Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Chapter 7: The Dog King

- 1 In a Woman’s Embrace

- 2 Following Yuna

- 3 Ohfan

- 4 Fire Horses on the Snowy Plain

- 5 The Voice of the God

- 6 Dream Visitors

- 7 The Dog King

- Chapter 8: People of the Frontier

- 1 Those Who Pull the Strings

- 2 Garrison Fires

- 3 Home of the Yusula Oma

- 4 Olaha, the Pyuika

- 5 The Attack on Zakato

- 6 Rescuing a Woman

- 7 Crescent Moon Over Antlers

- 8 The Lightning Squad

- Chapter 9: Ikimi’s Light

- 1 The Fire Horse Mound

- 2 The Yusula Oma Elder

- 3 Nakka

- 4 Milalle Falls Ill

- 5 The Stranger

- 6 Wolf’s Eyes

- Chapter 10: The Forest Inside

- 1 Van and Hohsalle

- 2 Disease-Free

- 3 While the Fox Goes Mad, the Pyuika Sleeps

- 4 Death Hidden in Life

- 5 Journey of Three

- Chapter 11: Dropped Knife

- 1 Multiple Webs

- 2 Reunited with Suohl

- 3 Inside-Out Wolf

- 4 Family

- 5 The Scent of Kinma Dogs

- 6 Tomasolle and Shikan

- 7 Pursuit through the Rain

- 8 The Visit of the Emperor’s Eyes

- 9 A Father’s Tale

- 10 Forgotten Piece

- 11 A Frightening Possibility

- 12 O Dancing Deer

- Chapter 12: The Deer King

- 1 The One Pulling the Strings

- 2 The Future of Otawalle Medicine

- 3 Physicians’ Weapon

- 4 Evening Light

- 5 Child with Good Intuition

- 6 Bearers of Okuba Ichii

- 7 To a Distant Wilderness

- 8 Companions

- Green Light

- Yen Newsletter

List of Main Characters

Van

Leader and sole survivor of the Lone Antlers, a band of warriors who resisted the Zolian invasion. He was captured and enslaved in the salt mine of Aquafa.

Yuna

A little girl Van rescued from the salt mine.

Tohma

A young man from Oki who was saved by Van after being injured.

Ohma

Tohma’s father.

Kiya

Tohma’s mother, a Zolian who emigrated to Oki.

Hohsalle

A gifted physician and descendant of the Ancient Kingdom of Otawalle, which fell to ruin two hundred and fifty years ago.

Makokan

Hohsalle’s servant.

Milalle

Hohsalle’s assistant.

Limuelle

Hohsalle’s grandfather. A renowned physician who cured the Zolian emperor’s wife of a fatal illness.

Tomasolle

Hohsalle’s brother-in-law and head of the School of Living Creatures at the Otawalle Academy of Deeper Learning.

Shikan

Tomasolle’s assistant who belongs to the Ahfal Oma, the People of the Fire Horse, on the Yukata Plains.

King of Aquafa

Ruler of Aquafa, a kingdom subjugated by Zol. He has pledged allegiance to the Zolian Empire.

Sulumina

Niece of the King of Aquafa. Wife of Yotalu, an influential Zolian.

Tohlim

The king’s confidant. Known as the living encyclopedia of Aquafa.

Malji

Leader of the Aquafa Slave Trackers.

Sae

Malji’s daughter and one of the best trackers.

Suohl

Also known as the Echo Master. An old shaman who lives in Yomida Forest and who can transfer his spirit to a raven.

Natalu

The Emperor of Zol. He has placed great trust in Limuelle ever since Limuelle saved his wife from a fatal illness.

Governor Ohan

A Zolian governor who rules over the former Kingdom of Aquafa, now the province of Ohan. Hohsalle saved his life.

Utalu

The governor’s arrogant and overbearing eldest son.

Yotalu

The governor’s second son. Possesses an intellectual disposition.

Lona

The chief priest-doctor of the provincial governor.

Kenoi

Former chief of the Ahfal Oma, the People of the Fire Horse. Now known as the Dog King.

Ohfan

Kenoi’s son and the current chief of the Ahfal Oma.

1 In a Woman’s Embrace

Blurred light touched his eyelids. Van groaned and forced his gummed lashes open. The bright flame of a campfire met his gaze.

He took a deep breath. His body felt like lead.

A voice drifted over from the other side of the fire. “How are you feeling?” A woman sat on a fallen log, staring at him. He stared back for several moments before he remembered her name.

Sae.

He tried to speak but could produce no sound.

Rising, Sae reached into a fir tree and grasped something. Then she walked around the campfire, knelt beside Van, and slipped her hand gently under his neck. She lifted his head slightly, and he felt something cold against his lips.

Snow. Virgin snow from the top of a branch. He reached out with his tongue and took a mouthful. It melted, soothing the inside of his fever-swollen mouth. His breath came more easily.

“Thank…you,” he whispered hoarsely.

Sae nodded. After raising Van’s torso, she rested his back against her body, exposing him to the warmth of the fire. Although slender, she seemed to feel no strain in that position. It was a bit awkward to be held by a woman Van barely knew, but the heat eased the discomfort in his body, which was stiff with cold.

The inside of his skull felt numb, and everything that had happened seemed strangely distant.

As he watched the sparks dance in the flames, he thought absently, Just like my father’s.

Van’s father had been good at lighting campfires and could even build one in deep snow where it was impossible to create a hearth. Making a campfire on top of the snow wasn’t easy. Even if one succeeded at the igniting, the melting snow would drench the wood and snuff the flames.

His father had shown him how it was done many times. “On days like this,” he’d said, “the first thing to do is chop down a birch tree.” He would fell a birch and split the trunk where the branches grew densest with his hatchet. “The bark is full of oil here. If you make sure the flame takes thoroughly, the tree will act just like a firepit.”

That was easier said than done. Despite his father’s instructions, Van had found it a challenging process to master. Yet this woman had accomplished it perfectly.

These thoughts sifted slowly through Van’s mind while the numbness in his brain gradually dissipated, and the scattered fragments of his memory pulled themselves together from the dark.

With a jolt, he remembered what he’d been trying to do, and a needle-sharp pain ran through his chest.

“Yuna…,” he gasped, then paused to gather his strength before asking, “How long was I out for?”

“Not that long,” Sae replied softly from behind. “It’s still the middle of the night. You’ve come out of it fast, so I imagine you’ll regain some feeling in your shoulder where the arrow grazed you.”

Van clenched his left hand and found that the numbness had lessened. However, it still felt as though he were clutching a wad of cotton. He opened and closed his fist, and a faint uneasiness wriggled in the bottom of his mind.

Who is this woman?

He recalled the figure that had stood partway up the cliff. When they met in the bath, he’d assumed she was just a nomad, but no ordinary wanderer would have known to shoot a flaming arrow into a hokuso tree. And judging by her words, she was familiar with poisons, too.

Suspicion welled up within Van, then shot through his chest.

Sae had slipped her arms under his and held him around the waist. Van subtly moved a hand to grasp hers, but before he could, she slipped her arms up under his armpits and around the back of his neck, pinioning his arms and neck. He hadn’t thought a woman could be that strong, yet she’d locked his joints like an expert.

“Don’t move,” she said. “There’s a poisoned needle in my ring.”

Something hard pressed against the nape of his neck—her ring, presumably. Van could break the hold forcibly, but it would risk being stuck by the needle.

“Who…are…you?” The pressure against his throat made speaking difficult, and he forced the words out through clenched teeth. “Why…?”

“I’m a Molfah.”

Van knew that name. He’d heard it a long time ago. He dredged up what knowledge he could from the depths of his memory. His breath tensed. “The King’s Net?”

From behind him, he heard a faint sigh.

“Yes.”

Van’s face contorted as he struggled to understand. “The king’s spies? But why me?”

Her breath touched his ear. The only sound was her breathing. Just when he thought she wasn’t going to answer, she said in a low voice, “I was ordered…to track the one slave who survived and escaped from the salt mines.”

She can’t be serious, Van thought, yet simultaneously, he realized that he’d half expected this. He gritted his teeth. Why would they spend all this time tracking one measly slave? And why was he being pursued by the Molfah, not the Zolians? It didn’t make sense.

“Why is the king chasing me? To turn me over to the Zolians?”

“No,” Sae muttered. “It’s more complicated than that.” Her voice trailed off into silence.

In that pause, another question occurred to Van. “If you wanted to capture me, why didn’t you just tie me up when I was drugged by the arrow?”

He felt Sae jerk, and then she released him and stepped away. As the warmth of her body diminished, a wave of frigid air washed over Van’s damp neck and back, and he shivered violently.

Sae peered down at him from out of reach. Her face, lit by the fire, held a deep anguish. She stood there silently for a moment, watching Van, then her eyes slid away, and she strode into the dark forest. The sound of her footsteps crunching on the thin layer of snow that covered the undergrowth faded into the distance, and a deep silence cloaked the world.

