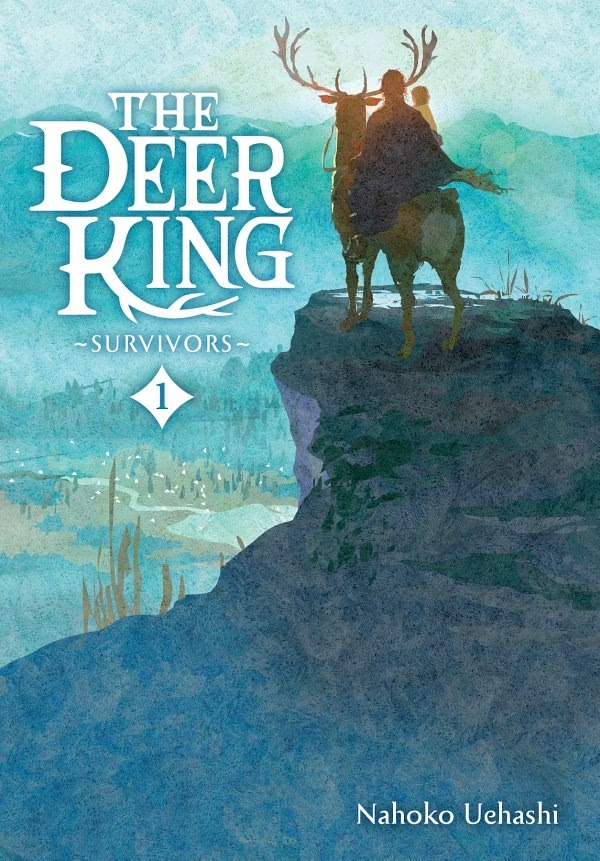

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Pika Palu Eggs

- Chapter 1: Survivors

- 1 Bitten

- 2 First Encounter

- 3 Light in the Ashes

- 4 Out of the Mine

- 5 Pyuika in the Mist

- 6 Rite of Love

- Chapter 2: A Plague from the Past

- 1 Devil’s Spawn

- 2 Into the Mine

- 3 History of the Disease

- 4 Subterranean Streams

- 5 The Village of the Molfah

- 6 Following the Trail

- 7 Vanished into Snow

- Chapter 3: In the Land of the Reindeer

- 1 Preparing for Winter

- 2 Mohoki

- 3 Yuna

- 4 In the Summer Forest

- 5 Summer Light

- 6 Golden Sunbeams

- Chapter 4: Black Wolf Fever

- 1 The Royal Hunt

- 2 Attack of the Black Dogs

- 3 Two Different Approaches

- 4 In the Hall of the King of Aquafa

- 5 Outbreak

- 6 Battling the Disease

- 7 The New Remedy

- 8 Allergic Reaction

- 9 The Curse of Aquafa

- Chapter 5: Inside Out

- 1 Rumors

- 2 Change

- 3 The Raven

- 4 A Messenger Bearing Wet Feathers

- 5 The Woman in the Bath

- 6 The Echo Master

- 7 Behind Me, My Child

- 8 A Burning Arrow Piercing the Darkness

- Chapter 6: In Pursuit of Black Wolf Fever

- 1 Stepmother, Stepsister

- 2 Tomasolle

- 3 The Head of the Inner Circle

- 4 A Bleak Winter Village

- 5 Toxic Grain

- 6 Makokan’s Home

- Yen Newsletter

List of Main Characters

Van

Leader and sole survivor of the Lone Antlers, a band of warriors who resisted the Zolian invasion. He was captured and enslaved in the salt mine of Aquafa.

Yuna

A little girl Van rescued from the salt mine.

Tohma

A young man from Oki who was saved by Van after being injured.

Ohma

Tohma’s father.

Kiya

Tohma’s mother, a Zolian who emigrated to Oki.

Hohsalle

A gifted physician and descendant of the Ancient Kingdom of Otawalle, which fell to ruin two hundred and fifty years ago.

Makokan

Hohsalle’s servant.

Milalle

Hohsalle’s assistant.

Limuelle

Hohsalle’s grandfather. A renowned physician who cured the Zolian emperor’s wife of a fatal illness.

Tomasolle

Hohsalle’s brother-in-law and head of the School of Living Creatures at the Otawalle Academy of Deeper Learning.

Shikan

Tomasolle’s assistant who belongs to the Ahfal Oma, the People of the Fire Horse, on the Yukata Plains.

King of Aquafa

Ruler of Aquafa, a kingdom subjugated by Zol. He has pledged allegiance to the Zolian Empire.

Sulumina

Niece of the King of Aquafa. Wife of Yotalu, an influential Zolian.

Tohlim

The king’s confidant. Known as the living encyclopedia of Aquafa.

Malji

Leader of the Aquafa Slave Trackers.

Sae

Malji’s daughter and one of the best trackers.

Suohl

Also known as the Echo Master. An old shaman who lives in Yomida Forest and who can transfer his spirit to a raven.

Natalu

The Emperor of Zol. He has placed great trust in Limuelle ever since Limuelle saved his wife from a fatal illness.

Governor Ohan

A Zolian governor who rules over the former Kingdom of Aquafa, now the province of Ohan. Hohsalle saved his life.

Utalu

The governor’s arrogant and overbearing eldest son.

Yotalu

The governor’s second son. Possesses an intellectual disposition.

Lona

The chief priest-doctor of the provincial governor.

My spear, these shining antlers,

Fearless, unfettered.

Behind me, my fawn.

Bend low, Antlers, to shield this young life.

The Deer King

The boy burst into the room with an anguished cry. “Grandfather!”

A man in his prime looked up and placed the book he was reading on the table. “What’s wrong?” he asked.

The boy scrunched up his face. “The pika palu are dead!”

The man pushed back his chair and stood. He and the boy strode off toward the room where the pika palu, the shining leaves, were kept.

Sunlight poured through a large bay window that looked out onto a courtyard. A huge aquarium stood in the room. Green fronds swayed in the clear water, and beneath them floated dead gray leaves. The boy peered at the tank and then gazed up at his grandfather. His lips trembled.

“I looked after them properly, just like you told me. I changed the water and—”

The boy’s grandfather laid a hand on his shoulder. “It’s all right. It’s not your fault.”

“But!”

“Relax. Look closer. Do you see something on the weeds?”

The boy frowned and stared at them, pressing his forehead against the glass. His eyes grew round. “Oh!” he breathed. Countless tiny beads clung to the leaves. He looked up at his grandfather. “Eggs?”

The man nodded. “That’s right. Eggs.” He looked into the tank. “Every pika palu dies as soon as it has laid its eggs.”

The boy’s face clouded over. “They die without raising their children?”

The man nodded. “Pika palu aren’t the only living things that must fend for themselves from birth. It’s the case for a surprising number of creatures.”

The boy gazed into the aquarium as though lost in thought. “But why? Why do they die as soon as they lay their eggs? Do the eggs kill them?”

His grandfather shook his head. “No.” He fixed his eyes on the leaflike objects floating silently in the tank. “They already have the seeds of disease inside them.”

“They what?”

“Pika palu carry the seeds of disease within them.” His grip on the boy’s shoulder tightened slightly. “All living things do. They live for as long as they endure but perish once they give in.” He sighed. “Just like everything else in this world.”

1 Bitten

Once again, he dreamed of dappled sunlight.

If he looked up, he would see snow-covered mountains far in the distance.

He sat on a sun-heated rock, his fishing line trailing in a mountain stream in his homeland.

Why?

Why did he have the same dream every night here in the slime-smeared bowels of the earth?

The stream—it was so beautiful. Tree branches lazily stretched over the water. Come autumn, their leaves would weave a tapestry of red and gold across the stream.

A withered leaf, its life force spent, fluttered onto the water’s surface, casting a small shadow on the streambed while it was swept away.

Someday, that will happen to all of us.

Resignation pierced his youthful heart like some divine revelation as he watched the leaf yield to the torrent.

Was that what drew him repeatedly to this same swift-flowing stream?

Van grimaced. If that’s the case…then I’m a fool.

Strangely, he never dreamed of the battle along the banks of the Kashuna River, where Zolian forces had crushed him and his men like twigs in a vise. Van had loved his comrades like brothers and, during his waking hours, graphically recalled how they were cut down before him. Yet he never saw them in his sleep. He never dreamed of the foul, greasy net that had snared him as he stood, alone and spent like a worn-out rag, in the corpse-strewn field. Nor of the events that had led to his incarceration in this horrible place, a salt mine of Aquafa.

However, there was one face that surfaced in his dreams at times. That of the first man he ever killed—an officer astride a magnificent steed bellowing instructions from behind his troops. The desperate fight in the mountains of Van’s native land had only just begun. From afar, the man had seemed the epitome of an arrogant Zolian commander. When Van had skillfully cut him off from his forces and charged his flank to put an arrow through his breast, the man’s head jerked backward. As the Zolian’s helmet toppled off, the face revealed had been far younger than Van envisioned. The Zolian’s youthful countenance as he stared in fascination at the arrow protruding from the links in his armor. The surprise in his eyes—Am I really dying?—followed by the certainty—Yes, I’m dying. The man’s grimace of fear and agony. All these images remained seared in Van’s memory.

Van had gone on to kill countless men in the ensuing conflict. Eventually, death became commonplace.

And here he was, confronting death once again.

Two months had passed since Van’s imprisonment in this hellhole, where the survival rate was at most three months. Mine slaves toiled like ants, descending deep into the earth to fill their baskets with rock salt. Then they trudged back to the surface with the load biting into their shoulders, continuing the process all day. At night, they slept shackled to iron pegs buried deep in the rock wall. Come morning, the routine began again.

When he arrived, Van had thought that if he kept kicking the base of the iron pegs he was shackled to, they would loosen eventually. Yet they were embedded so deeply into the rock that no matter how many times he kicked, they never budged, and his body, pushed to its limit on the barest of rations, soon had no energy to spare.

Was his mind now preparing to give up, dragged down by his weakened physical state?

Fool…

How could a tree mercilessly felled in its prime possibly resign itself to the fate of a withered leaf? Van wasn’t young, but he was still only forty. He should have possessed the guts to keep fighting this yoke until he expended the last drop of life, and his body was worn to the bone.

But within the emptiness lurking at the bottom of his heart, he found only the barest thread of attachment to living. Perhaps that void would provide some comfort when he slipped at last to the bottom of the mortar of death, a reminder that this was all his life had come to in the end. Futility screeched and twisted in his gut at the thought, making him want to laugh, or weep. Yet he did not wish to choose death.

If ever Van did elect to die, he could surely find many ways to do so, but he did not want to give in to the pain and take his own life. He knew he must persist until the last spark within him faded.

He heard the quiet, rhythmic knocking of the ventilation fan that sent a meager flow of air to the dark recesses of the mine. Stirred by a groundwater-propelled wheel, it pushed the air down a long series of wind boxes. That feeble breath was the slaves’ link to life. Sooner or later, the day would come when Van would hear it no longer.

Behind his closed lids, he saw a thin stream of clear water. A small voice whispered, “Clickety-clack, clickety-clack.” A toy waterwheel turned—the waterwheel he’d made for his son. Van recalled how his own father made one for him ages ago. It made only a faint splashing noise, but his son provided the sound effects, mimicking a real waterwheel. The boy’s breath, faint and soft, brushed against his upper arm.

Light filtering through the trees danced on the dry alabaster rocks on the far bank of the summer river. Birch bark dazzled white. Delicate green leaves fluttered, whispering in the wind.

His son looked up, then touched him on the elbow and pointed into the woods.

Ah…

A deer. A flying deer. A pyuika.

A buck stood in the dark green shadows among the trees. It was past its prime but surprisingly large. Its antlers climbed up to pierce the sky like leaping flames.

Van rose, took his son by the hand, and approached the great animal. Its form wavered like a heat haze, threatening to vanish at any moment. Gripping his son’s hand, he whispered, “Could it be…?”

Van’s eyes flew open. A scream sounded from somewhere. The beautiful light fled, and Van was yanked back to the foul stench and darkness of reality.

There it is again… Quite far off.

The ground beneath the mine’s surface was like a beehive, riddled with chambers left by salt extraction. The sound Van heard did not come from any of the slaves shackled on his level. He heard their voices continually. Morning, noon, and night, the chamber was filled with groaning, weeping, and bestial howls that could hardly be called human. The sounds were so constant that they had faded into mere background noise. The noise Van just heard was different, however. Perhaps that was why it had penetrated his consciousness.

Urgent cries echoed hollowly, piling to create layers of sound. Voices screamed in terror.

At first, the sounds had come from the upper tunnel that led outside, but the commotion rapidly descended farther down.

What is that?

Frowning, Van sat up just as the slave shackled nearest to the entrance of the shaft rose, dragging his chains. He saw the man’s figure, silhouetted against the torchlight from the main shaft, jerk back, and he heard him shout. A shadow slid like dark water into the chamber.

A dog…?

Van thought he saw a flash of fur in the wavering light, but it was too dim to discern the thing’s shape clearly. It resembled a wolf but appeared smaller.

An ossam?

Ossam were fierce and vicious mountain dogs native to Van’s homeland. The creature’s movements seemed similar. But what would an ossam be doing here?

The shadows of the slave and the beast merged in the doorway, and a scream rented the air.

The man sleeping beside Van bolted awake and peered into the darkness. Turning to Van, he called, “Uriya ki? Ono, logi?” but Van couldn’t understand a word. Almost all those working in the salt mine were either Zolians sentenced to death or slaves from conquered lands to the south. Van doubted that anyone else here came from Aquafa.

He shrugged at the man beside him, then looked for anything he could use to defend himself. If the chains that held him to the rock were fastened to his wrist, they might have served as a weapon, but they were fastened to his right ankle, which made them useless.

A pack of the black beasts rushed toward Van and his fellow slaves, attacking anyone they passed.

“Oja! Oja! Oja!” the man beside Van shouted while waving his arms to fend one of the creatures off, but it didn’t yield. When it leaped on the man, Van kicked its flank as hard as he could with his free foot. The beast gave a short yelp but twisted aside just before it struck the wall, kicking the rock with its feet and landing on all fours. Van marveled at the beast’s uncanny reflexes.

Golden eyes shone eerily in the dark, glaring at him as though in contemplation. Then a dark mass filled Van’s vision, and warm wind enveloped his face. The beast’s breath smelled curiously of green wood, like a split sapling. Fangs sank into the arm he instinctively raised to protect his throat. Viselike pressure was followed immediately by the pain of rent flesh. Groaning, Van grabbed the animal’s snout with his free hand and slid his fingers along its muzzle, jabbing them into its eye.

The beast released his arm with a squeal and staggered back a pace or two, its gouged eye closed. Instead of fleeing, it bit the leg of the next slave in the line and bounded deeper into the chamber, biting everyone it passed before vanishing into the darkness.

Van pressed his hand against the gash on his arm while gasping for breath. Although the wound throbbed painfully, it hardly bled at all. The other slaves chattered excitedly while clutching their wounds. Unable to escape, chained to the rock as they were, the terror had been intense, yet no one appeared grievously injured.

The man beside Van gripped his leg and cursed, “Ottaku ehzeh! Lagi logi, ged maieh!”

Van frowned at him.

Why?

Why had the beasts attacked?

Ossam or wolves would only attack people if they were starving or to protect territory or their young. Had they come charging into the mine because they were being chased? It was possible that they might bite instinctively if they were overcome with fear. But…

That creature wasn’t afraid.

The golden eyes that had met his for an instant had shown no trace of fear or confusion. Rather, they had been cold and calculating.

The eyes of a warrior. A warrior dispassionately obeying orders.

Van shook his head. There was no use thinking about it. He squeezed the gash on his arm and let the blood drip onto the floor.

It’s going to be pretty swollen by morning, he thought in disgust. But there was no use worrying about that, either. Van was suddenly overcome with exhaustion, as though his body were filled with lead. Perhaps it was a reaction to the sudden terror. Moving his chains aside, Van lay down and, with a deep sigh, closed his eyes.

The next morning, the slave girl who brought their breakfast moved clumsily, as if she, too, had been hurt. When she passed Van a bowl of thin gruel, he glimpsed what looked like a makeshift bandage made of rags wrapped around her forearm.

The slave foreman’s footsteps, which usually echoed through the chamber as he marched down issuing orders, sounded tired and listless.

On the third morning after the incident, the slave girl’s hands trembled violently, and she spilled the gruel. Even in the dim light, Van spied the rash on her face and hands. He wondered if she had rubella. Recalling the medicine his mother had given him as a child, he said, “Try drinking some tsukki, cocklebur powder, if you can find any.” Although he doubted she understood, his concern must have been evident, because she raised her eyes and smiled faintly. However, even smiling seemed to be an effort.