Van stared blankly after her, at a spot where the trees sank into the darkness. A sudden sense of loss overwhelmed him, like he’d made some irreparable mistake. He longed to call her back, but he clenched his fists and kept this baffling urge in check.

Call her back? Your pursuer? What’re you thinking?

Sae might have gone to get other trackers. Van thought to escape now while he could, yet he didn’t move. If she’d intended to make him a prisoner, there had been plenty of opportunities already. Leaving Van was as good as telling him to run.

Or maybe she thinks that I can’t.

Perhaps that was it. She knew that Van was looking for Yuna. She was a Molfah with superb tracking skills. Even if she left him on his own, she would have no trouble finding him.

But still… Van’s doubts lingered. He couldn’t deduce her goal. Confused questions built up like foam on the water.

The King of Aquafa was subservient to a Zolian governor, and as the salt mines no longer belonged to Aquafa, there should have been no reason for him to pursue an escaped slave. Van had led the Lone Antlers and killed many Zolian commanders. The most logical reason to hunt him would be to make a show of the king’s loyalty by presenting Van to the Zolians. However, even that seemed strange. Van couldn’t believe he was worth enough for the King of Aquafa to keep the Molfah on his trail for this long.

Sae’s voice whispering in his ear came back to him. “It’s more complicated than that.” Her words had been tinged with pain.

Van frowned. Even now he felt her gaze on him and remembered how she’d stood there, unable to speak her mind.

Why did she help me?

Hunting Van for two years must have been difficult. Yet when her prey had lay helplessly before her, she sat on that fallen log and waited for him to regain consciousness. Her fingers had placed snow in his mouth, and the way she’d held and looked at him…none of it matched her words.

Van buried his face in his hands. Something invisible had twined itself around him. Countless layers of thread bound and pulled him this way and that. But he couldn’t see who held the strings.

Yuna.

Where was she? Where was she spending this cold night? The thought that, even now, she might be crying in fear made Van impatient. He wanted to get moving. Hatred kindled in his chest at the idea of Nakka’s treachery. He’d pretended to be simple and honest, planning all the while to abduct Yuna.

But why?

Van recalled something—the rochai holding him at bay so that Nakka could steal away with Yuna.

The rochai…

Insight flashed through his brain like a streak of lightning.

The salt mines of Aquafa. Yuna and Van—the sole survivors. Yuna’s kidnapper, Nakka. The rochai linked these together.

Van and Yuna were being tossed about like playthings—by whom or why, he didn’t know. However, he felt confident the plan wasn’t mere extermination. If that was the aim, the enemy could have killed them many times already.

Van paused midthought, stunned.

So it must be the opposite… Our sole value lies in the fact that we didn’t die, that we survived the attack in the mine.

A bird called, shrill and short, from deep in the dark forest.

2 Following Yuna

The tree branches remained dark shadows, but the sky behind them was beginning to lighten. Dawn approached.

Van sighed and rubbed his face. His beard scratched his palm.

Time to go…

He’d slept lightly, waking frequently, and his head felt heavy, but the numbness in his body was almost gone. He wondered if he’d be able to find Nakka’s tracks. It had stopped snowing sometime in the middle of the night, but any prints were likely covered by then.

Van rose, pondering how to follow the trail. As he swept some snow off a branch and put it in his mouth, he recalled the scent of Sae’s fingers. Where had she spent the night? Her footsteps stood out clearly in the snow.

Should I follow them?

If she was in league with Yuna’s kidnappers, then perhaps she left tracks to entice Van into a trap, not lead him to Yuna. Van strode to the other side of the campfire and picked up the hatchet. Although the thought of walking into a trap on purpose made him uneasy, he didn’t hesitate. He could almost hear Yuna calling him, “Ochan, Ochan!”

Gripping the hatchet, Van examined the underbrush with a hunter’s eyes, then slowly began to follow the trail.

Van quickly realized that Sae had deliberately left her tracks for him to find. They were all over the place, practically shouting that this was a ploy. She must have known that Van would recognize how unnatural her trail was. Sae seemed to be taunting him, asking, “Do you dare follow, even though you know it’s a trap?”

But why would she do that?

Maybe she’s just guiding me, he thought. Wherever Sae had left a track, there was also the print of a boot worn by a man of Nakka’s build. Sae seemed to be following him. If so, perhaps she was using her Molfah skills to locate signs of Nakka’s passage and left an obvious route for Van to follow.

He scowled, realizing his heart still wanted to believe in her kindness. If he let such expectations blind him, he would get snared. Sae was leading him to the place where Yuna had been taken. That much was obvious. However, he had no idea why.

Nakka did not appear to be concealing himself, either. Rather, he’d walked under the trees where his tracks wouldn’t be covered by falling snow, preserving a clear trail that invited pursuers. Presumably, he’d drugged Van to put sufficient distance between them to evade capture before reaching his destination while leaving a path that was easy to track.

But why? Why would they both do this? What possible reason could they have for going to all this trouble?

For two days straight, all Van did was follow the trail. On the third, he stopped to hunt and fill his stomach with meat. Meat would warm his body. On the dawn of the fourth day, he doused his fire and set out with a renewed vigor, picking up the trail again.

As the sun climbed into the sky, its pure light fanned through the trees. Birds hopped from branch to branch, chirping as they went. Every time they landed, little clumps of snow fell to the ground. A fox slipped away through the underbrush, scattering the thin layer of snow that powdered the bamboo grass. Once the bright morning sunshine filled the whole forest, Sae’s tracks veered away from Nakka’s. The reason was soon obvious: smoke.

Sniffing the air, Van raised his eyes and peered through the trees.

Tents?

They were well camouflaged. Their colors blended with the hues of the forest, but there was no mistake. Tents stood ahead, beyond the trees. As Van’s eyes grew accustomed to the sight, he saw many.

He frowned. That must be his destination. Nakka had hoped to lure him here by kidnapping Yuna.

Van smelled dogs and heard them barking. The scent of smoke wafted to him, carrying with it the bustle of people busy with their morning chores. Approaching unnoticed was impossible. If there were no dogs, it might have been different, but there were. Should Van venture any closer, he’d be discovered even if he waited until after dark. He was on his own, and there was no time to devise a plan.

Which leaves me no choice.

After a slow, deep breath, Van strode toward the camp. He didn’t get far before he sensed creatures approaching covertly. They came not from the camp but from deep in the forest. The scent of beast filled his nostrils. A familiar sensation prickled his nose.

They’re coming.

The rochai. Those creatures were coming to him again. He could feel his body responding, trying to change into an animal…

Van hesitated for only a second, then gave himself up to the strange olfactory sensation that washed through him like a wave. In return for relinquishing words and human thought, he gained the eyes, ears, and nose of a beast, and a body that moved on instinct alone. Something spread from his nose through his head, and the scene before him changed abruptly. Van’s eyes widened. Curling his lips, he snarled.

The rochai halted without a command. They simply froze, and their tails drooped between their hind legs. When Van stepped toward them, they edged away.

Color faded from the world, and everything stood out starkly, silhouetted against the gray. Sounds and smells rushed for Van with a peculiar intensity. And there was more. He sensed countless invisible, pulsating threads connecting all things, wrapping themselves around the earth and stretching up into the heavens. When he walked, the mesh woven by these invisible threads pulled and warped, pushing against the rochai so that they drew back.

Tiny ripples appeared in the mesh, and Van raised his snout. Humans.

The scent of men. And of horse, although he sensed none here. Men moved toward him. They reeked of metal—a foul smell that emanated from the spears in their hands.

Someone spoke, and a voice reached him. Van stared intently at the approaching figures, raising his ears to catch the words.

“—en Antler, Van.”

The moment he heard that name, he felt his beast senses fade. As smells and sounds receded, color flooded back. The men who strode toward him, spears in their hands, wore scarlet sashes across their chests. They stopped outside the reach of Van’s hatchet but within range of their weapons, watching him. Although they exuded the cold power of skilled warriors, Van felt no fear, much to his surprise.

Bite…Want to bite… The thought came to him out of nowhere.

A pungent odor thrust up his nose to the crown of his head. Phantomlike images flickered in his mind and vanished, reappearing again and again, as though viewed through a red haze. He clenched his jaw and struggled desperately to resist that fiendish urge.

Am I going crazy?

It was as if he were two beings in one. The creature that longed to sink its fangs into these men struggled fiercely with the man who was appalled to see himself gripped by monstrous desire.

His temples pounded, and he could hear the blood rushing in his ears.

Taking a deep breath, he closed his eyes and waited for the impulse that racked him to pass. The muscles in his shoulders, arms, and rib cage spasmed as he wrestled with the demonic strength that swelled inside him.