Seven days after the attack, the man beside Van failed to rise in the morning. He lay curled up in a ball, as though in pain. Van called to him but got no response. Reaching out to give him a shake, he found the man’s body was already cold. Van vaguely remembered hearing the man coughing violently in the night. He might have groaned later, but Van had been so exhausted that he only lay and listened. Now he wished that he had gotten up and rubbed the man’s back. Van’s body felt oddly feverish and heavy at the idea, pushing the thought to a distant point in his mind. Here and there, he could hear people coughing, a dry, rasping sound like withered branches rubbing against one another.

The next morning, four more of those who lay chained to the rock wall in Van’s chamber failed to wake. When Van left for work, he saw corpses scattered about the other chambers as well. The slaves who could still move and the slave drivers with their whips who supervised them all had racking coughs that grated in their chests.

Somewhere in his mind, Van knew a disease was spreading, but this didn’t trouble him. They won’t be forced anymore to carry these loads that bite the shoulders, shred the flesh, and scrape the bones. Soon, I won’t have to, either.

On the night of the eighth day after Van was bitten, he was seized by a splitting headache, and his body was racked by chills that made his teeth rattle in their gums. Fierce shudders rippled through him in successive waves, then gradually lessened, replaced by a soaring fever. His temperature was so high that he thought he must be breathing fire. Instead of visions of dappled light, he was assaulted by a horrendous nightmare that caught him in the throes of the fever.

A tree root stretched toward Van, reaching for the wound on his forearm. He screamed and tried to cover the gaping sore but found he couldn’t move. The root burrowed through the hole in his motionless limb, drilling its way up to his shoulder. There it forked. One prong headed toward his neck, while the other moved from his collarbone down toward his chest. Inching along, they separated into multiple tendrils that tunneled through his veins, spreading slowly through his body.

The pain was excruciating.

Van screamed soundlessly. Again and again, he prayed for oblivion, sure that he could no longer bear the pain. But in dreams, such prayers were futile. Van experienced the moment the root reached his brain in vivid detail. He had braced himself for stabbing pain, but instead, when it shot through a point deep inside his head, a hot rush of pleasure numbed his body. Van’s abdomen hardened from stomach to groin, and he arched back, trembling.

The ecstasy lasted a long time. His heart beat so fast that he felt it would burst. He couldn’t breathe.

When death felt near, myriad lights burst behind his eyes, then were sucked together by some unknown force, whirling and expanding. Luminous granules scraped against the inner walls of his body, which in turn slowly crumbled.

I’m falling apart…

Van’s body was dissolving into fine glowing particles. Even the solid rock that should have been beneath him shattered. Everything connected to him dissolved into light, tumbled into chaos, merged and mingled.

He saw himself reflected in each drop of light emanating from his disintegrating body.

Van hurtled back through time with dazzling speed. There was his wife with her playful smile. His son’s laughing face. His mother, father, and older brother. The door to his house. Wazu, his dog, trotting out from the door’s shadow. The smell of smoke from the hearth. The clear light of the sun dappling the ground through red leaves.

Don’t go.

Van desperately strove to stop the tide, to pull his disintegrating body back and bind the fragments together. The strength of that thought must have imparted some power, because, with agonizing slowness, the infinite grains of light that had burst forth in a shower now began to gather and weave themselves into the shape of his body.

2 First Encounter

Van awoke to a searing thirst. Groaning hoarsely, he forced his eyes open, audibly cracking the rheum that glued his lashes shut. The back of his hand brushed the cool rock wall. Everything appeared strangely bright. Van could even discern the downy hairs on his forearm. A scab had formed over the wound where the beast’s fangs penetrated his skin.

He vaguely remembered being delirious with fever and having a nightmare.

Last night…

Had it really been just the night before? Van had lost all sense of time. How long did he sleep? The dream had seemed to go on forever, yet even that memory felt nebulous, as if his mind had slipped into some blank space.

I’m hungry…

No. This was not mere hunger. The inside of his stomach felt like it was being roasted on a spit, and the sensation worsened by the second. Van’s hands shook. If he didn’t eat something soon, he might faint. But chained as he was to the wall, he could not go looking for food. He broke out in a fine sweat at the thought of how long he might have to wait for the morning gruel to arrive. He was thirsty, too. And dizzy… Yet those things aside, Van felt more clearheaded than he had in a long time—the clarity that came after sweating out a high fever.

Everything seemed so quiet. The only sounds to be heard were scurrying rats, insects, and the turning of the ventilation fan. No echoes of human voices, no traces of human presence.

Is it still the middle of the night?

An uneasy Van turned away from the wall and staggered to his feet. A shock ran through him at the sight that greeted his eyes.

Corpses lay sprawled across the chamber as far as he could see.

Both the man diagonally across from him and the man chained to the wall beyond had been alive last night. Now they, and every other on this level, were dead. Van knew at a glance that they weren’t merely sleeping. The torch had long since burned to ash, leaving only the faint glow from the shaft for light, yet he could see their faces clearly, still twisted in the agony of death.

Van began to shake in the stillness. His heart pounded, and his throat constricted.

What happened here? What’s going on?

Nothing made any sense. The only thing Van knew for certain was that he had to get out of here. Something inside him implored him to flee. That, and the gnawing hunger in his belly.

Leave. Now. Before it’s too late.

He broke into a dash, only to have his feet whipped from under him as the chain around his right ankle pulled taut with a clang. Van managed to catch himself with both hands before colliding with the rock floor.

Damn!

Anger erupted inside him. Van was filled with revulsion for this thing that held him and wouldn’t let him go. He grabbed the chain and pulled, letting rage fuel his muscles. The metal plate and bolts that attached the chain to stakes driven into the stone screeched in protest. Van knew he could never yank it off, yet he didn’t care. Spurred by a burning rage and bellowing with the effort, Van ground his teeth and pulled. The muscles in his arms and shoulders bulged and trembled.

Suddenly, Van felt one of the thick metal rings of the chain twist like toffee. Before his eyes, the loop widened, then popped, sending him tumbling over backward. He fell on his bottom in a heap of disheveled straw and gazed in amazement at the chain hanging from his hand. Then, coming to his senses, he leaped to his feet and broke into a run, dragging behind the severed length of chain still fastened to his ankle.

The rasping of his breath filled his ears as he raced up the gently sloping tunnel toward the vertical shaft that led to the outside world. He saw light far above. A thick rope swayed in the shaft, suspended from a pulley frame silhouetted against the glow. Grasping the salt-encrusted crossbars of a sturdy wooden ladder, Van hauled himself up rung by rung.

As he approached the upper levels, the shaft grew steadily lighter. When he reached the second level, he heard the tramp of horse hooves.

So it survived…

The horse must have heard him. It snorted and turned its head languidly to gaze at him from its wooden pen erected against the rock wall. Nothing else moved. Squinting, Van surveyed the chamber, but all he could see were dead slaves. He gritted his teeth and continued to climb.

Those beasts… Van pictured the creatures that had attacked the slaves a few days ago.

How had they managed to get down this ladder? No dog or wolf could have done that, let alone climb back up.

Then again…

Van recalled how nimbly the beast had twisted in midair before hitting the wall, turning the rock into a springboard to land on its feet. If its kind could move like that, Van wouldn’t put it past them to scale this narrowly hewn shaft by leaping back and forth from wall to ladder.

What were they?

The slaves died only after they were bitten. They were exhausted from heavy labor, but that alone shouldn’t have wiped out the entire lot. Occasionally, a chamber would fill with poisonous gas expelled from some underground pocket, but if that were the cause, the men sleeping near this shaft should have been spared. Van couldn’t imagine gas killing so many people on different levels.

Everyone had come down with colds and chest-splitting coughs, which Van was pretty sure began after the attack. He chewed his lip as he thought on the way the beasts had bitten each slave with methodical detachment, as if carrying out orders. But… If that was the cause of death, then why am I still alive?

His hand grasped the last rung of the ladder, and he heaved himself over the lip of the shaft and rolled into the chamber that led to the mouth of the mine. He squinted at the entrance. The westering sun dyed the rock wall a pale orange.

Late afternoon already? Not morning? How long did I sleep? Half a day? Even longer?

Van pursed his lips and stepped outside.

Golden light bathed his body. A cool autumn breeze touched his cheeks, and soft sunlight falling through rustling leaves gilded the world around him.

There was no trace of anyone else. The guards who manned the turrets to prevent escape and protect the mine, the slave drivers, and the foremen were nowhere to be seen. The faint drone of flies announced what had become of them.

Van shivered, chilled by the breeze. He had to eat. It didn’t matter what, as long as it was edible. Looking around, he spotted several buildings. When he was first brought here, Van had been blindfolded, and when he and the other slaves had carried salt out of the mine, they were jammed together and closely watched, affording him no chance to look around.