A faint voice, like a distant echo, reached him from the bottom of the haze.

Don’t bite, don’t bite, don’t bite… You’ll kill them if you do.

Van hung his head and focused his mind on that quiet voice. His lifeline. The only cord to which he could cling if he were to ride out the impulse that shook him like a gale. He must not kill. Once he started, he would never stop. He would kill them all.

“Broken Antler Van.”

He opened his eyes at the sound of his name. His field of vision wavered. The figures before him became clear and distinct gradually. The rochai shook themselves, as if to escape a spell, then turned on their heels and raced into the woods.

The warriors watched them depart with relief and joy plain on their faces. A man with white hair that flowed down his back like a horse’s mane took a step forward from the group. “Leader of the Lone Antlers,” he said with a husky voice. “We have been waiting for you.”

3 Ohfan

Van was led to a large tent twice the size of the others. The men took his hatchet and ushered him, unarmed, inside. While they didn’t treat him roughly, neither were they gentle.

In the center was a hearth, behind which hung a large banner embroidered with a rearing horse, poised as though to charge. Its fiery red mane streamed in the wind. Three low stools were placed around the fire. The white-haired warrior walked around the hearth and sat in the center, his back to the banner. A middle-aged man and a youth were seated on either side. The clear resemblance indicated they had to be the old man’s kin, either his son and grandson or a nephew and grandnephew.

After placing their spears on a rack outside the tent, the other warriors entered and stood behind Van with their hands on the hilts of their short swords. The elder looked up at Van and gestured for him to sit, but he remained standing, gazing down at him.

One of the warriors behind Van stepped up and grasped him roughly by the shoulder as if to push him down. At that moment, however, Van dropped to a crouch. Taken by surprise, the man lost his balance. Van threw him on the ground in a reverse armlock and planted his foot on his neck. The men behind reached for their swords.

“Be still!” Van shouted. “Move and I’ll break his neck.”

The warriors froze, but the white-haired elder watched as though unconcerned. The corner of his mouth rose in a sneer. “Go ahead and kill him,” he said. “It’s only right that one who blunders should die. None of us will be of use to you as hostages.”

The cold gleam in his eyes made Van’s skin crawl. Van twisted the arm of the man beneath his foot, dislocating his shoulder. The man bellowed with pain, and his eyes rolled. While his cry still shook the air, Van leaped across the hearth and grabbed the old man’s face with one hand while twisting the man’s sword arm behind his back with the other. He then shoved the man’s face into the thin rug and pressed a knee against a vital point in his back. Van turned his attention to the warriors.

“Does the old man tell the truth? Is even he worthless as a hostage?”

The men’s expressions remained stony, but their eyes betrayed their consternation, flicking toward another part of the tent and back again. Van caught this subtle movement out of the corner of his eye and frowned.

“Kill him!” the elder croaked as he lay drooling beneath Van.

Van let the sound slide over him, keeping his eyes fixed on the men.

“You called me Broken Antler,” he said. “If you know that name, then you must know what else they called me.”

That earned a twitch from the man Van suspected was the elder’s son. Van focused his gaze on him as he continued. “I hate so-called leaders who treat the lives of their soldiers like less than dirt. They make me want to puke. If I’m going to kill you all anyway, the leader will go first.”

The elder’s son replied, “Even if you kill my father, you won’t get what you want. The child will die.”

Van’s mouth twisted in a mirthless grin. “If you kill her, you’ll have lost the bridle by which you hope to hold me. I can’t claim to know why, but you seem to have gone to a lot of trouble to get me. Are you sure that’s what you want? If so, then I’ve got nothing to lose, have I?” The grin vanished from his face.

“If I can never hold her in my arms again, I might as well die taking revenge. I was as good as dead before anyway. I’ll kill the lot of you and tell my friends in the next world all about it.”

The moment these words left Van’s mouth, he felt that wouldn’t be so bad. A thirst for vengeance surged in his breast. He watched the blood drain from the son’s face.

“Wait!” someone cried.

Van turned his head to the right. The youth who so closely resembled the elder pinned beneath Van’s knee stood from his stool and spread his hands wide.

“Ohson, sit down!” the other man shouted angrily, but the youth ignored him and stared straight at Van, his face pale but determined.

“I’m likely to lose my head for this.” The young man’s voice trembled as he pressed on. “But even though it may cost me my life, I will speak. It’s the cause that matters. I’d gladly relinquish my life for the cause. I apologize for our rudeness. Please, hold your anger and listen to what we have to say.”

Van stared at him. “I’m not angry because you were rude,” he said quietly. Ohson looked taken aback. His wide-eyed face still had a bit of boyishness. “You want something from me, right?” Van continued, his gaze never wavering. “Isn’t that why you kidnapped the child?”

The young man blinked. “Yes, it is.”

In a flat voice, Van continued, “If you want to throw away your own life for some cause, then go ahead. But my life is my own. That child’s life is her own. You have no right to decide whether we live or die. You know what I’m mad at? You and this stupid old man slobbering beneath me. You seem to think it’s fine to extinguish the life of a child who’s done nothing to you. I’m furious because you can’t see what you’re doing is wrong, even when it’s obvious.”

The only sound in the hush that fell over the tent was the elder’s strained breath. Van shifted his gaze and fastened his eyes on a warrior standing in a corner of the tent. “If you wanted something from me, you should’ve come and asked,” he said. “You ought to have introduced yourself and told me what you wanted. Are you incapable of something so simple and ordinary?”

The warrior’s eyes widened. He gazed back at Van for some time before speaking. “Why’re you saying that to me?”

Ignoring his question, Van raised the elder’s head and slammed it into the rug. There was a dull thud, and the old man groaned. Van let him go. Dusting his hands, he rose to his feet and stretched. Turning once again to the warrior in the corner, he said calmly, “I asked first.”

A smile spread slowly across the man’s face. The passive demeanor of an ordinary soldier vanished, replaced by that of a proud and powerful man.

“I see. So the leader of the Lone Antlers is no pushover.” He cast a sardonic glance at the others. “I guess it can’t be helped. They couldn’t stop looking my way whenever you did something unexpected. Best to drop the tedious act, then.”

He jerked his head from one side to the other, cracking his neck loudly, then stepped forward to stand before Van. Stocky and powerfully built, he looked to be about twenty-seven. His large, piercing eyes carried a hard glint.

“I am Ohfan, chief of the Ahfal Oma.”

Van returned his stare silently, but Ohfan appeared unperturbed. “You have a right to be angry. Taking the child was underhanded. We had a good reason, but if we’d judged you properly, we wouldn’t have bothered with such an elaborate scheme.”

Van’s eyes narrowed. “Judged me?” Anger oozed from his voice, and Ohfan raised his hand.

“Sorry. A bad choice of words. We sought only to ascertain your measure. After all, you’d been living with a bunch of Zolian immigrants.” He opened his mouth as if to say more but appeared to reconsider and gestured instead for Van to sit down. “It’s a long story,” he said. “Have a seat. I’ll join you.”

Ohson leaped forward to offer Van his stool while his father gave his to Ohfan. Ohfan sat with a flourish and then said to the elder’s son, “Take care of Oofah.”

The man nodded but kept his eyes lowered, a show of his shame over failure. He whispered something to Ohson, and the two of them carried the elder to the back of the tent and lowered him to the ground, where he lay clutching his forehead. Some others took the man with the dislocated shoulder outside.

Once things settled down, Ohfan turned to someone behind him and made a gesture of drinking. The man moved swiftly to bring a clay jug and two cups. Ohfan passed one cup to Van and poured a liquid into both.

“To a fresh start,” he said. “Drink up.” He drained his in one gulp.

Van brought his cup to his lips. The cloudy white liquid pricked his tongue as it slid toward his throat. It had to be fermented mare’s milk. Ohfan immediately filled his cup again, then called to one of his men near the entrance. “Bring us some food.” The man bowed and slipped outside.

Turning back to Van, Ohfan said, as if to himself, “Now, where should I begin?” He paused and gazed at Van for a long time without saying anything. Finally, the corners of his mouth lifted. “Broken Antler Van. I’ve always wondered what kind of a man you are. The phantom Pyuika Rider who used to charge out of nowhere and scatter the Zolian bastards… So, this is what someone who has seen hell looks like.” His smile broadened. “You managed to drag me out to negotiate with you even though your child’s been taken hostage and you’re on your own.” The grin vanished. “But I still hold the trump card.”

A cold flame burned in his eyes. Unlike the elder’s eyes, his were ice to their very core. “You claimed that if you couldn’t see the girl again, you’d drag us into death with you. I don’t think you were lying, either. There’s a nihilistic emptiness in your face… One step backward, and you’d plunge to the bottom of darkness. And I bet you wouldn’t utter a word as you fell. In fact, you’d probably look relieved.”