A lookout tower was the first thing to catch his eye. The row of houses beside it had to be the quarters for the overseers. To the east of those stood two other buildings, one large and the other small. Both sported several chimneys. Van believed them to be the kitchens where the slaves’ meals were prepared. The storage sheds beside them seemed to confirm this guess.

Van tried all the doors but found they were firmly shut. His hunger was so acute now that he abandoned all caution. He kicked the closest door, then threw himself against it repeatedly. It was likely bolted from within, for it refused to give way, even though it opened a crack. Van persisted until he heard a snap from inside, and the door flew open at last. He staggered inside and struck his shin on something hard. Swearing, Van rubbed his leg. Three chairs lay sprawled across the floor.

They must’ve barricaded the entrance with these.

Silence filled the room. A shaft of light came through a window, and dust motes danced slowly in the air. Women lay on the floor, caught in the dim light. One of them had died with her hand outstretched toward the water jug. They seemed to have collapsed in the middle of a meal. Slices of a bread called fahmu lay on the table, and soup had been spilled. Van remembered the ragged bandage on the arm of the slave girl who had brought the food.

If they barricaded the doors with those chairs… They must have been afraid of something. The beasts? That meant they had attacked here as well.

Shards of broken dishes had been swept into a pile in one corner of the room. Van could almost see the women, their faces pale with fear, sweeping the floor and discussing what had happened. They must have decided to bar the door at night so they wouldn’t be attacked in their sleep. A day had passed, then two, then three… Perhaps they wondered if they caught colds when the coughs began. Ultimately, they were forced to work despite their fevers and collapsed.

Van gazed at the dead women, recalling how his body had suddenly felt like a lead weight. Here and there, dark red spots colored the bloodless skin of the women’s cheeks and necks—possibly marks of the fever that overtook them.

Van’s head felt as if it were splitting in two, his breath came in painful gasps, and his body trembled. However, he could not bring himself to ignore the corpses of these women. Placing his shaking palms together, Van closed his eyes and prayed that their souls would be welcomed in the Land of Eternal Spring. Then, opening his eyes, he looked around.

The rich aroma of food had filled his nostrils for some time. Looking up, Van saw bundles of dried red peppers and garlic hanging from the ceiling, along with ropes of sausages. On top of a large cooking counter in the center of the room was a huge, round loaf of unsliced fahmu, obviously left there just after it had been removed from the oven.

This was clearly not where slaves’ meals were prepared. They were only given a sloppy barley gruel. Van had not seen sausages or fahmu for ages. He first strode over to the water urn, scooped out a ladleful, and gulped it down. The cold liquid tasted like sweet nectar. He drank until his thirst was slaked, then grabbed the fahmu from the counter, ripped off a chunk, and sank his teeth into it. The loaf was enough to feed a family of four, but he polished it off in no time, swallowing the first bite without bothering to chew, then tearing off another mouthful, then another.

Somewhere in the back of Van’s mind, a voice cautioned him not to eat too much. His stomach had grown accustomed to too little. “If you gorge yourself now, you’ll die,” the sober voice advised. But Van couldn’t stop. It was as though a bottomless pit had opened inside him, and no matter how much he ate, it would never be filled.

Van reached up and yanked on a string suspending a sausage rope, pulling it down. He bit into the salty meat. The cold congealed fat tasted unbearably good. Heat flamed through him like a dying candle springing back to life, sparked by the scent of meat after such a lengthy deprivation.

Finally, Van paused and wiped the back of his hand across his mouth. As he did so, he thought he heard something. He raised his head and listened intently. Yes, there it was again. It sounded like crying.

Did someone else survive?

Where was it coming from? By listening carefully, Van located the direction of the sound and stepped outside. The crying was clearer now.

Next door?

The adjacent building was quite large but cruder than the first. Its doors appeared similarly barricaded. Although Van was in better shape than before, he could not summon the strength to break one down this time. Perhaps he wasn’t desperate enough.

Looking around, Van saw a window set high on the east wall. He went back and retrieved the chair he had struck his shin on and, using it as a step, climbed through the opening.

The dimly lit interior was far plainer than that of the neighboring structure. Numerous earthen ovens stood in the sprawling kitchen, and large, blackened pots rested upon them. Doubtless, this was where the slaves’ food was prepared.

Here, too, the bodies of dead women, some quite young, lay motionless. Van gritted his teeth upon catching sight of the shackles around their ankles. These girls were slaves, too. When the war ended, they must have been rounded up from their homelands and brought here.

The ashes from the ovens had all been removed and piled in a bin, and the blackened pots had been washed and dried. Only two ovens had yet to be cleaned out, and the dark pots on top still contained gruel. After cooking for the men who labored in the mine, the women must have cleaned up and set to making their own meals when they succumbed.

Although still muffled, the crying was much louder than before, yet none of those sprawled on the floor appeared to be alive. One body toward the back of the room was propped against an oven, as if to block the firebox. The scarf covering the woman’s head was askew, and strands of hair clung to her cheeks. She looked to be only twenty-two or twenty-three. She likely perished while struggling to stay upright and keep her back pressed against the oven. The woman had fought through fever and hallucinations to guard whatever was in that oven from the beasts.

Van gently picked her up in his arms and moved her away from the opening. The crying became sharp and clear. Van peered into the oven and saw two dark round eyes, presently wide with surprise. A little child with tearstained cheeks gazed up at him, a crust of fahmu clutched in one round fist.

3 Light in the Ashes

Van woke with a start at the soft thud of a log shifting in the fire. How long had he been asleep? The sky visible through the smoke vent above was still dark. This was no time to be sleeping, but after Van had filled his stomach and tended to other tasks that demanded attention, he was overtaken by weariness.

Van spent the night in the slaves’ kitchen. After discovering the girl, he had left her where she was for the time being and went to look around while the light lasted. Unfortunately, he failed to find superior shelter. He’d already kicked in the door of the neighboring building, which meant it wouldn’t do. The slaves’ kitchen was a sturdy structure, and it was equipped for a fire. Van could also hide the little one in a firebox if those things attacked again. Plus, it was near the shaft to the salt mine. The kitchen was likely built here for transporting the slaves’ meals, meager as they were, into the mine. At this distance, it would be easy for Van to flee with the child into that labyrinth, if need be, and they would stand a better chance of escape in the tunnels, which crisscrossed underground.

Salt was akin to gold, and the Aquafa mine was a precious source of revenue. Once news of what had happened here got out, the place would be swarmed. Van needed to get away before officials and their soldiers arrived. But he had dared not venture into the darkness last night for fear the beasts still roamed about.

Men came to haul away the salt at regular intervals. Van didn’t know when they last visited, but judging by the stockpile in the storehouse, he doubted that they would return tomorrow. Still, he didn’t know how things worked and could not accurately guess when someone might come or why. There had to be merchants who delivered food and officials who regularly checked on work progress. Van had no choice but to stay here last night, but he judged it best to leave before dawn tomorrow.

His first task had been to search through the foreman’s house to find the key and remove the manacle around his ankle. When it cracked open and he felt the weight fall from his leg, Van was filled with a profound sense of release. Now he knew what a dog felt like when it shook its body after having its collar removed.

Van threw the shackle and broken chain down a vertical shaft, then returned to the foreman’s house and took just enough money to survive short-term. He was careful not to take more than needed, and he further concealed his theft by removing money from several places. Upon capture, a runaway slave would be whipped but not executed. No one was foolish enough to kill a horse or cow that could still be used. However, a slave who stole from or murdered his overseers would be drawn and quartered as an example to others. It was galling enough to have been made a slave, but the mere thought of being condemned by such biased reasoning made Van sick to his stomach. While he felt no twinge of guilt about taking the money, he didn’t want to provide anyone with an excuse to accuse him so unjustly.

Before sunset, Van had been able to gather clothes that would disguise the fact he was a slave. He also took a tinderbox, a dagger, and a sword in addition to the money. The sword’s blade was the slightly curved style favored by the Zolians rather than the straight ones Van was used to, but he couldn’t complain. His best find was a well-kept bow that fit his hand perfectly, along with a quiver of arrows.