Ohfan’s lips curled. “Even so,” he whispered. “That girl’s precious to you. Perhaps you could endure if she passed quickly. But how would you fare watching her die in agony as her ears were sliced off, then her nose, or if her guts were pulled from her stomach?”

Van stared at Ohfan—at those cold, mocking eyes. “What kind of a man would even think of doing something so cruel?” he breathed hoarsely.

Ohfan blinked. His eyes narrowed slightly, and for a moment, he didn’t speak. Finally, he heaved a deep sigh and said, “I’ve got a job to do, regardless of the cruelty necessary.”

Van peered into Ohfan’s glinting eyes.

Ohfan threw his cup aside and stood. “Come. There’s something I want to show you.”

4 Fire Horses on the Snowy Plain

White light flickered through the needlelike tree leaves. Ohfan picked a path that had already been cleared of snow. People stopped their work to watch him and his men pass. The look in their eyes wasn’t curiosity at the sight of a stranger. It was closer to a desperate prayer.

Van felt their unspoken plea twine itself around him. The innocence of the children was the only relief from its oppressive weight. They glanced up at their parents questioningly, then poked and shoved each other. When one of them fell, they giggled under their breath. Chickens scurried about, oblivious to everything, scratching and pecking industriously at the dirt beneath a thin mantle of snow. The delicious aroma of food bubbling over the fire mingled with the acrid smell of smoke and the pungent odors of livestock and damp earth—the scent of a village in winter.

Van recalled the village where his aunt had lived after she got married. His mother had often taken him to visit her. Snow lingered in that small settlement deep in the mountains, even in spring. It smelled much like this.

Dogs bared their fangs and barked incessantly, disturbed by Van’s unfamiliar scent, but they did not leap at him.

They’ve been trained well, he thought. They were all handsome creatures. Their fur and muzzles, the way their ears pricked up, and the angle of their tails were enough to capture any hunter at a glance.

Ohfan reached the edge of the village and continued into the forest. Van walked behind at a leisurely pace. As the gap between him and Ohfan widened, he felt the irritation of the men bunched up behind him, but he did not quicken his pace. He wanted to learn the terrain.

Van sensed the presence of others within the dimly lit wood of evergreens and deciduous trees, but only occasionally. Dog barks echoed in the distance. Men were out hunting, Van assumed. The forest seemed somehow familiar. Van felt as if he might come upon his own village if he kept walking.

The narrow path through the trees was more like a game trail, but judging by the well-trampled snow, it saw frequent use. It sloped up a gentle rise, then ended abruptly. Van and Ohfan stepped out under a blue sky.

The scene stole Van’s breath. A broad expanse of white snow stretched into the distance. A hot lump rose in his throat at the sight of the bordering mountains. They were the peaks of his homeland, the ones he often saw in his dreams.

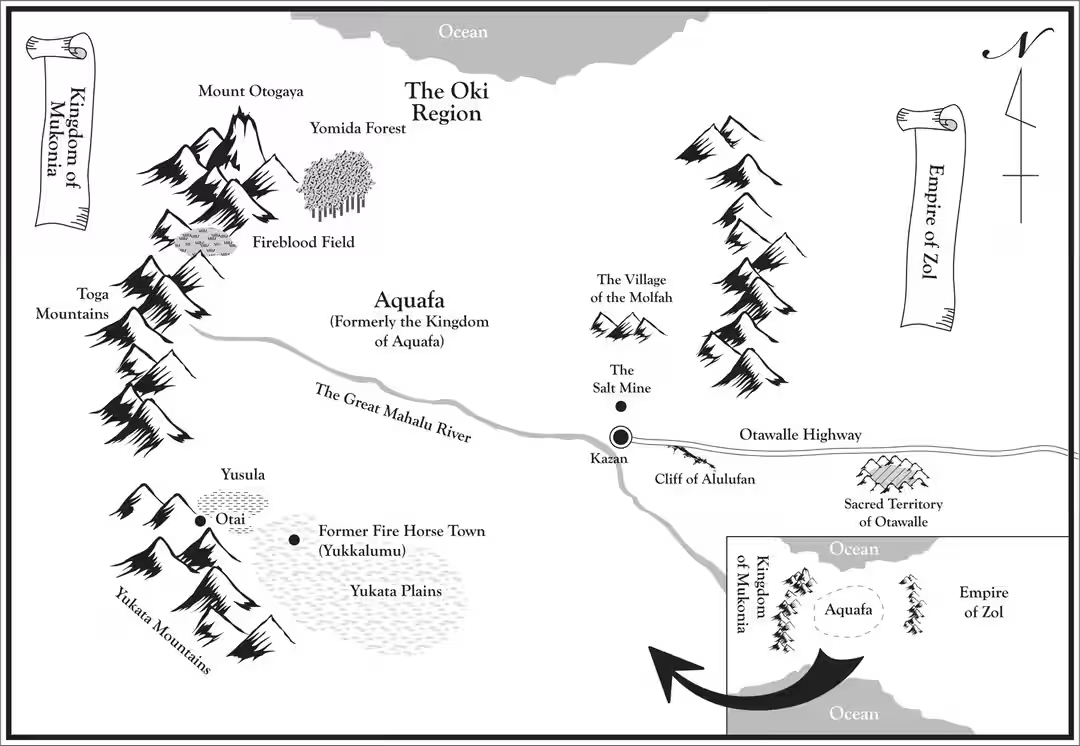

There’s Ukahla Peak! Then this must be Fireblood Field!

To find himself here of all places! Below him stretched the plateau that lay along the eastern side of the Toga Mountains, just a day’s journey from his home.

No wonder everything seems so familiar!

The hot lump in his throat heated his eyes and nose. Home—and all the word meant—stood ahead. The mountains and rivers where he had grown up, his family and friends, his wife and the life they’d shared with their son.

He could almost smell their simple home. The familiar image of its single room formed before his eyes, complete with his wife and son, firelight from the hearth playing softly over their faces as they cuddled beside it. Loss rippled through Van, crushing his chest, leaving him unable to breathe for a moment.

Even if he traveled to the other side of that mountain, his house was gone. He knew this, yet he could do nothing to quell the longing that wrenched his heart.

Van took a deep breath.

Fireblood Field, which in summer was a sea of swaying grasses, was presently cloaked in white and dotted with red-skinned creatures. They appeared to be scratching at the snow and grazing on the plants beneath.

Ohfan disappeared between two rocks. Evidently, there was a path down to the bottom of the cliff. Van glanced at the men behind him, and they gestured with their eyes for him to follow Ohfan. The brightness in their expressions surprised him. Gone were the frowns of grim irritation they’d worn moments earlier. Like boys about to set off on an expedition, their faces shone with unconcealed joy.

Van proceeded along the path down, his feet crunching occasionally on the snow that clung to the rocks. When he reached the bottom, Ohfan glanced at him over his shoulder. His face also glowed with unabashed delight. Raising his brows, he laughed out loud, then returned his eyes to the plain, cupped his mouth with his hands, and shouted, “Ho!”

Again and again, he called, his voice booming in the air. As it traveled across the plain, the scattered herd began to move; sparks streaking across a white field.

One of them pulled ahead and galloped full speed toward them, undulating with supple grace and brimming with energy.

The sight gave Van goose bumps. As his eyes adjusted to the dazzling glare of sunlight on snow, he saw that the creature drawing steadily closer had to be a horse, yet he doubted his own eyes.

It was a head smaller than ordinary steeds, yet its limbs were flawlessly muscled, and power radiated from its body. With each movement, a lustrous sheen rippled like flame across its flanks. Van stared speechlessly at the beautiful red creature that raced across the snow.

It galloped right up to Ohfan and nudged his chest with its muzzle like a happy child. “Hey there,” Ohfan said with a laugh. Slipping a hand into the horse’s mane, he stroked its neck, then looked back at Van. “Isn’t he a beauty?” Van nodded.

“And he’s not just handsome,” Ohfan added, laughing again. “He’s fast, too. Aren’t you, Ahfa? That’s right, I’m talking to you. You’re the best.”

The horse’s nostrils flared, and he stretched his neck proudly, seemingly aware of the praise. The other warriors were calling their own horses, and the commotion made conversation impossible. Rather than scold his men, Ohfan just listened, smiling magnanimously.

Each horse raced to its master. The expressions on the warriors’ faces as they greeted their steeds reminded Van of his dead comrades, and pain stabbed his heart. They’d looked just like this when greeting their mounts.

Van recalled what it was like to call his pyuika. The joy that had swelled in his breast when it raised its head, separated itself from the herd, and came prancing over in delight. The pleasant scent of its sunbathed hide. Its limpid black eyes gazing back at him.

These warriors’ laughs overlapped with the ancient echoes of his comrades. Although all of these men’s steeds looked proud and powerful, none could match the brilliance of Ohfan’s cherished Ahfa. When he’d claimed that his was the best, he had not been boasting but merely telling the truth.