Van returned to the kitchen with these items to find the little one still curled up in the oven, sucking her thumb. Her dark round eyes watched him. He crouched down, wondering what to do. Fleeing with a child was madness, yet Van couldn’t convince himself to leave her. She was a funny-looking little thing. The girl’s mother had been dark-skinned, like the people of the Yukata Plains in southern Aquafa, but the girl was fair, and the shape of her eyes reminded him of the Zolians. Although Van had no way of knowing the identity of her father, he could think of only one reason for her existence under these circumstances, and it made him sick. If he left the child here, even if she survived, the fate that awaited her would be the same as her mother’s, perhaps even crueler. Slaves were treated no better than livestock. If they were too much trouble, they would be slaughtered. Even if it were considered more profitable to let them live, they would never be treated as human beings.

“Hey,” Van said softly. The girl blinked. He stretched out his arm. She looked at it for a few moments, then reached out with her own small hands. Perhaps she wasn’t the type to fear strangers. He took her in his arms, pulled her from the oven, and set her down on the ground. She wobbled a bit but didn’t fall. “Mauma.” She reached for the body of the woman Van had laid to one side, and he held her steady so that she could bury her face in her mother’s breast.

She sobbed inconsolably. Perhaps she wondered why her mother didn’t wake and hold her. Van let her cry for a long time before pulling her away. She squirmed and flailed at him with her pudgy hands, but he picked her up and held her firmly in the crook of one arm while he set some water on to boil. Then he removed her clothes and sponged her clean.

Strangely, the girl’s crying didn’t bother him. He felt calm and detached as he washed her, as if he were watching himself from a distance. While wiping the filth from her skin, he noticed a long thin scratch that had scabbed over under her left ankle.

So she was grazed by fangs, too.

Van glanced at the scab on his own arm. “Another survivor, are you?” he muttered. Dozens of people had occupied the mine, yet only two had lived. He was struck once again by how odd this was.

The bath must have soothed the girl, because as soon as he wrapped her in a soft cloth, she fell fast asleep, still sucking her thumb. The weight of the sleeping child cradled in Van’s arms filled him with peace, as though the spot where he stood in this room full of corpses was lit by a warm glow. The body of the girl’s mother, which lay beside them, had already sunk into darkness such that only a gray lump was visible. In the dim light, the living and the dead, the floor and the ovens, melded into shadow. Only the damp heat of the child in his arms confirmed that there was life here.

The girl opened her eyes groggily a few times and whimpered a little as though in remembrance, but when Van laid her in the makeshift bed he’d assembled, she passed out again. The temperature had dropped drastically with the sun. Although it was preferable to the mine, which sucked the warmth from one’s body, Van still felt cold.

She must have felt it last night, too… Van was amazed that the girl had managed to survive. He lit a fire in one of the ovens to keep them warm and gazed absently at the sleeping child beside him. As he did so, sleep overtook him.

A bird cawed in the distance. Dawn was near. Van shook himself and rose, then stirred the embers in the oven. He added a stick, and the flames crackled to life. After filling a large empty pot with water, he put it on the stove and brought it to a boil. He then transferred the water to a wooden basin that had been standing against a wall to dry. That done, he removed his clothes—a patchwork of blankets and rags—soaked them in the hot water, and used them to wipe his body.

Van hadn’t washed in so long that his skin was covered in a thick scum, and the water turned filthy in no time at all. He dumped it out and added more, repeating the process several times. Once cleansed, he donned the clothes he’d stolen and threw the rags and dirty water on the garbage heap outside. By the time the first rays of sunlight appeared, he’d prepared and eaten his fill of hot porridge. He woke the little one and began spooning her slightly cooled porridge. She was still half-asleep and, at first, just rolled the food around her mouth with her tongue and spat it out. As she woke, however, she seemed to realize she was hungry. Her eyes grew bright, and she practically devoured the spoon and Van’s fingers along with it.

He laughed deep in his throat. “Hey, don’t eat my fingers. They’ll give you a stomachache.”

The girl peered up at him, eyes round. “Manma, onyage?” Van didn’t understand, but she was grinning at him happily, glad, it seemed, to have some food inside her. He gave her the spoon, and she began scooping up the porridge and eating it quite competently. The soft white light of the morning sun caressed her porridge-speckled cheeks. Mesmerized, Van gazed at the downy hairs glistening on her skin.

4 Out of the Mine

An imposing iron fence surrounded the salt mine. On the south side stood a gate that opened onto the broad road used to transport rock salt out of the compound and bring supplies in. The guards surely opened it each morning, but now, with no one to do so, it remained closed. Van could probably have located the keys if he searched the guardhouse, but he elected to climb the fence instead. He knew the top was covered with spikes to deter escapees and invaders, but he didn’t want anyone to guess from the open gate that someone had escaped. He took a discarded wooden tub and placed it at the bottom of the fence near the garbage heap. Climbing on top of this, he laid a frayed and thickly folded horse rug over the spikes. He threw his bag over first, then scaled the fence with the child on his back. Once on the other side, he stretched up and tipped the blanket back on the mine side of the fence. With any luck, people would assume that both bucket and blanket had merely blown off the garbage heap.

If they use the dogs, there’s no chance of escaping anyway.

Van realized he’d not heard a single dog barking. Several accompanied the slave foreman wherever he went, yet Van detected no sign of them anywhere.

Were they attacked, too?

If the dogs were tied up in the kennel when the beasts came, they could have been mauled to death. I should have checked yesterday. Unfortunately, it didn’t occur to him until now. I’m losing my touch. Before, Van would have noticed such details immediately. The endless days of hopeless slavery must have whittled away at his once well-trained mind.

Van stared at the forest that lay before him and sighed. The little one clung to his neck without a whimper. He’d strapped her to his back with the baby sling he found beside her mother. Perhaps that had reassured her. It had certainly made it easier to climb over the fence.

“Good girl,” Van whispered, jiggling her a few times.

“Nyaga, tonton!” she exclaimed. While Van gathered his luggage, she chattered away contentedly, probably quite used to being carried piggyback while her mother worked. Van slung the bow across his back, buckled the sword around his waist, and grasped the quiverin one hand and the bag in the other. Despite the load, Van’s body felt light and easy. Perhaps it was thanks to finally having enough to eat.

He set off into the forest thick with evergreens that stretched toward the heavens, obstructing the sun even in late autumn. It was quiet and gloomy under the trees, but the stunted underbrush made walking much easier where there was no path.

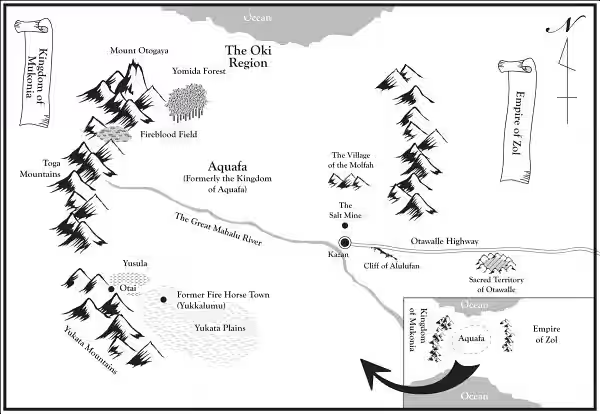

Van had no clear idea of what he would do next. His homeland, the mountainous Toga region, had already fallen into the hands of the conquerors. Toga was located on the westernmost edge of Aquafa, the last part of the kingdom to have been swallowed by the slowly advancing wave of Zolian troops. Against the mighty Empire of Zol, the mountain clans on the frontier had stood no chance. Even the smallest child had understood that. However, Van’s people had also known their existence would be little better than that of slaves should they give in without a fight. Fleeing hadn’t been an option, for the Kingdom of Mukonia was to the west, and it ruled its subjects with a cruelty that exceeded the Empire of Zol.

Aquafa had shrewdly allied itself with the invaders and became a province of the empire, thus ensuring its people the status of ordinary citizens. But the various clans scattered throughout the mountains of the Toga region were not regarded as Aquafaese, even though they spoke the language and had fought to protect its borders from Mukonian incursions. Under the King of Aquafa, the clans had been considered independent and allowed a loose autonomy in their own affairs in return for their allegiance. Thus, Zol refused to recognize the mountain peoples as citizens under its regime.

Only after devoting many years to securing a stable government in central Aquafa did the Zolians finally turn their full attention to the last stage of annexation: the subjugation of the Toga region. The King of Aquafa had sent messengers to each clan offering to negotiate with Zol for a guarantee of safety in return for allegiance to the empire. As the former ruler of a land that was now merely a province, however, the king could only parley to spare their lives. He had no say in determining the status of their clans. The involvement of a former ruler simply presented too many problems when treatment of clans in subjugated territory was tied to imperial management of the frontier.

It was Zolian policy to relocate lower castes to other parts of its conquered territory. Failing to receive ordinary citizen status like the Aquafaese meant the clans would be forced to leave their homelands and eke out a miserable existence in an unfamiliar place. After long deliberation, the leaders of the Gansa saw no alternative but to feign resistance. They decided to greet the invading forces with a band of daring warriors ready to fight to the death and demonstrate that they were not easily beaten and would make useful allies. This, they hoped, might allow them to negotiate for more acceptable terms should they offer to submit to Zolian rule and form a vanguard to protect the empire’s new western flank. If the Zolians recognized that the clans were well versed in the mountainous terrain and could serve as a buffer against Mukonia, the Gansa might be permitted to stay.

It was a band of death warriors known as the Lone Antlers that arose to challenge the Zolian forces and fight this hopeless battle. Its members were all men who, for one reason or another, had been robbed of normal lives. Ancient in origin, the band was said to have emerged when the gods first appeared in the form of pyuika, flying deer, and its members were exempt from the rules that bound the Gansa clan as long as they vowed to serve as its shield, giving their lives to protect it should the need arise. Even outsiders fleeing some calamity in their own land were welcomed as clansmen if they chose to join these warriors. It was the existence of the Lone Antlers that allowed the elders to even consider a strategy of quasi-resistance.

There was one other factor that made the elders’ strategy feasible. The Toga Mountains ran along the western border of Aquafa, which was constantly plagued by incursions. The would-be invaders brought disease in addition to war. Over the last few decades, successive epidemics had swept through the mountain clans, decimating the greater part of the population in some areas. As a result, many men who had lost their families to war or disease sought out the Gansa and joined the Lone Antlers, and its ranks swelled to unprecedented numbers.

When the elders had approached Van, leader of the Lone Antlers, with their proposal, he and his men accepted this mission eagerly, for each of them carried a burden of sorrow and despair.

At last, I have a legitimate reason to make that final journey to my wife and son, Van had thought. His parents, grandparents, and elder brother had all passed away, and life without his wife and child had long seemed empty and meaningless. While the Land of Eternal Spring warmly embraced those who died of illness, accident, or old age, anyone in their prime who gave in to sorrow and took their own life would find no welcome there. Pyuika Riders, in particular, were sworn to expend their lives for the glory of their comrades. Should Van break that vow, he would be condemned to walk the Road of Constant Day.

Van had occasionally thought that would suit him, wandering that white, never-ending road while dragging his long shadow behind him. However, if there really was a Land of Eternal Spring where his wife and son awaited him, he didn’t want to inflict the pain of disappointment upon them. The living had no way of knowing if such a realm existed, but since Van was going to die anyway, he would do so with his eyes set toward his loved ones.

From the day they had received the elders’ command, Van and his men plunged headlong into battle. They lured the enemy into the steep and rugged mountains and forests of Toga, then emerged without warning from the shadows of the trees or hurtled down sheer cliffs, outmaneuvering horse and rider with the lightning speed and agility of their pyuika. For almost two years, they resisted, and their tactics bore fruit. The Pyuika Riders struck terror into the hearts of Zolian troops, forcing the enemy commanders to consider retreat and to offer the tribal elders favorable terms for a truce. As the negotiations proceeded, the Lone Antlers continued to play the part of fanatics defying the elders and fighting to the death. Then, having fulfilled their mission, they fell.

The elders and the clansmen are wise, Van thought. They would not let the lives of the Lone Antlers go to waste. Surely they must have wrung whatever advantage they could from our efforts. While Van worried about what had become of his homeland, he knew the success of his guerrilla campaign had also won him many enemies among the Zolians. To return home would be to risk capture and further suffering for his people, something he wished to avoid at all costs.

The dark green branches shook in the breeze, scattering splinters of sunlight across the forest floor. I was already a dead man, Van mused. How ironic that he had managed to survive even the battle at Kashuna River and the attack on the salt mine.

“Ocha, tonton?”

Van laughed as a pudgy little hand tugged on his ear. “Hungry, are you?” The girl was toying with his earlobe instead of responding, pulling and twisting as though it was very entertaining. It didn’t hurt, and he let her play, but the sensation awoke old memories, and sorrow pierced his heart. Van suppressed the feelings that threatened to rear their heads and dragged his mind back to the question of where to go from here.

So what shall I do?

Van knew the surrounding terrain quite well and what towns were located where. After the deaths of his wife and son, he’d wandered aimlessly for a long time. When rumors of the impending Zolian invasion had reached him, he and his comrades disguised themselves as merchants and explored Aquafa and other lands.

I guess we should head to Kazan first.

Kazan was a large trading center. Once the capital of Aquafa, it was now the seat of the Zolian governor who ruled the province. Van had been there twice. It was a confluence for traders from all parts of the empire, and he should be able to learn the latest news and maybe even find some sort of work there.

I’ll also need to locate a foster parent for the little one. There was a shrine in Kazan dedicated to the gods of all the peoples that converged on the city. Surely a priest would take pity on an orphan. There was no guarantee this plan would work, however. Van would just have to go and see.

The sky darkened, and it began to drizzle a little before noon. The dense canopy blocked the rain, keeping them relatively dry. Still, Van slipped the child from his back, took off his moku, a hooded cape, and then, after hoisting her onto his back once more, threw it over the two of them. She immediately began to fuss, seemingly annoyed by the hood over her head. Van was jiggling her on his back to quiet her when he smelled smoke. He paused in wonder. That one faint whiff told him the smoke came from a fire cooking wild boar. Van knew exactly where it was coming from, too. In his mind’s eye, he saw a young man, alone, tending a fire in a hollow shadowed by moss-covered rocks. The image flashed through his brain and was gone. He decided to steer clear of that direction and began searching for a trail. That’s when the child began to cry.

“Oncha, nyaga! Nyagaaa!” Pushing her hands against his neck, she arched backward, bawling at the top of her lungs. No matter how he rocked her or whispered urgently for her to hush, she simply would not stop. The commotion she made was so loud that it startled the birds from the trees and flushed the mice from the underbrush.

Van gave up any attempt at stealth. “Hey now!” he demanded. “What’s all the fuss about?” At that moment, he heard a faint voice from beyond the trees.

“Is someone there?”

The person spoke not Zolian but Aquafaese. And the accent was that of the clans along the border. Van started, thinking it must be one of his comrades, but the lilt at the end of the question informed him that it was someone from the north, so he decided to hurry on, ignoring the call. The tone, however, changed abruptly from a query to a desperate plea.

“If there’s someone there, don’t leave me. Please! Help me! I’ve twisted my leg and can’t walk!”

Van still would normally have ignored the entreaty. Woods like these were full of thugs who didn’t hesitate to feign an injury and then leap upon unsuspecting do-gooders to kill them for their valuables. But a vague sense of doubt stayed Van’s feet. He didn’t know why, but he knew with absolute certainty that the man was not only alone but merely a youth. The image that had passed through his mind at the smell of smoke seemed as real as if he had witnessed it with his own eyes. He wanted to find out why. He wished to see if there really was a hollow among some mossy rocks beyond those trees…

I must be crazy to go looking for trouble like this.

Van loosened his hunting knife in its sheath. Then, with the child still screeching on his back, he plowed through the underbrush toward the smoke.

5 Pyuika in the Mist

Three rocks stood in the shade of an enormous spruce tree. A young man sat in the hollow, leaning his back against one of those rocks, his leg stretched out in front. His face was ghastly pale, and he looked as if he was about to faint from exhaustion. A reindeer cart like those used by the nomads of northern Aquafa stood beside him, but the reindeer that ought to have been hitched to it was nowhere in sight.

The youth was roasting a hunk of meat on a stick over a campfire. Although garbed in the reindeer hides nomads wore, his face illumined by the light of the flames was a strange mixture of features that Van could not place. His narrow eyes and flat nose appeared Zolian.

Is he a hybrid?

It had been many years since Aquafa came under Zolian rule. While some Zolian settlements excluded other peoples in an effort to protect the purity of their lineages, many intermarried with Aquafaese. This was particularly common in the north, where the first interracial generation was already growing up. This youth had to be one of them.

When Van stepped out from behind a tree and into the hollow, astonishment spread across the youth’s pale face. Clearly, he had not been expecting a man with a child strapped to his back. His gaze flicked to Van’s hand resting on the hilt of a dagger, and his eyes filled with fear.

“P-please d-don’t kill me!” The youth’s lips trembled, and he tried to back away. Judging by the tattooed lines across his cheeks, he’d already gone through the rite of passage and been recognized as an adult. While Van found it odd to see the marks used by the northern Aquafaese on one who looked so Zolian, he felt only a slight twinge of pity for the incongruity rather than any aversion. He looked around cautiously, then removed his hand from his weapon.