The men talked fondly to their horses, stroking their muzzles and checking their legs. In fact, they seemed so wholly absorbed that they’d forgotten Van entirely. He could have taken a few steps backward and disappeared along the cliff path without them noticing. He smiled wryly at the thought.

Catching Van’s eyes on him, Ohfan offered a sheepish grin. “The haunches of a pyuika are narrower than a horse’s, aren’t they?” he asked, as if to cover up his embarrassment. His tone lacked his former arrogance.

“Yes.”

“I always wondered how far they could possibly run carrying a man like you.”

Van smiled. “They’re sturdy things. They can carry me up and down a steep cliff without any problem at all. They run all day and night without tiring. To me, your horses look more fragile.”

Ohfan cocked an eyebrow. “Really? They’re that strong?”

“Yes. And not just strong. They’re swift. I admit they likely couldn’t compete with a fire horse on an open plain, but pyuika are unmatched in the mountains.”

“Fire horses can ride down cliffs, too,” Ohfan said with a grin. “Although not the Cliff of Alulufan. How about pyuika?”

Van knit his brow. The Cliff of Alulufan? The one in east Aquafa? True, it was a precipitous bluff, but it seemed odd that Ohfan would bring up such a distant place.

“Yes, they could.”

“Really? Have you done it?”

“In the past. When we were looking for good places to ambush the Zolian army, I traveled all over. The pyuika climbed down it, but I think it’s beyond a horse. Even a fire horse.”

Ohfan’s expression clouded. Van wondered if he’d angered him by suggesting that fire horses were inferior to pyuika, but it seemed that wasn’t the case.

“Pyuika in the mountains, fire horses on the plains,” Ohfan muttered. He gazed at Van, then gestured to the approaching herd. “You may not know much about horses, but what do you think? Do you notice anything when you look at them?”

Most of them appeared to be mares. There were a few geldings and some colts. At first glance, this seemed quite normal, but when Van looked closer, he saw that the colts’ hides lacked luster, and some of them stumbled in the snow. “Were those colts born last spring?” he asked. Van had heard that horses foaled in early spring. If so, then those colts were unsteady on their feet even after a year.

Rage clouded Ohfan’s face. “Yes, they’re almost yearlings. At this age, they should be kicking the earth with their hooves and running about…if we were in the plains of our homeland, that is.” His voice trembled with more than anger. A profound grief suffused his features.

5 The Voice of the God

“It’s too cold here,” Ohfan said, his eyes still on the herd. Despair colored his words.

Van furrowed his brow. “But I thought horses were hardy enough to withstand cold weather.”

Ohfan shook his head. “Other, maybe. Not fire horses. They were made to shine in the sunlight of the plains, not live in a land buried in snow. Many foals died, unable to stand in the deep drifts when they dropped from their mothers’ wombs. They froze to death.” His lips quivered, and anger smoldered in his eyes.

“Fire horses won’t foal under a roof,” he continued with a bitter smile. “We tried making a stable like they do in the north, but when it came time to birth, the pregnant mares went crazy. One of them threw herself so hard against the walls that she broke a bone. We couldn’t stand to see that happen.

“Fire horses belong on the plains where the sun burns bright. The Yukata Plains are like a mother’s generous bosom, embracing and nourishing the herd. The horses have grown weaker every year since we were forced to leave and come to these snow-laden fields. Who knows how many foals will be born next year…or how many of those will survive.”

He pressed his lips together and paused to steady his breathing. Then he looked at Van. “What about you? What if this happened to your pyuika? Could you bear to watch them suffer and die?”

Van recalled how pitiful the pyuika had looked when tied to a post, and his face clouded. The joy of watching pyuika alive in their prime and the pain of seeing them sick. For men born to the Gansa clan, these were feelings deeply rooted in their being, transcending reason.

The same was true for these men here. The agony of watching the fire horses decline, day in and day out, ate at their souls. And there was no remedy or end in sight. With the Yukata Plains under Zolian rule, there would never come a day when they could return. Their suffering would only end when the fire horses had died off. Then, finally, despair could turn to resignation.

Ohfan’s face twisted. In a low, rough voice, he said, “When we were chased from our homeland, I cried out. I climbed to the top of a rocky mountain, faced the Yukata Plains, and shouted myself hoarse. ‘O Kinma!’ I cried. ‘What did we do that you should forsake us? Are you angry with us for our weakness? For allowing these greedy invaders to defeat us?’

“I felt so ashamed. So ashamed that my bones threatened to crumble. Yet, at the same time, it seemed so unjust. And it is, isn’t it? Which is worse: To live peacefully in one’s own land as we did or to terrorize and oppress, taking homes from others and calling them your own as they do? Even a baby could tell you the answer.”

Ohfan’s words traveled over the snowy field and faded away.

“We’re a small clan. But we lived a proud and honest life. We never sought to take what belonged to others.”

He looked at Van with tears in his eyes. “Have you ever wondered why fate is so unfair? That’s what I really asked on that mountaintop. Is this the way the world is supposed to be? Is it truly so unjust? Are the weak just there to be eaten by the strong and become their flesh? Is that the truth? Was our little clan born into this world just to become fodder for the powerful? Why are some people fated to suffer?”

Van listened silently, but within, he heard another voice—thin and faint.

“…Why me?”

His son had whispered the words on his deathbed as he lay in agony, incapable of sleep. That voice never left Van’s mind.

What determined who would live a healthy life and who would die?

“I prayed,” Ohfan continued. “I prayed for two days and nights on that rocky mountain. I told the god that we weren’t asking him for the impossible. All we wanted was justice. ‘Please,’ I begged him, ‘bring joy to those good people and punish those that cause suffering.’”

Ohfan’s face relaxed. “And what do you think happened?” Without waiting for an answer, he went on. “The god never said a word. I was devastated. I came down from that mountain feeling like I was in a gray cloud and returned to the village where we were staying for the time being. And upon my return, I learned of another calamity. A dog had bitten my father.”

The wind rustled. The noises of horses stirring and the crunching of snow under their hooves sounded sharp in the air.

“‘So that’s his answer,’ I thought. ‘The god is telling us we must bear death patiently.’ Because the dog that bit my father was a Kinma, you see.”

“A Kinma?”

Ohfan nodded. “Yes. The dogs given to us by the god Kinma. We bury horses that die of sickness in mounds. Dogs that eat their flesh and survive the illness are endowed with the power of the god. We call them Kinma dogs.

“When the Zolian bastards turned the land of the fire horses into a home for defiled sheep, their livestock began to die one after the other.” He paused and looked at his men with a crooked grin. “I must be pretty dense, huh? I should have realized that was the work of the god. Climbing the mountain and praying for an immediate solution—I was just like a child ranting at his father, unaware that his father saw so much further ahead, don’t you think?” The others smiled and nodded.

Ohfan turned back to Van. “Sorry, you wouldn’t have a clue what I mean. You see, the Zolian settlers brought their lifestyle to the Yukata Plains and tried to live just like they did at home. They didn’t just bring their sheep; they also planted their cursed grains. But those crops don’t belong on the Yukata Plains. As soon as their grain mixed with that of Yukata, it turned toxic. When the sheep ate it, they dropped dead.”

“That was the first sign, wasn’t it?” young Ohson interjected. “The god had already begun his work.”

Ohfan nodded, showing no annoyance at being interrupted. “That’s right.”

“So,” Van said, and all eyes turned to him. “Did your dogs eat the poisoned sheep, too?”

Something shone in Ohfan’s eyes. “It wasn’t just the sheep that died from eating that grain. Our fire horses died, too. We buried them as usual in the mound, but those settlers buried their sheep right next to them. They polluted the burial mound so that the sacred light no longer burned there. Our dogs dug up and ate the meat as they always did.” He grimaced. “But they died. They ate the defiled flesh and perished in agony. It was horrible. And yet…”

Once again, his eyes shone. “The god Kinma exercised his power. The sacred light of the mound was rekindled in the very place where we buried those animals that survived eating the toxic grain but died later after being infested with ticks. They must have been very strong because the bitches that ate their meat survived! They bore many clever pups that grew quickly and bred rapidly. They were smart, too, surpassing the other Kinma dogs.”

Van felt a sudden uneasiness, as if the mist covering the trail he was following had suddenly cleared before him to reveal a path he didn’t want to see. The eyes of a beast took shape in his mind—the one that had raced through the dark bowels of the salt mines and regarded him with the steady gaze of a warrior.

“So they ate the flesh of horses and sheep that survived the toxic grain,” Van muttered. “Did those dogs start nurturing the poison in their own bodies then?” he asked.

Ohfan looked at him with feverish eyes. “Yes. They have become the hands of the god. He granted those that survived the toxic grain the power to slay the men who brought it. ‘If the invaders pollute you with their poison, survive! Thus shall you become even stronger than before!’ That’s what the god was telling us. And he gave the fangs of our dogs the venom necessary to kill those who stole the Yukata Plains.”

A smile touched Ohfan’s lips and spread slowly across his face. “My father did not die, even though the settlers succumbed at the lightest graze of the dogs’ fangs. Do you understand what that means? The Kinma dogs don’t kill the righteous. Their fangs only take the lives of sinners. Those who are barred from living in this land will die when bitten.”

Ohfan’s smile faded. After taking a deep breath, he continued. “I suppose the dogs must have seemed like messengers of death in the mine. I hear the conditions were terrible.”

Van stared at Ohfan silently. The man returned his gaze. “But think about the slaves that were in there,” he said. “Were any of them Aquafaese? Were there any from the three clans of the Yukata region or from the Toga Mountains?”

Van knit his brow as he pondered this unexpected question. The features of the men he’d worked and lived with at the bottom of that dark pit were always obscured in shadow. However, none of them spoke a language he understood.

“None, right? Those who worked in the salt mines were all war slaves from the east. You were the only exception.”

A white light gleamed in Ohfan’s eyes. “You survived. You were bitten, yet you didn’t die. When we heard that, we were shaken to the core. And we gave thanks to the god Kinma. We prayed and sang for a night and a day.” Ohfan drew a deep breath. “You proved to us that those dogs truly are servants of the god. They’ve been sent not just to save us, the Ahfal Oma, but all people of Aquafa who struggle under the yoke of the Zolian barbarians.”

As the meaning of Ohfan’s words penetrated Van’s mind and took shape, a shiver ran down his spine.

Ohfan’s eyes burned. “The god gave the land to the people and creatures that lived there. We are born, mate, and bear young on that earth, and to it we return. We are the land on which we have lived for centuries. Our parents, our grandparents, and our great-grandparents, they are all part of that land.”

He spread his hands wide. “We will return to our homeland, to the beautiful Yukata Plains where the fire horses run.”

6 Dream Visitors

People shrink when they die.

Van stared blankly at his wife’s body. She seemed so much smaller than when she was alive. Now and then, he felt his son’s shoulder nudge his elbow as he sat there.

He was afraid to look at him. The boy’s innocent, tearstained face gazed up at him, his lips mouthing the same question, over and over. “Why?”

“Why, Mommy… Why…”

Why did she have to get sick? And why did she have to die, when her sister, who had come down with the same illness, recovered?

Van’s son must have known there’d be no answer if he asked, so he just kept repeating, “Why?”

Van screwed his eyes shut and clapped his hands over his ears.

I don’t want to hear. He knew what the boy would ask next. “Why me?”

Van ripped himself out of his dream. Gasping, he wiped a hand over his sweat-drenched brow. His heart hammered in his chest, thrashing in agony.

He took a deep breath and exhaled slowly, feeling the dregs of the nightmare dissipate. He’d fallen asleep at an odd hour of the day. The late afternoon light peeked through the smoke hole in the tent’s ceiling. Van absently watched the lazy smoke ascend, licking the sunbeams.

A bed, hearth, water jug, and chamber pot furnished the small one-person tent. The entrance flap was closed, and a guard stood outside, but this was a far cry from a prison cell. Van could escape anytime he liked. They had left him free because they knew full well that he wouldn’t leave.

Van rolled onto his back and mulled over the dream.

It’s been a while.

That nightmare had plagued his sleep constantly in the days following his son’s death. Ohfan’s words this morning must have brought it on.

His voice is really mine. It was Van, not his son, who always asked why.

Why did his wife and son get sick when so many others didn’t? Perhaps he could have accepted it if they’d done something wrong. Yet there was no good reason, and so he kept asking.

Why? Why did some people live long, full lives when others couldn’t?

If we can’t live very long, then why are we born at all?

Fate is so unfair…

Van covered his face with his hands. In his mind’s eye, he saw the large, dimly lit kitchen at the mine. The silent corpses of the women. The tear-drenched cheeks of the child saved by her dead mother. The girl’s button eyes staring back at him.

She survived. And so did I.

Van recalled the warmth and weight of Yuna’s body in his arms. When he’d picked her up, he’d taken responsibility for a child’s life again.

And that child still lived. He could still save her with his own hands.

With a deep sigh, Van dropped his hands from his face and stared up at the smoke hole.

Delusion…

He thought of Ohfan, a man so young and yet clan chief already. Van understood how he and his people felt. Their desire to inflict the same suffering they experienced on those who wronged them, their longing to return to their homeland—Van knew those wishes, too, so keenly that they hurt.

Yet even so, the Ahfal Oma were deluded. They had convinced themselves that the rochai with their venomous fangs were the hands of the god, servants of Kinma, sent to free these western lands from the Zolians. None of them realized how wrong, how unnatural it was to send infected beasts after women, children, and infants and then claim that their deaths were the will of a god.

Zolians are people, too.

Just ordinary people living ordinary lives.

Van thought of Tohma’s mother, Kiya, and her gentle smile. They’d had no news of Van since the Echo Master summoned him. They were surely worried sick, and it grieved him to cause them pain.

Van missed his life with them in Oki. Were it possible, he’d like to take Yuna back to live with them again. It didn’t matter where he came from there. United by chance, the days they spent together were all that mattered.

Immigrants had their own struggles. The pain of abandoning their homeland to settle here. The sweat and tears shed while setting down roots in a new land. They had experienced their own joys here, too. But it never occurred to Ohfan and his men to consider that. They’d decided their god had condemned the settlers, never pausing to wonder what lay in those people’s hearts.

Gods are such a convenient excuse.

It was true that the slaves who died to the dogs in the salt mines were from the east. However, they had fought the Zolians, just like those in the west. Those men who’d slept beside Van had been driven from their native lands and endured terrible suffering.

What’s the difference between them and us? Weren’t they hurled into the same agony? None of them deserved to die like that.

Unfortunately, Van knew he would never shake Ohfan’s conviction. All those deaths could be justified by claiming that Kinma had freed them from the suffering of slavery. The Ahfal Oma would never see that a god who let them believe what they liked was too convenient an excuse to be true. In fact, they’d be shocked to learn that’s how Van saw it. They’d wonder how someone like Van could think differently from them after he fought so desperately to defend his home from the Zolian invaders, lost so many comrades at the hands of Zolian soldiers, and endured the humiliation of slavery.

Zolian officers and soldiers—I hate them.

Their arrogant belief that the lands of others were theirs by right filled him with icy indignation that froze his blood. Van could never forgive them for the bitter hell he’d experienced as a slave. But when he searched deep in his heart, he found nothing like the loathing that made Ohfan and his men wish to exterminate every Zolian down to the last woman and child.

Maybe because the Zolians weren’t the ones who took what I cherished most.

The sweet aroma of fruit wine from a small jug near Van’s pillow tickled his nostrils, and he closed his eyes. If the emptiness that had nested in his heart all these years had been caused by another people or country, would that have made a difference? Could Van have kindled the flame of vengeance to blind himself to the darkness inside him, like Ohfan and his men?

Van let out a small sigh. No. That would’ve been impossible. Even if the Zolians were responsible for snuffing the lives of his wife and son, Van would still have seen the same thing beyond them—the deep emptiness that never vanished.

Such thoughts couldn’t be conveyed through words, though. And if he tried, Ohfan would never comprehend.

What do they want from me?

True, the dogs inspired fear, but they were still only dogs. Even with a hundred, they couldn’t possibly wipe out the entire Zolian army.

Zol was a huge empire. Disease-ridden beasts weren’t enough to drive it from this land. Surely the Ahfal Oma, deluded though they were, realized this. Was their faith in the god Kinma so fanatical that they were blind to that, too?

Or did they have something up their sleeve that they hadn’t revealed to Van yet?

Maybe that was it. Ohfan had yet to tell Van what he desired from him. He’d only said, “You’ll know tonight.”

It was what he’d mentioned after that stuck in Van’s throat like a foreign object he couldn’t swallow. “You’ll know tonight… You who’ve returned from the death of the Kinma dogs.”

The death of the Kinma dogs.

A nightmare had gripped Van after he was bitten by one of those beasts. That Ohfan called this “death” made Van strangely uneasy.

After I was bitten…

Van had changed. That was certain. He didn’t know what in him was altered or how, but some other creature, one different from the man he used to be, resided within him. It had shown its face now several times, taking over his mind and body.

So far, I’ve been able to bring myself back. But…

Van had a hunch that it might take control one day and he would disappear forever.

He placed his hands gently over his face.

What I really fear…

What frightened him most of all was that this possibility didn’t scare him.

He couldn’t remember when he first noticed it, but the emptiness inside vanished when he became that other creature. He was no longer alone. Although still an individual, Van felt at peace and connected, as though he’d melted into a great river.