“How did you twist your leg?” he asked quietly.

The young man blinked. Color gradually returned to his face. “Ossam,” he whispered. Moistening his lips, he hesitantly related his story.

“I was on my way to sell hides in Kazan, y’see… That was three days ago now… Fallen trees blocked my usual way, so I tried a new route… But it turned out to be a heck of a long way ’round. When it got dark, I had to camp here. It must’ve been past midnight when this pack of ossam came out of nowhere, like a black wave… I jumped in the cart to hide, and they just flowed around it and disappeared. But my pyuika was scared silly and wound herself ’round that tree, practically strangling herself on the tether. I tried to untangle her, but she wouldn’t stay still. When I finally set her free, she yanked the rope and knocked me over. Then she ran off into the forest…”

Having twisted his ankle so badly that he could not walk, he had settled down to wait for someone to pass by. “I figured someone’d come through here on their way to or from the salt mine, but it’s been three whole days, and I was sure I was done for. I was scared out of my wits…”

He appeared so forlorn and helpless that Van found it hard to believe he was old enough to have been through the rite of passage. He stood silently gazing down at the youth. Then he turned and walked over to the tree where the pyuika had been tethered. The little one’s howling had ceased abruptly as soon as Van had reached the hollow, either because she was distracted by this new development or simply no longer bored. She was now entertaining herself by making clucking noises with her tongue. After stroking the bark where the rope had cut into the tree trunk, Van turned to the young man.

“You said you had a pyuika, right? I thought the northern clans only used reindeer.”

The young man looked suspicious. “You mean you don’t know?” When Van didn’t respond, the youth sighed. “Maybe it’s different where you’re from, but around the end of the year before last, we were told, official-like, that if we raised pyuika instead of reindeer, they’d cut our taxes. So everyone rushed to get pyuika from Toga. How were we supposed to know they’re so high-strung and hard to handle? Now everyone’s saying it’s not worth the measly cut in taxes. We thought it’d be easy. I mean, they’re just another kind of deer, right? What a mistake!”

Van smiled. Raising pyuika required certain skills. People who knew nothing but reindeer would have a hard time of it.

Now I remember…

Some time ago, Van had heard a rumor that the people of the Okuba clan, who lived near the Gansa, were rounding up pyuika and sending them to Aquafa. The Okuba had once been pyuika herders and nomads like the Gansa, but they surrendered to Zol much earlier, becoming serfs, and were now scattered across the province.

When they had heard that the Zolians ordered the Okuba remaining in the Toga region to supply them with pyuika, the Lone Antlers had had a good laugh. “We’ve given them so much trouble, they’ve decided to try riding pyuika themselves,” they had joked. It had not occurred to them to fret. Pyuika were nothing like horses or reindeer. Confident that it would be impossible to raise up pyuika riders in just a few years, they had expected the Zolians to abandon this attempt in frustration. However, the Zolians were evidently more determined than Van had expected.

I suppose my people might even be helping them.

As he mulled that over, the sound of the rain intensified.

“Oh great, now it’s gonna pour,” the youth grumbled. He shoved the firewood under the cart to keep it dry and then looked up at Van with pleading eyes. “There’s a tarp in the cart, but I can’t get up.”

Van slipped the toddler from his back and held her out. “Hold her for me.” The young man cradled the girl with a surprisingly well-practiced touch.

Van pulled a rainproof canvas sheet from the cart and made a roof over their heads by fastening it to the cart and a rock. It barely sheltered the three of them. Van sat down beside the others and pulled some fahmu and cheese from his bag. “Want some?” he asked, and the youth nodded.

“Thanks. There’s food in the cart, but my dang leg hurts so bad I haven’t been able to stand since yesterday. All I had was the meat I’d removed from the cart before this happened. Help yourself. It’s boar. Pretty tasty, too, thanks to the big acorn crop this year.”

Van smiled. “Looks good.” He cut off a hunk of fahmu and laid a slice of cheese on top. He skewered this with his knife and toasted it over the flames until the cheese melted into a glossy coating. He passed this piece to the youth, who nodded in thanks and reached out to take it. But just as his fingers grasped it, a little hand tried to snatch it away.

“Whoa there! Not so fast.” Laughing, the youth moved it out of reach. “Yours is coming. Hang on a minute.”

Van laughed, too, and handed the little girl a piece of untoasted fahmu for the moment. She must have been hungry, because she began munching on it diligently. “You’re just full of energy, aren’t you?” he said.

The youth raised his brows. “And she sure can yell.”

Van grinned. He was right. No one would have guessed she was a girl from how she cried. Her bawling had been so loud that it rumbled in his belly.

The three huddled together as the rain pelted down. Van toasted more bread and cheese, sprinkled the succulent boar with salt, and ate. The cheese was made from cow’s milk, and although it was not unpleasant, he felt it lacked flavor.

“You told me pyuika are hard to raise,” Van said. “Have you ever milked them?”

The youth eyed him with surprise. “You can drink pyuika milk?”

“Sure.” Van gazed into the flames. “Reindeer milk is sweeter and creamier than that from a cow, but pyuika milk is even creamier. It has a richer flavor, too. Cheese made from pyuika milk is the best.”

Through the incessant drumming of the rain on the tarpaulin, a strange sound came from the forest. Pwohhh.

The youth glanced toward the rain-drenched trees. “What’s that? Didn’t sound like an elk.” The forests of Aquafa were inhabited by huge elk that towered over men. In the fall, bulls in their prime sported magnificent racks of antlers, and cow elk would call them in high, strained voices like a muted horn.

The sound was so familiar that Van smiled without realizing it. “What’s your pyuika’s name?” he asked softly.

The youth looked at him questioningly. “What? Oh, Tsupi. In our dialect, it means ‘rebel.’ My father named her that. She’s pretty stubborn for a female.”

“I see.” Van stroked his chin. “Has Tsupi ever butted you in the back?”

The youth looked even more puzzled. “In the back? Yeah. All the time. She’ll butt me from behind when I’m least expecting it. Almost knocks me over. Didn’t used to. She only picks up bad habits, never any good ones.”

Van laughed. After a brief silence, he replied, “If I bring your pyuika back, will you introduce me to a fur trader in Kazan?”

“Eh?” The youth looked taken aback. “To a fur trader? You’re a hunter?”

Van gestured with his eyes to the bow he’d shoved under the cart to keep dry. “I’m a good enough shot that I can live off hunting, but circumstances prevent me from returning to my homeland. I was on my way to Kazan to find work. A fur trader would know the hunting rights in this area and the regulations. But they tend to be protective of their territory, so I doubt they’d give me or any other stranger the time of day.”

“Well, yeah, guess that’s true…” The youth’s eyes slid away as though he was thinking.

He’d probably recalled that he knew nothing about this man he shared shelter with. Fur traders were important customers to reindeer herders. The youth was surely considering what would happen if he introduced someone who ended up causing problems later.

Van smiled. This youth was a good man. One capable of thinking ahead. After finishing a chunk of boar, Van thrust the stick that was his makeshift roasting spit into the ground, brushed off his knees, and stood. Then he drew the lead line from under the cart. The youth looked up quickly, a question in his eyes.

“I’ll go look for her. Take care of the little one for me, will you?”

“Yeah, sure, but…”

Van pulled the rope taut in his hands and cheerfully replied, “You can think about whether you want to introduce me to a fur trader in Kazan on the way there. I was planning to go anyway. You won’t get there alone with that leg, so we may as well travel together, at least to the town gate.”

6 Rite of Love

Raindrops shook the foliage, and Van was drenched almost as soon as he stepped out from under the tarp. It was a cold rain, yet it did not bother him.

Pyuika were far more affectionate than the youth realized. Once they had bonded, they never forgot a friend and quickly succumbed to loneliness when separated. Butting was a sign of affection, and the fact that Tsupi had often nudged the young man in the back showed that she had become attached to him. She was far from home, and no other pyuika lived in these woods. Even if they had, a doe would not be accepted into a different herd. During any other season, there would have been no need to search for her. She would have returned to the youth as soon as the scent of ossam faded.

But this was fall, the mating season. Pyuika and elk were similar. Although pyuika bucks were smaller than bull elk, mature female pyuika were similar in size to cow elk, which made interbreeding possible. Van’s clansmen sometimes mated pyuika with elk deliberately to breed larger stock. Van guessed from Tsupi’s call that the scent of a bull elk had put her in heat, and she was wandering the forest in search of him. Still, she hadn’t gone far. If he could get close enough to see her, he’d be able to bring her back.