Does Ohfan know? Does he know what’s inside me?

Probably. After all, his father had survived a bite, too. Maybe this was what happened to everyone who was bitten and lived. Van remembered Yuna. When the dogs attacked them that night, she’d burrowed under his stomach, crying. Her voice came back to him vividly.

“Ochan, Ochan…black…black…things…”

Yuna, too?

Did people who survived Kinma dog bites harbor something within them like those who shunned water and suffered delirium after being bitten by mad dogs?

The shining world. That heightened sense of vision where everything seemed bright even in the darkness. That sensation of everything transforming…

A ray of sunset pierced the smoke hole. As Van stared at it, something like ice water seeped through his body. He didn’t know what the Ahfal Oma hoped he would do to help them regain their homeland, but whatever the answer, it was far from simple vengeance. Van sensed that he was embroiled in something more complex and elusive.

He remembered the words the woman whispered in his ear.

“It’s more complicated than that.”

Van’s forehead creased. The Molfah and the King of Aquafa. What linked them to the Ahfal Oma?

The golden light that painted the edges of the smoke hole faded gradually. Just as the world started to sink into blue darkness, something changed.

7 The Dog King

The first thing Van noticed was the smell—a green, earthy aroma, like that emitted by a moss-covered log in the rain.

Someone was inside his tent. The flap remained shut, and he had heard no footsteps, yet he knew someone was there in the shadows.

Van sat up and stared into the corner where he sensed the person standing. He heard the faint sound of breathing in the darkness but saw no one. There was no discernible shape there at all.

As the blue twilight faded and the hush of darkness stole into the tent, Van’s eyes began to adjust. Countless little lights, will-o’-the-wisps shimmering like a summer haze, gathered and flickered, forming the shape of a man.

“…”

The grassy smell enveloped Van’s body, seeping through his pores. A voice sounded in his head.

“Co…me…”

The shimmering pale, luminous form beckoned Van. A hand reached toward him. Before he could move, it softly touched the point between his eyes. Instantly, his body fell away.

The air was sweet. Everything around him glowed, and his body felt so light that it almost floated.

Suddenly, Van was walking outside. Ahead of him strode the figure of a man, short and thickset, an elder, but not too old. His back was slightly stooped.

The world seemed curiously bright, like the night of a full moon. Although Van saw the man clearly, the tents they passed were blurred and phantomlike.

The man entered the forest. It was filled with pinpricks of light, flickering eerily. Many rose and fell like smoke dancing in the air.

Countless smells surged at Van. A familiar scent drew near, and, with a light pattering of paws, beasts came loping from every direction in packs of about fifteen each.

Rochai, thought Van. The voice spoke to him again.

“Do not call them by that crude name.”

The man had stopped and turned to face Van. The rochai had gathered around him in a ring and sank to the ground, as though prostrating before him.

“These are Kinma dogs. The hounds of the god, born from hunting dogs that received the blood of Kinma when bred with black wolves.”

It was an awe-inspiring sight. The man stood godlike in the center of fifty or sixty beasts, like a pinnacle towering above spreading foothills.

“Who are you?”

“The Dog King.”

He seemed to be laughing.

“When I am human, I am called Kenoi. I was once the chief of the Ahfal Oma, but the god Kinma summoned me, and I was reborn.”

He pointed.

“My body is over there. When I am in my body, I’m a sick old man. I don’t have long to live.”

Following the man’s finger, Van spied a body propped limply against a tree trunk with his head lolling forward.

“When I become the Dog King, I shed my body. Without it, I become strong.”

The Dog King raised his head. Van sensed he was looking straight at him.

“You’re strong, too. Can you feel it? The Kinma dogs fear you.”

Van did feel it. Their fear and adoration rolled over him in waves. If I commanded them, they would obey, he thought.

“Many brave men have attempted to become the Dog King by letting the Kinma dogs bite them. But even though the blood of Kinma resided in their veins and they bonded with the pack, none of them could become king. There are many males in the pack, but only one leader. I suppose some special quality is necessary to become king.”

The Dog King seemed to smile faintly.

“You’re the only exception I have found. Our sole hope.”

He approached Van slowly. Although his feet trod upon the grass, they made no sound. When he came close, he reached out and grasped Van’s hand. Instantly, multiple voices flowed through Van, circulating like warm liquid. He groaned. Words resonated in his head—the man’s and his own.

“O brother, who has received the blood of the Kinma dogs, hear me…”

A high-pitched hum like a swarm of mosquitos filled Van, and the dream began.

The inside of the tent grew bright. The soft glow of early morning rested, quivering, on his eyelashes. Van opened his eyes slowly. His lids were heavy, and his cheeks were wet. He must have wept while in the dream.

He covered his face with his frozen hands and smelled a familiar scent on his palms. Fresh tears filled his eyes and then slid down his cheeks.

What was that…? It had been such a long dream, filled with sorrow, pain, and joy.

When he’d left his body to merge with the one who called himself the Dog King, he glimpsed the old man’s memories of his life on the plains with the People of the Fire Horse and how all that was broken and obliterated by the invaders.

Grief and rage had flayed his soul and torn him in two as he watched the Zolians wrest the land away and drive the Ahfal Oma from their homeland. Then suddenly, a ray of hope had pierced the depths of that despair.

In that fused dream state, everything Van saw permeated him, becoming his own memory, powerful and vivid. But the image that had seared itself indelibly on his mind was not the dream memory but the expression on Kenoi’s face when he’d returned to his body.

It had been pitiful—a far cry from the shining countenance of the Dog King. Diseased and tormented by physical and mental anguish, his face was that of a shriveled old man.

Van supposed that much was natural. The weight of remorse he bore was far too heavy. The attack on the settlers, for which the Ahfal Oma were expelled from the plains, had been instigated by Kenoi’s brother, enraged by the death of his beloved steed from toxic grain. Despite knowing what his younger brother planned to do, Kenoi hadn’t stopped him. He’d warned him, of course, explaining that only harm could come of such a scheme. Still, he hadn’t truly attempted to dissuade him. Kenoi was the chief, yet he’d failed to quell the wrath of his people. He’d even shied away from confronting it. His own weakness had invited the final, crushing blow.

With their land seized, Kenoi’s people had been forced to leave, banished forever from their homeland. They had gone weeping, looking back, again and again, for one last glimpse. And it was Kenoi who bore, body and soul, their anger, grief, and silent reproach.

Van slid his hands from his face and gazed up at the smoke hole. The morning sky framed through the opening should have been a familiar sight, yet he felt as though he were seeing it for the first time.

He grimaced and squeezed his eyes shut. Desolation overwhelmed him. The loneliness that he’d carried for so long now. The homeland he’d never know again. The time he’d never relive. His beloved Aleesa and their son Moshilu. Their smiling faces, the warmth of their bodies, their scents. His elderly parents laughing at the pure joy on their grandson’s face when he took his first steps. Holding Aleesa in his arms, feeling her smooth skin against his, inhaling her fragrance, pressing his cheek against her nape…

No matter how hard Van pleaded, those days would never return.

They were fallen leaves swept away by the rushing stream.

Flashing swords. The stench of blood and entrails. Sweat. His friends, their faces buried in their hands as their shoulders heaved with sobs.

Van heard again the whispered words of his friend Vasal the night before their last battle. “I want to go home…to where my wife and daughter used to sit by the hearth making boar and mushroom stew. Where my mother shucked beans, her legs stretched out in the sun.”

That longing to go home, to return to a family and a place long gone. Just one more time…

Van wept, letting the tears run down his face. He’d wanted to weep for so long.

He felt as if he’d been walking through this loneliness forever with no one to turn to. Even when far away, that yearning for where he’d lived with his family never left. He was just a leaf that had dropped from its branch long ago, fated to be swept along until swallowed by the sea. Even though he knew this, the aching loneliness would never end.

The Ahfal Oma are leaves torn from their homeland, too—just lonely leaves desperate to go home.

Now Van understood what they wanted. After living in Kenoi’s memories, as though one with him, this desire seemed as natural as if it were his own.

Van heard a commotion outside his tent. He had been aware of people moving about for some time now, but this was different. The voices heading this way seemed to have business with him.

He sat up just as the tent flap rose. A man ducked his head and entered. When Van saw his face, his brows arched in surprise.

The man smiled, and in that moment, his resemblance to Van’s wife was so strong that Van’s heart nearly stopped.

“Brother,” he whispered. With hands trembling, he grasped that of his brother-in-law and childhood friend. The man’s lips trembled, and tears fell from his eyes as he pulled Van into a rough embrace.

1 Those Who Pull the Strings

The glow of sunset faded, and the woodshed sank into blue darkness. Ilia bent over Makokan and peered into his face, looking slightly amused. “Well. You’ve certainly aged, haven’t you?” she said.