Van approached the tree where Tsupi had been tethered and squatted down to gaze at the wet leaves on the ground. As his eyes grew accustomed to the sight, he could vaguely discern the shape of hoofmarks. He could also smell pyuika urine, something he’d noticed when standing here earlier. When frightened, pyuika leaked urine as they ran. Van’s clansmen gave dogs this scent when tracking them.

Van felt a sudden quiver of doubt. Even when in estrus, the scent of urine did not linger this long. Three days had passed since the pyuika fled. Why was the scent so clear? Van could even tell that it was old. Not only that, but he could see the trail of urine speckling the ground in a dotted line like the silvery slime left by a snail.

He felt as though there was a sluice gate deep within his nose, perhaps right between his eyes. When it shifted, scents flooded his brain and were instantly transposed into images. But something inside him hesitated to open it all the way. What would happen if he did?

Van stood motionless in the gray, rain-drenched forest, struggling to control his pounding heart. What was happening to him?

Something had changed, and he sensed that it was rooted in the night of the attack. He was afraid to consider what that might mean. Deeply afraid. Yet a strange pleasure also pulsed deep within him. A feverish heat crawled across his skin. He felt as if a thin membrane was just ready to peel away. And when it did, he would come face-to-face with a new and lustrous self like a butterfly breaking through a chrysalis to spread wide its damp wings…

A sharp voice rang through his mind. “Don’t let go.”

Van closed his eyes and gripped the lead line in his hands.

“Don’t let go of yourself.”

Something warned him not to surrender to this strange sensation. Yet at the same time, he heard a voice inside his heart protesting quietly, “But it’s already part of me…”

Van drew a deep breath, then slowly opened his eyes. The smell of wet trees and earth soaked into his brain, gently easing the tightness in his mind. He sighed.

Time to bring back that pyuika.

He would follow the trail, visible to his mind’s eye, and bring back the doe. He would do whatever needed doing. And as he did, he was bound to see more clearly just what form this new self would take, even if he might not like it.

Perhaps because Van had mastered his feelings, the scent trail was much more distinct. When he followed it to the point where he could no longer see the flicker of the campfire between the trees, he noticed a small pool of pinkish liquid glimmering on the ground. A bull elk had marked its territory. The surrounding mud was trampled with pyuika prints.

So you’ve fallen in love, have you?

Van sensed the presence of deer beyond the distant timbers. He heard rough snorting and stamping hooves. The sounds mingled with the smells in his brain, and a vivid image sprang forward. Van closed his eyes and stared. Two stately bull elk stood facing each other, their impressive antlers lowered. Each snorted in warning, nostrils flared to smell its opponent.

Van opened his eyes and walked stealthily toward where he knew they would be. He peered out from the shadow of the trees. The scene before him was exactly as he’d imagined.

Massive bodies collided. The ground shook, and the air rang with the clash of antlers. Again and again, the two bulls locked heads and pushed, straining against each other with every ounce of strength for one simple reason: to proclaim their virility. One forced the other’s head to the ground, twisting its neck and pressing its face into the dirt. The weaker bull struggled, unwilling to capitulate, but the difference in strength was obvious, and it finally backed away, limping. The victor did not pursue but merely watched the loser disappear into the woods. The rain had stopped, and the late-afternoon sun gilded the grass. In this golden light, the victor and the pyuika enacted the rite of love with Van as their silent witness.

When Van returned to the campfire leading the pyuika, the youth’s mouth dropped open, and his eyes widened. “Tsupi!! How the heck did you do it?”

Tsupi kept nuzzling Van’s armpit. He stroked her nose and made a clucking sound as he tethered her in the shadow of the trees. Tsupi clucked back at him, shaking her head. After ensuring she was settled, Van walked over and sat by the fire. “Did you know that pyuika will come to you if you make that clucking noise?” he asked.

The youth shook his head. “No. The Okuba we bought her from said she’d come if we called her name. So that’s what I did.”

“I see. That works, too, but you should learn how to cluck with your tongue as well.” Van smiled as he warmed his cold fingers at the fire. “Your Tsupi will bear the young of an elk next spring.”

“She’ll what?” The youth’s eyes grew even rounder. “You mean pyuika can mate with elk?”

“Yeah. The calving is hard, but when successful, the young are very strong.”

The youth fell silent and gazed into the flames for some time. The child slept contentedly in his arms. The only sounds were the pyuika munching grass and the wood crackling in the fire. After a long silence, the youth looked at Van as though he’d awoken from a dream. “You’re from Toga, aren’t you? I can tell by your accent.”

Van nodded, then told him the story he’d prepared in advance. “I’m from the Maso clan. We live by herding pyuika and hunting, but my wife divorced me when I fell for an immigrant from the south. Not a very noble reason, I’m afraid, but that’s how I became a wanderer.”

The Maso consisted of just a few families that lived deep in the rugged mountains. The Zolians had not deemed it worthwhile to send in soldiers to subjugate them and left them to themselves. There was little chance that his lie would be exposed, for the Maso never came down from the mountains, preferring to ask neighboring clans to serve as middlemen in trading furs and meat.

“Maso? First I ever heard of them. Never knew such a clan existed.”

“It’s just a few families, so it’s not surprising no one around here knows of us. If you’re in doubt, ask the Okuba. They’ll know.”

The youth nodded but did not seem totally convinced. “What about the kid?” he inquired.

“The woman’s,” Van answered brusquely. “She got sick and died pretty quick.”

The youth blinked but asked no more questions. He shifted his gaze to the fire. After some consideration, he raised his head and looked at Van. “Thanks for finding Tsupi. I owe you.”

Van nodded. The youth licked his lips and continued. “If you’re set on it, I’ll introduce you to a fur trader, but if you’re looking for work, I think I can find you a job.”

Van cocked an eyebrow. The youth hesitated a moment, then said in a rush, “I mean, I can’t promise nothing because it’s up to my father to decide, so even if you come with me, if he says no, you’re outta luck. But as far as I’m concerned, it’d be great if you did.” He broke into a grin, and his face flushed. “Sorry. I run my mouth when I get worked up. What I meant was, come back with me. We’re a small clan and not well off, but we’ll find a way to feed you and the kid.

“See, a sickness took my elder brother. And my father’s got a bad back. That’s why I had to take the furs and meat to market on my own.” As the youth spoke, he seemed to make up his mind, and a strong light shone in his eyes. “If we’re going to have enough left over from taxes to survive, we’ve got to breed more pyuika, but for some reason, they don’t mate and they don’t bear young.”

The young man glanced at Tsupi. “If you’re right about her bearing young, we’ve got to make sure she delivers safely. But none of us has ever seen a pyuika calve, and you just said it’s harder when they’ve mated with an elk, right?”

Van nodded. “Yes, that’s true.”

“Well then, if you’d come live with us, you’d be a huge help.” He implored Van with his eyes. “I’m begging you. We can’t afford to lose Tsupi. I’ll convince my father and the others, so please come.” He offered a hand. “I’m Tohma yu Oki, Tohma of the Oki clan.”

Van accepted Tohma’s hand and gave his name in return.

Shafts of late-afternoon sunshine cut through the rain-drenched trees. Gazing at this luminous tapestry, Van recalled the stream in his homeland and the leaf swept away by the rushing water.

1 Devil’s Spawn

As they crested the gently sloping hill, the salt mine finally came into view through a gray curtain of drizzling rain. Figures scurried about like ants below. The dirt road, which was wide and well packed for transporting rock salt down the gradual incline, was slick with rainwater. Yotalu, the second son of the Zolian governor, rode ahead, the hooves of his fawn-colored horse slipping on the mud.

“They don’t have enough sense to use lime on these roads?” Hohsalle grumbled.

Makokan rode beside him. A towering, broad-shouldered man, he handled his high-strung black steed with ease. After overhearing this remark, he smiled wryly. “Why don’t you suggest that to Governor Ohan on your return?”

Makokan glanced at Hohsalle, who only shrugged. Hohsalle’s lips were blue with cold under his black hood. Makokan frowned. The mountains were chilly enough already, and the rain only made it worse. The long ride from the crack of dawn must have taken its toll on the mohalu, the young master. Makokan wondered if he should have tried harder to dissuade him.

Hohsalle raised an eyebrow, as if reading Makokan’s thoughts. “Stop worrying,” he snapped. “I’m fine.” Turning in his saddle, he dug in his heels and urged his horse to a trot. Makokan followed suit, still frowning.