“Ilia.” Makokan mouthed his sister’s name, but his voice came out as a croak. She cut the ropes binding his wrists with her dagger and thrust a small flask at him.

“Here, drink this. The drug should have worn off by now, but your throat’s probably still raw. Take it easy, though, or you’ll choke.”

He took a swig. Cool liquid filled his mouth, but it was hard to swallow. Makokan took little sips yet still gagged.

Ilia clicked her tongue and thumped him on the back. “Trust you to choke even though I warned you.”

Wiping the tears from his eyes, Makokan looked up at her and rasped, “What is going on?”

She dropped to one knee beside Makokan and gave him a sour look. “Honestly. Why did you go into service with a son of the House of Yuguraul? You went to all that trouble to escape this pointless system, then roped yourself right back into it of your own accord. That’s taking stupidity to a new level.”

Makokan stared at her blankly.

“I’d really like to help, but there’s nothing I can do about it now,” she said. “You’ll just have to see how far you can get.”

Makokan frowned. “Ilia, would you talk to me in words I can understand?”

She sighed and ran a hand through her hair. “You’ve walked smack into a quagmire and waded until it was up to your neck. Is that any clearer? Still, they didn’t have to use blow darts. I told them to leave it to us, but they wouldn’t listen.”

“They?” he whispered. “You mean the Ahfal Oma?”

Ilia snorted. “There’s no need to whisper. You’re in the woodshed at our house. They’re not allowed into the yard.”

Makokan looked around. “I don’t remember a woodshed like this.”

Ilia sighed again. “How many years do you think it’s been since you left?”

Makokan glared at her. “What is this? You knew it was me, but you still tied me to a post in a shed in our yard! Knock it off, will you?”

A cold light kindled in Ilia’s eyes. “I’m not kidding around. If you weren’t my brother, I would’ve let them kill you. Keeping that guy’s bodyguard around would’ve complicated things needlessly.”

Makokan’s forehead grew cold. He looked into his sister’s eyes, but they showed no trace of feeling.

“Shows you how worthless your life is, doesn’t it? If you can make others think you might be of use, they’ll let you live. But if they think for a moment that you’ll get in the way, you’re done for.”

She brought her face close to his. “I don’t want to kill you. That’s why I came here to talk. So listen and think about what you must do to stay alive.”

This was the sister who killed Makokan’s older brother. He felt his pulse quicken, and numbness spread up his neck and across his chin.

“We were sent here by the Inner Circle, you know,” he said.

“So? Our clan has given you a nice warm reception. What could be wrong with that?” Her eyes gleamed softly in the dim light. “I’m still following Cheehana’s orders and carrying out the work she gives me. However, we have other business, too. Very important business.”

She pulled her face away and continued with a frigid tone. “Otawalle is like the moon reflected on the water. It can’t shine of its own accord. In the past, it glowed with the light of Aquafa, and now with the light of Zol. It has always let the rulers of each era shine, taking its light from them.”

Makokan stared at her silently.

Ilia served the Inner Circle of Otawalle, carrying on the work that the Shinock family had done for generations. He’d never had an opportunity to know what she thought of that.

“Did Cheehana order you to investigate the Ahfal Oma?”

“Yes,” she replied bluntly. “It’s easy for us to get information because we accepted them into our midst and let them live here when they were exiled. But we have deep ties with the Ahfal Oma, and the Inner Circle is probably uneasy relying on us alone for information. Sometimes, it sends others to check things out.”

Ilia laughed through her nose. “It doesn’t really matter. We know the hand of the Inner Circle inside out. If an outsider contacted any member of the clan, we’d learn of it right away. They could bribe one of the clan, and I’d still know.” Her expression turned serious. “But we can’t be so laid-back anymore. We’ll be in trouble if the Sacred Territory starts meddling.”

Makokan felt as though he almost understood what she was saying but not quite, like trying to guess an object’s identity by feeling through a thick blanket. Still, one thing was clear: His sister had betrayed the Inner Circle. She’d sided with those who masterminded the attack by those infected beasts. And if that was the case, then the people of Makokan’s homeland, the Yukata Mountains, were surely on the same side.

The Ahfal Oma and the Ofal Oma. The peoples of the Yukata region, bound by ties that stretched back through the ages, had joined forces in a conspiracy. Which means my own clan orchestrated mittsual’s revival. Makokan felt his innards shrivel. She’s right. I’m up to my neck in quicksand.

He looked at Ilia. “Where’s Hohsalle?”

“No need to fret. We’re taking good care of him. He’s an important hostage, after all—someone we can use.”

“Hostage?”

Ilia shrugged. “Of course. Don’t you get it yet? After all I told you? We don’t want the Sacred Territory to interfere. We can use him like a weight to counterbalance the Otawalle.”

She stood and motioned for Makokan to rise. When he did, she told him to turn around and then bound his wrists so deftly that although the rope was slack enough for him to move his wrists, he’d never work them free.

“Just pretend you’re a wooden doll,” Ilia said from behind. “Don’t react to anything you might hear. And do as we tell you. In the end, that’s what will save you and Hohsalle. Don’t bother thinking or acting for yourself. There’s far too much you don’t know.”

Makokan glanced over his shoulder. She laid a hand on his back and gave him a gentle shove. “Move. I’ll take you to Hohsalle.”

Ilia had been telling the truth—Hohsalle was indeed being given a warm reception.

Makokan had been led through dark alleyways to the hall of Ukani Okusa, a cousin of the clan chief. While the Okusa were a prominent family, their hall stood alone on the west side of the capital partway up the mountain, which was probably why it had been chosen to house the hostage.

Ilia led Makokan through the back door. The servants bowed slightly, then showed them into a corridor and withdrew.

“He’s in this room,” Ilia said. “Go on in.” She removed the rope from Makokan’s wrists, coiled it up, then turned on her heel and strode away.

Makokan sighed and knocked on the door.

“Come in,” a voice said. When Makokan opened the door, he was enveloped by a heavenly aroma that he knew well: roast duck, a delicacy in this region served from fall through winter. The bird had been hung and aged, then basted with a honeyed sauce and roasted until its skin was crisp and glossy. Its cavity was stuffed with things like walnuts and chestnuts, giving the meat a rich flavor.

Hohsalle sat alone at the table, carving the duck with a dagger and shoving chunks of meat into his mouth. When Makokan entered, he merely glanced up at him, not bothering to stop eating.

“Good to see you’re safe, sir,” Makokan said.

Hohsalle chewed a mouthful of meat and swallowed audibly, then chased it down with a swig of wine. Only then did he stop and look at Makokan. “It’s good,” he said. “Have some.”

Makokan took a chair and sat, but he found that he had no appetite. “I’m amazed you can eat at a time like this,” he whispered.

Hohsalle snorted. “I’m furious. And when I’m mad, I get hungry.” He hacked off another chunk of meat and shoved it into his mouth.

“You’re angry? Don’t you mean ‘worried’?”

“Worried? What should I be worried about?”

“What should you be worried about?! You’ve been knocked out with a blow dart, abducted, and imprisoned!”

“That’s precisely why I’m so mad! And to use blow darts! Damn it! The nerve of them. Depending on a victim’s metabolism, even a small amount of poison could have serious consequences!”

Hohsalle gulped down his wine. “Cheehana! Curse that old hag! She sent us here knowing this might happen. Cunning old witch!”

“You really think she would do that?”

“Of course she did!” Hohsalle practically spat the words. “She couldn’t trust the Servants of the Inner Circle living in the Yukata Mountains to keep an eye on the Ahfal Oma, so she sent us to see how they’d respond. And we’d be able to check on the disease while we were at it, too. That scheming old bag used me like a pawn in her game! Chucked me like a pebble into a pond to watch the ripples.”

Makokan stared open-mouthed at his furious young master. “Um, there’s something I need to tell you,” he began hesitantly. Hohsalle waved a hand at him, urging him to continue. Makokan repeated what his sister had said.

Hohsalle listened silently, although he continued eating. When Makokan finished, he heaved a sigh. “Your sister’s a servant of the Inner Circle through and through. I can see why you ran away from home.” He turned his cup in his hand and watched the wine swirl. “You think the Yukata clans are behind the mittsual affair, but I doubt it.”

Makokan’s eyes grew round. “Why?”

“If it were only the Yukata clans, the Sacred Territory would have spurred the King of Aquafa into action long ago and put out the fire while it was still little. There’s no way the Sacred Territory would’ve stood by and let the Yukata clans attack the Zolian governor’s son during the falcon hunt.”

Makokan frowned. “You mean…”

“That’s right, damn it. What a pain…”

His words coincided with a knock on the door. It opened, and Makokan’s eyes widened in disbelief. The figure that strode into the room was none other than Milalle, who should have been at the clinic in Kazan. She was draped in a thick fur cloak, and her cheeks shone red from the cold.